Paroxetine drops versus paroxetine tablets:

evaluation of compliance in a six-month study

Valutazione della compliance al trattamento con paroxetina in gocce

rispetto alle compresse in uno studio di sei mesi

RAFFAELLA ZANARDI, LAURA COLOMBO, ELISA MARCHEGGIANI, DAVID ROSSINI, DARIO DELMONTE, MARA CIGALA FULGOSI, CHIARA GAVINELLI, CRISTINA COLOMBO

E-mail: [email protected]

Department of Clinical Neurosciences, San Raffaele-Turro Hospital, Milan, Italy

SUMMARY. Aims. Literature data show that one third of patients discontinue antidepressant therapy within the first month of treatment. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether paroxetine liquid solution 10 mg/ml may influence adherence in patients receiving long-term treatment. Methods. 71 subjects affected by mood disorders or panic disorder were monitored for six months. The study sample was divided into two groups: controls (n=33) maintained their own therapy with paroxetine tablets; 38 patients maintained the same dosage of paroxetine, but shifted to liquid formulation 10 mg/ml. Compliance and general wellness were evaluated with the Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) and the World Health Organization Quality of Life questionnaire (WhoQol). Data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA). Results. Significant differences were found in MARS scores: patients on oral solution 10 mg/ml showed an improvement of compliance month by month. In addition, age, formulation and quality of life had a significant im-pact on patient compliance. Significant correlations were found between MARS and quality of life. A specific paroxetine for-mulation could be a variable able to influence adherence to psychopharmacological treatment. The same consideration can be made for quality of life, sex and age that showed a trend towards improved adherence when compared with controls. In particular, the WhoQol subscale analysis of delta scores showed a significant difference in self-perception of quality of life in patients treated with paroxetine either in tablet or drop formulation. Discussion. Formulation in drops 10 mg/ml is equally effective to tablets, but it may allow patients having a higher cognition and control on drug assumption.

KEY WORDS: compliance, long-term treatment, depression, formulation, panic disorder.

RIASSUNTO. Scopo. I dati presenti in letteratura mostrano come un terzo dei pazienti trattati con farmaci antidepressivi non sia costante nell’assunzione della terapia nel primo mese di trattamento. L’obiettivo dello studio è stato quello di valutare se la for-mulazione liquida di paroxetina 10 mg/ml potesse influenzare l’aderenza al trattamento in pazienti trattati con una terapia a lun-go termine. Metodi. 71 soggetti affetti da disturbo dell’umore o disturbo di panico sono stati monitorati per sei mesi. Il campione è stato diviso in due gruppi: il gruppo di controllo (n=33) ha mantenuto la terapia con paroxetina in compresse; 38 pazienti, pur mantenendo lo stesso dosaggio di paroxetina, sono passati alla formulazione liquida 10 mg/ml. La compliance e il benessere gene-rale sono stati rispettivamente valutati con Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) e World Health Organization Quality of Life (WhoQol). I dati sono stati analizzati tramite l’analisi della varianza (ANOVA) e l’analisi multivariata della covarianza (MANCOVA). Risultati. Differenze significative sono state riscontrate nei punteggi alla scala MARS: il gruppo che assumeva la soluzione orale 10 mg/ml mostrava un incremento di compliance che aumentava nel tempo. Anche l’età, la formulazione e la qua-lità della vita influenzano significativamente la compliance. Sono state trovate correlazioni significative tra MARS e quaqua-lità della vita, valutata tramite la scala WhoQol. Una specifica formulazione di paroxetina potrebbe essere una variabile in grado di in-fluenzare l’aderenza al trattamento psico-farmacologico. La medesima considerazione potrebbe essere fatta per la qualità della vi-ta, il sesso e l’età, variabili che sembrano in grado di incrementare l’aderenza al trattamento quando confrontate con il gruppo di controllo. In particolare, l’analisi dei delta delle sottoscale della WhoQol evidenzia una differenza significativa nella percezione del-la propria qualità di vita tra i pazienti dei due gruppi. Discussione. La formudel-lazione in gocce del farmaco è efficace quanto quel-la in compresse, ma sembra portare i pazienti ad avere maggiore consapevolezza e controllo sull’assunzione del farmaco. PAROLE CHIAVE: compliance, trattamento a lungo termine, depressione, formulazione, disturbo di panico.

