Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna Università degli Studi di Siena Università degli Studi di Firenze Università di Pisa PhD Course

Political Science, European Politics, and International Relations Academic Year 2016/2019

Political Participation in

Latin America:

A Comparative Analysis

of Its Determinants and

Implications

Author

Adrián Pignataro López

Supervisor

ii

Contents

List of Figures iv List of Tables v Acknowledgments vii Abstract ix 1 Introduction 1 A Paradox 1Participation and Democracy 7

Research Questions 10

Case Selection and Context 11

Data and Measurement 16

Structure of the Dissertation 18

Methodological Issues 20

2 The State of the Literature on Political Participation 23

Defining Participation 23

Explaining Participation 27

Concluding remarks 39

3 Political Participation in Latin America: Patterns and Structure 41

Introduction 41

Rates of Participation 42

The Structure of the Participatory Behavior 48

Concluding Remarks 53

4 Macro-level Explanations of Political Participation: Turnout and Beyond 56

Introduction 56

A First Look 57

Turnout 62

Participation Beyond Voting 79

Conclusion 84

5 Political Participation at the Individual Level: Resources, Attitudes, and

Government Evaluation 88

Introduction 88

iii

Theoretical Argument and Hypotheses 91

Data and Measures 95

Results 100

Discussion 112

Conclusion 116

6 Consequences of Participation 118

Introduction 118

The Effects of Participation on Government Performance 119

Political Participation and Life Satisfaction 121

Data 124

Results 127

Discussion and conclusion 134

7 Conclusions 138

The Problematic Concept of Participation 139

Context and Rates of Participation 141

Resources and Evaluations in the Decision of Participating 145

The Unexpected Consequences of Participation 149

If Dissatisfaction Is Common, Why Is Participation Scarce? 151

Appendix A Voting Rules in Latin America 153

Appendix B Additional Data 155

Appendix C Codebook for the 2012 LAPOP Survey 159

Appendix D Questions in the 2012 LAPOP Survey 162

Appendix E Additional Estimates 167

iv

List of Figures

FIGURE 1.1 Comparative rates of political participation 3

FIGURE 1.2 Trends of worldwide political participation beyond voting 5 FIGURE 2.1 The Civic Voluntarism Model 35

FIGURE 3.1 Total number of participatory acts 47

FIGURE 3.2 Correlations at the country-level between types of participation 52

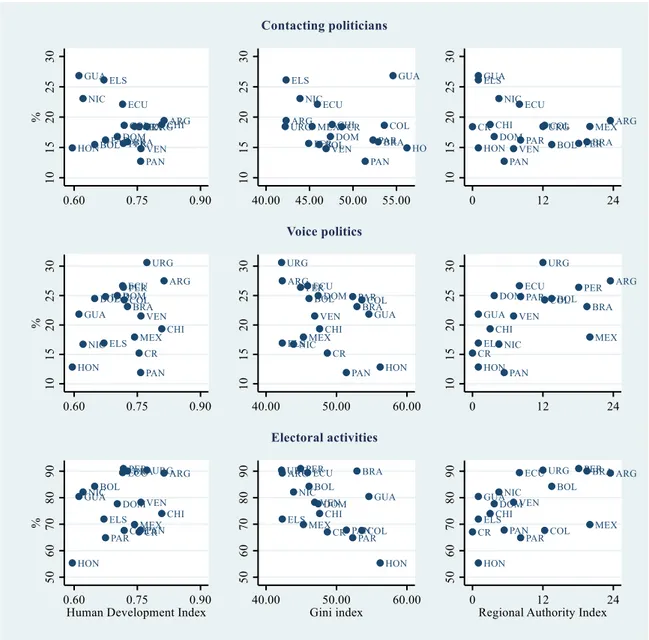

FIGURE 3.3 Combinations of the types of political participation 53 FIGURE 4.1 Correlates of the types of participation at the country level 62

FIGURE 4.2 Turnout in Latin America 66

FIGURE 4.3 Turnout across modes of registration 70

FIGURE 4.4 Turnout and mandatory voting rules 71

FIGURE 5.1 Theoretical model of the decisional process of political participation 93

FIGURE 5.2 Voting and other forms of political participation 96

FIGURE 5.3 Marginal effects of independent variables on voting 102

FIGURE 5.4 Marginal effect of legitimacy on the probability of voting 103

FIGURE 5.5 Marginal effects of independent variables on participation beyond voting 106

FIGURE 5.6 Marginal effect of legitimacy on the probability of voice politics and both

voice politics and contacting 107

FIGURE 5.7 Marginal effect of executive approval on the probability of voice politics

and both voice politics and contacting 108

FIGURE 5.8 Predicted probabilities for each outcome according to the multinomial model 110

FIGURE 5.9 Interactive effects of political interest and approval 112

FIGURE 6.1 Life satisfaction in 18 Latin American countries 126

v

List of Tables

TABLE 1.1 The role of participation according to perspectives of democracy 8

TABLE 1.2 Cases selected 14 TABLE 1.3 Technical information of the 2012 LAPOP survey 17

TABLE 1.4 Items of political participation included in the 2012 LAPOP survey 18

TABLE 2.1 Some concepts of political participation 24

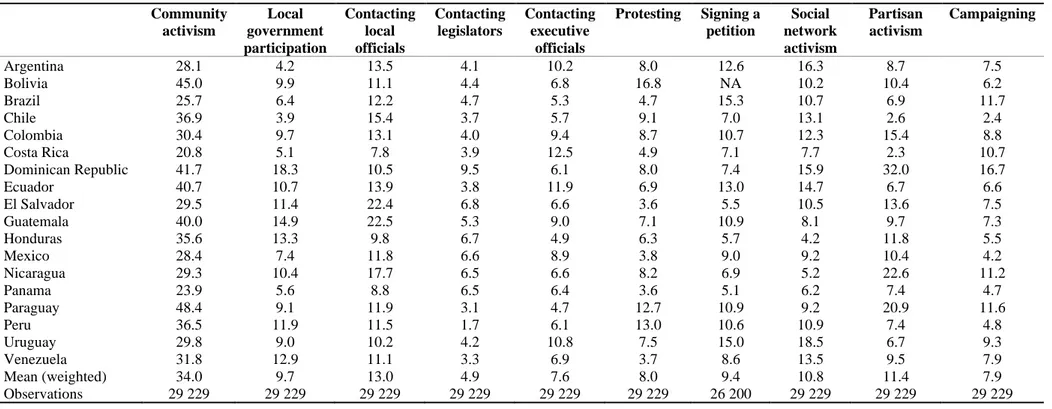

TABLE 3.1 Rates of political participation (2012) 43 TABLE 3.2 Cross-country variation of forms of participation 45

