Arabic translations by

Hafed Walda, Mustafa Turjman, Abdulrhim Saad Sharif, Mazin A.S. Abdulgader el Mziene

Archaeological Mission of

Chieti University in Libya:

Reports 2006-2008

Oliva Menozzi

Archaeological Mission of

Chieti

University in Libya: R

eports 2

006-2

008

Oliva Menozzi

RES I

Reports, Excavations and Studies of the Archaeological Unit

of the University G. d’Annunzio of Chieti-Pescara

volume I

Reports, Excavations and Studies of the Archaeological Unit

of the University G. d’Annunzio of Chieti-Pescara

Arabic translations by

Hafed Walda, Mustafa Turjman, Abdulrhim Saad Sharif, Mazin A.S.

Abdulgader el Mziene

Appendixes by

Silvano Agostini, Sonia Antonelli, Luigi Capasso, Enzo Catani, Angela Cinalli, Vincenzo

d’Ercole, Maria Giorgia Di Antonio, Ruggero D’Anastasio, Eugenio Di Valerio, Stefano Faccini,

Domenico Fossataro, Catherine Dobias Lalou, Debora Lagatta, Maria Cristina Mancini, Alberta

Martellone, Oliva Menozzi, Fabio Pallotta, Diego Paltrinieri, Mariangela Schiazza, Maria Carla

Somma, Emanuela Stortoni, Stefano Struffolino, Clara Tamburrino, Marinella Urso, Gabriella

Vitullo.

Archaeopress Archaeology

Archaeological Mission of

Chieti University in Libya:

Reports 2006-2008

Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com

ISBN 978-1-78969-446-8

© and Archaeopress 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by

Enzo Catani, Fabio Pallotta, Diego Paltrinieri, Emanuela Stortoni*

Coastal and archaeological sites of Libya:

Apollonia protection project

INTRODUCTION

Apollonia in Cyrenaic region, modern Libya (Figure 1), was founded by Greek colonists and became a significant commercial centre in the southern Mediterranean. It served as the harbour of Cyrene (Figure 2), 20 km (12 miles) to the southwest. The Greek geographer and mathematician Eratosthenes was born there. Apollonia was one of the five towns of the Libyan Pentapolis. Modern Marsa Sousa corresponds to the ancient port city. For these reasons the city represents a patrimony of the world and for his climate this site could have a great tourist development.

Actually, probably due to the sea rise level (‘Archeometrical

studies evolution of a stretch of coast at the northern part of “Jebel Akhdar” (Libia)’ Busdarghi P., Gessaroli O., Veneri F, Lisbon 6 – 10 April 2004) the piers of the ancient harbour of

Apollonia dating back to the Greek and Roman age, are submerged at about two meters under the sea level and a new harbour was made. Consequently also a regression of the beach line is a result of this phenomena. This is a problem for the forecasted development of tourism activities and a project for the stabilization of the harbour and the beach with new methods taking in account of the environmental conditions appears to be the only solution.

LYBYA: HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL OVERVIEW

INTRODUCTION

Today’s Libyan territory is been a crucible of ancient civilizations : first inhabited by Libyi – autocton people divided in several tribes – then it was colonized by Phoenicians (Oea-Tripoli, Sabratha), and after by Greeks people, that founded blooming cities such as Cyrene, Tocra, Tolemaide, Euesperide, Apollonia. At the end the Roman people become the real owner of this territory and organized this vast region in two different provinces : Cyrenaica in the east side of Sirte gulf and Proconsolar Africa in the west side.

“Vandali and Bizantini” people left too their tracks before of ultimate Arab conquest dated around half of VII century d.c.

This is the historical reason for which this Libyc territory preserves again wide archaeological treasures of these millenarian stratifications of civilization – Roman and Greek period in particular – with stately urban settlements, destroyed along centuries and buried under sand piles.

The ancient buried cities as Sabratha, Leptis Magna, Euesperide, Tocra, Tolemaide, Apollonia and Cyrene (the so called “ Athen of Africa”), represent one of the most important and big archaeological layer of the mediterranean basin.

SHORT STORY ABOUT ITALIAN INVOLVEMENT IN REDISCOVERING LIBYC ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES

Since for the first time of Libya’s militar occupation, it’s been very clear to the italian government, the archaeological value of the territory. Following this consideration, the italian government installed two archaeological superintendencies : the first in Tripolitania area and the second one in Cyrenaica. In few times it started wide and binding escavation works that allowed to find the big structures of the ancient cities of Leptis magna and Sabratha in Tripolitania and Cyrene and Tolemaide in Cyrenaica.

In the meantime, it was managed and realized wide and deep conservative restorations and re-constructing, works of the main monuments of these cities werw planned und realised.

To the discovery of other ancient cities in Cyrenaica – such as Apollonia, Tocra and Euesperide, started by italian mission – contributed also searchers and missions came from U.S.A. ( D. White ), Great Britain ( R. G. Goodchild; J. Vard Perkins; J. Reynolds; J. Lloid; Brker; etc. ) and France ( Chamoux; A. Laronde ).

After a short stop caused by the second world war, the Italian searchers are come back in 1957, studying again the Libyan archaeology : from that period several italian mission (Rome, Palermo, Chieti, Macerata, Urbino, Naples- S. M. Capua Vetere ), worked without interruption doing researches, escavations and restorations, that have permitted to Libyan archaeology to be in first line

* Team of Macerata University, working in 2007 in Libya and presenting the results at Chieti University for the Conference Mediterranea 2008.

about the world classical archaeology. This is in strong evidence looking the several and qualified scientific pubblications edited by italian University searchers as Gaspare Oliverio, Silvio Ferri, Carlo Anti, Gustavo Traversari, Enrico Paribeni, Giacomo Caputo, Salvatore Aurigemma, Luigi Pernier, Sandro Stucchi, Antonino di Vita, Nicola Bonacasa, Lidiano Bacchielli, Mario Luni, Valeria Purcaro, Annalia Ermeti, Oscar Mei, Gianfranco Paci, Silvia Maria Marengo, Emanuela Fabbricotti, Oliva Menozzi, Serena Ensoli, Enzo Catani, Emanuela Cozzoni, Emanuela Stortoni.