INTRODUCTION

Mental disorder is associated with enormous per-sonal suffering for affected patients, great distress for their family and friends and major socio-economic costs (1,2). Antidepressant medication reduces acute symptoms (3,4) and its premature discontinuation in-creases the risk for relapse (5). Nevertheless, between 30% and 83% of patients who begin antidepressants discontinue treatment prematurely (5-7).

More than other diseases, depression is associated with high rates of relapse and recurrence during a pa-tient’s lifetime (5). For this reason, a life-long antide-pressant treatment is recommended (8).

The treatment of depressive episodes has 3 phases (3,5):

1. the goal of the acute treatment phase is relief of symptoms and the length of this phase depends on responsiveness to treatment and the need to find an optimal regimen;

2. continuation therapy is recommended for a period of 4-9 months following the acute phase to allow more complete resolution of the episode and to pre-vent the relapse that is the re-emergence of the ex-isting episode (5);

3. the need for long-term maintenance phase depends on the number of prior episodes (9,10) and other risk factors such as associated anxiety (11,12). Recent data show that nearly one third of patients discontinue quickly antidepressants within the first month of treatment (13,14) and 44% of patients dis-continue therapy within the first three months (15,16). Lingam and Scott (17) reviewed data published from 1976 to 2001 regarding the prevalence of psychotropic medication non-adherence in affective disorders: the authors showed that for these disorders the incidence of non-adherence ranged from 10% to 60% with a me-dian of 40%. They further assured that the trend of non-adherence had not changed significantly in recent years (14,16-21).

In parallel with a development of a notion that de-pression is an illness requiring a continuous and regu-lar medication treatment, the psychiatric community started to focus its attention on compliance with anti-depressant medication regimens (22). Many studies quantify the percentage of subjects who early interrupt antidepressant therapy, but only few ones focused on the causes of this diffused behaviour.

Compliance has been defined as the extent to which a person’s behaviour in terms of taking medication or executing a lifestyle changes coincides with medical or heath advice (23). Because this term is sometimes

per-ceived as too authoritarian, other terms have appeared sporadically in the literature such as adherence, main-tenance, self-regulation, alliance or concordance (24). Non-compliance can be manifested in several ways (24,25): 1) failure to have the prescription filled; 2) having the prescription filled but failing to take the medication; 3) not follow the frequency or dosage in-structions of the prescription; 4) errors of purpose or use of inadvertent combinations.

There appears to be a broad range of reasons why patients discontinue antidepressants prematurely. Bul-loch and Patten found that simply forgetting to take medication was the main reason for patient non-ad-herence (26).

Willingness to take the prescribed antidepressant is tightly linked to beliefs about medication. For example, patients report that treatment effectiveness and barri-ers are among the most critical aspects of depression care (27). Data also show that pre-treatment percep-tions of the benefits of and barriers to antidepressants predict initial medication adherence, and that primary care patients frequently attribute their early discontin-uation to their perception that they do not need an an-tidepressant (16). Moreover, some authors (16) sug-gested that severe daytime somnolence was significant-ly associated with earsignificant-ly non-adherence, while fatigue, blurred vision, difficulty in falling asleep, feeling anx-ious or jumpy, changes in appetite, and weight gain were significantly associated with late non-adherence. Long-term adherence may gradually diminish as clini-cally improved patients begin to conclude that they no longer need medication or become less willing to con-tinue tolerating previously acceptable medication problems such as sexual side effects. Maintenance phase may also be relatively more affected by fears of potential long-term cumulative or insidious adverse ef-fects such as personality changes, addiction or toxicity (27). Deterrents to adherence may also include other personality disorder symptoms, above all those includ-ed in DSM-IV Cluster B personality disorders (28).

Aikens et al. (29) suggested that perceived necessi-ty of medications is related to age, thus older patients reported greater perceived necessity.

Although it is generally assumed that elderly pa-tients are more likely to be non-compliant than younger patients because of the high number of med-ications prescribed and complexity of dose regimens, this relationship has not yet been fully established (9). Compliance in elderly patients remains a focus of terest because the large number of medication used in-creases the risk of side effects.

