The effect of future self-continuity on delaying immediate

gratification in virtual reality.

*Behavioral evidence showed that individuals have present-biased preferences, namely they put more weight on the present than on the future and these preferences lead to dynamic inconsistency. The lack of connectedness to future self was proposed as a cause of impulsive behavior and irrational intertemporal choice. In this paper we study the effect of the experience of future self-continuity in a CAVE virtual environment on delaying immediate gratification. Participants choose between sooner or later monetary options in different experimental treatments. We find that they decide to differ with higher probability when are exposed to virtual reality because this experience increases their connectedness to future self. Our results support the hypothesis that behavior in virtual environments can be useful to allow a fresh approach to the analysis and understanding of choice over time.

CCS CONCEPTS • Human-centered computing • Human computer interaction (HCI) •

Interaction paradigms • Virtual reality

Additional Keywords and Phrases: intertemporal choice, present bias, connectedness,

virtual reality.

ACM Reference Format:

First Author’s Name, Initials, and Last Name, Second Author’s Name, Initials, and Last Name, and Third Author’s Name, Initials, and Last Name. 2018. The Title of the Paper: ACM Conference Proceedings Manuscript Submission Template: This is the subtitle of the paper, this document both explains and embodies the submission format for authors using Word. In Woodstock ’18: ACM Symposium on Neural Gaze Detection, June 03–05, 2018, Woodstock, NY. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 10 pages. NOTE: This block will be automatically generated when manuscripts are processed after acceptance.

1 INTRODUCTION

Intertemporal choice requires a prediction of future tastes that is influenced by factors as routines, habits, mood, social influences and context (Loewenstein and Prelec 1992, O’Donoughe and Rabin 2005). People exhibit commonly present-biased preferences, since they put more weight on the present than on the future and, as a consequence, show dynamic inconsistency (Thaler 1981, Loewenstein 1996). The implications of this behavior were analyzed in the lab and in the field by showing that individuals tend to understand the directions in which their tastes will change, but systematically underestimate the magnitudes of these changes. In particular, they are prone to exaggerate the degree to which their future tastes will resemble their current tastes (Loewenstein 1996). This can explain the very common propensity to underestimate the strength and the drawbacks of all types of addiction (Frederick et al. 2002).

The causes of the present bias have been discussed across various disciplines. While Scitovsky (1976) emphasized the role of emotions since present rewards are more arousing than future rewards do, Elster (1983) claimed that it can be explained by the presence of multiple egos, or at least of two or more conflicting selves that overlap with each other over time. The resource-depletion model of self-control assumes that willpower is an exhaustible resource and that “[...] controlling one’s own behavior requires the expenditure of some inner, limited resource that is depleted afterward.” (Muraven and Baumeister 2009). Neuroscience research provided evidence that dual neural system can determine present bias as a consequence of the parallel activity of prefrontal cortex and limbic system (McClure et al. 2004, Faralla et al. 2015). Most notably, Parfit (1971), (1984) and (1987) argued that the neglect of the future self can arise from a failure of the imagination according to which people treat the future self as if it is in fact a different person. Parfit (1984, pp. 205–206) defined psychological connectedness as “the holding of particular direct psychological connections”, including the sharing of memories, intentions, beliefs, desires, and other psychological features across time, and argued that “My concern for my future may correspond to the degree of connectedness between me now and myself in the future [...] since connectedness is nearly always weaker over long periods, I can rationally care less about my further future.” (p. 313).

