1

Classe accademica di scienze sociali

Settore di Scienze Politiche

Anno Accademico 2018 – 2019

Provincialising diversity

Social diversification and polarisation in Italian inner areas

Candidato: Federico RossiRelatore

Prof. Gabriele Tomei

Tutor

3

Abstract

The work aims to understand diversification processes in Italian inner areas through a super-diversity lens, by testing the enforceability of this approach outside the traditional context of global cities. The main research questions concern if peripheral localities in Italy are experiencing diversification processes to the point that it can be possible to apply super-diversity framework and which are peculiar or common patterns of these processes compared to other types of localities. The first part focuses on the development of a comprehensive theoretical approach to super-diversity through the integration of other theoretical frameworks, that can allow to overcome some limitations of the concept, especially those related to the understanding of inequalities. Moreover, academic literatures on urban scale and New Immigration Destinations are also used to further reframe super-diversity outside urban environments. The second part deals with the Italian context, by using comparative methods to understand diversification patterns in peripheral areas, their peculiarities compared to urban centres and the possible consequences.

4

Sommario

Introduction ... 5

Theoretical framework ... 8

Super-diversity: an ongoing theorisation ... 8

A comprehensive approach to super-diversity ... 13

Urban scale, New Immigration Destinations and super-diversity ... 18

Diversification in peripheral localities ... 23

A new geography of spatial inequality in Italy ... 23

Immigration patterns towards Italian inner and peripheral areas... 27

Diversification among peripheral localities in Italy: is there super-diversity outside the city? ... 33

Conclusion ... 39

Bibliography ... 44

5

Introduction

The focus on diversification in academic literature is closely linked to the relatively recent attempt to overcome the exclusive focus on ethno-cultural variables in migration studies and the multicultural perspective underlying that setting (Meissner, 2015; Vertovec, 2019). For this reason, the concept of super-diversity, that represents one of main lens by which contexts resulting from diversification are conceived, is still not fully understood in all its theoretical and empirical implications, as well as with regard to its consequences in different social environments (Meissner and Vertovec, 2015; Foner and others, 2019). In the following years to its theorisation, super-diversity has been mostly applied in global cities and in North European countries with a long tradition of immigration (see for example: Phillimore, 2010; Crul and others, 2013; Wessendorf, 2014; Meissner, 2016; Scholten and others, 2019), while very few attempts to test this framework in different contexts has been made (see for example: Crul and Schneider, 2010; Pardilla and others, 2015; Becci and others, 2016). In Italy, super-diversity has often been conceived as a mere backdrop for the study (Ambrosini and Bonizzoni, 2012) or replaced by hyper-diversity (Barberis, 2017; Barberis and others, 2017), while the focus has always remained narrowed on large cities in Northern Italy.

Although many scholars acknowledge the fact that implications and configurations of super-diversity largely rely on the context in which this situation emerges and they also claim the need to understand patterns of diversification in non-global cities or in localities with more recent immigration flows (Vertovec and Meissner, 2015; Scholten and others, 2019), there is still a severe lack of studies about super-diversity in peripheral or rural areas (McAreavey, 2017). Therefore, the present work primarily tries to start bridging the gap, by looking at Italian inner and peripheral localities through a super-diversity lens. The term “locality” is used here as a substitute for

6 “city”, in order to avoid limitations inherent to the often too narrow definition of this latter term. The reference for this shift is Glick Schiller and Çağlar’s definition of locality as the concrete space in which the studied dynamics take place (Glick Schiller and Çağlar, 2009), that is operationalised in this research by using Italian municipalities as the core spatial units. The main research questions concern if rural and peripheral localities in Italy are experiencing diversification processes to the point that it can be possible to apply super-diversity framework and which are the peculiar or common patterns of these processes compared to other types of localities. In order to fulfil these aims, the present study uses mainly comparative methods, by processing available data from various official sources. Moreover, due to the explorative nature of this work, further questions dealing with the implications of different diversification processes on incorporation of newcomers or on social relations and cohesion are not directly addressed and they are deferred to subsequent studies.

This work is divided into two main sections: a first part focused on the development of a comprehensive theoretical approach to super-diversity; and a second one that tries to test the application of that framework in the Italian inner and peripheral areas. The first chapter reviews academic literature on super-diversity, by highlighting the strength and the aspects of novelty of the concept, as well as the main criticisms and limitations. Then, through the integration of other theoretical framework in the classic super-diversity theory, it tries to develop a comprehensive approach to diversification processes, in order to try overcoming some of the most critical issues of super-diversity. However, only part of this theoretical framework is effectively employed in this work with the aim to interpret data and comparison’s results, since in these understudied contexts preliminary explorative research is necessary before moving to deeper field studies, which would be necessary to completely implement the

7 proposed framework in all its implications. Finally, other useful concepts to understand diversity in rural and peripheral contexts are introduced and used to further reframe super-diversity in the light of research’s aims. The second chapter directly deals with the Italian context, by starting with the outlining of the general policy aspects that concern relevant elements of the research, such as labour, immigration and spatial production. The focus is then narrowed to inner and peripheral areas through the reconstruction of recent immigration history of these places, by also pointing out its evolution in the context of the economic crisis. In the last section, quantitative data from various official sources are elaborated in different indicators to compare diversification patterns in rural or peripheral areas and in central more connected zones, in order to trace peculiarities of different contexts and their possible consequences in the light of the theoretical framework proposed in the first chapter.

8

Theoretical framework

Super-diversity: an ongoing theorisation

The concept of diversity is often perceived in social science as problematic or ambiguous and, despite the large set of empirical studies, its definition is still disputing (Titley and Lentin, 2012; Vertovec, 2012). Isar (2006), for example, traces the evolution of the notion from the initial conception as a simple fact lied to human condition to its transformation into a normative

meta-narrative, which supports the claims of individuals and groups out of

dominant social and cultural norms. More recently, Vertovec (2012) understands diversity as a set of ideas and practices, carried and reproduced in multiple ways, that can gradually become a background understanding of a given society. According to Vertovec, diversity is becoming part of the social imaginary thanks to its ambiguous, multivalent and commonplace nature, allowing people to be more aware of categories such as ethnicity, gender, age and disability. Following this path, Tasan-Kok and others (2014, p.8) propose a more operationalizable notion of diversity as the presence of a number of socio-economic, socio-demographic

and ethnic groups within a certain spatial entity. Diversity can therefore

be understood in this framework as a set of relevant categories of difference. In its turn, diversification must be kept distinct from the concept of diversity and it can be defined as the process by which population is becoming more and more different along many axes for various reasons (Vertovec, 2012). Diversification is the linking element between concepts of diversity and super-diversity. The need to focus on diversification processes emerges in the context of the so-called “multicultural backlash” from those scholars trying to review multicultural theory without renouncing to hold together diversity and social cohesion (Vertovec and Wessendorf, 2015). One of the first works following this idea is David Hollinger’s book about multiculturalism in the United States (1995), in which he proposes the concept of diversification of diversity. According to him, the combined influence of new and more diverse migration flows and the increasing sensibility towards different kinds of

9 diversity has led to the proliferation of categories of diversity and, consequently, to overcome multiculturalism itself. Hollinger’s framework has subsequently been transferred into European context by other scholars (see for example: Martiniello, 2006) and it has become one of the starting points for the diversity turn in migration studies, which tries to overcome the previous almost exclusive focus on ethno-cultural variables by shifting the focus from concepts like ethnicity, culture or race to a more comprehensive idea of diversity (Vertovec and Wessendorf, 2010).

