UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI SASSARI

CORSO DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN SCIENZE BIOMEDICHE Coordinatore del Corso: Prof. Andrea Fausto Piana

CURRICULUM IN ODONTOSTOMATOLOGIA ESTETICA ADESIVA E PREVENTIVA

Responsabile di Curriculum: Prof.ssa Egle Patrizia Milia

XXXI CICLO

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT

AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES

AMONG CHILDREN’S AND ADULT’S

CARIES PROFILES

Coordinatore:

Prof. Andrea Fausto Piana

Tutor: Tesi di dottorato di:

Prof. Guglielmo Campus Dott.ssa Mariantonietta Arrica

To my family and friends,

who taught me the meaning of life.

To my beloved teachers,

who taught me the meaning of education

and love for research.

To my students,

who taught me how to teach.

Preface 2 ABSTRACT 3 GENERAL INTRODUCTION 5 References: 7 PAPER I 9 Introduction 10

Materials and methods 11

Results 14

Discussion 16

References 19

PAPER II 31

Introduction 32

Material and methods 33

Results: 38

Discussion: 39

References 42

PAPER III 51

Introduction 52

Material and methods 54

Results: 57

Discussion: 58

References 61

Preface

This Ph.D thesis has been reported in an unconventional format. As an alternative to the traditional thesis layout, a Journal Manuscript-Style was preferred. The whole dissertation has been developed around three main papers, related to the common theme of social/behavioral gradients and perinatal circumstances among children’s and adults’ caries profiles.

Due to the selected format and the shared study population for Paper II and Paper III, some redundancies in the text can be found.

Paper I has been already submitted and published. Original editorial format is reported in the specific session at the bottom of the thesis.

Other publications occurred during the Ph.D Course are there reported even if not directly related to this Ph.D principal interest.

ABSTRACT

The overall aim of this thesis was to focus on social/behavioral adult’s patterns and perinatal mothers’ characteristics that may influence children’s caries risk framing, and its mechanisms of transmission.

The specific aims of this thesis were:

• to explore the potential presence of a social/behavioural gradient in dental health among Italian adults (Paper I)

• to explore the potential presence of a social/behavioural gradient in dental health among Italian toddlers (Paper II)

• to investigate a potential association among perinatal conditions such as the mode of delivery, Apgar index, gestational week, birth weight, AB0 blood group and early childhood caries in Italian toddlers (Paper III)

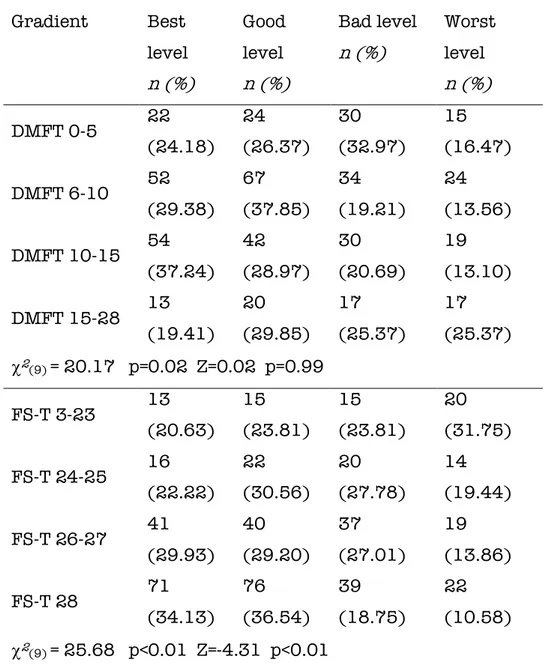

Caries indices and a structured self-compiled questionnaire on social and behavioral factors administered were registered on 480 subjects (30-45 year old), 52.9% males and 47.1% females. A social/behavioral gradient was generated as the sum of the worst circumstances recorded by the questionnaire (Paper I). Caries figures (DMFT) were statistically significantly associated to gender, occupational status, frequency of tooth brushing and smoking. The number of Filled-Sound-Teeth (FS-T) was higher in females (p=0.03). FS-T was also statistically significant associated to smoking habits (p<0.01). DMFT and FS-T played a statistically significantly role on the social/behavioral gradient (c2(9)=20.17 p=0.02 Z=0.02 p=0.99 and c2(9)=25.68 p<0.01 Z=-4.31 respectively).

The same approach was translated and applied to a population of 751 3-5 year old children. A social/behavioural gradient was shown to be confirmed also in childhood. When cross checking social/behavioural determinants with perinatal and maternal health risk factors (mode of delivery, gestational age, apgar index, body max index at early pregnancy, AB0 blood groups), no significant associations were found and the social/behavioural factors showed to be the predominant responsible of early childhood caries patterns.

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

Dental caries is still a significant oral health problem worldwide affecting indiscriminately both children and adults. It is a multifactorial disease starting with microbiological shifts within the complex oral biofilm (dental plaque). International literature has been proving that caries is affected by the consumption of dietary sugars, salivary flow, exposure to fluoride and preventive behaviors [Selwitz et al, 2007].

During the past decades the common consensus from many reports worldwide was that dental caries had declined significantly and was continuing to decline in populations. The dental community has prided itself on efforts that have reduced dental caries including use of systemic and topical fluorides, toothpastes, sealants, improvements in diet, oral health education and dental care. [Marthaler, 2004; Downer et al, 2005, Bragramian et al, 2009].

However, among pre-school children, it has been shown that the tendency towards caries decline has not been increased during the last 30 years [Hugoson et al, 1986, 1995, 2005; Stecksén-Blicks et al, 2004]. Moreover, although children are the primary recipients of caries prevention programs in the Western world, dental caries is still one of the primary causes of tooth loss among adults. [Fure, 2003]

Furthermore, there is a trend in many developed countries for the prevalence of dental caries to rise again, especially among young children [Haugejorden & Birkeland, 2002]. As a result, dental caries is still common among children and adolescents [Nithila et al, 1998; Marthaler, 2004; ] and affects 46% of 4- year-old children [Stecksén-Blicks et al, 2004] and 80% of 15-year-olds [Hugoson et al, 2008].

on the quality of life independently of their ages [Low et al, 1999; Filstrup et al, 2003; Ismail, 2004].

Dental caries continues to be a major health concern for populations worldwide with disparities related to well-known issues of socioeconomics, migration, lack of preventive efforts and dietary changes. New and renewed efforts must be marshaled together to focus on combating serious emerging increases in dental caries. Dentistry has the capability and resources to deal with this challenge and the time is now [Bagramian et al, 2009]. It is therefore of outmost importance to prevent the caries disease, but this will not be successful unless the available scientific knowledge relating to ways of understanding and possibly modifying the etiological factors of the disease is appropriately applied.

References:

1. Bagramian RA, Garcia-Godoy F, Volpe AR. The global increase in dental caries. A pending public health crisis. Am J Dent. 2009;22(1):3-8.

2. Downer MC, Drugan CS, Blinkhorn AS. Dental caries experience of British children in an international context. Community Dent Health. 2005;22(2):86-93.

3. Filstrup SL, Briskie D, da Fonseca M, Lawrence L, Wandera A, Inglehart MR. Early childhood caries and quality of life: child and parent perspectives. Pediatr Dent. 2003;25(5):431-40.

4. Fure S. Ten-year incidence of tooth loss and dental caries in elderly Swedish individuals. Caries Res. 2003;37(6):462-9.

5. Haugejorden O, Birkeland JM. Analysis of the ups and downs of caries experience among Norwegian children aged five years between 1997 and 2003. Acta Odontol Scand. 2005;63(2):115-22. 6. Hugoson A, Koch G, Bergendal T, Hallonsten AL, Laurell L, Lundgren D, et al. Oral health of individuals aged 3-80 years in Jonkoping, Sweden, in 1973 and 1983. II. A review of clinical and radiographic findings. Swed Dent J. 1986;10(5):175-94.

