Abnormal

Behaviours

in

Two

Captive

Brown

Bear

(Ursus

arctos

Linnaeus,

1758)

Females:

Individual

Differences

and

Seasonal

Variations

Abnormales

Verhalten

in

zwei

gefangen

Grizzlybär-Weibchen

(Ursus

arctos

Linnaeus,

1758):

einzelne

Unterschiede

und

saisonale

Variationen

Ana

I.

Soriano

a,∗,

Dolors

Vinyoles

a,

Carmen

Maté

b aDepartmentofAnimalBiology,UniversityofBarcelona,Barcelona,Spain bBarcelonaWaterCycle,AnonymousSociety,Barcelona,SpainReceived6September2016

Abstract

Abnormalbehavioursarecommonincaptiveenvironmentsthatnotsupplythephysicaland psycho-logicalneedsofanimals.Thereareanimals,likebrownbears,moresusceptibletodevelopabnormal behavioursduetotheirseasonalbiologyrelatedtofood,hibernationorreproduction.Thetwobrown bearUrsusarctosfemalesfromBarcelonaZoo,Spain,showedtwodifferentpatternsofabnormal behaviours.Theold♀displayedepisodesofbitingatreetrunkwhiletheyoung♀carriedout head-tossingevents.ThestudiedperiodwasfromMarchtoDecember2004dividedintoseasonalperiods: autumn,springandsummer.Atotalof63hoursofobservationswererecordedusingamulti-focal continuousmethod.Thetimeinvestedonabnormalbehaviourwashigherinspringfollowedby sum-merandautumninbothfemales.Theothervariablesrelatedtotheabnormalbehaviourstudiedwere duration,intensity,occurrenceandspaceusewhichalsoshowedstatisticallysignificantdifferences amongseasonalperiods.Theold♀spaceuseduringabnormalbehaviourwasinthesamezone mean-whiletheyoung♀showedstatisticallysignificantdifferencesamongseasonalvariationsandzones oftheenclosure.Theseresultsshouldbetakenintoaccounttoimprovethemanagementofbearsin zoologicalinstitutions.

Keywords: Episodes;Events;Stereotypies;Zoomanagement;Spaceuse

∗Correspondingauthor.

Introduction

In orderto achieve good animal welfare inzoological institutions it is necessary to understandthephysicalandpsychologicalneedsoftheanimals andprovideappropriate management.Studiescarriedoutinthenaturalhabitatofspeciesprovidegoodindicators forthespecies-specificrequirementsthatshouldbesuppliedinzoologicalinstitutions.In manycases,the wild–captivecomparisonisausefultoolasananimal-welfareindicator

(Broom,1983;Veasey,Waran,&Young,1996).

Abnormalbehavioursarenotobservedinthetypicalbehaviourpatternsofwildor free-roaminganimals(Criswell&Galbreath,2005;Meyer-Holzapfel,1968)andtheoccurrence ofsuchbehaviourisconsideredanindicatorofpooranimalwelfareinzoological institu-tions.Broom(1983)suggestedthatitisunacceptableforanyanimaltospendmorethan 10%ofthewakingdaydisplayingabnormalbehaviours.Therearedifferentcategoriesof theabnormalbehaviours,includingabnormalescapereactions,refusaloffood,excessive aggression,stereotypicmotorreactions(i.e.head-toss,pacingor straight-line, figure-of-eight,circularandovalcircuits),self-mutilation,abnormalsexualbehaviour(i.e.substitute sexualobjects),apathy,aggression,oralstereotypes(i.e.biting,coprophagy,regurgitation andreingestion,orlicking),abnormalmother–infantrelationshipsandprolongedinfantile behaviour(Fox,1968).Itisnecessarytoidentifyandclassifyabnormalbehaviourscorrectly because,inmanysituations,somebehaviouralexpressionscanbetheresultofphysical dis-ease(e.g.dentalproblems,arthritisorhormonaldysfunctions).Physicalafflictionscanbe detectedthroughveterinarydiagnosesandaredifferentfromthementalconditions associ-atedwithabnormalbehaviour,whichimplicateacomplexneurobiologicalbasis(Mason&

Latham,2004).Onekindofabnormalbehaviourisstereotypicbehaviour,whichis

some-times observedinzoologicalinstitutions andcharacterizedbymorphologicallyidentical movementsrepeatedregularlywithoutanyapparentfunction(Lawrence&Rushen,1993;

Mason,1991;Mason&Rushen,2006).

Members of theUrsidae familyaremorelikelytoexhibitabnormal behaviours,such aspacingorbegging,inzoologicalinstitutionsbecausetheircomplexneeds,particularly relatedtoseasonalvariationsinactivity(hibernation),feeding(omnivorous)or reproduc-tion (polygamous),crepuscular habits andthe extensive territories in nature (territorial behaviour),aredifficulttoprovideartificially(Vickery&Mason,2003a;Ward&Kynaston,

2003).

Individual variationsin abnormal behaviours have also been observed in the Ursids literature.SixtysixbrownbearsUrsusarctosfrom28zoologicalparksshowedindividual patterns(Montaudouin&LePape,2005),andalsoseeninotherspecies;forexample,Giant pandas Ailuropodamelanoleuca(Lindburg,Swaisgood,Zhang,Narushima,&Xiaoping, 2003), Malayan sun bearsHelarctos malayanus(Cheng, 2003),Asiatic black bearsU. thibetanusandMalayansunbears(Vickery&Mason,2003b),andPolarbearsU.maritimus

(Wechsler, 1991). Moreover,individual patterns inabnormal behaviours can be caused

mainlybysevenfactors:gender,hormonallevels,age,nervous-systemmalfunction,time spentincaptivity,typeofrearingorlifeexperience(seeTable1).

