1 CONTENTS

1. Introduction 2

1.1. The treatment of bipolar depression: a controversial issue 2

1.2. Are ADs efficacious in bipolar depression? 5

1.3. Which is the real risk of iatrogenic mania/hypomania and of suicide following the use of ADs? 15

1.4. Escitalopram: a potential effective treatment for bipolar depression 22

2. Aim of the study 26

3. Methods 27 3.1. Patients 27 3.2. Study plan 27 3.3. Blood withdrawals 28 3.4. Laboratory analyses 29 3.5. Pharmacogenetic analyses 30 3.6. Data Analysis 31 4. Results 4.1. Patient Characteristics 32 4.2. Pharmacological treatment 32 4.3. Efficacy 32 4.4. Safety 33

4.5. Plasma levels and pharmacokinetic 33

5. Discussion 35

6. Tables and Figures 38

2 1 Introduction

1.1. The treatment of bipolar depression: a controversial issue

The lack of an effective treatment for bipolar depression represents a serious public health problem since it have been estimated that about 50 million persons with bipolar disorder in the world spend most of their ill time in depression rather than mania (Judd et al., 2002, 2003) and show great impairment in their work and social adjustment.

Despite the substantial burden associated with bipolar depression, options for treatment are limited and management of the depressive phase represents a major clinical challenge in the treatment of bipolar disorder.

Mood stabilizers (MSs), in fact, don’t show good antidepressant efficacy: rates of relapse prevention are still inconsistent and low for lithium, divalproex, lamotrigine as well as antipsychotics such as quetiapine, aripiprazole, olanzapine and the association of olanzapine with fluoxetine (Akiskal & Tohen, 2011). Besides, they are often not accepted by the patients who prefer the antidepressant medications (ADs) hoping in more rapid resolution of depression and fewer side effects.

ADs are commonly prescribed in bipolar depression: Baldessarini et al. (2007) used the U.S. national research databases to identify the most common patterns of psychotropic prescription in bipolar patients and reported that Ads were the first-choice agent twice as often as mood stabilizers. In fact, in their analysis, the most commonly prescribed first drug class was antidepressants (50% of patients), followed by mood stabilizers (25%: anticonvulsants, 17%, and lithium, 8%), sedatives (15%) and antipsychotics (11%).

3

A recent study conducted in Italy has found that overall rates of the use of ADs in bipolar depression in Italy are similar to those found in community surveys conducted within USA (Carta et al., 2012).

Remarkably, however, ADs lack specific regulatory approval for use in bipolar depression, and their clinical value and safety in bipolar depression remains uncertain and strikingly little studied (Ghaemi et al., 2003). Several trials of ADs in acute depressive phases of bipolar disorder indicate some short-term benefit vs. placebo (Gijsman et al., 2004), although two comparisons with MSs alone did not find superior short-term efficacy (Nemeroff et al., 2001; Sachs et al., 2007). Benefits of ADs treatment in bipolar depression also may be lower than in unipolar major depression (Ghaemi et al., 2004). Unfortunately, compared with the number of short-term studies, there are fewer long-term studies of ADs in bipolar disorder (Ghaemi et al., 2001).

Besides, several treatment guidelines (Sachs et al., 2000; APA, 2002; Grunze et al., 2002; Goodwin, 2003; Yatham et al., 2006), above all North American guidelines, and recent reviews (Goldberg et al., 2007; Grunze et al., 2010; Sidor & Macqueen, 2011) recommend caution in the use of ADs in bipolar depression which should be limited to the most severe cases. The major concerns regarding the use of antidepressants in bipolar depression are the risk of switch in (hypo) mania, the rapid cycling course and the development of suicidality (McElroy et al., 2006; Yerevanian et al., 2007; Bond et al., 2008).

As a consequence, there is the risk that psychiatrists prefer not to treat depressed bipolar patients who are left chronically and significantly depressed for very long periods of time. This may be an effect of the emphasis on the first-line use of MSs such as lithium and valproate for bipolar depression, despite the inadequate evidence of their efficacy and the lack of indication for their use in bipolar depression. Moreover, it could result from the warning on the prescription of ADs in bipolar depression launched by recent

above-4 mentioned guidelines and reviews.

Moller et al. (2006) in a recent critical review underline the gap between recent guideline recommendations and clinical practice, where physician has to face the unpleasant situation of using off-label drugs. These authors support an opinion contrasting with guidelines, in a syndrome-oriented approach they claim that “ADs are indicated in all kinds of depressive symptoms independent of whether the origin is functional, endogenous or organic, or whether they are unipolar or bipolar”. As a consequence, an AD which has been proven efficacious in unipolar depression might be also useful in other depressive disorders such as depression which presents in the course of bipolar disorder. Limitations of this interesting approach are represented by 1) controversial issues about efficacy of ADs in bipolar depression 2) safety related both to the acute depressive phase and to the maintenance phase of bipolar disorder.

So, both the acute and long-term treatment of bipolar depression raises the following issues: 1) are ADs efficacious in bipolar depression? 2) which is the real risk of iatrogenic mania/hypomania and of suicide following the use of ADs?

5 1.2. Are ADs efficacious in bipolar depression?

While in the past both unipolar and bipolar depressed patients were recruited for the phase III ADs trials, nowadays bipolar patients were excluded from them and the consequences are that there are few studies investigating efficacy of ADs in bipolar depression, and, unlike unipolar depression, there is little evidence concerning their efficacy in bipolar depressions.

There are two conflicting positions on this argument.

The first support the use of ADs in bipolar depression. The Cochrane meta-analysis of Gijsman et al. (2004) reviewed the evidence from twelve randomized, controlled trials on the efficacy and safety of ADs in the short-term treatment of bipolar depression. They concluded that the effect size of ADs was similar for unipolar and bipolar depression and that “ADs are effective in the short-term treatment of bipolar depression” stating that there is no strong reason to avoid ADs in bipolar depression. Other studies support this idea (Young et al., 2000; Moller et al., 2001; Bottlender et al., 2002; Tohen et al., 2003).

In the double-blind study of Young et al. (2000) 27 bipolar depressives were randomly assigned to two groups: one group patients received adjunctive paroxetine to one MS (lithium or valproate) and one group received a combination of the two MSs. Both treatments showed similar efficacy, but adjunctive paroxetine was associated with fewer drop-outs since all patients receiving paroxetine completed the 6-week study, whereas 6 patients of the group with two mood stabilisers dropped out prematurely. The reasons for dropouts included intolerance, non compliance, one unrelated medical complication, and in one case a mixed state occurred. This data, although limited by the small sample size, support the idea that adjunctive antidepressant may be more effective in clinical practice as

6

it is associated with fewer drop-outs and better treatment adherence.

Another add-on study, performed by Tohen et al. (2003) and with a greater sample size, demonstrated an additional significant benefit of adding fluoxetine to olanzapine compared to olanzapine monotherapy or placebo in the treatment of depression in bipolar disease type I.

One of strongest supporters of this position appears Moller et al. (2006) who disputes the fact that drugs other than ADs may be the treatment of choice in bipolar depression. Providing an indirect proof of the efficacy of ADs in bipolar depression, two studies performed by their research group at the University of Munich found that the efficacy of ADs in inpatients suffering from an acute bipolar depression was equal to that in unipolar depression (Moller et al., 2001; Bottlender et al., 2002).

The second position found low efficacy and underlines the risks related to ADs' utilization in bipolar depression; Ghaemi et al. (2003, 2004, 2008) bring evidence for a cautious approach to antidepressant use in bipolar disorder, recommending to use ADs mostly in the short-term and to discontinue them after recovery from the depressive episode, in consideration of unfavorable cost/benefit ratio. These data are in line with a recent review (Sidor & Macqueen, 2011) which concludes that, “although ADs were found to be safe for the acute treatment of bipolar depression, the lack of efficacy of ADs may limit clinical utility”.

However, both positions appear to be limited by the lack of existing studies about this issue. Another important question regarding the use of ADs in the treatment of bipolar depression is whether exists any difference in efficacy and safety between classes of ADs in order to better manage depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder.

