1

Academic Year

2017/2018

PhD CourseInternational PhD in Management

The role of the companies on promoting

economic development in emerging

countries: An analysis of the Brazilian case

Author

Hérica Morais Righi

Supervisor

i

This work is dedicated to a professor that taught me the beauty of being part of a student’s

ii

Acknowledgement

It's the end of a difficult journey, a journey that did not start three years ago, but eight years ago. And now in the end, I just have to thank you. Thank you for the learning I had during this time, for the friends I met along the way, for the friends who accompanied me during this walk and for the opportunity to start a new cycle.

First of all, I thank God for always blessing me and for showing me the best way. Thank you for always gracing me with the beautiful side of life and giving me strength in difficult moments.

I thank Sant'Anna and all her staff for the opportunity to complete my PhD in this important and welcoming institution. I thank the administrative team, they did everything to make my stay in Italy as quiet as possible, especially to Elisabetta Picci and Elisa Zanobini who were always very friendly in everything I needed.

Thank you to the Management Institute of Sant'Anna. I thank all the professors, researchers and administrative support for sharing their experiences and knowledge with me. And to the Management del'Innovazione (MAIN) research group for welcoming me and allow me to learn a little more with you and share my experience

Some people were crucial to my development as an economist, researcher, professional and person: Carlos Arruda, Eduardo Albuquerque, Márcia Rapini and Sara Souza. No matter where I go or what I work with, you were the basis of my professional training and I was fortunate that they stayed in my life as great friends, for whom I have a very special affection.

To friends who have always accompanied me in my journeys, friends of a life, that even the distance was able to erase, I will not name everyone because the list is long (Varginha, Belo Horizonte, Campinas, São Paulo e Curitiba). You give me the assurance that I am a very lucky woman, for always finding incredible human beings who support me in difficult moments and celebrate my conquests.

To the friends I met during this journey in Italy. I arrived with a suitcase in my hand alone and I finish these three years surrounded by friends that I know will be for

iii

life. I met people and stories that taught me a lot and were my support for the homesickness that gripped me throughout this period. In particular I thank Chiara, Cristina, Irene, Maral, Nora, Lorena and Shahab for all the support during this time. A special thank to Chiara for revising all my papers, Irene that helped me to develop the econometrics’ part and Cristina that read all of them and debated about my results.

Special thanks to Rosana, a friend who in a moment of anguish opened her door and showed me a world full of possibilities. I will not be able to thank you enough.

To my grandmother, my uncles, cousins, nephews and my father’s wife, a special thanks for always standing next to me celebrating each step. I've always known that I'm part of an incredible family. Thank you!

To my sister, that even from distance and differences of thoughts, we know that our union is much stronger than this and that her eyes shine with pride at every conquest of mine.

To my parents .... I do not even know how to thank you for so much love and so much affection. I never doubted that this separation was painful. “saudade” is stronger every day, the hardest part of this new cycle is not being with you. More than thanking you, I apologize for depriving us of our conviviality and knowing that a choice of mine have caused so much suffering. But I also know that the happiness of seeing myself realizing dreams is greater than this pain and I wake up every day in order to make this happiness increase every day. Thank you father and thank you mother for understanding my path and my choices and support them.

A special thank you to a person I met in the middle of this journey, Alessandro. A companion for all moments, sad and happy. Thank you for taking such care of me, for taking the stress during this time and for being by my side in such difficult times. You are my support!

And, finally, my thanks go to a Professor I met about 12 years ago who patiently and very lovingly taught me the teaching job. Thank you, Professor Suzigan, for everything you've always done for me. And I'm sorry if I ever let you down.

iv

“In order to live free and happily, you must sacrifice boredom. It is not

always an easy sacrifice”. Richard Bach

v

Summary

Introduction ... 1

Chapter 1 – Which are the weaknesses to improve innovation process

in emerging countries? An analysis of the Brazilian case ... 25

INTRODUCTION ... 25

1.1 THE DEVELOPMENT OF INNOVATION IN EMERGING COUNTRIES ... 26

1.2 THE CHALLENGES OF INNOVATION PROCESS ... 29

1.2.1 Internal Barriers to Innovate ... 31

1.3 THE BRAZILIAN INNOVATION SYSTEM ... 33

1.4 METHODOLOGY ... 39

1.4.1 Data Source ... 39

1.4.2 Statistical Methodology ... 40

1.5 BARRIERS TO INNOVATION IN BRAZIL ... 43

1.6 FINAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 50

REFERENCES ... 53

APPENDIX ... 58

Chapter 2 – Together we are supposed to go far: The effect of

collaboration in the Brazilian Innovative Process ... 62

Introduction ... 62

2.1 The advancement of the cooperative strategy as a source of innovation ... 63

2.1.1 Innovation as a systemic and interactive process ... 64

2.1.2 Creating partnership to survive market competition ... 65

2.2 The development of industry and innovation in the Brazilian Context ... 67

2.2.1 Partnerships as a strategy to follow the leaders... 69

2.3 Methodology ... 72

2.4 Results and Discussion ... 75

2.5 Conclusion and Implications ... 80

References ... 84

Appendix ... 89

Chapter 3 – Disentangling University-Industry Collaboration in Brazil

... 92

vi

Introduction ... 92

3.1. Interaction with universities as an instrument to improve firm’s innovation process ... 93

3.2. Complementary role of universities in emerging countries ... 96

3.2.1 The role of universities on Brazilian innovation system ... 98

3.3 Research Hypotheses and Methodology ... 101

3.3.1 Methodology and PINTEC’s database ... 104

3.4 University-Industry interaction and impact on innovation in Brazilian firms .... 106

3.4.1 Impacts on innovation process ... 110

3.5 Conclusion ... 114

References ... 117

Conclusion ... 123

1

Introduction

The increasing advance of knowledge and the increase of its complexity means that in nowadays innovation plays a leading role in the development of companies and economies, as it creates new markets and optimizes its costs and processes. This prominence had already been highlighted by Karl Marx in his book "The Capital", emphasizing the importance of technological changes in the process of company accumulation (Freeman, 2008).

In this sense, innovation is a central tool in the industry’s search for better competitive conditions, by reducing costs, creating new products, the emergence of a new production process, or other factors. Therefore, in a context where the dynamism of the market demands a constant renewal of companies, knowledge plays an incisive role in economic development. The investment in production and absorption of knowledge becomes a determinant for the growth of the industry.

However, innovation does not emerge from the effort of a single agent. The innovative activity is the result of a process involving several actors, national or sectoral. The "National System of Innovation" (NSI) approach presents the importance of interaction between institutions that are part of the innovation process. This approach emphasizes that the interaction between different actors of the economy influences the creation and diffusion of new technologies, which in turn boosts the technological progress of a country. In this scope, the fragility of the connections between institutions and companies in developing and emerging countries undermines the consolidation of the NSI and, consequently, jeopardizes its economic and social development.

In this context, this study aims to identify the main issues that inhibit the consolidation of the innovation process on emerging countries. To do so, it is going to analyze Brazilian companies. The present thesis is dived into three papers. Each paper considers one important issue to the innovation process development. The first one is about the main obstacles to the innovation process inside companies and their impact on innovation activities. The second paper discusses the establishment of partnerships in order to boost the innovative process. The third paper argues about a specifically partner, which are the universities and their role on the Brazilian innovation process. These issues will be explored using data from the last three editions of the Innovation Research (PINTEC) conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the database includes data from 2006 to 2014.

2

As a way to clarify Brazilian science and technology development process and the structure of each paper, this introduction is divided into 2 topics. Considering that the formation of institutions is a relevant and determining factor for the consolidation of the innovation system, the general history of the scientific and industrial scenario is going to be briefly presented on the first topic. The second one presents the main points of each paper that will be presented on the next chapters.

