POLITECNICO DI MILANO

ArChITETTurA urbANIsTICA INgEgNErIA DELLE COsTruzIONI MAsTEr OF sCIENCE

ArChITECTurE AND urbAN DEsIgN MAsTEr ThEsIs

PrOF. ADALbErTO DEL bO AssT. LILAs AbDuLMAWLA

FIKRI UMUT YENER 895809 December 2019

AFTER WAR

RECONSTRUCTION

PROJECT IN

ALEPPO, SYRIA:

ThE CAsE OF

AL FArAFrA

NEIghbOrhOOD

‘Imagine all the people, living life in peace.’ John Lennon

ABSTRACT

The main idea of this thesis is to define the most destroyed areas and buildings in Al Farafra neighborhood, which is in the Old City of Aleppo, then to reconstruct new residential and public spaces. The approach way in the design process was to combine traditional architecture in Aleppo with Western modernism. The new urban texture zone consists housing, school, orphanage and library which are the most urgent necessities after the war situation because of the enormous destruction in Aleppo.

Keywords: Aleppo, after war reconstruction, architecture, urbanism, housing, school, orphanage.

ABSTRACT

Lo scopo principale di questa tesi è lo studio delle aree maggiormente distrutte dalla guerra, del quartiere di Al Farafra, la Citta Vecchia di Aleppo. L’idea è quella di progettare la ricostruzione di nuove aree residenziali e spazi pubblici all’interno di questo quartiere.

L’approccio utilizzato durante la progettazione, mira a combinare l’archittettura tradizionale di Aleppo con il Modernismo occidentale Il nuovo tessuto urbano prevedera’ abitazioni, scuole, orfanotrofi e biblioteche, spazi che sono necessari e urgenti dopo l’enorme distruzione portata dalla guerra.

Keywords: Aleppo, ricostruzione post – bellica , architettura, urbanistica, abitazioni, scuole, orfanotrofi.

CONTENTS

i Abstract

1 Introduction 9

2 History of Syria and Aleppo 10

2.1 Urban Evolution in Aleppo 14

3 Elements of Syrian Architecture 20

3.1 Urban Identity 21

3.2 Main housing Elements 22

4 Analyzing Aleppo 25

4.1 Elements of Architecture in Aleppo 27

4.2 Urban Changing in The Old City of Aleppo 30 4.3 Damages of War on Urban Texture in Aleppo 32 4.4 Damages of War on Architecture in Aleppo 36

5 The Project Proposal 47

INTRODUCTION

War destroys everything also with its surroundings. Societies, neighborhoods, architecture, urban identities and cultural heritages have been affected during every war. In this particular case which is Syria War, has many issues such as dead and injured people, demolished and damaged buildings, homeless people and many children have no home or family or school to go. People and families need residences, schools and many public places

This research’s objective is to analyze the damaged areas in the Old City of Aleppo, especially in the neighborhood called Al Farafra and to reconstruct destructed zones in this place with housing school, orphanage and library.

Housing typology identities mainly come from vernacular architecture elements from Syria, Aleppo such as courtyard, importance of privacy and limestone.

Orphanage and school are the key point to integrate children to society with education and to give social life.

Library and public places merge people and to keep them together after war.

HISTORY OF SYRIA AND ALEPPO

Syria is located on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea, surrounded on the north by Turkey, on the east by Iraq, on the south by Jordan and on the west by the Mediterranean Sea. The Syrian territory is subdivided into four geographical regions: the sea, the hills, the mountains and the desert areas and the administration of the city into 14 provinces divided into smaller local authorities. The remaining areas are desolated and rocky mountains; Syria has 6 million hectares of agricultural fields. Syria also played a major role in fostering many forms of social, artistic and economic trade between Asia and the Mediterranean civilizations.

2

The era of greatest political expansion began as the capital of the Amorite Kingdom of Yamhad at the beginning of the second millennium BCE when its status as the seat of the Storm God of Halab affirmed the importance of the region (UNITAR, 2018).

The people of Syria have evolved over a long time from several origins. In contrast with that of the Semitic tribes of Arabia and Mesopotamia, such as Arameans, Assyrians, Chaldeans and Canaanites, the Greek and Roman racial presence was negligible; later the Turks, like the Greeks and Romans before them, affected political and economic systems but failed to bring about any noticeable change in the prevailing Arab nature of the Syrian people (David Dean Commins, 2019).

Aleppo had already become an important commercial center during the Mamluk period, strategically positioned among eastern trade routes and the Mediterranean, Anatolian, and Arab countries (Ashtor, 1983).

