Accademic Year

2016/2017 Phd Course EMERGING DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIESMindfulness-Oriented Meditation

between Human and Digital

Research

Author

Alessio Matiz

Supervisor

Phd Course EMERGING DIGITAL TECHNOLOGIES

Accademic Year

2016/2017

Mindfulness-Oriented Meditation

between Human and Digital

Research

Author

Alessio Matiz

Supervisor

Contents

List of Tables iii

List of Figures v

Introduction 1

1 Mindfulness and meditation 3

1.1 Mindfulness . . . 3

1.1.1 History of the term . . . 3

1.1.2 Definition . . . 4

1.2 Mindfulness meditation . . . 8

2 My research on Mindfulness-Oriented Meditation from first-person perspective 11 2.1 Mindfulness in therapeutic interventions . . . 12

2.1.1 An experiment with Alcohol Dependence . . . 12

2.1.2 An experiment with Multiple Sclerosis . . . 15

2.2 Training in group vs. solo setting . . . 17

2.3 Mindfulness and non-conscious . . . 19

3 Mindfulness-Oriented Meditation in a research with EEG hy-perscanning 23 3.1 Reasons for MOM and EEG hyperscanning . . . 23

3.1.1 Biology and physiology of meditation . . . 25

3.1.2 Hyperscanning . . . 29

3.2 The Mindfulness-Oriented Meditation Training . . . 31

3.2.1 Mindfulness-oriented meditation in neuroimaging . . . 32

3.3 Materials and Methods . . . 32

3.3.1 Participants . . . 32

3.3.2 Stimuli . . . 33 i

3.3.3 Procedure . . . 33

3.3.4 Data acquisition . . . 35

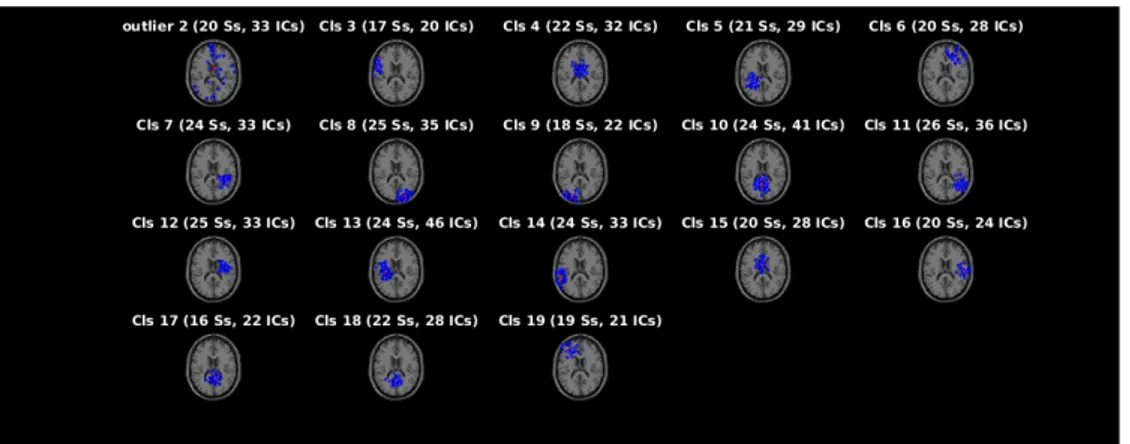

3.3.5 Data processing and analyses . . . 36

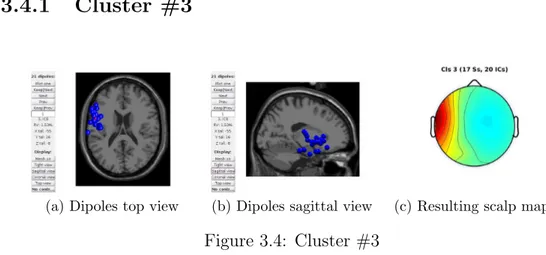

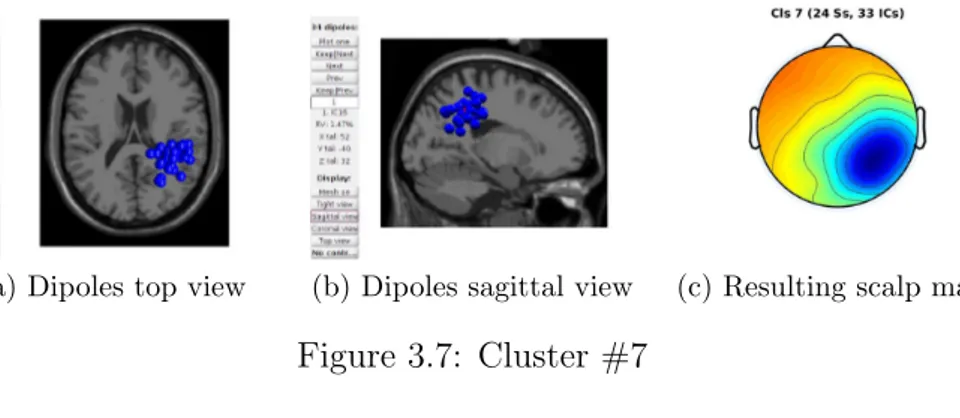

3.3.6 Statistics . . . 39 3.3.7 Software . . . 39 3.4 Results . . . 40 3.4.1 Cluster #3 . . . 40 3.4.2 Cluster #6 . . . 41 3.4.3 Cluster #7 . . . 41 3.4.4 Cluster #11 . . . 42 3.4.5 Cluster #12 . . . 43 3.4.6 Cluster #13 . . . 43 3.4.7 Cluster #15 . . . 44

3.4.8 Experience of subjects included in clusters . . . 45

3.5 Discussion . . . 46

3.5.1 Effects of Task variable . . . 46

3.5.2 Effects of Cond variable . . . 49

3.5.3 Interaction effects between Task and Cond variables . . 51

3.5.4 Resume . . . 53

3.6 Limitations . . . 54

Conclusions 57

Bibliography 61

List of Tables

2.1 Empirical studies of effects of mindfulness on implicit measures 21

3.1 The 4 experimental conditions . . . 34

3.2 Average expertise in significant clusters . . . 46

3.3 Resume of effects found for Task variable only . . . 49

3.4 Resume of effects found for Cond variable only . . . 51

3.5 Resume of effects found for interaction between Task and Cond variables . . . 51

3.6 General table of subjects . . . 89

3.7 Subjects contributing to each cluster of Independent Compo-nents . . . 90

List of Figures

1.1 The meditation process . . . 8

2.1 Results of a Mindfulness-Oriented Meditation training for per-sons with Alcohol Dependence . . . 14

2.2 Results of a Mindfulness-Oriented Meditation training for per-sons with Multiple Sclerosis . . . 16

2.3 Results of a mindfulness-Oriented Meditation training in group vs. solo settings . . . 18

3.1 Laboratory settings . . . 35

3.2 Electrode positions . . . 36

3.3 The 17 clusters of dipoles . . . 38

3.4 Cluster #3: dipoles and resulting scalp map . . . 40

3.5 Cluster #6: dipoles and resulting scalp map . . . 41

3.6 Cluster #6: Task X Band interaction effect plot . . . 42

3.7 Cluster #7: dipoles and resulting scalp map . . . 42

3.8 Cluster #11: dipoles and resulting scalp map . . . 43

3.9 Cluster #12: dipoles and resulting scalp map . . . 43

3.10 Cluster #13: dipoles and resulting scalp map . . . 44

3.11 Cluster #15: dipoles and resulting scalp map . . . 44

3.12 Cluster #15: Task X Cond X Band interaction effect plots . . 45

3.13 Resume of effects found . . . 54

Introduction

Aim of this thesis is the study of some aspects of meditation, in particular of a kind of meditation which aims at developing mindfulness. Mindfulness is a form of awareness of the present-moment perception, that should be sup-positionally in action before the process of associating personal judgements to the same object of perception.

