UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI MACERATA

DIPARTIMENTO DI

SCIENZE POLITICHE, DELLA COMUNICAZIONE E DELLE RELAZIONI INTERNAZIONALI

CORSO DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN GLOBAL STUDIES. JUSTICE, RIGHTS, POLITICS

CICLO XXXIII

EXPLORING INDUSTRY 4.0 FROM A COLLABORATIVE PERSPECTIVE

RELATORE DOTTORANDO

Chiar.ma Prof.ssa Dott.ssa Dominique Lepore Francesca Spigarelli

COORDINATORE

Chiar.ma Prof.ssa Benedetta Barbisan

1

Index

Introduction ... 4

CHAPTER 1 - INTEGRATING INDUSTRY 4.0 INTO SMART SPECIALIZATION STRATEGIES WITHIN A COLLABORATIVE PERSPECTIVE ... 8

1.1. Fostering a Collaborative Integration of S3 and Industry 4.0 ... 9

1.1.1. The disruptive role of Industry 4.0 ... 10

1.1.2. Exploiting the shared collaborative approaches of Industry 4.0 and S3 ... 13

1.1.3. Methodology - Analysis of the Smart Specialization Platform Sources ... 15

1.1.4. The current stage of integration between Industry 4.0 and S3 ... 17

1.2. Opportunities and challenges in a collaborative governance for Smart Specialization Strategies ... 20

1.2.1. Ensuring participation and ownership in S3 collaborative governance ... 21

1.2.2. Research Framework for the Systematic Literature Review ... 24

1.2.3. The role of stakeholders in S3 design and implementation ... 25

1.2.4. Opportunities and challenges of collaborative governance... 27

1.2.5. Facilitators for a collaborative governance ... 29

1.3. Final remarks ... 30

References ... 33

Appendix 1 – Article Accepted for the review ... 41

CHAPTER 2 - IS EUROPE READY FOR INDUSTRY 4.0? ... 50

2.1. Measuring Industry 4.0 readiness ... 50

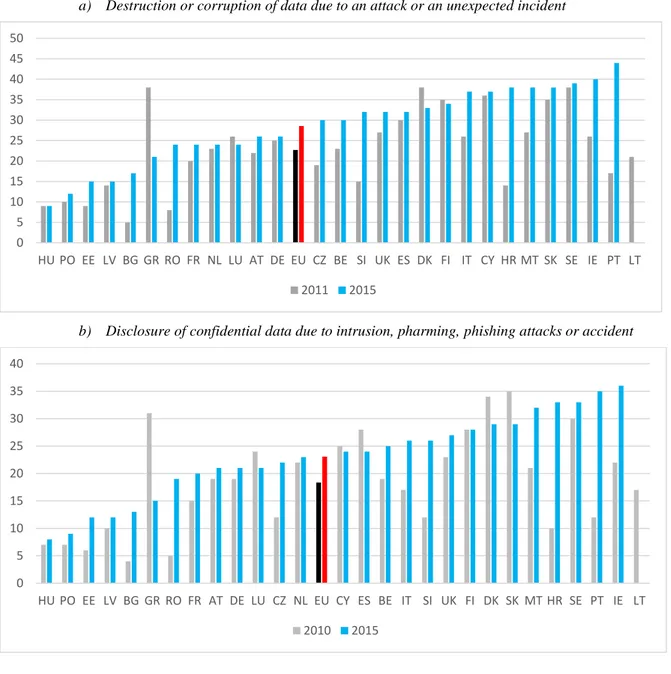

2.3. Cybersecurity: an enabling technology for Industry 4.0 ... 52

2.4. Cybersecurity within the S3 framework ... 53

2.5. Descriptive analysis: selection of variables ... 57

2.6. Descriptive Statistics ... 58

2.6.1. Cluster Analysis ... 60

2.6.2. Variations in cybersecurity among firms and society ... 62

2.7. Final remarks ... 67

References ... 69

Appendix 1 – Dataset ... 71

Appendix 2 - Security Policies per type of risk ... 72

Appendix 3 – Security concerns ... 74

CHAPTER 3- ASSESSING THE ITALIAN READINESS FOR INDUSTRY 4.0 ... 76

3.1. Assessing Industry 4.0 readiness in Italy ... 76

3.1.1. Assessing Industry 4.0 readiness at country and firm level ... 79

3.1.2. The variables selected for assessing Industry 4.0 readiness in Italy ... 80

2

3.2. Collaborative Governance in the regional Smart Specialization Strategies ... 87

3.2.1. A framework for assessing the role of the S3 collaborative governance ... 88

3.2.2. The role of S3 collaborative governance in Italy ... 89

3.2.3. The different systems of governance ... 92

3.2.4. The international exposure of the governance ... 96

3.2.5. Communicating the governance ... 97

3.2.6. TH and QH models ... 98

3.2.7. The Entrepreneurial Discovery Process ... 100

3.2.8. Monitoring and evaluating the governance ... 101

3.2.9. Mapping of the regional collaborative governance ... 104

3.3. Final remarks ... 105

References ... 107

Appendix 1. Dataset for Italian Industry 4.0 readiness ... 110

CHAPTER 4 - TOWARDS INDUSTRY 4.0 IN THE MARCHE REGION ... 112

4.1. Industry 4.0 development in the Marche region ... 112

4.1.1. Industry 4.0 competences ... 114

4.1.2. The methodology used for the Focus Groups sessions ... 115

4.1.3. The first session of focus groups: the regional digital development ... 116

4.1.4. The Second Round of Focus Groups: the 4.0 competences required... 117

4.2. Exploring knowledge sharing mechanisms among Industry 4.0 regional firms ... 120

4.2.1. The relationship between knowledge sharing and innovation ... 121

4.2.2. Managing knowledge in the 4th industrial revolution ... 124

4.2.3. Methodology of the multiple case studies in the Marche Region ... 125

4.2.4. Introduction of Industry 4.0 technologies in the regional firms ... 126

4.2.5. The impact of Industry 4.0 on collaboration ... 127

4.2.6. The collaborative enablers for introducing 4.0 technologies ... 130

4.3. Final remarks ... 131

References ... 134

Appendix 1 - Focus Group Organization ... 140

Appendix 2 – Interview ... 141

CHAPTER 5- DIGITAL INNOVATION HUBS AS INDUSTRY 4.0 KNOWLEDGE BROKERS ... 142

5.1. Understanding the relationship between knowledge management and innovation .... 142

5.2. Knowledge sharing in the open innovation paradigm ... 144

5.2.1. The need for open and integrated approaches for the digital transformation of SMEs 145 5.2. Methodology ... 148

3

5.3. The research setting ... 151

5.3.1. The European Context of DIHs ... 151

5.3.2. Focusing on the Italian system of DIHs ... 154

5.4. Discussion results... 156

5.4.1. Survey - exploring OI mechanisms ... 157

5.4.2. Interviews - DIHs as Knowledge Brokers... 158

5.5. Towards a model of digital imprinting ... 160

5.6. Final remarks ... 162

References ... 163

Appendix 1. Survey ... 171

Appendix 2. Interview ... 171

4

Introduction

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, known as Industry 4.0, is introducing advanced digital technologies that enhance connection between people, objects and systems (Spath, et al., 2013) by merging the physical and virtual world (Schmidt et al., 2015). In this interconnected scenario, collaboration between multiple stakeholders - sharing knowledge between them - is considered as an enabler to unlock the expected benefits of Industry 4.0. This calls for a detailed analysis of the practices that can favour such interactions (Camarinha-Matos et al., 2017). In such context, the Thesis presents the results of a three-year research project, carried out within the “Eureka” program jointly developed by the University of Macerata, ISTAO business school and the Region Marche. The scholarship attached to this industrial PhD program was aimed at investigating how to promote the involvement of multiple stakeholders (i.e. institutions, firms, academia and users) to boost the adoption of 4.0 technologies among regional firms.