TABLE 3.3 Voting 46

TABLE 3.4 Tetrachoric correlations between forms of participation 49

TABLE 3.5 Factor analysis of forms of participation (rotated factor loadings) 50

TABLE 3.6 Rates of political participation among types 51

TABLE 4.1 Cross-country variation (Pearson’s r coefficients) 58

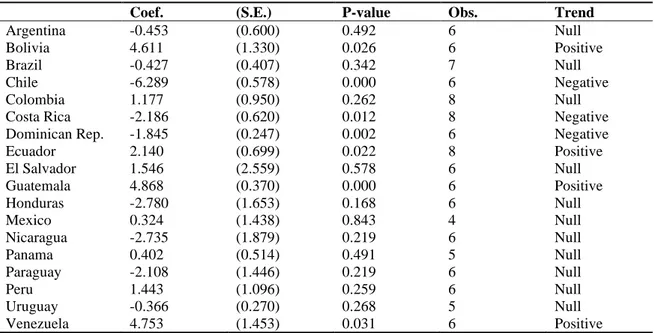

TABLE 4.2 Trends of voter turnout 68

TABLE 4.3 OLS models of average turnout 72

TABLE 4.4 Fixed-effects models of turnout over registered voters 75

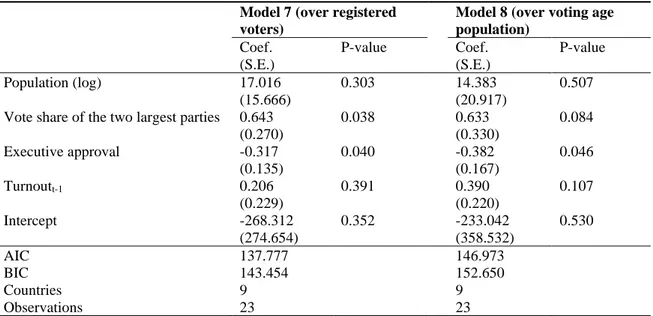

TABLE 4.5 Fixed-effects models of turnout over voting age population 77

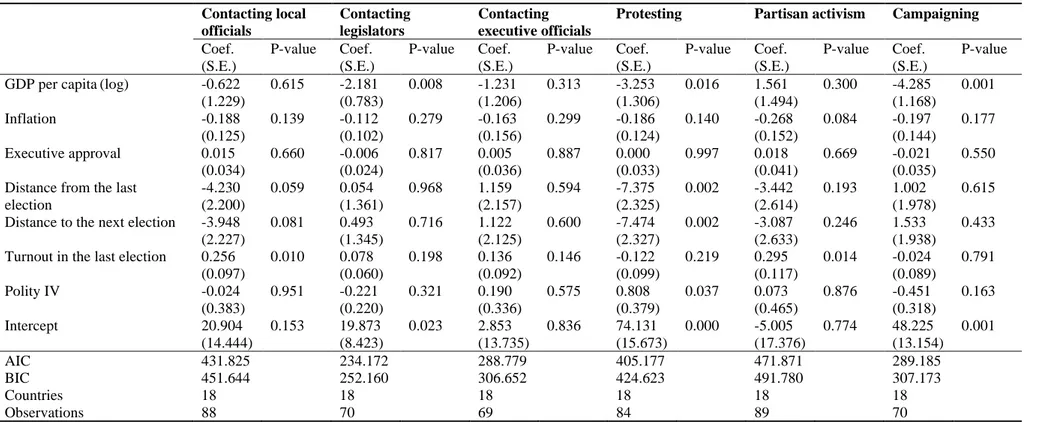

TABLE 4.6 Fixed-effects models of turnout among election with incumbent candidacy 79 TABLE 4.7 Fixed-effects models of rates of other forms of participation 83

TABLE 5.1 Voting as independent variable of voice politics 98

TABLE 5.2 Logistic regression models for voting 101

TABLE 5.3 Multinomial logistic model of political participation (the reference

category is voting only) 105

TABLE 5.4 Comparison of goodness of fit between models 110

TABLE 5.5 Summary of the effects of legitimacy and approval on participation 115

TABLE 6.1 Correlations (Pearson’s r) between participation and governance indicators 128 TABLE 6.2 Effects of participation in governance indicators 131

TABLE 6.3 Ordinal logistic models of life satisfaction 133

TABLE 6.4 Reduction in the odds of being in a higher category of life satisfaction 134

TABLE 7.1 Summary of the main findings 139

TABLE 7.2 Latin American elections in the institutional settings 144 TABLE A.1 Coding of voting rules 153

vi

TABLE B.1 Campaigning (2004-2012) 155

TABLE B.2 Community activism (2004-2012) 155

TABLE B.3 Contacting executive officials (2004-2012) 156

TABLE B.4 Contacting legislators (2004-2012) 156

TABLE B.5 Contacting local officials (2004-2014) 157

TABLE B.6 Local government participation (2004-2014) 157

TABLE B.7 Partisan activism (2004-2014) 158

TABLE B.8 Protesting (2006-2014) 158 TABLE C.1 Definition of variables 159

TABLE E.1 Models of voice politics with voting as independent variable 167

TABLE E.2 Country effects for the voting models 167

TABLE E.3 Country effects for the multinomial model of political participation 168

TABLE E.4 Fixed-effects models of interannual change of the six governance indicators 169

vii

Acknowledgments

This dissertation was written in two very different places: College Station in Texas and Siena, Italy. In both, I met multiple scholars that portray the kind of academic I aspire to become: hard-workers, engaged in interesting topics, careful with methods, but always trying to answer pressing issues in current politics.

First, and foremost, I thank my supervisor, professor Paolo Bellucci. Before even being accepted to the PhD program, I was certain I wanted to work alongside him. It was indeed a good choice. His advice was insightful and honest. He insisted me on paying less attention to the statistical details and more to the substantive topics I was dealing with and the contribution to the field. That guidance is one I will treasure for the rest of my academic career (as well as his recipe of pasta alla sorrentina).

I thank the two reviewers of this dissertation, professors John Bartle (University of Essex) and Dario Tuorto (Università di Bologna). Their observations help me improve this manuscript considerably.

At the University of Siena, I am deeply thankful to professors Sabrina Cavatorto, Maurizio Cotta, Pierangelo Isernia, and Luca Verzichelli for their useful criticism to this project at the PhD colloquia and for their encouragement during the whole program. With Linda Basile and Rossella Borri I shared multiple conversations about elections, statistical analysis, and Italian politics. For these and many other reasons, my time in Siena (in spite of the usual cold weather) is one I will always remember.

My 6-month period at Texas A&M University was a rewarding experience for which I thank the department head William R. Clark. Some of its amazing scholars offered precious input to my research: George C. Edwards III, Maria Escobar-Lemmon, Paul Kellstedt, and Guy Whitten. But my biggest debt goes to Michelle Taylor-Robinson. Her counsel for this dissertation and for other projects, as well as her friendship, played a role that I cannot overstate.

From the University of Costa Rica, I am in debt to all the people that pushed me to pursue the PhD abroad, specially Gilbert Brenes, Alberto Cortés, Sergio Moya, Juan Manuel

viii Muñoz, Ilka Treminio, and Fernando Zeledón. Ronald Alfaro-Redondo shared with me the much-needed pooled 2012 LAPOP database.

Other people merit recognition for their advice. Mariano Torcal (Universitat Pompeu Fabra) suggested me to delve into the relatively neglected topic of political participation in Latin America. Bernard Grofman (University of California, Irvine) gave me stimulating theoretical and methodological insight. I also acknowledge the permanent encouragement of Jorge Vargas-Cullell (Programa Estado de la Nación) and his always sincere and valued appraisals.

Several institutions are responsible for my doctoral training. I am grateful to the Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna for the scholarship granted. Its staff kindly and quickly assisted me on multiple issues, for which I thank Alessandra Delogu, Valentina Mistretta, and Elisa Zanobini. The University of Costa Rica gave me the opportunity to conclude my postgraduate studies and I thus recognize the support of the Rectorate, the Department of Political Science, the Office of International Affairs and External Cooperation, and the special assistance of Karol Cordero.

I also thank the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) and its major supporters (the United States Agency for International Development, the Inter-American Development Bank, and Vanderbilt University) for making available the survey data that I extensively used in the dissertation.