7. Hugoson A, Koch G, Bergendal T, Hallonsten AL, Slotte C, Thorstensson B, et al. Oral health of individuals aged 3-80 years in Jonkoping, Sweden in 1973, 1983, and 1993. II. Review of clinical and radiographic findings. Swed Dent J. 1995;19(6):243-60.

8. Hugoson A, Koch G, Gothberg C, Helkimo AN, Lundin SA, Norderyd O, et al. Oral health of individuals aged 3-80 years in Jonkoping, Sweden during 30 years (1973-2003). II. Review of clinical and radiographic findings. Swed Dent J. 2005;29(4):139-55.

Sweden, over a 30-year period (1973-2003). Int J Paediatr Dent. 2008;18(1):18-26.

10. Low W, Tan S, Schwartz S. The effect of severe caries on the quality of life in young children. Pediatr Dent. 1999;21(6):325-6. 11. Marthaler TM. Changes in dental caries 1953-2003. Caries Res.

2004;38(3):173-81.

12. Nithila A, Bourgeois D, Barmes DE, Murtomaa H. WHO Global Oral Data Bank, 1986-96: an overview of oral health surveys at 12 years of age. Bull World Health Organ. 1998;76(3):237-44.

13. Selwitz RH, Ismail AI, Pitts NB. Dental caries. Lancet. 2007;369(9555):51-9.

14. Stecksen-Blicks C, Rydberg A, Nyman L, Asplund S, Svanberg C. Dental caries experience in children with congenital heart disease: a case-control study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2004;14(2):94-100.

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 9

PAPER I

Does a social/behavioural gradient exist among Italian adults?

A cross sectional study?

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 10

Introduction

Several hypotheses have been formulated to describe social inequalities based on behavioral, environmental, psychological and material patterns. In diseases etiology apart the role of the social gradient also other several health behaviors are involved, postulating the existence of a social/behavioral gradient [Tsakos G et al, 2011; Golkari A et al, 2016]. Caries is the results of series of chain of events that probably have begun years earlier and social gradient determined by social class, educational level, occupational status and income is strictly associated with the clinical feature of the disease [Sanders A et al, 2006a; Sanders A et al. 2006]. Several health behaviors entered also in the casual caries chain like dietary, life-style and oral hygiene habits [Lingström P et al, 2003; Drury TF et al. 2000]

Several socioeconomic inequalities across a broad spectrum of oral status indicators reflective of unmet needs were described in a national sample of US adults and this topic was well reported in other later studies and associated to different markers of oral health [Locker D et al, 2000; ; Sabbah W et al, 2007; Sanders A et al, 2006]. Moreover, a graded inverse association between social inequalities and edentulousness in English adults was described [Golkari et al, 2016]. There was a social gradient in oral health that runs from top to bottom of the socioeconomic spectrum affecting indiscriminately also poorest adults. Besides the relationship between social gradient and caries in adults is not as strong as found for children, although there are relatively few studies on this topic [Costa SM et al, 2012; Reisine ST and Pstor W, 2001].

Analyses of oral health habits in a population is fundamental in order to correct oral health educational messages for the development of “good behaviors” [Zhu L et al, 2005].

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 11 In Italy, few surveys about oral health status in adults were conducted reporting a high caries experience level and correlating the oral status to inequalities, life-style habits and oral health behaviors [Sanders A et al, 2006a; Vano M et al, 2015; Carta G et al, 2015].

Basing on these forewords, the objective of this study among Italian adults was to explore the potential presence of a social/behavioral gradient in dental health. To elucidate this hypothesis, a cross-sectional study was designed and performed and a social/behavioral gradient generated.

Materials and methods

The present study was carried out in Sassari (Sardinia, Italy), under the supervision of the WHO Collaborating Centre for Epidemiology and Community Dentistry of Milan (Italy). From a starting population of 22,614 aged 30-45 years living in Sassari, once performed the power analysis G*Power 3.1.3 for Apple (logistic regression with an odds ratio of 1.5, an error probability of 0.04), a final sample size of 432 was estimated. Thanks to the collaboration of the municipal electoral register office, a letter explaining the purpose of the study and the informed consent were distributed to 5% (1131 subjects) of the 30-45 year old living in Sassari. Among them, 577 subjects (51.0%) agreed to participate; 82 (14.2%) did not attend the examination appointment and 15 (0.2%) did not complete the questionnaire. Overall 480 subjects, 52.9% males and 47.1% females, mean age 40.7±0.3, were examined (Figure 1). The study design was registered (2013_01_21_a) at the Sassari local office of the National Bioethics Committee and its results were reported following the STROBE guidelines for cross sectional studies [Vandernbroucke JP et al, 2007].

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 12

Records registration

One examiner (G. Carta) was calibrated, examining and re-examining 55 adults before the survey. Inter-examiner reliability was evaluated using fixed-effects analysis of variance in comparison with benchmark values (G. Campus). Intra-examiner reproducibility was assessed using Cohen’s kappa statistic [Castiglia P et al, 2007]. Good inter-examiner reliability was found for DMFT>0 (caries experience), with no significant difference from benchmark values (p=0.15) and a low mean square of error (0.47). Intra-examiner reliability was also high (Cohen’s Kappa statistic =0.88). The same examiner performed all dental examinations.

Subjects were examined in the Dental Institute of the University of Sassari, after professional oral hygiene, sitting on a dental chair, using a mouth mirror and a WHO Community Periodontal Index probe under optimal lighting. Teeth were dried before evaluation.

Following WHO indications, the DMFT index and the FS-T index were recorded [Schuller AA and Holst D, 2001].

Dental caries was recorded starting from the D3 dentinal lesion level [Pitts NB and Longbottom C, 1995]. The DMFT index was categorized and used as an ordinal score into three classes using as reference the categorization of DMFS created by Lesaffre and co-workers [Lesaffre E et al, 2004].

The FS-T index allowed assessing the number of filled and sound teeth and is a measure of functional status. Further, it presented an increased model performance and might be more effective than the DMFT to describe social demographic and behavioral factors associated with adults’ caries experience [Holtfreter B et al, 2013].

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 13 A structured self-compiled questionnaire was administered to participants before the clinical examination. To guarantee anonymity, the questionnaire was printed on one side of a sheet, while the clinical chart was on the other side. The questionnaire was pre-tested for reliability and validity [Campus G. et al, 2011]. It was highly structured and divided into three domains: (1) personal data (age, gender, educational level, employment categorization), (2) life-style behavior (smoking and dietary habits), (3) oral health behavior (tooth brushing, frequency of dental check-ups). Educational level was classified as: primary school, secondary school and university. Employment was categorized using the Italian National Institute for Statistics. Smoking habits were coded following the WHO definition for tobacco user modified by the authors as non-smoker and smoker if they had started to smoke more than 3 years earlier [Vandenbroucke JP et al, 2007].

Statistical Analyses

Data from the dental examination and questionnaire were entered in the FileMaker Pro 9.0 Runtime database and then exported to Excel® Microsoft spread sheet. All data were analyzed using the software STATA® (Mac version 13). For all analyses, the statistical significance level was set at α=0.05.

Descriptive statistics and cross-tabs were calculated between both caries experience (DMFT) and functioning teeth (FS-T) by questionnaire items. Then the variables derived from the questionnaire were dichotomized as follows: educational level, primary/secondary school vs university degree; occupational status, unemployed/housewife vs

technician/clerk/professional; dental attendance, pain/problem/every 2 years vs once a year/every 6-months. A multinomial logistic regression

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 14 models were performed using first, as dependent variable, the DMFT categorization scores and then the FS-T categorization records. The Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to measure the goodness of fit of the statistical model. The possible modifying effects of covariates on the outcomes were tested by an interaction model (likelihood ratio test statistic). Multicollinearity might sometimes cause problems with regression results. This problem was solved using the DFBETA command in STATA, excluding the information that had too much influence on the regression line. After the data elaboration, no statistically significant multicollinearity was observed. So it was decided to report findings without outliers.

