Supervisor:

Brun Alessandro

Master Thesis by:

Anaya Muñozcano Carlos

834359

Arroyo Crivelli Ludwing

840944

Academic Year

2016/2017

Business Model Development

a Mobile Application Case - TryMi

School of Industrial and Information Engineering

Master of Science in Management Engineering

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

“In the first place, we would like to thank to Politecnico di Milano for making possible this Master of Science experience, and especially express our deepest gratitude to professor Alessandro Brun for following our thesis project step by step and supported us with feedback that helped us to keep improving the outcomes of our work during all the process. We would also like to thank Guillermo for the support given thought his design skills, and to all our friends and relatives for all the feedback given in the very first stages of the idea generation, that helped us to state the basic foundations on which all our project has been supported”.

P ag .

I

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Acknowledgements ... 0 Table of Contents ... I Table of Figures ... III Table of Tables ... IV Table of Graphs ... V 1 Abstract ... 12 Scope and Objectives ... 2

3 Methodology ... 3

4 Introduction ... 4

5 Literature Review ... 6

5.1 Business Models ... 6

5.1.1 Business Models and technology ... 11

5.1.2 The Business Model Canvas ... 13

5.1.3 The Lean Startup ... 14

5.2 Related Topics ... 24

5.2.1 The collaborative consumption economy ... 24

5.2.2 Global cities ... 28

5.2.3 Mobile application insights ... 29

6 Suitability of the Methodologies ... 33

6.1 The Story of TryMi (business conception) ... 33

6.2 Evaluation with the Business Model Canvas Methodology ... 33

6.2.1 The environment and External analysis ... 33

6.2.2 External analysis ... 39

6.2.3 The Traditional Strategic approach ... 41

6.2.4 Internal analysis ... 42

6.2.5 Market segmentation ... 43

6.2.6 Targeting ... 44

6.2.7 Positioning ... 45

6.2.8 The Marketing Mix ... 47

6.2.9 The action plan ... 47

6.3 Evaluation with the Lean Startup Methodology ... 50

7 Comparison and selection of the BM methodologies ... 54

7.1 The comparison between the traditional approach vs the lean startup methodology... 54

P

ag

.

II

7.2 business model fusion proposition ... 55

8 Initial requirements for development ... 66

8.1 How does the app will work? ... 66

8.1.1 Registration process ... 66

8.1.2 Types of users ... 67

8.1.3 Hiring the service ... 67

8.1.4 The experience ... 68

8.1.5 Rating ... 68

9 Steps ahead and further considerations ... 69

9.1 Legal... 69 9.2 Safety ... 69 9.3 Technology ... 70 9.4 Financing ... 70 9.5 Partnerships ... 71 10 Conclusions ... 72 11 References ... 74 12 Appendixes ... 77 12.1 TryMi Survey ... 77

P

ag

.

III

TABLE OF FIGURES

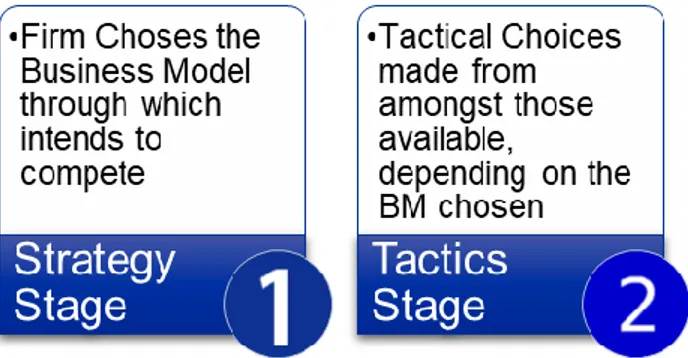

Figure 1 Generic two-stage competitive process framework. (Source: Cassadesus et al.,

2010, Adapted) ... 7

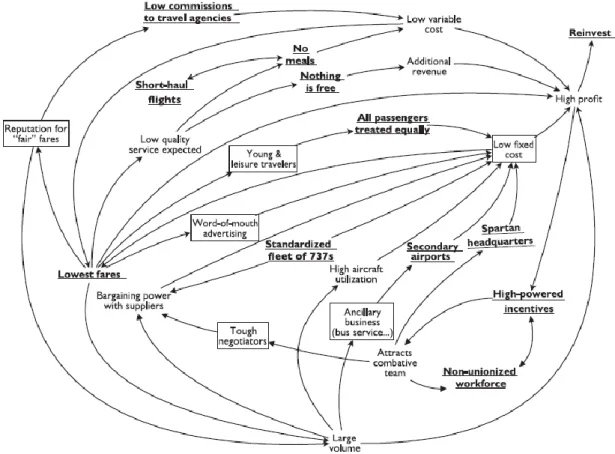

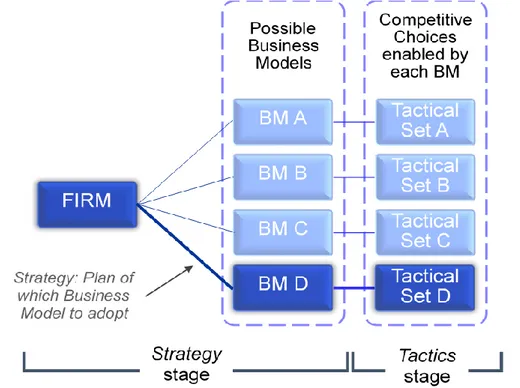

Figure 2 Ryanair’s’ business model representation. (Source: Cassadesus et al., 2010) 9 Figure 3 Strategy, business model, and tactics. (Source: Cassadesus et al., 2010, Adapted) ... 10

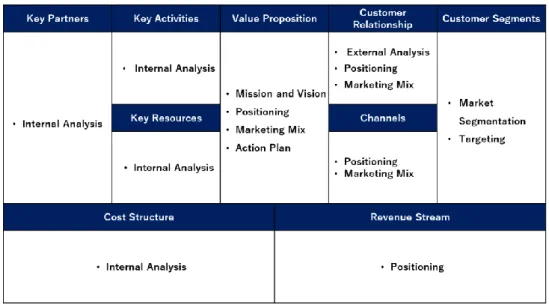

Figure 4 Business Model Canvas and Strategic Planning relationship (Source: Borja et al., 2015. Adapted) ... 14

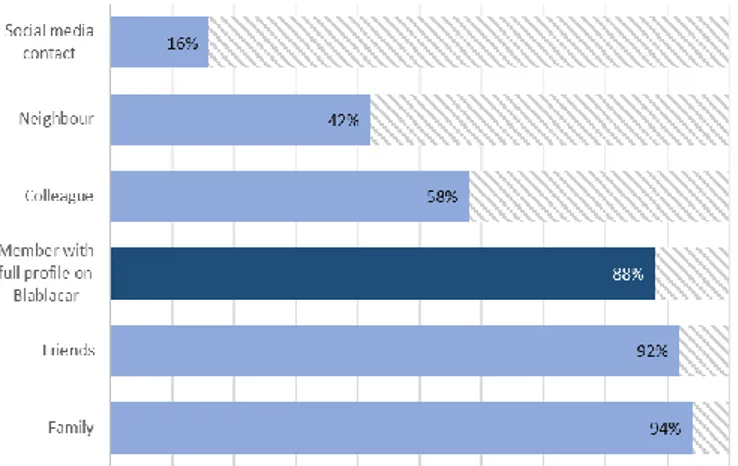

Figure 5 Level of trust in... (Source: Blablacar and NYU Stern., 2016. Adapted) ... 39

