CHAPTER 1

SIRENIA

1.1 GENERALITIES

Sirenia are an order of placental mammals, including two extant families, the Trichechidae (manatees) and the Dugongidae (the dugong), and their extinct relatives. The name Sirenia comes from the Sirens, sea deities of Greek mythology, who lived on an island called Sirenum scopuli. They are the only extant herbivorous aquatic mammals and the only herbivorous mammals ever to have become totally aquatic (Domning, 2002a).

They arose by the late Early Eocene, they spread widely and they were diversified into three families by the Middle Eocene. The earliest known sirenians come from the late Early Eocene of Jamaica (Savage et al., 1994; Domning, 2001b). The early sirenians were amphibious quadrupeds; fully aquatic sirenians, with short paddle-like rounded flippers, no hindlimbs and a horizontal tail fluke, appeared by the Late Eocene (Domning, 2002a).

From their origin, sirenians were herbivores and probably depended on seagrasses and other aquatic angiosperms for food (Domning, 1981; Clementz et al., 2006). This condition determined their tropical and subtropical distribution in fresh and coastal waters where these plants lived. The only exception seems to be represented by the Hydrodamalinae, which secondarily adapted to colder waters (see Domning, 1978). Sirenians are shallow divers, with more or less downturned snouts adapted to bottom-feeding, with large lungs and heavy skeletons to help them stay submerged, constituted by bones both swollen (pachyostotic) and dense (osteosclerotic), especially the ribs, which are often found as fossils (Domning, 2002a).

Sirenians are today only represented by four species (Fig. 1): one species of Dugongidae, Dugong dugon (Müller, 1776) Palmer, 1895, living in the Indian Ocean and southwestern Pacific Ocean; and three species of Trichechidae (manatees),

Trichechus inunguis (Natterer in von Pelzeln, 1883) Trouessart, 1905 in the Amazon

basin, T. manatus Linnaeus, 1758 in coastal waters and rivers from the southeastern United States to southern Brazil, and T. senegalensis Link, 1795 in coastal waters and rivers of western Africa (Domning, 2002a).

In addition to these four species, the Steller’s sea cow, Hydrodamalis gigas (Zimmermann, 1780) Palmer, 1895, became extinct in 1768 (Fig. 1). It was a large hydrodamaline dugongid, 9 m or more long, without teeth, that grazed on algae along the shores of the cold North Pacific Ocean (Domning, 1978).

Fig. 1: Living sirenians and the recently extant Steller’s sea cow.

1.2 PHYLOGENESIS AND RELATIVES

The monophyly of sirenians is well established. Sirenians are united by possession of the following synapomorphies (Domning, 1994):

1- External nares retracted and enlarged, reaching to or beyond the level of the anterior margin of the orbit.

2- Premaxilla contacts frontal.

3- Sagittal crest absent, except in the oldest known sirenian, Pezosiren portelli, recently described by Domning (2001b).

4- Five premolars, or secondarily reduced from this condition by loss of anterior premolars (for a criticism see Bizzotto, 2005).

5- Mastoid inflated and exposed through occipital fenestra. 6- Ectotympanic inflated and drop-like.

The closest living relatives of Sirenia are Proboscidea (elephants).

Sirenia are included with Proboscidea and the extinct Desmostylia in the Tethytheria, a taxon of herbivorous mammals that appears to have evolved from primitive hoofed mammals (condylarths) in the Old World along the shores of the ancient Tethys Sea (as the name indicates) (Domning, 2002a).

The phylogenetic relations among the tethytheres are unclear. Domning et al. (1986) proposed that the proboscideans plus desmostylians were the sister group of sirenians, but Fischer and Tassy (1993) placed sirenians as the sister group to proboscideans (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: A) Tethytheria clade following Domning et al. (1986); B) Tethytheria clade following Fisher and Tassy (1993).