Most authors agree to avoid tricyclics in consideration of a scarce profile of efficacy and tolerability in favor of other classes such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

7

In their first edition of “Manic-Depressive Illness” (1990), Goodwin & Jamison, after analyzing 77 studies involving 3336 patients, concluded that clinical literature provided almost no information about the relative efficacy of tricyclics ADs in treating bipolar depression versus unipolar depression. Small studies suggesting that bipolar depression was tricyclic resistant occasionally appeared (e.g. Kupfer and Spiker, 1981). However, medication efficacy in bipolar and unipolar depressed patients had not been compared. Rather, bipolarity or an history of mania was reported as one of several predictors of antidepressant non response in drug efficacy studies or course-of-illness investigations. In a large retrospective study (Moller et al., 2001) the treatment of 2032 patients consecutively admitted for a major depressive episode was assessed to determine where there was a difference in antidepressant efficacy between bipolar and unipolar patients. Almost all these patients were prescribed tricyclic ADs and at discharge, no statistically significant differences were found between bipolar and in unipolar depressives as regard to efficacy.

The two recent but conflicting meta-analyses of Ghaemi et al. (2008) and Gijsman et al. (2004) also bear on this question. From the meta-analyses of Gijsman et al. (2004) it emerged that tricyclics, although superior to placebo, were to some extent less effective than other ADs, suggesting that it may be prudent to use a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor or a monoamine oxidase inhibitor rather than a tricyclic antidepressant as first-line treatment. But this eminent work has been criticized for some limitations such as low number of studies analyzed, low numbers of patients in the studies, presence of unipolar depressives (only two studies included bipolar depressed patients exclusively).

More recently, Ghaemi et al. (2008) reviewed 12 long term studies, most of which used tricyclics as ADs, concluding that long-term adjunctive AD treatment was not superior to MS-alone in bipolar depression. In fact, authors found 27% lower risk of new depression

8

and 72% greater risk for new mania with adjunctive ADs vs. MS-only or no treatment. In comparison with an MS-alone treatment, adding an AD brought neither major protection from depression nor substantial increase in risk of mania.

In the past some authors (Himmelhoch et al., 1991; Thase et al., 1992) reported the superiority of tranylcypramine to imipramine, suggesting that the apparently superior efficacy of tranylcypromine in bipolar depression was specifically linked to its action on anergic features of bipolar depression.

More recently, in a recent retrospective analysis of data, Mallinger et al. (2009), comparing monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) with the serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine in patients with bipolar depression, reported that the antidepressant effectiveness of paroxetine was unacceptably low and rates of recovery with MAOIs were significantly higher (27% of paroxetine treated bipolar depressives had a durable recovery compared to a 53% durable recovery rate for MAO inhibitors).

Another recent study (Nolen et al., 2007) comparing the efficacy and tolerability of tranylcypromine vs. lamotrigine in bipolar refractory depression found that during the 10 weeks open randomized treatment with tranylcypromine or lamotrigine as add-on to a mood stabilizer 5/8 patients (62.5%) responded to tranylcypromine without switch into mania, compared with 4/11 patients (36.4%) on lamotrigine with two switches.

However, almost all authors suggest that MAO inhibitors may be superior to tricyclics in the treatment of bipolar depression and may be considered a second choice antidepressant when previous treatments had failed.

Few studies have explored the efficacy of serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).

Post et al. (2006) reported a response rate of 51% for venlafaxine compared to 49% for bupropion and 53% for sertraline and remission rate of 34% compared to 41% for

9 bupropion and 36% for sertraline.

Amsterdam et al. (2008) reported on a comparison between lithium and venlafaxine as an initial treatment for bipolar depression in a randomized, parallel group open label trial. Of 43 patients receiving venlafaxine and 40 receiving lithium, about a third had a story of rapid cycling. Venlafaxine resulted in a higher proportion of responders and remitters compared to lithium and this effect was independent of rapid cycling status (Amsterdam et al., 2008).

Regarding SSRIs, the role of this class of ADs in the treatment of unipolar depression is undiscussed but, compared with unipolar depression, general data on the efficacy of SSRIs in the acute treatment of bipolar depression are limited. At present, only fluoxetine in combination with olanzapine is approved by FDA for the treatment of bipolar depression. Nevertheless, studies about SSRI prescription in bipolar depression are several, probably in consideration of the fact that this class of ADs, since early studies, it appeared to be preferred over other classes (Gijsman et al., 2004).

These studies concern monotherapy, adjunct to mood stabilizers and comparisons with other classes of ADs.

Simpson and De Paulo (1991) in a small study of 16 bipolar II patients found that 10/13 of patients who continued on fluoxetine did well on follow-up. Amsterdam et al. in 1998 found similar rates of efficacy of fluoxetine in bipolar and unipolar depressives.

A 2005 randomized clinical trial consisting of 34 bipolar patients, 32 of which of the bipolar I subtype, examined the relative rates of treatment-emergent manic symptoms during fluoxetine monotherapy, olanzapine monotherapy, and combined fluoxetine plus olanzapine therapy. Over the course of the 8-week trial, for all treatment groups, a significant reduction in both HAM-D 28 and MADRS ratings was observed, with no evidence of an increase in treatment emergent manic symptoms, suggesting that fluoxetine

10

may be a safe initial treatment of bipolar depressives alone or in combination with olanzapine (Amsterdam et al., 2005).

In the 2010 EMBOLDEN II study, a total of 740 depressed bipolar patients (478 bipolar I, 262 bipolar II) were treated by monotherapy with either paroxetine (20mg/d), quetiapine (300 mg/d or 600 mg/d), or placebo. An eight week follow up revealed no statistically significant change in MADRS total score for paroxetine compared with placebo, both in bipolar I and bipolar II patients, in contrast with a marked response observed in the quetiapine arm. Manic/hypomanic switch rates, defined as Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) ≥16, did not statistically differ between paroxetine and placebo (10.7% and 8.9%, resp.), rendering paroxetine a safe, yet not an efficacious, option as monotherapy for bipolar depression (McElroy et al., 2010).

In a small, randomized, placebo-controlled proof of concept study (n = 10), treatment with escitalopram demonstrated a significant improvement in the depressive symptoms and functioning status of BPII patients over nine months, with no evidence of an affect switch, leading the author to suggest SSRIs as “mood stabilizers for Bipolar II Disorder” (Parker et al., 2006).

Other studies sought to clarify the role of SSRIs as adjuncts to mood stabilizers in the acute treatment of bipolar depression.

Kupfer et al. (2001) conducted an 8 week open study of citalopram added to lithium, valproate, carbamazepine or a combination of these agents in 33 patients with bipolar I or II depression. They found that 64% experienced a reduction in depressive symptoms.

One small double-blind randomized trial (n=20) compared the addition of lamotrigine versus citalopram to treatment with a mood stabilizer in bipolar depressed patients; though both treatments demonstrated a significant decrease in MADRS scores after six weeks of treatment with no evidence of major adverse events, the lack of a placebo arm and the small

11

sample size limited the applicability of the data (Shaffer et al., 2006). A similar size open-label trial of 12-week addition of escitalopram to treatment with mood stabilizer showed comparable results, including a mean decrease in HAM-D score of 12 points (P<.001). Although three cases of mania/hypomania were described, the small sample size and lack of control represent a problem with data interpretation (Fonseca et al., 2006).

One of the most quoted studies on the topic is the 2007 trial conducted by the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) collaborators, published in the New England Journal of Medicine by Sachs et al. (2007). In this double-blinded, randomized controlled trial of 366 Bipolar I and II patients, subjects receiving treatment with a mood stabilizer were randomized to co-treatment with an antidepressant, either bupropion or paroxetine. The duration of follow up was 26 weeks, and the primary outcome was defined as at least 8 consecutive weeks of euthymia. However, the study did not find a significant effect of either AD in any parameter, including remission or response. The reason for this disparity, as suggested by the authors, may lie in the more naturalistic design of the trial, allowing inclusion of patients with various comorbidities, such as anxiety disorders, substance abuse, or psychotic symptoms, as well as those receiving additional pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy.