1 The consolidation of Science and Industry in Brazil

Nelson (2006) argues that the difference between countries can also be explained by macroeconomic conditions (such as industrial incentive policies). Therefore, in order to understand the reasons that lead to the difference in the growth rate between countries, it is necessary to understand the context in which the institutions of a country are developed, their particularities and the national structure (organization of institutions, available infrastructure, that the government, companies and universities exert in the innovative process, etc.). In this sense, this topic aims to briefly describe the history of scientific activity in Brazil and to show the late concern to create an institution that had in the production of new knowledge the basis of its teaching and developing new knowledge.

Universities in Brazil always had as main research focus the understanding of knowledge already produced in large centres, although some research topics seek to advance in the frontier of knowledge. It is also noted that part of the research carried out in Brazil did not have as priority the search for solutions of problems presented by the industry yet. Brazilian industry, for its part, for most of its history was in a comfortable situation where competition with the most advanced industry in other countries was not a priority on its agenda. It was installed in a protected market and its technological backwardness did not even allow itself to think about expanding its market to other countries. Thus, it is shown that universities and industry appeared in Brazil in parallel and without convergent objectives and interests. This issue helps to understand and justify the difficulty in establishing a dialogue between these institutions, but mainly shows the importance of changing this issue.

3

- The formation of the industry in Brazil

The Brazilian productive system began with extractive and agricultural activities, in these last ones, especially the production of sugar cane and coffee. Crops were primitive, labor intensive, and used simple machines. At the beginning of the 19th century, small industrial companies emerged that did not last for long. The economy was based on the export of primary goods such as sugar and coffee, and the little existing industry served as a support and complement to agricultural activity. (Foot and Leonardi, 1982).

The accumulation of capital in Brazil, however, accelerated in the 1880s when slave labor was gradually replaced by wage labor. During this period the modernization of coffee plantations occurred with the introduction of machines to benefit coffee and the construction of a rail transport system (Suzigan, 2000). It was these changes (improvement of coffee quality and reduction of transport costs) that provided the conditions for the accumulation of capital invested in the industrial sector, since until the mid-nineteenth century investment in the processing industry was very limited (Suzigan, 2000).

The growth of coffee and cotton exports in the late nineteenth century drove Brazilian industrial investment. During this period, new factories appeared in the country, starting a first attempt to start an industrialization process. It is important to highlight that this process was complex, and it is possible to find in the specialized literature different approaches on this topic. Suzigan (2000) cautions that the lack of systematic data on industrial investments in the nineteenth century makes it difficult to assess the beginning of the industrialization process in Brazil.

The author shows that the sectors that developed at the end of the 19th century in Brazil were concentrated in industries that had existed in other countries since the 18th century and therefore used more known and simpler technologies. These companies were concentrated in the majority, but not only, in sectors of consumer goods (textiles, clothing, food) and metal - tools, agricultural implements, nails and screws; lead pipes; parts and accessories for railway wagons and trams. However, the development of more technologically sophisticated industries, such as capital goods, for example, was not observed. Suzigan (2000, p.38) explains that "the demand for capital goods was directed to the countries of the centre, and the domestic capital goods industry did not develop, thus impeding the autonomy of the accumulation of industrial capital".

Until 1913, in Brazil, the nascent industry was concentrated in the activities of support to the agriculture (in particular to the production of coffee). The sectors that developed in Brazil (textiles,

4

clothing, food, metal mechanics, for example) used simple technology and did not demand the production of knowledge for their development or to create competitiveness of the products. The companies installed in Brazil were limited to import the technology of the countries that were already in a more advanced stage of development. Curado and Cruz (2008) emphasize that the incoming capital in the country during this period also focused on supporting the coffee export activity, therefore, the sectors that were ahead of the technological knowledge of this period (basic chemical industry, mechanical industry and electrical material) did not integrate the Brazilian industrial base until the beginning of World War I.

Suzigan and Szmrecsányi (1996) argue that in the years before World War I and during the 1920s it is possible to observe greater and more frequent inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the manufacturing industry, which according to the authors, in the country's industrial development. However, Versiani and Suzigan (1990) point out that in the 1920s the non-durable consumer goods (Textiles, Food, Clothing, Footwear and Beverages) account for about 70% of the value added in the manufacturing industry. The authors (1990, p.9) show that these industries, except textiles, were "mainly made up of small-scale establishments using semi-artisanal production methods". Thus, although in that period the number of manufacturing industries increased, this expansion did not translate into more modern companies, on the contrary, they were companies that used simpler and more delayed production techniques, they were not at the frontier of knowledge.

Despite the continued dependence of the Brazilian economy on the export sector and the importation of machinery and industrial inputs, since the 1920s increased investment in the industries of production of basic inputs such as cement, iron, steel, etc. "However, investments in the manufacturing industry were no longer simply complementary or subsidiary to the export economy of agricultural products, but were increasingly related to the growth of domestic demand for industrial raw materials (cement, iron and steel, chemicals, paper and pulp, etc.) and machinery in general (for agriculture, industry, construction, etc.) "(Suzigan 2000, p. 121).

The crisis that began in 1929 led to a suppression of the export sector, putting the coffee economy in trouble. From this scenario, for the first time, the Brazilian economy turns to its domestic market and promotes investment in productive activities that responds to domestic demand, especially activities related to the industrial sector (Furtado, 1964 and Suzigan, 2000). But although the depression of 1929 stimulates the development of industry in Brazil, this growth was not accompanied by a specific policy of encouraging industrial production.

5

This period, therefore, is characterized by a greater participation of industrial activity in the result of the economy. Furtado (1964) points out that the crisis of 1929 stimulated the development of the industry based on the internal market, but he is aware that this growth did not mean an increase in productive capacity, but rather in production. The increase in the prices of capital goods (a sector not yet in the Brazilian industrial park) inhibited the expansion of productive capacity. And many of the companies founded in that period were built using equipment from factories that closed in the developed countries because they cost cheaper than new and state-of-the-art equipment.

Villela and Suzigan (2001) also claim that the industrial growth and diversification observed since the 1930s is a result of the investments made in the 1920s in basic industries (such as cement and metallurgy) and protection of national industry from exchange rate policy, in the 1920s. Thus, stimulated in the 1930s, Brazilian industrialization was stimulated by import substitution.

Malan et al. (1977) analyse the effects of the import substitution policy of the 1930s and report that the success of the development model via import substitution is linked to three main factors: the rise in the relative price of imported products relative to domestic products; exchange rate depreciation; and high customs tariffs as a means of protecting industries installed in Brazil and quantitative barriers to entry of imported products.

It is important to highlight at this point that since the 1920s began a discussion in the scientific environment about the need to establish a university that had the mission of linking teaching and research activity to support the formation of nascent industry (through human resources to find solutions for industry or as scientists to develop knowledge that would help the domestic industry to integrate with the leading technology companies in developed countries. This debate became more pronounced in the 1930s and culminated in the creation of USP in 1934. However, the industrial composition shows that the Brazilian industrial park was still concentrated in sectors of widespread technology, sectors of non-durable consumer goods (such as textiles and foodstuffs, for example) and that, in this way, did not demand knowledge or need for investment in the search for new technologies. The use of the idle capacity of the national industry from the difficulty of investing in the expansion of productive capacity allowed the accumulation of capital that boosted the growth of the national industry from the 1940s (Furtado, 1964; Malan et al., 1977). Malan et al. (1977) also attributes industrial growth in the 1940s to population growth and the formation of the domestic market for manufactured goods.

6

The basic industries were those that also developed during the Second World War (1939-1945). In this period, Villela and Suzigan (2001, p.236) highlight the government's initiative in founding the Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional (CSN) in Volta Redonda (in the state of Rio de Janeiro) as "one of the most important decisions for the country's industrialization", although it only began to produce after the war.

Following the 1930s’ process, during the World War II (1939-1945) industrial growth was based on the utilization of the maximum capacity and was marked by the limited import of machinery and equipment, which impaired quality and compromised the technological development of industries. From the initial impetus of the early 1930s, it was realized that in order to maintain the growth of the industry, protectionist policies would be needed that would not allow the recovery of the world economy to alter the demand for domestic products in favour of imported products. Furtado (1964, p.235) states that "the possibility of large losses, caused by the abrupt cheapening of imported competitive goods, would discourage investments in the domestic market sector".