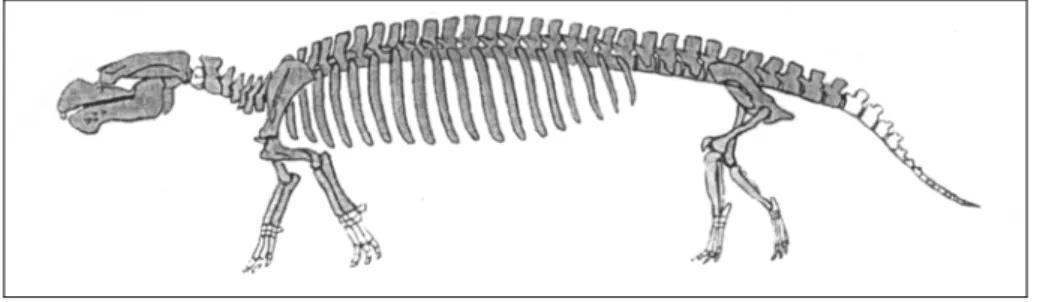

Desmostylia (Fig. 3) is an extinct order of herbivorous amphibious quadrupedal mammals, represented by two families, seven genera (Ashoroa, Behemotops,

Cornwallius, Desmostylus, Kronokotherium, Paleoparadoxia, Vanderhoofius) and ten

species, with their habitat in the North Pacific Ocean (Japan, North America and Kamchatka) from the Lower Oligocene to the Upper Miocene (Inuzuka et al., 1995). Desmostylia inhabited nearshore-marine areas (intertidal sandy beaches). Each genus is distinguished by a set of tooth characters. They were herbivorous and some derived species show an adaptation for an abrasive diet. All the Desmostylia share a common and distinctive body form: strongly arched spine, steeply inclined pelvis, limbs more or less under the body and digitigrade foot posture with front toes pointing anterolateral and hind toes pointing forward (Domning, 2002b).

Fig. 3: Skeleton of Paleoparadoxia tabatai, a Miocene desmostylian, in terrestrial pose. Total length is about 2.2 m (modified from Domning, 2002b)

Proboscidea (Fig. 4) is an order of herbivorous terrestrial mammals represented by three extant species only, which are the biggest terrestrial mammals today: the bush African elephant (Loxodonta africana), the forest African elephant (Loxodonta

cyclotis), and the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) with three subspecies (Shoshani &

Tassy, 2005). However, proboscideans have an extensive fossil record with about 175 species and subspecies recorded from Africa, Eurasia and America (Shoshani & Tassy, 1996; 2005).

The Proboscidea are characterized by a number of features: reduced jugal and orbit that opens in the maxilla; enlarged second upper incisors that become tusks in most later forms; lower canines and first premolars absent; broad molar teeth with thickened cusps and ridges; and adaptations of the limbs for weight-supporting (Shoshani & Tassy, 1996; 2005).

The earliest known proboscidean is the small species (the size of a fox) Phosphatherium

escuilliei from the Lower Eocene of Morocco (Gheerbrant et al., 2005). Very likely, the

earliest species were amphibious; in fact the Eocene genera Moeritherium from Egypt, Mali, Libya and Algeria, and Numidotherium from Algeria show amphibious characters (Tassy, 2004). Proboscidean evolution was characterized by several radiations and extinctions, dwarfing and gigantism, cool adaptations, variations in tusk morphology and size (Shoshani & Tassy, 1996; 2005).

Fig. 4: Cladogram of Elephantimorpha (Proboscidea) with stylohyoidea and silhouettes of representative taxa (modified from Shoshani & Tassy, 2005).

