1

Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia Department of Archaeology

Architecture In The Melkite Icons In Syria From Middle Of

The Seventeenth Until The Beginnings Of The Nineteenth

Centuries

Dottorato di Ricerca in Archeologia Curriculum Orientale

XXX Ciclo

Supervisore Dottrando Prof.ssa F. Pinnock Rand abou Ackl

Roma

2017-2018

2

3 Acknowledgments

First and foremost, I am deeply and sincerely grateful to Prof. Frances Pinnock, my supervisor for her invaluable advice and counsel, her unfailing willingness to put aside her own work at any time to discuss my problems. Without her constant help and support, this book would never have been completed.

Photographs have been received from many sources and are duly acknowledged. However, I am particularly grateful to those in charge of “DGAM” Directorate-General of Antiquities Museums in Syria.

I will thank my family for continually taking me back to what the life is really worth! Dad Fouad, Mom Nazira, my lovely twin sister Rama, and last, not least big thanks goes to my brother Raja.

During the preparation of this dissertation, I received the help of a number of people, and friends without which the dissertation might have been even longer in preparation or possibly not finished at all, and it is a pleasant task to acknowledge their contributions. A number of my friends and colleagues have read parts of the manuscript at various times and made useful and helpful suggestions; Hicham Al Saiegh, Helen Al Moustafa, Mohammad Al Khalid. And I thank my friends who have supported me; Yara Al Hadadd, Adon Mansour.

Despite all this assistance, I am certain that errors are still to be found in this dissertation. Needless to say, for all errors of omission and commission, the author remains solely responsible.

4 Table of figure:

Figure 1 Akathist icon, Yussef al-Mussawir, 1667, 48x 58, Museum of Sursock, Lebanon. . 58

Figure 2 The scheme of Annunciation icon, John of Damascus church, Damascus, 1865, 51.7x67.6cm, Ne’met Nasser Homsi. ... 72

Figure3. The scheme of Annunciation, Beautiful Great, Sydnaia, George Monastery, Joseph Elian. ... 72

Figure 4 The scheme of Dormition of the Virgin icon, Sydnaia, 17th. ... 76

Figure 5 The scheme of Crucifixion icon, 1708, cat.44... 78

Figure 6 Scheme of Jerusalem city, the Ascension icon, 1718, Aleppo, cat.25. ... 80

Figure 7 Scheme of presentation (meeting) icon, Aleppo, 1714, cat.7. ... 82

Figure 8 The scheme of The Entry to Jerusalem, 1685, Latakia, Cat.19 ... 83

Figure 10 the Scene 8; The Magi see the divinely moving star, Akathist, Aleppo, 1714. ... 84

Figure 9 the arched door of the Dormition church, Aleppo. (Ward, 2017) ... 84

Figure 11 The scheme of Sydnaia proskynetaria. Cat.64. ... 90

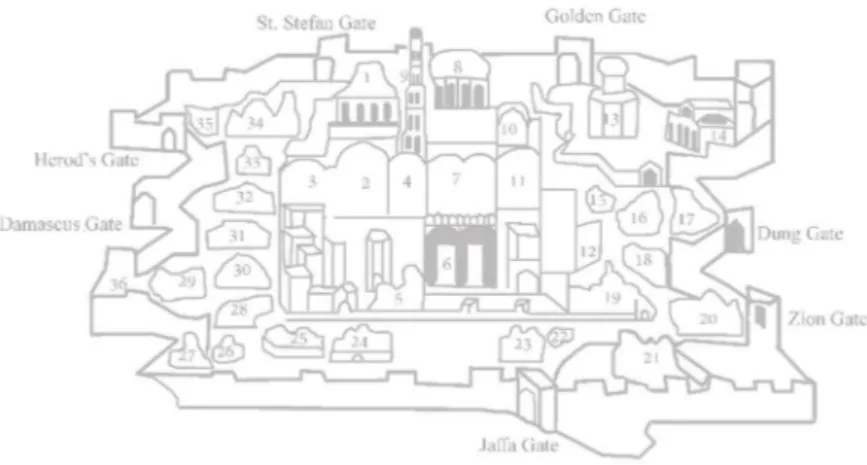

Figure 12 The scheme of Jerusalem, Saydanaiya proskynetaria, 1738-9, Saydanaiya Monastery. ... 91

Figure 13 The scheme of Hama proskynetarion. cat.66. ... 101

Figure 14 The central section, Jerusalem city and Holy Sepulchre, Proskynetaria, Maʿlula Monastery, 1827 ... 108

Figure 15 The scheme of Maʿlula proskynetaria, 1827. ... 109

Figure 16 st George and scenes of his tortures, 40x51.5, private collection, Ne’meh Al Halabi, 1666. (After Agemain, 1993) ... 115

Figure 17 St George rescuing the princess and the servant boy and scenes of his life, 75x89, Orthodox Archbishopric, Latakia, unknown iconographer, 19th. (After DGAM Archives). 116 Figure 18 The scheme of Annunciation icon, Latakia, 1687. ... 128

Figure 19 The scheme of three scenes, Akathist icon, Aleppo, 1714. ... 129

Figure 20 The scheme of Annunciation icon, Sydnaia, 19th. ... 130

Figure 21 The scheme of Annunciation icon, 19th, Georg Monastery, Al Homeyra. ... 131

Figure 22 The scheme of Last supper, the schema the eighteenth century, Dormition Lady church. ... 132

Figure 23 The scheme of Pentecost, the eighteenth century, the Lady-Orthodox church, Idleb. ... 135

Figure 25 The ciborium of altar, Catholic Syriac Mar Asia church, Aleppo. ... 139

Figure 24 The ciborium of altar, Maronite church, Aleppo. ... 139

Figure 26 The scheme of the entry of Lady in the Temple, Aleppo, 1718. ... 140

Figure 27 The sanctuary, the Orthodox Dormition Lady church, Aleppo. ... 141

Figure 28 The altar in the Holy of holies, St John of Damascus church, Damascus. ... 141

Figure 29Bema looking east, Basilica of the Holy Cross, Resafa. (After Loosley, 2012) .... 143

Figure 30 The apse, and the Synthronon, Basilica of the Holy Cross, Resafa. (After Loosley, 2012) ... 144

Figure 31 The scheme of Thomas Sunday icon, 1734, Orthodox Archbishopric, Latakia, ... 145

Figure 32 Simple dome. (Runciman, 1933) ... 147

5

Figure 34 The scene 20th, Akathist, 1714, Aleppo. ... 147

Figure 35 Compound dome with drum. (Runciman, 1933) ... 147

Figure 36 The scheme of saint Simon Stylites the younger icon, Aleppo, 17th ... 149

Figure 37 The column with capital, Al adelia Mosque, 1544.A.D, (Othman, 2009) ... 149

Figure 38 The ambo, detail from the icon of the Elevation of the Venerable Cross, the eighteenth century, Saint Nicolas church, Latakia. Cat.3 ... 150

Figure 39 Small round building, perhaps the Holy Sepulchre, Syria, A.D 500, Museum of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, in Denmark... 153

Figure 40 The Holy Sepulchre Church, Jerusalem city, proskynetarion, Thekla Monastery-Maʿlula, tempera on canvas, Jerusalem school. (After DGAM Archives). ... 156

Figure 41 Key index to the drawing of the Holy Sepulchre in icon-maps of seventeenth and eighteenth centuries ... 157

Figure 42 Key index to the drawing of the Holy Sepulchre in icon-maps of nineteenth century. ... 157

Figure 43 Al- Haram era, the Dome of the Rock, Al-Aqsa Mosque, Sydnaia proskynetarion, 1738-9, Sydnaia Monastery. ... 160

Figure 44 The Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem city, the Entry into Jerusalem icon, details of Cat.22 ... 160

Figure 45 Al-Aqsa Mosque, Sydnaia proskynetarion, 1738-9, Sydnaiya Monastery. ... 160

Figure 46 Al- Haram era, the Dome of the Rock, the fountain, Al-Aqsa Mosque, Maʿlula proskynetarion, Maʿlula monastery. 1827. ... 160

Figure 48 The sketch of Sinai Monastery (Shackley, 128) ... 162

Figure 47 Sinai Monastery, details from Cat.66 ... 162

Figure 49 Monastery of the Cross, detail from Sydnaia proskynetaria. Cat.64 ... 164

Figure 50 Jaffa port, Sydnaia proskynetarion, 1738-9, Saydanaiya Monastery. ... 169

Figure 51 Jaffa port, Ma’lula proskynetarion, 1827, Ma’lula Monastery. ... 169

Figure 52 The scheme of Nativity icon, the eighteenth century, Saint Nicola church, Latakia. ... 183