According to Versiani and Suzigan (1990), in the 1940s and 1950s there is an accelerated growth of the Metallurgical, Mechanical, Material Transportation and Electrical Material industries. This growth reveals an increase in the production of Durable Consumer Goods and Intermediate Goods, more technology-intensive products, and the relative decrease in the share of Non-Durable Consumer Goods in Brazilian industrial production (which are, in general, simpler sectors in technology and knowledge). The loss of importance of non-durable consumer goods and increased participation of durable consumer goods, intermediate goods and capital industries follows a post-war trend in the world economy, as Furtado (1990) suggests.

In the second half of the 1950s, during the Kubitschek’s government, the Development Council was set up in 1956, which was responsible for outlining the development strategy for the country (Orenstein and Sochaczewski, 1990). At the end of 1956, this council implemented the “Plan of Goals” – Plano de Metas – (1956-1961), which is considered the first effective plan of economic development in the country that focused on elaborating the goals of the private sector. Despite the lack of a globalized and integrated view of the economy, Tavares (1972) points out that this was the first national-level planning that was successful.

According to Orenstein and Sochaczewski (1990, p 177), the “Plan of Goals” "contemplated investments of five main areas: energy, transportation, food, basic industries and education", which would be basic areas for the growth of the national industrial sector. Versiani and Suzigan (1990) affirm that from the “Plan of Goals”, the country started to have a policy focused specifically on

7

industrial development, but it was not yet focused on technological development, as Suzigan (1996) points out, the focus was only the growth of the industrial base and not its development. This plan addressed issues such as: articulation between the state and private capital; investment in infrastructure; development of specific industries; protectionism in the internal market; industrial investment financing; among others.

However, it is important to note that the predominant sectors of national private enterprises were not knowledge intensive. Furtado (1975) shows that with the consolidation of the industrial structure in the 1960s, it was possible to observe three specific actors in the Brazilian industrial structure: national private sector (some large companies and "a considerable number of small entrepreneurs"); powerful foreign private sector; and public enterprises. For the author (1975), these actors have complementary and non-competitive roles. While state-owned enterprises operated mainly in areas of infrastructure or creation of external economies; the national private group operated in sectors such as construction, traditional manufactures and subcontractors of the other two groups; and, finally, foreign groups have control of the durable consumer goods, chemical-pharmaceutical and equipment industries in general, that is, more knowledge-intensive sectors.

Since the 1950s, however, there have been effective attempts to implement policies to encourage industrial development. Influenced by the development of post-war developed countries, the Brazilian government began to create institutions and scientific infrastructure that supported the production of knowledge and innovative activity in companies in a second moment. From this period, support for scientific research became part of government plans as an instrument of economic development.

However, this guideline did not have the desired effect, since the national scientific production was not aimed at boosting the productive sector, but at the replication of external knowledge and studies related to population or agricultural problems. Another issue that impeded the success of the attempt to form a Brazilian innovation system is the contradiction between science and technology development policies and macroeconomic policies. Although the first one aimed at stimulating science in Brazil aimed at supporting industry, including through the production of new technologies, the second facilitated the importation of technologies, discouraging entrepreneurs from investing in internal technology development (Velho, 1996).

In 1963 the country entered a recession, culminating in the military coup of 1964. Suzigan (1996) points out that the economic and political crisis faced by the country between 1963 and 1967 has resulted in the abandonment of support for industrial growth. With the crisis and lack of incentives

8

to industry, investment in development in new technologies also declined. However, as a reflection of the post-war debate, the creation of universities, science support institutions and research incentives was observed in this period in an attempt to organize the National System of Scientific and Technological Development (SNDCT).

With the intention of encouraging the Brazilian private sector to develop technologies was instituted by the National Bank for Economic Development (BNDE) in 1964 a program called FUNTEC. The initial objective of the program was to foster the process of companies’ own technology production and to support the learning process from imported technologies. In this way, companies could create competence for later internal production. But these objectives were not achieved since the industry did not have internal competence to use the resource. So, the FUNTEC started to be destined to the consolidation of research groups.

The industry entered again on the political agenda from 1968 onwards in the Costa e Silva government. For Versiani and Suzigan (1990), the growth observed since 1968 is a result of the development of the domestic market and support for the export of manufactured goods by the government, coupled with the favourable conditions of the global economy and the ease of attracting foreign resources. This phase was marked by government incentives to industrialization as tax incentives and subsidies for financing with the BNDE, including for the importation of the technology.

In 1975, the II National Development Plan (II PND) was implemented. From this plan a new cycle of investments started in the industries of basic input, capital goods and infrastructure. Suzigan and Furtado (2006) report that the industrial policy of this period was focused on building sectors that matched the industrial pattern observed in developed countries. For Suzigan (1996), this development plan articulated a set of investments in economic, social infrastructure and science and technology. One of the characteristics of this plan was the currency devaluation that further intensified the protection of the country's installed industry (Suzigan, 1996).

Despite the low technological production of the period, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the country already had a diversified industrial structure (Versiani, Suzigan, 1990). However, with the world crisis of 1979 and its reflection in 1980-1981, economic policy turns to the adjustment of the domestic economy (macroeconomic policy) to the detriment of industrial incentives policies. This period was marked by macroeconomic stabilization policies that often did not encourage, instead punished companies and thereby reduced (or even cut) spending on technology and development of already low innovations.

9

From the 1980s, driven by the crisis, the structural problems inherited from the previous bold and costly plans implemented by previous governments stand out. The increase in public debt, foreign debt and the tax burden, together with the crisis, slowed down the growth of the economy, and consequently the technological development of industrial activity (which at that time was close to zero).

In the 1990s, there was a failed attempt to implement a policy to encourage industry, the Industrial and Foreign Trade Policy (PICE). The only implanted guidelines of this policy were the deregulation of imports and the reduction of tariffs, which together promoted the country's economic opening and with that the industry located in the country loses the protection it enjoyed within the domestic market and starts to face the competition of products foreigners of better quality, modern and cheaper.

The opening of the economy in the 1990s without prior planning and preparation did not favor the development of the industry because it was not capable of facing strong global competition. However, this process has alerted entrepreneurs to the importance of investing in new technologies and new products, but this awareness has so far reached a small share. The industry then begins to gradually restructure to face this new reality, redefining its strategies and incorporating into its goals the acquisition of new technologies and increased production efficiency. It is possible to affirm that it is only recently that part of the industrial companies (although a small portion) effectively incorporates the innovative activity in its strategy.

In Brazil, protectionism served as an enclave of national industrial production. The companies did not bother to prepare to compete in the world market and did not have a structure of training and production of knowledge compatible with its development. These factors have contributed to the emergence and development of national entrepreneurship and the lack of understanding of the importance of investment in the production of internal technologies.

- The formation of the scientific base in Brazil

The obstacles that hindered the development of science in Brazil date back to its discovery. For Suzigan and Albuquerque (2008, p.14), "the colonial system represented a long obstacle to national scientific accumulation." Until the arrival of the court, there was no higher education course in Brazil, only courses for ecclesiastical careers, which, according to Cunha (1980), were directed

10

toward the exploitation of the colony. The author emphasizes that ecclesiastical teaching had two levels: the first was limited to teaching reading, writing and calculations; and the second, similar to an upper course, was restricted to the teaching of philosophy and theology.

The few and rare existing scientific exploration activities were initiatives of foreign researchers to understand the natural resources of Brazil and the “New World”, they had as a purpose to find the commercial value of the resources found in Brazil (Schwartzman, 1979). The author assures that until the second half of the eighteenth century, science in Brazil was far short of the science developed in the rest of the new continent. The first university of Spanish America is the one of Santo Domingo, founded in 1538. Later other universities appeared in Spanish America in countries like Mexico, Peru, Chile and Argentina. Cunha (1980) points out that in 1822, the year of Brazil's independence, there was no university installed in the country, while there were already 26 in Spanish America. The first Brazilian scientific institution was the Botanical Garden founded in 1808 by the Portuguese court and the first university was founded only in 1934 (University of São Paulo, USP).