APOLLONIA CLIMATOLOGYCAL ASPECTS

The Apollonia area presents the peculiarity climatology common to the greatest part of Cyrenaic littoral. The medium climate of the zone is of Mediterranean-Steppic type with summers decidedly worm and totally dry but with terminal values mitigated by the sea breezes, mild intermediate seasons and absolutely sunny with occasional storms. The winter is mild with brief periods of rain.

From the point of view of the climatic data the climate is marked by seasonal variations influenced by both the Mediterranean Sea and the desert. Summers in the north of Cyrenaica range from 27 to 32°C (81-90°F) a range of temperature extremely appreciable regarding the other Libyan regions. In fact along the Tripolitanian coast, summer temperatures reach between 40 and 46°C (104-115°F); in the farther south, temperatures are even higher.

Rainfall varies from region to region. Rain falls generally in a short winter period and frequently causes floods. The Jabal Akhdar region of Cyrenaica receives a yearly average of 40 to 60 cm (16–24 in). Other regions have less than 20 cm (8 in), and the Sahara has less than 5 cm (2 in) a year.

These data evidence the great possibility that the climate can give to the tourists who can benefit from favourable conditions for the practice of recreational activities, archaeological visits, sea tourism for almost all the year. Besides, this type of climate permits to the tourists to visit the hinterland of Libyan territory too.

APOLLONIA HISTORICAL AND GEOGRAPHYCAL ASPECTS

Apollonia was founded for giving an outlet on the sea to the city of Cyrene - a colony of the Greeks of Thera founded in 632 BC. - and was one of the principal cities in the Hellenic world. Romanized in 74 BC, Cyrene remained a great city, with over one thousand years of rich history until the earthquake of 365. Cyrene, which was described by geographers from Herodotus to Synesius, and its praises were sung by Pindar and Callimachus, is not only one of the cities of the

Mediterranean around which myths, legends and stories have been woven over more than a thousand years, but it is also one of the most impressive complexes of ruins in the entire world.

This is a splendid site situated in an archaeological zone that shows all its fascination to the crystalline sea that bathes the sand. The region of Cyrenica has been neglected in the development of Libya for the past forty years because of its geographic location within the country. In this period, Cyrene has had a lot of resources for conservation or development in comparison to the relatively well-restored sites of Leptis Magna near Tripoli, Libya’s capital.

The city of Apollonia, last from the Greek dominion to that of Romans until that Byzantine conserves very little rests of the Greek civilization, also because of two catastrophic earthquakes. Of this civilization, its splendid Theatre, sited in a particularly picturesque location by the set in front of the sea, is the only remained building, even if it has been partially reconstructed in part during the roman period.

Between the other visible ruins there are the rests of the central Basilica ( figure 4 ) and those of three Byzantine basilicas (Figure 5), of which the splendid marble columns remain still intact, and the rests of the palace of the Dux, the governor of the old province of the Libya Superior.

The zone in which Apollonia is situated (Figure 6) has not yet been still dug and all other wonders wait to be discovered.

APOLLONIA GEOLOGICAL AND GEOMORPHOLOGICAL ASPECTS

The Apollonia area (Figure 7) belongs to a wide coasting plateau, extended in WE direction, which represents the most highest point of Cyrenaica region, owing this to its 882 m above the sea level. Its eastern and southern sides degrade easily toward the Mediaterranean sea coast; in the northern and in the western parts, differently, the relief degrades roughly toward the sea for the presence of a fault plan with steep rocky slopes, broken off by wide terraces. The lower slope is further articulate at least six sea-terraces, characterised by the presence of coasting deposits. The first one is always at six meters above the s.w.l., the package of others reaches almost 200 m. sbove the s.w.l.. The highest point of the plateau is constituted by the Tertiary terms that cover an asymmetrical anticline consisting of cretaceous terrains, until the Cenomanian; these are the domes of Gerdes El Abid, Mghiabir and Gessari. The origin of this territory is the result of a gradual subsidence of the Sirtie basin, begun from the Cretaceous and particularly active during the Eocene and Oligocene. In the slopes of

E. Catani, F. Pallotta, D. Paltrinieri, E. Stortoni Coastal and archaeological sites of Libya: Apollonia protection project Jebel Akhdar (Figure 8), Eocene is well represented and

it covers in outcrop wide surfaces. It is here represented by the Darnah Formation of the Luctioan – Probonian period, that altogether forms in the North of Cyrenaica an unit of about 270 m thick ok massive limestones, sometimes into cliff’s facies where man can find Nummtilites gizehensi , into places of big dimensions, molluscs and, into different levels, manganese’s oxides. They are constituted by wackstones, intercalate, packstones of yellowish colour, compact. The Oligocene rocks are represented in the lower part by the Al Baydà Formation, constituted by mudstone and packstones of yellowish colour, with scarcely assorted fossils, sub-angular, with a good roundness. The thickness changes in Jebel’s territory from 0 to 70. On the upper part the Al Abraq Formation follows, characterising the middle and upper portions constitued by limestones of white colour, yellowish and grey-whitish, with manifest fossils, represented by macroforaminifers. The thickness is about 20 m. The Oligocene finishes with the limestone of Faidia, which then characterises all Lower Miocene thickness included between 10 and 130 m; these are yellow or greyish limestone, with a brown patina, sometimes massive and compact, and with a regular stratification.