Figure 53 The scheme of Entry to Jerusalem icon, Idleb, 18th. ... 214

Figure 54 The scheme of Ascension icon, Aleppo, 1718. ... 221

Figure 55 The scheme of Birth of St. John the Baptist icon, Latakia, 1743. ... 239

Figure 56 The scheme of Last Judgment icon, Aleppo, 1708. 1. The Diesis, 2. Apostles, 3. Saints, 4Moses and the Jew people, 5. Adam and Eve kneeling, 6 the sea, 7. The Heavenly Jerusalem, 8. The five women, 9. Saint peter and saints, 10. The dead, 11. The graves, 12. The monster, 13. Hell. ... 267

Figure 57 The scheme of Virgin of the Immaculate Conception icon, Aleppo, 1744. ... 270

Figure 58 The scheme of Akathist, 1714, Dormition Lady church, Aleppo. ... 272

Figure 59 The scheme of Hodegetria and Akathist icon, Al Homeyra, 1765. ... 283

Figure 60 The scheme of icon of two scenes, Sydnaia, 19th. ... 287

Figure 61 The scheme of Sts Peter and Paul icon, 1735, Latakia. ... 304

Figure 62 scheme of St Demetrious icon , the seventeenth century, Hama ... 316

Figure 63 The scheme of Beautiful Gate, 1685, Al Homeyra. ... 318

Figure 64 The scheme of Forty Martyrs icon, Aleppo, 18th. A: the forty martyrs, B: the bath, C the frozen lake. ... 340

6 Tables

Table 1 the icons in the Archives of DGAM ... 19

Table 2 the situation of the Syrian churches which contain Melkite icons. ... 21

Table 3 Melkite icons and their situation. ... 24

Table 4: Table of Annunciation icons, Syria, dating 17th-18th. ... 75

Table 5 The icons of St. George in Syria, dated from 1685 to the first quarter of the Nineteenth century. ... 123

Table of catalogue Cat. 1 The Nativity of Mary, the eighteenth century, in situ in Saint Nicolas church, Latakia, tempera on wood, 30x40 cm, the iconographer; unknown. After DGAM Archives ... 183

Cat. 2 The nativity of Mary, Nineteenth century, in situ in the Sydnaia Monastery, Sydnaia, tempera on wood, the iconographer; Michael Polychronis school. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate ... 185

Cat. 3 Elevation of the Venerable Cross, The eighteenth century, in situ in church of the church Saint Nicolas, Latakia, tempera on wood, 41x69.5 cm, the iconographer; unknown, (AfterDGAM Archives) ... 186

Cat. 4 The Entry of Lady in the Temple,1718, in situ in church of the church Dormition Lady, Aleppo, tempera on wood, 67x90 cm, the iconographer; Hanania Al Halabi, ( After Rand,2011). ... 188

Cat. 5 The entry of Lady in the Temple, 1761, the Lady of Entry, Hama, tempera on wood, 34x44cm, the iconographer; unknown, ( After DGAM Archives) ... 190

Cat. 6 The entry of Lady in the Temple, 1773, the Lady-Orthodox church, Idleb, tempera on wood, 60x75cm, the iconographer; Aleppo school. (After Rand.2011) ... 191

Cat. 7 The Presentation, 1718, in situ in church of the church Dormition Lady, Aleppo, tempera on wood, 67x90 cm, the iconographer; Hanania Al Halabi. (After Rand 2011) ... 192

Cat. 8 The Presentation, 1733, in situ in the Church of Orthodox Archbishopric, Latakia, tempera on wood, 34x43cm, the iconographer; Hanna Al-Qudsi. (After, DGAM Archives) ... 194

Cat. 9 The Presentation, 1734, in situ in the Our Lady Church, Latakia, tempera on wood, 34x43cm, the iconographer; Hanna Al-Qudsi. (After DGAM Archives) ... 196

Cat. 10 The Presentation, the eighteenth century, in situ in the church of The Lady -Orthodox, Idled, tempera on wood, 56x71cm, the iconographer; Aleppo School. (After Rand 2011) .. 198

Cat. 11 The Presentation, the eighteenth century, was in situ in the church the Lady of Entry, Hama, tempera on wood, 37x48cm, the iconographer; Unknown. (After DGAM Archives. ... 199

Cat. 12 The Presentation, 1810, in situ in the church Forty Martyrs, Homs, tempera on wood, 34x50.50, the iconographer; Unknown. Courtesy: Forty Martyrs church. ... 200

Cat. 13 The Presentation, 1814, in situ in the church Sydnaia Monastery, Sydnaia, tempera on wood, the iconographer; Michael Polychronis school. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate. ... 201

Cat. 14 The Annunciation,1687, in situ in the church of St George Orthodox, Latakia, tempera on wood, 70×54 (74.5×58.5) cm, the iconographer; Unknown. (After DGAM Archives.) .. 203

7

Cat. 15 The Annunciation, 1731, Forty Martyrs, Armenian church, Aleppo, tempera on wood, 24x30cm the iconographer; Hanania Al Halabi. (After Rand.2011) ... 205 Cat. 16 The Annunciation, The eighteenth century, in situ in the church the Lady of Entry, Hama, tempera on wood, 38x48cm the iconographer; unknown.(After DGAM Archives). . 206 Cat. 17 The Annunciation, the eighteenth century, in situ in the church Saint Nicolas -Orthodox, Latakia, tempera on wood, 59x84cm, the iconographer; Unknown. (AfterDGAM Archives). ... 207 Cat. 18 The Annunciation, the nineteenth century, in situ in the church Sydnaia Monastery, Sydnaia, tempera on wood, the iconographer; Michael Polychronis school Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate. ... 209 Cat. 19 The Entry to Jerusalem(palm Sunday), 1685, in situ in the church Saint George -Orthodox, Latakia, tempera on wood, 58.5 X 74 cm, the iconographer; attributed to Ne’met Allah Al Halabi. (After Rand.2011) ... 211 Cat. 20 The Entry to Jerusalem(palm Sunday), the eighteenth century, the church the Lady of Entry, Hama, tempera on wood, 32x48 cm, the iconographer; Unknown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 213 Cat. 21 The Entry to Jerusalem(palm Sunday), the eighteenth century the church the Lady-Orthodox, Idleb, tempera on wood, 56x70 cm, the iconographer; Aleppo school. (After Rand.2011) ... 214 Cat. 22 The Entry to Jerusalem, the eighteenth century, in situ in the church Saint Nicolas -Orthodox, Latakia, tempera on wood, 30x40 cm, the iconographer; Unknown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 216 Cat. 23 The Entry into Jerusalem (Palm Sunday), the nineteenth century, in situ in the monastery of saint George, Homeyra, tempera on wood, 34x45 cm, the iconographer; Michael Polychronis school. (After DGAM Archives). ... 218 Cat. 24 The Entry into Jerusalem (Palm Sunday), the nineteenth century, in situ in the monastery of saint George, Homeyra, tempera on wood, 34x45 cm, the iconographer; Michael Polychronis school. (After DGAM Archives). ... 219 Cat. 25 The Ascension, 1718, in situ in the Dormition Lady church, Aleppo, tempera on wood, 70.5x98.5cm, the iconographer; Hanania Al Halabi. (After Rand 2011). ... 221 Cat. 26 The Pentecost, the eighteenth century, in situ in the Lady-Orthodox church, Idleb, tempera on wood, 60x75cm, the iconographer; aleppo school. (After Rand 2011). ... 223 Cat. 27 The Pentecost, 1753, in situ in the Forty Martyrs church, Homs, tempera on wood, 50x66cm, the iconographer; Girgis Al Halabi. (After Rand 2011). ... 224 Cat. 28 The Pentecost, 1778, in situ in Church of Sydnaia Monastery, Sydania, tempera on wood, 38.5x49 cm, the iconographer; deacon Joseph son Michael Elian. (After Zayat, 1987). ... 226 Cat. 29 The Dormition, 1641, in situ in the church the Lady of Entry, Hama, tempera on wood, 42x65cm, the iconographer; Attributed to Youssef AL Halabi. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate ... 228 Cat. 30 The Dormitio, the seventeenth century, in situ in the Sydnaia Monastery, Sydnaia, tempera on wood, the iconographer; unknown. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate. ... 230

