Table of Contents i

1 Introduction 1

2 Motion and Reference Systems 7

1 Introduction . . . 7

1.1 From Generative Grammar to Generative Semantics and Cognition . 10 1.1.1 A Cognitive Model for Semantics . . . 10

1.1.2 Lexicalisation Process for the Verbs of Motion . . . 13

1.2 Motion and Frame Semantics: a Knowledge Representation Language 15 1.2.1 The FrameNet Project . . . 17

1.3 Space and Cognition . . . 18

2 Motion Events . . . 22

2.1 Figure and Ground . . . 22

2.1.1 Path . . . 25

2.1.2 Co-events and Manner . . . 25

2.1.3 Lexicalisation Patterns . . . 26

2.1.4 Lexicalisation Patterns as Typological Classification . . . . 29

3 From Motion to Frame of Reference . . . 33

3.1 Localisation Strategies . . . 34

3.1.1 Environmental and Anthropocentric References . . . 35

3.2 Vertical and Horizontal Dimensions . . . 35

3.3 Object-centred and Environment-centred Frames of Reference . . . . 36

3.4 Angular Dimensions . . . 40

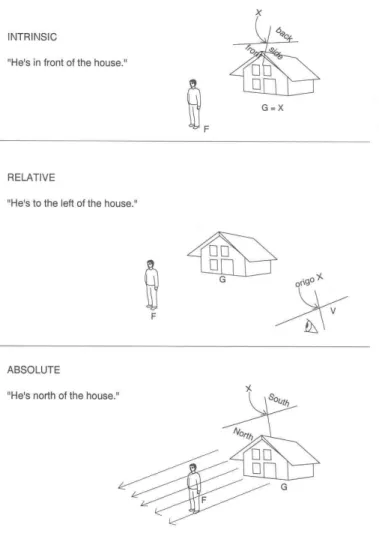

3.5 Three Frames of Reference . . . 42

3.5.1 Intrinsic Frame of Reference . . . 47

3.5.2 Relative Frame of Reference . . . 48

3.5.3 Absolute Frame of Reference . . . 48

2 Questions and Sub-questions . . . 53

3 Theoretical clarifications . . . 54

3.1 Verb-framed and Satellite-framed in Italian . . . 54

3.2 Conflation and Satellites: Redundant Constructions . . . 56

3.2.1 The Italian Phrasal Verbs . . . 57

3.2.2 Satellites and Prepositions in Italian . . . 59

3.3 Arguments and Adjuncts . . . 63

4 Complex Events . . . 66

5 Orientation and Directions . . . 67

6 Specification of Entities . . . 68

6.1 Source and Goal . . . 69

6.2 Direction . . . 70

6.3 Proximal Trajectory . . . 71

6.4 Shape of the Trajectory . . . 71

6.5 Distance . . . 72

6.6 Manner . . . 72

7 Objectives and Methodology . . . 73

4 The Corpus 75 1 Introduction . . . 75

2 Spoken Language and Dialogue . . . 76

2.1 Spoken vs Written Language . . . . 76

2.2 The Dialogue . . . 77

2.3 Spoken Italian Corpora . . . 78

3 Corpora used in this Research . . . 79

3.1 Map Task Dialogues . . . 80

3.2 Route Descriptions . . . 83

4 Processing of the Corpus . . . 84

5 Some Caveats . . . . 87

5 Qualitative Analysis: Categories in the Corpus 89 1 Introduction . . . 89

2 Lexico-syntactic Schemata . . . 92

2.1 Source/Goal Vector . . . 92

2.2 Expressions of Path . . . 97

2.3 Absolute directions . . . 99

2.4 Direction with respect to a Ground . . . 102

2.9 Manner of Motion . . . 113

2.10 Further Specifications . . . 113

2.11 Conflation: Specific vs Generic Verbs . . . 115

3 The Semantic Dimension. Clusters of Meaning . . . 116

3.1 Source/Goal Trajectories . . . 118 3.1.1 Generic motion . . . 118 3.1.2 Ending Trajectories . . . 119 3.1.3 Starting Trajectories . . . 121 3.1.4 Continuing Trajectories . . . 121 3.2 Path Cluster . . . 122 3.2.1 Crossing Trajectories . . . 122 3.2.2 Through Trajectories . . . 122 3.2.3 Inwards Trajectories . . . 123 3.2.4 Outwards Trajectories . . . 124 3.3 Direction Cluster . . . 125

3.3.1 Deviation from an Original Trajectory . . . 125

3.3.2 Generic Directions . . . 127

3.4 Shape Cluster . . . 129

3.4.1 Plain Circular Movement . . . 129

3.4.2 Curvilinear Trajectories . . . 131

3.4.3 Straight Line Trajectory . . . 133

3.4.4 Special Trajectories . . . 134

3.5 Proximal Trajectory . . . 135

3.6 Other Motion Verbs . . . 137

4 Crossing Categories . . . 138

6 Quantitative Analysis: Distributional Categories 139 1 Introduction . . . 139

2 Profile of the Corpus . . . 140

2.1 Domain-Dependence . . . 141

2.2 Differences between the two Sub-Corpora . . . 142

3 Richness of Vocabulary and Diatopic Variation . . . 148

4 Distribution of the Motion Events . . . 154

4.1 Trajectory in terms of Source and Goal . . . 156

4.1.1 General Verbs . . . 156

4.1.2 Ending Trajectories . . . 157

4.2 Trajectories in terms of Path . . . 159

4.2.5 Other Path Trajectories . . . 162

4.3 Trajectories in terms of Shape . . . 162

4.3.1 Circular Trajectories . . . 163

4.3.2 Curvilinear Trajectories . . . 164

4.3.3 Straight Line Trajectory . . . 166

4.4 Trajectories in terms of Direction . . . 167

4.4.1 Deviation from an Original Trajectory . . . 167

4.4.2 Generic Directions . . . 168

4.5 Proximal Trajectories . . . 170

4.6 Generic Motion Verbs . . . 172

5 Generalisations . . . 173

5.1 Behaviours of the Verbs . . . 173

5.2 The Clusters . . . 176 5.2.1 Source/Goal . . . 177 5.2.2 Path Cluster . . . 178 5.2.3 Direction Cluster . . . 178 5.2.4 Shape Cluster . . . 179 5.2.5 Proximity . . . 180 5.3 Overall Distribution . . . 180