This Thesis includes a regional report, a policy brief and seven papers, among which six were published and presented at national and international conferences, resulting from the research activities conducted in the three years.

The studies are based on the assumption that plans aimed at supporting the introduction of Industry 4.0 technologies should be considered and conceived within the regional Smart Specialization Strategies (S3). The objective of these strategies, which are developed based on the potential of each territory, is to lead Europe towards knowledge-intensive and added value activities by promoting technological development (European Commission, 2010). Further, collaboration, in terms of a collaborative governance, plays a leading role in S3, requiring the involvement of multiple stakeholders in their design and implementation.

Therefore, after reviewing why and how collaborative governance can support the integration of Industry 4.0 in S3, the level of readiness towards Industry 4.0 is assessed at European, Italian and Regional level, focusing on the Marche region case. The last chapter integrates all the three territorial levels of analysis, by considering the role of intermediary actors in supporting collaborative approaches for the introduction of 4.0 technologies.

The Thesis is structured as follows:

- Chapter 1 reviews how collaboration between multiple stakeholders can promote the integration of 4.0 technologies in the wider context of S3;

5

- Chapter 2 analyses, through descriptive statistics, the level of readiness of European countries for Industry 4.0, considering a set of variables linked to the enabling technology of cybersecurity;

- Chapter 3 provides an analysis of the Italian readiness towards Industry 4.0 at regional level, based on two different investigations. In the first one, the readiness is assessed through a set of variables representing firms’ willingness to invest in Industry 4.0 and the presence of favorable structural conditions. In the second one, instead, the level of readiness is analyzed, based on the role that the collaborative governance holds in the regional S3;

- Chapter 4 is divided in two parts. In the first part, a field research based on the methodology of the focus groups identifies the competences that need to be developed within the Marche Region for enhancing its level of readiness towards Industry 4.0, by consulting stakeholders from regional institutions, academia and firms; in the second part of the chapter, a multiple case study, based on face-to-face interviews with the innovation managers of four regional firms, allowed to identify which are the collaborative enablers for a successful introduction of 4.0 technologies;

- Chapter 5 focuses on the role of Digital Innovation Hubs (DIH), as structures introduced by the European Commission in 2016 under the Digitalizing European Initiative (DEI) for supporting the adoption of 4.0 technologies in a collaborative ecosystem. DIHs could fulfill the need for intermediary actors, recalled by the studies included in the previous chapters. This final chapter integrates all the previous levels of territorial analysis, mapping DIHs from the European level to the regional one, including the Marche Region.

The studies presented in this Thesis are having a positive impact on the development and spread of knowledge about Industry 4.0 in the Marche region. Firstly, the interviews included in the second part of Chapter 4 led to the introduction of a new specialization course on Data Science in ISTAO, which responds to the needs expressed by regional firms to have employees skilled in data management. In addition, the findings of the studies were presented at seminars and lectures at the University of Macerata, the Polytechnic University of Ancona, the Confucius Institute of Macerata and within ISTAO’ courses.

Moreover, the research on DIHs led to the creation of an interuniversity research group to study the development of DIHs in the national and European territory. The group is composed of experienced and early stage researchers from the University of Macerata, the Advanced School of Studies of Pisa and the Polytechnic University of Marche.

6

The knowledge acquired on the field was also exchanged within the Inter-university Centre for Applied Economic Studies to Industrial Policy (c. MET05), during regular monthly meetings. Within this academic group, I became actively involved as an Author and reviewer for the journal “l’Industria”, which allowed me to acknowledge and support emerging scientific contributions on Industry 4.0.

Furthermore, the studies conducted allowed me to be an active stakeholder within the Observatory 4.0 of the Region Marche and for the Inno Provement Interreg European Project, of which the Region is a partner. The findings of the studies were thus shared with other stakeholders in the business and academia field and contributed to defining the new regional law on Industry 4.0 that the Region Marche has recently enacted.

The overall research was enriched by international mobility experiences in two different DIHs. The first experience was held in Poland, at the Kosciuszko Institute Krakow, coordinator of the CYBERSEC HUB, specialized in cybersecurity. In the three months in the Polish DIH, I took part to a training course in the initiative "Smart Factories in new EU Member States", a project aimed at training selected organizations to become DIHs.

The second mobility experience was in a Science and Technological Park, Barcelona Technova, recognized as a DIH. Thanks to meeting within the Association of Science and Technology Parks of Spain (APTE), I was able to enrich my knowledge on the field.

In addition to the content included in Thesis, aware of the international dimension of Industry 4.0., other academic studies were undertaken considering the implementation of collaborative models for Industry 4.0 in China, according to the Made in China 2025 Plan.

The next steps will be to compare the two experiences of Industry 4.0 under the lenses of an inclusive model. To reach this aim, the methodological background will be strengthened in both the area of quantitative and qualitative research, to conduct studies that can provide a significant contribution to the literature and support the definition of practices able to support firms in the adoption of the new technological paradigm.

8

CHAPTER 1 - INTEGRATING INDUSTRY 4.0 INTO SMART SPECIALIZATION STRATEGIES WITHIN A COLLABORATIVE PERSPECTIVE

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, acknowledged as Industry 4.0, is likely to become more embedded within Smart Specialization Strategies (S3) in the next programming period 2021-2027.

S3, by supporting technological innovation based on the potential of each territory, could hold a strategic function in the adoption of Industry 4.0. More specifically, innovation policies as the S3 can favour the transaction towards Industry 4.0 based on the involvement of institutions, firms, research organisations and users.

The first chapter of the Thesis includes two different studies considering the common collaborative approach of Industry 4.0 and S3 as a driver to foster their integration. In fact, both policies call for the involvement of multiple stakeholders, as national and regional institutions, academia, firms and user, in their definition and implementation.

This collaborative mechanism is identified within the S3 framework in terms of collaborative governance, referring to processes and structures engaging non-state stakeholders to work together with the government in addressing public problems and in the creation of new policies. The chapter is structured as follows.

The first study presents the main features of the new technological paradigm and discusses why and how S3 in European countries can promote the development of Industry 4.0 actions in the upcoming programming period. In order to identify enablers that can favour their integration, evidence is gathered from selected technical reports, events and news press from the Smart Specialization platform.

Then, the second study discusses the opportunities and challenges of the S3 collaborative governance, through a systematic review of the literature. Based on the findings of the two reviews, future directions for guiding the revision of the S3 towards an effective Industry 4.0 integration within a collaborative perspective are presented.

