Marco Pustianaz

Now You See It, Now You Don’t: Performing Literature in

Transition

*A Resting Ground

* The Ur-text of this essay

dates back to a 2010 poster session I presented at the ESSE (European Society for the Study of English) convention held in Turin (August 24th-28th). I would

like to thank all those who left comments on my

guest-book, among them Serena Guarracino, Giovanna Covi, Cristina Iuli, Marina Vitale. No thanks can equal Rory Macbeth’s generosity and warmth. Thank you.

1 The manually painted

building was unveiled at the East International Art Exhibition. Another version, called No Place (Kingly Digs), was commissioned by Alasdair Robinson for the Manor Hotel in Sunderland, formerly a forty-room hostel for the homeless. I am going to engage only with the Norwich work, No Place (Spiral).

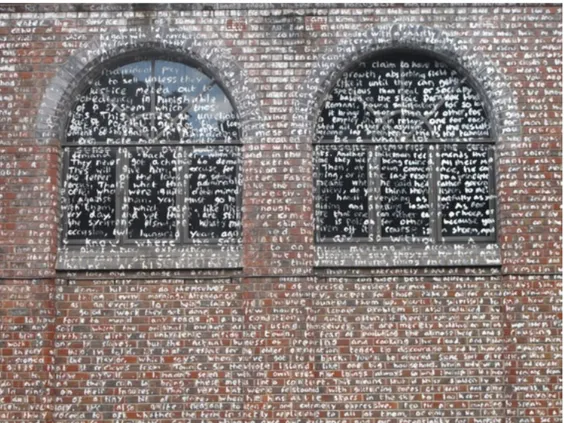

Fig. 1: Rory Macbeth, No Place (Spiral), 2006. Matt white emulsion on walls. Eastern Electricity, Norwich, courtesy of the author.

In 2006 the English artist Rory Macbeth painted the Eastern Electricity building in Norwich by transcribing the whole 42,000 words of Thomas More’s Utopia (in its 1965 Penguin Classics translation) over its uneven outer surfaces. The building was doomed, due for demolition by the end of the year.1 This uncanny object, an

ambiguous monumentalization of a literary text, will serve as a provisional resting ground for a meditation on the lines of flight unsettling the ‘literary’ no less than the ‘textual’. On the one hand, we are facing a ‘literal’ transcription of the order of the text, on the other, an arresting materialization that is a stumbling block to the ordinary set of practices which enable the ‘literary’ performance of that same text. It seems that Macbeth’s labour of love has in fact created a literary monstrum, a book in bricks and mortar, indeed a Sphinx: even though the text of Utopia is ostensibly unfolded before our very eyes, it becomes enigmatic in light of its amplified openness. Between the writing of the text and the reading of it a certain encoding/decoding has been, if not entirely interrupted – we are still able to read small portions of text closer to us, and even more with the aid of the photographic prosthesis – at least made awkward, defamiliarized. The question that this Sphinx,

mute in its monstrous speech, suggests is, “Under what conditions does literature cease to be (visible)?” It is a question of thresholds and passings, as though literature had little to do with intrinsic properties, nor were just a social and institutional convention but, above all, a contingent aesthetic (i.e. sensible) event.

In the Norwich Utopia linearity is preserved, yet by spiralling all along the four sides of the building from top to bottom it exceeds the length manageable by the human eye: the display of an excessive amount of text and its nearly unbroken uniformity not only strains reading but disperses our attention. Therefore, regardless of Macbeth’s literal transcription, More’s text can no longer sustain its literary textuality inasmuch as certain grounds of legibility have been shaken by, among others, a re-modulation of scale that is enough to turn this otherwise literary text into another ‘thing’, indeed another performance. Although as a copy it may still be considered one of Utopia’s possible text-tokens, it also uncannily defaces the original. What Macbeth’s materializing performance makes visible is that another materialization, all but invisible, is involved in the habitual embodiment of Utopia’s readable text as a printed book. The material dissociation that has produced the ‘un-bound’ text of No Place (Spiral) signals a temporary removal from what Rancière has called “the historical mode of visibility of the works of the art of writing” called literature.2 In other words, it signals a breach of the enabling and constitutive

conditions for literature to appear. Macbeth’s deceptively simple chirographical performance makes the literary disappear by means of a certain distortion, as if by spilling the text out of the folds of the book and by making it obscene through an unashamedly public display of its interiors, Macbeth had also suspended Utopia’s literary performance. Its suspension shows that the performance of repetition has gone awry, that literary properties emerge or ‘demerge’ by flickering in a spectrum of becomings ⇔ unbecomings visible.3

The Norwich site raises a knot of issues around the contingent production of literary effects, literature’s selective investment in textual materiality or immateriality, and the technological site-specificity of literary texts. The fact that these issues loom on the horizon at all, in a doomed site of urban erasure and promised regeneration, makes this doubtful textual embodiment even more precious. This may well be the reason why I cannot stop staring at it. If it had stayed within a book, its material textuality would have passed me by; as it is, I am held in thrall by it, repeatedly. What is it in the architecture of the book that is capable of housing the literary, whereas, exiled from its reproducible domesticity, it suddenly becomes orphaned, doubtful, inhospitable? A question of politics – what is the home of literature? Where will it be archived? – turns quickly into one of affect: how is a reader domesticized within a textual environment?