8

Cat. 31 The Dormition, 1764, in situ in the monastery of St. George- Al Homeyra, tempera on wood, 39x52.5cm, the iconographer; Son of priest Michael Elian Al Shami. (AfterDGAM Archives). ... 232 Cat. 32 The Dormition, the eighteenth century, private collection, George Antaki, tempera on wood, 73.5x96cm, the iconographer; Attributed to Noamat Allah Al Halabi. (private collection) ... 233 Cat. 33 The escape to Egypt , 1740, in situ in church of the church Sts Constantine and Helena, Yabrod, tempera on wood, 31x37.5 cm, the iconographer; Michael of Damascus. (After La Croix & Emery .2009). ... 235 Cat. 34 The escape to Egypt, the eighteenth century, it was in situ in church the Lady of Entry, Hama, tempera on wood, 60x77cm, the iconographer; unknown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 237 Cat. 35 Birth of St. John Baptist, 1734, in situ in church of the church The Lady –Orthodox, Latakia, tempera on wood, 41.5x49 cm, Hanna Al-Qudsi. (AfterDGAM Archives). ... 238 Cat. 36 Birth of St. John Baptist, 1743, in situ in church of the church Saint Nicolas -Orthodox, Latakia, tempera on wood, 41x49.5 cm, Unknown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 239 Cat. 37 Birth of St. John Baptist, the eighteenth century, in situ in Dormition church, Aleppo, tempera on wood. (After Rand.2011). ... 240 Cat. 38 The Tabernacle( last supper), 1797, in situ in the Sydnaia Monastery, Sydnaia, from wood, Deacon Joseph Elian. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate. ... 241 Cat. 39 Last supper, the eighteenth century, in situ in the church Saint Nicolas -Orthodox, Latakia, tempera on wood, 25x40 cm, the iconographer; Unknown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 243 Cat. 40 Last supper, the eighteenth century, in situ in the church Saint Nicolas -Orthodox, Latakia, tempera on wood, 26x(34-22.5) cm, the iconographer; Unknown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 244 Cat. 41 Last supper, the eighteenth century, in situ in the monastery of St. George- Al Homeyra, tempera on wood, 36x51cm, the iconographer; Unknown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 245 Cat. 42 Last supper, the eighteenth century, in situ in church of Dormition Lady, tempera on wood, 47x68 cm, the iconographer; Unknown. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate. ... 246 Cat. 43 Whashing of Feet, the eighteenth century, in situ in the church Saint Nicolas -Orthodox, Latakia, tempera on wood, 26x (34-22.5) cm, the iconographer; Unknown. (AfterDGAM Archives). ... 247 Cat. 44 The Crucifixion, 1708, in situ in Dormition church, Aleppo, tempera on wood, 70x80cm, Hanania Al Halabi. (After Rand.2011). ... 248 Cat. 45 The Crucifixion, 1713, in situ in the church Saint Andrew-Orthodox, Latakia, tempera on wood, 49x68 cm, the iconographer unknown, the iconographer; Unknown. (AfterDGAM Archives). ... 250 Cat. 46 The Crucifixion, the eighteenth century, in situ in the church Saint Nicolas -Orthodox, Latakia, tempera on wood, 30x40 cm, the iconographer; Unknown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 252

9

Cat. 47 The Crucifixion, the nineteenth century in situ in the Sydnaia Monastery, Sydnaia, tempera on wood, Michael Polychronis school. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate. ... 254 Cat. 48 Lamentation of Christ, the eighteenth century, in situ in the lower church of St George Monastery, Al Homeyra 36x50 cm, the iconographer; unknown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 255 Cat. 49 Thomas Sunday, the seventeenth century, in situ in Dormition Church, Aleppo, 45x45 cm, Attributed to Hanania Al Halabi. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate. ... 257 Cat. 50 Thomas Sunday, 1719, in situ in Dormition Church, Aleppo, 65x86 cm, Hanania Al Halabi. (After Rand 2011).) ... 258 Cat. 51 Thomas Sunday, 1733, in situ in The Lady –Orthodox Church, Latakia, 33.5x43.5 cm, Hanna Al-Qudsi. (After DGAM Archives). ... 260 Cat. 52 Thomas Sunday, 1734, in situ in Orthodox Archbishopric, Latakia, 35x43cm, Hanna Al-Qudsi. (After DGAM Archives). ... 261 Cat. 53 Thomas Sunday, the eighteenth century, in situ in The Saint Nicolas -Orthodox Church, Latakia, 30x40 cm, Attributed to Hanania Al Halabi. (After DGAM Archives). ... 262 Cat. 54 Thomas Sunday, the eighteenth century, in situ in the Lady of Entry Church, Hama, 30x48 cm, the iconographer; unknown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 263 Cat. 55 The Lady of spring, 1735, in situ in the upper church of St George Monastery, Al Homeyra, 38.5x48.5 cm, the iconographer unknwon. (After DGAM Archives). ... 264 Cat. 56 The Lady of spring, 1743, in situ in the Lady orthodox church, Latakia, 32x42.5, Issa Al Qudsi. (AfterDGAM Archives). ... 265 Cat. 57 The Lady of spring, the eighteenth century, in situ in Saint Nicolas -Orthodox church, Latakia, 35x41, the iconographer; unknown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 266 Cat. 58 Last Judgment, 1708, in situ in the Armenian Forty Martyrs Church, Aleppo, 250x300 cm, Ne’mett Allah Al and his son Hanania AL Halabi. (After Rand.2011). ... 267 Cat. 59 Last Judgment, 1708, in situ in the Armenian Forty Martyrs Church, Aleppo, 250x300 cm, Ne’mett Allah Al and his son Hanania AL Halabi. (After Rand.2011). ... 270 Cat. 60 Akathist, 1714, in situ in Dormition Church, Aleppo, 86x65.5 cm, Ne’mett Allah Al Halabi. (After Rand.2011). ... 272 Cat. 61 Hodegetria and Akathist, 1765, in situ in the lower church of St George Monastery, Al Homeyra 68,6x91 cm, Girgis Al Halabi. (After Rand.2011.) ... 283 Cat. 62 Icon of two scenes(The entry of Lady in the Temple, The nativity of Mary), the nineteenth century in situ in the Sydnaia Monastery, Sydnaia, tempera on wood, Michael Polychronis school. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate. ... 287 Cat. 63 Icon of four scenes( Tomah Sunday, Ascension, Sts Peter and Paul, Cosmas and Damian), the beginning of nineteenth century in situ in the Sydnaia Monastery, Sydnaia, tempera on wood, Michael Polychronis school. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate. ... 289 Cat. 64 proskeyntarion, the icon with the topography of the Holy land , 1738-39, in situ in the Sydnaia Monastery, Sydnaia, tempera on canvas, 90x125 cm, the iconographer; Issa Al Qodsi. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate. ... 290

10

Cat. 65 proskeyntarion, the icon with the topography of the Holy land, 1748, was in the Lady of entry church, Hama, tempera on canvas, 80x123cm, the iconographer: unknown. (After DGAM Archives)... 292 Cat. 66 proskeyntarion, the icon with the topography of the Holy land, 1827, St Thekla Monastery-Maʿlula, tempera on canvas, 80x120 cm, the iconographer: Jerusalem school. (After DGAM Archives). ... 294 Cat. 67 Saint Simon Stylites the younger Before 1667, in situ in the Dormition church, Aleppo, 78.5x116 cm, Attributed to Yousef AL Halabi. (After Rand.2011). ... 296 Cat. 68 The Ascension of the Prophet Elijah, the Seventeenth century, Saint George –Orthodox Church, Latakia 34x40 cm, Aleppo School. (After DGAM Archives). ... 299 Cat. 69 St John Baptist and scenes of his life, the eighteenth century, in situ in the Dormition church, Aleppo, 72.5x102.5cm, Attributed to Hanania Al Halabi. (After Rand.2011). ... 300 Cat. 70 Beheaded of Saint John the Baptist, 1767, in situ in the Sydnaia Monastery, Sydnaia, tempera on wood, 81x111cm, The Iconographer: deacon Joseph son Michael Elian. (After Zayat, 1987). ... 302 Cat. 71 Sts Peter and Paul, 1735, in situ in Saint George –Orthodox, Latakia, tempera on canvas, 51x68 cm, Hanania Al Halabi. (After DGAM Archives). ... 304 Cat. 72 SS Peter and Pau, The eighteenth century, in situ in the upper church of St George Monastery, Al Homeyra 33.5x48 cm, the iconographer; unknown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 306 Cat. 73 Sts Peter and Paul, The eighteenth century, was in situ in the Lady of Entry church, Hama, 38x49 cm, the iconographer; unknown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 307 Cat. 74 SS Peter and Paul, the nineteenth century, in situ in the Saint George –Orthodox Church, Latakia, 24x29cm, the iconographer; unkown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 308 Cat. 75 St Peter in the prison, 1811, in situ in the upper church in the St George Monastery, Al Homeyra, 25x33.5 cm, Michael Polychronis school. (After DGAM Archives). ... 309 Cat. 76 Jacob's ladder, 1765, in situ in the Sydnaia Monastery, Sydnaia, tempera on wood, 83x113.5cm, Silvestre Of Antioch. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate. ... 310 Cat. 77 John Climax, 1811, in situ in the Sydnaia monastery, Sydnaia, temper on wood, 45x63 cm,Michael of Crete. (After, La Croi&Emery, 2006). ... 312 Cat. 78 St. Barbara, 1714, the church of Dormition Lady, Aleppo, 44x64cm, Hanania Al Halabi. (After Rand.2011) ... 314 Cat. 79 St Demetrious , the seventeenth century, was in The Lady of Entry church, Hama, 86x119cm, Aleppo school.( After DGAM Archives). ... 316 Cat. 80 Beautiful Gate(George and Demetrious ), 1685, the lower church in the St George Monastery, Al Homeyra, 85x120 cm, Nomaat Allah Al Halabi. (After Rand.2011). ... 318 Cat. 81 St George combating the dragon, 1706, in situ in the church of Dormition Lady, Aleppo, 60.5x70.5cm, Noamat Allah Al Halabi. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate. ... 321 Cat. 82 St George combating the dragon, 1706, in situ in the church St. Elias of Maronite, Aleppo, 99.2x142.8 cm, Noamat Allah Al Halabi. (After, La Croix&Emery, 2006). ... 323 Cat. 83 St George combating the dragon, 1717, the Armenian Forty Martyrs church, Aleppo, 100x139 cm, Hanania Al Halabi. .(After Rand.2011) ... 325