A social/behavioral gradient was generated as the sum of the worst circumstances recorded by the questionnaire, regarding social inequalities and oral health behaviors. Subjects were stratified in four level of social gradient: “best”, with up to two worst results, “good”, “bad” and “worst”, respectively with three, four and five or more worst upshots. The association of the different caries risk categories and DMFT/FS-T was calculated. The nonparametric test for trend across ordered groups as an extension of the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was also calculated.

Results

Consistent differences regarding DMFT/components and social gradient (gender, occupational status, educational level) and oral health behaviors (smoking habits and frequency of dental attendance) were found (Table 1). The DMFT index was here statistically significant lower in males respect to females (9.11±5.12 and 11.09±5.06 respectively p<0.01). Caries figures were statistically significantly different across

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 15 occupational status despite gender, where the lowest categories showed the highest caries experience (p<0.01).

The mean number of missing teeth due to caries was statistically significantly associated to gender (p=0.04), smoking habit and educational level (both p<0.01).

A significant association between dental health and educational level to FS-T was found (Table 2). Highest educational levels presented always the best oral health status. Smoking played a threatening role against oral health: smokers showed the lowest percentages of sounds and filled teeth (5.62% FS-T 3-23, 5.21% FS-T 24-25, 7.92 FS-T 26-27 and 28). Ordinal logistic regressions were carried out to assess the association among categorized DMFT or FS-T scores, and social gradient or oral health behaviors (Table 3). In the first model caries prevalence (DMFT categorization) was used as dependent variable; gender (female) played a protective role in caries prevalence, as caries prevalence increased, the association between the two variables became stronger (p<0.01 except for DMFT 0-5 where p=0.05). An evident association was also showed between occupational status and caries, proving that low profile working categories corresponded to a greater caries experience. A strong association might be also noted between highest scores of DMFT and the frequency of tooth brushing; the acquired routine to brush teeth more than 2 times/day showed a protective role in mild and severe caries experience.

Categories 1 and 2 of FS-T (FS-T 3-23 and 24-25) were mildly associated to gender (p=0.03 and p=0.05, respectively), females had a better oral health status. The same categories showed also a statistical significant association with smoking habits (p<0.01 and p=0.02, respectively). As expected, the model presented a strong association between the

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 16 educational level and the oral health status, showing the best oral health related to the highest educational (p<0.01).

Table 4 displayed the new approach, which is clearly able to underline how both the worst social and behavioral levels could expose adults at a greater future risk for caries. Subjects reporting more than 5 worst results in their questionnaire (e.g. a cariogenic diet, smoking habit, lowest occupational profile, brushing teeth less than two times a day, lowest educational level and uneven dental attendance) showed the worst dental health condition. A statistically significant trend was observed regarding the FS-T scores and the worst social behavioral conditions (Z=-4.31, p<0.01).

Discussion

The purpose of this study performed on Italian (Sardinian) adults was to evaluate the presence of a social/behavioral gradient in dental health through a cross-sectional survey. Results confirm the hypothesis: a social/behavioral gradient associated to dental health in the study population was observed. Caries experience was almost ubiquitous and worst social and behavioral levels it seems expose adults at a greater future caries risk. Subjects reporting the worst results in questionnaire items (e.g. cariogenic diet, smoking habit, lowest occupational profile, brushing teeth less than two times a day, lowest educational level and uneven dental attendance) showed the worst dental health conditions. Moreover, Filled-Sound-Teeth index was statistically significant inversely associated to social/behavior gradient.

In the adult population examined, all figures of the caries process were presented and the picture underlines that the highest number of caries was detected in subjects with the worst social/behavior gradient and

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 17 conversely as the social/behavior gradient improves also the number of sound or restored teeth increases. At low social or behavioral level, the investigated sample showed poorer oral pattern conditions. This finding is partially reliable with those of other previous studies [Susin C et al, 2005; Eustaquio MV et al, 2010].

Social gradient occurs due to the social stratification in society, as all societies, rich developed or poor under-developed, edifice the life experiences, behaviors, and the advantages and disadvantages of its members, which tend to cluster by social group [Kosteniuk JG and Dickinson HD, 2003].

Several conceptualizations of the social determinants of oral health and the factors operating and interacting at multiple levels on it, have been well described in the international literature [Petersen PE]. However, there has been little translation of the conceptual frameworks into a tangible mechanism to drive decision-making in public health and dental services so far.

As the presence of a social/behavioral gradient in oral health among Italian adults was demonstrated, it might be used by community dentists to identify those subjects who are at a higher risk for future caries lesions.

Higher educational level was associated with better general health and studies of general health suggest that education affects health mainly by increasing an individual’s sense of control [Grembowski D et al, 2012]. Access to public dental care may weaken the social/behavior gradient in oral health through preventive and reparative mechanisms [Donaldson AN et al, 2008]. Oral health care system could be re-oriented to reduce inequalities in oral health through an evidence-based, public health approach.

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 18 The main limitation of the study is related to the design of the study; cross-sectional investigation did not allow to clarify the directionality of the association between the disease and the social/behavior gradient or the time frame of the exposures. Nevertheless, as social/behavior gradient plays a factor almost immutable, the association might be also investigated in cross-sectional studies, while causal factors might act in defined periods of subject’s life. All examined population presents a caries experience, showing the role acted during lifetime by social/behavior gradient in cooperation with casual factors. A further weak point is related to the continuous disease process and the timing or the exposure time was not considered in the analysis. The study findings are referred to adults living in a country like Italy, where the access to public dental service is quite limited, and findings may not be generalizable to other countries. The sample examined was quite large and representative of the study population of the same age range.

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 19

References

1) Tsakos G, Demakakos P, Breeze E, et al. Social Gradients in Oral Health

in Older Adults: findings from the English longitudinal survey of aging.

Am J Publi Health 2011; 101(10): 1892-1899

2) Golkari A, Sabokseir A, Sheiham A, et al. Socioeconomic gradients in

general and oral health of primary school children in Shiraz, Iran.

F1000Research 2016; 5: 767

3) Sanders A, Slade G, Turrel G, et al. The shape of the socioeconomic-oral

health gradient: implications for theoretical explanations. Community

Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2006 a;34(4),310-319

4) Sanders A, Spencer AJ and Slade GD. Evaluating the role of dental

behavior in oral health inequalities. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol

2006; 34(1): 71-79

5) Campus G, Cagetti MG, Senna A, et al. Does smoking increase risk for

caries? A cross-sectional study in an Italian military academy. Caries

Res 2011; 45: 40-46

6) Lingström P, Holm AK, Mejàre I, et al. Dietary factors in the prevention

of dental caries: a systematic review. Acta Odontol Scand 2003; 61:

331-340

7) Drury TF, Garcia I and Adesanya M. Socioeconomic Disparities in Adult

Oral Health in the United States. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999; 896: 322-324

8) Locker D. Deprivation and oral health: a review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28(3):161-169

9) Sabbah W, Tsakos G, Chandola T, et al. Social gradients in oral and

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 20 10) Costa SM, Martins CC, Bonfim Mde L, et al. A systematic review of

socioeconomic indicators and dental caries in adults. Int J Environ Res

Public Health 2012; 9: 3540-3574

11) Reisine ST and Psoter W. Socioeconomic status and selected behavioral

determinants as risk factors for dental caries. J Dent Educ. 2001

65:1009-1016

12) Zhu L, Petersen PE, Wang H, et al. Oral health knowledge, attitudes and

behavior of adults in China. International Dental Journal 2005; 55:

231-241

13) Vano M, Gennai S, Karapetsa D, et al. The influence of educational level and oral hygiene behaviors on DMFT index and CPITN index in an adult

Italian population: an epidemiological study. Int J Dent Hyg 2015; 13(2):

151-7

14) Carta G, Cagetti MG, Cocco F, et al. Braz oral res.Caries-risk profiles in

Italian adults using computer caries assessment system and ICDAS.

