UNIVERSITY OF MESSINA

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS

PH. D. IN ECONOMICS, MANAGEMENT AND STATISTICS

XXXII CYCLE

ESSAYS ON POLITICAL COMPETITION,

ECONOMIC LIBERALIZATION AND GROWTH

Candidate

ANNUNZIATA CALABRESE

SUPERVISORS:

Prof. DARIO ANSALDO PATTI MAIMONE

Prof. LEONE LEONIDA

“The source of economic growth have variously been ascribed by

econo-mists to technology, human capital (education and skills of human

be-ings), and economies of scale (falling costs associated with the growth of

large scale markets). While these are clear proximate sources of

produc-tivity increase and hence growth, they are not ultimate sources.

If they were, growth would have long since become universal because the

desire for improvement in well being appears to be a universal human

trait and all societies would have to do is invest in the technologies or

skills and knowledge that would produce desirable results.

But throughout history (and even in much of the modern world) societies

have failed to make the “proper” investments.

Society does not make the necessary investment because the institutional

and organizational structure does not provide the incentives to do so.

The failures of human organization underlie not only economic

backward-ness but social, intellectual, and political backwardbackward-ness as well.

Indeed the search for efficient economic organization lead us to political

organization, since it is the polity that define and enforces the economic

rules of the game.”

DOUGLAS CECIL NORTH

Index

Acknowledgments . . . 7

Introduction . . . 8

Chapter 1 The Determinants of Inefficient Institutions: A Review of the Literature . . . . 14

1 Introduction . . . 15

2 Meaning of Institutions . . . 18

3 The Importance of Institutions. . . 20

4 Inefficient Institutions . . . 23

4.1 Revenue extraction mechanism. . . 25

4.2 Factor price manipulation mechanism. . . 28

4.3 Political consolidation mechanism . . . 34

5 Political Competition. . . 39

5.1 Political competition environment . . . 39

5.1.1 What is political competition?. . . 40

5.1.2 How is political competition normally carried in economic contest? . . . 41

5.1.3 Does political competition look like economic competition? . . . 42

5.1.4 What is the primary source of political competition? . . . 43

5.2 Political competition meaning - overview of the existing literature. . . 44

5.2.1 Accountability for incumbents . . . 45

5.2.2 Decentralized political authority . . . 47

5.2.3 Electoral politics . . . 49

6 Conclusion . . . 51

APPENDIX A: . . . 54

Chapter 2 Political Competition, Innovation and Growth . Evidence from a Simulated Model . . . . 62

1 Introduction . . . 63

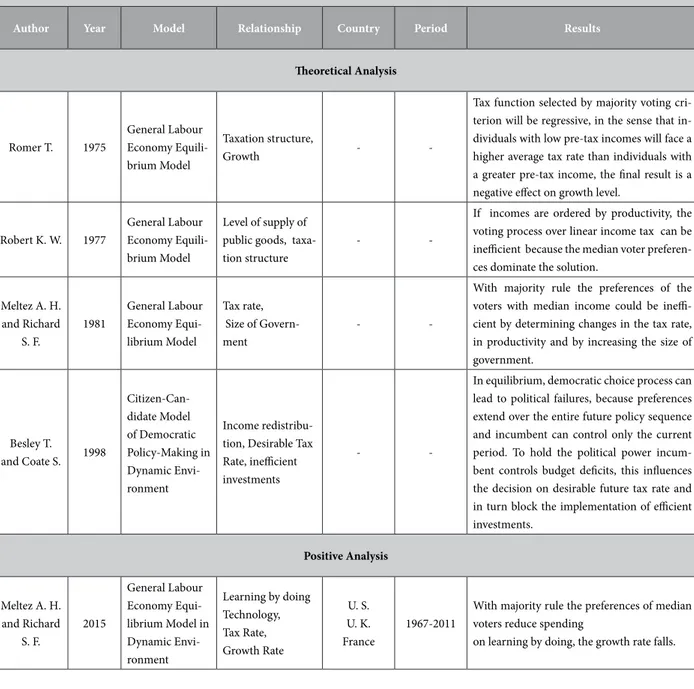

2 Literature . . . 66

3 The Theoretical Framework . . . 69

3.1 The model . . . 69

3.3 Block to innovation . . . 73

3.4 The index. . . 74

4 Extension of the A&R Model . . . 77

4.1 Democratic political systems . . . 78

5 Concluding Remarks. . . 89

List of Tables . . . 91

APPENDIX A: . . . 93

APPENDIX B: . . . 98

Chapter 3 Political Competition and Local Governments’ Performance in Italy Evidence from a Fuzzy Regression Discontinuity Design . . . . 104

1 Introduction . . . 105

2 Institutional setting and data description. . . 110

2.1 Electoral system at the local level in Italy. . . 110

2.2 Data description. . . 112

3 Empirical Setting . . . 114

4 Methodology. . . 117

5 Results: Parametric Approach . . . 119

5.1 First stage . . . 119

5.2 Main results . . . 121

6 Robustness Checks. . . 124

7 Concluding Remarks. . . 128

List of table

Chapter 1

Table 1. Summary table . . . 17 Table A1: main theoretical and empirical contributions - inefficient institutions . . . 54 Table A2: main theoretical and empirical contributions - political competition . . . 59 Chapter 2

Table 1. Summary results by Controlled Distributions . . . 91 Table 2. Summary results by Random Distributions . . . 92 Table A3: Hypothetical Party Constellations . . . 93 Chapter 3

Table 1. Descriptive statistics Full sample. . . 113 Table 2. The impact of Political Competition on Local E. P. (Revenues). Fuzzy RDD. . . . . 122 Table 3. The impact of Political Competition on Local E. P. (Spending). Fuzzy RDD. . . . 123 Table 4. The impact of Political Competition on Local Economic Performance.

Fuzzy RDD with Alternative Measure of Political Closeness. . . 125 Table 5. The impact of Political Competition on Local Economic Performance.