1.3 DISTRIBUTION AND CLASSIFICATION

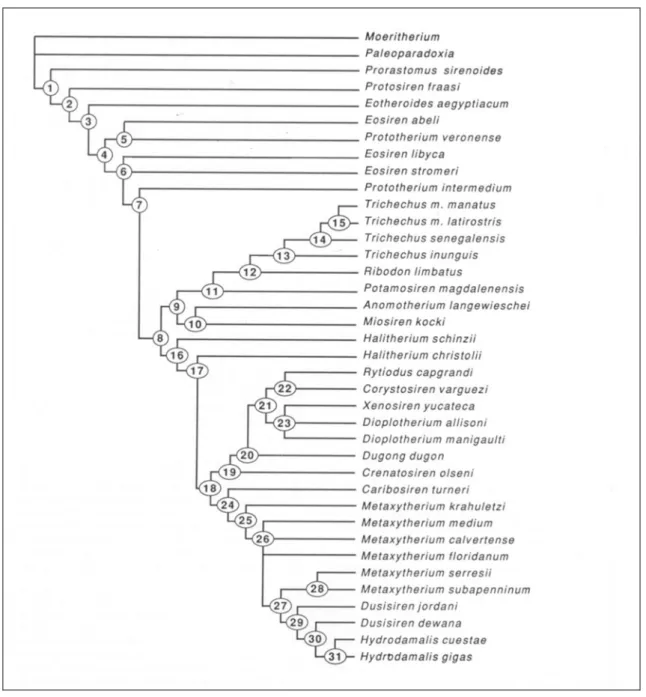

Domning, in his phylogenetic analysis of the Sirenia (1994) (Fig. 5), recognized four families: Prorastomidae, Protosirenidae, Trichechidae and Dugongidae.

Fig. 5: Nelson consensus tree of sirenian taxa and outgroups, generated by Hennig86 (from Domning, 1994).

1.3.1 PRORASTOMIDAE

“Prorastomidae” (Fig. 6) is a paraphyletic family that includes the oldest and most primitive sirenians, Pezosiren portelli Domning, 2001 and Prorastomus sirenoides Owen, 1855, known from the late Early Eocene and the early Middle Eocene of Jamaica (Savage et al., 1994; Domning, 2001b). Two atlases from the Upper Eocene of Florida are also referred to the “Prorastomidae” (Savage et al., 1994).

The “Prorastomidae” were pig-sized quadrupeds fully capable of locomotion on land, with four well-developed legs, a multivertebral sacrum, and a strong sacroiliac articulation that could support the weight of the body out of water; but they presented aquatic adaptations too and probably they spent most of their time in the water, swimming by spinal extension with simultaneous pelvic paddling similar to contemporary primitive cetaceans (Domning, 2001b).

Fig. 6: Reconstructed composite skeleton of Pezosiren portelli. Length about 2.1 m (modified from Domning, 2001b).

1.3.2 PROTOSIRENIDAE

Protosirenidae (Fig. 7) is a family that includes the following Eocene species:

Protosiren fraasi Abel, 1907 (previously referred to Eotherium aegyptiacum (Owen,

1875) Trouessart, 1905 by Andrew, 1906) from the Middle Eocene of Egypt (Gingerich et al., 1994); P. smithae Domning and Gingerich, 1994 from the late Middle Eocene of Egypt (Domning & Gingerich, 1994); P. sattaensis Gingerich, Arif, Bhatti, Raza and Raza, 1995 from the Middle Eocene of Pakistan (Gingerich et al., 1995); P. eothene Zalmout, Haq and Gingerich, 2003 from the early Middle Eocene of Pakistan (Zalmout et al., 2003); Protosiren sp. from the Middle Eocene of Western India (Bajpai et al., 2006); and probably ?Protosiren minima (Desmarest, 1822) Hooijer, 1952 from the Middle Eocene of Western France, considered by Domning (1996) as a species of uncertain status and affinities; and an unpublished genus and species described by Heal (1973) in his unpublished PhD Thesis (pers. obs.).

The Protosirenidae appear to be divergently specialized from other early sirenians, and less fully aquatic than contemporary primitive dugongids. Their ribs were less swollen, and had a unique form of articulation with the vertebrae that led Sickenberg (1934: 88) to conclude that their respiratory mechanics were distinctive. Moreover, they had much less reduced pelvis and hindlimbs than the contemporary primitive dugongids, and their anterior thoracic neural spines were high and probably served to support the head by way of a nuchal ligament. However, the legs of P. smithae were very short relative to its body, and it seems questionable whether this species could have lifted its body off the ground; it may have merely slid or rested on its belly when out of the water, in a manner analogous to that of modern pinnipeds (Domning & Gingerich, 1994).

Protosirenidae were characterized by a broadened masticating surface with the retention of large incisors and canines along the margins that may indicate a different style of feeding like that of no other sirenian, a less selective underwater “grazing” (Domning & Gingerich, 1994).

Fig. 7: Reconstruction of type skull of Protosiren fraasi in lateral view. Scale bar: 5 cm (modified from Gingerich et al., 1994).

1.3.3 TRICHECHIDAE

The family Trichechidae (Fig. 8) has a record from the Late Oligocene. It is characterized by: rostrum small relative to cranium; processus retroversus of squamosal absent and external auditory meatus of squamosal very broad and shallow, wider anteroposteriorly than high.