Horne (30) has asserted that beliefs of medication are “the hidden determinant of treatment outcome”,

thus, in relation to antidepressants, beliefs appear to be a major predictor of adherence.

Demyttenaere concluded that antidepressant adher-ence improves when patient-clinician communication focuses on patient’s personalized belief about how to best manage their depressive symptoms, which often conflict with medical models of treatment. Thus, ad-herence may improve if clinicians carefully clarified the patient’s specific concerns (e.g. adverse effects, ad-diction, personality changes, financial costs, stigma) and then offered a conservative dosing (29).

The strength of the physician-patient relationship, the severity of psychopathology, side effects, and pa-tient education and personality may be considered predictors of antidepressant medication adherence (31). Consistent evidence indicates that a therapeutic alliance with the patient through educational tech-niques increases behavioural compliance, physicians may be able to enhance patient adherence to antide-pressant treatment by offering detailed information about their treatment regimens (10,16).

Paroxetine is indicated for the treatment and pre-vention of depression and anxiety disorders. Paroxe-tine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and increases serotonin levels by inhibiting the reup-take transporters. Paroxetine is available as hydrochlo-ride (HCl) and as mesylate salt. Some patients may have difficulty in swallowing tablets and thus may be less likely to adhere to their medication regimen. Swal-lowing problems can occur for physical or psychologi-cal reasons. Physipsychologi-cal swallowing problems can be caused by abnormalities of the head and neck, age-re-lated degeneration of the esophagus, trauma or sur-gery, neurogenic or muscular disorders, or the side ef-fects of medications (32). Some patients may simply experience discomfort when trying to swallow tablets due to pill size or texture (33).

Navarro (34) found that orodispersible tablet for-mulations may improve compliance among patients with depression who have physical or anxiety-based swallowing difficulties, nausea, or limited liquid intake, and may also prove preferable for patients without these difficulties. Obviously, pill-swallowing problems can occur for a number of reasons and these may not be readily identified by patients. For such patients a liquid formulation of paroxetine could be beneficial and improve their compliance. Compliance to treat-ment protocol is crucial since long-term treattreat-ment of depression is important to prevent relapses (35).

The aim of this study was to evaluate wheter the re-cent introduction of paroxetine liquid solution 10 mg/ml into the Italian market may influence patient adherence to long-term treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

There is a growing body of evidence on the therapeutic efficacy of paroxetine: it is indicated for the treatment and prevention of depression and also for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder (36); more-over, it can be used during the acute phase of illness and for a long-term treatment during the maintenance phase.

The aim of this study was to evaluate how paroxetine formulation (tablet and drops) could influence adherence to long-term antidepressant therapy in a sample of pa-tients treated at the Department of Clinical Neurosciences of San Raffaele Hospital.

Paroxetine oral solution 10 mg/ml has been introduced into the Italian market as well as tablets; because adher-ence to treatment may also depend on medication sumption, we supposed that drops could be easier to as-sume than tablets. Our aim was to compare these two dif-ferent formulations to identify, if possible, when and who should be prescribed with one or the other formulation.

More than six months of euthymia were required for the inclusion in the study and all patients were treated with paroxetine tablets with different dosages.

The study sample consisted of 71 subjects (14 male and 57 female), 57 affected by mood disorder (44 major de-pressive disorder and 13 comorbidity of mood and panic disorder) and 14 affected by panic disorder. In case of co-morbidity, mood disorder is the principal diagnosis. They were monitored for six months and administered with a battery of self-administered scales in four consecutive times: at baseline, and after 1, 3 and 6 months.

Patients were divided into two groups: controls (n=33) maintained their own therapy with paroxetine tablets; pa-tients included in the control group participated in qualita-tive interviews and expressed a reluctance or refusal to shift to paroxetine liquid solution 10 mg/ml; the remaining 38 pa-tients maintained the dosage of paroxetine recommended by the physician, but shifted to the liquid formulation 10 mg/ml. After the first month, three patients preferred to come back to the tablet formulation because of a subjective nasty taste of drug and for greater convenience of tablets. No drop-outs were recorded in the control group.