List of Figures

Chapter 2

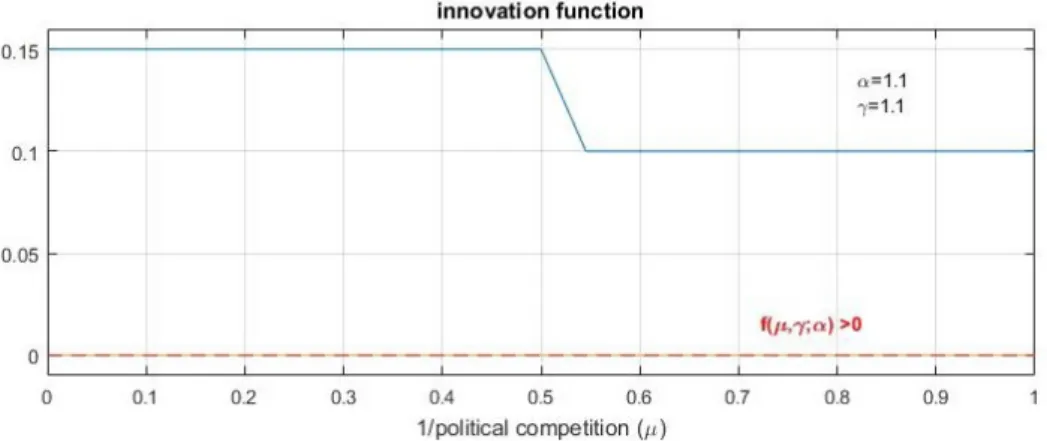

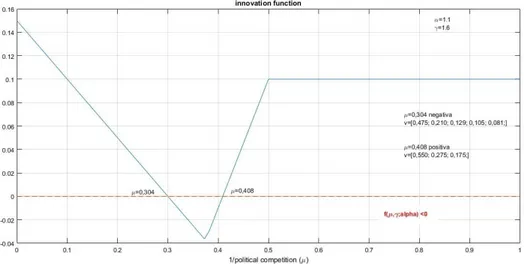

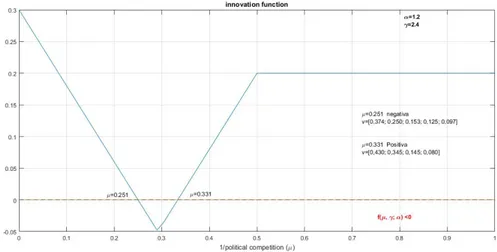

Figure 1. Low level of ruler’s advantage. . . 80

Figure 2. Low level of ruler’s advantage. . . 80

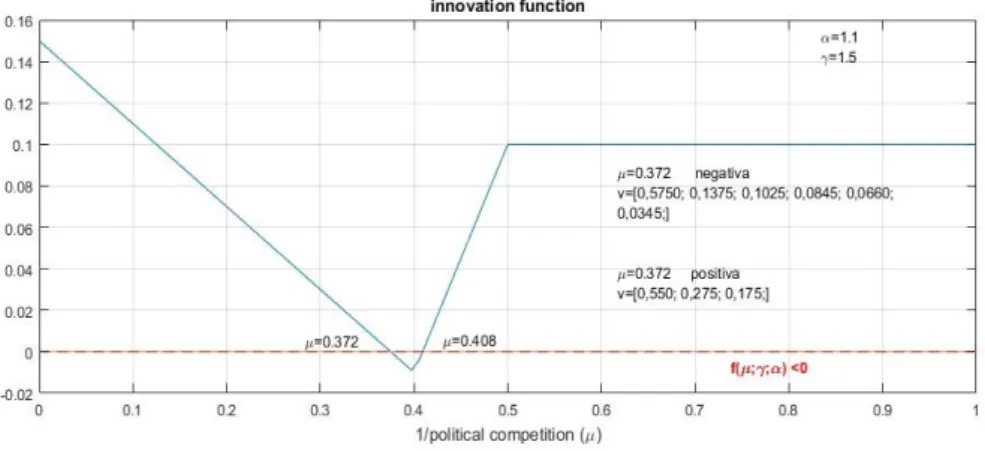

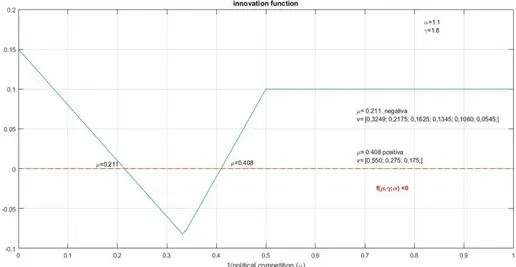

Figure 3. Middle level of ruler’s advantage. . . 81

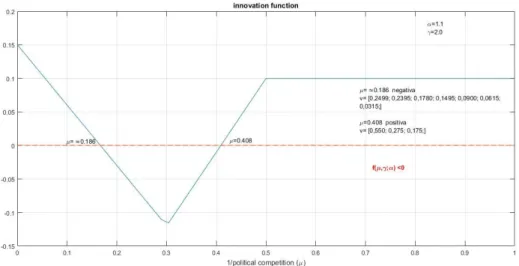

Figure 4. Further increases of the alpha . . . 82

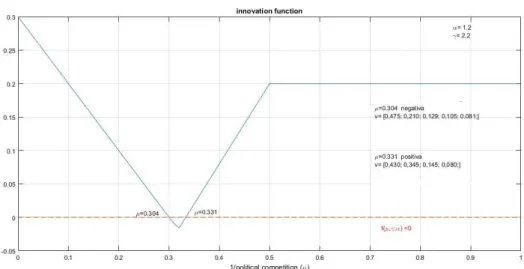

Figure 5. Further increases of the alpha . . . 83

Figure 6. Further increases of the alpha . . . 84

Figure 7. Blocking condition. . . 85

Figure 8. Higher erosion of the incumbent advantages . . . 86

Figure 9. Higher erosion of the incumbent advantages . . . 87

Figure 10. Higher increases of alpha. . . 87

Figure 11. Higher increases of alpha. . . 88

Figure I. Random distribution results.. . . 98

Figure II. Random distribution results. . . 99

Figure III. Random distribution results. . . . 99

Figure IV. Random distribution results . . . 100

Figure V. Random distribution results . . . 101

Figure VI. Random distribution results. . . 101

Figure VII. Random distribution results . . . 102

Figure VIII. Random distribution results . . . 102

Figure IX. Random distribution results . . . 103

Chapter 3 Figure 12. First Stage Result . . . 120

Acknowledgments

I would like to dedicate this work to those who with devotion, patience and tireless support, have “participated” in its realization.

First of all, a special thanks to my professors Maimone and Leonida, for their immense patience, for their indispensable advice and knowledge transmitted throughout the preparation of the paper.

A special thanks to my dear friend and professor Marco De Benedetto who, by helping me to develop a new vision of myself, has allowed me to go beyond my structural limits with his guidance and support as well as practical suggestions for my research.

I cannot omit to infinitely thank mom, dad and my family who have always sustained me in the realization of my projects. I will never stop thanking you for letting me to get here.

A particular thanks to Meco, to my esteemed Serena and to all my friends for being always present in every pragmatic and emotional phases of this course of study. Thank you for listening to my outbursts and for all the moments of light-he-artedness given during my moments of sadness.

I thank my travel companions Valeria N., Simona for having been by my side during this intense period and for enjoying, all together, for our respective achieved goals.

A dutiful and heartfelt thanks to the doctors Enzo Bonfiglio, Davide Borrello, Fabrizio Croce, Marina Dolfin and Piero Merenda for their professional and moral support, in every step of the realization of this elaborate... at the end of this path also for them: “Institutions Matter!”

Thank you all, without you I would never have come this far to complete this work.

Introduction

The economic models that analyze the functioning of market economies assu-me the existence of institutions - not necessarily economic - which are essential for the functioning of the markets, whether they are competitive, oligopolistic or monopolistic. Without these institutions, markets would cease to function or be subject to huge inefficiencies.

In a constantly evolving globalization’s context, the presence of effective and effi-cient governance becomes a strategic necessity for a country and, in this viewpoint, also includes the analysis of the distinctive characteristics. In fact, a well-defined system of property rights, a regulation bureaucracy of markets which guarantees competition, public policies that support social cohesion, political institutions that reduce the risk of social conflicts and/or allow their management, are all institu-tions functional to the economic growth of a country.

The role of institutions in the countries’ development process has long intere-sted and continues to attract the attention of the scientists who belong to different disciplinary fields. There is a growing consciousness among scholars on whether the way societies are organized (in the most common sense their institutions) is the primary cause of their economic performance.

Three different types of theories analyze the institutions’ origins and develop-ment. According to economic theories, institutions are configured as efficient inso-far as the benefits deriving from them, are greater than their cost (Desmetz, 1967) or when they reduce uncertainty and therefore transaction costs (Coase 1937; Nor-th, 1987) or even they are not necessarily created to be efficient but for serving and preserving the interests of some social groups and for generating new institu-tions (Saint Paul, 2000; Acemoglu et al. 2005, 2005). Political theories believe that institutions and policies are introduced for the achievement of benefits by those politically more powerful groups, to consolidate their power and to accumulate resources (Glaeser and Shleifer, 2001); according to Marx, for example, society was divided into social classes and (economic) policies were designed by the dominant

social class, while, modern theories believe that institutions (and policies) are de-termined by sovereigns, bureaucrats, dominant ethnic and religious groups and lobbies. Finally, according to cultural theories, some societies form beliefs or ideas that can lead to economically “good” (efficient) institutions, while others do not (Granovetter, 1985, 2005; Putnam, 1993; Fligstein and Dauter 2007). An example of it, which can become institutions, is the “trust in others” (namely in unknown people) that can facilitate collective actions and, therefore, the institutions that lead to the provision of public goods.