The concept of super-diversity emerges in the wake of this diversity turn with a twofold meaning: it is a summary term, which identifies the interplay of new significant variables in a context of increasing diversification (Vertovec, 2007); but it is also a post-multicultural concept, which tries to overcome the fragmenting nature of multiculturalism, while keeping together a high level of respect towards diversity and the creation of a strong collective identity (Vertovec, 2010). As regards the first dimension, the main issue concerns which variables should be considered in a super-diversity approach. Many scholars continue to conceive it as a quantitative increasing of ethnic or national diversity, despite this perspective has been explicitly criticised by the main super-diversity theorists (Meissner, 2015; Grzymala-Kazlowska and Phillimore, 2018; Vertovec, 2019). In his first definition of super-diversity, Vertovec (2007) mentions at least six groups of variables to take into account, mainly related with migratory issues (ethnicity and country of origin, legal status, generation of immigration, labour market experiences, gender and age profiles, spatial distribution). More recently, Meissner (2015), whilst remaining within migration studies, proposes an alternative framework based on seven more general variables, that are gender, age, legal status, occupational role, education, time of residency and independency of migration. However, one of the most complete approach to super-diversity is proposed by Pardilla and others (2015), who elaborate a specific methodological table to operationalise the concept of super-diversity in

10 South European cities based on three main dimensions (Actors, Social Networks and Neighbourhood).

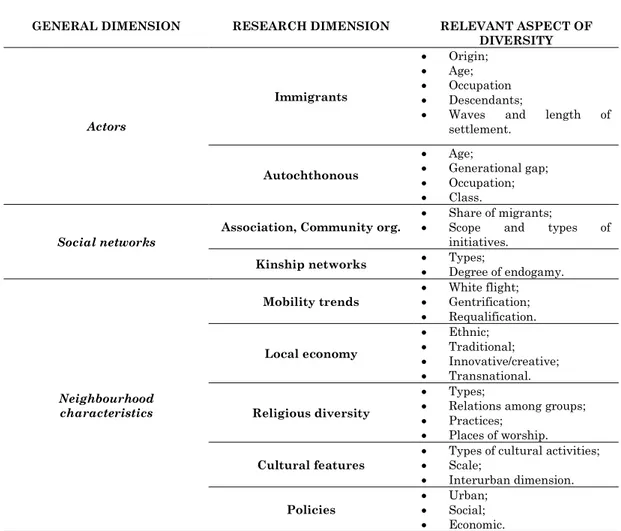

GENERAL DIMENSION RESEARCH DIMENSION RELEVANT ASPECT OF DIVERSITY Actors Immigrants • Origin; • Age; • Occupation • Descendants;

• Waves and length of settlement. Autochthonous • Age; • Generational gap; • Occupation; • Class. Social networks

Association, Community org. • • Share of migrants; Scope and types of initiatives.

Kinship networks • • Types; Degree of endogamy.

Neighbourhood characteristics Mobility trends • White flight; • Gentrification; • Requalification. Local economy • Ethnic; • Traditional; • Innovative/creative; • Transnational. Religious diversity • Types;

• Relations among groups; • Practices;

• Places of worship.

Cultural features • • Types of cultural activities; Scale; • Interurban dimension.

Policies • • Urban; Social; • Economic.

Table 1. Super-diversity framework elaborated by Pardilla and others 2015 (p.628)

Such theorisation has three main strengths, that distinguish it from the others. Firstly, it is multi-layered and it allows to contemporarily consider super-diversity at individual, relational and contextual level. Then, it includes in the super-diversity framework not only migrant communities, but also autochthonous ones and social spaces where intergroup encounters can occur. Finally, it considers super-diversity as a relational concept, as also proposed by Meissner (2016), by looking at how diversity is perceived and negotiated through social interactions in different contexts. This relational nature also enables to understand why some scholars have focused on particular subjects as drivers of super-diversity, such as migrant families (Ambrosini, 2015) or pioneer migrants (Wessendorf, 2018).

11 As pointed out above, super-diversity also presents itself as a

post-multicultural concept (Vertovec and Wessendorf, 2010; Meissner, 2015).

While some scholars claim that the prefix “post” does not mean an opposition to multiculturalism (Vertovec, 2010; Kymlicka, 2010), such concept also has its roots in the debate about what to do with presumed incompatible cultures in a multicultural frame (Gozdecka and others, 2014; Tasan-Kok and others, 2014), as emerged for example in a part of feminist studies after Susan Moller Okin’s famous article on multiculturalism and women’s rights (Okin, 1999). Defining super-diversity as a post-multicultural term primarily means that diversity should not merely conceived through ethno-cultural variables (Vertovec, 2010). But the emphasis on social cohesion and its confinement in migration studies also potentially expose this concept to contradictions inherent post-multiculturalism, which allows for an increased control of diversity by public authority and too often neglects cleavages within groups or asymmetrical power dimensions fostering particular kinds of diversity (Gozdecka and others, 2014; Tasan-Kok and others, 2014; Hall, 2017). A large part of critics towards the concept of super-diversity, especially those coming from post-colonial scholars, insists on these elements: according to them, this concept creates an illusion of equality in a highly asymmetrical

world (Ndhlovu, 2016, p.34), since it would contain a powerful sense of social romanticism (Makoni, 2012, p.193), which would bring to the

de-politicisation of difference and it would not allow to engage with process of exclusion (Ramadan, 2011; Anthias, 2012). Further developments of Vertovec’s approach have partly coped with these criticisms (Grzymala-Kazlowska and Phillimore, 2018) but, as argued in the next section, they could be also more completely tackled by adopting a comprehensive approach to super-diversity through the integration of other useful theoretical frameworks.

The scholarly debate about super-diversity and its contents has also brought to try overcoming the concept itself through the inclusion of new sets of variables. In this sense, one of the most recent and structured

12 attempts to elaborate an alternative and more complete framework is the concept of hyper-diversity. As argued by Tasan-Kok and others (2014, p.6), hyper-diversity refers to an intense diversification of the population in

socio-economic, social and ethnic terms, but also with respect to lifestyles, attitudes and activities. The first difference between super-diversity and

hyper-diversity is the number and the type of considered variables, since the latter adds three central aspects of the social life to demographic, socio-economic and ethno-cultural elements addressed by super-diversity. According to scholars using a hyper-diversity perspective, the diversification of lifestyles, activities and attitudes is equally relevant and visible as variables linked to traditional cleavages in shaping everyday encounters in neighbourhoods or other spatially-defined localities (Tasan-Kok and others, 2014; Peterson, 2017). In this sense, hyper-diversity allows to look at important elements, such as consumption habits, youth cultures, transnational practices or attitudes towards social spaces, which are at the core of a significant part of urban and migration studies and which are often ignored by super-diversity scholars (Berg and Sigona, 2013; Barberis and others, 2017; Domaradzka, 2018). Moreover, hyper-diversity also distances itself from post-multiculturalism, that is blamed to continue reifying social and ethnic groups, by considering how diversity in attitudes, lifestyles and activities lead to the creation of new relevant in-groups differences (Tasan-Kok and others, 2014). It is thus possible to overcome the traditional assumption that individual practices and beliefs are directly affected by ethno-cultural background and socio-economic position and to recognise the growing status discrepancy in contemporary societies, as well as the emergence of new possible citizenship practices (Boros and others, 2016; Domaradzka, 2018). However, although hyper-diversity contributes getting over some limitations of super-diversity, it does not still resolve central problems, such as the lack of a strict definition of variables or the difficulty to properly address inequality.

13

A comprehensive approach to super-diversity

In our perspective, adopting a comprehensive approach to super-diversity means to try overcoming limitations inherent to this concept through the integration of other theories, that can help developing a more complete and operationalizable framework. As also argued by some scholars using a super-diversity lens, diversification patterns, particularly those linked to migration-related variables, are partially produced by asymmetrical border regimes and power-related dimensions, which cannot be fully addressed by a super-diversity approach alone (Hall, 2017; Aptekar, 2019). For these reasons, some fundamental concepts can be included in this perspective in order to fully address issues related to diversification, particularly intersectionality, multiplication of labour and border as method and, finally, the distinction between social production and social construction of space.