2015; 29(1): 1-8

15) Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE):

explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2007; 4(10): e297

16) Castiglia P, Campus G, Solinas G, et al. Children’s oral health in Italy: training and clinical calibration of examiners for the National Pathfinder

about caries disease. Oral Health Prev Dent 2007; 5: 255-261

17) Schuller AA and Holst D. Oral status indicators DMFT and FS-T:

reflections on index selection. Eur J Oral Sci 2001; 109: 155-159

18) Pitts NB and Longbottom C. Preventive Care Advised (PCA)/Operative

Care Advised (OCA)—categorising caries by the management option.

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 21 19) Lesaffre E, Mwalili SM and Declerck D. Analysis of caries experience

taking inter-observer bias and variability into account. J Dent res 2004;

83(12): 951-955

20) Holtfreter B, Berg MH, Kocher T, et al. Change in FS-T index in adults in

the German national oral health surveys between 1989 and 2005.

Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2013; 41: 251–260.

21) ISTAT Italian National Institute of Statistics. Nomenclatura e

classificazione delle unità professionali. Available at

http://cp2011.istat.it.

22) Susin C, Opperman RV, Haugejorden O, et al. Tooth loss and associated

risk indicators in an adult urban population from South Brazil. Acta

Odontol Scand 2005; 63(2): 85-93

23) Eustaquio MV, Montiel JM and Almerich JM. Oral health survey of the

adult population of the Valencia region (Spain). Med Oral Patol Oral Cir

Bucal 2010; 15(3): e538-44

24) Kosteniuk JG and Dickinson HD. Tracing the social gradient in the health

of Canadians: primary and secondary determinants. Soc Sci Med 2003;

57(2): 263-76.

25) Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003. Continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century - the approach of the

WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Available at

http://www.who.int/oral_health/media/en/orh_report03_en.pdf.

26) Grembowski D, Spiekerman C and Milgrom P. Social gradients in dental

health among low-income mothers and their young children. J Helth

Care Poor Underserved 2012; 23(2): 570-588

27) Donaldson AN, Everitt B, Newton T, et al. Effects of social class and dental

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 22

Figure 1. Flow chart of the study design

Caries scores Questionnaire

Data collection

22,614 subjects living in Sassari

(30-45 years)

480 subjects examined

(52.92% Males, 47.08 % Females)

Population object of the survey

Enrolment 5% sample (1131 subjects) Invited to participate 51.02% acceptance rate (577 subjects) Drop out

• 82 subjects did not attend the examination

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 23

Table 1. DMFT and components across social gradient (occupational

status, educational level) and oral health behaviors (smoking habits, brushing frequency and frequency of dental attendance) by gender. Only variables with at least one statistically significant differences with DMFT and/or components are reported.

DT (mean±S D) MT (mean±S D) FT (mean±S D) DMFT (mean±S D) Total sample 0.22±0.61 1.61±2.76 8.21±4.60 10.04±5.1 8 Males 0.22±0.46 1.45±2.57 7.44±4.51 9.11±5.12 Females 0.23±0.75 1.79±2.95 9.06±4.57 11.09±5.0 6 Anova one-way F=0.03 p=0.93 F=1.81 p=0.18 F=15.53 p<0.01 F=18.05 p<0.01 Occupational status Unemployed/house wife 0.28±0.78 2.46±3.41 9.74±3.98 12.47±4.6 5 Technician/clerk 0.19± 0.45 1.40±2.57 7.51±4.59 9.10±5.02 Professional 0.26±0.66 0.92±1.88 8.14±4.67 9.32± 5.00 Anova one-way F=0.97 p=0.44 F=2.98 p<0.01 F=1.47 p=0.08 F=2.52 p<0.01 Unemployed/house wife 0.28±0.78 2.46±3.41 9.73±3.99 12.47±4.6 5 Males 0.29±0.94 1.86±2.48 8.70±3.41 12.67±4.6 4

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 24

Females 0.24±1.02 3.05±3.44 10.51±4.2 3 13.44±4.9 3 Anova one-way F=0.02 p=0.89 F=3.21 p=0.08 F=15.53 p<0.01 F= 1.13 p=0.35 Professional 0.26±0.66 0.91±1.89 8.14±4.67 9.32±5.00 Males 0.22±0.46 0.38±1.09 7.34±4.46 7.94±4.78 Females 0.31±0.82 1.51±2.37 9.02±4.79 10.84±4.8 5 Anova one-way F=0.45 p=0.50 F=9.24 p<0.01 F=3.14 p=0.08 F= 1.77 p=0.04 Educational level Primary school 0.26±0.74 2.70±4.00 7.60±4.98 10.55±6.1 3 Secondary school 0.20±0.48 1.65±2.65 8.22±4.61 10.07±5.0 3 University degree 0.24±0.70 0.98±1.78 8.51±4.39 9.74±4.85 Anova one-way F=0.84 p=0.54 F=2.38 p<0.01 F= 1.68 p=0.03 F=1.30 p=0.15 Primary school Males 0.25±0.52 1.89±2.65 6.75±4.99 8.89±5.86 Females 0.26±1.00 3.94±5.27 8.88±4.76 4 13.09±5.7 2 Anova one-way F=2.19 p=0.08 F=1.01 p=0.45 F=2.61 p<0.01 F=1.59 p=0.08 Secondary school Males 0.25±0.47 1.77±3.03 7.27±4.51 9.29±5.12 Females 0.15±0.49 1.53±2.20 9.18±4.52 10.86±4.8 3

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 25

Anova one-way F=2.33 p=0.07 F=1.39 p=0.17 F=1.54 p=0.07 F=1.61 p=0.04 Smoking habits No smoking 0.18±0.48 1.20±1.98 8.18±4.66 9.56±4.97 Smoking 0.33±0.88 2.72±4.00 8.30±4.46 11.36±5.5 3 Anova one-way F= 2.87 p<0.01 F=3.88 p<0.01 F= 1.25 p=0.20 F= 2.33 p<0.01 No smokers Males 0.19±0.42 1.02±1.80 7.34±4.56 8.56±4.76 Females 0.30±0.55 2.59±3.73 7.69±4.38 10.59±5.7 5 Anova one-way F=1.75 p=0.16 F=1.11 p=0.35 F=2.12 p<0.01 F=1.86 p=0.01 Smokers Males 0.30±0.55 2.59±3.73 7.69± 4.38 10.59±5.7 5 Females 0.17±0.54 1.40± 2.16 9.10± 4.61 10.68±4.9 8 Anova one-way F= 2.59 p=0.01 F=1.05 p=0.41 F=0.83 p=0.65 F=1.35 p=0.15 Dental attendance Every 6-months 0.09±0.29 0.95±2.90 8.98±4.68 10.02±5.0 1 Once a year 0.11±0.37 1.31±1.85 8.21±4.16 9.63±4.56 Every 2 years 0.33±0.67 1.56±2.79 8.83±4.85 10.73±5.4 7 Pain/problem 0.31±0.83 2.27±3.38 7.34±4.75 9.92±5.64

Dr Mariantonietta Arrica

ON SOCIAL/BEHAVIORAL GRADIENT AND PERINATAL CIRCUMSTANCES AMONG CHILDREN’S AND 26

Anova one-way F=2.37 p=0.03 F=1.95 p=0.02 F=2.80 p=0.01 F=1.41 p=0.09 Once a year Males 0.12±0.33 1.08±1.78 7.49±4.18 8.67±4.52 Females 0.09±0.41 1.59±1.91 9.11±3.97 10.79±4.3 7 Anova one-way F=1.68 p=0.19 F=1.49 p=0.17 F=1.08 p=0.37 F=1.65 p=0.04 Every 2 years Males 0.37±0.54 1.61±2.71 7.80±4.69 9.76±5.40 Females 0.28±0.81 1.50±2.92 10.17±4.7 8 11.94±5.3 8 Anova one-way F=3.46 p=0.02 F=1.09 p=0.38 F=2.01 p=0.01 F=1.69 p=0.04 Brushing frequency

More than once a day 0.21±0.64 1.25±2.27 7.89±4.30 9.35±4.80 Once a day 0.24±0.57 2.17±3.29 8.69±5.01 11.11±5.6 6 Anova one-way F=1.48 p=0.18 F=1.80 p=0.04 F=1.42 p=0.10 F=2.49 p<0.01

Table 2. Sample distribution by Filled and Sound Teeth (FS-T)

according to social gradient and oral health behaviors. Only statistically significant associations are reported.

