Semiotica 2014; 201: 35 – 58

Maurizio Gotti

Adopting and adapting an international

model law in a multilingual and

multicultural context

Abstract: This paper analyses the adoption of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Inter-national Commercial Arbitration issued by the United Nations in 1985 (and later integrated into the laws of several countries with varying constitutional, socio- cultural, and economic conditions) and its connected Arbitration Rules, in order to highlight the adaptations carried out in its “localization” process. In particular, the paper investigates the influence of the socio-economic environment in which the legal norms were introduced on the style adopted in drafting the texts. The examples are drawn from the norms enacted by Parliaments and arbitration chambers in various countries, whose texts show discrepancies due to different drafting traditions, legal contexts, linguistic specificities, and socio-cultural con-straints. The analysis shows that, in spite of the growing efforts of the interna-tional community to guarantee greater and greater harmonization in legislation and procedures, specific linguistic and cultural aspects as well as local and social constraints still are a relevant conditioning factor.

Keywords: Model Law; International Commercial Arbitration; Arbitration Rules; localization; harmonization; globalization

DOI 10.1515/sem-2014-0025

1 Globalizing trends in legal contexts

The last few decades have witnessed great developments in co-operation and col-laboration at an international level in all fields, but particularly in the business and communication sectors, as part of a continuous process of economic global-ization. This process of globalization offers a topical illustration of the interaction between linguistic and cultural factors in the construction of discourse, both within specialized domains and in wider contexts (Candlin and Gotti 2004, 2007). This globalizing trend has also affected the legal field, where an international perspective is becoming more and more widespread (Gotti and Williams 2010a, Maurizio Gotti: University of Bergamo. E-mail: [email protected]

36

Maurizio Gotti

2010b). Indeed, legal discourse – which used to be employed in narrow profes-sional and local milieus and thus more closely geared to specific cultural values and identity systems – is now more and more frequently involved in globalization processes, which have relevant consequences on the discourse produced by both native and non-native practitioners working in intercultural and cross- cultural settings (Williams 2007).

Nowadays many of the texts in use at a local level are the result of a process of translation or adaptation of more general documents formulated at an interna-tional level. This is the consequence of the fact that in the context of co-operation and collaboration in international trade, law too is fast assuming an international perspective rather than remaining a purely domestic concern. The increasing re-quest at an international level for accurate and authoritative translation of legal texts and documents across languages relies on the need for them to convey ap-propriately in both languages the pragmatic and functional intentions and impli-cations of the original text (Šarčević 2000; Gotti and Šarčević 2006). However, legal terminology is so culture-bound (the reasons being at the same time histor-ical, sociologhistor-ical, polithistor-ical, and jurisprudential) that a satisfactory translation of all the legal terms of one text from one context to another is at times impossible. David underlines this difficulty with a few examples:

To translate into English technical words used by lawyers in France, in Spain, or in Germany is in many cases an impossible task, and conversely there are no words in the languages of the continent to express the most elementary notions of English law. The words common law and equity are the best examples thereof; we have to keep the English words . . . because no words in French or in any other language are adequate to convey the meaning of these words, clearly linked as they are to the specific history of English law alone. (David 1980: 39) An excellent example of the globalizing process taking place in the legal system is constituted by international commercial arbitration. In the last few decades, all over the world arbitration has become more and more common as a legal instru-ment for the settling of commercial disputes. The very wide acceptance of this adjudging procedure has been promoted by the growing internationalization of commercial exchanges and by the many advantages that arbitration offers com-pared to litigation (Bernstein and Wood 1993; Sanders 1999). The high recourse to this procedure has given rise to a widely felt need for greater harmonization of the procedures followed,1 which has led to the elaboration of the UNCITRAL

docu-ment approved by the United Nations in 1985 to be used as a model by most of the 1 Indeed, in this process of harmonisation, arbitration has taken an early leading role, as “his-torically, [this process] is one of the earliest examples of an attempt to adapt independent na-tional legal systems to the relentless progress of internana-tional commerce” (Cremades 1998: 158).

Adapting an international model law

37 member countries in the construction of their own individual statutory provi-sions for commercial arbitration. In the last three decades the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) provisions have been used as a model by a large number of countries.2 As the Model Law and its connected

arbitration rules were created with the purpose of achieving the highest degree of harmonization, the single countries have been recommended to make as few changes as possible when incorporating them into their legal systems. However, in spite of the growing globalization of arbitration culture, the elaboration of the UN Model Law has not guaranteed complete uniformity among the various na-tional legislations, as the different countries have used this model in different ways, depending upon their national requirements, concerns, cultures, legal sys-tems, languages, and other constraints. Indeed, in the process of adoption of this model, the English language text of the UNCITRAL has often had to be translated into the local languages, a procedure that has implied not only the adaptation of the original discourse to the typical features and resources of the national tongues, but also its adjustment to the cultural needs and legal constraints of each specific country.

2 Customizing the model law

It is the aim of this paper to analyze the text of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Inter-national Commercial Arbitration (ML)3 issued by the United Nations in 1985 (and

later integrated into the laws of several countries with varying constitutional, sociocultural and economic conditions) and its connected Arbitration Rules (AR),4 in order to investigate the main adaptations that have been made to the

model documents in the process of adaptation of these texts to various local en-vironments, and to identify the criteria that have determined such diverging 2 Legislation based on the UNCITRAL text has been enacted in many countries, such as Austra-lia, Bahrain, Belarus, Bermuda, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Egypt, Germany, Greece, Guatemala, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China, Hungary, India, Iran, Ireland, Kenya, Lithuania, Macau Special Administrative Region of China, Madagascar, Malta, Mexico, New Zealand, Nigeria, Oman, Peru, Republic of Korea, Russia, Scotland, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Tunisia, Ukraine, Zimbabwe, and some of the states in the U.S. (California, Connecticut, Florida, Oregon, and Texas).

3 The text of the UNCITRAL Model Law (United Nations document A/40/17, Annex I) is avail-able on line at http://www.uncitral.org/uncitral/en/uncitral_texts/arbitration/1985Model_ arbitration.html (accessed 27 April 2014).

4 The text of the Arbitration Rules is available at http://www.uncitral.org/pdf/english/texts/ arbitration/arb-rules/arb-rules.pdf (accessed 27 April 2014).

38

Maurizio Gotti

outcomes. Although examples will be taken from arbitration laws and rules in use in various countries, the main texts analyzed here will be drawn from Italian legislation on international arbitration based on ML and AR; in particular, the analysis will focus on the Italian arbitration law inserted in the Code of Civil Pro-cedure (CCP, arts. 806–840)5 and the regulations drafted by the arbitration

cham-bers of Milan, Bergamo, and Venice.6 In order to highlight the differentiations and

adaptations to a particular context, the local documents taken into consideration will be compared to those of the United Nations, with the aim of offering a more detailed understanding of linguistic and textual phenomena closely linked to cross-cultural traits.

