Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfdj20

An International Journal for All Aspects of Design

ISSN: 1460-6925 (Print) 1756-3062 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfdj20

Table of Contents

To cite this article: (2019) Table of Contents, The Design Journal, 22:sup1, (i)-(xix), DOI: 10.1080/14606925.2019.1598132

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2019.1598132

Published online: 31 May 2019.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 30

i

Table of Contents

Introduction

Louise Valentine, Joanna Bletcher and Leon Cruickshank

TRACK 1.

Hard Hats and Bare Feet:

Understanding opportunity creation between design and entrepreneurship

THEME: New Business

Divide, Switch, Blend. Exploring two hats for industry entrepreneurship 19-35 and academic practice-based textile design research

Cathryn Hall and Rebecca Earley

To Be or Not to Be. The Servitization Dilemma and the Role of Design 37-49

Ion Iriarte, Maya Hoveskog, Alazne Alberdi, Maite Anaya and Maitane Mazmela

Designers Designing Businesses. Understanding how designers 51-63 create enterprises

Simone Gaglione and A İdil Gaziulusoy

Systemic incubator for local eco-entrepreneurship to favour 65-83 a sustainable local development. Guidelines definition

Chiara Battistoni and Silvia Barbero

Design-Led Innovation Strategies of Family Entrepreneurs. 85-98 Case-based Evidence from an Emerging Market

Selin Gülden and Özlem Er

Design Thinking Driven Interdisciplinary Entrepreneurship. 99-110 A Case Study of College Students Business Plan Competition

Rui Li, Zhenyu Cheryl Qianb, Yingjie Victor Chen andLinghao Zhang

How can Design Thinking promote entrepreneurship in young people? 111-121

Ester Vala, Itsaso González, Nagore Lauroba and Amaia Beitia

Designing Craft Opportunity. An Entrepreneurial Approach 123-135 To Creating the Craft Scotland Summer Show

ii

The Contribution of Design and Prototyping to Enhancing Organisational 137-146 Growth, Management and Entrepreneurship

Fraser Bruce and Seaton Baxter

The Beauty of Design Thinking – is there a Small Beast in the Box 147-161

Poul Rind Christensen and Suna Løwe Nielsen

Implementing design thinking as didactic method in entrepreneurship 163-175 education. The importance of through

Anna Kremel and Katarina Wetter Edman

A Darker Side of Creative Entrepreneurship 177-188

Adrian Wright, Dorota Marsh and Louise McArdle

Realising the value of open innovation in policy making. 189-201 Equipping entrepreneurs for valuation work

Roger Whitham, David Pérez, Katy Mason and Chris Ford

Entrepreneurship and Innovation Design in Education. An educational 203-215 experience to train the new entrepreneurial Designers

Andrea Gaiardo

Design as a Catalyst for Innovation in Irish Industry. Evolution of the Irish 217-228 Innovation Voucher Initiative within Design+ Technology Gateway

Lynne Whelan, Gemma Purcell, Jack Gregan and Declan Doyle

Design within Social Entrepreneurship. A Framework to reveal 229-241 the use of Design in interdisciplinary spaces

David Pérez, David Hands, Edward McKeever and Roger Whitham

Designing Your Future – 21st Century Skill-Set for Industrial Designers. 243-259 The Case Study of Israel Design Field

Dana Schneorson, Elad Persov and Roee Bigger

Italian Yachts Restoration. Possible tools for the ‘new’ business 261-275 of nautical heritage

Giulia Zappia

Models of Collective Working. Insights on the Scottish Context 277-293

Catherine Docherty, Sue Fairburn and David McGillivray

Design Thinking for Entrepreneurship in Frugal Contexts 295-307

Lisbeth Svengren Holm, Maria Nyström Reuterswärd and Godfrey Nyotumba

iii

TRACK 2.

A Healthy Attitude Towards Risk:

disobedient design research for health and wellbeing

THEME: Health and Wellbeing

Designing in highly contentious areas. Perspectives on a way 309-330 forward for mental healthcare transformation

Daniela Sangiorgi, Michelle Farr, Sarah McAllister, Gillian Mulvale Martha Sneyd, Josina Elilzabeth Vink and Laura Warwick

Designing better hip protectors. A critical and contextual review 331-345 examining their acceptance and adoption in older populations

Simon Richard Andrews

Combining design research with microbiology to tackle drug-resistant 347-358 infections in different home environments in Ghana. Challenging the

boundaries of design thinking

Emmanuel Tsekleves, Andy Darby, Collins Ahorly, Dziedzom De Souza, Roger Pickup and Daniel Boakye

Designed with Me. Empowering People Living with Dementia 359-369 infections in different home environments in Ghana. Challenging the

Euan Winton and Paul Anthony Rodgers

How smell can help visually impaired in health and well-being 371-386 infections in different home environments in Ghana. Challenging the

– a cognitive experiment

Anran Feng, Rui Li, Yingjie Victor Chen and Lu Din

Unpacking two design for health living lab approaches for more 387-400 infections in different home environments in Ghana. Challenging the

effective interdisciplinary collaboration

Steve Reay, Claire Craig and Nicola Kayes

Ethics by Design. Exploring Experiences of Harmony and 401-416 Dissonance in Ethical Practice

Angela Tulloch, Tara French and Leigh-Anne Hepburn

Analysis of the pilot survey INKLUGI about aging and disabilities 417-427 to promote Inclusive Design in industry

Arantxa González-de- Heredia, Daniel Justel, Ion Iriarte, Amaia Beitia and Jesús Hernández-Galán

iv

Rethinking how healthcare is conceptualised and delivered 429-444 through speculative design in the UK and Malaysia

Emmanuel Tsekleves, Min Hooi Yong, Clarissa Ai Ling Lee Sabir Giga, Jung Shan Hwang, Sian Lun Lau

Life Café. A Co-Designed Method of Engagement 445-461

Helen Elizabeth Fisher, Claire Craig and Paul Chamberlain

Designing Cognitive Ergonomics Features of Medical Devices. 463-474 Aspects of Cognitive Interaction

Mariia Zolotova and Angela Giambattista

Moving beyond an Interdisciplinary paradigm 475-486

Jackie Malcolm, Vicki Tully, Christopher Lim and Rodney Mountain

Crafting Textile Connections. A mixed - methods approach 487-501 to explore traditional and e-textile crafting for wellbeing

Sara Nevay, Lucy Robertson, Christopher Lim, Wendy Moncur

A New Domestic Healthcare. Co-designing Assistive 503-516

Technologies for Autonomous Ageing at Home

Guiseppe Mincolelli, Silvia Imbesi, Michele Marchi and Gian Andrea Giacobone

Addressing Stigma in the Design of a Physical Device 517-537

and Digital App for Pelvic Floor Exercises

Edgar R. Rodríguez Ramírez, Helen Andreae and Mailin Lemke

Enabling people to lower barriers with a co-design prototyping 539-551 approach.Sex education for upper-elementary students at home

Jisun Lee, Hyeryung Cho, Jihye Chung and Younjoon Lee

The Problem with Problems. Reframing and Cognitive Bias in 553-574

Healthcare Innovation

Samantha Hookway, Mia Fay Johansson, Anton Svensson and Bowman Heiden

Health and Wellbeing. Challenging Co-Design for Difficult 575-587 Conversations, Successes and Failures of the Leapfrog Approach