The reason of interest for mindfulness meditation is due to the fact that re-search suggests that its practice is beneficial from a therapeutic point of view and that it can be seen as a path that can lead towards freedom and peace for individuals and, consequently, for society. Of course mindfulness medita-tion is not ‘the’ solumedita-tion, but for someone it can represent an effective help to release from psychological entrapments. In addition, mindfulness medita-tion can be seen as an instrument for peace because more mindful persons are probably less suscetible, in presence of problems, to responses connected with the use of violence. The line of separation between positive service and misuse of mental practices, as well as between personal spirituality inside a community and religious use of power, has always been very difficult to be drawn, but maybe an approach to this based on science and humanities can be fruitful.

Therefore this thesis, after an initial chapter with an overview on the con-cepts of mindfulness and meditation, reports in its first part some research carried out in the course of this doctoral programme on the usefulness of meditation in the two contexts of alcohol dependence and multiple sclerosis. The measures employed for them are taken in the so-called ‘first-person per-spective’ namely when persons give subjective self-evaluations through the use of validated questionnaires, in a way that science considers valid and reliable since only a few decades.

Instead the last part of this thesis investigates mindfulness meditation through the use of objective measures, represented by the observation of brain activa-tions estimated with the electroencephalography. This instrument has been widely used for the study of meditation, and in this particular situation it was employed with the aim of evaluating brain activity during mindfulness

meditation performed by a couple of persons while they were together and while they were separated in two different rooms. This research focuses at the role of company in the practice of meditation.

Bridge between these two parts is the description of two studies performed during this academic course. One is a research that investigates the out-comes of a mindfulness training in relation to the role of mutual exchange between learners and between meditation teacher and learners, comparing a mindfulness training delivered in a standard group setting with an equiva-lent training delivered in a solo setting. The other research is a review of publications with meditation which could assess mindfulness and its effects both at en explicit and an explicit level, often linking results produced from the subjective perspective with results from different and probably more ob-jective forms of quantification.

Chapter 1

Mindfulness and mindfulness

meditation

1.1

Mindfulness

1.1.1

History of the term

The word “mindfulness” is a psychological construct that comes from Bud-dhism, translation of the word “sati” in Pali language. It seems that this translation was first introduced (Shonin et al., 2015) in a 1890 judicial doc-ument by the Buddhist scholar Thomas William Rhys Davids (Chalmers et al., 1923), author also of an early Pali-English dictionary (Davids & Stede, 1921). Pali language is probably the most important inside Buddhist liter-ature (Gombrich, 2009, Preface), because in this language were written the texts considered to be the oldest and the most accurate translations of the 2500 years old-teachings of Gautama Buddha, from which Buddhism origi-nated.

The meaning of “sati” refers to memory, recognition, consciousness and it is directly linked to the word awareness. Inside Buddhism, its cultivation is the penultimate step of an eightfold path (Bodhi, 1984), a pedagogic method attributed to Buddha for the attainment of “nibbana”, the liberation of the individual from the chain of rebirths and of suffering (Gombrich, 2009). How to develop correctly this awareness can be evinced from various written souces and practices from different Buddhist traditions, but it is taught in particular in a text, which is considered to report directly the teachings of Buddha, entitled “Discourse on the Foundations of Mindfulness” (Silananda & Heinze, 1995). The empirical method described there is one of the tech-niques that currently falls under the term “meditation”. For this reason, this kind of technique is known as mindfulness meditation, a meditation aimed

at fostering mindfulness.

As the original teachings of Buddha were interpreted differently and some-times also probably wrongly from its disciples (e.g. Gombrich, 2009, Chap-ter 6), its words were written some centuries laChap-ter in a language presumably different from that in which he expressed them, and its followers founded a religious-like movement that today is divided in two main (Theravada and Mahayana) and many minor traditions, it is obvious that what arrived to the American scientific world till the second half of the 20th century was (and continues to be) quite difficult to grasp completely. However, at that time the American molecular biologist Jon Kabat-Zinn developed a program called “Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction” (Kabat-Zinn, 1982), in which the Buddhist mindfulness mediation, in conjunction with some yoga prac-tices, was taught in a standardized way (8 weekly meetings, each with a theoretical, a practical and a dialogic part). The work of Kabat-Zinn came after an Hinduism-based meditation program, called Transcendental medita-tion (Mahesh Yogi, 1969), had already been widely introduced in the United States (Cowan & Bromley, 2015), had already been studied scientifically (e.g. Wallace, 1970) and used for therapeutic purposes (e.g. Orme-Johnson, 1987). MBSR program’s popularity grew (Kabat-Zinn, 2003), it started to be in-troduced inside universities and hospitals and to be used for improving well-being and for trying to tackle mental and physical conditions. The reasons for its success could be probably linked to the adaptation of Buddhist concepts to scientific words, that could be accepted easily in a practice that was presented as a therapy (Kabat-Zinn, 2000). Furthermore, the standardized protocol of MBSR allowed the results of its application in many contexts to be com-parable. Research on mindfulness meditation flourished and this prompted interest also for other forms of meditation that are ubiquitous around all cul-tures (West, 1979). Because of the success in the results of the application of mindfulness meditation in clinical interventions (Baer, 2003) for treating, for example, depression, chronic pain, personality disorders, relapse in substance dependence, scientists started investigating the mechanisms underlying the psychological construct of mindfulness, term that search in an engine such as Google Scholar produces today more than 300’000 results.

1.1.2

Definition

Accepted definitions of mindfulness underline the role of attention, such as “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally” (KabZinn, 2009), or “bringing one’s complete at-tention to the present experience on a moment-to-moment basis” (Marlatt & Kristeller, 1999), while others stress the role of awareness, with definitions

1.1. MINDFULNESS 5 such as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experi-ence moment by moment” (Marlatt & Kristeller, 1999), or “the tendency to be highly aware of one’s internal and external experiences in the context of an accepting, nonjudgmental stance toward those experiences” (Cardaciotto et al., 2008), or “the clear and single-minded awareness of what actually happens to us and in us at the successive moments of perception” (Thera, 1972). What seems to emerge from literature is that mindfulness is a state of consciousness (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Shapiro et al., 2006), and linked in particular (Brown & Ryan, 2003; Brown et al., 2007) to its activities of aware-ness and attention, with the first being the conscious recording of sensory and mental data, and the second the instrument to extract particular infor-mations from this recording. However, for a long time there has not been an operational definition of mindfulness (Bishop, 2002) and the descriptions of mindfulness have not alway been consistent (Bishop et al., 2004). For this reason, an attempt to extract a definition can be done describing the forms of measuring mindfulness and proposing some terms that are linked to mindfulness.

From measures

An empirical way to understand the notion of mindfulness is through the analysis of the standard self-report measures that assess it in persons (Baer, 2011; Sauer et al., 2013). In the Cognitive and Affective Mindfulness Scale Revised (CAMS-R) (Feldman et al., 2007) there are four factors evaluated: attention, present focus, awareness, acceptance. The last component refers to an attitude towards experience that can be linked to the belief, inside Buddhist psychology, according to which human beings usually pursue those experiences that they consider as pleasant, avoid those considered as unpleas-ant and ignore those considered as irrelevunpleas-ant (Gunaratana & Gunaratana, 2011; Brown et al., 2007). This is, according to Buddhism, the source of suffering, because it locks the person in an unsatisfactory and endless circle. For this reason, the voluntary commitment in accepting all incoming present experience is peculiar to mindfulness.