The analysis presented in this paper is based on the results of an international research project entitled Generic Integrity in Legislative Discourse in Multilingual

and Multicultural Contexts7 and led by professor Vijay Bhatia of the City

Univer-sity of Hong Kong. The project has investigated the generic integrity of legislative discourse by analyzing the linguistic and discoursal properties of a multilingual corpus of international arbitration laws drawn from a number of different coun-tries, cultures, and socio-political backgrounds, written in different languages, and used within and across a variety of legal systems. Some of the results of the project are presented in Bhatia, Candlin, and Gotti (2003, 2010), and Bhatia, Candlin, and Engberg (2008). The project has highlighted a three-part investiga-tion of internainvestiga-tional arbitrainvestiga-tion laws:

1. Linguistic analyses of international arbitration laws from a number of coun-tries addressing such issues as degree of qualification, specification of scope, issues of closed- versus open-endedness, and other matters concerned with complex contingency, and their comparison with the UNCITRAL Model Law provided by the United Nations.

5 More specifically, articles 806–831 constitute the legislative and procedural framework for ar-bitration per se, while 832–840 contain special provisions for international controversies. The text of CCP is available at http://www.altalex.com/?idnot=33723 (accessed 27 April 2014); an English translation, offered by the Milan Chamber of National and International Arbitration, is available at http://ebookbrowsee.net/italian-code-of-civil-procedure-pdf-d94480448 (accessed 27 April 2014); it is the version referred to in this article.

6 The texts taken into consideration are: the regulations enacted by the Milan Arbitration Chamber (MAC, available at http://www.camera-arbitrale.it/en/Arbitration/Arbitration+Rules. php?id=64 [accessed 27 April 2014]), the regulations enacted by the Bergamo Arbitration Cham-ber (BAC, available at http://www.bg.camcom.gov.it/ [accessed 27 April 2014]), and the regula-tions enacted by the Venice Arbitration Chamber (VAC, available at http://www.camera- arbitrale-venezia.com/?language=en [accessed 27 April 2014]).

Adapting an international model law

39 2. Documented accounts of the drafting and interpretative practices within spe-cific contexts, exploring the issues arising from such analyses by focusing on a set of critical cases incorporating relevant moments of application of the laws under investigation.

3. Explanation of issues identified and discussed under 1 and 2 above, by refer-ence to socio-cultural, economic and political, linguistic and legal factors based on the background studies of the legal systems of these countries, and also on the reactions of and commentaries by legal experts, both from aca-demic circles and legal practice.

In order to make comparison easier and more consistent, the project has focused on a very specific, narrowly defined, internationally relevant and limited area of law, i.e., international commercial arbitration, which was identified as a suitable area for this purpose by the participating legal experts working on the project. Preliminary attempts to collect and analyze data confirmed our initial percep-tions about the suitability and adequacy of such a focus. Some of the more specific advantages were the following:

– It was an internationally useful and relevant area, where an existing United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) had approved a Model Law on international commercial arbitration, which was being used as a model by most of the member countries to produce their own individual statutory provisions for commercial arbitration.

– It was evident from a preliminary investigation that different countries had used this model in different ways, depending upon their national require-ments, concerns, cultures, legal systems, languages, and other constraints. – In most cases, both this particular statutory provision available in English

and the national language text were easily accessible on the Internet. In terms of length, these texts were neither very long nor very short, and there-fore manageable for analytical purposes.

– There were sufficient cases in each country to provide critical moments in the application of some of the crucial aspects of the provision, and these were likely to raise relevant issues for comparative work.

3 Drafting traditions

Important elements of a particular legal system are its drafting tradition and sty-listic conventions (cf. Bhatia, Candlin, and Evangelisti Allori 2008). These may

40

Maurizio Gotti

influence arbitration discourse significantly, as can be seen in the differentiation between civil law and common law texts: the former are mainly characterized by generality, while the latter prefer particularity. Indeed, it is commonly asserted that civil law statutes are written in terms of principle, whereas common law statutes are written in detail as “the civil code draftsman is eager to be widely understood by the ordinary readership, whereas the common law draftsman seems to be more worried about not being misunderstood by the specialist com-munity” (Bhatia 1993: 137). This conceptual differentiation is reflected in the drafters’ stylistic choices: in common law legislation sentences are very long, consisting of three or more main clauses, each modified by many subordinate clauses; this remarkable sentence length depends on the great number of details to be inserted and the need that specifications should be precise and clear (Gustafsson 1975; Tiersma 1999; Gotti 2011). Civil law sentences are shorter, with a less strict use of paragraphing; this makes the understanding of the sentences easier, but renders the reconstruction of the relationship between the various sentences more complex.

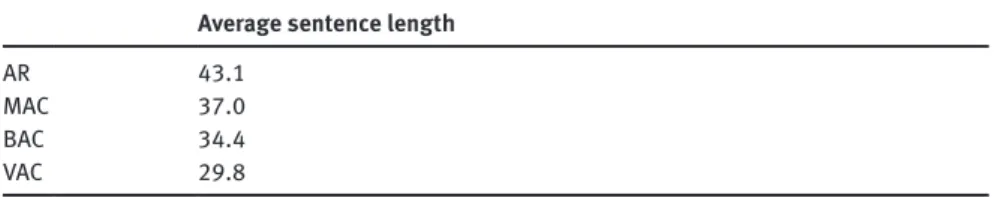

The adherence of the UNCITRAL texts to a more traditional legal style is demonstrated by the lengthy and complex structure of most of its sentences. As can be seen in Table 1, the average sentence length is greater in AR than in the other three texts that – although written in English – are part of the civil law system:

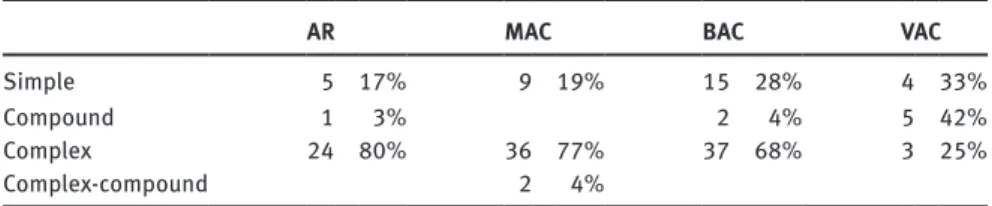

The reason for this discrepancy lies in the fact that the UNCITRAL text tends to include all possible information in a single sentence, thus increasing the density of information. The more complex structure of legal discourse in these texts is confirmed by the data concerning sentence types. As Table 2 shows, AR has more complex sentences than the Italian texts; MAC, BAC, and VAC, on the contrary, contain more simple and compound sentences.