Therearefewstudiesthathavestudiedtheeffectsofseasonvariationonbearabnormal behaviours.So,therearetwopublicationsinPolarbearswhereabnormalbehaviourswere

Table1. SeveninfluentialfactorsinthedevelopmentofabnormalbehavioursincaptiveUrsids.

Factor Definition Reference

Gender Inzoologicalinstitutions,malePolarbears showedmoreabnormalbehavioursduringthe springmatingseasonthanfemales

Ames(1993)

Hormonelevels Thereismoretestosteroneinmalebearsduring thebreedingperiod,whichcancauseahigher prevalenceoftheabnormalbehaviours

Lawrenceand Rushen(1993)

Age Theeffectofcaptivityseemstobemore profoundforayoungbearthanformature animals,intermsoftheexpressionand persistenceofabnormalbehaviours

Ridleyand Baker(1982)

Nervous-system malfunction

Usuallyprovokestheappearanceofan abnormalbehaviour

Ridleyand Baker(1982) Timespentin

captivity

Timehasaninfluenceonabnormalbehaviours, whichcanchangeinformwithage;these behaviourscanalsoloseelementsofthe originalbehaviourpatternandevolvewithtime

Lawrenceand Rushen(1993)

Typeofrearing Hand-rearedanimalsseemtohaveagreater tendencytodevelopabnormalbehavioursthan bearsthathavebeenmotherreared

Marrinerand Drickamer (2005) Lifeexperience Thevarietyofexperiencesthatoccurduringthe

lifetimeofeveryanimal(e.g.isolationorpoor environment)canprovokethemanifestationof abnormalbehaviours

Fernandez (2010)

moreprevalentinspringthaninsummer(Ames,1993;Kolter&Zander,1995).Another publication inAmerican black bears U.americanus determined aseasonal variationin abnormalbehavioursandhisrelationshipwithtwospeciestypicalbehaviourswhichwere mate-seekingbehaviour predominatelyinthe latespring andforagingbehaviourinlate summerandautumn(Carlstead&Seidensticker,1991).Thereisnotanypublicationthat describestherelationshipbetweenabnormalbehaviour seasonalvariationandthe space use.

It is crucialtodetermine the importance of the development andpotentiation of the seasonalvariationsincaptivebrownbearsinordertoimproveanimalwelfareandavoid the development of abnormal behaviours. If there are seasonal variationsin abnormal behaviours possibly theremight be also seasonalvariations inother kindof behaviour (e.g.breeding,feedingorrearing).

Theaimofthisstudywasdescribingdifferentaspectsoftheabnormalbehaviours devel-opedby twobrownbearfemales atBarcelonaZoo: individualdifferencesandseasonal variationsoftheduration,intensity,occurrenceandspaceuse.Thiskindofinformation canbeusefulinordertoimprovecaptivebearmanagementbecausetheseanimalsaremore susceptibletodevelopabnormalbehaviours.Thesebehavioursareoneofthemainconcerns forprofessionalsimplicatedincaptiveanimalwelfare.

Materials

and

Methods

AnimalsandHousingThe twobrownbearfemales studied atBarcelonaZooarrivedfromthe Parquede la Naturalezade Cabárceno(Cantabria,Spain) inNovember2003.Theyoung ♀ wasborn inCabárcenoon1March1994andrearedbyhermother.Theolderfemale’sbirthtype, location, dateof birth andtype of rearing wereunknown because she wasborn before Cabárcenowasopenedin1990.Thehybridstatusofbothfemalesisalsounknown.

AtCabárcenothesetwofemaleswerehousedtogetherwith80otherbrownbearsina semi-freeroamingreserveforanimals.Theenclosurewasanaturalizedmountainousspace belongingtoanold ironmineandhadatotalareaof63ha.Thediet consistedof fruit, vegetablesandmeatprovidedonceadaywhenavehicleenteredtheenclosure.Thespace didnothaveanyindoorareasandnoenrichmentprogrammewasprovided.

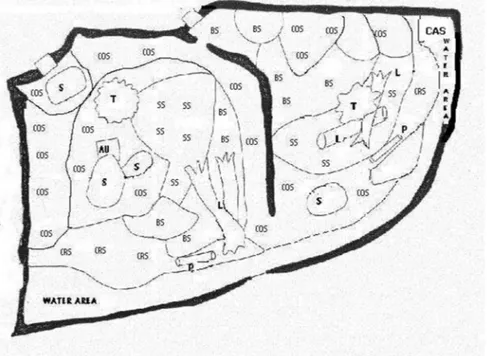

DuringthisstudyatBarcelonaZoo,thetwobearswerehousedtogetherinamoat-style, semi-naturalizedenclosurewithastructureoriginallymadefromcementandatotalarea of 230m2(seeFig.1).Awalldividedtheenclosurewithanopeningtoconnectthetwo parts,eachofwhichhadanaquaticzonefortheanimalstodrinkandbathe.Thefeatures ineachenclosureincludedlivetrees,bushes,severallargestones,largeoverturnedlogsfor climbing,andseveralterracesatdifferentlevelswithanaturalsubstrateofgravel,sandand

Fig.1.Diagramoftheenclosureforbrownbears.AU,honeydispenser;BS,barksubstrate;CAS, waterfall;COS,concretesubstrate;CRS,crushedstonesubstrate;L,logs;P,PVCpipe;S,stones;SS, sandsubstrate;T,tree.

bark.Theindoorareaswereoff-viewcementcageswithadrinkingtroughandbath(total surfaceareaof10m2each)(Soriano,Ensenyat,Serrat,&Maté,2006).