Suzigan and Albuquerque (2008) divide the constitution process of the Brazilian scientific structure into five "waves". The first is the beginning of science in Brazil with the arrival of the court and the founding of research institutes such as the Botanical Garden and the National Museum. The second wave occurred in the last three decades of the 19th century, in which the creation of other research institutes, such as the Campinas’ Agronomic Institute (IAC), Bacteriological Institute, Vaccinogen Institute, Manguinhos Institute, among others, were observed. The third wave was the beginning of the discussion about the importance of inserting in the mission of higher education the research activity and the need to create a university within the modern concept of the term and not only as the meeting of isolated colleges without a mission in common. During this process the University of São Paulo (USP) was founded in 1934 with the objective of starting a new stage of Brazilian higher education. The fourth wave occurred from the second half of the 1940s, when the end of World War II prompted a new concept of the importance of science as the basis for technological progress. The fifth wave indicates the period of the military regime in which the government showed support and support for the development of science in Brazil through increased research support, institutionalization of postgraduate studies, and the creation of research centres in state-owned enterprises.

AS it was said before, the first “wave” began with the arrival of the Portuguese court in Rio de Janeiro in 1808 in which the creation of the first institutions of higher education is observed. The

11

transfer of the court from Portugal to Brazil in 1808 also brought about the emergence of the concept of "National State" in the country and the need to build an infrastructure to support this state. The demand arises in order to form bureaucrats and specialists to give continuity to the National State. These schools were focused on military and state issues (medicine, mathematics). Scientific activity was not part of the curriculum of these schools (Cunha, 1980, Schwartzman, 1979). Schwartzman (1979, p.65) recalls that "for the imperial government that was more important than technical and industrial development was the political consolidation of the country and the creation of an administrative and military organization able to watch over the public thing".

With the arrival of the court, however, more significant efforts were noted in the direction of initiating scientific activities in the country, but these efforts were not enough. Some isolated initiatives could be perceived to initiate a scientific apparatus in Brazil, such as the foundation of the Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro in 1808 and the National Museum in 1818. From then on, they began to establish research activities (Schwartzman, 1979), although embryonic. In this first period, the support and interest in the constitution of the scientific base in Brazil were found to be inexistent, the initiatives were focused on the solution of utilitarian and immediate issues (Velho, 1996).

The second "wave" of institution building, according to Suzigan and Albuquerque (2008) runs from 1870 to 1900. Two areas whose scientific activity stood out in this period were: public health and agronomy, due to the social demand and the productive sector. In this context, the Manguinhos Institute, which had research focused on the development of sera and vaccines, did not require the application and development of complex technologies or high investments (Schwartzman, 1979).

During this period, new colleges were created, focusing only on the training of professionals and excluded the importance of the development of scientific activities in congruence with teaching. There is also the foundation of two museums, which later became research centers. It is noted that at the end of the 19th century, Brazilian higher education concentrated its efforts only on the training of labor force and, therefore, was contrary to the model of higher education observed in Germany and the United States, which incorporated scientific research in mission and aimed to support the productive base of these countries.

Schwartzman (1979) classifies the teaching of existing schools in this period as "book-learning", ie teaching based only on knowledge transmission already established (in books, for example), without research activities (theoretical or applied) or exploration that is, without the production of self-knowledge. For the author (p.113), "the little academic research that was done

12

there was the initiative of some self-taught professors, not institutionalized forms of scientific activity".

From the beginning of the Republic Declaration, the country began to observe greater density in the science produced in the country. However, a considerable part of this knowledge was focused on health issues, in order to solve problems arising from the process of urbanization that the country was experiencing (knowledge related to biology and medicine, for example); and for agricultural-related issues encouraged by the Brazilian agro-exporting economy and the need to stimulate agricultural research to solve pest problems (Schwartzman 1979, Velho 1996). Until the end of the nineteenth century, therefore, there was no consistent initiative in Brazil to support and create a systematic scientific activity with the purpose of exploring and generating new knowledge, lacking investments and critical mass for the execution of this activity.

The third "wave" of institution-building is identified by Suzigan and Albuquerque (2008) between 1920 and 1934, when a broader and more complex industrialization movement began. In this period, according to the authors (2008, page 15) "initiatives for the creation of universities arose, culminating in the founding of USP in 1934".

At the beginning of the 20th century, there was an increase in the demand for technical training and, consequently, the creation of several higher education schools, mainly engineering. This is due in part to the intensification of the country's industrialization and development (railroad construction and expansion of new agriculture) and to the external environment, as Europe underwent a phase of application of basic science developed (Schwartzman, 1979). Science, that was incipient and weak, at that time remained restricted to the immediate solution of problems that arose with the advance of the economy: diseases, plagues, infrastructure, etc.

Brazil tried to follow in the beginning of the twentieth century, but without success, the German university model in some areas, such as the effort made in chemistry. Yet this effort was still detached from an industrial base, which was embryonic until the 1930s (Schwartzman, 1979). However, it is important to emphasize that it is only from the beginning of the 20th century that the discussion about the union between teaching and research and the need to establish a university in Brazil begins to be addressed. It is from this debate that the courses of higher education appear throughout the country, but they emerge only with the teaching function and still detached from scientific activity and, therefore, far from the concept of the modern university. This movement began to gain strength in Brazil from the 1920s onwards with the Brazilian Association of Education (ABE) and the Brazilian Academy of Sciences (ABC).

13

Since 1927, ABE promoted national conferences for discussion on education issues, such as the establishment of a Ministry of Education and the founding of a university. The association stands out in this movement by cherishing the debate about the importance of a university, even promoting in 1927 a survey about the university model to be adopted in Brazil (Schwartzman, 1979). During this debate and new ideological positions provoked by the cultural movements of the 1920s, the University of São Paulo (USP), the first Brazilian university, was founded in 1934. As described by Schwartzman (1979) and Mendonça (2000), USP's goal was to combine professional training with academic training, highlighting the importance of scientific activity in conjunction with teaching activity.

The Faculty of Philosophy, Sciences and Letters was the central point of the university and had the responsibility to integrate the institutes. The purpose was to create an example of abandoning of the traditional teaching ("book teaching") and encouraging other units to adopt this new perspective. It was constituted as the center of scientific production (Schwartzman, 1979. Suzigan and Albuquerque, 2008).

The scientific production gained more support only from the end of the 1940s, a period marked by the co-evolution of technologies, economic structures and institutions. For Suzigan and Albuquerque (2008) this period is the fourth "wave" of institution-building. At that time, an embryo of the Brazilian Innovation System began to emerge from the creation of the first institutions to support and foster research activities and universities. It is worth noting the creation in 1948 of the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science (SBPC), in 1951 of the National Research Council (CNPq) and the Commission for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (Capes), coordinating institutions for research and graduate activities in the country, respectively.

The creation of these institutions was driven by the growing role that science occupies as a promoter of economic development in the post-war period. In this sense, it began in Brazil, as well as in other countries, the concern to include research activity in economic planning as a means of development. Science stopped to be an instrument of intellectual and cultural leadership to take a more active role in the growth of economies (Schwartzman, 2001).

In this context, it is important to mention that scientists started to claim for the recognition of its importance by society. With the prominence of science in promoting economic development after the Manhattan Project, scientists in Brazil began to request the insertion of their class into strategic decisions for the country and argued that they should not be limited to academic activity (Schwartzman 2001). The interaction with the productive sector is also seen as an important element

14

by scientists in the development of science, as a means to legitimize this activity in society and decrease dependence on financing and public policies - since this issue could harm the stability of research activities (Velho, 1996).

The fifth "wave" of institution presented by Suzigan and Albuquerque (2008) occurred during the military regime, that began in 1964. This period is decisive in the expansion of Brazilian universities and in the formation of institutions to support research activities. During the military regime, there was an expansion of the organizing structure of the Brazilian scientific base with the foundation of science support institutions, funding for scientific and technological development, and the emergence of new colleges and universities. Velho (1996) emphasizes that during this period these efforts were part of the attempt to set up a National System of Scientific and Technological Development (SNDCT). This set of measures is a reflection of the postwar discussion, as shown earlier, that science should play a more active role in the development of knowledge that drives the growth of the productive sector.