Table 1: Average sentence length in the corpus analyzed (from Belotti 2003: 33)

Average sentence length

AR 43.1

MAC 37.0

BAC 34.4

Adapting an international model law

41

An example of this complexity may be seen in the following sentence taken from the Model Law, which consists of four subordinate clauses and three coordinated clauses.

(1) The court or other authority, in appointing an arbitrator, shall have due re-gard to any qualifications required of the arbitrator by the agreement of the parties and to such considerations as are likely to secure the appointment of an independent and impartial arbitrator and, in the case of a sole or third arbitrator, shall take into account as well the advisability of appointing an arbitrator of a nationality other than those of the parties. (ML 11.5)

The longer sentence length of the UNCITRAL texts is also favored by their stricter adherence to the tradition of English legal language (Gustafsson 1984), as can be seen in the frequent use of binomial expressions, such as the crystallized forms

ex aequo et bono and null and void, and the free collocations independent and impartial arbitrator and documents and other materials. Moreover, common law

legislation is usually associated with particular emphasis on precision and detail for action to be taken in specific circumstances (Campbell 1996). This explains why various parts of the Model Law are devoted to detailed terminological expla-nations and use past-participle clauses to state clearly the source of the qualifica-tion of a term, as can be seen in the following example:

(2) Where an action referred to in paragraph (1) of this article has been brought, arbitral proceedings may nevertheless be commenced or continued, and an award may be made, while the issue is pending before the court. (ML 8.2, emphasis added, as in all citations in this paper)

These forms also appear in civil law texts, but in general there is less emphasis on precision. In the Italian text, for example, there are also cases in which the link remains implicit or refers vaguely to “law” in general:

Table 2: Distribution of sentence types (from Belotti 2003: 34)

AR MAC BAC VAC

Simple 5 17% 9 19% 15 28% 4 33%

Compound 1 3% 2 4% 5 42%

Complex 24 80% 36 77% 37 68% 3 25%

42

Maurizio Gotti

(3) Gli arbitri debbono pronunciare il lodo entro il termine stabilito . . . dalla

legge; (CCP 813)

[‘The arbitrators shall render their award within the time limit set . . . by

law;’]

The great importance attributed to precision in common law legislation can also be seen in the detailed definitions provided in the Model Law:

(4) “Arbitration agreement” is an agreement by the parties to submit to arbitra-tion all or certain disputes which have arisen or which may arise between them in respect of a defined legal relationship, whether contractual or not. An arbi-tration agreement may be in the form of an arbiarbi-tration clause in a contract or

in the form of a separate agreement. (ML 7.1)

Instead, as Chroma (2003) points out, the Czech Arbitration Act fails to provide a descriptive definition of arbitration as a type of extra-judicial settlement of dis-putes; on the other hand, a definition by implication (Sager 1990: 43) is chosen. As can be seen in the following quotation, the notion of arbitration is presup-posed in the use of the two legal terms “arbitrator” and “arbitral award” that, in a legal context, have concrete, generally accepted legal meanings denoting a person acting in a quasi-judicial office and a type of decision respectively: (5) Toto ustanovení obecně vymezuje základní cíle zákona, jimiž je jednak právní

úprava rozhodování majetkových sporů rozhodci, jednak právní úprava výkonu rozhodčích nálezů vydaných rozhodci. Zdůrazňuje se postavení rozhodců jako osob nezávislých a nestranných; jde o jeden ze základních předpokladů jejich rozhodovací činnosti.

[‘This provision generally defines the main purposes of the Act, namely to regulate the deciding of property disputes by arbitrators on the one hand, and the enforcement of arbitral awards issued by arbitrators on the other. The position of arbitrators as independent and impartial persons is emphasized; this is one of the fundamental pre-conditions of their decision-making ac-tivity.’] (Chroma 2003: 77)

Another relevant aspect of the common law legal drafting tradition is the use of coordination to provide a great degree of textual cohesion. The UNCITRAL texts frequently use and/or to express both parallel and alternative coordination, as can be seen in the frequent use of multinomials joined by alternative / complementary coordination:

Adapting an international model law

43 (6) Any dispute, controversy or claim arising out of or relating to this contract, or

the breach, termination or invalidity thereof, shall be settled by arbitration in accordance with the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules as at present in force. (AR 1) Also a civil law text such as the CCP uses similar expressions, but mainly with parallel coordination; indeed, the two texts have a comparable amount of paral-lel coordination (with 55 e(d) in the CCP, 59 and in the ML), while alternative co-ordination is considerably more frequent in the UNCITRAL text, with 172 occur-rences of or as compared to 70 of o/oppure (Giannoni 2003: 231). The pervasiveness in ML of this second type of binomial is particularly evident inasmuch as it links whole paragraphs rather than single words. Alternative / complementary options with or are frequently used in the UNCITRAL text. The way in which they are usually punctuated and set out emphasizes their function of making the provisions both more inclusive and semantically transparent. Here is a particularly striking example: (7) Grounds for refusing recognition or enforcement

(1) Recognition or enforcement of an arbitral award, irrespective of the coun-try in which it was made, may be refused only:

(a) at the request of the party against whom it is invoked, if that party furnishes to the competent court where recognition or enforcement is sought proof that:

(i) a party to the arbitration agreement referred to in article 7 was under some incapacity; or the said agreement is not valid under the law to which the parties have subjected it or, failing any indi-cation thereon, under the law of the country where the award was made; or

(ii) the party against whom the award is invoked was not given proper notice of the appointment of an arbitrator or of the arbitral proceedings or was otherwise unable to present his case; or (iii) the award deals with a dispute not contemplated by or not falling

within the terms of the submission to arbitration, or it contains decisions on matters beyond the scope of the submission to arbi-tration, provided that, if the decisions on matters submitted to arbitration can be separated from those not so submitted, that part of the award which contains decisions on matters submitted to arbitration may be recognized and enforced; or

(iv) the composition of the arbitral tribunal or the arbitral procedure was not in accordance with the agreement of the parties or, fail-ing such agreement, was not in accordance with the law of the country where the arbitration took place; or

44

Maurizio Gotti

(v) the award has not yet become binding on the parties or has been set aside or suspended by a court of the country in which, or

under the law of which, that award was made; or

(b) if the court finds that:

(i) the subject-matter of the dispute is not capable of settlement by arbitration under the law of this State; or

(ii) the recognition or enforcement of the award would be contrary to the public policy of this State. (ML 36)

By arranging the content schematically, the drafter can construct a denser, more cognitively demanding text such as the one cited above. This pattern is followed also by other drafting systems such as the Danish one, where the alternative or cumulative relationship between textual parts may be emphasized by the use of the conjunctions eller/og [‘or/and’] either after every item in the tabulation or only before the last one. For example, in quotation 8 the conjunction og [‘and’] is used before the last tabulated item:

(8) 1. En voldgiftaftales parter kan bestemme:

a) at deres tvister skal afgøres ved en voldgiftsinstitution . . . ;

b) at deres tvister skal afgøres ved ad hoc voldgift; i så fald kan parterne bl.a.

