POLITECNICO DI MILANO

School of Industrial and Information EngineeringMaster of Science in

Management Engineering

A MODEL FOR THE ASSESSMENT OF THE

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF

B2C E-COMMERCE IN ITALY

Graduation thesis of:Silvia Beggio ID 875195

Supervisor:

Prof. Riccardo Mangiaracina, Politecnico di Milano

Co-supervisors:

Prof. Marco Cantamessa, Politecnico di Torino Dott.ssa Chiara Siragusa

Dott.ssa Arianna Seghezzi

December 2018 Academic year 2017-2018

3

Abstract

Today's society is facing an important period of transition. To make informed choices, data and tools to interpret the world are necessary. This thesis is placed within this context: the understanding of a fast-growing phenomenon like e-com-merce and its effect on the environment. This objective is pursued throughout the development of a quantitative activity-based model for the assessment of the car-bon footprint of online distribution in the Italian context, in comparison to the traditional distribution. The model, created through Microsoft Excel, focuses on four specific industries: apparel, informatics and electronics, publishing and gro-cery. The main originality of the model is in the use country-specific data and in its cross-industry approach. According to the results of the model, the overall im-pact of B2C e-commerce in Italy is about 375.000 tons of carbon dioxide equiva-lents per year. The environmental impact per item relative to the online channel is on average lower than the one relative to the traditional channel. The highest ad-vantage concerns informatics and electronics. In the grocery industry, the carbon footprint per item is comparable for online and traditional channel. At last, the growth of e-commerce in Italy seems to have a positive impact: a 1% increase in the penetration rate of e-commerce drives to a 0,2% reduction in the carbon foot-print attributable to commercial activities.

5

Abstract – Italiano

La società contemporanea sta affrontando un importante periodo di transizione. Dati e strumenti per interpretare il mondo circostante si rendono sempre più ne-cessari per realizzare scelte consapevoli. Il contesto in cui questa tesi si colloca rientra in questo ambito: la comprensione di un fenomeno che sta crescendo rapi-damente e che ha un effetto sull’ambiente, come l’e-commerce. Questo obiettivo viene raggiunto tramite lo sviluppo di un modello quantitativo “activity-based” per la valutazione dell’impatto ambientale, in termini di impronta carbonica, per il commercio online nel contesto italiano, con un approccio comparativo verso il canale distributivo tradizionale. Il modello, realizzato in Microsoft Excel, si foca-lizza su quattro settori specifici: abbigliamento, informatica ed elettronica, editoria e settore alimentare. La più grande originalità del modello sta nel suo essere rife-rito ad un paese specifico e nel suo approccio multi-settoriale. Secondo i risultati ottenuti, l’impatto totale del B2C e-commerce in Italia è di circa 375.000 tonnellate di diossido di carbonio equivalente all’anno. L’impatto ambientale per singolo prodotto relativo al commercio online è in media più basso di quello relativo al canale tradizionale. Il vantaggio più grosso è quello riscontrato nel settore elettro-nica e informatica. Nell’alimentare invece, l’impronta carboelettro-nica è paragonabile per i due tipi di canali. Infine, la crescita dell’e-commerce in Italia sembra avere un riflesso ambientale positivo: un eventuale aumento dell’1% nella penetrazione dell’e-commerce risulterebbe in una riduzione dello 0,2% dell’impronta carbonica causata dalle attività commerciali.

7

Executive summary

Purpose of the study

Globally, e-commerce is an extremely rapid pace growing phenomenon. Cur-rently, the e-commerce market is worth about 2.500 billion euro worldwide, and 27,4 billion euro in Italy, after a 16% increase in 2017. The implications of e-com-merce are not only related to the relationship between the customer and the mer-chant, but they also include effects on the economy, the society as a whole and the environment. Even though many studies have been dedicated to the understand-ing of the effects of the online commerce on the employment, on the quality of life and on consequences in urban contexts, there is still unclarity about the relation-ship between environment and e-commerce. The deep and accurate investigation of this topic is necessary both to increase the awareness of customers and to push companies towards the inclusion of sustainability considerations in their distribu-tion network choices. The purpose of this thesis work is consequently to elucidate the role of e-commerce in Italy with respect to environmental sustainability. This objective is pursued throughout the creation of a model for the assessment of the environmental impact of the online distribution channel in the Italian context, in comparison to the traditional “brick and mortar” distribution.

Brief notes on extant knowledge

Researchers seem to agree about the advantages in terms of environmental impact related to a higher penetration of e-commerce (Carrillo, Vakharia, & Wang, 2014; Weber, Koomey, & Matthews, 2010; Wiese, Toporowski, & Zielke, 2012; Zanni & Bristow, 2010), even though the result depends strictly on many variables related to the behaviour of customers (Bertram & Chi, 2018), to the preferred means of transportation (J. B. Edwards, McKinnon, & Cullinane, 2010) and to the packaging features (Van Loon et al., 2015). Many studies focused on soft aspects such as the relationship between e-commerce sustainability and the improvements in the dis-tribution network efficiency (Sivaraman, Pacca, Mueller, & Lin, 2008). However, some aspects related to the sustainability of B2C e-commerce have not been inves-tigated yet. First of all, some growing industries, such as the electronics and infor-matics and the e-grocery industry, have not been evaluated yet from an

environ-8 mental point of view (Mangiaracina, Marchet, Perotti, & Tumino, 2015). In addi-tion, no cross-industry model for the evaluation of the impact of e-commerce in a country have been created and there is no evidence of how variables related to the characteristics of the area affect the environment. This thesis work is an attempt to address such research gaps.

Objectives and method

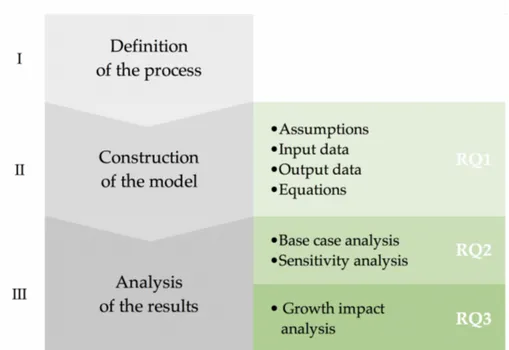

The objective of the thesis is formalized in the three research questions reported in the following table (Table A):