As a result of a long debate since the 1940s and social pressures, the university reform was implemented in 1968. Among the measures, it was established that Brazilian universities, especially public ones, should grow supported by a tripod formed by teaching, research and extension (Schwartzman, 2001).

From this new framework, the postgraduate education in Brazil was institutionalized and systematized, which guaranteed both the development of research and the qualification of teachers and the workforce training (Mendonça, 2000). This resolution boosted the research activities in universities, allowing them to produce knowledge that should help the development of technological production in companies.

In this period, Suzigan and Albuquerque (2008) report the creation of the Financier of Studies and Projects (FINEP) in 1967, which originated in the Technological Development Fund (FUNTEC) of the National Bank for Economic Development (BNDE). FUNTEC, created in 1964 by the BNDE, was a financing fund whose initial purpose was to encourage the private sector to develop its own technologies and to assist them in understanding and mastering imported technologies (Velho, 1996). However, the author points out that this goal was impaired since the national companies did not have competent human resources in the area of knowledge development and the investment in technology importation was much more advantageous than concentrating efforts and resources on internal creation. As a result, the success of the program was hampered, and the government needed a new plan to begin training competent professionals in this activity and then to encourage companies. Thus,

15

FUNTEC later began to support research and teaching in universities. From this fund it was possible to consolidate research groups in areas important to the productive sector such as the exact sciences and engineering (Schwartzman, 2001; Velho, 1996).

In 1965 the State University of Campinas (Unicamp) was founded under the command of Zeferino Vaz. This university was born based on the concept of the modern university according to Schwartzman (2001: 293), Unicamp was "the closest that Brazil ever had to a real university of research". In order to compose the faculty of the new university, Zeferino Vaz brought back Brazilian scientists who worked abroad. The university had as its center the Institute of Physics. Unicamp was born with the main mission of training professionals focused on the development of technologies and who could cooperate with national companies in this regard (Schwartzman, 2001).

The central objective of the funds created during this period was to encourage the private sector to be an important source of funding for scientific production, which did not happen. Velho (1996, 47) argues that initially companies were not interested in financing and "when the programs were relatively mature, they went on to justify their lack of funding on the grounds that academic research was of little applicability." The author explains that the university research was really focused on the so-called basic research. This is due to the dichotomy between the national development policy and the macroeconomic policy. There was a lack of incentives for companies to invest in the production of knowledge that would support their own technology development.

Thus, the Government's effort to bring universities closer to the productive sector did not have the expected result and the two environments developed in parallel without common activities. While the university focused its resources on performing exploratory and basic research activities, following existing and available funding sources; companies had no incentive to collaborate with university research because of the lack of in-house ability to use the knowledge produced and the ease and security of importing ready-made technologies.

Faced with this hiatus between the scientific production of universities and the low interest in producing new technologies, the Government decided to become a demander of research and technology, becoming more present in the productive sector (Velho, 1996). Suzigan and Albuquerque (2008) highlight the creation of research centers in state-owned companies such as Petrobras Research Center (CENPES) and Telebrás Research and Development Center in Telecommunications (CPqD). Embraer was founded in 1969 and the Brazilian Agricultural Research Company (EMBRAPA) in 1973, which is an important research and development agent for agricultural issues.

16

It is also observed in this period the implementation of national development plans such as the PBDCTs (Basic Plans of Scientific and Technological Development - Suzigan, Albuquerque, 2008) based on the guidelines of the First National Development Plan (I PND). The purpose of the I PND was to reaffirm the importance of the production of technologies for industrial development and to increase the competitiveness of domestic production in relation to international trade (Salles-Filho, 2002). The objective of this set of Plans (I, II and III PBDCTs) was to support the development of the country through the expansion of the domestic production of technology, for which it sought to align the policy of Science and Technology with macroeconomic policy for the first time (Salles- Filho, 2002).

Although these plans represented an important step towards the country's development policy, with the crisis of the 1980s its guidelines were abandoned due to lack of resources (Suzigan and Albuquerque, 2008), and the government's priority was to adjust the domestic economy, and with this the incentives to industrial development were stagnant.

In 1985 the Ministry of Science and Technology (MCT) was created, coordinating institution of S&T policy, with the end of the military regime. Suzigan and Albuquerque (2008) point to the late government's initiative to create an institution with the role of coordinating the guidelines that guided the development of science and technology in the country.

From the 1990s, the country undergoes a post-crisis restructuring process, at the same time as the opening of the economy. This new reality raises a problem that is the importance of increasing competitiveness and modernizing the national companies. Velho (1996) points out that in the government policy of the then President Collor, it was necessary to invest in modernization and competitiveness for the development of the economy, emphasizing the importance of the company's relationship with the university in order to collaborate in the development of technologies. The author (p.55) states that the Collor government's Industrial and Foreign Trade Policy (PICE) prioritized "the encouragement of technology parks, private business research centers and a significant increase in R & D budget resources".

From the 1990s, with economic opening, the national industry gradually attentive to the importance of investing in technology if it wanted to remain in the market, since the national products started to compete with those that were most often imported quality, more modern and competitively priced. The government in a convergent way establishes some actions that prioritize the investment in knowledge and technology, such as research notices and incentives for interaction, since the university has come to be considered an important actor in this process. Among these instruments can

17

be highlighted the Information Technology Law, reformulated in the early 1990s, which encouraged R&D activity in companies and interaction with the academic environment. In 2003 and 2008, industrial policies were launched whose focus was to structure a favorable environment for the production of technologies and innovation. Supported by these policies, the public announcements to promote R&D in Brazil are currently aimed at intensifying this relationship.

2 Scope of the thesis

Emerging countries are pursuing the maturation of their economic development, and innovation is a key point at this process. In this sense, understand the main issues that inhibit this consolidation process is important in order to define which factors needs attention to promote the economic development.

On the central of this system there are the companies. They are the centre of the innovative process and the other institutions are configured as a support of this process. Within this network of support to technological activity stand out institutions such as: other companies (i.e. suppliers, competitors), the university, the government, the financial system, research institutes and consumers. In this sense, the focus of this study is to analyse the main issues of the innovative process inside companies. To do that we divided into three points: Internal barriers, collaboration with other institutions and collaboration with universities.

The complexity of the innovation process demands a favorable environment (internal and external) to boost the generation of new technologies and knowledge. On the same time that companies need to be embedded on a solid innovation system in order to induce the knowledge generation, funding and incentives, they need to develop internally specific resources and competences to work with the creativity process and follow guidelines and processes.

It becomes relevant to understand the constriction points for the consolidation of innovation inside companies. However, according to Fagerberg and Verspagen (2009), innovation studies are mostly concentrated on the explanation of the phenomenon on developed countries while a smaller part is dedicated to emerging countries. There is a long debate about the constrictions faced on developing countries regarding their Innovation Systems’ problems like policies, lack of relationships between actors, science development and investments. But the internal issues and their impact on the innovation production are still uncovered. In this context, the first research question was:

18

1) Which are the points that encumber the innovation consolidation inside companies located in Brazil?

As argued above, to strengthen the innovation process inside companies, it is important to count with an encouraging external environment that count with the support of partners, specially on the knowledge and technology production.

The advancement of knowledge and technology frontier raises the demand from companies of the combination of assets and resources to improve their innovation process. The companies need to work on an open architecture in order to boost their innovation process combining their competencies and use complementary resources (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990; Mowery et al., 1996; Tidd et al., 2001; Chesbrough, 2003). In this scenario, the fragility of the connections between institutions and companies of developing countries, as observed in Brazil, undermines the consolidation of the NSI and, consequently, jeopardizes its economic and social development. Then, it becomes important to understand the impact of these partners to the innovation process in order to clarify in which degree these partnerships are contributing to the technological development of these companies. In this sense, the second research question was:

2) In which leverage the collaboration with other actors (universities, suppliers, competitors, government, and others) entice the innovation process on the Brazilian market?