In a recent report assessing the long term outcome of bipolar patients, Altshuler et al. (2009) prospectively followed eighty-three outpatients after receiving for 10 weeks ADs as add-on to mood stabilizers. 61/83 had good acute response, a rate higher than most reported, and 22/83 had a partial response. At one year follow-up, 42 (69%) of the 61 acute positive responders maintained positive response and 32 (53%) achieved remission. Compared to the acute positive responders, 6 (27%) of the 22 acute partial responders had achieved positive treatment response at study endpoint (p < .001). Eight acute positive responders (13%) and 5 acute partial responders (22%) developed mania. Patients who

12

achieve a positive acute antidepressant response to 10 weeks of antidepressant treatment adjunctive to a mood stabilizer will probably maintain response with the same continued treatment. Patients who achieve only a partial acute antidepressant response are less likely to further improve when the same treatment is sustained. The switch rate into mania for patients being treated with an antidepressant adjunctive to a mood stabilizer is not higher than the reported rate for patients on mood stabilizer monotherapy.

Prior maintenance studies by Altshusher et al. (2001; 2003) have found no greater rates switch rates into mania over the course of up to 1-year follow-up in patients who, after an acute positive treatment response, either continue or do not continue antidepressant treatment in combination with a mood stabilizer. Authors also reported that early discontinuation of ADs (within six months of remission) led to a higher rate of relapse into depression compared to those who continued.

Another recent comparison of antidepressant classes as adjuncts to mood stabilizers is the 2010 randomized clinical trial published by Pilhatsch et al. (Pilhatsch et al., 2010). Forty depressed bipolar I and II patients, on maintenance treatment with lithium, were randomized to receive either adjunctive paroxetine or amitriptyline. Following a six-week follow-up period, both treatments were shown to be equally as effective, with no significant difference in HAM-D reduction (−14.9 versus −15.5) or final HAM-D21 score (8.2 versus 9.9) between paroxetine and amitriptyline, respectively. Treatment with paroxetine did show a significantly more rapid onset, evident since the third week of treatment.

In a recent meta-analysis Sidor and MacQueen (Sidor and MacQueen, 2011) analyzed six trials comparing ADs to placebo in the acute (4–16 weeks) treatment of depressed bipolar I or II patients (Cohn et al., 1989; Nemeroff et al., 2001; Tohen M. et al., 2003; Tohen et al., 2004; Shelton & Stahl 2004; Amsterdam & Shults, 2005) 68% of patients were treated by concomitant mood stabilizers. A not statistically superiority to placebo or other current

13

standard treatment for bipolar depression has been shown, leading authors to conclude that ADs might be scarcely useful in bipolar depression.

A more intricate look into the potential use of ADs as adjuncts to treatment is a comparative trial employing lithium, lamotrigine, and paroxetine in two different treatment algorithms (van der Loos et al., 2010). One hundred and twenty four depressed bipolar patients receiving maintenance treatment with lithium were randomly assigned to additional treatment with either lamotrigine or placebo. After eight weeks, non responders were treated with supplementary paroxetine 20 mg/d. While addition of lamotrigine proved effective compared to placebo at week 8, adding paroxetine to non responders “blunted” this effect, causing the two groups to demonstrate no significant differences in MADRS score by week 16. Addition of paroxetine in non-responders to lithium plus lamotrigine did not appear to provide additional benefit, while it appeared to do so in non-responders to lithium plus placebo.

While this might indicate paroxetine as a potential efficacious agent, the lack of a second placebo arm, controlling for the effect of paroxetine, causes an inability to rule out at least some degree of spontaneous recovery, unrelated to paroxetine use.

In the largest and best designed study comparing the efficacy of paroxetine and imipramine in bipolar depression, Nemeroff at al. (2001) compared each antidepressant with placebo over 10 week under double blind condition in 117 patients who were also taking lithium. No significant differences in efficacy among the three groups were found. In a post hoc analysis the groups were stratified according to their lithium levels. It was found that imipramine and paroxetine were superior to placebo and equivalent to each other but only in patients with lower lithium levels less than 0.8 mEq/l. Thus lithium was as effective as the two ADs when given at doses that achieved levels of 0.8 mEq/l or greater.

14

to maintenance treatment with lithium during treatment-emergent depression. Of the 174 patients enrolled in the study, 49–53% demonstrated a response to treatment while 34–41% reached remission after 10 weeks, using the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS) and Clinical Global Impression for Bipolar Disorder (CGI-BP) scales. There was no significant difference in efficacy between drug classes.

In a 12 week randomized double bind pilot trial comparing lamotrigine to citalopram in twenty bipolar depressives Schaffer et al. (2006) reported that each treatment group experienced a significant mean reduction in total MADRS scores (citalopram Delta - 14.2, p=0.002; lamotrigine Delta - 13.3, p= 0.001), and there was no significant difference between treatment groups (p=0.78). Total response rates increased from 31.6% at week 6 to 52.6% at week 12. One out of ten patients in each group experienced a switch to hypomania. Taking into account limitations such as small sample size and lack of a placebo arm, results suggest that both lamotrigine and citalopram appear to be reasonable choices as add-on acute treatment for bipolar depression, with response rates continuing to rise considerably past 6 weeks of treatment.

In conclusion, from various studies some evidence emerges that SSRI might be a valid choice in treatment of bipolar depression, in consideration of various data above-mentioned which support their efficacy in bipolar depression.

15

1.2 Which is the real risk of iatrogenic mania/hypomania and of suicide following the use of ADs?

The aspects related to safety of ADs in bipolar depression concern risk of switch/ rapid cycling and suicidality induction.

Regarding the first aspect, occurrence of hypomania or mania during antidepressant treatment, has been recognized since the earliest use of imipramine in the late 1950s (Leyberg et al., 1959, Kiloh et al., 1960).

According to Akiskal and Pinto (1999) patients with antidepressant-associated hypomania are named bipolar III and are included into the evolving bipolar spectrum.

Nevertheless, the risk of switch as a result of antidepressant therapy, at present is not yet well-known. In patients with bipolar I disorder it has been estimated, depending on studies, between 30 and 60%. Patients with bipolar II appear to be less susceptible to present switches during treatment with ADs. It was thought that the risk of manic switches is a problem in the long term and therefore may be underestimated in studies with short follow-up. Despite of the existence of a certain risk of switch, some authors have suggested that the importance of this risk has been overestimated. In fact, the cyclic alternation of mania and depression is the main characteristic of bipolar disorder, so the distinction between spontaneous and induced manic episode is not always possible.

Moreover, it was hypothesized that antidepressant treatment may cause a mood destabilization, especially if ADs are administered at high doses and for a long period of time. Such destabilization is called rapid cycling, which entails the presence of at least four episodes/year and is associated with a poor response to treatment.

16

switches and rapid cycling induction and if a class of ADs is most involved in such events. Some answers to first question is given in part by a recent meta-analysis (Bond et al., 2008) including seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs), that reported rates of antidepressant-associated mood elevations in bipolar I disorder versus bipolar II disorder and four RCTs, that reported rates in bipolar II disorder versus major depressive disorder (MDD). Authors, taking into account the risk of antidepressant-associated mood elevations of almost all classes of antidepressant in bipolar and unipolar depressives, found mean switch rates of 14.2% for bipolar I and 7.1 for bipolar II in acute trials. In maintenance studies comparison rates were 23.4% and 13.9%. In comparison to unipolar depressives, bipolars had a fivefold increase in switch rates in short term studies (8.1% vs 1.5%) and a threefold higher risk in maintenance studies (16.5% vs 6%). The relative risk (RR) of antidepressant-associated mood elevations was greater in bipolar I disorder than bipolar II disorder (RR = 1.78, 95% CI = 1.24 to 2.58, p = .002), and higher in bipolar II disorder than MDD (RR = 2.77, 95% CI = 1.26 to 6.09, p = .01). Mood elevations occurred almost exclusively into hypomania in MDD and bipolar II disorder, while patients with bipolar I disorder experienced manias and hypomanias with similar frequencies. So, authors concluded that risk of antidepressant-associated mood elevations in bipolar II disorder is intermediate between that in bipolar I disorder and MDD.

In a different trial assessing the risk of switching in depressed bipolar patients treated with second-generation antidepressant (bupropion, sertraline and venlafaxine as adjunctive treatment to one or more mood stabilizer), bipolar subtype was also demonstrated to correlate with the risk of treatment-emergent mania/hypomania, with patients diagnosed with the bipolar II subtype showing significantly less susceptibility to switch (12% and 2%, resp.; YMRS > 14) (Altshuler et al., 2006).

17

class of antidepressant less associated to switch/rapid cycling induction.

In the Gijsman metanalysis (2004) the switch rate for TCAs was 10% vs 3.2% for all other antidepressant combined.

