1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Course of illness in bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is a severe, chronic and recurrent illness, with residual symptoms between episodes, that has a prevalence ranging from 1% (bipolar disorder type I) to 6.5% (bipolar spectrum disorders, including bipolar I and II disorders) in the general population (Vieta et al., 1997; Hirschfeld and Vornik, 2004; Merikangas et al., 2007). Bipolar disorder is one of the world’s 10 greatest public health problems (Murray and Lopez, 1997). Patients with bipolar I and II disorder spend half of their lifetime in a symptomatic state and almost all patients are bound to develop affective recurrences during their lifetime (Dittmann et al., 2002, Joffe et al., 2004, Post et al., 2003). Inter-episode symptoms are extremely common (Judd et al., 2003) as well. Despite the dramatic and life-disrupting nature of mania, some studies have documented that depressive episodes have the strongest impact on quality of life and functional outcome (Judd et al., 2005; Depp et al., 2006; Post, 2005; Hirschfeld, 2004).

In studies including only bipolar I patients, a depressive index phase predicts longer duration of time to full remission, more new phases, more time in any mood episode, and lower proportion of patients who reach full symptomatic and functional remission (Post, 2003; Nolen, 2004; Tohen, 2003). Patients with depressive symptoms have a higher suicidal rate and a higher suicidal behaviour (Valtonen et al., 2006; Galfalvy et al., 2006). Moreover, depressive symptoms are responsible for an increased risk of somatic illnesses, such as obesity and cardiovascular diseases, therefore reducing overall life

expectancy (Dilsaver et al., 1997; Fagiolini et al., 2002; Mitchell and Malhi, 2004).

To date, it remains unclear whether the proportion of time spent in different symptom states differ between bipolar disorder I and II and, if so, what the underlying factors explaining these differences are.

Judd et al. (2002) in a prospective naturalistic observation of symptomatic status in Bipolar I disorder found that days spent with depressive symptoms are about three times more common than days spent with hypomanic or manic symptoms.

In the NIMH Collaborative Depression study (NIMH-CDS; Judd et al., 2005; Coryell et al., 1989), Bipolar II patients had more often a least one new depressive phase, a higher number of depressive phases, and spent more time in phases of major depression and depressive symptoms than bipolar I patients. The NIMH-CDS study reported several clearly defined outcome measures, such as duration of index episode and time to full remission to be associated with the longer duration of depression in Bipolar II patients (Judd et al., 2002, 2003, 2005; Coryell et al., 1989).

Demographic and clinical variables, known to correlate with outcome in bipolar disorder, such as age at onset or comorbidity, differ between bipolar I and II, and in most studies they are not at all described or controlled for, making it difficult to identify factors affecting course of illness in bipolar I and II disorder. Furthermore, naturalistic studies, reported that Bipolar II disorder is known to be more often misdiagnosed (Mantere et al., 2004) and managed uncorrectly (Judd et al., 2003, Hadjipavlou et al., 2004).

In one prospective study, patients with BD II are reported to spend a higher proportion of time ill and in depressive symptom states than BD I patients

(Mantere et al., 2008).This was a result of the higher proportion and mean number of depressive illness phases in BD II, rather than of differences in the duration of depressive phases.

The high functional disability associated with Bipolar II disorder might be due to the higher prevalence of depressive recurrences and to the clinical and subclinical depressive symptoms, rather than to the cross-sectional severity of acute episodes (Judd et al., 2002, 2003; MacQueen et al., 2003).

1.2 Does treatment affect course of illness?

Amongst the factors affecting outcome and course of illness in bipolar disorder, pharmacological treatment plays a pivotal role.

Despite the availability of novel pharmachological agents, full recovery without further episodes is rare, recurrences with incomplete remission are the rule and the development of chronicity and eventually suicide is still frequent (Angst and Sellaro, 2000). There is suggestive evidence that lithium (Baldessarini and Jamison, 1999; Tondo et al., 1998; Rihmer et al., 2008) and probably valproate (Bowden et al., 1998) reduce the risk of suicide during maintenance treatment. Moreover, the treatment of bipolar disorder has improved considerably with the introduction of new anticonvulsants and antipsychotics (Lopez-Munoz et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2003; Sanger et al., 2001; Altamura et al., 2003). The results of several clinical trials suggest that atypical antipsychotics including risperidone, olanzapine, ziprasidone, aripiprazole and quetiapine are effective in treating acute mania with long-term mood-stabilizing effects (Sanger et al., 2001; Altamura et al., 2003; Vieta et al., 2004 a, b; Yatham, 2003; Savas et al., 2006; Keck et al., 2006). The

use of antidepressants in patients with bipolar disorder without concomitant use of a mood stabilizer may increase the risk of manic switches, mixed states, or accelerated cycling (Ghaemi et al., 2000; Calabrese et al., 1999; Altshuler et al., 1995; Wehr et al., 1988; Wehr and Goodwin, 1987). Tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors which are often used to treat unipolar depression are also commonly used to treat depression in bipolar disorder. These agents can induce a manic episode, which also can pose significant harm to the patient and others. Evidence supports an increase in switch rates among patients with bipolar disorder treated with antidepressants (Calabrese et al., 1999; Altshuler et al., 1995; Wehr and Goodwin, 1987). Tricyclic antidepressants are associated with the highest rates of switching, while bupropion, paroxetine and moclobemide may have lower switch rates (Sachs et al., 2000; Calabrese et al., 1999).

1.3 Does comorbidity with anxiety disorders affect course of illness?

Bipolar disorder is associated with high rates of comorbidity. Comorbidity with Axis I disorders is estimated at 50 % in bipolar I patients (Kessler et al., 1994) and 60% in Bipolar II patients (Benazzi, 1997); the most frequent disorders that co-occur in Bipolar II patients are substance abuse (Regier et al., 1990), anxiety disorders (Chen et al., 1995), and eating disorders (Mury et al., 1995). Substance abuse disorders are (Judd et al., 2003) over-represented among bipolar I and II patients as compared to the general population.

In a recent large scale investigation, more than half (51.2%) of patients with bipolar disorder were identified as having a co-occurring anxiety disorder at some point in their lifetime, while 30.5% were diagnosed as having a current

anxiety disorder (Simon et al., 2004). In the community, the lifetime prevalence of panic disorder is 20.8% among bipolar I patients versus 10% among unipolar patients (Chen and Dilsaver, 1995). A growing number of epidemiologic studies show that bipolar disorder co-occurs with anxiety disorders at rates that are significantly higher than those in the general population (Angst, 1998; Chen and Dilsaver, 1995a, b; Kessler et al., 1997; Szadoczky et al., 1998). In the Epidemiological Catchment Area study, which pooled persons with bipolar I and Bipolar II disorders, 21.0% had lifetime panic disorder and 21.0% had lifetime obsessive-compulsive disorder, as compared to 0.8 and 2.6%, respectively, in the general population group (Robins and Regier, 1991). In the National Comorbidity Survey, 92.9% individuals who met criteria for lifetime bipolar I disorder also met criteria for lifetime anxiety disorder, as compared to 24.9% of the general population sample (Kessler et al., 1994; 1997).

Anxiety comorbidity has been associated to worse clinical presentation and unfavourable course in mood disorders, particularly; a growing literature indicates that anxiety comorbidity is common and disabling in individuals with bipolar disorder (Kessler et al., 1997; McElroy et al., 2001). Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder is associated with a number of negative sequelae, including greater severity of affective episodes, reduced duration of euthymic episodes, increased substance abuse, greater functional impairment, and an overall diminished quality of life (Cassano et al., 1999; Simon et al., 2004; Young et al., 1993). Moreover, anxiety comorbidity bodes poorly for the prognosis of bipolar disorder and its treatment outcome (Feske et al., 2000), and both anxiety disorders and anxiety symptoms have been clearly linked to higher risk of suicidal ideation and attempts (Engstrom et al.,

2004; Fawcett et al., 1990; Frank et al., 2002; Simon et al., 2004; 2007). Anxiety symptoms have been found to occur relatively frequently in both the manic and depressive phases of bipolar disorder. In a study of 316 inpatients with manic or mixed episodes, 39% were rated as having some degree of anxiety (Cassidy et al., 1998). Feske et al. (2000) examined anxiety as a correlate of lithium acute treatment response in 124 patients with bipolar I disorder (66 depressed and 58 manic or mixed), and found that current or past anxiety symptoms were significantly associated with longer time to remission; a history of panic attacks was significantly correlated with non-remission. Factor analytic studies of the signs and symptoms of mania found that anxiety loads with depressed mood in mania (Cassidy et al., 1998; Dilsaver et al., 1997). However, specific studies focusing on the difference of the association of disabling course and anxiety in bipolar I and II disorder, are lacking.