The Fossils, which are numerous above all the above and in the upper part of the unity, are represented by Lamellibrach, Echiridi, Forammifers between whom “Eleupidina” and “Nummulites intermedius”. As regards the covering’ deposit, the alluvial history of this sector of Libya, successively to the last interglacial transgression, is similar to the other territories of Mediterranean area, being characterised by two main phases of aggradation, the first referable ti the middle Paleolitic period and the second determined during the Middle-Age. A particularly the stratigraphic rocky unities of Cyrenaica are the deposit of Kuf and Bel Ghadir, respectively for the most ancient and the younger materials. In particularly considering the examined sector, the wadies of Jebel Akhdar have two alluvial deposits. The most ancient of them, the “superior gravels” constituted of stones in matrix of red soils, is found at an altitude of about 20 m above the wadi-bed and it forms alluvial fans at the foot of the coasting slope; it locally dominate some deposits of calcareous tufa and marls, that in wadi Derna, gets a maximum thickness of about 30 m and they proceed sideways in the stratum cemented detritus. The coasting slope at the East of Tolmeita is partially covered with grave cements by calcareous concretions, of an age not established. The second terrace, placed at a lower altitude on the gorges is dominated by stratified debris and it shows thickness inferior to 6 m and often presents a bigger condensation and a more fine composition than the “younger gravel”. The tufa, the alluvial deposit and the stratum detritus are

chronologically subsequent to the inferior sea terrace, placed at the altitude of 6 m, which probably dates back to the last interglacial Period; the deposits of “younger gravels” formed themselves during a following period of sea-level low stand.

COASTA EROSION IN APOLLONIA: ACTUAL SITUATION

Actually for the problems due to the sinking of the ground and the sea rise level showed above, the coastal area of Apollonia has the real necessity to be protected to stabilize the zone to avoid that the sea puts in danger the historical area.

In the below figures (Figures 8 and 9) it is quite clear to perspect the costant material ( calcareous sandstone) degradation of the rest of the monuments and the progressive and inflexible worsening of the coastal erosion.

The general technical proposal for the protection has to be planned taking into account all the environmental and archaeological aspects of this beautiful site.

COASTAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE PROTECTION : PROPOSAL

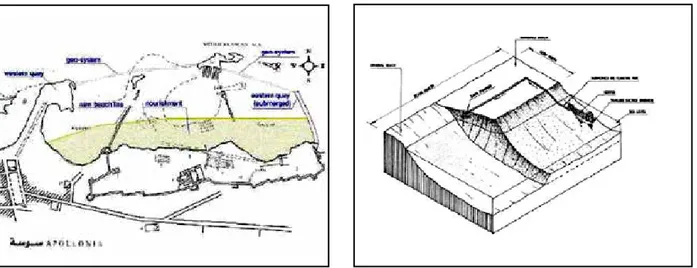

In order to protect the harbour, for its natural geomorphology conformation, the ideal solution approach is a beach nourishment protected by a series of submerged geotubes or other underwater systems with a low enviromental impact. The sand needs to realize the beach nourishment can be taken in land or sea sources, not to far to Apollonia and the sand filling of the interested coastal area will happen using special vessels for nourishment.

This situation can be applied - of course after a pevious escavation and recovery of archaeological founds - and it is optimal because doesn’t permit a longshore transport of the sediments. In fact the harbour area is in the esatern zone demarcated by a submerged quay and in the western by the emerged quay.

Adding in front of the nourishment a geo-system (a geosyntetic cylinder filled with sand), laid down in the east-west direction, this supply a defence for the nourishment and the previous beach line too (Figures 10). The geo-system solution added with the nourisment are soft solutions and permits to modulate the work in several steps and permits to well organize the maintenaince in the future ( figures 11 and 12 ). This technical approach permits to reach two important results : it can ensure in the meantime the stabilisation of coastal line and in this way it can protect the important archaeological treasures of Apollonia.

The same technical approach – adapted to local situation – can be applied in the other important Libian coastal archaeological sites.

ITALIAN – LIBYAN WORKING GROUP: PROPOSAL

Considering the above description and the very delicate and important issue represented by libian

archaeological coastal sites, we propose to define a two-sided technical group – that involves, of course, by italian and libyan governative people – that can work starting from this draft, on writing a detailed technical report, aimed to protect the libyan coastline and its important archaeological heritage.

Figure 1. map of Libya and location of Cyrene Figure 2. the Image Map of Cyrene (Shahhat)

Figure 3 a. Greek theatre. September 2005 Figure 3 b. Greek Theatre. September 2006

E. Catani, F. Pallotta, D. Paltrinieri, E. Stortoni Coastal and archaeological sites of Libya: Apollonia protection project

figure 5. Byzantine Church in Apollonia and Latrun (ancient Erythron)

Figure 6. The Map of Apollonia

Figure 8. Apollonia : archaeological coastal site in erosion

(foto Stortoni) Figure 9. Apollonia : archaeological coastal site in erosion (foto Catani)

Figure 10. layout scheme of archaeological coastal site

protection Figure 11. scheme section of beach nourishment

Bibliography

Abdalrahim Sheriff Saad A., Farag Abdel Hati S., Antonelli S., Menozzi O., Petraccia V., Somma, M. C. 2016. GIS of the chora of Cyrene: Fortifications and Christian buildings in Late Antiquity. Libyan

Studies, vol. 47, p. 31-66.

Abdulrahim Saleh Shariff A., Menozzi O., Di Antonio M.G., D’Ercole V., Mei O. 2018. Training in Restauro dei Materiali Lapidei 2016: rapporto preli-minare. Quaderni di Archeologia della Libia, 21, 345-351 Alfoeldi G. 2000. Spain, CAH XI. Cambridge.

Al Raeid F., Di Valerio E., Di Antonio M.G., Menozzi O., Abdalgader El Mziene M.A. S. and Tamburrino C. 2016. The main Issues of the Cyrene Necropolis and the use of remote sensing for monitoring in the case of the eastern necropolis. Libyan Studies 47, 7-30 Antonaccio, C.M. 1999. Colonization and the origins of Hero Cult. In R. Hägg (ed.), Ancient Greek Hero Cult. Stockholm, 109–21.

Antonelli, S. and Menozzi, O. 2014. Late Roman co-arse ware and amphorae from Cyrenaica (Libya): the case of Lamluda. In N. Poulou-Papadimitiou, E. Nodarou and V. Kilikoglou (eds), LRCW4. Late

Roman Coarse Wares, Cooking Wares and Amphorae in the Mediterranean, Archaeology and Archaeometry. The Mediterranean: a market without frontiers. BAR Int.

Series 2616, 885–896.