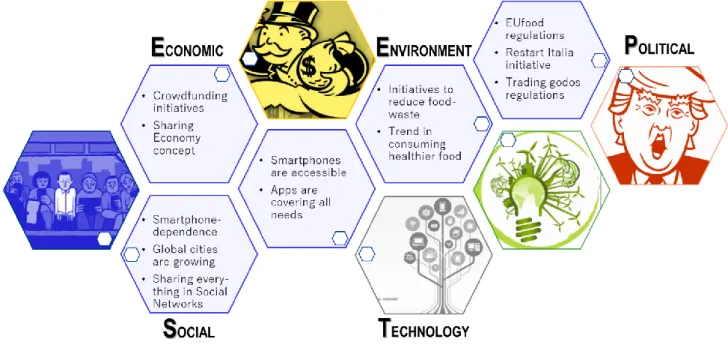

Figure 6 PEEST Analysis for the project (Source: Authors' elaboration) ... 40

Figure 7 Porter's five forces analysis for the project (Source: Authors' elaboration) .... 41

Figure 8 SWOT Analysis for the App. (Source: Authors' elaboration) ... 43

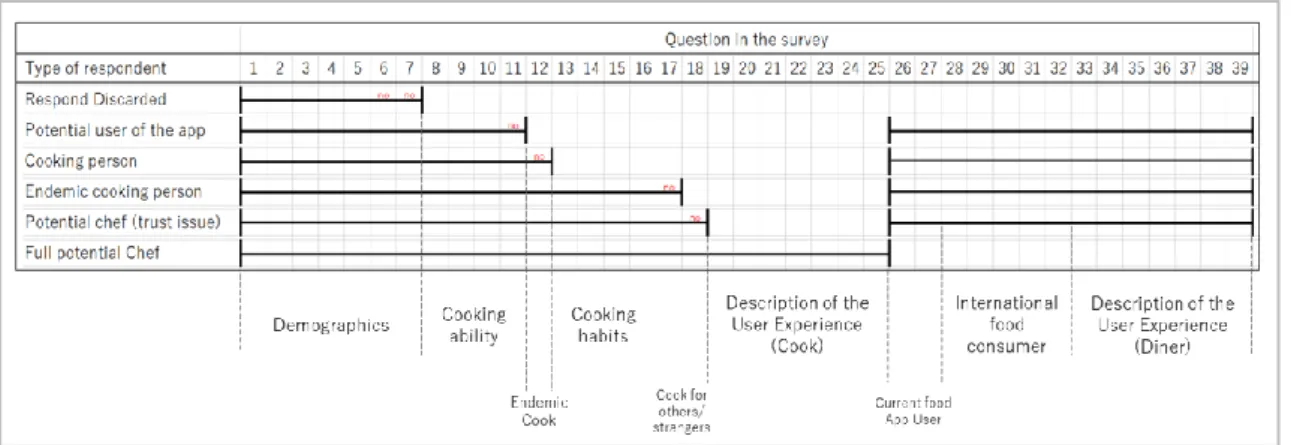

Figure 9 Path of the respondents and question classification from the survey. (Source: Authors' elaboration) ... 45

Figure 10 Logo proposals (Source: Created by Guillermo Flores) ... 46

Figure 11 Business Model Canvas of TryMi. (Source: Authors' elaboration) ... 49

Figure 12 The Build-Measure-Learn cycle. (Source: Eric Ries, 2011. Adapted) ... 50

Figure 13 First hypothesis to obtain validated learning. (Source: Authors’ elaboration) ... 51

Figure 14 Slide from the presentation uploaded to the S2P competition. (Source: Authors' elaboration) ... 53

Figure 15 Validation of customer segments based on Lean Startup Approach. (Source: Authors' elaboration) ... 55

Figure 16 App registration process. (Source: Authors’ elaboration) ... 66

Figure 17 TryMi types of users. (Source: Authors’ elaboration) ... 67

P

ag

.

IV

TABLE OF TABLES

Table 1 Average Prices of International restaurants in Milano. (Source: Various websites) ... 37 Table 2 Action plan activities. (Source Authors' elaboration) ... 48 Table 3 Traditional and Lean Startup approaches pros vs cons confrontation. (Source: Authors’ elaboration) ... 54

P

ag

.

V

TABLE OF GRAPHS

Graph 1 Gender question in the TryMi survey. (Source: From the TryMi survey developed by authors.) ... 57 Graph 2 Potential users age range. (Source: From the TryMi survey developed by authors.) ... 57 Graph 3 People who has a smartphone. (Source: From the TryMi survey developed by authors.) ... 58 Graph 4 Customer segmentation on the basis of the OS used by the customers. (Source: From the TryMi survey developed by authors.) ... 58 Graph 5 People who missed the traditional food from home while living abroad (Source: From the TryMi survey developed by authors.) ... 59 Graph 6 Taste for trying international food. (Source: From the TryMi survey developed by authors.) ... 59 Graph 7 Money spent while cooking a traditional meal (Source: From the TryMi survey developed by authors.) ... 60 Graph 8 How often people used to cook traditional dishes from their countries (Source: From the TryMi survey developed by authors.) ... 61 Graph 9 For how many people the cooks used to cook (Source: From the TryMi survey developed by authors.) ... 61 Graph 10 How often does foodies eat in international restaurants (Source: From the TryMi survey developed by authors.) ... 62 Graph 11 How money do foodies spend when eating in international restaurants. (Source: From the TryMi survey developed by authors.) ... 62 Graph 12 Cooks willingness to download the app. (Source: From the TryMi survey developed by authors.) ... 63 Graph 13 Foodies willingness to download the app. (Source: From the TryMi survey developed by authors.) ... 63

P

ag

.

1

1 ABSTRACT

Nowadays the world is experimenting a huge growth of technology development at exponential pace. Everyday most people get the opportunity to access to internet through any kind of devices, such as; personal computers, smartphones, tablets and televisions, among others. Together with the new wave of the so called ‘online trade & distribution channels’, create the perfect scenario for entrepreneurs, eager of conquering the world with new business ideas springing up every day, thus, implying the consumers and the markets have been experiencing a very high uncertainty on their behavior from one moment to another. Although the traditional business models and tools, have proved of being very effective, the new context includes variables of global markets, internet access, mobile devices development, increased uncertainty and higher expectations of customers, therefore, additional capabilities are required for a business, not only to be successful in the first place, but to hold the standards and stay in the game for long time. To have a faster pace and acquire the additional capabilities; the Lean Startup, which is not properly a business model, but a methodology to define and redefine – in an iterative way – the value proposition of a growing business, based on continuous improvement of the overall performance. This thesis intends to analyze both, the traditional and the Lean Startup approaches, not with the intention to confront them, but with the intention to fusion them in a model that takes the best out of each. TryMi is a business idea of a mobile application, that came to us during the master, while living in Italy as international students and observing the behavior of the international community in a global city as it is Milano. We present here, the results of applying the business models, methodologies and tool combination proposed to the TryMi business idea.