The association between panic disorder and bipolar disorder is robust (Altindag et al., 2006; Dilsaver et al., 2006). Epidemiological data confirm that panic disorder is highly prevalent in bipolar and unipolar depression; in some studies, panic comorbidity in bipolar patients ranges from 20 to 33% (Dilsaver et al., 1997; Kessler, Rubinow, Holmes, Abelson, and Zhao, 1997; Chen and Dilsaver, 1995a; Rihmer et al., 2001; Mitchell et al., 2004). In clinical samples of bipolar outpatients, the prevalence of panic disorder comorbidity is also high, with reported rates ranging from 2% to 37% (Boylan et al., 2004; Feske et al., 2000; Goodwin et al., 2002; MacQueen et al., 2003; McElroy et al., 2001; Simon et al., 2004; Vieta et al., 2001). Other studies have reported high prevalence of bipolar disorder in patients with panic disorder (Bowen et al., 1994; Savino et al., 1993; Perugi et al., 1999, Toni et al, 2008). In a recent

study, Toni et al. (2008) showed how, in a sample of 326 outpatients with panic disorder, 16% of subjects also had comorbid Bipolar II disorder. When comparing patients with or without bipolar comorbidity those with Bipolar II disorder showed a significantly higher frequency of social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, alcohol-related disorders, and separation anxiety during childhood and adolescence. In the same study Bipolar II patients had a family history of panic disorder and mood disorders significantly higher as compared to the non bipolar ones.

The occurrence of panic disorder in bipolar patients was associated with poorer response to treatment, earlier onset of bipolar disorder, elevated rates of comorbid psychopathology, greater levels of depression, more suicidal ideation and increased familial risk of affective disorders (Frank et al., 2002; Pini et al., 1997). Patients with lifetime panic symptoms required a greater number of medications, either sequentially or in combination, in order to achieve remission (Feske et al., 2000). High scores in the Panic-Agoraphobic Spectrum Scale-Self-Report were associated with more depressive episodes (but not manic) in the course of bipolar I disorder and longer time to remission from the index episode (Frank et al., 2002). A panic disorder diagnosis or a history of panic attacks was associated with an earlier age at onset of bipolar I or II disorder (Simon et al., 2004), but no associations were found between these comorbidities and number of hospitalizations, psychotic symptoms, suicide attempts, and current or past addictive behaviour (Henry et al., 2003). History of panic attacks was associated with substance dependence comorbidity in the National Comorbidity Survey sample of individuals with bipolar disorder (Goodwin et al., 2002). In a study of Simon et al., 2004, lifetime panic disorder comorbidity was associated with higher rates of lifetime

alcohol dependence and suicide attempts, and current panic disorder was associated with diminished quality of life and impaired role functioning.

1.4 Objective of the study

As extensively reported above, data about factors affecting course of illness in bipolar I and II disorders are sparse.

The present study is a naturalistic prospective investigation carried out over a period of 2 years enrolling a sample of secondary care bipolar I and II patients.

Our overarching aims were to:

1) Provide a detailed description of the course of illness in bipolar disorder;

2) Provide a comparative evaluation of clinical features affecting course of illness in bipolar I and II disorder.

3) Investigate the impact of panic disorder comorbidity on illness course.

2. METHODS

2.1. PARTICIPANTS

Study participants were 194 adult subjects recruited from 2004 to 2006 in the Day-Hospital and inpatient ward of the Department of Psychiatry, Neurobiology, Pharmacology, and Biotechnology, Section of Psychiatry of the University of Pisa.

The study enrolled all subjects with a diagnosis of Bipolar I or Bipolar II disorder.

Exclusion criteria were: a) current substance abuse/dependence, b) neurological disorders, c) severe and unstable medical illness, and d) pregnancy.

Two senior psychiatrists (LM, LL) were responsible for the clinical management of the study subjects carried out according to current standards for the treatment of bipolar disorder. All assessments were completed by independent raters extensively trained in the use of assessment instruments, and who were not directly involved in the patients’ psychiatric care.

Patients’ prospective follow up ranged from a period of 16 to a period of 100 weeks (mean 65 ± 37). Drop-outs were 50 at the 16th week, 24 at 32nd week, 7 at 48th week, 10 at 64th week, 9 at 80th week, 6 at 96th week. Eightyeight (45.4%) patients completed the full 100 weeks follow-up. Among the study drop-out patients (N=106), 92 were reached by phone, and reported the reasons of withdrawal: distance from city of residence (47.2%), low compliance (14.2%), or remission (25.5%).

2.2 PROCEDURE

Axis I diagnoses were established by means of the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I/Patient version (SCID-I/P, First et al., 1994).

Demographic and retrospective clinical data were collected using the Semistructured Interview for Mood Disorders (SIMD) (Cassano et al., 1987), which was developed to collect systematic anamnestic data on number of previous episodes, patients with current and lifetime suicide attempts and number of previous suicide attempts, congruent and incongruent psychotic

symptoms and family history data. The semi-structured face-to-face interview, which lasts 30-60 minutes, is well accepted by patients.

The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation (LIFE) (Keller et al., 1987) is an integrated system for assessing the longitudinal course of psychiatric disorders. It consists of a semi-structured interview, an instruction booklet, a coding sheet, and a set of training materials. An interviewer used the LIFE to collect detailed psychosocial, psychopathologic, and treatment information for the follow-up interval. The LIFE interview was administered every 16 weeks any DSM-IV disorder can be rated; LIFE scores are as follows: 1 (asymptomatic, returned to usual self), 2 (only one symptom, of low severity, without any functional impairment), 3 (low severity symptoms, with limited impairment, not definite criteria for the diagnosis), 4 (definite criteria for the diagnosis, symptoms of moderate severity), 5 (definite criteria, severe symptoms), 6 (definite criteria, very severe symptoms). Frequencies of scores for the four affective states -depression, mania, hypomania and mixed states- were calculated over the period of prospective observation and were mutually exclusive. The percentage of time spent with depressive, manic or hypomanic and mixed symptoms was calculated for each patient (number of weeks with a score of 4 or more for each affective state / the lenght of observation, in weeks, X 100). The definition of depressive, manic or hypomanic and mixed remission and recurrence was based on DSM-IV criteria.

LIFE also allows to record weekly variations of prescribed treatment and dosages.

The Ethical Committee at the University of Pisa, School of Medicine, reviewed and approved the study procedures and all subjects signed an, informed consent form after receiving a full description of the study and being

given the opportunity to receive clarifications.

2.3 Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted by means of Intercooled Stata 8.2 (2004, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Differences on continuous variables among the clinical groups were analyzed using Student’s T-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test when appropriate. One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were conducted to compare four groups (Bipolar I and II patients with and without panic disorder), followed by post-hoc pairwise comparisons. Chi-square test (the two-tailed Fisher’s exact test, when appropriate) was used to compare proportions among the study groups. A Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was applied to the probability level (0.05/4=0.013).

3. RESULTS

The study recruited 194 patients, 62 (32.0%) were males, mean age at intake was 40.2 years (SD=13.4).

123 (63.4%) subjects received a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder and 71 (36.6%) of Bipolar II disorder.

In the total sample, mean age of onset was 27.4 (SD=11.5) years and mean length of illness was 12.4 (SD=10.3) years. Patients had an average of 9.8 (SD=18.7) previous episodes (of which an average of 5 (SD=9) were depressive) and had 1.7 (SD=2.2) hospitalizations before entering the follow up; 54.3% of patients (89/194) reported a family history of mood disorders.

Overall, 30.2% of patients had a lifetime history of suicide attempts, and the mean number of past suicide attempts was 0.5 (SD=0.9).

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics did not differ significantly between Bipolar I and Bipolar II patients (see table 1).