Roger Whitham, Leon Cruickshank, Gemma Coupe, Laura Wareing and David Pérez

Uncovering Nuance. Exploring Hearing Aids and Super Normal Design 589-599

v

The Soft Touch: Design vs. Disruption 601-613

Sara Nevay, Christopher S.C. Lim and Gary Gowans

Homeostasis sanatoris. A meaningfulness-driven product that 615-626 stimulates physiological healing processes

Angie Henríquez Martínez and Santiago De Francisco Vela

Falling UP to Recovery. Co-created practice for holistic mental 627-640 health care in Scotland

Drew Max Walker, Louise Valentine and Tracy Mackenna

Conversations between procedural and situated ethics. Learning 641-654 from video research with children in a cancer care ward

Piet Tutenel, Stefan Ramaekers and Ann Heylighen

Value Creation Through Service Design in a Healthcare Environment 655-668

Rasa Pamedytyte and Canan Akoglu

Home healthcare devices. Challenge of CPAP design for effective 669-681 home treatment

Noemi Bitterman, Katerina Klimovich and Giora Pillar

Ethics and Risk. Doing Design Research with People in Care Homes 683-694

Emma Gieben-Gamal

Project scale and the wicked problem in Fourth Order design 695-705

Richard Herriott

User Experience of Brazilian Public Healthcare System 707-721 A case study on the accessibility of the information provided

Emilene Zitkus and Claudia Libanio

TRACK 3.

SOCIAL CIRCLES:

How design, social innovation and the circular economy can create

and foster disruptive change

THEME: Sustainable Communities

Debate through design. Incorporating contrary views 723-735

on new and emerging technologies

vi

Social packaging. Design for wide sustainability 737-749

Marco Bozzola and Claudia De Giorgi

Co-living as a means to re-engagement. A literature review 751-762

Dora Karadima and Spyros Bofylatos

Geographical Context Influence on Co-Design Practice 763-776

Between Indonesia and the UK Context

Andi Setiawan, Nick Dunn and Leon Cruickshank

Collaborative governance in the sharing economy. 777-788

A case of free-floating bicycle sharing with visualized analyzation

Jingrui An, Linghao Zhang, Rui Li and Yingjie Victor Chen

Investigation into how each stakeholder plays a role at 789-801 different levels of granularity to realise a long-term

service design project

Younjoon Lee, Jeyon Jung and Seunghoon Kwak

Hybrid zero waste design practices. Zero waste pattern 803-819 cutting for composite garment weaving and its implications

Holly McQuillan

Counter-narratives Towards Sustainability in Fashion. 821-833 Scoping an Academic Discourse on Fashion Activism

through a Case Study on the Centre for Sustainable Fashion

Francesco Mazzarella, Helen Storey and Dilys Williams

Traditional Maker Practices and Sustainable Futures. 835-848

The implications of expertise

Stuart Walker, Martyn Evans and Louise Mullagh

Living Design. The future of sustainable maker enterprises: 849-862 a case study in Cumbria

Louise Mullagh, Stuart Walker and Martyn Evans

Co-designing Pathways to Opportunities for Young People 863-883 in the North West of England

Laura Wareing, Paul A.Rodgers and Nick Dunn

Slow knowledge in the ‘real world’. Using slow practice to 885-900 actively engage commercial collaborators in doctoral research

vii

Bridging the double-gap in circularity. Addressing the 901-914 intention-behaviour disparity in fashion

Alana M. James, Lizette Reitsma and Mersha Aftab

Systemic Design for territorial thinking. Circular urban 915-929 transitions for post-industrial cities

Carolina Giraldo Nohra and Silvia Barber

Neo-Local design. Looking at ‘our local contexts’ as potential resources 931-946

Nicolò Ceccarelli

Can we help as designers to build relevant spaces for meaningful 947-965 dialogue through storytelling as a tool for local empowerment?

A case of study in the Colombian Pacific

María Barón

Craft and Design Partnerships in the Chilean Context. 967-979 A Critical Perspective

Magdalena Cattan Lavin

Design Thinking for Progress. Initial insights from an evolving 981-995 design - led business support programme for Scotland

Jen Baillie

Addressing the Dialogue between Design. Sorting and Recycling 997-1013 in a Circular Economy

Essi Karell and Kirsi Niinimäki

To keep, or not to keep? That is the question. Studying divestment 1015-1028 from a cross-cultural approach

Ana Gabriela Encino-Muñoz, Mark Sumner, Pammi Sinha and Bruce Carnie

“Use what you have to secure what you have not” 1029-1039 On Design for and from Autonomy

Paola Pierri

Collaborative Circular Design. Incorporating Life Cycle Thinking 1041-1055 into an Interdisciplinary Design Process

Kate Goldsworthy and Dawn Ellams

Building Bridges. Design Researchers Making Podcasts to Support 1057-1070 Internal Collaboration in an EU Horizon 2020 Scientific Programme

viii

Designing an Appropriate Technology for Revitalising Traditional 1071-1086 Craft Practice. Case study: Indonesian Stitch Resist Dyeing

Bintan Titisari, Muriel Rigout, Tom Cassidy and Alice Dallabona

TRACK 4.

Where is the Control?

Machines, Democracies and Post-human Design

THEME: Artificial Realities

Spilltime. Designing for the relationship between QS, CO2e 1087-1100 and climate goals

Lizette Reitsma, Stina Wessman and Sofie Nyström

Considering Haptic Feedback Systems for a Livable Space Suite 1101-1116

Torstein Hågård Bakke and Sue Fairburn

Data as a medium for inheritance and creativity of traditional 1117-1133 design. A case study on data-drive modern creative design of

ancient Chinese catering utensils

Rong Han, Hong Zhang, Rui Li and Chunfa Sha

Forget the Singularity, its mundane artificial intelligence that 1135-1146 should be our immediate concern

Franziska Pilling and Paul Coulton

Beyond Average Tools. On the use of ‘dumb’ computation and 1147-1161 purposeful ambiguity to enhance the creative process

Philippa Mothersil and V. Michael Bove

Aural Textiles. Hybrid practices for data-driven design 1163-1175

George S. Jaramillo and Lynne J. Mennie

Using Twitter Bots to Critically Question the Belief Systems 1177-1186 of College-Aged Republicans and Democrats

Zack Tucker

Networking with Ghosts in the Machine. Speaking to the 1187-1199 Internet of Things

ix

Design Research through simulated social complexity. An agent- 1201-1214 based proposal to the construction of design knowledge

Juan Salamanca, Juan de la Rosa and Gerry Dekersen

Cyborg-Computer Interaction. Designing new senses 1215-1225

Muhammet Ramoğlu

Critical Design in Daily Life. Lifelike Products 1227-1234

Irem Cakiroglu and Cigdem Kaya Pazarbasi

Computational by Design, towards a co-designed material 1235-1248 culture. A design tool

Viktor Malakuczi

TRACK 5.