Among the possible links inside a NSI, the connection between universities and companies emerges as an important interaction for technological progress. In fact, it is increasingly dependent on the advancement of scientific knowledge and universities produce this scientific knowledge that supports the innovation activity carried out by firms (Klevorick et al., 1995, Cohen et al., 2002).

From the company's point of view, interaction with universities has several benefits, such as access to technology and knowledge, reputation and image enhancement, risk reduction, cost reduction, skills development, corporate values and culture enrichment, technology testing and development, new perspectives, recruitment and retention, access to qualified professionals and students (Bonaccorsi and Piccaluga, 1994; Kanter, 1999; Santoro and Chakrabarti, 2001; Nielsen and Sort, 2012: Kanama and Nishikawa, 2015; Scandura, 2016).

In emerging economies, universities perform functions beyond the training of human resources and knowledge production. They also work as radars capturing knowledge produced in developed countries, and as technology producers and diffusers. The low degree of research and

19

innovation activities usually observed in firms operating in emerging countries reinforces the importance of universities in these countries to produce and diffuse technology (Rees and Debbage, 1992; Arza, 2010; Suzigan et al., 2011). In this context, the third paper discusses the impact of cooperative projects with universities to the development of new products. So, the third research question was:

3) What is the impact of universities on the innovation activities in Brazil? -

- Structure of the thesis

This thesis is structured in three chapters, each one is a singular paper. Then a conclusion that sum up the findings is presented in the end.

Chapter 1 – Which are the weaknesses to improve innovation process im emerging countrie? An analysis of the Brazilian case