DailyManagement

Themanagementprotocolallowsthebearstogointotheiroutdoorenclosuresaccording tothehoursofdaylight(between9:00a.m.and4:00p.m.inspring;9:00a.m.to8:00p.m. insummer;9:00a.m.to7:00p.m.inautumn).Thedietofferedwasseasonallyunvaried andconsistedof8kgoffruitandvegetables,4kgofmeat(amixtureofhorse,chickenand veal),2kgofdogchowand1kgofbreadonceadayforeachbear,providedintheindoor areasintheevening.Theold♀andtheyoung♀sleptseparatelyintheirrespectiveindoor enclosures.

Duringthestudyphase,theanimalstookpartinatwice-dailyenrichmentsession.Each bearreceivedthesameenrichmentdevicepersession.Duringthefirstsession,thekeeperput theenrichmentdeviceintheenclosurebeforetheanimalswereletintothespace,ataround 9:00a.m.Thesecondenrichmentdevicewaspreparedbythekeeperaround1:00p.m.and wasthrowninto theenclosure fromthe visitorviewingarea.The schedulefor different enrichmentdevicesforbothsessionsconsistedof31devices,twoofwhichwereusedeach dayofthemonth,followingthesamepatternduringallthemonthsofstudy.Inaddition, thereweredifferentkindsofenrichmentdevices;forexample,(1)feeding,whichprovided elementsthatcontainedfood,suchaslivefish[thefeedingoflivevertebratesisillegalin somecountries],vegetablesinsideasackorfruitinsidetrafficcones;(2)sensory,elements thatmaximizeolfactorycapabilities,suchasdifferentspicesorthefaecesofherbivores; and(3)occupational,itemsthatmaximizethephysicalandmanipulativecapabilities,such asballs,tyresortrafficcones(Soriano,2013).

These animals did not have any training programme that would facilitate veterinary practicesorbodymaintenance,suchasfootordentalcare.

AbnormalBehaviours

InFebruary2004,veterinaryexaminationofthesetwofemaleswascarriedouttodiscount physicaldiseaseasapotentialfactorinfluencingbehaviour.Thediagnosesestimatedthat theundesirablebehavioursobservedinthesebearswereconsideredabnormal.

Eachbeardemonstratedadifferent typeof abnormalbehaviour,on theonehand the old♀showedanoralabnormalbehaviourandontheotherhand,theyoung♀developeda locomotorstereotypy.Theold♀displayedepisodesofbitingatreetrunkthatwaspartof theenclosurefurniture.Thedescriptionofthisbehaviourwastheanimal,inafour-legged position,partlyintroduceditsmouthoverthe tree,andrepeatedlyopenedandclosedits mouth,tighteningits jawagainstthebaseofthe trunk.Thisbehaviour wasclassifiedas a‘state’, because it hadameaningful durationandit could betimed withastopwatch

(Fig.2A)(Lehner,1996).Theyoung♀demonstratedabehaviourthatwasrepetitiveand

ofshortduration,whichconsistedofabruptlyliftingtheheadupwardand/ortothesidein aswinging,oftencirculararc,ordippingtheheadtothegroundwithoutbreakingstride whilewalking.ThisactionhasbeendescribedinGiantpandasandwasnamed‘head-toss’

Fig.2.Diagramofabnormalbehavioursforbrownbears:A.Old♀;B.Young♀.

(Lindburgetal.,2003).Thisbehaviourwasclassifiedasan‘event’,definedasamomentary

behaviour(onlylasting5s)(Fig.2B)(Lehner,1996). DataCollection

ThestudyperiodwasfromMarchtoDecember2004.Theobservationsessionslasted one-hourand63hoursofobservationswererecordedusingamulti-focaland continuous-samplingmethod(Martin&Bateson,2007).Thestudiedvariablesincluded:

1. Seasonalperiods:21hoursofobservationwereconductedwithineachseason:spring (30 March–7 June 2004), summer (28 June–16 September 2004) and autumn (22 September–20December2004).

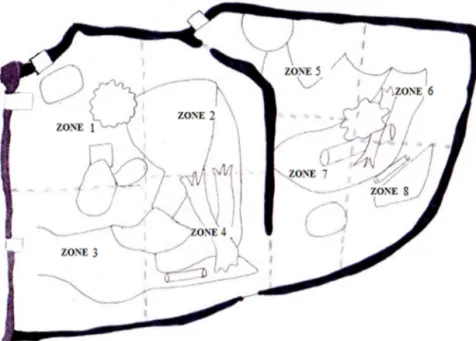

2. Abnormalbehaviours:fivedifferentaspectsofthisvariablewerestudiedineachsession: (1)percentageoftimeinvestedonabnormalbehaviour;(2)duration(sec),definedasthe amountoftimethebearengagedintheabnormalbehaviourandwasonlymeasuredfor theoldfemale’sepisodes;(3)intensity(sec),definedasthetimethatelapsedbetweentwo consecutiveabnormalstatesorevents;(4)occurrence,definedasthenumberofabnormal statesoreventsobservedduringeachsession;and(5)spaceusefrequency,definedas animalenclosurelocalizationmeanwhilethebearshowedtheabnormalbehaviours.The enclosurewasdividedintoeightsimilarlysizedzonesfromZone1toZone8(Fig.3). DataAnalysis

AlldataanalyseswerecalculatedusingtheStatisticalPackagefortheSocialSciences (SPSSInc.,Chicago,IL60606,USA)Version21.0forWindows.Normalitywasassessed usingKolmogorov–Smirnovtest.ArejectioncriterionofP<0.05wasappliedtoalltests. Therelationshipbetweenseasonalperiodsandtheduration,intensityandoccurrencewere obtained through the Kruskal–Wallis test (Lehner, 1996). Meanwhile, the relationship

Fig.3.Diagramoftheenclosureforbrownbearsshowingthedivisionoftheareasforthestudy ofspaceuse.

betweentheseasonalperiodsandtheuseofspacewereobtainedthroughchi-squaretest. Theadjustedresidualstatisticusedhadanabsolutevalueof1.96foranormaldistribution

(Haberman,1978).