Although some scholars have already proposed to integrate super-diversity and intersectionality (Crul, 2016; Khazei, 2018), many attempts to understand peculiarities of both these frameworks often exclusively focus on their different geographical and theoretical reference contexts, that are Europe and migration studies for the first one and United States and feminist theory for the latter (Geerts and others, 2018). For this reason, as a preliminary step for this paragraph, it is important to clearly distinguish between the concepts of intersectionality and super-diversity. Regarding this argument, it does not seem convincing the distinction outlined by Meissner and Vertovec (2015), who, based on earlier definition of intersectionality, argue that the difference between these notions would reside in categories to be considered: race, class and gender on one side, and a set of migration-related elements on the other one. In fact, both intersectionality and super-diversity have been characterised in their evolution by the widening of relevant aspects of diversity to be considered, which makes very difficult to conceive them as containing pre-defined and fixed categories (Lykke, 2015; Meissner, 2016). Instead, based on the literature about both these topics, the present work proposes a distinction

14 based on the object addressed by the two concepts. Following this perspective, intersectionality primarily deals with a layered and manifold conception of subjectivity, which allows to understand new trajectories of alliances and discriminations in social life (Yuval-Davis, 2006; Cho and others, 2013), while super-diversity mainly refers to the result of a process of diversification, that shapes a particular social context and origins new social structures (Crul, 2016; Grzymala-Kazlowksa and Phillimore, 2018). In this sense, the integration of an intersectional perspective within a super-diversity framework could make possible to better look at power structures and groups’ formation, by using a more complex definition of diversity that takes into account peculiar differences created by the interplay of diverse categories at individual level. As argued by post-colonial scholars that were mentioned before (Ramadan, 2011; Makoni, 2012; Ndhlovu, 2016) and also by some intersectional ones (Anthias, 2012), scholars dealing with super-diversity often conceive diversification as the mere fragmentation of groups along a growing number of axes and they consequently fail to consider power structures that emerge from or precede processes of diversification. Although this is not always the case (see for example: Phillimore, 2015), such lack of connection between issues of diversification and stratification leads to define diversity just along horizontal axes and to ignore the vertical ones, but also to reify groups, by ignoring different experiences within them. Intersectionality thus allows to focus also on the intertwining of diversity axes within groups and to shed light on new patterns of discrimination or new possible alliances between and within groups. Moreover, the academic literature on intersectionality can also contribute providing a solution to a common problem of both super-diversity and intersectional approach, that is the potential boundless proliferation of variables identified by the so-called et cetera problem (Villa, 2015). Such possible contribution has already been noted by Meissner (2015), who incorporates Lykke’s idea (2015) of integrating the classic intersectional triad of class, gender and race with other context-based and strictly defined categories.

15 As regards the concepts of multiplication of labour and border as method, the main theoretical reference is the seminal work of Mezzadra and Neilson (2013), in which they define the border as a dispositive detached from the mere geographic dimension, that follows individuals shaping their sociality and trajectories in social life and labour market. As for intersectionality, although from a different point of view, the inclusion of this theoretical perspective within a super-diversity approach contributes to link social diversification and social stratification and it enables to take into account interconnections between fundamental variables such as legal status and labour market experiences. Moreover, as intersectionality ensures a better problematization of gender dimensions in super- or hyper-diversity frameworks (Geerts and others, 2018), the idea of multiplication of labour also allows to rethink ways through which class and labour market experiences are operationalised, by considering how new forms of capitalism have shaped labour in contemporary societies (Neilson, 2009; Mezzadra and Neilson, 2013). This concept tries to integrate and overcome the classical notion of the division of labour through the identification of three key ways, in which class structures have been getting more complicated: intensification, that means labour colonises more and more aspects of individual lives; diversification, that identifies the complexification and differentiation of the search for relative surplus value; and heterogenization, that points out the creation of new labour statuses, positions and hierarchies through the promotion of precarity, informality and vulnerability (Mezzadra and Neilson, 2013; Clare, 2020). These processes have thus complicated labour market experiences to the point that it is no longer possible to focus only on income and work position to define class, but it is necessary to consider other elements, such as the degree of precarity or informality of the occupation, but also the value assigned to the job (i.e. migrants with residence permit for work, that need the job to keep legal their stay). In this sense, since these conditions are generally related to broader dynamics, Mezzadra and Neilson’s theory allows to consider the influence of general policy level on local dimension and to link the local dimension to the global one and the State.

16 The last set of concepts, from which a super-diversity framework could benefit, concerns the distinction between social production and social construction of space. Lefebvre (1974, 1976) firstly conceives social production of space as the mean by which what he calls the reproduction of social relations of production takes place, assuring the survival of capitalist structures. Then, such idea is further developed by other Marxist urban scholars and, in particular, by Harvey (2001), that defines the capitalist production of space as those processes that shape social space according to capitalist social relations and accumulation. By partially dividing this notion from its Marxist background, Setha Low (1996, 2009) relates it to the pre-existing concept of social construction of space and she proposes a more operationalizable definition of both. She thus defines the social production of space as all those factors – social, economic, ideological

and technological – that result, or seek to result in the physical creation of the material setting, while the social construction of space is conceived in

her theory as the actual transformation of space – through people’s social

exchanges, memories, images and daily use of the material setting – into scenes and actions that convey symbolic meaning (Low, 2009, p.24).

According to her, the contextual power relations shape the material elements of urban space, but, at the same time, people can reproduce or change its meanings through their agency. Such theoretical framework has already been integrated within a super-diversity approach by Lundsteen (2017) and it can be useful for understanding some aspects often neglected by the academic literature on super-diversity. For instance, the concept of production of space can shed light on how asylum seekers’ reception center are placed on the territory through the interaction between local and national dimension, while at the same time the notion of social construction of space can reveal the different ways in which residents relate to it, fostering or hindering the incorporation of newcomers in the local space. In this sense, the concept of social construction of space also helps to better define attitudes, lifestyle and practices, that are at the core of hyper-diversity, by also highlighting their relations with other elements. A comprehensive approach to super-diversity is thus based on the integration

17 of other relevant frameworks within the core theory, in order to better understand issues of inequality and power, as well as to more precisely conceive the intertwining nature of diversity axes among themselves and with the surrounding space. More specifically, by adopting this perspective, it is possible to look at diversity and diversification not as something just spontaneously occurring, but as a mix of individually pre-determined elements (i.e. gender, origin, age, etc.), that assume particular meanings in specific contexts and in relations among them, and other aspects shaped by power relations and structural constraints at different levels (i.e. labour experience, legal status, etc.). Such new model can thus be summarised by amending Pardilla and others’ (2015) framework to include the previously exposed concepts and its implications:

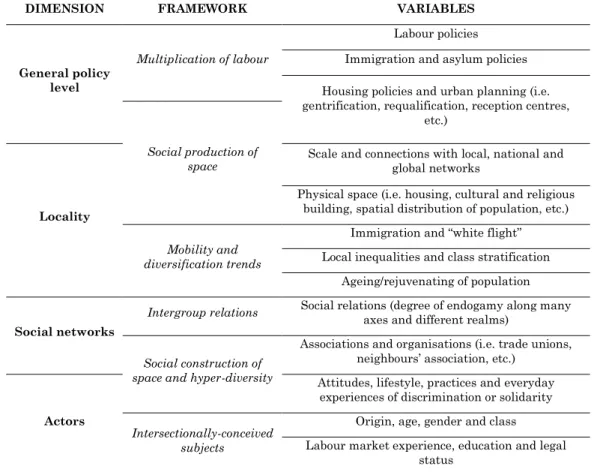

DIMENSION FRAMEWORK VARIABLES

General policy level

Multiplication of labour

Labour policies Immigration and asylum policies Housing policies and urban planning (i.e. gentrification, requalification, reception centres,

etc.)

Social production of space

Locality

Scale and connections with local, national and global networks

Physical space (i.e. housing, cultural and religious building, spatial distribution of population, etc.)