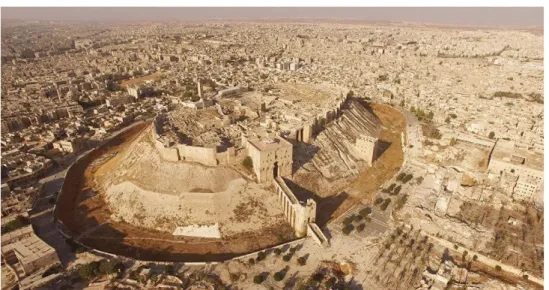

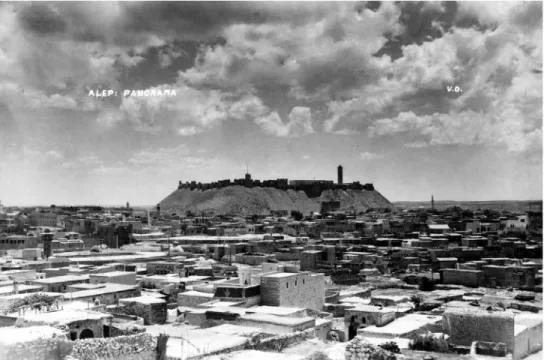

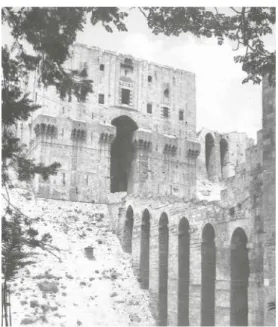

Fig 3: Aleppo and The Citadel. Photo was taken by Michel Écochard from 1930s. One of the most notable recent archeological discoveries in Syria is the ruins of the colossal temple dedicated to this god in the Citadel because it also recorded Aleppo’s history throughout the whole Aramean era to the early Syrian period for the first time, however Aleppo was devastated by the Hittites in the mid-sixteenth century bCE.

The exact date of Aleppo is uncertain, but it is considered to be one of the most ancient cities in the world. The first inhabitants were thought to have established homes on the hill in the middle of the modern city, taking advantage of the natural defensive advantages of the area, fertile land and the proximity of the Quwayq River water supply (Britannica, 2019). Aleppo is the second largest city in Syria after Damascus and it is situated approximately 30 mi (50 km) south of the Turkish border in the north-western part of the country.

The town benefited from the new market and secured the commercial routes provided by the integration into the Ottoman Empire (Kafesçioğlu, 1999). With its historical and rich history throughout all ages, Aleppo has become famous for its magnificent castle, town gates, the largest eastern souks, mosques, churches and schools and its longstanding traditional industries such as textiles, cotton ginning, laurel soap and olive oil and food industries. Internal trade grew as the inner city spread over an area including Diyarbekir and Mosul, while its status as a major center for the trade in caravans on international trade routes in the eastern Mediterranean area (Masters, 1988).

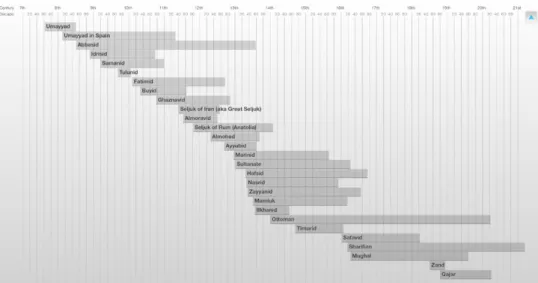

Fig 4: The Timeline of Aleppo history from Archnet.

Fig 6: Aleppo in Hellenistic Period

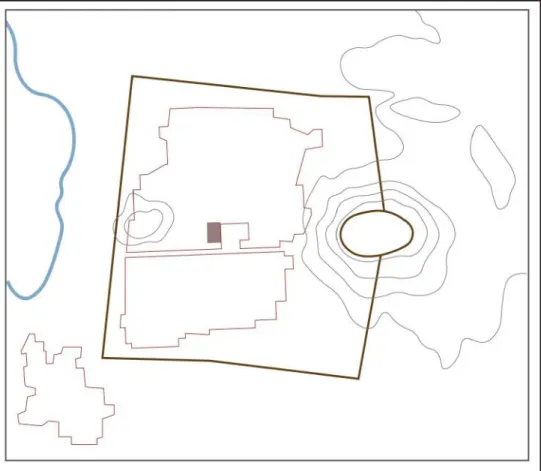

2.1 URBAN EvOLUTION IN ALEPPO

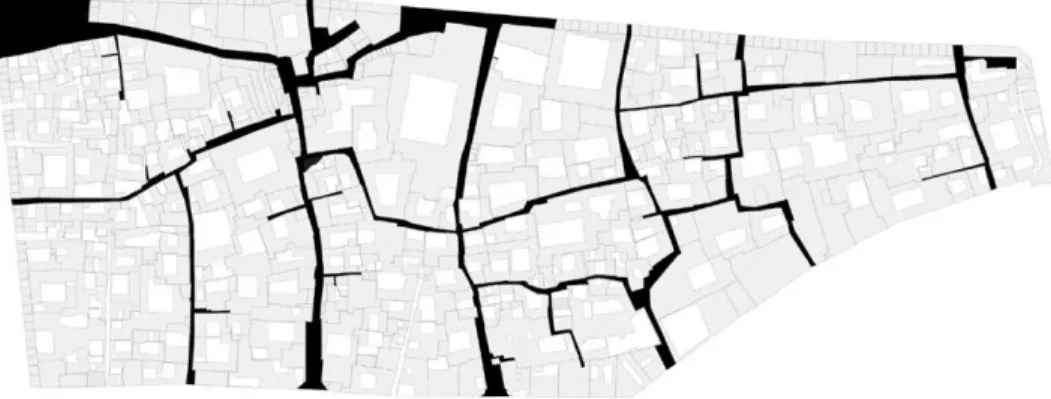

Since it was founded, Aleppo has been able to become an important center for business and production. The studies of reconstitution show that since the Hellenistic period in the 3rd century B.C the commercial center has retained its location. From the western gate of the city, to the Antioch Gate, on both sides of the main avenue, towards the Citadel. The location of the hellenistic agora, the Roman forum on the northern side of this avenue and later the Great Umayyad Mosque were at the center of the earliest markets (Kasmo, 2014).