6 Distribution of Frame of Reference . . . 182

7 Conclusions 187

Bibliography 195

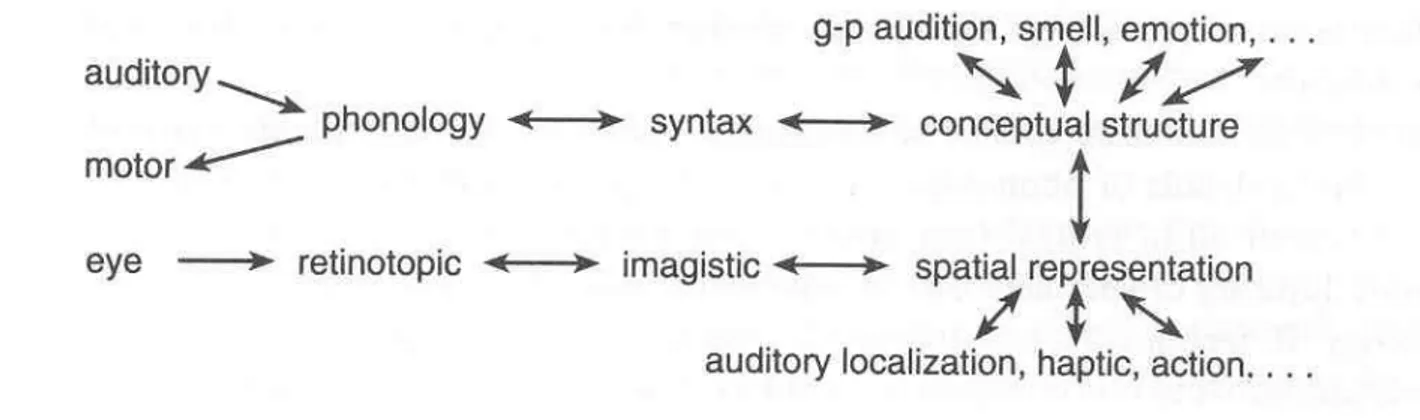

2.1 Language and vision . . . 11

2.2 Example (2)d, not incorporating verb . . . 15

2.3 Example (3)c, incorporating verb . . . 16

2.4 Preposition with and across . . . . 19

2.5 Preposition above and below . . . . 20

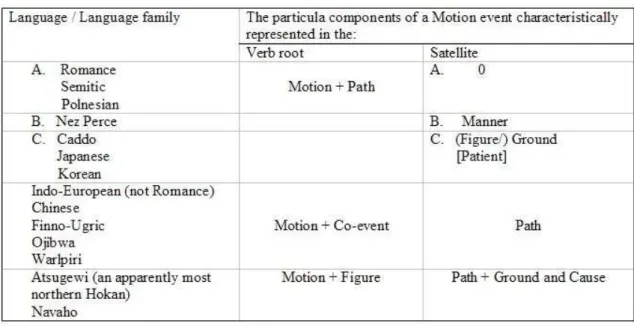

2.6 Conflation of the type MOVE+Path . . . 28

2.7 MOVE+Figure . . . 29

2.8 Classification of languages according to the lexicalisation patterns 31 2.9 Intrinsic reference frame . . . 37

2.10 Environmental reference frame . . . 38

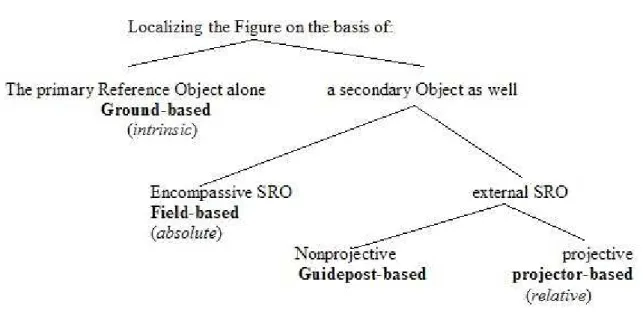

2.11 Localising the Figure . . . 40

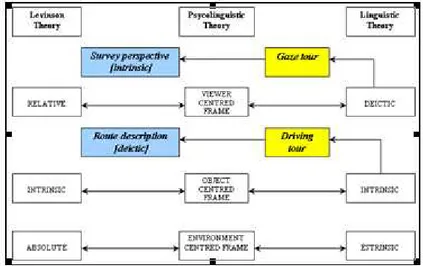

2.12 Comparison between Levelt and Tversky . . . 42

2.13 Major semantics subfields in special languages . . . 44

2.14 Canonical example of the three frame of reference . . . 45

3.1 Motion to Ground . . . 69

3.2 Motion from Ground . . . 69

3.3 Motion direction Ground . . . 71

3.4 Motion direction . . . 71

3.5 Double direction . . . 72

4.1 Map of giver . . . 81

4.2 Map of follower . . . 82

5.2 Schema A - case 1 . . . 92

5.3 Schema A – case 2 . . . 93

5.4 Schema A – case 2, instance 3 . . . 95

5.5 schema a case 3 . . . 97 5.6 Schema B – case 1 . . . 98 5.7 Schema B – case 2 . . . 99 5.8 Schema C – case 1 . . . 100 5.9 Schema C – case 2 . . . 101 5.10 Schema D – case 1 . . . 103 5.11 Schema D – case 2 . . . 103 5.12 Schema E – case 1 . . . 104 5.13 Schema E – case 2 . . . 106 5.14 Schema E – case 3 . . . 107 5.15 Schema F – case 1 . . . 108 5.16 schema F – case 2 . . . 108 5.17 Schema F - case 3 . . . 109 5.18 Schema G - case 1 . . . 110 5.19 Schema G - case 2 . . . 110 5.20 Schema H - case 1 . . . 111 5.21 Schema H - case 2 . . . 112 5.22 Schema I . . . 114

6.1 List of the motion verbs shared by all the corpora . . . 142

6.2 Absolute and relative frequencies in the four Map Task samples -part I . . . 143

6.3 Absolute and relative frequencies in the four Map Task samples -part II . . . 144

6.4 Absolute and relative frequencies in the four Map Task samples -part III . . . 145

6.6 Absolute and relative frequencies in tho four Route Description

samples - part II . . . 147

6.7 Average frequency and standard deviation in the two samples town by town . . . 149

6.8 Average frequency, sample 1 and 2 - Pisa . . . 150

6.9 Standard deviation, sample 1 and 2 - Pisa . . . 150

6.10 Average frequency, sample 1 and 2 - Napoli . . . 151

6.11 Standard deviation, sample 1 and 2 - Napoli . . . 151

6.12 Average frequency, sample 1 and 2 - Vercelli . . . 152

6.13 Standard deviation, sample 1 and 2 - Vercelli . . . 152

6.14 Average frequency, sample 1 and 2 - Cagliari . . . 153

6.15 Standard deviation, sample 1 and 2 - Cagliari . . . 153

6.16 Distribution of Source Goal constructions . . . 156

6.17 Distribution of the verbs indicating the conclusion of a trajectory 158 6.18 Distribution of the verbs indicating inwards trajectories . . . 159

6.19 Distribution of the verbs indicating outwards trajectories . . . 160

6.20 Distribution of the verbs indicating crossing . . . 160

6.21 Distribution of the verbs indicating motion ‘through’ Ground . . . 161

6.22 Distribution of generic passare passare . . . 162

6.23 Distribution of verbs expressing circular motion . . . 163

6.24 Distribution of the verbs expressing curvilinear motion . . . 164

6.25 Distribution of curvilinear trajectory verbs in RD corpus . . . 165

6.26 Distribution of constructions indicating straight line motion . . . . 166

6.27 Frequencies of generic verbs used in straight line motion . . . 167

6.28 Distribution of the constructions expressing deviation . . . 168

6.29 Distribution of constructions indicating generic direction . . . 169

6.30 Distribution of syntactic schemata of direction constructions . . . 170

6.31 Distribution of constructions expressing a proximal trajectory . . 171

6.34 Distribution of syntactic constructions for path . . . 178

6.35 Distribution of syntactic constructions for Direction cluster . . . . 179

6.36 Distribution of syntactic constructions for Shape cluster . . . 179

6.37 Distribution of constructions for Proximity cluster . . . 180

6.38 Overall distribution of categories . . . 181

6.39 Distribution of all the categories . . . 182

6.40 Table 27. Cardinal points in MT . . . 183

6.41 Table 28. Human dimensions in MT . . . 184

6.42 Table 29. Human dimensions in RD . . . 185

7.1 A continuum of construction categories . . . 190

Introduction

This work is a study of the constructions used in spoken Italian to express Motion Events. Motion Events, a notion introduced and elaborated on by Talmy (1985, 2000, I, II), can be lexicalised in two different ways: by expressing the main components (Path or Man-ner1) by means of some Satellite particles, or alternatively by conflating such components

in the verb root. The choice between these two different behaviours seems to be a charac-teristic feature of human languages, typologised in Verb-framed (V-framed) and Satellite-framed (S-Satellite-framed) languages. Such a typological classification tends to assign Germanic languages to the S-framed structure, while Romance languages are generally classified as V-framed. This classification has been found unsatisfactory by many scholars, who have proposed corrections, extensions and integrations. Regarding the Italian language, some S-frame inclinations have been found by Schwarze (1985); in addition, Italian exhibits a idiosyncratic behaviour integrating V-framed constructions with redundant Satellites. But, unfortunately, the distribution of V-framed and S-framed constructions in Italian does not emerge clearly from the literature, especially when spoken language is kept separate from written language2.