Mobility and diversification trends

Immigration and “white flight” Local inequalities and class stratification

Ageing/rejuvenating of population

Social networks

Intergroup relations Social relations (degree of endogamy along many

axes and different realms)

Social construction of space and hyper-diversity

Associations and organisations (i.e. trade unions, neighbours’ association, etc.)

Actors

Attitudes, lifestyle, practices and everyday experiences of discrimination or solidarity

Intersectionally-conceived subjects

Origin, age, gender and class Labour market experience, education and legal

status

Table 2. Variables to be considered by adopting a comprehensive approach to super-diversity

However, since the aim of the present work is limited to test the possible application of this theory outside the usual contexts of the so-called global cities, this scheme will be only partially employed in the following discussion. In this regard, such framework will be mainly used in the next

18 chapter to interpret the data and the results of the comparison in order to provide a preliminary understanding of how diversification occurs and how it can develop in the studied contexts, by postponing to further studies the task to fully implement this theoretical scheme and especially the aspects concerning intergroup relations, hyper-diversity and the social construction of space.

Urban scale, New Immigration Destinations and

super-diversity

Since the emerging of the “local turn” in migration studies (Zapata-Barrero and others, 2017), a large part of this field has shifted its focus from the national level to the city. However, most studies still remain exclusively focused on large cities deeply integrated within global networks, the so-called global cities, and they ignore different patterns of incorporation or diversification that can affect other types of settlement (Glick-Schiller and Çağlar, 2009; Räuchle and Schmiz, 2019; Scholten and others, 2019). Indeed, academic literature in the field of urban studies has tried in different way to deconstruct the predominance of the narrow conception of city as a large ideologically and geographically dominating urban environment. Some scholars have focused on the peculiarities of small and medium size cities related to large ones, by arguing that long-studied dynamics in urban studies can take a very different shape according to the city’s dimension (Bell and Jayne, 2009; Jayne and others, 2010; Servillo and others, 2017). However, such distinction brings out strong definitory problems, since very different cities are labelled as small, so that it is very difficult to merely use the population size for differentiating among types of settlement (see for example: Rogaly and Qureshi, 2013; Lundsteen, 2017).

Another way to properly disentangle the concept of city, that allows avoiding vagueness in definition, is through the adoption of a scaling approach. The concept of scale originates in works of notable urban scholars, such as Lefebvre, Harvey and Smith, in order to conceptualise how social dynamics and power relations are shaped at different spatial

19 dimensions (urban, regional, national and then global) and to overcome the limits of the “horizontal cartography”, that looks at the city as a particular type of territory merely defined in opposition to the suburban and the rural (Jones III and others, 2016; Brenner, 2019). The work of Glick Schiller and Çağlar (2006, 2009) reframes such theory through a new and more operationalizable definition of scale, that they conceive as the differential

positioning of cities determined by the articulation of institutions of political, cultural and economic power within regions, states and the globe

(Glick Schiller and Çağlar, 2009, p.188). They firstly identify small-scale localities in opposition to global ones by pointing out as indicators of small-scale positioning the difficulty in attracting capitals for high-skilled sectors and in creating opportunity for high-skilled workers, relatively small finance and banking sectors, lack of money for local welfare, a shrinking local tax base, a relatively small size of the population and the remoteness to other urban centres (Glick Schiller and Çağlar, 2006). However, they subsequently elaborate a more accurate four-fold partition of localities, from top- and up-scale to low- and down-scale, according to their connection and their competitiveness within global networks. They also build on the works of scholars that have dealt with global-local relations and scale to argue that contemporary dynamics of neoliberalism set in motion continuous “rescaling processes”, that make cities change their hierarchical positions according to many factors (Brenner, 2001; Swyngedouw, 2004; Glick Schiller and Çağlar, 2009). According to them, immigration and diversification are important features affecting these processes, but, at the same time, the scalar positioning itself influences their patterns, since a different incorporation model for newcomers corresponds to each locality model (Glick Schiller and Çağlar, 2009). From this starting point, Scholten and others (2019) further revisit this theory in the context of super-diversity literature, by arguing that locality scales should not be considered as closed categories, but as a continuum, in which different localities are placed between the extreme points of top- and down-scale localities.

20 Thus, such theory allows to understand and compare diversification and incorporation processes among localities, that are different from the widely studied large cities with a relatively long tradition of immigration and strong economic performance. However, in order to better conceive peculiar dimensions of diversification outside the generally addressed contexts, this research can also benefit by integrating in this framework the concept of New Immigration Destinations (McAreavey, 2017; McAreavey and Argent, 2018). Indeed, contemporary diversification does not only involve the categories we listed above, but also immigrants’ motivations and settlement spaces. Such situation results in immigration flows towards rural and peripheral areas, some of which are not entirely new, such as those driven by the agricultural labour demand, while other are more recent phenomena, such as the relocation of asylum seekers in mountain areas or retirement migration (Nelson and Nelson, 2010; Lichter, 2012; Corrado, 2017; Di Gioia, 2017; McAreavey, 2017). The notion of New Immigration Destinations (NIDs) tries to capture these emerging contexts, by arguing that the very different environments of rural and peripheral areas, as well as the recentness of immigration in these places, rise a new set of challenges and opportunities related to migration issues (McAreavey and Argent, 2018). Moreover, the framework seems to be particularly fitting for South-European countries, such as Italy, Spain and Greece, characterised by an overrepresentation of immigrants within agricultural and care sectors and recent large asylum seekers’ flows (Calavita, 2007; Labrianidis and Sykas, 2012; Collantes and others, 2014), as well as for countries of more recent immigration, such as Ireland, Austria or East-European and Northern countries (Wallace and others, 2013; Munkejord, 2016; Gretter and others, 2017; Woods, 2018; Gauci, 2020). According to McAreavey (2017), NIDs in these countries are generally rural or peripheral localities struggling to remain economically viable in a context of socio-economic and demographic change, in which young population flight increases and firms abandon manufacturing-dependent communities by taking advantage of globalisation of production.

21 By reconnecting such framework with Glick Schiller and Çağlar’s scalar model, NIDs seem to mainly correspond to low- and down-scale localities, in which migrants’ incorporation and diversification are thus affected not only by their positioning within global networks, but also by the fact that such processes are entirely or partially new in these localities. The possible application of super-diversity in these contexts is still a very little studied issue (McAreavey, 2017), but, since different types of locality are characterised by different social structures and consequently provide different opportunities and constraints for immigration and diversification patterns (Glick Schiller and Çağlar, 2011; Miraftab, 2016), it is important to try disentangling if and how these processes occur in similar contexts. Moreover, many scholars have acknowledge that we still know very little about which positive or negative consequences can originate from the rising of super-diversity in different contexts (Foner and others, 2019), although Wessendorf’s (2014) pivotal study on Hackney neighbourhood in London points out the potential emergence of a situation of commonplace diversity in super-diverse environments. Academic literature on hyper-diversity provides a more multifaceted insight on consequences of diversification in many European cities, by also considering different types of urban settings (see for example: Alexandri and others, 2017; Barberis and others, 2017; Budnik and others, 2017; Fabula and others, 2017; Lelévrier and others, 2017), but they lack a comparative perspective and they still exclusively focus on large cities. In order to try narrowing this gap, this research argues that the first two dimensions of the theoretical model proposed in the previous section could be useful in testing the enforceability of super-diversity in low- and down-scale NIDs. Moreover, the review of the academic literature on rural migration in Europe already allows to highlight some peculiar characteristics of diversification in these localities. For instance, diversification processes related to gender and labour market experiences can be observed in the demand for low-paid, low-skilled workers in agriculture and care services for elder people, two often gendering and precarious sectors of employment for immigrants (Munkejord, 2016; Gretter and others, 2017; McAreavey, 2017; Sampedro

22 and Camarero, 2018; Woods, 2018). Another potentially relevant issue concerns rural depopulation of young people, which is partially counterbalanced by the inflow of young immigrants (Collantes and others, 2014; Galera and others, 2018; Dax and Machold, 2020). Starting from this theoretical standpoint, the present work aims to test the suitability of super-diversity framework within low- and down-scale NIDs in Italy, by also trying to identify how diversification occur in these places compared with up- and top-scale cities with longer history of immigration.