Designing to Learn:

The Heroics of Running Together

THEME: Learning Together

Materialising the Studio. A systematic review of the role of the 1249-1265 material space of the studio in Art, Design and Architecture Education

James Corazzo

Market as Manufactory. Making Communities 1267-1285

Paul Micklethwaite, Kieran O’Connor and Samantha Elliot

Deconstructing Design Research 1287-1303

Paul A. Rodgers, Loura Conerney and Francesco Mazzarella

Measuring the impact of strategic design learning experience 1305-1315 long after the classroom delivery

Noemi Sadowska and Dominic Laffy

Design Education. University-industry collaboration, a case study 1317-1332

Benedita Camacho and Rui Alexandre

Code Blue. Design and the Political/Resuscitating Civics 1333-1344

x

A Reflection upon Herbert Simon’s Vision of Design in The Sciences 1345-1356

of the Artificial

Xinya You and David Hands

Redesigning Tools for Knowledge Exchange. An Improvement Framework 1357-1371

Rosendy Galabo and Leon Cruickshank

Design skills for environmental risk communication. Design in and design 1373-1385 of an interdisciplinary workshop

Matthew David Lickiss and Lydia Cumiskey

Learning by design. How engagement practitioners use tools to stretch 1387-1397 the creative potential of their citizen participation practice

Hayley Alter, Roger Whitham, Frank Dawes and Rachel Cooper

Identifying Racialized Design to Cultivate a Culture of Awareness in Design 1399-1407

Lisa E. Mercer and Terresa Moses

Games as a Catalyst for Design for Social Innovation. Unlocking 1409-1422 legendary tools

Aslihan Tece Bayrak

Bodygramming: Embodying the computational behaviour as 1423-1437 a collective effort

Jussi Mikkonen

Tools for building consensus on goals 1439-1452

Mithra Zahedi and Virginie Tesser

Interdisciplinarity of Ph.D. students across the Atlantic. A Case of 1453-1466 Interdisciplinary Research Team Building at the Student Level

Jinoh Park, Byungsoo Kim, Boyeun Lee, David Hands and Traci Rose Rider

Investigating the Next Generation of Design Researchers 1467-1480

Paul A. Rodgers, Francesco Mazzarella and Loura Conerney

Applying Design Fiction in Primary Schools to Explore Environmental 1481-1497 Challenges

Deborah Maxwell, Toby Pillatt, Liz Edwards and Rachel Newman

Running with scissors in Business Management Education. A 1499-1514 collaborative auto-ethnography on designing pedagogical interventions

with an art-maker and an academic stills tutor

xi

The Role of Empathic Design Research in the Prototyping of Interactive 1515-1527 Visualizations

Eunmi Moon, Sheila M. Schneider, Priscilla Ferronato, Miriam Salah, Stan Ruecker and Deana McDonagh

Co-design in mental health; Mellow. A self-help holistic crisis planning 1529-1542 mobile application by youth, for youth

Elise Hodson, Mastaran Dadashi, Ramon Delgado, Connie Chisholm Robert Sgrignoli,and Ronale Swaine

TRACK 6.

Co-Designing with Nature Towards Resilience and Diversity

THEME: Ethical Resilience

Natural minerals. A family on the move, but where is the last stop? 1543-1554

Beatrice Lerma and Doriana Dal Palù

A Respectful Design Framework. Incorporating indigenous knowledge 1555-1570 in the design process

Lizette Reitsma, Ann Light, Tariq Zaman and Paul Rodgers

Implications of the Bio-inclusive Ethnic on Collaborative and 1571-1586 Participatory Design

Emīlija Veselova and А İdil Gaziulusoy

Gaming for Active Nature Engagement. Animal Diplomacy Bureau: 1587-1602 designing games to engage and create player agency in urban nature

Robert Phillips and Kaylene Kau

Atlantic Wonder Exploring Nature and Design in Madeira Island 1603-1617

Valentina Vezzani, Susana Gonzaga and Elisa Bertolotti

Nature-Centered Design. How design can support science to explore 1619-1628 ways to reconstruct coral reefs

Ezri Tarazi, Haim Parnas, Ofri Lotan, Majeed Zoabi, Asa Oren Noam Josef and Nadav Shashar

Using the SDGs to Nurture Connectivity and Promote Change 1629-1646

xii

Implementing bio-design tools to develop mycelium-based products 1647-1657

Noam Attias, Ofer Danai, Ezri Tarazi, Idan Pereman and Yasha J. Grobman

Designing Transitions Bottom-Up. The agency of design in formation 1659-1674 and proliferation of niche practices

Elif Erdoğan Öztekin and A. İdil Gaziulusoy

Co-designing Mobile Collection Points with Older Persons to Promote 1675-1686 Green Attitudes and Practices in Hong Kong

Alex Pui-yuk King

The role of design in discovering speculative futures materials for local 1687-1695 revaluation. Investigation of the methodology

Valentina Coraglia and Claudia De Giorgi

Climate Anticipation. Working towards a design proposal for urban 1697-1714 resilience and care

Jennifer M. Z. Cunningham and Sue Fairbairn

The Role of Philosopher Designer in Defining New Attitude towards Nature 1715-1722

Zahra Mohammadganjee and Somayyeh Shahhoseiny

The unintended consequences of embedded values in socio-technical 1723-1734 systems. A critical reflection using formal analysis of speedometers in

customer vehicles

Juan de la Rosa and Stan Ruecker

Ecocene Design Economies. Three Ecologies of Systems Transitions 1735-1745

Joanna Boehnert

TRACK 7.

Happy Accidents:

Serendipity in Design Research

THEME: Open Track

Happy Affect. Harnessing Chance and Uncertainty in Design Practice 1747-1760

Akari Nakai Kidd and Kelly Salchow MacArthur

Steering Gently. Crowd management with a non-confrontational philosophy 1761-1774

xiii

Renewing technology-driven materials research through an 1775-1785 experimental co-design approach

Kirsi Niinimäki

Applying Storytelling Method into the Flow of User Experience Design 1787-1806 to Innovate with Serendipity

Jianbin Wu, Linghao Zhang, Zhenyu Cheryl Qian and Rui Li

Designing for emergent interactions. Strategies for encouraging emergent 1807-1820 user behaviour & serendipitous research findings

Kristina Maria Madsen and Peter Vistisen

Serendipity? The Inspiration of Medieval Masons in Cathedral Floor-plan Design 1821-1840

Chaoran Wang and Michael Andrew Hann

Surrendering to The Now. Improvisation and an embodied approach 1841-1851 to serendipity.

Ariana Amacker

Serendipity as a Catalyst. Knowledge Generation in Interdisciplinary Research 1853-1869

Riikka Townsend and Jussi Mikkonen

Kinetic morphologies. Revealing opportunity from mistake 1871-1882

Ana Piñeyro

Ah, I see what you didn’t mean. Serendipitous interpretations of analogue 1883-1897 and digital ideation

Philip Ekströmer and Renee Wever

Serendipity in the Field. Facilitating serendipity in design-driven field 1899-1912 studies on ship bridges

Synne Frydenberg, Jon OlavEikenes and Kjetil Nordby

Designing Branded Atmospheres. Nature-inspired, multisensory spatial 1913-1927 brand experiences for consumer electronics retail stores

Monika Malbasic and Youngok Choi

Design Thinking for Innovation. Stress Testing Human Factors 1929-1939 in Ideation Sessions

xiv

Attempts, Failures, Trails and Errors. Notes on an exhibition of failed 1941-1956 prototypes and rejected projects

Tincuta Heinzel, Hillevi Munthe, Teresa Almeida, Corina Andor, Anca Badut

Camille Baker, Anna Biro, Shih Wei Chieh, Renata Gaui, Maria Paulina Gutierrez Arango Shary Kock, Ebru Kurbak, Aline Martinez Santos, Ionut Patrascu, Veerle Pennock Ioana Popescu, Zoran Popovici, Afroditi Psarra, Natacha Roussel, Annette Schmid Kate Sicchio, Vitalii Shupliak, Rebecca Stewart, Milie John Tharakan, Giulia Tomasello Bram van Waardenberg, Pauline Vierne, DZNR Design Studio

TRACK 8.