Over the years, the economic theories of development leave the neoclassical paradigm and identify in the different types of institutions (formal or informal, economic or political) “what matter” for the growth dynamic of a nation. For exam-ple, it can be observed how in the planisphere the increases of per capita GDP are concentrated in the temperate areas, far from the equator, so the growth of GDP, according to the economist Sachs (2001), is somehow related to the density of coastal population and is attributable to its geographical factors, whereas, the opinion of Acemoglu, who studied their connection with the national economic development, one of the most cited economists in the field of institutional theories is opposite to. He tries to demonstrate that the economic growth, and therefore the same gap among advanced and developing countries, is due to nothing more than differences between institutions and their histories. According to the author, the political-economic institutional bureaucracy of a country arises as a main and non-competing factor (such are the other factors such as capital, land, labour) of a country’s economic development (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012: “Why Nations

Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty”). Obviously, the exponents of

these theories are often compared each other not because their respective theses are not supported by any evidence, but because they unsatisfactorily reduce the complexity of reality, leaving out of their capacity to explain those behaviours that, however, represent the basic postulates in other theories.

Whether or not they are the main or transversal cause of growth, several viewpoint agree by establishing that “the inadequacy” or low resilience of

insti-tutions with a change of environmental conditions or about power relationship among social groups, does not support technology investment, skills and knowle-dge which are essential to produce the desirable results. One of the primary causes of institutional inefficiencies can be precisely found in the changes in power rela-tionships among social groups where the desire of an internal resource redistribu-tion from the political groups in power leads to the implementaredistribu-tion of distorting policies, causing the emergence of institutions that limit growth and improve social inequalities. The conflict among the groups encourages society to bring out politi-cal institutions which, through inefficient policies, will be long consolidated even if in the system alternative and better policies coexist. This conflict takes place mainly in the arena of political competition, the latter is therefore the key element in the analysis on a system’s institutional arrangements efficiency.

The literature, by analyzing political competition’s costs and benefits, underlines its crucial role in the institutional process which leads to the policies and beha-viours necessary for the realization of investments, technologies, skills and other productive factors pro growth (see e. g., Downs, 1957; Wittman, 1973; Hamilton

et al., 1966; Acemoglu and Robinson, 2006, Beasly et al, 2006). Various authors

explain how political competition has a different impact on economic results, in fact, the presence of distorting policies preferences in order to strengthen political power positions and economic rents, the information asymmetry between citizens and representatives, the distributive conflict between groups of citizens and the pu-blic investment opportunities features, explain a distorting effect through the po-litical process that can culminate in the creation and consolidation of institutions which block the development and economic growth of a nation.

The innovative assumption of this work aims to propose a further interpretative key, even though parallel and complementary to the previous ones used: to set up, describe and analyze the institutions’ performances and in particular those legal and political ones, in order to sharp the features in a first theoretical domain, which may lead to a non-optimal system output. In this discussion, political competition represents both a proactive base and a tool to empirically investigate the

territo-rial reality in which administrators and policies are in time and space connected by reflecting the socio-economic models of the geographical areas examined. The interest about the topic of institutions and political competition among groups, has contributed to identify the core of the work itself, namely the “responsibility” and how the optimal development of a country can be invalidated by its variations and implications. It is precisely from the definition of political competition that we start to glimpse the transposition into institution of the individual dimension and the consequences of an action which is implemented in the human case as well as in the institutions, and that declines its effects through a decision. Studying politi-cal competition is useful to shape as the mixing of some subjective and normative requirements and the presence of altruistic or opportunistic purposes are able to “humanize” the institutional system, leading it towards dynamics capable or not to improve the social well-being. One of the goals of this work is, therefore, the capa-city to pop the question on how, under some circumstances, the interests conflict among power groups that become multitudes (institution), may become a set of policies set up to configure a high-performance economic system.

In the first chapter the debate on the importance of institutional quality in eco-nomics, which is still more than heated, will be examined: several opinions lead to different studies with different and never definitive results. However, what is certain is that it is no longer possible to underestimate the extent of this phenomenon: a healthy institutional economic environment may only encourage a country growth and on this point, all economic literature agrees. In fact, despite the differences we will find among the mentioned scholars, there is no denying that the economic institutions of a country evidently represent an attraction for foreign investments, investments that are always generative of economic growth. Thus, the problem is to identify how direct this impact is and then, how much part of the economic growth is attributable to improvements in the institutional domain.

In the second chapter, we highlight the potential characteristics of party systems that could lead the political institutions to adopt inefficient public decisions. Our investigation relies on the theoretical analysis proposed by Acemoglu and

Robin-son (2006) that paid particular attention on the effects of political competition in public decision-making processes on the adoption of innovations. We aim at sha-ding a light on the relationship between political competition and the economic backwardness factors of countries. The main contribution is the introduction of a measure of the “effective number of parties” in the aforementioned model in order to bring out the “potential” structure of a political system that can lead to economic backwardness.

Finally, in Chapter 3 we add to the recent theories of political economy, showing that political competition positively affects the quality of politicians in office, empi-rically investigating the effect of political closeness on the economic performance of governments using electoral and budget data of municipalities in Italy. In order to solve potential endogeneity issues, such as the reverse causality, we exploit an exogenous source of variation in the population size nearby the threshold of 15,000 inhabitants. In fact, as stated by the Italian Law, municipalities with a population size above such cut-off vote under a dual-ballot system, whereas in cities with a population below the threshold of 15,000 inhabitants elections are held under a sin-gle-ballot scheme. Knowing that the political competition, as measured by (1) the number of parties/candidates running at elections and (2) the percentage vote mar-gin between the two best parties/candidates, is affected by the electoral system and that the latter discontinuously change in proximity of the aforementioned cut-off, we rely on both a parametric and non-parametric (local linear regression) Fuzzy Regression Discontinuity Design and find a positive causal impact of political clo-seness on economic policies, both revenue and spending related, that might affect the economic performance of local governments.

Chapter 1

The Determinants of Inefficient Institutions:

A Review of the Literature

Abstract

Institutions are the central driver of the economic growth of a country. Despite some countries abound in terms of natural and human resources, they are usually characterized by a high level of poverty, a low level of deve-lopment and a high economic inequality. The equilibrium theory emphasizes how inefficient political institutions consolidated in some countries, through distortions, explain why some countries are not able to adopt policies that - optimizing the use of tangible and intangible resources of the country - in-crease the collective welfare and boost the economic growth. Public decisions in adopting efficient policies are more present in democratic systems, cha-racterized by a high level of political competition.In turn, the actual level of political competition of a country is determined by the “rules governing the political game”, i.e. by political institutions. Finally, political competition leads to a trade-off between costs and social benefits which depend on the public policies implemented. They are largely considered as the final outcome of the political process that can culminate, because of various distorting factors, in the adoption of policies blocking the development and economic growth of a nation. This work presents the main literature on the causes of inefficient institutions and connects this line of analysis with the political competition literature in order to highlight how institutions “that govern the game between the parties” in the political system, through political competition will lead to the ‘adoption of inefficient policies that negatively affect the economic growth and the well-being of a country.