9

1.1. Fostering a collaborative integration of S3 and Industry 4.01

The fourth industrial revolution, known as Industry 4.0 (Kagermann et al., 2013), as the previous three stages, is dominated by technical innovations. However, while mechanization and electrification of manufacturing processes characterized the first two industrial revolutions and informatization and automatization the third (Bauernhansl, 2014), the current revolution is driven by cyber–physical systems (CPS), which can be defined as engineered systems including interacting physical and computational components (Manyika et al., 2013). CPS, by connecting the real and the virtual world (Schmidt et al., 2015), are determining new ways of creating and offering value through ecosystems which go beyond individual value chains (Ibarra et al., 2018). These changes are calling for an analysis of which are the collaboration needs in the Industry 4.0 vision and how these can be satisfied (Camarinha-Matos et al., 2017). In this perspective, different countries around the world are introducing Industry 4.0 plans to support the adoption of the new digital technologies requiring the involvement of national and regional institutions, firms, academia, and users. However, the increasing advance of 4.0 technologies poses real challenges for industrial policy. With new capital-intensive technologies capable of relocating labour, discussion exists as to whether beneficiaries will belong to more dynamic regions, intensifying socio-economic and regional divides. At the European level, addressing these challenges is already embodied within the European Union’s (EU) Strategies for Smart Specialisation (S3), which have become the main component of the Europe’s 2014–2020 Innovation Union (Bailey et al., 2019), aimed at boosting innovativeness and competitiveness within the EU. Therefore, Industry 4.0 is likely to gain importance in the forthcoming S3 review (Marinelli et al., 2018). According to the S3 guide (2012), as the economic conditions are rapidly changing within and outside the region, it is necessary to regularly adapt and update the S3 (Foray et al., 2012, p. 62).

Innovation policies as the S3 can favour the transaction towards Industry 4.0 based on the support of local industry, research organisations and other key stakeholders.2 Industry 4.0 is expected to be more rooted in S3 within the next programming period 2021-2017, which will see a further consolidation of the S3 framework.3 These changes will lead to revise accordingly

1 This first study is a preliminary version of the publication: Lepore, D., & Spigarelli, F. (2020). Integrating Industry 4.0 plans into regional innovation strategies, Local Economy, 35(5),1-15.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094220937452

2 European Parliament- Directorate General for Internal Policies Policy Department (A): Economic and Scientific Policy Industry 4.0:

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/570007/IPOL_STU(2016)570007_EN.pdf 3 Commissioner for Regional policy Corina Creţu said: "Smart specialisation will be more important than ever

10

national and regional S34. The integration of Industry 4.0 and S3 can take place starting from

their shared collaborative logics and approach. From a theoretical perspective, the quadruple Helix Models (QHMs), involving national and regional institutions, academia, firms and users, represent the identity of the emerging industrial revolution (Steenkamp, 2019; Schütz et al., 2019; Bellandi et al., 2019). QHMs are also part of the S3, according to which the involvement of different stakeholders is the main driver for local structural economic change and development (Foray et al., 2012).

In order to provide indications on how S3 can integrate Industry 4.0 in the upcoming programming period, the sources available on the Smart Specialization Platform of the EU are analysed. The sources refer to the official reports included in the knowledge repository and to outcomes of event and news sections. The existing connection between Industry 4.0 and S3 confirms to be based on collaborative enablers, especially in terms of interregional collaboration. Another collaborative driver that could guide the integration of the two policies is represented by Digital Innovation Hubs (DIHs), as European structures introduced from the Digitizing European Initiative (DEI) of 2016 to favour the adoption of 4.0 technologies among Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs). However, the connection between the two policies is still at its initial stage and greater changes are expected in the future reviews of the S3. The first study is structured as follows. After reviewing Industry 4.0 features and national plans, the collaborative logics of the revolution are discussed underlining the points of connection with the S3 framework. Secondly, after describing the methodology, the outcomes are presented providing a model of reference on the current stage of integration. Lastly, conclusions and policy implications are drawn.

1.1.1. The disruptive role of Industry 4.0

The fourth industrial revolution is described as the increased digitization and automation of value chains (Kagermann et al., 2013) enhanced by interconnections between people, objects and systems (Spath, et al., 2013). McKinsey Global Institute (Manyika, 2013) identifies the fourth industrial revolution as the age of CPS, described as systems that integrate computation, networking, and physical processes. CPSs include technologies that span from mobile devices,

things: more partnership and more ownership, especially in those regions that need to catch up the most. This initiative will help prepare the ground for solid innovation strategies in the post 2020 period."

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_4184

4 Countries can opt for a national S3 in addition to regional strategies. In this case national and regional S3 have to be coherent and complementary: https://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/faqs-on-ris3

11

the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, cyber security, and 3D printing. Unlike traditional network embedded systems, the IoT connects different devices from various manufacturers for a variety of purposes (Kovatsch et al., 2012).

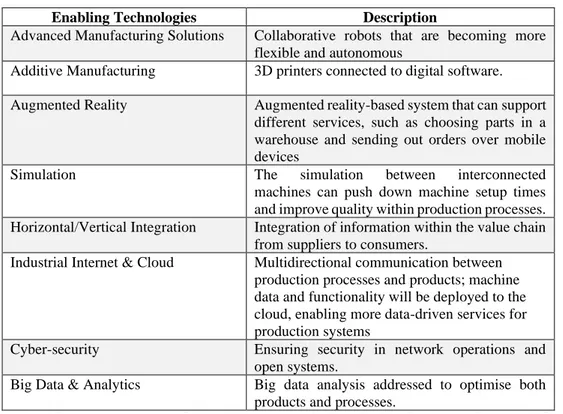

This revolution based on CPS is integrating heterogeneous data and knowledge (Lu, 2017), merging the digital and the physical workflow (Schmidt et al., 2015). However, a taxonomy of digital technologies does not yet exist and the most applicable one is suggested by the Boston Consulting Group (Rüßmann et al., 2015) and included in the Italian Industry 4.0 Governmental Program of 2017. According to this definition, as presented in the Italian Industry 4.0 and as reported in the description of Ciffolilli and Muscio (2018), the 4.0 technologies are those listed in Table 1.

Table 1 – Industry 4.0 enabling technologies

Enabling Technologies Description

Advanced Manufacturing Solutions Collaborative robots that are becoming more flexible and autonomous

Additive Manufacturing 3D printers connected to digital software. Augmented Reality Augmented reality-based system that can support

different services, such as choosing parts in a warehouse and sending out orders over mobile devices

Simulation The simulation between interconnected machines can push down machine setup times and improve quality within production processes. Horizontal/Vertical Integration Integration of information within the value chain

from suppliers to consumers.

Industrial Internet & Cloud Multidirectional communication between production processes and products; machine data and functionality will be deployed to the cloud, enabling more data-driven services for production systems

Cyber-security Ensuring security in network operations and open systems.

Big Data & Analytics Big data analysis addressed to optimise both products and processes.

Source: Piano Industria 4.0; Ciffolilli and Muscio (2018); Boston Consulting Group (2015)

Another typical concept of Industry 4.0 is the Smart Factory, identified as a manufacturing solution that provides flexible and adaptive production processes that will be able to solve problems emerging on a production facility (Radziwon et al., 2014). The new technological paradigm is transforming firms’ products and services both in vertical and horizontal value chains (Sarvari et al., 2018).