Also the Five Factors Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) (Baer et al., 2006), similar to the Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills (Baer et al., 2004), is based on different facets of mindfulness, namely observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-reacting to inner experience, and non-judging of inner experience. The first three facets seem to be abilities derived from the ad-vancement in mindfulness, being respectively the ability to notice internal states and external stimuli, the ability to label internal states with words,

and the ability to behave less automatically and more consciously. The non-reactivity facet is similar to the acceptance factor of CAMS-R, as it refers to the inclination towards allowing feelings and thoughts to be experienced, but it adds something to this factor, as the authors include also the ability to letting go this content. Lastly, there is the non-judging factor, which refers again to the psychological mechanisms that pushes us in the automatic cate-gorization of all experiences as pleasant, unpleasant or irrilevant (Gunaratana & Gunaratana, 2011; Brown et al., 2007). This process is intrinsic in the hu-man mind and is fundamental in driving huhu-man lives, but ignorance about it can bound persons to their behavioral schemas, while focusing awareness on it can bring increased freedom in decision making. Recent criticism on mindfulness was based on misunderstanding about this concept, that does not imply a blind acceptance of any kind of event (e.g. personal mistreat-ments, bad company policies, wrong politic decisions), but that rather fosters an heightened awareness of mental processes, which can lead to more objec-tive and possibly more effecobjec-tive actions against unfair situations.

Another test for the assessment of mindfulness is the Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) (Brown & Ryan, 2003), which considers only the aspect of attention, and measures mindfulness indirectly, through the evalua-tion of its opposite, namely mindlessness. This concept is seen as the refusal to recognize or observe a thought, an emotion, or a sensation.

The Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (Buchheld et al., 2001) relies on a two-factor model, with the two aspects of presence and of acceptance referring respectively to the ability to sustain attention to the present moment experi-ence and to maintain the already described non-judging stance towards this experience.

A cognitive approach is applied in the less famous Langer Mindfulness/Mindlessness Scale (Haigh et al., 2011), which is based on the theories of information pro-cessing and creativity. According to this model, a mindful person is vigilant in the context, adaptive in thought and behavior and, for this, it is seen as a seeker and producer of novelty.

All the scales presented here deal with mindfulness as a personal stable trait, that can be linked or not to meditation. The Toronto Mindfulness Scale (Lau et al., 2006) instead evaluates mindfulness as a state, not rooted in the struc-ture of the person, but as developed for a short period of time. It also investigates mindfulness as constituted by two factors, called by the authors of the test “curiosity” and “decentering”. Both depict with a different touch the well-known ability in attending with awareness the present moment expe-rience: the first adds to it the quality of curiosity, the second underlines the possibility of living this experience with some distance and disidentification.

1.1. MINDFULNESS 7 Associations and distinctions

Besides the aspects that emerge from the tools used for the assessment of mindfulness, another way that can be useful in order to understand the con-cept of mindfulness is through the concon-cepts that can be associated with mindfulness, underlining similarities and differences. First of all, mindful-ness can be correlated to self-knowledge, but the difference between them is that mindfulness is a process of self-observation, while self-knowledge is a state resulting from many self-observations (Bishop et al., 2004). What can bring confusion between these two concepts is that also mindfulness can be enhanced through trainings such as meditation. For this reason it can be considered also an ability (Ludwig & Kabat-Zinn, 2008).

Another ability comparable to mindfulness is that of mentalization, which refers to figure personal thoughts, feelings and desires in order to understand individuals’ behaviors (Fonagy et al., 2004). The activity of mentalization can be applied to the self and to the others. Mindfulness, in addition to allowing access one’s own mental content, permits also to follow the contin-uous flowing of this content. It has been proposed that mindfulness allows the manifestation of mentalization (Wallin, 2007).

However, the concept that fits mindfulness the most is that of awareness. This word is linked to perception, memory and consciousness (Merikle, 1984): there can be indeed perception with or without awareness (Merikle et al., 2001), meaning that an information that we receive can be experienced con-sciously or can be stored in our memory without our conscious knowledge of possessing it. For this, awareness is an ability that all human beings commonly and involuntary use. Mindfulness can measure to which extent a person generally uses this ability and so mindfulness can be linked to an enhanced quality of consciousness (Brown & Ryan, 2003).

Another peculiarity of mindfulness can be evinced from a reflexion about rumination, a maladaptive form of self-reflexion (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). During this mental activity a person can be aware of the content of its thoughts (i.e. the person experiences them consciously), but is usually unaware of the full extent of this process, till the point that it can be linked to serious forms of psychopathology, such as depression. In this context mindfulness trainings have been used as an useful therapy for contrasting relapse (Morgan, 2003) and the increase of mindfulness has been correlated to the development of metacognitive awareness (Corcoran et al., 2010). This is an higher order form of awareness, that makes a person aware of its flow of conscious thoughts and causes a process of “disidentification” from the men-tal content: thoughts can be considered as transient menmen-tal events, distinct from the self (Teasdale et al., 2002).

Finally, the concept of mindfulness can be explained describing its role in-side its original context, namely mindfulness meditation. During its practice the meditator engagement usually follows a defined cycle (Malinowski, 2013) depicted in figure 3.13: at the beginning he focuses attention on an object (e.g. breath, body) and tries to maintain this focus; after a while this fo-cus inevitably fades and mind involuntarily starts wandering, in a process of mental time travel (Killingsworth & Gilbert, 2010); this process goes on till the person recognizes this attentional shift, becoming aware that the content of its mind is not the original object of focus (breath, body), but another thought that occupies its mind (e.g. an unfinished duty, a future appoint-ment); the cycle closes with the step of letting go this thought and with the re-focus on the original object of meditation. According to my experience, the particular moment of awareness when the practitioner catches the mind wandering is the instant of mindfulness: this seems to be an higher order level of awareness, because the person sees his self engaged in conscious thoughts, and for this it is like a spike in the quality of consciousness.

Figure 1.1: The meditation process (Malinowski, 2013) in a Focused Atten-tion practice

1.2

Mindfulness meditation

As explained in section 1.1.1, mindfulness meditation is considered as a way to train and improve mindfulness. Instead, meditation in general is a

train-1.2. MINDFULNESS MEDITATION 9 ing aimed at a variety of scopes (Lutz et al., 2008b), as for example well-being (Fredrickson et al., 2008) or relaxation. A classification of meditation types (Lutz et al., 2008b) divides the practices according to the way in which they use attention, looking at the instructions given to practitioners and also at neuroscientific analyses (Cahn & Polich, 2006): in those with “focused at-tention” (FA) or “concentrative”, attention is concentrated on an established object (e.g. breath, body parts) and the meditator tries to maintain this fo-cus; in those labeled “open monitoring” (OM) or “insight”, attention is not concentrated on an object but distributed over the present and continuously-changing experience.

Examples of FA meditations are ¯An¯ap¯anasati (Bhikkhu, 1980; Fabbro et al., 2014) and Sahaj Samadhi (Baijal & Srinivasan, 2010), both with focus on breath, or meditations with focus on body parts, or even meditations with focus on the repetition of a mantra (Vago, 2012; Baer, 2003), such as Trascen-dental Meditation (Wallace, 1970), which someone instead considers as a form of meditation distinct from FA or OM (Travis, 2011). OM meditation is con-sidered to be found in some forms of Vipassana (Manna et al., 2010) and in some forms of Zen (Austin, 1999), or, at least, in some parts of them. This is because some other variants of Vipassana (Hart, 1987; Cahn et al., 2010), for example, use both FA and OM practices, one after the other. A possible explanation for the combination of FA and OM practices could be that the first form of meditation is useful for the stabilization of attention, which can be successively expanded to the ongoing flow of the mental content during the second form of meditation (Malinowski, 2013).

Also during Loving-Kindness Meditation both practices are used: in this form of meditation practitioners induce some positive feelings (e.g. compas-sion, forgiveness) towards themselves and other beings; for this reason this meditation is sometimes considered outside the subdivision between FA and OM practices (Vago, 2012; Tomasino et al., 2013). A three-fold partition be-tween concentrative, open-monitoring and compassionate meditations is also present inside Tibetan Buddhism (Lutz et al., 2007).