The family includes two subfamilies, the Miosireninae and the Trichechinae (Domning, 1994).

The Miosireninae are a northern European taxon composed of two genera:

Dollo, 1889 from the Lower Miocene of Belgium and probably England (Domning, 1994).

While the Trichechinae appear to have evolved in the Southern Atlantic, in fact they include, besides the three living species of Trichechus Linnaeus, 1758, two fossil species: Potamosiren magdalenensis Reinhart, 1951 from the Middle Miocene of Colombia (including Metaxytherium ortegense Kellogg, 1966) and Ribodon limbatus Ameghino, 1883 from the Upper Miocene or Lower Pliocene of Argentina. The more derived Trichechinae (Ribodon and Trichechus) are characterized by supernumerary cheek teeth interpreted as an adaptation to an abrasive diet consisting of a wide variety of freshwater aquatic plants (especially true grasses) together with marine seagrasses (Domning, 1982a; 1994).

Fig. 8: Skull of Trichechus senegalensis (Trichechidae) in lateral view. Scale bar: 5 cm.

1.3.4 DUGONGIDAE

The “Dugongidae” (Fig. 9) is a paraphyletic family (Domning, 1994), divided into three subfamilies: “Halitheriinae”, Dugonginae and Hydrodamalinae.

Dugongidae are characterized by: posttympanic process of squamosal present; external auditory meatus of squamosal short; squamosal extended to temporal crest; processus retroversus of squamosal present; alisphenoid canal absent; pterygoid fossa present; mandibular symphysis broad; mandibular dental capsule exposed posteroventrally (Domning, 1994).

Fig. 9: Skull of Dugong dugon (Dugongidae) in laterl view. Scale bar: 5 cm.

The early dugongids are Middle to Late Eocene in age and their record shows a rapid dispersion on both margins of the former Tethys Sea: the South-Tethyan dugongids are represented by the genera Eotheroides Palmer, 1899 and Eosiren Andrews, 1902 from Egypt and Western India. The North-Tethyan ones are represented by the Italian and Spanish genus Prototherium de Zigno, 1887, by the Hungarian and Rumanian genera

Anisosiren Kordos, 1979, Paralitherium Kordos, 1977, Sirenavus Kretzoi, 1941, ?Halitherium sp. and by the French species Halitherium taulannense Sagne, 2001

(Sagne 2001; Bajpai et al., 2006).

Eotheroides, Eosiren, Prototherium and Halitherium are assigned to the

“Halitheriinae”; while Anisosiren, Paralitherium, and Sirenavus are considered Dugongidae incertae sedis (Domning, 1996).

“Halitheriinae” is a paraphyletic subfamily composed of the Eocene dugongids listed above, the early Oligocene species Eosiren imenti Domning, Gingerich, Simons and Ankel-Simons, 1994, the Oligocene species of the genus Halitherium Kaup, 1838 and

Caribosiren turneri Reinhart, 1959; and the cosmopolitan genus Metaxytherium de

Christol, 1840.

The oldest species of the genus Halitherium is considered Halitherium taulannense Sagne, 2001, collected from the Upper Eocene (Priabonian) of the Alps of Haute-Provence (France) (Sagne, 2001). The other species of Halitherium are H. schinzii (Kaup, 1838) Kaup, 1855 from the Lower Oligocene of Germany, Belgium and France and H. christolii Fitzinger, 1842 from the Upper Oligocene of Austria. There are also two Late Oligocene species doubtfully referred to Halitherium: H. alleni Simpson, 1932 and ?H. antillense Matthew, 1916, respectively from South Carolina and Puerto Rico (Domning, 1996).

Caribosiren turneri comes from the Middle or Upper Oligocene of Puerto Rico and it is

represented only by a single well-preserved but incomplete skull for which several characters cannot be scored, so this taxon is one of the least stable. Domning (1994, 1996) considered it as an halitheriine.