P

ag

.

2

2 SCOPE AND OBJECTIVES

The present document has been written to put in practice the knowledge absorbed in the courses attended during the master, as well as to bring into reality a business idea that came to us while living as international students in Milano, and it is aimed at:

• Evaluating the feasibility of the development of a mobile application (Mobile App) that combines the use of collaborative consumption with the pleasure for cooking/consuming international food, present in the international, young-adult population of Milano.

• Creating an appropriated, tailored business model for the application, and justify the selection of it, as well as the strategic decisions and tactics to be followed, to avoid the failure in a constantly changing environment.

• Comparing two approaches available for the creation of a new company – the business model canvas and the lean startup – and the strategic plan to last for long time.

As for the scope although we know the actual development of a business idea, especially in the mobile app world, entails so many aspects to be considered, we set the limits of the project only to the business models analysis and selection of the best suitable option for the creation of this app. However, we’d like to mention some important aspects that need to be considered for the actual development of the app in the real world but as for this project they are out of the scope.

Part of the scope

• Business model analysis • Business model comparison

• Best suitable business model proposal

Out of the scope

• Deep understanding of the legal aspects of the countries where the app is intended to be developed.

• Technical programming aspects related to the actual build-up of the app.

• Financial aspects such as campaigns for raising money, attract investors or fundraising.

P

ag

.

3

3 METHODOLOGY

The development of the present document started after the conception of the idea to create a mobile application for smartphones, in which users are aimed to share their cultural knowledge, love for food and cooking skills with people surrounding them in a friendly international environment, that will save costs in the kitchen for both.

For the first stage, it was necessary to research, via internet and through the mobile platforms in different operative systems, the possible existence of similar applications, to evaluate important aspects, such as; the novelty of the idea, the acceptance of the market, as well as the competence that the project would face, once launched, among others.

After the initial research, two first steps were followed; a literature review and a survey were needed to support, on the one hand the necessary managerial background, to set a proper strategy, business model and tactics to develop the project; and on the other hand, the justification for launching it, as a sort of market analysis, with the targeted market segment intended. The discussion of the ideas and information found in the literature review was made at the beginning with skype calls, and afterwards face-to-face with brainstorming meetings.

As a result of the initial review of the literature research we found two main possibilities to develop our project: the traditional strategic plan and the lean startup. Since the app will face conditions of uncertainty, the lean startup suggests the development of short experiments, to obtain validated learning, to improve the features on the way to launch the application, in an iterative way over time.

On the other hand, since the app will provide a service, it can’t be launched without a robust strategic plan, because it will fail if we can’t provide a good service level for the early adopters. Therefore, a comparison and a combination of both business approaches has been suited to our project to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of following each methodology.

A deeper analysis of the survey led us to confirm our hypotheses created to gain the validated learning and to define the activities of the action plan to establish the marketing strategy, the targeted customers and the selection of the best option for the platform to be chosen.

Finally, the outcomes; results found during the development of this project, the analysis of those results and final conclusions made on the basis of those previous analysis, are shown at the end of this document.

P

ag

.

4

4 INTRODUCTION

The original idea to develop TryMi, as a mobile application, was born during the transition we both suffered by changing radically our lifestyle when we first came to Milano. Before coming to Italy to study the master, both of us were working, and living with our families, satisfying most of our needs relatively easy. It was during the master, that we found ourselves involved in a huge multicultural environment, never experienced before, interacting with younger and older colleagues, from many different countries around the world, that were more familiar with the use of collaborative consumption as a way to save money while travelling.

Our passion for traveling, learning from other cultures and people, the melancholy of missing the food from home and the disappointment suffered when trying “Mexican food” in local restaurants at high prices, fostered our ability to cook most of the traditional dishes of Mexican cuisine, and encouraged our desire to share with friends from different nationalities our cooking skills with two objectives; first, to split the costs of cooking between more people and second, to enjoy the real taste of Mexican food with them. The business idea was settled; we needed to define the appropriate way to develop the concept. To do that, we divided the framework between the strategy, the technical aspects in which we should pay more attention, and the human and economic trends seen in a global city supporting the possible success of such idea.

As part of the strategy of a company, business models are essential to guarantee the success of any project. Over the past two decades, the term “business model” has frequently been misused by both, academics and practitioners, and it is common to hear the term being used by managers, consultants and scholars from diverse fields and even in the popular media. The term’s pervasiveness and use suggest that business models are extremely important; however, no consensus regarding its meaning has been established.

Today, there is a wide variety of existing business models, and the opportunities of creating new ones within the telecommunications industry are enormous. New and innovative ways of doing business are being discovered at a faster pace than ever before. Thus, advances in technology allow mobile phone manufacturers to generate revenues not only from the sale of their handsets and associated accessories, but also from several other sources.

As the marginal costs of conducting transactions in a digital world are close to zero, mobile phones have become a billion-dollar distribution channel where thousands of digital products, such as music, movies, photos, software and games are purchased and consumed instantaneously.

The technical background in which we started our research led us to a new and controversial approach that has been rising, supposedly better fitted for the chaotic world of entrepreneurial ventures. Shaped by scholars and practitioners of entrepreneurship, it has been commonly coined as the Lean Startup movement. It may seem like reversing the old product development model, but rather it is applying another dimension labelled as ‘Customer Development’, and the purpose is to work with both dimensions in parallel while establishing the company (Blank, 2005). Blank suggests “the customer and product development to be considered parallel activities, and must remain synchronized and operate in concert”.

P

ag

.5

The core idea behind the lean startup movement is to include the customers at a very early stage of the product development, to make sure that the product is solving a problem and that it is something customers are willing to pay for. Due to the nature of the customer development process, the approach is centered on continuous iterations where elements of the business plan get modified and improved over time based on the continuous feedback gathered by real life customers.

As important as the feedback from the customers, are the technological aspects needed to study deeper, since we were not familiar with software or applications’ development knowledge. Technological changes to development tools continually present challenges and opportunities for instructional technologists and others. Presently, the availability of a wide variety of app development tools and technologies invites consideration along multiple paths, including: the conception of what an app is, benefits for developers, costs, the similarities and differences among app development tools, operative systems platforms and creating instruction for apps.

Another important aspect that fostered the idea of TryMi as a successful project is the growing business of on-demand economy, the recent models have risen thanks to collaborative consumption; via collaborative consumption people share and gain access to rooms (AirBnB, Roomorama), tools (SnapGoods), cars and bikes (RelayRides, Wheelz), and ad hoc taxi services (Uber, Lyft). These platforms offer numerous advantages by unlocking the value inherent in sharing resources among people who want them (Malhotra & Van Alstyne, 2014).

