CONTENTS

1. Introduction 2

1.1 Prevalence of depressive and alcohol use disorders 3 1.2 Course of illness of comorbid depression and alcohol use

disorders

6 1.3 Antidepressant treatment for depressed patients with alcohol-use

disorders

6

2. Aim of the study 17

3. Methods 18

3.1 Data Sources and Search Strategy 18

3.2 Study selection 19

3.3 Data Extraction 20

3.4 Definitions 21

3.5 Quantitative Data Synthesis 22

4. Results 25

4.1 Meta analysis results-Depression outcomes 27

4.2 Meta analysis results-Drinking outcomes 28

5. Discussion 30

6. Conclusions 35

7. Tables and Figures 38

1. INTRODUCTION

Depression and alcohol abuse or dependence are among the most prevalent and costly disorders confronting the health care system, and they tend to co-occur, leading to greater overall severity and worse health-related outcomes. A wide range of initiatives have been developed to improve screening and diagnosis of depressive and drug- or alcohol-use disorders in primary medical care settings where they commonly present, as well as in mental health or addiction treatment programs. However, controversy about how to treat patients with the concurrent disorders persists. One of the most basic questions is whether to treat depression in the setting of ongoing alcohol abuse or dependence. Recent recommendations suggest concurrent alcohol misuse should not be a barrier to treating depression. However, clinicians are often reluctant, for a variety of reasons, to initiate specific antidepressant treatment, including concerns about confusing alcohol induced depressive symptoms with true depressive disorders. Moreover, although previous meta-analyses have found antidepressants to be more effective than placebo in the treatment of depression in patients with alcohol use disorders, outcome studies for newer agents (i.e. the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or SSRIs) have yielded mixed results. More definitive evidence is needed to guide clinicians in treating the depressed dual-diagnosed patient population.

1.1 Prevalence of depressive and alcohol use disorders

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and dysthymic disorder (DD) are highly prevalent illnesses, frequently associated with significant morbidity, mortality, functional impairment, and patient suffering. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), MDD has a 12-month prevalence in developed countries between 3.1 % and 9.6 % (Nandi et al. 2009), and it contributes to a significant financial, logistical, and psychosocial burden on developed as well as developing nations (Fava et al. 2003). Dysthymic disorder, which constitutes a depressive condition defined by a mild yet chronic course, persistent symptoms, and an insidious onset, presents with a lifetime prevalence between 3% and 6% (Weissman et al. 1988; Kessler et al. 1994). Although patients with dysthymia often presents with a lower overall severity of symptoms than those with MDD, perhaps as a result of greater chronicity, the cumulative burden of persistent depressive symptoms and impaired functioning associated with this illness can sometimes be greater than that seen following most major depressive episodes (Klein and Santiago 2003). Patients with dysthymic disorder experience indeed considerable social dysfunction and disability and are more likely than the general population to use general medical services and to take non-specific psychotropic drugs (Akiskal 1983; Akiskal 1993; Marin et al. 1994).

Major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder are often complicated by the co-occurrence of substance use disorders, especially alcohol abuse or dependence. The high prevalence of comorbidity of the two conditions is of primary concern, considering that recent research has rated alcohol as the most harmful drug among

the substances of abuse (including harm caused to users as well as harm to others) (Nutt et al. 2010). There have been several explanations in the literature for the co-occurrence of depression and alcohol use disorders, including increased risk for vulnerability for a second disorder caused by the primary disorder, shared risk factors, attempts to ‘self-medicate’ depression with alcohol, residual depression from social, interpersonal and occupational problems caused by the alcohol use, impeded recovery caused by co-morbidity, and biologically driven substance-induced depression.

A recent systematic review of studies examining the association between alcohol use disorders (AUD) and depression found a median prevalence of current AUDs of 16% in patients with MDD, and a lifetime median prevalence of AUDs of 30% (Sullivan et al. 2005). More recently, the Sequential Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial found that 24% of patients with MDD met also criteria for a concurrent alcohol use disorder at baseline (Davis et al. 2010). On the other hand, high rates of depression are common among individuals with alcohol use disorders. Data from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), which is the largest comorbidity study in the US population completed to date, including data from 43,093 participants, reported a 12-month prevalence of 13.7 % and 2.9% respectively for major depression and dysthymia among respondents with a current alcohol use disorder, largely exceeding the estimated prevalence rates in the general population (6.7% and 1.5% for MDD and DD respectively) (Kessler et al. 2005). In clinical samples, probably because of the increased severity and

impairment of patients who seek treatment for such disorders, the rates of co-occurrence between depression and drug or alcohol misuse are even greater, with estimates ranging from 50 to 70% in patients with alcohol dependence (Conner et al. 2009). Conner et al. (2009) performed a meta-analysis of 74 controlled studies on adults with alcohol abuse or dependence, where data on depression and substance use were documented. They found a positive association of depression with concurrent alcohol-use disorders: subjects with above-average levels of depressive symptoms constituted 60.5% and showed above-average levels of current alcohol use and impairment compared with 39.5% of subjects with below-average levels of depressive symptoms. In the NESARC sample, the rates of co-occurrence for mood disorders and alcohol use disorders were 32.8% and 11.0 % for MDD and DD respectively among people who sought treatment for an alcohol use disorder. A recent meta-analysis of 18 randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials on the efficacy of acamprosate for the treatment of alcohol dependent patients (Lejoyeux and Lehert 2010), found a prevalence of co-occurrent depression of 33.4% (varying from 29% to 53% across the studies), thus more than three times the prevalence found among the general population.

The co-occurrence of MDD and AUD may present diagnostic and management challenges, as many symptoms of depression may also arise as the direct physiological effects of the substance, and differentiating between primary and secondary (i.e., substance induced) MDD can be complicated in clinical practice. However, recent data bring into question the clinical utility of such differentiation, suggesting that patients who have substance-induced mood disorders are just as

likely in prospective follow-up to have mood episodes independent of any substance use as are patients who have substance-use disorders and independent mood disorders (Nunes et al. 2006). For both groups, recurrence of depression is common and is most likely to occur independent of substance abuse. Results from the NESARC sample, in fact, showed that only few patients with alcohol or substance use disorders and a current mood disorder experienced depressive episodes that were exclusively classified as substance induced. Several other cross-sectional and longitudinal epidemiologic studies have provided further support for the strong and specific association between AUD and primary MDD, indicating that this association is not entirely an artifact of misdiagnosed intoxication and withdrawal effects(Brown and Schuckit 1988; Nunes et al. 2006).