Faster, Better, Stronger: Design in the Digital Economies THEME: Digital Economies

A New Method to Evaluate Good Design for Brand Recognition in the 1957-1971 Digital World

Itsaso Gonzalez, Ester Val, Daniel Justel, Ion Iriarte and Ganix Lasa

Industrial Design Education in the Age of Digital Products 1973-1982

Işıl Oygür and Zeynep Karapars

Improving Design Software Based on Fuzzy Kano Model. A Case Study 1983-1992 of Virtual Reality Interior Design Software

Kaidi Xu, Yingjie Victor Chen, Linghao Zhang and Rui Li

Social Design Fiction. New Methods for the Design of Emerging Technology 1993-2005

Matthew Pilling, Daniel Richards, Nick Dunn and Allan Rennie

The Transformative Effects of Digital Technologies on the Product Design 2007-2017 Practices of Servitizing Manufacturers

Deniz Sayar and Özlem Er

Document while-doing. Documentation tool for Fab Lab environments 2019-2030

Iván Sánchez Milara, Georgi V. Georgiev, Jani Ylioja, Onur Özüduru and Jukka Riekk

Synthesizing Opposites. Technical Rationality and Pragmatism in Design 2031-2044

xv

Fruitful Gaps in Digital Literacy. Interpreting gaps in digital literacy among 2045-2059 stakeholders in collaborative design research projects as an evolving

innovative capacity

Vashanth Selvadurai, Peter Vistisen and Claus Andreas Foss Rosenstand

Questioning the social and ethical implications of autonomous vehicle 2061-2071 technologies on professional drivers

Richard Morton, Daniel Richards and Paul Coulton

Strategies for Empowering Collective Design 2073-2088

Bijan Aryana, Ehsan Naderi and Gersimos Balis

Service orientation-based tool for assessing and improving service design 2089-2103 and development practices in manufacturing industry

Janne Pekkala, Sanna Peltonen and Miia Lammi

Inclusive Design for Immersive Spaces 2105-2118

Michael Crabb, Daniel Clarke, Husam Alwaer, Michael Heron and Richard Laing

Creativity 4.0. Empowering creative process for digitally enhanced people 2119-2131

Carmen Fruno and Marita Canina

Spimes Not Things. Creating a Design Manifesto for a Sustainable Internet 2133-2152 of Things

Michael Stead, Paul Coulton and Joseph Lindley

POSTERS

Talk The Talk, Walk The Walk. Challenging the perception of the value 2153-2154 of verbal tools within design education environments

Glen O'Sullivan

Thinking, design. A construct of (and for) change) 2155-2156

Paul Magee, Andree Woodcock

Renaissance. Chinese design in nine words 2157-2158

Yeqiu Yang, Guerrini Luca

Are Local Creative Industries More Global than We Think? A study 2159-2160 of creative and digital firms based at Baltic Creative in Liverpool

CM Patha, Nick Dunn, Roger Whitham

xvi

MATUROLIFE. Combining Design Innovation and Material Science 2161-2162 to Support Independent Ageing

Tiziana C. Callari, Louise Moody, Paul Magee, Danying Yang, Gulay Ozkan, Diego Martinez

Urban Signs. The relationship between signage and road accidents 2163-2164

Santiago Osnaya Baltierra

Educational design and business programs. An opportunity to promote 2165-2166 socio-economic paradigm shifts?

Pilar Lara

Fear of Missing Out = Missing out. (or: things I saw while you were 2167-2168 distracted by your phone)

Lisa Fontaine

Compassionate Systems Design. A framework for sustainable cultures 2169-2170

Charlene Samantha Sequeira

Sonic Flock. Using textile birds to start conversations within a 2171-2172 Dementia Friendly Community in the Outer Hebrides

Lucy Robertson

A-DIARIO. Human encounters collection, Stories that we have 2173-2174 lived or could live, small tales that help us imagine other lives

and build common worlds

María Paula Barón Aristizabal

Design for Change 2175-2176

Beth White

Designing the Affective Material Palette. Using materials to explore 2177-2178 the experience of systems and technologies designed to aid

behaviour change

Marion Lean

WORKSHOPS

From User Insights to Evidence-Based Strategy Selection. Designing 2179-2183 for Behaviour Change with the Behavioural Lenses Approach

Sander Hermsen, Dirk Ploos van Amstel, Tim van Eijl, Reint Jan Renes

Using digital agile communities in industrial design 2185-2188

xvii

Hidden Treasures. Discovering the Design Potential of Natural 2189-2195 History Collections

Michelle Fehler, Clint Penick

Designing Diverse Design Dogmas, Deliberately. Using aspects 2197-2201 of Design on its practitioners to set the challenge of imagining

alternative ways of designing

Matthew Lee-Smith

Co-designing Improvements of Knowledge Exchange Tools 2203-2207

Rosendy Galabo, Leon Cruickshank

"All You Can Eat". Prototyping Speculative Food Futures 2209-2213

Emmanuel Tsekleves, Serena Pollastri

Design/health. Exploring tensions in design and health for more 2215-2219 effective trans-disciplinary collaborations

Claire Craig, Stephen Reay, Ivana Nakarada-Kordic

Experimenting productive disagreement between research and 2221-2223 project in design. A basemap for action

Marie-Julie Catoir Brisson, Thomas Watkin

Nature-Centred Design. Exploring the path to design as Nature 2225-2229

David Sánchez Ruano

Risk & Reward. Exploring Design's role in measuring outcomes 2231-2234 in health

Gemma Wheeler, Joe Langley, Nathaniel Mills

POSITIONING PAPERS

Designers Should Evaluate Their Work. You say those are scissors 2235-2238 you are running with, but do they event cut?

Sander Hermsen

Being safe is scary. Increasing precariousness in co-design 2239--2241

Spyros Bofylatos

Design-driven obsolescence 2243-2246

xviii

Felicitous Design Concept. Harmonising marketing and design on product, 2247-2250 process and strategy levels

Nasser Bahrami, Bijan Aryana

Skin deep. Perceptions of human and material ageing and opportunities 2251-2255 for design

Ben Bridgens, Debra Lilley, Hannah Zeilig, Caroline Searing

Designing New Socio-Economic Imaginaries 2257-2261

Chris Speed, Bettina Nissen, Larissa Pschetz, Dave Murray-Rust, Hadi Mehrpouya, Shaune Oosthuizen

Lessons from Designing for End-of-Life 2263-2266

Marieke H. Sonneveld

Sharp edges, blunt objects, clean slices. Exploring design 2267--2273 esearch methods

Andrew Morrison, Henry Mainsah, Karianne Rygh

Design Meets Death. A case of critical discourse and 2275--2280 strategic contributions Farnaz Nickpour RESEARCH PROPOSALS

A Semiotic Rosetta Stone Research Project. Defining designer- 2281-2289 centric semiotic practice

Dave Wood, Shelaph O'Neill

Improvement Matrix. Prompting New Ways of Thinking about 2291-2293 Knowledge Exchange

Rosendy Galabo, Leon Cruickshank

Playing with uncertainty. Experiential design and sense making 2295-2298 for radical futures

Bridgette Engeler, Wendy Schultz

WALKS

Dundee Dice Walk 2299-2302

xix

Take a GANDER. Gathering Accessibility Needs by Doing 2303-2306 Explorative Research

Michael Crabb, Rachel Menzies, Garreth W. Tigwell, Daniel Clarke, Christopher Lim, Cara Henderson