More recently, Koszweka and Rybakoski (2009) found that an antidepressant associated mania-hypomania in one-third of 333 bipolar inpatients. Highest risk was with for tricyclics, particularly amitriptyline followed by imipramine and clomipramine.

In line with the above-mentioned studies, Goodwin & Jamison (2007) stated that mania/hypomania as well as cycle acceleration might most likely be induced by tricyclics in the long term. According to a recent contribution (Yerevenian, 2011), selectivity within tricyclics may be allowed by some properties of individual tricyclics, such as propensity to cause anticholinergic effects or differential effects on other neurotransmitters and neurotrophic agents.

In the NIMH STEP BD study (Goldberg et al., 2007) occurrence of mania or hypomania was less frequent with MAOs and in comparison with other classes of ADs. Himmelhoch et al. (1991) reported a switch rate on MAOs of 21%.

Several authors agree that venlafaxine may have a intermediate potential of switching and of long term stabilization between SSRIs and TCAs. Goodnick (2007) in his review of randomized clinical trials of bipolar depression concluded that the greatest risk of destabilization over the long term was with venlafaxine. Vieta (2002) also found for venlafaxine a higher switch rate (13%) than for paroxetine (3%).

Nevertheless, in the study of Post et al. (2006) there was no significant difference in manic switch between drug classes. Manic switch, using a YMRS threshold score of 13, ensued in 4% of patients on bupropion, 7% of patients on sertraline, and 15% on venlafaxine, with a non significant trend towards venlafaxine being more harmful (P = 0.052). Adding a more liberal criterion of manic switch, such as a CGI-BP severity of mania ≥3, yielded a

18

significant difference between drug classes, with venlafaxine showing a higher risk of switch than both sertraline or bupropion (P = 0.03); however, the lack of a placebo arm seriously under-powers this study. Interestingly, the higher risk of manic switch in the venlafaxine group was accounted for by the rapid-cycling subset of patients, which constituted 27% of the sample, showing particular sensitivity to manic switch following venlafaxine treatment.

From the review of Goodwin & Jamison (2007) and other recent data (Gijsman et al.,2004) it has emerged that SSRIs are the class that less likely induce switching into mania and less destabilize over the long term.

In the 2007 trial conducted by the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD), as was the case in the previous meta-analysis by Gijsman et al. (2004), SSRIs did not show an increased risk of manic switch when coadministered with a mood stabilizer. However, further retrospective analysis of the risk of a manic switch, based on self-report, did reveal an increased risk of switch, correlating with a shorter duration of illness and a history of multiple antidepressant trials (Truman et al., 2007).

The hypothesis of Parker et al. (2006) is attractive: SSRIs might work as a long term mood stabilizer. In a small sample of 10 patients they found a diminution of depression, day spent depressed and days disabled on SSRIs compared with placebo. Although only speculative, there may be different subtypes of bipolar who respond differently to SSRIs: some patients might need a mood stabilizer while for other antidepressant alone might be sufficient. Data regarding suicidality during antidepressant treatment in bipolar disorder are even more confusing and contradictory. After decades of mostly debate and little research, the role of ADs, from tryciclics to SSRIs, in inducing suicidality in bipolar disorder is not clear.

In 2003 an analysis of FDA reports found a non significant increase in suicide rates between patients treated with SSRIs in comparison to placebo or other ADs (Khan et al.,

19 2003)

Although suicide is rare event, FDA have issued health advisories concerning the use of ADs and suicidality and all ADs currently carry black box warning of suicidality as a potential adverse outcome. These FDA warnings were initially for children and adolescents but were later extended to adults in 2004.

Psychiatric organizations have expressed mixed reviews about the black box warning and its effect on the treatment of patients with significant depressive disorders inviting researchers to determine both the effectiveness of ADs and the “precise estimate of the risk of suicidal behaviors or thinking during treatment.” But this problematic issue has not received adequate attention in research until now.

Several studies show that antidepressant treatment decreases the risk for suicidality among depressed patients (Baldwin et al., 1991). However, the risk of suicidal behaviour in depressed patients treated with ADs exists during the first 10-14 days of treatment, which requires careful monitoring, as suggested by recent the European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on suicide treatment and prevention (Wasserman et al., 2011).

Data suggest that if on the hand in unipolar depressives ADs may have a protective role against suicide (Yerevanian et al., 2004) on the other in bipolar depressives ADs may be associated with or contribute to suicidality (McElroy et al., 2006;Yerevanian et al., 2007). Increased suicidality in bipolar depressives may derive from two elements: 1) propensity to induce switches and mixed states with consequent high risk of suicidality related to mixed states (Leverich et al., 2006) 2) an association between antidepressant use, especially as monotherapy, and suicidal outcomes, mostly in the form of attempts or ideation (Yerevenian et al., 2007).

Fergusson et al. (2005), in a systematic review of 702 randomized controlled trials which included a total of 87 650 patients registered in trials for depression and anxiety and not for

20

bipolar disorder, documented an association between suicide attempts and the use of SSRIs and the absence of a significant difference between TCAs and SSRIs.

Studies on association between SSRIs and suicide in bipolar disorder are contradictory and inconclusive. If some authors confirmed it, others didn’t find no association.

In the retrospective review of Yerevenian et al. (2007) suicidal behavior event rates in 405 veterans with bipolar disorder followed for three years were found significantly higher during antidepressant monotherapy.

Among 1,000 patients with bipolar disorder in the National Institute of Mental Health’s Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) suicidal thoughts were significantly more present in bipolar patients who were taking an ADs and those who were not (25 percent vs 14 percent). (Goldberg et al., 2005). These results are in line with a prior study of Goldberg which highlighted that suicidal ideation was significantly higher in patient with dysforic mania with a previous antidepressant therapy in the week prior to admission (Goldberg et al., 1999). Akiskal et al. (2003) also found that suicidal thoughts are more likely present among patients admitted for antidepressant emergent hypomania.

One limitation of these studies might be represented by the fact that antidepressant are prescribed in more severe depressions often in presence of suicidal ideation.

On the other hand, some authors did not confirm this above-mentioned data.

Angst et al. (2005) found that long term treatment with lithium, neuroleptics and ADs reduced suicide rates in a cohort of 406 unipolar and bipolar depressive patients followed for 44 years. A recent case control analyses (Marangell et al., 2008), analysing suicide events (8 completed suicides, 262 attempts) occurred in Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) participants, showed that there was no relationship between suicide event and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)

21

prescription pointing out on complex relationships between treatment, severity, and suicidality.

A milestone in the treatment of bipolar patients is the famous comparison between olanzapine, olanzapine plus fluoxetine and placebo in bipolar I which showed there were no suicide events in all three groups (Tohen et al., 2003) but it is necessary consider some limitations of this study such as the difficulty to interpret the effect of fluoxetine alone and the exclusion of patients with a history of suicidal behaviour in the last three months.

An hypothesis might be that if on the one hand ADs might protect from suicide unipolar patients, on other hand they might induce it in bipolar patients as an iatrogenic effect. As a result, suicidality in depression might define a clinically relevant marker of bipolarity (Goodwin & Jamison, 2007; Cassano et al., 2012) suggesting that the use of ADs should be carefully monitored “in bipolar as well as potentially bipolar depressives” (Yerevanian et al., 2007).

22

1.4. Escitalopram: a potential effective treatment for bipolar depression

Escitalopram, an orally administered selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), is the pure S-enantiomer of the racemic bicyclic phthalane derivative citalopram. The mechanism of antidepressant action of escitalopram is presumed to be linked to a potentiating of serotonergic activity in the central nervous system resulting from its inhibition of neuronal reuptake of serotonin (5-HT) (Owens et al, 2001). In vitro and in vivo studies in animals suggest that escitalopram is a highly selective SSRI with minimal effects on norepinephrine and dopamine neuronal reuptake. Escitalopram is at least 100 fold more potent than the R-enantiomer with respect to inhibition of 5-HT reuptake, because of binding to two sites (both the primary site and the allosteric site) on the serotonin transporter (SERT) (Sanchez, 2006). Moreover, escitalopram has no or very low affinity for serotonergic (5-HT1-7), alpha- and beta-adrenergic, dopamine (D1-5), histamine (H1-3), muscarinic (M1-5), and benzodiazepine receptors (Sanchez et al, 2003).

Studies based on single and multiple doses of escitalopram revealed a linear pharmacokinetic behavior in a dose range of 10 to 30 mg/day.