23

Diversification in peripheral localities

A new geography of spatial inequality in Italy

The issue of spatial inequality in Italy has generally been addressed by looking at the traditional cleavage between the more industrialised North and the more rural South (Musolino, 2018; Asso, 2020). Although the North/South divide still remains crucial, it does not consider some peculiar patterns of Italian uneven development related to other kinds of asymmetries, mainly the urban/rural one, that has widely been observed within the whole European Union in last years (González, 2011; Iammarino and others, 2019; Giannakis and Bruggeman, 2020). From this starting point, also in order to avoid the ambiguity and the potential oversimplification linked to the urban/rural dichotomy (Brenner, 2019), many scholars have proposed to adopt a socio-spatial perspective based on single localities (González, 2011; Kühn, 2015; Pezzi and Urso, 2016), which in the case of Italy can be reflected in the six spatial categories proposed by Barca and colleagues (2014) to conceive inner and central areas. Such classification is based on the proximity of single municipalities from centres providing fundamental services, such as education, health and mobility. In this perspective, inner areas, that are those farther from these poles, represents more than 60% of national territory and about a quarter of the total national population (Barca and others, 2014). According to the main literature on the topic, inner areas have also shared in the last decades some declining patterns, which concern not only the distancing from basic services, but also an increasing depopulation, the reduction of occupation rate and the loss of the capability to use their territorial capital (Barca and others, 2014; Bertolini and Pagliacci, 2017; Basile and Cavallo, 2020; Mei, 2020).

24

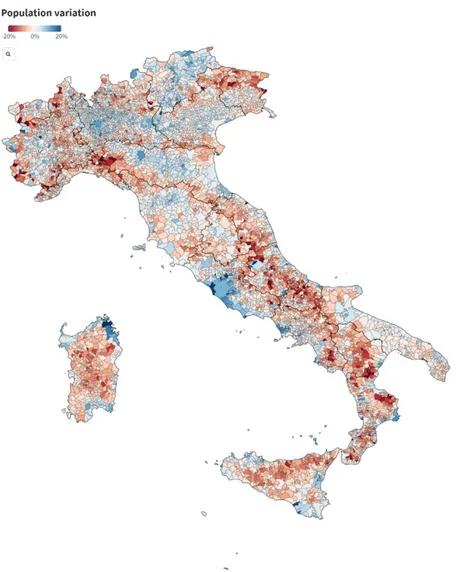

Figure 1. Population variation by municipalities – Map created with Flourish based on Istat data

Indeed, most of these areas have suffered a long-run process of marginalisation, which has reduced the negotiation power of local administrations against other public and private actors, so that extractive or controversial structures, such as mines, power plant or landfills, have been more and more relocated in these zones, without actually producing innovation or benefits for the local population (Barca and others, 2014; Basile and Cavallo, 2020; Mei, 2020). Moreover, as in other similar contexts in Europe, the global dynamics of contemporary capital have made industries less dependent on specific territories and consequently fostered offshoring processes, which have jeopardised many previously manufacture-dependent peripheral localities (Rodríguez-Pose, 2018; Urso and others, 2019; Gallo and Pagliacci, 2020).

25 The decline of small- and medium-size manufacturing centres has also led to income stagnation and fall in employment within their surrounding suburban and rural areas, although in some cases the job losses has been counterbalanced by the increasing demand for low-skilled occupations (Iammarino and others, 2019). Such processes, that has been also pointed out at global level as drivers for a “new geography of jobs” (Moretti, 2014), take the shape of a “great inversion” in the European context and especially in countries like Italy, France or Germany (Iammarino and others, 2019; Gallo and Pagliacci, 2020). Indeed, these dynamics of spatial marginalisation and peripheralization in these places have occurred in Italy since the 1950s, but it is through the new great wave of urbanisation in late 1970s that the “great inversion” actually starts, by then reaching its climax after the 2008 economic crisis (Iammarino and others, 2019; Gallo and Pagliacci, 2020). This primarily results in the displacement of productive activities and population in large cities, while at the same time other unpopular structures are relocated in peripheral areas, generally without generating any benefits for the remaining population (Barca and others, 2014; Bertolini and Pagliacci, 2017). In this sense, the social production of space in Italy takes the shape of an unfair or asymmetrical exchange, in which population and industries are moving to the centres and new peripheral areas are getting extractive and politically controversial structures in return.

This inversion can be identified within the theoretical framework proposed in the first chapter as a clear example of “rescaling process”, which has fostered a new social production of space through the relocation of capitalistic structures of accumulation in large cities, where, due to the greater potential for agglomeration, density and transport costs containment (Rodríguez-Pose, 2018), it is possible to grant more productivity and make better use of the global networks of contemporary capital. This rescaling process has thus resulted in a new spatial configuration, that is only partially overlapping North/South divide. For this reason, this study proposes to complement these imbalances by taking

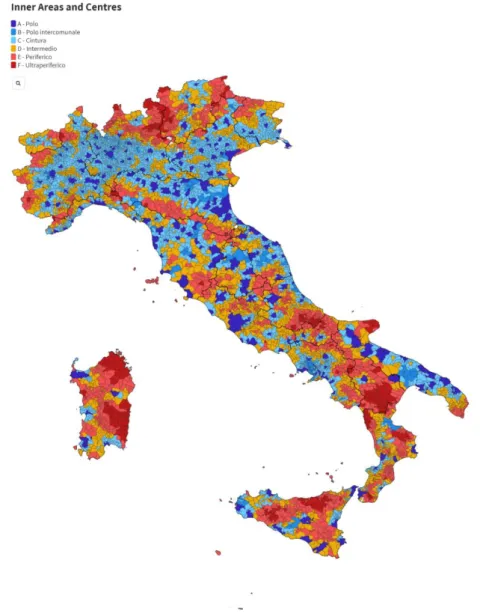

26 into account the division among different categories of Centres and Inner Areas as a proxy for scaling different localities among Italy. According to this categorisation, it is thus possible to distinguish six different types of municipalities, classified as pole, intermunicipal pole, belt, intermediate, peripheral and ultraperipheral according to their temporal distance to centres providing fundamental services (Barca and others, 2014). Inner Areas are thus defined as those territories that are distant more than 20 minutes from the closer pole and in their turn are divided into three sub-categories according to the extent of this distance: from 20 to 40 minutes they are labelled as intermediate municipalities, from 40 to 75 as peripheral and more than 75 as ultraperipheral (Barca and others, 2014; DPS, 2014).

Figure 2. Inner Areas and Centres classification according to Barca and others (2014) – Map created with Flourish

27

Immigration patterns towards Italian inner and peripheral

areas

Since the first consistent immigration flows during 1980s and 1990s, Italy has often been labelled as a “new immigration country” to distinguish it from Central and Northern European countries with a longer history of immigration, especially from former colonies (Andall, 1990; Finotelli and Sciortino, 2009; Ambrosini, 2013). However, the durability of the definition also links with the delayed self-acknowledgement of Italy itself as an immigration country, that have fostered the lack of regulation and visibility of this phenomenon until the last decades (Ambrosini, 2013; Fellini, 2018). For this reason, a more precise framework to understand the characteristics of immigration in Italy can be the concept of “Southern European model of immigration”, that was initially theorised by King (2000) with reference to Spain, Portugal, Italy and Greece. According to this model, these countries firstly share the size of immigration, that has constantly grown from the second half of the 1980s to today, and its timing, that makes this process simultaneous with the development of the Schengen area and the strenghtening of external borders (Finotelli and Sciortino, 2009; Fellini, 2018). Moreover, unlike Northern and Central European countries, Mediterranean States experience a multiplicity of migrant nationalities and types, to the point that is possible to speak of a

super-diverse heterogeneity of migrant origins since the very beginning

(King and DeBono, 2013). This latter element is partially the result of the high degree of spontaneity and unpredictability, that characterise the Southern European model and that it is fostered by the lack of a clear regulation and the increasing number of migration-inducing events in the surrounding area (Peixoto and others, 2012; King and DeBono, 2013). The spontaneity of immigration process in Southern European countries also reflects peculiar dynamics of their labour markets, which extensively rely on a large underground economy offering many opportunities of employment even for undocumented immigrants (Triandafyllidou and Ambrosini, 2011; Ambrosini, 2018; Fellini, 2018). The continuous labour demand in the irregular economy has run parallel to the gradual