1.2 Course of illness of comorbid depression and alcohol use disorders

When depression co-occurs with AUDs, the course and the outcomes of each disorder seem to be complicated by the other. Watkins et al. (2006) found that depressed patients with alcohol and other substance use disorders had an increased probability of ongoing depression despite receiving higher rates of appropriate treatment(Watkins et al. 2006). Patients with concurrent MDD and AUD tend to have an earlier age of onset of depression, greater depressive symptomatology, more functional impairment, increased risk of relapse, decreased likelihood of recovery, and increased suicidality (Thase et al. 2001; Rush et al. 2008; Sher et al. 2008; Conner et al. 2009). Alcohol consumption, abuse and dependence are independent risk factors for all types of suicidal behavior (Brady 2006). It has been

reported that the lifetime risk of suicide among subjects with alcohol dependence is 15%., and the risk for attempted suicide is 6.5 times greater than in those without alcohol dependence (Kessler et al. 1999). Suicide attempts frequently follow acute alcohol intoxication. In a French cohort of patients examined in an emergency ward further to a suicide attempt (Lejoyeux et al. 2008), 40% had ingested alcohol before trying to commit suicide. Wojnar et al. (2009) studied 154 patients with alcohol dependence consecutively admitted for addiction treatment (Wojnar et al. 2009). Suicidal behavior was assessed together with severity of alcohol dependence, childhood abuse, impulsiveness and family history. Lifetime suicide attempts were reported by 43% of patients in alcohol dependence treatment, and 62% of such attempts were impulsive. Severity of depression was one of the factors associated with the occurrence of suicide attempts, along with a history of sexual abuse, a family history of suicide, and higher scores on a personality measure of impulsiveness.

On the other hand, a concurrent depression in alcohol-dependent patients exerts a negative effect on the course and treatment outcome of the alcohol use disorder. Among individuals with alcohol-use disorders, co-occurring depression has been associated with greater alcohol-related impairment and with greater participation in substance abuse treatment (Conner et al. 2009). Despite increasing the likelihood that alcohol-dependent patients may seek care, depression can interfere with patients’ attempts at sobriety in a number of ways at various time-points in the treatment process (Gamble et al. 2010). Pretreatment depressive symptoms are associated with higher rates of treatment drop-out (Curran et al. 2002), shorter time

to first drink(Greenfield, Weiss et al. 1998), lower rates of abstinence following treatment completion (Ilgen and Moos 2005), and greater risk for suicide attempts(Ilgen et al. 2004). In addition, findings among treated alcohol dependent patients point to the relationship between post-treatment depression and more rapid relapse for drinking problems following treatment(Svanum and McAdoo 1989; Glenn and Parsons 1991; Curran et al. 2000; Curran et al. 2002), greater non abstinence, more drinking days per month, and more drinks per drinking day (Kodl et al. 2008). When comparing baseline addictive characteristics between alcohol dependent patients with and without co-occurrent depression, Lejoyeux and Lehert (2010) observed that the motivation to start a treatment and compliance from the onset of treatment were much lower in depressed patients(Lejoyeux and Lehert 2010). The authors considered this reduced level of motivation as a possible explanation of the negative effect of baseline depression on patient drinking outcome (measured as percent of abstinent days and continuous abstinence), according to previous data showing that a reduced level of motivation reduces the impact of psychotherapeutic and pharmacological treatments of alcohol dependence (Mason et al. 2006). However, not all research has found a clear association between baseline depressive symptoms and adverse drinking-related outcomes among individuals with alcohol-use disorders (Hesselbrock et al. 1985; Kranzler et al. 1996; Randall et al. 2001; Conner et al. 2005). For example, Gamble and colleagues (2010) investigated the extent to which depressive symptoms at pre-admission versus post-treatment predicted drinking outcomes in the year following treatment in Project MATCH (Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client

Heterogeneity). The authors found that pretreatment depressive symptom severity was associated with more frequent and intense drinking in the year following treatment, although not after accounting for post-treatment depressive symptom severity. This data underscore the importance of targeting co-occurring depression when treating patients with alcohol use treatment, as treatment of depression in these patients may have a beneficial outcome by improving longer-term abstinence and overall functioning.

Finally, the presence of a dual diagnosis is also associated with high rates of medical and psychiatric comorbidity, and increased use of general medical health services as well as psychiatric hospitalizations (Holder and Hallan 1986; Fortney et al. 1999; Pettinati et al. 2010).

1.3 Antidepressant treatment for depressed patients with alcohol-use disorders It is well recognized that major depression is one of the most prevalent comorbid psychiatric disorders in alcohol and substance abusers, and longitudinal studies have demonstrated that the presence of a dual diagnosis is associated with a worse clinical outcome of both the disorders, emphasizing the need of treatment to improve both depression and substance abuse disorders. However, the management of the co-occurring depression in patients with alcohol or substance abuse disorders is still a source of confusion and considerable controversy. One of the most basic questions is whether to treat depression in the setting of ongoing substance abuse. Based on the data suggesting that in many cases depressive symptoms resolve within days or weeks after a patient becomes abstinent or enter an effective

treatment modality (Brown and Schuckit 1988; Brown et al. 1995; Liappas et al. 2002), one school of thought holds that such depression is mostly a consequence of ongoing addiction – effects of substance intoxication or withdrawal – thus, the appropriate treatment is treatment of the addiction to get the patient abstinent and into recovery, after which the depression should resolve. Another school, however, holds that depression should be treated and that such treatment might help patients achieve abstinence, perhaps because the addiction is partly driven by “self-medication” of the symptoms of depression. In many cases, indeed, depressive symptoms may complicate or delay the ability to attain abstinence. Therefore, it is important to understand whether treatment of depression in these patients will have a beneficial outcome.

Antidepressants are commonly used in substance abusers to treat comorbid depression and for the potential action of these drugs on some of the underlying mechanisms involved in addiction and drug dependence (Nunes et al. 1994; Thase et al. 2001; Pettinati et al. 2003).

The vast majority of our knowledge regarding the efficacy of antidepressants for the treatment of depression (MDD or DD) derives from randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that employ standard criteria, which typically aim to exclude certain groups of patients (Sullivan and Joyce 1994; Partonen et al. 1996; Posternak et al. 2002; Zimmerman et al. 2002; Zimmerman et al. 2004; Zetin and Hoepner 2007; Wisniewski et al. 2009), including patients with active or recent AUDs or drug use disorders, as well as pregnant or breastfeeding women, children, adolescents and the elderly, patients with psychotic symptoms, at imminent risk of

suicide, or patients with serious and unstable medical illness (axis-III co-morbidity). Therefore, there is an important gap in clinical knowledge regarding whether antidepressants are also effective in relieving depression in these special populations. In fact, it has even been suggested that treatment outcomes may differ between patients who are and are not typically included in antidepressant treatment trials (Wisniewski et al. 2009), although not all studies support this finding (Sullivan and Joyce 1994). As a result, separate clinical trials are often required in order to establish whether antidepressant agents are effective and safe in treating depression in patients typically excluded from MDD/DD efficacy trials.

There are a number of published reports of the use of antidepressant for the treatment of depression in patients who have alcohol and drug use disorders, ranging from case reports to moderately large, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. However, to date there is a paucity of well-designed, adequately powered trials that have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of antidepressants as monotherapy for patients with depressive disorders and co-occurring AUDs, which may guide clinicians and patients in the treatment of depression in this specific patient population. A considerable heterogeneity between trials often makes comparisons difficult and limits the generalizability of the results. For example, there is not a uniform definition of depression across studies; some studies include only subjects who have a research diagnosis of major depressive disorder with a minimum score on a depression rating scale; others include subjects who have major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and depression not otherwise specified (NOS). Some studies include subjects who are not abstinent

from drugs or alcohol at entry into the trial; others include only subjects who have been detoxified in inpatient settings and are abstinent at the start of treatment. Moreover, studies of depression in subjects with alcohol- and substance-use disorders generally include subjects who have dependence—not abuse—syndromes and may not represent the population of patients who have co-occurring substance-use and mood disorders who seek treatment in primary care and general psychiatric treatment settings. As a consequence, outcomes from these studies may provide little direct evidence for the treatment of patients who have substance-abuse rather than substance-dependence diagnoses.