Walking Heterotopias 2307-2312

Erika Renedo Illarregi

A Walk in the Woods. Promoting Chance and Wellbeing at EAD 2019 2317

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rfdj20

An International Journal for All Aspects of Design

ISSN: 1460-6925 (Print) 1756-3062 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rfdj20

New Domestic Healthcare. Co-designing Assistive

Technologies for Autonomous Ageing at Home

Giuseppe Mincolelli, Silvia Imbesi, Michele Marchi & Gian Andrea Giacobone

To cite this article: Giuseppe Mincolelli, Silvia Imbesi, Michele Marchi & Gian Andrea Giacobone (2019) New Domestic Healthcare. Co-designing Assistive Technologies for Autonomous Ageing at Home, The Design Journal, 22:sup1, 503-516, DOI: 10.1080/14606925.2019.1595435To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2019.1595435

Published online: 31 May 2019.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 18

Copyright © 2019. The copyright of each paper in this conference proceedings is the property of the author(s). Permission is granted to reproduce copies of these works for purposes relevant to the above conference, provided that the author(s), source and copyright notice are included on each copy. For other uses please contact the author(s).

New Domestic Healthcare. Co-designing

Assistive Technologies for Autonomous

Ageing at Home

Giuseppe Mincolelli

a*, Silvia Imbesi

a, Michele Marchi

a, Gian Andrea Giacobone

aa Department of Architecture, University of Ferrara, Via Quartieri 8, 44121 Ferrara, Italy

*Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]

Abstract: Ageing is connected with increased chronic psychological and physical

disabilities, which are today delayed to older ages than in the past. The constant

growth in number of older people in our society creates a larger demand of goods

and services related to home care, due to the willingness of the elderly to live at home

remaining autonomous as long as possible. Using a Human Centred Design method,

this research aims to support ageing in place and to extend independence of older

people through appropriate technological strategies for families, reducing both costs

and risk factors of caregiving. Quality Function Deployment tool and Co-Design

technique are the main approaches that have led the design process, including older

people in every decision-making step. The final result is an assistive IoT ecosystem,

which provides at the same time a customizable healthcare service to the elderly and

a home care management system to their caregivers.

Keywords: Inclusive Design, Elderly, Ageing in place, Assistive environments,

Internet of Things.

1. Introduction & context

Older people are a rapidly growing proportion of the world’s population because the life expectancy of our society is getting longer than in the past. The constant growth of this trend creates a larger demand of goods and services related to healthcare and safety issues (WHO, 2015). In fact, ageing is connected with increased chronic morbidity, diseases and functional disabilities, and it is possible to evidence that psychological and physical disabilities are delayed to older ages than in the past (Freedman et al., 2002). Consequently, this phenomenon puts great pressure on social welfare systems that will face the challenge to provide the standard of care both for longer time and to more people from all over the world in the next years.

Concurrently, home has become the primary setting for short-term and long-term caregiving provided mainly by families and secondarily by friends or neighbours. The boundaries between hospital and home have become blended, where the volume of home care supported by informal caregivers have already provided over 80% of home care to dependent older people (Binstock & Cluff, 2000) and the role of the family as primary caregiver is projected to continue and expand in an

5

ageing society. This trend will become more evident because the majority of older people wants to age in their contexts, to remain autonomous, active and independent as long as possible and live at home surrounded by their family and friends (Rantz et al., 2005). In this case, for the elderly and their families, autonomy consists of decisional control and choice in shaping their own personal life, where institutional care is perceived to be a last resort. The move to senior residential housing and later to a long-term care facility is often the result of inadequacies of the home to meet the changing needs of older people due to decline in health and self-care abilities, loneliness, accessibility barriers within the home and the surroundings, the unavailability of necessary services and a poor quality of care (Lecovich, 2014). In particular, this tendency is increased by the families that are not able to provide essential support to their parents because of long distances and work commitments (Campanini, 2004), subsequently producing uneasiness in both parts.

Understanding the role of home in providing daily care is very important to develop appropriate and effective strategies to support families and to reduce both costs and risk factors associated with caregiving. Thus, it is necessary to find new solutions that can facilitate ageing in place, promoting a longer independence for older people. Ageing in place develops in four interrelated dimensions: a physical dimension that can be seen and touched like home or neighbourhood; a social dimension involving relationships with people and the ways in which individuals remain connected to others; an emotional and psychological dimension, which manifests with a sense of belonging and attachment; a cultural dimension, which relates with older people’s values, beliefs, ethnicity, and symbolic meanings. Hence it means that ageing issues are not referable to the physical sphere only, but it is also necessary taking in account the psychological sphere, because it includes factors that contribute to preserve the social identity, the sense of personhood and a level of independence, according to both the living environment and social interactions (Gitlin, 2003).

2. Objectives

The current scenario in which older people require constant assistance and the availability of caregivers is insufficient, an important challenge for designers is to rethink and redesign the domestic environment toward new ways of providing home care service and preserving ageing in place. Digital technology can be a useful tool to tackle health issues by supporting elder care with ubiquitous services, especially aimed to the most fragile categories of the elderly (Mincolelli et al., 2017: B). If we look at the Internet of Things, for example, scientific community is still investigating about what effects and positive impacts may assistive agents have on people who need daily home assistance (John Clarkson & Coleman, 2015). In fact, some researches are focusing nowadays on assistive environments, because they can easily monitor and support people in their environments through an intelligent sensor network, which collects, records, analyses and shares health data (Goodman et al., 2007).

This paper shares the same objective and it presents a research project specifically developed to enable ageing in place, helping people to stay healthy and autonomous for longer time at home. ‘Habitat’, the project examined in this contribution, is a multidisciplinary design research focused on Inclusive Design for older people. It aims to develop an assistive environment through an IoT-based platform that provide a customizable healthcare service to its residents. The objective is to create a smart domestic environment that can be used not only with a medical purpose, but also for social entertainment. This dual purpose drives the research towards creating a smart system that can be less intrusive than assistive-robot agents and less annoying than a non-predictive reminder tools, in such a way that technology can be hidden into the home and act only when its intervention is necessary. The overall IoT platform expects an integrated system – with several sensors integrated

5 5

into traditional objects, such as radios, armchairs, lamps and so on – able to monitor older people and consequently to offer the right support for improving their life quality, according to a predictive analysis of their monitored parameters. In order to put the attention on user needs, this research has used participatory techniques and human-centred approaches throughout all steps of the design process.

‘Habitat’ is funded by POR FESR 2014-2020 program of Emilia-Romagna Region in Italy and it is developed by an interdepartmental research group composed of several partners coming from both university and industry. The entire team is composed by:

• (a) CIRI-ITC (Centre for Industrial Research of the University of Bologna), which is the head partner of this research, specialized in radio frequency systems. Its task is to design and realize an indoor localization system that can interact both with users and smart objects, integrating itself in the domestic space. The aim is to monitor elderly at home, in order to preventing possible dangerous situations.

• (b) CIRI-SDV (Life Sciences and Health Technologies of the University of Bologna), which is expert on technical validation of inertial sensors. Its task is to realize both the digital system of SEPA module (a communicating semantic protocol that interconnects the smart objects together) and the wearable inertial sensor for the analysis of indoor and outdoor movements of older people.