Due to the disruptive impact of 4.0 technologies, different countries around the world have introduced plans to support firms in the adoption of new digital and connected technologies

12

(see Table 2), especially among Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs). Germany was the first country to do so, introducing the concept of Industry 4.0 as one of the key initiatives of the German high-tech strategy at the Hannover Fair in 2011 (Drath & Horch,2014).

After Germany, the USA introduced the Advanced Manufacturing Partnership and Denmark the Made in 2012. Other countries followed one year later, as Belgium with its Made Different

plan and Australia with the Next Wave of Manufacturing. Instead, Italy was one of the last

countries to propose its governmental program Industria 4.0 in 2016, which was adopted the following year. As underlined by the European Commission (2017), the participation of diverse actors is a defining strength of the national Industry 4.0 policies. In particular, the collaboration with industry stakeholders is most frequently cited as a driving force by the implementing authorities.

However, since Industry 4.0 plans are developed at national level, in order to ensure their effective implementation, it becomes necessary to consider the technological potential of each region. The analysis of technological potential is included within the European S3, which are conceived as place-based policies. The place-based approach assumes that policy priorities should differ between different regions. It also suggests that regional policies should be built on local capabilities, encouraging innovative strategies, based on local and non-local actors and knowledge (Barca et al., 2012).

Table 2. Industry 4.0 plans around the world

Country Plan Year

Germany Industrie 4.0 2011

USA Advanced Manufacturing Partnership 2012

Denmark Made 2012

Belgium Made Different 2013

Australia The next wave of manufacturing 2013

Netherlands Smart Industry 2014

UK Catapult- High value manufacturing 2014

Canada Conestoga: Centre for Smart Manufacturing 2015 South Korea Manufacturing Innovation 3.0 Strategic Action Programme 2015

Japan Industrial Value Chain Initiative 2015

China Made in China 2025 2015

India Make in India 2015

France Industrie du Futur 2015

13

Portugal PRODUTECH 2016

Italy Piano Nazionale Industria 4.0 2017

Source: Own elaboration

1.1.2. Exploiting the shared collaborative approaches of Industry 4.0 and S3

Collaborative networks connecting different domestic and foreign institutions, firms, academia and users are becoming an enabler for adopting 4.0 technologies. The horizontal and vertical integration of the value chain, fostered by advanced and connected technologies, is extending firms’ boundaries towards new organizations and stakeholders (Ibarra et al., 2018). Therefore, it becomes necessary to identify practices that can promote collaboration between different stakeholders considering the multiple needs involved (Camarinha-Matos et al., 2017). In fact, innovation activities are likely to be found in relation to external collaboration as a source of greater productivity (Sánchez-Sellero et al., 2015). These developments are shaping Global Value Chains (GVC) impacting what products are traded, what is exported from where and imported to where, and where jobs are sustained. The spread of additive manufacturing has the potential to reduce trade in finished goods while the local availability of raw materials would also reduce trade in intermediate goods (Strange & Zucchella, 2017). However, SMEs are still reluctant in the integration of the Industry 4.0 concept (Muller et al., 2015; Schröder, 2016). Facilitating conditions such as technology infrastructure, IT knowledge, compatibility with current processes are necessary for promoting the adoption of new technologies, especially among these firms (Khayer et al., 2019) for which collaborative strategies can be beneficial. Therefore, the dynamics of Industry 4.0, cannot be solved by any single sector alone, suggesting that governance must become a multi-stakeholder endeavour. This creates a new role for the private sector and academia, which must work alongside public officials to provide expertise on the technologies they are being developed, focusing on their applications and potential consequences. Nevertheless, governments remain central actors in policy development and enforcement by defining the parameters of governance protocols for introducing technology innovations (World Economy Forum, 2017). This means that academia, industry and government must be connected to create the necessary conditions to innovate, starting from the creation of a THM (Etzkowitz & Carvalho de Mello, 2004). Such relationships have been extended to the QHM by incorporating civil society (Carayannis & Campbell, 2009), as the identity of the emerging industrial revolution, requiring that managements adopt the model as a frame of reference, whilst further studies should test and

14

improve the QHM (Steenkamp, 2019). Social actors express the desire for more opportunities to introduce scientific and technological considerations on the new enabling technologies (Schütz et., 2019). In this sense, policy makers should protect and share initiatives for productive development within QH projects. Collaborative schemes are needed, but they cannot be based on traditional governance solutions (Bellandi et al., 2019).

Industry 4.0 in this collaborative perspective has the potential to shape the S3, whose objective is that of leading Europe towards knowledge-intensive and higher added value activities (European Commission, 2010). The smart specialization approach is not a novelty but an update respect to previous programming of structural funds. Precisely for the period 2014-2020 regions are asked to develop S3 as a precondition to access to European structural funds. More specially, S3 are conceived as programs foresting an economic transformation by supporting technological innovation based on the regional potential. In this sense, S3 are presented as a multi-level challenge (Morgan, 2017), included in a system that takes decisions based on preferences and capabilities of recipients in their different juridical levels. The smart specialisation conditionality refers explicitly to the need to regularly update the S3 based on external conditions.5 The possibility of integrating Industry 4.0 in current S3 is calling for an analysis of how the industrial revolution can represent a priority for S3 thematic areas6.

Collaborative models could drive this integration, as explicitly recalled by the European Commission when referring to S3. As underlined by Grillo and Landabaso (2011), regions which are able to develop the institutions and policies which promote these interactions through public-private partnerships and across the governance ladder are likely to be successful in developing a process of sustained and sustainable growth, no matter what their current development. Both the models of TH and QH are in line with the approaches fostered by S3, according to which the involvement of different stakeholders is the main driver for the local economic, institutional and social system development (Foray et al., 2012). Such approaches are likely to be found in the S3 Entrepreneurial Discovery Process (EDP), which is a bottom-up approach required by the European Commission to identify regional priorities based on the potential of each Region in science and technology. In this phase, each Region appoints individuals or organizations to collect information on the activities that must be developed directly from the market and private sector (Landabaso, 2014). The term entrepreneur is considered in a wide sense and does not only refer to business enterprise. The smart

5 Each region has to define a monitoring and evaluation system, which must consider which are the processes and structures in charge of the revision stage (Foray et al., 2012)

15

specialisation process should also include research leaders, education institutions, inventors, non-government organisations (NGOs) and societal associations. The role of these groups of actors can vary in terms of their involvement within each region (Mieszkowski & Kardas, 2015). These differences can be explained by the characteristics of actors, structures, and power relationships (Aragon et al., 2019). Referring to the EDP process, scholars have indeed suggested models for stimulating demand-led policies as a vehicle for entrepreneurial discovery where users and producers engage in sharing and networking of information (Talbot, 2016). Moreover, the involvement of regional authorities in EU, which are already engaged in adopting Industry 4.0 strategies at the regional level, often recall the framework of S3 seeking greater policy alignment between the national and regional level (European Commission, 2017). Nevertheless, the implementation of S3 seems to be highly challenging for regions faced with the adoption of these new bottom-up approaches (Iacobucci, 2014).