Compliance was evaluated with the Medical Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) (35,37-39), a self-administered scale, at baseline, after the first month, after the third month and at the end of the study, as well as after six months from the shift. Wellness was evaluated using the World Health Organ-ization Quality of Life questionnaire (WhoQol). This scale evaluates the influence of four different variables on per-son’s life; from these depends subjective wellness: Psycho-logical Area, Physical Area, Interpersonal Relations and Environment. The addition of scores from these areas pro-vides a comprehensive score of quality of life perceived.

Before the inclusion in the study and at every step, the physician visited the patients and administered Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression and MADRS to test the eu-thymia.

RESULTS

Clinical and socio-demographic variables of the study population are shown in Table 1 and did not show any significant differences.

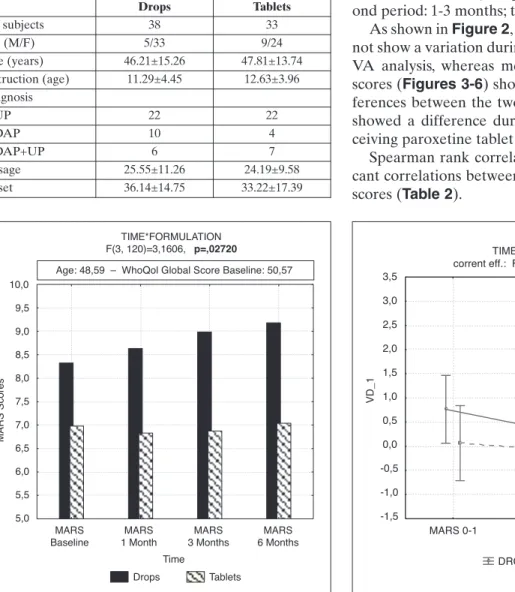

Repeated measure ANOVA showed significant dif-ferences (p<0.0272) in MARS scores during six months of monitoring between the two groups; in par-ticular, the group receiving oral solution 10 mg/ml showed an improvement of compliance month by month (Figure 1).

Analyzing MARS scores, we verified whether some clinical-demographic variables could affect adherence to treatment; MANCOVA analysis was performed

us-ing MARS scores as dependent variables, time as with-in factor, age and formulation and quality of life (total WhoQol score) at baseline as between factor. Results obtained showed how significant variables explained variance of compliance at baseline (p=0.011), and after the first (p<0.000), third (p<0.000) and sixth month (p<.000). Formulation significantly explained variance of MARS scores (λ di Wilks: p=0.000).

Post-hoc analysis confirmed significant differences in MARS scores between the two groups from the be-ginning to the end of the study period (LSD Fisher on: baseline (p=0.0036), and after the first (p=0.020), third (p=0.005) and sixth month (p=0.005).

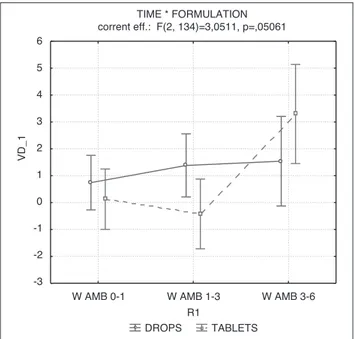

As MARS and WhoQol scores were different at baseline, we decided to analyze also the delta scores in order to point out the variation during the three peri-ods of observation (first period: baseline-1 month; sec-ond period: 1-3 months; third period: 3-6 months).

As shown in Figure 2, mean MARS delta scores did not show a variation during the time (p=0.41) in ANO-VA analysis, whereas mean WhoQol subscales delta scores (Figures 3-6) showed statistical significant dif-ferences between the two groups. Each WhoQol area showed a difference during the time for patients re-ceiving paroxetine tablet and drops.

Spearman rank correlation analysis showed signifi-cant correlations between MARS scores and WhoQol scores (Table 2).