It is important to underline that mindfulness can be developed both with FA and with OM practices (Lutz et al., 2007), and, at the same time, that there are FA or OM practices not aimed at developing mindfulness. An ex-ample of this could be Qigong (Pan et al., 1994), a meditation with a variant called “concentrative” and another “non-concentrative”, which reportedly is more mindfulness based (Cahn & Polich, 2006). However, the classification reported in this case was still considering the difference to be between con-centrative and mindfulness practices, with the first that had their extreme in yogic meditations, and the second in Zen meditations. Authors could roughly characterize this difference also in terms of electroencephalographic

activity findings in early studies (alpha blocking). Evidences of differences between FA and OM practices at the neurophysiological level have anyway been found (Manna et al., 2010).

Some of the forms of meditation that have been considered to promote mind-fulness have been included inside trainings as “mindmind-fulness meditations”; however, as in part explained, there is no clear relation between the style of meditation and the label of mindfulness meditation (Vago, 2012). There are a number of trainings that claim the use of mindfulness meditation, the most famous being the MBSR introduced in section 1.1.1. This training was initially named Stress Reduction and Relaxation Program and was officially applied for the first time for relieving chronic pain in healthy subjects (Kabat-Zinn, 1982). It was later applied for helping in the treatment of many mental and physical conditions such as stress, anxiety, depression, and sleep distur-bances (Grossman et al., 2004; Bohlmeijer et al., 2010). MBSR includes FA meditations on breath and on body sensations, an OM meditation and Hatha yoga practices (Chiesa & Serretti, 2009).

After the success of MBSR, other programs were created in order to cope with particular disorders (Baer, 2003). Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Ther-apy (Segal et al., 2002) was designed for the prevention of depression relapse, integrating mindfulness meditation with elements from cognitive-behavioral therapy. Also Dialectical Behavior Therapy (Linehan, 1993) implemented this integration for the treatment of borderline personality disorder. The Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (Hayes et al., 1999) includes some mindfulness meditation procedures inside methods based on the theoretical framework of the contemporary behavior analysis and is used for a broad spectrum of psychopatologies (e.g. phobias, depression, psychosis) (Hayes et al., 2006). Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (Witkiewitz et al., 2005; Bowen et al., 2009) was created for prevention of relapse in substance depen-dence and Relaxation Response (Benson & Klipper, 1992) for promoting cardiovascular health and wellbeing.

Chapter 2

My research on

Mindfulness-Oriented

Meditation from first-person

perspective

In this chapter part of the research of my group on mindfulness medita-tion will be presented, the other part being in the next chapter. The work described here starts with the details of two publications, where a mindful-ness training has been applied on clinical samples with therapeutic purposes. Then a publication of review about mindfulness and non-conscious is pre-sented and finally there are the results of an unpublished research about mindfulness trainings delivered in group and in solo settings.

The framework inside which my work took place is that of the research of professor Franco Fabbro in neurology and psychology, with focus on reli-gion, spirituality, meditation and personality. Publications covered topics such as the occurrence of spontaneous thoughts during praying in medita-tors vs. controls (Fabbro et al., 1999), the influence of cortical lesions on self-transcendence (Urgesi et al., 2010), meta-analysis of fMRI studies with med-itation practices (Tomasino et al., 2013), the influence of mindfulness medi-tation on creative thinking (Capurso et al., 2013), the improvement of char-acter in healthy individuals thanks to a mindfulness training (Campanella et al., 2014), the mechanisms underlying meditations from in Hinduism and Buddhism (Tomasino et al., 2014), or the implicit and explicit effects on religious/spiritual self-representations of a mindfulness training (Crescentini et al., 2014).

In this area of work converged the interest of professor Massimo Bergam-asco, who, starting from a background in mechanics, robotics and virtual

reality, reached the study of consciousness, with its evolutionary aspects in vertebrates (Fabbro et al., 2015), the neural dynamics underlying the levels of consciousness (Bonfiglio et al., 2013) till its minimum in critical condi-tions (Carboncini et al., 2014), and the study of embodied mind experiencing, in particular the sense of ownership and agency about illusory body parts and movements under virtual and mechanical stimuli (Padilla-Casta˜neda et al., 2014; Tidoni et al., 2015), and the influence of personal hypnotizability in proprioceptive perception of limbs (Padilla-Castaneda et al., 2015).

2.1

Mindfulness meditation and personality

in therapeutic interventions

As the purpose of medical science it the recovery from of conditions of mental and physical illness, this path started with the application of a mindfulness training to groups of persons who could benefit from it thanks to the self-regulation determined by the fostering of self-knowledge (Brown & Ryan, 2003). Clinical populations chosen for this intervention were subjects with alcohol dependence in one case and subjects with multiple sclerosis in an-other.

In both cases past research suggested that mindfulness meditation could be helpful for these persons and, at the same time, studies had not yet covered the relation between the therapeutic effects of this training and the possible variations in personality profiles of the persons who meditated, which was the topic on which my group had worked previously. Lastly, prevalence of these two disorders in general and in the geographical region of my reseach group in particular guaranteed that an adequate number of subjects could be available for the study.

2.1.1

An experiment with Alcohol Dependence

In this published research (Crescentini et al., 2015) a group of persons with alcohol dependence (AD) was investigated, in order to assess whether a mind-fulness training (a Mindmind-fulness-Oriented Training in particular, described later in section 3.2) could lead to changes in mindfulness abilities, person-ality traits and levels of relapse risk. For this purpose, two subgroups were randomly formed and to one subgroup an 8-week mindfulness training was delivered in addition to the usual treatment, which consisted in the weekly meetings of the local network for the maintaining of abstinence from alcohol. The other subgroup, useful for comparison, did not modify this usual treat-ment. The so-formed subgroups resulted not different in terms of age, sex,

2.1. MINDFULNESS IN THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTIONS 13 years of education, cognitive level and severity of alcoholic dependence. As explained in section 1.2, mindfulness meditation programs have been de-veloped used for persons with substance addiction. For this study in par-ticular, relapse prevention was the target of the intervention: as relapse can be linked to events with strong emotional distress due to difficult situ-ations or painful memories or overwhelming worries, and, at the same time, automatic-pilot answers to it (Breslin et al., 2002) with compulsions in the use of the substance, mindfulness meditation seemed, since the very begin-ning of its introduction in the context of therapeutic interventions (e.g. Mar-latt & Marques, 1977), an useful instrument for dealing with this problem. This is because the theoretical foundations of mindfulness meditation (Gu-naratana & Gu(Gu-naratana, 2011) look at the the management of personal un-wanted thoughts and at the promotion of de-automatization. Research in-deed showed that promoting awareness of the burden of negative thoughts, instead of avoiding it, could explain in part the effectiveness of mindfulness meditation in the prevention of substance use (Bowen et al., 2007), and that mindfulness meditation could diminish automatic behaviors (Kang et al., 2013). However, there is not a complete explanation of the mechanisms in action during mindfulness meditation trainings for persons with problems with substances (Witkiewitz et al., 2014), so the research described here fo-cused in particular on the relation between relapse reduction and personality amelioration following a mindfulness meditation training.

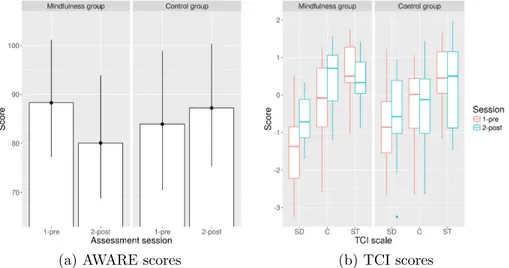

Relapse measures in the two groups consisted in the number of persons who had a relapse event during the 8 weeks of the study, and the score of a validated self-administered questionnaire, the Advanced Warning of Relapse (AWARE) scale (Kelly et al., 2011). Assessment of personality traits of the persons were also performed with the Temperament and Charachter Inven-tory (TCI) (Cloninger et al., 1994) tool, in order to observe whether this factor could be critical in the addictive behavior. This assessments were carried on in the two groups both before and after the mindfulness training intervention.