If present and future selves are disconnected, it is conceivable that people consider the future self as a different individual and make intertemporal choice as they take decisions for others. By using neuroimaging evidence, Pronin and Ross (2006), Ersner-Hershfield et al. (2008; 2009), and Mitchell et al. (2011) support the hypothesis that future self-discontinuity can produce present-biased preferences. As a consequence, long-term unpresent-biased decision-making would be directly dependent on the level of connectedness between today and tomorrow’s selves. Frederick (2003) claims that “the separation between selves may be just as significant as the separation between persons, and discounting one's "own" future utility may be no more irrational than discounting the utility of someone else.” (pp. 1-2). This is to say that “it is not important whether in various senses, a person actually does change over time; rather, what matters is how much a given individual feels he or she will be the same person over time.” (p. 4). This model is tested by Frederick (2003) showing that connectedness cannot be identified exclusively as similarity between present and future selves. Bartels and Rips (2010) assessed the effect of

psychological connectedness by submitting students a series of hypothetical matching questions between amounts of money with different time delays. They showed that participants exhibit asymmetry between gains and losses since they preferred benefits to occur before large changes in connectedness but preferred costs to occur after these changes. Hershfield et al.’s (2011) analyze the impact of three definitions of connectedness: similarity, vividness and positivity. The more the future is seen as similar to the present, the more it is perceived to follow a realistic and vivid course, and the more it is seen positively, the more likely people are to delay immediate gratification and to take rational intertemporal decisions. Hershfield (2011) tested this model to the choice of pension plans and provides evidence that allowing subjects to interact with age-progressed digital renderings of themselves will cause them to allocate resources across time more efficiently. In his experiment the experience of LIVE (Low-Immersive Virtual Environments) (Innocenti 2017) would assist the imagination to create future self-continuity.

Indeed, High-Immersive Virtual Environments (HIVE) (Innocenti 2017) may represent an effective tool to simulate future events self-continuity by making them more similar, vivid and positive. Virtual reality (VR) can be considered as a tool which encompasses virtual unreality: “We do not say that it is “exactly as real” as physical reality but that VR best operates in the space that is just below what might be called the “reality horizon”. […] VR is a difficult task – since it encompasses what can be done in physical reality (for good or evil). But even more, since it is VR, we emphasize that we can break out of the bounds of reality and accomplish things that cannot be done in physical reality. Herein lies its real power.” (Slater and Sanchez-Vives 2016, pp. 2-3). By forging an association with future events, VR can connect tightly the present self with the “other” future self in a digital environment (Lanier 1992).

The efficacy of immersive environments in triggering empathy for others through virtual embodiment is widely supported by experimental evidence (Peck et al. 2013, Banakou et al. 2016, Hasler et al. 2017, Banakou et al. 2018, Bertrand et al. 2018, and Seinfeld et al. 2018). By replacing a person’s body by a virtual one, emotional and cognitive empathy towards others can be induced (van Loon et al. 2018) and this reaction would favor prosocial behavior and enhance the motivation to increase others’ welfare (Zaki and Ochsner 2012).

Our paper’s main research question is the extent to which VR can modify implicit biases such as present bias, that are likely rooted in our personality and that can be modified only by self-control with great effort. To analyze this issue, we tested in an experiment conducted in a CAVE environment the effect of exposure to future self-continuity on the choice between immediate and delayed monetary rewards. Although we do not make participants virtually embody an avatar, we emphasized future self-continuity by submitting them the experience of time passing in order to test if this treatment reduces the impact of present bias and make future gratification more desirable.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 explains the experimental design and the technical equipment. Section 3 presents results of the laboratory treatments. Finally, in Section 4 we draw conclusions and make recommendations for further research.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Participants

64 Siena University undergraduates participated in this study and they were recruited with the software Hroot (Hamburg Registration and Organization Online Tool) (Bock et al. 2014). The study session for each participant lasted around 45 minutes. Each participant was paid in euros according to the choice made in the experiment with no participation fee. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the University of Siena. All participants were given basic information about the experiment without revealing the purpose of the study and signed an informed consent form when they agreed to take part of the study.