By facilitating connection and interaction among people, the Internet lowers communication costs and makes it easier to participate in collaborative consumption even when the participants do not know each other. Involving strangers in collaborative consumption (beyond close relational boundary) could greatly expand its scale and impact, making it an even more pervasive phenomenon and more profitable practice for firms.

World-wide cities are increasingly seen as important engines of economic growth and sustainable development. This importance of modern cities, does not only depend on location advantages, but also on two other type of externalities: social-capital and connectivity.

The first category has been well described by Jacobs (1969) who has introduced the concept of an urban “melting pot”: cities with multiplicity of people, cultures, ethnics and languages, which may create tensions, but also form the seedbed conditions for innovative and creative behavior. The second one is based on the economies of connectivity either physical – roads and airports – or virtual – global information or internet networks.

Milano is considered one of these worldwide cities and in its background, it counts with at least one inhabitant from 171 different countries (registered by the immigration office); and around 450 thousand immigrants between men and women in total1.

All trends and facts above mentioned create a perfect scenario for the development of a mobile application such as the one established in the current document. The following sections will provide a deeper understanding about the selection of the business model and the steps ahead to complete the development of the App.

P

ag

.

6

5 LITERATURE REVIEW

In this chapter, we talk about the business models, methodologies, approaches and techniques in which we based the further analysis and development of the original business idea. The main idea of this project is to understand the pros and cons of the different business models and approaches existing in the literature, and to take advantage of the best features of each of them, to create a sort of mixed business model to be applied in a successful way when giving life to TryMi.

To survive in a constantly changing environment, where customers are always seeking for more, or even do not have idea what they are seeking for, and the risk of competitors and copycats skyrocketed in the last years, developing the right business strategy as well as being able to constantly readapt and reinvent are key aspects.

Moreover, to success in the aforementioned environment, the entrepreneurs have to always been searching for innovative ways to satisfy customer needs, and being able to understand what customers want is not always an easy task, especially in app business.

5.1 B

USINESSM

ODELSNowadays, business markets are getting more competitive and therefore, companies are trying to provide not only products or services to the customer, but also creating new ways of psychological satisfaction. This, motivate companies to focus more on innovation, so to increase their competitive advantage. On the other hand, in the case of startups, new companies try to be sustainable in rapidly changing markets. Yet, innovation process is very challenging and the success depends on many variables, which cannot be managed with the old tools or principles. Following these problems, new approaches such as design thinking and lean development emerged in business world, to manage innovation processes.

In a nutshell, the widespread use of the business model terminology seems to be intrinsically connected with technology based companies. Business models seemed to be the answer for explaining how innovative undertakings dealing with technology or any other form of unclear but potentially profitable concepts, foreign to the logic of traditional industries, were materialized in business terms. In fact, Internet companies could not be valued based on their past performance since there were no precedents. As a result, investors speculated about the compelling future promises, based on innovative business models (Thornton and Marche, 2003).

However, the problem does not lie with the term itself but with its lack of understanding and misuse. If a business model’s core, stands on untested or speculative assumptions about the future, the firm is doomed to an uncertain outcome. For example, Pets.com assumed its extravagant marketing expenses and consequent brand awareness would be offset by large amounts of purchases, but that didn’t happen. In its 2008 “Global CEO Study” IBM revealed that companies from a broad range of fields and industries were actively seeking advice on how to innovate their existing business models (IBM Global Business Services, 2008).

Porter (2001, p. 71) notes that taking the business model in isolation from the company’s strategy, may hinder the firm’s most important advantages. Numerous cases supporting this view can be found in the mobile application industry. When companies launch a successful mobile application on the market, one thing is certain: copycats are just

P

ag

.7

The initial business model of a certain company, may prove successful, meaning the decisions made and the consequences of such decisions generate a positive outcome within a certain timeframe. But to outperform competitors in the long run, strategists must consider three important steps:

1. First, they need to, not only choose the right combination of resources (in line with the resource-based theory) but also the most efficient transactions (in line with the TCE2) at a time.

2. Second, they must be able to renew their distinctiveness as competition threatens, through the constant development and nurturing of dynamic capabilities.

3. Third, they must be able to redefine their business model in a quick and effective manner, in accordance with the strategy and the contingencies presented along the road. Firms must analyze their competitive environment, define their position, develop competitive and corporate advantages, and understand better how to sustain those advantages in the face of competitive challenges and threats. While it has become uncontroversial to argue that managers must have a good understanding of how business models work if their organizations are to thrive, the academic community has only offered early insights on the issue to date, and there is (yet) no agreement as to the distinctive features of superior business models. We believe this is partly because of a lack of a clear distinction between the notions of strategy, business models and tactics. (Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart 2010) differentiate these three concepts as follows:

• Business Model Refers to the logic of the firm, the way it operates and how it creates value for its stakeholders.

• Strategy Refers to the choice of business model through which the firm will compete in the marketplace. While

• Tactics Refers to the residual choices open to a firm by virtue of the business model it chooses to employ.

To integrate these three concepts, they introduce a generic two-stage competitive process framework, as depicted in Figure 1. In the first stage, firms choose a ‘logic of

value creation and value capture’ (i.e., choose their business model), and in the second,

make tactical choices guided by their goals (which, in most cases, entail some form of stakeholder value maximization). Figure 1, thus, presents the organizing framework: the object of strategy is the choice of business model, and the business model employed determines the tactics available to the firm to compete against/or cooperate with, other firms in the marketplace.

Figure 1 Generic two-stage competitive process framework. (Source: Cassadesus et al., 2010, Adapted)

2 Transaction Cost of Economics

P

ag

.

8

It is necessary to define ‘a good business model’ as the one that provides answers to the following questions:

• ‘Who is the customer and what does the costumer value?’

• ‘What is the underlying economic logic that explains how we can deliver value to customers at an appropriate cost?’

While not formal, the implicit idea is that a business model is about how an organization earns money by addressing these two fundamental issues and how it identifies and creates value for its customers, to finally capture some of this value as its profit in the process.

To better understand business models, its needed to understand their component parts and their relationships. As an easier way to explain it, an analogy could be used: the design and building of the car represent the strategy; the car itself is the business model; and the driving of the car is the available set of tactics. To define the parts that business models are made of; authors established two different sets of elements;

a) The concrete choices made by management about how the organization must operate, and

b) The consequences of these choices.

Likewise, pricing policies (choices) have obvious implications regarding sales volumes, which in turn, affect the economies of scale and bargaining power enjoyed by the firm (as two of its consequences). Following we distinguish three types of choices:

1. Policy choices: Courses of action that the firm adopts for all aspects of its operation.

2. Asset choices: Decisions about tangible resources.

3. Governance choices: Refer to the structure of contractual arrangements that confer decision rights over policies or assets.

Transaction cost economics (TEC), suggests that seemingly slight differences in the governance of policies and assets can have dramatic effects on value creation and/or value capture.