Table A: Research questions

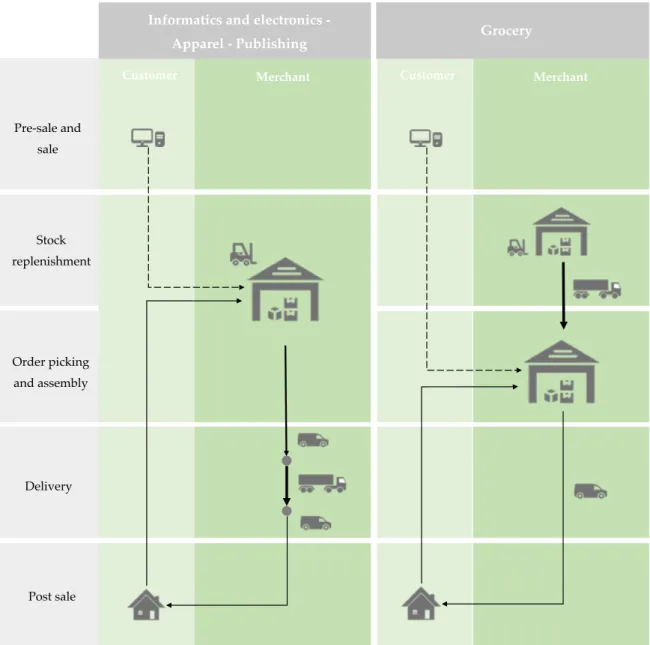

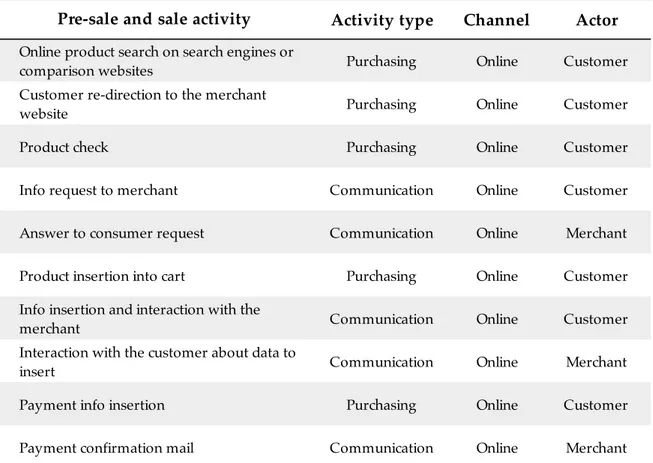

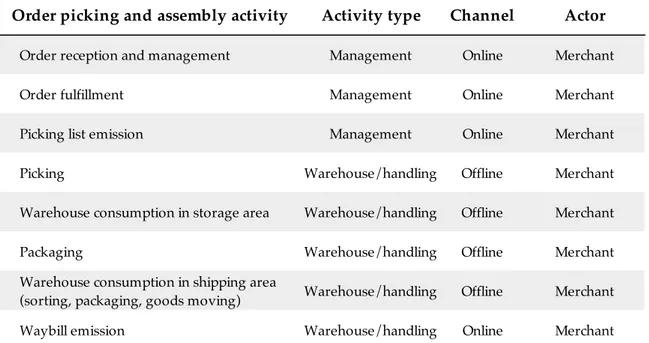

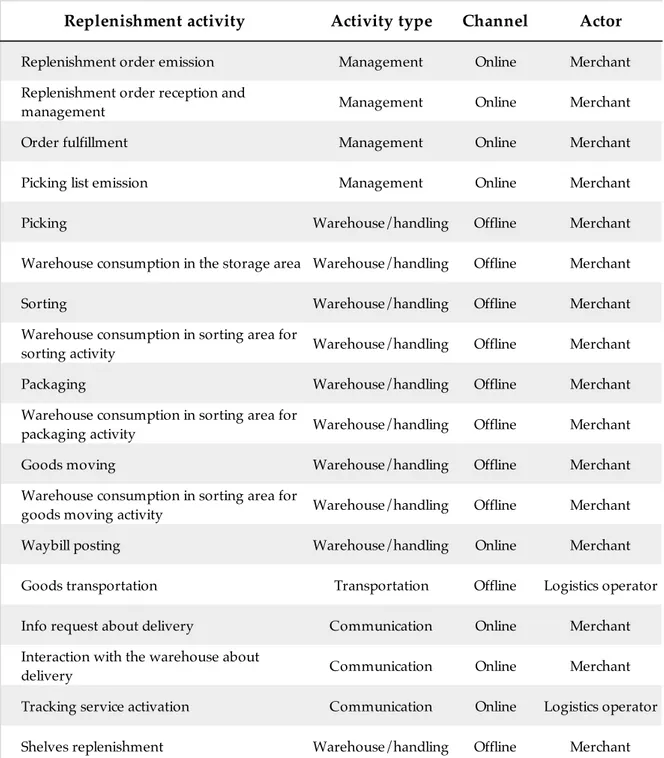

The steps followed to answer to the research questions implied a preliminary def-inition of the process of reference for both e-commerce and traditional channel. The process is composed of four macro-phases: pre-sale and sale; order picking and assembly; delivery; post-sale. Each phase was divided into activities.

The second step regarded the construction of an analytical activity-based model, which computes the environmental impact of e-commerce in terms of emission of carbon dioxide equivalents, or carbon footprint, the chosen unit for the analysis. The model focuses on four main industries, namely:

• Informatics and electronics; • Apparel;

• Publishing;

• Food and grocery.

RQ1 How can the environmental impact of B2C e-commerce in a country be estimated?

RQ2 What is the environmental impact of B2C e-commerce in Italy?

How does the impact of e-commerce compare to the traditional channel?

RQ3 How does the impact of commercial activities vary based on the penetration of e-commerce on the market?

9

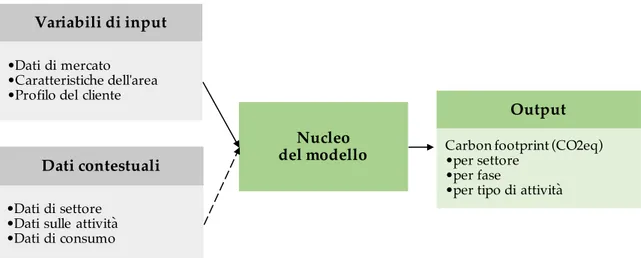

Figure A: Model structure

For each industry, the model reproduces a distribution network, which represents the average situation for both e-commerce and traditional channel. The computa-tions were made by means of Microsoft Excel. Figure A reports the structure of the model.

The third step was the analysis of the results. Feeding the model with input data aimed at describing the Italian context allowed to determine the environmental impact of e-commerce, caused by each of the four industries separately and over-all, on the selected country over the timespan of one year. Also, it was possible to recognise how the impact of a single item or order shipped through the online channel compares to the one of a purchase in the traditional channel. Later, it was possible to use the outcomes relative to the Italian context as a base case to study how the variables related to the features of the area of reference affect the results. At last, the consequences on environment of the growth of e-commerce, in terms of penetration rate of the online channel in the traditional channel, was deter-mined and discussed.

Main findings

According to the results of the model, the overall impact of B2C e-commerce in Italy is about 375.000 tCO2e per year (Graph A). The contribution of the four in-dustries under analysis to the overall impact is not proportional to their market share. The “informatics and electronics” industry holds the highest market share, while its carbon footprint is the lowest (16%). Contrarily, “publishing” and “food and grocery” industries revealed the highest environmental impact (22% and 21%

Context data

Model core Input variables

•Market data •Features of the area •Customer profile

Output data Carbon footprint (CO2eq) •by industry

•by phase •by activity type •Industry data

•Activity data •Consumption data

10 respectively), despite the low market share (7% each). This can be explained con-sidering the low value of the goods, which disguises the large flow of items. In comparison to the traditional channel, the carbon footprint per single item shipped through the online commerce seems to be lower, on average.

Graph A: Yearly carbon footprint of B2C e-commerce in Italy

Graph B: Carbon footprint per item by industry and by channel (e-commerce on the left and traditional channel on the right)

0 50.000 100.000 150.000 200.000 250.000 300.000 350.000 400.000

Overall

By industry

tCO2e / year

Apparel Informatics and Electronics Publishing

Food and Grocery Others Overall

0,00 0,50 1,00 1,50 2,00 2,50 3,00 3,50 4,00

Apparel Informatics and Electronics

Publishing Food and Grocery

Others Overall

kgCO2e / item

11 Looking at the result for the single industries (Graph B), the advantage is evident for apparel (-14%), informatics and electronics (-30%) and publishing (-29%). For what concerns grocery, the carbon footprint per item is comparable for online and traditional channel.

In addition, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to understand how the result changes due to variations in the input variables. In particular, the effect of changes in the characteristics of the geographical area and to the customers’ behaviour were tested. What emerged is that, despite the variations in the model output, e-commerce remains more convenient with respect to the traditional e-commerce from an environmental point of view.

In conclusion, according to the model, the growth of e-commerce in Italy has a positive impact on environment. Specifically, a unitary percentage increase in the penetration rate of e-commerce drives a 0,2% reduction in the carbon footprint attributable to commercial activities. It has to be noted that this result is valid only for values of the penetration rate which are close to the current value of 5% (Osservatori e-commerce, 2018a).

Research implications and limitations of the work

This thesis work represents a step forward in the attempt to compute the environ-mental impacts of the online distribution of some product categories. The results are in line with the ones obtained in previous research works, for what concerns apparel and informatics and electronics. For the other industries, no significant previous results are available for a comparison.

Nevertheless, the main originality of this thesis work is the attempt to give an overall estimation of the environmental impact of B2C e-commerce on Italy. As emerged from the literature review, no previous work used country-specific data to compute the carbon footprint, considering variables related to the features of the area and allowing at the same time for cross-industry comparison of e-com-merce distribution.

However, potential limitations must be highlighted. First of all, the work should be completed by modelling specific processes of other industries, such as the fur-niture and home living industry, that represents a significant portion of the e-com-merce market. In addition, to better reflect the complexity of e-come-com-merce, other

12 variants in the distribution network design should be modelled, such as delivery in points of sales or parcel lockers delivery. Moreover, the model should include changes in the distribution network due to the future increase in online flows. This would allow for a better estimation of the impact of e-commerce. At last, it is nec-essary to clarify that assumptions and simplifications make the measurement of the environmental impact less precise. Still, they do not undermine the objective of the thesis, which is to obtain a general rough estimation of the carbon footprint of e-commerce in comparison to the traditional channel, and to collect insights about related variables.

