FARMERS AND SHORT CHAIN

Legal profiles and socio-economic dynamics

edited by Francesca Giarè and Sabrina Giuca

collana SISTEMA DELLA CONOSCENZA. Quaderni

Farmers and short chain

The Knowledge System in Agriculture division develops and conducts research and pro-vides support to central and regional governments in three main areas:

The research system in its main components and in relation to institutional levels that promote it (European, national, regional);

Regional development services, particularly for measures provided for in European po-licies;

Social and cultural aspects of agriculture as factors for developing new ways of produc-tion and service to the community.

Research and consulting initiatives follow a holistic and relational approach that em-braces all the classic components of the knowledge system (research, assistance and consulting, training, entrepreneurial and territorial fabric) and includes innovation as an across-the-board objective for the improvement of the agricultural and rural system.

inea

FARMERS AND SHORT CHAIN

Legal profiles and socio-economic dynamics

Edited by Francesca Giarè and Sabrina Giuca

Minutes of study seminar organised by INEA in Rome, on 30 May 2012.

The seminar and minutes were part of the “Promotion of rural culture” project funded by MIPAAF (Decree n. 0029277 of 27/12/2010) overseen by Francesca Giarè.

Editing secretary: Roberta Capretti Publishing coordinator: Benedetto Venuto

Introduction 5 Francesca Giarè, INEA

Legal profiles and socio-economic dynamics

Understanding the short chain 11 Sabrina Giuca, INEA

From the land to the territory: the role of the farmer in the short chain 31 Irene Canfora, University of Bari

The economic innovation of the short chain 45 Giovanni Belletti and Andrea Marescotti, University of Florence

The environmental aspects of the short chain:

the results of a direct survey of “farmers’ markets” in Italy 63 Davide Marino and Luigi Mastronardi, University of Molise

Social innovation of the short chain 87 Adanella Rossi, University of Pisa

experiences

The experience of women agricultural entrepreneurs of the CIA:

“Association of Women in the Field” 103 Sofia Trentini, CIA

The “Women in the Field” of Parma 107 Elvira Pallone, CIA

Coldiretti initiatives in the field of short chain 111 Lorenzo Bazzana, Coldiretti

The short chain path in organic farming, for food sovereignty 117 Andrea Ferrante and Annalisa Gallucci, AIAB

The “Sportello Mense Bio” (Organic Canteen Help Desk)

in Emilia-Romagna 123 Daniele Ara, Pro.B.E.R

The consumer as “co-producer” 129 Anselme Bakudila, Slow Food

Reducing intermediaries: the “Zolle” case in Rome 137 Rossella Guadagno, CURSA

The experience of consumers’ co-ops with “Purchasing Groups” 143 Alessandro Mostaccio, Piedmont Consumers' Movement

For some time now, reflecting on the evolution of agriculture and rural en-vironment, it has been difficult and often not very useful to speak of a single agri-culture. The forms our agriculture takes, in fact, are so many and varied that they cannot easily be classified, economically or from the point of view of social and cultural changes.

It is, however, difficult to articulate a language and thought adequate to the differences that can be observed in Italy, without the risk of aesthetic, cultural and geographical classifications.

The crisis in conventional agriculture, which fits into the overall crisis con-text of the dominant economic model, has had and has an important role in the emergence of "special methods" of farming that characterise some segments of our system, halfway between the preservation of local traditions and the innovative drive of new generations of farmers and consumers.

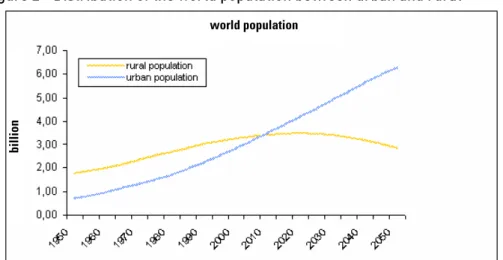

In this context, the distinction between agriculture as a place of food pro-duction and the city as a place of food consumption now appears simplistic and reductive. The same contrast between urban and rural no longer describes the situation clearly, because our territory mostly appears as a continuum of urban settlements and green spaces, sometimes cultivated, sometimes abandoned and scarred, sometimes protected and returned to the community for purposes other than agricultural.

Agriculture also produces other types of goods (environmental, social, edu-cational, relational, etc.) that contribute to rebuilding a strong relationship between producer and consumer or user of the environment, including agriculture. This relationship has many dimensions, ranging from the environmental to the social, from the economic to the cultural, to arrive at a political dimension that wiews producers and citizen/consumers as actors who are aware of the development of the territory and the community.

In particular, we are witnessing a relocation of a part of agriculture in rural areas, with the aim of increasing self-sufficiency and diversifying production, to respond more effectively to the emerging demand for a wider range of seasonal 1 INEA Researcher

products. This relocation relies on old and new forms of product marketing, called short chains, that reduce steps and intermediaries to create a new, direct and trust-based relationship between producers and consumers.

The short chain, however, is internally diverse in goals and methods, for pro-moters and organisers of initiatives, for economic, social and environmental impact. To address the issue in all its complexity, INEA, within the "Promotion of rural culture”2 project, created a seminar on “Farmers and short chain. Legal aspects and

socio-economic dynamics”, which involved experts and representatives of the ope-rational world. The notebook contains papers presented at the workshop, integrated and enriched by the authors to make the content more usable, and some other ex-periences that emerged in the course of the day.

In the first part of the work - Legal aspects and socio-economic dynamics - Sabrina Giuca introduces the short chain, presenting its features, peculiarities and critical points and retracing the main stages of its development. The chapter also questions traditional and innovative aspects of this particular form of supply chain, and presents interesting reflections on Common Agricultural Policy measures for its development. Giuca also presents short chain experiences to give a better under-standing of the wealth this phenomenon assumes nationally.

Irene Canfora deals with the role of the farmer in the short chain from the legal standpoint and within the context of Italian and European Union legislation. The chapter also highlights the limits of exploiting regional products through designated origin labels and emphasises the privileged role of the farmer in short chain promotional legislation.

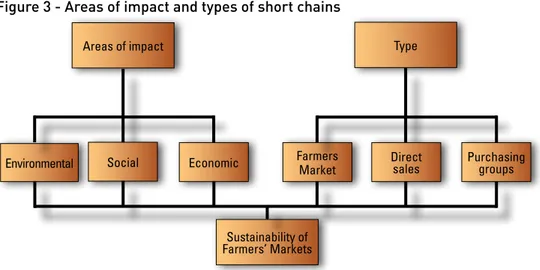

This first part of the work concludes with three contributions that focus on the short chain as an innovative phenomenon in economic, environmental and social terms.

Giovanni Belletti and Andrea Marescotti offer an interesting reflection on the economic innovation of the short chain, beginning with an analysis of three different levels: the structure of marketing channels, methods of organising trade relations and the organisational and production methods of farm management.

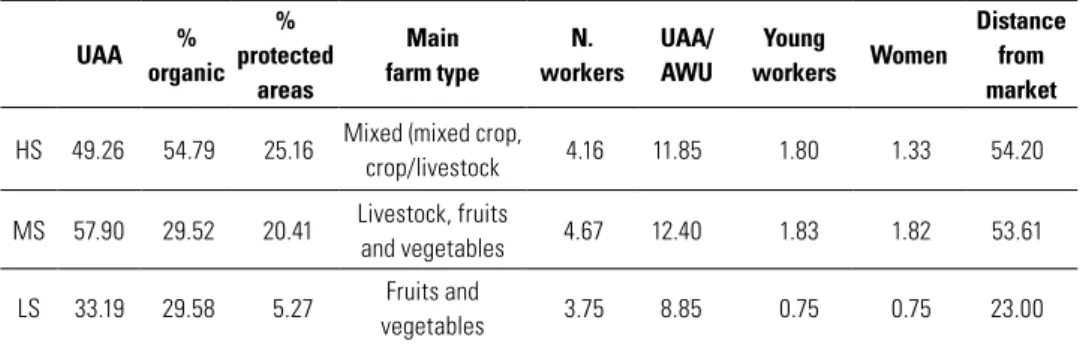

Davide Marino and Luigi Mastronardi, in outlining the environmental aspects of short chain, present the results of a direct survey on "farmers' markets" in Italy, addressing both their impact on the environment and consumers’ perception of the environmental value of these forms of marketing.