Bipolar I had a significantly earlier age of onset (coded as onset of first affective episode) (M 25.8±10.2 years in Bipolar I, M 29.9±13.1 years in Bipolar II, 2 2.30, p .022) and reported a higher number of previous hospitalizations ( 2 –1.98,p .048). Patients were enrolled during a depressive episode in 52.1% of cases, 5.6% were hypomanic, 18.7% were manic and 23.6% mixed. 17/194 patients (8.8%) showed a polyphasic index episode (a rapid shift from one polarity to another, without full remission between episodes). 37/194 patients (19.1%) were included during clinical remission. 32.5% of patients presented with psychotic features. Bipolar I patients presented more frequently with psychotic symptoms during the index episode, as reported in the SIMD ( 2 25.0,p <0.001).

92.8% of Bipolar II patients had a depressive onset of illness, compared to 65.5% of Bipolar I ( 2 117.3, p <0.001). Moreover Bipolar II patients had a higher number of previous depressive episodes (z 2.68, p .0074).

No difference emerged between diagnostic groups in lifetime history of suicide attempts and previous episodes of attempted suicide (see table 1).

3.1- Course of bipolar I and II disorder during follow up

Follow up period ranged from 16 to 100 weeks (mean 65.2, SD 37) in the total sample and observation length was 65.2 ± 37.0 weeks and was similar in the two diagnostic groups (M 64.7± 37.4 weeks in Bipolar I, M 65.9± 36.5 weeks

in Bipolar II).

The mean length of the index episode was 8 (SD=9.9) weeks.

Bipolar II patients entered our study in a depressive phase more frequently (coded as depressive index episode) than Bipolar I patients ( 2 32.9, p <0.001).

Our subjects spent an average of 25 weeks (SD=28.7) of the follow up period in a symptomatic state with no significant differences between Bipolar I and II patients, nevertheless, the proportion of time spent depressed during follow-up was significantly higher in Bipolar II patients (z 6.10, p <0.001), while Bipolar I patients spent significantly longer time in a manic or hypomanic state (z -2.4, p .016) and such difference broadens if mixed episodes are included (z -5.28, p <0.001).

The index episode duration was similar in the two diagnostic groups (z.58, p .57).

When we analyzed the length of time spent ill during the follow-up period after excluding the duration of index episode we found that Bipolar II patients spent significantly longer time ill (z 3.98; p .0001) and spent significantly more time depressed as compared to Bipolar I (z 4.40; p <0.001).

We found no significant difference in number of patients with at least one recurrence during follow-up in the two groups ( 2 .02, p .89), but the total number of recurrences during follow-up was higher in Bipolar II than Bipolar I patients (z 2.09, p .037). Moreover, the first recurrence was more frequently a depressive one in Bipolar II patients as compared to Bipolar I ( 2 21.88, p .000; see table 2).

3.2-Comorbidity

In our total sample we found a very high comorbidity rate with any lifetime anxiety disorder (71%) and almost half of the subjects had a current (during our observation period) comorbidity with one anxiety disorder (94/194 subjects).

We did not find significant differences in comorbidity rates for anxiety and eating disorders or substance abuse between Bipolar I and II patients (see Table 3).

3.3- Treatments

Table 4 shows the distribution of pharmacological treatments in the two groups. In our sample, 93 patients (49.5%) received Lithium, with a higher percentage in Bipolar I than Bipolar II patients ( 2 15.8, p .000).

Anticonvulsants were administered in 141 subjects (75% of the whole sample) with no significant difference between groups. Both first and second generation antipsychotics were more frequently prescribed to Bipolar I patients ( 2 8.80, p .003 and 2 14.05, p .000, respectively), while Bipolar II patients were given antidepressants more frequently than Bipolar I patients (Tricyclics: 2 9.29, p .002, SSRIs: 2 9.60, p .002, Others: 2 3.94, p .047). Benzodiazepines were prescribed to 28 patients, 14.9% of our sample, with no difference between groups.

3.4- Impact of Panic Disorder in prospective course of bipolar I and II disorder

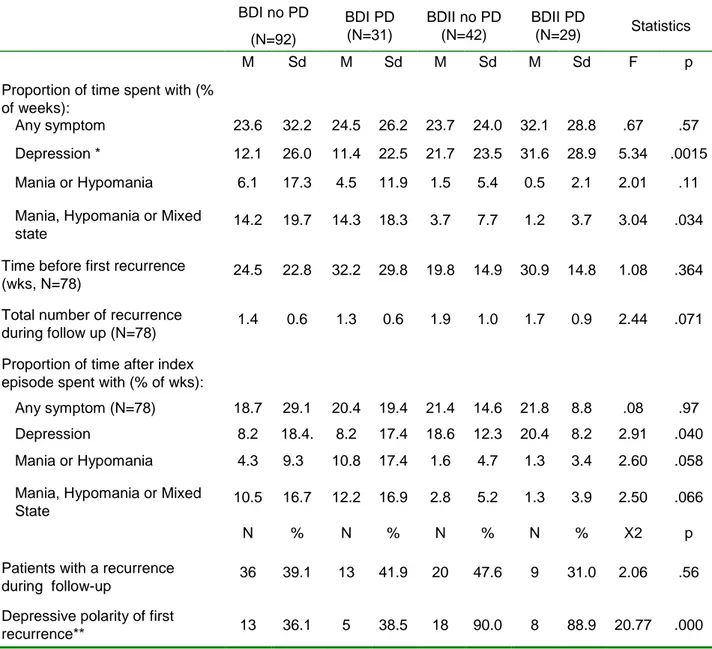

The table 5 and 6 report differences in illness course variables between Bipolar I and Bipolar II patients with and without Panic Disorder (PD).

Variables describing retrospective course of illness did not differ significantly in the 4 groups.

Variables describing prospective course of illness during the observation period were significantly different in the 4 groups (E.g.: proportion of time spent in depressed state, F 5.34 p .0015 and the depressive polarity of first recurrence, 2 20.77 p .000), but post-hoc comparisons revealed that such differences were accounted only by differences between diagnostic groups, independently of comorbidity with panic disorder.

We also calculated the frequencies of suicidal attempts in Bipolar I and Bipolar II patients with or without PD, but we found no differences in the number of patients who attempted suicide in the past and during the current episode, the number of previous suicidal attempts was similar in the four groups, as well.

When we analyzed the drug treatment in Bipolar I and Bipolar II patients with or without PD, we found significant differences between diagnostic groups, as reported above, but no further difference was found to be attributed to the comorbidity with Panic Disorder (see table 7).

4. DISCUSSION

Our study is a naturalistic prospective description of course of illness in a population of bipolar patients representative of a tertiary level of care.

Mean age at onset of the subjects enrolled in our study was 27.5±11.4 years and mean duration of illness was 12.4±10.3; 33.7% attempted suicide at least once in their lifetime and 54.3 % reported a family history of mood disorders. When comparing these data with the recent STEP-BD investigation (Simon et al, 2007) we find an overall lower severity of psychopathology.

In our sample, gender distribution did not differ significantly between Bipolar I and II patients, nevertheless, as expected, female gender is overrepresented in Bipolar II sample, consistently with previous reports (Menchon et al., 1993; Vieta et al., 1997; Viguera et al., 2001).

Bipolar I patients had significantly earlier age at first occurrence of an affective episode compared to Bipolar II patients, and an overall worse retrospective course with higher number of hospitalizations, they also reported more psychotic symptoms at intake, in agreement with what already reported by previous studies (Judd et al., 2003; Tondo et al., 1998; Vieta et al., 1997; Angst, 1986; Coryell et al., 1985; 1989; Ayuso-Gutierrez and Ramos Brieva, 1982). Mean age at onset is similar to that found by Mantere et al in the Jorvi Bipolar Study (Mantere et al 2007).

Bipolar II patients reported more frequently a depressive polarity at illness onset (92.8%). “Polarity at onset” has been shown to be familial (Kassem et al., 2006) and to distinguish groups of bipolar individuals who differ in lifetime clinical features of illness. Findings of previous studies reported that patients whose first episode of illness was depression have a predominantly depressive lifetime course of illness, a greater number of depressive episodes and an increased risk of suicide attempts (Perlis et al., 2005, Perugi et al, 2000; Forty et al., 2009). In our sample, Bipolar II patients had a higher number of previous depressive episodes, 80% of them entered our follow up

in a depressive phase and, after the index episode, Bipolar II patients spent significantly more time ill and had a higher number of depressive recurrences. Even if our study is a naturalistic investigation and therefore was not designed to compare polarity of onset in different groups, we can speculate that Bipolar II patients are more likely to have a depressive onset of illness and therefore are bound to develop a predominantly depressive lifetime course of illness, a worse outcome (more time spent ill) and possibly a more rapid cycling (greater number of recurrences in a given time).