Escitalopram is mainly metabolized in liver, with the production of two major metabolites, S-demethylcitalopram and S-didemethylcitalopram, because of the activity of CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 isoforms. Previous studies on citalopram, the racemic compound, showed that also the CYP2D6 isoform plays a role in demethylation of the drug (Brøsen and Naranjo, 2001). Escitalopram metabolites are less potent than parent drug, while they keep poor or absent affinity for receptors and transporters other than SERT.

Some mood stabilizers, among which the most frequent are lithium salts, valproic acid, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, levetiracetam, and gabapentin, undergo an

23

extensive liver metabolism, with a prominent role of cytochrome P450 enzymes (French and Gidal, 2000). In particular, CYP3A4 (carbamazepine), CYP2C9 (valproate), CYP2C19 (carbamazepine, valproate), UGT (lamotrigine, valproate), and microsomal epoxide hydrolase (carbamazepine epoxide). On the contrary, levetiracetam, is eliminated in part by enzymatic hydrolysis in which CYP or UGT enzymes are not involved, while gabapentin is eliminated exclusively via renal excretion as unchanged compounds. Finally, ketoreductases transforms oxcarbazepine to the active metabolite monohydroxycarbamazepine, which is subsequently glucuronated by UGT. On the other hand, some of these mood stabilizers are able to influence liver metabolism, because they are enzyme inducers (i.e., carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine) or inhibitors (i.e. valproic acid), whilst others do not significantly affect drug biotransformation in hepatocytes.

Two major factors account for the variability of drug metabolism among patients: 1) the concomitant presence of more drugs that compete for liver enzymes (inhibitors) or increase metabolic capabilities of hepatocytes (inducers) and 2) genetic polymorphisms. Both factors can influence pharmacokinetics of psychiatric drugs and, hence, treatment efficacy and tolerability.

Escitalopram, which is metabolized by CYP isoforms 3A4, 2C19 and 2D6, has negligible effects on cytochrome P450 drug-metabolizing enzymes in vitro, suggesting a low potential for drug-drug interactions (Burke, 2002). However, data from clinical trials are limited, and drug interactions should not be excluded when considering drugs that may affect cytochrome P450 isoform activity. Recently, Preskorn and colleagues described a significant increase (+80%) in metoprolol area under the time concentration curve of metoprolol (a CYP2D6 substrate) when the drug was administered at the end of a 17-day treatment period with escitalopram 20 mg/day in healthy volunteers of both sexes (Preskorn et al, 2007). These results support the need for further clinical studies that should confirm

24

or correct the in vitro results on possible pharmacokinetic interactions.

Among factors causing interpatient variability in drug availability, genetic polymorphisms affect drugs biotransformation and effect at sites of actions. In fact, all isoforms involved in escitalopram metabolism are polymorphic because several variants are known. In the majority of cases, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are capable to influence enzyme activity (or protein content within the liver), with a variable effect of drug metabolism. For CYP2D6, also gene duplication has been recognized as a possible polymorphism. SNP may characterize also genes that encode for receptors (i.e., the serotoninergic 5-HT2A receptor) and SERT (short, long and extralong variants). In particular, a recent study demonstrated that response to citalopram was associated to the polymorphisms in SERT and 5-HT1A genes (S variants and -1018C/G SNP, respectively) in patients affected by major depressive episodes (Arias et al, 2005). Therefore it may be hypothesized that the magnitude of escitalopram effect may differ in patients according to their genotype. However, there are not studies aimed at evaluating these important aspects, despite the presence of more than one factor of variability (i.e., concomitant drugs and polymorphisms of liver cytochromes, SERT and serotoninergic receptors) should increase the risk for clinically evident pharmacological interactions. Results obtained in vitro studies and clinical trials do not permit to exclude pharmacological interactions between escitalopram, the S-enantiomer of the racemic citalopram, and other psychiatric drugs used for the treatment of mood disorders. Furthermore, the presence of polymorphisms in genes coding for metabolic enzymes (i.e., liver CYP450 systems), targets (SERT) and structures involved in serotoninergic pathways (i.e., 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A) may play a role in determining the clinical effect of escitalopram, both in terms of efficacy and tolerability. Escitalopram has proved to be efficacious in treating unipolar depression but data providing support for its use in treating bipolar depression are minimal and are not considered to be

25

sufficient to guide clinical practice. Fonseca et al. (2006) conducted a small study to assess efficacy and tolerability of escitalopram in bipolar depression concluding that bipolar patients with moderate-severe depression showed improvement and few side effects during treatment with escitalopram in association with mood stabilizer.

26 2 Aim of the study

Primary objective

• To provide preliminary data on efficacy and safety of escitalopram as adjunctive treatment in bipolar depression

Secondary objectives

• To evaluate pharmacokinetic interactions between escitalopram and drugs used for the treatment of bipolar mood disorders.

• To assess any possible influence of patient’s genotype on drug kinetics, efficacy and tolerability.

Endpoints

• To analyze any clinical effects of escitalopram by using appropriate scales of evaluation before and after the introduction of the drug for each enrolled patient.

• To measure plasma concentrations of drugs administered for the treatment of bipolar disorders before and after administering escitalopram, and plasma levels of escitalopram and its active metabolite desmethylcitalopram

• To investigate the presence of gene polymorphisms known to influence cytochrome P450 isoforms drug metabolism.

27 3 Methods

3.1. Patients

This study was conducted at the Department of Psychiatry of the University of Pisa.

The site of the trial is a national referring center for mood and anxiety disorders, which includes a tertiary care psychiatric in-patient unit. Adult patients consecutively enrolled during the period 2009-2011 with a major depressive episode according to DSM-IV were assessed.

Eligibility criteria were: 1) current major depressive episode 2) lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder (both type I and II) according to DSM-IV criteria (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) 3) concomitant therapy with mood stabilizers 4) age within the range 18-70 years 5) adequate bone marrow, liver and renal function 6)ability to attend the follow up visits 7) ability to provide a written informed consent 8) proved compliance.

Patients who 1) were treated with concomitant antipsychotic therapy, 2) needed to be treated with antidepressant other than study drug, 3) had a score ≥2 at item 3 on HAMD, 4) had a history substance abuse or dependence within the last year, 5) were pregnant or breast feeding women 6) had a diagnosis of renal or liver failure, jaundice, cardiopathy or severe lung diseases, hematological diseases 7) had past episodes of photosensibilization, were excluded. Premenopausal female patients were required to use contraceptives.

The study was approved by Local Ethical Committee and patients signed a written informed consent.

3.2. Study plan

Eligible patients were enrolled in a one-year open trial of escitalopram as adjunctive therapy to their concomitant treatment with mood stabilizers (lithium, gabapentin, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, valproic acid, pregabalin, nimodipine). Patients received a daily dose of escitalopram between 5 and 20 mg/die. Other antidepressants were discontinued at least 1 week before beginning trial.

A physical examination, laboratory tests (including blood levels of mood stabilizers and escitalopram) and an electrocardiogram were assessed at baseline. Blood levels of mood

28

stabilizers and escitalopram were collected at baseline and repeated 10 days after escitalopram start and at week 8 of treatment with escitalopram during third follow up visit.

Medical and psychiatric histories were obtained by a trained psychiatrist.

Efficacy and tolerability of treatment were evaluated using the following evaluation scales: 1) SCID-I (Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis I Disorders): is a semistuctured interview for making the major DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses.

2) CGI (Clinical Global Impression): is a classic instrument for making global assessments that yields three different measures: 1. Severity of illness (assessment of patient’s current symptom severity;CGI-S), 2. Global improvement (comparison of patient’s baseline condition with his/her current condition;CGI-I), 3. Efficacy index (comparison of patient’s baseline condition with a ratio of current therapeutic benefit to severity of side effects;CGI-E).

3) HAM-D (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale) is a 21-item rating scale used to rate the severity of a patient's depression. Each question has between 3-5 possible responses which increase in severity. The first 17 questions contribute to the total score and questions 18-21 are recorded to give further information about the depression such as if paranoid symptoms are present

4) PRISE (Patient Rated Inventory of Side Effects) is a patient self report used to qualify side effects by identifying and evaluating the tolerability of each symptoms.