A useful way to represent business models is by means of a casual loop diagram, where choices and consequences are linked by arrows based on causality. Figure 2 is a representation of Ryanair’s business model, where underlined elements are choices and non-underlined elements are consequences. Consequences in boxes are “rigid” and those not in boxes are “flexible”. A consequence is flexible if it is highly sensitive to the choices that generate it. These causes and consequences generate virtuous circles that sometimes are essential for the business model, so this kind of representation helps also to map the success factors.

P

ag

.9

Figure 2 Ryanair’s’ business model representation. (Source: Cassadesus et al., 2010)

Despite the utility of casual loop diagrams; complete business models are often too complex and unwieldy to represent for working with, so the analysts must simplify their representation, to better understand them. There are two main ways to move from the full, through detail, to a tractable representation of a business model:

• Aggregation. We can think of aggregation as ‘zooming out’ and looking at the (real) business model from a distance, ‘bunching together’ detailed choices and consequences into larger constructs.

o By zooming out, although details blur, larger ‘chunks’ - aggregations of those details become clearer. Finding the ‘right distance’ from which to assess a given business model is more an art than a science.

• Decomposition. Some business models are decomposable, in the sense that different groups of choices and consequences do not interact with one another and thus can be analyzed in isolation.

In continuing the research to establish a proper definition of business model and to integrate the concepts of strategy, tactics and business models, we found as one of the most complete definition the one provided by Chesbrough and Rosenbloom:

“The functions of a business model are to: articulate the value proposition, identify a market segment, define the structure of the value chain, estimate the cost structure and

profit potential, describe the position of the firm within the value network, and formulate the competitive strategy”.3

P

ag

.

10

To cement the three notions, consider once again the automobile analogy (where the automobile corresponds to the business model, and driving the automobile corresponds to tactics). Imagine that, prior to operating the automobile, the driver could modify the features of the car: shape, power, consumption, seats, A/C system. Such modifications would not be tactical - detailed changes in how the car is driven - they would constitute ‘strategies’, because they would entail changing the machine (the ‘business model’) itself.

Figure 3 it is useful to clarify the differences between those three concepts. The substantive difference between strategy and business model arises when the firm’s plan of action calls for modifications to the business model (changes in policies and/or assets and/or governance) when contingencies take place.

To summarize, strategy is much more than the mere selection of a business model; it is a contingent plan as to how the business model should be configured, depending on contingencies that might occur. It is also worth discussing the difference between strategic and tactical choices: while strategic ones are difficult to change because of the commitment shown by the firm, on the other hand tactical ones are relatively easier to modify.

P

ag

.

11

5.1.1 Business Models and technology

To create a link between the business models terminology and the environment in which the project will be developed, we decided to continue our research checking the business models available in the app sector; an important starting point was to understand the trend and the evolution of the mobile platform ecosystem, because, start-ups applications can’t be launched at the same time in all platforms, due to the increasing costs, and unless they cover specific needs of the users of some platforms, they shouldn’t be launched in the less popular ones.

Basole and Karla (2011), provide a deeper understanding of the evolving structure and strategies used in the mobile platform ecosystem over the period between 2006 and 2010, and they decided to split the market in 4 segments:

• mobile device manufacturers (MDM), • mobile network operators (MNO),

• mobile application developers (MAD), and • mobile platform providers (MPP).

The value, design, and management of technology platforms, has been a topic of increasing interest to both researchers and practitioners. Gawer and Henderson (2007), suggests that many high-tech products and services can be considered as “systems of interdependent components, built around and on top of platforms” and are often provided by a complex network of firms. In her seminal work, Oliver (1990) suggested that interfirm relations are a result of six fundamental determinants, namely asymmetry, reciprocity,

efficiency, stability, legitimacy, and necessity.

In emerging technology industries, networks and alliances were found particularly beneficial due to the ability for firms to share risks, to develop, and to have access to synergistic knowledge (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven 1996, p. 136).

The mobile business market is highly dynamic particularly due to continuous technological advances. Consequently, the mobile industry has been described as a complex system with numerous inter-firm relationships across multiple segments (Basole 2009; Rosenkopf and Padula 2008).

The success of smartphones has led to a virtual battle of mobile platforms in the mobile ecosystem. In 2011 there were over 40–50 different mobile platforms, but seven of them held approximately 97% of the entire market (Nielsen 2010). Key players included Symbian, Windows Mobile, BlackBerry, webOS, multiple variants of Linux-based platforms, and the beginnings of Apple’s iOS and Google’s Android. However, during the last 5 years the number of players has been reduced practically to the battle between iOS and Android, all over the world, and some big contenders like Symbian doesn’t even appear anymore as the operative system of any cellphone4.

From the same study quoted before we also observed that the trend had been modified quite fast during the last 5 years, because the evidence was leading to conclude that MDMs (e.g. Samsung, Motorola and LG) would be still waiting for a dominant platform to emerge and use it in their devices, instead, for example Motorola was bought by Google in 2012 to be sold later to Lenovo in 2014 with an apparent loss of 10 billion dollars5, which made the rest of the MDMs first, to be afraid of competing vs an integrated software-hardware company and this fact caused afterwards the embracement of android OS as the to-be dominant platform in the industry.

4https://www.pcmag.com/feature/307321/the-10-best-symbian-phones-ever/7

P

ag

.

12

The fundamental reason for the rapid transformation of value creation and delivery in the mobile ecosystem has been the introduction of app stores which are tied to their respective platforms (Operative Systems). App stores serve as electronic markets for digital goods and enable ecosystem participants to collaborate and offer their services for a platform.

App stores tend to be the primary gateway for end users to mobile applications and content. Consequently, platform app stores will play a critical role in the future development of the mobile business ecosystem.

Then for choosing the right platform to launch a new app, developers must answer to the question: “Which platform provides MNOs the greatest increase in average revenue per user?” because of its importance to all stakeholders in the ecosystem. Similarly, the goal of MPPs is therefore to become the preferred platform through collaborations and partnerships with its key enabling segments, MADs, MDMs and MNOs.

In our structural analysis, this goal translates to MPPs aiming to gain a more prominent position in the mobile ecosystem, the battle we see every day between iOS and Android. Due to this; developers must custom code their applications for use on multiple platforms. This is both cost and resource intensive and increases time-to-market (TTM) for applications.

Kulins, Leonardy and Weber (2015) describe the relationship between business model design and financial performance; they based their study using a configurational perspective that evaluates the interdependencies of complementarity, efficiency, novelty, and lock-in-based business models of 41 entrepreneurial firms. Influenced by the NICE-framework by Amit and Zott (2001), which connects the 4 dimensions as value drivers for business model design. However, only two out of the four design themes of business models hold relation with firms' market value.

The findings demonstrate that the framework's implications on performance, indeed, heavily depend on interrelated design themes and that viewing those themes alone biases findings, because the focus is too narrow.

Amit and Zott (2001, p. 501) define business models as “the content, structure, and governance of transactions designed so as to create value through the exploitation of business opportunities.” As well, they define the 4 dimensions as follows:

• Complementarities: Synergies between product/service offerings in the business model.

• Efficiency: Minimization of transaction costs among stakeholders.

• Lock-in: Imposition of switching costs on different participants in the business model.