Applebaum S. 1964. Jewish status at Cyrene in the Roman Period. PP XIX, 291-303.

Applebaum S. 1979. Jews and Greeks in ancient Cyrene, Leiden.

Arias, P.E. 1940. Scavi archeologici in c.da Caruso Polisà.

NSc 194, 138–61.

Asolati M. 2006, La documentazione numismatica a Cirene, in Luni M. (ed.) Cirene “Atene d’Africa” II, Monografie di

Archeologia della Libia, XXVIII, Roma, pp. 181-192.

Asolati M. 2011, Cirene tardo antica e bizantina: un

ap-proccio numismatico, in Luni M. (ed.) Cirene “Atene d’Africa” III, Monografie di Archeologia della Libia, XXIX,

Todi, pp. 305-315.

Asolati M., Calliari I., Conventi A., Crisafulli C. 2009, Le emissioni provinciali di Traiano per la Cirenaica:

nuove evidenze dalle indagini archeometriche e dall’ana-lisi dei coni, in RIN 110, pp. 317-364.

Bacchielli, L. 1987. La scultura Libya in Cirenaica e la variabilità delle risposte al contatto culturale gre-co-romano. Quaderni di Archeologia della Libia 12, 459–88.

Bacchielli, L. 1990–91. La Tomba cirenea del Buon Pastore. In Rendiconti della Pontificia Accademia

Romana di Archeologia 63. L’Erma di Bretschneider,

Rome, 3–21.

Bacchielli, L. 1992. La Tomba di Demetria a Cirene. In

Quaderni di Archeologia della Libia 15. Rome, 5–22.

Bacchielli, L. 2002a. La Tomba dei ludi a Cirene. Dai viaggiatori dell’Ottocento alla riscoperta. In S. Rinaldi Tufi and A. Santucci (eds), Parole d’oltremare e

altri scritti di archeologia. Urbino, 141–75.

Bacchielli, L. 2002b. La Tomba dei ludi a Cirene. Dai viaggiatori dell’Ottocento alla riscoperta. In Quaderni di Archeologia della Libia 16. Roma, 285–312.

Bacchielli, L. 1994. Un santuario di frontiera, fra polis e chora. Libyan Studies 25, 45–59.

229–33.

Balestrazzi, M., Di Filippo Balestrazzi, E., Gasperini, L. 1976, L’emiciclo di Pratomedes a Cirene: la testi-monianza di un culto aniconico di tradizione dorica.

Cirene e la Grecia, Quaderni di Archeologia della Libya 8.

Pp.108-191.

Barker G. 1985. Agricultural organization in classical Cyrenaica: the potential of subsistence and survey data. In G. Barker, J. Lloyd and J. Reynolds, Cyrenaica in Antiquity. Oxford.

Bechtel, Fr. 1917, Die historischen Personennamen des

Griechischen bis zur Kaiserzeit, Halle (reproduction

anastatique, Hildesheim, Zürich, New York, 1982). Belzic, M. 2015, Les “divinités funéraires” de Cyrénaïque.

Un état de la recherche, mémoire inédit de Master 2,

École pratique des Hautes Études, Paris.

Bennet, P., Buzaian, A., Abdulkareem, F., Khalifa, F. and al-Touati, M. 2008. Four qsur between the Wadis Islan and Samalus, Cyrenaica. Libyan Studies 39, 117–30.

Bentaher F. and Buzaian A. 2010. Roman wine pro-duction in Cyrenaica: new evidence from Balagrae (Al-Beida). In M. Luni (ed.), Cirene e la Cirenaica

Bentaher F. and Buzaian A. 2010. The fort of Al-Motanib. In M. Luni (ed.), Cirene e la Cirenaica

nell’an-tichità. Urbino-Rome. 229-234.

Beschi, L. 1969-1970. Divinità funerarie cirenaiche.

ASAA 21-22, 133-341.

Bernabé, A., Herrero de Jáuregui, M., Jiménez San Cristóbal, A. I., Martín Hernández, R. 2003 (eds).

Redefining Dionysos, Berlin.

Bonacasa, N. 2007. I culti della collina di Zeus a Cirene.

Karthago: Revue d’archéologie méditerranéenne 27,

233–43.

Barlett, J.R. 2002. Jews in the Hellenistic and Roman cities. London.

Beazley, J. D. 1956. Black figure vase painters, London. el Bekri A.O. 1913. Description de l’Afrique Septentrionale.

Typographie Adolphe Jourdan, Algiers.

Boardman, J. and Hayes, J. (eds) 1973. Excavations at

Tocra (1963–65). London.

Bonacasa, N., and Ensoli, M.S. (eds) 2000. Cirene. Milan.

Buzaian, A.M. 2009. A Forgotten Press Building at Lamluda. Libyan Studies 40, 47–54.

Carozza S., Cherstich L, D’Orazio V., Lagatta D. (eds.) 2005. Laserpiciferae Cyrenae. Viaggio nella città

del Silfio. Pescara.

Carter, J.C. 1977. Ancient Crossroads: The Rural Population

of Classical Italy. University of Texas, Austin.

Carter, J.C. 1991. Vent’anni di ricerca nel territorio di

Metaponto. In E. Greco and M. Bats (eds), Siritide e Metapontino. Centre Jean Bérard, Naples-Paestum,

237–59.

Cassel, J. 1955. The cemeteries of Cyrene. PBSR 23, 2–43. Catani, E. 1976. I frantoi della fattoria bizantina di

El-Beida. Quaderni di Archeologia della Libia 8, 435–48. Catani, E. 1998. Fasi edilizie e tecniche murarie della

fattoria paleobizantina di Siret el Giamel nella cho-ra cirenea. In E. Catani and S. M. Marengo (eds), La

Cirenaica in età antica. Macerata,113–35.

Catani E. 2010. Ricerche E Ricognizioni Archeologiche nell’area di Suani el Abiad e Siret el Bab. In M. Luni (ed.), Cirene e la Cirenaica nell’antichità. Urbino-Rome, 59-72.

Cherstich I., Cherstich L. 2008. Violent dialogues between the living and the dead: disfiguring faca-des in Cyrene. In Rakoczy L. (ed.) The Archaeology of

Destruction, Cambridge, 210-38.