In his essay “The Book As Machine” (1972) the Canadian poet and scholar Steve McCaffery describes the functioning of the book’s capacity to store information and arrest the flow of speech in terms of “design”: “The book’s mechanism is activated when the reader picks it up, opens the covers and starts reading it … the book organizes content along three modules: the lateral flow of the line, the vertical

2 Jacques Rancière, Mute Speech:

Literature, Critical Theory and Politics (New York-Chichester:

Columbia University Press, 1998), 32.

3 Emergent properties “do

not inhere in the individual components of a system; rather these properties come about from interactions between components”. Catherine Hayles, My Mother

Was a Computer: Digital Subjects and Literary Texts (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 2005), 25.

or columnar build-up of the lines on the page, and thirdly a linear movement organized through depth (the sequential arrangement of pages upon pages)”.4 The

threefold modularity is segmented also by word breaks, by spacings between lines and paragraphs, and further framed by the blank borders of the page margins. As Bonnie Mak has shown in How the Page Matters 5 the technology of the book page is no less

layered, involving among other things the relationship between the recto and verso of the same page, as well as the relationship between two adjacent pages, both open at the same time. Our tactile familiarity with the book as well as the intimacy between secret and disclosure suggest that the machinic functioning of the book is not just a matter of spatial arrangements or given protocols. The notion of reading as a set of interpretive strategies should be expanded to include any kind of relationship taking place within the book environment, a material hybrid between human and machine. Thus, the opening of the book may well invite comparison to a digital switch (on/ off, reading/non-reading) causing the ‘activation’ of the book; yet, each opening is also a threshold leading to multiple openings and closings (the turnings of pages), which pace the reading as though simulating a progression into the depth of the book. Pace changes according to the interactions with page design and stylistic affordances (syntax slowing down or speeding up reading), according to the reader’s linguistic competence, as well as her interest, time-constraints and interruptions, attention. There is an onward flow accompanied by rhythmical counterpoint; yet recursivity and reversibility are always possible too. Reading’s durational performance may freely stop, pause, resume, go back, thus disordering time and performing its own asynchronous temporality. Book reading is a multi-dimensional experience, despite the seeming flatness of the page surface.

More than just an object or a machine, then, the book is a technological environment for a nexus of events that are molecular and non-specific, that is, neither reducible to a single plane (spatial, temporal, haptic, visual), nor to a rational schema of deliberation (the reader’s intentional acts or the text’s intended meanings). Reading events are, in this sense, post-human(ist): the reader’s subjectivity is not the only agent. Reading is also infra- and supra-subjective. This complex environment is what the Norwich Utopia does not reproduce despite its ostensible textual fidelity.

On the other hand, by betraying the text’s habitual materialization, it paradoxically returns it to us as a questionable property. Some might say that Macbeth’s No Place does not add anything to our reading of the original text, because it refuses to engage with it other than superficially, in other words, materially. On the contrary, I believe that this silent and practical refusal, embodied by a performative writing act instead of a reading, turns out to be a radical engagement, whose addendum – a differential performativity of the copy – is in the nature of the supplement. It subtracts literariness whilst performing, by way of negation, a contemporary spectre of Utopia. By refusing to read and let others read the textual and literary ‘wholeness’ of the original the brute force and weight of the inscribed building projects a contingent materiality back onto its acknowledged original: the printed book whose translated title and running text it shares.

4 Steve McCaffery and

bpNichol, “The Book as Machine”, in Jerome Rothenberg and Steven Clay, eds., A Book of the Book: Some

Works and Projections about the Book & Writing (New York:

Granary Books, 2000), 18.

5 Bonnie Mak, How the Page

Matters (Toronto: Toronto

The alternating appearance and disappearance of the literary qualifies it as an emergent property, that is, an event. Such property can be perceived here as an attenuation (what I have called a demergence) of the conditions under which we would be prepared to accept No Place as a genuine work of literature, if its recognition depended only on the survival of this singular text-token. The Eastern Electricity resting ground engages literature at its roots: a trembling ground letting us experience literature as vibrational matter in a state of becoming that has become all but invisible in its prevalent regime of materialization.