JEL Classification: D02; E02; O43; O44; D72

Keywords: Institutions, Inefficiency, Economic Growth, Political Compe-tition.

1 Introduction

This chapter connects the literature about the causes of inefficient institutions with the political competition one in order to highlight how, through the channel of political competition, political institutions that govern the game between the parties will lead to the adoption of inefficient policies which affect the economic growth and performance as well as the well-being of a country. The purpose of the paper is to provide a unified literature review that organically and clearly illustrates various issues already raised in the existing literature as well as a number of mecha-nisms which seem to be important in understanding inefficient institutions.

In the first part of this paper, the importance of institutional features for eco-nomic growth is briefly explained. Further, the main problems faced in the study of efficient institutions as e.g. the meaning of institutions and their nature or their stability over time are presented. In this section we reorganise and present the lite-rature by using the three main causes of institutional inefficiency as a classification criterion. Based on the revenue extraction, factor price manipulation and political consolidation mechanisms as causes of inefficient institution, various charters are here exposed and analysed.

In our work the “Social Groups Conflict Theory” takes on the value of the main criterion of analysis of the factors and conditions that lead to the birth and con-solidation of inefficient institutions. In this framework the sources of inefficient institutions can be explained by considering a society made up by different groups in which some groups have for anti-growth policies preferences where the final equilibrium is determined by interaction among “power groups” (Besley, Persson and Sturm, 2010; Kuran, 1987; Bates, 1981). The conflict among groups takes place mainly in the arena of political competition which is in our study a key element to evaluate the efficiency of a system structures as well as its final output. For this re-asons the rest of the paper investigates how political competition determines inef-ficiency in policies which in turn are translated into inefficient institutions. Accor-dingly, the second section of this chart is dedicated to the investigation on political

competition as a source of inefficient institutions. Furthermore, in order to analyse and organize the literature on political competition, the three main channels throu-gh whom political competition influences the level of efficiency of the institutions are identified and explored.

Starting with our study on political competition it emerges how in a context in which political institutions determine the framework for public policies placing constraints on them, if the groups in power tend to implement distorting policies extracting resources from the rest of the society, they will adopt inefficient eco-nomic institutions to support these policies. As a consequence, even if alternative and better policies coexist in the system, this kind of preferences will determine the persistence of inefficient political institutions where this term encompasses any elements, procedures, rules, strategies, which confer political power on the ruling elite.

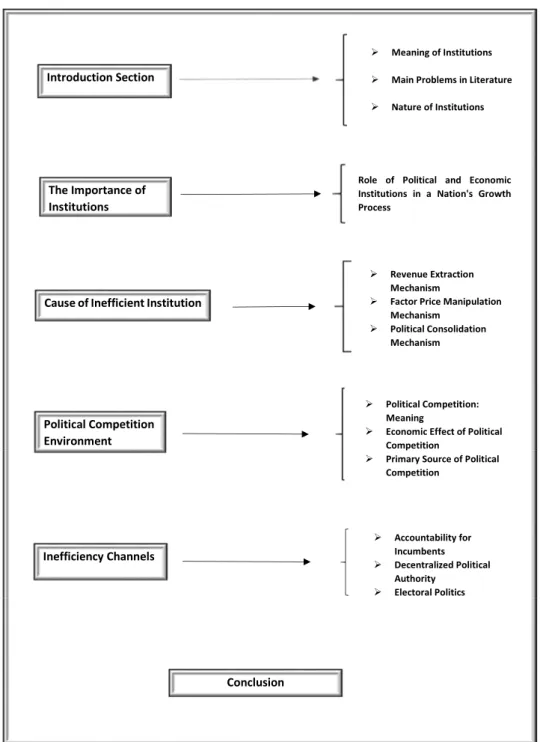

Introduction Section

Meaning of Institutions Main Problems in Literature Nature of Institutions

The Importance of Institutions

Role of Political and Economic Institutions in a Nation's Growth Process

Cause of Inefficient Institution

Revenue Extraction

Mechanism

Factor Price Manipulation

Mechanism Political Consolidation Mechanism Political Competition Environment Political Competition: Meaning

Economic Effect of Political

Competition

Primary Source of Political

Competition Inefficiency Channels Accountability for Incumbents Decentralized Political Authority Electoral Politics Conclusion

Table 1 . The following Table summarizes the most distinctive sequences of the argument analysed .

2 Meaning of Institutions

A large body of the literature analyses the determinants of economic growth from different perspectives. Some scholars (see e.g., Wilson J. Q. and Banfield, 1964), according to neoclassical theory highlight the importance of capital accu-mulation where saving plays a crucial role, but also human capital and techno-logical channels are identified as main determinants of development. Subsequent works (see among others, Putnam et al., 1993; Huntington, 1996; Nee and Ingram; 1998), related to this argument, stress the role of institutions as determinant of economic growth.

This line of research has been widely analysed by many social and economic scholars: if on the one hand neoclassical economists have been indifferent of insti-tutions’ role on the country growth path, on the other hand pioneers of the econo-mics of institution have had to face some sorts of problems, such as the univocal definition of institutions (Rodrik, 1999; North, 1991; Ogilvie and Carus, 2014; Ho-dgson, 2004; Rutherford, 1995; and so on ), the identification of measures related to institutions (Ogilvie and Carus, 2014; Acemoglu et al., 2001, 2005; Rodrik et al., 2004) their stability over time, and some other classes of issues.

First of all, what does institution mean? As North (1987) said, institution is “a

set of rules, compliance procedures, and moral and ethical behavioural norms de-signed to constrain the behaviour of individuals in the interests of maximizing the wealth or utility of principals” (North,1987,p. 201-202). Ostrom (2005) has defined

institution as “a broad term encompassing three types of statements, i.e. rules, norms,

and shared strategies. These statements describe opportunities and constraints that create expectations about other actors’ behaviour. In other words, an “institutional statement” encompasses a broad set of shared linguistic constraints and opportunities that prescribe, permit, or advise actions or outcomes for participants in an action situation” (page138). Finally, Rutherford (1995) defines institutions as “particularly

pro-posals: “a regularity of behaviour or a rule that is generally accepted by members of a

social group, that specifies behaviour in specific situations, and that is either self-poli-ced or poliself-poli-ced by external authority” (Rutherford,1995, page 182).

Hence, Rutherford (1995) defines institutions as the set of rules that people use to structure their interaction in every different life’s circumstances: family, school, associations, and governments and so on; obviously several consequences for pe-ople who interact each other come from behavioural rules. Therefore, in different environments, institutions assume specific functions, i.e. conflict resolution and coordination (see Acemoglu et al., 2005), administration of common property re-sources and administration of justice (Besley and Person, 2011), while Hodgson (2004) highlights another aspect of the meaning of institution that is considered as “repositories of knowledge, internal norms, customs and traditions, that agents form

and that regulate their behaviour”.

The second issue that scholars face is clearly to define the nature of institutions: in the literature it is possible to find a conspicuous list of definitions. Institutions are defined as formal institutions - codified rules, i.e. in the constitution - and in-formal institutions, related to how in-formal institutions are used, to distribution of power, social norms, and equilibrium (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012). This sort of distinguishing is useful to explain why formal institutions as constitutions in U.S. and many Latin American countries are similar, but the practice of politics, and constraints on presidents and elites are very different. Furthermore, institutions are split into economic institutions, i.e. property rights, contract enforcement, or con-tracting possibilities, and political institutions, i.e. form of government, constraints on politicians and elites, separation of powers, etc. In this field, many authors foca-lize their attention on how political institutions affect economic policies (Persson

et al., 2000; Persson and Tabellini, 2004).