1Technical terms are written with initial uppercase letter when indicate elements of the Motion Event; all

uppercase if they indicate e category in the classification of contexts, and lowercase when used in a generic sense.

2The insufficiency of the data is not due to the inadequacy of theoretical approaches, but to the general

The majority of studies are based on grammatical modelling and introspective analysis. In some cases corpora have been collected with the specific aim of proving an assumption, but this is not the intent of this work. The methodologies chosen for this study are the bottom-up extensive observation of a synchronic corpus, collected through the Map Task (MT) and the Route Description (RD) methods.

Another important feature of spatial language is the cultural influence on the lexical-isation of the frames of reference. Apparently Italian shows all three frames of reference proposed by Levinson (1996, 2003), used according to some specific distributional features. The theoretical frame adopted in this dissertation is largely based on cognitive syntax and semantics in a functional perspective.

Cognitive linguistics does not offer one specific theoretical framework or a methodology, as it conceives itself as a ‘movement’ (Evans & Green, 2006). This allows a multitude of different perspectives, falling into two main branches. The first is an offspring of cognitive grammar (Langacker, 1987; Lakoff, 1987) and derives from a deep criticism of generative grammar (Chomsky, 1957; 1965). The second takes its origin from a criticism to truth-conditional semantics and does not totally reject Chomsky’s theories. The first bulk of contributions does not account in an adequate way for the relationship established between the descriptive apparatus of syntax and the cognitive processes underlying the use of lan-guage. A further development is construction grammar (Kay & Fillmore, 1999; Goldberg, 1995; Croft, 2002) that considers meaning and grammar as two faces of the same phe-nomenon and the objective of the linguistic study as the establishing of a form-meaning pair.

The second group of contributions investigate the representation of knowledge (con-ceptual structure) and the process of con(con-ceptualisation. Words serve as ‘prompts’ for the construction of meaning; meaning construction is conceptualisation. In Talmy’s words “Research in cognitive semantics is research on conceptual content and its organization in

linked to experience. The second is that semantic structure coincides with the conceptual structure, i.e. concepts are realised in linguistic and lexical terms. The consequence is that both closed-class and open-class elements come under the focus of semantic analysis, thus providing a unified account of lexical and grammatical phenomena. The third point is that the representation of meaning is encyclopaedic, and finally the construction of meaning is conceptualisation.

These two lines of thought are complementary and both recognise that syntax is ruled by the same cognitive principles that rule semantics and lexicon, as well as other levels of cognition. The most important theoretical tools are those of prototype and communicative intention.

A complete survey of cognitive linguistics positions and approaches may be too rich, complex and ambitious a task for this dissertation. I will explore only the approaches more directly related to the goals of my research.

The idea that developed from this approach is that syntax cannot be autonomous, semantics and pragmatics also play an important active role in the building up of a sentence. Categorisation does not necessarily handle discrete parameters, but rather deals with a continuum where categories keep their natural fuzziness.

The second chapter of this work presents the theories on the linguistic expressions of space. Again, this is not an exhaustive survey of all the current theoretical approaches. Only those relevant to the objectives of this thesis are presented in detail. This chapter is split into two main sections, one dealing with Motion Events and the other with spatial reference systems. After a short introduction, an overview of cognitive approaches to spatial relations and to Motion Events is presented. The work goes into some depth in the theory elaborated by Talmy. The theory about the frames of reference as developed by Levinson

(1999, 2003) is discussed together with its antecedents. Also included are some points by Denis (1994) and Tversky (1999) about route descriptions, because they are expected to prove useful in the association of frames of reference to (geographic) description strategies. The third chapter analyses some issues that arise in the analysis of Italian constructions expressing Motion Events. Its typological classification as a V-framed language does not ac-count for some S-framed constructions occurring most notably in Northern varieties. These interfere with another tendency, which seems more generalised, to ‘strengthen’ a Path-conflating verb root by a redundant particle (salire su, uscire fuori). These constructions, in turn, may fall into the broader category of phrasal verbs, for which some classifications have been proposed. For the purpose of this research, these issues bring to light the need for a clearer definition of what a Satellite is and whether it is useful or not. Some func-tional linguists put forward the alternative proposal of splitting such verbal appendices into adverbal and adnominal ones.

The fourth chapter presents in detail the corpus, articulated as two sub-corpora. The first corpus is a set of Map Task dialogues collected in the frame of the AVIP project. For our purposes, these dialogues can be described as dealing with the task of giving route directions mediated by a map. This has some consequences, such as the communication swinging from a “realistic” description of a path to the description of the lines drawn on the map itself. The consideration that the two maps available to the partners are slightly different does not impact greatly on this research. The second sub-corpus is a set of street dialogues involving the request of route directions. They are face-to-face (or side-by-side) dialogues, without mediation and with some (partial) direct perception of the environment. The sub-corpora have been transcribed using the AVIP standards, in order to guarantee perfect comparability of data, and have been processed by a specially developed tokeniser to clean them from all those elements that are not useful for statistics. A free text processing programme has been used to produce concordances and frequency.

analysis. The analysed constructions about Motion Event are taken in their broad context, including the arguments and some adjuncts. The linguistic form that translates the basic elements of the event is also cognitively grounded in the way speakers model some features of it, such as the geometric form of the path or the direction of the motion. New categories are proposed to mirror this double classification strategy, one at a lexical and syntactic level, and the other pertaining more to a cognitive and semantic account. The actual operation of labelling the corpus context by context has not been described.

Chapter six presents statistical evaluations of four main points. The first set of eval-uations is aimed at assessing the reliability of the corpus. This is a necessary step in ascertaining to what extent the sample collection methods have influenced the linguistic patterns of the corpus itself. The second task is to establish the degree of coherence within the corpus. Some discrepancies emerge between the different linguistic features in the texts collected in the four sites (Vercelli, Pisa, Napoli, Cagliari); these discrepancies can be ex-plained as regional differences but they do not seem to compromise the coherence of the corpus as a whole. The third, and more relevant part of the chapter, presents the fre-quency indices of the constructions found in the corpus from three viewpoints, i.e. (i) the frequency of any single verb in relation to the constructions in which it is realised, (ii) the frequencies of the general schemata that realise the conceptualisations taken into account (as they are defined in chapter five), and (iii) the frequencies of the classes of constructions conflating some aspects of the motion into the verb root or delegating them to some satel-lite or equivalent prepositional phrase (PP). These two categories do not seem to be polar opposites, but rather two extreme points of a continuum. The fourth measure taken into account is the distribution of different Frames of Reference throughout the corpus. This is a rather unsatisfying section, as the mediation of the map in the Map Task sub-corpus

created some ambiguities between the absolute and the relative frame of reference, making a precise definition of the categories in play difficult. Thus, the distributional study has taken into account only the difference between the use of cardinal points and the uses of body-centred categories. In addition the RD and MT data are presented separately as the elicitation method may strongly influence the interpretation of the ‘directional’ words.

Chapter seven draws some conclusions, highlighting the general results of the research. The definition of the categories applied in the corpus annotation appears to suggest a model of interaction between conceptualisations and lexico-syntactic strategies available to the speaker.

Motion and Reference Systems

1

Introduction

The language of space, i.e. the constructions by which knowledge about space and events occurring in space are expressed in the different languages of the world, has attracted the interest of many linguists of different schools and approaches over the last few decades.