• (c) TekneHub (Tecnopolo of Ferrara, belonging both to the Thematic Platform Construction of the Emilia-Romagna’s high technology network and to the University of Ferrara), which is the leading team of the entire design process, specialized in Human Centred Design methodologies. Its task is to develop design solutions for every smart object taking in consideration the voice of users but also every technical or engineering constraint arising from prototypes of other partners;

• (d) ASC Insieme, which is the public entity for management of Personal Services in the Province of Bologna. It has several adult day care centres scattered around Bologna. Its role is to make available several groups of users of its network and its facilities to TekneHub for organising several Co-Design workshops.

• (e) Ergotech, which is an industrial company expert in designing ergonomic furnishing. Its role is to provide its industrial know-how for realizing and testing the final prototypes. • (f) mHealth, which is a spin-off of the University of Bologna, specialized in the fields of

motion analysis and wearable sensors for monitoring, assessment and rehabilitation of the motor function. Its role is to provide its experience in data management for wearable devices.

• (e) Romagna Tech, which is competent in communication and dissemination of results. Its role is to spread and disseminate every result of ‘Habitat’ through their communication channels located in the territory.

The final objective of this relationship between industry and academy is to design a concrete project that can move beyond the sole research in order to transform itself into a great opportunity for industrial economy for all of the Emilia Romagna territory. Indeed, the common objective is to ideate a technological transfer from academic research to healthcare industry in order to maximize the probability of a real impact on our society.

5 6

3. Methodology

The entire scientific research has been structured inside the context of a Human Centred Design approach, which has been used in the design process to satisfy the needs of people. In a

multidisciplinary and complex project such as ‘Habitat’, it was fundamental utilizing this user centred method. Throughout this research a great challenge was taking into consideration every single expectation of users without compromising and affecting any design direction (by strategic,

technological or morphological conveniences). This effort has enabled ‘Habitat’ partners to develop usable, accessible and inclusive products for all the users involved.

One of the intrinsic difficulties was to find an operative tool that could permit to all partners – with different skills and competences – to communicate throughout all phases of the research. For this purpose, the Quality Function Deployment (QFD) was used as decision-making tool, in order to set up the ‘Habitat’ project in a structured way. Due to its correlation matrix, QFD tool compares emotional and qualitative user needs (voice of customers) with measurable characteristics of the expected product (voice of engineers), identifying the most important technical parameters that must be used to develop the final project. The main goal was to develop innovative and qualitative products, which simultaneously meet both qualitative and quantitative requirements of the users involved

(Franceschini, 2003).

Figure 1. An example of a QFD matrix. The 1st and the 2nd areas show user needs (voice of customers) and their weights. The

3rd area displays the product specifications (voice of engineers) that may satisfy user needs. The 4th area displays the

assessment of the relationship matrix between needs and technical parameters. The 5th area represents the competitive

benchmarking assessment. Based on the correlation matrix, the 6th area shows what are the most important characteristics

5

Although QFD is usually applied in marketing researches by industrial companies, this project has tried to use this model to lead the creative process of this research.

Within ‘Habitat’ project, the Co-Design practise has been used in support of QFD tool. Co-Design is a participatory and collaborative technique, used to enable stakeholders in making creative

contributions in the solution of a specific problem. In this case, the practise has involved all

categories of users (related to the project) in a collaborative process that has been useful to generate several ideas about the design of the final smart objects. Co-Design approach and its different ways for interacting with people have been decisive for the success of ‘Habitat’ project, for different reasons:

• The interactive and iterative involvement of users throughout design process has permitted to develop an assistive environment starting from the real needs of people involved. Due to this technique the research process has been capable of changing the perspective of the project, from designing 'for the users' to designing 'with the users'. People with different skills and operational levels (elderly, caregivers, physiotherapists, health operators, relatives) have worked together on the project, driving every criteria towards a common goal that was used for developing the final products;

• The involvement of users, from the early phases of the project, has contributed to

establishing a qualitative relationship with the elderly through time-structured recreational activities. Co-Design practise has been useful to shake the elderly out of their daily routines (often repetitive), producing in them a feeling of curiosity and resourcefulness;

• The participatory activity has permitted an exchange of knowledge between experts and users. On the one hand, the moderators have made the elderly more aware about healthier lifestyle (derived by correct posture, right nutrition, daily movement and so on) and on the other hand, older people have made experts more conscious about elderly conditions, through the description of their everyday life experiences;

• The sincere and authentic dialogue established with users has made the elderly sensitive towards new technologies and new interactive tools, which could concretely support them in their daily routines.

4. Process

As glimpsed in the previous paragraphs, the development of ‘Habitat’ have constantly involved predetermined users into a collaborative, iterative and interactive process made up by a continuous cycle of ideas generation, testing and validation (Rizzo et al., 2001). Co-design techniques and the Quality Function Deployment tool have been utilized during the research to analyse and process user needs. Every step has been carried out by TekneHub's design team, which has managed and

conducted all activities that have been useful to establish the guidelines of the final prototypes. This chapter describes every phase of development process that regards the ideation of ‘Habitat’

platform and its smart objects.

4.1 User and needs analyses

The first phase of research consisted in a careful analysis of the expected context, in which ‘Habitat’ will be inserted. This step was carried out by TekneHub together with the other partners, especially ASC Insieme. Then, several focus groups, direct interviews and questionnaires were organized including various stakeholders, in order to identify the main users who would have more interest in using the IoT platform. The main participants were: self-sufficient seniors, non-self-sufficient seniors,

5

caregivers, relatives, health operators, physiotherapists and decision-makers. The activities involved roughly 100 people, which provided about 500 needs. Once data gathering was completed, a QFD matrix was created for each expected smart object of 'Habitat' platform. QFD analysis was performed through a meticulous sorting of the most important needs, selecting about 20-25 significant needs for each single smart object. In each QFD matrix, the selected needs were processed together with measurable product characteristics (identified by all partners) of the corresponding smart object (Mincolelli et al., 2017: B). The analytic correlation between needs and product specifications produced a technical assessment about the importance of every technical characteristic of each single smart objects. The final results were useful to define the design guidelines of the expected prototypes, which TekneHub would design during the following phases.

4.2 Co-Design activities

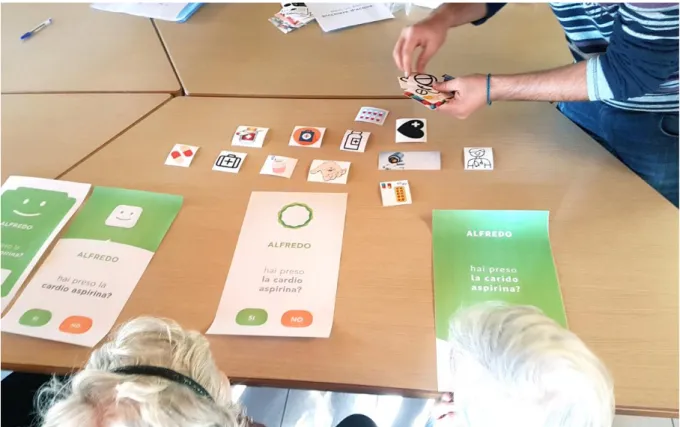

Figure 2. Two prototype solutions deriving from many participative activities with users, performed during the first Co-Design workshop. On left there is a chair elaborated through the opinions of users, whilst on right, a caregiver is testing the position of the inertial sensor. ASC Insieme's day centre, Casalecchio di Reno Bologna, Italy, 19th April 2017.