Besides, some authors distinguish institutions from organizations, in fact in North’s analysis (1991) an institution is defined as a body or organization with own members or constituents. Finally, a conspicuous body of literature (see among others, Rodrik, Subramaniam and Trebbi, 2004), highlights the differences between

institutions and policy, identifying an institution as the cumulative outcome co-ming from the implementation of past policies. Key contributors to this branch of literature (e.g., Besley, Persson and Sturm, 2005, 2010; Williamson, 2000) include electoral rules and legislative regime that have systematic effects on public policy outcomes such as government spending and conversely on institutions quality.

This dichotomy (institution vs policy) is problematic since it does not work well when it is necessary to identify the mechanism through which both determine in-centives for growth, and in this perspective, it is necessary to consider institutions and policy together (Acemoglu et al., 2001).

3 The Importance of Institutions

After briefly introduced in the previous paragraph the main topic that will be discussed in this work and the difficulties in defining institutions, now we move toward the main issue of the analysis related to the relationship between political institutions and growth: if political and economic institutions are the fundaments of growth, why do we observe different levels of country development? This key question comes from the recent literature (NIE) on institutional economics analy-sis of countries’ long-run growth. This field of study is based on two cornerstones as the Coase’s works (1937, 1960) and Williamson (1975) development work of Coase theory. The first author has declared the importance of contract between private parts in order to solve inefficient allocation’s problem of resources and the necessity of institutions to identify and enforce property rights when externalities are generated.

Coase stressed the crucial connection between institutions, transaction costs and neo-classical theory. The literature growing out of the Coase theorem similarly suggests that even when there are externalities, bargaining among those involved can generate socially efficient outcomes hence in this perspective, institutions play a crucial rule by initially assigning the property rights among the parties. William-son’s work (1975) has focused on concepts of transition costs and property right

as causes of inefficiency and in his recent article (2000) he develops a level dia-gram analysis where he explains as informal institutions arise and are maintained.

“Given these evolutionary origins, they are “adopted” and thereafter display a great deal of inertia-some because they are functional (as with conventions); others take on symbolic value with a coterie of true believers; many are pervasively linked with complementary institutions (formal and informal), etc.” (Williamson, 2000, p.598).

The evolutionary processes bring to institutions - that could create opportunities - as the executive, legislative, judicial, and bureaucratic functions of government and they are able to enforce property rights and contract laws that are important features for the economic productivity of a system. Another important contribu-tion in terms of institucontribu-tions is due to North (1991,1992; North and Thomas, 1973; North et al., 2009); in his major contributions, he moves from neoclassical point of view - focusing on technology as crucial element of growth - to institutions as economic development’s determinant and stresses the macro-level importance of institution as growth’s factor. His recent study is interested in the determinants of institutions and analyses conditions in which institutions emerge and evolve and why often they are not efficient:“…In fact, we have incomplete information and

limi-ted mental capacity by which to process information. Human beings, in consequence, impose constraints on human interaction in order to structure exchange. There is no implication that the consequent institutions are efficient. In such a world ideas and ideologies play a major role in choices and transaction costs result in imperfect mar-kets. The place to begin a theory of institutions, therefore, is with a modification of the instrumental rationality assumption” (North et al., 2009, page 73).

In the framework of studies that leave the instrumental rationality assumption, and bring out the inefficient features of institutions, there are several interesting pu-blications, such as Acemoglu and Robinson works’ (2012; Acemoglu et al., 2005, 2005, 2008;) that underline as politics and political institutions may be identified as a cause of inefficient institutions and the dominant political coalition plays a crucial role in this direction. Other scholars as Besley, Persson and Sturm (2010) show as a lack of politi-cal competition may lead to policies that preserve economic growth and document a

strong link between low political competition and low-income growth.

In the previous works it emerges that if it is true that institutions generate growth, from another point of view, they could determine economic backward-ness. There is an extensive literature which explains the different factors that cau-ses backwardness, starting with Alesina and Rodrik (1994), Persson and Tabellini (1994) works that identify in the high taxation the disincentive to invest. Persson and Tabellini (1994) state that in a society where distributional conflict is impor-tant, political decisions produce economic policies that burden both investment as well as growth-promoting activities in order to redistribute income and find that there is a large negative relation between inequality and growth. This relation is only present in democracies.

Lancaster (1973), Alesina and Perrotti (1993) affirm that uncooperative distri-butive conflict reduces investments and growth. Benhabib and Rustichini (1996), despite the predictions of the neoclassical theory of economic growth, observe that poor countries have invested at lower rates and have not grown faster than rich countries. By using a game-theoretic model of conflict between social groups over the distribution of income they study how the level of wealth and the degree of ine-quality affect growth when the incentives to domestic accumulation are weakened by redistributive considerations.

In particular, they analyse the relationship between politics and economic growth and look at conflict among agents endowed with varying capital/labour shares, finding that policies which maximize growth are optimal only for a govern-ment that cares solely about pure “capitalists.” The greater the inequality of wealth and income the higher the rate of taxation, and the lower the growth. Their results show that inequality in land and income ownership is negatively correlated with subsequent economic growth.

Furthermore, Olson (1996) sustains that institutional modifications are neces-sary for development. He investigates the difference in terms of growth among countries and shows as the poorer countries do not have institutions giving a structure of incentives that leads to the productive cooperation; by contrast, these

institutions favour the interests of a limited number of subjects. “The structure of

incentives depends not only on what economic policies are chosen in each period, but also on the long run or institutional arrangements: on the legal systems that enforce contracts and protect property rights and on political structures, constitutional pro-visions, and the extent of special-interest lobbies and cartels” (Olson, 1996, page 6).

Finally, political interest groups is another branch investigated in the literature, according to which political groups block the development to protect their intere-sts. In the context of development economics Kuznet (1968), Olson (1982), McGui-re and Olson (1996) and Acemoglu and Robinson (2000) sustain that the develop-ment of political blocks depends on interest conflict between groups in the society that could determine the emergence of inefficient institutions.

4 Inefficient Institutions

As mentioned above, institutions have become more important in the literature and their impacts on economic development and social wealth has widely analysed from different perspectives. In this framework some authors (see among others, Benabou, 1996; Besley, Persson and Sturm, 2010; Kuran, 1987) have tried to explain why inefficient institutions emerge and persist. This mechanism can be explained by considering the society made up of different groups in which some have the pre-ferences for anti-growth policies and, final equilibrium will be determined by inte-raction among “power groups”. In this environment it is possible to identify various causes which determine institutions that could lead to economic backwardness and low growth. For example, Kuran (1987) tries to explain how some institutions - that could carry out not optimal outcome - persist over time. He shows that collective decisions are path-dependent, and they are influenced by previous policy decisions. The work is based on observation that due to group pressures, people’s policy pre-ferences express in public often differ from those they hold privately, so the possi-bility of preference falsification (free-riding) - given the initial expectations - leads to multiple equilibrium distributions of public preferences, each associated with a

different policy. The paper sheds a light on why a policy that a few people (power groups) support privately, will be accepted publicly and why, once this policy is in place, the degree of private opposition will decrease. This mechanism supports the claim that societies retain many policies they would rather change: except in special circumstances, an interior equilibrium of strategic interaction will lead to a corner equilibrium that is persistent and it is immune to endogenous private-preference adaptations.