In fact, how languages express an underlying model of space offers an insight into the relation between cognition and other human abilities, such as orientation or path-finding. For this reason, the study of the linguistic expression of space has an important role also in the discussions between those who adopt the universalist stance and those on the side of neo-relativism1. According to Levinson (2003: 131),

There are two reasons why the study of spatial description in language might

1The literature upon which my research rests, finds convergences and divergences within the frame of this

querelle. Hickmann & Roberts (2006: 13) point out that space is ”a rich source of intriguing and challenging questions for the cognitive sciences, providing the grounds for debates concerning the existence and the implications of universal vs. variable aspects of linguistic systems”. Universalists (Fodor, 1975; Jackendoff, 2003; Landau & Jackendoff, 1993; Li & Gleitmann, 2002, to quote some of them), using a paradigm that comes from universal grammar, try to show that all humans have a model of space in common, represented in a closed inventory of concepts: language diversity is a superficial property, motivated by diverse projection mechanisms. Relativists, instead, tend to separate the conceptual structures used to speak from those used to carry out non linguistic tasks. The conceptualisation of space is strongly conditioned by the linguistic experience. A relativist approach is adopted by Levinson (2003), Levinson & Wilkins (2006), Bowerman & Choi (2001, 2003); a moderate version, more oriented to the saussurean notion of parole, is the ”thinking for speaking” proposed by Slobin (2003, 2004, 2006), anticipated by Levelt (1999). My work does not touch on this problem.

be of special interest to cognitive science. First, space is a central cognitive domain for any roving animal, and human thinking is deeply spatial, reflecting no doubt this ancient phylogeny. The role of gestures, figures and diagrams, geometry, and maps in our thinking all attest to this fundamental role that spatial thinking plays in our cognition . . . In linguistics, this idea that spatial notions form the foundation for much of our non-spatial concepts is known as ”localism”, much evident in COGNITIVE LINGUISTICS. Secondly, language seems to offer a window on the inner world of spatial concepts.

From a purely cross-linguistic viewpoint the analysis of the spatial events gives rise to a number of observations on linguistic diversity.

The fact that space is both an important semantic domain for language, and one of the most important structures in it has been remarked upon in early studies on pronouns2.

Later on the notion of deixis acquired autonomy from the study of pronouns. B¨uhler (1934) introduces the idea that language has a ’field of pointing’ (Zeigfeld), which is centred around an origin O. Thus,

. . . drei Zeigw¨orter an die Stelle von O gesetzt werden m¨ussen, wenn dies Schema das Zeigfeld der menschlichen Sprache reprsentieren soll, n¨amlich die Zeigw¨orter hier, jetzt und ich. (B¨uhler, 1934 (2000): 66).

These three instances of Origo build the basis of future research on deixis, be it personal, temporal, or local3.

2The first studies on indo-european pronouns go back to Brugmann (1904) and Benveniste (1956).

Ac-cording to Brugman (1904: 1-8) the terms ’demonstrative’ and ’deictic’ are equivalent and their role is determined by a relation that holds between the speaker and a perceptive image. The demonstrative pro-nouns contain an act of reference with respect to the speaker’s viewpoint. Benveniste (1956) discusses the nature of all pronouns. Starting from the personal pronouns, for which he maintains that the real opposition is je/tu as the third person is, actually, a non-person, he relates to them a series of indicateurs. These include the demonstratives which are related to the first and second person following the Latin distinction hic/iste.

3A broader definition has been provided by Lyons (1977: 637) who makes a more extensive reference to

Deixis represents a crucial field where the relations between semantics and pragmatics are discussed4. The type of deixis relevant to this research is spatial/local deixis5. The elements

of spatial deixis are local adverbs, and demonstratives6, deictic particles, and deictic verbs.

A complete survey of the different approaches to space lies beyond the scope of this work. Thus, in this chapter, only the more recent theoretical constructs, relevant to this research, will be described.

The research presented in this dissertation is based on cognitive semantics principles, also taking into account relevant works in the field of linguistic typology, functional grammar and anthropological linguistics. There are many commonalities to these approaches7, and the studies seem to concentrate on the expressions of movement and the reference systems in which spatial states or motions occur. The central concepts for the theoretical elaborations are Motion Event and, in a complementary way, Frame of Reference. The Motion Event accounts for those verbs that establish a spatial relationship between objects. Some of these relationships are expressed in a topological space in terms of vectors, contact, and relative positions. Others require a system of coordinates, often referred to as Frame of Reference. The two notions are complementary in the description of space. The notion of Motion Event was introduced by cognitive semantics, while many functional linguists prefer the dichotomy displacement/movement and the account that derives from it. Motion Event

4See Bertuccelli Papi (1993: 196).

5An important work on spatial deixis, in which many different languages are compared, is due to

Ander-son & Keenan (1985). For Italian see Benedetti & Ricca (2002) for a study of deictic adverbs over different Mediterranean languages, Ricca (1993) for the deictic verbs, Da Milano (2005) for an inter-linguistic per-spective on the European demonstrative systems.

6These generate two-term systems opposing ’close to the speaker’ to ’far from the speaker’, three-term

systems divided into person-oriented and distance-oriented, and multiple systems involving other dimensions. In this area, Jungbluth (2003) maintains that Spanish demonstratives are not distance-oriented, but are dyad-oriented, i.e. centred on the different relative positions of conversation participants.

7Croft (1999) reviews the main points of convergence between typology and cognitive grammar and

remarks that the difference is not in the structure of the theories but in the perspective that the two approaches take; ”. . . a typologist looks for universals across languages, not within them . . . ”(1999: 62). He adds that ”grammatical universals are to be explained as maps of conceptual space, organised so that particular-language categories/constructions cover functions in a coherent region of the cognitive map”(1999: 76).

makes use of concepts derived from Gestallt psychology, such as the pair Figure/Ground. These two conceptual constructs interact with many other theoretical approaches that contribute to extend, complete and articulate them.

1.1 From Generative Grammar to Generative Semantics and Cognition The theoretical approach that motivates the selection and categorisation of the basic lin-guistic units in this research is the one developed by cognitive linlin-guistics8. Other theories derived from the universalist perspective of generative grammar and semantics have antic-ipated and paralleled some positions of cognitive linguistics.

The idea that conceptual configurations map onto lexical structures anticipates the notions of lexicalisation and conflation. Also, the idea that a set of conceptual elements participate into the definition of an event, anticipates the notion of Motion Event. It is, thus, necessary to devote some space to such views, in particular Jackendoff’s approach, and Fillmore’s frame semantic, especially because some of the ideas developed within the frame of such theories will be used to integrate the basic Motion Event configuration.

1.1.1 A Cognitive Model for Semantics

Moving from generative grammar, generative semantics (Katz & Fodor, 1965) and then from lexicalism (Gruber, 1976), Jackendoff (1983) develops a semantic theory which tries to match the requisites of preserving the universal assumption of universal grammar and the modularity of mind in a more sophisticated and realistic way than that proposed by Fodor (1975). The objective of the theory is to find the mechanisms that map9 cognitive

psychological concepts onto syntactic structures.

8For a general introduction to cognitive linguistics see Ungerer & Schmidt (1997), Croft & Cruse (2004),

Gaeta & Luraghi (2004), Evans & Green (2006).

9In a general sense ‘mappings’ connect entities in one set with entities in another; from a cognitive point

of view the sets involved will be conceptual areas. A typology of mapping operations in cognitive sciences has been defined by Fauconnier (1997), who, recognises three types, projection, pragmatic, and schema mapping.

The notion upon which Jackendoff bases his semantic theories is Representational Mod-ularity, which is a version of what he calls Fodorian Modularity with an extra device that works as an interface between different modules of the theory. The modules involved, as presented in (Jackendoff, 2003), are the phonological structure, the syntactic structure, the elements forming the so called semantic/conceptual structure (CS) and the spatial structure, or representation (SR). These two structures are connected each with its own representation language and there is a number of interfaces that connect them. In a general (Jackendoff, 1999: 3) sense CS encodes “propositional representations”, and SR is the locus of “image schema” or “mental model” representations.

The relation of the two modules is visualised in Figure 2.110, but the relevant theoretical

objective is to define the interfaces between the modules CS and SR, as well as between CS and syntax.