Fig 7: Aleppo in Byzantine Period

In the age of Sultan Yavuz Selim in 1516, Aleppo was conquered by the Ottoman Empire. Aleppo’s ethnic groups have been different all over the past, as Aleppo has many different civilisations. The nationality of Aleppo was not changed, except for the Circassians until the second half of the 18th century, when Ottoman began governing Aleppo. In Western countries, Aleppo was an important hub. In particular because Halep’s harbor business was very active in Hijaz and Halep’s. These are understandable from Aleppo’s records ‘ English Consulate. Turkmen, Kurdish, Armenian, Circasian and Arabic had been confirmed by the English Consulate.

Fig 8: Aleppo in XI Century

The people of Syria have evolved over a long time from several origins In contrast with that of the Semitic tribes of Arabia and Mesopotamia, such as Arameans, Assyrians, Chaldeans and Canaanites, the Greek and Roman racial presence was negligible; later the Turks, like the Greeks and Romans before them, affected political and economic systems but failed to bring about any noticeable change in the prevailing Arab nature of the Syrian people (Britannica, 2019).

Fig 9: Aleppo in XIII Century

Aleppo’s position as a global commercial center was greatly boosted by geopolitical changes in the region in the 15th century. The need arose to set up a central commercial area that could provide market amenities, well-maintained khans, public baths and the protection of caravan merchants. As a result, large khans set up by the city’s governors and o cials in combination with retail markets were extended into the central market area. The khan was used for house traders, warehouses and large exchanges in these composites while the market was given over to retailers (Kasmo, 2014).

Fig 10: Aleppo in XIX Century

By the mid 18th century, structural improvements had begun in the existing shopping centre. The decline of international trade resulted in the loss of many of the hosting Khanes. Thus, local merchants and craftsmen used more routine commercial properties as offices, warehouses and workshops. Many modifications have been made to the original structures to suit the functions. From the beginning of the 20th century many beneficiaries of income and production began to leave the historic center in the modern centres, looking for better working conditions in the old part of town due to the low supply of the old town and the government’s shifting priorities towards the new districts (Kasmo, 2014).

Seven years pass, in a war that has impacted every part of the country’s life, Syrian homes, mosques and churches, archeological sites, and above all the Syrian people, have drowned. The conflict in Syria began in March 2011 and its origins emerged in Dara’a, South Syria with peaceful protests in March 2011 (Munawar, 2014).

ELEMENTS OF SYRIAN ARCHITECTURE

Courtyard architecture goes back to the early 3rd millennium before the common era when it originated in Bilad al-Sham buildings and in those between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in the area (Brian Edwards, 2006, s. 41-54). Generally, there are different inner courtyards in the traditional Arab house. The more luxurious the house, the more families there are. Some very large houses have 2 or 3 patios. We vary in terms of houses with a single courtyard, based on the economic status of their occupant; some houses have wide courtyards with a fountain in the centre, surrounded by trees, while others, smaller in size, have a plain courtyard (Levant, 2004).

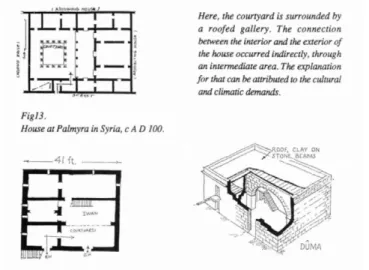

Fig 12: The courtyard principles in Syrian architecture.

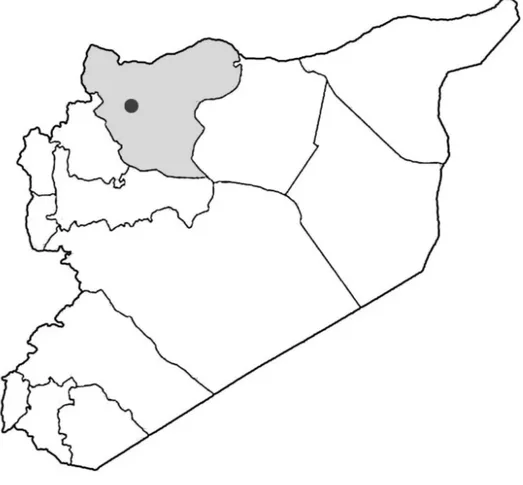

Fig 13: Aleppo governorate with Old City of Aleppo pointed with dark grey.

3.1 URBAN IDENTITY

In the Syrian architecture, buildings’ shapes are defined with land borders so that it gives to cities an organic and unique identity.

The standard house is generally based on traditional architectural designs in Aleppo: the courtyard rarely occupies 35 percent of the entire floor area and the upper floor rooms are added to the family’s needs or to be rented out to other immigrants.

As in older neighborhoods, these settlements have to be built into new urban structures by removing low houses and constructing four to five floors. The resulting speculation leads to an increase in land value and helps owners typically to make huge profits on poorly acquired property. Most workers ‘ districts near the center followed this type of development and now consist of 4-5 floors without interior courtyards or gardens and no street-like open space. Its densities are extremely high with a population of between 1000 and 1,200 per hectare and there is no commercial or service facility.

Traditionally accessible courtyard (Qa’a) allows for evaporative cooling with extensive planting. Vaulted, raised courtyard alcoves (Iwan) are often sealed with low-roofed living areas. High level balcony with open-air waiting rooms (Maq’ad) and courtyards works very well. Spaces are used in accordance with their diurnal and

Fig 15: Courtyard organisation

seasonal characteristics. The selection of material and the properties of envelope systems are extremely important for comfortable interiors, as most energy is conveyed through walls and roofs (Fathy, 1986).