• Novelty: New ways of organizing transaction flows between stakeholders. The findings state that only efficiency and novelty had an impact in financial performance, while lock-in is the only dimension that is not necessarily beneficiary to customers/users. Therefore, firms must combine it with other dimension to foster adoption and to be a significant value driver.

P

ag

.

13

The 41 firms under analysis went public between 2009 and 2012 on the NASDAQ or NYSE, and the study applied a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). It revealed three different solutions (combination of dimensions) to evaluate high market value as the outcome to evaluate the success obtained by the configuration chosen by the firm for its business model.

The best combination turned out to be Efficiency-novelty, this is not surprising due to the fact that both dimensions are as stated before the only ones that impact financial performance. Hence innovation in business model is a driver of success if it appears in connection with other value driver. Although difficulties in implementing these two design themes in parallel may occur, their successful employment seems to create complementarities that subsequently increase chances of achieving market value. 5.1.2 The Business Model Canvas

In 2008 Alexander Osterwalder developed the business model canvas, a strategic tool to develop new business models or to map existing ones. It’s a chart drawn with the elements that describe a company, its products (value propositions), infrastructure, customer and financial aspects.

By comparing this tool with the traditional Strategic plan, which establishes with higher level of detail the objectives, policies and tactics as well as the time to achieve them, it might seem to have a different approach. Instead both methodologies are complementary and each one fulfills the other.

Ortiz Rodríguez and Capó Vicedo in 2015 proposed a model to integrate both methodologies for the creation/evaluation of the business model, comparing the similarities, but finding the key aspects in which both are the complement of the other one to build a robust and feasible company plan. Their model follows the logical order of the traditional strategic plan, and while doing the analysis, the most important aspects are highlighted as part of the business model canvas.

The Business Model Canvas (BMC) is a concept that allows to describe and manage the business model of a company, it should be simple, relevant and easily understandable by everyone, but at the same time it shouldn’t simplify in excess the complexity of the enterprise. It’s divided in 9 modules which reflect the logic to get incomes. The modules cover the four main areas of the business: customers, offer, infrastructure and economic feasibility. Therefore, the Business model is a draft of a strategy that will be implemented in the structure, process and systems of the company.

It’s also worthy to mention that the BMC will facilitate the communication of the mission and vision through the company and this will, presumably, translate into an increase of the human and material resource efficiency to finally produce an increment in the benefits. The negative side of the BMC is the lack of depth in the information shown, and in many cases, is not enough clear to understand the position of the company accurately. To develop in parallel the strategic plan and the BMC, Ortiz Rodríguez and Capó Vicedo proposed a 10 step methodology to obtain the information of the two models that will have different perspectives but will be complementary in the end.

P

ag

.

14

Figure 4 shows how the content of every module of the BMC is linked to the points of the strategic plan; the points 4 and 5 are not in any particular module since they are present in every module of the BMC and they recap the information of the strategic plan as well.

1. Define the mission and vision 2. External analysis 3. Internal analysis 4. SWOT analysis 5. SWOT matrix 6. Market segmentation 7. Targeting 8. Positioning

9. Segmentation strategy and Marketing mix 10. Action plan

Figure 4 Business Model Canvas and Strategic Planning relationship (Source: Borja et al., 2015. Adapted) In the following chapter, we will use this approach to describe the traditional strategic plan for our startup, concluding with the business model canvas draft, we will point out as well the pros and cons of using this methodology compared with the Lean startup, to finally create a more robust Business Model.

5.1.3 The Lean Startup

When trying to implement a project or create a company, once a team is set up what should it do? What process should it use? How should it be held accountable to performance milestones? These are the questions the lean start-up is aimed to answer. The Lean Startup Model is a set of practices aimed at helping entrepreneurs increase their odds of building a successful startup: “A human institution designed to create a new product or service under conditions of extreme uncertainty”.

To open up a new business that is an exact clone of an existing business all the way down to the business model, pricing, target customer, and product may be an attractive economic investment, but it is not a startup because its success depends only on execution.

P

ag

.

15

Innovation is a bottoms-up, decentralized, and unpredictable thing, but that doesn’t mean it cannot be managed. In other words, cultivating entrepreneurship is the responsibility of senior management. We often lose sight of the fact that a startup is not just about a product, a technological breakthrough, or even a brilliant idea. A startup is greater than the sum of its parts; it is an acutely human enterprise.

Eric Ries believes that a company’s only sustainable path to long-term economic growth is to build an “innovation factory” that uses Lean Startup techniques to create disruptive innovations on a continuous basis.

Following we present some of the comments regarding the book published by Eric Ries, in 2011 called “The Lean Startup Methodology”.

“The lean startup is about what we can learn from businesses to improve virtually everything we do. It’s ultimately an answer to the question ‘How can we learn more quickly what works, and discard what doesn’t?”.

-Tim O’Reilly, CEO, O’Reilly Media Nowadays thousands of startups popup everywhere and every time, aiming to serve different markets, offering different services/products, and through different channels, but the reality is that most startups fail. Most new products are not successful. Most new ventures do not live up to their potential.

In his book, Eric Ries, says that he has learned from both his own successes and failures and those of many others that in entrepreneurship, and any other business, it’s the boring stuff that matters the most. Startup success is not a consequence of good genes or being in the right place at the right time. Startup success can be engineered by following the right process, which means it can be learned, which means it can be taught.

Following we present what Eric calls the five principles of the Lean Startup Methodology. • Entrepreneurs are everywhere

• Entrepreneurship is management • Validated learning

• Build-Measure-Learn • Innovation accounting

Why Startups Fail

When it comes to success/fail rate of the overall startups around the world, one of the questions we can might feel curious to ask is why are startups failing so badly everywhere we look? The first problem is the allure of a good plan, a solid strategy, and thorough market research.

In earlier eras, these things were indicators of likely success. The overwhelming temptation is to apply them to startups too, but this doesn’t work, because startups operate with very high levels of uncertainty. Startups do not yet know who their customer is or what their product should be. As the world becomes more uncertain, it gets harder and harder to predict the future. The old management methods are not up to the task. Planning and forecasting are only accurate when based on a long, stable operating history and a relatively static environment. Unfortunately, Startups have neither.

Startups may have a destination in mind, called vision. To achieve that vision startups, employ a strategy, which includes a business model, a product roadmap, a point of view about partners and competitors, and ideas about who the customer will be. Products change constantly through the process of optimization, which Eric calls, tuning the engine.

P

ag

.

16

In real life, a startup is a portfolio of activities, in the sense that a lot is happening simultaneously; the engine is running acquiring new customers and serving existing ones, we are tuning, trying to improve our product, marketing and operations, and we are steering, deciding if and where to pivot. The challenge of entrepreneurship is to balance all these activities.

Anything customers experience from their interaction with a company should be considered part of that company’s product. In any case, the organization is dedicated to uncovering a new source of value for customers and cares about the impact of its product on those customers. We must learn what customers really want, not what they say they want or what we think they should want.