1.1.3. Methodology - analysis of the Smart Specialization Platform sources

In order to identify how Industry 4.0 plans can be integrated within the framework of S3, the sources available on the Smart Specialization Platform in the EU framework7 filtered by the

keyword “Industry 4.0”, were analysed. The sources refer to the knowledge repository (external publication, factsheets, guidance, S3 policy briefs, science for policy reports, technical reports, working papers) in all S3 sections (S3 governance, targeted support, beyond S3, S3 communities, interregional cooperation, S3 guidance). Further sources are collected with the same approach from the event and the news section available on the online platform. The search led to identify n. 24 sources in the knowledge repository, n. 14 events and n.3 articles in the news section. From the content analysis, n. 7 reports, 13 events and 3 news were identified. Then following a snow-ball strategy (Krippendorff, 2004) further sources were included. Precisely, follow-up documents of events and monitoring reports from interregional partnerships and additional interregional partnerships recalled in the news section were investigated, as listed in Table 3

Table 3 – Sources analysed8

Reference Source Type Content

Rissola, G., & Sörvik, J. (2018). Digital Innovation Hubs in Smart Specialisation Strategies,

JRC Technical Report Discussion on how to develop a productive S3- DIH integration

7 Smart Specialization Platform provides advice to EU countries and regions for the design and implementation of their S3: Provide guidance material and good practice examples Inform strategy formation and policy-making Facilitate peer-reviews and mutual learning Support access to relevant data Train policy-makers.

16 European Commission (2017) Thematic

Smart Specialisation

External Publication Office Document

Focus on how interregional collaborations can increase innovation investment

Miörner, J., Rissola, G., Sörvik, J., & Wernberg, J., (2019). Putting Digital Innovation Hubs into Regional Context. A European survey

JRC technical report European survey on DIHs

Kroll, H. et al. (2016) An analysis of drivers, barriers and readiness factors of EU companies for adopting advanced manufacturing products and technologies

Report of the European Commission’s Directorate General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs

Study to identify the main reasons for Advanced manufacturing technologies (ADM) adoption

Larrea, M., Estensoro, M. &

Pertoldi, M. (2019). Multilevel governance for Smart Specialisation: basic pillars for its construction

JRC Technical Reports Discussion on how multilevel governance (MLG) operates in S3

Interregional cooperation for Smart Specialization on SME integration to Industry 4.0

Monitoring Reports January 2017 – June 2018; July 2018 - December 2018; Jan 2019 - June 2019

Presentation of mission, objectives and advances of the partnership

Interregional cooperation for Smart Specialization on Efficient and Sustainable Manufacturing

Monitoring report July to December 2019

January to June 2019 July to December 2018 January to June 2018

Presentation of mission, objectives and advances of the partnership

Interregional cooperation for Smart Specialization on Cybersecurity

Monitoring report July to December 2019

January to June 2019 July to December 2018 January to June 201

Presentation of mission, objectives and advances of the partnership

Marinelli E., Tolias Y., Bertamino F., Metaxas M., &

Grisorio J. (2018). Squaring the circle: lessons from the role-playing exercises on S3 regional and multi-level governance

Technical report by the Joint Research Centre (JRC)

Discussion on outcomes of role playing exercise from S3 working group to address governance in S3

Modernisation of the Food Industry through Industry 4.0 and Digitisation with particular focus on developing transdisciplinary competencies, skills and demonstration projects

Event: 19-20 September 2019, Hungary

Workshop for creating a forum of regional actors in food processing, development of Industry 4.0, ICT and advanced manufacturing

JRC – KAIST Joint Workshop on Emerging Issues of Smart Specialisation and Regional Innovation in the Age of the 4th Industrial Revolution

Event: 25 Jul 2019 - 26 Jul 2019, Spain

Workshop organized by JRC and of KAIST 4th Industrial Revolution Intelligence Center for identifying collaborative research projects. European Week of Regions and Cities on

Bottom-up partnerships for industrial modernisation

Event: 8-11 October 2018, Belgium

Workshop featuring cases of regions in bottom-up and inter-regional partnerships with the support of the S3 Platform for Industrial Modernisation. Collaboration Opportunities and Synergies

between RIS3 and EIT-RIS

Event: March 2018, Slovenia

Event for facilitating potential collaboration to exploit synergies between RIS3 and EIT-RIS.

JRC Macro-Regional Innovation Week Event: 24 Jan 2018 - 26 Jan 2018, Italy

Promotion of JRC's research infrastructures and laboratories and showcase

Digital Innovation Hubs and Smart Specialisation Workshops

Event: Nov. 2017, Brussels Presentation of the series of workshops on DIHs

17 Central European cooperation workshop

and Watify Matchmaking Event on Industry 4.0

Event: 20-21 September 2017,

Hungary

Workshop on S3 Cooperation in Central Europe exploring potential cooperation in Industry 4.0.

Watify webinars – what is coming up in? Event: Online

September and October 2017

Presentation of upcoming webinars

S3P Agrifood - Technical meeting of the thematic partnership on “Traceability and Big data”

Event: 28-29 March 2017, Spain

Technical meeting of thematic partnership “traceability and big data” The first Steering Committee meeting of

the Smart Specialisation Platform for Industrial Modernisation 2017

Event: March 2017, Belgium

Announcement of the first Steering Committee meeting of the S3 Platform for Industrial Modernisation gathered 16 EU regions,

Kick-off Event of the Smart Specialisation Platform on Industrial Modernisation and launch of the Watify campaign

Event: 16-17 November 2016, Spain

Kick-off event of the platform open to all European regions committed to industrial modernisation.

RIM Plus Workshop "Connecting innovation community of Industry 4.0 and smart systems"

Event: 27 April 2016, Belgium

Targeted at the regional innovation stakeholders interested in advanced technologies

Conference 'Big Data and Society – Between Causality and Correlation'

Event: 15- 16 February2016, Germany

Thematic Platform Digital Growth and ICT Germany

Outcome of the second assessment round of TAF applications announced

News: Jan 2020 The second assessment round of December 2019 from which TAF was awarded five projects took place. The three Smart Specialisation Thematic

Platforms join forces in Bilbao (Spain) for the first time

News: 26 Nov 2018 Participants from all over the EU will come together to explore learning, networking and business interregional opportunities into agri-food, energy and industrial modernisation.

Watify webinars – what is coming up in March 2018?

News: 13 March 2018 Presentation of webinars of experts on technological transformation.

1.1.4. The current stage of integration between Industry 4.0 and S3

Based on the analysis of our sources, the linkage between Industry 4.0 and S3 confirms to rely on collaborative approaches within and between countries, especially at the regional level. The main references are found in three S3 thematic platforms, namely, industrial modernization, food and energy. These platforms have been launched by the European Commission in 2015 to provide an interactive and participatory environment, supporting interregional cooperation in the three mentioned areas. In reference to industrial modernization, among the best regional practices presented by Rissola et al. (2018) the connection between S3 and Industry 4.0 is found in the feedback and monitoring role that Industry 4.0 plans can hold for S3 and in the involvement of Industry 4.0 structures - as Competence Centres - in the S3 definition. The role of this thematic platform is endorsed by the event held in 2018 at Bilbao for discussing interregional opportunities in the three thematic platforms, with the aim of promoting transition towards Industry 4.0’s goals and improve the position of regions in GVC.

18

The integration between the S3 and Industry 4.0 is further reinforced by the workshop Modernisation of the Food Industry through Industry 4.0 and Digitisation of Hungary (2019), aimed at exchanging experiences on national Industry 4.0 and S3 strategies.