11

Cat. 84 St George combating the dragon, rescuing the princess, 1765, the Sydnaia monastery, Sydnaia, Sydnaia, tempera on wood, Silvestre Of Antioch. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian

Patriarchate. ... 327

Cat. 85 St George and scenes of his life, the eighteenth century, was in the Entry Lady church, Hama, 40x51cm, the iconographer; unknown. (After DGAM Archives). ... 329

Cat. 86 Theodore and scenes of his tortures, 1734, Orthodox Archbishopric, Latakia, 66x81 cm, Hanania Al Halabi. (After Rand.2011) ... 330

Cat. 87 The Forty Martyrs, 1706, the church of Dormition Lady, Aleppo, 36x45cm, Attributed to Ne’met Allah Al Halabi. Courtesy: Orthodox Antiochian Patriarchate. ... 333

Cat. 88 The Forty Martyrs, 1732, the lower church in the St George Monastery, Al Homeyra, 54x64 cm, Hanania Al Halabi. (After, Rand.2011) ... 335

Cat. 89 The Forty Martyrs, the eighteenth century, the Lady-Orthodox church, Idleb, 72x90 cm, tempera on wood, Aleppo school, (After DGAM Archives). ... 337

Cat. 90 The Forty Martyrs, the eighteenth century, the Lady-Orthodox church, Latakia, 35.5x46 cm, tempera on wood, the iconographer; unknown. (After DGAM Archives) ... 338

Cat. 91 The Forty Martyrs, the eighteenth century, the church of Dormition Lady, Aleppo, 36x47cm, Aleppo school. (After DGAM Archives) ... 340

Contents Acknowledgments... 3 Table of figure: ... 4 Tables ... 6 Table of catalogue ... 6 Contents ... 11 Abstract ... 16 Introduction ... 17 1. Historical Introduction ... 25

1.1 Syria During the Ottoman Period, Aleppo And Damascus ... 25

1.2 Christian Communities In Syria During Ottoman Period. ... 31

1.2.1 Millet System... 34

1.2.2 Melkite Church during Ottoman period. ... 36

2. Melkite Art During 1650-1825 ... 46

2.1 The Reasons of Melkite Renaissance Of Icons ... 46

2.2 The Melkite Art During 17-18 Centuries. ... 58

2.3 Melkite Icons Features. ... 63

3. Analysis of Various Icons and the Architectural Background ... 67

3.1 Analysis of Narrative icons ... 67

3.1.1 The Annunciation ... 68

12

3.1.3 The Crucifixion ... 78

3.1.4 The Ascension: ... 79

3.1.5 The Presentation into the Temple ... 80

3.1.6 The Entry To Jerusalem ... 83

3.2 Analysis Of Proskynetaria Icons. ... 85

3.2.1 The Proskynetarion As A Pilgrimage Object: ... 85

3.2.2 The Prototype Of The Proskynetaria: ... 87

3.2.3 Proskynetaria In Syria ... 88

3.3 Analysis Of Individual Icons, Saint Georg Icon As An Example. ... 112

3.3.1 The Architectural Background In The Vita Icons Of St George And Passion Scenes ... 114

3.3.2 The Architectural Background On The Typical Scenes Of St George ... 117

4. Reverse Perspective and architecture in Melkite icons ... 124

4.1 Reverse perspective meaning ... 125

4.2 Analysis of Various Melkite Icons ... 126

4.2.1 The Annunciation ... 127

4.2.2 The Last Supper ... 132

4.2.3 The Pentecost ... 133

5. The Architectural representations at background and foreground of Melkite icon. ... 138

5.1 The architectural elements and the local architectural impacts... 138

5.1.1 Ciborium and Altar ... 139

5.1.2 Bema or Synthronon ... 142

5.1.3 Apse and Dome ... 145

5.1.4 Columns ... 148

5.1.5 Ambo ... 150

5.1.