Cherstich L. 2002. Surveying the cemeteries of Ancient Cyrene. Preliminaries to a topographic approach. In Muskett G., Koltsida A., Georgiadis M. (eds.) (2002)

SOMA 2001, Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology.

Oxford, 20-7.

Cherstich, L. 2005. The tomb S1 of Cyrene: from the Hellenistic phase to the Christian re-use. In Briault C., Green J., Kaldelis A., Stellatou A. (eds.) SOMA 2003

Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology. Oxford,

33-8.

Cherstich, L. 2006. S4: la tomba di Klearchos a Cirene. In Fabbricotti E., Menozzi O. (eds.), Cirenaica: studi,

scavi e scoperte. Parte I: Nuovi dati da Città e Territorio.

Oxford, 103-20.

Cherstich, L. 2006. Homesickness and Greek Architecture in a colony: the example of Cyrene In Day J., Greenlaw C., Hall H., Kelly A., Matassa L., McAleese K., Saunders E., Stritch D. (eds.) SOMA 2004

Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology. Oxford.

Cherstich, L. 2006. Ricognizione nella necropoli Sud di Cirene: la strada per Balagrae. In E. Fabbricotti and O. Menozzi (eds), Cirenaica: studi, scavi e scoperte. Atti

del X Convegno di Archeologia Cirenaica, Chieti, 24–26 Novembre 2003. Oxford, 391–408.

Cherstich, L. 2007. The Southern Necropolis of Cyrene, PhD Thesis, Brasenose College, University of Oxford. Cherstich, L. 2008. From looted tombs to ancient

so-ciety: a survey of the Southern Necropolis of Cyrene. In Society for Libyan Studies Annual Report 39, 73-93. Cherstich, L. 2008. The Southern Necropolis of Cyrene.

DPhil thesis, University of Oxford.

Cherstich, L. 2008. The role of Alexandria in the Cyrenean cemeteries from Ptolemaic to Roman Times. In Menozzi O., Di Marzio M.L. and Fossataro D. (eds.) SOMA 2005. Symposium on Mediterranean

Archaeology. Oxford, 129-142.

Cherstich, L. 2011. The Changing Funerary World of Roman Cyrene. In Society for Libyan Studies Annual

Report 42, 33-46.

Cherstich, L. 2019. Appendix 2. The Southern Necropolis : brief remarks on the tragic destructions up to 2018. Libyan Studies 50, 120-125.

Cherstich L., Cinalli A., Lagatta D. 2014. Una nuova testimonianza dalla Necropoli di Cirene: la Tomba dei Carboncini (S 147). In Álvarez J.M., Nogales T., Rodà I. (eds.) Centre and periphery in the ancient world. .Actas XVIII Congreso Internacional Arqueolgía Clásica, vol.2. Merida, 1213-1217.

Cherstich L., Fossataro D., Menozzi O. 2010. Gis of the Necropoleis of Ancient Cyrene (Libya). In: Matthiae P., Pinnock F., Nigro L. and Marchetti N. Proceedings

of the 6th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, 313-321.

Bibliography Cherstich L., Menozzi O., Antonelli S., Cherstich I.

2018. A‘living’ necropolis: change and reuse in the cemeteries of Cyrene. Libyan Studies, 49, 121-152, Cherstich, L., and Santucci, A. 2010. A new

disco-very at Cyrene: the tomb S64 and its ‘second-style’ wall paintings: preliminary notes. Libyan Studies 41, 33–45.

Cinalli, A. 2014. Documenting an unknown funerary complex at Cyrene : ‘The Garden Tomb’. Architetural evolution and epigraphic issues . Libyan Studies 45, p. 7-18.

Cinalli, A. 2016. Painted and Charcoal Inscriptions from the Territory of Cyrene: Evidence from the Underworld . In R. Benefiel, P. Keegan (ed.),

Inscriptions in the private Sphere in the Graeco-Roman World, Leiden, p. 181-212.

Costamagna, L. 1987. Il Santuario di Grotta Caruso. In E. Lattanzi (ed.), Il Museo Nazionale di Reggio

Calabria. Roma, 74–77.

Cuntz, O. (ed.) 1990. Itineraria Antonini Augusti et Burdigalense. Stutgardiae.

de Bourville, V. 1848. Lettres à M.Letronne sur les pre-miers résultats et son voyage à Cyrène-Benghasi. In

Rev. Arch.V.

De Cesare, M. 1997, . Le Statue in immagine. Studi sulle

raf-figurazioni di statue nella pittura vascolare Greca. Roma.

de Francovich, G. 1990. Santuari e tombe rupestri dell’antica Frigia e un’indagine sulle tombe della Licia. Roma.

Deubner L. 1962. Attische Feste, Hildesheim.

Di Filippo Balestazzi, E. 2010, Per una storia dell’A-gyieus a partire dall’Esedra di Cirene: in margine ai due leoni, in M.Luni, Cirene nellAntichità. Urbino-Roma 2010, 243-277.

Di Filippo Balestazzi, E. 2006. Santuari e pote-re. Rileggendo Polignac. In E. Fabbricotti and O. Menozzi (eds), Cirenaica: studi, scavi e scoperte. Atti del

X Convegno di Archeologia Cirenaica. Oxford, 45–59.

Di Valerio E., 2004. Le necropoli di Cirene: monumen-talità e culto. In Lasepiciferae Cyrenae. Pescara 40-41. Di Valerio E., Cherstich I., Carinci M., Siciliano F.,

D’Addazio G., Cinalli A. 2005, Votive funerary ni-ches in funerary architecture in Cyrenaica (Libya,). In Briault C., Green J., Kaldelis A., Stellatou A. (eds.) SOMA 2003 Proceedings of the IX Symposium of

Mediterranean Archaeology. Oxford, 53-58.

Di Valerio E. 2008. Nuovi dati sullo studio della necro-poli ovest di Cirene. In O. Menozzi, M. L. Di Marzio, D. Fossataro (eds.). In O. Menozzi, D. Fossataro and M. L. Di Marzio (eds), SOMA 2005. Proceedings of the

IX Symposium of Mediterranean Archaeology. Oxford,

149-154.