However, despite some methodologic issues complicating the interpretation of the data from studies of the treatment of mood disorders in patients with current alcohol and substance-use disorders, there has been some evidence that antidepressants may improve depressive symptoms in patients with concurrent AUDs. (Nunes and Levin 2004; Pettinati 2004; Sullivan et al. 2005; Torrens et al. 2005; Davis et al. 2010). Two reviews of controlled trials of pharmacotherapy for depression with comorbid alcohol disorders by Pettinati (Pettinati 2004) and by Sullivan and colleagues (Sullivan et al. 2005), found supporting evidence that antidepressants are superior to placebo in reducing depressive symptoms in this patient population, even though they are not as effective in reducing alcohol use. Nunes and Levin (2004) conducted a meta-analysis of published, randomized, double-blinded, controlled, clinical trials of antidepressants for the treatment of patients with unipolar depressive disorders (MDD, DD, and depression NOS) and co-occurring alcohol- and drug-use disorders, and found that antidepressant

medications exert a modest benefit in treating depressive symptoms in such dual-diagnosis patients (effect size 0.38), but had only a small effect in decreasing drug or alcohol use. The authors found that the likelihood of detecting an antidepressant effect was higher in studies with low placebo response (consistent with findings in antidepressant trials in subjects without substance abuse) and concluded that antidepressants can be useful in these patients if used in adequate doses, for an adequate length of time (at least 6 weeks), and in patients whose diagnosis is well established by a thorough history and a structured diagnostic interview. Moderator analysis suggested also that the concurrent psychosocial interventions influenced outcome, diminishing the drug–placebo difference. Meta-analysis results showed that antidepressant efficacy was greater in patients who had alcohol-use disorder than in those who had substance-use disorder. Similarly, a subsequent meta-analysis of trials on the efficacy of antidepressants in subjects with alcohol and drug use disorders with and without comorbid depression by Torrens et al. (2005)(Torrens, Fonseca et al. 2005) found a significant effect of antidepressants to treat depressive symptoms in patients with alcohol use disorders (OR= 4.15, 95% CI:1.35–12.75). It failed, however, to demonstrate a significant advantage for the use of SSRIs (OR= 1.85, 95% CI: 0.73–4.68).

Two additional studies focusing on the use of the SSRIs in patients with depression and AUDs have been published since this last meta-analysis, which again have brought into question the utility of the SSRIs for the treatment of depression in this specific patient population. The first one (Kranzler et al. 2006) is a large multisite trial comparing sertraline (50–150 mg/day for 10 weeks) with placebo in 328

subjects with co-occurrent major depression and alcohol dependence. In both treatment groups response rates were greater than 50%, and sertraline failed to show any additional benefit compared with placebo in reducing depressive symptoms, as well as in reducing drinking. The high placebo response rate was adduced as one possible explanation of the failed trial; in particular, as patients were included if they met criteria for a major depressive episode after only 4 days of abstinence, this might have allowed to include a large number of subjects whose depressive symptoms might have resolved spontaneously during a longer period of abstinence. The second study (Pettinati et al. 2010) involved a total of 170 depressed alcohol-dependent patients, randomly assigned to receive 14 weeks of treatment with sertraline (200 mg/day), naltrexone (100 mg/day), the combination of sertraline plus naltrexone, or double placebo, while receiving weekly cognitive-behavioral therapy. The authors found no advantage in treatment with sertraline alone in depressive symptom reduction, whereas the medication combination (sertraline 200 mg/day plus naltrexone 100 mg/day) resulted in significant reduction of depressive symptoms as well as better drinking outcomes (both abstinence from alcohol and delayed relapse to heavy drinking) compared with patients receiving single-medication or placebo treatments. Finally, recently published results from the STAR*D trial indicate that depressed patients with alcohol use disorders respond to a first-line treatment with citalopram as well as those without a dual diagnis, suggesting that concurrent alcohol abuse should not be a barrier to treating depression (Davis et al. 2010). In particular, the STAR*D MDD sample showed overall modest improvement in depressive symptoms to

first-line treatment with citalopram, with 47% achieving response and 33% achieving remission; no differences in response and time to response were found between the MDD alone and the MDD with comorbid substance use disorders groups. However, subject who endorsed both alcohol and drug use experienced a significantly longer time to remission and fewer achieved remission (22.5%) compared to those without concurrent alcohol or drug use disorder (33.4%), those with depression and alcohol use only (35.5%), and those with depression and drug use only (28.4%). When comparing these findings with those of previously published studies, some important differences in the type of patient recruitment must be kept in mind. First, the STAR*D dual diagnosed patient population was primarily seeking treatment for MDD rather than alcohol or substance use disorders. Second, the treatment setting included primary care and specialty psychiatric care clinics; although referrals from substance use treatment programs were accepted, participants were not exclusively recruited from addiction treatment programs. On the other hand, the majority of studies on dual-diagnosed patient populations primarily recruit participants from rehabilitation or addiction treatment programs.

2. AIM OF THE STUDY

The aim of the present work is to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of antidepressants used in monotherapy for the treatment of depressive symptoms in patients with comorbid unipolar depression (MDD and DD) and alcohol use disorders (abuse and dependence), and to gain knowledge of what methodologic features of pharmacologic treatment trials targeting depressed alcohol abusers/dependents predict better treatment response. For this purpose, we conducted a systematic and updated review of the literature on antidepressant treatments for dual diagnosed patients (MDD/DD and AUDs), focusing on randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled antidepressant monotherapy trials for the treatment of depression in this patient population. The results of these trials, if simply tallied up, yield mixed conclusions and do not provide a univocal answer to the question on whether antidepressants are effective in depressed patients with AUDs, as well as on whether their efficacy is comparable in depressed patients with or without AUDs. This is where a quantitative review of the literature, namely a meta-analysis, can be helpful. In meta-analysis, a group of studies with similar methodology is combined mathematically into one large study in an effort to obtain a more precise estimate of the treatment effect. Additionally, meta-analysis yields an estimate of heterogeneity of effect. The test of heterogeneity estimates whether all the studies come from the same distribution, differing mainly because of random differences in sampling, or whether the differences in magnitude of effect size between studies are large enough to suggest that the studies differ significantly among themselves.

We therefore conducted a meta-analysis of all randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled antidepressant monotherapy studies for patients with unipolar depression (MDD and DD) with co-morbid AUDs in order to examine the efficacy of antidepressants in this patient population, and to compare both antidepressant and placebo response rates from clinical trials examining MDD/DD patients with or without AUDs (primary outcome). Secondary outcomes of the present analysis are to compare the rates of overall discontinuation and discontinuation due to adverse events between the two clinical trials groups (trials which did versus did not focus on patients with MDD/DD and comorbid AUDs), and to assess the efficacy of antidepressants in reducing alcohol consumption in patients with comorbid MDD/DD and AUDs.