Results showed, first of all, that only the subjects who received the train-ing improved in one of the mindfulness abilities typically developed by a training, in particular in the ability of explicitly describing one’s own expe-rience (Baer et al., 2006). Of importance, this improvements were correlated with the amount of practice executed during the 8 weeks: in each training the participants are indeed requested to meditate at home daily in order to develop the typical mindfulness abilities.

In the group which received the mindfulness training, no relapse events were reported during the 8 weeks of observation, while in the control group 3 per-sons reported of alcohol consumption one or more times during these same

8 weeks. The statistical analysis of the AWARE scores was consistent with this data on relapses, showing an interaction effect within the variables of group and time of assessment: this meant a different evolution in the relapse risk in the two groups, with the scores that decreased in the treated group, while in the control group increased.

The results of the analysis on the personality traits were consistent with the TCI model, that combines both innate temperament traits and changeable character aspects. The temperament remained stable in both groups, while the character resulted to be modified significantly in the group that received the training. This effect, already shown in healthy subjects (Campanella et al., 2014), seemed to suggest that mindfulness modulated the character. The changes concerned in particular the aspects of self-directedness and of cooperativeness, meaning that the persons that practiced mindfulness had become more mature and balanced both at the intrapersonal and interper-sonal level, i.e. they seemed to have improved both the relation with their self and also the relation with the others. This strengthening of the char-acter seems to be protective factor against the development of personality disorders (Svrakic et al., 1993) and, consistently with what showed by present study relapse data, against the risk of relapse in substance use (Le Bon et al., 2004; Verheul et al., 1998).

(a) AWARE scores (b) TCI scores

Figure 2.1: Results for a mindfulness-treated group vs. control group with persons with Alcohol Dependence, illustrated in terms of development of (a) relapse risk (higher score corresponds to higher risk) and of (b) development of personality (higher score, better condition; SD = self-directedness, C = cooperativeness, ST = selt-transcendence)

2.1. MINDFULNESS IN THERAPEUTIC INTERVENTIONS 15

2.1.2

An experiment with Multiple Sclerosis

This longitudinal study was similar to that presented in section 2.1.1. Differ-ently from the other research, in this the population of interest was a group of persons with Multiple Sclerosis (MS), a degenerative disease of the central nervous system which causes the demyelination of nerve fibers and whose symptomatologic progress usually develops with chronic inflammations al-ternated by periods of apparent relaxing (Noseworthy et al., 2000). There’s no therapy for interrupting the progression of disability, but treatments are useful in order to speed recovery from attacks and manage symptoms. Symp-toms of MS include weakness, visual impairment, incontinence, fatigue, and cognitive loss (Chwastiak et al., 2002). With this physical impairments there are typically associated neuropsychiatric concomitants, such as depression, anxiety, irritability and anger (Feinstein, 2007).

In order to help MS patients in coping with their difficulties, mindfulness-based interventions have started to be used (Mills & Allen, 2000) and results have shown that they can be useful for coping with anxiety, depression and fatigue, in order to improve the MS patients quality of life (Simpson et al., 2014).

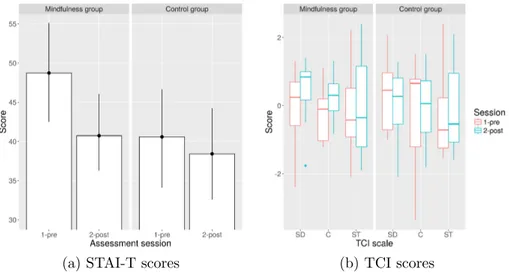

For the research described in present section, the experimental protocol was the same used with persons with alcohol dependence already described, with the formation of 2 subgroups from the initial group of patients, the feeding to only one of the groups of the mindfulness training in addition to the usual treatment (the other group was treated as usual), and the assessment in the two groups before and after the 8 weeks of the training. This assessment was about symptoms of anxiety and depression and, again, personality.

In MS research personality assessment is considered to be important because 20-40% of MS patients are affected also by personality changes (Stathopoulou et al., 2010), and this is thought to deteriorate their coping resources and worsen their quality of life (Bruce & Lynch, 2011). In the study being re-ported here, two different measurements of personality were used: the Tem-perament and Character Inventory previously described, and the Big Five Inventory (BFI) (John et al., 1991; John & Srivastava, 1999), which classifies personalities according to main 5 dimensions (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and openess).

Results of the study indicated that the mindfulness training was effective in an overall development of the typical mindfulness qualities, modelized accord-ing to the 5-facet model described in section 1.1.2; of course, for participants in the control group this effect did not occur. Regarding personality, the assessment with TCI showed the same results obtained in the study with the group of persons with alcohol dependence: the training modulated the

character traits in the mindfulness group, leading to an amelioration of the persons in the relation with their selves and with the others. The assessment with BFI exhibited an improvement of the mindfulness group in the dimen-sion of conscientiousness. This means that, according to this tool, individuals tent to behave more efficiently and to result more reliable. The effectiveness of the training could be deduced also by the outcomes from the assessment of the anxiety trait level: only the group of persons who meditated ended with a significant reduction.

In resume, this research highlighted that an 8 week mindfulness training could promote mindfulness abilities and personality characteristics useful for coping with the heavy psychological burden induced by the disabling disease of MS. The lowered level of the anxiety trait induced by mindfulness in these persons testifies it and confirms (Burschka et al., 2014; Bogosian et al., 2015) that meditation can be an adjunct for the management of MS.

(a) STAI-T scores (b) TCI scores

Figure 2.2: Results for a mindfulness-treated group vs. control group with persons with Multiple Sclerosis, illustrated in terms of development of anx-iety trait (higher score corresponds to higher anxanx-iety) and of development of personality (higher score, better condition; SD = self-directedness, C = cooperativeness, ST = selt-transcendence)

2.2. TRAINING IN GROUP VS. SOLO SETTING 17

2.2

An experiment with mindfulness

medita-tion in group and in solo settings

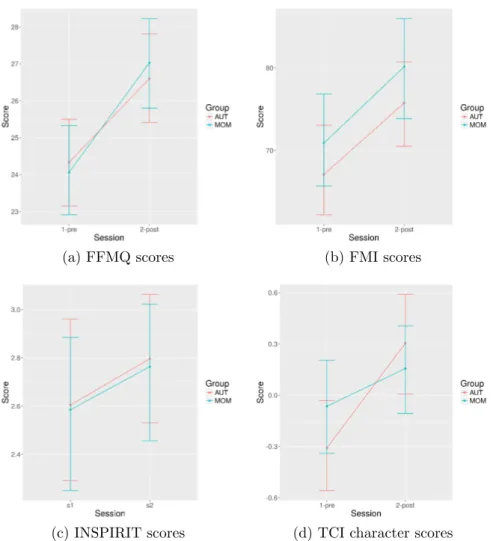

The purpose of this study was the comparison between a standard 8-week mindfulness meditation training and a training of the same length and with the same meditative technique, in which subjects did not receive the canon-ical weekly lessons and did not meditate in group. Outcomes were measured in terms of personality traits, spirituality and mindfulness abilities. For this last measure, in particular, four different instruments were used (FFMQ, FMI, CAMS-R, MAAS, all described in section 1.1.2) because of their focus on the mindfulness construct from different points of view, as explained in above-mentioned section.

The topic of mindfulness trainings delivered in the standard way vs. in solo settings recently gained importance in the area of self-help (Cavanagh et al., 2014) with various attempts of new trainings delivered very often via inter-net (Morledge et al., 2013). Early results for this kind of interventions (Spi-jkerman et al., 2016) suggested that they could bring positive effects in some domains for which standard trainings have proven to be effective, but the extent of overlap for these effects had not been clarified.