13

Executive summary - Italiano

Obiettivo dello studio

Negli ultimi anni, il fenomeno dell’e-commerce sta sperimentando una rapida cre-scita. Al momento, il suo valore complessivo si attesta circa sui 2.500 milioni di euro in tutto il mondo e sui 27,4 milioni in Italia, a seguito di una crescita impres-sionante del 16% nel solo 2017. Lo studio della fenomenologia dell’e-commerce non concerne solamente la relazione tra consumatore e produttore, che pure rap-presenta un elemento primario: al contrario, le sue conseguenze si allargano a eco-nomia, società in senso lato e ambiente. Sebbene molti ricercatori si siano dedicati a studiare l’impatto dell’e-commerce sul livello di occupazione, sulla qualità della vita e sui contesti urbani, c’è ancora incertezza sulle implicazioni dell’e-commerce dal punto di vista meramente ambientale. Un accurato approfondimento dell’ar-gomento si rende quindi necessario sia per aumentare la consapevolezza dei con-sumatori, sia per promuovere politiche sostenibili nelle scelte strategiche delle aziende riguardo al canale distributivo. L’obiettivo di questa tesi è quindi quello di contestualizzare il ruolo dell’e-commerce in Italia rispetto alla sostenibilità am-bientale. Per raggiungere l’obiettivo prefisso, è stato prodotto un modello per la valutazione dell’impatto ambientale dell’e-commerce nel contesto italiano, inclu-sivo di paragone con la distribuzione tradizionale.

Cenni sulla letteratura esistente

Molti ricercatori sembrano essere d’accordo sui vantaggi ambientali legati alla cre-scita dell’e-commerce (Carrillo et al., 2014; Weber et al., 2010; Wiese et al., 2012; Zanni & Bristow, 2010), anche se il risultato è profondamente influenzato da molte variabili legate al comportamento del consumatore (Bertram & Chi, 2018), ai mezzi di trasporto utilizzati (J. B. Edwards et al., 2010) e alle caratteristiche del packaging (Van Loon et al., 2015). Ulteriori studi si sono concentrati invece sulla relazione tra la sostenibilità ambientale dell’e-commerce e i miglioramenti nell’ef-ficienza dei canali di distribuzione (Sivaraman et al., 2008). Tuttavia, permangono aspetti della sostenibilità ambientale in ambito e-commerce B2C che non sono stati ancora strutturalmente esaminati. Innanzitutto, alcuni settori in crescita, come quello di “informatica ed elettronica” e dell’”e-grocery”, non sono stati ancora og-getto di analisi in questo contesto (Mangiaracina et al., 2015). Inoltre, al momento,

14 non è presente alcun modello per la valutazione dell’impatto ambientale dell’e-commerce, relativo a una sola nazione campione, che permetta di effettuare un paragone tra settori e che metta in evidenza le variabili legate alle caratteristiche dell’area di riferimento. Questa tesi rappresenta un esperimento in tal senso. Obiettivi e metodi

Gli obiettivi della tesi sono riassumibili in tre domande di ricerca, riportate sotto (Tabella A):

Tabella A: Domande di ricerca

I passaggi necessari individuati per rispondere efficacemente alle domande di ri-cerca non possono che partire da una definizione preliminare dei processi di rife-rimento, sia per quanto riguarda l’e-commerce che per quanto concerne il canale tradizionale. Il processo si compone di quattro fasi: pre-vendita e vendita; picking e assemblaggio dell’ordine; consegna; post-vendita. Ogni fase viene poi ulterior-mente suddivisa in singole attività.

Il secondo passaggio riguarda la costruzione del modello analitico “activity-ba-sed”. Il modello serve a calcolare l’impatto ambientale, misurato in emissioni di biossido di carbonio equivalente, anche denominate “impronta carbonica”, l’unità selezionata per l’analisi. Nello specifico, quattro settori sono stati considerati:

• Informatica ed elettronica; • Abbigliamento;

• Editoria; • Alimentare.

RQ1 Come si può stimare l'impatto ambientale dell'e-commerce B2C in una nazione?

RQ2 Qual è l'impatto ambientale dell'e-commerce B2C in Italia? Com'è l'impatto ambientale dell'e-commerce rispetto a quello del commercio tradizionale?

15

Figura A: La struttura del modello

Per ogni settore, il modello riproduce un canale di distribuzione rappresentativo della situazione media per l’e-commerce e per il canale tradizionale. I calcoli sono stati effettuati utilizzando Microsoft Excel. Figura A riporta la struttura del mo-dello.

Il terzo passaggio è costituito dall’analisi dei risultati. Inserendo nel modello i dati di input relativi al contesto italiano, è stato possibile determinare l’impatto am-bientale dell’e-commerce, in totale e rispetto ai singoli settori, nell’intervallo di un anno. Inoltre, gli impatti di un singolo prodotto spedito tramite il canale online oppure venduto in un negozio tradizionale sono stati confrontati. In seguito, il risultato relativo al contesto italiano è stato usato come caso base per capire come le caratteristiche peculiari relative all’area di riferimento influenzano i risultati. Infine, sono state approfondite e discusse le conseguenze sull’ambiente di una ipo-tetica crescita dell’e-commerce, in termini di penetrazione nel mercato, rispetto al canale tradizionale.

Risultati principali

Secondo i risultati derivati dal modello, l’impatto totale dell’e-commerce B2C in Italia è circa 375.000 tCO2e all’anno (Grafico A). La divisione dell’impatto tra i quattro settori considerati non è tuttavia proporzionale alla loro incidenza sul mercato. Il settore di “informatica ed elettronica” ha la maggiore incidenza sul mercato, ma allo stesso tempo la sua impronta carbonica è la più bassa (16% del totale). Al contrario, “editoria” e l’”alimentare” causano il più alto impatto am-bientale (rispettivamente il 22% e il 21% del totale), nonostante la bassa incidenza

Dati contestuali Nucleo del modello Variabili di input •Dati di mercato •Caratteristiche dell'area •Profilo del cliente

Output Carbon footprint (CO2eq) •per settore

•per fase

•per tipo di attività •Dati di settore

•Dati sulle attività •Dati di consumo

16 sul mercato (7% per entrambi). La spiegazione è facilmente riscontrabile nel basso valore dei prodotti, che inverte l’effetto dell’alto numero di prodotti venduti per anno.

Grafico A: L’impronta carbonica annuale dell’e-commerce B2C in Italia

Grafico B: L’impronta carbonica per prodotto nel caso dell’e-commerce (a sinistra) e del canale tradizionale (a destra)

0 50.000 100.000 150.000 200.000 250.000 300.000 350.000 400.000

Totale

Per settore

tCO2e / anno

Abbigliamento Informatica ed elettronica Editoria Alimentare Altro Totale

0 0,5 1 1,5 2 2,5 3 3,5 4 Abbigliamento Informatica ed elettronica

Editoria Alimentare Altro Totale

kgCO2e / prodotto

17 Rispetto al canale tradizionale, l’impronta carbonica di un singolo prodotto ven-duto tramite il canale online risulta essere in media inferiore. Per quanto riguarda i singoli settori, (Grafico B), il vantaggio è evidente per “abbigliamento” (-14%), “informatica ed elettronica” (-30%) ed “editoria” (-29%). Invece, nel settore ali-mentare, l’impronta carbonica per prodotto è simile per e-commerce e canale tra-dizionale.

In seguito, è stata svolta una analisi di sensitività per indagare come i risultati cambiano rispetto alle variabili di input. In particolare, è stato testato l’effetto di cambiamenti nelle caratteristiche dell’area geografica e nel comportamento dei consumatori. Quello che è emerso è che, nonostante le variazioni nell’output del modello, l’e-commerce rimane più conveniente del canale tradizionale da un punto di vista ambientale.

In conclusione, interpretando i risultati del modello, la crescita dell’e-commerce in Italia ha un impatto positivo sull’ambiente. Nello specifico, un incremento per-centuale unitario nel tasso di penetrazione dell’e-commerce comporta una ridu-zione del 0,2% nell’impronta carbonica delle attività commerciali nei settori con-siderati. E’ necessario notare che questo risultato è valido solamente per valori di penetrazione dell’e-commerce che sono vicini al valore attuale del 5% (Osservatori e-commerce, 2018a).