After the analysis of user needs, two Co-Design activities were performed together with some of the people already involved in the early stage of research. All Co-Design workshops were held at the ASC Insieme's adult day care centre in Casalecchio di Reno, Bologna, Italy. The Co-Design activities involved 12 families who were composed both by self-sufficient and non-self-sufficient seniors over 65 years old. Every family included a caregiver who was either a relative or a professional health operator. TekneHub's team and ASC Insieme's staff were the moderators of the two workshops. The two collaborative workshops contributed to define the final prototypes in collaboration with the main users. The active participation of older people gathered several insights, which were useful to better define proper solutions towards the main problems and needs encountered at old age (Slegers, 2015).

The first workshop permitted to delineate the early concepts and the first morphological shapes of the final products. Three main working tables were constituted with the specific intent to acquire as

5

much information as possible about the smart object: the first one was on both the indoor localization system and the inertial sensor, the second one was on the smart chair for monitoring seniors' movements and posture; the third one was on the visual interface of the IoT platform. The participative activities were conceived for analysing daily habits and behaviours of the elderly in their homes through brainstorming and user journey maps, which defined how the assistive environment would satisfy their necessities. The final results have permitted to better understand shapes and functions of all smart objects. Through participative activities it has been possible to evaluate the level of acceptance of inertial and tracking sensors ‘wearability’ and the level of usability of the visual interface provided by the digital system. The first Co-Design workshop collected also emotional aspects of older people. Indeed, through an empathy map, it has been possible to gather several conditions of fear, frustration, satisfaction and pleasure – either related to their personal habits or to their relations with family or friends – which have been able to improve the expected quality of the overall project. After the first workshop, every consideration of users was considered in design phase. Several concepts were realized, which were analysed and evaluated with the same users, in order to evaluate the real correspondence between their previous expectations and their present opinions.

Figure 3. Older people are analysing ‘Habitat’ interface in terms of readability, aesthetics and usability during the second Co-Design workshop. ASC Insieme's day care centre, Casalecchio di Reno Bologna, Italy, 04th December 2017.

In the second Co-Design workshop, several practical assessments were performed to evaluate interactions between older people and physical objects. The main goal was to analyse strengths and weaknesses of the functional, technological and aesthetic characteristics of every smart object. This Co-Design activity was particularly useful to better improve both usability and accessibility of ‘Habitat’ interface. The workshop was performed by observing the elderly during the task-flow analysis of the digital service, as some of their impressions were easily identified from many cues elicited by their expressed behaviours (Brown, 2015). Any critical issue or problem encountered during the interaction with 'Habitat' platform was revised.

51

4.2 Testing phase

In the final phase of research, a usability test was executed both to evaluate 'Habitat' service and to verify the fifth level of Technology Readiness Level (TRL), adopted by European Commission to estimate technological maturity of European-funded projects (EU, 2014; Hedér, 2017). According to the European framework, the test has expected to validate the overall ‘Habitat’ project within a simulated or a real space environment. In order to achieve this goal, the test was held at the ASC Insieme's adult day care centre (real space environment) and it was deliberately performed by an external usability expert who had been never involved in the project, in such a way that the evaluation would not be affected by personal biases. Another objective was to evaluate the qualitative level of both usability and desirability of the overall system and its smart objects. The entire session involved 19 participants to whom ‘Habitat’ had been presented at the early stage. Within this specific phase, two complementary methodologies were used to inspect the project: heuristic evaluation analysis and individual interviews. In particular, two different interview scripts were designed, based on the two specific categories of users involved during the test (self-sufficient seniors and non-self-sufficient seniors with their respective caregivers). The interviews involved: 7 self-sufficient seniors; 4 couples composed of caregivers and non-self-sufficient seniors; 2 caregivers (interviewed individually); 2 non-self-sufficient seniors (interviewed individually). Time allocated to each interview was one hour and a half for each user and two hours for each couple. At the end, all users were able to finish their testing session and subsequently every consideration was reported into a final report provided by the usability expert. The document was important both to evaluate strengths and weaknesses of the overall system and to verify if the Technology Readiness Level of ‘Habitat’ had been reached.

5. Results

Starting from necessities and emotional aspects of users – but also involving themthroughout Co-Design activities – it was possible to realize every functioning prototype, taking into account at the same time, functional and morphological product characteristics requested by the elderly. ‘Habitat’ system is a modular and scalable IoT-based platform for supporting ageing in place, designed to not compromise both the life quality of older people and the intimacy of personal home. The overall system is essentially composed by four smart objects. A smart chair, an indoor localization system and an inertial sensor constantly gathering data from the domestic environment while a digital interface processes that information and then takes operative decisions based on health status and indoor position of the elderly. Every smart object can be localized by unique identifiers that provide to the system their indoor position (Mincolelli et al., 2017: A). To make the assistive environment as acceptable as possible, the service has been designed not only for healthcare, but also to stimulate the emotional dimension of users, providing entertainment and enjoyment through its user

experience (Dohr et al., 2010). ‘Habitat’ offers also a social support to families and health operators, helping them to remotely monitor their parents or patients through its IoT platform. Moreover, some industrial partners have tried to integrate the solutions of this research technology in the objects of their future product lines. Also, to use the system in different contexts, each smart object is expected to work together with its ecosystem, but also stand-alone.

5.1 Digital 'frame' interface

‘Habitat’ interface looks like a picture frame that can be hooked on the wall. The hardware of the interface is designed to be recognised as a part of the home furniture. Inside of it, there is a SEPA module (a communicating semantic protocol, utilized for connecting the smart objects together),

511

which connects the software to the other smart objects. ‘Habitat’ software monitors health condition of users and manages their daily-life activities through the analysis of their personal data (provided by localization system, inertial sensor and smart chair). If the system finds critical issues on the elderly's life status, 'Habitat' interface can either communicate the problem to caregivers or suggest users to change their conditions through visual notifications. The 'Habitat' interface works on a 17" LCD touch-screen and shows simple messages designed to be very easy to read and understand by older people.

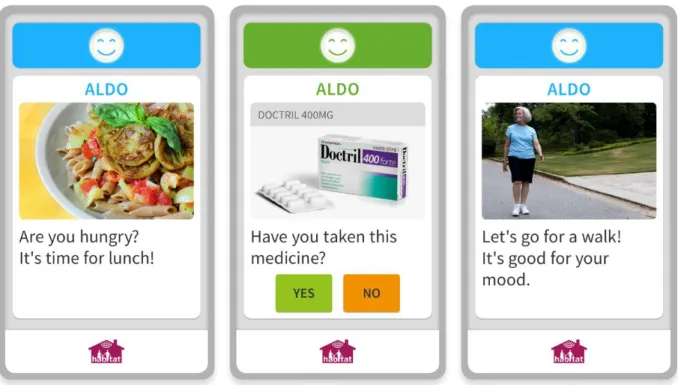

Figure 4. Some screens of ‘Habitat’ interface. The blue category indicates temporary advice to suggest the elderly to do specific practical actions and the green typology interacts with them in order to monitor their routines or health conditions.

Every message of the interface is composed by: a short phrase about a specific notification; a large image corresponding to the meaning expressed in the text; a coloured bar that identifies the type of message. The colour categories are two: light blue is used for temporary advice that try to push the elderly to do an action (for example drinking, eating, walking, changing posture or sleeping); green indicates the interactive messages, which are used by the system to ask the elderly to report some information about their daily routines (for example if they are fine or if they have already taken medicines at particular times). Also, at the end of the day, the interface requests to the elderly other data about their status, asking them to rate (on a level from one to five) the quality of their daytime, in base of five essential parameters: nutrition, mood, health, rest time and interpersonal

relationships. All gathered data are used by the system to monitor and to improve health conditions of the elderly. The service provides also a mobile version designed for both the elderly and

caregivers. It extends the service over the digital 'frame' and outside the domestic environment for older people and it mainly helps caregivers to monitor the elderly everywhere at any time. The mobile application shows health parameters of each senior monitored by 'Habitat' and it provides to caregivers correct warning messages in case of critical issues.