Besley, Persson and Sturm (2010), have found a non-monotonic relation-ship between the level of political competition in the systems and the adoption of growth’s policies. The scholars by using the political competition in the pre– election period, show that the preference for special-interest policies of a small group of electors, rather than, electors’ policies growth preferences, could bring the system to adopt policies which distort economic decisions and lower overall inco-me and transfer resources to one group of citizens. Bates (1981) explains how soinco-me governments adopt different distortionary policies that reduce prices for agricultu-ral productions. In his work he explains how African governments adopt policies that increase the protections level of manufacturing sectors in which they have shares. If these policies increase workers’ salaries, they decrease profits of the go-vernment ownership, hence there is an ambiguous relationship between employees of the new manufacturing sector and governments. So governments in order to maintain their profits at a high level, adopt measurements – i.e. ensuring low-cost foods - that reduce urban costs of living and hence diminish the demand for higher nominal incomes. These policies have had significant effects on both the income level as well as on the distribution of incomes and in turn the rural producers are definitely affected by the conflict between governments and workers.

In these models the cause of inefficient institution could be split in three main classes: the first relates to the revenue extraction mechanism, and represents a di-stortive tool for transferring resources among groups; the second is focalised on

factor price manipulation mechanism, and explains how the groups in power

reducing factor price; finally, the mechanism of political consolidation shows how groups in power tend to reduce the profit of the other classes in order to maintain their positions and rents over time (see Appendix A).

4.1 Revenue extraction mechanism

Revenue extraction mechanism focuses on the group in power’s ability to ex-tract resource from the productive groups. The literature on this subject has been widely increasing since seventies. In a general labour economy equilibrium model, Romer’s work (1975) focuses on the determination of a linear tax function parame-ters by using the social choice criterion know as majority voting adopted in every democratic society. This analysis carries out the conflict of interest between higher growth and equity distribution that could be thought as a conflict between rich and poor groups, and shows how the choice mechanism could determine an inefficient taxation structure with negative effect on level of growth. The model considers pe-ople with different level of ability and utility function correlated with their skills, and shows that if the skill distribution is toward to high skill levels, “then the

majo-rity-voting equilibrium tax rate will be the lowest permissible value of tax rate. In this case, the voting equilibrium will result in the choice of a tax rate which, among all permissible tax rates, minimizes the well-being of the ‘poorest’ individuals who are those with low ability. In other words, the tax function selected by majority voting will be regressive, in the sense that individuals with low pre-tax incomes will face a higher average tax rate than that of individuals with a greater pre-tax income” (page 177).

Another theoretical model that follows Romer’s point of view has been developed in Roberts’s paper (1977) where provision of some public goods and voting over linear income tax schedules are considered. The author points out that although it seems impossible that choices made in the public sector are the outcome of some voting process, however, if political parties make choices in order to maximise the likelihood of being elected then it is possible to see how the choice is determined someway, by a voting process. The use of a model of linear taxation is present in both works of the two previous authors. Romer (1975) restricts the analysis only

to the presence of a lump-tax in the utility function of the group and analyses uni-modality problems of using a linear tax and predetermined government spending, meanwhile Roberts (1977) expands the preferences of groups also to consumption of public goods by using a linear tax and a predetermined budget, and shows that the median voter dominates the solution if incomes are ordered by productivity. Meltez and Richard (1981) in their analysis considers also the size of government (measured by the share of income redistributed). In a general labour equilibrium model, the size of government is determined by majority rule. Their hypothesis implies that the size of government depends on the relationship between mean in-come and the inin-come of the decisive voter. In this model the decisive voter chooses the tax rate that maximizes his utility and with majority rule, the voter with median income is crucial, in fact, his preferences through the mechanism of voting rules could determine changes in the tax rate, in productivity and in size of government. In taking a decision, he knows that his choice constraints everyone’s decision. Any higher tax rate decreases the total income, tax collections and the amount available for redistribution. In the model the principal causes that determine an increased size of government are extensions of the franchise that change decisive voter’s po-sition in income distribution, variations in relative productivity and an increase in mean income relative to the income of the decisive voter increases the size of government.

Moreover, Meltez and Richard (2015) extending the previous work and taking into account a linear income tax with tax rate defined in a sequence of single issue election where the median individual productivity is decisive for the final choice. If the economic growth is the result of using a learning-by-doing technology, and an exogenous factor could determine an increase in technological specialization, then voters can raise the equilibrium tax rate and reduce growth: so higher taxes discourage labour causing the growth rate of the economy to fall.

Besley and Coate (1998) look at efficiency of policy choice in representative de-mocracies in a dynamic environment. They show that by using democratic process, the equilibrium policy choices - conditional on future policies - in each period is

efficient. In any case, if it is true that there are not any alternative current poli-cy choices which can improve the expected utilities of all citizens, these policies - that would be declared efficient by standard economic criteria - are not neces-sarily adopted in political equilibrium. So, this result could be labelled as political failures. The scholars stressed how inefficiency arises because preferences extend over the entire future policy sequence, while policy makers can control only what happens in their current term. In this framework, political power is delegated to particular citizens and there is competition through the electoral process, in order to acquire this power. In every period of time the citizen who won the political competition defines the parameters of the tax system, and also the first-place can-didate could make the final decision if he implements the public investment. The incumbents in power use the budget deficits to manipulate the choices of future policy makers who have different policy preferences, policy is distorted because current policy choices affect which political party will win in the future and this represents a determinant of political failure. Another determinant is identified in public investments that could not be implemented if they change the identity of future policy makers in a disadvantageous way to the current incumbent: by chan-ging the income distribution, a public investment can alter the desired tax rates of future policy makers. Such changes can deter an incumbent from undertaking an investment.

All these citied papers stressed how some groups are able to implement ineffi-cient policies or adopt not effiineffi-cient mechanism of policy choice in order to extract revenue from other groups. The groups in power in order to maximize their utility function, define a tax rate that diverge to the tax rate necessary in order to maximi-ze the output. Usually, the inefficiency emerges from the absence of tax instrument as the lump-sum taxes, disposable to the group in power, that are not distortive. All these works analyse the potential source of inefficient institutions by using equili-brium model. In this environment of understanding why an institution is ineffi-cient it may be necessary to define the meaning of inefficiency by considering the theoretical Pareto concept: an institution could be inefficient if there is another

possible institution available that could determine a higher level of well-being for everyone, but in every paper analysed above, it has emerged that the equilibrium set of institutions if, on the one hand, enriches a particular group of people, from the other hand, causes economic backwardness and reduces growth for the entire society. In conclusion, while an equilibrium model exists this does not imply that policies or institutions are efficient according to standard economic criteria. 4.2 Factor price manipulation mechanism

This mechanism underlines that not always institutions protecting property ri-ghts of producers are efficient in terms of long-run economic performance.

Factor price manipulation mechanism explains as in a competitive environment the different groups concur to obtain production factors. In this set of models the group in power could be able to impose taxes on the productive groups in order to ensure a lower price for productive factors. The cause of inefficiency comes from this competition. As previously mentioned, an interesting explanation about how this mechanism works has been provided by Bates’s chart (1981) in which the groups in power adopt entry barriers and restrictive policies in order to affect the factor prices. The scholar analyses how government (group in power) in order to increase his profits in commercial sector – by reducing the labour costs - adopts not efficient low-cost foods’ policy that negatively impacts agricultural productions, with distortive consequence on income and growth. Also, in Acemoglu (2003) the elite uses entry barriers to reduce the price of production factors. The work stressed on two main policy distortions: taxation represents the distortion channel through which income is redistributed from entrepreneurs to workers and in turn it reduces firm’s investment, meanwhile, entry barriers is the channel through which income is redistributed from workers to firms and decreases the wage, labour employment and in the end distorts the allocation of resources because it reduces the entry of more productive agents into entrepreneurship. The scholar compares two different systems: populist democracy where political power is held by a large group of poo-rer agents, versus oligarchy where the political power is concentrated between few

entrepreneurs. The ratio of the model is the following: in oligarchy the main pro-ducers use political power to reinforce their property rights through entry barriers that allow them to create monopoly conditions for themselves, so they violate the property rights of potential future producers. Otherwise, in populist democracy, the poorest agents use their political power to tax the profits of businesses; more-over, the productive class is not able to create entry barriers to new entrepreneurs, and this means better property rights for future potential producers. This model shows that when the taxation is low, and the distortions caused by entry barriers are low, oligarchy is more efficient than populist democracy, but when taxes are relatively low and entry barriers create significant improperly resources’ allocation, democracy gives high aggregate output. Finally, the scholar has showed as in two identical societies that one with an oligarchic organization will first become richer, but later will fall behind the democratic society.