Results

Forbothfemalesthe %oftimeinvestedonabnormalbehaviour washigherinspring followedbysummerandautumn(old♀;autumn:8.10%;spring:27.74%;summer:9.34%; young♀;autumn:7.50%;spring:11.75%;summer:9.12%).

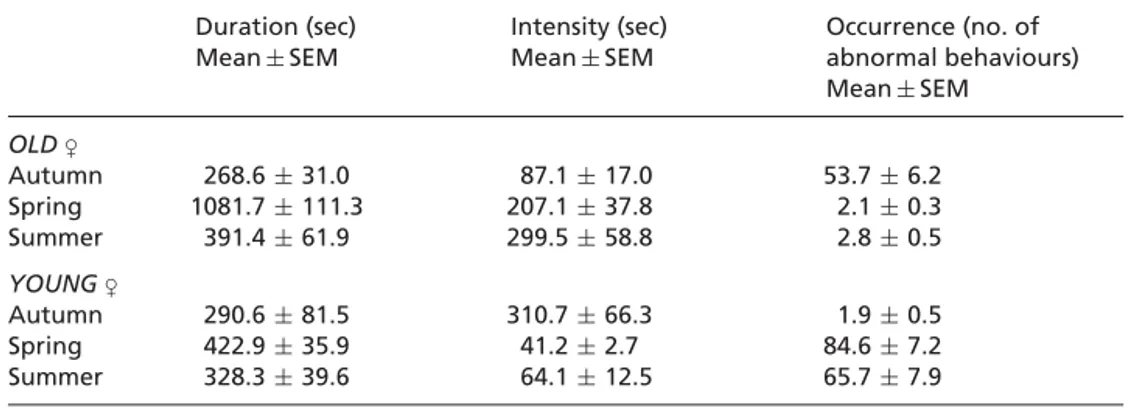

Themeanandstandarddeviationoftheduration,intensityandoccurrenceofabnormal behaviourspersessionforthetwobrownbearfemalesareshowinTable2.Theabnormal behaviour duration was statistically significant higher inspring than insummer andin autumnforbothfemales.The intensityof abnormalbehaviour onlyshowed statistically significant difference for the young ♀. In thiscase, the intensity showed a statistically significanthighervalueduringautumnthaninsummerandinthespring.Theoccurrence ofabnormalbehavioursshowedstatisticallysignificantvaluesforbothfemales.Theold♀

showedahighervalueinautumnthaninsummerandinthespring.However,theyoung♀

showedahighervalueinspringthaninsummerandautumn(Table3).

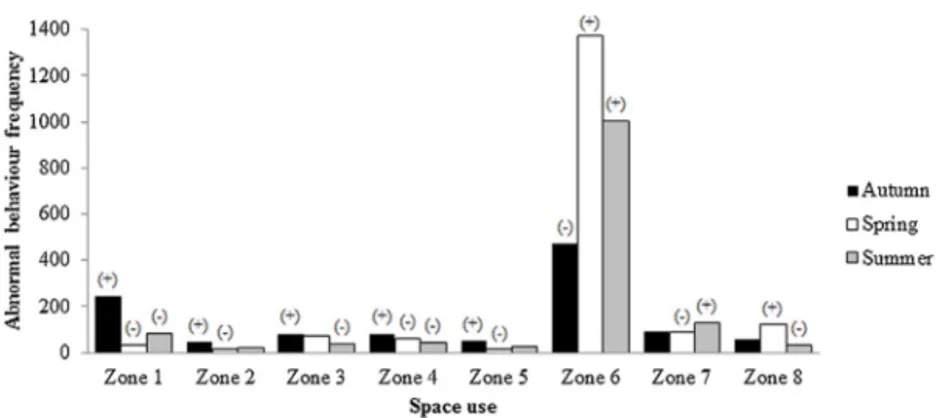

Inrelationtospaceuse,theold♀alwaysdevelopedtheabnormalbehaviourintheZone 4whichfrequencywas54boutsinautumn,47boutsinspringand49boutsinsummer.

Table 2. Mean±standarderrorofmean(SEM)fortheduration,intensityandoccurrenceof abnormalbehavioursforeachseasonalperiodandsessionintwoBrownbearUrsusarctosfemales:

nold♀=137;nyoung♀=4283(wheren=numberofobservedepisodesintheold♀andeventsin theyoung♀). Duration(sec) Mean±SEM Intensity(sec) Mean±SEM Occurrence(no.of abnormalbehaviours) Mean±SEM OLD♀ Autumn 268.6±31.0 87.1±17.0 53.7±6.2 Spring 1081.7±111.3 207.1±37.8 2.1±0.3 Summer 391.4±61.9 299.5±58.8 2.8±0.5 YOUNG♀ Autumn 290.6±81.5 310.7±66.3 1.9±0.5 Spring 422.9±35.9 41.2±2.7 84.6±7.2 Summer 328.3±39.6 64.1±12.5 65.7±7.9

Table3. Kruskal–Wallisvaluesthatshowtheeffectofseasonalperiodontheduration,intensity andoccurrencefortwoBrownbears.