The social innovation of the short chain, understood as a collective response 2 The “Promotion of rural culture” project was launched by INEA in 2006 with funding from MIPAAF and the goal of encouraging awareness of the agricultural and rural world, and to examine relevant aspects of social and cultural change in recent years. This work was part of the third year of the project (MIPAAF Decree n. 0029277 of 27/12/2010).

of these processes of change, the author shows, is building new cognitive and nor-mative patterns.

The second part of the notebook contains some valuable experiences from parties involved in the short chain in various ways, from professional organisations that are spending heavily on this issue, like Coldiretti and the CIA (Italian Farmers’ Federation), producers’ associations such as AIAB and Prober, which introduce shortening the supply chain as well as environmental sustainability and organic. Other experiences highlight the role of consumers and new intermediaries in launching short chain initiatives.

The work as a whole provides a broad overview of analytical perspectives on the issue, and Italian experiences, and presents the first step towards a systematic reflection on the short chain, which we hope will encourage various parties to exa-mine the issue from different perspectives.

Understanding the short chain

Sabrina Giuca1

Introduction

The transformation of production organisation, “from artisan and local models to industrial and delocalised models” (Belliggiano, 2009), has resulted in a steady increase in geographical and cultural distances between consumers and producers, as well as high environmental impact, due to intensive preparation, processing and packaging techniques and long-distance transport.

Today, with “globalisation”, understood as the mixing and enrichment of

cultures2, international products arrive on our tables and Italian products arrive

on tables around the world. But in industrialised countries, in the face of greater availability of food (food security), the standardisation of products and the loss of richness and variety, sensitivity has grown in terms of food safety, or a healthy life guaranteed by safe food. This sensitivity, moreover, is heightened by food scandals and public health emergencies between the old and the new millennia that have generated international agreements on the regulation of food and agri-food prod-ucts and broad legislation by the European Union, aimed especially at improving health and hygiene standards throughout the food chain from “from farm to fork”.

However, both food risk and trends and sensitivity to common issues closely related to food and its preparation - pollution of the ecosystem, loss of biodiversity, conditions of animal husbandry and genetic manipulation - have changed people’s relationship with food. Cultural more than economic phenomena, with a common vision about food and the relationship between food, environment and territory, have generated a high level of innovation in the organisation of consumption and purchasing, and the organisation of production towards quality food and marketing 1 Researcher at INEA (National Institute of Agricultural Economics).

2 Globalisation, despite the generalised use of the term, can assume different accepted meanings, depending on context: “an economic meaning”, referring to the internationalisation of produc-tion processes and distribuproduc-tion of merchandise; “a commercial meaning”, referring to trade rules established by international agreements; “a cultural process”, referring to the process which, through widespread standardised patterns of behaviour and consumption, leads to the loss of lo-cal identities; “an ideology”, referring to the triumph of liberalisation and the exaltation of efficient market mechanisms; “a form of imperialism”, characterised by an unfair transfer of wealth from South to North worldwide (Lang, 1996).

through short chain forms that can reduce the number of steps between producer and consumer and enhance interpersonal relationships.

By experimenting with new forms of exchange, meeting and cooperation - to which scholars, the media and policy makers have paid increasing attention in recent years - producers recover their income margin up the supply chain, or otherwise are frustrated by the dominant model of marketing in the food indus-try, characterised by the presence of intermediaries and the prevalence of large-scale retail (GDO); buyers, however, find the link between quality products and the territory and recover the relationship of trust with those who sell “face-to-face”. They obtain economic advantage, because reducing the number of intermediaries reduces the final price. At the same time, farmers and consumers contribute to mitigating the impact on the environment (reduction of energy consumption and pollution linked to transport and refrigeration, little or no packaging, etc.), “lend-ing a hand” to the local economy and promot“lend-ing the territory.

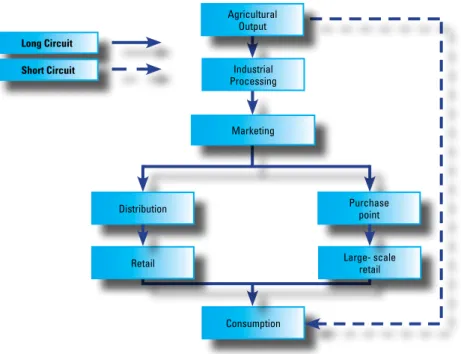

The short chain concept

The French agronomist Malassis (1973) described the supply chain as the set of agents (firms and governments) and operations (production, distribution, financing) that contribute to the formation and transfer of the product (or group of products) to the final stage of use, as well as all connected flows. If reducing the steps in the supply chain (long circuit) shortens the product’s route through the agri-food system, we can speak generally of the short chain (short circuit) until, in the absence of intermediaries, there is direct access to the final market, in which case the short chain coincides with so-called “direct sales”, in which the consum-er or othconsum-er actors, such as restaurants or retail outlets, intconsum-eract directly with the farm without other steps (Figure 1). In this circuit, long or short, according to the Malassis concept, the central elements for analysis are, on the one hand, the iden-tification of products, routes, agents and operations and, on the other, regulating mechanisms: behaviour of agents, functioning of markets, price formation.

This great diversity of forms, motives and practices that shortening the chain can take may be defined as “alternative food networks” (AFN) (Holloway and Kneafsey, 2004). In most cases, these alternative networks arise in response to dissatisfaction with an industrial-type distribution system, which from many points of view has disappointed the expectations of consumers and producers (Sonnino and Marsden, 2006; Raffaelli et al., 2009). In particular, in the face of industry and market conditioning and the concomitant difficulty of gaining access to

conven-tional commercial channels due to the lack of regularity of production, farmers and small- and medium-sized enterprises have to pay for the progressive loss of decision-making power, with an inevitable decline in profit margins.

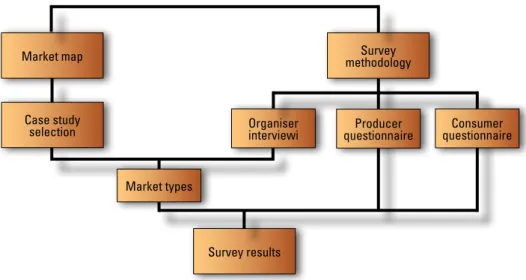

Figure 1 - The supply chain

The approach in the literature to describe AFNs is mainly geographical or sociological, partly because of the inherently contextual nature of the phenomenon and the lack of quantitative data, with case studies and exploratory surveys of

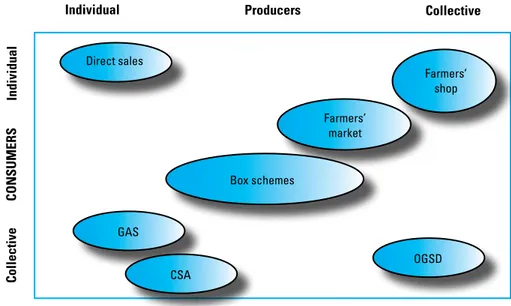

lo-cal situations (Venn et al., 2006). Apart from e-commerce and catalogue sales3,

the most common forms of short chain are local, where one can choose, evaluate and buy local products - fresh, ripe and in season - that retain their organoleptic and nutritional properties, at lower costs than with traditional channels (Knickel and Renting, 2000, Taylor et al., 2005; Seyfang, 2008). These range from direct sales on farms to farmers’ markets; from weekly subscription deliveries to house-holds (“box schemes”) to joint purchasing groups (JPG) and organised distribution groups (GODO); from harvesting products directly in the fields (“pick-your-own”) 3 In Italy, neither of these direct sales methods for agri-food products is widespread, and only

pack-ageable and non-perishable products with constant quality and low sales frequency, like olive oil, wine and jams, are suitable for this sales channel (IRUR, 2011).