5.2 Smart chair

The smart chair has been realized in collaboration with Ergotech who has provided its know-how about ergonomic armchairs for the elderly. This smart object is a traditional domestic seat, in which

51

several load cells were embedded in its feet, seat frame and backrest, in order to monitor different sitting parameters. Real-time data (about sitting posture and sedentary time) are sent to the digital 'frame' by an Arduino board, to create personal feedbacks for users. Information is processed by the software to improve either health with physical activities (like walking) or posture in a correct way.

Figure 5. Functioning prototypes of ‘Habitat’ system: the wearable tag for localizing position (on left); the reader lamp of the indoor localization system (on top-right); the wearable inertial sensor for tracking elderly movements (on bottom-right).

5.3 Indoor localization system & inertial sensor

The indoor localization system is based on Radio-Frequency IDentification (RFID) and it is composed by two device categories: reader sensors for localization of people and smart object in the

environment and recognition tags (Paolini et al., 2017). The recognition tags for artefacts are embedded into their electronic circuits, whilst the tags for people are wearable and should be worn on the upper part of the body to facilitate identification. The reader sensors are embedded into wall lamps or shelves in order to minimize the technological impact on the home spaces and they are utilized to monitor the position of older people. According to physical and mental abilities of older people, the indoor localization system can be divided into safe zone and unsafe zone. This

configuration can prevent wrong access to the elderly into particular risky areas of the house (for example bathroom), warning caregivers in time through specific alert messages.

Inertial sensor is another wearable device, which monitors dynamic motion of older people inside and outside the house. In order to have correct motion tracking, the wearable sensor should be worn dorsally at waist level, in correspondence of the L5 vertebra. The sensor analyses activity time or sedentary time of the elderly and it is able to warn caregivers in case of critical events (such as fallings). The inertial sensor works in collaboration with the indoor localization system, to provide qualitative data about health of the elderly.

51

6. Conclusions

Figure 6. Simulated environment of ‘Habitat’ system performed within Expo Sanità exhibition. Bologna, Italy, 18th-21th April 2018. The image shows the functioning prototypes of 'Habitat' system: digital 'frame' interface (on top-left); smart chair (the light blue chair on left); indoor localization system inside the lamp (on top-right).

The research has allowed to realize a multidisciplinary project that has promoted the development of technical-fields-crossing solutions. As expected in the objectives, the final result has produced a beta version of 'Habitat' software and all functioning prototypes, which are utilized for evaluating both functionality and usability of the IoT platform during testing phase. In addition, the conception of desirability has been introduced within the performed tests, in order to evaluate adaptability level of 'Habitat' toward different needs manifested by older people, which can change over time in base of their personal ageing process. In this case, desirability refers to the willingness of the elderly to get older in a scenario in which 'Habitat technology is present and it is used to improve life quality. During tests, the final report has taken note of all considerations of the elderly about the smart objects. Personal evaluations were positive, because almost all of the 19 people involved declared to be satisfied while interacting with the products. Specifically, the smart object with the highest appreciation (100%) is the inertial sensor, which has obtained excellent results both on aesthetic level (it has been perceived as intimate) and on colour and fabric customization. During tests, the inertial sensor was able to assess specific characteristics of balance, gait, postural transfers, and turns and sent data to 'Habitat' system in background and in real-time. Information was used to evaluate the number of steps, detect fallings and distinguish sedentary time from the active one. Also, algorithms that identify fallings showed possible improvements in order to recalibrate sensor parameters and avoid eventual false alarms or system misses.

The reader sensor of the indoor localization system has had a high level of appreciation (90%), because it could be easily integrated into any domestic context as a lamp or a shelf. However, it has been recommended to increase variety of colour and size during production, in order to increase flexibility of use. Tests showed that the reader sensor allowed angular detection in a scanning zone

51

from -45° to 45° in the azimuth plane and it was able to localize the recognition tags in real-time with centimetre-level accuracy. For a correct installation and calibration of the reader sensor, a simple pre-scanning of the domestic environment was needed. Instead, the recognition tag has been the smart object that has showed the biggest room for improvement (60% of approval). Older people reported that they would prefer reduce weight and dimensions of the case, because it was not very comfortable to wear because of its large antenna (5x5 cm). In an advanced phase of the product development, it has been also advised to assess these changes in other evaluating tests.

The smart chair has been appreciated for its comfort and aesthetics (80% of satisfaction). The product derives from a chair model already engineered, in which sensors and a wireless system – that communicates with the digital 'frame' interface – are integrated. Data communication with the central system worked correctly, but in some cases, many tests highlighted some anomalies related to some messages (for example notify an incorrect posture), because sometime the algorithm – that analyses and processes data from load cells – resulted too sensible to recognize user behaviours. The digital 'frame' interface has been considered pleasant in terms of use (80% of satisfaction) and customizable regarding superficial painting and displayed messages (based on needs and habits of users). Evaluating tests of the digital 'frame' and its visual notifications were performed through some expected scenarios (such as to notify incorrect posture, to remember drinking water, eating, walking, sleeping, or to fill in the daily report) whereby 'Habitat' had been designed for. During tests, when a particular situation of a specific scenario occurred (for example to advise older people to walk), the 'frame' displayed the corresponding notification message on time, which could be visible on its interface and, at the same time, on the mobile devices of both the elderly and caregivers. Interacting with 'Habitat' resulted enjoyable by the elderly and the system was perceived more as a companion, rather than an intrusive element creating anxiety or a sense of guilt. Some visual reminders such as "drinking water" or "walking" were indicated both as a useful support to remember tasks and an element of involvement in maintaining healthy lifestyle. However, it was recommended to match the different visual messages that came from the displayed graphic interface with audible feedbacks. The daily report was considered a useful tool to analyse both health status and life quality of the elderly in the long term, but some frictions arose during the interaction with the questions it asked, because the process required too much steps to confirm choices.

In addition, the evaluating tests were important because they showed the possibility to identify three possible service solutions of 'Habitat' platform to adopt at home, based on three different steps of ageing, which the service has to manage: self-sufficient senior; partially self-sufficient senior; non-self-sufficient senior. Due to the autonomy of non-self-sufficient seniors, it has been noted that 'Habitat' may be equipped only with the mobile application and the inertial sensor, which can be used only as reminder for healthy activities or scheduled tasks (for example taking medicines or going to the doctor appointment). While, the second category (partially self-sufficient senior) may include all the other smart objects (smart chair, indoor localization system and digital 'frame' interface), in order to extend the service also to home caregiving. In this solution, the system is more present in the everyday life of the elderly and it can warn caregivers in case of critical issues. Instead, for the last category of non-self-sufficient seniors, 'Habitat' may be used even as a warning system, where the platform is completely managed by caregivers, who can constantly monitor the elderly and help them to do their daily activities. In this case, the mobile application for older people is eliminated and all messages are displayed only on the digital 'frame'. These solutions may assist every category of senior during their ageing, without compromising habits or creating constraints to whom still live autonomously and do not need permanent caregiving compared to non-self-sufficient seniors.