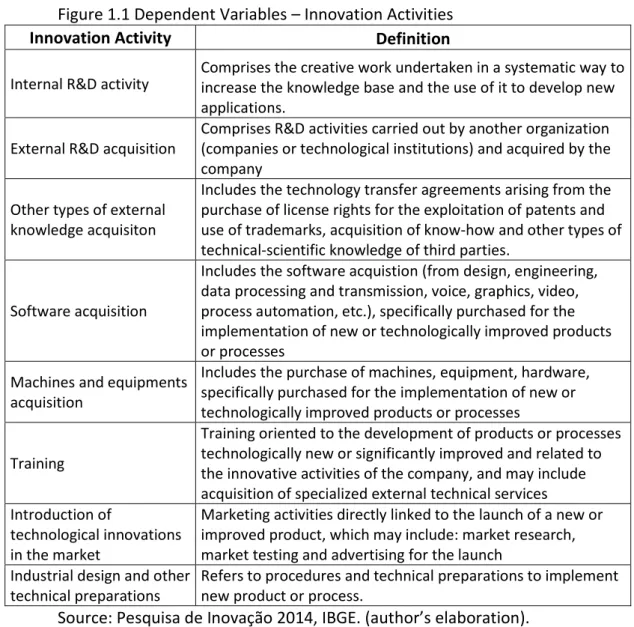

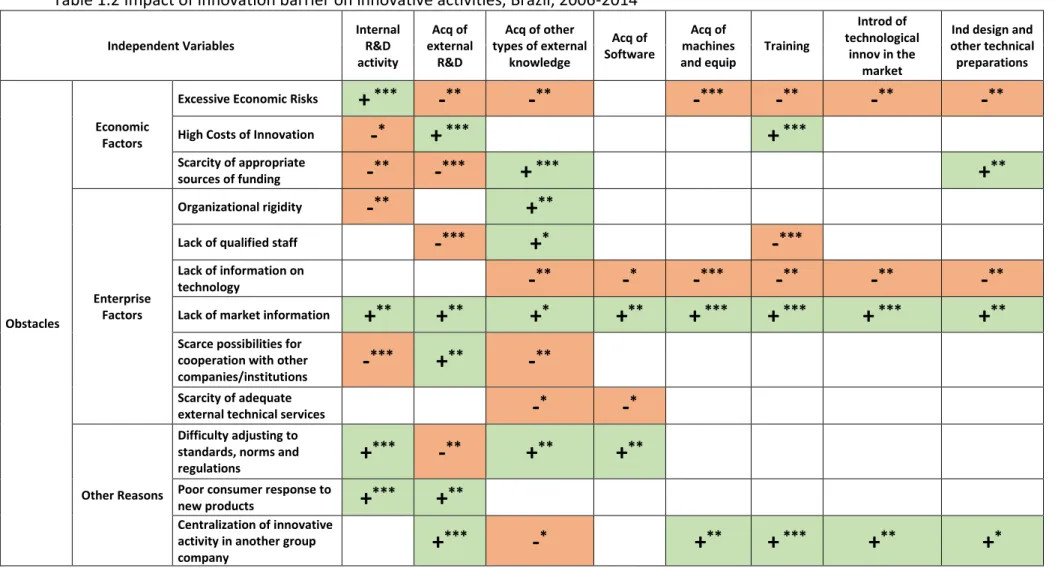

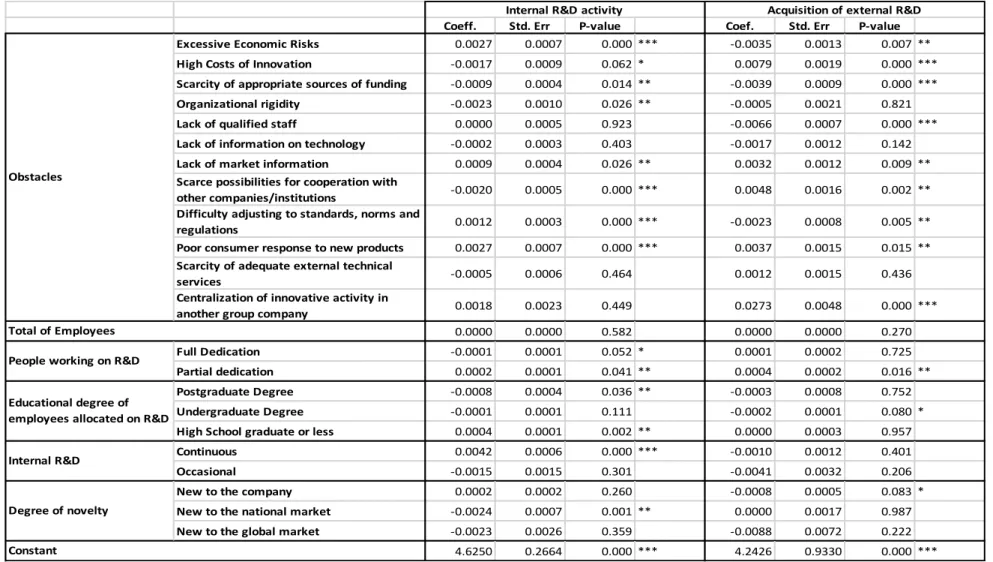

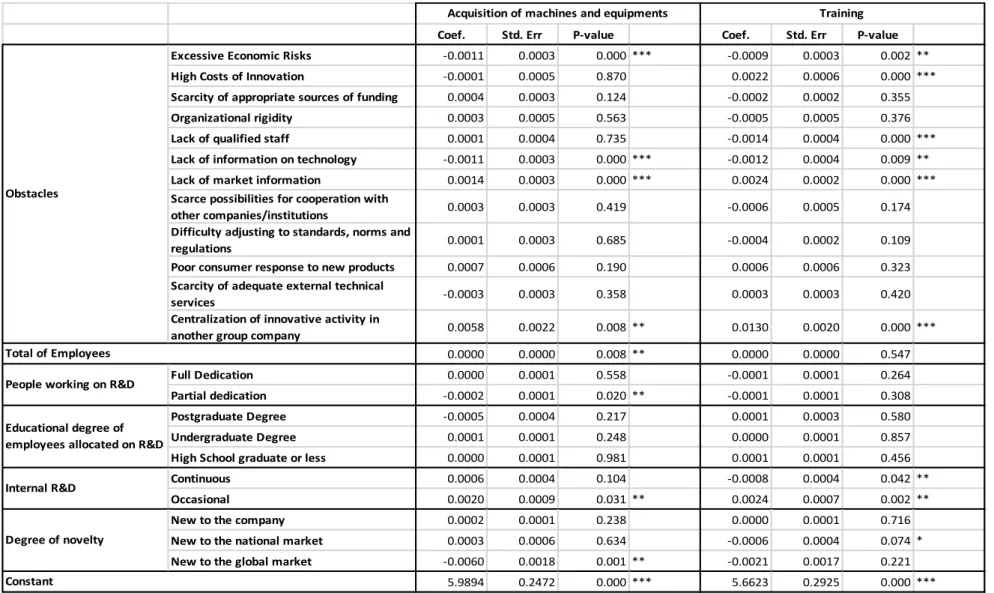

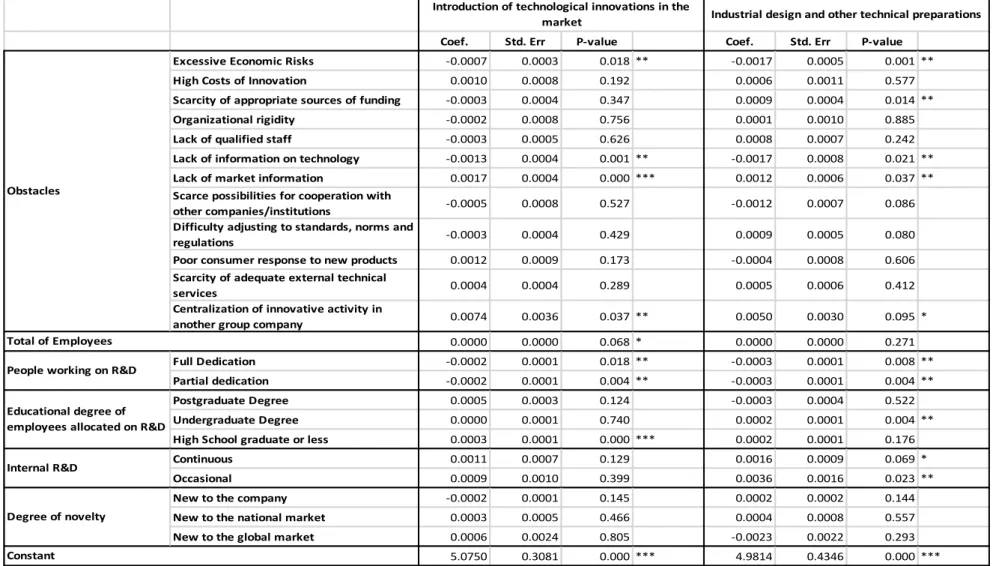

This paper, co-authored with Irene Martelli and Andrea Piccaluga, analyses the barriers of innovation to Brazilian companies. Using the database provided by the Brazilian Innovation Survey (PINTEC), it pursues the impact of the declared barriers to the innovative activity. Considering the two categories of barriers proposed by D’Este et al. (2012), deterring and revealed barriers, the paper looked to determine if the innovation is influenced by those barriers or not. The revealed barriers are those obstacles that arise from the effort to implement innovation, that is, the difficulties that come with the innovation activities. The concept of deterring barriers refers to those that impede the innovative effort inside the companies. Two hypotheses were proposed. The first one considered that, since Brazil presents a low R&D investment, the companies tend to face barriers as deterrent to their innovation process. The second hypotheses proposed that the lack of qualified personnel and technological information does not impact the performance of innovation in Brazilian companies.

Chapter 2 – Together we are supposed to go far: The effect of collaboration in the Brazilian Process

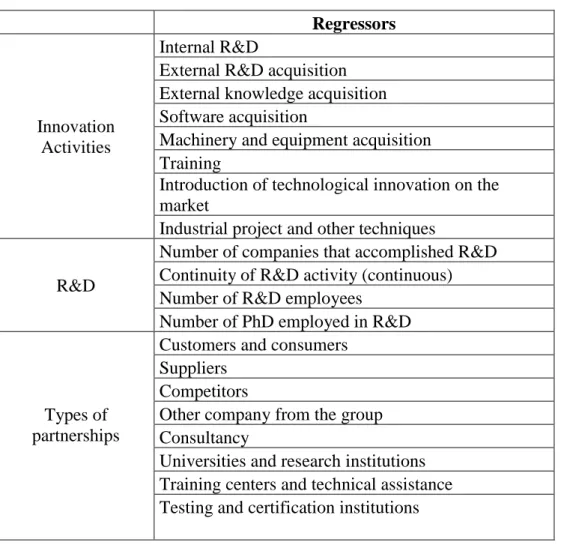

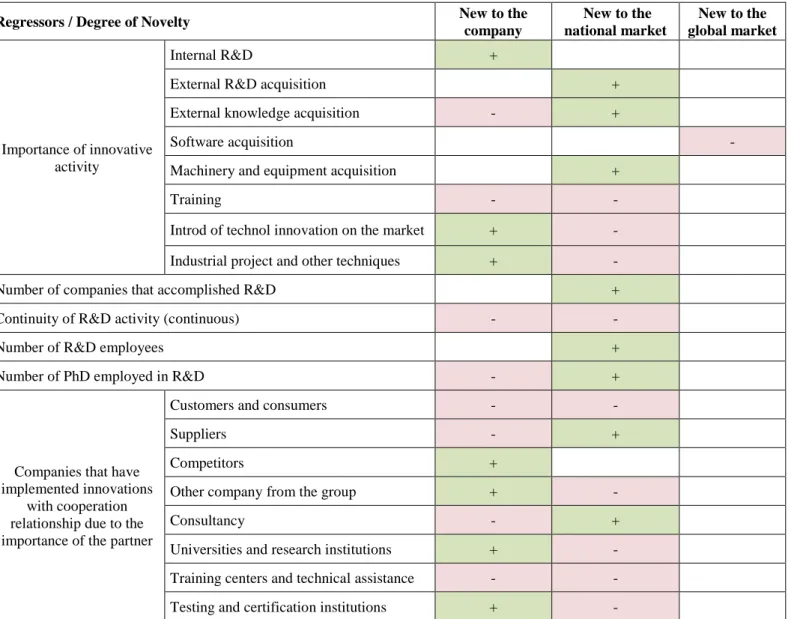

The second paper, co-authored with Irene Martelli and Andrea Piccaluga, discusses the importance of the partnerships to the innovation process in Brazil. There are two types of partnerships to innovation. The first one, called ‘Science, Technology and Innovation’ mode (STI-mode), is characterized by the production and use of codified scientific and technological knowledge. The other, called ‘Doing, Using and Interacting’ mode (DUI-mode), is based on the learning through the

20

process (Jensen et al., 2007). In this sense, using PINTEC’s database it was developed three Poisson regressions to determine the impact of these partners to the degree of novelty of the new products launched. From the literature analyses two hypotheses emerged. The first one argued that the STI-mode cooperation (universities, research institutions and consultancy) does not present a positive impact on the development of new products to the market. The second hypothesis, on the other hand, stated that the DUI-mode cooperation has a positive impact on the innovation activity.

Chapter 3 – Disentangling University-Industry collaboration in Brazil

This one, co-authored with Irene Martelli and Andrea Piccaluga, treats about the relationship between universities and industries in Brazil. University is a critical component of the innovation system, and the way it evolves and collaborates in companies’ innovation process is determinant to encourage or inhibit the maturation of the innovation system. Using data from PINTEC, the paper presents a Poisson regression to clarify the impact of the universities on innovation activities and degree of novelty. From the literature presented raised two hypotheses to be tested. The first considered the dependence of external technologies and stablished that the relationship between companies and universities is more intense in the medium and low technology sectors than in the high technology sectors. The second one focused on the role of universities in Brazil and stated that companies that invest on internal R&D tend to have less interactions with universities.

21

References

Arza, V. (2010). Channels, benefits and risks of public—private interactions for knowledge transfer: conceptual framework inspired by Latin America. Science and Public Policy, 37(7), 473-484.

Bonaccorsi, A.; Colombo, M.G.; Guerini, M.; Rossi-Lamastra, C. (2014) The impact of local and external university knowledge on the creation of knowledge-intensive firms: Evidence from the Italian case. Small Business Economics, v. 43, n. 2, p. 261-287.