Implicazioni sulla ricerca e limiti del lavoro

Questa tesi rappresenta un passo avanti nel tentativo di calcolare l’impatto am-bientale dovuto all’e-commerce di alcuni settori. I risultati sono in linea con quelli ottenuti in studi precedenti per quanto riguarda l’abbigliamento e l’informatica ed elettronica. Per quanto riguarda gli altri settori, la scarsità di risultati precedenti rende impossibile effettuare un valido confronto.

In ogni caso, la parte più originale di questo lavoro è il tentativo di stimare l’im-patto ambientale dell’e-commerce B2C in Italia. Come è emerso dalla revisione della letteratura, nessuno studio precedente ha fatto uso di dati specifici relativi a una singola nazione per calcolare l’impronta carbonica totale, considerando varia-bili legate alle caratteristiche dell’area geografica e realizzando allo stesso tempo un paragone tra settori.

18 Tuttavia, alcuni potenziali limiti di questo approccio devono essere evidenziati. Innanzitutto, sarebbe utile completare il lavoro modellizzando i processi relativi ad altri settori, come per esempio quello dell’arredamento, che in questo momento rappresenta una porzione significativa del mercato e-commerce. Inoltre, per me-glio riflettere la complessità del fenomeno analizzato, dovrebbero essere model-lizzate altre varianti del canale distributivo, come per esempio la consegna nel ne-gozio tradizionale oppure la consegna in “parcel lockers”. Il modello potrebbe in-fine essere sviluppato per tenere in considerazione eventuali cambiamenti nel ca-nale di distribuzione dovuti ad aumenti nei flussi e-commerce. Questo consenti-rebbe una stima più affidabile dell’impatto della crescita del fenomeno. Conclu-dendo, è necessario chiarire che le assunzioni e semplificazioni fatte nello svilup-pare il modello rendono la misurazione dell’impatto ambientale non completa-mente precisa. Tuttavia, questo non impedisce il raggiungimento dell’obiettivo di questo lavoro, che è quello di ottenere una stima generale dell’impronta carbonica dell’e-commerce rispetto al canale tradizionale in Italia e di comprendere quali variabili influenzano il risultato, e in che misura.

19

Table of contents

Abstract ... 3

Abstract – Italiano ... 5

Executive summary ... 7

Executive summary - Italiano ... 13

Table of contents ... 19 List of figures ... 23 List of tables ... 25 List of graphs ... 29 List of annexes ... 31 Acknowledgements ... 33 1 Introduction ... 35

1.1 E-commerce and logistics ... 35

1.2 B2C e-commerce in Italy ... 39

1.3 E-commerce and sustainability ... 42

2 Literature review ... 45

2.1 Introduction to the literature review ... 45

2.1.1 Classification context ... 45

2.1.2 Review method ... 47

2.2 Review analysis ... 48

2.2.1 Main features of the selected scientific articles ... 49

2.2.2 Analysis of the research methods ... 52

2.2.3 Dimension 1: Areas of e-commerce affecting the environment ... 61

2.2.4 Dimension 2 and 3: Industry scope and geographic scope ... 66

2.3 Conclusion and direction of future research ... 72

20

2.3.2 Identification of research gaps ... 75

2.3.3 Final discussion and limitations of the literature review ... 78

3 Objectives, research methodology and research framework ... 81

3.1 Research goal ... 81

3.1.1 First research question ... 82

3.1.2 Second research question ... 84

3.1.3 Third research question ... 86

3.2 Methodology ... 87

3.2.1 Approach and modelling tools ... 87

3.2.2 Structure ... 91

3.2.3 Context and constraints ... 94

4 Development of the model ... 97

4.1 Definition of the process ... 97

4.1.1 E-commerce process ... 97

4.1.2 Traditional commerce process ... 107

4.2 Assumptions ... 112

4.2.1 E-commerce model assumptions ... 113

4.2.2 Traditional model assumptions ... 115

4.3 Description of the model ... 116

4.3.1 General structure ... 116 4.3.2 Input data ... 118 4.3.3 Output data ... 122 4.3.4 Context data ... 122 4.3.5 Model core ... 143 5 Results ... 157

21

5.1.1 Description of the model output ... 157

5.1.2 Industry comparison ... 164

5.2 Sensitivity analysis ... 170

5.2.1 Impact of the features of the area ... 170

5.2.2 Impact of the customer behaviour ... 176

5.3 Growth impact analysis ... 177

6 Discussion of the results ... 181

6.1 Summary of the results ... 181

6.1.1 First research question ... 181

6.1.2 Second research question ... 182

6.1.3 Third research question ... 183

6.2 Positioning in literature ... 183

6.3 Limitations and future developments ... 185

7 Conclusion ... 187

8 References ... 189

23

List of figures

Figure 1: Review method schema ... 47 Figure 2: Geographical distribution of the analysed scientific articles ... 51 Figure 3: Functioning of the model ... 88 Figure 4: Thesis structure ... 91 Figure 5: E-commerce process of the informatics, apparel and publishing industries (left) and of the grocery industry (right) ... 100 Figure 6: Delivery process representation ... 106 Figure 7: Traditional commerce process ... 109 Figure 8: Structure of the model ... 117 Figure 9: Picking warehouse configuration ... 131

25

List of tables

Table 1: Scientific articles classification ... 54 Table 2: Classification of the scientific articles according to the research method adopted ... 60 Table 3: Classification of the scientific articles according to the area causing the environmental impact ... 62 Table 4: Classification of the scientific articles by industry scope ... 67 Table 5: Classification of the scientific articles by geographic scope ... 69 Table 6: Classification of the scientific articles by geographic scope and by industry scope ... 71 Table 7: Research questions ... 82 Table 8: Classification of pre-sale and sale activities in the e-commerce process

... 102 Table 9: Classification of the order picking and assembly activities in the

e-commerce process ... 103 Table 10: Classification of the replenishment activities in the e-commerce process

... 104 Table 11: Classification of the delivery activities in the e-commerce process ... 105 Table 12: Classification of the post-sale activities in the e-commerce process .... 106 Table 13: Classification of pre-sale and sale activities in the traditional process 110 Table 14: Classification of replenishment activities in the traditional process ... 111 Table 15: Classification of delivery activities in the traditional process ... 111 Table 16: Classification of the post-sale activities in the traditional process ... 112 Table 17: E-commerce market data ... 119 Table 18: Urbanization level data ... 120 Table 19: Distribution of population between climatic zones ... 120 Table 20: Market size data ... 124

26 Table 21: Purchase profile data ... 124 Table 22: Customer profile data ... 125 Table 23: Packaging data ... 126 Table 24: Customer's online activities duration ... 127 Table 25: Merchant's online activities duration ... 128 Table 26: Duration of online activities in the point of sale ... 128 Table 27: Warehouse configuration data ... 129 Table 28: Warehouse operative data ... 130 Table 29: Picking hypotheses ... 130 Table 30: Grocery warehouses configuration ... 132 Table 31: Grocery warehouses operative data ... 132 Table 32: Hub configuration data and hub operative data ... 133 Table 33: Hub consolidation and sorting hypotheses ... 133 Table 34: Point of sale configuration data ... 134 Table 35: Point of sale operative data ... 134 Table 36: Pick-up route and delivery route hypotheses ... 136 Table 37: Line haul hypotheses ... 136 Table 38: Replenishment hypotheses ... 138 Table 39: Customer trip hypotheses ... 138 Table 40: Online activities data and warehouse and hub activities consumption data ... 138 Table 41: Industrial building consumption computation ... 140 Table 42: Industrial buildings consumption data (H=heating, C=Climatization, S=Sanitary water production, L=lighting) ... 141 Table 43: Points of sale consumption data (H=heating, C=Climatization, S=Sanitary water production, L=lighting) ... 141 Table 44: Conversion factors ... 142

27 Table 45: Industry-dependent multiplying factors of merchant's activities ... 144 Table 46: Industry-dependent multiplying factors of customer's activities ... 145 Table 47: Industry-dependent multiplying factors of point of sale's activities ... 145 Table 48: E-commerce penetration data ... 178