Consumption

Purchase point Distribution

Retail Large- scale retail Agricultural Output Marketing Industrial Processing Long Circuit Short Circuit

to raw milk dispensers; from the supply to the HoReCa circuit (hotels, restaurants, caterers) to consumer cooperatives to new ways of cooperation between

produc-ers and consumproduc-ers (CSA)4.

The term “short chain” is often associated with a number of adjectives about product requisites - seasonality, freshness, authenticity - as well as more or less complex concepts such as territoriality, information on the ori-gin of products, food safety and “km 0”. This last expression, indicating the kilometres that food travels from where it is produced to where it is con-sumed, aims to express the extent of environmental impact from transport (Franco, 2007), which is not always proportional to the short chain: with a simple “click of the mouse” on the producer’s website, for example, you can directly purchase agricultural products from the South to the North of Italy or send a wine from one of Italy’s many wineries to the top floor of a skyscraper in New York (Giuca, 2012). Products reach the consumer, “imbedded” with information on the origin and method of production (Renting et al., 2003), thanks to the establishment of trust with the producer, who by talking and communicating via the web can learn more about consumers and their needs, and improve service.

In general, in AFNs, the concept of food quality, although complex and

multidimensional5, becomes essential; the shortening of the distance

be-tween production and consumption, to direct contact (and direct communica-tion) between producer and consumer, thanks to the information acquired, personal knowledge and the stability of the same people and the same places of purchase, allows the consumer to make more informed choices about, for example, the use of environment-friendly farming practices or the adoption of a traditional recipe in food preparation.

4 CSA (English acronym for “Community Supported Agriculture”), a short chain form begun in Swit-zerland and Japan in the 1960s that later spread to the USA, means a direct commercial partner-ship between one or more farmers and a network community of supporters/consumers. The latter help to guarantee part of the operating budget in a determined agricultural activity (often organic), by subscribing to one or more “shares” of the season’s harvest, thus assuming the costs and risks inherent in the agricultural activity along with the farmer (Raffaelli et al., 2004).

5 The concept of food quality merges strictly subjective criteria that preclude an unequivocal and universally acceptable definition, and a definition is not found in legislative texts (Germanò, 2009). Quality, indeed, tends to satisfy hedonistic needs, by nature plural, negotiable, distinct and adjunc-tive with regard to hygienic safety (requisites of a hygiene-health nature that agricultural products circulating in the European Union must possess), which by its nature is, rather, uniform and non-negotiable (AIDA, 2009).

Tradition or innovation?

The short chain is not just a fad, at a time when the economic crisis has weakened the purchasing power of households and the consumer’s attention has increasingly shifted to food safety. If, on the one hand, this form of marketing be-comes a tool to support food consumption, as well as a response to the growing demand for natural, high-quality food products, on the other hand it allows the farmer, usually the weak link in the agri-food chain, to regain his active role in the food “system”, by giving him the right price for his products (Whatmore et al., 2003) and the guarantee of market opportunities.

The short chain is not a novelty, either. In the distant past, in the absence of knowledge and tools, food circulated in a limited geographical area. The absence of appropriate technical means to prevent fresh meat and fish from spoiling was partly offset by preservation methods, more and more refined over time, involv-ing saltinvolv-ing, dryinvolv-ing and the use of spices. Technological innovation, especially in the nineteenth century with the preservation of food in cans by the French baker Appert, then contributed to a different relationship with food with respect to the quantity of supply and the quality aspects of handling, storage and logistics of food (Albisinni, 2005). The socio-demographic transformations arising from Europe’s economic development in the twentieth century (rural migration, urbanisation, ris-ing female employment, commutris-ing, etc.), the increase in household income, the growth and differentiation of demand, and new and different eating habits stimu-lated, on the one hand, deep innovations in product and process and, on the other, a significant transformation in the organisation of production and labour (Bellig-giano, 2009). The process of development of the food system, with the changes brought about since the 1960s with the “green revolution”, has also tied agricul-ture to industrial processes for maximum yield, and this has resulted in intensive agronomic and livestock systems, with massive use of chemicals, pesticides and fertilisers, limited variety of cultivars and high-output breeds to provide uniform products, as well as the inevitable exploitation of soils and heavy pollution of land, water and air (Giuca, 2009).

Following the general logic of the consumer market, foods began to be con-sumed farther from where they were produced, adding more steps between pro-ducer and consumer and extending the supply chain, and relegating direct sales and other forms of short chain to a marginal position.

The development and expansion of long chains and the simultaneous mod-ernisation of production processes and standardisation of products, while giving

more or less measurable merits to food, have had a significant impact on the glob-al socio-economic set-up and on the sociglob-al, economic, environmentglob-al and culturglob-al costs related to it, weakening the link between production processes and their lo-cal contexts (Paradiso, 2010). Methods of food processing, in fact, have been detri-mental for local and artisan producers, favouring large-scale industrial processes based on uniform quality and standardised flavours. In addition, the changes in time taken for eating or digesting food, as well as in the spaces for processing, packaging, handling and storage, continually present sensitive issues of risk to human health.

Over the past two decades a new model of production and consumption has developed, with alternative strategies that aim to diversify production and distri-bution of agri-food products and to rebuild a relationship between consumer and producer - and the agricultural, social, cultural and territorial world - with respect

for the environment. Most of so-called “food movements”6 maintain the need to

re-locate the processes of production and consumption, meaning relocating business in small and medium-sized enterprises in the area, encouraging diversification, creating space for local indigenous varieties, implementing methods for sustaina-ble agriculture and reviving the habit of buying from the producer (Norberg-Hodge, 2005). And today, what counts for the consumer is no longer the incremental dy-namics dictated by the logic of “more is always better”, but the dynamic expressed by highly motivated niches where food safety and authenticity become essential objectives (CENSIS and COLDIRETTI, 2010), along with recovery of local knowledge about production and consumption of foods.

The socio-economic context, the strong changes in consumption patterns and public policies (food safety, rural development, renewable energy sources) affect production and consumption practices (with new competitive strategies based on value creation, differentiation and qualitative excellence), stimulate the re-internationalisation of processing and reorientation towards quality products, and a shortening of physical, social, cultural and economic distances between the worlds of production and consumption. All this focuses the attention of the media and policy makers and provides impetus to the development of short chain forms. 6 According to Codeluppi (1988), today’s integrated agri-food system simultaneously produces con-sumer goods and patterns of behaviour; in this context the concept of “food movement”, analysed on a local level, has been defined as “a collaborative effort to build a self-sufficient local food economy in which production, processing, distribution and consumption of food are integrated ac-tivities with the goal of improving economic, environmental and social health in a given place” (Kloppenburn et al., 2000).