All the other halitheriines belong to the best-known genus, Metaxytherium, which has a wide geographical and biostratigraphical distribution. Metaxytherium remains have been collected in several Miocene localities of the Mediterranean and Paratethyan region (Domning & Thomas, 1987; Domning & Pervesler, 2001; Bianucci et al., 2003; Carone & Domning, 2007), Northeastern Atlantic (Cottreau, 1928; Estevens, 2003a,b), Southeastern Pacific (Muizon & Domning, 1985), Northeastern Pacific (Aranda-Manteca et al., 1994) and Western Atlantic and Caribbean region (Domning, 1988; Toledo & Domning, 1991; Aranda-Manteca et al., 1994). At the end of the Miocene

Metaxytherium became extinct in the Americas, while it survived until the Middle

Pliocene in the Mediterranean basin and probably along the Atlantic coast of Morocco (Domning & Thomas, 1987; Sendra et al. 1998, 1999).

The oldest securely dated Metaxytherium remains, apart from one unpublished Late Oligocene occurrence in the USA (Domning, pers. comm.), are those referred to M.

krahuletzi from the Burdigalian of the Old World (Domning & Pervesler, 2001).

In the Old World the genus Metaxytherium was represented by four species: M.

krahuletzi Depéret, 1895 (Burdigalian); M. petersi Abel, 1904 (Langhian to Middle

Serravallian: Badenian) (Domning, pers. comm.); M. medium (Desmarest, 1822) Hooijer, 1952 (Langhian to Tortonian); M. serresii (Gervais, 1847) Depéret, 1895 (uppermost Tortonian to early Zanclean) and M. subapenninum (Bruno, 1839) Fondi and Pacini, 1974 (Zanclean to Piacenzian) (Domning & Thomas, 1987; Domning & Pervesler, 2001; Bianucci et al., in press).

Most of these Old World Metaxytherium species seem to represent a single lineage characterized by very slight morphological change from M. krahuletzi to M. medium and by dwarfing in M. serresii followed by a notable increase in body size in M.

subapenninum (Domning & Thomas, 1987; Bianucci et al., in press). The exception is M. petersi, which apparently evolved in isolation in the Carpathian Basin during the

Middle Miocene as a short-lived and localized offshoot of the M. krahuletzi-M. medium stem (Domning, pers. comm.)

Meanwhile, in the Caribbean-western Atlantic region there lived the Early Miocene species M. crataegense (Simpson, 1932) Aranda-Manteca, Domning and Barnes, 1994 (= M. calvertense Kellogg, 1966) that apparently gave rise, with little change, to the

Middle Miocene species M. floridanum Hay, 1922 and that also entered the eastern Pacific through the Central American Seaway (Muizon & Domning, 1985; Aranda-Manteca et al., 1994). The southeastern Pacific record of M. crataegense consists of specimens from the Lower or Middle Miocene Montera Formation of Peru (Muizon & Domning, 1985); while in the northeastern Pacific M. crataegense gave rise to M.

arctodites Aranda-Manteca, Domning and Barnes, 1994. M. arctodites was found in

Middle Miocene deposits of Baja California and California, and is viewed as the sister group of the Hydrodamalinae (Aranda-Manteca et al., 1994).

The Dugonginae are characterized by: nasal incisure extending posterior to the supraorbital process; jugal having overhanging orbital rim; tusks primitively moderate in size to very large; supraorbital process of frontal turned markedly downward, with dorsal surface inclined strongly ventrolaterad and posterolateral corner projecting posteriorly; preorbital process of jugal thick and robust (Domning, 1994, 1997).

The most primitive known dugongine is Crenatosiren olseni (Reinhart, 1976) Domning, 1991 from the Upper Oligocene to lowermost Miocene of Florida, South Carolina and North Carolina. The Dugonginae probably arose in the Caribbean-western Atlantic region during the Early Oligocene from Halitheriinae and underwent an adaptive radiation and pantropical dispersal in the Late Oligocene and Early Miocene (Domning, 1997).

In western India, fossil Dugonginae are represented by the Late Oligocene Bharatisiren

indica Bajpai, Thewissen, Kapur, Tiwari and Sahni, 2006 and the Miocene B. kachchhensis Bajpai and Domning, 1997. Fossil records from the Miocene of Java,

western India, Sri Lanka and Japan exist too but they may represent either dugongines or halitheriines (Domning & Furusawa, 1995; Domning, 1996).

The living dugong Dugong dugon (Müller, 1776) Palmer, 1895, present today in the Indian Ocean and in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, has no fossil record other than some fragments of possible Pleistocene age from Australia and Papua New Guinea (Domning & Furusawa, 1995). However, specimens from Florida, representing the sister group of Dugong dugon or even a congeneric species, indicate a possible Caribbean-western Atlantic origin for the genus (Domning & Furusawa, 1995; Domning, pers. comm.).