6

Fountains and Basins ... 1515.2 Architectural scenes ... 152

5.2.1 The representations of historical buildings ... 152

5.2.2 The representation of monastery ... 161

5.2.2 The representations of cities in Melkite icons ... 165

The results ... 172

The conclusion ... 173

Glossary of Terminology ... 176

Appendices ... 180

The catalogue ... 183

1- Nativity of Mary, 18th C, Latakia. ... 183

13

3- Elevation of the Venerable Cross, 18thC, Latakia. ... 186

4- Entry of Lady in the Temple, 1718, Aleppo. ... 188

5- Entry of Lady in the Temple, 1761, Hama ... 190

6- Entry of Lady in the Temple, 1773, Idleb ... 191

7- The Presentation into the Temple, 1714, Aleppo. ... 192

8- The Presentation into the Temple, 1733, Latakia. ... 194

9- The Presentation into the Temple, 1734, Latakia. ... 196

10- The Presentation into the Temple, 18th C, Idleb. ... 198

11- The Presentation into the Temple, 18thC, Hama. ... 199

12- The Presentation into the Temple, 1810, Homs. ... 200

13- The Presentation into the Temple, 1814, Sydnaia. ... 201

14- The Annunciation, 1687, Latakia. ... 203

15- The Annunciation, 1731, Aleppo. ... 205

16- The Annunciation, 18thC, Hama... 206

17- The Annunciation, 18th C, Latakia. ... 207

18- The Annunciation, 19th C, Sydnaia. ... 209

19- The Entry into Jerusalem, 1685, Latakia... 211

20- The Entry into Jerusalem, 18th C, Hama. ... 213

21- The Entry into Jerusalem, 18th C, Idleb. ... 214

22- The Entry into Jerusalem, 18thC, Latakia. ... 216

23- The Entry into Jerusalem, 18th C, Al Homeyra ... 218

24- The Entry into Jerusalem, 19th C, Sydnaia. ... 219

25- The Ascension, Aleppo, 1718. ... 221

26- The Pentecost, 18th C, Idleb. ... 223

27- The Pentecost, 1753, Homs. ... 224

28- The Pentecost, 1778, Sydnaia. ... 226

29- The Dormition Of The Virgin, 1641, Hama... 228

30- The Dormition Of The Virgin, 17thc, Sydnaia. ... 230

31- The Dormition Of The Virgin, 1764, Al Homeyra. ... 232

32- The Dormition of the Virgin in Private Collection, 18th Century. ... 233

33- The flight into Egypt, 1740, Yabrod. ... 235

34- The flight into Egypt, 18thC, Hama. ... 237

35- Birth Of St. John The Baptist, 1734, Latakia. ... 238

36- Birth Of St. John The Baptist, 1743, Latakia. ... 239

14

38- The Tabernacle (Last Supper), 1797, Sydnaia. ... 241

39- Last Supper, 18thc, Latakia ... 243

40- Last supper, 18thC, Latakia... 244

41- Last Supper, 18thC, Al Homeyra. ... 245

42- Last Supper, 18thC, Aleppo. ... 246

43- Washing of Feet, 18thC, Latakia. ... 247

44- The Crucifixion, 1708, Aleppo. ... 248

45- The Crucifixion, 1713, Latakia. ... 250

46- The Crucifixion, 18th century, Latakia. ... 252

47- The Crucifixion, 19th century, Sydnaia. ... 254

48- Lamentation of Christ, 18thC, Al Homeyra. ... 255

49- Thomas Sunday, 17thC, Aleppo. ... 257

50- Thomas Sunday, 1719, Aleppo. ... 258

51- Thomas Sunday, 1733, Latakia. ... 260

52 - Thomas Sunday, 1734, Latakia. ... 261

53- Thomas Sunday, 18thC, Latakia. ... 262

54- Thomas Sunday, 18thC, Hama. ... 263

55- The Mother of God of the Life-giving Spring, 1735, Al Homeyra. ... 264

56- The Mother of God of the Life-giving Spring, 1743, Latakia. ... 265

57- The Mother of God of the Life-giving Spring, 18thC, Latakia. ... 266

58- Last Judgment, 1708, Aleppo. ... 267

59- Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, Aleppo, 1744. ... 270

60- Akathist, 1714, Aleppo. ... 272

61- Hodegetria And Akathist, 1765, Al Homeyra. ... 283

62- Icon Of Two Scenes, 19thc, Sydnaia. ... 287

63- Icon Of Four Scenes, 19thc, Sydnaia. ... 289

64- The Proskeyntarion, 1738-39, Sydnaia. ... 290

65- The proskeyntarion, 1748, Hama. ... 292

66- The Proskeyntarion, 1827, Maʿlula. ... 294

67- St Simeon Stylites The Younger, 17thc, Aleppo. ... 296

68- The Ascension Of The Prophet Elijah, 17thc, Latakia. ... 299

69- St John Baptist And Scenes Of His Life, 18th C, Aleppo ... 300

70- Beheaded Of St John The Baptist, 1767, Sydnaia... 302

71- SS Peter And Paul, 1735, Latakia. ... 304

15

73- SS Peter And Paul, 18thc, Hama. ... 307

74- SS Peter And Paul, 19thc, Latakia. ... 308

75- St Peter In The Prison, 1811, Al Homeyra. ... 309

76- Jacob's Ladder, 1765, Sydnaia. ... 310

77- John Climax (Climacus), 1811, Sydnaia. ... 312

78- St Barbara, 1714, Aleppo. ... 314

79- St Demetrius, Hama, 17th ... 316

80- The Beautiful Gate (Sts George and Demetrious), 1685, Al Homeyra... 318

81- St George Combating The Dragon And Rescuing The Princess, 1706, Aleppo. .... 321

82- St George Combating The Dragon And Rescuing The Princess, 1706, Aleppo. .... 323

83- St George combating the dragon, rescuing the princess, 1717, Aleppo... 325

84- St George Combating The Dragon, Rescuing The Princess, 1765, Sydnaia. ... 327

85- St George And Scenes Of His Tortures, 18thc, Hama. ... 329

86- St Theodore And Scenes Of His Tortures, 1734, Latakia. ... 330

87- The Forty Martyrs, Aleppo, 1706... 333

88- The Forty Martyrs, Al Homeyra, 1732 ... 335

89- The Forty Martyrs, Idleb, 18thc ... 337

90- The forty Martyrs, 18thC, Latakia. ... 338

91- The forty Martyrs, 18thC, Aleppo. ... 340

16 Abstract

To put it in the simplest of terms: in the beginnings of the seventeenth century, the Melkite renaissance had begun during domination Ottoman by the religious framework of Islam, in Syria, and especially in Aleppo. Where Aleppo has restored the art of icon in Melkite church that took a remarkable place in the history of the post-Byzantine art. In this dissertation I discuss the architecture in Melkite Art utilizing 91 icons as a case study. These icons will be catalogued and explained one by one. I will begin by talking about the relationship between architectural backgrounds and the depicted subject which will be divided into three types; narrative, the proskynetaria, and individual icons. In the next section I will be discussing the Reverse perspective, and how the Melkite artist used it. In the latter part, which is the main goal of this dissertation, the focus will be the types of architectural representations, questioning the way in which the Melkite artist depicted architectural elements such as domes, bema, columns, etc. Discussing how they represented historical buildings such as the Holy Sepulchre, monasteries, and to conclude general thoughts about the repetition of architectural elements in Melkite art in Syria during the Ottoman period.

17 Introduction

Melkite Religious art has been of increasing interest to art historians in recent years and new attempts are being made to define its characteristic features and to evaluate it through modern art historical approaches. The result has been a greater appreciation for the aesthetic values of Melkite art and deeper sympathy with its objectives. Nearly 50 years ago Virgil Gandea, a Romanian scholar, attributed the term “Melkite icons” to the icons that were produced in the See of the Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria Patriarchates. His source was the derisive expression “Melkite” used by heretic Nestorian Christians to refer to communities which remained loyal to the Byzantine State Church after the early theological disputes over the nature of Christ. It was used when he was a consultant for an exhibition of icons from Lebanese and Syrian collections produced by the Sursock Museum of Beirut in May 1969.

As early as the 15th century, under the reign of Mehmet the Conqueror, icons have been imported, especially from Crete. The renewal of shapes and colors in icon production done in Syria, first at Aleppo, drawing inspiration from Greece and the Balkans then from Islamic and Ottoman art around the second half of 17th century.

This dissertation grew out of my earlier book and master thesis on the Aleppo school of Icons. The conviction grew on me that the Melkite art deserved a study of its own. Not that there are no books or studies about itthe pictorial art of the Melkite living under the rule of the Ottoman period has been made the subject of a separate study but the architecture in Melkite art has not yet been systematically studied in any depth, for it is generally assumed that Melkite art departs from the accepted language of post-byzantine1 iconography only occasionally and

incidentally.

An icon could be a mosaic, or a coin; it could be elaborate or simple, one of a kind or mass produced.2 The word “icon”, in our search, is associated with a portrait of a holy figure on

wood panel, painted with tempera.

The sources for the study of the architecture of the Melkite icons in Syria are the portable paintings, which can broadly be divided into two heads: Icons of the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries, which can again be subdivided into two broad heads, Aleppo school’s icons, and the icons of independent artists. The second head is the icons of the first quarter of the nineteenth century. These icons are at churches in Syria, hanging on the walls of churches and on the iconostasis3, also there are some missed icons that exist in the archives of DGAM.

1 The term “post-Byzantine” is used by many Byzantinists to indicate the work of artists Greek, Syrian, sirbian,

which was done after 1453. They have accepted that the conquest of Constantinople by Mehmet II on May 20, 1453, was a date of exclusively historical significance and limited import as far as the continuity of the Byzantine artistic tradition is concerned.

2 Kurt Weitzmann, The icon: Holy images--sixth to fourteenth century (New York: G. Braziller, 1978) 13ff. 3 It is a lattice screen of marble or wood that is decorated with icons and that, in byzantine churches, separates the

sanctuary and the altar from the main body of the church. The two part are linked by three doors: two side doors and the so-called Beautiful Gate, or Holy door, in the middle. Erwin Fahlbusch and G. W. Bromiley, The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Editors, Erwin Fahlbusch … [et Al.]; Translator and English-Language Editor, Geoffrey W. Bromiley; Statistical Editor, David B. Barrett (2 vols., Grand Rapids, Mich., Cambridge: Eerdmans, 2001-2008) 648

18

Apart from these icons, which are the most important source material for the study of the architectural scenes, there is another type of material which is also as important as these portable paintings. There are icons that exist in different places in private holdings that are important to this study. But a study of these icons, isolation might not be enough to identify some features of architecture properly unless we have to refer to the icons which were signed by family of Youssef Al- Halabi, and they are existing in Lebanon. For a proper understanding and appreciation of the architectural elements and scenes of these icons in Syria we must refer to these icons in Lebanon; especially those which are existing at Balamand monastery, St John Baptist at Al- Khinshara, and private collections. These groups were chosen because these monasteries were culturally and religiously connected with Aleppo city, as well as there having been many monks from Aleppo at these monasteries.

In Aleppo city, the important churches are Orthodox, Maronite, and Armenian. Additionally, there are icons of the Aleppo school in the private collections of Aleppo’s houses such as the George Antakya collection and the Edvin Khori collection.

(1) Aleppo city: I visited Aleppo city, Gdeydé (the new) Quarter, and there are four churches, with icons of Aleppo school, for instance; The Dormition Lady of orthodox church, Forty Martyrs of Orthodox Arminian Church, the Lady church of Catholic, and St. Elias of Maronite church.

(2) Hama and Idleb Cities: there is the Church of the Lady of Entry and Church of the Lady at Idleb, both of which belong to the Orthodox Church.

(3) Latakia City: there are five Orthodox churches; Orthodox Archbishopric, St. George, St. Nicolas church, the lady church, and St. Andrew church.

Reference will be made to the icons in Sydnaia churches near to Damascus and Monastery of St. George at Al Homeyra near to Homs. These icons are no doubt the most important and dependable source material for this study, because they are situated in the places belonging to the area of study. The other place where the icons of Aleppo can be found is the church of Forty Martyrs at Homs, and there are many icons in Lady Church at Dair Atyah.