Other outcomes of interest in this study were also the adherence to practice, i.e. how much the persons practiced meditation during the 8 weeks of the trainings, and the dropout rate, i.e. how many subjects that started one of the trainings could not conclude it. Knowledge about these figures seemed to be important, because some data indicated that mindfulness interventions in solo setting (Allexandre et al., 2016) could lead to much greater dropout rates, for instance, than traditional interventions (Shapiro et al., 2005). Results of the experiment described here confirmed bigger dropout rate in the group which received the training in the solo setting, but the difference between the rates of the two groups did not reach statistical significance. Also regarding amount of practice the two groups did not differ, but in this measure the persons in the autonomous group meditated slightly more. The global information from these two data seemed to suggest that less persons completed the mindfulness meditation training in the solo setting, but those who resisted had a strong motivation for doing the practice autonomously. From the of the statistical analyses of the assessment instruments, an iden-tical pattern emerged almost everywhere: a significant main effect of session combined with a non significant effect of group and a non significant inter-action between session and group. This means that the mindfulness was effective in improving the qualities assessed, but that this improvement did not develop differently in the two groups. So, for measures of mindfulness

abilities, personality traits and level of spirituality, both groups showed an increase, and the degree of this increase was the same in the two groups. An only deviation from this pattern issued in the assessment of character traits of personality, where the autonomous group seemed to have a better improvement; however, this could be probably explained through a reactive mechanism (Bandura, 1991) in response of a baseline fragility in the self-directedness scale of character found only in the autonomous group.

(a) FFMQ scores (b) FMI scores

(c) INSPIRIT scores (d) TCI character scores

Figure 2.3: Results for a mindfulness training delivered in group (MOM) vs. solo setting (AUT), illustrated in terms of development of mindfulness abil-ities (FFMQ, FMI: higher score, greater ability), of spirituality (INSPIRIT: higher score, higher level), and of character traits (TCI: higher score, better condition)

2.3. MINDFULNESS AND NON-CONSCIOUS 19 The results of this research assert that, for the aspects investigated here, it was not possible to detect any difference between a training delivered in the standard way and a training in which participants just receive an intro-ductive lesson and participated in an only group meditation. This findings have certainly to be refined through confirmatory and additional research, but anyway open a question in the world of mindfulness meditation inter-ventions. At least these results suggest that it could be possible to deliver an effective autonomous training to persons, who have not the possibility to participate in a standard training.

Globally, this experiment showed that the positive outcomes of an 8-week mindfulness meditation training did not depend on the way it was carried out (in a standard way, with 8 weekly group meetings, vs. in an autonomous setting, with an only group meeting at the beginning of the training), but rather on the fact that the persons performed meditation, confirming pre-vious research (Campanella et al., 2014), which indicated that the practice of meditation correlates with improvements in mindfulness capabilities and with psychological benefits.

2.3

Mindfulness meditation in accessing

non-conscious

This published work (Fabbro et al., 2017) was prepared in response to a call for the topic of “Sub- and Unconscious Information Processing in the Hu-man Brain”. It is not clear what part of our memory and behavior is due to factors out of the reach of our consciousness (Bargh & Morsella, 2008; Augusto, 2010), but the extent of this part is such that some experiments have questioned the human possibility of exerting free will, in particular dur-ing action performance (Libet, 1999), an issue that has ancient philosophical roots (Kane, 1998) and critical consequences, that may extend from econ-omy (Nicholson, 1998) to politics (Druckman et al., 2011).

For the an investigation of this kind of material from a scientific point of view, all non-subjective measurements are certainly valid. But for a per-sonal enhancement of access to this material, few strategies seem to be avail-able: for example, hypnosis (Bargh, 2006), or analysis of dreams (Freud, 2013; Revonsuo, 1995), or language analysis (Billig, 2006), or free associa-tions method (Kris, 2013) allows another person to reveal us our unconscious sides. Our knowledge of them can be improved, without the need of an ex-ternal expert, through mindfulness meditation and the review described here tries to explain how.

It starts from the foundations of the different varieties of consciousness, that are probably the different systems of memory on which they rely (Tulv-ing, 1985), i.e. semantic, episodic and procedural: the first two are explicit systems, the last is implicit. If semantic memory works normally in an un-conscious way, which can emerge in awareness under certain conditions, pro-cedural memory is always hidden to awareness and it is linked to automatic responses. Finally, the episodic memory is connected to higher-order aware-ness (Rosenthal, 2012), the awareaware-ness of being conscious of a thought. Then the publication presents research that attempted to link mindfulness with the access to non-conscious parts of our memory. Literature reported is based both on mindfulness as a dispositional trait, owned naturally or as a result of mindfulness training, and on mindfulness as a transient state in-duced by a mindfulness practice. In these studies, the main instrument for the investigation of unconscious was the Implicit Association Test (Green-wald et al., 1998), which records how much a subject can link himself to a concept (e.g. spirituality, depression, esteem), rather than dissociating him-self from this concept. Other instruments of implicit assessment were the Remote Association Test (Mednick, 1962), the Alternating Serial Response Time Task (Howard Jr & Howard, 1997), a name-letter task (Nuttin, 1985), implicit and grammatical classification tasks, a trust game task, and an im-plicit photos evaluation task.

The studies which produced positive results in the attempt to link mindful-ness to access to unconscious, resumed in table 2.1, stated first of all that the development of mindfulness promoted greater concordance of the ex-plicitly and imex-plicitly measured self-attributes taken in the various studies. Lack of harmony at this two levels seems to be an decisive factor for lack of psychological well-being (e.g. Baumann et al., 2005). Other results con-nected mindfulness to various effects, all measured at an implicit level, such as reduced self-identification with depression, reduced bias toward some cat-egories of persons (blacks, homeless, different for age), or reduced automatic responses.

These results revealed the fact that mindfulness does not produce changes only at a explicit and phenomenological level, but that goes more in depth into personal structure. It is quite difficult to understand how and how much mindfulness can do this job, thing that could maybe done imaging the mem-ory structures implicated during mindfulness meditation. However, from the review described here suggested that this process of access was proven, re-inforcing the theories that link mindfulness to the improvement of a state that can be called self-knowledge (Carlson, 2013) or wisdom (Kabat-Zinn, 1990; Goldstein & Kornfield, 2001), which can guide persons in an adaptive auto-regulative evolution (Brown & Ryan, 2003).

2.3. MINDFULNESS AND NON-CONSCIOUS 21 Study N Meditation Mfn Explicit measure Instrumen t Implicit measure Instrumen t Result Bro wn&Ry an (2003)-study 3 90 -T trait mindfulness, affectiv e state MAAS, Diener&Emmons scale adapted affectiv e st ate IA T higher mindfulness predicted concordance b et w een implicit and explicit affectiv e exp erience Ko ole et al. (2009) 130 (st.1) 58 (st.2) MM (b o dy scan) S self-esteem RSES self-esteem name-letter task brief MM exercises increased asso ciation b et w een implicit and explicit self-esteem Keng et al. (2016) 79 MBCT adaptation S,T trait mindfulness, dysfunctional attitudes FFMQ,D AS-SF1 dysfunctional attitudes IA T “brief mindful acceptance training impro v ed implicit dysfunctional attitudes among individuals with high traitmindfulness” and promoted “greater self-concordance b et w een implicit and explicit dysfunctional attitudes” Crescen tini et al. (2014) 29 MM (breath, b o dy , though ts) T religiousness/ spiritualit y INSPIRIT religiousness/ spiritualit y IA T “MM training promoted congruen t in cr e a s es in implicit and explicit religiousness/ spiritualit y” Remmers et al. (2016) 72 MM S mo o d c hanges P ANAS mo o d c hanges IP ANA T “short MM exe r cise induced do wn-regulation of negativ e mo o d, on b oth explicit and im plicit lev els” Lev esque&Bro wn (2007)-study 2 78 -T trait mindfulness, da y-to-da y motiv atio n for b eha vior MAAS, adaptation of PLOC disp ositional autonom y IA T “mindfulness mo derated the effect of implicit motiv ational disp osition on da y-to-da y motiv ation for b eha vior” W aters et al. (2009) 158 -T trait mindfulness MAAS self-asso ciation to depression IA T “degree of mindfulness negativ ely asso ciated with implicit self-iden tificatio n with depression” Hutc herson et al. (2008) 93 LKM S ev aluat ions of photos (self, a close other, 3 neutral strangers) Lik ert scal e ev aluations of photos (self, a c lose other, 3 neutral strangers) affectiv e priming task brief LKM exercises caused higher explicit and implicit feelings of p ositivit y to w ard strangers, and c hanges in implicit p ositivit y to w ard the self Kang et al. (2013) 101 LKM T -bias to w ard blac ks and homeless IA T LKM training reduced implicit bias to w ard blac ks and homeless Stell&F arsides (2016) 69 LKM S -racial bias IA T short LKM exercises reduced implicit bia s on racial group targeted b y exercises Luek e&Gibson (2014) 72 MM (heartb eat, breath) S -age and racial bias IA T short MM practice decreased implicit race and age bia s Luek e&Gibson (2016) 93 MM (heartb eat, breath) S -racial discrimination mo dified T rust Game task short MM practice reduced discriminatory b eha vior Stric k et al. (2012) 63 (st.1) 34 (st.2) Zen S -unconscious activ ation of answ ers RA T (st.1), RA T + w ord priming (st.2) “20 min utes of meditation impro v e d access to the unconscious” Whitmarsh et al. (2013) 18 -T trait mindfulness FFMQ implicit learning implicit clas-sification task, grammatical clas-sification task “mindfulness reduced habitual resp onding to unconsciously acquired preferences” Stillman et al. (2014) 16 (st.1) 18 (st.2) -T trait mindfulness MAAS sequence learning task TL T (st.1), ASR T (st.2) “negativ e relationship b et w een mindfulness and implicit sequence learning” T able 2.1: Empirical studies of effects of mindfulness on implicit measures