Duration(sec) Intensity(sec) Occurrence(no.of abnormalbehaviours)

H d.f. P H d.f. P H d.f. P

Old♀ 54.51 2 0.00** 2.79 2 0.24 15.70 2 0.00**

Young♀ 733.02 2 0.00** 810.59 2 0.00** 733.02 2 0.00**

**StatisticallysignificantdifferencesP<0.05;H,Kruskal–Wallistest;d.f.,degreesoffreedom.

Theyoung♀useofspaceshowedstatisticallysignificantdifferencesduringtheseasonal periods(X2=671.88;df=14;P=0.00**).Thisfemaleusemorefrequentlyzone6thanthe others. In autumn,thisfemaleshowed abnormalbehaviour withstatisticallydifferences more frequently inZones1, 2, 3, 4 and 5.In spring,the young ♀ developed abnormal behaviourwithstatisticallydifferencesmorefrequentlyinZones6and8.Insummer,this femaleshowedabnormalbehaviourwithstatisticallydifferencesmorefrequentlyinZones 6and7(Fig.4).

Discussion

Theabnormalbehavioursinthefemalesof thisstudyshowedindividualpatterns.The young ♀ showed a locomotor stereotypy also observedin otherstudies inbrown bears

(Spendrup &Larsson, 1997), Polar bears(Ames, 1993; Hare, 1995; Fernandez, 2010)

Fig.4.Frequencyofthespaceuseduringabnormalbehaviourforeachseasonalperiodinthe youngbrownbear.

behaviourswerealsoobservedinGiantPandas(Lindburgetal.,2003)andbrownbears

(Montaudouin&LePape,2005;Soriano,Vinyoles,&Maté,2016).

Onthe onehandandtakinginto account theunacceptable abnormalbehaviour value higher than10% described byBroom(1983),the unacceptable welfarevaluesfor both females of thisstudy would be observed inspring (old ♀: 27.74%; young ♀: 11.75%). However,thesevalueswouldbeacceptableinautumnandsummerforbothfemales.Onthe otherhand,MontaudouinandLePape(2005)encodedtheamountofstereotypyin:(1)no stereotypy;(2)low:lessthan21%oftime.Inthiscase,itwouldbeincludedthepercentages oftimeinvestedinabnormalbehaviourforbothfemalesinautumn(old♀:8.10%;young

♀:7.50%)andsummer(old♀:9.34%;young♀:9.12%)andonlythepercentageofyoung

♀inspring(11.75%);(3)medium:21%to45%oftime.Itwasonlyobservedfortheold

♀duringspring(27.74%);and4)highmorethan45%oftime.Itwasnotobservedinthis study.

Thestudy ofAmes(1993)inPolarbearsalsodescribedindividualpatterns of abnor-malbehavioursandalsoseasonalvariationsinthefourperiods–spring,summer,autumn andwinter–.Thisstudyincludedfivepolarbearmalesandeightpolarbearfemaleswhich showedsixdifferentkindsoflocomotorstereotypyonlandandinwater.Therewasa sub-stantialvariationintheamountofstereotypicbehaviourforthefemales,levelsrangedfrom 0%to59.9%andforthemalesrangedfrom0%to45%.Inthiscasethelowestpercentageof stereotypicbehaviourwaslowerthanbrownbearsofthisstudyandhighestlevelishigher, too.The durationof thesebehaviours rangedfrom 8secto50secand itwere different thanobservedinbrownbearsofthisstudythatrangedfrom5sec–fortheyoungfemale’s events–to1743sec –for the oldfemale’sbouts–.OnePolarbearmale andonefemale showedthelowestlevelofabnormalbehaviourinautumnandthehighestlevelinspring coincidingwiththeresultsofthisstudy.Moreover,onemaleandthreefemalesshowedthe lowestlevelofabnormal behaviourinautumnandthreemalesandtwofemales showed thehighestlevel ofabnormalbehaviourinspringlikethebrownbearsofthisstudy.The otherelevenPolarbearsshowedothervariationsoflowestandhighestlevelofstereotyped behaviour (winter-spring;spring-autumn; winter-summer;autumn-winter;spring-winter;

summer-winter;winter-autumn;summer-springand;autumn-summer,respectively).Polar bears may be are more susceptible to develop stereotypic behaviours than the rest of the bears because is more difficult to reproduce in captivity the extreme seasonal conditions.

CarlsteadandSeidensticker(1991)studiedstereotypicpacinginanAmericanblackbear

andobservedtwopeaksrelatedtomate-seekingbehaviourpredominatinginthelatespring andforagingbehaviourinthelatesummerandfall.Theseresultsarevery similartothe observedinthetwobrownbearsofthisstudy.Insummer,thebrownbearsofthisstudymay bearelesssusceptibletodevelopabnormalbehavioursbecausetheweatherconditionsare thesamethaninwildconditionsandthereisnotmatingorhibernationfeedingnecessities. In spite of the winter period was not observed in this study of brown bears, it is known that the winter sleeping isa species-typicalbehaviour. Therefore,more specific studiesare necessary todeterminethe role of hibernationin thewelfare of thesebears in zoological institutions. The hibernation period in bears is reliant on several differ-entfactors,including:(1)externalfactors,suchastemperatureandfood availability;(2) internalfactors,suchas hormonalchanges;and(3)acombinationof factors(1)and(2)