The importance of these findings is twofold: 1) the clinician can use knowledge of polarity of illness onset as an indicator of the likely predominant pole of illness and this may be helpful in providing information and advice to the patient; 2) there are studies reporting differences in the clinical characteristics of depressive episodes in patients with unipolar and bipolar disorder (Bowden et al, 2005; Mitchell et al., 1992; Forty et al., 2008), thus, in a situation in which a patient has experienced his or her first depressive episode, such differences could potentially be of use in predicting the risk of bipolar disorder.

Our retrospective results show that 30.2 % of our Bipolar patients had attempted suicide once in their lifetime, this percentage is in line with results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey (Chen and Dilsaver, 1996) which reported a lifetime rate of suicide attempts of 29.2% in this diagnostic group regardless of age, sex, socioeconomic status and comorbidity with Panic Disorder. We found no difference in current and lifetime suicide attempts between Bipolar I and II patients. Previous reports found that patients with depressive onset of illness had an increased lifetime risk of suicide (Forty et al, 2009), however these associations were found only in

samples of Bipolar I patients and therefore are not generalizable to our clinical population.

The most frequent polarity of episode at referral to our clinic was depression (52.1%) followed by mixed episode (23.6%), suggesting a specific pattern of treatment seeking behaviour of this population of patients who are more likely to seek specialist care during depressive phases. (Das et al., 2005).

Our cohort of Bipolar I and II patients display several differences in the course of illness during the follow up period.

To collect prospective course variables we have used the LIFE, a semistructured interview and rating system for assessing the longitudinal course of psychiatric disorders in sufficient detail to enable researchers to date individual episodes of any psychiatric disorder and thus to provide the basis for an accurate calculation.

Bipolar II patients entered the study more frequently in a depressive phase (80% versus 36% for Bipolar I).

Overall, Bipolar II patients spent a greater proportion of time in a depressive state; moreover, they spend more time ill after remission of the index phase. As reported by several authors, a depressive phase lasts longer than other phases and often ends in residual symptoms (Nolen et al, 2004; Keller et al, 1986; Coryell et al, 1998), therefore it is likely that polarity of index phase may have influenced the following proportion of time spent in a symptomatic state. Our findings are in line with the NIMH Collaborative Depression Study (Joffe et al 2004, Judd et al 2003), and the Jorvi Bipolar Study (Mantere et al 2008), while in other cohorts no difference was evident with regards to depressive course (Post et al, 2003; Nolen et al, 2004). Our Bipolar I patients did not spend more time in a manic or hypomanic state after remission of the index

episode. Bipolar II patients had higher number of recurrences and a greater likelihood of having a depressive first recurrence as compared to Bipolar I, so perhaps the difference that exist between Bipolar I and II patients concerning the depressive course may be due to the higher number and depressive polarity of recurrences.

Pharmacological treatment was not the main focus of our naturalistic study, but some interesting findings appeared.

Lithium and second generation antipsychotics were prescribed more frequently to Bipolar I than Bipolar II patients. Anticonvulsants were administered in 75% of the entire sample, without differences between groups. Interestingly, our finding that Bipolar II patients spend longer time depressed during follow up is in line with the Collaborative Depression Study where Bipolar II received fewer mood-stabilizers; the other cohorts, where treatment was more strictly controlled, showed no difference.

The frequency of Antidepressants prescription is similar to that found in previous studies (Blanco et al., 2002; Ghaemi et al., 2006; Olfson et al., 2002). Regardless such a large utilization of antidepressant among both Bipolar I and Bipolar II patients we did not record any manic switch episode for the duration of the observation period.

71% of our participants reported a lifetime comorbidity for any anxiety disorder and 48.5% reported a current anxiety disorder comorbidity. Frequency of comorbidity found in our sample are higher than those reported by other studies (Kessler et al., 1994; Benazzi, 1997). The STEP-BD Study reported 62% of lifetime and 30% or current comorbidity for anxiety disorders (Simon, 2007).

The comparison between BDI and BDII with and without PD current comorbidity did not show any clinical and psychopathological difference. This is in contrast with previous experiences which report a negative impact of panic and anxiety

disorders in the course of BDI and unipolar depression (Frank et al., 2002; Toniolo et al., 2009). In the study of Toniolo and colleagues (2009), BD I patients with PD had a significantly higher number of episodes of both polarities. The higher

frequency of depression as the first mood episode in patients with PD comorbidity (94.1%) has important clinical implications, such as the difficulty in identifying these depressions as bipolar and the risk of manic switching if these episodes are

treated with antidepressants. BDI patients with PD comorbidity may be more

vulnerable to mood recurrences, including mania, and manic states may trigger PD and PD may get worse the BD in terms of clinical severity. So that an appropriate pharmacologic treatment in these patients should be chosen cautiously:

antidepressants, which are regarded as the first option for the treatment of PD, carry the risk for manic switching and cycle acceleration (Altshuler et al, 1995; Leverich et al., 2006; Tamada et al., 2004).

Often, the association between bipolar and panic disorder seems to lead to treatment resistance and chronicity (Cassano et al., 1999; Simon et al., 2004, 2007; Young et al., 1993; Feske et al., 2000; Engstrom et al., 2004; Frank et al., 2002; Tohen et al., 2007), as well as to high rates of suicide attempts (Weissman et al., 1989; Fawcett, 1992; Chen and Dilsaver, 1995). Several studies have shown that an Axis I psychiatric comorbidity, such as substance use disorders and anxiety disorders, included panic disorder is associated with an earlier age at onset of BD (McElroy et al., 2001; Pini et al., 1999; Sonne et al., 1994; Scǖrhoff et al., 2000; Simon et al., 2004). On the other hand, patients with PD who attempted suicide were significantly more likely to suffer from major depressive episodes and alcohol

or other substance abuse (Jonhson et al., 1990; Lepine et al., 1993; Hawton et al., 2005; Azorin et al., 2009). Our data suggest no difference in the number of suicide attempts between bipolar patients with and without PD consistent with the

observed lack of effect of panic on the overall course of illness.

In the study by Simon et al. (2004) PD comorbidity was associated with higher rates of lifetime alcohol dependence, suicide attempts, impaired quality of life and role functioning.

Henry and colleagues (2003) results were similar to ours: with the exception of the earlier age at onset for the bipolar disorder in patients with comorbid PD, with scarcely relevant impact on the outcome of bipolar illness.

The large use of antidepressants in our sample of both bipolar I and II patients did not seem to modify the course of the mood disorder. There were no statistically significant differences in rates of hypomania or mania between patients treated and patients not treated with antidepressants in either the non-comorbid or comorbid populations (Tohen et al., 2007).This could be explained by the high number of prescriptions of anticonvulsants which may had preventive effect for BDI and BDII patients with comorbid anxiety treated with antidepressants. Moreover, mood stabilizing treatments may both improve panic and affective symptoms in bipolar patients. It is possible that an appropriately tailored treatment for anxiety disorders in association with a robust mood stabilizing therapy, may have

prevented a deterioration of the course of illness in panic-bipolar patients.

Nevertheless, some studies reported that patient’s response to treatment can be dampened by comorbid anxiety (Frank et al., 2002; Gaudiano and Miller, 2005).

Strenghts and Limitations

Our cohort is a homogeneous population representative of patients referred to a tertiary level of care. In our study all the diagnoses were performed by a medical team trained in clinical diagnosis and treatment of affective disorders and specifically trained in the use of diagnostic instruments. All diagnoses were discussed with the senior clinics (LM, LL). Moreover, patients were intensively followed up with monthly visits and 16-weeks assessments of clinical status. On the one hand, this method may have a higher reliability compared with both previous retrospective studies, and with prospective studies that implicate long intervals between assessments. On the other hand, it may improve the compliance to treatment and adherence in the follow-up period.

Unfortunately we have a high drop-out rate and few information on reason for withdrawal. The attrition rate may account for some of the differences. It is possible that bipolar patients with severe course of illness were less easily retained in follow-up, or and the opposite occurred for Bipolar II patients. Patients who continued the prospective observation in the study may have a more favourable course and higher compliance to treatment.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This study is a naturalistic investigation of the course of illness in bipolar disorder.