The rediscovery of the territorial dimension of production and

con-sumption in Common Agricultural Policy

Generally, the territorial dimension of production and consumption of food is central to a rediscovery that, albeit in different forms, is as much about north-ern Europe and continental realities as about those of Mediterranean Europe, and touches on rural development processes (Grando, 2009). For this reason, the

Committee of European Regions, in its recent opinions7, considers it essential to

promote short distribution channels and direct sales, and calls for their integra-tion into overall agricultural producintegra-tion policy in EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP); through forms of short chain, producers can regain profit margins eroded by negotiation rules and conditions of sales in force in agri-food chains with highly concentrated commercial power, making it possible not only to create a strong link between producer and consumer, but also making it easier to ensure the trace-ability of products, reassuring consumers as to the origin of the products they con-sume. Short distribution channels, according to the Committee, should not only aim to reduce the number of intermediaries between producers and consumers, but should be able to invigorate the local and regional supply chain; in this sense, the aim is a “local food system”, defined as “a combination of four factors: a short chain; a limited physical distance between the place of production and place of consumption; a process that takes into account factors such as transport, distribu-tion, waste treatment, renewable energy, marketing, promotion and quality con-trol; a process that is managed at the local and regional level”.

The development of short chain systems, as in the previous program to support rural areas, is supported in the 2007-2013 policy for rural development through actions aimed at improving farmers’ income, reducing the economic bur-den of intermediation, and providing services to the population, such as local mar-kets. It has been shown that shortening the supply chain can contribute to the revitalisation of rural areas (Knickel and Renting, 2000), partly through synergies with tourism (Brunori et al., 2002), as well as stimulating a new model of rural development (De Roest and Menghi, 2000; Renting et al., 2003).

Although the short chain is fast-growing, but still limited, and its contribu-tion to rural development cannot be quantified, it is impossible not to recognise the 7 Opinion of the Committee of Regions “Local agri-food systems”, adopted in plenary session on 27 and 28 January 2011 (OJ C 104 of 2.4.2011) and Opinion of the Committee of Regions “For an ambitious European policy favouring quality schemes for agricultural products”, adopted in plenary session on 11 and 12 May 2011 (OJ C 192 of 1.7.2011).

ability of this form of marketing - and the simultaneous strengthening of the

mul-tifunctional role of farms8 - in creating value in rural areas (Raffaelli et al., 2009).

At a recent conference on local agriculture and short supply chains9, the

European Commission said that 15% of EU farms sell more than half of their pro-duction locally and, whilst noting contradictions (in the face of demand for local products, supply is still not well structured and not widely accessible) and bias (why help uncompetitive farms that produce for niche, often luxury, markets?), the EC argues that short chains, appropriately structured, help farmers to obtain higher revenues from the market for their products and to maintain employment in rural areas. The local community, in fact, reaps economic, social and environ-mental benefits, by promoting products and the territory, protecting biodiversity and developing culture and traditions.

For these reasons, in the proposal for the 2014-2020 CAP10 the measure on short chain is referred to as strategic, and specific and innovative tools are dedi-cated to it. In this sense, interventions are called for to produce a strong impact on the development of rural areas and, in particular, incentives for the creation of short chains, the formation of producer groups, support for innovation of busi-nesses involved in short circuits, and incentives for the development of integrated actions to link tourism and agriculture; all these could also become the subject of specific sub-programs of intervention.

According to the European Commissioner for Agriculture and Rural

Devel-opment, Dacian Cioloș (2012), one of the renewal elements of rural development

policy after 2013 will be to “re-establish communication among major urban user areas and surrounding production areas, favouring market initiatives in cities”; and if, on the one hand, the new CAP indicates the desire to build “an agricultural policy for all and for all types of farms” to develop short chains, proposing meas-ures to support small farmers and strategies to raise awareness and the atten-tion of consumers, on the other hand both farmers and policy makers will have to make “a choice that requires breaking out of the usual schemes”. It is clear, in this sense, that farms, especially smaller ones, must begin to plan strategically 8 It should be remembered that agriculture today is based on two cardinal points of economic

diversi-fication and multi-functionality, meaning it no longer embodies a single production orientation but expresses new ecological, social and cultural functions (rural tourism, education, therapy, renew-able energy sources, etc.) which can drive territorial development (Henke, 2004).

9 European Commission, Agriculture and Rural Development, Conference “Local agriculture and short food supply chains”, Brussels, 20/04/2012, http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/events.

10 European Commission, Agriculture and Rural Development, Legal proposals for the CAP after 2013, http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/cap-post-2013/legal-proposals/index_en.htm

and have a development plan for distribution; the organisational aspect of short chain forms, in fact, affects both the calibration of specific production regarding the allocation of products and the organisation of work in relation to chosen sales methods (Cicatiello, 2008). Of course, these decisions are influenced by the farm’s economic resources, the characteristics, knowledge and cooperation of the farm-er and his family, geographical location, the socio-economic, environmental and landscape context, proximity to roads and urban centres, and tourist attractions in the area (IRUR, 2011).

Short chain experiences in Italy

The short chain, according to the forms and places where all its component activities take place, calls for a level of organisation and differentiated commit-ment on the part of businesses, with a diversified spread based on territorial con-texts, on characteristics of agricultural sectors and on types of products.

Numerous studies within North European and North American markets

have investigated the most common forms of short chain11: direct sales on farms,

farmers’ markets, weekly deliveries to families on a subscription basis, harvest-ing of products on the ground by the consumer, e-commerce and various modes of cooperation between producers and consumers, from more intense forms that provide a true sharing of business risk to “softer” forms involving the adoption of head of livestock. According to the literature examined by Raffaelli (Raffaelli et al., 2009), these case studies fail to provide a framework of the extent of the phenom-enon in quantitative terms, as data on the number of businesses and consumers involved are not readily available.

In Italy as well, the approach to knowledge about short chains has mainly

been through exploratory surveys of local situations12. As in other countries, we

see more and more integration of several parties - farmers, consumers, profes-sional farmers’ organisations, organic associations, cultural and environmental associations, public administrations - in promoting and implementing collective experiences of concerted short chains: in Italy you go from “Countryside friend” (COLDIRETTI) to “Women in the Field” (CIA), from “Earth Markets” (Slow Food) to 11 Between 2000 and 2006, 56 studies were made, in 7 important sector publications (Venn et al.,

2006).

12 Among these, we point out those conducted in Friuli Venezia Giulia (Gregori and Basso, 2006) and Umbria (D’Allestro, 2011) and the provinces of Turin (Coldiretti and CCIAA, 2008), Trento (Raffaelli et al., 2009) and Viterbo (Cicatiello, 2008).

AIAB initiatives, consumers’ movements and Legambiente, just to name a few, not to mention European and national campaigns for the consumption of fruit, vegeta-bles and milk in schools, which generate direct supply contracts in public school catering. As a result of these experiences, there is also growing interest in our country in quantitative analysis of short chains, closely linked to the availability of

data provided by organisations involved in the supply chain13 in various ways, and

which integrate statistical and census surveys from institutional sources.

The most classic form of short chain, direct sales on farms, farm and farm stay sites (e.g. lodging, wine cellars, olive mills, huts, dairy farms, warehouses, and areas for distribution and storage) and organised points (farm stands at fairs, harvest festivals and local markets and collective sales points like “showcase shops” promoted by cooperatives and consortia), is a phenomenon that has had a strong impulse in the last ten to fifteen years, though farms, particularly in the wine and olive oil and fresh produce sectors (fruit, vegetables and meat), have al-ways practiced it, but in a very marginal way, in areas not subject to strong urbani-sation where there remains a strong relationship of local sociability. On the other hand, especially in rural areas, there are fewer logistical difficulties in purchasing, such as proximity, timetabling and sorting, and direct selling is a deeply rooted phenomenon that usually involves a limited number of products in which the farm

specialises14.

Pending results of the last ISTAT census, in 2007 there were about 400,000 farms in Italy (22.1% of total Italian farms, 5% more than in 2000) that engaged in direct sales, mostly in southern Italy and the islands (65%), especially in Campania (16.8%) and Sardinia (12.7%), but also in Tuscany (12.4%) (ISTAT, 2007); revenue is estimated at 3 billion euro (COLDIRETTI and Agri2000, 2010).