(Brown,2009;Möstl&Palme,2002;Stirling,1993;Ward&Kynaston,2003).The

zoo-logical institutions that house native species do not need to invest in large amount of money inair-conditionedor heatedenclosures becausethe localweather conditionsare the same. For example, at Ueno ZoologicalGardens, Japan, there is a Japanese black bear U. thibetanus japonicus enclosure that was designed to include an indoor enclo-surefor hibernation,inordertoencourage thisspecies-typicalbehaviour. Thisspecially designed denmakesit possibletostudy theanimals during hibernationandallows vis-itors toobserve the bearsevenduringthe winter-sleeping period(Itoh, Ide,Kojima, &

Terada,2010).Therearealsobearsinzoologicalinstitutionsthatcannothibernatebecause

theyarefarawayfromtheirnaturalenvironment,suchasthebearsatBarcelonaZoo.In thiscase,the welfareimplicationsof theinabilitytohibernateareunknown.Inorderto reproducethisparticularspecies-typicalbehaviourinaninstitution,itwouldbenecessary toadapt thehusbandry andmanagementprotocols, andthedesignof theenclosure and dens.

In relationtothespaceuse,theyoung ♀mightusemorefrequently thezone6 ofthe enclosurebecauseitistheplacemostplaneandmoreawayfromthevisitor’sarea.

The expressionof abnormal behaviours could be theresult of the conditions in zoo-logicalinstitutionsnotreproducingaccuratelytheconditionsinnature,whichpermitthe crepuscularbrownbearstoexperiencetwoseasonalpeaksinspecies-specificbehaviours (i.e.reproductioninspringandfoodstoreinautumn).Inordertoachievethesedesirable variationsandmeetindividualneeds,therearefactorsthatshouldbeconsideredandshould beincludedinthedailybear-managementprotocols(Soriano,2013).

1. Dietcomposition.Someformofseasonalvariationshouldbeincludedtoprovisionof diet, makingitmoresimilartothevariationsthat wouldbe experiencedinthewild. So,BrookfieldZoomanagersimplementedseasonaldietsforbrownbearssuccessfully becausethebearslostweightandaremoreactivewithlessaggressionandstereotypic behaviours(Watts,2009).Moreover,somestudiesthatappliedfeedingenvironmental

enrichmentinbrownbearsalsoreducedstereotypicbehaviours(Grandia,VanDijk,&

Koene,2001;Larsson&Tove,1995;Morimura&Ueno,1999).

2. Enrichmentprogrammes.Introduce seasonalvariationsintothe designandprovision ofvariousenrichmenttechniques;forexample,designanewenrichmentdevicewith salmoninsummerorintroducedriedfruitsinautumn(Hare,1995;Soriano,Vinyoles,

&Maté,2013).

3. Facilitydesign.Includeclimate-controlledfacilitiesanddenswithgrasses,moss,leaves, coniferneedles,andtreebranches(Brown,2009).Thereisalsoacrucialrelationship betweenthesizeandlayoutoftheenclosureandtheexpressionofabnormalbehaviours. Whenthefacilitiesprovidedarelargerandmorenatural,littleabnormalbehaviourare observedinbearsinzoological institutions (Seidensticker&Doherty,1996;Soriano

etal.,2006;Spendrup&Larsson,1997).

4. Socialconditions. Studiesshouldbecarried outtodeterminewhetherthe welfareof typically solitaryindividuals (as bears tendtobe innature) is worsewhen they are coexistingwithconspecificsthanwhentheyarehousedalone.Thisfactorcanbestudied throughbehavioural(i.e.expressionofabnormalbehaviours,theuseofspace,proximity) or/andphysiological(i.e.hormonalstudies) indicators(Kleiman,Thompson,&Baer, 2010).Itisimportanttotakeseasonintoaccountwheninstitutionsareparticipatingin breedingconservationprogrammes(Fa,Funk,&O’Connell,2011).

5. Effectofvisitors.Inzoologicalinstitutionsvisitorshaveaneffectontheexpressionof abnormalbehaviour.Thiseffecthasbeenclassifiedas:(1) positive,whenthevisitors decreaseabnormalbehavioursgenerally,andcanbeconsideredpartoftheenrichment programme(Claxton,2011;Robson,2004);(2)neutral,whenvisitorshavenoparticular effectonthe prevalenceof abnormal behaviours(O’Donovan,Hindle, McKeown,&

O’Donovan,1993;Sorianoetal.,2013);and3)negative,whenthevisitorsincreasethe

prevalenceofabnormalbehavioursordecreasethewelfareoftheanimals(Cunningham,

2005;Owen,2004;Sorianoetal.,2013).

6. Veterinarycare.Thehealthof allanimals inzoological institutionsshouldbe ahigh priorityasill healthor diseasemayaffectthe manifestationofabnormal behaviours. Protocols shouldincluding providingvaccines, ensuring anyinjuries or illnessesare cured, andmedication should be administered to avoidor treat parasite infestations

(Irwin,Stoner,&Cobaugh,2013).

7. Trainingprogrammes.Wherepossible,inordertofacilitateveterinarypractices,suchas administeringvaccinesorcollectingbiologicalsamples(e.g.blood,hair,urine,faeces), andbody maintenance(e.g.brushing hair or skin,filingnails or maintaining teeth), animals in zoological institutions should betrained topresent variousparts of their bodiesforveterinaryinspection(Ramirez,1999).

8. Transportation.Movinganimalsbetweeninstitutionsisalwaysstressful.Itisessential thatthewelfareoftheindividualshouldnotdiminisheitherduringoraftertransportation. Certainindividualfactorsshouldalsobetakenintoaccountbeforeanimalmovements; forexample,age,timespentincaptivity,healthandthemanagementguidelinesforthe species(Rees,2011).