Bipolar disorders are heterogeneous and the identification of peculiar pattern of illness course has the potential to facilitate more targeted clinical advice

and interventions.

Subjects referred to our tertiary care centre were moderately severe with a relatively high age at onset.

The majority of subjects sought specialist help during a depressive or a mixed phase.

92.8% of our Bipolar II patients had a depressive onset of illness, entered the study in a depressive phase in 80% of cases, and in agreement with findings from previous investigations, developed a predominantly depressed lifetime course with more recurrences of a depressive polarity and significantly higher time spent ill compared to Bipolar I patients.

These findings are of pivotal clinical importance suggesting that Bipolar patients with depressive polarity of onset of illness and in a current depressive phase are more likely to develop a predominantly depressive course with an overall longer time spent ill and a higher number of recurrences with implications for treatment.

Our study does not confirm the data regarding the association between PD and poorer course and outcome of bipolar disorder. This difference from literature could be due to the short length of observation, or to the characteristics of the sample, that included patients with severe forms of illness, independently from the

presence of panic disorder.

Moreover, for a deeper understanding of the influence that a specific anxiety disorder may have on the severity bipolar illness, it would be important to include not only anxiety disorders but also the anxiety spectrum simptomatology that may coexist in BD patients, since categorical classification may not detect the impact of subsyndromal anxiety symptoms

and their subsequent impact on clinical course and outcome of mood disorders.

Some instruments specifically drawn up to estimate the subthreshold panic symptoms such as the structured clinical interview for panic-agoraphobic spectrum (SCI-PAS) (Cassano et al., 1999) could identify a subgroup of bipolar patients with high scores of panic symptoms with a deteriorating course of illness and a poor response to treatment.

Future studies should focus on this issue, and should be specifically designed adopting a psychiatric team-management providing continuity of care in order to reduce the number of drop-outs; the utilization of specific instruments assessing complex threshold and subthreshold symptomatology, and, finally, an accurate selection of outcome measures to evaluate response to treatment and functional impairment

7. REFERENCES

1) Altamura A. C., Salvadori D., Madaro D., Santini A., Mundo E. Efficacy and tolerability of quetiapine in the treatment of bipolar disorder: preliminary evidence from a 12-month open-label study. J Affect Disord 76: 267-71 (2003)

2) Altindag A.,Yanik M., Neioglu M. The comorbidity of anxiety disorders in bipolar I patients: prevalence and clinical correlates. Isr J Psychiatry Relat. Sci.43: 10-15 (2006)

3) Altschuler L.L., Post R.M., Leverich G.S., Mikalauskas K., Rosoff A., Ackerman L. Antidepressant-induced mania and cycle acceleration: a controversy revisited, Am J Psychiatry 152: 1130-1138 (1995)

4) APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV). Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association, (1994) 5) American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 159: 549-550 (2002)

6) Andreasen NC., Endicott J., Spitzer RL., Winokur G. The family history method using diagnostic criteria. Reliability and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 34(10): 1229-1235. (1977)

7) Angst J., Sellaro R., MerikangasK.R. Depressive spectrum diagnoses. Compr Psychiatry 41 (suppl 1): 39-47 (2000)

8) Angst J. : The emerging epidemiology of hypomania and bipolar II disorder: research report, J Affect Disord 50 : 143-151 (1998)

9) Angst J.: The course of major depression, atypical bipolar disorder, and bipolar disorder. In: Hippius H. (Ed.), New Results in Depression Research, Springer-Verlag, Berlin (1986)

10) Azorin JM., Kaladjian A., Adida M., Hantouche E., Hameg A., Lancrenon S., Akiskal HS. Risk factors associated with lifetime suicide attempts in bipolar I patients: findings from a French National Cohort, Compr Psychiatry 50(2): 115-20 (2009)

11) Ayuso-Gutierrez J.L., Ramos-Brieva J.A.: The course of manic-depressive illness. A comparative study of bipolar I and bipolar II patients, J Affect Disord 4 : 9-14 (1982)

12) Balazs J., Lecrubier Y., Csiszer N., Kosztak J., Bitter I. :Prevalence and comorbidity of affective disorders in persons making suicide attempts in Hungary : importance of the first depressive episodes and of bipolar II diagnoses : research report, J Affect Disord 76: 113-119 (2003)

13) Baldessarini R.J., Jamison K.R. Summary and conclusions: effects of medical interventions on suicidal behaviour. J Clin Psychiatry 60: 117-122 (1999)

14) Bebbington P., Ramana R. The epidemiology of bipolar affective disorder. Soc Psychiatry Epidemiol 30: 279-292 (1995)

15) Benazzi F.: Prevalence of bipolar II disorder in outpatient depression: a 203-case study in private practice, J Affect Disord 43: 163-166 (1997)

16) Blanco C., Laje G., Olfson M., Marcus S.C., Pincus H.A. Trends in the treatment of bipolar disorder by outpatient psychiatrists Am J Psychiatry 159(6):1005-10 (2002)

17) Bowden C.L. A different depression: clinical distinctions between bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord 84:117-125 (2005)

18) Bowden C.L. New concepts in mood in mood stabilization: evidence for the effectiveness of valproate and lamotrigine. Neuropsychopharmachology 19: 194-199 (1998)

19) Bowen R., South M., Hawkes J. Mood swings in patients with panic disorder. Can J Psychiatry 39: 91-94 (1994)

20) Boylan K.R., Bieling P.J., Marriott M., Begin H., Young L.T., MacQueen G.M. Impact of comorbidity anxiety disorders on outcome in a cohort of patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 65: 1106-13 (2004) 21) Calabrese J.R., Rapport D.J. Mood stabilizers and the evolution of maintenance study designs in bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 60: 5-13 (1999)

22) Cassano G.B., Pini S., Saettoni M., & Dell’Osso L. Multiple anxiety disorder comorbidity in patients with mood spectrum disorders with psychotic features. American Journal of Psichiatry 156(3): 474-476 (1999)

23) Cassano G.B., Musetti L., Perugi G., Mignani V., Soriani A., McNair D.M., Akiskal H.S. Major Depression subcategories. Their potentiality for clinical research. In Diagnosis and Treatment Depression. Paper presented at “Quo vadis?” Symposium. Sanofi Group May 11-12, Montpelier, France (1987)

24) Cassidy F., Ahearn E., Carroll BJ. A prospective study of inter-episode consistency of manic and mixed subtypes of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 67:181-185 (2001)

25) Cassidy F., Murry E., Forest K., Carroll B.J. Signs and symptoms of mania in pure and mixed episodes J. Affect Disord. 50:187-201 (1998a)

26) Cassidy F., Murry E., Forest K., Carroll B.J. A factor analysis of the signs and symptoms of mania Arch Gen Psychiatry. 55:27-32 (1998b)

27) Chen C.N., Dilsaver S.C.: Comorbidity of panic-disorder in bipolar illness: evidence from the Epidemiological Catchment Area Survey, Am J Psychiatry 152: 280-282 (1995a)

28) Chen C.N., Dilsaver S.C.: Comorbidity for obsessive-compulsive disorder in bipolar and unipolar disorders. Psychiatry Res 59: 57-64 (1995b) 29) Coryell W., Keller M.B., Endicott J., Andreasen N., Clayton P., Hirschfeld R.M.A.: Bipolar II illness: course and outcome over a five-year period, Psychol Med 19 : 129-141 (1989)

30) Coryell W., Endicott J., Andreasen N., Keller M.: Bipolar I, bipolar II and nonbipolar major depression among the relatives of affectively ill probands, Am J Psychiatry 142: 817-821 (1985)

31) Coryell W., Endicott J., Reich T., Andreasen N., Keller M.B.: A family study of bipolar II disorder, Br J Psychiatry 145: 49-54 (1984)

32) Das A.K., Olfson M., Gameroff M.J., Pilowsky D. J., Blanco C., Feder A., Gross R., Neria Y., Lantigua R., Shea S., Weissman M.M. Screening for Bipolar Disorder in a Primary Care Practice. JAMA 293(8):956-963 (2009) 33) Depp C. A., Davis C. E., Mittal D., et al. Health-related quality of life and functioning of middle-aged and elderly adults with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psichiatry 67: 215-221 (2006)