In the Early and Middle Miocene Dugonginae colonized the northeastern Pacific Ocean too, through the Central American Seaway (Domning, 1978). Rare and fragmentary remains from California and Baja California Sur were assigned to Dioplotherium

allisoni (Kilmer, 1965) Domning, 1978, a dugongine also known by a good skull and

other specimens from the Atlantic coast of Brazil (Toledo & Domning, 1991).

Dioplotherium, like most other dugongines, had a strongly downturned snout and very

large, blade-like tusks. It was evidently a bottom-feeder specializing on the hard-to-excavate rhizomes of the largest seagrass species, in addition to eating the leaves of seagrasses in general. Late Cenozoic cooling and marine regression in the eastern North Pacific favoured kelps at the expense of most of the seagrasses, and as a result

Dioplotherium became extinct in the Pacific without issue at the end of the Middle

Miocene (Domning, 1978).

Some fossils possibly referable to the Dugonginae come from the southeastern Pacific too, but they consist only of a rib from the Early Pliocene Pisco Formation of Peru (Muizon & Domning, 1985) and a molar from the Upper Miocene of Chile (Bianucci et al. 2006).

The dugongines’ record in the Caribbean-western Atlantic region includes, besides the primitive Crenatosiren olseni (Domning, 1991), Dioplotherium manigaulti Cope, 1883 (Domning, 1989a), Corystosiren varguezi Domning, 1990 and Xenosiren yucateca Domning, 1989.

In the Mediterranean-Paratethys region, there is instead only the genus Rytiodus Lartet, 1866 from the Lower Miocene of France and Libya (Heal, 1973; Domning, 1996) and

“Halitherium” bellunense Zigno, 1875 from the Lower Miocene of Italy. The latter is

considered by Domning (1996) as Dugonginae incertae sedis.

Some of the oldest Dugonginae have very large tusks, suggesting that their characteristic adaptive zone originally involved the exploitation of seagrasses with large, tough, deeply buried rhizomes. Fossil specimens of Dugonginae are rare and that may merely be an artifact of sampling or may reflect an actual rarity of the animals during life, at least in Europe and North America where fossils of other dugongid subfamilies are more numerous. Such actual rarity could be attributed to their role as eaters of large rhizomes of “climax” species of seagrasses, the relatively low productivity of which could not support large populations of herbivores (Bajpai & Domning, 1997; Domning, 2001a).

Hydrodamalinae is a subfamily restricted to the North Pacific; it includes the genera

Dusisiren Domning, 1978 and Hydrodamalis Retzius, 1794. This subfamily probably

derived from a single colonization of the North Pacific by Early Miocene halitheriines from the Caribbean through the Central American Seaway. Aranda-Manteca et al.

(1994) considered the halitheriine Metaxytherium arctodites (Middle Miocene, California) as the sister group of the Hydrodamalinae.

The Hydrodamalinae are characterized by: dorsolateral border of exoccipital greatly thickened, forming rugose, overhanging flange; processus retroversus of squamosal present, but not inflected; preorbital process of jugal contacting premaxilla; lacrimal vestigial or absent; horizontal ramus of mandible slender with ventral border moderately concave; first upper incisors vestigial or absent. They are also characterized by a tendency toward decrease of rostral deflection; increase in body size; and reduction and eventual complete loss of dentition (Domning, 1978, 1994).

The Hydrodamalinae increasingly adapted to feeding on large plants growing well up from the bottom, especially kelps. Late Cenozoic cooling and marine regression favoured the kelps at the expense of most of the seagrasses; as a result the Northern Pacific Halitheriinae and Dugonginae became extinct without issue at the end of the Middle Miocene and the Hydrodamalinae flourished (with or without phyletic branching), adapting to a cooler climate, spreading to the western Pacific by 12 Ma and evolving into Hydrodamalis by about 8 Ma. This highly specialized genus continued to inhabit the Pacific coasts from Japan to Mexico until its probable progressive elimination by human predation during the Late Pleistocene and Recent. H. gigas (Zimmermann, 1780) Palmer, 1895 was finally exterminated ca. 1768 (Domning, 1978).