Allthesefactorsinfluencethedevelopmentandmanifestationofabnormalbehaviours. Studyingeachaspectinmoredetailwouldbenecessaryifwearetoidentifytheoptimal

conditionsforthemaintenanceofbearsinthemostartificialenvironments(Swaisgood&

Shepherdson, 2005).Theultimate aimof thesekinds of studiesisthe reintroductionto

naturalhabitatsofbearsfromzoologicalinstitutions,asproposedbyVickeryandMason

(2003b),especiallybecausethesespeciesareatseriousthreatofextinctionintheirhome

territories.

Acknowledgements

WewishtothankSandraBalsandJuaniMelerofortheircollaborationonthisstudy.In addition,wewouldliketothankourfriendsEstherFernandezandMarcEscobarfortheir helpwritingthisarticle.WealsoappreciatetheEnglishrevisionbySudanshuKarandikar, ConchaSantolayaandSusannaFlavià.

References

Ames, A. (1993).The behaviourof captive polar bears. UFAW Animal Welfare Research ReportNo.5. Wheathampstead,Herts:UniversitiesFederationforAnimalWelfare.

Broom,D.M.(1983).Stereotypiesasanimalwelfareindicators.CurrentTopicsinVeterinaryMedicineandAnimal Science,23,81–87.

Brown,G.(2009).Thebearalmanac:Acomprehensiveguidetothebearsoftheworld.Guilford,CT:TheGlobe PequotPress.

Carlstead,K.,&Seidensticker,J.(1991).SeasonalvariationinstereotypicpacinginanAmericanblackbearUrsus americanus.BehaviouralProcesses,25,155–161.

Cheng,J.S.C.(2003).TheeffectsoffeedingpatternchangeonMalayansunbears.InV.J.Hare,K.E.Worley, &B.Hammond(Eds.),Proceedingsofthefifthconferenceonenvironmentalenrichment(pp.365–368).San Diego,CA:TheShapeofEnrichment.

Claxton,A.M.(2011).Thepotentialofthehuman–animalrelationshipasanenvironmentalenrichmentforthe welfareofzoo-housedanimals.AppliedAnimalBehaviourScience,133,1–10.

Criswell,A.R.,&Galbreath,G.J.(2005).Behavioralpersistenceincaptivebears:Acritique.Ursus,16,268–273. Cunningham,N.(2005).VisitorimpactonthecaptivefelidbehaviouratEdinburghZoo.InA.Nicklin(Ed.), Proceedingsoftheseventhannualsymposiumonzooresearch(pp.159–164).London:British&Irish Associ-ationofZoos&Aquariums.

Fa,J.E.,Funk,S.M.,&O’Connell,D.(2011).Zooconservationandbiology.Cambridge.

Fernandez,E.(2010).Stereotypiesandforaging:Appetitivesearchbehaviorsandstereotypiesincaptiveanimals. Saarbrücken.

Fox,M.W.(1968).Abnormalbehaviorinanimals.Philadelphia.

Grandia,P.A.,VanDijk,J.J.,&Koene,P.(2001).Stimulatingnaturalbehaviorincaptivebears.Ursus,12, 199–202.

Haberman,S.J.(1978)..Analysisofqualitativedata(Vol.1)NewYork.

Hare,V.J.(1995).BehaviormodificationofcaptiveAlaskanbrownbears(Ursusarctosgyas)usingautomatedfood dispensers.InB.Holst(Ed.),Proceedingsofthesecondinternationalconferenceonenvironmentalenrichment (pp.39–61).Copenhagen:CopenhagenZoo.

Irwin,M.D.,Stoner,J.B.,&Cobaugh,A.M.(2013).Zookeeping:Anintroductorytoscienceandtechnology. Chicago.

Itoh,K.,Ide,K.,Kojima,Y.,&Terada,M.(2010).HibernationexhibitforJapaneseblackbearUrsusthibetanus

japonicusatUenoZoologicalGardens.InternationalZooYearbook,44,55–64.

Kleiman,D.G.,Thompson,K.V.,&Baer,C.K.(2010).Wildmammalsincaptivity:Principlesandtechniques ofzoomanagement(2nded.).Chicago.

Kolter,L.,&Zander,R.(1995).Potentialandlimitationsofenvironmentalenrichmentinmanagingbehavioural problemsofpolarbears.InB.Holst(Ed.),Proceedingsofthesecondinternationalconferenceenvironmental enrichment(pp.131–141).Frederiksberg:CopenhagenZoo.

Larsson,H.O.,&Tove,S.(1995).Dailyactivityandeffectsoffeedingenrichedenvironmentinbrownbear(Ursus

arctos).InB.Holst(Ed.),Proceedingsofthesecondinternationalconferenceonenvironmentalenrichment(p. 289).Frederiksberg:CopenhagenZoo.

Lawrence,A.B.,&Rushen,J.(1993).Stereotypicanimalbehaviour:Fundamentalsandapplicationstowelfare. Wallingford:CABInternational.

Lehner,P.N.(1996).Handbookofethologicalmethods(2nded.).Cambridge.

Lindburg,D.G.,Swaisgood,R.R.,Zhang,J.,Narushima,E.,&Xiaoping,Z.(2003).Stereotypedbehaviorinthe giantpanda.InV.J.Hare,K.E.Worley,&B.Hammond(Eds.),Proceedingsofthefifthinternationalconference onenvironmentalenrichment(pp.189–193).SanDiego,CA:TheShapeofEnrichment.

Marriner,L.M.,&Drickamer,L.C.(2005).Factorsinfluencingstereotypedbehaviorofprimatesinazoo.Zoo Biology,13,267–275.