34) Dilsaver S.C., Chen Y.W., Swann A.C., et al. Suicidality, panic disorder and psychosis in bipolar depression, depressive-mania and pure-mania. Psychiatry Res 73: 47-56 (1997)

35) Dilsaver S.C.,Akiskal H.S., Akiskal K.K., Benazzi F. Dose response relationship between number of comorbid anxiety disorders in adolescent bipolar/unipolar disorders, and psychosis, suicidality, substance abuse and familiarity. J Affect Disord 96:249-258 (2006)

36) Dittmann S., Biedermann N.C., Grunze H. et al The Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network: results of the naturalistic follow-up study after 2.5 years of follow-up in German centres. Neuropsychobiology 46 (suppl 1): 2-9 (2002)

37) Dunner D.L.: A review of the diagnostic status of “bipolar II” for the DSM-IV Work Group on Mood Disorders, Depression 1: 2-10 (1993)

38) Endicott J., Nee J., Andreasen N., Clayton P., Keller M., Coryell W. : Bipolar II. Combine or keep separate?, J Affect Disord 8: 17-28 (1985)

39) Engstrom C., Brandstrom S., Sigvardsson S., Cloninger C.R. & Nylander P.O. Bipolar disorder.III. Harm avoidance a risk factor for suicide attempts. Bipolar Disorder 6(2): 130-138 (2004)

40) Fagiolini A., Frank E., Scott J.A., et al. Metabolic syndrome in bipolar disorder: findings from the Bipolar Disorder Center for Pennsylvanians. Bipolar disorder 7: 424-30 (2005)

41) Fawcett J., Scheftner W.A,, Fogg L., Clark D.C., Young M.A., Hedeker D. et al. Time-related predictors of suicide in major affective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 147(9): 1189-1194 (1990)

42) Feske U., Frank E., Mallinger A.G., Houck P.R., Fagiolini A., Shear M.K. et al. Anxiety as a correlate of response to the acute treatment of bipolar I disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 157(6): 956-962 (2000)

43) Fieve R.R., Go R., Dunner D.L. et al.: Search for biological/genetic markers in a long-term epidemiological and morbid risk study of affective disorders, J Psychiatry Res 18: 425-445 (1984)

44) First M.B., Spitzer R.L., Gibbon M.,Williams J.B.W. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research version, Patient

Edition (SCID-I/P). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1994

45) Forty L, Jones I., Caesar S., Fraser C., Gordon-Smith K., Hyde S., Craddock N. Polarity at illness onset in bipolar I disorder and clinical course of illness. Bipolar Disorder 11:82-88 (2009)

46) Forty L., Smith D., Jones I., Caesar S., Cooper C., Fraser C., Gordon-Smith K., Hyde S., Farmer A., McGuffin P., Craddock N. Clinical differences between bipolar and unipolar depression. The British J of Psych 192:388-389 (2008)

47) Frank E., Cyranowski J.M., Rucci P., et al. Clinical significance of lifetime panic spectrum symptoms in the treatment of patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psichiatry 59: 905-911 (2002)

48) Galfalvy H., Oquendo M.A., Carballo J.J. et al. Clinical predictors of suicidal acts after major depression in bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Bipolar Disorder 8: 586-595 (2006)

49) Gastó C., Manίa, In: Vallego J., Gastó C (eds): Trastornos afectivos: ansiedad y depresión. Barcelona, Spain: Salvat: 265-282 (1990)

50) Gaudiano BA., Miller JW. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in Bipolar I Disorder: relationship to depression severity and treatment outcome.Depress Anxiety 21:71-7 (2005)

51) Ghaemi S.N., Boiman E.E., Goodwin F.K. Diagnosing bipolar disorder and the effect of antidepressants: a naturalistic study. J Clin Psychiatry 61: 804-808 (2000)

52) Ghaemi S.N., Hsu D.J., Thase M.E., et al. Pharmacological treatment patterns at study entry for the first 500 STEP-BD participants. Psych Serv 57: 660-665. (2006)

53) Gershon E.S., Hamovit J., Guroff J.J., Dibble E., Leckman J.F., Sceery W., Targum S.D., Nurnberger J.I., Goldin L.R., Bunney W.E.: A family study of schizoaffective, bipolar I, bipolar II, unipolar, and normal control probands, Arch Gen Psychiatry 39: 1157-1167 (1982)

54) Gold J.H. Gender differences in psychiatric illness and treatments: a critical review. J Nerv Ment Dis 186: 769-775 (1998)

55) Goodwin R.D., Hoven C.W. Bipolar-panic comorbidity in the general population: prevalence and associated morbidity. J Affect Disord 70: 27-33 (2002)

56) Goodwin R.D., Stayner D.A., Chinman M.J., Wu P., Tebes J.K., Davidson L. The relationship between anxiety and substance use disorder among individuals with severe affective disorders. Compr Psychiatry 43: 245-52. (2002)

57) Hadjipavlou G, Mok H., Yatham L. N. Pharmacotherapy of bipolar II disorder: a critical review of current evidence. Bipolar Disorder 6:14-25 (2004)

58) Hawton K. et al. Suicide and attempted suicide in bipolar disorder: a systematic review of risk factors. J Clin Psychiatry 66(6):693-704 (2005)

59) Henry C., Bulke D., Bellivier F., Etain B., Rouillon F., Leboyer M. Anxiety disorders in 318 bipolar patients: prevalence and impact on illness severity and response to mood-stabilizers. J Clin Psychiatry 64: 331-5 (2003) 60) Heun R., Maier W. :The distinction of bipolar II disorder from bipolar I and recurrent unipolar depression: results of a controlled family study, Acta Psychiatr Scand 87: 279-284 (1993)

61) Hirschfeld R.M., Vornik, L.A. Recognition and diagnosis of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry; 65 (Suppl 15), 5-9 (2004)

62) Hirschfeld R.M. Bipolar Depression: the real challenge. Eur Neuropsy chopharmacol 14 (suppl 2): S83-8 (2004)

63) Hirschfeld R.M., Weisler R.H., Raines S.R., Macfadden W; for the BOLDER Study Group. Quetiapine in the treatment of anxiety in patients with bipolar I or II depression: a secondary analysis from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry: 67(3):355-62. (2006)

64) Joffe R.T., MacQueen G.M., Marriott M., Young L.T.: A prospective, longitudinal study of percentage of time spent ill in patients with bipolar I or bipolar II disorders, Bipolar Disorder; 6: 62-66 (2004)

65) Johnson J., Weissman MM., Klerman GL. Panic disorder, comorbidity, and suicide attempts. Arch Gen Psychiatry 47:805-808 (1990) 66) Judd L.L., Akiskal H.S., Schettler P.J., Endicott J., Maser J., Solomon D.A., Leon A.C., Rice J.A., Keller M.B.: The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder, Arch Gen Psychiatry 59: 530-537 (2002)

67) Judd L. L., Akiskal H. S., Schettler P. J., Coryell W., Maser J., Rice J. A., Solomon D. A., Keller M. B. : The comparative clinical phenotype and long term longitudinal episode course of bipolar I and II : a clinical spectrum or distinct disorders?:, J Affect Disord 73 : 19-32 (2003)

68) Judd L.L., Schettler P.J., Akiskal H.S et al. Long-term symptomatic status of bipolar I versus bipolar II disorders. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 6: 127-137 (2003)

69) Judd L.L., Akiskal H.S., Schettler P.J., Coryell W., Endicott J., Maser J.D., Solomon D.A., Leon A.C., Keller M.B.: A Prospective Investigation of the Natural History of the Long-term Weekly Symptomatic Status of Bipolar II Disorder, Arch Gen Psychiatry 60: 261-269 (2003)

70) Judd L.L., Akiskal H.S., Schettler P.J. et al. Psychosocial disability in the course of bipolar I and II disorders. A prospective, comparative, longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62: 1322-1330 (2005)

71) Keck Jr P.E., Calabrese J.R., McQuade R.D., Carson W.H., Carlson B.X., Rollin L.M. et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 26-weeks trial of aripiprazole in recently manic patients with bipolar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 67: 626-37 (2006)