Result from this meta-analysis may provide further evidence that could help in the treatment of this particular, and often difficult to treat, patient population. Moreover, examining whether there are differences in clinical characteristics or treatment outcomes between depressed patients with or without AUDs could provide insights which would help in the design of future antidepressant treatment studies in these co-morbid MDD patients.

3. METHODS

3.1 Data Sources and Search Strategy

We sought to identify double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants used as monotherapy for the treatment of MDD/DD in patient populations that were or were not specifically selected for the presence of a co-morbid AUDs for possible inclusion in the meta-analysis. As antidepressants, we defined pharmacological agents which have or had received a letter of approval by either the U.S., Canadian, or E.U. drug regulatory agencies for the treatment of MDD and/or DD. According to this definition, the following pharmacologic agents met criteria to be considered as “antidepressants”: amitriptyline, nortriptyline, imipramine, desipramine, clomipramine, trimipramine, protriptyline, dothiepin, doxepin, lofepramine, amoxapine, maprotiline, amineptine, nomifensine, bupropion, phenelzine, tranylcypromine, isocarboxazid, moclobemide, brofaromine, fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram, escitalopram, fluvoxamine, zimelidine, tianeptine, ritanserin, trazodone, nefazodone, agomelatine, venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine, duloxetine, viloxazine, milnacipran, reboxetine, mirtazapine, mianserin.

Elgible studies were first identified using searches of Pubmed/Medline, by cross-referencing the search term “placebo” with each of the above-mentioned agents. The Pubmed/Medline search was limited to articles that were published between January 1st, 1980 and March 15th, 2010 (inclusive). 1980 was used as a cut-off in our search in order to decrease diagnostic variability, since the DSM-III was introduced in 1980.

In order to expand our database, we then reviewed the reference list of all studies identified with Pubmed/Medline. Each potentially relevant study located in the

search was obtained in full text and assessed for inclusion independently by two authors. Final inclusion of articles was determined by consensus between the authors.

3.2 Study selection

We selected for randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled trials of antidepressants used as monotherapy for the acute-phase treatment of MDD or DD with or without comorbid AUDs. We then selected for studies that also met all of the following criteria:

1. Defined either MDD or DD according to either the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, Third Edition (American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on Nomenclature and Statistics. and American Psychiatric Association. Committee on Nomenclature and Statistics. 1980); Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition Revised (American Psychiatric Association. Work Group to Revise DSM-III. 1987);Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association. and American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. 1994), Reseach Diagnostic Criteria (Spitzer et al. 1978), or Feighner’s Diagnostic Criteria (Feighner et al. 1972).

2. Were of, at least, four weeks in duration.

4. Presented entirely original (not previously published) data. 5. Focused on the treatment of adult patients.

6. Did not exclusively focus on the treatment of patients with either treatment-resistant depression, bipolar depressive disorder, depression with psychotic features, minor depression or peri-natal depression.

7. Did not exclusively focus on the treatment of MDD in patients with comorbid substance use disorders other that alcohol, or patients with a specific comorbid medical illness.

8. Involved the use of either the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton 1960), the Montgomery-Asperg Depression Rating Scale (Montgomery and Asberg 1979), or the Clinical Global Impression- Improvement Scale (Guy, National Institute of Mental Health (U.S.). Psychopharmacology Research Branch. et al. 1976) as one of their outcome measures.

3.3 Data Extraction

Data were extracted by one of the authors and checked for accuracy by the others. A standardized checklist was used to collect information on methodology, participants, interventions, and primary and secondary outcomes. The following data were extracted from studies included in the meta-analysis: the criteria used to establish the diagnosis of MDD/DD and AUD, the number of patients randomized to each treatment arm (antidepressant or placebo), the antidepressant used and their doses, the duration of the trial, the primary outcome measure used (HAM-D, MADRS or CGI), response rates for the primary outcome measure, overall discontinuation rates and

discontinuation rates due adverse events for the secondary outcome measures. For studies focused on patients with comorbid MDD/DD and AUD, the following data were also collected: whether the study involved an adjunctive non-pharmacologic intervention (cognitive-behavioral therapy, group therapy, or support psychotherapy), whether a minimum length of abstinence from alcohol was required, and the severity of drinking at baseline and at endpoint.

3.4 Definitions

Clinical response was defined as a 50% or greater reduction in HDRS or MADRS scores, baseline to endpoint, or a CGI-I<3 at the final visit. For consistency, the HDRS was chosen over the MARDS or CGI when response rates from multiple scales were reported. For studies that only reported CGI-based response rates, the HDRS-based response rates were either obtained from the sponsor, or imputed using the method of Walsh et al.(Walsh et al. 2002). In cases where continuous (change in depression severity scores), but not dichotomous (response rates) outcomes were presented, and dichotomous outcomes could not be obtained from the study authors, we converted continuous outcomes to dichotomous outcomes using the following method: a multiple regression was conducted with response rate as the dependent variable and percent score reduction as the independent variable, using data from as many studies that reported both outcomes. Unobtainable response rates were then calculated with the use of the regression coefficients derived, applied for the given percent score reduction for that study. Some studies depicted changes in HRSD scores only graphically. In these instances, changes in HRSD scores were obtained by

measuring each data-point with rounding to the nearest 0.5. Discontinuation rate was defined as per each protocol. For consistency, we used intent-to-treat (ITT)-based response rates in the present analysis. Whenever ITT-based response rates were not available in the publication, the sponsor was contacted to obtain ITT-based response rates. In cases where the sponsor could not retrieve ITT-based response rates, we utilized response rates based on completers. The probability of receiving placebo was computed from the number of treatment arms and the randomization schedule (i.e. 1:1:1) of each trial. For example, a two-arm trial with a 2:1 randomization favoring antidepressant treatment yields a 1 in 3 chance of receiving placebo.

3.5 Quantitative Data Synthesis

Response rates between groups were compared with the use of ANOVA. In addition to sample size, when antidepressant response rates were compared between trials involving patients with versus without co-morbid AUDs, the probability of being randomized to placebo as well as dosing (fixed versus flexible) were also entered as covariates, because they were found to predict antidepressant response rates in a previous meta analysis (Papakostas and Fava 2009). Similarly, in addition to sample size, when placebo response rates were compared between these two clinical trial groups (i.e., those which did versus did not select for the presence of co-morbid AUDs), severity at baseline, year of publication, and the probability of being randomized to placebo were also entered as covariates for the same reason. Random-effects meta-analysis was utilized to estimate the pooled risk ratio (RR) of responding to antidepressants versus placebo in MDD/DD trials which specifically selected for the

presence of co-morbid AUDs. A meta-regression was used in order to compare RR of responding to antidepressants versus placebo between these two clinical trial groups (i.e., those which did versus did not select for the presence of co-morbid AUDs). For this meta-regression, year of publication, severity at baseline, and the probability of being randomized to placebo were also entered as covariates since they had also previously been found to influence the RR of clinical response following antidepressant versus placebo therapy. Finally a meta-regression was conducted in order to compare the RR of discontinuing antidepressants versus placebo between these two clinical trial groups (trials involving patients with versus without co-morbid AUDs). For this meta-regression only study duration was entered as covariate since no other variable had previously been found to influence the RR of discontinuing antidepressants versus placebo (Tedeschini et al.).