To my family and friends, thank you for your help and support, in this and in previous steps of my life. My most special recognition, however, goes to my fiancée Disley. Her long-distance love has been a constant motivation during the past three years. And the desire to be together again was a good reason to wrap this thing up!

ix

Abstract

There is a paradox in the behavior of mass public. Most people distrust political institutions and politicians, but only a few participate in public affairs. If people are so dissatisfied with the current political institutions and the incumbent governments, why don’t they express that discontent more through political action? To answer this question, I study political participation in Latin America to understand the correlates at the country level, the determinants at the individual level, and some of the consequences of participation for the polity and the subjective well-being of its citizens. For that purpose, the analyses employ three databases: the 2012 survey of the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP); turnout in Latin America (1990-2019); rates of political participation beyond turnout based on available LAPOP waves (2006-2014).

Firstly, the dissertation reviews the conceptual problems related to the label, definition, and attributes of political participation. At its core, political participation is a set of voluntary acts (not an attitude) performed by citizens located or targeted in the sphere of politics and government. From different theoretical approaches, the studies of participation have focused on voting (at the individual level), turnout (country rates), and participation beyond voting. Although rational and sociological explanations are well grounded, it is possible to examine hypotheses that underscore the political context, that is, the relationship between citizens and the government. I propose that the degree of satisfaction with the incumbent is a reason behind participation, complementing the role of resources, attitudes, and mobilization that make up the Civic Voluntarism Model.

The analysis starts by describing rates of eleven acts of political participation in 18 Latin American countries. A factor analysis uncovers a latent structure of participation composed by three types: contacting politicians, voice politics (protesting, signing a petition, social network activism), and electoral activities (voting, partisan activism, campaigning). This means that the acts of participation are correlated, and that people are more likely to perform acts within each type than across them.

Comparatively, current levels of participation are not correlated with the political trajectories of the Latin American countries but with economic conditions. Turnout is vastly

x determined by the rules of compulsory voting, the party system fragmentation, the size of the population, and – to a lesser extent – by the closeness of the election. Even though the popularity of incumbent governments is unrelated with turnout, when the incumbent president is seeking reelection a lower approval significantly increases participation. Short-term changes in the rates of other forms of participation are influenced by economic adversity, which reduces activism, but not by the electoral cycle or by the level of democracy, except for protesting, which is more common when an election is nearby in time and among higher ranking democracies.

The individual-level analysis models participation as a sequence of choices from voting to doing something else: contacting politicians, voice politics, or both. It results that political context does matter, although resources, attitudes, and mobilization are still powerful predictors. Dissatisfaction with the government (distinguished from political legitimacy) leads to more participation through voice politics. Partisanship, either with the president’s party or with any other party, fosters participation, meaning it works more as an attitude and less as a conditional filter of performance evaluation. Contacting is more of an exceptional activity, being predicted by lower income and unrelated with approval.

A final chapter asks if broader participation improves democratic performance and makes citizens more satisfied with life. On one hand, several tests show there is almost no relationship between rates of participation in Latin America and the democratic performance (as measured by the World Bank’s governance indicators). On the other, participation is negatively correlated with subjective well-being, implying that people who participate are less satisfied with life than those who are inactive. These results debunk several theoretical premises about participation.

The conclusions underline the structural determinants of participation. Resources and political attitudes are powerful predictors of participation. Given the socioeconomic inequalities and the low interest in politics of the majority of the population, participation is scarce and unequal. But dissatisfaction with the incumbent government can push people to participate more, contrasting the effects of the structural barriers. The effects of approval might be even larger if measures on the direction of the participatory acts (for or against the government) were available, bringing the studies of participation to a next frontier.

1

1 Introduction

“What we now see emerging is a notion of democracy that is being steadily stripped of its popular component – easing away from the demos.” Mair (2013: 2)

A PARADOX

Representative democracy is said to be under crisis, according to old and new political analyses (Crozier, Huntington, and Watanuki 1975; Mair 2013; Przeworski 2019; Tormey 2015), and several patterns are symptomatic of this distress. Turnout has declined in many countries (Franklin 2004; Solijonov 2016). Political parties have lost much of their appeal and large quantities of followers (Bartle and Bellucci 2009; Dalton 2000). Trust in politicians and in the main representative institutions – government, parliament, parties – diminished in established democracies (Norris 1999; Pharr, Putnam, and Dalton 2000; van der Meer 2017). Currently, the rise of populist and radical parties signals – and is partially caused by – discontent with mainstream politics (Mény 2019; Mudde 2004).

Empirical evidence from surveys disclaims the crisis of democratic legitimacy as an exaggeration. In 39 old and new democracies, 43 percent of the people are not satisfied with the way democracy works in their country. Dissatisfaction with democratic performance reaches over 70 percent in seven of the surveyed countries and over 50 percent in 16; only in Norway less than 10 percent are dissatisfied citizens.1

Among the European mass opinion, 59 percent do not to trust national governments, 58 percent the parliament, and 77 percent the political parties of their countries. Moreover, while 56 percent are satisfied with the way democracy works in their country, more than a third – 37 percent – feel that their voice is not heard by the government.2 In the United

1 The Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module IV. Available from: www.cses.org 2 Standard Eurobarometer 88. Autumn 2017. Available from:

2 States, one of the oldest democracies in the world, public trust in (federal) government dropped from over 70 percent in 1958 to 20 percent in 2017.3 In the Americas, including

Latin American nations, support for democracy declined from 68 percent in 2004 to 58 in 2017. Furthermore, trust in the main institutions of democratic representation – parties, justice system, and national legislature – is currently lower than in the unelected ones like armed forces and churches (Cohen, Lupu, and Zechmeister 2017).

Along political discontent, many socioeconomic issues aggravate the daily life of people. Poverty, crime, and deficiencies in the provision of many public goods (health care services, education) are among the many complains of ordinary citizens. Economic inequality, meaning that despite wages rising worldwide the wealthiest accumulate higher margin profits that the low-income brackets, is a pressing problem (Piketty 2014; Stiglitz 2012). In solving these issues, the national governments remain the key actors. People expect that the governments that plead for their votes and tax them will also answer their grievances and enhance their welfare and prosperity (Przeworski 2010: 164). But, as proven by the data, much of the public is still largely unsatisfied with governments’ responses.

Elections are the assumed mechanism for rewarding and punishing politicians (Fiorina 1981; Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier 2013; Powell 2000). If the incumbent government is not doing the expected job in solving the problems of the citizens, it might be ousted in the following elections. However, national elections are usually held every four years or so in presidential regimes, where the electoral cycle is fixed. In parliamentary democracies, even if anticipated elections can be called for, elections commonly occur in intervals of several years.

What happens between the elections? How can citizens reward and punish the politicians before it is time to go to the ballot box? Petitions, protests, lobbying, contributions to campaigns, and other forms of political participation beyond voting can influence public policy even more than an election, some argue on “day-by-day basis” (Mueller 1992: 985). And if citizens distrust parties, governments, and parliaments as much as they say, and if they are as dissatisfied with politics as they report to surveyors, political activism and protest between and beyond the elections must be large!