Martin,P.,&Bateson,P.(2007).Measuringbehaviour:Anintroductoryguide(3rded.).Cambridge. Mason,G.J.(1991).Stereotypies:Acriticalreview.AnimalBehaviour,41,1015–1037.

Mason,G.J.,&Latham,N.R.(2004).Can’tstop,won’tstop:Isstereotypyareliableanimalwelfareindicator? AnimalWelfare,13,57–69.

Mason,G.J.,&Rushen,J.(2006).Stereotypicanimalbehaviour:Fundamentalsandapplicationstowelfare. CABI:Oxford.

Meyer-Holzapfel,M.(1968).Abnormalbehaviorinzooanimals.InM.W.Fox(Ed.),Abnormalbehaviourin animals(pp.477–503).Toronto.

Montaudouin, S.,&LePape, G.(2005).Comparisonbetween 28zoologicalparks: Stereotypicand social behavioursofcaptivebrownbears(Ursusarctos).AppliedAnimalBehaviourScience,92,129–141. Morimura,N.,&Ueno,Y.(1999).InfluencesonthefeedingbehaviorofthreemammalsintheMaruyamaZoo:

Bears,elephants,andchimpanzees.JournalofAppliedAnimalWelfareScience,2,169–186.

Möstl,E.,&Palme,R.(2002).Hormonesasindicatorsofstress.DomesticAnimalEndocrinology,23,67–74. O’Donovan,D.,Hindle,J.E.,McKeown,S.,&O’Donovan,S.(1993).Effectofvisitorsonthebehaviouroffemale

cheetahsAcinonyxjubatusandcubs.InternationalZooYearbook,32,238–244.

Owen,C.(2004).DovisitorsaffecttheAsianshort-clawedotterAonyxcinereainacaptiveenvironment?In C.Macdonald(Ed.),Proceedingsofthesixthannualsymposiumonzooresearch,8thand9thJuly2004(pp. 202–211).London:FederationofZoologicalGardensofGreatBritainandIreland.

Ramirez,K.(1999).Animaltraining:Successfulanimalmanagementthroughpositivereinforcement.Chicago, IL:SheddAquarium.

Rees,P.A.(2011).Anintroductiontozoobiologyandmanagement.Oxford.

Ridley,R.M.,&Baker,H.F.(1982).Stereotypyinmonkeysandhumans.PsychologicalMedicine,12,61–72. Robson,C.(2004).DovisitorsandweatheraffectcaptiveAsianelephant(Elephasmaximus)behaviour?InC.

Macdonald(Ed.),Proceedingsofthesixthannualsymposiumonzooresearch,8thand9thJuly2004(p.296). London:FederationofZoologicalGardensofGreatBritainandIreland.

Seidensticker,J.,&Doherthy,J.G.(1996).InD.Kleiman,M.Allen,K.Thompson,&S.Lumpkin(Eds.), Integratinganimalbehaviorandexhibitdesign(pp.180–190).Chicago.

Soriano,A.I.(2013).Wildideas:Atlasfotográficosobreelenriquecimientoambiental.Almería:EditorialCírculo Rojo.

Soriano,A.I.,Vinyoles,D.,&Maté,C.(2013).Theinfluenceofvisitorsonbehaviorandontheuseofspacein twospeciesofUrsids:Amanagementquestion?InternationalZooNews,60,341–356.

Soriano,A.I.,Vinyoles,D.,&Maté,C.(2016).Long-termmacroevaluationofenvironmentalenrichmentinthree brownbears(Ursusarctos)atBarcelonaZoo.JournalofAppliedAnimalWelfareScience,19,49–61. Soriano,A.I.,Ensenyat,C.,Serrat,S.,&Maté,C.(2006).Introducingasemi-naturalisticexhibitasstructural

enrichmentfortwobrownbears(Ursusarctos).Doesthisensuretheircaptivewell-being?JournalofApplied AnimalWelfareScience,9,299–314.

Spendrup,S.,&Larsson,H.O.(1997).AcomparativestudyofbrownbearUrsusarctosinfivedifferentenclosure sizesandtypes.InV.J.Hare,&K.E.Worley(Eds.),Proceedingsofthethirdinternationalconferenceon environmentalenrichment(pp.391–398).SanDiego,CA:ShapeofEnrichment.

Stirling,I.(1993).Bears:Acompleteguidetoeveryspecies.London.

Swaisgood,R.R.,&Shepherdson,D.J.(2005).Scientificapproachestoenrichmentandstereotypiesinzoo animals:What’sbeendoneandwhereshouldwegonext?ZooBiology,24,499–518.

Veasey,J.S.,Waran,N.K.,&Young,R.J.(1996).Oncomparingthebehaviorofzoohousedanimalswithwild conspecificsasawelfareindicator.AnimalWelfare,5,13–24.

Vickery,S.,&Mason,G.(2003a).Stereotypyandperseverativerespondingincagedbears:Furtherdataand analyses.AppliedAnimalBehaviourScience,91,247–260.

Vickery,S.,&Mason,G.(2003b).Behavioralpersistenceincaptivebears:Implicationsforreintroduction.Ursus, 14,35–43.

Ward,P.,&Kynaston,S.(2003).Bearsoftheworld.NewYork,NY:FactsonFile,Inc.

Watts,J.(2009).CaseStudy:Seasonaldietsformbrownbears(Ursusarctos)atBrookfieldZoo:Successful implementationledtoreduceweightandimprovedbehaviour.InA.Ward,K.Treiber,D.Schmidt,A.Coslik, &M.Maslanka(Eds.),Proceedingoftheeighthconferenceonzooandwildlifenutrition.Tulsa,OK:AZA NutritionAdvisoryGroup.