Chesbrough, Henry. (2003) The logic of open innovation: managing intellectual property. California Management Review, v. 45, n. 3, p. 33-58.

Cohen, W.M.; Nelson, R.; Walsh, J.P. (2002) The influence of Public Research on Industrial R&D. Management Science, v. 48, n.1, p.1-23, January.

Cunha, L.A. (1983) A universidade crítica: o ensino superior na República populista. Rio de Janeiro, Livraria Francisco Alves Editora S.A.

Curado, M.; Cruz, J.V. (2008) Investimento Direto Externo e Industrialização no Brasil. Revista Economia Contemporânea, Rio de Janeiro, v.12, n.3, p. 399-431.

D’Este, P., Iammarino, S., Savona, M., & von Tunzelmann, N. (2012). What hampers innovation? Revealed barriers versus deterring barriers. Research policy, 41(2), 482-488.

Fagerberg, J., & Verspagen, B. (2009). Innovation studies—The emerging structure of a new scientific field. Research policy, 38(2), 218-233.

Foot, F., Leonardi, V. (1992). História da Indústria e do Trabalho no Brasil. São Paulo: Gobal. Freeman, C., & Soete, L. (2008). A economia da inovação industrial. Editora da UNICAMP. Furtado, C. (1964) Formação Econômica do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Editora Fundo de Cultura S.A.

Furtado,C. (1975) Análise do ‘Modelo Brasileiro”. Rio de Janeiro, Editora Civilização Brasileira.

22

Jensen, M. B., Johnson, B., Lorenz, E., & Lundvall, B. Å. (2007). Forms of knowledge and modes of innovation. The learning economy and the economics of hope, 155.

Kanama, D.; Nishikawa, K. (2017) What Type of obstacles in innovation activities make firms access university knowledge? An empirical study of the use of university knowledge on innovation outcomes. The Journal of Technology Transfer, v.4, n.1, p.141-157.

Klevorick, A.K.; Levin, R.; Nelson, R.; Winter, S. (1995) On the sources and significance of inter-industry differences in technological opportunities. Research Policy, v.24, n.2, p.185-205, March.

Malan, P.S.; Bonelli, R.; Abreu, M.P.; Pereira, J.E.C. (1977) Política Econômica Externa e Industrialização no Brasil (1939/52). Brasília, IPEA.

Mendonça, A.W.P.C. (2000) A universidade no Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Educação, n.14, maio-agosto, pp. 131-150.

Mowery, D. C., Oxley, J. E., & Silverman, B. S. (1996). Strategic alliances and interfirm knowledge transfer. Strategic management journal, 17(S2), 77-91.

Nelson, R. (2006) Sistemas Nacionais de Inovação: Retrospecto de um Estudo. In Nelson, R. As Fontes do Crescimento Econômico. Campinas, Editora Unicamp, pp. 427-468.

Nielsen, C; Sort, J.C. (2012) Hos is value created and exchanged in different stages and different types of university-industry collaborations.

Orenstein, L.; Sochaczewski, A.C. (1990) Democracia com Desenvolvimento: 1956-1961. In: Abreu, M.P. A Ordem do Progresso: cem anos de política econômica republicana, 1889-1989. Rio de Janeiro, Editora Campus, cap. 7, pp. 171-195.

Prahalad, C., & Hamel, G. (1990). The core competency of the corporation.

Rees, J.; Debbage, K.G. (1992) Industry knowledge sources and the role of universities. Policy Studies Review, v.11, n. 1, pp. 6-25.

Santoro, M. D., & Chakrabarti, A. K. (2001). Corporate strategic objectives for establishing relationships with university research centers. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 48(2), 157-163.

23

Scandura, A. (2016). University–industry collaboration and firms’ R&D effort. Research Policy, 45(9), 1907-1922.

Salles-Filho, S. (2002) Política de Ciência e Tecnologia no I PND (1972/74) e no I PBDCT (1973/1974). Revista Brasileira de Inovação, v. 1, n.2.

Schwartzman, S. (1979) Formação da Comunidade Científica no Brasil. São Paulo: Nacional. Schwartzman, S. (2001). Um espaço para a ciência: a formação da comunidade científica no Brasil (Vol. 1). Simon Schwartzman.

Suzigan, W.(1996) Experiência histórica de política industrial no Brasil. Revista de Economia Política, v. 16, n. 1, janeiro-março, pp. 5 – 20.

Suzigan, W. (2000) Indústria brasileira: origem e desenvolvimento. Campinas; São Paulo: Editora da Unicamp; Hucitec.

Suzigan, W.; Albuquerque, E.M. (2008) A interação entre universidades e empresas em perspectiva histórica no Brasil. Texto de Discussão, Cedeplar-UFMG, março.

Suzigan, W.; Furtado, J. (2006) A Institucionalidade da Política Industrial e Tecnológica: Problemas, Desafios, Propostas. II Congresso Brasileiro de Inovação na Indústria . São Paulo, 23-25 de abril.

Suzigan, W.; Rapini, M.; Albuquerque, E.M. (2011) A changing role for universities in the periphery. Texto para Discussão, Cedeplar/UFMG.

Suzigan, W.; Szmrecsányi, T.J.M.K. (1996) Os investimentos estrangeiros no início da industrialização no Brasil. História Econômica da Primeira República, Sã Paulo, Ed. Hucitec, p. 261-283.

Tavares, M. D. C. (1972). Da substituição de importações ao capitalismo financeiro: ensaios sobre economia brasileira. Biblioteca de ci ncias sociais. Economia Biblioteca de ci ncias socias (Zahar Editores).

Tidd, J.; Bessant, J.; Pavitt,K. (2001) Managing innovation: Integrating techenological, market and organizational change. 2a ed. John Wiley &Sons.

24

Velho, S. (1996) Relações universidade-empresa: desvelando mitos. Campinas, Editores Associados.

Versiani, F. R.; Suzigan, W. (1990) O processo brasileiro de Industrialização: uma visão geral. Série Textos Didáticos, Texto n°10. Brasília, Universidade de Brasília, Departamento de Economia. Villela, A. V.; Suzigan, W. (2001) Política do governo e crescimento da economia brasileira: 1889-1945. Brasília, IPEA.

25

Chapter 1 – Which are the weaknesses to

improve innovation process in emerging

countries? An analysis of the Brazilian case

INTRODUCTION

Emerging countries are pursuing the maturation of their economic development, and innovation is a key point at this process. Considering that, it becomes important to understand which are the internal and external issues that inhibit the development of innovation on these countries. Therefore, this paper aims to investigate the points that encumber the innovation consolidation inside companies located in emerging countries. These issues will be explored using data from the last three editions of the Innovation Research (PINTEC) conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the database includes data from 2006 to 2014.

Innovation is a complex activity that demands from companies a combination of internal and external factors creating a favorable environment for the generation of new technologies and knowledge. Externally it is important to be embedded on a consolidated innovation system to support the knowledge generation, funding and incentives. Internally, innovation process requires the development of specific resources and competencies to organize the internal structure, promote creativity and establish clear guidelines and processes. At the same time, being embedded in an environment that supports and invests in the generation of new knowledge and technologies and promotes the formation of qualified human resource, is essential to ensure the ideal conditions to develop this process (Nelson, 2006; Freeman and Soete, 2008).

In this sense, it becomes relevant to understand the constriction points for the consolidation of innovation inside companies. However, according to Fagerberg and Verspagen (2009), innovation studies are mostly concentrated on the explanation of the phenomenon on developed countries while a smaller part is dedicated to emerging countries. There is a long debate about the constrictions faced on developing countries regarding their Innovation Systems’ problems like policies, lack of relationships between actors, science development and investments. But the internal issues and their impact on the innovation production are still uncovered.

Based on the idea that the barriers to innovation can be divided by revealed and deterring barriers (D’Este et al., 2012), this study showed that innovation of Brazilian firms is not impacted by the barriers, since they present a low innovation effort. Even though, the activities evolving