3 Pew Research Center. Available from:

3 Paradoxically, that is not the case. In most countries, the modal form of participation is voting (Norris 2007). Either in Europe, the United States, or in Latin America, more than 70 percent say they voted in the last election (Figure 1.1), but less than 20 percent performed other political act such as contacting, partisan activities (i.e., attending meetings of a political party), signing a petition, and protesting. While most Latin American countries are young democracies, where according to some accounts citizens lack a “civic culture” apt for participation (Almond and Verba 1963), rates of nonelectoral participation are not particularly higher in an old, economically advanced democracy such as the United States. Nor are they particularly different in Europe, where the polities have mixed political trajectories and diverse levels of socioeconomic development. In sum, these data tell that across regions with vast political and cultural differences the rates of political participation, excepting voting, are predominately low.

FIGURE 1.1 Comparative rates of political participation

Source: American National Election Studies (ANES) 2012 Time Series Study; European Social Survey Round 6 (2012); LAPOP 2012 survey.

Even though most people vote in the majority of national elections, it is a fact that turnout has declined in many established democracies – although there is not a consensual

4 explanation of why (see Blais et al. 2004; Blais and Rubenson 2013; Franklin 2004). Analysts have estimated that turnout fell around 10 percentage points, from an average of 78 percent in the 1940s to 66 percent in the 2011-2015 period (Solijonov 2016). While some would quickly blame the new, young democracies, it is in Europe where turnout decline has been steadier, and not just because of post-communist countries that are now holding free and fair elections. For example, in Germany and Italy turnout was above 90 percent in the 1970s, but since 2002 it ranges between 70 percent and 80 percent.4

Has participation beyond voting – campaigning, protesting, and contacting politicians – declined in the last decades as well? The scarcity of reliable cross-national longitudinal data makes it hard to answer it. Even in the United States, perhaps the country with the longest available series of survey data, the facticity of the decay of political participation is disputed (Dalton 2008; Putnam 2000).

One source that covers multiple countries in many different periods of time is the World Values Survey (WVS). Consisting of six waves from 1981 to 2014, these surveys have been applied in around one hundred countries (inconsistently, though, since each wave does not contain the same set of countries). This is perhaps the only source with worldwide measures of political activism in random samples of individuals in a (nonrandom) sample of counties. Notwithstanding the methodological limitations, some useful inferences can be drawn from these data.

Figure 1.2 considers six forms of participation, showing the fluctuations in time according to the WVS. Overall, it is a mixed picture. Signing of petitions has solidly diminished from 40 to 19 percent. Participation in strikes seems to increase in the latest survey from 4 to 8 percent. Involvement in demonstrations rose in the late 1980s to 20 percent and then dropped to 13 percent in the past years. Participation in boycotts oscillates between 6 and 9 percent. Membership to political parties is perplexing. While the number of active party members grew from 2 percent in the 1980s to 4 percent in the most recent years, the number of inactive partisans has increased as well, from 4 to 9 percent.

Two points are clear from the above discussion. First, voting, the most common form of participation, has declined. Second, in most countries, participation beyond voting has consistently involved a minority of the population; even if some forms of participation have

5 become more common, they still comprise a small percentage of the mass public. As the opening quote from Mair (2013) indicates, democracies seem empty, without demos.

FIGURE 1.2 Trends of worldwide political participation beyond voting

Source: World Values Survey (six waves). Inglehart et al (2018).

The absence of widespread political participation is a puzzle that theories of retrospective accountability and modernization do not answer. On one hand, if people are dissatisfied with democracy and its main representative institutions, why don’t they engage more actively in politics? Elections are programed events according to a fixed schedule, not when people want a swift in the direction of government or when are dissatisfied with the policies that are being enacted. So why people don’t they take more advantage of the participatory opportunities between the elections? From the worldwide dissatisfaction we would predict habitual contestation to politicians and the decisions they take or the lack of answer to everyday problems. Instead, there is little participation beyond voting and low turnout in midterm elections (legislative, subnational, European).

Societal changes would also predict more participation than observed. Most societies around the world are now more affluent than before. Although inequalities persist, poverty has reduced and the living standards have risen (United Nations Development Programme 2016). Furthermore, technological advances lowered the costs of information and participation. Nowadays people can easily visit the website of their national congress, search

6 the legislator from their district, and contact him or her the office by email and phone. Social networks offer a new and relatively costless space of discussion and participation. Since we know that resources and socioeconomic status determine political participation, meaning that higher education and income increase the probability of voting and participating (Verba and Nie 1972), with socioeconomic and technological advancement participation should be increasing and spreading, as modernization theories suggest (Barnes et al. 1979; Inglehart 2018; Inglehart and Welzel 2005; Norris 2004). In other words, participation is now easier and less costly. But neither the modernization thesis nor the dissatisfaction assumption account why most people do not participate.

Many years ago, rational theory offered an explanation for the absence of participation. Anthony Downs (1957) sustained that the decision of voting is based on a calculus of costs and benefits. But voting is largely inconsequential since there is a very small probability of casting a decisive vote that will bring the preferred party into government. Costs, albeit reduced, will surpass the almost null benefit of voting. Then, it is rational not to vote unless there is an external motivation such duty (see Riker and Ordeshook 1968). That explanation extends to other forms of participation (Downs 1957: 253-257). Protesting and contacting politicians might be more consequential than a single vote into translating demands to outcomes, but the costs are significantly higher. The resulting participation is irrational for most.

Rational accounts are good at explaining why people do not participate: because it is costly and thus not rational. Besides voting, most people do not participate even though they are unsatisfied; these are called passive or “standby” citizens (Amnå and Ekman 2014). But Figures 1.1 and 1.2 proved that some people do participate.

In brief, some theories predict increasing participation as a consequence of environmental changes and citizen dissatisfaction. Others predict less, as an equilibrium of a benefit-cost calculus. This implies that there is something missing in our theoretical understanding of participation and that empirical studies may offer valuable evidence in that regard. Accordingly, this dissertation contributes to the general explanations of political participation, electoral and beyond, at the macro and micro levels of analysis. The main argument is that participation depends not only on structural conditions (resources, attitudes) but also on political context, here defined as the relationship between citizens and the government and measured through variables such as approval, issue performance, and

7 partisanship. The hypotheses are tested with data from Latin American countries, but the implications are theoretically oriented and not constrained by the context. But first, let me underscore the importance of participation as a topic in both empirical and normative theories of democracy.

PARTICIPATION AND DEMOCRACY

Participation is a fundamental element of modern democracies (Dahl 1971, 1989). The democratic ideals of liberty and freedom are the basis in which participation is founded (Bobbio 1995). And the rights, freedoms, and opportunities to participate are taken as requisites of procedural democracies. However, while there is a theoretical relationship that links participation and democracy, the degree of the desired participation varies among different conceptions of democracy.

Minimalist perspectives emphasize the competition between elites (Schumpeter 1950) and the possibility of removing the rulers by means of elections (Przeworski 2010). For them, participation is enfranchisement or the opportunity to participate, or a political right, not caring if it is actually exercised. A democracy with low turnout is the same as another one with high turnout, as long as it fulfills the institutional requirements of free and fair competition, and inclusiveness of the adult population.5 Furthermore, this view of participation is limited to voting because, as Przeworski (2010: 162) argues, “representative institutions were designed to bar or at least to minimize the voice of the people between elections”.