The lower middle classes live in apartment buildings of better quality, most of them surrounded by a narrow garden. The use of space is also not adapted to the conventional ways of living in these more airy and cheerful districts: the inhabitants who come out of the old quarters must first become accustomed to the European house type which does not protect family privacy.

The Aleppo House’s constantly flat, stone-covered. The rooms are set around an interior courtyard on two or three or sometimes four sides. There are few street openings and the rooms are generally aligned with the inner courtyard on two levels. The courtyard is connected by an inner corridor to the entrance and has no galleries around it. It is always paved with flagstones and, when it allows the weather, it is the center of many domestic activities as a “turntable” to pass from one room to another.

Fig 16: Section of Syrian courtyard

Fig 19: Housing elements from Syrian architecture

During the summer spaces in the Northern Façade catch cool breezes but no direct sun light is received in winter. The windows to the north are always given a clearer distribution of light. Extremes of solar radiation are exposed to the Southern Facade. Features such as permanent arcades or feathered trees work extremely well in order to control the climate. Exposures to the East and West Faces should be checked and limited. Use should be selected appropriately in these spaces (Fathy, 1986).

Fig 20: The main entrance of Citadel in Aleppo

ANALYZING ALEPPO

In the world of Islam, there is many cities have historical past but Aleppo is one the most important one conceived from people. The reason behind that is, city’s texture and monuments conserved comparatively great. Therefore, one of the most outstanding trading and cultural capital in the Middle East is Aleppo, that also has fundamental buildings in Islamic history for instance the Citadel, bazaars, markets, many mosques, madrasahs, khans and souks (Stefano A. Bianca, 1980).

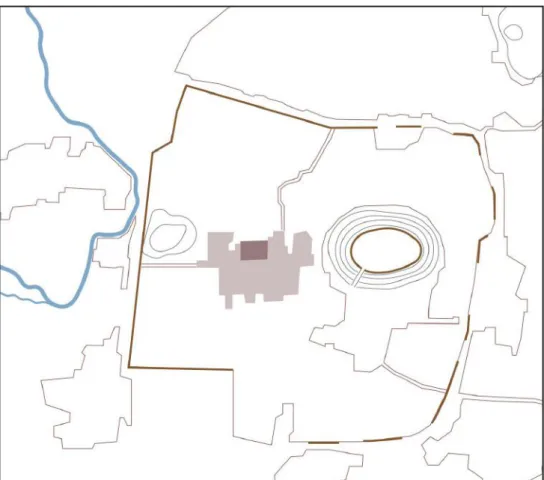

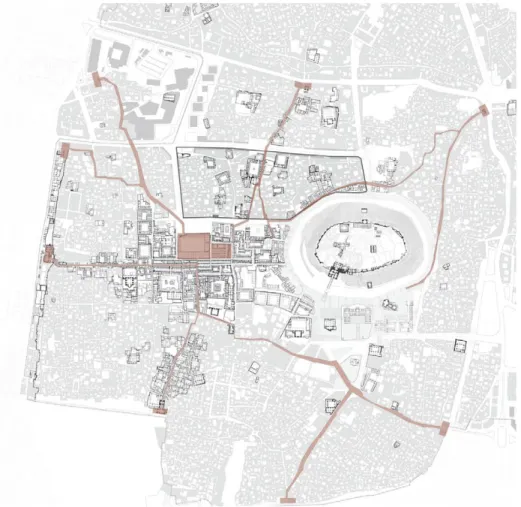

Fig 21: Al Farafra neighborhood in Old City of Aleppo

Social discrimination was very visible from the time of the eighteenth century in the neighborhood called Farafra expanded for numerous hectares, moreover a lot of aristocratic Muslim people were residents in the area (Stefano A. Bianca, 1980).

The architecture of Aleppo has many major elements that give the form almost for all traditional buildings and these features had been affected by Islamic and Syrian architecture. There are several main components for all type of buildings but also have many characteristics for housing typologies in Aleppo. Traditional houses have courtyards which is one of the most important thing for designing a house in Aleppo. Moreover, the main idea behind it is ‘earth beneath and sky above’ (Brian Edwards, 2006). The courtyard idea comes from Neolithic times and it came up the feeling of fear which is to defend from outside forces such as mankind and dangerous animals with to create a safer zone inside; with over times, the idea becomes more logical and controlled in urban texture and building itself to enlarge the constructible zone and regulate daylight, particularly in ample territories (Brian Edwards, 2006).

The courtyard is surrounded by the spaces of the house and most of them looks through the courtyard and get light from it furthermore, rooms have very small openings from the street side because of to keep privacy inside of the house. Accessibility from street to courtyard is mostly provided by a corridor to make privacy for households and especially for female residents. It’s very important for Muslim people.

Fig 22(left): The courtyard is surrounded by the rooms.

Fig 23(right): The house boundaries are determined by surrounding residences.

that have the privacy between male and female so that, it’s visible to see in traditional house design. In general, houses have two floors and to reach to the first floor is from the courtyard. Houses commonly made by limestone which is the main architectural element for Aleppo buildings and have terraced roof. In urban texture, houses have common walls and borders that are determined with surrounding residences.