FS-T 3-23 n (%) FS-T 24-25 n (%) FS-T 26-27 n (%) FS-T 28 n (%) Educational level Primary school 18 (3.75) 21 (4.37) 20 (4.17) 27 (5.62) Secondary school 29 (6.04) 32 (6.67) 77 (16.04) 89 (18.54) University degree 16 (3.34) 19 (3.95) 40 (8.34) 92 (19.17) c2(6) = 25.70 p<0.01 Smoking habits No smoking 36 (7.50) 47 (9.80) 99 (20.62) 170 (35.41) Smoking 27 (5.62) 25 (5.21) 38 (7.92) 38 (7.92) Χ2(3) 18.41 p<0.01

Frequency of tooth brushing

Less than 2 times/day 37 (7.70) 31 (6.45) 53 (11.04) 68 (14.17) More than 2 times/day 26 (5.41) 41 (8.54) 84 (17.50) 140 (29.17) c2(3) = 14.21 p<0.01

Table 3. Multinomial logistic regression showing the significant

associations among categorised DMFT, FS-T scores and social gradient and oral health behaviors.

RRR Std. Err. P >|z| [95% Conf. Interv.] DMFT 0-5 (base outcome) DMFT 6-10 Gender (females) 1.74 0.50 0.05 0.99-3.05 Work category (Unemployed/housewife) 1.67 0.22 <0.01 1.28-2.17 DMFT 10-15 Gender (females) 3.44 1.03 <0.01 1.91-6.20 Work category (Unemployed/housewife) 2.26 0.34 <0.01 1.67-3.04 Tooth brushing (Less than 2

times/day) 0.56 0.18 0.06 0.30-1.03 DMFT 15-28 Gender (females) 3.94 1.45 <0.01 1.91-8.11 Work category (Unemployed/housewife) 3.19 0.68 <0.01 2.10-4.84 Tooth brushing (Less than 2

times/day) 0.16 0.62

<0.01

0.07-0.34

Number of observations= 480 Log likelihood = -583.97 p< 0.01

RRR Std. Err. P >|z| [95% Conf. Interv.]

FS-T 3-23

Gender (females) 1.97 0.61 0.03 1.08-3.62

Smoking (smokers) 2.54 0.83 <0.01 1.33-4.84

Educational level (primary

school) 0.51 0.11

<0.01

0.33-0.79 Tooth brushing (Less than 2

times/day) 0.39 0.12 <0.01 0.21-0.72 FS-T 24-25 Gender (females) 1.75 0.50 0.05 0.99-3.08 Smoking (smokers) 2.01 0.64 0.02 1.07-3.78

Educational level (primary

school) 0.48 0.10 <0.01 0.32-0.73

FS-T 26-27

Educational level (primary

school) 0.69 0.11 0.02 0.50-0.95

FS-T 28 (base outcome)

Table 4. Association between social/behavioral gradient levels and

dental health (DMFT and FS-T categories).

Gradient Best level n (%) Good level n (%) Bad level n (%) Worst level n (%) DMFT 0-5 22 (24.18) 24 (26.37) 30 (32.97) 15 (16.47) DMFT 6-10 52 (29.38) 67 (37.85) 34 (19.21) 24 (13.56) DMFT 10-15 54 (37.24) 42 (28.97) 30 (20.69) 19 (13.10) DMFT 15-28 13 (19.41) 20 (29.85) 17 (25.37) 17 (25.37) c2(9) = 20.17 p=0.02 Z=0.02 p=0.99 FS-T 3-23 13 (20.63) 15 (23.81) 15 (23.81) 20 (31.75) FS-T 24-25 16 (22.22) 22 (30.56) 20 (27.78) 14 (19.44) FS-T 26-27 41 (29.93) 40 (29.20) 37 (27.01) 19 (13.86) FS-T 28 71 (34.13) 76 (36.54) 39 (18.75) 22 (10.58) c2(9) = 25.68 p<0.01 Z=-4.31 p<0.01

PAPER II

Does a social/behavioural gradient exist among Italian

children? A cross sectional study?

Introduction

Early Childhood Caries is a virulent form of caries that specifically affects the primary dentition. The onset of the disease is observed in children younger than 2 years of age, thus it can occur as soon as the first primary tooth erupts [Huntington et al, 2002; Ramos-Gomez et al, 1999]. Early Childhood Caries is neither self-limiting nor responsive to short term pharmacological management and remains a major and significant personal and public health concern [Jones et al, 2005]. Dental caries is generally considered a social and life style disease with its main etiologic factors being fermentable carbohydrates, cariogenic bacteria, a susceptible tooth, and length of exposure [Burt, 2005; Reisine and Douglass, 1998; Seow, 1998; Keyes, 1960].

In young children there may be exceptional behavioral patterns associated with feeding habits and oral hygiene [Seow, 1998]. More specifically, while the children are in the stage of primary socialization, their childhood behaviors will persist into maturity. Among behavioral factors, feeding habits such as the baby bottle custom, the use of pacifiers, the sugar intake, the oral hygiene and daily toothbrushing, all being influenced by parents’ oral health conceptions and behaviors, one of the main risks factors for children is still represented by the low socio-economical level of their parents. [Harris et al 2004].

Based on the multifactorial and chronic nature of the dental caries disease process, studies on risk assessment result in being complex, with multiple influences at the individual, family, and community level challenging the prediction throughout the life of an

individual [Twetman et al, 2009; Zero D. et al, 2001; Twetman et al 2013; Fontana et al, 2015].

The universal prevalence of dental caries is a persistent reminder of the need for effective preventive dental health education. Preventive strategy intervention across early childhood should be the most appropriate action to ensure healthy dental habits throughout life. Knowledge on how to frame subjects at higher risk for developing the disease is essential for the implementation of preventive attributes in a given population.

As a social/behavioral gradient has been proven to exist among Italian adults, the aim of this cross-sectional study was to speculate on the potential presence of a translated social/behavioral gradient on Italian schoolchildren as well, including combined socio/economic characteristics of caregivers, moreover children’s and adults’ attitudes [Arrica et al, 2017]. Furthermore, its possible correlation with caries patterns was intended to be sought.

Material and methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted from November 2016 to July 2017 targeting a cohort of children born during the period 2011-2013 in Sassari, Italy. Data regarding the total number of residents in Sassari from pre-school groups were derived from the National Statistical Institute (Italian National office of Statistics. ISTAT http://www.demo.istat). The total number of children born in 2011, 2012 and 2013 was 7244. The study designed was approved by the ethical committee of the University of Sassari (n°SS0422/2016). In order to increase the power of the study with specific reference to the research question later reported on Paper III, a mixed randomized sampling procedure was performed (Fig.2).

A simultaneous invitation was sent to all deans of Primary Schools in Sassari Province sharing the purpose of the study; then a letter was addressed to the children’s parents together with a questionnaire and a consent form. All documents were to be signed in order to attest the understanding of the contents and to authorize to sign up the child at the different study phases.

Medical birth charts of 6775 toddlers living in Sassari were also cross-investigated and mothers who signed their agreement to be recalled for scientific purposes after giving birth were invited to join the project with their children. The subjects affected by any syndrome that could impact the oral cavity were excluded from the sample to avoid confounding factors.

Power analysis was performed based on a starting population of 7244 children aged 3-5 year old (3.1.9.2-Apple G*Power ©) adding a prevalence ratio of 40% to safeguard against the risk of disease spread. Error probability of 0.05 and actual power of 0.95 were considered and the final total sample size was set to 309. Invitations reached 2191 toddlers and 751 accepted to be eventually examined.

Clinical examinations

Prior calibrated dentists from the Italian study-group on Early Childhood Caries (K=0.85-0.91) recorded the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) scores across the whole study.