In general management, a failure to deliver results is due to either a failure to plan adequately or a failure to execute properly. Most tools from general management are not designed to flourish in the harsh soil of extreme uncertainty in which startups thrive. Yet, new product development in our modern economy routinely requires exactly this kind of failure on the way to greatness.

Leadership requires creating conditions that enable employees to do the kind of experimentation that entrepreneurship requires.

In the Lean Startup Model, we are rehabilitating learning, with a concept called validated

learning, which is a rigorous method for demonstrating progress when one is embedded

in the soil of extreme uncertainty in which startups grow.

Validated learning is the process of demonstrating empirically that a team has discovered valuable truths about a startup’s present and future business prospects. It is more concrete, more accurate, and faster than market forecasting or classical business planning.

When starting a startup development process, it is crucial to have valuable knowledge about which efforts are value creating and which ones are wasteful, since a startup, usually affected by limited resources (human and capital) in the very first stages, it become of high importance to reduce wasting those resources at the minimum possible. And wasting efforts means wasting human resources and may hinder the creation of the true valuable offer of the company to its customers.

Moreover, wasting efforts it’s not only a waste of time and money, but it can act as well as a demoralization factor within the company and its employees, which suddenly realize that all/of some important parts of their hard work, ended up being worthless for the customers.

Lean thinking defines value as providing benefit to the customer, anything else is waste. In a manufacturing business, customers don’t care how the product is assembled, only that it works correctly. But in a startup, who the customer is and what the customer might find valuable are unknown.

The question is not “Can this product be built?”. The more pertinent questions are “Should this product be built?” and “Can we build a sustainable business around this set of products and tactics?” To answer those questions, we need a method for

systematically breaking down a business plan into its component parts and testing each part empirically.

In other words, we need the scientific method. In the Lean Startup model, every product, every feature, every marketing campaign – everything a startup does – is understood to be an experiment designed to achieve validated learning.

P

ag

.

17

In the Lean Startup model, an experiment is more than just a theoretical inquiry, it is also a first product. If this, or any other experiment, is successful, it allows the manager to get started with his or her campaign. By the time that product is ready to be distributed widely, it will already have established customers. It will have solved real problems and offer detailed specifications for what needs to be built.

Unlike traditional strategic planning or market research process, this specification will be rooted in feedback on what is working today rather than in anticipation of what might work tomorrow.

Now we present four key questions in order to justify any project, from Eric Ries’s book “The Lean Startup Methodology”. (Kodak Gallery’s vice president = Mark Cook)

• Do consumers recognize that they have the problem you are trying to solve? • If there was a solution, would they buy it?

• Would they buy it from us?

• Can we build a solution for that problem?

“Until we could figure out how to sell and make the product, it wasn’t worth spending any engineering time on”

- Mark Cook Today’s managers challenge is to overcome the prevailing management thinking that puts its faith in well-researched plans. Remember, planning is a tool that only works in the presence of a long and stable operating history. And yet, do any of us feel that the world around us is getting more and more stable every day? Changing such a mind-set is hard but critical to startup success.

As its heart, a startup is a catalyst that transforms ideas into products. As customers interact with those products, they generate feedback and data. The feedback is both qualitative (such as what they like and don’t like) and quantitative (such as how many people use it and find it valuable.

The Build-Measure-Learn feedback loop is at the core of the Lean Startup model. We need to focus our energies on minimizing the total time through this feedback loop. To apply the scientific method to a startup, we need to identify which hypotheses to test. The two most important assumptions are the value hypothesis and the growth

hypothesis.

Once clear on these leap-of-faith assumptions, the first step is to enter the Build phase as quickly as possible with a minimum viable product (MVP). The MVP is that version of the product that enables a full turn of the Build-Measure-Learn loop with a minimum amount of effort and the least amount of development time, which is in line with what we have mentioned before when we talk about reducing waste efforts at the minimum possible.

In this iterative process, it’s important to establish learning milestones, that are useful for entrepreneurs as a way of assessing their progress accurately and objectively. Upon completing the Build-Measure-Learn loop, we confront the most difficult question any entrepreneur faces; whether to pivot the original strategy or persevere.

From Toyota’s Lean approach there is a sentence they use a lot “Genchi gembutsu” that means “Go and see for yourself”. That is because they think – very accurately – that you cannot be sure you really understand any part of any business problem unless you go and see for yourself firsthand. It is unacceptable to take anything for granted or to relay on the reports of others.

P

ag

.

18

We’ve mentioned before the importance of having an early contact with the potential customers. The goal of such early contact with customers is not to gain definitive answers, but to clarify at a basic level that we understand our potential customer(s) and what problems they have.

This archetype is an essential guide for product development and ensures that the daily prioritization decisions that every product team must make are aligned with the customer to whom the company aims to attract.

The customer archetype is a hypothesis, not a fact. The customer profile should be considered provisional until the strategy has shown via validated learning that we can serve this type of customer in a suitable way.

Analysis paralysis

There are two ever-present dangers when entrepreneurs conduct market research and talk to customers. Followers of the just-do-it school of entrepreneurship are impatient to get started and don’t want to spend time analyzing their strategy. Other entrepreneurs can fall victims of analysis paralysis, i.e. endlessly refining their plans.

If too much analysis is dangerous but none can lead to failure, how do entrepreneurs know when to stop analyzing and start building?

The answer is in the early adopters; early adopters accept/prefer an 80 percent solution; you don’t need a perfect solution to capture their interest. Deciding exactly how complex an MVP needs to be, requires judgement. Most entrepreneurs and product development people dramatically overestimate how many features are needed in an MVP. And the simplest solution to that dilemma is, “When in doubt, simplify”. Then deliver it to the early adopters.

When it comes to quality, modern production processes rely on high quality to boost efficiency. They operate using W. Edwards Deming’s famous dictum that the customer is the most important part of the production process. This discussion of quality presuppose that the company already knows what attributes of the product the customer will perceive as worthwhile, which in most of the cases that kind of assumptions are neither easy nor trustworthy for startups.

In a startup, often, we are not even sure who the customer is. Eric Ries believes that for startups the quality principle is the following: “If we don’t know who the customer is, we

do not know what quality is”.

Sometimes, MVPs are perceived as low-quality by customers, if so, we should use this as an opportunity to learn what attributes customers care about. This is infinitely better than mere speculation because it provides solid empirical foundation on which to build future products.

In traditional management, a manager who promises to deliver something and fails to do so is in trouble. There are only two possible explanations: a failure of execution or a failure to appropriately planning. We all need a disciplined, systematic approach to figuring out if we’re making progress and discovering if we’re achieving validated learning. Eric Ries calls this system “Innovation accounting”, and it is an alternative to traditional accounting designed specifically for startups.

The rate of growth of a normal company selling products/services depends primarily on three things: the profitability of each customer, the cost of acquiring new customers, and the repeat purchase rate of existing customers. The higher these values are, the faster the company will grow and the more profitable it will be. These are the drivers of the company’s growth model.

P

ag

.

19

By contrast, a marketplace company that matches buyers and sellers such as eBay will have a different growth model. Its success depends primarily on the network effects that make it the premier destination for both buyers and sellers to transact business. Sellers want the marketplace with the highest number of potential customers. Buyers want the marketplace with the most competition among sellers, which leads to the greatest availability of products and the lowest prices.