SCID-I, CGI, HAM-D and PRISE were assessed at baseline(T0). CGI, HAM-D and PRISE were repeated during the planned follow-up visits at 2nd(T1), 4th(T2) 8th (T3) and 16 th week (T4) (±3 days) and at the end of follow up period (T5) (1 year after enrollment).

Response to treatment was defined as 50% reduction in baseline HAMD score and a score of 1 (“very much improved”) or 2 (“much improved”) on the CGI-I scale. Remission was defined as a score of HAMD of 7 or below.

3.3. Blood withdrawals

Blood samples (4 ml each withdrawn before morning administration of drugs) were collected in heparin-containing tubes, marked with the appropriate personal code (i.e., ESC003) following the scheme:

• First blood sample, collected during the first visit, or, in the case of patients candidate to receive escitalopram and changes of dose regimen of drugs already administered, 5 days after dose changes but before the start of escitalopram administration.

29

• Second blood sample, 10 days after escitalopram start.

• Third blood sample, at the 8th week of treatment with escitalopram during third follow up visit.

The first blood sample was used to evaluate plasma levels of drugs coadministered with escitalopram, and to extract genomic DNA that was analyzed in order to evaluate the presence of polymorphisms associated to treatment tolerability and efficacy (see section “Pharmacogenetic analyses”). The measurement of plasma levels of drugs was repeated using the second and the third blood sample, while the evaluation of patient’s compliance was based on plasma levels at the 8th week of escitalopram treatment (3rd blood sample).

3.4. Laboratory analyses

A 1 ml aliquot of the first sample was stored at -80 °C for further genetic analyses. Blood samples was centrifuged immediately after their collection and the plasma was stored at -20 °C until the analyses were done, then they were destroyed.

Plasma levels of the drugs were evaluated according the following methods.

Plasma levels of escitalopram and its active metabolite desmethylcitalopram were assessed by using a high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method with UV detection with minor modifications [Greiner et al, 2006]. Briefly, standard and patients’ plasma samples (200 um each) were added with 100 µl of acetonitrile, vortex for 1 min and centrifuged at 12.000 rpm for 10 min. Fifty µl of clear supernatants were injected directly in HPLC system. Mobile phase was obtained mixing 8 mM phosphate buffer pH 6.4 and acetonitrile (1:1, v/v), and its flow was 1.5 ml/min. Analytes were separated using a LiChrospher CN 20 m, 10×2.1 mm precolumn and a CN-endcapped LiChrospher 250×4.6 mm, 5 m analytical column, and wavelength of UV detector was set at 210 nm. The instrumentation was a Waters Breeze apparatus.

Plasma levels of lamotrigine, gabapentin, and levetiracetam were evaluated by using commercially available kits (Chromsystems, Munich, Germany) on a Waters Breeze apparatus. Finally, serum levels of valproic acid and lithium were assessed by immunoassay using appropriate kits (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA).

Plasma levels of drugs other than escitalopram were assessed and the percentage variation was calculated as follow:

30 Variation (%) = 100 x

(Cplasma+Esc– Cplasma-Esc) Cplasma-Esc

where Cplasma-Esc and Cplasma+Esc are the plasma concentrations of drugs before and after

Escitalopram.

3.5. Pharmacogenetic analyses

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood by using the Qiagen DNA Mini Kit and the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Milan Italy). The nucleic acid was stored at -80 °C within the laboratories of the Division of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy under the responsibility of Dr. A. Di Paolo.

Assays for CYP SNPs

Nucleotide sequences of genes of interest (CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP3A4) were obtained from web resources (Genebank) and fragments containing the polymorphisms were analysed by the software Filebuilder (Applied Biosystems). Results were sent to the manufacturer to synthesize primers and fluorescent probes for allelic discrimination using Taqman assays. For CYP2C19, the presence of CYP2C19*2 and CYP2C19*3 polymorphic variants were evaluated, while for CYP3A4 the variant CYP3A4*1b was investigated. Finally, the *3, *4, *5 and *6 alleles were evaluated in the case of the CYP2D6 isoform.

PCR-RFLP assay for 5-HT SNPs

The presence of -1018C/G SNP of the 5-HT1A gene was evaluated by amplifying the region

of interest (182 bp) within the promoter by using the following primers: forward, TGGAAGAAGACCGAGTGTGTCTAC-3’, reverse 5’-TTCTCCCTGGGAGAGTAAGGCTGG-3 [Arias et al, 2002]. PCR characteristics were as follows: 35 cycles (45 s at 95 °C, 45s at 56 °C and 45 s at 72°C) plus a final step of 10 min at 72 °C. PCR products were digested using Hpy CH4IV restriction enzyme and separated on 4% agarose gels. C and G alleles were identified for the presence of one or two bands, respectively.

31

gene including the 102T/C SNP: forward, TCTGCTACAAGTTCTGGCTT-3’, reverse 5’-CTGCAGCTTTTTCTCTAGGG-3’. The PCR characteristics were as follows: 3 cycles of denaturation (94 °C for 3 min, 62 °C for 30 sec and 72 °C for 1,5 min), 35 cycles of amplification (94 °C for 1 min, 62 °C for 30 sec, and 72 °C for 1,5 min), 1 final extension step (5 min at 72 °C). Two nanograms of PCR product were digested overnight at 37 °C with 4 units of MspI restriction endonuclease. The final suspension was resolved in a 3% agarose gel by electrophoresis. T and C alleles were identified for the presence of one or two bands, respectively.

PCR assay for SERT polymorphism

Amplification of promoter region of SERT gene was be performed by using the following pair of primers flanking the 5-HTTLPR: forward, 5’-GGCGTTGCCGCTCTGAATGC-3’, reverse 5’-GAGGGACTGAGCTGGACAACCAC-3’ [Young et al, 2006]. PCR products (484 and/or 528-bp fragments, S short and L long variants respectively) were visualized by running on a 1.8% agarose gel with ethidium bromide.

3.6. Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 15.0 (SPSS, Inc,Chicago,2007). Descriptive data analyses were carried out in all sample (n=15) and were expressed in means plus standard deviations and medians plus interquartile ranges. To analyze the change in mean HAM-D and CGI-S scores Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was conducted in subjects (n=10) who completed the follow up period of 16 weeks.

32 4.Results

4.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 15 patients were enrolled in the study.

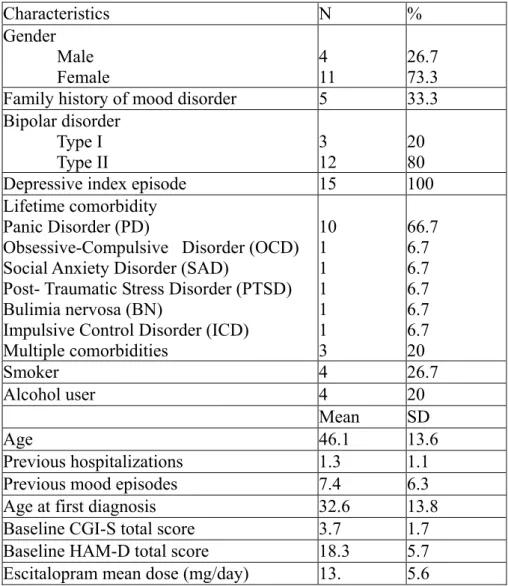

The tables 1 and 3 show clinical characteristics of the subjects. 73.3% (11) were female. Mean age was 46.1 years (SD=13.6). Twelve (80%) of them had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder type 2. Five (33.3%) had a positive family history for mood disorders. In all cases the index episode was represented by a depressive episode. Comorbidity with other Axis I mental disorders was observed in 80% (N =12) of the sample and in most cases (66.7%, N = 10) was represented by comorbidity with panic disorder. In 20% (N = 3) of the cases there were two comorbid psychiatric diagnoses. Patients show a mean of previous hospitalizations of 1.3 (SD=1.1) and a mean of previous mood episodes of 7.4 (SD=6.3). Mean age at first diagnosis was 32.6 yrs (SD=13.8).

Baseline HAM-D mean score was 18.3 (SD=5.8) and baseline CGI- Severity mean score was 3.7 (SD= 1.7).

4.2. Pharmacological treatment

The mean dose of escitalopram for all subjects was 13 (SD=5.6).