The examiners received dedicated training sessions and intra- and inter-examiners reliability was assessed before the survey started. Fifty subjects were examined immediately after the training session was accomplished and again after 72 hours. Inter-examiner reliability was assessed through the ANOVA analysis of variance for fixed effect with reference to a benchmark [Castiglia et al, 2007]. The

intra-examiner reproducibility was estimated as a percent agreement using Cohen’s Kappa statistics. A good examiner reliability compared to the benchmark was found without significant differences (p = 0.12) and with a low value of mean squares for error.

Children were visually and tactile examined in a fully equipped pediatric dental office at the University of Sassari, with optimal artificial light, a WHO ball-ended probe and a plain n°5 mirror. No radiographic examination was taken.

Questionnaire

A comprehensive questionnaire covering maternal and birth-related factors was distributed to the mothers before handling their kids’ dental assessment. The format of the questionnaire referred to the one published in Paper I. A prior validation was performed on a reduced sample to confirm the feasibility of any amendments. Information related to maternal and birth-related items was here not considered at this point.

The questionnaire was highly structured and divided into three main areas: (1) personal data and related caregivers’ information (age, gender educational level, employment categorization; marital status), (2) life-style behavior (dietary habits; frequency of ), (3) oral health behavior (tooth brushing, frequency of dental check-ups; fluoride administration; falling asleep using a pacifier).

Parental educational level was classified as: primary school, secondary school and university. Employment categorization was defined as: unemployed, employed and private practitioner. Marital status was considered as single; married or divorced. The categorization for frequency of consumption of chewing gums, snacks and soft drinks between meals was specifically stated for each

variable according to their distribution in tables.

Gradient

With reference to the Paper I, a social/behavioral gradient was generated as the sum of the worst circumstances recorded by the questionnaire, regarding social inequalities and oral health behaviors. [Arrica et al, 2017].

The influence of each component of the questionnaire on caries profiles was analyzed with chi square tests and reported in Table 5. All variables showing to be significantly associated with caries severity (p<0.05) were appraised together for assessing possible collinearities, thus considered for the final construction of the social/behavioral gradient.

A dummy variable was generated for any of the associated variables, taking value 1 anytime that the worse condition of the abovementioned variables was shown. A multinomial logistic regression displayed the impact of each dummy on the caries severity and how they interplayed together. The loss of information linked to the dichotomization of the events, might have seriously underestimated the extent of variation in outcome between groups, such as the risk of some event, and considerable variability might have been subsumed within each group. Therefore, basing of the current knowledge on some specific determinants related to the etiopathogeneses of Early Childhood Caries, it was decided to individually cross check some of the categorical variables together with the pooled significant dummies to assess their own impact on caries profiles. Eventually, after several adjustments from the crude model the gradient was generated in accordance with the results suggested by the last multinomial logistic regression analyses reported in Table 7

.

Basing on the sample distribution and assuming the time needed to cumulate risk factors before showing a clinical sign for the studied disease, in order to improve the significance of the predictive model, it was decided to stratify children in three levels of social gradient: “good”, with up to one result, “bad”, with at least two, “worst”, from two and above.

The association of the different caries risk categories (gradient) and caries severity was calculated (Table 7). The nonparametric test for trend across ordered groups as an extension of the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was also estimated (Table 7).

Furtherstatistical considerations

Data from the dental examination and questionnaire were directly entered in the FileMaker Pro 9.0 Runtime database for Ipad mobile device and then exported to Excel® Microsoft spread sheet . All data were eventually managed through the software STATA® (Mac version 13).

Descriptive statistics and cross-tabs were calculated between both caries experience and caries severity by questionnaire items, specifically focusing on social and behavioral topics.

Dental examination data were treated as numerical ordinal data for ICDAS scores. More precisely caries severity was classified in three categories as follows: when all teeth were coded ICDAS = 0 subjects were considered caries free; subjects were measured as having caries in enamel if at least one tooth was coded ICDAS = 1–3; for subjects having at least one tooth coded ICDAS = 4–6 the level

was considered as the dichotomization between caries free and caries affected, with no regards to their level of disease severity.

The strength of a potential association between Early Childhood Caries at different severity stages (dependent variable) and other categorical independent variables was assessed through a multivariate logistic regression and expressed as relative risk ratios. The margin of error for statistical significance was always set at 5%.

Results:

The total of the study population was represented by 751 children, aged 3-5 years old, of whom 51,79% were male and 48,21% female. The overall caries prevalence was 46,22%. When stratifying the sample by caries severity, no great differences in the distribution according to caries in enamel nor dentin were found. More specifically, caries limited to the enamel level were found in the 21.39% of the sample, while caries at dentinal level were reported at 24.33%.

As regards social and behavioral determinants, parental education was stated to be limited to Primary or Secondary schools respectively for the 10.34% and the 34.88% of the mothers, while it corresponded to the 16.39% and the 35.81% of the fathers

Level on unemployment among fathers and mothers was almost equally distributed (14.33% vs 14.52%), however a significant statistical association with caries severity was just found for fathers. Here a social higher rank of occupation represented a protective factor, especially towards the immediate onset of the disease (p=0.01 for ICDAS 1-3 (Table 6).

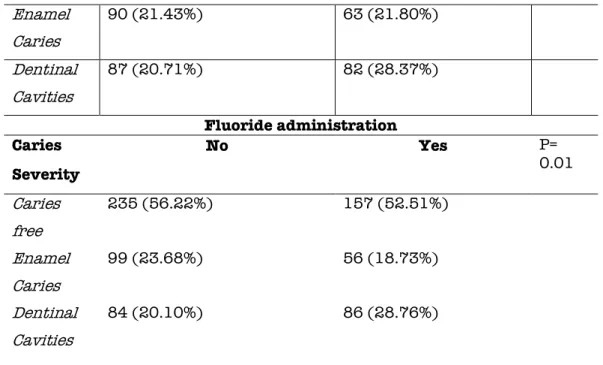

Even the marital status of fathers resulted in being significantly associated with caries in dentin (p<0.01, data non reported in tables). In bivariate analyses, significant statistical associations were found

among chewing gums users (p<0.01), fluoride consumers (p=0.01), juices and soft beverages frequent drinkers (p=0.02), and the habit of brushing teeth after meals (p<0.01). Having snacks in between meals was also strictly associated with caries severity (p<0.01). All the associations were summarized in Table 5.

Table 8 displayed the translation of the social/behavioral gradient on children’s’ population, which is clearly able to highlight how the combination of the worst social and behavioral levels could predict children to be exposed at a greater future risk for caries. Subjects reporting more than 2 worst results in their questionnaire showed the worst dental health patterns (p<0.01). A statistically significant trend was observed regarding the caries severity scores and the worst social behavioral conditions (Z=3.99, p<0.01).

Discussion:

It is nowadays broadly recognized that health outcomes are deeply influenced by a variety of social factors outside of health care. The dramatic differences in morbidity, mortality, and risk factors that researchers have documented within and between countries are patterned after classic social determinants of health, such as education and income. [Link BG et al, 1995; World Health Organization, Commission on Social Determinants of Health; 2008]

The social environment in which children grow up is thus closely linked with their personal health.

Being dental caries on of the most prevalent disease worldwide, with the majority of caries lesions being concentrated in few, often disadvantaged social groups, this study aimed to explore the potential presence of a social/behavioral gradient in children’s’ population as well, which could relate with their pattern of Early Childhood Caries. [Arrica M et al, 2017]

With reference to caries figures results, this cross-sectional investigation specifically found a high prevalence of dentinal cavities in Sardinian toddlers (24.23%). This results seemed almost consistent once compared with previous reports stating the Italian prevalence of between 14,4% and 70,6% [Congiu et al, 2014; Nobile et al, 2013; Cianetti S. et al, 2017; Ferrazzano GF et al, 2016; Ugolini et al, 2018]

Several social and behavioral factors were then evaluated for Early Childhood Caries, before combining them in a cumulative predictive tool as the gradient.