Figure 2.1: Language and vision

CS is an ‘algebraic’ representation and must encode a number of elements, namely (i) pointers to the sensory modalities, (ii) distinction between tokens and types, (iii) quantifi-cation and quantifier scoping, (iv) abstract action schemata, (v) taxonomic relations, (vi)

social predicates, and (vii) modal predicates. Not all these elements need to find a mapping in syntax. SR has a ‘geometric’ nature and must encode all and only the physical aspects of an object. This does not mean that it must reproduce objects in the mind, as if they were ‘statues in the head’, but it has an interface to an imagistic representation module.

Following the lexicalist hypothesis the interfaces between all the modules are to be found in the definition of the lexical entry. Any lexical entry consists in the association of a phonological representation, a syntactic description, the elements of a semantic/cognitive

description, the spatial description and the auditory properties.

Jackendoff (1987) explores the hypothesis that there might be a correspondence be-tween the 3D model proposed by Marr (1982) and his conceptual structure (Jackendoff, 1983); the conclusion is that there are significant correspondences between the two levels of representation.

Thus perceptual aspects are to be included in the ‘meaning’ of the lexical items. Thus CS and SR will form together what is called CONCEPT (Jackendoff, 2002: 12).

Experiments11have shown that there is a tight cooperation between linguistic and visual

input in problem solving, but the question is how does information go from one module to the other? The solution proposed is that, as all lexical entries contain an SR component, this specifies axes and frames directly in the geometric format of SR. When solving the experimental problem, the SR of the lexical items directly interact with the visual input.

A deeper inspection of the relation between CS and SR lies beyond the objectives of this work, but it has been necessary to introduce the role of the lexicon as an interface between modules. In particular such an interface relates the conceptual structure to the surface reali-sation; the corresponding mapping from conceptualisation to its syntactic/lexical realisation is lexicalisation.

1.1.2 Lexicalisation Process for the Verbs of Motion

Space plays a prominent role in conceptualisations and in lexicalisation both in itself, and in a metaphorical sense. In fact many grammatical constructions that describe physical objects in space are also used in expressions that describe non-spatial domains12. This

provides a strong basis to the notion of ‘semantic field’, i.e. similarities between concepts, where space plays a dominant role due to its being biologically inherited and its connection to perception (Jackendoff, 2002).

In Jackendoff’s opinion spatial expressions, for example prepositions, are polysemic and can take different meanings in addition to the original spatial ones. The evolution of their meanings can be accounted for either in terms of derivation or in terms of parallelism. A derivational approach in cognitive linguistics consists in recognizing the priority of the spatial field, from where the other meanings are derived by metaphor or image-schema transformation, in Lakoff and Johnson’s terms13.

Jackendoff himself prefers the hypothesis of ‘parallel instantiations’ from a more abstract schema (Jackendoff 1976, 1983, 2003). The examples illustrating such parallelism range over Location, Possession, Simple property, and Simple schedule for be-sentences (state sentences), Changes (of location and possession) for go/change verbs, and Causation (of stasis) for keep verbs (Jackendoff, 2003: 356 ff.). From these basic ideas, the author identifies a number of function-argument structures that hold across fields. Any function, say BE (X, Y), is ‘crossed’ with ‘field features’ like Spatial or Possession, that determine the nature

12This is true both for Jackendoff (2003) and for Levinson (2003), who goes deeper on this subject also by

means of experiments. See also Landau & Jackendoff (1993) who state that ”any aspect of space that can be expressed in language must also be present in non linguistic spatial representations . . . important not only because of the richness and complexity of spatial language itself, but also because the organization of spatial language extends readily to many abstract domains such as time, status, possession, and social organization . . . ”.

13Metaphors are conventional associations of concepts in one domain with concepts in another domain

(Lakoff & Johnson, 2002). Image schemas are generalisations that arise in the conceptual system from sensory and perceptual experience. They are generalisations over some aspects of perceived situations such as the set of physical phenomena that give rise to the image schema up-down (Johnson, 1987).

of the arguments. If the field is Spatial X is an object and Y is a location, while if it is

Possession X is an object and Y is a person (an owner).

The relations relevant to the spatial language are:

1. GO (X,Y), which underlies go verbs, assigns X to an Object and Y to a Path or a Trajectory as in example (1)a; such an assignment holds also in the other field.

2. EXT (X, Path), which accounts for a so called non-temporal extension, as in sentence (1)b

3. ORIENT (X, Path), which accounts for orientation in sentences like, example (1)c

(1)

a. The cat entered the room

b. The railway runs across the wood c. The sign points to the sea

These functions “are major members of a family of “core functions” around which situ-ations (States and Events) are organized” (Jackendoff, 2003: 363). They make up skeletons for the meanings of verbs and prepositions, according to the lexical model developed since the early theoretical constructs by Jackendoff14. Sentence (2)a corresponds to the syntactic

representation in (2)b; its CS in (2)c projects the tree in (2)d. (2)

a. John went into the room

b. [John]i wentj [intok [the room]m]

c. [Event GO ([Object JOHN]i , [P ath TO ([P lace IN ([Object ROOM]m )])]k )]j

d. see Figure 2.2

A different verb is used in (3)a to lexicalise the same concept of (2); to this (3)b is associated as CS. The projected tree is Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: Example (2)d, not incorporating verb

(3)

a. John entered the room

b. [Event GO ([Object X]obl , [P ath TO ([P lace IN ([ObjectY] )])] )]I

c. see Figure 2.3

In this last example the main verb “incorporates” the Path- and Place-functions. The fact that both X and Y are Objects, explains why enter is transitive, as it incorpo-rates the Path, but the object Y still remains to be satisfied. This notion of “incorporation” is very similar to the notion of “conflation” due to Talmy15.

1.2 Motion and Frame Semantics: a Knowledge Representation Lan-guage

An encyclopaedic view of word meanings is at the basis of the Frame Semantics approach by Fillmore (1977b, 1982).

Figure 2.3: Example (3)c, incorporating verb

The early theoretical attempt by Fillmore (1968, 1977a) has been Case Grammar, that aimed at relating constituents of a sentence to their roles with respect to the main verb. Cases are roles of the main action of a sentence and cover different functions. Basic Cases are Agent, Patient, and Instrument; spatial roles are Location, Source, Goal, and Path. They provide a ground to the relation between deep and surface structure, and remain a syntactic notion.

Moving to the level of semantics, frames16 provide a representation language that

or-ganises semantic knowledge. A frame is a way of representing experience at a conceptual level and in a schematic way. Frames can be understood as ‘stereotyped scenarios’, a way of encoding portions of real world in a schematised form. As it is a way of capturing gen-eral features of one’s experience, a frame is the support to understand semantic relations within group of words. The most credited example is that of the commercial event (Fill-more, 1977b: 58) that relates verbs like buy, sell, pay, spend, charge, and cost with one another. On the other side, any event frame includes a set of participant roles, comparable with Cases. The minimal roles for the commercial event are BUYER, SELLER, GOODS,

and PAYMENT. The roles of an event determine the valence17, i.e. the number and the

semantic roles required by a verb. For example, the verb buy has two valences, as it requires a BUYER and some GOODS, while pay is trivalent (BUYER, PAYMENT, and GOODS). Valence is not a stable property of a verb, but may change over different uses of it.

1.2.1 The FrameNet Project

Frame Semantics has found a remarkable application in the FrameNet project, a research programme that aims at the usage-based study of lexical semantics. In a usage-based view, the meaning of words is not abstract and separated from the context in which words themselves are used. The objective of this project is to set up a collection of semantically annotated lexical items by an extensive annotation of contexts of usage. The annotation shall take into account the fundamentals of frame semantics together with the notion of

inheritance. Frames are generic schemata that are mapped onto diverse instances; such

an instantiation purports the addition of some new frame element (role). Thus, the four elements of the commercial event frame are to be integrated if the sub-frame Transaction is instantiated and a mortgage is in question; the roles of BORROWER, LOAN, LENDER are to be added, with the restrictions that BORROWER=BUYER, LOAN=PAYMENT.