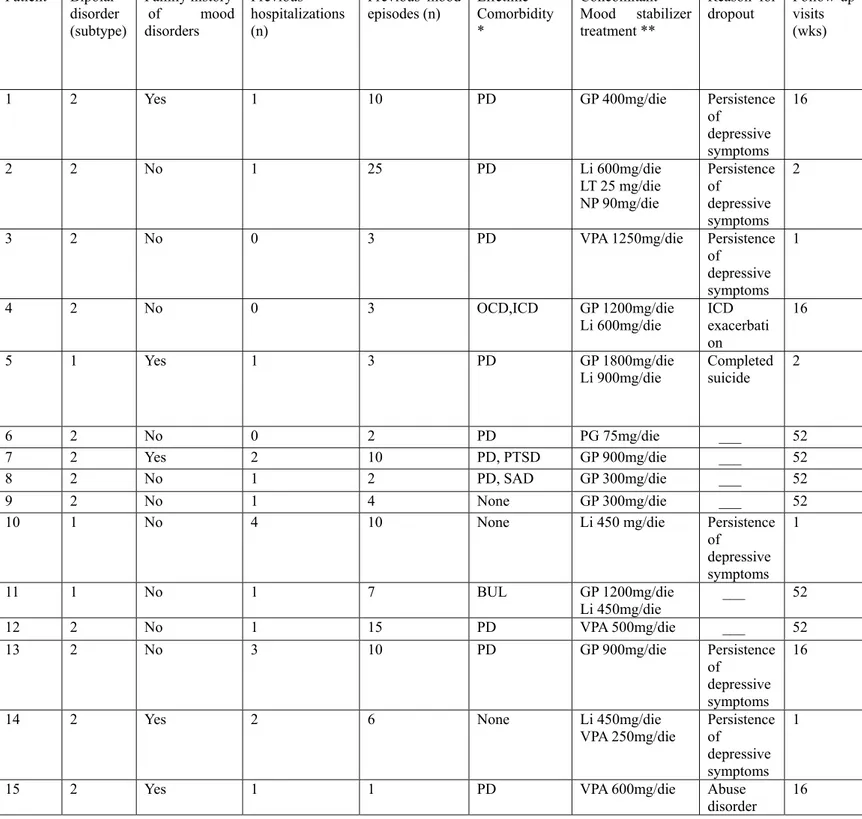

Of the 15 patients enrolled in the study, 10 were taking monotherapy (3 with valproic acid, 1 with Lithium, 5 with Gabapentin, 1 with Pregabalin). Five patients were prescribed lithium and other mood stabilizers (in three cases associated with gabapentin, in one case with lamotrigine and nimodipine, and in one case in association with valproic acid).

The tables 2 e 3 show a detailed description of mood stabilizer therapy. 4.3. Efficacy

Fifteen patients entered the trial. Nine patients dropped out before the end of protocol (1 year): six because of the persistence of depressive symptoms which needed a switch to another antidepressant, one because of the exacerbation of a pre-existent impulsive control disorder – pathological gambling which caused the discontinuation the antidepressant, and one because of the onset of substance abuse and one because of completed suicide.

33

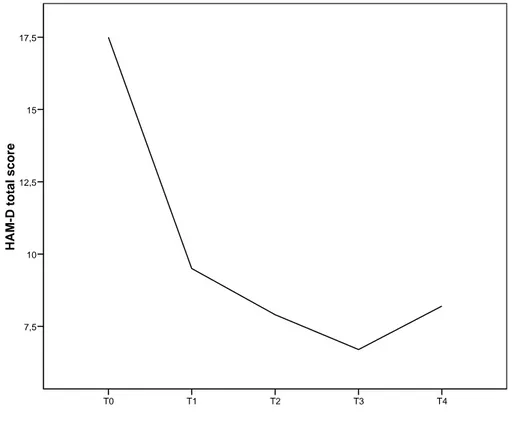

to avoid recurrences after a depressive episode (Montgomery et al., 2006). In those patients, the overall mean scores on HAM-D decreased from 15.7 (SD=5.8) at baseline to 8.2 (SD= 6.3) (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, z=- 2.193; P= 0.028); the CGI-S score decreased from 3.4 (SD=0.84) to 2.5 (SD=1.0) (z=-1.558; P=0.119). Mean HAM-D scores and mean CGI-S scores improved from baseline at all assessments in all patients (Fig 1-2).

At week 16, 6 (60%) of 10 patients could be considered as “responders”, with a reduction of the HAMD of 50% or more compared to baseline and 5 (50%) as “in remission”,as reported a HAM-D total score less than seven.

Of the 6 patients who completed the one-year trial, 4 (66.7%) could be defined as "responders" , and five of them (83.3%) could be considered “in remission” at week 16 (T4). Those six patients showed a mean HAM-D score of 17.3 (SD=7.14, range= 6-27) at baseline and 3.7 (SD = 4.8, range = 0 – 13) at 1 year after recruitment. Mean scores of the item CGI-S (severity) was 3.17 (SD = 1.6, range = 0 – 4) at baseline, and 1.83 (SD=0.75, range = 1-3) at T5.

At T4 the score of CGI-I (overall Improvement) was 1 ( much improved) in 5 of the 6 patients who completed the study and 2 (improved) in one patient, whilst at the follow-up visit (T5), four patients scored 1 (much improved) (66.7%), and the remaining two subjects (33.35%) reported a score of 2 (improved).

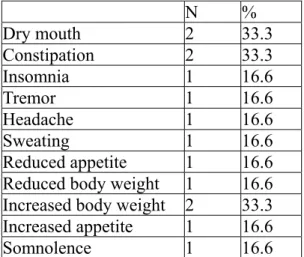

4.4. Safety

At baseline, 40% of patients (n= 6) complained at least one adverse effects as recorded by the PRISE, the most frequent being dry mouth, constipation and increased body weight (Table 3). During the follow-up period the most frequently observed side effects were dry mouth, nausea, sweating, increased body weight and somnolence. Table 4 shows frequency of side effects at planned evaluations.

4.5. Plasma levels and pharmacokinetic

Median values (interquartile range) of escitalopram concentrations in the 15 patients, who received escitalopram at doses ranging from 5 up to 20 mg/day, were found to be 23.0 ng/ml (4.9-36.2 ng/ml) and 30.7 ng/ml (28.4-73.2 ng/ml) 10 days and 8 weeks after the beginning of drug administration, respectively.The difference in plasma concentrations was found to be significant at the Wilcoxon matched pair test (p=0.047), probably because the steady state

34

was not achieved by all of the patients 10 days after the beginning of escitalopram administration. It is worth noting that all of the patients had plasma concentrations of escitalopram which were within the therapeutic range described in the technical note of the drug (20-125 nmol/l equivalent to 6.5-40.5 ng/ml). However, two patients had plasma levels of escitalopram greater than those observed in other patients, but the following analysis of CYP isoform genotypes excluded they are poor metabolizers (see below).

All of the 15 patients were administered escitalopram in association with other CNS agents, such as gabapentin (9), lithium (6),valproic acid (4), lamotrigine (1) and pregabalin (1). Some differences in plasma concentrations between the two periods were observed but they were not statistically significant, probably because the low number of patients and the wide interpatient variability.

Genetic analyses excluded the presence of rapid or poor metabolizers among the enrolled patients for both CYP isoforms, 2C9 and 2C19, thus these data were excluded from the following analyses.

35 5. Discussion

Despite the considerable burden associated with bipolar disorder, the treatment of bipolar depression is still unclear and options for the treatment appear to be limited.

There is some controversy regarding the efficacy and safety of ADs in bipolar depression, but at time studies are inconclusive and unable to provide valid and feasible guidelines to the clinician who treats bipolar depression. As consequence, bipolar depressed patients are often untreated or inappropriately treated, with increased ill time spent in depression.

Moreover, many patients with bipolar disorder suffer from complex clinical syndromes which need combination treatments with mood stabilizers, ADs, antimanic and antipsychotic drugs, or benzodiazepines. The rationale for using more than one drug is related to the multifaceted syndromes which may include depression and/or mania, psychotic symptoms, anxiety, eating disorders or substance use disorders.

So, in clinical settings, the utilization of ADs for treatment of depression or anxiety during bipolar disorder is an ordinary practice. In line with previous studies which have shown that the SSRIs may be an option in bipolar depression (Gijsman et al., 2004; McElroy et al., 2010), our pilot study suggests that adjunctive escitalopram might be an useful and safe strategy in bipolar depression.