Recently, forms of short chain derived from the U.S. and British experience (“pick-your-own”, “farmer’s market”) or from Northern European countries, such as “box schemes”, have spread to all regions.

The harvesting of fruits and vegetables by consumers directly in the fields on farms (“pick-your-own”) is an opportunity to personally select fresh and genu-ine products, at affordable prices through a friendly and recreational experience. There are only about 100 farms in Italy involved in the direct harvesting of products 13 Consider the National Observatory on Direct Sales (COLDIRETTI and AGRI2000, 2010), which

annu-ally processes data on farms enrolled in the Chamber of Commerce, and the Bio Bank data bank (www.biobank.it), which makes a yearly census of operators in the organic short chain.

14 When a farm decides to expand supply and offer a wider range of products for direct sales, it can also make agreements, join or create cooperatives with other farms (IRUR, 2011).

on the ground (COLDIRETTI and Agri2000, 2010); the experience is not very com-mon in our country but practiced in Northern Europe and North America, where it developed in the ‘30s and ‘40s, especially in the United States during the depres-sion after the Second World War, in which the price paid to producers for fruit and vegetables was so low that farmers could not cover the cost of picking, packaging and transport (Guidi, 2009).

Farmers’ markets, regulated in Italy by Legislative Decree no. 228/2001 and Ministerial Decree of November 20, 2007, are managed by farmers gathered in joint form or through their associations or by the staff of the municipalities that host them and promote them. COLDIRETTI’s Campagna Amica recorded 878 farm-er’s markets in 2011, located in urban centres or just outside town, with access by surrounding farms, for a total of 20,800 farmers and an estimated turnover of €

320 million in 201015.

Box schemes, the main form of direct sales in the United Kingdom, with 100-million-pound-sterling in sales in 2007 (Soil Association, 2007), are a form of distribution at agreed-upon intervals (usually weekly or fortnightly) of seasonal agricultural production, usually organic fruits and vegetables, organised directly by the farmer, but also by associations and cooperatives, for individual consum-ers or groups. Given a set price previously agreed upon, the customer accepts the contents of the box (basket/crate) and/or chooses some products. In Italy this form of direct sales mainly applies to the supply of products to JPGs, though there are examples in the sale of frozen foods and pizza at home and in home delivery by supermarkets to build loyalty among customers, especially older people.

Several regions have established regional registers for JPGs, a phenome-non for more than a decade, though the activities and purposes of these phenome-non-profit organisations were only defined by the law 244/2007. Individual consumers, fami-lies, relatives, friends or colleagues, motivated by ideological reasons or simply by affordability and family supply management, decide to buy food or commonly used products wholesale, to be redistributed among themselves, with an impor-tant reduction the final price in relation to the volume of purchase; the group is defined as cooperative, as the self-imposed criteria in the selection of suppliers (small producers and local suppliers) and type of consumption (local and seasonal foods, organic and/or integrated foods, fair trade products) are based on princi-15 Figures available at: www.campagnamica.it.

ples of ethics, equity, social solidarity and environmental sustainability16. Currently

there are about a thousand JPGs, each of which involves 20-25 families, but they

are difficult to census because they are formed (and disbanded) all the time17. In

the 2008-2010 period, JPGs increased by 59% and are concentrated in Lombardy (25%), Tuscany (13%) and Veneto (10%) (Mingozzi and Bertino, 2011).

Other innovative forms of short chain adopted in recent years in Italy have had good results; there are, for example, 1,435 raw milk vending machines outside farms or in towns, scattered in 92 provinces, one third of which are concentrated

in Lombardy18. The initial boom in the self-service sale of raw milk, however, has

been hampered by concerns about possible damage to health from ingesting milk that has not undergone any industrial treatment after milking, but only filtration and cooling to 4°C. In this way the milk, sold on tap in bulk via vending machine, using rechargeable keys, maintains all its nutritional properties, but must always be boiled, as pointed out in mandatory warnings posted on the dispensers. Safety from the point of view of sanitation is guaranteed by strict controls; unsold milk is withdrawn within 24 hours and used for the production of ricotta and cheeses.

In another way, using the “Adopt a sheep” format, the “ ASCA Agritourism Cooperative”, located in the heart of the Abruzzo National Park, has taken steps to raise awareness on the problem of abandonment of the Aquila mountains and en-vironmental degradation, suggesting long-distance adoption of a “Sopravvissana” breed sheep. In exchange for the cost of maintenance and rearing, each adopted animal can provide, in addition to its products (lambsmeat, milk, cheese, ricotta, wool, fertiliser), safeguards to the portion of land on which the flock lives. This experience of short chain has led the way in other situations, and has created a virtuous circle in the rural area for a decade, with a request for adoption/products

and land/hospitality19.

Finally, an all-Italian situation, begun in 2009 on the initiative of the “Valdipi-atta” estate, a Siena Wine brand with a protected designation of origin, “Nobile di Montepulciano”, the format is “tailor-made wine,” in which the farm produces custom wine, using part of the vineyard according to the needs of the consumer. 16 Though each JPG is founded for its own reasons, which may differ from one group to another, based

on this experience there is always deep criticism of the current model of consumption and global economy, together with the search for an immediately practical alternative, created through con-vivial moments, forms of experience and support - like the time bank - and barter and exchange of bicycles, books, utensils, etc. (Giuca, 2010).

17 Available figures on the national JPG network: www.retegas.org. 18 Figures updated to 15 July 2012 available at: www.milkmaps.com. 19 Figure available at: www.laportadeiparchi.it.

The customer is assisted by an expert in choosing the type of grape, directly in the vineyard, personally selects the preferred mix of flavours, and follows all phases of the production process through bottling and labelling (Business & Gentlemen, 2009). Begun as a new frontier of luxury and niche excellence, aimed at the U.S. market, this form of short chain can be accessible for all budgets, if produced us-ing certain methods, in all rural Italian wineries.

6. Conclusions

In the general development of the agricultural world and, in particular, the fragmentation of production and low profitability, it is clearly important to explore new models of entrepreneurship (Cicatiello, 2008), in which alternative forms of product marketing also play a decisive role, in which the farmer becomes an active player, entering the market in a new, innovative and creative way, also with the op-portunity to increase young people’s interest in the sector and foster generational renewal.

In this context, the various forms of short chain come into play, in re-locat-ing production-distribution-consumption circuits, enhancre-locat-ing the bond of agricul-tural production with the territory and favouring consumption in local markets. The potential benefit of the short chain generally recognised by producers and, in particular, of direct sales, is strongly linked, however, to locational, structural and production characteristics of farms. The direct relationship established between producer and consumer offers, as strengths for sellers, the opportunity to control price and added value, to exploit the quality and characteristics of the product, and to build customer loyalty, while also offering related services (e.g. amplitude of supply, timely deliveries, availability of recipes based on seasonal products); but there are critical elements related to logistics (especially for fresh products or farms far from towns or roads), breadth and quantity of supply (linked with season-ality of products) and, of course, the size of farms and their marketing possibilities (IRUR, 2011). Larger farms, therefore, which can sustain the cost of production in the face of the availability of technological innovation and adequate production volumes, have a non-exclusive approach to the short chain, using it in addition to traditional market channels; for smaller farms, however, the short circuit and di-rect sales represent a viable alternative for their very survival, which is, moreover, a key requirement for sustainable development of the territory. For farmers in this regard, it may be advantageous to operate within a network of actors, experiences and tools, in order to be able, so to speak, to re-accustom to the commercial

di-mension of their profession and to facilitate their communication and interper-sonal skills (Giuca, 2012).