The poorer houses are very plain, with one or two rooms on the ground floor serving many purposes and one room on the first floor often. No room is set aside permanently for cooking because kitchens were usually installed at the end of the 19th century. In the richer houses, room functions are better defined and differentiated; comfort standards are higher, with varied leisure and rooms are often divided between two or three patios; certain room styles occur, such as large-scale T-shaped reception rooms (qa’a) and iwans, while patios are adorned with fountains (salsabils), flowers, and marble marquetry (Stefano A. Bianca, 1980).

Fig 24(left): To show privacy from the street. Fig 25(right): Organization of opening through street.

Fig 27: Map of urban and building conditions at 1932 Source: IUSD Lab participants, Mapping: Neglia and team 2016

Fig 28: Map of urban and historic building at 2014

Source: IUSD Lab participants, Mapping: Neglia and team 2016

Fig 29: Map of main streets and the gates from the Ottoman City

Fig 30: Map of main streets and the gates from the Ottoman City

PErCENTAgE DAMAgE IN rEsIDENTIAL ArEA OF ALEPPO CITY

Fig 32: Percentage damage from UNITAR Maps

Fig 33: Laura Kurgan Interviewed by Noah Chasin in Bomb Magazine - http:// www.c4sr.net/news/laura-kurgan-interviewed-noah-chasin-bomb-magazine This map shows the percentage of damaged buildings in the city of Aleppo, Syrian Arab Republic, as determined by satellite imagery analysis. UNOSAT has identified a total of 33,521 damaged structures within the scope of this map using satellite images acquireed by 18 September 2016, 01 May 2015, 26 April 2015, 23 May 2014, 23 September 2013 and 21 November 2010. The total of buildings identified in a pre-conflict satellite painting collected in 2009 to determine the percentage of damaged buildings across the city are compared to these damaged constructions. Remember, in this study, only residential harm is considered and industrial areas are removed. This is a preliminary analysis and has not been checked on the surface. Please send the UNITAR – UNOSAT ground feedback.

Fig 34: Damage density from UNITAR Maps

In the city of Aleppo, Syrian Arab Republic, this map shows a number of damages observed from satellites. The pictures collected by satellites were analyzed on 18 September 2016, 01 May 2015 and 26 April 2015. UNITAR— Unosat has recorded, as of 18 September 2016, a total of 35,722, 4,773 of which have been lost, 14,680 severely damaged and 16,269 moderately damaged.

Fig:35 Blowing up the hotel,

Source: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/syria/10816231/ Syria-footage-emerges- of-Aleppo-Carlton-Hotel-bomb-blast.html

This corresponds, for the previous UNITAR UNOSAT analyzes conducted using images on 1 May 2015 and 26 April 2015, to an increase of approximately 154.5% in total damage. This analysis was carried out in the context of the REACH initiative in the United States. Global Disaster Assistance Department. The research is preliminary and has yet to be tested in the field. Please send the UNITAR – UNOSAT ground input.

Scholars regarded these protests as part of the revolutionary movement, which has erupted since 2010, known as the Arab Spring, in several states in Middle East and North Africa. The widespread public protests called for reform in the current regime, but the regime responded with the intelligence forces shooting and killing civilians. During protests, which eventually led to an armed conflict or, as the United Nations later stated, a civil war, there was a escalation of tensions and people in different parts of Syria joined (Glass, 2016).

4.4 DAMAGES ON ARCHITECTURE IN ALEPPO

Fig 36: Beit Ghazaleh before war situation.

Fig 38: Grand Serail of Aleppo before war situation.

Fig 41: Damaged buildings in Al FaraFra

Fig 41: Damaged buildings in Al FaraFra

THE PROJECT PROPOSAL

The main idea of the project is, to define the most damaged areas in the Old City affected from war and to design a new proposal with to respect traditional architecture of Aleppo. The neighborhood that have chosen is Al FaraFra, northwest side of Citadel, got damage more than other areas. Moreover, functions of the damaged buildings are generally housing and public properties such as school, orphanage and library exist in the zone. This is the reason of the design that focuses on housing. People need home! People need to stay!

In addition; a school, an orphanage and a library needed for this area to reintegrate people with education and cultural activities. Many children have no families after war therefore the reason to make an orphanage is to regain them into society with the help of school too.