Table 1. Clinical and socio-demographic variables of the stu-dy population Drops Tablets No. subjects 38 33 Sex (M/F) 5/33 9/24 Age (years) 46.21±15.26 47.81±13.74 Instruction (age) 11.29±4.45 12.63±3.96 Diagnosis UP 22 22 DAP 10 4 DAP+UP 6 7 Dosage 25.55±11.26 24.19±9.58 Onset 36.14±14.75 33.22±17.39 TIME*FORMULATION F(3, 120)=3,1606, p=,02720 Drops Tablets MARS

Baseline 1 MonthMARS 3 MonthsMARS 6 MonthsMARS Time 5,0 5,5 6,0 6,5 7,0 7,5 8,0 8,5 9,0 9,5 10,0 M AR S Sc or es

Age: 48,59 – WhoQol Global Score Baseline: 50,57

Figure 1. ANOVA, variation during the time in MARS scores.

TIME * FORMULATION corrent eff.: F(2, 134)=,89795, p=,40984

DROPS TABLETS

MARS 0-1 MARS 1-3 MARS 3-6 R1 -1,5 -1,0 -0,5 0,0 0,5 1,0 1,5 2,0 2,5 3,0 3,5 VD _1

Figure 2.ANOVA, variation during the time of mean delta MARS scores.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Our results showed how a specific paroxetine for-mulation could be one of many variables able to influ-ence adherinflu-ence to a psychopharmacological treat-ment. Also quality of life is another variable of inter-est: patients with higher scores in WhoQol are more open to change formulation and show a progressive TIME * FORMULATION corrent eff: F(2, 134)=3,0573, p=,05031 W AF 0-1 W AF 1-3 W AF 3-6 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 VD _1 DROPS TABLETS R1

Figure 3.ANOVA, variation during the time of mean delta Physical Area (AF) WhoQol scores.

DROPS TABLETS TIME * FORMULATION corrent eff.: F(2, 134)=2,9683, p=,05478 W AP 0-1 W AP 1-3 W AP 3-6 R1 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 VD _1

Figure 4.ANOVA, variation during the time of mean delta Psycho-logical Area (AP) WhoQol scores.

DROPS TABLETS TIME * FORMULATION corrent eff.: F(2, 134)=2,9736, p=,05450 W RS 0-1 W RS 1-3 W RS 3-6 R1 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 VD _1

Figure 6.ANOVA, variation during the time of mean delta Social Relations (RS) WHOQOL scores.

DROPS TABLETS TIME * FORMULATION corrent eff.: F(2, 134)=3,0511, p=,05061

W AMB 0-1 W AMB 1-3 W AMB 3-6 R1 -3 -2 -1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 VD _1

Figure 5.ANOVA, variation during the time of mean delta Environ-mental Area (AMB) WhoQol scores.

Table 2. Spearman rank correlation (p<0.05)

MARS WhoQol

Baseline 1 month 3 months 6 months

Baseline 0.311*

1 month 0.379*

3 months 0.405*

6 months 0.543*

improvement. Moreover, sex and age were found to in-fluence adherence to antidepressant therapy: women on paroxetine oral solution 10 mg/ml had higher MARS scores and a slighter improvement than men of the same group and controls, but the effect did not reach statistical significance. We also observed a trend in elderly people towards a slight improvement when compared to the control group.

As reported in our previous analysis, there was a statistical significant variation during time for mean delta WhoQol scores in each area. In particular, pa-tients receiving paroxetine in drops showed a stable self-perception of quality of life during the time, while patients receiving paroxetine in tablets showed a pro-gressive worsening of this parameter in each area.

These data go in the same direction as the following considerations. It may be hypothesized that patients choosing paroxetine in drops maintain an adequate self-perception, while patients receiving the tablet for-mulation tend to express a progressive demoralization with respect to their life conditions.

From a clinical point of view, the formulation in drops is equally effective to tablets, but it may allow patients to have a higher cognition, consciousness and control on drug assumption; in fact, patients who ac-cepted to change tablets with drops sustain that the lat-ter formulation is more simple to adminislat-ter than the former, making them sure to assume the appropriate dose according to their needs; conversely, attempts at dividing tablets may lead to inappropriate dosing. A liquid formulation of paroxetine (10 mg/ml) could of-fer a straightforward way to taper treatment by reduc-ing the dose drop by drop. An advantage of the liquid formulation is that it allows to adopt slow titration. This would allow a very gradual reduction in the plas-ma levels of paroxetine. The great benefit of this for-mulation is that it will allow the physician to design in-dividualized tapering off regimens to avoid withdraw-al symptoms (36).