The short chain thus makes it possible to experiment with new forms of marketing, modulated in relation to the interests of producers and consumers, and with positive effects for the collective/local community, shifting emphasis to the territory, the quality of production processes and consumption, and a rural development model based on multi-functionality and sustainability. These forms of sales, in fact, are part of a virtuous circle of local development that includes ru-ral tourism, educational activities, the promotion of local products, transformation and processing of agricultural products on the spot and on the farm, and various opportunities which refer to the productive, ecological, scenic, cultural and social importance of agriculture, and the diversification of activities and sources of in-come; without forgetting that shortening the distance food travels from the place of production to consumption can reduce environmental impact in terms of pack-aging, transport and energy.

On the demand side there is strong value in seeking a relationship with the producer “you know” and “who has good products” at affordable prices. However, direct sales or other forms of short chain do not always lead to a real drop in consumer prices; in this sense it would be desirable to have forms of physical or virtual aggregation of producers/products, to implement beneficial economic dy-namics for all stakeholders in the supply chain, and for the local context.

Bibliography

AIDA (IFLA), Il Libro verde della Commissione Europea sulla qualità dei prodotti agricoli, Il documento dell’AIDA, Rivista di diritto alimentare, 2009, III, 1, pp. 2-7. Albisinni F. (2005), Diritto alimentare tra innovazione, regolazione e mercato, Ri-vista di diritto alimentare, fasc. 4, 2005, pp. 565-590.

Belliggiano A. (2009), Percezione della sicurezza alimentare e nuovi modelli di organizzazione della produzione, Rivista di Diritto Alimentare, Anno III, n.4, pp. 42-44.

Brunori G. - Cosmina M. - Gallenti G. (2002), Le strade del vino nel Friuli Venezia Giulia, in Basile E. - Romano D. (a cura di), Sviluppo rurale: società, territorio, impresa, FrancoAngeli, Milano, pp. 398-429.

Business & Gentlemen (2009), Bottiglie su misura: un’idea Made in Italy, B&G, www.businessgentlemen.it.

Cicatiello C. (2008), La vendita diretta dei prodotti agricoli: un’analisi della si-tuazione locale, Tuscia Economica, n. 1, pp. 35-41.

Cioloș D. (2012), Agricolture locali e filiere corte: rafforzare la dimensione

lo-cale della politica agricola comune, Intervento di apertura del Commissario europeo per l’Agricoltura e lo sviluppo rurale alla conferenza sulle agricolture locali e le filiere corte, Bruxelles, 20 aprile 2012, http://ec.europa.eu/agricul-ture/events.

Codeluppi V. (1989), Consumo e comunicazione. Merci, messaggi e pubblicità nelle società contemporanee, FrancoAngeli, Milano.

CENSIS e COLDIRETTI (2010), Primo Rapporto sulle abitudini alimentari degli italiani, Roma.

COLDIRETTI - AGRI2000 (2010), Osservatorio internazionale sulla vendita diret-ta nelle aziende agricole, Quardiret-ta edizione, Bologna.

COLDIRETTI - CCIAA (2008), Le vendite dirette nella provincia di Torino, www. to.camcom.it.

D’Allestro S. (2011), Indagine sui gruppi di acquisto solidale in Umbria, www. associazionelegaliitaliani.it.

De Roest K. - Menghi A. (2000), Reconsidering “traditional” food: the case of Parmigiano reggiano cheese, Sociologia Ruralis, 40 (4), pp.439-451.

Franco S. (2007), Agricoltura biologica e «food miles»: la crisi di un matrimonio di interesse, Agriregionieuropa, Anno 3, n. 10, pp. 45-47.

Germanò A. (2009), Qualità alimentare: un’Europa, due sistemi, Rivista di dirit-to alimentare, III, 1, pp. 22-25.

Giuca S. (2009), Cultivar e razze autoctone delle aree rurali: tradizione e inno-vazione nella conserinno-vazione e nell’uso, in Giarè F. (a cura di), Mondi agricoli e rurali. Proposte di riflessione sui cambiamenti sociali e culturali, Roma, pp. 155-169.

Giuca S. (2010), Il principio di equità e solidarietà applicato agli acquisti: il caso dei GAS, in Briamonte L. - Giuca S. (a cura di), Comportamenti e consumi so-cialmente responsabili nel sistema agroalimentare, INEA, Roma, pp. 74-80.

Giuca S. (2012), Filiera corta, filo diretto produttore-consumatore, PianetaPSR, n. 11, www.pianteapsr.it.

Grando S. (2009), Esperienze di diversificazione qualitative degli alimenti: la ri-lo-calizzazione dei circuiti produzione-consumo, Economia agro-alimentare, n. 1, pp. 43-59.

Gregori M. - Basso C. (2006), La vendita diretta nell’agricoltura del Friuli Venezia Giulia: caratteristiche strutturali ed organizzative, Agribusiness Paesaggio & Am-biente, IX, 1, pp. 25-35.

Guidi F. (2009), Filiera corta: percorsi di innovazione tecnici, organizzativi e sociali nella gestione strategica delle nicchie. Esperienze in Toscana e in Provenza, tesi di dottorato, Università di Bologna.

Henke R. (a cura di) (2004), Verso il riconoscimento di un’agricoltura multifunziona-le, INEA, Roma.

Holloway L. - Kneafsey M. (2004), Producing-consuming food: closeness, con-nectedness and rurality in four ‘alternative1 food networks, in Holloway L. - Kneafsey M. (eds,), Geographies of rural cultures and societies, Ashgate, London, pp. 257-277. Knickel K. - Renting H. (2000), Methodological and conceptual issues in the study of multifunctionality and rural development, Sociologia Ruralis, 40 (4), pp. 512-528. Kloppenburg Jr. J. - Lezberg S. - De Master K. - Stevenson G.W. - J. Hendrickson (2000), Tasting Food and Tasting Sustainability: Defining the Attributes of an Alter-native Food System with Competent, Ordinary People, Human Organization, vol. 2, pp. 177-186.

IRUR (2011), La vendita diretta nel territorio transfrontaliero, Assessorato all’Agri-coltura, Provincia di Cuneo.

ISTAT (2008), Struttura e produzioni delle aziende agricole - Anno 2007, Roma. Lang T. (1996), Globalisation and the Challenge to the Organic Strategy, in IFOAM, Fundamentals of Organic Agricultural, Proceedings of the 11th IFOAM International Scientific Conference, Copenaghen, pp. 199-222.

Malassis L. (1973), Economie de la consommation et de la production agro-alimen-taire, in Malassis L. (a cura di), L’économie agro-alimenagro-alimen-taire, Edition Cujas, Paris. Mingozzi A. - Bertino R.M. (2011), Tutto bio 2012, Annuario del Biologico, Egaf Edi-zioni, Forlì.

Norberg-Hodge H. (2005), Pensa globalmente… mangia localmente, L’Ecologist ita-liano, n. 3, pp. 222-228.

Paradiso C. (2010), La filiera corta, Newsletter di sociologia, Anno VII, n. 5, www. newsletterdisociologia.unito.it.

Raffaelli R. - Notaro S. - Basani M. (2004), Potenzialità di “nuovi” strumenti economi-co-contrattuali di tipo partecipativo per la sostenibilità dell’agricoltura di montagna: la Community Supported Agricolture, Nuovo Diritto Agrario, Nuova serie, 1, pp. 211-225.

Raffaelli R. - Coser L. - Gios G. (2009), Esperienze di filiera corta nell’agro-alimen-tare: un’indagine esplorativa in provincia di Trento, Economia agro-alimentare, n. 1, pp. 25-41.

Renting H. - Marsden T. - Banks J. (2003), Understanding alternative food networks: exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development, Environment and Planning A, 35, pp. 393-411.