Digital Trembling

Choosing the Norwich site in order to stage a crisis between literature and the book, between text and matter, may seem a perverse move. After all, there are already established fields of research and critical interrogation where literature’s materiality has been foregrounded: historical book studies and ‘new philology’ (or ‘material philology’), for instance. Their cultural material turn has already questioned the myth of the text’s transparent reproducibility, explored textual difference, and undermined the original vs. copy binary.

These challenges, however, are being overshadowed by the ‘digital turn’ which has arguably established the terrain where the future destiny of literature – especially its archival transmission – is being decided. The newly transitional state of literature appears to coincide with its mutation and passage through digital conversion and into digital storage. The instability of the book form today compels us to look again at the naturalized bind between a historically contingent medium and its textuality, especially in the case of literature, even more fetishistically bound to the book. In fact, their intercourse has been instrumental in the invention of the literary text as the peculiar object of literary studies. Even though book technology is by no means dead, it has been vampirized by digitization to such an extent that it is unclear what is analogue or digital in a book today: what we call book is only one of its possible stages in the transitions and conversions between analogue and digital. Seeing the literary as the result of a contingent materialization will also help us resurrect suppressed relationships with performance, emergence, temporality, event site.

Digital technology reframes the meaning of textual and literary materiality in its generalized transition to digitality. It also revolutionizes the availability of literary texts: literature becomes another database. The potential for quantitative analysis of huge numbers of textual data is already leading away from the text as the paramount discrete unit amenable to interpretation towards corpora and metalibraries. One effect is a marked change in how literature is envisaged and, consequently, processed. Digital computation tends to put a premium on aggregate data, available through methods of “distant reading”: a kind of reading which is “almost not reading at all, but rather engages the abilities of natural language processing … to detect large-scale trends, patterns, and relationships that are not discernible from a single text or detailed analysis”.6 Whereas a literature made of books encourages modes of

6 Ibid., 39. For an example cf.

Katherine Bode, Reading by

Numbers: Recalibrating the Literary Field (London-New

close reading that seem to respond to their folded, intimate proximity, connected libraries of digital-born or digital-converted texts, ceaselessly migrating on and off-line, lend themselves to somewhat different practices: rhizomatic readings, metatextual interrogations, recombinant remixes.

In “Translating Media. Why We Should Rethink Textuality” Catherine Hayles has focused on the textual crisis determined by the passage from print to digital and argued for a careful discussion of their respective features.7 Interested in what happens to

print text when its medial environment changes, she argues that something ‘does’ happen: the translation from one medium to another never leaves the text unchanged. By speaking in terms of gains and losses she thus foregrounds the performing of difference, in marked contrast with those who prefer to naturalize the transition to digital as ‘business as usual’. Crucially for Hayles, digitality, involving conversion, can be brought under the rubric of translation, that is, of interpretive acts – an agency which she radically reformulates as a post-human hybrid between human and machine. As Hayles points out in discussing projects such as the digitization of the William Blake Archive, transitioning analogue texts towards their digital counterparts represents a significant challenge to concepts of literary text that eschew the materiality of medium: digitization ultimately undermines the illusion that a digital translation will save the text as ‘a whole’. The premise of the “imbrication of physical form with meaning” (266), in fact, leads to the opposite conclusion. Preservation is out of the question: if the text cannot be abstracted from its contingent materiality, digitizing the Blake Archive will certainly ‘not’ preserve it. No matter what choices we make, digitizing a text will only simulate it, that is, perform it differently. The paradigm of simulation effectively unbundles ‘literature’ as a package that cannot claim any privilege to pass unscathed through its digital transitioning. In unpacking and converting textuality the digital is no less material than it is performative: in the very process of its non-transparent translation it once again performs the textual as materially bound. We can see now why and to what extent the literary trembles in the process of its digital transition: it does so because every time it is reconstituted it will fail to stay the same. Just like any singularity or any event it is non-reproducible. A crucial layer of digital performativity concerns the technical operations of the code. No matter how effective the on-screen simulation of analogue texts − so that we might think that whatever conversion has taken place it is over once we start reading − the performativity of the digital has by no means ceased to work. It has merely shifted to the processes underwriting our interactions with the screen, even if interaction means ‘just’ reading. This is why a merely visual phenomenology is insufficient to uncover the performativity of digital texts. For as long as we abstract the visual as being the only sensory plane that grounds our reading, any interface – of the monitor screen no less than of the book page – will be taken to work in a visual mode.