28 incorporation of immigrant workers in the regular market and the settlement of families with migration background through reunification, supported by regularisation measures often adopted by these countries (Finotelli and Arango, 2011; Ambrosini, 2018; Fellini, 2018). However, despite the increasing incorporation of immigrant population, mechanisms of segregation still occur in Southern European labour markets at least along two axes. Firstly, some scholars argue the existence of an “ethnic penalty” pushing foreign people in low-skilled and manual works regardless of their actual qualification (Fullin and Reyneri, 2010; Avola, 2014; Barberis and Boccagni, 2014; Bonifazi and Marini, 2014). Secondly, the Southern European model of immigration is often marked by gender and ethnic specificity and asymmetry, which force different groups in gender-specific labour niches (Fullin and Reyneri, 2010; Peixoto and others, 2012; King and DeBono, 2013). While some scholars raise doubts about the extension of this model to all Mediterranean States and its lack of consideration for local peculiarities within these countries (Baldwin-Edwards, 2012; Ambrosini, 2013), others focus on how this model evolved in the wave of 2008 economic crisis and of asylum-seekers and refugees’ mass arrival after 2011 (Domínguez-Mujica and Pérez-García, 2017; Fellini, 2018). In particular, according to Fellini (2018), economic crisis has not weakened the features of this model in Italy, but instead it has emphasised some of its characteristics related to the insertion in labour market of immigrants, which has been made more segregated and precarious.

As regards the inner and peripheral areas, some features of the Mediterranean model contribute to explain peculiar patterns of immigration towards these localities in Italy. According to Ambrosini (2011), the economic embodiment of immigrants in Italy follows a spatial pattern, which is articulated in four main territorial models: the local production system of North-Eastern Italy, the metropolitan economies in large cities, the seasonal work in touristic localities and the irregular or precarious work in rural areas of Southern Italy. As a result of this

29 situation, many people with migration background, and especially those with precarious statuses, has settled in rural areas and in small- and medium-size cities since the first migration flows towards Italy (Ambrosini, 2011; Corrado, 2011). However, the worsening of the condition of migrant population after the economic crisis and the increasing criminalisation of immigration have further reduced work opportunity outside low-skilled employment and labour niches and pushed many people with migration background towards peripheral areas (Bonifazi and Marini, 2014; McAreavey, 2017; Fellini, 2018). For this reason, although the rate of residents with migration background remain lower than in large cities, the presence of immigrants in peripheral localities has sharply increased in the last decade.

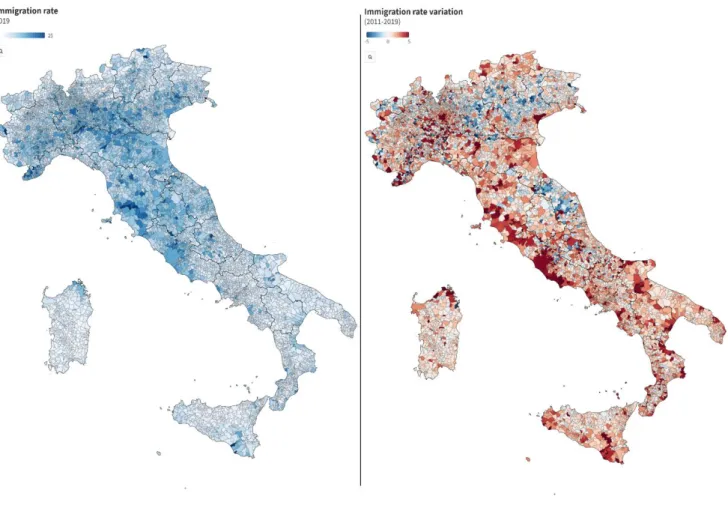

Figure 3. Immigration rate and immigration rate variation (2011-2019) by municipalities – Map created with Flourish based on ISTAT data

Alongside work immigration, and at the same time deeply intertwined with it, Italy has also experienced a large inflows of asylum seekers, at least since the so-called “North-Africa Emergency” in 2011. By adopting a

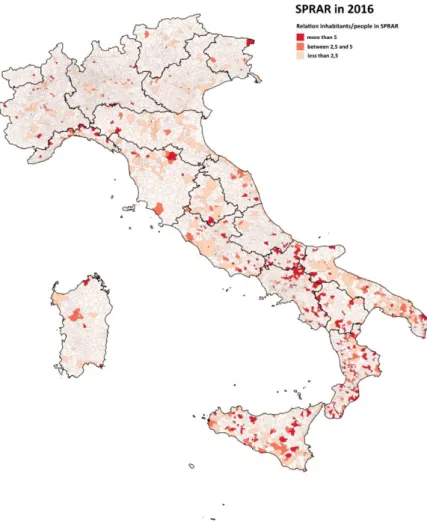

30 similar attitude as for other types of immigration, forced migration was not fully addressed by public policies until that moment (Campomori and Ambrosini, 2020). The first comprehensive configuration of the Italian reception system was created with law no.142/2015, which stated the centrality of SPRAR (Sistema di Protezione per Richiedenti Asilo e Rifugiati - System of Protection for Asylum Seekers and Refugees) and of the diffused reception model and stated the maximum capacity for reception in municipality at 2,5 asylum seekers and refugees of every 1000 inhabitants. However, due to the voluntary base of the membership in SPRAR, very few municipalities join the program and the majority of the migrant reception has turned to CAS (Centri di Accoglienza Straordinaria – Centres of Extraordinary Reception), extraordinary centres under the authority of the prefect, who assign the day-to-day administration to private entities (Calcagno and Bologna, 2019; Semprebon and Pelacani, 2020). From this moment, reception policies in Italy clearly shifted towards a “permanent emergency” frame, which has led to give more and more priority to extraordinary reception and to weaken the ordinary one, as also exemplified by the Decree Law no.132/2018, that converted SPRAR in SIPROIMI (Sistema di Protezione per titolari di protezione internazionale e minori stranieri non accompagnati – System of protection for holder of international protection and unaccompanied foreign minors) by excluding asylum seekers from the access to this new system (Campomori and Ambrosini, 2020; Semprebon and Pelacani, 2020).

In this context, the reception of asylum seekers and refugees in Italy has experienced an increasing process of peripheralization, which has been fostered by many reasons. Firstly, many peripheral localities, especially in Southern inner areas and in the mountain zones, join SPRAR to grab the opportunity of forced migration for contrasting depopulation, but also to obtain funding and incentives related to the program (Marcher and others, 2017; Galera and others, 2018; Campomori and Ambrosini, 2020). At the same time, other peripheral localities near the national borders, mostly in the South or the Alps, are compelled to deal with consistent migration

31 flows, due to their positioning close to places of arrival or to important crossing-point for migrants in transit. In these cases, they become a sort of “internal hotspots”, forced by restrictive border policies to accept extra-ordinary reception and its mechanisms (Semprebon and Pelacani, 2020). Such patterns seem to be confirmed also by official statistics, since in 2016 39% of the total CAS and almost the half of asylum seekers and refugees received in SPRAR were located in mountain areas (Di Gioia, 2017). Indeed, following similar dynamics as for other controversial issues, peripheral municipalities are often pressed to accept the presence of reception centres, but, unlike in the case of landfills or extractive activities, they can also manage to obtain benefits by welcoming asylum seekers and refugees (Galera and others, 2018). The model of diffused reception thus turns into a model based on geographic dispersion, which tend to avoid concentrating reception centres in large urban areas, by fostering their collocation in rural and peripheral ones (Robinson and others, 2003; Corrado, 2017; Altin, 2019). However, power asymmetries between these localities and more influencing ones, as well as the high politicisation of migratory issues, lead to the creation of serious imbalances in the reception, so that peripheral municipalities are more likely to receive much more asylum seekers and refugees than the maximum quota provided by law (Di Gioia, 2017).