Finally, as a post-hoc analysis, we sought to examine the impact of antidepressant medications on drinking. Manuscripts were reviewed and all authors were contacted in order to obtain the number of heavy drinking days (as per protocol) during the last week of the trial. Such data were available for two trials only. Thus, a random-effects meta-analysis was used to compare the percentage of heavy drinking days between antidepressant- and placebo- treated patients for these two studies.

The presence of heterogeneity between the trials was tested using the Cochrane's χ 2 test or Q-test. A p-value of the test lower than 0.05 indicates a significant heterogeneity across studies.

All the analyses were performed with the meta package of meta-analytic tools as implemented in Stata 10.0 (Stata, College Station, Tex.). All tests conducted were

4. RESULTS

Initially 7,349 abstracts were identified in Pubmed/Medline. Of these, 6,926 were excluded for a number of reasons (other topics, reviews). The remaining 423 abstracts described clinical trials of antidepressants for MDD/DD. These 423 articles were obtained, and reviewed thoroughly. Fifteen additional articles were identified after reviewing the reference list of these 423 manuscripts as well as two large meta-analyses. One hundred manuscripts were excluded because they presented data published elsewhere, 25 manuscripts were excluded because they focused on children and/or adolescents with depression, and 34 were excluded either because they focused on the treatment of depressive disorders other than MDD or DD (bipolar disorder, MDD with psychotic features, minor depression, “neurotic depression”), because they focused on peri-natal MDD, because the diagnosis of MDD/DD was based on the DSM-II, or because they did not state which, if any diagnostic criteria, were used to define MDD/DD. One study was excluded because it focused on patients with treatment-resistant depression, 14 were excluded because they focused on the treatment of patients with depression and co-morbid drug use disorders, 61 because they focused on the treatment of patients with depression and co-morbid axis-III disorders. Three were excluded because they did not involve the use of an oral form of an antidepressant (selegiline), 3 because they were less than 4 weeks in duration, and two studies because they did not involve the use of the HDRS, MADRS or CGI.

Thus, a total of 195 manuscripts were found eligible for inclusion in our pooled analysis. Eleven of the 195 trials focused on MDD/DD patients specifically selected for the presence of co-morbid AUDs. While 189 manuscripts reported the results of a single trial, 6 reported results of several (a total of 14) trials. Thus, a total of 325 antidepressant versus placebo comparisons from 203 clinical trials were pooled (n=46,820 patients randomized to treatment with an antidepressant (n=29,664) versus placebo (n=17,156)), 12 of which were derived from clinical trials on the treatment of MDD or DD with co-morbid AUDs (n=891 patients randomized to treatment with an antidepressant (n=443) versus placebo (n=448)). A specific description of characteristics of trials involving MDD/DD patients with co-morbid AUDs is reported in table 1. A statistically-significant difference was found between trials that were not versus those that were specifically focusing on treating MDD/DD in patients with co-morbid AUDs for the following variables: mean (+/- s.d.) study duration in weeks (7.1+/- 2.9 versus 13.2 +/- 5.4, respectively, p<0.001), mean baseline severity in terms of mean (+/- s.d.) HDRS-17 scores at baseline (21.6 +/- 4.0 versus 17.0 +/- 3.8, respectively, p<0.001), mean (+/- s.d.) probability of receiving placebo (35.5 +/- 9.1 % versus 47.9 +/- 7.2 %, respectively, p<0.001), mean proportion of women (61.6% versus 37.0 %, respectively, p<0.001), and mean (+/- s.d.) sample size per treatment arm (94.4 +/- 58.8, versus 37.1 +/- 23.3, respectively, p<0.001). There was no statistically-significant difference between the two trial groups in mean (+/- s.d.) age in years (44.0 +/- 8.9 versus 41.5 +/- 3.2, respectively, p=0.167) as well as in mean year of publication (+/- s.d. in number of years) (1996 +/- 7.9 versus 2000 +/- 5.6, respectively, p=0.062).

4.1 Meta analysis results-Depression outcomes

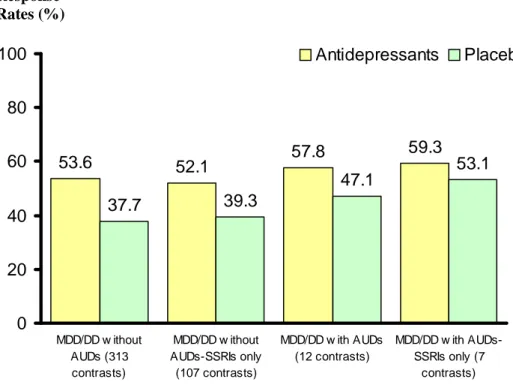

Response rates for antidepressants versus placebo in clinical trials of MDD/DD patients with co-morbid AUDs were 57.8% (256/443) versus 47.1% (211/448), respectively (number needed to treat (NNT) of, approximately, 9). Response rates for antidepressants versus placebo in clinical trials of MDD/DD patients without co-morbid AUDs were 53.6% (15,907/29,664) versus 37.7% (6,469/17,156), respectively (NNT of, approximately, 6) (figure 1). There was no statistically significant difference in antidepressants response rates (p=0.097) and placebo response rates (p=0.342) between the two clinical trial groups (i.e., those which did versus did not select for the presence of co-morbid AUDs)

The result of the random-effects meta-analysis indicated that antidepressant therapy resulted in statistically significant higher response rates than placebo in MDD/DD patients with co-morbid AUDs (Risk Ratio (RR) = 1.336; 95% C.I.= 1.045-1.708; p=0.021) (figure 2). There was no statistical evidence for heterogeneity in the RR for response to antidepressants versus placebo in these trials (Q=17.110; d.f.=11, p=0.105). However, when only studies that involved the use of SSRIs were analyzed, the result of the random-effects meta-analysis indicated no statistically significant difference in the response rates of antidepressants versus placebo in this selected patient population (RR= 1.145; 95% C.I.= 0.879-1.492; p=0.316), while a statistically significant difference in the response rates of SSRIs versus placebo was observed in clinical trials of MDD/DD patients without co-morbid AUDs (RR= 1.346; 95% C.I.=

1.293-1.400; p<0.001). There was no statistical evidence for heterogeneity in the RR for response to antidepressants versus placebo in trials involving the use of SSRIs in MDD/DD patients with and without co-morbid AUDs (Q=8.783; d.f.=6, p=0.186, and Q=109.371; d.f.=106, p=0.392 respectively). Response rates for SSRI- and placebo- treated patients from studies of MDD/DD with co-morbid AUDs were 59.3% (192/324) vs 53.1% (178/335) respectively (NNT of, approximately, 16). Response rates for SSRI- and placebo- treated patients from studies of MDD/DD without co-morbid AUDs were 52.1% (6,140/11,781) vs 39.3% (3,143/7,999) respectively (NNT of, approximately, 7) (figure 1).