Conversely, other theorists contend that democracy continuously enhances freedom and active involvement in the polity (O’Donnell 2010; Touraine 2000) as in other social-economic spheres (Pateman 1970). In other words, higher and more diverse participation leads to a stronger and more vivid democracy. Scholars focused on the quality of democracy have set participation as a criterion of a good democracy, one that “must ensure that all citizens are in fact able to make use of these formal rights to influence the decision-making process: to vote, to organize, to assemble, to protest, and to lobby for their interests” (Diamond and Morlino 2004: 23). That is, while democratization is achieved when vote becomes a reality, a high-quality democracy demands broader participation beyond voting:

5 Among minimalists, the exception is Vanhanen (2000), who includes the turnout percentage as one of the

8 protesting, partisan activities, contacting. It does not matter if there is compulsory vote or not, as long as a large population participates and makes democratic governments responsive (Altman and Pérez-Liñán 2002: 88). Otherwise, the democratic regime is downgraded to a “delegative democracy” where citizens passively authorize governments to take the political decisions, limiting participation to voting in elections (O’Donnell 1994). Along this line of thought, several academics, politicians, and civil society organizations have championed deliberative democracy (e.g., Dryzek et al. 2019; Fishkin and Luskin 2005) and the implementation of instruments of direct democracy within the existing representative democracies as ways of enhancing participation. Referenda, plebiscites, popular initiatives, and participatory budgeting are among the most common mechanisms of direct democracy (see Altman 2011). Their application and impact are not negligible. People have solved consequential issues through referenda in many countries: the form of government (presidentialism vs. parliamentarism) in Brazil, the peace agreement between the government and the guerrillas in Colombia, the divorce law in Italy, and the membership to the European Union, just to mention a few prominent cases.

A third theoretical approach champions not just the addition of tools of direct democracy but the replacement of representative institutions with participatory democracy (Sartori 2003b). This constitutes a completely different institutional arrangement that is deemed unfeasible in modern states given the magnitude of the territories and the size of the populations (Dahl 1989). Evidently, this perspective expands political participation well beyond the levels of representative democracies.

TABLE 1.1 The role of participation according to perspectives of democracy

Minimalists Expanded democracy Participatory democracy

Participation limited to voting Voting and instruments of direct democracy

Participation replaces representation

Source: Author’s elaboration.

Table 1.1. summarizes these three visions of democracy and the expected participation within each. There is an increasing emphasis on participation as one moves from the left to the right of the table. And while no participatory democracy exists, some current political movements are demanding a more active inclusion of the people in the political process.

9 Populist parties that antagonize the elites also criticize the representative institutions that regulate the relationships between the citizens and the government (see Mény 2019). Accordingly, institutional innovations that bypass party politics by adopting direct democracy institutions have become the flagship of many populist leaders. For example, in “Rousseau”, the web platform of the Italian Movimento Cinque Stelle (Five Star Movement), partisans can vote, express opinions, select candidates, and propose legislative bills (see https://rousseau.movimento5stelle.it/rousseau.php). In Latin America, where the populist tradition has been historically strong, leaders like Hugo Chávez and Evo Morales have embraced an “inclusionary” version of populism that favors the representation of politically excluded groups and the adoption of tools of direct democracy such as referenda and communal councils (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser 2013).

This research focuses not in the innovative channels of direct democracy but in the opportunities of participation that exist in all democracies. The reason is that direct democracy requires the institutional provisions that exist in some but not in all countries. For example, not all constitutions permit the application of referendum. In that sense, citizens’ participation depends first and foremost on the external conditions. Instead, here I study participation as a voluntary act, independent of these institutional provisions. In all democratic countries people can contact politicians, protest, sign petitions, and – obviously – vote. Understanding why people do and do not participate through the existing channels, or why variations in the forms of participation between individuals exist, seems a necessary first step before examining the involvement through the institutions of direct participation. Although the forms of political participation here conceived do not require special institutional arrangements, access to participation is limited by other structural conditions. Theories of democracy normatively state that participation should be granted, but from vast empirical research we know that participation is unequal (Lijphart 1997; Smets and van Ham 2013; Verba and Nie 1972; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995). Acting as “factual” inequalities (Bobbio 1995), resources – both material like income and cognitive like education – condition and determine political participation.

Previous studies on the inequality of participation, however, have focused predominantly on developed countries, with comparatively higher gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and quality of life. What happens in countries like the Latin American ones? Are the structural determinants powerful predictors of participation as in industrialized Western

10 democracies? While it cannot be assumed that higher participation leads to more democracy, a more equal access to participation seems to be a desirable condition and a relevant topic to analyze. Since Latin America is a region with high income inequalities (see below), the role of resources as informal barriers of participation cannot be underplayed. Even so, other factors that foster participation, like dissatisfaction with incumbent governments, may offset these effects by pushing citizens against the policy decisions (or lack of). Thus, it will necessary to assess the marginal impact of each variable through statistical modeling. The interplay between resources, political attitudes, and institutions is to be essential when explaining political participation.

Another problem related to the linkage between participation and democracy is that of what do the levels of political involvement say about the acceptance of the democratic system, or its legitimacy. For example, extended protests and social mobilizations may suggest disconformity with policies, politicians, and the political system. But they could also imply that people are satisfied with the openness of the regime, which is allowing them to express disconformity with the government’s outcomes. Looking at the separate effects of satisfaction with the democratic regime, on one hand, and the approval of the rulers, on the other, is one of the main tasks of the present research, one that has been overlooked because of the muddy conceptual differences between legitimacy, trust, approval, and support (see Torcal 2014; van der Meer 2017).

Finally, the different conceptions of democracy outlined above expect varying degrees of participation and possible consequences. Research in the culturalist tradition (e.g., Almond and Verba 1963; Putnam 1993), as do populist movements and parties, believe more participation would improve the polity and the well-being of the population. Conservative thinkers and supporters of technocracy advice that participation must be curtailed to avoid overloading of “irrational” demands. Compared with the research on the causes of participation, the consequences have been less studied. This research wants to contribute to the academic and political debate about how much participation is desirable and which vision of democracy and its consequences is backed by data.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The research focuses on Latin America, for reasons that will be explained in the next section. Meanwhile, it is enough to say that there is much to gain in the study of political

11 participation by moving beyond the United States and Western Europe, where theories of political behavior have been developed and tested. A comparative design, one that includes multiple countries and individuals, is appropriate to test macro and micro explanations of political participation.

Discussing research design, Barbara Geddes (2003) advises scholars in comparative politics to avoid building big questions that were prone to become theoretical “sandcastles” and suggested breaking them up into more specific questions. Accordingly, rather than simply asking “What causes political participation?”, this research proposes more detailed questions taking into account two levels of analysis: (1) What is the latent structure of participation in the behavior of Latin American citizens? (2) Which country-level characteristics account for the cross-national variation of turnout and other forms of participation in Latin America? (3) Which individual-level variables explain types of political participation? (5) What are the consequences of political participation for the democratic performance and well-being of its citizens?

CASE SELECTION AND CONTEXT

This research focuses on Latin America and there are several reasons why this region is interesting and useful for the study of participation.

Democracy is usually a scope condition in the study of political behavior, not least of voluntary political participation, and most Latin American countries in the twenty-first century are democratic, consenting the study of political behavior in the region. Furthermore, in spite of setbacks in particular cases, democracy has endured in the 18 countries for an acceptable amount of time.

When democratic stability was reached in Latin America, scholarship started examining if theories and hypotheses built elsewhere are valid for the region. The answer has been predominantly positive. Nadeau et al. stated that the Michigan’s funnel of causality model “does a good job explaining individual-level vote intention in Latin America, behaving as one would expect” (2017: 137). Carlin, Singer, and Zechmeister concluded The Latin American Voter declaring that “results imply that the average Latin American voter bears a resemblance to the average voter in places such as the United States and Europe” and “classic models travel fairly well to this very different region” (2015: 350). These past works, however, focused on turnout and voting choice, neglecting other forms of

12 accountability and expression of citizens’ preference. Thus, my research wants to ascertain how well do models of political participation travel to Latin American countries.