29

List of graphs

Graph 1: E-commerce growth trend (* forecast) ... 36 Graph 2: E-commerce purchases trend ... 40 Graph 3: Share of products and services in e-commerce purchases ... 40 Graph 4: Scientific articles' publication dates trend ... 51 Graph 5: Distribution of the scientific articles among research methods ... 53 Graph 6: Yearly carbon footprint due to e-commerce ... 158 Graph 7: Distribution of the carbon footprint caused by e-commerce betwen industries (left) and market subdivision among industries (right) ... 158 Graph 8: Carbon footprint per item by industry of the e-commerce process (left) and of the traditional process (right) ... 160 Graph 9: Carbon footprint per order/purchase by industry of the e-commerce process (left) and of the traditional process (right) ... 161 Graph 10: Carbon footprint per item by phase ... 162 Graph 11: Distribution of the carbon footprint per item by phase for e-commerce (left) and the traditional channel (right) ... 162 Graph 12: Carbon footprint per item by activity type ... 163 Graph 13: Distribution of the carbon footprint per item by activity type for

e-commerce (left) and the traditional channel (right) ... 164 Graph 14: Carbon footprint per item by phase and by industry in e-commerce 165 Graph 15: Distribution of the carbon footprint per item by phase for apparel (left) and grocery (right) ... 166 Graph 16: Carbon footprint per item by activity type and by industry in

e-commerce ... 167 Graph 17: Carbon footprint per item by phase and by industry in the traditional channel ... 168

30 Graph 18: Distribution of the carbon footprint per item between phases in the grocery industry ... 168 Graph 19: Carbon footprint per item by activity type and by industry in the traditional channel ... 169 Graph 20: Variations in the carbon footprint per item by urbanization level ... 171 Graph 21: Carbon footprint by phase and by urbanization level in the e-commerce channel ... 171 Graph 22: Variations in the carbon footprint per item by climatic zones ... 173 Graph 23: Carbon footprint by phase and by climatic zone in the e-commerce channel ... 173 Graph 24: Variations in the carbon footprint per item over electricity conversion coefficient values ... 175 Graph 25: Carbon footprint by phase and by different values of the electricity conversion coefficient in the e-commerce channel ... 175 Graph 26: Variations in the carbon footprint per item by customer profile ... 177 Graph 27: Carbon footprint by phase and by customer profile in the e-commerce channel ... 177 Graph 28: Variation in the yearly carbon footprint by e-commerce penetration rate

... 179 Graph 29: Variation in the yearly carbon footprint by e-commerce penetration rate by industry ... 180

31

List of annexes

Annex 1: Model input………199 Annex 2: Model output – E-commerce process……….200 Annex 3: Model output – Traditional process………...201 Annex 4: E-commerce process formulas……….202 Annex 5: Traditional process formulas………...205

33

Acknowledgements

Desidero ringraziare il mio relatore, il Professor Riccardo Mangiaracina, per avermi dato la possibilità di misurarmi con un argomento di grande rilevanza e per i suoi preziosi suggerimenti. Un grazie anche alla Dottoressa Chiara Siragusa e alla Dottoressa Arianna Seghezzi per aver contribuito alla buona riuscita di que-sto lavoro, e al Professor Marco Cantamessa del Politecnico di Torino, per la di-sponibilità mostratami nell’accettare di essere il mio correlatore.

Vorrei inoltre ringraziare l’Alta Scuola Politecnica, che mi ha offerto una grande opportunità di crescita, e tutte le persone con cui ho condiviso questa esperienza, che sono una continua fonte di ispirazione.

Un ringraziamento speciale va alla mia famiglia, per aver sostenuto ogni mia scelta permettendomi di intraprendere questo percorso, e a Niccolò per averlo reso più facile nell’ultimo anno.

Infine, un grazie a tutti gli amici che, tra Padova, Bologna, Milano e Zurigo, hanno reso questi anni speciali.

35

1 Introduction

Today's society is facing an important period of transition: the world around us and all its components, both human and environmental, are experiencing radical changes. In this context, an increasingly important role is taken by private choices, in terms of individual decisions and company strategies, that can cause a huge impact on the society and on the environment. To be able to make informed choices, however, data and tools allowing us to interpret the world are necessary. This thesis is placed within this context: the understanding of a phenomenon like e-commerce and the effects that this phenomenon can have on the world will be of primary importance for present and future societies.

In this introductory chapter, a brief overview about e-commerce is given. Firstly, the main concepts related to e-commerce are explained and the main events which led to the establishment of e-commerce practices are described (Section 1.1). Par-ticular relevance is given to the logistics perspective. Later, an overview about the Italian e-commerce market is given (Section 1.2). At last, the general implications of e-commerce on business, society and environment are explored, underlining the need to give more attention to the relationship between e-commerce and sus-tainability (Section 1.3).

1.1 E-commerce and logistics

Electronic commerce first appeared in the early 1970s (Kalakota & Andrew, 1997). At that time electronic money transfers used to take place mostly among financial institutions. Such technology, known as EFT (Electronic Funds Transfer), was em-ployed almost exclusively by large corporations and financial institutions. The fol-lowing innovation was the EDI (Electronic Data Interchange), which enabled the electronic transfer of routine documents and later also other types of transactions. The advent of the World Wide Web in the 1990s was an important turning point. Companies could finally exploit the Internet to reach the customers through a dig-ital channel, being present with both texts and images. At this time the term “elec-tronic commerce” or “e-commerce” was first introduced and its scope and appli-cations expanded rapidly. Dot-coms and internet start-ups were created. Nowa-days any company is present on the Web.

36

Graph 1: E-commerce growth trend (* forecast)

After year 2000, social networks were born, and electronic commerce was ex-panded into social commerce, exploiting such channels. Currently, the e-com-merce market is worth about 2.500 billion euro worldwide, after a 20% growth in the last year, and 600 billion euro in Europe (Osservatori e-commerce, 2018a). Un-doubtedly, it will continue to grow and evolve. Graph 1 reports the forecasted future growth trends (Statista, 2017).

It is not easy to define the phenomenon of e-commerce. Indeed, many perspectives can be adopted while describing it because of the number and of the variety of disciplines it includes, such as accounting, economics, engineering, computer sci-ence, consumer behaviours, marketing, management and logistics (Turban, Whiteside, King, & Outland, 2017).

One of the first definitions is the one by Kalakota & Andrew (1997), who referred to a range of different perspectives:

• A communications perspective, namely the exchange of information and the delivery of products and services though an electronic channel;

• A business process perspective, the use of ICT for the automation and standardization of business transactions and workflows;

• A service perspective, increasing the speed and quality of service delivery while cutting costs;

0 1.000 2.000 3.000 4.000 5.000 6.000 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018* 2019* 2020* 2021* b il li on $

37 • An online perspective, namely the buying and selling of products and

ser-vice online.

Later, the UK government defined e-commerce with the following words (Inland Revenue & HM Customs and Excise, 1999):

“E-commerce is the exchange of information across electronic networks, at any stage in the supply chain, whether within an organization, between businesses, between busi-nesses and customers, or between the public and private sector, whether paid or unpaid.”

An important author, Chaffey (2007), states that e-commerce includes much more than just electronically mediated financial transactions between organizations and customers. But rather he presents e-commerce as all electronically mediated trans-actions between an organization and any third party it deals with. The author also makes an important distinction between buy-side e-commerce, referring to trans-actions to procure resources needed by an organization from its suppliers, and sell-side e-commerce, namely transactions involved with selling products to the customers of the organization.

All these early definitions describe the scope of e-commerce as extremely broad, encompassing not only the buying and selling of products, but also the communi-cation of information and the pre-sale and post-sale activities across the supply chain. More recent definitions use a slightly different perspective in describing e-commerce. For example, Dan (2014) defines it as:

“E-commerce involves the business, technology, society, and skills of buying and selling of products and services with the aid of internet and computer or handheld devices which

involves the process of ordering products or services to the time of delivery to the con-sumer or customer.”

Again, another definition is (Turban et al., 2017):

“Electronic commerce refers to using the Internet and other networks (e.g., intranets) to purchase, sell, transport, or, trade data, goods or services.”

According to the abovementioned definition, the scope of e-commerce is quite narrow, including only buying and selling transactions. Consequently, the term “electronic business” or “e-business” was introduced to represent a broader con-cept, namely not only the buying and selling of goods but also conducting all kind

38 of businesses online such as providing services to customers, collaborating with partners, delivering e-learning and enabling transactions within the organization (Turban et al., 2017). Considering this definition of e-business, e-commerce can be also seen as a sub-set of e-business transactions.