1) udpege voldgiftsmændene . . . ; 2) bestemme stedet for voldgiften; og

3) fastsætte, hvilke procedureregler voldgiftsmændene skal anvende. [‘1. The parties to an arbitration agreement shall be free to decide:

a) that their disputes shall be submitted to a permanent arbitral institution . . . ;

b) that their disputes shall be submitted to an ad hoc arbitral procedure; in this case, they shall be free inter alia

1) to appoint arbitrators . . . ;

2) to determine the place of arbitration; and

3) to lay down the procedure to be followed by the arbitrators.’] (Engberg and Rasmussen 2003: 132)

Instead, the prevailing pattern in Italian is simply coordination with or at word level:

(9) La parte che intende far eseguire il lodo nel territorio della Repubblica è tenuta a depositarlo in originale o in copia conforme, insieme con l’atto di compro-messo o con l’atto contenente la clausola compromissoria o con documento

Adapting an international model law

45 equipollente, in originale o in copia conforme, nella cancelleria della pretura nella cui circoscrizione è la sede dell’arbitrato.

[‘The party intending to have the award enforced in the territory of the Repub-lic shall file the original award or a certified copy thereof, together with the original arbitration agreement or document containing the arbitration clause

or an equivalent document, or a certified copy thereof, with the Registry of the

Magistrate’s Court [Pretura] of the district in which the arbitrator has its seat’] (CCP 825.2)

4 Legal context

Although the coverage of the contents of both ML and CCP is very similar – mainly following the chronological progression from the drafting of a commercial con-tract to the eventual recourse against the award – the Italian law is more compre-hensive, as it deals both with national and international arbitration, while the Model Law does not apply to domestic controversies. Moreover, the Italian text displays a high degree of intertextual linking as this new law is embedded in the extant body of legislation, and therefore has to be interpreted in the light of hundreds of other texts of greater or equal authority. The sources of some of these references are explicitly mentioned in the text (cf. quotation 10 below), but in other cases the links to other documents remain implicit, as in quotation 11, where references to other parts of the Civil Code (c.c.) or Penal Code (c.p.) are given in brackets:

(10) La clausola compromissoria contenuta in condizioni generali di contratto oppure in moduli o formulari non è soggetta alla approvazione specifica pre-vista dagli artt. 1341 e 1342 del Codice civile.

[‘An arbitration clause contained in general conditions of contract or stan-dard forms shall not be subject to the specific approval provided for in Arts.

1341 and 1342 of the Civil Code’] (CCP 833.1)

(11) Gli arbitri possono essere sia cittadini italiani sia stranieri. Non possono essere arbitri i minori (c.c. 2), gli interdetti (c.c. 414; c.p. 32), gli inabilitati (c.c. 415), i falliti, e coloro che sono sottoposti a interdizione dai pubblici uffici (829 n. 3; c.p. 28, 23, 31.).

[‘The arbitrators may be Italian or foreign nationals. Minors (c.c. 2), persons under a legal incapacity (c.c. 414, 415; c.p. 32), bankrupts and those who have been disqualified from holding a public office (829 n. 3; c.p. 28, 23, 31) may not act as arbitrators’] (CCP 812)

46

Maurizio Gotti

In ML, instead, reference is usually internal and has the function of facilitating “textual mapping” (Bhatia 1987). This is achieved mainly through the use of com-plex prepositional phrases, such as under, in accordance with or according to: (12) The award shall state the reasons upon which it is based, unless the parties

have agreed that no reasons are to be given or the award is an award on agreed terms under article 30. The award shall state its date and the place of arbitration as determined in accordance with article 20(1). (ML 31.2–3) Other typical realizations include en-participle clauses such as to and specified in: (13) any party may request the court or other authority specified in article 6 to

take the necessary measure, unless the agreement on the appointment pro-cedure provides other means for securing the appointment. (ML 11.4) Intra-textual links also occur in CCP, as can be seen in the following case: (14) La clausola compromissoria deve risultare da atto avente la forma richiesta

per il compromesso ai sensi dell’articolo 807, commi primo e secondo. (CCP 808.1)

[‘The arbiration clause shall be contained in a document meeting the formal requirements for an arbitration agreement according to Art. 807, first and second paragraphs’]

However, these devices are less frequent in the Italian text, this being probably linked to the fact that this law is firmly embedded within the Code of Civil Proce-dure and its authority, whereas ML is a stand-alone law with no inherent inter-textual linking.

Another interesting case where the legal context becomes apparent is in the specific labels employed in the Scottish Arbitration Code (SAC) compared to the Model Law (Dossena 2003). While for article 2 of the Model Law “‘arbitral tribu-nal’ means a sole arbitrator or a panel of arbitrators,” in article 2 of the SAC we find the specification that “(b) ‘arbitral tribunal’ means an arbitrator or a panel of arbitrators; (c) ‘arbitrator’ includes an arbiter.” The distinction between arbiter and arbitrator was indeed an older one: while the “arbiter” was appointed for legalistic forms of arbitration, the “arbitrator” was appointed for equitable forms (Hunter 2002: 14, 43). This is therefore one of those cases in which national laws and codes rely on cultural specificity to integrate provisions.

A further example of how the linguistic manifestation conforms to the legal context can be seen in the level of detail with which a specific norm is formulated.

Adapting an international model law

47 Indeed, the need to lay down rules varies according to national legal order. For instance, in contrast with the UNCITRAL Model Law and other national laws on arbitration (such as the Finnish Arbitration Act), Sweden has included no provisions concerning the form of the arbitration agreement in its legislation (Salmi-Tolonen 2003).

Influence of the legal context may also be seen in the degree of strength of the obligation imposed by a specific norm. For instance, article 5 (“Court inter-vention”) of the UNCITRAL Model Law provides that “In matters governed by this Law, no court shall intervene except where so provided in this Law.” In the English Arbitration Act (s. 1) the modal shall was replaced with should. The reason for the change was explained as follows:

In earlier drafts [of the English Arbitration Act] Article 5 of the Model Law had been repro-duced verbatim, but this was then changed, given that it had the effect of sweeping aside the entirety of the court’s inherent jurisdiction. This was considered undesirable . . . It is not, however, envisaged that the court will have any real opportunity of exercising inherent powers, and certainly not in order to alter any of the areas covered by the Act where the powers are carefully delimited. (Landau 1996, quoted in Tessuto 2003: 356)

5 Linguistic conventions

The analysis of arbitration texts has also shown examples of discrepancy due to variations in linguistic conventions. This can be seen, for example, in the way juridical obligation is signaled. This concept is traditionally expressed by modal

shall in the UNCITRAL texts, as is customary in English legal discourse.