The literary- religious background of the icons can be studied through the following texts, which seem to have given the major guidance to the iconographies.

(1) The liturgical texts of the Orthodox church are replete with references to the iconic types and different writings pertaining to Christ and many of the Saints.

There are numerous liturgical texts dating to the 17th and 18th centuries, like The Horology

“Book of Hours,” containing the fixed texts of the services of the Daily Cycle. The Synaxarium is the collection of short lives of saints and some ecclesiastic events.

(2) Travel Literature of church and ecclesial manuscripts contain veritable source materials for the interpretation of the themes.

19

The most important of these texts is “Travels of Macarius, Patriarch of Antioch,” written by his Attendant archdeacon, Paul of Aleppo, in Arabic. 4

It is clear from the outside that my argument is based mainly on icons of the eighteenth century, in other words, it presents iconographical school of this art. It intends to convey an idea of Melkite icons scrutinized in their historical context. The Melkite art has been of increasing interest to art historians in recent years and new attempts are being made to interpret its character.

Table 1 the icons in the Archives of DGAM

From the the table 1 it emerges that the archives of icons in DGAM has about 1197 icons which spread in all of Syria, both in churches and monasteries. These icons belong to many different iconic schools, Melkite, Russian and Greek, dated between 17th and 19th centuries. They are

very diverse in both depicted themes and measurements. Thus, for studying the Architecture at the Melkite icons in Syria from the middle of seventeenth until the beginnings of nineteenth centuries, we omit every icon that does not belong to Melkite art and does not date to our studied period between 1650-1830, then after observing all these icons, we found 220 icons. In

4 Paul was born in 1627; His father, Patriarch Macarius. He inherited the love of study and research. He was

ordained a reader by his father, then bishop of Aleppo, in the Cathedral of St. Mary at Damascus after his pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Shortly afterwards, on 17 February 1644, Paul was married, he was 17 years old. On 21 November of the same year, he was promoted archdeacon of Aleppo, Damascus and all the Patriarchate of Antioch. Paul spent all his life with his father, he was his companion in all his travels and his appointed historian. He died on July 1669, on his return from the second voyage from Macarius to Russia, a month after their arrival in Georgia. The fact is attested in a letter from Macarius to Patriarch Joseph of Moscow, dated the same day. Athanase III Dabbas causes him to die poisoned on June 22 vs. of the same year 17 Joseph Nasrallah, Histoire du mouvement littéraire dans l'Eglise melchite du Ve au XXe siècle (1 vol., Louvain: Peeters, 1979) 219

The region Icon

Aleppo 86 Damascus 228 Deir Atia 60 Hama 125 Homeyra 57 Idleb 45 Latakia 75 Maʿlula 81 Qara 36 Rif Damascus 65

Swyda and Daraa 24

Sydnaia 90

Tartuos 140

Yabrod and Nabek 85

20

the end, there are 91 icons Melkite icons that have architectural backgrounds and date to our studied period.

The present work will focus on the following 91 icons in the catalogue. My study on the iconography of these icons will argue in favor of the thesis that there is a relationship between Melkite art and the local architecture of Aleppo and Syria.

Before studying the architecture in Melkite icons, the icons will have been classified by; the name of icon, the name of the church, the dimensions, the dating, and the iconographer. Moreover, the situation of each of them, whether they are existing, destroyed or stolen, has been classified, keeping in mind that the majority of churches has been destroyed as a result of the Syrian crisis, see table. 2; (27) icons were stolen and the fate of roughly (46) is unknown. See table.3.

Moreover, this catalogue of icons has the explanations for 92 icons, then drawing schemes of (32) icons to clarify the architectural scenes and elements. This assists in demonstrating how Melkite iconographers represented architectural backgrounds and foreground in Melkite art. This dissertation will fall into five various lengths chapters, the first two chapters are dedicated to understanding the renaissance of the seventeenth and eighteenth-century Melkite communities in Syria.

The third chapter will deal with architectural backgrounds of Melkite icons. By analyzing various icons within the catalogue, the architectural backgrounds can be understood. Three types of icons can be observed; narrative, proskynetaria and individual icons. Some icons have an architectural background or just an architectural element that forms the scene of the event or refers to it. So, there is clearly some relationship between the icons and architecture scenes. Take the festal icon for instance, an architectural scene or at least, just an architectural element like a column, wall, etc. must be visible. The painted topic and its context shape one another and changes in both the topic and architecture can bring profound changes the scene. Therefore, when artists chose the topic of the icon, they need to use architecture elements to define the space and the intended location. Thus, for discussing that, the fifth chapter will be devoted to the analyzing these architectural features in Melkite Art.

In addition, a full chapter, the fourth, is devoted to the perspective drawing largely on the work of other scholars, a repertory is analyzed various icons which illustrated by reverse perspective, as well as of those portraying narrative scenes. These narrative icons will be as follows; the Annunciation, the Last Supper, and the Pentecost icons.

The fifth chapter will be devoted to the analyzing the architectural elements and the scenes in Melkite icons. As soon as we begin to look at the architectural scenes and elements in that light, we can realize both richness and the vast amount of freedom that the Melkite artist put at our disposal. The better we know and understand, as from inside, the creative power of Melkite artists which has manifested itself in the architectural forms we have inherited. Concluding, as the results indicates, Melkite architectural scenes can be classified into three broad categories, Generic representations, representations of specific architectural and symbolic representations.

21

The goal of this thesis is to explore the representations of architecture in Melkite art. The thesis's field of research encompassed the icons of archives DGAM, and some icons from private collections.

N State Church church situation

1 Aleppo Dormition Lady Destruction of the church’s stones

2 Aleppo Forty Martyrs Physical damage to the building + theft of its contents

3 Aleppo St. Elias- Al Hamidiah fine

4 Aleppo St. Elias of Maronite Physical damage to the building + theft of its contents

5 Aleppo Catholic cathedral church Damage to the building

6 Hama the Lady of Entry fine

7 Hama The Lady (Syrian) fine

8 Homs St. George- Homeyra fine

9 Homs Forty Martyrs Severe damage to the building

10 Idleb the Lady-Orthodox

Armed attack + the destruction of all crosses and icons + theft of 11 registered archaeological icons + the destruction of all crosses and icons + theft of 11 registered archaeological icons

11 Latakia Saint Nicolas -Orthodox fine 12 Latakia Orthodox Archbishopric fine 13 Latakia Saint Andrew- Orthodox fine 14 Latakia The Lady -Orthodox fine 15 Latakia Saint George -Orthodox fine 16 Rif Dimashq Sydnaia Monastery fine 17 Rif Dimashq Sts. Constantine and Helena,

Yabrod Physical damage to the building 18 Rif Dimashq St Thekla Monastery-Maʿlula fine

19 Rif Dimashq Hagia Sophia- Sydnaia fine 20 Rif Dimashq Lady Church-Dair Atyah fine 21 Rif Dimashq St. George Monastery-Sydnaia fine

22

N the name of icon Date The situation of icon 1 The nativity of Mary 18thC restored

2 The nativity of Mary 19thC need to restoration 3 Elevation of the Venerable Cross 18thC need to restoration 4 The entry of Lady in the Temple 1718 unknown fate 5 The entry of Lady in the Temple 1761 missing 6 The entry of Lady in the Temple 1773 stolen 7 The presentation 1714 unknown fate 8 The presentation 1733 need to restoration 9 The presentation 1734 need to restoration 10 The presentation 18thC stolen

11 The presentation 18thC missing

12 The presentation 1810 need to restoration 13 The presentation 1814 need to restoration 14 The Annunciation 1687 need to restoration 15 The Annunciation 1731 unknown fate 16 The Annunciation 18thC restored

17 The Annunciation 18thC need to restoration 18 The Annunciation 19thC need to restoration 19 the Entry into Jerusalem 1685 restored

20 the Entry into Jerusalem 18thC missing 21 the Entry into Jerusalem 18thC stolen

22 the Entry into Jerusalem 18thC need to restoration 23 the Entry into Jerusalem 19thC need to restoration 24 the Entry into Jerusalem 19thC need to restoration 25 The Ascension 1718 unknown fate 26 Pentecost 1753 need to restoration

27 Pentecost 18thC stolen

28 Pentecost 1778 need to restoration 29 The Dormition 1641 restored

30 The Dormition 17thC restored

23

32 The Dormition 18thC need to restoration 33 The escape to Egypt 1740 restored

34 The escape to Egypt 18thC missing

35 Birth of St. John Baptist 1734 need to restoration 36 Birth of St. John Baptist 1743 need to restoration 37 Birth of St. John Baptist 18thC unknown fate 38 the Tabernacle( last supper)