2.2 Equipment

The virtual environment was implemented in Unity 3d and delivered visually in a fully immersive CAVE automatic virtual environment. The dimensions of the sidewalls are 266cmx200cm, and the dimensions of the top and bottom walls are 3X3 m. The walls are projection panels, on which the stereoscopic image is displayed using back-projection from four projectors with WQXGA resolution, frame rate 120 hz and 4000 ansi lumens. Participants stand in the middle of the room and wear glasses that enable them to see the image in 3D and are equipped with a device for detecting the spatial position. Monitoring the position of the participant's head in the space and the direction of its view is used to recalculate and correct the projected images and the stereoscopic perspective of the observer. Movements in the virtual world are mediated by a joystick in the participant's hands. Projectors are connected to four workstations, working as cluster each with P5000 16GB graphics card and G-Sync card and located in the same room. A standard optical tracking system consisting of four cameras (with attached infrared emitters) is used to detect the user’s head position and orientation. The cave is endowed with a 5.1 surround sound system with total power (RMS) of 500W.

The non-virtual control treatment was computerized by using z-Tree software (Zurich Toolbox for Ready-made Economic Experiments) (Fischbacher 2007) and participants made their choices on a desktop computer.

2.3 Experimental design

To examine the effect of VR on intertemporal choice, we used a 2 × 2 experimental design, with group (VR Exposure and Experimental Control) as the between-subject variable and choice (Self-Present vs. Self-Future and Other-(Self-Present vs. Other-Future) as the within-subject variable.

2.3.1 VR Exposure sessions

The VR Exposure sessions were located in the CAVEs available at the LabVR of the University of Siena submitted in the CAVE. The VR simulation was designed to induce connectedness between present and future selves. Following Hershfield (2011), we aimed at inducing future self-continuity by fulfilling three requisites:

Similarity. Although it was not feasible for the participant to embody an avatar, the identification with the present self was obtained by stressing the continuity between present and future events.

Vividness. Experience was thought to be visually impressive without any reference to the object of experimental test concerning monetary rewards and submitted after VR exposure.

Positivity. The virtual simulation should be perceived as a pleasant experience and we tried to minimize the perception of the CAVE limited space.

The participants were shown a virtual environment representing a camper trip. The experience was set in a solitary journey of 14 days in a camper van through nature (i.e., the Yellowstone National Park). At the beginning of the experience the participant was located inside the camper and was asked to experience a moment of five days. Every day was a different scene, which starts with a fade-in. The different scenes are associated with suggestive and small panorama environmental events and are represented on a map that comes updated with milestones and small notes. The exit from the camper triggers the animation of the day change. Each time the day change, the map of the journey, the panorama, and the notebook as well as the calendar date are updated. Calendar dates are also announced by the radio station. On the dashboard, different actions are available to the player, such as take the map/notebook and observe it, listening music on the radio station, tear off the page on the calendar, open and exit the door, looking at the environment, or experiencing day and night rotation.

In this way we satisfy the conditions required. For vividness, the passage of time was represented intuitively by the various stages of the journey and reinforced by clear (new scene, map update travel diary) and detailed changes and updates (calendar pages, words on the radio), For similarity, we chose the theme of travel as an effective way to connect present to the future by means of a path of change. Finally, for positivity, the setting was lively, intense and memorable and thus it is difficult to be seen negatively.

2.4 Procedures

In the VR exposure sessions, initially participants were submitted a demographics questionnaire that was anonymous and ask for age and gender. Then they entered the CAVE room and familiarized themselves with the virtual environment. The participants were given as much time as needed to adapt. This orientation phase typically took five minutes. Next, each participant was exposed to the camper trip experience as described above. After the VR exposure, in the self-present vs. self-future condition, a one-shot intertemporal choice test was administered. This behavioral test consisted in the choice between receiving a certain amount of money, smaller and sooner, today and a higher amount, larger and later, delayed (i.e., “€20 today vs. €25 in 2 weeks”). During this part of the experiment, subjects were sitting in front of the computer screen on which the choice was presented and were allowed to select the key A or L on the keyboard for respectively selecting the smaller, earlier alternative or the larger, later one. The more immediate option was presented on the left side of the computer screen. No time limits were given for the choice. Immediate payments were paid in cash before exiting the lab if