Abstracted and disconnected from its whole media environment, the ‘visual’ field of textuality becomes ready to be naturalized so as to appear performatively inert: a transparent medium – in other words, no medium at all. It merely becomes the ground – unread by definition – for the figure of the text, thereby produced

7 Catherine Hayles,

“Translating Media: Why We Should Rethink Textuality”,

The Yale Journal of Criticism,

16.2 (2003), 263-290. Cf. also Catherine Hayles, Electronic

Literature: New Horizons for the Literary (Notre Dame, IN:

Notre Dame University Press, 2008), arguing for the distinct performativity of digital-born literary texts.

as ‘the readable’. Thus, the digital interface can continue to work as homologue to the printed page thanks to the misrecognition of the simulation performed through the interface effect.8 In constantly refreshing itself the monitor reiterates

its performance of visualization so that we can turn our undivided attention to the text. In its digital mode, text is stabilized through repetition, i.e. through controlled instability. The machine loops as our desiring machine: our desire to see a text sustains, and is sustained by, the machine’s performance as text ‘delivery’. In fact, as Hayles points out, a digital text ‘as such’ never exists as a completed artifact (267). When we are online, it is processed from distant servers, through data files, software programs, hardware, optical fibers and switching routers. When we are offline, digital text, resident as a file and saved in our computers or plugged into external memories, is becoming ⇔ unbecoming text at all time.

Each apparition of the selfsame text, reconstituted from data packets or bundles of digital bytes, is made possible by the software code, with its own syntax of command lines, its textuality. Machinic language functions as a performative, not so much preceding, rather as subsisting in phenomenic text. Alexander Galloway has defined code as “the only language that is executable”, a language more strongly performative than natural language.9 Whether stronger or not, digital performativity implies analogue

performativity, or at least performability: the capacity to be converted or translated, with attendant loss.10 The strength of digital performativity is reinforced by the

architecture that conceals it, the fact that it is programmed to hide its executable codes, disciplinary protocols and running programs behind thinner and thinner screens – thus mimicking immateriality –, if not behind the proprietary walls of copyrighted patents. Such performativity tends to strengthen the dubious effects of the material vs. immaterial binary in all the spheres of production and reproduction that are processed through its agency. Here, even the mystified relationship between literature, book and materiality stages a paradoxical reversal. Literary scholars who bemoan the end of literacy as they know it have a vested interest in validating the immateriality of the digital, so they can ascribe to it the evacuation of the material solidity of the printed book, even though it has been precisely the supposed transparency of its materiality that has undergirded the superior ‘immateriality’ of the text in its capacity to transcend physical barriers. Strategically foreclosed, materiality resurfaces now as what is being mourned, an abjected and reconstructed materiality that only serves to lend objectivity to the effect of literariness.

Of no less weight are the critical stakes lying in the legibility of depth and surface. To the extent that they persist as tropes even in digital mode, depth and surface are imbricated in discourses of visibility and invisibility that act in a predictably regulatory logic. Depth will ‘read’ surface as the medium covering the making-visible of itself. In turn, surface will be endowed with the special opacity that is the correlate of the luminousness of what is hidden by it. In other words, this medium never permits real loss, and the concept of mediation is rendered totally unproductive. Mediation has any sense only if it is allowed to be ‘poietic’, to institute a change, a being-in-relation.

8 Alexander R. Galloway, The

Interface Effect (Cambridge:

Polity Press, 2012), especially 69ff. The performative element of digital

textualization only becomes apparent when there is some fault or glitch.

9 Galloway, Interface Effect, 70.

On the performativity of code cf. Hayles, My Mother

Was a Computer, 49-50; on

software code’s legislative and executive powers cf. Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Programmed

Visions: Software and Memory

(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011).

10 On the loss of acts and

representations brought about by the book see Roger Chartier, The Order of Books:

Reader, Authors, and Libraries in Europe Between the 14th and

18th Centuries (Redwood City,

CA: Stanford University Press, 1994), 89-91.

One further step, however, needs to be made. If the literary effect has played an important role in regulating the visual mode of textuality, its regulation has not been done ‘for the sake of the text’. What makes it political is the fact that it is entangled in a textualization of reading, itself part – as Michel de Certeau has argued – of a historical disciplining of readership.11 In this sense, while the specific

object of literary studies has been what is literary in a text – and what is textual in the literary – the unspoken aim of its practice has been to establish what turns reading into a proper reading. The literal side of reading, its entanglement with the surface matter of the text, is what reading has commonly defined itself against.

Furthermore, as literary studies have tended to shape protocols of ‘writing’ about what a reading of a (specific set of) writing is, their literary effect has reined in both reading and writing: on the one hand, it has contributed to the idea of a complementarity between reading and writing, whereby a reading will have to be a reading ‘of ’ a specific writing; on the other, it has promoted legitimate kinds of metascripture shadowing the text’s writing, thus pushing into the background the mediation of their concurrent reading performances. The redoubled prioritization of writing in this heavily biased hermeneutical circle makes the reader’s subordinate performance opaque, enwrapped as it were by the presence to itself of a text that has already banished what does not belong to it.