The e-commerce market is extremely complex and heterogeneous in terms of ap-proach, service level, communication mode, order profile etc. A fundamental dis-tinction has to be made between B2C and B2B e-commerce. B2C e-commerce can be defined as the activity of selling products and services via Internet to end cus-tomers. This means that the customer coincides with the user. B2C e-commerce, instead, refers to online commercial transaction between one company to the other. As this thesis work focuses primarily on B2C e-commerce, it is interesting to define its features with respect to B2B e-commerce (Reynolds & Mofazali, 2000):

• The items sold are usually mass-market products.

• The value of a single transaction is usually lower with respect to B2B e-commerce.

• The purchasing process is usually shorter as it is based on the decision of a single individual. In B2B the time is stretched due to the need to stipulate a contract.

• The customer does not entertain a stable relationship with the merchant. On contrary, in B2B e-commerce contracts can last for long periods and can have a strategic implication.

• Usually, in B2C e-commerce the customer makes the purchase decision based on emotional factors. The price and the features of the products are less relevant in comparison to B2B e-commerce.

B2C e-commerce allows advantages for both the customer and the merchant. On the customers’ side, first it is possible to obtain products at lower prices. Also, there is the possibility to compare and choose between a larger variety of products and resellers. Products are more easily available and the purchase can include home delivery (Ghislandi, 212AD). On the producer’s side, the advantages in-cludes the bypass of additional intermediaries in the distribution network, which is reflected into higher margins and the possibility to set prices and offers in a flexible way (Reynolds & Mofazali, 2000).

39 Of course, B2C e-commerce implies many challenges from the logistics point of view. The order profile is completely different to the one related with the tradi-tional commerce. Smaller shipments make distribution complex and inefficient (Yu, Wang, Zhong, & Huang, 2016).

First of all, transportation costs increase due to the difficulty in saturating the ve-hicles for transportation. This is even more true due to the customers’ higher and higher expectations on the logistics service level, in terms of delivery lead time, delivery accuracy and offering of extra services, such as the possibility to return products (Osservatori e-commerce, 2018b). These features make the relationship between logistics performance and customer loyalty far more critical than in other industries (Ramanathan, 2010). Talking about transportation, the most difficult challenge is last-mile delivery, which is defined as the transfer of goods from a transportation hub to the final delivery destination (Dolan, 2018). Last-mile deliv-ery is, at the same time, a key to customer satisfaction, as it allows to differentiate the company’s offering with respect to competitors, and the most expensive trans-portation activity (Dolan, 2018). The last-mile route implies many stops, each cor-responding to a low value delivery. The inefficiency costs increase when the order density is lower, namely in scarcely populated areas (Dolan, 2018).

In addition to transportation costs, other cost categories increase. Handling costs are affected due to the need to guarantee a high service level in terms of delivery lead time, which from a logistics view point is reflected in an increase in the num-ber of distribution network layers. In addition, inventory carrying costs raise as a consequence of the broad range of products required by the customers and of the difficulties in the forecast of preferences. Nevertheless, e-commerce poses chal-lenges not only to the distribution network, but also to communities and society. This topic will be deepened in Section 1.3.

1.2 B2C e-commerce in Italy

In this section, the most significant facts and figures about B2C e-commerce in Italy are discussed, focusing first on the demand side and later on the offer side. In Italy, the e-commerce market reached 27,4 billion euros in 2018, out of the 600 billion euros of the European market, which is the third biggest market after China and the USA (Osservatori e-commerce, 2018a). Graph 2 shows the growing trend of the e-commerce purchases in Italy (Osservatori e-commerce, 2018a).

40

Graph 2: E-commerce purchases trend

Graph 3: Share of products and services in e-commerce purchases

The penetration rate was 6,5%, meaning that the 6,5% of the purchases made by customers in Italy are performed through e-commerce. Such number is below the European average of 10% penetration, indicating a slight delay in the adoption of e-commerce in Italy (Osservatori e-commerce, 2018a). Nonetheless, the delay is likely to decrease, considering the rapid growth which is being experienced: the marked increased by 16% in only one year between 2017 and 2018, in the face of a 12% increase in the overall European market (Osservatori e-commerce, 2018a). The e-commerce market is extremely broad and diverse. A first distinction is of course between products and service. Interestingly, 2017 was the first year in which the selling of products overcame the selling of services (Osservatori

e-0 5.000 10.000 15.000 20.000 25.000 30.000 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 mi ll io n € 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Products Services

41 commerce, 2017a), as can be seen in Graph 3. Currently, the share of products sell-ing is 56%, against 44% of services sellsell-ing, after a 25% increase in the last year. However, until now the e-commerce penetration rate is still low (5%), while for service it is double (10%) (Osservatori e-commerce, 2018a). The e-commerce mar-ket can be broken down further. Considering the service side, the most important industries in terms of sales and market share are (Osservatori e-commerce, 2018a):

• Tourism (9,8 billion €) • Insurance (1,300 billion €)

Instead, looking at the product side, the most important industries are (Osservatori e-commerce, 2018a):

• Informatics and electronics (4,6 billion €) • Apparel (2,9 billion €)

• Furniture and home living (1,4 billion €) • Food and grocery (1,1 billion €)

• Publishing (1 billion €) • Spare parts (0,7 billion €) • Toys (0,5 billion €)

• Beauty (0,4 billion €)

As can be easily imagined, the most significant growth is happening on the prod-uct side. The industries that have exhibited the most dramatic increase are food and grocery, whose growth rate was 43% between 2016 and 2017 and 34% between 2017 and 2018, furniture and home living (53% in 2018), apparel (20% in 2018) and informatics and electronics (18% in 2018) (Osservatori e-commerce, 2017a, 2018a). About the B2C e-commerce customers, they seem to be increasing in number. The number now has reached 23,5 million, after a 10% growth from 2016 to 2017 and an 8% growth between 2017 and 2018. Nevertheless, not all the web shoppers show the same purchasing behaviour. Only 17,8 million, corresponding to the 76% of the shoppers, generate 92% of the market. The figure was 74% in 2017, meaning that more and more people are becoming accustomed to the use of e-commerce websites. The remaining 24% of the shoppers only generate 8% of the market

42 (Osservatori e-commerce, 2017a, 2018a). For this reason, they are called “sporadic shoppers”.

From the offer point of view, the e-commerce market is very concentrated: the 20 biggest players in the market account for 72% of the overall sales and 43% of the sales comes from aggregators (Osservatori e-commerce, 2017b, 2018a).

1.3 E-commerce and sustainability

Environmental sustainability is defined in the following way (Cambridge University Press, 2018):

“The quality of causing little or no damage to the environment and therefore able to con-tinue for a long line”

However, looking at one of the first definitions, provided by the Bruntland Report for the World Commission on Environment and Development, it is clear that sus-tainability is not only about environment (Commissione Brundtland, 1987):

"Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."

In fact, sustainability is also related to economy and to the implications for society. Section 1.1 described the main benefits that e-commerce brings to the companies, namely the increase in the number of potential customers, the increased margins due to the elimination of intermediaries and the possibility to differentiate the of-fering also on the service side. Of course, such benefits come with challenges for the companies, namely the increased investment costs and operative costs and the increase in complexity of the distribution channel (Osservatori e-commerce, 2018a).

Nevertheless, the disruptive nature of e-commerce brings changes not only to the actors that are directly involved, but also to society as a whole. First of all, e-com-merce caused a general decrease in prices due to the increased competition (Osservatori e-commerce, 2018a). This challenges the producers, but at the same time it increases the purchasing power of the customers.

Another consequence of e-commerce that have been discussed by many is the im-pact on traditional jobs and employment. On the one side the introduction of

e-43 commerce and the rise of digital technologies have contributed to the crisis of tra-ditional retail and to the shift towards different models of shopping experience (BSIC, 2017; McKinsey, 2014). On the other side, the same phenomenon has con-tributed to the creation of new work places. According to some researchers, the use of digital technologies is not leading to the substitution of labour. The impact of ICT on employment seems to be neutral (Biagi & Falk, 2017). According to Terzi (2011), e-commerce will generate new jobs particularly in the information and communication technologies sector. The balance between lost jobs and creation of new jobs depends strongly on the demand for one skill or another.

Another topic discussed by many is the impact of e-commerce on urban areas and cities. However, the impact on the quality of life in cities is not clear. Some contri-butions reflect on the impact of traffic congestion. According to an article (Shao, Yang, Xing, & Yang, 2016), e-commerce can decrease traffic congestions in cities, due to the possibility of converting the physical flow of customers to retail stores into online flows.