the choice was the today amount. In case of delayed payment, they were paid in their classroom with no transaction costs. After this one-shot test participants were presented a series of intertemporal choices between two different monetary options (Other-Present vs. Other-Future condition). More specifically, each subject completed a task involving 24 gain and 24 loss trials. For each trial, subjects’ preference was elicited by asking participants to choose between a hypothetical smaller, sooner option, available at time t, and a larger delayed one, available at time t + 1 as in the one-shot experiment (e.g., “€5 today vs. 5.50€ in 2 weeks”). The stimuli list was taken from Faralla et al. (2015). Participants were told that they were choosing on behalf of another person. However, no information was provided about the other’s preferences in terms of intertemporal choice. Again, the more immediate gain/loss was presented on the left side of the computer screen. Subjects were allowed to select the key A or L for choosing one of the two alternatives. No time limits were given. For this part of the experiment, no reward was obtained.

Finally, participants were submitted the assessment questionnaires to evaluate the overall procedure.

In the Experimental control sessions, participants received the same task and followed the same procedure, except that they were not exposed to the VR experience.

To summarize the experimental phases were the following: Labsi recruiting platform (gender balanced students) Demographics questionnaire

Orientation phase in VR Lab (Only VR exposure) VR Exposure (Only VR exposure)

Intertemporal Choice Test Assessment questionnaire Payment in cash

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Results were analysed using Ri368 3.5.2, developed by the R Foundation for Statistical Computing (R Core Team, 2015), and the analysis was performed by means of non-parametric methods due to the characteristics of the sample. According to our experimental Thesis (Ts. 1), participants decide to differ with higher probability when are exposed to VR time passage with respect to the hypothetical case because are more connected to their future self. Moreover (Ts. 2), participants decide to differ with higher probability for others than for themselves when they are exposed to VR time passage with respect to the hypothetical case.

Participants age ranged from 20 to 32 years old (mean age = 24.06; SD = 2.49). The median age was comparable in the two groups. The median age was indeed 24.28 (SD = 2.04), in the Experimental Control sample, and 23.84 (SD = 2.89), in the VR Exposure one. Of the 64 included participants, 55% was female (56%, Experimental Control, and 53%, VR Exposure).

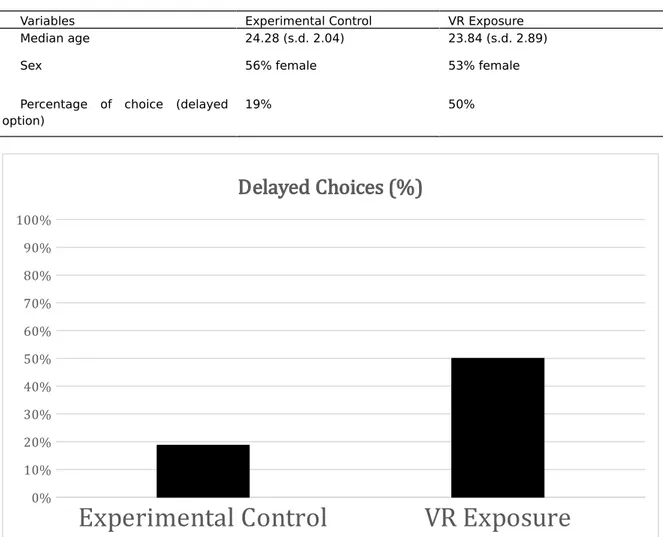

The percentage of participants that selected the delayed option in Experimental Control group was 19%. This percentage raised to 50% in the VR Exposure treatment (p -value < .05; Figure 1). This result is in line with the hypothesis that VR exposure leads to more farsighted preferences. There was no gender difference between the two treatments.

Table 1 summarizes the main descriptive results and characteristics of the sample by condition.