It is to the performance of a reading ignorant of writing, then, that a materializing ‘occasion’ will be offered in the next section.

Composing the Reader

Does the fact that a reading cannot be completed successfully mean that there is no space for a performance of reading, that there is no reading that is being done? Meanwhile a reading space is being made out even before we know that it will be impossible to read. And a time for a reading is also being made free to allow for its possibility. Even a forestalled reading, a wrong reading, a reading emerging from and demerging into non-reading, is still a reading. It takes reading time to fail reading, if failure is measured by how much of the text is ‘lost’. In all these cases reading would not be an embrace between text and reader, but a struggle to read; there is reading insofar as the trembling distance of a medium is held.

11 Michel de Certeau, The Practice

of Everyday Life (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1988), 131-176.

Fig. 2: Rory Macbeth, No Place (Spiral), 2006, matt white emulsion on walls, Eastern Electricity, Norwich, © courtesy of the author.

An effect of the foregrounding of reading as event is that the text will appear as a trace that has truly forgotten its own writing performance, as though the two events – writing and reading – were doubly distant, not only temporally, but ontologically as well. As Pierre Macherey put it, “nothing precedes it [literature] on its own ground, not even the promise of a future site”.12 If reading is not the

future of writing, the text to which the reader responds to does not hail from its past, from whose performance it has been severed: it must hail from the present itself, as emergent practice.13 The historicity of the text is held in abeyance in the

present singular of the time of reading; in order to take place at all, reading must not be subsumed into the past history of the text’s writing, but produced as the ground for a new contingency that may once again be called historical.

Let us call this historicization a creation of new time – a rupture – within the temporal unfolding of (literary, textual …) history. According to Blanchot, reading is the space that lets the work ‘be’, without any further qualification. Reading becomes a creation of anonymity: the name of the author is erased, yet the reader, if he is truly reading, only forgets himself: “What most threatens reading is this: the reader’s reality, his personality, his immodesty, his stubborn insistence upon remaining himself in the face of what he reads”.14 To us this violent effacement

of the reader’s biography may seem too demanding a sacrifice. For Blanchot it is a sacrifice to the necessary space of reading’s interval: “It seems to be very difficult to preserve such an interval” (201). Indeed, it is as difficult to think of it as to preserve it. Preserving it implies giving it over every time, to another reading for instance. It is the multiplication of these reading performances, of these singularities, that, Blanchot acutely observes, gives us the illusion that works of art are ageless (202).

If, pace Blanchot, the performance of reading is taken to be subordinate and posterior to its originating writing performance, reading will tend to be cast in the passive or receptive mode, and the readers, flickering silently in the background, as subjects waiting to be empowered by a new politics of reading.15 Such progressive

rhetoric, of course, assumes that there is a reader to be activated, even though in reading “there already exists, though it is surreptitious or even repressed, an experience other than that of passivity”.16 Such is reading in its quotidian plane

of praxis, distinct from the disciplinary (writing) practices of literary criticism, a reading whose politicization brings to light the irrepressible outlaw practices, or tactics, that punctuate the ‘everyday’ and represent the connective tissue – the affective fabric, so to speak – of social life.

In the context of de Certeau’s interest in amateur practices, especially those defined in terms of consumption, reading acquires pride of place for at least two reasons. Firstly, it reconfigures space as a social practice intersected by divergent performances spectralizing the power relations imbricated in it. Secondly, as a ‘secondarized’ performance, reading can exert a powerful leverage in the battle to subvert the unequal distribution of economic and cultural value leading to certain practices being held productive whereas others are not. Unproductivity is in itself a product of a social debasement. Its negativity has to be upheld if we want to

12 Pierre Macherey, A Theory

of Literary Production (London:

Routledge, 1978), 72.

13 Cf. Jeremy Fernando, Reading

Blindly: Literature, Otherness and the Possibility of an Ethical Reading (Amherst NY: Cambria

Press, 2009).

14 Maurice Blanchot, The Space

of Literature (Lincoln-London:

University of Nebraska Press, 1989), 198.

15 A summary history of this

process would include such diverse works as Umberto Eco’s The Open Work (orig. 1962), Roland Barthes’ The

Pleasure of the Text (orig.

1973), Judith Fetterley’s

The Resisting Reader (1977),

Michel de Certeau’s The

Practice of Everyday Life (orig.

1980), Jacques Rancière’s The

Emancipated Spectator (orig.

2008).

16 De Certeau, Practice of

acknowledge the relative autonomy of a social plane of creativity for which that unproductive ‘nothing’ is after all the ordinary currency sustaining its survival as heterotopia.