64 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 TYPE A 1 FLOOR 74 M2 TYPE E 2 FLOORS 300 M2 TYPE C 1 FLOOR 51 M2 TYPE D 2 FLOORS 109 M2 TYPE B 2 FLOORS 2 FAMILIES FAMILY 1 89 M2 FAMILY 273 M2 GROUND FLOOR 1:100 GROUND FLOOR 1:100 FIRST FLOOR1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION BB 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION BB 1:100 TYPE D´ 2 FLOORS 109 M2 GROUND FLOOR 1:100 A A B A SECTION CC 1:100 B A A C B A A B B C B A A B B A B B A A A B A A B C C B A B ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 TYPE C' 1 FLOOR 51 M2 A A 8.00 15.00 8.00 .40 5.40 4.80 15.00 3.20 1.60 3.20 4.00 4.00 8.00 4.60 5.40 5.00 15.00 8.00 3.20 1.60 3.20 8.00 4.80 5.20 5.00 15.00 2.46 3.94 1.60 5.01 5.20 4.80 15.00 8.00 3.20 1.60 3.70 8.50 4.00 4.20 1.20 3.20 4.10 8.50 5.40 2.80 8.20 5.00 4.40 9.40 8.50 4.35 4.15 1.20 8.20 9.40 3.70 1.60 3.20 8.50 4.40 4.10 8.50 3.90 1.60 3.90 3.70 1.60 3.20 8.50 5.00 4.40 9.40 9.40 1.20 4.00 9.40 4.20 3.20 1.60 3.70 8.50 2.80 6.60 9.40 4.10 4.40 8.50 5.00 9.40 4.40 4.40 4.10 8.50 3.90 1.60 3.90 9.40 3.70 1.60 3.20 8.50 1.33 2.47 6.70 1.50 12.00 6.30 3.77 3.7724.29 3.77 6.69 6.00 6.00 12.00 12.35 5.65 6.30 24.29 12.00 11.30 6.69 24.29 4.53 1.47 1.48 4.52 12.00 6.69 11.30 6.30 24.29 5.61 SECTION BB 1:100 B B 4.80 4.80 1.70 2.70 .40 4.50 2.10 .40 1.40 4.00 2.85 6.35 15.00 .40 5.20 1.00 .40 4.00 4.00 5.40 1.00 1.00 .40 1.60 2.30 .40 2.60 5.20 4.10 8.50 8.20 8.20 .40 4.45 3.65 8.50 B B 4.10 1.00 3.55 A A B B B A A B 6.30 6.90 .40 4.70 GROUND FLOOR 1:100 GROUND FLOOR 1:100 GROUND FLOOR 1:100 GROUND FLOOR 1:100 FIRST FLOOR 1:100 FIRST FLOOR 1:100 FIRST FLOOR 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION BB 1:100 SECTION BB 1:100 SECTION BB 1:100 SECTION BB 1:100 HOUSING TYPOLOGIES FIKRI UMUT YENER / 895809 Politecnico di Milano / Architettura Urbanistica Ingegneria delle Costruzioni / MSc Architecture and Urban Design / Master Thesis / Prof. A. Del Bo / Asst. Lilas Abdulmawla / 7

65 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 TYPE A 1 FLOOR 74 M2 TYPE E 2 FLOORS 300 M2 TYPE C 1 FLOOR 51 M2 TYPE D 2 FLOORS 109 M2 TYPE B 2 FLOORS 2 FAMILIES FAMILY 1 89 M2 FAMILY 273 M2 GROUND FLOOR 1:100 GROUND FLOOR 1:100 FIRST FLOOR1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION BB 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION BB 1:100 TYPE D´ 2 FLOORS 109 M2 GROUND FLOOR 1:100 A A B A SECTION CC 1:100 B A A C B A A B B C B A A B B A B B A A A B A A B C C B A B ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 TYPE C' 1 FLOOR 51 M2 A A 8.00 15.00 8.00 .40 5.40 4.80 15.00 3.20 1.60 3.20 4.00 4.00 8.00 4.60 5.40 5.00 15.00 8.00 3.20 1.60 3.20 8.00 4.80 5.20 5.00 15.00 2.46 3.94 1.60 5.01 5.20 4.80 15.00 8.00 3.20 1.60 3.70 8.50 4.00 4.20 1.20 3.20 4.10 8.50 5.40 2.80 8.20 5.00 4.40 9.40 8.50 4.35 4.15 1.20 8.20 9.40 3.70 1.60 3.20 8.50 4.40 4.10 8.50 3.90 1.60 3.90 3.70 1.60 3.20 8.50 5.00 4.40 9.40 9.40 1.20 4.00 9.40 4.20 3.20 1.60 3.70 8.50 2.80 6.60 9.40 4.10 4.40 8.50 5.00 9.40 4.40 4.40 4.10 8.50 3.90 1.60 3.90 9.40 3.70 1.60 3.20 8.50 1.33 2.47 6.70 1.50 12.00 6.30 3.77 3.7724.29 3.77 6.69 6.00 6.00 12.00 12.35 5.65 6.30 24.29 12.00 11.30 6.69 24.29 4.53 1.47 1.48 4.52 12.00 6.69 11.30 6.30 24.29 5.61 SECTION BB 1:100 B B 4.80 4.80 1.70 2.70 .40 4.50 2.10 .40 1.40 4.00 2.85 6.35 15.00 .40 5.20 1.00 .40 4.00 4.00 5.40 1.00 1.00 .40 1.60 2.30 .40 2.60 5.20 4.10 8.50 8.20 8.20 .40 4.45 3.65 8.50 B B 4.10 1.00 3.55 A A B B B A A B 6.30 6.90 .40 4.70 GROUND FLOOR 1:100 GROUND FLOOR 1:100 GROUND FLOOR 1:100 GROUND FLOOR 1:100 FIRST FLOOR 1:100 FIRST FLOOR 1:100 FIRST FLOOR 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION BB 1:100 SECTION BB 1:100 SECTION BB 1:100 SECTION BB 1:100 HOUSING TYPOLOGIES FIKRI UMUT YENER / 895809 Politecnico di Milano / Architettura Urbanistica Ingegneria delle Costruzioni / MSc Architecture and Urban Design / Master Thesis / Prof. A. Del Bo / Asst. Lilas Abdulmawla / 7

66

A

B

GROUND FLOOR PLAN 1:100

A B

A B

FIRST FLOOR PLAN 1:100 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 A B F1 F1 F2 F2 F1 F1 F2 F2 HOUSING - H1 HOUSING PLANS

67

A

B

GROUND FLOOR PLAN 1:100

A B

A B

FIRST FLOOR PLAN 1:100 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 A B F1 F1 F2 F2 F1 F1 F2 F2 HOUSING - H1 HOUSING PLANS