At last, about the impact on environment in terms of emissions caused by the online purchase of goods, e-commerce seems to be an improvement in comparison to the traditional channel (L. Yi & Thomas, 2007). However, data are often misread and misunderstood, creating confusion among customers about the role of e-com-merce.

Several stakeholders’ groups are asking companies to be more explicit with re-spect to their policies on society, economy and environment. This has led to the creation of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). The GRI was the first organiza-tion which standardized the practices of company reporting on the matter of soci-ety and environment for the sake of transparency (GRI, 2018). The adoption of such standard gives value to the company, due to the increasing attention of cus-tomers towards corporate responsibility. Some studies have demonstrated the im-portance of such initiatives also for what concerns e-commerce. For instance, Ful-ton and Lee (2013) identified and reported the sustainable practices of many online retailers in the apparel goods industry based on the GRI standard.

This section highlighted that the implications of e-commerce do not involve only the relationship between customer and merchant, but also society and environ-ment as a whole. Indeed, researchers have dedicated time to the investigation of

44 such complex correlations and companies are making important steps to include such considerations in their operations. However, many misunderstandings are still present for what concerns the role of e-commerce. More efforts should be ded-icated to this topic, and in particular to the clarification of the impact of online activities on environmental sustainability. For this reason, the focus of this thesis work is on the environmental impact of e-commerce, which is approached adopt-ing a logistics perspective.

45

2 Literature review

2.1 Introduction to the literature review

In Section 2.1.1 the general objectives of the literature review and its specific focus are presented, disclosing details about the context in which research on the topic is conducted. Later, the method used to perform the analysis is described in Sec-tion 2.1.2.

2.1.1 Classification context

This literature review has several objectives. First, it is useful to have an overview about the state-of-the-art of the research on the topic under study, to become aware of industry-wide best practices and to debate the state-of-the-art solutions. Moreover, it is fundamental to identify which areas were neglected in the past years and which directions could be taken in the future. Of course, the ultimate goal is to clarify the research gaps that will be addressed by this thesis.

In the previous chapter, a definition of e-commerce was introduced as “the activ-ity of buying and selling products over the internet”. Several comments about the impact of e-commerce on the general economy, on the society and on the environ-ment were made, as well. Starting from the environ-mentioned considerations, it was de-cided to gather, in this literature review, all the past contributions to the issue of the environmental impact of B2C e-commerce from a logistics view-point.

More specifically, the focus of this review is restricted to B2C commerce, involving transactions between a company and a buyer, which is, usually, the user of the product. B2B transactions happening between companies are, instead, excluded. As widely discussed in the introduction (Chapter 1), B2C and B2B commerce im-ply totally different modalities of communication, of payment and totally different order profiles. For this reason, it is worth to analyse them separately, in order to take into consideration their specific peculiarities.

The importance of both B2C and B2B e-commerce has been raising over the last years. According to the data collected by Osservatori.net of Politecnico di Milano, in 2016 the B2B market in Italy was worth 310 billion euros, with an increase of 19% with respect to the previous year (Osservatori commerce, 2017b). B2C e-commerce instead only reaches 23,6 billion euros (Osservatori e-e-commerce,

46 2017a). However, due to its huge impact on mobility in cities, on traffic and on environment, especially due to last-mile delivery, it has been carefully analysed by numerous research institutions over the years (Carrillo et al., 2014; Cullinane, 2009; Fan, Xu, Dong, & Wei, 2017).

The perspective adopted during the literature review is the logistics one, meaning that more emphasis is put on the environmental impact of logistics activities such as warehousing, material handling, packaging and transportation activities. Also, the impact on environment of distribution network design and supply chain man-agement decisions is investigated. Of course, logistics activities involve exclu-sively physical flow of materials: as a consequence, only the product market will be considered, leaving aside the service market, which corresponds to about half of the total e-commerce volume in Italy, as already stated in the introduction (Sec-tion 1.2). Ultimately, the review will provide informa(Sec-tion about the consequences of ordering a product through the online channel, comparing this operation with the purchase of the same product offline, through the traditional channel.

The issue of environmental impact of e-commerce was already investigated in pre-vious literature reviews. Among the first were Abukhader and Jönson (2003), who encountered a general difficulty in generalising the outcomes of the environmen-tal assessments, in terms of advantages and disadvantages. Yi and Thomas (2007) instead, analysed how the use of ICT in commerce affects sustainability, identify-ing two predominant study modalities: a micro-level case study and a macro-level statistical approach. Even though named papers bring interesting standpoints on the matter, the works lack of structure and, most importantly, they are not current. Later, Velásquez (2009) provided in his review a useful classification between qualitative and quantitative studies. The latter, which provide numerical evalua-tions about the carbon footprint of e-commerce, are further divided into three main categories: products, services and tools.

The most recent literature review on the matter is the one by Mangiaracina et al. (2015). Therein, a complete outline of all the peer-review scientific articles pub-lished in international journals from 2001 to 2014 is provided. Also, the contribu-tions are classified according to the research method adopted, and analysed with respect to two dimensions: the areas of logistics which have the potential of

affect-47 ing the environment - namely transportation planning and management, ware-housing, packaging and distribution network design as a whole - and the unit preferred for the measurement of the environmental impact. The units listed are: energy use, gas emissions, waste generation and traffic mileage.

The one by Mangiaracina et al. is by far the most up-to-date and complete litera-ture review. For this reason, it is used as an important reference in this part of the thesis. However, some limitations need to be mentioned. To start with, some im-portant articles were published in the subsequent years, from 2014 to 2018. Such articles should be included to be aware about the state-of-the-art, considering the high rate of innovation in ICT applied to online commerce. Also, the width of the research efforts on the matter do not emerge clearly, in particular for what con-cerns the geographical scope and the market scope.

2.1.2 Review method

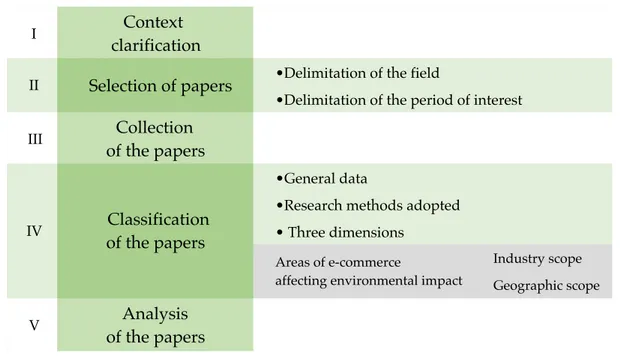

After clarifying the objective of this chapter and its context, it is worth spending some words to explain how the literature review was conducted. Figure 1 repre-sents a schema of the review method adopted.

Figure 1: Review method schema

The first phase consisted in the selection and in the collection of the contributions. Being the topic broad and extensively investigated, it was necessary to narrow

I Context

clarification

•Delimitation of the field

•Delimitation of the period of interest

III Collection of the papers

•General data

•Research methods adopted • Three dimensions Industry scope Geographic scope V Analysis of the papers Selection of papers Classification of the papers Areas of e-commerce

affecting environmental impact II

48 down the choice, considering only the most relevant papers. Therefore, it was de-cided to analyse only scientific papers published in peer-reviewed scientific jour-nals and the period of analysis was restricted to the last fifteen years, from 2003 to 2018. Also, only articles in which the chosen topic was the central focus were se-lected, whereas articles reporting only partial mentions of the analysed theme were excluded. During the collection, among the sources, the main paper aggre-gators - such as Scopus, Science Direct and Google Scholar - were considered. Some examples of the keywords used during the research are “environmental im-pact”, “carbon footprint”, “sustainability assessment”, “effect on environment”, “B2C e-commerce”, “online commerce”, ”online retail”, “logistics impact” etc. The completeness of the results was cross-checked by looking at prior available re-views and at the references of the most important articles.

Once the first phase was concluded, the scientific articles were categorized and the data were collected in a Microsoft Excel sheet. Data include the author, year of publication, the title of the publication, the journal and the geographic area of ref-erence. The papers were also classified according to the research method used. The ones considered were the most frequently used, namely analytical models, conceptual models, case studies, surveys/interviews, simulation and others, in-cluding all the least utilized methods. In addition, some dimensions were selected to give more depth to the study and to better identify gaps in the research. The first was inspired to the one used by Mangiaracina et al. (2015), highlighting the logistics areas affecting the environment. Two more dimensions were introduced to elucidate the industry scope and the geographical scope of the analyses, show-ing respectively whether the papers refer to a specific industry or to a generic case and whether it refers to a specific country or geographical area or to a generic place.