(15) An arbitral award, irrespective of the country in which it was made, shall be recognized as binding and, upon, application in writing to the competent court, shall be enforced subject to the provisions of this article and of article 36. (ML 35)

(16) The appointing authority shall, at the request of one of the parties, appoint the sole arbitrator as promptly as possible. In making the appointment the appointing authority shall use the following list-procedure, unless both par-ties agree that the list-procedure should not be used or unless the appoint-ing authority determines in its discretion that the use of the list-procedure is not appropriate for the case: . . . (AR 6.3)

Italian legal discourse, instead, often adopts a present indicative to state legal pro-visions, thus emphasizing the actuality and applicability of the legal provision and

48

Maurizio Gotti

also implying that the law draws its force from the natural order of things rather than an order imposed by human agents. This tense is frequently used also in the regulations of Italian arbitration chambers and arbitral courts written in English:

(17) Gli arbitri, sentite le parti, provvedono entro venti giorni.

[‘The arbitrators take the necessary action within twenty days after hearing the parties.’] (CCP 826.2)

(18) In the event the Parties have not appointed the Arbitrator/s and not desig-nated a different appointing authority within the applicable terms, the arbitrator/s is/are appointed by the Court within 30 (thirty) days from when the Court is noticed by the most diligent Party. (VAC 10)

This preference for the present tense is also part of the drafting tradition of another country belonging to the civil law system, that is, France. As Garzone’s (2003: 206) analysis has shown, the simple present indicative – rather than the deontic modal devoir – is the form customarily used to convey both the prescriptive and the performative functions of normative and legislative texts. The use of the sim-ple present is also common in the Swedish drafting tradition:

(19) För betalning av de i § 39 angivna kostnaderna är parterna solidariskt ansvariga (§ 39)

[‘The parties are jointly and severally liable for all payments of all costs mentioned in Article 39.’] (Garzone 2003: 208)

The faithful observation by the UNCITRAL texts of the linguistic conventions of English legal discourse can also be seen in the choice of lexis. For instance, the Model Law contains archaic or very formal expressions such as agreed upon (for

agreed on), commencement (for beginning), furnish (for produce), notwithstanding

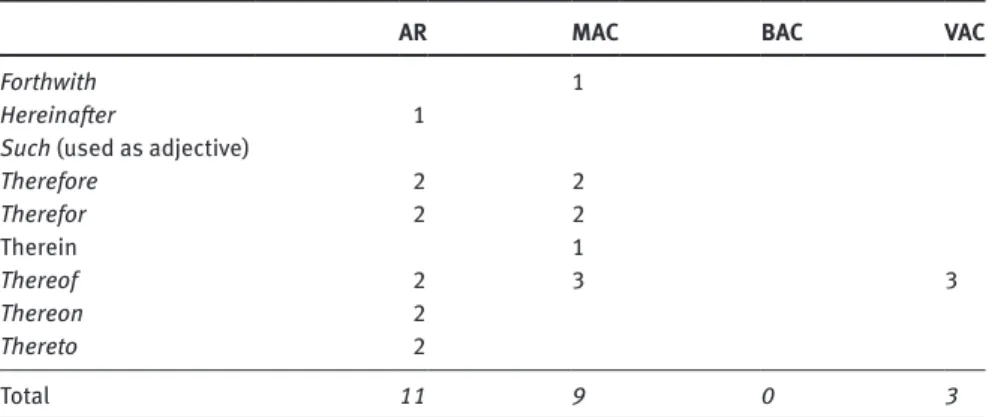

(for regardless of ), and compound forms like thereof, thereon, and thereto, which are typically related to the register of legal writing (Bowers 1989). These texts also include Latin lexical items, such as interi, ipso jure, and de jure or de facto. Also a French expression (amiable compositeur) is present, borrowed from the language of international arbitration. In these texts, Latin expressions are not usually translated or paraphrased, as the target readers’ knowledge of their meaning is taken for granted (indeed, the texts are exclusively aimed at legal experts). Lati-nate and French forms, instead, do not occur at all in some of the Italian arbitra-tion rules (such as BAC) or are very few in others (in MAC and VAC). The same can be said for archaic words, as can be seen in Table 3:

Adapting an international model law

49

The same linguistic policy of avoiding Latinate forms is adopted by the Scottish Arbitration Code, which rephrases Latin expressions into common lexis: e.g. de

jure and de facto, which occur in the Model Law, are rendered as “from the legal

point of view” and “in actual fact,” in order to make their semantic value less opaque to non-expert readers (Dossena 2003: 103).

6 Cultural constraints

Differences in the formulation of arbitral norms may also depend on diverse cul-tural implications involved in dispute resolution. Even from a very superficial analysis of arbitration practices, it is easy to realize that the cultural environment greatly influences the specific provisions on arbitration procedures. This is clearly visible in those cases in which the national legislation imposes specific obliga-tions in compliance with local customs and tradiobliga-tions: for example, some coun-tries such as Korea and Saudi Arabia uphold requirements of nationality and/or residence for a person to serve as arbitrator (Jarvin 1999: 60); Saudi Arabia also requires arbitrators to be male and of the Islamic faith (Saleh 1992: 549). These criteria impose serious restrictions on the choice of arbitration in an international dispute and are usually taken into consideration by foreigners when they have to fix the site of an arbitration case with a party residing in one of those countries. But even when cultural differences are not so evident, it is impossible to guaran-tee a perfectly homogeneous process, as the various legal patterns of the coun-tries involved will re-emerge in some of the procedures described or in a few of the principles set out.

Table 3: Type and number of occurrences of archaic words. (From Belotti 2002: 132)

AR MAC BAC VAC

Forthwith 1

Hereinafter 1

Such (used as adjective)

Therefore 2 2 Therefor 2 2 Therein 1 Thereof 2 3 3 Thereon 2 Thereto 2 Total 11 9 0 3