68

GROUND FLOOR PLAN 1:100 B B A A F2 F2 F1 F1 HOUSING - H2 HOUSING PLANS FIKRI UMUT YENER / 895809 Politecnico di Milano / Architettura Urbanistica Ingegneria delle Costruzioni / MSc Architecture and Urban Design / Master Thesis / Prof. A. Del Bo / Asst. Lilas Abdulmawla / 9

69

GROUND FLOOR PLAN 1:100 B B A A F2 F2 F1 F1 HOUSING - H2 HOUSING PLANS FIKRI UMUT YENER / 895809 Politecnico di Milano / Architettura Urbanistica Ingegneria delle Costruzioni / MSc Architecture and Urban Design / Master Thesis / Prof. A. Del Bo / Asst. Lilas Abdulmawla / 9

± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 FIRST FLOOR PLAN

1:100 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 HOUSING - H2 B B A A F2 F2 F1 F1 HOUSING PLANS

± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 FIRST FLOOR PLAN

1:100 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 HOUSING - H2 B B A A F2 F2 F1 F1 HOUSING PLANS

72 B C C A B A F1 F2 F1 F2 6

GROUND FLOOR PLAN 1:100

HOUSING - H3

HOUSING PLANS FIKRI UMUT YENER / 895809 Politecnico di Milano / Architettura Urbanistica Ingegneria delle Costruzioni / MSc Architecture and Urban Design / Master Thesis / Prof. A. Del Bo / Asst. Lilas Abdulmawla / 11

73 B C C A B A F1 F2 F1 F2 6

GROUND FLOOR PLAN 1:100

HOUSING - H3

HOUSING PLANS FIKRI UMUT YENER / 895809 Politecnico di Milano / Architettura Urbanistica Ingegneria delle Costruzioni / MSc Architecture and Urban Design / Master Thesis / Prof. A. Del Bo / Asst. Lilas Abdulmawla / 11

± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 6 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20

FIRST FLOOR PLAN 1:100 HOUSING - H3 B C C A B A F1 F2 F1 F2 ± 0.00 + 3.20 HOUSING PLANS FIKRI UMUT YENER / 895809 Politecnico di Milano / Architettura Urbanistica Ingegneria delle Costruzioni / MSc Architecture and Urban Design / Master Thesis / Prof. A. Del Bo / Asst. Lilas Abdulmawla / 12

± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 + 3.20 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 6 ± 0.00 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20

FIRST FLOOR PLAN 1:100 HOUSING - H3 B C C A B A F1 F2 F1 F2 ± 0.00 + 3.20 HOUSING PLANS FIKRI UMUT YENER / 895809 Politecnico di Milano / Architettura Urbanistica Ingegneria delle Costruzioni / MSc Architecture and Urban Design / Master Thesis / Prof. A. Del Bo / Asst. Lilas Abdulmawla / 12

76 SECTION BB 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 FACADE F2 1:100 FACADE F1 1:100

STONE WALL COVERING 3x9x15cm CEMENT PLASTER / 1cm GEOTEXTILE MAT / 1cm THERMAL INSULATION XPS / 5cm GAS CONCRETE / 19x13cm THERMAL INSULATION XPS / 5cm WALL PLASTER / 1cm WALL PAINTING / 1cm FACADE F1 1:100 FACADE F2 1:100 HOUSING - H1

HOUSING - H2 WALL DETAIL

1/10

HOUSING SECTIONS AND FACADES FIKRI UMUT YENER / 895809 Politecnico di Milano / Architettura Urbanistica Ingegneria delle Costruzioni / MSc Architecture and Urban Design / Master Thesis / Prof. A. Del Bo / Asst. Lilas Abdulmawla / 13

77 SECTION BB 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 FACADE F2 1:100 FACADE F1 1:100

STONE WALL COVERING 3x9x15cm CEMENT PLASTER / 1cm GEOTEXTILE MAT / 1cm THERMAL INSULATION XPS / 5cm GAS CONCRETE / 19x13cm THERMAL INSULATION XPS / 5cm WALL PLASTER / 1cm WALL PAINTING / 1cm FACADE F1 1:100 FACADE F2 1:100 HOUSING - H1

HOUSING - H2 WALL DETAIL

1/10

HOUSING SECTIONS AND FACADES FIKRI UMUT YENER / 895809 Politecnico di Milano / Architettura Urbanistica Ingegneria delle Costruzioni / MSc Architecture and Urban Design / Master Thesis / Prof. A. Del Bo / Asst. Lilas Abdulmawla / 13

78 FACADE F1 1:100 FACADE F2 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION BB 1:100 SECTION CC 1:100 HOUSING - H3 HOUSING - H2 SECTION BB 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100

HOUSING SECTIONS AND FACADES

79 FACADE F1 1:100 FACADE F2 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100 SECTION BB 1:100 SECTION CC 1:100 HOUSING - H3 HOUSING - H2 SECTION BB 1:100 SECTION AA 1:100

HOUSING SECTIONS AND FACADES

88 8 7 5 4 7 11 10 8 6 2 1 3 2 2 1 1 1 5 C C E B D A F F E B D A

SCHOOL,ORPHANAGE AND LIBRARY GROUND FLOOR PLAN

SECTION AA

SECTION BB

SECTION CC

FIKRI UMUT YENER / 895809 Politecnico di Milano / Architettura Urbanistica Ingegneria delle Costruzioni / MSc Architecture and Urban Design / Master Thesis / Prof. A. Del Bo / Asst. Lilas Abdulmawla / 1 - DORM ROOM 2 - STUDY ROOM 3 - COURTYARD 4 - FITNESS 5 - ADMINISTRATION 6 - KITCHEN 7 - CAFETERIA 8 - CAFE 9 - LIBRARY 10 - TEACHER'S ROOMS 11 - LOUNGE 12 - TV ROOM 13 - DINING ROOM 14 - STUDY HALL 15 - MUSIC ROOM 16 - LABORATORY FUNCTIONS 16