Seyfang G. (2008), Avoiding Asda? Exploring consumer motivations in local organic food networks, Local Environment, 13 (3), pp. 187-201.

Soil Association (2007), How to set up a vegetable box scheme, www.soilassociation.org. Sonnino R. - Marsden T. (2006), Beyond the divide: rethinking relationships between alternative and conventional food networks in Europe, Journal of Economic Geo-graphy, 6 (2), pp. 181-199.

Taylor J. - Madrick M. - Collin S. (2005), Trading places: the local economic impact of street produce and farmers’ markets, New Economics Foundation, London. Venn L. - Kneafsey M. - Holloway L. - Cox R. - Dowler E. - Tuomainen H. (2006), Researching European “alternative” food networks: some methodological conside-rations, Area, 38 (3), pp. 248-258.

Whatmore S. - Strassart P. - Renting H. (2003), Guest editorial: what’s alternative about alternative food networks, Environment and Planning A, 35, pp. 289-391.

From the land to the territory:

the role oF the Farmer in the short chain

Irene Canfora1

Italian legislation regarding farmer’s selling activities

Italian legislation, in outlining the legal framework for agriculture, has al-ways provided special regulation for what in economic terms is called “short chain” and refers to the regulation of direct sales of agricultural products to consumers.

In national law, sales activities organised by the farmer are crucial to defin-ing the discipline of farm enterprise in the Civil Code (Canfora, 2008).

On the regulatory level, in fact, the range of sales is the parameter for evalu-ating requirements for the application of the special statute for agricultural en-terprise. Verification of sale and processing of products carried out by the farmer makes it possible to extend the legal statute applicable to the farm, beyond activi-ties of livestock, crops and forestry that make up the farm’s main activity.

Currently, pursuant to Article 2135 of the Civil Code, amended by Article 1 of the Legislative Decree 228/01, the criterion of prevalence of products coming from the farm determines the extent to which the farm statute continues to apply, to activities that otherwise fall under the legal regime of a commercial firm.

Direct sales of products by the farmer, as part of the farm’s activities, have also (traditionally) been granted a corresponding special administrative discipline, in line with the requirement to provide special legislation for agricultural enter-prises compared to the discipline for commercial enterenter-prises: the different capa-bilities of farms are considered, both in general farm discipline, and on the level of administrative regulation of direct sales by the farmer, since farms are considered to have a weaker economic position in the market and therefore deserving of spe-cial regulation.

The special nature of the rules on direct sales of products by the farmer can also be found in the prior discipline in the Civil Code of 1942 (Iannarelli, 2009).

Think of the earliest special discipline, regarding wine sales directly on farms, pursuant to art. 206, r. d. n. 62 of 21 January 1929 (the Regulation imple-menting the Single Text on public safety laws, Royal Decree No. 1848 of 6 Novem-1 Associate Professor of Agricultural Law, University of Bari.

ber 1926). Wine sale is a prime example of this special discipline, designed to pro-tect agricultural producers, primarily considered as vineyard landowners, when “the cellars of aristocratic families and even outside the market, but large-scale producers of prized and sought-after wines”, risked being framed in the context of acts of trade: the hypothesis recurs, in the debate on the reform of the Com-mercial Code, cited by Valeri as a classic type of sale by farmers that should be excluded from trade regulations, to exclude the sale of goods obtained from the fruit of the land from trade laws (Valeri, 1923). In this regard, in terms of trade rules, the 1929 law excluded the obligation to obtain a retail license for pouring wine and selling directly from cellars annexed to farmland structures. An exemp-tion from sellers’ requirements was then introduced for itinerant trading, pursuant to Article 9 of Law 327 of 5 February 1934: trade licenses were required of direct producers, while farmers were exempt from paying the deposit otherwise required of merchants.

In the post-war period, the regulation of commerce extended the simplifica-tion of the rules established for commercial activities to direct sales by agricul-tural producers (La Medica, 2004). The Trade Act no. 59, 1963, which remained in force and was only repealed with the L. D. of June 25, 2008, n. 112 (made into law August 6, 2008, n. 133), removed the requirement for farmers to obtain a license, individually or jointly “for retail, throughout the territory of the Republic, of crops or livestock products obtained from their own lands”, upon request to the mayor of the municipality where products are sold.

Trade legislation currently in force does not deviate from this set of rules: Legislative Decree n. 114/1998, art. 4, in defining the application of the law, ex-cludes “agricultural producers, individual co-op members, who conduct the sale of agricultural products in compliance with article 2135 Civil Code, the Law of March 25, 1959 n. 125 and subsequent amendments, and the Law of 9 February 1963 n. 59 and subsequent amendments”.

Art. 4 of L.D. 228/2001, amends this provision, defining the rules applicable to farmers who sell their products directly, by providing a simplified procedure for access to sales activities, to encourage agricultural enterprises to sell their products directly.

The arrangement differs depending on whether the sale takes place: in iterant form, including electronic commerce; or on outdoor areas of the farm, in-cluding the private areas available to farmers; or finally in a non-itinerant form on public areas or those open to the public.

changes introduced by art. 27 of Legislative Decree (simplifications) n. 5/2012, only requires informing the municipality where the farm is, and selling can commence as soon as notice is sent (rather than 30 days after receipt of the communication).

For outdoor sales in areas belonging to the farm or belonging to the busi-ness, L.D. n. 2/2006 has liberalised activity to the point of excluding even notice of commencement of activity.

If, however, the sale takes place on public areas or premises open to the public, it is mandatory to report to the mayor of the municipality in which the sale takes place (Albisinni, 2001).

There are two limits in how this provision is applied. First, it requires the observance of sanitary regulations in force, matched by the prohibition of direct sales by entrepreneurs found guilty of health violations and food fraud. Second, the provision establishes a criterion that affects the size of the enterprise’s activity,

individual and cooperative2, limiting the application of the rule beyond the general

criterion of prevalence, referred to in the first paragraph: if revenue exceeds that identified in c. 8, the general rules on trade apply (c. 8 provides that the amount of revenue from products not produced by the respective farms should not be more than € 160,000 for individual entrepreneurs and € 4 million for companies).

The discipline thus identified then applies to the sale of products by agri-tourism businesses, pursuant to Article 10 of Law 96/2006 (Albisinni, 2006).

The farmer’s role in the short chain in promotional legislation

The provisions mentioned so far testify to the favour for a farmer with re-gard to special rules for farms compared to commercial enterprises, which is also reflected in the regulation of sales activities, carried out by the farmer, when they fall under business activities.

In the most recent Italian legislation, however, the rediscovery of the role of the farmer in the short chain takes on a different meaning, which also takes ac-count of other factors. It operates primarily as a tool to rebalance the market. In fact, the reduction of the supply chain, as well as meeting the needs of entrepre-neurs for a greater return on their business (the farmer can achieve a profit mar-gin that would otherwise be dispersed in other segments of the supply chain), also contributes to the mirror and opposite consumer demand for a reduction in food 2 On the discipline applicable to entities and cooperatives that sell agricultural products directly,

prices3. These individually important economic aspects are supplemented with

other complementary objectives of collective protection: environmental protection (reducing the cost of transport of goods), but also social objectives of bringing citi-zens closer to rural reality.

One sees, then, a new central role for the farmer in the direct contractual relationship with the consumer; the law’s role is to promote and encourage this distribution channel of “direct sale” or “short chain”. In it, the local dimension of the market combines the interests of farms with those of consumers, indirect re-cipients of an economic and social benefit.

Normative instruments are therefore of a promotional nature.