Finally, three different areas affecting adherence to therapies can be identified: the main predictors of ad-herence (or non-adad-herence) to antidepressant treat-ment can be due to the physician, the patient, or spe-cific drugs. The physician may build a therapeutic al-liance with the patient, take a psycho-educational in-tervention, let alone regularly visit the patient during the follow-up. These behaviors can help the patient to feel sustained during the first period of treatment, when drugs do not provide positive effects on depres-sive symptoms and the patient asks to change therapy. By the patient depends motivation to begin and con-tinue treatment that has potential side effects or drug-drug interactions. Moreover, the formulation of drug-drug

assumption may influence treatment adherence and success but up to date there are insufficient data about a specific drug formulation.

The use of custom doses permits to minimize side effects. It also allows a better doctor-patient relation-ship and a greater continuity and constancy in therapy assumption. The patient may feel more involved in the choice of therapy, without suffering from it.

The choice of using paroxetine is due to the fact that it is one of the most prescribed drugs. In our sample, no patients reported side effects due to its anticholinergic effect (40).

Further studies are warranted to investigate the im-pact of the drop formulation using other drugs.

All subjects of our study sample received only paroxetine and they were clinically euthymic for at least six months before entering into the study. Al-though the use of hypnotic drugs was permitted (rarely), no patient took other psychotropic drugs dur-ing the follow-up.

These findings match the interest of the clinician in understanding the causes underlying discontinuation of antidepressant treatment. Further studies on larger samples and longer follow-up may provide more pre-cise answers about the impact of formulation type on patient compliance.

REFERENCES

Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER. The eco-1.

nomic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatr 1993; 54: 405-18.

Wells KB, Stewart A, Hays RD, et al. The functioning and well-2.

being of depressed patients: results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA 1989; 262: 914-9.

Depression Guideline Panel. Treatment of major depression. In: 3.

Depression in Primary Care. Vol. 2 Clinical Practice Guideline No. 5. Rockville, MD: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, and Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1993. AHCPR Publication 93-0550.

Maixner SM, Greden JF. Extended antidepressant maintenance 4.

and discontinuation syndromes. Depr Anx 1998; 8 (Suppl 1): 43-53. Melfi CA, Chawla AJ, Croghan TW, Hanna MP, Kennedy S, 5.

Sredl K. The effects of adherence to antidepressant treatment guidelines on relapse and recurrence of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatr 1998; 55: 1128-32.

Peveler R, Grorge C, Kinmonth A, Campbell M, Thompson C. 6.

Effect of antidepressant drug counseling and information leaflets on adherence to drug treatment in primary care: ran-domized controlled trial. BMJ 1999; 319: 612-5.

Bultman DC, Svarstad BL. Effects of pharmacist monitoring on 7.

patient satisfaction with antidepressant medication therapy. J Am Pharm Assoc 2002; 42: 36-43.

Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Perel JM, et al. Five-year outcome for main-8.

tenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49: 769-73.

Cramer JA, Rosenheck R. Compliance with medication regi-9.

mens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatr Serv 1998; 49: 196-201.

Demyttenaere K, Haddad P. Compliance with antidepressant 10.

therapy and antidepressant discontinuation symptoms. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000; 403: 50-6.

Ramana R, Paykel ES, Cooper Z, Hayhurst H, Saxty M, Surtees 11.

PG. Remission and relapse in major depression. Psychol Med 1995; 25: 1161-70.

Keller MB. The naturalistic course of anxiety and depressive 12.

disorders. Clin Neuropharmacol 1992; 15 (Suppl 1, Pt A): 171A-3.

Maddox JC, Levi M, Thompson C. The compliance with antide-13.

pressant in general practice. J Psychopharmacol 1994; 8: 48-53. Nemeroff CB. Improving antidepressant adherence. J Clin Psy-14.

chiatry 2003; 64 (Suppl 18): 25-30.