89 8 7 5 4 7 11 10 8 6 2 1 3 2 2 1 1 1 5 C C E B D A F F E B D A

SCHOOL,ORPHANAGE AND LIBRARY GROUND FLOOR PLAN

SECTION AA

SECTION BB

SECTION CC

FIKRI UMUT YENER / 895809 Politecnico di Milano / Architettura Urbanistica Ingegneria delle Costruzioni / MSc Architecture and Urban Design / Master Thesis / Prof. A. Del Bo / Asst. Lilas Abdulmawla / 1 - DORM ROOM 2 - STUDY ROOM 3 - COURTYARD 4 - FITNESS 5 - ADMINISTRATION 6 - KITCHEN 7 - CAFETERIA 8 - CAFE 9 - LIBRARY 10 - TEACHER'S ROOMS 11 - LOUNGE 12 - TV ROOM 13 - DINING ROOM 14 - STUDY HALL 15 - MUSIC ROOM 16 - LABORATORY FUNCTIONS 16

90 14 13 5 12 8 10 6 2 1 2 2 1 1 1 9 15 16 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 C 9 C E B B D D A A F F E 1 - DORM ROOM 2 - STUDY ROOM 3 - COURTYARD 4 - FITNESS 5 - ADMINISTRATION 6 - KITCHEN 7 - CAFETERIA 8 - CAFE 9 - LIBRARY 10 - TEACHER'S ROOMS 11 - LOUNGE 12 - TV ROOM 13 - DINING ROOM 14 - STUDY HALL 15 - MUSIC ROOM 16 - LABORATORY FUNCTIONS

SCHOOL,ORPHANAGE AND LIBRARY FIRST FLOOR PLAN

SECTION DD

SECTION EE

SECTION FF

91 14 13 5 12 8 10 6 2 1 2 2 1 1 1 9 15 16 ± 0.00 + 3.20 ± 0.00 + 3.20 C 9 C E B B D D A A F F E 1 - DORM ROOM 2 - STUDY ROOM 3 - COURTYARD 4 - FITNESS 5 - ADMINISTRATION 6 - KITCHEN 7 - CAFETERIA 8 - CAFE 9 - LIBRARY 10 - TEACHER'S ROOMS 11 - LOUNGE 12 - TV ROOM 13 - DINING ROOM 14 - STUDY HALL 15 - MUSIC ROOM 16 - LABORATORY FUNCTIONS

SCHOOL,ORPHANAGE AND LIBRARY FIRST FLOOR PLAN

SECTION DD

SECTION EE

SECTION FF

IMAGINE

Imagine there’s no countries It isn’t hard to do Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion, too Imagine all the people

Living life in peace You may say I’m a dreamer

But I’m not the only one I hope someday you will join us

And the world will be as one Imagine no possessions

I wonder if you can No need for greed or hunger

A brotherhood of man Imagine all the people Sharing all the world You may say I’m a dreamer

But I’m not the only one I hope someday you will join us

And the world will live as one

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Akköz, H. (2017, April). An Evaluation on the ethnic Structure of

Aleppo Vilayet in The nineteenth Century. Journal of History and Future, 256-271.

Ashtor, E. (1983). Levant Trade in the Later Middle Ages. Princeton:

Princeton University.

Brian Edwards, M. S. (2006). Courtyard Housing: Past, Present and

Future. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Britannica, T. E. (2019, 10 7). Aleppo. (Encyclopædia Britannica, inc.)

Retrieved from Encyclopædia Britannica: https://www.britannica. com/place/Aleppo

David Dean Commins, H. H. (2019, 7 15). Syria. (Encyclopædia

Britannica, inc.) Retrieved from Encyclopædia Britannica: https:// www.britannica.com/place/Syria

Fathy, H. (1986). Natural Energy and Vernacular Architecture:

Principles and Examples with Reference to Hot Arid climates. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Glass, C. (2016). Syria Burning: A Short History of a Catastrophe.

London: Verso Books.

Kafesçioğlu, Ç. (1999). In the Image of Rum: Ottoman Architectural

Patronage in Sixteenth Century Aleppo and Damascus. In Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World, XVI, 70-96.

Kasmo, R. (2014). The Historic Commercial Center of the Old City

of Aleppo, lessons from the pre-conflict conservation efforts. AS – Architecture and Science, 40-53.

Levant, C. (2004). Traditional Syrian Architecture. Avignon, France:

Ecole d’Avignon.

Masters, B. (1988). The Origins of Western Economic Dominance in

the Middle East. New York: New York University Press.

Munawar, N. A. (2014). Rebuilding Aleppo: Public Engagement in

Post-Conflict Reconstruction. ICOMOS University Forum Workshop on Authenticity and Reconstructions: A contemporary provocation: reconstructions as tools of future-making. Paris: ICOMOS.

Stefano A. Bianca, J.-C. D.-Y. (1980). The Conservation of the Old

City of Aleppo. Paris: UNESCO.

UNITAR. (2018). FIVE YEARS OF CONFLICT : The State of Cultural

Fikri Umut Yener