Chapter 3

Mindfulness-Oriented

Meditation in a research with

EEG hyperscanning

3.1

Reasons for an experiment with MOM

and hyperscanning EEG

In exploring the neural correlates of meditation in general and of mindful-ness meditation in particular, scientists have exclusively studied individual brains (Cahn & Polich, 2006; Davis & Hayes, 2011). This is probably because concurrent consideration of more than one brain has to be connected with an hypothesis of interaction between them (Hari & Kujala, 2009) through the intermediary of the body, while meditation usually demands silence, im-mobility and voluntary blindness, in a better self-limitation of exteroceptive attention opposed to the idea of intercommunication between persons. However, we conducted an experiment collecting electroencephalographic (EEG) data with couples of persons meditating simultaneously in the same room or in different rooms. We suppose the possibility to find any difference between this two conditions, because when two individuals meditate together or they meditate alone, they know that they are doing the practice in com-pany or in loneliness. The fact that the subjects own this information could in theory change their performance. Examples that support this hypothesis extend from behavior changed by motivation, when performance improves if reinforcing cue is provided, to emotion driven by reading a novel, when the information got from a book can provoke in us joy rather than fear, or even to pain diminished by placebo effect (Zubieta & Stohler, 2009), when a same pill can produce different effects if it is presented as a candy or as

a medication. In meditation persons usually report that practicing together seems easier, an effect sometimes reported as due to the “sangha”: this word refers to “community” in Pali, probably the most relevant language for the literature inside Buddhism (Gombrich, 2009, p.vii), the original context of mindfulness meditation.

In order to address the issue object of this experiment, from a neural point of view it would be sufficient to measure brain activity of a single meditator while practicing in group or alone, and to repeat this measure in the same fashion for a proper number of subjects. The simplest form of this trial would be, of course, the analysis of this single meditator when in couple with an-other one and when alone, and this was the form chosen for our experiment. However, for the sake of uniformity of setting for the members of the couples and for taking advantage of data from the second meditator available in the study, both the members of the couple were simultaneously recorded with the same instrument in a technique named “hyperscanning” (Montague et al., 2002), described later in section 3.1.2. As control condition, subjects were asked also to engage in a mind-wandering task. For this kind of measure-ments, the use of EEG seemed quite appropriate because of its costs, of its low interfering construct, and of the extent of literature about it.

It is important to specify that during all the experiment each subject was not informed of the task requested to the other: the only information that each participant had, was the fact of being in a room recorded together with the other member of the couple, or alone in a room while the other one was recorded in the adjacent room.

Literature about mindfulness and intersubjectivity covers the interpersonal benefits that come from mindfulness and from its enhancement through medi-tation. As described in section 2.1.1, where a mindfulness training for persons with alcohol-dependence improved also character traits related to the per-sonal ability to relate with others (Crescentini et al., 2015), other studies pro-vided evidence for the link between mindfulness and empathy (Birnie et al., 2010), relatedness and interpersonal closeness (Brown & Ryan, 2004, 2003), ability to cope with relationship stress, satisfaction in relationships (Barnes et al., 2007), and awareness in social behavior (Dekeyser et al., 2008). How-ever, no attention seems to be focused on psychological mechanisms in action during the practice, apart from the publication about training in solo and individual setting (Mantzios & Giannou, 2014) and our research described in section 2.2.

The next sections, preceding the description of the experiment with hyper-scanning EEG, describe neuroscientific literature about meditation and the history of hyperscanning.

3.1. REASONS FOR MOM AND EEG HYPERSCANNING 25

3.1.1

Biology and physiology of meditation

Electrophysiology of meditation

The study of brain activity related to meditation with the use of EEG relies on many variables, that can define a certain experimental setting. First of all the meditative technique has to be considered, as it is well known (Thomas & Cohen, 2014) that the term “meditation” covers a broad range of prac-tices originating from different religious or spiritual traditions (Buddhism, In-duism, Islamism, Christianism) and adapted in many ways through the pass-ing of time in a lot of different contexts (clinical settpass-ings, religious cults): so different practices can focus on different objects (breath, body, mind, mantra, objects), can be performed in stillness or in motion, with eyes open or closed, in silence or uttering sounds/words. A second variable to be considered is the fact that meditation can produce both transient changes in experience (states) and lasting changes in the person (traits). A third variable in play is that these state or trait changes can be evaluated during the meditative practice or during a resting condition or during a task useful for assessing some performances. A forth variable to be considered is the experience of the subjects involved in the studies: various studies reported that effects on novices are different from effects on long-term meditators. A final variable that differentiates the experiments is also the number and the characteristics of the frequency bands used to report the results. For the mentioned number of variables, several experiments can be conceived and as a consequence their results will not be easily comparable.

The most important review on publications about meditation and EEG (Cahn & Polich, 2006) was written more than 10 years ago. Even if these review covers in detail all the literature starting from the 1950s (Das & Gastaut, 1955; Kasamatsu et al., 1957), the data reported lacks of the topographic precision that today’s hardware and software technology instead permits, in a degree such that it is possible to use the term “imaging” also for the results from EEG (Jung et al., 2001; Michel et al., 2004; Michel & Murray, 2012). The meditative techniques considered in the publications of the review widely varied outside the classification that was successively introduced regarding the role of the attention (Lutz et al., 2008b) during the practice of medita-tion. In the work of Cahn and Polich different forms of meditations were indeed distincted between “concentrative-based” and “mindfulness-based” practices. However, the review resuming statement reported that from all research on meditation it was possible to identify an overall slowing of brain activity, and also to assess the proficiency of the practice through the acti-vation in alpha (8-12 Hz) and theta (4-8 Hz) bands.

A later review on mindfulness meditation (Chiesa & Serretti, 2010) located the most coherent effects between studies again in alpha and theta bands, with significant increases in power during meditation. But the author of the older review warned in another publication (Cahn et al., 2010) that activ-ity in alpha band may be partly related other factors, as general arousal or experimental task order. In the same publication, a study carried on with long-term practitioners meditating according to the Vipassana technique, a significant increase in power of gamma (35-34 Hz) band at parieto-occipital sites was observed. In this band, which range is generally not precisely de-fined, research has developed later (Lehmann et al., 2001; Lutz et al., 2004) but now is possible up to 200Hz frequencies thanks to the advancements in technology.