Another chart that analyses how factor price manipulation mechanism works, has been written by Krussel and Rios-Rull (1996). The authors claim as the conflict emerges between old and new technologies where the “vested interests” that are re-sidual claimants of the currently operated technology, try to block the emergence of superior technologies through political process. By using political-economic equi-librium theory in dynamic models - in which agents vote every period and have to decide if remain unqualified workers over their lifetime or accumulate human capi-tal and become managers in the end of their career – they show that vested interests are responsible for veto of technological innovation and its adoption is the result of permanent tension in the political process between agents with different skills. The growth opportunity related to new technological adoption is always possible, and due to current distribution of agents’ properties over capital specialization. The authors highlight as trade barriers, high capital taxes, etc., work in a human capital model that analyses both the process of adoption of new technologies, and the way it interacts with the distribution of agents across age, as well as political process. The equilibrium draws a long cycle of stagnation and growth and over this cycle, incumbent innovators have political power, so new technologies are banned, and

new innovation will be adopted only when these incumbents exit the economic system. The cycle of stagnation and growth is an example of how innovation itself creates vested interests and, as a consequence, a long period of technological and economic stagnation.

Parente and Prescott (1999) emphasize the factor price manipulation mecha-nism by focusing on monopoly rights, and show how this sort of property right limits the entrance in the sector to a group of potential adopters, because it could increase costs to enter the industry with a superior technology. The final result is an equilibrium outcome characterized by the adoption of inferior technologies used in inefficient way. The authors show as the state can use different policies to protect a group of labour suppliers - which provide specialized work to any company that uses a particular production process in every sector of the economy, for example by prohibiting firms in the industry from implementing changes in work practices that would increase productivity and reduce employment. In this framework every firm in the sector that use the existing technology must employ skilled coalition members and has to pay the salary set by the coalition. Finally, the coalition has the right to limit the number of membership.

In order to explain how the monopoly rights, block the economic progress, the scholars have used a dynamic strategic game between the coalition of factor sup-pliers who have the monopoly rights over the current production process and a potential entrant. If there is an entry, entrant uses a superior technology. Because the rights of a coalition are protected, a group of potential adopters must over-take resistance of coalition before it can use the superior technology; obviously, this will determine some costs - correlated with the coalition size - , but after, the new better technology becomes available for every firm that operates in the sector, determining in turn a free-riding issue. In conclusion, the capacity of a particu-lar group to earn monopoly rent by blocking the adoption of higher technology depends on the cost of resistance, for this reason it supports policies that ensure monopoly-rights arrangement wiping out the free-riding problem associated with overcoming resistance and determining inefficient political equilibrium solution.

Nugent and Robinson (2002) show how the different forms the coffee economy took at the beginning of the last century were critically determined by the legal environment determining access to land, and by differences in the nature of poli-tical competition.In their work the factor price manipulation mechanism passes through the adoption by elites of laws that favour landowners in order to exercise the monopsony power in the labour market, thus reducing costs. They have used a comparative economic analysis of the development of coffee exporting economies in Latin America to underline the origins of differential institutional development. While the group with political power in some countries protected efficient and egalitarian smallholder economies, in other countries it has created inegalitarian plantation societies. The two scholars stressed as the country’s endowments are not the main determinants of the growth, but what matters for the institutional structure and thus development is conditional on the form that political compe-tition takes in society. They argue that the coffee society’s organization impacts on growth development as follows: the smallholder production is generally more efficient than plantation production of coffee. In fact, the monopsony power of plantation owners creates a hold-up problem: owners do not want to pay a wage above the subsistence level so, there is not incentive to accumulate human capital. Smallholders have much better incentives to accumulate human capital because they can capture part of the return. The elite in power (that could be represented by merchants rather than landowners) - through the political competition mecha-nism – could adopt laws that protect the land right or differently could adopt laws that expropriate landowners. The result of this political competition could lead to efficient on not efficient institutions.

Another paper that analyses how the conflict between groups in power and the productive class leads to inefficient institutions is that of Galor et al. (2003) which contextualizes the factor price manipulation mechanism considering the conflict between agricultural and capitalist groups. They compare the economic growth of different countries with different levels of land concentration and suggest that diffe-rences in the evolution of social structures across countries may reflect diffediffe-rences

in land abundance and its distribution. Their main hypothesis is that land inequali-ty adversely affects timing of education reform and stress how geographical condi-tions and institucondi-tions are closely linked. The human capital is a key factor of diffe-rences in growth about the countries and it is less complementary to the land than the capital. Hence, the capitalists are beneficiaries of the accumulation of human capital by the masses, therefore, they have incentive to financially support public education that would sustain their profit rates and would improve their economic well-being. Differently, landowners have no incentive to support pro-growth edu-cation policies as long as their participation in the industrial sector remains limi-ted. In fact, human capital has not brought large benefits to primary sector, given its low degree of complementarity with the land factor: public investments in human capital have pushed labour costs above the average productivity of this sector. The final equilibria of the economic system is characterized by a level of investment in sub-optimal human capital mainly due to imperfections of the capital market and the effective level of public investment in human capital. The scholars have used a dynamic deterministic model where public expenditure in education is financed through a linear tax: in equilibrium the optimal tax rate that gives the optimal level of public investment in education maximizes both aggregate output, wages and the return on capital, but does not maximize the rent of land ownership that had a higher level of land concentration. Consequently, if the land ownership’s degree of participation in industrial sector is low, probably policies that block the growth de-velopment could be adopted, but when this degree of participation increases - thus, the costs to finance education policies decrease with respect to the profits of the landowners - changing in turn the land ownership preferences toward educational investment. A similar framework is developed by Bourguignon and Verdier (2000) who explain how the conflict between aristocracy and middle class determines inefficient institutions by considering the underinvestment in education.

In their model the aristocracy is interested in strategically ‘‘promoting’’ an edu-cated middle class that both accelerates economic growth as well as minimizes the danger of future expropriation and increases their rents. The authors use a dynamic

model where the political participation is exogenous and depends on education level. Initially, individuals must make a decision on whether they get educated or not. There are two types of returns to education: private return amounts and public return represented by educational externality. Furthermore, there are two sources of cost: the taxation for subsiding educational policies for the lower class and the cost of weakening the future political power of the oligarchy because new voters will appear in the future. In order to avoid a net loser in this process the autarchy will choose to educate a number of poor which will not change the voting majority, or the median voter, so, the elite will both retain political power and rents from educational externality, but this choice will not be efficient because it reduces the growth rate. Finally, in the field studies of inequality, institutions and growth, Sonin (2003), by using a microeconomic approach, highlights as the presence of imper-fections in public institutions that ensures protection of individual property rights, encourages rent-seeking behaviour: the rich groups are opposed to institutions in providing protection of property rights to poor groups, and the presence of econo-mies of scale in private protection, enables rich groups to get a significant advanta-ge over the poor groups. The final result will be characterized by an economy that becomes blocked in a bad equilibrium with low growth rates, high inequality of income, and wide-spread rent-seeking.