A frame consists in a list of verbs participating into it and a list of Frame Elements. The frame ‘Motion’ contains the verbs blow, coast, drift, float, fly, glide, go, meander,

move, roll, snake, soar, swerve, swing, undulate, weave, wind, zigzag18. Their coexistence

in the same frame means that they characterise in different ways the same event. The Frame Elements involved in Motion are Area, Carrier, Containing-event, Degree, Depictive, Direction, Distance, Duration, Goal, Manner, Path, Path-shape, Place, Purpose, Result, Source, Speed, Theme, Time. Some of these Frame elements (FEs) participate into the basic definition of the frame, others are added to them to elaborate some specific aspects.

17A common view distinguishes a syntactic from semantic valence. See Jezek (2003).

The core definition, that singles out the core FEs, is “Some entity (Theme) starts out in one place (Source) and ends up in some other place (Goal), having covered some space between the two (Path). Alternatively, the Area or Direction in which the Theme moves or the Distance of the movement may be mentioned.” The other FEs provide elaborations on the Goal-profiling (arrive, reach), Source-profiling (leave, depart), Manner of motion (run, jog) or places. Each FE has its own definition and at least one context to illustrate its behaviour. Thus Theme is defined as “. . . the entity that changes location. . . it is not a self-mover”, and the Goal is “. . . the location the Theme ends up in” and the displayed example is “The car moved into the slow lane”. Some of the definitions will be used later19. An inspection of a general event frame is the first step to get a list of possible FEs. They are used to annotate different participants into sentences, and frame element groups (FEGs) are groups of FEs that occur in single phrases or sentences. The complete list of FEGs associated to a verb, i.e. to the set of sentences actually annotated for a single lexical unit is a sufficient description for that lexical unit. In more formal terms, it is possible to abstract a more efficient description, for instance considering the more persistent FEs as obligatory and the other as optional20.

1.3 Space and Cognition

As already seen above, generative grammar and its derivations, such as case grammar and cognitive semantics, focus on the conceptual structure that motivates and accounts for the formal lexical and syntactic processes by which a sentence is generated.

A different approach on cognition is taken by cognitive linguists and grammarians, who put concepts in the centre of their theoretical constructions, minimising the role of a formal structure for syntax and lexicon. The stress of such theories is rather on the processes that convert concepts into linguistic expressions.

19See chapter five §3.

20FrameNet is still in progress, but the results of the activity of annotation is made available in the site

A comprehensive cognitive account of space in language is due to Talmy, but some of the concepts developed in detail in his theory of the Motion Event have been anticipated by other linguists, such as Langacker (1987, 1999).

Langacker is mainly concerned with the design of a cognitive grammar based on the no-tion of profiling that motivates the asymmetry inherent in linguistic expression. Profiling21

is “a kind of focusing of attention” (Langacker, 1999: 28) and leads to the identification of a basic asymmetry in the expression of relational predications. In such a relation asymmetry is between something that is focused and something else with respect to which it is put in focus. The focused object is called trajector, while the reference object is called landmark. The immediate example of such an asymmetry is the opposition subject/object, where the subject is a trajector and the object a landmark.

These concepts have, in principle, nothing to do with space and spatial modelling, but interesting accounts of spatial relations have been proposed in terms of profiling and asymmetry. Thus, the prepositions with, across, above, below, are explained in terms of relations between trajector and landmark, graphically rendered as in Figure 2.4 and in Figure 2.5.

Figure 2.4: Preposition with and across

21This corresponds to Talmy’s ‘attentional windowing’, the mechanism by which a particular aspect of

a scene is highlighted with respect to the others. Attentional windowing is one of the four schematising systems (see later in this paragraph).

Figure 2.5: Preposition above and below

In particular the explanation of the pair above/below adequately captures the structural similarities of the two prepositions, the difference between them being expressed in terms of the operation of profiling, made explicit by the different relative positions of trajector and

landmark.

The conceptual instruments provided by Langacker theories do not offer specific material for the building of a theory of space in language, but establish its conceptual priority.

If Langacker takes space as a metaphor to account for general linguistic concepts, a relevant and concrete contribution to the theory of spatial language is the one done by Talmy22. The spatial structure consists into two subsystems, the ‘schematic delineations’

that are conceptualized as existing in any space and the ‘configurations of material’ that occupy the volume defined by the first subsystem. The first subsystem relies on concepts like region, location, path, and placement, while the second subsystem distinguishes between

objects and mass.

The first task of spatial language is locating objects in space, mostly by means of closed-class elements, which, in general tend to mark one object as primary in focus, and charac-terise its position with respect to a secondary object. Primary and secondary objects are called respectively Figure and Ground.

22I make reference to the two volumes by Talmy, published in 2000. They collect all the previous articles

Figure and Ground cover largely the similar notions of Trajector and Landmark intro-duced by Langacker, and share with them the principle that in linguistic expression there is an intrinsic asymmetry, with a primary and a secondary object.

The way how language structures the domain of space is by means of the so-called schematic systems, that contribute conceptual dimensions in the modelling of space. The schematic systems presented by Talmy are the following four (Talmy, 2000: I, 214 ff.):

1. configurational structure that specifies geometries. Such geometries fall into the two categories of ‘stationariness’ and ‘motion’, explicitly represented by a reduced number of basic formulas which underlie expressions of movement (MOVE) and state (BELOC)

2. perspective point, “the point within a scene at which one conceptually places one’s ”mental eyes” to look out over the rest of the scene” (Talmy, 2000: I, 217). This schema explains differences between examples (4)a where a stationary distal perspec-tive is adopted, and (4)b where, instead, a moving proximal perspecperspec-tive motivates the use of the preposition through.

(4)

a. There are some houses in the valley

b. There is a house every now and then through the valley

3. distribution of attention which determines the focused elements in a scene and ac-counts for alternative patterns of primary and secondary objects.

4. force dynamics which accounts for the way how objects can relate themselves to a possible exertion of force. It motivates the difference between, for example, The ball

rolled along the green, force-dynamically neutral, and The ball kept rolling along the green, force-implicational.

These four systems should account for all the aspects of spatial language, from the point of view of the projection of conceptual structures onto linguistic expressions.

2

Motion Events

The central construct of spatial language, at least for what concerns the lexico-syntactic aspect, is the Motion Event. This is the basic situation of an object, typically a Figure located or moving with respect to another object, the Ground, according to a spatial relation called Path, together with a Co-Event that relates to it in different ways, including Manner or Cause23.

The same frame gives account of real translational motion (MOVE) and stationary location (BELOC). Translational motion is the one by which the Figure changes its location

along with time. Other non translational motions are admitted like rotation or obscillation, called ‘self-contained motion’. In the following paragraphs the properties of the above mentioned components are examined. Then the lexicalisation process is presented, with special attention to conflation.

2.1 Figure and Ground

The definition of Figure and Ground in the Motion Event is very simple. The Figure is something that Moves, but may be also in a stationary relation, with respect to another object called the Ground. These two concepts have been taken from Gestallt psychology to account for a basic asymmetry in all linguistic expressions24. In the domain of spatial

language, the notions of Figure and Ground assume the character of spatial concepts. According to Talmy (2000: 26) these two concepts are more comprehensive than Fill-more’s (1977a) cases of Source, Goal, Location, and Path. The distinction between Location and the other cases is captured in the distinction between MOVE and BELOC, while the

23For an elaboration of these concepts see Talmy (1972, 1985, 2000). 24See § 1.3.

notion of Source and Goal include some notion of trajectory that should be accounted for in the description of Path.

The elements playing a role in a complete description of the linguistic rendering of space are:

1. the degree of partiteness which distinguishes near, characterised by a single point Ground, and between, where the Ground is split into two parts

2. the qualitative geometry, which distinguishes a Ground as plane (across), as a cylinder (through), or a single volume (into)

3. the geometry fictively associated to the Ground25.

Locations can be characterised using more than one reference object, resorting on a Secondary Reference Object, as in the sentence In this fish species, the swim bladder is

ventral to the spine where swim bladder is a Figure, spine is a primary Reference Object,

and ventral to implies reference to a secondary Reference Object.