Di Valerio, E. 2018. Appendix 1. The Western necropo-lis: the status of preservation to 2018 . Libyan Studies 49.

Di Valerio E. 2019. The Western Necropolis of Cyrene: the Wadi Belghadir road, Libyan Studies 50, 137-146. Di Valerio E. forthcoming. Le tombe Monumentali di

Ain Hofra e le problematiche topografiche, architettoni-che e di riutilizzo della Cirenaica in epoca romana. Tesi di

specializzazione Universitò del Salento.

Di Vita A. 1990. Sismi, Urbanistica e Cronologia assolu-ta in L’Afrique dans l’Occident Romain, I siècle av.J.C. – IV siècle ap.J.C.. Actes du colloque organisé par l’École

Française de Rame (Rome, 3-5 dècembre 1987). Coll. ÉFR

134. Roma, 425-494.

Dobias-Lalou, C. 2000, Le dialecte des inscriptions

grec-ques de Cyrène. Karthago XXV. Paris.

Dobias-Lalou C. 2007 (ed.), Questions de religion

cyrénéenne. Actes du colloque de Dijon, 21–23 Mars 2002. Karthago: Revue d’archéologie méditerranéenne XXVII.

Paris.

Duff A.M. 1928. Freedmen in the early Roman Empire. Oxford.

Dufková, M., and Pečírka, J. 1970. Excavations of far-ms and farmhouses in the chora of Chersonesos in the Crimea. Eirene 8, 124–45.

Duval N. 1989. Les monuments d’époque chrétienne en Cyrénaïque à la lumière des recherches récent-es. In N. Duval (ed.), Actes du XIe Congrès international

d’archéologie chrétienne (Lyon, Vienne, Grenoble, Genève et Aoste, 21–28 septembre 1986). Rome, 2743–805.

Ensoli, S. 2000. Il Santuario di Apollo. In N. Bonacasa and M.S. Ensoli (eds), Cirene. Milan, 104–35.

Ensoli, S. 2008. Per i cinquant’anni di attività del-la Missione Archeologica Italiana a Cirene: Il Santuario d Apollo nella terrazza della Myrtousa. In J. Gonzàles, P. Ruggeri, C. Vismara and R. Zucca (eds), L’Africa Romana. Le ricchezze dell’Africa. Risorse,

produzioni, scambi. Atti del XVI Convegno di Studio. Sevilla 2006. Rome, 2355–82.

Fabbricotti, E. 1987, Divinità greche e divnità libye in rielievi d età ellenistica, in Cirene e i Libyi. Quaderni di

Archeologia della Libya 12, 221-244.

Fabbricotti, E. 1997. Rilievi cultuali del mondo pasto-rale cirenaico. Libya Antiqua 3, 75–81.

Fabbricotti, E. 2000. Il santuario di Budrash & Il san-tuario di Ain Hofra. In N. Bonacasa and M.S. Ensoli (eds), Cirene. Milan, 181–82.

Fabbricotti, E. 2007. Divinità Funerarie Cirenaiche da Barce e Tolemaide. In L. Bacchielli e M. Bonanno Aravantinos (eds). Scritti di Antichità in memoria di

Sandro Stucchi. Studi Miscellanei 29, vol. I, 267-301.

Fabbricotti, E. 2007. Il santuario di Ain Hofra. Karthago:

Revue d’archéologie méditerranéenne 27, pp.93–100.

Fabbricotti, E. 2010. Recenti ricognizioni nel territo-rio di Cirene . In M. Luni (ed.), Cirene e la Cirenaica

nell’Antichità. Cirene “Atene d’Africa” III, Monografie di archeologia Libica 30. Urbino-Roma, 37-46.

Fantoli, A. (ed.) 1933. La Libia negli scritti degli antichi. Roma.

Ferri, S. 1922. Il santuario di Budrasch. Notiziario

Archeologico delle Colonie 3, 95–99.

Ferri, S. 1922b. Un sacello rupestre (mitriaco?) nelle necropoli di Cirene. Bollettino di Studi Storico-Religiosi 2, 28–32.

Ferri, S. 1923. Contributi di Cirene alla storia della reli-gione greca. Libreria di Cultura, Rome.

Forbes, K. 1956. Some Cyrenaican Dedications.

Philologus C (100), 235-232.

Fossataro, D. 2008. GIS of the Gsur in Cirenaica: typo-logies and examples, SOMA 2008. Proceedings of the XII

Symposium of Mediterranean Archaeology. Famagosta 2008. Oxford, 151–58.

Frigerio, C. 1997. Un esempio di architettura elle-nistica funeraria a Cirene: la tomba S 388 . Libya

Antiqua n.s. 3, 51-73.

Frontisi-Ducroux, F. 2008. Les figures funérair-es de Cyrène: stratégifunérair-es de figuration de l’invi-sible, in Estienne, S., Jaillard, D., Lubtchansky, N. e Pouzadoux, C. (dir.) Image et Religion. Collection

du Centre Jean Bérard 28.

Gaifman, M. 2012. Aniconism in Greek Antiquity, Oxford. Gambini V. and Catani E. 1976. Nuove terme

bizanti-ne bizanti-nei dintorni di Cirebizanti-ne. In S. Stucchi (a cura di),

Cirene e la Grecia. Quaderni di Archeologia della Libya 8,

449-463.

Garzya, A., and Roques, D. (eds). 2000. Synesios de

Cyrène. Paris.

Gasperini, L. 2008. Cirene 1957–1966. Le Epigrafi. In A. Arnaldi and S. M. Marengo (eds), Scritti di Epigrafia

Greca. Ichnia 10. Tivoli, 75–104.

Gatier, P.L. 2000. La Legio III Cyrenaica et l’Arabie. In Y. Le Bohec (ed.), Les légions de Rome sous le Haut-Empire. Lyon, 341–49.

Genovese, G. 1999. I Santuari rurali nella Calabria Creca. Rome.