Enter the reader as a poacher. As a poacher, the reader steals from the text, or rather from the ‘order’ of the text, intended as a progressive accumulation of signs to be treasured up into a final hoard of meaning. Her textual performance of “advances and retreats, tactics and games” (175) carves out a heterotopic nomadism in relation to the text, whose linear purpose is double-crossed by the poacher’s lines of flight. Her peculiar strategy of following, yet deviating from, the text produces a pleasure in what is called “escapism”. Yet, what exactly is she running away from? Isn’t there a pleasurable escapism in running away from the text? Reading has no place, we are told surprisingly. The text appears not to be the place where the reader can be found, or find herself. Stealing from it, she is also a bit of a burglar in a palace of words that are, yet are not, her own.

The unproductive character of non-linear mobility is related to the temporality of reading vis-à-vis the processes of work and work subjectivation. In contrast with writing, whose performance stocks up a treasure of time and invests in representation, reading is an activity that “takes no measures against the erosion of time (one forgets oneself and also forgets), it does not keep what it acquires, or does it so poorly …” (174). Its scandal is manifold: it neither saves time against its ruinous advance nor saves the text; it is not acquisitive; it is uneconomical in terms of work economy, which banks on a surplus and would value reading only as additive knowledge. From this surplus will also depend one’s own sense of activity, measured in terms of output.

How can we value the reader in ways that do not already make her dependent on a text, as a reader of whatever?17 De Certeau starts from a strikingly affected

body: “We should try to rediscover the movements of this reading within the body itself, which seems to stay docile and silent but mines the reading in its own way: from the nooks of all sorts of ‘reading rooms’ (including lavatories) emerge subconscious gestures, grumblings, tics, stretchings, rustlings, unexpected noises, in short a wild orchestration of the body” (175).

His description expands the reading space to include an embodied site where an event produces an unexpected surplus. These discharges are a symptom that the performance of reading is releasing a bodily remainder rendered obscure to signification. In the reader’s grotesque body reading appears to re-enact the underlying cut or rupture between writing and speech that de Certeau sees at the root of modern scriptural economy. In The Practice of Everyday Life the French theorist recapitulates the disciplinary installation of the scriptural apparatus, which, “inseparable from the ‘reproduction’ made possible by the development of printing”, excised the authority of the “Voice of the people”.18 Reading has

become the subjected Other of writing, a kind of ordered orality brought into line with the text; a genealogy of modern ‘literacy’ will reveal the traces of the fissure between reading and writing inscribed on the reader’s body. Every singular reading,

17 Borrowing the term from

Agamben, I mean a reading that is neither particular nor universal. The whateverness of reading leaves its singularity to be, a space of difference where the reader may preserve its unthought-of.

18 Cf. de Certeau, Practice of

Everyday Life, 131-132 and the

whole chapter 10 on “The Scriptural Economy”.

according to de Certeau, performs the history of the power relationships invested in the separation between body and matter, orality and scripture; it is in this sense a new event of that history. No reciprocity is possible between writing and reading, no comparable equivalence or homology. No wonder that the reader’s body is shattered, by pleasure as well as guilt. Else, why would this noisy body perform in secret nooks and ‘lavatories’?

This is not the whole story, though. De Certeau traces out another body, the less obscene and more contemporary figure of the silent reader. She has learnt to withdraw her body from the intense possession by the text – evident in voiced reading or reading aloud – by creating a distance from which the text is objectified as a visual terrain that can be scanned, skipped and roamed. Are we sure, though, that a visual distancing of the text allows for “the condition of its [the body’s] autonomy”? Can the silent reader’s bodily engagement be limited to “the mobility of the eye” (176)? In other words, can reading be purified from its affective waste product, from shame?

It seems it cannot, though in a quite different sense, at least if we read Eve K. Sedgwick reading Silvan Tomkins on affect. Towards the end of “Shame in the Cybernetic Fold” the posture associated by Tomkins with the primary affect of shame – lowering of eyelids and eyes, hanging of head – is compared to that of reading.19 However, the association is no longer with repression and guilt-complexes

– shame as reaction and escape into a closeted world – but with a force field that exerts enough attention to create a world. Indeed, this affect, freed from the double bind of pleasure and repression, is turned unashamedly into one of the primary forces of world-making: “The additional skin shimmering as if shrink-wrapped around a body-and-book, or body-and-playing/working environment, sharply and sheerly delineates the conjunction and composition, making figural not escape or detachment, but attention, interest” (21). Immersion in reading hardens a second skin, the signal of an affirming creation of, rather than a seclusion from, a world. Its materialization no longer has at its core an interiorized subjectivity whose psychoanalytic drama invests even those who would subvert it. A new relationality links the social and the material, the cognitive and the affective in a common ontology that escapes the closed circuit of human-centred worlding. Sedgwick argues for an engagement with the material and biological constitution of our life-world by taking her lead from Tomkins’ psychobiology.