A second reason for studying Latin American countries is the intra-regional variation. Sometimes, when speaking about Latin America, there is the underlying assumption of homogeneity. The cultural and historical similarities (Spanish and Portuguese colonization) are an outstanding fact. The predominance of presidentialism is another.6 Nonetheless, there are vast differences in the development of democratic institutions, with potential implications for the development and stability of patterns of participation.

After independence from colonial rule, Latin American countries struggled for decades to achieve fair electoral competition and full democratic regimes (Drake 2009). At the midst of the twentieth century, only three countries were democratic: Colombia, Costa Rica, and Venezuela. In all these cases, compromises between elites on the aftermath of violent conflicts were followed by party alternation in government, respectful of the electoral rules. In Colombia, the Frente National (National Front) of 1957 between the Conservative and Liberal parties overthrew the incumbent dictator and established a power-sharing “consociational” arrangement that lasted until 1974, when full competitive elections were resumed (Dix 1980). In Costa Rica, the military junta composed by the winners of the civil war of 1948 (regrouped in the Partido Liberación Nacional, National Liberation Party) gave up its power after a few months and abolished the army, but at the same time proscribed the communist party and exiled the political competitors. Through not exactly the result of a “pact among elites”, Costa Rica’s democratic consolidation was achieved when the winning coalition accepted electoral defeat in 1958 (Bowman 2000). In Venezuela, the three largest parties, Acción Democrática (Democratic Action), Comité de Organización Política Electoral Independiente or COPEI (Independent Political Electoral Organization Committee), and Unión Republicana Democrática (Democratic Republican Union), along with the business leaders, agreed in 1958 to organize elections and respect the results through the Pacto de Puntofijo, which produced multiparty governments and alternation until the 1990s (Coppedge 1994).

In the rest of the countries, democracy was less promising. In the context of the Cold War, personalistic and military dictatorships (many with U.S. support) were established in the

6 Strict institutional definitions place Peru as a case of semipresidentialism, where there is both a popularly

13 50s and 60s. These autocratic regimes committed innumerable human right violations, as illustrated by the infamous cases of Augusto Pinochet in Chile, Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, and various military leaders in Argentina, Brazil, El Salvador, and Guatemala, among others.

The 1970s gave way to a new era of democratic transition in what is to be known as the third wave of democratization (Huntington 1991). Starting with the Dominican Republic in 1978, most Latin American dictatorships transitioned to democracy; only Cuba and Haiti remained autocratic. This regional wave of democratization was a result of political, ideological, and international shifts (Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán 2013). Radicalism decreased, while normative preference and commitment to democracy grew (i.e., acceptance of democracy notwithstanding its policy outcomes). At the same time, the regional environment became more favorable for democracy. International organizations, such as the Organization of American States (OAS), and a renewed U.S. foreign policy endorsed democracy and pro-democratic ideas.

Although the spread of democracy in the region is unprecedented, some setbacks have taken place. In 1992 president Alberto Fujimori organized an “auto-coup” against the Peruvian Congress. In 2009 militaries deposed the president of Honduras, Manuel Zelaya. Currently, in 2019, Daniel Ortega’s Nicaragua and Nicolás Maduro’s Venezuela are counted as dictatorships. Despite the internal opposition and international condemnation, it unclear whether and when democratic competition could resume in these two countries.

This study focuses on 2012, which is a proper time to study participation because most countries were democracies at the time. Table 1.2 tabulates the first year of the latest competitive regime (transition to democracy or semidemocracy), not counting the breakdowns in Honduras (2009) and Peru (1992) or erosions from democracy to semidemocracy (following the terminology of Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán 2013). The third column shows the Polity IV score in 2012. Polity IV scale ranges from -10 (autocracy) to 10 (full democracy). A value of 5 or higher is often assumed to indicate a democracy. Seventeen of the 18 countries surpass this threshold, Venezuela being the only country sampled with a negative score in 2012, which sets it within the range of a hybrid regime, or a competitive authoritarian regime (Levitsky and Way 2010).

14

TABLE 1.2 Cases selected

Transition to democracy (semidemocracy) Polity IV score in 2012

North America Mexico 2000 (1988) 8 Central America Costa Rica 1953 (1949) 10 Dominican Republic 1978 8 El Salvador 1994 (1984) 8 Guatemala 2000 (1986) 8 Honduras 1999 (1982) 7 Nicaragua 1990 (1984) 9 Panama 1994 (1990) 9 South America Argentina 1983 8 Bolivia 1982 7 Brazil 1985 8 Chile 1990 10 Colombia (1958) 7 Ecuador 1979 5 Paraguay 2008 (1989) 8 Peru 1980 9 Uruguay 1985 10 Venezuela 1959 -3

Source: Years of transition from Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán (2013). Polity IV scores available from:

http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html

Another reason to study Latin America is the fact that, despite most countries successfully transitioned to democracy, the region is not without political, social, and economic challenges. Politically, besides the mentioned democratic regressions in Nicaragua and Venezuela, plenty countries in the region struggle against a trend of “soft authoritarianism”, strong leaders, and populism, that was initially identified with the left (Seligson 2007; Weyland 2013). Leftist-populist leaders rose to power in the 2000s in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Uruguay, and Venezuela, nurtured by optimistic economic evaluations and anti-U.S. sentiments among public opinion (Remmer 2012). Even so, other scholars acknowledged the prospect of a conservative backlash (Luna and Rovira Kaltwasser 2014), which has proven true with the subsequent electoral successes of right-wing candidates Mauricio Macri in Argentina, Sebastián Piñeira in Chile, Iván Duque in Colombia, Jimmy Morales and Alejandro Giammetti in Guatemala, and Mario Abdo in Paraguay, among others. Far-right populism has succeeded in Brazil with Jair Bolsonaro. In Costa Rica, an evangelical, populist far-right party advanced to the 2018 presidential runoff, ultimately losing the presidency but gaining 14 seats of the 57-member parliament. This conservative comeback can be explained by poor economic performance of former governments,

15 dissatisfaction with traditional parties, and socioeconomic anxiety due to relative deprivation among middle classes (Murillo 2019).

Additionally, numerous impeachments and resignations manifest a new kind of political instability (Pérez-Liñán 2007). Although not producing democratic breakdowns like in the twentieth century, since vice presidents ordinarily assume the reins of government and maintain the stability of the regime, these interruptions imply that the political systems are not solving conflict through the normal institutional channels within the branches of government. Overall, the complex combination of soft authoritarianism, populism, cycles of ideological change, and institutional instability adds an interesting layer to the political landscape of the Latin American countries.

Economically, there are plenty of challenges in Latin America. The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL 2013: 77) reports that, during the past three decades, most of the population in the region have lived in a context of slow economic growth of less than 2 percent of the interannual GDP change. While there are variations between countries, Latin America as a whole has a GDP per capita that is below the 30 percent of the one in the United States. The 1990s were a decade especially harsh because of high unemployment, inflation, and income inequality (CEPAL 2013: 79-80). From 2000 there has been improvements. Inflation reduced. Poverty rates significantly dropped from 40.5 percent in 1980 to 29.4 percent in 2011 (CEPAL 2012: 17). Even so, almost a third of the population are still poor. In some countries – Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Paraguay – the rates of poverty surpass 50 percent, and other gaps can be found across sociodemographic groups (e.g., in rural areas, in lower education strata) (CEPAL 2012: 18-19). Regarding income, Latin America is one of the most unequal regions in the world. Overall, the wealthiest 10 percent in the region receives the 32 percent of the income, and the poorest 40 percent gets the 15 percent. Although diminishing in many countries, inequality is still particularly high in Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica and Guatemala (CEPAL 2012: 23).