As internationally proven, the parental lower socioeconomic status, a low schooling profile of the mothers is well known to be specifically associated with severe patterns of caries in children. From translating the author’s knowledge on the current results, it seemed as if less-educated mothers more often experienced either a low emotional or practical support than mothers with higher level education. [Crocombe LA et al, 2018; van der Tas JT, 2017]

According with this interpretation, children born from caregivers set at a low educational profile, commonly were the same who showed the majority of risk behaviors, such as high frequency of drinking and eating between meals, or not brushing teeth after having a meal. previously shown for the adults, the cumulation of all these factors, exposed the sampled children both at a higher caries risk, and at a higher caries severity profile.

Since the presence of a social/behavioral gradient in oral health among Italian adults was demonstrated, it might be interesting to declinate its use in practical community dentistry to help clinicians to identify children who are at a higher risk for future caries lesions. A key preventive target should be to educate pregnant women or women with infants on avoidance of caries-promoting behaviors such

as the use of pacifiers, excessive sugar intake and low-frequency toothbrushing as much as improper toothbrushing methods [Peltzer and Mongkolchati, 2015]. Even if the quantification of the cumulative effect of the risk factors could not be estimated in such a cross-sectionally designed study, results of this report are sufficient to hope that oral health care system could be re-oriented to reduce inequalities in oral health through an evidence-based, public health approach.

After all, it may be useful to adopt an intervention approach, which considers the core social/behavioral gradients in dental health and uses a more patient-centered approach, such as motivational attitude.

References

1. Arrica M, Carta G, Cocco F, Cagetti MG, Campus G, Ierardo G, et al. Does a social/behavioural gradient in dental health exist among adults? A cross-sectional study. J Int Med Res. 2017;45(2):451-61. 2. Burt BA. Concepts of risk in dental public health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33(4):240-7.

3. Castiglia P, Campus G, Solinas G, Maida C, Strohmenger L. Children's oral health in Italy: training and clinical calibration of examiners for the National Pathfinder about caries disease. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2007;5(4):255-61.

4. Cianetti S, Lombardo G, Lupatelli E, Rossi G, Abraha I, Pagano S, et al. Dental caries, parents educational level, family income and dental service attendance among children in Italy. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2017;18(1):15-8.

5. Congiu G, Campus G, Sale S, Spano G, Cagetti MG, Luglie PF. Early childhood caries and associated determinants: a cross-sectional study on Italian preschool children. J Public Health Dent. 2014;74(2):147-52.

6. Crocombe LA, Allen P, Bettiol S, Babo Soares LF. Parental Education Level and Dental Caries in School Children Living in Dili, Timor-Leste. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2018;30(2):128-36.

7. Ferrazzano GF, Sangianantoni G, Cantile T, Ingenito A. Relationship Between Social and Behavioural Factors and Caries Experience in Schoolchildren in Italy. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2016;14(1):55-61.

8. Fontana M. The Clinical, Environmental, and Behavioral Factors That Foster Early Childhood Caries: Evidence for Caries Risk Assessment. Pediatr Dent. 2015;37(3):217-25.

caries in young children: a systematic review of the literature. Community Dent Health. 2004;21(1 Suppl):71-85.

10. Huntington NL, Kim IJ, Hughes CV. Caries-risk factors for Hispanic children affected by early childhood caries. Pediatr Dent. 2002;24(6):536-42.

11. Jones S, Burt BA, Petersen PE, Lennon MA. The effective use of fluorides in public health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(9):670-6.

12. Keyes PH. The infectious and transmissible nature of experimental dental caries. Findings and implications. Arch Oral Biol. 1960;1:304-20.

13. Nobile CG, Fortunato L, Bianco A, Pileggi C, Pavia M. Pattern and severity of early childhood caries in Southern Italy: a preschool-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:206.

14. Peltzer K, Mongkolchati A. Severe early childhood caries and social determinants in three-year-old children from Northern Thailand: a birth cohort study. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15:108.

15. Ramos-Gomez FJ, Tomar SL, Ellison J, Artiga N, Sintes J, Vicuna G. Assessment of early childhood caries and dietary habits in a population of migrant Hispanic children in Stockton, California. ASDC J Dent Child. 1999;66(6):395-403, 366.

16. Reisine S, Douglass JM. Psychosocial and behavioral issues in early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26(1 Suppl):32-44.

17. Seow WK. Biological mechanisms of early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26(1 Suppl):8-27.

18. Twetman S, Fontana M. Patient caries risk assessment. Monogr Oral Sci. 2009;21:91-101.

can we achieve consensus? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41(1):e64-70.

20. Ugolini A, Salamone S, Agostino P, Sardi E, Silvestrini-Biavati A. Trends in Early Childhood Caries: An Italian Perspective. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2018;16(1):87-92.

21. van der Tas JT, Kragt L, Elfrink MEC, Bertens LCM, Jaddoe VWV, Moll HA, et al. Social inequalities and dental caries in six-year-old children from the Netherlands. J Dent. 2017;62:18-24.

22. Zero D, Fontana M, Lennon AM. Clinical applications and outcomes of using indicators of risk in caries management. J Dent Educ. 2001;65(10):1126-32.

Table 5. Influence of each component of the questionnaire on caries profiles (caries experience or caries severity)

Mother’s educational level Caries

Experien ce

Primary

School Elementary School University P val ue No 30 (39.47%) 111 (44.40%) 242 (61.89%) P<0.01 Yes 46 (60.53%) 139 (55.60%) 149 (38.11%) Caries Severity Caries free 30 (39.47%) 110 (44.35%) 247 (63.17%) Enamel Caries 15 (19.74%) 69 (27.82%) 72 (18.41%) Dentinal Cavities 31 (40.79%) 69 (27.82%) 72 (18.41%)

Father’s educational level Caries

Experien ce

Primary

School Elementary School University

No 59 (51.75%) 164 (49.55%) 148 (60.91%) P=0. 02 Yes 55 (48.25%) 167 (50.45%) 95 (39.09%) Caries Severity Caries free 60 (52.63%) 165 (50%) 150 (61.98%) P<0.01 Enamel Caries 18 (15.79%) 87 (26.36%) 46 (19.01%) Dentinal Cavities 36 (31.598%) 78 (23.64%) 46 (19.01%)

Caries Experien ce

Unemployed Employed Private practicioner P= 0.0 2 No 45 (46.88%) 113 (48.71%) 199 (58.70%) Yes 51 (53.12%) 119 (51.29%) 140 (41.30%) Caries Severity Caries free 47 (48.96%) 113 (48.92%) 202 (59.59%) P=0.05 Enamel Caries 27 (29.12%) 60 (25.97%) 61 (17.99%) Dentinal Cavities 22 (22.92%) 58 (25.11%) 76 (22.42%)

Chewing gum habit Caries

Experien ce

Never Rarely Sometimes Often P<0. 01 No 126 (62.38%) 154 (55.20%) 77 (51.33%) 29 (35.80%) Yes 76 (37.62%) 125 (44.80%) 73 (48.67%) 52 (64.20%) Caries Severity P<0. 01 Caries free 76 (37.62%) 125 (44.80%) 73 (48.67%) 52 (64.20%) Enamel Caries 43 (21.29%) 66 (23.74%) 31 (20.81%) 14 (17.28%) Dentinal Cavities 30 (14.81%) 58 (20.86%) 40 (26.85%) 38 (46.81%)

Between meals snacks and soft drinks Caries

Severity

Never Sometimes Often Always P<0. 01

Caries free

213 (59%) 90 (47.62%) 56 (51.38%) 33

Enamel Caries 86 (23.82%) 37 (19.58%) 22 (20.18%) 7 (12.28%) Dentinal Cavities 62 (17.17%) 62 (32.80%) 31 (28.44%) 17 (29.82%) Juces consumption Caries Severity Never/rarel y

Sometimes Often Always P=0. 02 Caries free 164 (59.21%) 119 (53.12%) 80 (49.08%) 28 (58.33%) Enamel Caries 66 (23.83%) 49 (21.88%) 30 (18.40%) 8 (16.67%) Dentinal Cavities 47 (16.97%) 56 (25%) 53 (32.52%) 12 (25%)