50

Maurizio Gotti

A relevant case in point can be seen in the comparison of the various clauses concerning the grounds for challenging the appointment of arbitrators: some are expressed in more general terms, while in others the constraints are specified in greater detail. In arbitration proceedings the arbitrator plays a very active role due to the fact that no jury is involved and the majority of the disputes in inter-national commercial arbitration are of a technical and complicated nature. It is important, therefore, that the decision-making process is totally transparent and the arbitrator impartial and independent. This requirement is particularly felt in the Italian context, where the custom of non-standard arbitration has often been regarded as too sensitive to the parties’ interests and pressures (Ceccon 2000), thus providing an explanation for the specific rules laid down by several Italian arbitration chambers to regulate the conduct of appointed arbitrators. In particu-lar, the regulations of a few arbitration chambers contain specific codes of con-duct concerning important issues such as the arbitrator’s competence, impartial-ity and independence, which are largely modelled on the Criteria of Arbitral Ethics (Criteri di Deontologia Arbitrale) enacted by the Italian Arbitration Associ-ation in 1999 (Bartolini and Delconte 2001). The codes of conduct included in MAC and BAC consist of fifteen articles, covering various aspects connected to the problem of arbitrators’ impartiality and independence and regulating the con-duct of arbitrators in a very detailed way, as from the moment they accept the appointment and throughout the entire arbitration procedure. Also VAC has a specific article (Art. 13) stating explicitly that the appointed arbitrator is expected to send a written statement expressing his independence and impartiality and declaring he has no connections with the parties involved in the arbitration pro-cess. Moreover, BAC also includes the need for a Roster of Arbitrators (Section 6) and outlines in detail the characteristics of a potential arbitrator and of the ap-plication procedures. The specification of a Roster of Arbitrators stresses the wish of this arbitration chamber to exercise strict control over the competence and re-liability of prospective arbitrators. Also as regards the procedure for challenging an arbitrator, AR indicates the grounds for challenge in general terms, only men-tioning “justifiable doubts as to his impartiality or independence” (Art.10). BAC (Section 8.1), instead, makes a clear reference to the reasons for challenging an arbitrator and refers to a precise external source of jurisdiction for their specification:

(20) The party may reject the arbitrator in the cases specified in Section 51 of the

Italian Code of Civil Practice. (BAC 8.1.2)

On the other hand, this issue is formulated in very general terms in the UNCITRAL text:

Adapting an international model law

51 (21) In making the appointment, the appointing authority shall have regard to

such considerations as are likely to secure the appointment of an indepen-dent and impartial arbitrator and shall take into account as well the advis-ability of appointing an arbitrator of a nationality other than the nationali-ties of the parnationali-ties. (AR 6.4)

This requirement, instead, is clearly stated as a strict obligation in other texts, with the use of a strong deontic modal auxiliary such as must and the explicit mention of situations that may impair such impartiality:

(22) Every arbitrator must be and remain independent of the parties involved in the arbitration. (Rules of the International Chamber of Commerce Court of Arbitration 7.1)

(23) An arbitrator must be impartial and independent. (Rules of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce 17)

(24) All arbitrators conducting an arbitration under these Rules shall be and

re-main at all times impartial and independent of the parties; and none shall act in the arbitration as advocates for any party. No arbitrator, whether before or

after appointment, shall advise any party on the merits or outcome of the dispute. (Rules of the London Court of International Arbitration 5.2)

In the Arbitration Law of the People’s Republic of China, the grounds for chal-lenging the appointment of arbitrators are also formulated in specific terms, as is illustrated by mentioning a close relationship with “one litigant” or “the attor-ney,” “private meetings with the litigants or with their attorneys” or acceptance of “an invitation of the litigants or their attorneys to dine” or acceptance of “gifts” (Bhatia, Candlin, and Wei 2001: 10). This implication of possible bribery or influ-ence may be prompted by particular socio-cultural factors specific for that coun-try, a hypothesis confirmed by an expert on Chinese law, Professor Jerome Cohen from New York University, as quoted by Jane Moir in an article in the South China

Morning Post (5 October 2001):

The longer my experience as either an advocate or an arbitrator in disputes presented to Cietac [China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission], the graver my doubts have become about its independence and impartiality . . . At a minimum, I would surely no longer advise clients to accept Cietac jurisdiction unless the contract’s arbitration clause required the appointment of a third country national as presiding arbitrator. (cited in Bhatia et al. 2001: 8)

52

Maurizio Gotti

Similar reference to the social context may be seen in the case of the Czech Arbi-tration Act, where the original ten subsections and eleven paragraphs of the Government Bill determining and defining the role of the State in the process of appointment and licensing of arbitrators were reduced to two sections and five subsections in the Act, entirely omitting the State intrusion in the system. The Minister of Justice as the sponsor of the Bill had unsuccessfully defended the interference by the State as follows:

v současných podmínkách transformace nelze zcela akceptovat takovou právní úpravu, podle níž by výběr rozhodců byl v podstatě zcela volný.

[‘under the existing circumstances of transformation of our society it is virtually impossible to fully accept such regulation by which, basically, the selection of arbitrators would be free.’] (Chroma 2003: 78)

The rigidly declared intention of the Government that only an individual who is a Czech citizen, a university graduate without any record of criminal conviction, could become an arbitrator and be included in an official list maintained by the Ministry of Justice, was disapproved by Parliament, thus preventing the State from intervening in the qualification requirements of arbitrators and their selec-tion by parties. Deputy Řezáč (Transcript 1994: 3) concluded the debates pointing out that the Government had intended to revive étatisme8 in arbitration in order

to preserve the State intrusion in private legal relations; he appreciated the fact that the Chamber had accepted the critical comments expressed by the Arbitra-tion Tribunal of the Chamber of Commerce of the Czech Republic thus ensuring the compliance of the arbitration procedure not only with the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration but also with the European Con-vention on International Commercial Arbitration also signed up by the Czech Republic.

Moreover, the Czech Arbitration Act also contains sanctioning provisions and legal consequences in case the arbitrator’s duties should be breached: for exam-ple, s. 11 provides that the arbitrator is excluded from the procedure if he fails to notify the parties of circumstances casting doubt upon his impartiality and inde-pendence. The UNCITRAL Model Law, instead, contains no sanctions and is based only on the Hypothesis / Disposition pattern of legal rules. The hypothesis is a part of a legal rule determining pre-conditions and circumstances under which the rule should be pursued; the disposition determines the rights and duties 8 Etatisme refers to an extreme development of the power of the State over the individual citizen and private relation ships. Etatisme was widely applied in the Czech legal system (including arbi-tration norms) between 1948 and 1990.

Adapting an international model law

53 which occur where the pre-conditions have been fulfilled. A typical example of such a pattern may be Art. 11(4) of the Model Law which reads as follows: (25) H Where, under an appointment procedure agreed upon by the parties,

(a) a party fails to act as required under such procedure, or

(b) the parties, or two arbitrators, are unable to reach an agreement ex-pected of them under such procedure, or

(c) a third party, including an institution, fails to perform any function entrusted to it under such procedure,

D any party may request the court or other authority specified in article 6 to take the necessary measure, unless the agreement on the appointment procedure provides other means for securing the appointment. (Chroma 2003: 84)

In this case, the hypothesis determines three situations preventing the procedure from continuing, and the disposition defines the right the parties may apply if any of the pre-conditions occur.