32

Figure 4. Municipalities with active SPRAR program in 2016 and quota of asylum seekers and refugees related to the population – Map created with Flourish based on

data from Atlante SPRAR 2016 (SPRAR, 2016)

By considering the national reception strategy within the theoretical framework of this work, it seems possible to conceive it as a feature of the social production of space, that is articulated through the asymmetrical negotiation between the State and the local level on different “asylum devices” (Calcagno and Bologna, 2019). This mechanism contributes to foster diversification of peripheral areas through the relocation of reception centres in these localities, but it also intertwines with the prismatic action of the border, which orients the rooting of migrants in specific places and often determines their insertion in peculiar sectors of the national labour market (Mezzadra and Neilson, 2013; Hall, 2017). The combination of the social production of reception spaces and the performative nature of border regimes thus seem to trigger in peripheral localities complex processes of diversification, which deal with an increasing presence of foreign

33 population with different backgrounds, but also with a proliferation of diverse legal statuses, motivation and labour experiences.

Diversification among peripheral localities in Italy: is

there super-diversity outside the city?

Based on the assumptions of the previous sections, in this part relevant data about variables of diversification in Italian localities are analysed and compared among different municipalities to try understanding to what extent diversity is increasing in inner localities in Italy and along which peculiar patterns. The first dimension to consider while studying these processes is the presence of immigrants’ communities, which are one of the main means of diversification. By looking at immigration rate in Italian municipalities, it is evident that the majority of people with migration background lives in large cities and it seems that only a small part of them inhabits inner municipalities. However, further considerations need to be taken into account to properly understand the general frame. Firstly, as mentioned above, a consistent amount of foreign population in peripheral localities is represented by asylum seekers and immigrants with irregular or precarious statuses, who are not considered in official statistics on residents (Corrado, 2011; Di Gioia, 2017). Moreover, by taking a closer look to the immigration growth rate in different Italian municipalities, it is possible to note that peripheral localities are experiencing a rapid increase in foreign population, that in the last decade is often higher than in large cities and other urban centres. Finally, specific regional dimensions should be highlighted, also in consideration that the Mediterranean model, or what it remains after the economic crisis, seems to be less prominent in the North (Avola, 2014). Indeed, while Northern regions show a larger distance between central places and peripheral ones regarding the presence of people with migration background, Central and Southern Italy seems to display a different picture, where immigration rate are more similar between poles and inner areas and its increase is much higher in the latter ones.

34

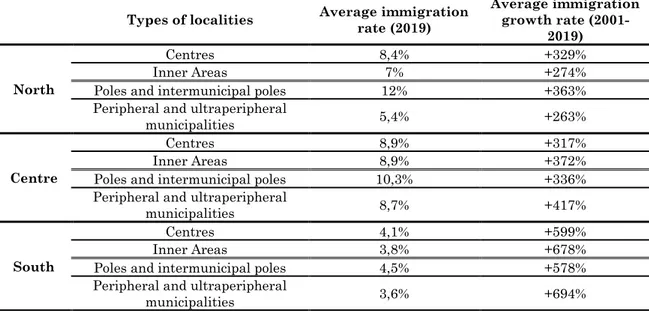

Types of localities Average immigration rate

(2019) Average immigration growth rate (2001-2019) Poles 9,9% +420% Intermunicipal poles 8,2% +434% Belt municipalities 7,5% +375% Intermediate municipalities 6,8% +419% Peripheral municipalities 4,9% +501% Ultraperipheral municipalities 3,4% +680% Centres 7,6% +379% Inner Areas 5,9% +467%

Table 3. Average immigration rate and immigration growth rate in Italy according to types of municipalities – Elaboration on Istat data

Types of localities Average immigration rate (2019) Average immigration growth rate (2001-2019)

North

Centres 8,4% +329%

Inner Areas 7% +274%

Poles and intermunicipal poles 12% +363%

Peripheral and ultraperipheral

municipalities 5,4% +263%

Centre

Centres 8,9% +317%

Inner Areas 8,9% +372%

Poles and intermunicipal poles 10,3% +336%

Peripheral and ultraperipheral

municipalities 8,7% +417%

South

Centres 4,1% +599%

Inner Areas 3,8% +678%

Poles and intermunicipal poles 4,5% +578%

Peripheral and ultraperipheral

municipalities 3,6% +694%

Table 4. Average immigration rate and immigration growth rate in Italian macro-regions according to types of municipalities – Elaboration on Istat data

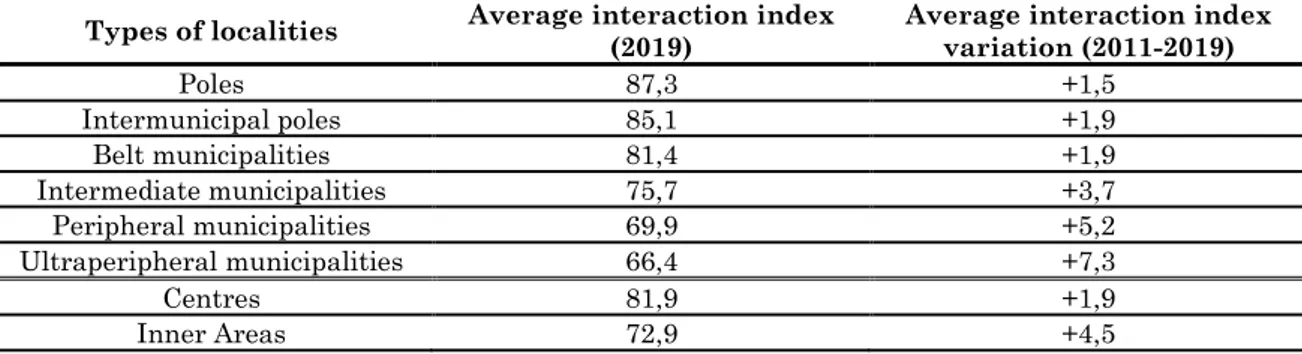

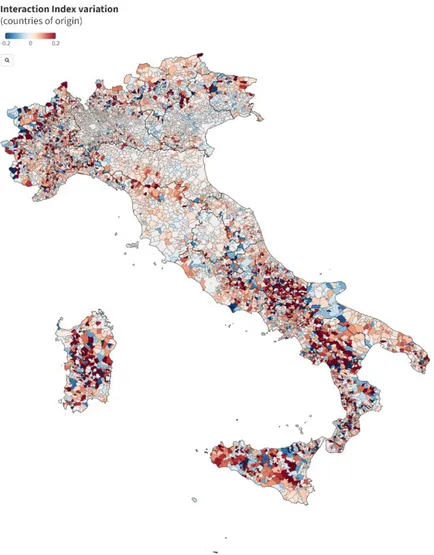

By going deeper in the analysis of other features of diversification, peculiar patterns of peripheral localities become more evident. First of all, diversification in terms of countries of origins of the population seems to occur faster in inner areas than in centres, although the lower number of people with migration background in absolute numbers makes the total number of countries of origins in large cities higher. In order to expose this element, this research uses as indicator the variation in the Interaction Index in single municipalities, which measures the probability from 0 to 100 that two people belonging to different groups meet in a specific context. By considering the population with migration background as divided in groups according to their nationalities, it is thus possible to see that, although the interaction index still remains higher in centres, its growth is higher in inner areas. Such situation could be read as a hint of a potential

35 saturation of nationally-defined networks for immigration and of a larger inflows of pioneer migrants, who are generally considered as an important driver of diversification (Wessendorf, 2018), but a similar hypothesis needs further studies to be confirmed. Moreover, despite the distinction is less marked than in the case of immigration rate, even for the interaction index a geographical imbalance emerges, whereas diversification along the national axis in inner areas seems to be more effective in the South.