Table 1: Main descriptive results and characteristics of the sample by condition (Experimental Control vs. VR Exposure) (n = 28)

Variables Experimental Control VR Exposure

Median age 24.28 (s.d. 2.04) 23.84 (s.d. 2.89)

Sex 56% female 53% female

Percentage of choice (delayed option)

19% 50%

Experimental Control

VR Exposure

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Delayed Choices (%)

Figure 1. Percentage of delayed (larger and later) options chosen by condition (Experimental Control vs. VR Exposure).

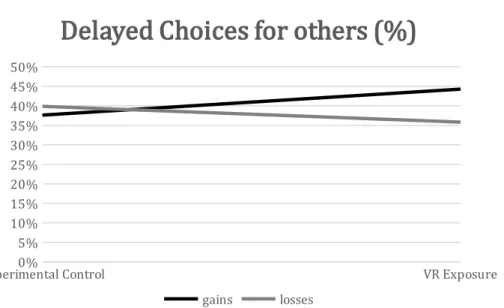

The analysis of the Other-Present vs. Other-Future treatment was separately performed for gains and losses. As for gains, the percentage of participants that selected the delayed option in the two experimental groups was slightly lower in the Experimental Control (38%) than in the VR Exposure treatment (44%) (p -value < .01). For losses, the percentage of delayed options was instead higher in the Experimental Control than in the VR Exposure condition (40% vs 36%), although difference was not significant (Figure2).

Experimental Control0% VR Exposure 5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40% 45% 50%

Delayed Choices for others (%)

gains losses

Figure 2. Percentage of delayed (larger and later) gain options chosen by condition (Experimental Control vs. VR Exposure) in the Other-Present vs. Other-Future treatment.

As for gender, males increased the preference for delayed option in the VR Exposure condition for gains 35% Experimental Control versus 46% VR Exposure condition; p -value < .01) but increased for losses (49% Experimental Control versus 29% VR Exposure condition; p -value < .001). In contrast, females increased the choice of larger, later options in the VR Exposure treatment for both gains and losses (33% and 42%, for losses, and 40% versus 42%, for gains; p -value < .05 and not significant, respectively).

The main objective of the study was the testing of possible VR exposure effects in intertemporal choice.

In line with our Ts. 1, exposure to future self in VR reduces present bias on future monetary reward.

Moreover (Ts. 2), the choice to defer is more likely with future others than with future selves (at least for gains), which influence the present selves, because people focus more on subjective needs and concerns of present selves (with respect to future selves or others).

Consistent with our proposed mechanism, we expected this trend to be attenuated for decisions involving the present self when participants were encouraged to break out of their current emotional experience and decide apart from those emotions.

4 CONCLUSIONS

Behavioral evidence showed that individuals have present-biased preferences, namely they put more weight on the present than on the future and these preferences lead to dynamic inconsistency. The lack of connectedness to future self was proposed as a cause of impulsive behavior and irrational intertemporal choice. In this paper we study the effect of the experience of future self-continuity in a CAVE virtual environment on delaying immediate gratification.

Participants choose between sooner or later monetary options in different experimental treatments. We find that they decide to differ with higher probability when are exposed to virtual reality because this experience increases their connectedness to future self. Our results support the hypothesis that behavior in virtual environments can be useful to allow a fresh approach to the analysis and understanding of choice over time.

REFERENCES

Banakou, D., Hanumanthu, P. D., and Slater, M. (2016). Virtual embodiment of white people in a black virtual body leads to a sustained reduction in their implicit racial bias. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10:601. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00601 Banakou, D., Kishore,. S., and Slater, M. (2018). Virtually being einstein results in an improvement in cognitive task

performance and a decrease in age bias. Front. Psychol. 11:917. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00917

Bartels, Daniel M.; Rips, Lance J. (2010). "Psychological connectedness and intertemporal choice". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 139 (1): 49–69. doi:10.1037/a0018062.