Meta-regression analysis suggested no statistically significant difference in the risk ratio of responding to antidepressant versus placebo (coefficient of -0.0019, p=0.973) and in the RR of prematurely discontinuing antidepressant versus placebo due to any reason (coefficient of 0.0470, p=0.550) or due to adverse events (coefficient of -0.0804, p=0.743) when comparing studies involving MDD/DD patients with or without co-morbid AUDs. Meta-regression analyses also suggested no statistically significant difference in the RR of responding to antidepressants versus placebo among trials of MDD/DD patients with co-morbid AUDs when comparing trials that involved antidepressant therapy alone versus those that included a concurrent psychotherapy (coefficient of -0.0949, p=0.531), as well as when comparing trials that included only patients with alcohol dependence versus those that included both alcohol dependence and abuse (coefficient of -0.1147, p=0.381), when comparing trials that required a minimum period of abstinence from alcohol versus those that

included patients who were actively drinking (coefficient of -0.0138, p=0.915), and when comparing trials that included only patients with MDD versus those that included both patients with MDD and DD (coefficient of -0.0360, p=0.774). Moreover, the baseline severity of drinking (assessed as the number of heavy drinking days in the week before randomization) did not predict a significantly difference in the response rate to antidepressants (coefficient= -0.644, p=0.467).

4.2 Meta analysis results-Drinking outcomes

Finally, we conducted a post-hoc meta-analysis specifically focusing on the impact of antidepressant medications on drinking, using as outcome measure the number of heavy drinking days (as per protocol) during the last week of the trial the. For the two studies for which this data was available, the result of the random-effects meta-analysis indicated that there was no statistically significant difference in the percentage of heavy drinking days between antidepressant- and placebo- treated patients (Risk Ratio (RR) = 0.691, 95% C.I.= 0.355-1.342, p=0.275) and there was no evidence for statistically significant heterogeneity (Q=0.341, d.f..=1, p=0.559).

5. DISCUSSION

This analysis is the most comprehensive to date examining the efficacy of antidepressants for the treatment of unipolar depression in patients with co-morbid alcohol use disorders, and the first to compare the effect size of antidepressants versus placebo in this select patient population and in the general MDD/DD population. Our work suggests that antidepressants are more effective than placebo in treating depression in patients with co-morbid AUDs (with a number-needed to treat for response of, approximately, 9), without any evidence of across-study heterogeneity. This finding is consistent with results from previous meta-analyses (Nunes and Levin 2004; Torrens et al. 2005), which reported that antidepressants are effective in treating depression in patients with co-occurring depression and AUD, and lends further support to the argument that antidepressants should represent first-line therapy for targeting depressive symptoms in patients with MDD or DD and concurrent AUDs. However, similarly to the two previous meta-analyses conducted on this topic, we also failed to detect a significant treatment effect for the SSRIs in this population, despite the addition of two studies not previously pooled. This is principally due to a high placebo response rate in these studies. Thus, the majority of evidence supporting the use of antidepressants in our meta-analysis derives from studies which involved nefazodone and the TCAs imipramine and desipramine, while the use of SSRIs for treating depression in this selected patient population is not convincingly supported by the evidence. Nevertheless, SSRIs remain an attractive first-line treatment among patients with AUDs because of their tolerablity, low toxic effects, and minimal

sedating effects. However, if a SSRI trial fails, consideration should be given to an agent with noradrenergic or other mechanisms. Finally, we did not find antidepressant treatment to result in greater sobriety than placebo administration in this population, although it should be pointed out that this may have been due to the relative paucity of data (data could only be obtained from two of the studies), and the short follow-up duration (i.e. perhaps significant effects may have been detected if the duration of follow-up was longer).

It should also be pointed out that our present results differ in some ways from those cited in the two prior meta-analyses on the subject (Nunes and Levin 2004; Torrens et al. 2005). For example, while the meta-analysis of Nunes and Levin found that the concurrent use of a psychosocial treatment reduced the absolute numerical difference between antidepressant and placebo response rates, whereas the presence of at least one week of abstinence increased the efficacy of antidepressant therapy versus placebo, our analysis could not replicate these two findings. Our work, in fact, showed that the efficacy of antidepressants was not influenced whether antidepressants were used alone or adjunctively to psychotherapy (either cognitive behavioral therapy or supportive psychotherapy), whether used in patients actively drinking or recently sober (i.e. a few days), or whether used in pure MDD or in combined MDD and DD populations. In fact, in regression analyses, we did not find any relationship between the severity of baseline drinking and treatment outcome. That the presence/absence or severity of recent sobriety does not predict outcome suggests that the decision whether

to recommend antidepressants in this patient population should not be determined by these variables, at least as far as the potential efficacy of treatment is concerned. There are several factors that may explain the discrepancy between our findings and those of Torrens et al. (2005), or Nunes and Levin (2004). For example, our meta analysis focused on patients with depression and alcohol use disorders, while Nunes and Levin also included studies examining depression with co-morbid cocaine or opiate use disorders which may account for the difference in meta-analysis findings. In fact, Nunes and Levin did report a small difference in effect size between AUD and opiate/cocaine use-disorder studies (smaller effect size in the latter group).

Finally, an additional finding of our study was that the effect size (i.e. the difference in response rates between antidepressant- and placebo-treated patients) was not statistically different when comparing general MDD/DD trials that typically exclude patients with active AUD, versus those MDD/DD trials that specifically focus on the treatment of depression with co-morbid AUDs, which suggest that power calculations for the design of future studies in this patient population should be in line with those for the general MDD/DD population. In addition, results from this meta-analysis may encourage researchers who are conducting multi-site, randomized, controlled clinical trials on antidepressant treatment to reconsider the strict exclusion of subjects with concurrent alcohol abuse or dependence.

We did not find significant difference in the risk ratio of prematurely discontinuing antidepressant versus placebo due to any reason or due to adverse events when comparing studies involving MDD/DD patients with or without co-morbid AUDs.

However, clinicians and investigators should be aware of the potential for substance use disorders to increase the chance of severe psychiatric adverse events in the MDD patient population (Davis et al. 2010).

Several limitations should be taken into account when interpreting our findings. Specifically, one limitation pertains to the identification of studies to be included in pooled analyses or meta-analyses. For example, it is quite possible that either publication bias or the file-drawer phenomenon, whereby unpublished studies are more likely to be equivocal than published trials, may have distorted our findings or inflated our results (since our study only focused on published clinical trials). It would be interesting to examine whether the inclusion of unpublished studies strengthens or weakens our findings. Moreover, the present work involves pooling clinical trials for the treatment of adults with MDD and co-morbid AUDs, which involve a number of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Therefore, the findings of this study may not be generalized to populations of depressed patients who are typically excluded from these type of clinical trials (i.e. adolescents, patients with bipolar depression, psychotic MDD, patients actively abusing other illicit drugs, or women with peri-natal depression). Perhaps this phenomenon may explain why, in contrast to reports from non-clinical trial populations(Thase et al. 2001; Rushi et al. 2008; Sher et al. 2008), we found lower depression severity in patients participating in MDD/AUD clinical trials than MDD/Non-AUD trials. A final limitation is the relatively small number of clinical trials focusing in co-morbid MDD and AUD and, in particular, the complete

lack of data on a number of newer antidepressants (such as venlafaxine, duloxetine, desvenlafaxine, bupropion, or agomelatine).