All these mentioned works show how in different scenarios, groups in power adopt choices that involve the manipulation of public policies or economic condi-tions as a strategy for ensuring themselves a lower factor price and higher profits by reducing the well-being of the other groups. These strategic choices could nega-tively affect the efficiency of the institution and, consequently the growth develop-ment. In conclusion, the factor price manipulation mechanism - in order to reduce factors demand from the other groups so indirectly to benefit the groups in power - could lead to persisting inefficient institutions.

4.3 Political consolidation mechanism

The last mechanism that could determine the existence and persistence of inef-ficient institutions is widely treated in the recent literature (see e.g., Acemoglu and Robinson, 2000, 2006; Rajian and Zingales, 2000; Bueno de Mesquita et al. 2003), and focuses on the ability of groups in power to adopt choices that impoverish the other groups in order to ensure and consolidate their political power, or in other words the profits of the other groups could reduce the elite’s political power and make uncertain their future rents, consequently elite tries to block this change. This mechanism is most closely related to Acemoglu and Robinson works where the scholars use historical narrative method with a comparison of economic groups of economies with different performances in order to explain which sort of institu-tions matter.

In Acemoglu and Robinson (2000), empirical evidence related to the political consolidation mechanism from various historical contexts has been discussed. The scholars focus on the nature of political institutions and on the determinants of the distribution of political power as causes of technological backwardness. They look at per capita income discrepancies among different countries and highlight as the institutional failures are the main determinants of economic blocks. The institutio-nal failures are determined by powerful interest groups that could block changes in order to maintain their advantage position. In their analysis, scholars leave the “economic-loser hypothesis” (see, Krusell and Rios-Rull, 1996; Parente and Pre-scott, 1999) where the groups block the change in order to protect a position of economic advantage and define the “political-loser hypothesis” for which the chan-ges are blocked if they can erode political power of some groups; in fact, they argue that “it is groups whose political power (not economic rents) is eroded who will block

technological advances. If agents are economic losers but have no political power, they cannot prevent technological progress. If they have and maintain political power (i.e., they are not political losers), then they have no incentive to block progress political power and fear losing it who will have incentives to block” (page 126).

This hypothesis implies that the Coase’s compensatory mechanism - which can determine an optimal final result ex-post - in this environment cannot work, becau-se there is no credible commitment to compensate them once economic changes have been implemented. The used static model considers three sort of agents that maximize their utility in a strategic framework: citizen, monopolist and his rival who uses a better technology. The monopolist pays a tax on his sales and if he is in power could both apply a tax on citizen income and on rival profits, and his strate-gic choices are to block innovation with the probability of being substituted or not, or to introduce innovations with another probability to remain in power or not. So if the expected utility is greater than the potential cost of changing, the innovations could been adopted, or in other words the block occurs when it is relatively more likely to stay in power, when he blocks introduction of the new technology or when political rents from staying in power are greater and finally, when monopoly profits from blocking are greater or the tax revenue he can collect from his rival is smaller. Starting from “political replacement effect”, the two scholars successively (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2002) extend their work by considering the political competition envi-ronment that involve stochastic dynamic strategic interaction, and develop a model that represents a repeated game characterized by “Pure Strategy Markov Perfect Equi-librium”. In their model the groups in power would block the technological adoption if changes increase the probability to lose political power. In fact, innovation leads to an increase in income that can benefit the power elite by increasing future output and its revenues, but change can also lead to turbulence that will erode the advantages of the other groups that will benefit from these changes obtaining political power. In this paper the scholars try to explain why some countries as Great Britain or Germany du-ring the last part of 1800 century have tested faster industrialization process and other countries as Russia have seen a long period of economic backwardness. The interesting result is the non-monotonic relationship between political competition and growth; in fact, with higher political competition the elite adopt changes in order to increase its probability to win the political competition, meanwhile, with lower political competi-tion the incumbent adopts innovacompeti-tion to arise the benefit of his posicompeti-tion.

The same argument is treated by Robinson (2001) who highlights as “while

ca-pital accumulation may increase total income, it may induce institutional transition which is unfavourable to the autocrat. If a dictator loses political power, then he does not gain from development and will oppose it. Thus, a dictator may wish to slow accumulation”. The work focuses on the relation between endogenous government

policy and economic development and tries to explain why no efficient policies are adopted. The environment of this model is characterized by non-democratic regi-mes and the key assumption is that policy affects not only level of development, but also distribution of political power. The group in power controls political system and chooses the investment in public goods policy that maximize his welfare. The used model is a dynamic model: infinitely repeated game where “Predatory” elite’s behaviour determined an undersupply of public goods. This behaviour depends on relationship between development and the distribution of political power in a society. Furthermore, in this model the level of income and its distribution among the agents, influence the policy choices of the groups in power and consequently the probability that a predatory behaviour emerges. In this model the utilities of the agents depend on natural resources endowed - states with well endowment of natural resources tend to be more predatory - and on public goods furniture, such as infrastructure, that reduces the cost of subverting elite control increasing the probability to subvert the status quo. The main conclusion of the author is that bad policies are adopted if there are large benefits to holding power, also when coun-tries are well endowed with natural resources or not well endowed with factors that are complementary to public investment (i.e. human capital): in all of these cases, bad policies increase the incentive for a state to become “predatory” and fails to promote economic growth.

The channels through which the political consolidation mechanism works are explained by Rajan and Zingales (2000). The two scholars define a model where they show the mechanism through which the power groups (an initial allocation of major resources) destroy resources in order to preserve or increase their political power. The model is characterized by two agents with linear utility functions and

each agent is endowed with a certain amount of a fungible resources, also, while property rights on these endowments are fully specified and can be easily tran-sferred through a contract, the future use of this resource is not contractible. The agents can allocate their endowments in a productive activity that will increase the future level of investment or in “power-seeking” (it is identifiable as every unit of resources spent to increase bargaining position in order to increase the proba-bility of winning the game) but, power enhancing investment will be completely dissipative and its only function is to increase the unit’s shares of future surplus. The dynamic game is with complete information, and with subgame perfect equi-librium units. The scholars also model how at any time of the game agreement redistributes endowments, and thus leads to a different equilibrium allocation of surplus; finally, while property rights on these endowments are fully specified and can be easily transferred through a contract, the future use of these resources is not contractible. The chart explains how inequality in productivity or resources betwe-en the potbetwe-ential parties of an agreembetwe-ent leads to rbetwe-ent-seeking behaviour gbetwe-enerated by transfers: if the agents have unequal initial endowment of resources, agreement may be very difficult to reach, even if specific transaction is not difficult to conclu-de, and fungible resources can be transferred to compensate the losing party. This happens because the fungibility of the resource makes it hard to restrict its use, so this spill-over effect can impede the realization of efficient transactions.

Another work in the field of political consolidation mechanism is provided by Mesquita et al. (2003). The key question related to their analysis is “why are those

who produce peace and prosperity turned out of office after only a short time while those who produce corruption, war, and misery endure in office?” and the answer is

identified on the factors that govern the selection of leaders, that influence taxing and spending decisions, leadership turnover, social welfare, and institutional chan-ge. These factors are represented by the electorates that would obtain privileges from the winning of the leader they politically support, and also by the winning coalition that is the group which sustains incumbents in office and receive special privileges. The scholars focus on the mechanism through which political leaders