7 Target readers

The socio-economic environment in which legal provisions are issued has also influenced the style adopted in customizing the UNCITRAL normative texts. An example can be seen in the regulations enacted by the Milan and Bergamo Arbi-tration Chambers and the Venice Court of National and International ArbiArbi-tration. These institutions are situated in one of the most industrialized areas in Northern Italy, where a large number of small enterprises operate successfully on foreign markets. Their sets of rules are intended for a number of business people running small and medium-sized companies and wanting clear indications on how to re-solve commercial disputes without recourse to ordinary justice. This explains the higher degree of user-friendliness encountered in their texts, which can be noted in several cases. One instance is the fact that they include standard arbitration clauses – such as the clauses for a sole arbitrator, for an arbitral tribunal and for a multi-party arbitration – which can be adopted verbatim and completed easily by the reader, as may be seen from the following examples:

(26) Arbitration agreement (a)

The undersigned (b) ... and ... considering that

54

Maurizio Gotti

dispute to the decision of (d) ... to be appointed in

accor-dance with the Rules of the National and International Arbitration Chamber of Bergamo, which the parties expressly declare they know and which they accept in full.

The arbitrators / the sole arbitrator shall decide according to the rules and regulations ... / fairness (specify what is relevant).

The language of the arbitration shall be ...

Notes

(a) The arbitration agreement is a document that is stipulated when the

dis-pute has already arisen between the parties and in the absence of a pre-cautionary arbitration clause.

(b) Specification of the name and residence, or in the case of companies, the

head offices of the parties.

(c) Reference, also expressed in general terms, of the subject under dispute,

with possible reference to the contract out of which the dispute originated.

(d) Specification of the number of arbitrators (one or three). (BAC,

Arbitra-tion agreement) (27) Clause for Sole Arbitrator

All disputes arising out of the present contract (1), including those

concern-ing its validity, interpretation, performance and termination, shall be re-ferred to a sole arbitrator according to the International Arbitration Rules of the Chamber of National and International Arbitration of Milan, which the parties declare that they know and accept in their entirety.

The sole arbitrator shall decide according to the norms . . . (2).

The language of the arbitration shall be . . .

Notes

(1) Where the arbitration clause is contained in a document other than the

contract to which it pertains, the contract referred to shall be indicated.

(2) The parties may indicate the norms applicable to the merits of the

dis-pute; alternatively, they may provide that the arbitrator decide ex aequo et bono. (MAC, Clause for Sole Arbitrator)

The texts above have the form of ready-to-use specimens and are thus very easy to copy and complete. Instead, the UNICITRAL arbitration rules, on which the Italian texts are modelled, are mainly informative and imply some sort of adapta-tion on the part of the user of the clauses presented (cf. quotaadapta-tion 28). This is in line with the results of Salmi-Tolonen’s (2003) analysis of the Finnish Arbitration Act compared with the UNCITRAL Model Law, which confirm her hypothesis that the functions of the national law and the international law are slightly different:

Adapting an international model law

55 expository and descriptive in the case of international law, and directive in the case of national law.

(28) Model arbitration clause

Any dispute, controversy or claim arising out of or relating to this contract, or the breach, termination or invalidity thereof, shall be settled by arbitra-tion in accordance with the UNCITRAL Arbitraarbitra-tion Rules as at present in force.

Note

Parties may wish to consider adding:

(a) The appointing authority shall be . . . (name of institution or person); (b) The number of arbitrators shall be . . . (one or three);

(c) The place of arbitration shall be . . . (town or country);

(d) The language(s) to be used in the arbitral proceedings shall be . . . (AR 1) Moreover, the shorter sentence length and the higher average number of simple and compound sentences of the Italian texts (cf. Section 3) determine a positive impact on their level of readability and make them easier to process, which strengthens their greater degree of user-friendliness.

8 Conclusion

As has been seen, the recent strong moves towards globalization have implied relevant consequences in socio-cultural and communication terms. The formula-tion of concepts and texts in a multilingual/multicultural context is greatly con-ditioned by specific sociocultural and economic factors strictly depending on the different cultural, linguistic and specialized environments in which it takes place. The investigation of the process of adaptation of international procedures to dif-ferent national realities has pointed out several cases in which the source text offers the input on the basis of which new autonomous texts are created taking into consideration the needs of the final users. The process of customization of the UNCITRAL Model Law and Arbitration Rules has provided interesting insights into how normative discourse may change when adopted by countries relying on different cultural, linguistic, and legal conventions. The discussion of various lin-guistic and textual features has provided interesting insights into how socio- cultural factors are influenced by common law systems, on the one hand, and civil law systems, on the other, or by different target readers with their own legal culture and professional expectations. Indeed, although most of the national ar-bitration laws have followed the spirit of the UNCITRAL Model Law, they have

56

Maurizio Gotti

nonetheless been formulated and applied differently in different countries, and have often been constrained by variations in the languages used, the specific legal systems they were grounded in, and, in addition, the socio-political factors that operated in specific contexts.

Moreover, in the re-writing process implied in the customization of the origi-nal texts, the vagueness and indeterminacy of the origiorigi-nal texts – mainly due to the aim of the Model Law and the Arbitration Rules to be as all-inclusive as possi-ble in order to be valid in the widest range of applications – have been eliminated, and specific references to the local situation have been inserted so as to make the resulting texts correspond more closely to the legal and socio-cultural traits of the national target users. This can be seen, in particular, in the analysis of the speci-ficity of information included in the various texts, which differs significantly, due to discrepancy in socio-cultural expectations and practices. A relevant case in point was found in the comparison of the various clauses concerning the grounds for challenging the appointment of arbitrators: in the UNCITRAL texts they are expressed in more general terms, while in other texts the constraints are specified in greater detail.

The textual discrepancies observed in this analysis are a clear proof of the problems that arise in the process of establishing closer harmonization in legal normative discourse at a global level. These problems become particularly evi-dent when “model” texts have to be adopted in various contexts, thus giving rise to interesting differentiations in the resulting texts. In spite of the desire to make international arbitration texts “unbound” (Paulsson 1981) typical of the processes of harmonization and globalization, the differentiations observed in the arbitra-tion rules formulated at a local level are the result of conscious and deliberate decisions by national drafters, and demonstrate that the source texts have merely offered the input on the basis of which new autonomous texts have been created taking into consideration the local socio-legal environment and the needs of the final users.

References

Bartolini, Francesco, Roberto C. Delconte (eds.). 2001. Il codice dell’arbitrato [The Arbitration Code]. Piacenza: La Tribuna.

Belotti, Ulisse. 2002. The language of Italian arbitration rules in English: Some measurable aspects. Linguistica e Filologia 15. 113–141.

Belotti, Ulisse. 2003. Generic integrity in Italian arbitration rules. In V. Bhatia, C. Candlin & M. Gotti (eds.), Legal discourse in multilingual and multicultural contexts: Arbitration texts

Adapting an international model law

57 Bernstein, Ronald & Derek Wood. 1993. Handbook of arbitration practice. London: Sweet &

Maxwell.