6. CONCLUSIONS

Depression and alcohol abuse and/or dependence are among the most prevalent and costly disorders confronting the health care system. The two conditions often co-occur, complicating their clinical management and leading to greater overall severity and worse health-related outcomes of either disorder, as well as greater functional impairment, chronicity, risk of suicide, and relapse of both depression and drinking behaviors (Thase et al. 2001; Rush et al. 2008; Sher et al. 2008; Conner et al. 2009). Moreover, high rates of undertreatment of one or both conditions are often observed in patients with dual diagnosis (Watkins et al. 2001). One particular issue when treating such patients is the management of depression in the setting of ongoing alcohol abuse or dependence. Many concerns persist about confusing alcohol induced depressive symptoms with true depressive disorders, as well as the efficacy of antidepressants in patients with an active AUD. To date, there are a number of published reports on the use of antidepressant for the treatment of depression in patients who have alcohol and drug use disorders, ranging from case reports to moderately large, randomized, placebo-controlled trials, and there is some evidence that antidepressants may improve depressive symptoms in patients with concurrent AUDs. However, a considerable heterogeneity between trials often makes comparisons difficult and limits the generalizability of the results. This is where a quantitative review of the literature, namely a meta-analysis, can be helpful. A meta-analysis is the statistical analysis of a large collection of analysis results from different studies, for the purpose of integrating the findings and obtaining a quantitative estimate of the overall effect of a particular

intervention on a defined outcome. The basic purpose of meta-analysis is to provide the same methodological rigor to a literature review that is required from experimental research in order to produce a stronger conclusion than can be provided by any individual study. Therefore, the purpose of the present work was to conduct an updated and quantitative review of the literature on randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled antidepressant studies for patients with MDD/DD and co-morbid AUDs, through the use of a rigorous meta-analytic method, in order to provide further evidence that could help in the treatment of this particular patient population.

The results of our analysis suggest that antidepressants are effective in the treatment of depression in patients who also present with co-morbid AUDs. Moreover, we found that the risk ratio of responding to antidepressants versus placebo in trials on patients with comorbid AUDs and MDD/DD was not statistically significantly different from the risk ratio in trials on pure MDD/DD (1.34 versus 1.40 respectively, p=0.86). However, since we failed to detect a significant treatment effect for the SSRIs, the majority of evidence supporting the use of antidepressants in our meta-analysis derives from studies which involved nefazodone and the TCAs imipramine and desipramine. When interpreting this result, however, the small number of studies involving the SSRIs must be taken into account. More data on the use of the SSRIs and newer antidepressants, including the SNRIs and bupropion, for this select patient population are needed before any definitive conclusion should be drawn.

Moreover, we found that the efficacy of antidepressants was not influenced whether patients were actively drinking or recently sober, and we did not find any statistically significant correlation between the severity of baseline drinking and depression

treatment outcome. That the presence/absence or severity of recent sobriety does not predict outcome suggests that the decision whether to recommend antidepressants in this patient population should not be determined by these variables, at least as far as the potential efficacy of treatment is concerned.

In conclusion, the findings from this analysis have important practical consequences for both patients and clinicians, since they lend further support to the argument that antidepressants should represent first-line therapy for targeting depressive symptoms in patients with alcohol use disorders, a condition which is highly prevalent and is associated with high rates of medical and psychiatric comorbidity, disability, and increased use of general medical health services as well as psychiatric hospitalizations.

Figure 1: Flow diagram: trial identification and selection process

Records identified through database search (n = 7,349 )

Records screened (n = 7,364)

Full-text articles assessed for eligibility (n = 438)

Excluded (n=243)

100: presented data published elsewhere 25: focused on children and/or adolescents with

MDD

34: focused on depressive disorders other than MDD (i.e. bipolar depression, minor depression, psychotic depression), focused on perinatal depression, used DSM-II to diagnose MDD/DD, or did not state which criteria were used to define MDD/DD. 1: focused on treatment-resistant MDD 14: focused on patients with MDD and

co-morbid drug use disorders

61: focused on patients with MDD and co-morbid axis-III disorders

3: did not use an oral form of an antidepressant 3: shorter than 4 weeks in duration

2: did not employ the HDRS, MADRS or CGI

RCTs of MDD/DD with AUDs (n = 11) RCTs of MDD/DD

without AUDs (n = 184 )

Additional records identified through other sources (n = 15)

Excluded (n=6,926)

(duplicative reports, other topics, reviews)

RCTs included in quantitative synthesis

Figure 2: Efficacy of Antidepressants versus Placebo in MDD/DD with or without co-morbidAUDs 53.6 52.1 57.8 59.3 37.7 39.3 47.1 53.1 0 20 40 60 80 100 MDD/DD w ithout AUDs (313 contrasts) MDD/DD w ithout AUDs-SSRIs only (107 contrasts) MDD/DD w ith AUDs (12 contrasts) MDD/DD w ith AUDs-SSRIs only (7 contrasts) Antidepressants Placebo Response Rates (%)

• p=0.021 for AD vs Pbo in MDD/DD with AUDs

• p=0.263 for AD vs Pbo in MDD/DD with AUDs in trials with SSRIs

• p=0.859 comparing the RR of response of AD vs Pbo in MDD/DD with AUDs (n=891) and without AUDs (n=46,820)

• p=0.224 comparing the RR of response of AD vs Pbo in MDD/DD with AUDs (n=659) and without AUDs (n=19,780) specifically in trials with SSRIs

Table 1: Trials in MDD/DD patients with co-morbid AUDs

AD: antidepressant drug; MDD: Major Depressive Disorder; DD: Dysthymic Disorder; CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Author (year) Duration

in weeks AD arm (Dose)

Subjects (AD/placebo)

Abstinence required to enter the trial (duration) Concurrent therapy Diagnosis Mood Disorder AUD Altamura AC (1990) 12 Viloxazine (400 mg/d) 15/15 no no DD Dependence Mason BJ (1996) 24 Desipramine (50-300 mg/d) 15/13 7 days no MDD Dependence McGrath PJ (1996) 12 Imipramine (50-300 mg/d) 36/33 no Individual CBT MDD-DD Dependence or Abuse Cornelius JR (1997) 12 Fluoxetine (20-40 mg/d) 25/26 7 days Supportive psychotherapy MDD Dependence Roy A (1998) 6 Sertraline (100 mg/d) 18/18 14 days no MDD Dependence Roy-Byrne PP (2000) 12 Nefazodone (200-600 mg/d) 32/32 no Group CBT MDD Dependence Gual A (2003) 24 Sertraline (50-150 mg/d) 44/39 14 days no MDD-DD Dependence Moak DH (2003) 12 Sertraline (50-200 mg/d) 38/44 no Individual CBT MDD-DD Dependence or Abuse Hernandez-Avila C (2004) 10 Nefazodone (200-600 mg/d) 21/20 7 days Supportive psychotherapy MDD Dependence Kranzler HR (2006) 10 Sertraline (50-200 mg/d) 159/169 4 days Supportive psychotherapy MDD Dependence Pettinati H (2010) 14 Sertraline (50-200 mg/d) 40/39 no Individual CBT MDD Dependence