72) Keller M.B., Lavori P.W., Friedman B., Nielsen E., Endicott J., McDonald-Scott P., Andreasen N.C.: The longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation. A comprehensive method for assessing outcome in prospective longitudinal studies, Arch Gen Psychiatry 44 (6): 540-548 (1987)

73) Kessler R.C., Rubinow D.R., Holmes C., Abelson J.M., Zhao S. The epidemiology of DSM-III-R bipolar I disorder in a general population survey. Psychological Med 27: 1079-1089 (1997)

74) Kessler R.C., McGonagle K.A., Zhao S.: Lifetime and 12-months prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey, Arch Gen Psychiatry 51: 8-19 (1994) 75) Lepine JP, Chignon JM, Teherani M. Suicide attempts in patients with panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 50:144-149 (1993)

76) Leverich GS, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, Suppes T, et al. Risk of switch in mood polarity to hypomania or mania in patients with bipolar depression during acute and continuation trials of venlafaxine, sertraline, and bupropion as adjuncts to mood stabilizers. Am J Psychiatry 163: 232-9. (2006)

77) Lòpez-Muňoz F., Vieta E., Rubio G., Garcia-Garcia P., Alamo C. Bipolar disorder as an emerging pathology in the scientific literature: a bibliometric approach. J Affect Disorder 92: 161-70 (2006)

78) MacKinnon D. F., Zamoiski R. Panic comorbidity with bipolar disorder: what is the manic-panic connection? Bipolar Disorder 8: 648-664 (2006)

79) MacQueen G.M., Marriott M., Begin H., Robb J., Joffe R.T., Young L.T.: Subsyndromal symptoms assessed in longitudinal, prospective follow-up of a cohort of patients with bipolar disorder, Bipolar Disorder 5:349-355 (2003) 80) Maina G, Albert U, Rosso G, Bogetto F. Olanzapine or lamotrigine addition to lithium in remitted bipolar disorder patients with anxiety disorder comorbidity: a randomized, single-blind, pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 69(4):609-16 (2008)

81) Mantere O., Suominen K., Arvilommi P., Valtonen H., Leppämäki S., Isometsä E. Clinical predictors of unrecognized bipolar I and II disorders. Bipolar Disorder 10: 238-244 (2008)

82) Mantere O., Suominen K., Leppämäki S., Valtonen H., Arvilommi P., Isometsä E. The clinical characteristics of DSM-IV bipolar I and II disorders: baseline findings from the Jorvi Bipolar Study (JoBS). Bipolar Disord 6(5): 395-405 (2004)

83) McElroy S.L., Altshuler L.L., Suppes T., Keck P.E., Frye M.A., Denicoff K.D.: Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder, Am J Psychiatry 158: 420-426 (2001)

84) Menchón J.M., Gastó C., Vallejo J., Catalán R., Otero A., Vieta E. Rate and significance of hypomanic switches in unipolar melancholic depression. Eur Psychiatry 8: 125-129 (1993)

85) Merikangas, K. R., Akiskal H. S:, Angst J., Greenberg P.E., Hirschfeld R. M., Petukhova M., Kessler R. C. Lifetime and 12-month

prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64: 543-552 (2007)

86) Mitchell P.B., Malhi G.S. Bipolar depression: phenomenological overview and clinical characteristics. Bipolar Disorder 6: 530-9 (2004)

87) Mitchell P.B., Slade T., Andrews G. Twelve-month prevalence and disability of DSM-IV bipolar I disorder in an Australian general population survey. Psychol Med 34: 777-85 (2004)

88) Mitchell P., Parker G., Jamieson K., Wilheim K., Brodaty H., Hadzi-Pavlovic D., Roy K. Are there any differences between bipolar and unipolar melancholia? J Aff Disord 25(2): 97-105 (1992)

89) Murray C.J., Lopez A.D. Regional patterns of disability-free life expectancy and disability-adjusted life expectancy: global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 349: 1347-52 (1997)

90) Mury M., Verdoux H., Bourgeois M.: Comorbidite trouble bipolaire et trouble des conduites alimentaires. Aspects epidemiologiques et therapeutiques, Encephale 21 : 545-553 (1995)

91) Nolen W.A., Luckenbaugh D.A., Altshuler L.L. et al. Correlates of 1-year prospective outcome in bipolar disorder: results from the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Network. Am J Psychiatry 161: 1447-1454 (2004)

92) Olfson M., Marcus S.C., Druss B., et al. National trends in the outpatient treatment. JAMA 287: 203-209 (2002)

93) Perlis R.H., Delbello M.P., Miyahara S., Wisniewski S.R., Sachs G.S., Nierenberg A. A. Revisiting Depressive-Prone Bipolar Disorder: Polarity of Initial Mood Episode and Disease Course Among Bipolar I Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder Participants. Biol Psychiatry 58:549-553 (2005)

94) Perugi G., Micheli C., Akiskal H.S., Madaro D., Socci C., Quilici C., Musetti L. Polarity of the first episode, clinical characteristics, and course of manic depressive illness: a systematic retrospective investigation of 320 bipolar I patients. Compr Psych 41(1):13-18 (2000)

95) Perugi G., Akiskal H.S., Ramacciotti S., Nassini S., Toni C., Milanfranchi A., Musetti L. Depressive comorbidity of panic, social phobia and obsessive-compulsive disorders re-examined is there a bipolar II connection?. J Psichiatr Res 33: 53-61 (1999)

96) Perugi G., Akiskal H.S., Lattanzi L., Cecconi D., Mastrocinque C., Patronelli A., et al.: The high prevalence of soft bipolar (II) features in atypical depression, Compr Psychiatry 1998;39:63-71

97) Pini S., Cassano G.B., Simonini E., Savino M., Russo A., Montgomery S.A.: Prevalence of anxiety disorders comorbidity in bipolar depression, unipolar depression and dysthymia, J Affect Disord 42: 145-153 (1997)

98) Pini S., Dell’Osso L., Mastrocinque C., Marcacci G., Papasogli A., Vignoli., S. et al. Axis I comorbidity in bipolar disorder with psychotic features. British Journal of Psychiatry 175:467-71 (1999)

99) Post R.M., Rubinow D.R., Uhde T.W. Roy-Byrne P.P., Linnoila M., Rosoff A., Cowdry R. Dysphoric mania: clinical and biological correlates. Arch Gen Psychiatry 46: 353-358 (1989)

100) Post R. M., Denicoff K.D., Leverich G.S. et al. Morbidity in 258 bipolar outpatients followed for 1 year with daily prospective ratings on the NIMH life chart method. J Clin Psychiatry 64: 680-690; quiz 738-739 (2003)

101) Post R. M. The impact of bipolar depression. J Clin Psichiatry 66 (Suppl 5): 5-10 (2005)

102) Regier D.A., Farmer M.E., Rae D.S.: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study, J Am Med Assoc 264: 2511-2518 (1990)

103) Rihmer Z., Gonda X., Tondo L. Lithium and suicidal behavior in patients with bipolar disorder, J Clin Psychiatry 69(6): 916-22 (2008)

104) Rihmer Z., Szadoczky E., Furedi J., Kiss K., Papp Z.: Anxiety disorders comorbidity in bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar major depression: results from a population-based study in Hungary, J Affect Disord 67: 175-179 (2001)

105) Rihmer Z., Pestality P. : Bipolar II disorder and suicidal behaviour, Psychiatr Clin North Am 22 (3): 667-673 (1999)

106) Robins L.N., Regier D.A. (Eds). Psychiatric disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. The Free Press, New York (1991) 107) Sachs G.S., Printz D.J., Kahn D.A., Carpenter D., Docherty J.P. The expert consensus guidelines series: medication treatment of bipolar disorder. Postgrad. Med. (special issue): 1-104 (2000)

108) Sanger T.M., Grundy S.L., Gibson P.J., Namjoshi M.A., Greaney M.G., Tohen M.F. Long-term olanzapine therapy in the treatment of bipolar I disorder: an open-label continuation phase study. J Clin Psychiatry 62: 273-81 (2001)

109) Savas H.A., Yumru M., Ozen M.E. Use of long acting risperidone in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol 26: 530-1 (2006)

110) Savino M., Perugi G., Simonini E., Soriani A., Cassano G.B., Akiskal H.S.: Affective comorbidity in panic disorder: is there a bipolar connection?, J Affect Disord 28: 155-163 (1993)