In fact, adjunctive escitalopram to ongoing mood stabilizer therapy leaded to early improvement which continued throughout the follow-up period. Mean scores of HAM-D decreased in a significant manner from baseline to endpoint, and CGI-S decreased even though this result was not statistically significant. Furthermore, 60% patients can be considered "responders" and 50% “in remission” after week 16 of treatment.

Our study had several drop outs, but 6 of the 10 patients completed the one-year follow-up and maintained the remission over this period, as proved by the CGI-I scores of 1 or 2 (improved or much improved) at T5. Moreover, at 1 year-endpoint 83.3% of patients could be considered in remission, with HAM-D total score less than seven. Although the high rate of dropouts limited the validity of our results, the duration of our one-year follow-up permitted us to evaluate long-term efficacy, in those patients.

Efficacy of escitalopram in the treatment of major depressive disorder is undisputed (Kennedy et al., 2009; Cipriani et al., 2009; Ali et al., 2011) but data providing support for its use in treating bipolar depression are minimal and are not considered to be sufficient to guide clinical practice.

36

To our knowledge there is only another small open trial (Fonseca et al., 2006) that suggests that escitalopram in association with mood stabilizers may be an effective and well-tolerated treatment in bipolar depressives but in this study follow-up period was of 12 weeks and not of 16 weeks, which is the period of time usually considered when assessing the efficacy of antidepressants in clinical trials.

In our study escitalopram was overall well tolerated in combination with mood stabilizer. In fact, no patient discontinued drug after experiencing an adverse event related to escitalopram.

At baseline, 40% of patients complained adverse effects -dry mouth, increased body weight and constipation-probably related to treatment with ongoing mood stabilizer. After the prescription of escitalopram, patients frequently complained dry mouth and increased body weight (mostly in the first two weeks) and reported some serotonin related adverse events, such as nausea and sweating which however appeared mild and transient, not leading to drug withdrawal or additional medication. These side effects usually decreased in intensity and frequency with continued treatment, in line with other studies (Wade et al., 2002).

A more careful consideration is required from the patient who presented suicide before the fourth week. Suicidal risk with antidepressant has been reported to be highest within the first week of treatment (Jick et al., 2004), requiring careful monitoring, as suggested by recent European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on suicide treatment and prevention (Wasserman et al., 2011). Of note, our patient presented some characteristic of severity such as type I bipolar disorder, positive family history for mood disorders, early onset of the disease, panic disorder comorbidity and several previous hospitalizations. Illness severity may have directed our choice of adjunctive antidepressant resulting in a confounding factor since among bipolar depressives antidepressant therapy is often reserved for the very severe cases and so a greater suicidality might derive from illness severity.

Occurrence of pathological gambling and substance abuse were other reasons that caused early drug discontinuation, but it is difficult to ascribe to escitalopram the onset of these phenomena. In fact, if on the one hand different studies pointed out that escitalopram may be effective in pathological gambling (Black et al., 2007; Grant et al., 2006), on the other hand, to our knowledge, no relationship was found between the onset of substance abuse and the prescription of an antidepressant.

Our study was characterized by an accurate therapeutic drug monitoring, which we consider crucial to assess safety of adjunctive escitalopram to ongoing mood stabilizer therapy. A close monitoring could help to optimize drug treatment using minimum effective doses and

37

recording side effects at therapeutic doses and potential drug interactions (Baumann et al., 2004; Lundmark et al., 2000).

The concomitant use of several different drugs may expose the patient to pharmacological (pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic) interactions (Spina and de Leon, 2007). Our study was designed to address the question if escitalopram could potentially interact with MSs prescribed in our patients. In facts, after 10 days and 8 weeks of treatment, all of the patients had plasma concentrations of escitalopram within the therapeutic range, but no patients showed abnormal plasma levels of escitalopram which could suggest a possible interaction with concomitant pharmacological agents. As a matter of facts, the lack of evident interactions between escitalopram and other drugs in a naturalistic setting suggests the safety pharmacokinetic profile of the antidepressant despite the large interpatient variability. However, because of the software used in the present study allow the evaluation of variability in drug pharmacokinetics, studies in larger population of patients will be warranted.

Our study has some limitations which must be considered: above of all, the small sample size and the heterogeneity of concomitant mood stabilizer therapy limit the generalizability of our results, albeit the heterogeneity of concomitant therapy might provide a more wide-ranging and naturalistic sample of bipolar patients. Moreover, the absence of a double-blind design with a placebo control also prevent us from assessing the degree of specificity of the reported improvements. Of note, our sample consisted of patients with some features of severity such as depressive index episode, early onset disease, high rates of Axis I comorbidity, high number of previous hospitalizations and mood episodes. With these features our sample appeared more difficult to treat but more realistic and closer to the daily practice. Our choice to use an antidepressant in these severe patients was motivated by the persistence of long-term disabling depressive symptoms. On other hand, the relatively long follow-up and therapeutic drug monitoring strength our results and allow us to test the safety and the risk of switch in examined patients.

38 6. Tables and Figures

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the sample (N=15)

Characteristics N % Gender Male Female 4 11 26.7 73.3 Family history of mood disorder 5 33.3 Bipolar disorder

Type I

Type II 3 12 20 80

Depressive index episode 15 100

Lifetime comorbidity Panic Disorder (PD)

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD)

Post- Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Bulimia nervosa (BN)

Impulsive Control Disorder (ICD) Multiple comorbidities 10 1 1 1 1 1 3 66.7 6.7 6.7 6.7 6.7 6.7 20 Smoker 4 26.7 Alcohol user 4 20 Mean SD Age 46.1 13.6 Previous hospitalizations 1.3 1.1

Previous mood episodes 7.4 6.3

Age at first diagnosis 32.6 13.8

Baseline CGI-S total score 3.7 1.7 Baseline HAM-D total score 18.3 5.7 Escitalopram mean dose (mg/day) 13. 5.6

39 Table 2. Mood Stabilizers

N % Monotherapy Valproic acid Lithium Gabapentin Pregabalin 3 1 5 1 20 6.7 33.3 6.7 Combination therapy Lithium+ Gabapentin

Lithium+ Lamotrigine+ Nimodipine Lithium+ Valproic Acid

3 1 1 20 6.7 6.7

Dose ranges: lithium, 450-900 mg/day; valproic acid,250-1250 mg/day; gabapentin, 300-1800 mg/day; pregabalin 75 mg/day; nimodipine 90 mg/day

40

Table 3. Diagnosis, concomitant treatment and reasons for dropout

*PD=Panic Disorder, OCD= Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, PTSD=Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, SAD=Social Anxiety Disorder, BUL=Bulimia

**GP=Gabapentin, Li= Lithium salts, VPA= Valproate, LT= Lamotrigine, NP=Nimodipine, PG=Pregabalin Patient Bipolar disorder (subtype) Family history of mood disorders Previous hospitalizations (n) Previous mood

episodes (n) Lifetime Comorbidity

*

Concomitant

Mood stabilizer treatment **

Reason for

dropout Follow-up visits

(wks)

1 2 Yes 1 10 PD GP 400mg/die Persistence

of depressive symptoms 16 2 2 No 1 25 PD Li 600mg/die LT 25 mg/die NP 90mg/die Persistence of depressive symptoms 2

3 2 No 0 3 PD VPA 1250mg/die Persistence

of

depressive symptoms

1

4 2 No 0 3 OCD,ICD GP 1200mg/die

Li 600mg/die ICD exacerbati

on 16 5 1 Yes 1 3 PD GP 1800mg/die Li 900mg/die Completed suicide 2 6 2 No 0 2 PD PG 75mg/die ___ 52 7 2 Yes 2 10 PD, PTSD GP 900mg/die ___ 52 8 2 No 1 2 PD, SAD GP 300mg/die ___ 52 9 2 No 1 4 None GP 300mg/die ___ 52

10 1 No 4 10 None Li 450 mg/die Persistence

of depressive symptoms 1 11 1 No 1 7 BUL GP 1200mg/die Li 450mg/die ___ 52 12 2 No 1 15 PD VPA 500mg/die ___ 52 13 2 No 3 10 PD GP 900mg/die Persistence of depressive symptoms 16

14 2 Yes 2 6 None Li 450mg/die

VPA 250mg/die Persistence of depressive symptoms 1

15 2 Yes 1 1 PD VPA 600mg/die Abuse