Venturini F, Sung J, Nichol M. Utilization patterns of antide-15.

pressant medications in a patient population served by primary care medical group. J Menaged Care Pharm 1999; 5: 243-9. Lin EH, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. The role of the primary care 16.

physician in patient’s adherence to antidepressant therapy. Med Care 1995; 33: 67-74.

Lingam R, Scott J. Treatment non-adherence in affective disor-17.

ders. Acta Psych Scand 2002; 105: 164-72.

Gumnick JF, Nemeroff CB. Problems with currently available 18.

antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry 2000; 61: 5-15.

Katon W, VonKorff M, Lin E, Bush T, Ormel J. Adequacy and 19.

duration of antidepressant treatment in primary care. Med Care 1992; 31: 67-76.

Simon GE, Von Korff M, Wagner EH, Barlow W. Patterns of an-20.

tidepressant use in community practice. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1993; 15: 399-408.

Shumann C, Lenz G, Berghofer A, Müller-Oerlinghausen B. 21.

Non-adherence with long-term prophylaxis: a 6-years naturalis-tic follow-up study of effectively ill patients. Psychiatry Res 1999; 89: 247-57.

Demyttenaere K. Risk factors and predictors of compliance in 22.

depression. Eur Neuropsycopharmacol 2003; 13 (Suppl 3): S69-S75.

Haynes RB. Introduction. In: Haynes RB, Taylor WD, Sacket DL 23.

(eds). Compliance in Health Care. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979.

Demyttenaere K. Compliance during treatment with antide-24.

pressants. J Affect Disord 1997; 43: 27-39.

Buckalew LW, Sallis RE. Patient compliance and medication 25.

perception. J Clin Psychol 1986; 42: 49-53.

Bulloch AG, Patten SB. Nonadherence with psychotropic med-26.

ications in the general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epi-demiol 2010; 45: 47-56.

Aikens JE, Nease DEJr, Nau DP, Klinkman MS, Schwenk TL. 27.

Adherence to maintenance phase antidepressant medication as a function of patient belief about medication. Ann Fam Med 2005; 3: 23-30.

Holma IA, Holma KM, Melartin TK, Isometsä ET. Treatment at-28.

titudes and adherence of psychiatric patients with major depres-sive disorder: a five-year prospective study. J Affect Disord 2010; 127: 102-12.

Aikens JE, Nease DEJr, Klinkman MS. Explaining patient’s be-29.

liefs about the necessity of harmfulness of antidepressants. Ann Fam Med 2008; 6: 23-9.

Horne R. Patients’ beliefs about treatment: the hidden determi-30.

nant of treatment outcome? J Psychosom Res 1999; 47: 491-5. Haynes RB, Wang E, DaMota Gomes M. Acritical review f in-31.

terventions to improve compliance with prescribed medications. Patients Educ Couns 1987; 10: 155.

McCulloch TM, Jaffe D. Head and neck disorders affecting swal-32.

lowing. GI Motility online; 2006. Available at: http://www.na-ture.com/gimo/contents/pt1/full/gimo36.html.

Overgaard AB, Hojsted J, Hansen R, Møller-Sonnergaard J, 33.

Christrup LL. Patients’ evaluation of shape, size and colour of solid dosage forms. Pharm World Sci 2001; 23: 185-8.

Navarro V. Improving medication compliance in patients with de-34.

pression: use of orodispersible tablets. Adv Ther 2010; 27: 785-95. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences 35.

of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2000; 157: 229-33. Van den Tweel ERW, Relleke M, Muniz Piniella P. Paroxetine 36.

oral solution is bioequivalent to paroxetine tablets: advantages of the solution. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007; 45: 611-6. Thompson K, Kulkarni J, Sergejew AA. Reliability and validity 37.

of a new Medication Adherence Rating Scale (MARS) for the psychoses. Schizophr Res 2000; 42: 241-7.

Darnell J, Murray M, Marz B, Weinberger M. Medication use by 38.

ambulatory elderly: an in-home survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 1986; 34: 1-4.

Garriety T, Lawson E. Patient-physician communication as a de-39.

terminant of medication misuse in older, minority women. J Drug Issues 1989; 19: 245-59.

Pae CU, Patkar AA. Paroxetine: current status in psychiatry. Ex-40.