Further, Industry 4.0 enabling technologies are recalled in the report of Kroll et al. (2016) presenting advanced manufacturing technologies as the key to industrial competitiveness, growth and job creation. The report also discusses the need to link these technologies to S3 policies, starting from industrial modernization. Other enabling technologies refer to 3D printing and advanced manufacturing for energy applications (European Commission, 2017). A recurring topic when considering both Industry 4.0 and S3 is related to the challenges faced by SMEs in the digital transition. Both Miörner (2019) in the European Survey and Larrea et al. (2019) in their report of S3’s multilevel governance discuss SMEs’ challenges in adopting digital technologies in the Industry 4.0 transition. In this sense, a remarkable partnership is the Interregional cooperation for Smart Specialization on SME integration to Industry 4.0. The main objective of the partnership is to include SMEs in the Industry 4.0 paradigm by increasing support in specialised digital services. As pointed out in the mission statement, to accomplish this objective, cross-regional coordinated actions are required.

The 4.0 priorities included in the partnership are distinguished between developing and advanced areas. Developing areas are mainly focused on Industrial Cyber-security, access to cloud, smart logistics and network management, virtual reality and simulation technology. On opposition, predictive modelling and maintenance, production performance and monitoring systems are addressed for developed areas. In addition, from the analysis of the monitoring reports of the partnership, a leading role is found to be held by Tuscany in Italy as one of the leading regions of the partnership. The region has introduced innovative tools developed at the regional level for implementing machine learning techniques into the EDP to identify experts in Industry 4.0 within the Tuscan ecosystem. The interregional partnership is also mentioned in the news sections as one of the projects that has been awarded by the Technical Assistance Facility (TAF) and thus will receive support on a wide range of topics, which can include advice on appropriate financial structuring and mix of funding sources, investment vehicles, governance rules, business models, financials, and intellectual property rights.

Other projects awarded reveal to be strongly linked to Industry 4.0 as the interregional partnership on Efficient and Sustainable Manufacturing (ESM), which recalls Industry 4.0 technologies applied in the manufacturing environment to realise high performing and human centred digital virtual factories. The partnership is exploring the potential collaboration of the industry on issues related to the Circular Economy. Thanks to this project, the participating

19

regions had the possibility to identify and establish a link among their regional groups and the ESM network with a focus on Industry 4.0.

Another interregional partnership linked to 4.0 enabling technologies is the interregional partnership on cybersecurity for which participating national and regional authorities and representatives from the QHM have already developed a wide range of activities supporting the cybersecurity development.

Lastly based on technical reports, a potential intermediary facilitating the integration between Industry 4.0 and S3 is found in DIHs as specified by Rissola et al. (2018). DIHs can boost Industry 4.0 in relation S3 implementation, especially in the field of advanced manufacturing. To the same extent, DIHs are presented as intermediaries of SMEs and Public Administrations for digitalisation and technological transfer while facilitating interregional collaboration. Miörner (2019).

Their role is confirmed also by the DIHs and Smart Specialisation Workshops presented in Brussel in 2017, as specific training held at interregional level among European DIHs.

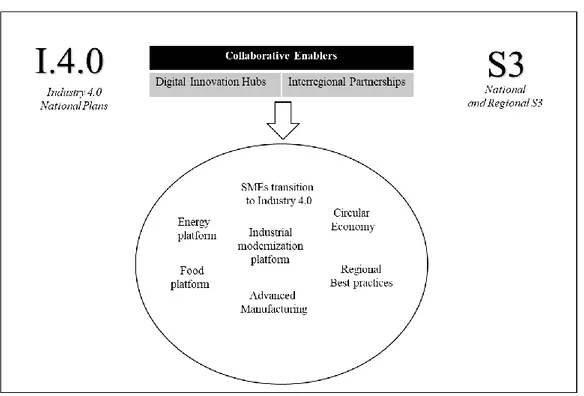

Figure 1. The current stage of integration between Industry 4.0 and S3

Source: Own elaboration

In short, considering the possible integration between Industry 4.0 and S3, based on the sources retrieved, two main “collaborative enablers” were identified as represented by interregional partnerships and DIHs. These enablers, which are both based on collaborative logics, typically found in S3 and Industry 4.0 plans, are mentioned within a set of common areas, as indicated

20

in Figure 1. Specifically, the integration in European regions is starting to take place in the thematic platforms of industrial modernization, food and energy. Moreover, among the areas of integration there is attention to the SMEs’ transition to Industry 4.0 as the core mission of DIHs and interregional partnerships.

Further, the circular economy as part of many S3 may exploit the benefits of 4.0 technologies, as recalled by the ESM. Among enabling technologies, advanced manufacturing is the main one considered in workshops and technical reports, finding applications in S3 areas. Lastly, a set of regional best practices proves the intention to integrate Industry 4.0 and S3 by considering the role of Industry 4.0 plan in the evaluation and revision of the S3 at the regional level. On the assumption of favouring their integration, the following study considers more in deep the collaborative approach followed by S3 in terms of collaborative governance.

1.2. Opportunities and challenges in a collaborative governance for Smart Specialization Strategies9

As mentioned in the first study, S3 with the objective of leading Europe towards knowledge-intensive and higher added value activities attribute a leading role to the involvement of different stakeholders for the local economic, institutional and social system development (Foray et al., 2012). In fact, the proposed S3 by the European Commission have introduced a great emphasis on achieving a “collaborative governance” (Foray et al., 2012).

Collaborative governance refers to those processes and structures engaging non-state stakeholders to work together with the government in defining new policies or addressing public problems. The approach required by these policies finds evidence in the literature where interactions by different actors become relevant in innovation processes, especially in the form of TH helix systems based on the relationships between government, industry and university (Etzkowitz et al., 2007).

However, the creation, dissemination and use of new ideas and knowledge resulting governance. from interactions of different actors (Antonelli & Ferrao, 2001) is exploring an extension, with the inclusion of the civil society. The model is therefore evolving towards a QH system, including civil society, as a more effective way of generating intense

9 The second study is based on the publication Lepore, D., & Spigarelli, F. (2018). Opportunities and challenges in a collaborative governance for Smart Specialization Strategies - A systematic review of the literature,

21

experimentation and discoveries, enhancing at the same time innovativeness (Carayannis & Grigoroudis, 2016).

Therefore, the aim of the second study is to identify through a systematic review of the literature the emerging opportunities and challenges towards the definition of facilitators for local stakeholders leading to an effective Therefore, after selecting articles that dealt both with S3 and with a multi-stakeholder approach, a content analysis was undertaken.

The analysis was addressed to understand the role recognized to stakeholders in the strategy development together with the opportunities, challenges and facilitators for an effective collaborative governance. The contribution, aware of the need to address the on-going topic, advances the state of the art by extracting and discussing the major outcomes and gaps providing a reference for policy makers and researchers. After describing more in detail, the role of S3, the emphasized collaborative governance is considered referring to the triple and quadruple helixes. Then, research questions and methodology of the systematic review of the literature are illustrated. The final paragraphs are devoted to the discussion.

1.2.1. Ensuring participation and ownership in S3 collaborative governance

S3 as a regional policy framework driven by the concept of innovation growth, emerge to provide a suitable answer to the global financial and economic crisis (Foray, 2015). The policy was designed to find an explanation and strategy for the large R&D gap existing between Europe and key trading partners, such as China and US. The recognized gap was mainly explained by the structural differences existing in the industrial structure of the countries (McCann & Ortega-Argilés, 2016). These differences were attributed to a diverse knowledge distribution across the European economy for high-tech and R&D intensive sectors, inefficient resource allocation and weak learning processes (Pontikakis et al., 2009).