Types of localities Average interaction index (2019) Average interaction index variation (2011-2019)

Poles 87,3 +1,5 Intermunicipal poles 85,1 +1,9 Belt municipalities 81,4 +1,9 Intermediate municipalities 75,7 +3,7 Peripheral municipalities 69,9 +5,2 Ultraperipheral municipalities 66,4 +7,3 Centres 81,9 +1,9 Inner Areas 72,9 +4,5

Table 5. Average interaction index and its variation in Italy according to types of municipalities – Elaboration on Istat data

Types of localities interaction index Average (2019) Average interaction index variation (2011-2019) North Centres 82,4 +1,4 Inner Areas 75,9 +3,7

Poles and intermunicipal poles 88,0 +0,9

Peripheral and ultraperipheral

municipalities 71,8 +4,6

Centre

Centres 82,1 +2,2

Inner Areas 75,7 +2,5

Poles and intermunicipal poles 86,9 +1,8

Peripheral and ultraperipheral

municipalities 73,4 +1,5

South

Centres 79,7 +3,5

Inner Areas 69,4 +6,0

Poles and intermunicipal poles 84,0 +2,5

Peripheral and ultraperipheral

municipalities 67,3 +6,7

Table 6. Average interaction index and its variation in Italian macro-regions according to types of municipalities – Elaboration on Istat data

36

Figure 5. Variation in Interaction Index between 2011 and 2019 in Italian municipalities - Elaboration on Istat data

Italian inner localities seem to show specific characteristics even regarding gender and age dimensions. Indeed, these places are experiencing a long-run ageing process, mainly caused by the emigration of the younger part of the population, which has also shaped the nature of diversification in at least two ways. Firstly, the presence of elderly people lacking familiar support has increased the demand for care labour, which, due to the persistence of a strong gendered and ethnical division of labour (Näre, 2013), has fostered in its turn the immigration of many foreign female workers. This initial situation has been partially modified with the increasing masculinisation of immigration flows towards Italy, that mostly occurred because of the larger presence of men in forced migrations. The masculinisation of immigration has affected the whole national territory, but it has been higher in peripheral localities to the point that they are arrived at similar gender balances as in large cities. By looking in different

37 types of localities at the masculinity index, that measures the number of men every 100 women, this dimension becomes evident in the substantial restriction of the gap between peripheral and ultraperipheral municipalities and poles.

Types of localities Index (2011) Masculinity Index (2019) Masculinity Average masculinity index variation (2011-2019)

Poles 81,1 92,1 +11,0 Intermunicipal poles 80,8 89,1 +8,3 Belt municipalities 86,0 90,5 +4,5 Intermediate municipalities 81,8 90,4 +8,6 Peripheral municipalities 74,2 86,4 +12,2 Ultraperipheral municipalities 65,1 88,4 +23,3 Centres 85,6 90,6 +5,0 Inner Areas 77,9 88,8 +11,0

Poles and intermunicipal poles 81,0 91,1 +10,0

Peripheral and ultraperipheral

municipalities 72,7 86,7 +14,0

Table 7. Masculinity index and its variation in Italy according to types of municipalities – Elaboration on Istat data

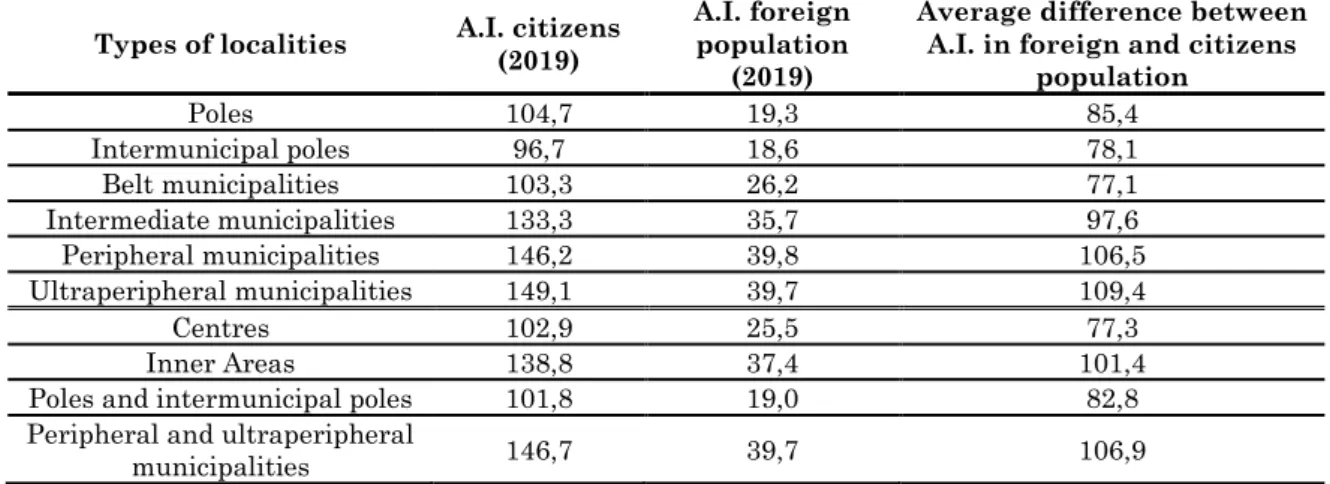

The second consequence of the intertwining of new international immigration and internal emigration of young people is a sort of “demographic polarisation”. Indeed, although foreign population in peripheral localities seems to be older than in central ones, people with citizenship become increasingly older and young population is more and more represented by people with migration background.

Types of localities A.I. citizens (2019)

A.I. foreign population

(2019)

Average difference between A.I. in foreign and citizens

population Poles 104,7 19,3 85,4 Intermunicipal poles 96,7 18,6 78,1 Belt municipalities 103,3 26,2 77,1 Intermediate municipalities 133,3 35,7 97,6 Peripheral municipalities 146,2 39,8 106,5 Ultraperipheral municipalities 149,1 39,7 109,4 Centres 102,9 25,5 77,3 Inner Areas 138,8 37,4 101,4

Poles and intermunicipal poles 101,8 19,0 82,8

Peripheral and ultraperipheral

municipalities 146,7 39,7 106,9

Table 7. Ageing Index (number of over 65 every 100 under 25 individuals) of foreign and citizens population in Italy according to types of municipalities – Elaboration on Istat

data

Through the above comparison and the considerations of the previous section regarding the diversification of legal statuses and labour experiences, it is thus possible to conclude that, although we cannot yet

38 properly speak of super-diverse contexts about most of the Italian peripheral localities, processes of diversification are occurring in these places with specific patterns, that differ from those generally observed in large cities. Moreover, these peculiarities also overlap with traditional territorial imbalances, such as the North/South divide, and with the evolution of economic and immigration models, which trigger new rescaling processes and changes in settlement paths of people with migration background. Diversification in Italian peripheral localities can thus be distinguished by that of central ones since it seems to proceed faster and alongside an increasing polarisation of the population from demographic and class points of view. In this context, such preliminary results also suggest a potential strong diversification in lifestyles, attitudes and practices, since not only very different persons are getting in touch in often small environments, but also among apparently similar groups the dynamics previously exposed can foster the emergence of diverse personal paths. For instance, due to the overpopulation of reception centres, it is possible that two asylum seekers sharing the same statuses and labour positions could live in different structures with very different outcomes in terms of lifestyles. However, such issue cannot directly and properly be addressed through the instruments proposed in this work, so that it is remanded to further studies on the topic to test the hypothesis.