Trusting shame as an affect rather than hiding it as a symptom certainly reconfigures the reader into a different body. Except it is no longer just his or her body, it is a composition moved by affect. Both Blanchot and de Certeau have noted the reader’s forgetful body. How can forgetting be reconciled with affective embodiment in reading? Sedgwick’s suggestion is: by embodying differently, by locating the sources of affect not in some hidden fold of the subject, but in emergent compositional forces enmeshed in heterogeneity, needing only a skin to provide a temporary interface. These multiple skins materialize relations no less forceful for being contingent. Thus, relation gives rise to the composition Sedgwick calls

19 Eve K. Sedgwick and

Adam Frank, “Shame in the Cybernetic Fold: Reading Silvan Tomkins”, in Sedgwick and Frank, eds., Shame and Its

Sisters: A Silvan Tomkins Reader

(Durham NC: Duke University Press, 1995), 20-21.

book-and-reader. Yet this boundary remains an open-ended interaction between inside and outside. The affect that sustains the ostensible ‘introversion’ of the reader neither means that she is knowing herself in her own foldedness, nor that this folding space is of the kind private vs. public.

There is no reader who needs to bear the brunt of the inscription of the law, since reading, as an interface event and a temporary in-between, is above all the affirmation of a compossibility, what Deleuze would call the assemblage (agencement) of book-and-reader. This reading site fits neither the disciplinary regime of scriptural economy, nor the object-centred disciplinarity of literary studies. By a scalar shift in attention Sedgwick’s affective stance cathects an interest in heterogeneous conjunction rather than in the dual drama of object and subject. In this sense, it leads us into the performance of the non-specific, the formless that is taking form, the emergent.

A Dissensual Site

An interest in assemblages is not only significant because of its chance to materialize relations, but also because it focuses on the conditions that sustain them and on the properties they assume or are seen to assume by being performed over time. In the beginning I have referred to the “historical mode of visibility” of literature as a sensible condition that sustains the persistence of a literary object, even in the face of the contingent materiality of its visible textuality, the reliance on the simulated transparency of its technological interface, and the non-identity of the two (writing and reading) performances that realize it. This mode of visibility is, in other words, performative. Since the persistence of any visibility has an obvious relation to aisthesis, while the occlusion of its compossibilities always effects the preservation of social and disciplinary partitions, it is crucial to theorize – even just to see – the foreclosed indeterminacy of those partitions, their contingency. This is where Jacques Rancière’s proposal of ‘radical equality’ can be useful. I am interested in how Rancière brings together aesthetics, a “partition of the sensible, of the visible and sayable, which allows (or does not allow) some specific data to appear”,20 and politics, which imparts a specific distribution of the sensible to the

effect of confirming or disrupting the established partitions or domains of the social world.

20 Jacques Rancière, “The Politics

of Literature”, SubStance, 33.1 (2004), 10. On the aesthetic regime and the distribution of the sensible (partage du sensible) see Jacques Rancière, The Politics

of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. by Gabriel Rockhill

(London: Continuum, 2004).

Fig. 3: Rory Macbeth, No Place (Spiral), 2006, matt white emulsion on walls, Eastern Electricity, Norwich, © courtesy of the author.

Keystone to his politics of the sensible is Rancière’s concept of “aesthetic regime”, which establishes a paradoxical yet fruitful relationship between art and life. Breaking away from the rules and codes that determine the hierarchical adequation of form to subject matter (e.g. through genres), the aesthetic regime vindicates the autonomy of art as heterogeneous and separate from life. However, by claiming a capacity to recreate life on account of its own separation art discovers at the same time its own heteronomy as an ‘art of life’. Its capacity to imbue life with new perceptions installs art in the gap between sense and meaning, thus realizing the capacity of dissensus, a synthetic term that joins the political with the aesthetic. While the technologies of ‘arts’ do differ, the point lies not in their difference, but in art’s promise of overcoming the differences already distributed. Although this does not justify our indifference to formal means, neither does it tolerate an apriori distribution of the sensible that would autonomize each field of artistic creation over and against its heteronomous relation with life. By affirming the creation of a differently sensible world this promise is necessarily non-specific, its political premise lies in equality.