1797-1798 need to restoration 39 The Last supper 18thC need to restoration 40 The Last supper 18thC need to restoration 41 The Last supper 18thC need to restoration 42 The Last supper 19thC unknown fate 43 Washing the Feet 18thC need to restoration 44 The Crucifixion 1708 unknown fate 45 The Crucifixion 1713 need to restoration 46 The Crucifixion 18thC need to restoration 47 The Crucifixion 18thC need to restoration 48 Lamentation of Christ 18thC need to restoration 49 Thomas Sunday 17thC unknown fate 50 Tomats Sunday 1719 unknown fate 51 Thomas Sunday 1733 need to restoration 52 Thomas Sunday 1734 need to restoration 53 Thomas Sunday 18thC need to restoration 54 Thomas Sunday 18thC missing

55 The Mother of God of the

Life-giving Spring 1735 need to restoration 56 The Mother of God of the

Life-giving Spring

1743 need to restoration 57 The Mother of God of the

Life-giving Spring 18thC need to restoration 58 the Last Judgment 1708 unknown fate 59 the Virgin of the Immaculate

Conception 1744 unknown fate

60 Akathist 1714 unknown fate

61 Icon of two scenes 19th C restored 62 Icon of two scenes 19th C restored

24

63 Hodegetria and Akathist 1765 need to restoration 64 The proskynetarion 17thC need to restoration 65 The proskynetarion 1748 missing

66 The proskynetarion 1827 unknown fate 67 Simon, who is from the

miraculous mountain before 1667 unknown fate 68 Ascension of the Prophet Elijah 17thC need to restoration 69 St John Baptist and scenes of his

life 18thC unknown fate

70 the Beheaded of Saint John the

Baptist 1767 restored

71 Sts Peter And Paul 1735 need to restoration 72 Sts Peter And Paul 18thC need to restoration 73 Sts Peter And Paul 18hC missing

74 Sts Peter And Paul 19thC need to restoration 75 St peter in the prison 1811 need to restoration 76 Jacob's Ladder 1765 need to restoration 77 john Climacus 1811 restored

78 St Barbara 1714 unknown fate

79 St Dimitri 17thC missing

80 the Beautiful Gate (George and

Dimitri) 1685 restored

81 St George combating the dragon 1706 unknown fate 82 St George combating the dragon 1706 unknown fate 83 St George combating the dragon 1717 unknown fate 84 St George combating the dragon 1765 need to restoration 85 St George and scenes of his

tortures 18thC missing

86 Theodore and scenes of his

tortures 1734 need to restoration 87 The Forty Martyrs 1706 unknown fate 88 The Forty Martyrs 1732 restored 89 The Forty Martyrs 18thC stolen

90 The Forty Martyrs 18thC need to restoration 91 The Forty Martyrs 18thC unknown fate

25 1. Historical Introduction

The following pages examine the political, religious and commercial environment in which the Arabic speaking Christians lived during Ottoman period. These factors produced a rich soil for a burst of Christian artistic activity, which would be called Melkite Renaissance.

At the beginning of this academic work I will be dividing my research material into two sections: the first section gives a panoramic history of Syria within its modern political borders. The second section elaborates on Christian communities during the Ottoman period and the Melkite community in Aleppo.

1.1 Syria During the Ottoman Period, Aleppo And Damascus

What is new and what is traditional in the history of Syria during the Ottoman sultanate, especially the years; 1650-1825? By understanding this period of history, that of Aleppo, will clarify the framework for the assessment of the social, economic and political characteristics of the age. Thus, revealing some of the aspects emerging of the Melkite icon in Aleppo that speared later too many cities and villages such as Damascus, Latakia, Hama and Homs. Moreover, it is essential for the Levant or so called Bilād al Shām history to be considered as two main periods: the first is when the empire was at its peak during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and the second, is when the empire weakend and was described as the sick man. Throughout the Ottoman period geographical Syria and northern Iraq were linked both culturally and economically. They also shared similar political experiences. Three major caravan cities – Aleppo, Damascus and Mosul – dominated the region and after some initial indecision, the Ottomans created three provinces5, centered on each.6 Bilād al Shām was

divided in three (iyala/iyalat, pashalik)7 in 1529; Aleppo, Damascus, and Tripoli.8 Saida

(Sidon) became the second town in southern Bilād al Shām after Damascus and was closely connected to it. As the port city of Damascus and its hinterland, the wali9 of Sidon became

dependent on the wali of Damascus.10

5 In Bilād al Shām, the Ottomans changed some of the administrative provinces in it, and they established Ayyala

Sidon, Beirut and Safad, along with the three large Ayles such as Aleppo, Sham, and Tripoli. Ayyala consisted of the following Sanjak: Antioch, Orfa, Manbeg, Maara, Adna, Kulz, Saheremik, Musayaf, Birecik, Turkmen, Aleppo and Azaz. While Ayala al-Sham included: Jerusalem, Gaza, Nablus, Ajloun, Lagoon, Tadmur, Karak and Shobak, finally Ayyala of Tripoli consisted of Sanjak Hama, Homs, Salameh, Jabla, Lattakia, and the Hoson. Sahar Hanafi, The commercial relations between Egypt and Greater Bilad Al Sham in the 18th century (History of Egyptians, Egyptian General Book Authority, 2000) 14

6 Bruce Masters, Semi-autonomous forces in the Arab provinces (ed. Kate Fleet, Suraiya Faroqhi and Reşat

Kasaba; The Cambridge history of Turkey, Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008-2013) 186– 206, at 189

7 in the 17th 18th centuries the synonymous eyalyt became the preferred use Gustav. Bayerle, Pashas, begs and

effendis: A historical dictionary of titles and terms in the Ottoman Empire / Gustav Bayerle (Istanbul: Isis Press, 1997) 166

8 The province of Tripoli in Syria established in 1593. ibid., 153

9The governor-general of vilayet. By the eighteenth century the term vali replaced beglerbegi. ibid., 164 10 Stefan Weber, Space, Urban Institutions and Society in Ottoman Bilad al-Sham The Making of an Ottoman

Harbour Town: Sidon/Saida from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Centuries (ed. Abdul-Karim Rafeq and Peter Sluglett; THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF THE OTTOMAN CONQUEST ON: Syria and Bilad al-Sham under Ottoman rule; The Ottoman Empire and its heritage politics, society and economy v. 43, Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2010) 177–239, at 187

26

The boundaries of the ilayets were not stable.11 In the seventeenth century, the military and

administrative structure of the Syrian provinces changed significantly in comparison with the Ottoman golden age.12 Although, Syria was divided into two provinces, with Aleppo and

Damascus as their respective capital cities,13 in 1624 the sultan acknowledged Fakhr-al-Din as

lord of the Arab lands from Aleppo to the borders of Egypt, under Ottoman suzerainty.14 The

main challenge to Istanbul’s authority in seventeenth-century Lebanon came from the Ma‘n dynasty who claimed the Druze emirate. In the early eighteenth century, the dynasty’s fortunes were in decline and the political future of southern Lebanon, uncertain. The major Arab cities of the Empire such as Cairo, Aleppo, Damascus, Tunis, and Algiers – overall grew and prospered in the period between the crises of the early seventeenth and the late eighteenth century, notwithstanding the inevitable occurrence.15 Damascus held the prestige both for

having once served as Islam's capital under the Umayyad (681±750) and as the principal starting point for the annual pilgrimage caravan to the holy city of Mecca. It would be reasonable, therefore, for the sultans to recognize Damascus's regional position by naming its governor as the paramount governor of Syria. But events would prove that decision short sighted.16 The economy of Damascus flourished in the eighteenth century, but this prosperity

was not total and not everyone shared in it equally. It was never able to play the same role that Aleppo had once played in regional trade because it was always susceptible to the depredations of the Bedouin. They attacked the hajj caravans, but also, the trade caravans bringing goods from Mount Lebanon and the Biqaʿ to Damascus. Caravans from as far away as Palestine and Basra were also subject to raids.17 So it was in a less favorable position than Aleppo or Cairo.

11 In August 1516 the Ottoman Sultan Selim I defeated the Mamluk on the plain of Marj Dabiq, near Aleppo, and

quickly conquered Syria. Then he swept quickly through the Levant, taking Aleppo (August 28), Hama (September 19), and Damascus (September 27), in each case being welcomed by the local populations and governors Donald E. Pitcher, An Historical Geography of the Ottoman Empire: From earliest times to the end of sixteenth century (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1972) 105, Stanford J. Shaw and Ezel K. Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and modern Turkey: The rise of modern Turkey, 1808-1975 / Stanford J. Shaw, Ezel Kural Shaw (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977) 84 Amnon Cohen et al., The Ottoman Middle East: Studies in honor of Amnon Cohen / edited by Eyal Ginio and Elie Podeh (The Ottoman Empire and its heritage; VOLUME 55) 93

12 The boundaries of the elayets were not stable, such that, for example, in the eighteenth century the district of

Jerusalem was for some time removed from the province of Damascus and put under the direct authority of the Sublime Porte. At the head of each province was the beylerbey (governor, Arabic wali) with the title of pasha. To prevent separatist tendencies, pashas were changed quite often, so they were in a hurry to squeeze as much money as they could out of their province as soon as possible. The pasha had broad military and administrative powers, having under his command the local administrative apparatus and armed forces. The rulers of sanjaks, sanjak-beys, enjoyed much the same absolute authority over their own territories.