Bhatia, Vijay. 1987. Textual-mapping in British legislative writing. World Englishes 1(1). 1–10. Bhatia, Vijay. 1993. Analyzing genre: Language use in professional settings. London: Longman. Bhatia, Vijay, Christopher Candlin & Jan Engberg (eds.). 2008. Legal discourse across cultures

and systems. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Bhatia, Vijay, Christopher Candlin & Paola Evangelisti Allori (eds.). 2008. Language, culture,

and the law: The formulation of legal concepts across systems and cultures. Bern: Peter

Lang.

Bhatia, Vijay, Christopher Candlin & Maurizio Gotti (eds.). 2003. Legal discourse in multilingual

and multicultural contexts: Arbitration texts in Europe. Bern: Peter Lang.

Bhatia, Vijay, Christopher Candlin & Maurizio Gotti (eds.). 2010. The discourses of dispute

resolution. Bern: Peter Lang.

Bhatia, Vijay, Christopher Candlin & Sandy Wei. 2001. Legal discourse in multilingual and

multicultural contexts: A preliminary study. Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong.

Bowers, Frederick. 1989. Linguistic aspects of legislative expression. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Campbell, Lisbeth. 1996. Drafting styles: Fuzzy or fussy? ELaw 3(2). http://www.murdoch.edu. au/elaw/issues/v3n2/campbell.html (accessed 22 April 2014).

Candlin, Christopher & Maurizio Gotti (eds.). 2004. Intercultural discourse in domain-specific

English. Special issue, Textus 17(1).

Candlin, Christopher & Maurizio Gotti (eds.). 2007. Intercultural aspects of specialized

communication. Bern: Peter Lang.

Ceccon, Roberto. 2000. La Corte Arbitrale di Venezia, una nuova istituzione per attrarre l’arbitrato internazionale in Italia [The Venice Arbitration Chamber, a new institution to attract international arbitration to Italy]. In Le prospettive dell’arbitrato interno ed

internazionale: il Regolamento della Corte Arbitrale di Venezia, 7–12. Turin: Giappichelli.

Chroma, Marta. 2003. The language of arbitration: From intent to the act. In V. Bhatia, C. Candlin & M. Gotti (eds.), Legal discourse in multilingual and multicultural contexts:

Arbitration texts in Europe, 63–86. Bern: Peter Lang.

Cremades, Bernardo M. 1998. Overcoming the clash of legal cultures: The role of interactive arbitration. Arbitration International 14(2). 157–172.

David, René. 1980. English law and French law. London: Stevens.

Dossena, Marina. 2003. Arbitration in Scotland: Local specificity and international

homogeneity. In V. Bhatia, C. Candlin & M. Gotti (eds.), Legal discourse in multilingual and

multicultural contexts: Arbitration texts in Europe, 87–109. Bern: Peter Lang.

Engberg, Jan & Kirsten Wølch Rasmussen. 2003. Danish legal language in international commercial arbitration. In V. Bhatia, C. Candlin & M. Gotti (eds.), Legal discourse in

multilingual and multicultural contexts: Arbitration texts in Europe, 111–154. Bern: Peter

Lang.

Garzone, Giuliana. 2003. Arbitration rules across legal cultures: An intercultural approach. In V. Bhatia, C. Candlin & M. Gotti (eds.), Legal discourse in multilingual and multicultural

contexts: Arbitration texts in Europe, 177–220. Bern: Peter Lang.

Giannoni, Davide S. 2003. The UNCITRAL model and Italian statute law: A linguistic and topical description. In V. Bhatia, C. Candlin & M. Gotti (eds.), Legal discourse in multilingual and

multicultural contexts: Arbitration texts in Europe, 221–246. Bern: Peter Lang.

58

Maurizio Gotti

Gotti, Maurizio & Susan Šarčević (eds.). 2006. Insights into specialized translation. Bern: Peter Lang.

Gotti, Maurizio & Christopher Williams (eds.). 2010a. Legal discourse across languages and

cultures. Bern: Peter Lang.

Gotti, Maurizio & Christopher Williams (eds.). 2010b. Legal English across cultures, Special issue, ESP Across Cultures 7.

Gustafsson, Marita. 1975. Some syntactic properties of English law language. Turku: University of Turku, Department of English.

Gustafsson, Marita. 1984. Syntactic features of binomial expressions in legal English. Text 4(1–3). 123–141.

Hunter, Robert L. C. 2002. The law of arbitration in Scotland. Edinburgh: Reed Elsevier. Jarvin, Sigvard. 1999. Leading arbitration seats: A (mostly European) comparative view. In

S. N. Frommel & B. A. K. Rider (eds.), Conflicting legal cultures in commercial arbitration:

Old issues and new trends, 39–61. The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

Landau, Toby. 1996. New duties and liabilities – Party autonomy versus powers of the tribunal. Paper presented at the IBC Conference, 4 July.

Paulsson, Jan. 1981. Arbitration unbound: Award detached from the law of its country of origin.

International and Comparative Law Quarterly 30. 358–387.

Sager, Juan C. 1990. A practical course in terminology processing. Amsterdam: Benjamins. Saleh, Samir. 1992. La perception de l’arbitrage au Machrek et dans les pays du Golfe. Revue de

l’Arbitrage 4. 549.

Salmi-Tolonen, Tarja. 2003. Arbitration law as action: An analysis of the Finnish Arbitration Act. In V. Bhatia, C. Candlin & M. Gotti (eds.), Legal discourse in multilingual and multicultural

contexts: Arbitration texts in Europe, 313–332. Bern: Peter Lang.

Sanders, Pieter. 1999. Quo vadis arbitration? Sixty years of arbitration practice. The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

Šarčević, Susan. 2000. New approach to legal translation. The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

Tessuto, Girolamo. 2003. Legislative discourse in arbitration language: The English 1996 Arbitration Act and the UNCITRAL model law. In V. Bhatia, C. Candlin & M. Gotti (eds.),

Legal discourse in multilingual and multicultural contexts: Arbitration texts in Europe,

337–379. Bern: Peter Lang.

Tiersma, Peter M. 1999. Legal language. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Williams, Christopher. 2007. Tradition and change in legal English: Verbal constructions in

prescriptive texts. Bern: Peter Lang.

Bionote

Maurizio Gotti (b. 1949) is a professor at the University of Bergamo

〈[email protected]〉. His research interests include ESP (English for Specific Pur-poses), English syntax, English historical linguistics, and lexicography. His pub-lications include Robert Boyle and the language of science (1998); Specialized

dis-course: Linguistic features and changing conventions (2003); and Investigating specialized discourse (2011).