If for meditation in general it is not possible (Thomas & Cohen, 2014; Bra-boszcz et al., 2017) to define precisely the basic neurophysiology of medita-tion, it is certainly useful, for the purpose of the experiment described in this chapter, to report the results of the EEG studies on meditation with focus on the breath. In an early study (Dunn et al., 1999) with 10 novice meditators, the practice of a concentrative technique with focus on the breath was com-pared with a mindfulness meditation and a relaxation condition. Differences were found between the two meditations at all bands; in particular the con-centrative technique produced lower frontal theta than mindfulness and this is quite strange because of the link between frontal theta and focused atten-tion. Another unusual finding comes from a study (Vialatte et al., 2009) with a yoga breathing technique, where, in addition to an increase in theta activ-ity, an epileptiform-like activity in gamma band (30-80 Hz) was observed in all 8 subjects. Four studies with Zen meditation addressed to the analysis of EEG activity during meditative breath techniques. In the first (Kubota et al., 2001) the authors found correlations between cardiac autonomic activity and frontal midline theta rhythm, which was induced by a Zen meditation pro-cedure consisting in breathing according to an external-paced rhythm and in counting the progressive number of breaths. This induction was possi-ble for 12 of the 25 participants and, in these subjects who showed frontal theta rhythm, this did not appear during all experimental trials. Other two studies (Takahashi et al., 2005; Murata et al., 2004) were carried on with the same meditation technique: the first reported frontal power increase in theta band, together with central increase in alpha and no difference in beta, while the second described no effect in theta and beta bands, but an increase in frontal alpha-band coherence. The forth study with Zen meditation (Yu et al., 2011), but with a different technique of focused attention on breathing movements in the lower abdomen, reported increases in power in alpha band and decreases in theta band, when comparing the activity before the

prac-3.1. REASONS FOR MOM AND EEG HYPERSCANNING 27 tice with the activity during the practice on central, parietal and occipital midline electrodes. A last research (Braboszcz & Delorme, 2011), related to EEG measurements of meditative breath techniques, studied 12 subjects that were asked, during a breath-counting task, to press a button when their attention had drifted away from the requested performance. The comparison between activity during the full-attentive performance and the activity dur-ing the performance in mind-wanderdur-ing showed that attentive performance was linked to decreases in delta and theta bands and increases in alpha and beta bands.

Resuming the effects found with EEG for meditative tasks involving breath, it is easy to say that there is few research on the topic and that it does not show uniform results. To the best of my knowledge there is not a study with EEG and anapanasati, the mindfulness of breathing, which has been employed in the research presented in this chapter.

Neurobiology of meditation

As in neurophysiology, also in neurobiology research on meditation is quite ample, but it is far distant from a complete understanding of the effects of meditation on the brains. The sources of difficulty in this are mainly those already described for neurophysiology.

Since the first study (Lazar et al., 2005) that assessed cortical thickness with magnetic functional resonance in long-term meditators and that proved cortical plasticity correlated with meditation practice, a lot of investigation followed with a pattern of results that resembles that found in neurophysi-ology: many different outcomes, with various confirmation of findings across different settings, together with some seemingly contradictory reports. A publication (Fox et al., 2014), that can help in summarize the most reported results about the structural differences brought by meditation, grouped to-gether five different meta-analyses and tried to individuate the most consis-tent findings across studies. The brain structures that seemed to be mostly transformed in meditators are:

• the left rostrolateral prefrontal cortex (e.g. McCaig et al., 2011), linked to elaboration of abstract data, to synthesis of different cognitive tasks, self-evaluation and metacognition;

• the anterior and mid-cingulate cortex (e.g. Grant et al., 2010), impli-cated in self-regulation;

• the anterior insula (e.g. Lazar et al., 2005; H¨olzel et al., 2007), related principally to interoceptive awareness;

• the primary and secondary somatomotor cortex (e.g. Grant et al., 2010; Fayed et al., 2013), from where all motor information to skeletal muscle groups is activated and where all information about tactile perception arrives;

• the left inferior temporal gyrus (e.g. H¨olzel et al., 2007; Leung et al., 2013), involved in visual processing;

• the hippocampus (e.g. Luders et al., 2013; H¨olzel et al., 2007), impor-tant in context-based emotional adaptation.

Neurophysiology of meditation

Also for neurophysiology of meditation, the same difficulties exposed in sec-tions about electrophysiology and neurobiology affected research, and for this the same patchy pattern of results emerged from it.

The reference review (Cahn & Polich, 2006) is the same presented for electro-physiology, with a thorough description of studies carried on with positron emission tomography (PET) and with functional magnetic resonance imag-ing (fMRI), with some reports also about studies with rheoencephalography (REG) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).

Review started from the first study with PET (Herzog et al., 1990), that re-ported an increased ratio of activity in frontal versus occipital regions, when comparing yoga meditators during practice and during resting condition. The first study with fMRI (Lazar et al., 2000) instead reported increases during a Kundalini meditation in activities of a bunch of regions with a role in at-tention and in control of the autonomic nervous system.

Interestingly the authors of the review included also two studies about Chris-tian prayer practices (Azari et al., 2001; Newberg et al., 2003), the first regarding the recitation of a Psalm and the second the focus of a phrase from the Bible. However, the conclusive report of all the studies considered, indicated that research was starting to demonstrate some consistency of lo-calization for meditation, with some greater hints in the activation of frontal and prefrontal areas.

A more recent review (Gotink et al., 2016) addressed the study of neurophys-iology of the standardized 8-week Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction pro-gram and the main claim of the publication was that the functional changes generated with this program in the prefrontal cortex, the cingulate cortex, the insula and the hippocampus, are comparable to the differences generally found when comparing long-term meditators with novices.

In a fMRI study with expert meditators engaged in a concentrative practice of mindfulness on breath and an open-monitoring practice (Manna et al., 2010),

3.1. REASONS FOR MOM AND EEG HYPERSCANNING 29 the activity during the focused attention meditation resulted profoundly dif-ferent from both the resting state activity and the other meditative practice. Activity during the breath FA meditation compared to rest showed increases in medial frontal areas, mainly in the right hemisphere, and decreases in the lateral prefrontal regions, mainly in the left hemisphere.

3.1.2

Hyperscanning

Inside social cognition, individual behaviors and brains in isolation have been predominantly studied. Situations of interest concerned single people im-mersed in a social context, but not involved in actual interactions with other persons. Experiments were designed in this way because it was assumed that social information processing was at the basis of all aspects of social inter-action (Frith & Frith, 2007). But, in recent years, interests have come to a turning point and have moved towards investigating real-time social inter-actions, focusing attention on their inter-personal dynamics. The reason for this turn is the possibility that, during interaction, organized coordination could emerge in form of autonomous engagement. With the introduction of hyperscanning, about a decade ago (Montague et al., 2002), social cognition started to investigate the neural underpinnings of what occurs in the course of the interactions between two or more persons. This technique consists in recording neural data from two or more people simultaneously and then using mathematical instruments to discover co-variations in the neural patterns. In this way, neuroscience is trying to uncover something that behavioral studies have already begun to reveal, that in the course of interactions between two persons, for example, they become a coupled unit (Konvalinka & Roepstorff, 2012) in a dynamic process of mutual adaptation.

This coordination during interaction has been described and quantified in terms of bodily movements, posture, physiological variables, and autonomic responses. For example, in an experiment (Richardson et al., 2007) pairs of people were sitting side by side in rocking chairs and were asked to move first in a coordinated way and then freely: results showed that both intentional and unintentional interpersonal coordination in the action of rocking is con-strained by the same dynamics of a coupled oscillator system. This event emerged independently of use of two chairs with same or different natural period. In another experiment (Shockley et al., 2003), members of a couple had to talk to each other or to other persons around them in order to solve a puzzle task: interpersonal coordination of posture during conversation was evaluated; results showed that the postures of the members of the couple were significantly more coordinated between them when they were talking to each other, compared with those in the intervals of time when they were