If dissatisfaction with government performance leads to more participation, as theoretically proposed, Latin America presents proper conditions to test the hypothesis. There are political and economic difficulties, with variations between countries, that may relate to different intensities and forms of political participation.

16 A final advantage of studying Latin America is the novel availability of survey data for the period of analysis, as explained in the section that follows.

DATA AND MEASUREMENT

This work employs three databases. The main source is the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) of the University of Vanderbilt, specially its 2012 survey. LAPOP conducts face-to-face surveys in the region since 2004. Similar sampling designs and questionnaires make data highly comparable between countries. And, most importantly, although their studies cover a great variety of topics, the 2012 wave included a battery of more than ten items of political participation.

In these surveys, the covered population is voting age adults. Samples were chosen using a multistage design where countries were stratified by regions, size of municipality, and urban and rural areas within municipalities, with quotas applied at the household level. In each household, surveyors interviewed only one respondent (see more details in LAPOP 2012). LAPOP conducts the fieldwork in similar dates for all countries, between January and May 2012 (Table 1.3). Collecting data in the same period implies benefits and setbacks. We gain comparability and in the presence of global or regional phenomena all countries are affected (although shocks may not have a uniform impact on all countries). On the negative side, Latin American countries – as any other sample of countries – do not have their electoral cycles synchronized. Accordingly, there are unequal intervals between the time of the last election and the dates of the survey’s fieldwork. In some cases, there are six-year lapses between them. The macro-level analysis will examine if time between elections have some impact on nonelectoral participation.

As said earlier, the 2012 wave is abundant on items of political participation. There are eleven closed-ended questions covering diverse forms of participation (Table 1.4; see also Appendixes C and D for details). Variables refer to community activism and local participation, contact with politicians in three levels of government, protesting, signing petitions, social network activism in Twitter, Facebook or Orkut,7 attending meeting of political parties or political organizations, campaigning during electoral campaigns, and voting in the last elections. Some of these questions have been asked before and after the

17 2012, but only once they were all pooled together. Social network activism was never asked again, for instance. This makes the 2012 survey the most comprehensive source of political participation. Fortunately, the questions are spread across the questionnaire, reducing the potential biases from respondents’ acquiescence and framing effects due to the proximity of items, as would happen with a single battery of participatory acts.

TABLE 1.3 Technical information of the 2012 LAPOP survey

Country Start date End date Sample Year Last presidential election

Argentina March 3 April 4 1512 2012 2011

Bolivia March 3 April 22 3029 2012 2009

Brazil March 1 April 18 1500 2012 2010

Chile March 30 May 1 1571 2012 2009

Colombia March 1 April 20 1512 2012 2010

Costa Rica January 28 February 29 1498 2012 2010

Dominican Republic January 15 February 15 1512 2012 2008

Ecuador February 4 February 12 1500 2012 2009

El Salvador April 18 May 12 1497 2012 2009

Guatemala March 7 April 5 1509 2012 2011

Honduras January 27 February 17 1728 2012 2009

Mexico January 25 February 19 1560 2012 2006

Nicaragua February 4 March 1 1686 2012 2011

Panama January 23 March 17 1620 2012 2009

Paraguay February 1 February 28 1510 2012 2008

Peru January 20 February 10 1500 2012 2011

Uruguay March 1 March 30 1512 2012 2009

Venezuela February 28 March 29 1500 2012 2006

Source: LAPOP (2012).

One issue with the questionnaire is that the time frame in the items is not the same. Community activism, local participation, protesting, signing petitions, and social network activism register activism in the last 12 months. Campaigning and voting refer to the last election (which changes from one country to another). Contacting and partisan activism do not present a time frame. This inconsistency posits additional considerations in the analysis of Chapter 5. Notwithstanding its pitfalls, this dataset offers an invaluable source for the study of different forms of participation in comparative perspective.

The empirical analysis is not based solely on the 2012 survey. A second dataset is an original compilation of turnout rates in the region, covering from 1990 to the beginning of 2019 (the presidential election of February 3rd in El Salvador). The database considers 111 first or only round presidential elections, with turnout calculated over the registered electors and the voting age population. Relying on official figures published by the national electoral government bodies or the ministries in charge of the elections presumably guarantees higher

18 quality of the data, rather than blindly trusting compilations of other authors and research institutions (such as International IDEA). These turnout rates are analyzed in Chapter 4.

TABLE 1.4 Items of political participation included in the 2012 LAPOP survey

Source: LAPOP’s 2012 questionnaire available at https://www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/core-surveys.php

Lastly, I built a third database by merging the aggregate rates of nonelectoral participation, that is, the forms of political participation of the individual analysis explained before and shown in Table 1.4. This 18-country panel dataset, although with a limited time span between 2006 and 2014, is a unique source of information of how political participation – beyond turnout – changes in time and across countries. As with the turnout database, the rates of political participation constitute a dependent variable that can be tested against explanations based on political context and economic conditions, dynamically.

STRUCTURE OF THE DISSERTATION

The following Chapter 2 summarizes the conceptual and theoretical perspectives of political participation among three branches of the literature: voting as an individual action, turnout as an aggregate, and participation beyond voting. There is significant distinction in the literature between subfields. Research on electoral participation – at the country and individual levels of analysis – is well-structured, deriving from the easily defined political

Variable Question

Community activism In the last 12 months have you tried to help to solve a problem in your community or in your neighborhood?

Local government participation Have you attended a town meeting, city council meeting or other meeting in the past 12 months?

Contacting local officials In order to solve your problems have you ever requested help or cooperation from a local public official or local government? Contacting legislators In order to solve your problems have you ever requested help or

cooperation from a member of congress/parliament?

Contacting executive officials In order to solve your problems have you ever requested help or cooperation from any ministry or minister (federal), state agency or public institution?

Protesting In the last 12 months, have you participated in a demonstration or protest march?

Signing a petition In the last 12 months have you signed any petition? Social network activism And in the last 12 months, have you read or shared political

information through any social network website such as Twitter or Facebook or Orkut?

Partisan activism Please tell me if you attend their meetings of a political party or political organization

Campaigning There are people who work for some party or candidate during electoral campaigns. Did you work for any candidate or party in the last presidential elections?

19 act of voting. The study of other forms of participation is conceptually messier. There is no uniformly accepted definition of participation and the acts it comprises. Thus, researchers not unfrequently cluster forms of participation without strict conceptual guidance, sometimes combining acts with attitudes with damaging consequences for the empirical findings. Others simply add forms of participation in one overall measure that hides behavioral variations. One objective of this dissertation is to overcome these problems by providing a novel operationalization of political participation based on the actual behavior. Chapter 3 describes the rates and patterns of political participation in Latin America. A factor analysis shows how participation acts are correlated are reduced into three types: electoral (voting, partisan activism, and campaigning), contacting politicians (local officials, legislators, and executive officials), and voice politics (protesting, signing petitions, and web activism). I sustain that this distinction is both conceptually accurate, because taps actions (not attitudes) related with politics and public sphere, and empirically grounded, since is based on data of what people do. This typology of participation defines the dependent variables of following chapters.