The basic relations between Figure and Ground are listed below (Talmy, 2000: I, 215-216). They are expressed in form of deep preposition26 written in capitals. Following

the deep preposition is the description of a fundamental Ground schema, such as ’point’, ’unbounded extent’, ’bounded extent’, and a ’point pair’:

a. A point BELOC AT a point, for a bounded extent of time

b. A point MOVE TO a point, at a point of time c. A point MOVE FROM a point, at a point of time d. A point MOVE VIA a point, at a point of time

e. A point MOVE ALONG an unbounded extent, for a bounded extent of time

25For the influence of Ground’s geometry on the interpretation of some Italian verbs, see chapter six §4.2.3,

4.2.4, 4.4.3, and chapter seven.

e’. A point MOVE TOWARD a point, for a bounded extent of time e”. placeA point MOVE WAY-FROM a point, for a bounded extent

f. A point MOVE ALENGTH a bounded extent, in a bounded extent of time f’. A point MOVE FROM-TO a point pair, in a bounded extent of time g. A point MOVE ALONG-TO an extent bounded at a terminating point, at a point of time/in a bounded extent of time

h. A point MOVE FROM-ALONG an extent bounded at a beginning point, since a point of time/for a bounded extent of time

The basic prepositions are applicable to both static relations and to movement. The defi-nition of actual prepositions, derived from the above introduced ones, is given in terms of conditions on Figure (F) and Ground (G). Thus, for instance, in order for the preposition

across to be applicable it is necessary that: • F is linear

• G is ribbonal

• the axis of F is horizontal

• the axes of F and G are perpendicular • F is parallel to the plane of G

• F’s length is at least equal to the width of G • F touches both edges of G

• any extension of F is not enormously greater on one side than on the other

If some of these constraints fails to apply, this will cause some other linguistic expressions to become more suitable.

2.1.1 Path

The simplest definition of Path is that it accounts for the location of the Figure with respect to the Ground if the verb is stative. If the verb is a motion verb it accounts for the path followed by the Figure also with respect to the Ground.

It is a compound entity with at least three main components, the Vector, the Confor-mation, and the Deictic. The Vector refers to the basic motion activity and is formed by a small set of so-called formulas based on the deep prepositions listed above. The Confor-mation relates the motion to the form of the Ground object, distinguishing, for instance the cases where the motion goes to the ‘inside’ of the Ground, or to the external surface of it. Thus, the underlying deep prepositions are only AT, TO, and FROM, but the formulas take into account the form of the Ground object. Combinations of Vector and Conformation generate complex prepositions like past, across, through, alongside etc. Finally the Deictic component indicates the motion toward or away from the speaker.

2.1.2 Co-events and Manner

Additional elements take part into the Motion event as accompanying features. Co-event is an event that accompanies and supports the main motion event. The most prominent is Manner, that describes the way how a motion is performed. In BELOC Manner can account

for differences between verbs like stay, lay, and lean, while for MOVE verbs like run, stumble or jump realise it. Another prominent type of Co-event is Cause, represented by verbs like

push/throw/kick as they highlight (profile) the action that causes the motion. Other minor

types of Co-event are Enablement, Reverse Enablement, Concomitance, Concurrent Result, and Subsequence. The list of Co-events is, in principle open, but actually only Cause and Manner are widely present in the majority of constructions of diverse languages.

2.1.3 Lexicalisation Patterns

The way how the above described components interplay with one another originates different constructions in spatial language. There are different types of superficial realisations of a conceptual structure but the more important is lexicalisation. Talmy assumes that

lexicalization is involved where a particular meaning component is found to be in regular association with a particular morpheme. More broadly, the study of lexicalization must also address the case where a set of meaning components, bearing particular relations to each other, is in association with a morpheme, making up the whole of the morpheme’s meaning. In the clearest case, one morpheme’s semantic makeup is equivalent to that of a set of other morphemes in a syntactic construction, where each of the latter morphemes has one of the original morpheme’s meaning components. A familiar example here is the approximate semantic equivalence between kill and make die. (Talmy, 2000: II, 24).

One of the processes of lexical formation is conflation. Dealing with verbs it consists in the possibility of two or more concepts to be expressed in a single verb root27. Different

types of conflation distinguish different types of verbs. The balance between elements conflated into the verb root and elements expressed in a ‘peripheral’ way yields a great number of diverse linguistic constructions. The main typological categories of conflation in the verb roots expressing Motion Events are Motion+Co-Event28, Motion+Path, and

Motion+Figure.

27Conflation corresponds roughly to ‘lexicalization’ in McCawley (1968), and to ‘incorporation’ in Gruber

(1965), that is the mapping of pre-lexical categories into a lexical item similar to the one into which direct mapping should ordinarily occur.

28Motion+Co-Event is an extension of the first version of the theory (Talmy, 1985: 62-68) where only

Conflation of the type MOVE+Co-Event is an extension of an early formulation in which only Manner and Cause were taken into account. This lexicalisation pattern is wide-spread and motivates typological distinctions, as it will be shown below. There are different examples of such a conflation. MOVE+Manner is present in cases like in example (5)

(5)

a. The rock slid / rolled / bounced down the hill [non-Agentive] b. I slid / rolled / bounced the keg into the store room [Agentive]

c. I run / limped / jumped / stumbled / rushed / groped my way down the stair [self-Agentive]

MOVE+Cause is realised in the sentences in (6) (6)

a. The napkin blew off the table [non-Agentive] b. I blew the ant off my plate [Agentive]

Other verbs conflate the remaining Co-Events, as appears in the examples in (7) (7)

a. Could you grab that bottle down off the shelf [Enablement] b. Ich habe den Hund losgekettet [Reverse-Enablement] c. She wore a green dress to the party [Concomitance] d. The door slammed shut [Concurrent Result]

e. I’ll stop down at your office [Subsequence]

Conflation of the type MOVE+Path is discussed in a number of studies in linguistic typology. Motion and Path can be conflated or non-conflate as in the examples (8)a and b.

a. John entered the room b. John went into the room.

The construction is shown in Figure 2.6.

Figure 2.6: Conflation of the type MOVE+Path

Systematic conflation of Motion+Path occurs in Romance languages like Spanish (9)

a. La botella entr`o a la cueva (flotando) The bottle entered in the cave (by floating) b. La botella cruz`o el canal (flotando) The bottle crossed the channel (by floating)

MOVE+Figure characterises English verbs like it rains or he spits, as in both of them the nature of the Figure is implied in the verb itself, represented in the Figure 2.7.

For some languages, this configuration of lexicalisation is dominant like in Atsugewi, a Hokan language. Atsugewi verb roots may express the type of Figure involved in the motion, as –lup-, that indicates motion or location of a ‘small shiny spherical object’ or –swal-, referred to a ‘limp linear object suspended by one end’.

Figure 2.7: MOVE+Figure

2.1.4 Lexicalisation Patterns as Typological Classification

Languages differ in the way they lexicalise spatial constructions, conflating different ele-ments of the Motion Event in the verb root. In particular, conflations of Path and Motion and Motion with Manner are at the origin of a typological classification system. Some languages prefer to use verbs that conflate Path and Motion, while other languages prefer to express the same concept by lexicalising the motion by a (generic) verb root and the addition of a particle that represent the Path. This distribution is well represented in Ger-man example (10), where the Path is indicated in the particle weg, or Russian example (11) where the Path is encoded in the pre-verbs v-/vy-, or English verbs like run up, step aside or walk away.

(10)

Johann geht erst morgen weg

Johann goes out early in the morning (11)

a. Mark vkhodit (v dom) b. Mark in-goes (in house)

c. Mark vykhodit (iz doma/na ulicu) d. Mark out-goes (from house/into street)

These languages are called S-framed, because the particles are called Satellites29. As it has been said above, other languages, instead, prefer to conflate Path and Motion, like Romance languages. The difference between the two behaviours is well represented in the example (9) vs. English (12) The bottle floated into the cave.