The S3 appears as a key process addressed for structural change towards more knowledge-intensive and higher added value activities (European Commission, 2010). Precisely, for the current programming period (2014–2020), regional and national policy makers are required to develop S3 before investing European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) resources in research and innovation policy. The objective of developing S3 is to leverage public and private funds towards smart specialisation priorities, which should be identified through an entrepreneurial discovery process (EDP). National or regional managing authorities, together with stakeholders such as research institutions, industry and social partners, are called to identify and produce information about new activities and develop roadmaps to realise their potential. Different studies started to consider S3 trying to help regions develop smart

22

strategies (Coffano & Foray, 2014), while others focused more on the lack of clarity in the process and in its implementation (Capello & Kroll, 2016), especially addressing to regions in Central and Eastern Europe (Karo & Kattel, 2015).

Indeed, in the following years, a focused effort is considered necessary to address the most important regional challenges, as increasing R&D intensity and strengthening cooperation networks; enhancing also the quality of human capital and facilitating its absorption; finding an optimal balance between traditional specialisations and a “smart diversification”. In this context, the new smart specialisation strategy and the operational programmes seem suited to fulfil these needs even if further initiatives are recommended (Ciffolilli, 2014).

Overall, the implementation of S3 seems to be highly challenging for regions faced with the adoption of new approaches (Iacobucci, 2014). Among the new approaches, the involvement of stakeholder is a central argument that is emphasized by the S3 Guide (2012), which addresses governance as a sophisticated form of shared process management, between actors all striving towards a shared future outcome. The proposed S3 strategies have introduced a great emphasis on governance amongst different actors whose relationships are considered to make the difference for an effective governance process. Indeed, the wide view of innovation automatically implies that stakeholders of different types and levels should participate in the design of innovation strategies (Foray et al., 2012). When relating to governance as outlined by the S3 Guide (2012), we will refer to the literature based on public decision making and management involving both public and private actors, known as collaborative governance. Collaborative governance can be defined as the governing arrangement where one or more public agencies directly engage non-state stakeholders in a collective decision-making process that aims to make or implement public policy or manage public programs or assets (Agranoff & McGuire, 2003). Collaborative governance refers to those processes and structures engaging non-state stakeholders to work together with the government in addressing public problems and in the creation of new policies. In this approach, diverse arrays of stakeholders from the public, private, and non-profit sectors are convened for one or more public purposes, including policymaking, policy implementation, or coordinating public service delivery tasks (Emerson et al., 2012). The benefits of collaborative processes include greater responsiveness to complex situations and more deliberation than traditional governance processes (Leach, 2006). Collaborative governance may produce more effective, efficient, and flexible policies (Sousa & Klyza, 2007) with greater public acceptability.

Proponents of collaborative governance argue that the complexity and uncertainty - that are attached to great societal challenges - are best addressed through engaging those most directly

23

interested and affected by them, including individuals with relevant expertise (Emerson & Nabatchi, 2015). In this governance setting, diverse stakeholders are engaged in public policy making and management. The aim is to encourage inclusion and participation in the policy process along with connecting stakeholders’ various expertise, resources, and support (Emerson & Nabatchi, 2015).

The S3 strategies have introduced a great emphasis on governance amongst different actors, especially in the EDP. The EDP is an interactive process in which market forces and private sector discover and produce information about new activities to be developed, while the government evaluates the outcomes and empowers the most capable actors (Landabaso, 2014). The multi-stakeholder approach becomes relevant in innovation processes since cooperation dynamics, various knowledge networks and mechanisms lead to creation, dissemination and use of new ideas (Antonelli & Ferrão, 2001). The requirement of involving stakeholders in major policies is conceived as one of the most crucial implications for innovation policy (Martin, 2010). In fact, the approach presented by S3 finds evidence in the literature where interaction by different stakeholders become relevant in innovation processes, especially in the form of triple helix systems (Etzkowitz et al., 2007). This model is a strong environment of parallel relationships between (national or regional) authorities, the wider business community (industry) and academia (including other research-focused institutions). The approach places more emphasis on the role of each one of these categories of actors in the innovation process. (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 1995) The systemic nature of the triple helix interactions reflects, to a large extent, the interactions as manifestations of social systems, characterised by action (Parsons & Smelser, 1956) and communication (Shannon, 1948).

However, to guarantee a truly place based entrepreneurial process of discovery, it is imperative that new demand side perspectives, as consumer and innovation users, are represented with intermediaries offering knowledge based and market facing prospective. The approach of quadruple helix was developed by maintaining the interaction of the spheres of the third helix as academia, industry and government, while formalising the role of civil society (Yawson, 2009). Therefore, extending the range of actors towards a fourth category identified as innovation users (Arnkil et al., 2010). This means going beyond a triple helix approach towards a quadruple one as underlined already by the S3 guide (2012).

According to this model, citizens would not only be involved in the actual development work, they would also have the power to propose new types of innovations, which connect users to stakeholders across industry, academia, or government (Arnkil et al., 2010). By applying a quadruple helix approach, regional policymakers are more likely to enable a place-based

24

entrepreneurial process of discovery, which would generate intensive experimentation and discoveries. Even if a quadruple helix approach is suitable for developing S3, it requires a great effort from which becomes evident the need to define measures that can keep the momentum generated in the original initiatives and demonstrate the value of their exercise (Carayannis & Grigoroudis, 2016).

1.2.2. Research framework for the Systematic Literature Review

In the context of a collaborative governance for Smart Specialization Strategies (S3), a systematic review of the literature was undertaken to address to following research questions: R.Q.1: What role is recognized to stakeholders in the S3?

R.Q.2: Which are the main opportunities and challenges of setting a collaborative governance in S3?

R.Q.3: Which facilitators are identified to overcome its critical aspects while exploiting its potentialities?

The intention of this review is also to capture the theoretical models recalled by the studies and the methodologies used when undertaking research studies on S3. To provide a suitable answer to the research questions, a protocol of work was formulated to specify the methods to select suitable articles (Kitchenham, 2004). A key-word search strategy was applied in all-text using as keywords “Smart Specialization” OR “Smart Specialisation” AND (governance OR helix OR stakeholder). Three databases were used to retrieve articles, which are Business Source Premier, Econlit, Education Research Complete. Using the mentioned key strategy 90 articles were found (March 2018), accepting only academic journals in English (1st eligible criteria). Then a further assessment was made to select only those papers dealing both with S3 strategy and involvement of different stakeholders in accordance to the flow chart here presented (Figure 2).

25

Figure 2. Selection of articles for the systematic review

Source: Own elaboration

From the application of the 2nd eligible criteria 36 articles were found as complying with the objectives of the review. The remaining articles were excluded since not considering as central topic S3 or not addressing in anyway the objectives of the research in relation to the topic of collaborative governance (C).