Taking a step back from the survey data, Chapter 4 explores some macro-level explanations, using both official figures of voting and aggregate rates of other forms of participation gathered by various survey waves. Turnout is highly influenced by the party system and rules of mandatory voting, even if taken in a purely formal way based on the written rules (constitutions, electoral laws). Instead, the economy, while related to voting choice, is not associated with the rates of participation at the ballot box. Interestingly, an analysis of a subset of elections finds that government approval has an impact on turnout only when the incumbent president is a candidate. This conditioned effect of popularity on turnout in Latin America is one that, to the best of my knowledge, has not been tested before. The same chapter shows that modeling other forms of participation at the aggregate level is a mystery box. The scarce variance between countries and across time is challenging and, as a result, only few covariates seem to be systematically related.

Chapter 5 deals with explanations of political participation at the individual level. This analysis picks up the uncovered structure of political participation from Chapter 3 in order to define the operationalization the dependent variable. Participation is assumed as a sequential decisional process that goes from voting (which a majority does) to doing something else: contacting politicians, voice politics, or both. The chapter models these

20 choices – voting and participation beyond voting – using two main theoretical perspectives: a sociological approach (or Civic Voluntarism Model) and a political-context explanation based on governmental approval, performance on different economic and noneconomic issues, and partisanship. I find that although resources and political engagement attitudes are powerful explanatory factors, the evaluation of the government has independent effects on some forms of participation, mainly, on voice politics.

Finally, Chapter 6 looks at some of the consequences of political participation both at the country and individual levels. Although more participation theoretically does not make a regime more democratic, several authors have argued that citizen involvement could improve the performance of the democratic regime. In other words, participation can make a better democracy. The chapter argues that political activism could also enhance the subjective well-being of people. The empirical findings, however, contradict most assumptions. Participation does not seem to improve democratic governance – but neither to damage it. And people that participate in politics are less satisfied with life, even when controlling for a wide set of subjective well-being predictors.

In the Conclusions I try to make sense of the universe of results, from the determinants of participation to the unexpected consequences, their implications for democracy, and the challenges for future research, emphasizing the ways in which questionnaire-building can eventually improve the analysis of participation.

METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES

The methodological realm in political science is vast and sometimes controversial. For this reason, it seems useful to clarify some of the methodological choices that were taken in this dissertation.

As noted in the research questions and the outline of the chapters, there are two levels of analysis: macro comparisons between countries, sometimes including a time dimension, and micro analysis of individuals through surveys. The differences between both are substantial and technically relevant. Country-level data are not randomly selected. Being an area study, the sample of Latin American countries is determined by geographic, historical, and political criteria (see Ahram 2011). The individual-level data, instead, come from randomly selected samples within each country that allow valid generalizations to the respective populations.

21 The distinctive nature of the data entails consequences for the possible inferences. In the macro analysis, I refrain from using tests of significance that assume random samples when calculating correlations at the country level. Furthermore, with 18 observations (countries), the statistical power is limited. Instead, Pearson’s r coefficient gives the magnitude of the correlation, without needing far-fetched assumptions about how countries could be randomly drawn from a larger population. Graphs complement this analysis.

Yet there is an evident drawback: because of the sample size, the analysis between countries forbids the inclusion of controls. The macro level analysis based on 18 cases, while suggestive, is descriptive and exploratory. In order to gain leverage when dealing with small samples, King, Keohane and Verba (1994) suggested collecting more data points in time; that is, transforming a cross-section into a panel structure. This is feasible up to some limit. Because the proposed typology of political participation in Chapter 3 uses a battery available only in the 2012 survey, some analyses are deemed to be static. For example, the factor analysis that uncovers the latent dimensions of participation is possible only for one year. In other cases, the conceptual consistency is loosened in order to build panel datasets from the raw percentages (not types) available in years other than 2012. This allows modeling of rates of participation between countries and in time. Since countries are a nonstochastic population, and the number of countries (N) is larger than the time points (T), fixed effects are the proper model for this panel design (see Hsiao 2003). A fixed-effects model takes the following general form,

𝑦𝑖𝑡 = 𝛼𝑖+ 𝜷′𝒙𝑖𝑡+ 𝑢𝑖𝑡

where 𝑦𝑖𝑡 is the dependent variable for each country 𝑖 in time 𝑡, 𝛼𝑖 is a unit-varying intercept,

𝜷′ is a vector of regression coefficients, 𝒙𝑖𝑡 is a vector of exogeneous variables and 𝑢𝑖𝑡 is an

independently identically distributed error that is uncorrelated with the independent variables. The parameters can be estimated using ordinary least squares.

When analyzing individual level data, the heterogeneity between countries must be taken into account. For that purpose, multilevel modeling is a popular and attractive tool not only because it deals with the country-specific heterogeneity but also because it allows the inclusion of macro-level variables (e.g., GDP, voting rules) at the country level. However, with 18 countries the second-level sample is again too small to provide reliable estimates of the random effects and the variance components (Bryan and Jenkins 2016; Stegmueller 2013). An alternative to multilevel regression is to include country dummies to account for

22 the cross-country variation. Thus, the individual-level coefficients can be safely estimated without relying on country-level coefficients that are prone to bias.

Estimating regressions with country dummies is the strategy adopted in the dissertation. Hence, there is a multilevel analysis although no multilevel (mixed effects) estimation. The macro analysis focuses on the variations between countries; the micro on the individuals. And while there is no variance decomposition between level 1 (individuals) and level 2 (countries), the results from both approaches can “speak” to each other and find substantive and theoretical communalities, which are discussed at length in the Conclusions.

Finally, it is important to disclaim that when performing significance tests, I report the associated P-values, instead of marking significant results with stars or similar symbols. The former seems to be a more transparent way of pondering the evidence for the null hypothesis. While the 0.05 is the usual threshold for statistical significance, readers can assess the results through other preferred level of their choice.

23

2 The State of the Literature

on Political Participation

DEFINING PARTICIPATION

Before answering what explains participation, the chapter must clarify what we understand by the concept of political participation. Voting can be easily defined: casting a vote, whatever the ballot structure or the electoral system are. Turnout is unequivocally assumed as the aggregate-level participation in an election. And because most of us have voted in national, local, and supranational elections (e.g., the European parliament), or at least seen news about them, voting can be mentally associated with a booth, a ticket, and a queue, even for people that have not voted. But what about signing a petition? Partisan activism? Protesting? These not only are more difficult to conceptualize but are also less familiar to the average citizen.

The literature on political participation reveals problems in the four constitutive elements of a concept (Gerring 2012: 116): the term (label), the attributes (definition), the phenomena (referents), and the indicators.

First, scholars have created a manifold of terms when referring to participatory acts. Political action (Barnes et al. 1979), political activism (Norris 2007), political engagement (Carreras 2016; Vaccari 2017), and civic engagement (Pattie, Seyd, and Whiteley 2003) are some of them. What these terms stand for is not always intuitive. While “activism” might be interpreted as protest behavior, “engagement” could be confused with certain political attitudes, such as attentiveness and interest in politics (Ekman and Amnå 2012), becoming especially problematic when the latter are considered explanatory factors of participation, as in the Civic Voluntarism Model (Verba et al. 1995). My research uniformly adopts the label of political participation, although not ignoring the scholarship that called it by another name, because “participation” points more to actions than to attitudes and orientations. I believe that researchers of participation should start using terms more consistently, a feat that has been accomplished in many other fields of political science.