Bertrand, P., Guegan, J., Robieux, L., McCall, C. A., and Zenasni, F. (2018). Learning empathy through virtual reality: multiple strategies for training empathy-related abilities using body ownership illusions in embodied virtual reality. Front. Robot. AI 5:26. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2018.00026

Ersner-Hershfield, Hal; Wimmer, G. Elliott; Knutson, Brian (2008)."Saving for the future self: Neural measures of future self-continuity predict temporal discounting". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 4 (1): 85–92.

Ersner-Hershfield, Hal; Garton, M. Tess; Ballard, Kacey; Samanez-Larkin, Gregory R.; Knutson, Brian (2009). "Don't stop thinking about tomorrow: Individual differences in future self-continuity account for saving". Judgment and Decision Making. 4 (4): 280–286.

Faralla, V., Benuzzi, F., Lui, F., Baraldi, P., Dimitri, N., & Nichelli, P. (2015). Neural correlates in intertemporal choice of gains and losses. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 8(1), 27–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/npe0000032

Frederick, S. (2003). Time preference and personal identity. In G. Loewenstein, D. Read, & R. Baumeister (Eds.), Time and decision (pp. 89–113). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation

Frederick, Shane, George Loewenstein, and Ted O’donoghue, (2002) “Time discounting and time preference: A critical review,” Journal of economic literature, 2002, 40 (2), 351–401.

Hasler BS, Spanlang B, Slater M (2017) Virtual race transformation reverses racial in-group bias. PLoS ONE 12(4): e0174965. Hershfield, Hal E; Goldstein, Daniel G; Sharpe, William F; Fox, Jesse; Yeykelis, Leo; Carstensen, Laura L; Bailenson, Jeremy N (2011). "Increasing Saving Behavior Through Age-Progressed Renderings of the Future Self". Journal of Marketing Research. 48 (SPL): S23–S37

Innocenti, a. (2017). “Virtual reality experiments in economics”, Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics. 69, August 2017, 71–77.

Loewenstein G (1996). "Out of Control: Visceral Influences on Behavior". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 65 (3): 272–292. doi:10.1006/obhd.1996.0028.

Loewenstein, George, and Drazen Prelec (1992) “Anomalies in intertemporal choice: Evidence and an interpretation,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, pp. 573–597.

Mitchell, Jason P.; Schirmer, Jessica; Ames, Daniel L.; Gilbert, Daniel T. (2011). "Medial Prefrontal Cortex Predicts Intertemporal Choice". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 23 (4): 857–866.

O'Donoghue T, Rabin M (2015). "Present Bias: Lessons Learned and To Be Learned". American Economic Review. 105 (5): 273–279. doi:10.1257/aer.p2015108

Parfit D. (1971) Personal Identity. Philos. Rev., 80:3–27.

Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and persons. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Parfit, D. (1987) Reasons and Persons. Oxford: Clarendon Press

Peck, T. C., Seinfeld, S., Aglioti, S.M., and Slater,M. (2013). Putting yourself in the skin of a black avatar reduces implicit racial bias. Conscious. Cogn. 22, 779–787. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2013.04.016

Pronin E, Ross L. (2006) Temporal differences in trait self-ascription: when the self is seen as an other. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol.; 90:197–209.

Seinfeld, S., Arroyo-Palacios, J., Iruretagoyena, G., Hortensius, R., Zapata, L. E., Borland, D., et al. (2018). Offenders become the victim in virtual reality: impact of changing perspective in domestic violence. Sci. Rep. 8:2692. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19987-7

Thaler, Richard, (1981) “Some empirical evidence on dynamic inconsistency,” Economics Letters, 8 (3), 201–207.

van Loon A, Bailenson J, Zaki J, Bostick J, Willer R (2018) Virtual reality perspective-taking increases cognitive empathy for specific others. PLoS ONE 13(8): e0202442. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0202442