In conclusion, the articles were analysed according to the categories of data col-lected and to the chosen classification dimensions.

2.2 Review analysis

The previous chapters presented the objectives of the literature review and the method adopted. Herein, the results of the classification are presented and dis-cussed. More specifically, Section 2.2.1 reports the main features of the examined

49 articles. After that, Section 2.2.2 provides an analysis of the methods used by the researchers. Then, Section 2.2.3 dwells on the logistic areas most frequently tack-led and Section 2.2.4 describes the industry and geographical scope of the papers.

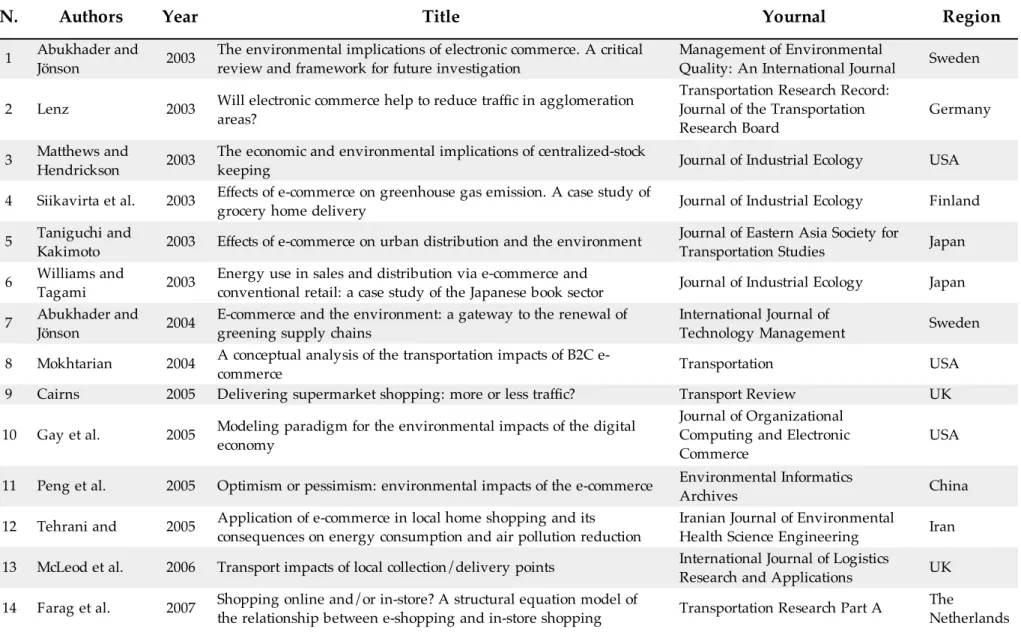

2.2.1 Main features of the selected scientific articles

The first phase of the articles selection and collection resulted in a database of 58 papers in total. As previously explained, the papers were categorised with respect to a number of voices, including title, author, year of publication, journal, geo-graphical region of reference, research method adopted and three additional clas-sification dimensions (areas affecting the environmental impact of e-commerce, industry scope and geographical scope). Table 1 reports data about all the selected papers.

Among the authors, some demonstrated a particular engagement on the topic of environmental assessment of e-commerce.

Abukhader and Jönson for example recognised the accelerating trend of electronic commerce and reviewed the contributions on its environmental impact with their critical review (2003). Then they tried to link the environmental impact of e-com-merce with the environmental impact of supply chains in general, by proposing some constructs for decision making (2004), in order to generalize the results of the research on this topic. At last they stated the need to enlarge the concept of eco-efficiency and eco-effectiveness in order to gain sustainability advantages from e-commerce (2008).

Other active contributors were Edwards, McKinnon & Cullinane, who con-structed an analytical method for the assessment of the carbon intensity of e-com-merce, with a specific focus on last-mile delivery and personal shopping trips (2010). Herein, they also recognised that home delivery is likely to generate a de-crease in emissions with respect to traditional shopping. The paper published one year later, instead, tries to highlight and solve methodological issues related to finding the carbon footprint of the different stage of online supply chain using a conceptual framework (J. Edwards, McKinnon, & Cullinane, 2011).

One last researcher who addressed more than one paper on the matter was Man-agiaracina, who reviewed the previous contributions (2015) and later formulated an activity-based model for the assessment of the carbon footprint of the purchas-ing process of one product in the apparel industry (Mangiaracina, Perego, Perotti,

50 & Tumino, 2016). The mentioned paper also presents a sensitivity analysis on a base case which highlights the huge impact of logistics on the total emissions stem-ming from a product.

Inspecting the source of the 58 peer-reviewed scientific articles included in the review, it can be noticed that they come from 39 different international scientific journals. Three main areas of belonging are recognisable among the journals. A first group includes logistics and supply chain management related journals, such as the International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management,

In-ternational Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, InIn-ternational Journal of Logis-tics Systems and Management, Transportation, Transport Review, Transport Policy and Research in Transportation Business & Management.

A second group of scientific journals includes publications related to environmen-tal sciences. Journal of Cleaner Production and Journal of Industrial Ecology were one of the most important sources. Others include The International Journal of Life Cycle

Assessment, Environmental International, Carbon Management, Environmental Infor-matics Archives, Environmental Science & Technology, International Journal of Environ-mental Science and Development, Management of EnvironEnviron-mental Quality: a Interna-tional Journal and Resources, Conservation and Recycling.

Third, it is necessary to mention journals related to other disciplines . In particular

Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce, Information Technology Journal, Journal of Food, Agriculture & Environment, Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, International Journal of Fashion Design, Technol-ogy and Education International Journal of Production Research.

Going on with the analysis of the scientific papers selected for the review, some more reflections can be made for what concerns the publication dates and the ge-ographical area of reference. As previously said, the period of interest was from 2003 to 2018. As can be noticed from Graph 4, the interest on the topic over the years has been proven to be fairly constant, fluctuating around the average of 3,6 published articles per year.

About the geographical area, research has been performed in three different con-tinents: North America, Europe and Asia. The extent to which researchers from different countries participated into the research efforts on the topic is depicted in Figure 2, where the diameter of the circles indicates the number of publications in

51 the countries of origin. It can be immediately noticed that the contributions come mainly from the USA (twelve publications), China (nine publications), UK (eight publications) and Italy (five publications).

In the USA the interest on the topic was equally spread over the thirteen years of the period of interest and no particular patters can be recognised in the topic of the publications.

Graph 4: Scientific articles' publication dates trend

Figure 2: Geographical distribution of the analysed scientific articles 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 N . o f p ap er s Average

52 In China instead, the popularity of environment and e-commerce rose primarily since 2016: five out of nine scientific articles were published in the last three years. The sub-issues which seem to cause the largest concerns are packaging and the effect of e-commerce in the mobility of the cities. Such issues are investigated mainly by means of analytical and mathematical models. In China, the environ-mental issue seems to be particularly critical. In fact, China is the country produc-ing the highest CO2 emissions in the world, with logistics activities accountproduc-ing for a big portion of such emissions (Zhang & Zhang, 2013).

Talking about UK and Italy, papers coming from the UK were published before 2014 and show a general concern towards grocery and fast moving consumer goods, whereas Italian researchers showed interest on the apparel industry among others and concentred their efforts after 2015.

2.2.2 Analysis of the research methods

This section is dedicated to the display of information about the methods adopted by researchers. As already explained in the introduction to this chapter (Section 2.1), the methods’ types considered for the sake of the classification were the fol-lowing: • Analytical models; • Case studies; • Conceptual models; • Literature reviews; • Surveys; • Simulation.

To start with, it is possible to observe in Graph 5 the distribution of the 58 analysed papers within the categories. The largest sample belongs to the analytical models’ category (twenty-two papers). Case studies (thirteen papers) and surveys (eleven papers) are following. The classes of conceptual models and simulation count eight papers each, whereas only four literature reviews were produced. In the fol-lowing, each category will be described in detail, with a particular attention on possible trends and correlations. Analysing the distribution of the methods used over time, no pattern is discernible for literature reviews and case studies. Con-ceptual models, surveys and simulation, instead, are condensed mainly in the first