A distinguished relation links Path and Manner, as in general languages conflating Mo-tion+Manner, like English, tend to represent Path by means of a Satellite, while languages conflating Motion+Path, tend to employ a Satellite to represent Manner.

Distinguished examples for Motion+Manner conflation are English walk as opposed to run or climb. Motion+Path is well represented in Romance languages, as shown by the above Spanish examples, where Manner is expressed by a gerund. Nez Perce, a polysynthetic language of North America, has a complex system of prefixes that systematically determine the Manner of a motion. Thus, the basic verb l`ahsa, indicating ‘motion upwards’, can combine with wil´e- ‘running’, wat- ‘wading’, we- ‘flying’ and many other prefixes. Atsugewi has already been shown to conflate Motion and Figure.

The table in Figure 2.8 lists languages according to the above lexicalisation patterns with the correspondent most relevant behaviours.

Figure 2.8: Classification of languages according to the lexicalisation patterns

A deeper inspection into the balance between Manner and Path expressions leads Slobin (2006) to the introduction of the concept of degree of salience of Manner across languages, defined as

the level of attention paid to manner in describing events. . . . The degree of manner salience of a particular language can be assessed by a variety of mea-sures of language use, comparing descriptions of motion events across languages and genres (. . . ) as well as translation of motion event descriptions between languages. Another measure of manner salience is lexical . . . (Slobin, 2006: 64). A low degree of attention to manner in Romance languages motivates the correspon-dence of Spanish saltar and French bondir to English hop, jump, leap, spring, bound. 30.

30An experiment carried out by Slobin (2006) having a number of subjects telling narratives in Spanish,

French, Turkish, Russian, and others shows that the first two groups of speakers have no manner-of-motion verbs, while in the Russian narratives 100% of the verbs indicate manner.

Slobin (2004, 2006) proposes a third type of languages, called equipollently-framed, a kind of language in which path and manner have equal morphosyntactic status. This type of lexicalisation pattern gives origin to three subtypes (Slobin, 2006: 64):

1. serial-verb languages, namely Niger-Congo, Hmong-Mien, Sino-Tibetan, Tai-Kadai, Mon-Khmer, (some) Austronesian; in these languages motion is represented as a series of verb roots, among which it is not clear which one is the main verb, as Mandarin Chinese:

Fei1 chu1 lai2 yi1 zhi1 mao1tou2ying1

Fly exit come one only owl

Where the Path verb chu1 can occur with both manner verbs and alone.

2. bipartite verb languages, namely Hokan and Penutian languages, described by De-Lancey (1989) in which motion verbs consist of two morphemes of equal status, one expressing manner and the other path. A similar behaviour has been noticed by Talmy (2000: 113) in Nez Perce, which has manner prefixes, such as ququ–lahsa ‘gallop-ascend’ (see also Aoki, 1970)

3. generic verb languages such as the Australian language Jaminjung (Schultze-Berndt 2000); in order to encode Motion Events Jaminjung combines one of five verbs ex-pressing a deictic or aspectual function: ‘go’ ‘come’ ‘fall’ ‘hit’ ‘do’ with satellite-like elements, “coverbs”, that encode both path and manner in the same fashion.

This type is to be added to Talmy’s dichotomy V-framed S-framed. An alternative point of view is that adopted by some European typologists. Their theoretical ground is the classification of motion verbs proposed by Tesni`ere (1959: 308)31. He distinguishes

between mouvement and d´eplacement, the first indicating the way how people move, and

thus roughly coinciding with Talmy’s Manner of motion, and the second indicating the simple change of location, i.e. the plain motion, in Talmy’s terms.

Moving from this distinction, W¨alchli (2001) proposed an alternative method to account for the linguistic expression of events of motion. W¨alchli position differs from Talmy’s in two points, the distribution of the information over the entire clause and the distribution of the information in three loci. The semantics of the motion event is distributed over the clause in its different components, intended in a plainly functional sense. The expression being studied pertains to d´eplacement and is encoded in three loci, a verbal, an adnominal, and an adverbal locus. Thus, in the English sentence (13)a displacement is encoded adverbally by in, and adnominally by from. In Spanish (13)b motion is expressed verbally by entr`o and adnominally by a.

(13)

a. The cat ran in from the garden b. El gato entr`o corriendo a la casa

This view is considered more flexible and adequate, as in the analysis of Motion Events it rests on a less ambiguous notion of Satellite.

Also in Italian32, in some of its Northern varieties, some constructions have been ob-served, that are difficult to classify. In particular it appears that, although Italian has been classified, together with all the other Romance languages, as a V-framed language, it exhibits Satellite constructions33.

3

From Motion to Frame of Reference

In the previous paragraphs I tried to offer an exhaustive and clear picture of the components and the linguistic realisation of the Motion Event. Some of the elements of the Motion Event

32See Schwarze (1985), Spreafico (in press). 33See chapter three §3.1

occur also in another spatial domain, that of Frame of Reference. About the connection between Motion Event and Frame of Reference, the opinion of Levinson (2003: 68) is that

. . . nearly all descriptions of motion also involve reference to ground locations (. . . ) two crucial grounds for motion descriptions are ”goal” (the landmark towards which motion is directed) and ”source” (or the landmark from which it originates.

The description of motion implies a perspective beyond spatial deixis, based on notions like right, left, above, below or in front of. This paragraph is devoted to a short presentation of the theories of reference systems.

3.1 Localisation Strategies

One of the basic human abilities is that of being able to answer where-questions, i.e. ques-tions about where some object is. The same ability is involved in the description of motion, that is a way of describing change of location.

The way how spatial relations are expressed in the different languages is a field of great linguistic diversity that is motivated by diverse cultural models of space34. The

number of possible combinations ranges from few elements, like Italian, to some scores of possibilities, like caucasic languages as Tabarassian, that has 40 spatial cases, or Avar, that has a theoretical paradigm of 1129 combinations. The dimensions that are to be combined to form such complex relation systems are established in terms of a position with respect to a vertical axis, with respect to the periphery of a point, and the direction of motion, if any. The perception of the spatial relations may be derived from different world models.

34Cross-linguistic studies have highlighted many realisations in different languages. For e recent

3.1.1 Environmental and Anthropocentric References

The influence of the environment onto the type of spatial reference system is quite rare (Cardona, 2001). The community of the Mocheni, a Germanic minority living in Trentino, has an orientation system based on three environmentally determined axes, the direction of the creek in the valley, an axis perpendicular to the valley, and an axis traversing the valley. Similar environment-driven systems are known in Hopi or Lao. Hopi takes as reference point the parts of the mesa; it distinguishes q¨oy- ”the other side of the rock” tu- that is the foot of the rocky wall and tum- the edge of the mesa. Lao takes the Mekong river as orientation base and it works as an absolute bearings system running from north to south. The most typical system of reference is anthropocentric, that takes the human body as a model of the surrounding space. The human body defines six axes, up, down, in front,

behind, on the left, and on the right. These six directions can be realised in many different

ways in different languages, by means of direct mapping of such directions or by projecting them on other objects, such as trees or baskets. The projection of human dimensions on objects may cause the attribution of anatomic parts to those objects, that will have a head, a chest, a mouth, lips and other parts that identify the object’s parts.

3.2 Vertical and Horizontal Dimensions

The above sketched models of space rely on metaphors drawn from nature. Taking a more abstract view, spatial relations are referred to natural axes that determine a system of reference. These axes are established in terms of either linear or angular measurements (Piaget, et al., 1999). Linear measures rely on a one-to-one correspondence between points to be located and dimensions to be measured. On the contrary, angular measures rely on a one-to-many correspondence and define axial systems of reference.

These axial systems fall into two main classes, vertical and horizontal dimensions. The vertical dimension establishes an up/down pair, that is determined by the gravity force.