First of all, we must recall the legislation on “Farmers’ markets” provided for in Article. 1, c. 1065 of the Finance Act 2007 n. 296/2006 and implemented

by MIPAAF decree on November 20, 20074. The legislation was not intended to

regulate sales (for these aspects, see existing legislation), but merely to identify the conditions for access to support measures. It provides for the establishment of areas for direct sales markets, for the benefit of entrepreneurs whose busi-ness is located “within the administrative territory of the region or within the areas defined by individual competent authorities”; for agricultural products from own farms (or from members of the cooperative) within the limit of prevalence stated in Article 2135 c.c.; with the exclusion of producers guilty of health violations or food fraud, who are forbidden to conduct direct sales, pursuant to Article 4 of Legisla-tive Decree 228/01.

This legislation, which aims to define “guidelines for the creation of markets reserved to farmers in art. 2135, including co-operatives”, established or author-ised by the municipalities, is then applied in regional legislation, which has pro-vided grants to set up direct sales markets (see, eg., Lazio Regional Law 28/2008, Article 2).

Other measures have been developed in the context of regional laws, in-tended to promote quality food products of the short supply chain, with the aim of encouraging consumption of local products: a recent regulatory trend, in fact, refers to “zero-kilometre production” (Losavio, 2011).

3 On this point, many studies and EU documents on farm prices and the need to monitor them along the food supply chain: see in particular the Commission Communication COM (2008)821 and works by the focus group in 2009. In Italy, see the AGCM study on the fruit and vegetable supply chain: IC28 of 7 June 2007.

4 For an analysis of the main legal aspects of Farmers’ Markets in Italian legislation, see in particu-lar: Alabrese et al., in Sirsi, volume 3/2008 of the Review of Food Legislation; Masini, 2007.

In this case as well, the laws refer to short chain of quality products, but the meaning is understood here in the broadest sense, in that it includes all sales activities, also via intermediaries that enhance local products, as for example:

- Increasing the use of local produce in catering services (Sardinia R.L. 1/2010,

Friuli R.L. 4/2010);

- Marketing of local products in retail outlets (Friuli R.L. 4/2010, Veneto R.L.

7/2008), which can also be done through the medium of industry agree-ments promoted at the regional level to exploit local products (Article 14 Lazio R.L. 29/2008; a similar provision in the Puglia Region has promoted supply chain agreements to encourage the supply of regional products in large retail outlets);

- The concentration of supply through official websites (Lazio R.L. 29/2008

provides for so-called supply groups (bid groups), which are the counterpart to joint purchasing groups of consumers.

Overall, regional legislation is directed primarily to protecting local produc-tion, relative to origin in the production area (regional) rather than the method of direct sales, which is subject to legislation on farmers’ markets described above.

Again on measures of a promotional nature, but in this case with regard to the protection of institutions and associations in the definition of the tax regime applicable for the circulation of goods, national legislation has defined “joint pur-chasing groups” (Art. 1, c. 266 of the Finance Act 2008, no. 244/07), which aim to exploit the short chain through a particular mode of supply of consumer goods, beginning with consumer initiative, in co-ops, which seek local suppliers of local products. Regional laws have also expanded the legislative initiative to increase di-rect sale of food products and quality, by supporting joint purchasing groups (Um-bria R.L. 1/2011, Lazio R.L. 29/2008, see Canfora, 2011).

Legislation on short chains and issues of compatibility with EU law

None of the provisions mentioned so far relate to business regulation, nor the content of contracts with consumers, which remain subject to general provi-sions. Rather, they concern the law of markets, by strengthening the local supply chain of products.As noted, in fact, these are rules on the promotion of products of region-al origin, which apply to the generic formulas of “short chain” and selling “km 0 products“: these terms even recall aspects of environmental relevance of regula-tory measures, themselves compatible with and exploited in European law.

The overlap of the two levels (regional product exploitation and protection of markets of local importance) emerged in the case concerning the approval of Veneto R.L. n. 7/2008, originally entitled “Standards to guide and support the con-sumption of agricultural products of regional origin”. In response to the first draft of the law, the European Commission made criticisms, noting that the law violates the rules on state aid and competition; thus, in the second version the term “re-gional products” was replaced with “0-km products” but without varying the ef-fects of content (Veneto Regional Law 3/2010).

One wonders, then - because these are measures that affect markets - if the provisions so far mentioned (without presuming to be complete) are compatible with EU law, in particular with respect to the rules of competition and free move-ment of goods.

Indeed, precisely because of the need to control the prices of food prod-ucts, the use of direct sales and the promotion of short chains are considered fully compatible with the goals pursued by the Commission, which says in its Green Paper on promotion measures and information provision for agricultural products: “Regional and local farming has hidden potential that is not currently being fully exploited. Regional and local markets are an essential meeting place for produc-ers and consumproduc-ers. They enable the former to receive the rewards for their la-bours more efficiently and the latter to contribute to the development of their local areas, reduce the environmental impact of their consumption habits and access a

wide variety of products rooted in their traditions and ways of life”5. In addition, in

the same document collaboration with the retail sector is deemed appropriate, to provide incentives for strategies to promote local agricultural products involving

shopping centres, neighbourhood stores or rural sales centres, markets, etc.6

In fact it can be said that the instruments for the promotion of short chains in agriculture can reach those goals of agricultural policy set out in article 33 of the Treaty (now 39 TFEU), which are difficult to reconcile, and whose convergence is even considered favourably to purposes of exemption from general competition 5 European Commission, Green Paper On promotion measures and information provision for

agri-cultural products: a reinforced value-added European strategy for promoting the tastes of Europe, COM (2011) 436 final, of 14.7.2011, p. 4.

6 Cf. p. 5: opposite assessment, in the name of competition principles of Community law, expressed by our Authority on Competition and the Market, in 2005, with the opinion of 19.10.2005 on L.D. 182/2005, containing “Urgent measures in agriculture and for public bodies in the sector, partly to counteract anomalous trends in prices in the food chain”, which included in art. 2 the fixing by the regions of a minimum percentage of selling space to regional agricultural and agri-food products, and a percentage of space reserved for farmers who conduct direct sales in public areas.

rules for agreements adopted in agriculture7: the direct sale of agricultural

prod-ucts in short supply chains, in fact, guarantees an increase in agricultural produc-tivity, improves the income of farmers, stabilises markets, guarantees security of supply and ultimately ensures reasonable prices for consumers.

More questionable may be the effect of exploiting only regional products, in light of the principle of free movement of goods. But we must consider the context of these provisions:

1) the choice to exploit agricultural products in regional markets under

Com-mon Agricultural Policy;

2) the importance of the local market, which has no effect on the broader

dyna-mics of the EU internal market. Think of the exceptions provided for in Regu-lation (EC) n. 852/04, in reference to the provision of a national reguRegu-lation of local markets, with the exclusion of rules designed for an intra-Community market;

3) the fact that these are measures on how to sell products and not to define

promotional legislative instruments on origin of products (worked out in the form of distinctive labels), which is of greater concern to the EU than anti-competitive effects.

Limits to the exploitation of regional products through brands of

origin

On this last question, it should be noted that regional laws seek legislation compatible with EU law, also for the exploitation of products of regional origin. This profile, moreover, is the completion of promoting food products in local markets but can result in a different impact on the market, because the legislation does not merely regulate on-site trade of local products. In fact, it produces a transposition of the wider local market and therefore falls within the Commission’s wide-rang-ing assessment of the effects and impact on trade among Member States.

In order to avoid conflicts with Community law, one solution adopted by the regions has been the use of a collective Community label referring to geographical indication of regional products. Recently, this model was adopted by Trentino to exploit quality products and, also recently, by the Puglia Region, which has intro-duced an experimental “products of Puglia” brand.

The Commission’s observations, regarding the violation of the rules laid 7 In the ever-changing interpretation of the Court of Justice of the provisions in Article 176, reg. (EC)