111) Schǚrhoff F., Bellivier F., Jouvent R., Mouren-Simeoni MC., Bouvard M., Allilaire JF., et al. Early and late onset bipolar disorders: two different forms of manic-depressive illness. Journal of Affecti Disord 58: 215-21(2000) 112) Simon N.M., Pollack M.H., Ostacher M.J., Zalta A.K., Chow C.W., Fischmann D., et al. Understanding the link between anxiety symptoms and suicidal ideation and behaviours in outpatients with bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 97(1-3): 91-99 (2007)

113) Simon N.M., Zalta A.K., Otto M.W., Ostacher M.J., Fischmann D., Chow C.W., Thompson E.H., Stevens J.C., Demopulos C.M., Nierenberg A., Pollack M.H. The association of comorbid anxiety disorders with suicidal ideation in outpatients with bipolar disorder. Journal of Psych Research 41: 255-264 (2007)

114) Simon N.M., Otto M.W., Wisniewski S.R., Fossey M., Sagduyu K., Frank E. et al. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: Data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). American Journal of Psychiatry 16(12): 2222-2229 (2004)

115) Simpson S.G., Folstein S.E., Meyers D.A.: Bipolar II: The most common bipolar phenotype?, Am J Psychiatry 150: 901-903 (1993)

116) Sonne SC., Brady KT., Morton WA. Substance abuse and bipolar affective disorder.J Nerv Ment Dis 182(6):349-52 (1994)

117) Suppes T., Kelly D.I., Perla J.M. Challenges in the management of bipolar depression J Clin Psychiatry 66 (suppl 5):11-6 (2005)

118) Suominen K., Mantere O., Valtonen H., Arvilommi P., Leppämäki S., Paunio T., Isometsä E. Early age at onset of bipolar disorder is associated

with more severe clinical features but delayed treatment seeking. Bipolar Disorder 9:698-705 (2007)

119) Szadoczky E., Papp Z., Vitrai J., Rihmer Z., Fiirdei J. The prevalence of major depressive and bipolar disorders in Hungary. Results from a National Epidemiologic Survey, J Affect Disord: 153-162 (1998)

120) Swann A.C., Bowden C.L., Morris D. et al. Depression during mania: treatment response to lithium or divalproex. Arch Gen Psychiatry 54:37-42 (2007)

121) Tamada RS, Issler CK, Amaral JA, Sachs GS, Lafer B. Treatment-emergent affevtive switch: a controlled study. Bipolar Disord 6(4):333-7.(2004) 122) Tohen M., Calabrese J., Vieta E., Bowden C., Pinto A.,Lin D., Xu W., Corya S. Effect of comorbid anxiety on tretament response in bipolar depression. J Affect Disord 104:137-146 (2007)

123) Tohen M., Zarate Jr C.A., Hennen J et al. The McLean-Harvard First-Episode Mania Study: prediction of recovery and first recurrence. Am J Psychiatry 160: 2099-2107 (2003)

124) Tohen M, Calabrese J, Vieta E, Bowden C, Gonzalez-Pinto A, Lin D, Xu W, Corya S. Effect of comorbid anxiety on treatment response in bipolar depression. J Affect Disord;104(1-3):137-46. Epub (2007)

125) Tondo L., Baldessarini R.J., Hennen J., Floris G. Lithium maintenance treatment of depression and mania in bipolar I and bipolar II disorders, Am J Psychiatry 155: 638-645 (1998)

126) Tondo L., Baldessarini R.J., Hennen J., Floris G., Silvetti F.,Tohen M. Lithium treatment and risk of suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry 59: 405-414 (1998)

127) Toni C., Perugi G.,Frare F., Tusini G., Fountolakis K.N., Akiskal K.K., Akiskal H. The clinical-familial correlates and naturalistic outcome of panic-disorder-agoraphobia with and without lifetime bipolar II comorbidity. Annals of General Psychiatry 7:1-8 (2008)

128) Toniolo RA, Caetano SC, Da Silva PV, Lafer B. Clinical significance of lifetime panic disorder in the course of bipolar disorder type I. Compr Psychiatry 50:9-12 (2009)

129) Vieta E., Brugue E., Goikolea J.M., Sanchez-Moreno J., et al. Acute and continuation risperidone monotherapy in mania. Hum Psychopharmachol 19: 41-5 (2004a)

130) Vieta E., Calabrese J.R., Hennen J, Colom F., Martinez-Aran, Sanchez-Moreno J. et al. Comparison of rapid-cycling and non-rapid-cycling bipolar I manic patients during treatment with olanzapine: analysis of pooled data. J Clin Psychiatry 65: 1420-8 (2004b)

131) Vieta E., Colom F., Corbella B., Martinez-Arán A., Reinares M., Benabarre A., Gastó C.: Clinical correlates of psychiatric comorbidity in bipolar I patients, Bipolar Disorder; 3: 253-258 (2001)

132) Vieta E., Gasto C., Otero A., Nieto E., Vallejo J.: Differential features between bipolar I and bipolar II disorder, Compr Psychiatry 38 : 98-101 (1997) 133) Valtonen H.M., Suominen K., Mantere O., Leppämäki S., Arvilommi P., Isometsä E.T. Prospective study of risk factors for attempted suicide among patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorder 8: 576-585 (2006) 134) Viguera A.C., Baldessarini R.J., Tondo L. Response to lithium maintenance treatment in bipolar disorders: comparison of women and men. Bipolar Disorder 3: 245-252 (2001)

135) Wang P.W., Ketter T.A., Becker O.V., Nowakowska C. New anticonvulsant medication uses in bipolar disorder. CNS Spectr 8: 941-7 (2003)

136) Wehr T.A., Goodwin F.K.: Can antidepressants cause mania and worsen the course of affective illness?, Am J Psychiatry 144: 1403-1411 (1987)

137) Wehr T.A., Sack D.A.,Rosenthal N.E., Cowdry R.W. Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. Am J Pssychiatry 145: 179-184 (1988)

138) Yatham L.N., Paulsson B., Mullen J., Vagero A.M. Quetiapine versus placebo in combination with lithium or divalproex for the treatment of bipolar mania. J Clin Psychopharmacol 24: 599-606 (2004)

139) Young L.T., Cooke R.G., Robb J. C., Levitt A.J., & Joffe R.T. Anxious and non-anxious bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective disorders 29(1): 49-52 (1993)

6. TABLES

Table 1. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of 194 patients with bipolar disorder, type I and II

*Mann-Whitney U test

Bipolar I Bipolar II Total Significance

N % N % N % χ2 p

123 63.4 71 36.6 194 100

Male gender 42 34.2 20 28.2 62 32.0 .74 .39

Married 50 40.7 31 43.7 81 41.8 .17 .68

More than 8 yrs of education

38 30.9 22 31.0 60 30.9 .00 .99

Employed 59 48.0 31 43.7 90 46.4 .34 .56

Depressive onset (N=179) 72 65.5 64 92.8 136 76.0 17.31 .000

Polarity of index episode

Depressive 44 35.8 57 80.3 101 52.1 32.9 .000

Manic 23 18.7 - - - -

Hypomanic - - 4 5.6 - - - -

Mixed 29 23.6 - - - -

Remission 27 22.0 10 14.1 37 19.1 1.80 0.18

Polyphasic index episode 13 10.6 4 5.6 17 8.8 1.37 .30*

Patients with lifetime suicidal attempts

25 30.9 16 29.1 41 30.2 .049 .83

Psychotic features at intake

47 47.5 7 10.5 54 32.5 25.0 .000

Family history of mood disorder

49 49.5 40 61.5 89 54.3 2.29 .13

M Sd M Sd M Sd z/t p

Age at intake (yrs) 39.4 13.1 41.6 13.9 40.2 13.4 1.11 .27

Age of onset (yrs) 25.8 10.2 29.9 13.1 27.4 11.5 2.30 .022

Length of illness (yrs) 12.9 10.1 11.7 10.5 12.4 10.3 -1.11 .27*

Previous episodes 10.0 22.1 9.6 11.5 9.8 18.7 .55 .58* Depressive episodes 4.7 10.4 5.6 5.8 5.0 9.0 2.68 .0074* Hospitalizations 2.0 2.5 1.3 1.4 1.7 2.2 -1.98 .048* Number of previous suicidal attempts 0.5 0.9 0.5 0.9 0.5 0.9 .03 .98*