That is basically in line with metcalfe’s law, that states that “The value of a network, is

proportional to the square of the number of participants”. In other words, the more people

in the network, the more valuable the network.

For this kind of startup, the important thing to measure is that the network effects are working, as evidenced by the high retention rate of new buyers and sellers.

To better understand how does innovation accounting works, we can take a look at these following steps:

1. Use a MVP to establish real data on where the company is right now.

2. Tune the engine from the baseline toward the idea. (This may take many attempts).

3. Decision point: Pivot or persevere?

The word pivot sometimes is used incorrectly as a synonym for change. A pivot is a special kind of change designed to test a new fundamental hypothesis about the product, business model, and engine of growth. When a company pivots, it starts the process all over again. The sign of a successful pivot is that these engine-tuning activities are more productive after the pivot than before.

The critical behaviors influencing the actual growth of a startup are: customer registration, the download of the app, trial, repeat usage, and purchase.

Eric suggests using cohort analysis, that instead of looking at cumulative totals or gross numbers such as total revenue and total number of customers, looks at the performance of each group of customers that comes into contact with the product independently. This technique is useful because every company depends for its survival on sequences of customer behavior called flows. Customer flows govern the interaction of customer with a company’s products.

One of the very helpful tools to understand what customer like/dislike of a specific product is called “Split-test experiment”, and it is a kind of experiment in which different versions of a product are offered to different customers at the same time, in order to maximize the potential feedback loop coming from the customers in each of both “sides” of the experiment. In this way, the process to obtain validated learning will require less time, and therefore the company will have better and faster results in which to base their next following decisions and steps.

The three A’s of metrics.

• Actionable: For a report to be considered actionable, it must demonstrate clear cause and effect. Actionable metrics are the antidote to the problem. When cause and effect is clearly understood, people are better able to learn from their actions. Human beings are innately talented learners when giving a clear and objective assessment.

P

ag

.

20

• Accessible: Make the reports as simple as possible, so that everyone understands them. This is why cohort-based reports are the gold standard of learning metrics: they turn complex actions into people-based reports. Each cohort analysis says: among the people who used our product in this period, here’s how many of them exhibited each of the behaviors we care about. Accessibility also refers to widespread access to the reports. Reports well laid out and easy to read.

• Auditable: To ensure that the data is credible to employees. We need to be able to test the data by hand, in the messy real world, by talking to customers. This is the only way to be able to check if the reports contain true facts. Managers need the ability to spot check the data with real customers.

Only 5 percent of entrepreneurship is the big idea, the business model and the whiteboard strategizing. The other 95 percent is the gritty work that is measured by innovation accounting.

There is a very important matter within the Lean Startup, and it is to know when to pivot and when to persevere. And to know the answer we must ask a very simple, but tricky, question: are we making sufficient progress to believe that our original strategic hypothesis is correct, or do we need to make a major change?

That change is called a pivot: a structured course correction designed to test a new hypothesis about the product, strategy and engine of growth. A pivot requires that we keep one foot rooted in what we’ve learned so far, while making a fundamental change in strategy in order to seek even greater validated learning.

The true measure of runway is how many pivots a startup has left: the number of opportunities it has to make a fundamental change to its business strategy. Measuring runway through the lens of pivots rather than that of time suggests another way to extend that runway: get to each pivot faster. In other words, the startup has to find ways to achieve the same amount of validated learning at lower cost or in a shorter time. One of the classic signs of the need to pivot is when the efforts made in order to tuning the engine, start reaching diminishing returns.

A catalog of pivots

Pivots come in different favors.

Zoom-in Pivot In this case, what previously was considered a single feature in a

product becomes the whole product. This is the type of pivot Votizen made when it pivoted away from a full social network and toward a simple voter contact product.

Zoom-out Pivot In the reverse situation, sometimes a single feature is insufficient to

support a whole product. In this type of pivot, what was considered the whole product becomes a single feature of a much larger product.

Customer Segment Pivot In this pivot, the company realizes that the product it is

building solves a real problem for real customers but that they are not the type of customers it originally planned to serve. In other words, the product hypothesis is partially confirmed, solving the right problem, but for a different customer than originally anticipated.

P

ag

.

21

Customer Need Pivot As a result of getting to know customers extremely well, it

sometimes becomes clear that the problem we’re trying to solve for them is not very important. However, because of this customer intimacy, we often discover other related problems that are important and can be solved by our team. In many cases, these related problems may require little more than repositioning the related problems may require little more than repositioning the existing product. In other cases, it may require a completely new product. Again, this a case where the product hypothesis is partially confirmed; the target customer has a problem worth solving, just not the one that was originally anticipated.

A famous example is the chain Potbelly Sandwich Shop, which today has over two hundred stores. It began as an antique store in 1977; the owners started to sell sandwiches as a way to bolster traffic to their stores. Pretty soon they had pivoted their way into an entirely different line of business.

Platform Pivot A platform pivot refers to a change from an application to a platform or

vice versa. Most commonly, startups that aspire to create a new platform begin life by selling a single application, the so-called killer app, for their platform. Only later does the platform emerge as a vehicle for third parties to leverage as a way to create their own related products. However, this order is not always set in stone, and some companies have to execute this pivot multiple times.

Business Architecture Pivot This pivot borrows a concept from Georey Moore, who

observed that companies generally follow one of two major business architectures: high margin, low volume (complex systems model) or low margin, high volume (volume operations model).6 The former commonly is associated with business to business (B2) or enterprise sales cycles, and the latter with consumer products (there are notable exceptions). In a business architecture pivot, a startup switches architecture. Some companies change from high margin, low volume by going mass market (e.g., Google’s search “appliance”); others, originally designed for the mass market, turned out to require long and expensive sales cycles.

Value Capture Pivot There are many ways to capture the value a company creates.

These methods are referred to commonly as monetization or revenue models. These terms are much too limiting. Implicit in the idea of monetization is that it is a separate “feature” of a product that can be added or removed at will. In reality, capturing value is an intrinsic part of the product hypothesis. Often, changes to the way a company captures value can have far-reaching consequences for the rest of the business, product, and marketing strategies.

Engine of Growth Pivot As we’ll see in Chapter 10, there are three primary engines of

growth that power startups: the viral, sticky, and paid growth models. In this type of pivot, a company changes its growth strategy to seek faster or more profitable growth. Commonly but not always, the engine of growth also requires a change in the way value is captured.

Channel Pivot In traditional sales terminology, the mechanism by which a company

delivers its product to customers is called the sales channel or distribution channel. For example, consumer packaged goods are sold in a grocery store, cars are sold in dealerships, and much enterprise software is sold (with extensive customization) by consulting and professional services firms. Often, the requirements of the channel determine the price, features, and competitive landscape of a product. A channel pivot is a recognition that the same basic solution could be delivered through a different channel with greater effectiveness. Whenever a company abandons a previously complex sales process to “sell direct” to its end users, a channel pivot is in progress. It