1.2.3. The role of stakeholders in S3 design and implementation

The systematic literature review has allowed to identify insights on the main opportunities and challenges emerging in a collaborative governance when developing S3, presenting some potential facilitators to overcome the critical aspects, while exploiting the role of such a multi-stakeholder prospective. In relation to the methodology used in the 36 selected articles, 14 of these were theoretical papers, while 17 included a case study as presented in Appendix 1. Among the case studies, 9 were based on desk research providing a descriptive analysis, while 8 revealed to be more structured, based on interviews and questionnaires. In addition, 2 articles included econometric modelling and 3 a multi-case study prospective. Theoretical frameworks were proposed by the selected studies, as relational resource approach (Magro et al., 2014), social network analysis (Vittoria & Lavadera, 2014), connectivity model (Virkkala et al., 2017) and Analytical Hierarchical Process (AHP) (Šipilova et al., 2017).

Figure 1. Selection of articles for the systematic review

All text- analysis Does it provide an answer to

R.Q.1,2,3?

R. Q.1, R.Q.2 and R.Q.3?

Articles from 1st eligible criteria (Academic Journal in English) From abstract and keywords

THE MAIN TOPIC IS

(A) S3 AND multi-stakeholder

(B) S3 OR multi-stakeholder (C) NOT: S3 OR multi-stakeholder Accepted YES NO Accepted (B) Rejected (C) Rejected

26

On the other hand, the TH model was recalled in 7 articles when considering the relationships between industry-government and academia, as in the case of Šipilova et al., 2017 and Camagni & Capello (2013). Morgan (2017) proposed a three-tier system divided in governmental, intermediate and operational level, while Fabbri (2016) suggests an institutionalization of the triple helix system. The QH was explicitly considered in 5 studies, others even if not recalling a quadruple helix, included in the network of relationships the civil society as Casaramona et al. (2015), McCann and Ortega-Argilés (2016); Kleibrink et al. (2016), confirming the need to consider in the policy development also the demand side (Karo & Kattel, 2015; Šipilova et al., 2017).

Further articles referred to both the TH and QH (n.5). In Addition, Carayannis and Rakhmatullin (2014) presented in their analysis the natural environment of the society where relationships take place as a fifth helix. This last approach stresses the socio-ecological perspective of the natural environment of society by considering the interactions between society and nature. As for the role of stakeholder, as reported in the Table 4, stakeholders were mainly identified as actors responsible for the development of the overall strategy in its different steps, starting from its design (Karo & Kattel, 2015), preparation of data and analysis (Marlow & Richardson, 2016), consultation (Kroll et al., 2016), evaluation (Aragon et al., 2014), monitoring (Kleibrink et al., 2016) and lastly in the implementation (Capello & Kroll, 2016). Stakeholders are recognized as key actors especially in the process of EDP (Polverari, 2017, Fabbri, 2016) in its decentralized approach (Foray, 2016).

Other studies underlined more their role as part of an innovation system as in the case of Magro et al. (2014) and as contributors for implementing innovation processes (Rudolf & Yusupova, 2015). In the same line, other studies include them in different innovation models and ecosystems (Camagni & Capello, 2013; Reimeris, 2016) or as part of emerging micro-systems of innovation (Foray, 2016). In other papers, stakeholders are presented as actors involved in processes of interactive learning (Camagni & Capello, 2013), capacity building (Estensoro & Larrea, 2016) and as knowledge providers (Todeva & Ketikidis, 2017). Others emphasized more their role in the regional growth and competitiveness (Konstantynova & Lehmann, 2017), especially for a sustainable development (Šipilova et al., 2017; Rinkinen et al., 2016) towards a social and economic transformation (Mieszkowski & Kardas, 2015).

27

Table 4. Role recognized to stakeholders in the S3

Responsible for the comprehensive S3 development Actors of innovation models

Responsible for the regional growth and development

Source: Own elaboration

1.2.4. Opportunities and challenges of collaborative governance

Instead, the opportunities identified in a collaborative governance, as reported in opposition to the challenges in Table 5 relate to the possibility of exploiting knowledge sharing potentialities, especially as an exchange of tacit knowledge through informal social interactions, coming from different knowledge basis starting from general to applied ones (Nunes & Lopes, 2015). The same relates by using different kinds of knowledge to define long term priorities, synergistic investments and collective actions (Clar & Sautter, 2014), also forcing the public sector and all other actors to understand in open reflection what they are good at (Polverari, 2017).

There is a large source of knowledge contribution when implementing innovation processes (Rudolf & Yusupova, 2015), and this knowledge-based development is also driven by the population for which a higher involvement is required (Šipilova et al., 2017). Other articles focused more on the possibility of taking advantage of occasions of interactive learning in the productive system (Muscio et al., 2015) being a dynamic process that can lead to potential policy improvements through the exchange of ideas and perspectives (Aragon et al., 2014), resulting from the proximity of stakeholders (Virkkala et al., 2017). Overall, the triple and quadruple helix approach are even encouraged by the EDP by giving rise to a more inclusive governance that breaks the silos between research, industry and policies (Peroulakis, 2017) and also limits the innate wisdom of government due the strong learning process of the whole system (Foray, 2016).

Further, selected smart specialization strategy can help overcome the limited degree of cooperation among regional stakeholders, leading to a strategic cooperation (Mieszkowski & Kardas, 2015). Lastly, an effective collaborative governance results to be determinant for the participation in international networks (Boden, 2017; Wostner, 2017).

Contrary, one of the major concerns emerging in developing a collaborative governance seems to be the persistence of old routines and mechanisms (Karo & Kattel, 2015) which give rise to difficulties in working on a new concept of strategy based on learning, negotiation and collaboration (Estensoro & Larrea, 2016). In particular, for Eastern Europe the adoption of

28

new governance practices meets hard institutional obstacles due to the traditional planning culture and centralist systems, which are also affected by the general inertia as low participation complying with existing rules and priorities (Reimeris, 2016).

The problem is that of overcoming the resistance of local partners and permissive approaches (Marlow & Richardson, 2016) still sceptical on stakeholder involvements (Capello & Kroll, 2016). This is the case, for example of SMEs that might ignore the role of universities as potential innovation partners, due to weak collaborative culture (Healy, 2016).

Another major issue it that of keeping the momentum and an active participation of the actor throughout all the process (Aragon et al., 2014), together with the presence of too many actors around the table, identified as a bottleneck (Polverari, 2017). The process is described also as being time consuming in terms of time and effort needed to set up structures and process that allow stakeholder to interact (Wostner, 2017).

An emerging risk is that of monopoly coming from dominating actors in the political and economic landscape (McCann & Ortega-Argilés 2016) due to egocentric views (Virkkala e al., 2017) of specific interest groups as powerful lobbies or major regional stakeholders (Mieszkowski & Kardas, 2015). A further challenge that needs to be addressed is that of building trust and long-term relationships (Wostner, 2017), especially in the case of SMEs (Nordberg, 2015). However, the same topic is viewed also as an opportunity led by the strategy itself encouraging trust building and long- term mutual commitment (Kleibrink et al., 2016) when using specific tools and instruments to forest and support trust (Boden, 2017).

Table 5. Opportunities and Challenges in the S3 collaborative governance

Opportunities Challenges

Knowledge sharing Interactive learning International cooperation Trust building

Old institutional routines Passive participation

Dominance of selected interests

Ensuring trust and long-term commitment Resistance towards collaborative culture Diversity of interests

Time consuming process Information asymmetries

Lack of professional intermediaries

Lack of unified methodologies and structures