German, G. 1948, Le culte du Bélier en Afrique du Nord, Hesperis XXXV, pp.93-124. Giannakis. G. K. 2001.

Light is Life, Dark is Death. An Ancient Greek and Indo-European Metaphor. Dodoni «Philologia» 30, 127–153.

Giardino, L., and De Siena, A. 1999. Metaponto. In E. Greco (ed.), La città Greca Antica. Rome, 329–63. Goodchild, R.G. 1951. Libyan’ Forts in south-west

Cyrenaica. Antiquity 25: 131–44.

Goodchild, R.G. 1959. Cyrene and Apollonia: An Historical

Guide. Department of Antiquities of Cyrenaica, Tripoli.

Goodchild, R.G. 1966. Fortificazioni e palazzi bizanti-ni in Tripolitabizanti-nia e Cirenaica. In XIII Corso di Cultura

sull’Arte ravennate e bizantina. Ravenna, 225–50.

Goodchild, R.G. 1966. Chiese e battisteri bizantini della Cirenaica. In XIII Corso di Cultura sull’Arte ravennate e

bizantina. Ravenna, 205–23.

Goodchild, R.G. 1976. Libyan Studies: Selected papers of

the Late R.G. Goodchild. Edited by J. Reynolds. P. Elek,

London.

Goodchild, R.G. 1976. Libyan Studies. Selected papers of

late R.G. Goodchild, J. Reynolds (ed.), London.

Goodchild, R., Pedley, J.G., and White, D. 1966–67. Recent discoveries of archaic sculpture at Cyrene. A preliminary report. Libya Antiqua 3/4: 179–98. Greco, E. 1996. Santuari arcaici della Sibaritide. In E.

Lattanzi (ed.), Santuari della Magna Grecia in Calabria. Naples, 182–83.

Hachlili C.R. 1979. The Goliath Family in Jericho: Funerary Inscriptions from a First Century A. D. Jewish Monumental Tomb. BASOR 235, 31-70. Hachlili, R. 2005. Jewish Funerary Customs, Practices and

Rites in the Second Temple Period. Leiden-Boston.

Hägg, R. (ed.) 1999. Ancient Greek Hero Cult. Stockholm. Inan J. and Rosenbaum, E. 1966. Roman and early

Bizantine portraits in Asia Minor. London.

Johansen F. 1995. Roman Portraits III, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. Copenhagen.

Jones A.H.M. 1970. Frontier defence in Byzantine Libya. In F. F. Gadallah (ed.), Libya in History: Historical

Conference, 16–23 March 1968. Benghazi, 289–97.

Jones, G.D.B., Webb, M.E.A., and Bevan, N. 1998. Pleasant Libyan acres: the territory of Cyrene. In E. Catani and S.M. Marengo (eds), La Cirenaica in età

an-tica: Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi-Macerata, 18–20 Maggio 1995. Macerata, 281–88.

Kane, S. 1998. Cultic implications of sculptures in the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore/Persephone at Cyrene. In E. Catani and S.M. Marengo (eds), La

Bibliography Kane, S. 1998. Cultic implications of sculptures in

the Sanctuary of Demeter and Kore/Persephone at Cyrene. In E. Catani and S.M. Marengo (eds), La

Cirenaica in età antica. Macerata.

Kane, S. 2006. Bronze plaques from the archaic favis-sa at Cyrene. In E. Fabbricotti and O. Menozzi (eds),

Cirenaica: studi, scavi e scoperte. Atti del X Convegno di Archeologia Cirenaica. Oxford: 205–16.

Kenrick, P. 2013. Libya Archaeological Guides: Cyrenaica. London.

Koch G. and Sichtermann H. 1982. Roemische

Sarkophage (Handbuch fuer Archeologie 7). Munich.

Kramer, J. 1993. Die Wiener Liste von Soldaten der III. und XXII. Legion (P. Vindob. L2). Zeitschrift für

Papyrologie und Epigraphik 97, 147–58.

Lagatta D. 2005. L’Agorà nel periodo Greco. In Carozza S., Cherstich L, D’Orazio V., Lagatta D. (eds.)

Laserpiciferae Cyrenae. Viaggio nella città del Silfio.

Pescara, 22-24.

Lagatta D. 2008. Cyrenean Greek Sarcophagi. In Menozzi O., Di Marzio D.L. and Fossataro D. (eds), SOMA 2005:

Proceedings of the IX Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology, Chieti (Italy), 24–26 February 2005. Oxford,:

155-160.

Laronde, A. 1987. Cyrène et la Libye hellénistique. Libykai

Historiai, Paris.

Lattanzi, E. (ed.) 1996. Santuari della Magna Grecia in

Calabria. Naples.

Lazzarini M.L. 1996. SEG IX, 50 : una revisione alla luce di vecchi e nuovi frammenti . Studi Miscellanei 29, 175-192.

Lazzarini M.L. 1998. Zeus Melichios e le Eumenidi. Alcune considerazioni. in La Cirenaica in età arcaica. Macerata, 311-320.

Leone, A. 2007. Changing Townscapes in North Africa from

Late Antiquity to the Arab Conquest. Bari.

Leone, R. 1998. Luoghi di culto extra urbani d’età arcaica in

Magna Grecia. Florence.

Luni, M. 1979. Il caravanserraglio di Cirene ed indagine preliminare sui percorsi interni della Cirenaica. In

Quaderni di Archeologia della Libia 10. Rome, 45–65.

Luni, M. 1980. Apporti nuovi nel quadro della viabi-lità antica della Cirenaica interna. In Quaderni di

Archeologia della Libia 11. Rome, 119–37.

Luni, M. 1987. Il Santuario rupestre Libyo del-le ‘Immagini’ a Slonta (Cirenaica). Quaderni di

Archeologia delle Libya 12: 415–58.

Luni, M. 2006. Cirene ‘Atene d’Africa’. Rome.

Luni, M. 2011. Le nouveau sanctuaire de Dèmèter et la “ceinture sacrée” à Cyrène à l’époque royale ”.

CRAI 155/1, 221-247.