13 Kafescioglu (1999, p 70)

14 PHILIP K. HITTI, Syria: A Short History (New York: MacMillan & Co Ltd, 1959) 221

15 From the perspective of the Ottoman provinces, André Raymond has attempted to show this. Khaled

El-Rouayheb, “Islamic Intellectual History in the Seventeenth Century,”

16 Edhem Eldem, Daniel Goffman and Bruce A. Masters, The Ottoman City between East and West: Aleppo, Izmir,

and Istanbul / Edhem Eldem, Daniel Goffman, and Bruce Masters (Cambridge studies in Islamic civilization, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999) 21

17 Mohannad al-Mubaidin, Aspects of the Economic History of Damascus during the First Half of the Eighteenth

Century: Syria and Bilad al-Sham under Ottoman Rule Essays in honour of Abdul Karim Rafeq, eds. Peter Sluglett, Stefan Weber, 43 v, Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2010 (ed.Peter Sluglett and Stefan Weber; 43 v; The Ottoman Empire and its heritage politics, society and economy; Leiden: Brill, 2010), at 146

27

At a distance from the great land and sea trade routes, Damascus had no easy access to the Mediterranean and had no extensive “hinterland.” Nevertheless, the city turned to its advantage the ottoman occupation, which led, as we have already seen, to considerable development of the pilgrimage, with Damascus as one of its rallying centers.18 The local families such as the

alʿAzm family can take much of the credit for implementing these reforms effectively: by encouraging some economic practices and discouraging others, they reversed the negative economic trends that had set in earlier.19 The province of Damascus was controlled for much

of the eighteenth century by the al-‘Azm household, whose members benefited financially from the office of governor. But, as the Iranian silk trade contracted, Damascus lost importance to the province of Sidon and its commercial port of Acre, where Sheikh Dahir al- ‘Umar held sway from the 1740s.20 In the nineteenth century it was an important trading, manufacturing

and agricultural center. Damascene merchants traded with other Ottoman regions such as Aleppo, Iraq, the Hejaz, Palestine and Egypt. The finer Damascene products, especially textiles, found markets in these major Ottoman cities. Damascus's agricultural hinterland fed not only the local population but also provided surpluses for provisioning the pilgrimage caravan that departed annually from Damascus for Mecca.21 Damascus was the point of

departure for the annual pilgrimage caravan, whose regular success was decisive for the legitimacy of Ottoman rule. Aleppo remained the commercial hub for all trade coming from Iran and eastern Anatolia in addition to the Hejaz and much of Europe. Bilād al Shām was the nexus for all the other Arab regions under Ottoman rule.22

Aleppo became the capital of a wilyet, which corresponded to the niyba of the Mamluks and whose governors had the rank of mrimrn.23 Thus, it has converted from border city into central

city.24 It remained as such during the Ottoman period under a domination of Ottomans. For a

good part of this period it was, regarding population and economic activity, the third city of the Empire after Istanbul and Cairo. Conquest of a trading city like Aleppo, allowed the Ottoman state to expand its options for commercial control and exploitation and to limit the options of its competitors.25Aleppo was an Ottoman city. It had its part in a project for developing the

sultan’s power, being integrated within a particular model of territorial and political

18 André Raymond, the Ottoman conquest and the Development of the Great Arab twons: Arab cities in the

Ottoman period Cairo, Syria, and the Maghreb, Aldershot Hampshire Great Britain, Burlington Vt: Ashgate/Variorum, 2002 (Aldershot Hampshire Great Britain: Ashgate/Variorum, 2002), at 27

19 Al-Mubaidin, Aspects of the Economic History of Damascus during the First Half of the Eighteenth Century

(as in note 17), at 153

20 Caroline Finkel, Osman's dream: The story of the Ottoman Empire 1300-1923 / Caroline Finkel (London: John

Murray, 2005 (2006 printing)) 9912-9913

21 James A. Reilly, “Women in the Economic Life of Late-Ottoman Damascus,” Arabica 42 (1995) 79–106, at 79 22 Thomas Philipp, “Bilād al-Šām in the Modern Period: Integration into the Ottoman Empire and New Relations

with Europe,” Arabica 51 (2004) 401–18, at 407

23 C. E. Bosworth, Historic Cities of the Islamic World (Brill, 2007) 10

24 Jean Sauvaget, Alep: Essai sur le développement d'une grande ville syrienne, des origines au milieu du XIXe

siècle. Texte (P. Geuthner, 1941) 210–11

25 Palmira J. Brummett, Ottoman seapower and Levantine diplomacy in the age of discovery (SUNY series in the

28

organization.26At the start of the seventeenth century two major challenges to Aleppo's

prosperity emerged; the first was locally based, brought on by the rebellion of the Kurdish chieftain Ali Janbulad.27 The second was unleashed by Shah Abbas (1587±1629) who sought

to divert Iranian silk away from the Ottoman Empire, his ideological enemy.28 In 1639, al Zai’m

had welcomed sultan Murat in Aleppo.29

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, changes took place in the central government in Istanbul, where the influence of the Sultan family shifted to a group of senior civil servants in the prime minister's offices or around them. There were Arab and Persian persons in this group as well as Turkish. The second change was the emergence of local ruling groups in the regional capitals that managed to control and use the tax resources of the provinces to form their own army. This was the situation in most states, including Anatolia and Europe, except for those that were easily accessible from Constantinople and nearly through to the Arab states. Aleppo remained under direct control, while in Damascus and Mosul some local families began to gain control during later generations.30

During the eighteenth-century Aleppo experienced much upheaval. Violent factional strife, bitter religious disputes, economic crises, and a succession of frightful famines and plagues left few people unaffected.31 Aleppo, like most of main cities of Bilād al Shām; Tripoli, Homs,

Hama and Damascus, was controlled by the Al-ʿAzm family from 1724-1804. Thus, Bilād al Shām was ruled by this family.32 More than Damascus, Aleppo was characterized by diversity,

by tolerance and by a cross-fertilization of cultures; its inclination to all forms of exchange went beyond that of most other cities in the Empire and marked out its destiny.33

Out of the chaos, Dahir al- ‘Umar, who had started off as a tax-farmer for the Ottomans in the Galilee, rallied his Sunni kinsmen of the Ziyadina clan to exert control over the disparate Druze and Mitwalli Shia clans of Mount ‘Amel in modern south Lebanon. By the middle of the century, he could openly defied both Damascus and Istanbul.34 The Ottoman authorities

developed complicated relations with the ruler of Safad, Sheikh Dahir al-ʿUmar. In 1740, the sheikh of Galilee extended his rule over the northern part of the Palestinian coast. Under his

26 Jean-Claude David, Aleppo: from the Ottoman Metropolis to the Syrian City (ed. Attilio Petruccioli et al; The

City in the Islamic World; Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East v. 94, Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2008) 329–56, at 330

27 Members of the Janbulad family had served as hereditary governors of Kilis since 1571. In 1603, a member of

the family, Huseyn Janbulad, had, by force of arms, established himself as Ottoman Governor-General of Aleppo. Two years later, when Jigalazade Sinan Pasha had ordered him to serve on the Iranian campaign, he stayed in Aleppo. Colin Imber, The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1650: The structure of power / Colin Imber (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002) 74

28 Eldem, Goffman and Masters, The Ottoman City between East and West, 29–30

29 سايلا فيزوج ،ةلاحك , ميعزلا سويراكم كريرطبلا : هتافلؤم هتايح هرصع (trans. فيزوج بﻻا رشنو دادعاو يجزاي سلوب نارطملا ميدقت وباﺷ , ﺐﻠح : ةينايرسلا ةبتكملا , 2007) 57

30 M. Ruthven and A. Hourani, A History of the Arab Peoples: Updated Edition (Faber & Faber, 2013) 313–14 31 Abraham Marcus, “international journal of Iddle east studies: privacy in eighteenth-century Aleppo,” 18 (1986),

167.

32 Nābulusī (1999, p 364)

33 David, Aleppo: From The Ottoman Metropolis To The Syrian City, 330 34 Masters, Semi-autonomous forces in the Arab provinces, 195