.5 1 5 10 Hernandez-Avila et al, 2004 Roy-Byrne at al, 2000 Cornelius et al, 1997 Pettinati et al, 2010 Altamura et al, 1990 Kranzler et al, 2006 (group A) Kranzler et al, 2006 (group B)

Combined Roy, 1998 Moak et al, 2003 McGrath et al, 1996 Mason et al, 1996 Gual et al, 2003 1.5

Favors Placebo Favors Antidepressant Risk Ratio

Figure 3: Effect of antidepressants in trials of MDD/DD with co-morbid AUDs. Solid line represents risk ratio=1; dotted line represents the pooled risk ratio, boxes represent risk ratios, box sizes are proportional to a study sample size; horizontal lines represent the 95% confidence interval of the risk ratio

8. REFERENCES

Akiskal HS: Dysthymic disorder: psychopathology of proposed chronic depressive subtypes. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 140(1):11-20

Akiskal H: [Dysthymic disorder and its treatment]. Encephale 1993; 19 Spec No 2:375-8 American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on Nomenclature and Statistics., American

Psychiatric Association. Committee on Nomenclature and Statistics.: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, American Psychiatric Assn., 1980

American Psychiatric Association. Work Group to Revise DSM-III.: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-III-R. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987

American Psychiatric Association., American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV.: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV. Washington, D.C., American Psychiatric Association, 1994

Brady J: The association between alcohol misuse and suicidal behaviour. Alcohol Alcohol 2006; 41(5):473-8

Brown SA, Schuckit MA: Changes in depression among abstinent alcoholics. J Stud Alcohol 1988; 49(5):412-7

Brown SA, Inaba RK, Gillin JC, Schuckit MA, Stewart MA, Irwin MR: Alcoholism and affective disorder: clinical course of depressive symptoms. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152(1):45-52

Conner KR, Pinquart M, Gamble SA: Meta-analysis of depression and substance use among individuals with alcohol use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat 2009; 37(2):127-37 Conner KR, Sorensen S, Leonard KE: Initial depression and subsequent drinking during

alcoholism treatment. J Stud Alcohol 2005; 66(3):401-6

Curran GM, Kirchner JE, Worley M, Rookey C, Booth BM: Depressive symptomatology and early attrition from intensive outpatient substance use treatment. J Behav Health Serv Res 2002; 29(2):138-43

Curran GM, Flynn HA, Kirchner J, Booth BM: Depression after alcohol treatment as a risk factor for relapse among male veterans. J Subst Abuse Treat 2000; 19(3):259-65 Davis LL, Wisniewski SR, Howland RH, Trivedi MH, Husain MM, Fava M, McGrath PJ,

Balasubramani GK, Warden D, Rush AJ: Does comorbid substance use disorder impair recovery from major depression with SSRI treatment? An analysis of the

STAR*D level one treatment outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend 2010; 107(2-3):161-70

Fava M, Evins AE, Dorer DJ, Schoenfeld DA: The problem of the placebo response in clinical trials for psychiatric disorders: culprits, possible remedies, and a novel study design approach. Psychother Psychosom 2003; 72(3):115-27

Feighner JP, Robins E, Guze SB, Woodruff RA, Jr., Winokur G, Munoz R: Diagnostic criteria for use in psychiatric research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1972; 26(1):57-63 Fortney JC, Booth BM, Curran GM: Do patients with alcohol dependence use more services?

A comparative analysis with other chronic disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1999; 23(1):127-33

Gamble SA, Conner KR, Talbot NL, Yu Q, Tu XM, Connors GJ: Effects of Pretreatment and Posttreatment Depressive Symptoms on Alcohol Consumption Following Treatment in Project MATCH*. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 2010; 71:7

Glenn SW, Parsons OA: Prediction of resumption of drinking in posttreatment alcoholics. Int J Addict 1991; 26(2):237-54

Greenfield SF, Weiss RD, Muenz LR, Vagge LM, Kelly JF, Bello LR, Michael J: The effect of depression on return to drinking: a prospective study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1998; 55(3):259-65

Guy W, National Institute of Mental Health (U.S.). Psychopharmacology Research Branch., Early Clinical Drug Evaluation Program.: ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. Rockville, Md., U. S. Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, National Institute of Mental Health, Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs, 1976

Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23:56-62 Hesselbrock MN, Meyer RE, Keener JJ: Psychopathology in hospitalized alcoholics. Arch

Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42(11):1050-5

Holder HD, Hallan JB: Impact of alcoholism treatment on total health care costs: a six-year study. Adv Alcohol Subst Abuse 1986; 6(1):1-15

Ilgen M, Moos R: Deterioration following alcohol-use disorder treatment in project MATCH. J Stud Alcohol 2005; 66(4):517-25

Ilgen MA, Tiet Q, Moos R: Outcomes of substance use disorder treatment in suicidal and nonsuicidal male patients. J Stud Alcohol 2004; 65(5):643-50

Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51(1):8-19

Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE: Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999; 56(7):617-26

Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62(6):617-27

Klein DN, Santiago NJ: Dysthymia and chronic depression: introduction, classification, risk factors, and course. J Clin Psychol 2003; 59(8):807-16

Kodl MM, Fu SS, Willenbring ML, Gravely A, Nelson DB, Joseph AM: The impact of depressive symptoms on alcohol and cigarette consumption following treatment for alcohol and nicotine dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2008; 32(1):92-9

Kranzler HR, Del Boca FK, Rounsaville BJ: Comorbid psychiatric diagnosis predicts three-year outcomes in alcoholics: a posttreatment natural history study. J Stud Alcohol 1996; 57(6):619-26

Kranzler HR, Mueller T, Cornelius J, Pettinati HM, Moak D, Martin PR, Anthenelli R, Brower KJ, O'Malley S, Mason BJ, Hasin D, Keller M: Sertraline treatment of co-occurring alcohol dependence and major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006; 26(1):13-20

Lejoyeux M, Huet F, Claudon M, Fichelle A, Casalino E, Lequen V: Characteristics of suicide attempts preceded by alcohol consumption. Arch Suicide Res 2008; 12(1):30-8

Lejoyeux M, Lehert P: Alcohol-Use Disorders and Depression: Results from Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis of the Acamprosate-Controlled Studies. Alcohol Alcohol 2010

Liappas J, Paparrigopoulos T, Tzavellas E, Christodoulou G: Impact of alcohol detoxification on anxiety and depressive symptoms. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002; 68(2):215-20 Marin DB, Kocsis JH, Frances AJ, Parides M: Desipramine for the treatment of "pure"