This is where radical equality can be seen to affect both the makers of art and the ordinary lives of those who are affected by it and come to have a share in its dissensual effects. Radical equality posits an equal capacity – common to the point of being anonymous, ordinary, everyday – to forge associations and dissociations, that is, a translative capacity in terms of a dissensual creation of meaning. Such a commonplace multiplication of lines of flight opposes not just any notion of specification that would predetermine art’s ways of redistributing the sensible, but also any notion of specialization intended as a set of tools that have already performed their ‘specific’ inspection of an art object in order to pre-empt its newness. Therefore I see Rancière’s approach as helpful in sustaining our attention to sites, events and encounters that dissociate the already constituted (i.e. distributed and partitioned) elements of any artistic object and the capacities it engages.21

My interest in Rory Macbeth’s No Place lies precisely in his dissensual deployment of literature.22 No longer in the book, the Norwich Utopia redistributes the sensible

by a transcription that is more than just visual. Recalling the use of protest graffiti on walls, public buildings, bridges and motorway gantries, his writing does not rely on a blank page but on architectural surfaces that are pre-existing and as such already inscribe urban space.23 Citing this practice but also overturning it and

overdoing it, this Utopia seems to play a stranger game: instead of using anonymity to express oneself, Macbeth authors a bluntly inexpressive performance of copying.24

Furthermore, by installing More’s text on a derelict building awaiting demolition Macbeth marks a temporal deadline for its performative effect. He writes in the gap, in the temporal lag between an already pronounced death sentence and the promise of a (speculative) revolution lying more prosaically in urban regeneration. He writes

Utopia in the seemingly most inert temporality of all: that of the ruinous present,

a duration coming into its own as a conflation between a past that is condemned and a future that has already marked its occupation.

21 Cf. Jacques Rancière, On

the Shores of Politics (London:

Verso, 2007), 32: “The essence of equality is not so much to unify as to declassify, to undo the supposed naturalness of orders and replace it with controversial figures of division”.

22 Christopher Warley, Reading

Class Through Shakespeare, Donne and Milton (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 2014) discusses both versions of Macbeth’s No Place as displacements of the ghost of communist utopianism in the post-industrial era.

23 A 1970’s instance of protest

graffiti in East London was the writing “G. Davis is innocent” springing up everywhere as a campaign against his robbery conviction. Rory Macbeth, email message, 2 January 2014.

24 On uncreative and

conceptual writing see Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith, eds., Against

Expression. An Anthology of Conceptual Writing (Evanston

IL: Northwestern University Press, 2011). Another work by Macbeth is excerpted there:

By grafting a literary text that has survived the centuries onto a late 19thC

power plant, originally associated with electrical modernity yet now redundant and doomed, Macbeth has folded temporal and spatial politics into one. We have the privilege to see a ruin before the end has actually come. Utopia’s new homeless location stares at us from a site that is literally our unheimlich (post)-modernity; the utmost banality of post-industrial sites has become so heimlich that we need its literal monumentalization in order to see it anew, albeit as unreadable artwork. Wrenched out of its architectural book form, literature, too, is tacked onto the more modest architecture of a former power plant, deployed not so much to point towards transcendence but to the materiality of brick-and-mortar history. Both architectures have their own pretensions, their own utopian ambitions. It is apt, in a way, that they should share the same resting ground.

Nevertheless, the literal collapse of two utopias – industrial modernity and book literature – into a single No Place is far from nihilistic, or resolved. The way out of its terminal implosion lies less in the perfect moment when the building will be actually torn down – thus ‘realizing’ the work’s meaning according to its author – than in the repetitive drudgery that we have not seen: the painstaking labour of its writing. As I am led to respond to it with a reading that remains unachieved, Macbeth’s uneconomical labour of copying Utopia strikes me as the most political form of its publication here and now. Through the glaring mismatching of classical text, volatile surface and would-be reader so as to create a new dissensual composition,

No Place folds them all into the prophetic fold of a commonly shared interval. As

this folding is perceived the site becomes suddenly alive, contrary to the planned obsolescence of market speculation. The ‘permanent’ paint Macbeth has used on the site ironically marks his ‘precarious’ occupation of its deadline.

A recent collection of essays suggests an oxymoron for a site like this: future ruin.25 Here the future is visible as a ruin ‘in’ and ‘of ’ the present, as if to fulfil

Agamben’s notion of con-temporaneity: “a singular relationship with time that adheres to it through a disjunction and an anachronism”.26 Yet what seems crucial

is that a certain time has been newly occupied. It is true that Macbeth’s layering of intrusive temporalities – including our own failed readings – is neither able to cancel nor to shift the deadline. Actually, it seems to reinforce its power by folding the destiny of its writing into the destiny of the otherwise anonymous building. In so doing, though, the artist repoliticizes what would otherwise have lain inert through the unproductive labour of art and the equally unproductive motility of our looking, until the site trembles under our very eyes.

Future ruins become actable. The prophecy of this ruin is spelled out by a writing on the wall that is legible, yet unreadable. It turns out that the lag between the two is the time and space that we have, once again.

*

No Place (Spiral) is still standing in Norwich. No Place (Kingly Digs) has gone.28

25 Davide Borrelli and Paola

Di Cori, eds., Rovine future.

Contributi per ripensare il presente

(Milano: Lampi di stampa, 2010).

26 Giorgio Agamben, “What

Is the Contemporary?”, in

Nudities, trans. by David

Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011), 11.