Brushing teeth after meals Caries

Experien ce

Never Rarely Sometim es Often Always P=0.05 No 21 (35.59 %) 96 (55.81% ) 137 (57.08%) 110 (54.73 %) 23 (57.50% ) Yes 38 (64.41 %) 76 (44.19% ) 103 (42.92%) 91 (45.27 %) 17 (42.50% ) Caries Severity Caries free 22 (35.59 %) 96 (55.81% ) 139 (57.08%) 112 (54.73 %) 22 (57.50% ) Enamel Caries 21 (35.39 %) 35 (20.47% ) 59 (24.58%) 33 (16.42 %) 3 (7.69%) Dentinal Cavities 16 (27.12 %) 40 (23.39% ) 42 (17.50%) 56 (27.86 %) 14 (35.90% )

Falling asleep while breastfeeding Caries Severity No Yes P= 0.04 Caries free 243 (57.86%) 144 (49.83%)

Enamel Caries 90 (21.43%) 63 (21.80%) Dentinal Cavities 87 (20.71%) 82 (28.37%) Fluoride administration Caries Severity No Yes P= 0.01 Caries free 235 (56.22%) 157 (52.51%) Enamel Caries 99 (23.68%) 56 (18.73%) Dentinal Cavities 84 (20.10%) 86 (28.76%)

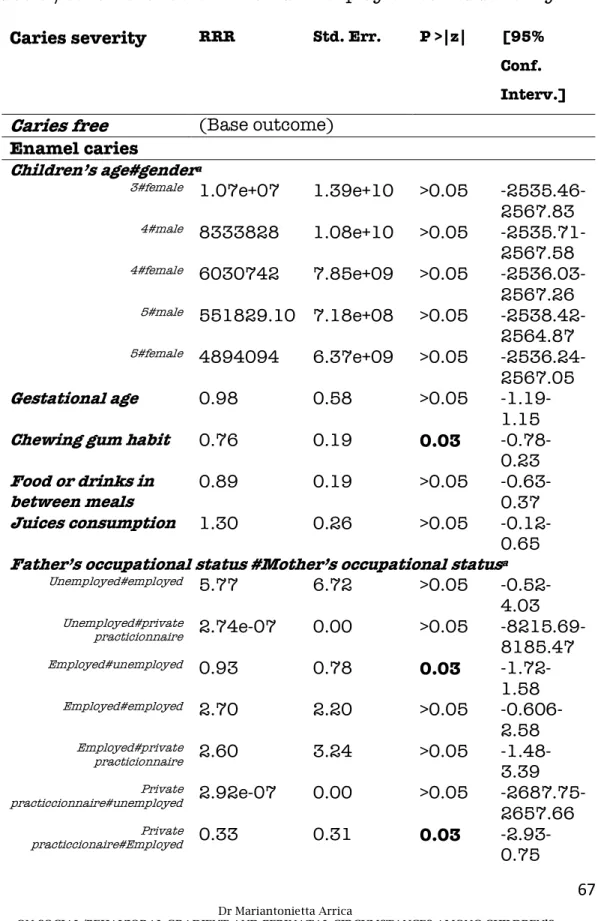

Table 6. Multinomial logistic regression showing the protective role

of higher paternal occupation on caries severity.

RRR Std. Err. P >|z| [95% Conf. Interv.] Caries free Base outcome

Enamel caries Father’s occupation 0.80 0.07 0.01 0.66-0.95 Dentinal caries Father’s occupation 0.91 0.14 0.07 0.44-1.04

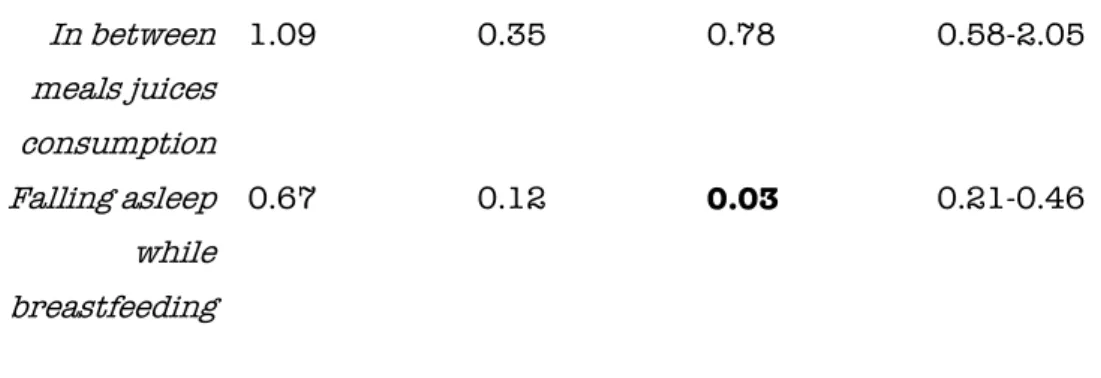

Table 7. Adjusted multinomial logistic regression showing the

interaction of the significant dummies with caries severity related with the gradient construction.

RRR Std. Err. P >|z| [95% Conf. Interv.] Caries free Base outcome

Enamel caries Mother’s educational level 1. 35 0.45 0.36 0.70-2.63 Administration of fluoride 0. 86 0.17 0.42 0.58-1.25 Brushing teeth after meals 2.69 0.87 <0.01 1.41-5.09 Juices consumption 1.45 0.27 0.05 0.99-2.09 In between meals juices consumption 0.50 0.21 0.10 0.21-1.16 Falling asleep while breastfeeding 0.81 0.16 0.30 0.55-1.19 Dentinal caries Mother’s educational level 2.43 0.68 <0.01 1.40-4.21 Administration of fluoride 1.56 0.28 0.01 1.08-2.23 Brushing teeth after meals 2.03 0.71 0.04 1.02-4.05 Juices consumption 1.47 0.27 0.03 1.02-2.10

In between meals juices consumption 1.09 0.35 0.78 0.58-2.05 Falling asleep while breastfeeding 0.67 0.12 0.03 0.21-0.46

Table 8. Logistic regression proving the association of the different

caries risk categories (gradient) and caries severity.

. Caries severity Odds Ratio Std. Err. P>|z| [95% Conf. Interval] gradient 1.45 0.13 <0.01 1.22-1.72

Number of observations= 751 Log likelihood = -731.31 p< 0.01

Number of observations= 751 Log likelihood = -508.30 p< 0.01 Z= 3.99 p<0.01 a

a Nonparametric test for trend across caries severity scores and the worst social/behavioral

PAPER III

Are maternal and perinatal health circumstances related to

caries experience in Italian children?

Introduction

Mode of delivery influences early oral colonization. Current literature suggests that the gastrointestinal tract of a regular fetus is commonly sterile. The first exposure to microorganisms in vaginally delivered infants occurs during the passage through the birth canal, whereas the first contact to bacteria among infants born by Caesarian section (C-section) is from parents’ skin, health providers’ and surgical equipment. Therefore during vaginal delivery, the contact with the maternal vaginal and intestinal flora is a critical source for establishing the infant's colonization. Conversely, in Cesarean Sections where no direct contact occurs, all the surrounding bacterial environment, which does not belong to the moms plays an essential role in newborns’ gut colonization. [Biasucci et al, 2008]

Both the possible long-term effects and the impact that this difference in exposure may have on the child have yet to be determined. Moreover, it is still uncertain whether this flora variety shown at a gut level is universally applied to the oral cavity as well and how this could affect caries patterns in early childhood. On this matter, several authors reported results from comparisons of the oral microbiota in infants delivered by this different routes. Vaginally delivered infants werw shown to have a significantly higher number of detected taxa compared to the Cesar-section group microbiota. [Lif Holgerson et al, 2011]. In the same group, a higher prevalence of certain strains of health-related streptococci and lactobacilli was also reported [Barford et al. 2011].

Moreover, binomial studies between mothers and their kids to determine the commonality of Mutans Streptococci at the time of the initial acquisitions have been reported during the last three decades.