Mancini, M.C. and Menozzi, O. 2012. MPM GIS Project. Report 2010–12 and Archaeometric Protocols.

Journal of Heritage in the Digital Era. 1.1, 195–201.

Mattingly, D., Sterry, M., and Leitch, V. 2013. Fortified farms and defended villages of late Roman and late antique Africa. Antiquité Tardive 21, 167–88. Menozzi, O. 2002. Rural sanctuaries in the

terri-tory of Cyrene. In G.M. Muskett, A. Koltsida and M. Georgiadis (eds), SOMA 2001. Symposium of

Mediterranean Archaeology, Liverpool 2001. Oxford,

168–80.

Menozzi, O. 2006. Per una lettura della chora cirenea attraverso lo studio di santuari rupestri e di aree marginali della necropoli di Cirene. In E. Fabbricotti and O. Menozzi (eds), Cirenaica: studi, scavi e

scoper-te. Atti del X Convegno di Archeologia Cirenaica. Oxford,

61–84.

Menozzi, O. 2007. Santuari agresti nella chora di Cirene. Karthago: Revue d’archéologie méditerranéenne 27, 79–91.

Menozzi, O. 2008. New technologies and traditional approaches in reconstructing the ancient land-scape assessment. In O. Menozzi, D. Fossataro and M. L. Di Marzio (eds), SOMA 2005. Proceedings of the

IX Symposium of Mediterranean Archaeology. Oxford,

39–62.

Menozzi, O. 2010. Tracce di suddivisioni agrarie nella chora cirenea e ipotesi di sfruttamento economico del territorio: i dati del GIS e del remote sensing. In M. Luni (ed.), Cirene Atene d’Africa III. Cirene e la Cirenaica

nell’antichità, MAL 30. Roma 2010, 47-58.

Menozzi, O. 2011. Le frontiere sacre della chora di Cirene: culti tra mondo greco-romano e libyo. In G. Firpo (ed.), Fides Amicorum. Chieti, 315–38.

Menozzi, O. 2012. The Archaeological Mission of Chieti University in Cyrenaica: aims, results and possi-bilities. In S. Ensoli (ed.), For the Preservation of the

Cultural Heritage in Libya. A Dialogue among Institutions.

Pisa, 105–109.

Menozzi O. 2014. The Impact if the Greco-Roman wor-ld on the local substratus in Cyrenaica (Libya). In Álvarez Martínez J.M., Nogales Basarrate T., Rodà de Llanza I (eds), Centre and periphery in the ancient

world. .Actas XVIII Congreso Internacional Arqueolgía Clásica, vol.1. Merida, 445-449.

Menozzi, O. 2015, Extramural rock-cut sanctuaries in the territory of Cyrene. Libyan Studies 46, 57-74. Menozzi, O. 2016. Libya: archaeology in war and

the Cultural Heritage and Cultural Tourism Management Archaeology: Proceedings of the Conference, 13 April 2012, Chieti. CTMBAL Project 2. Teramo, 91–110.

Menozzi, O. 2016. Santuari rupestri nella chora di Cirene: incontro tra mondo Libyo, Greco e Romano. In A. Russo (ed.), Santuari Mediterranei tra Oriente e

Occidente. Interazioni e contatti culturali. Rome.

Menozzi O., Antonelli S. 2014. Lamluda: from the excavation to the archaeometric analysis. Libyan

Studies, 45, 65-83.

Menozzi O., Cherstich L., Di Valerio E., Di Antonio M.G., Abdalrahim Shariff Saad A. 2019. A propo-sal for the use of Core and Buffer Zones to protect the heritage of the Cyrenean landscapes. Libyan

Studies, 50, 107-135.

Menozzi O., Di Antonio M.G. 2018. Databases and GIS in the Territory of Cyrene by the Team of the Università di Chieti: Problems and Perspectives.

Quaderni di Archeologia della Libia, 21, 38-43.

Menozzi O., Di Antonio M.G., Di Valerio E. 2015. Le attività della Missione Archeologica dell’Università di Chieti in Libia (2009-2014). Libya Antiqua, vol. 8, 83-107.

Menozzi O., Di Valerio E., Tamburrino C., Abdalrahim Saleh Shariff A., D’ercole V., Di Antonio M.G. 2017. A race against time: monito-ring the necropolis and the territory of Cyrene and Giarabub through protocols of remote sensing and collaboration with Libyan colleagues. Libyan Studies, 48, 69-103.

Menozzi O. and Di Valerio E. 2016. Il Restauro del-la Sfinge Arcaica di Cirene. In: V. Purcaro; O. Mei.

Cirene Greca e Romana II. Cirene Atene d’Africa. Roma,

285-292.

Menozzi O., Di Valerio E., Tordone V., M. C. Mancini (2018). L’Archivio dell’Università di Chieti tra docu-mentazione analogica e digitalizzazione. Quaderni di

Archeologia della Libia, 21, 307-313.

Menozzi, O. and Fossataro, D. 2010. Field Survey, GIS and Excavations in the territory of Cyrene and at Lamluda. Interim Report of Chieti University. Libya

Antiqua n.s. 5: 157–71.

Menozzi, O. and Mancini M.C. 2013. L’Archeologia ita-liana in Cirenaica: alcuni momenti salienti. Bollettino

della Società Letteraria, XXVII, 22-44.

Menozzi O., Mancini M. C. (2014). Il ruolo dell’arche-ologia nei rapporti tra Italia e Libia: il caso della Cirenaica. In Trinchese S. La Libia nella Storia d’Italia. Pescara, 27-65.

Menozzi O., Tamburrino C. 2012. Laser Scanning and Infra-Red Thermographic Prospecting for Diagnostic Mapping and Restoration Projects:

The Case the Painted Tombs at Cyrene (Libya). International Journal of Heritage in the Digital Era, I, 343-349,

Menozzi O., Tamburrino C., Di Antonio M.G., Di Valerio E. (2017). La chora di Cirene:assetto ter-ritoriale e problemi di salvaguardia. In: Angela Pontrandolfo Michele Scafuro. Dialoghi sull’Archeo-logia della Magna Grecia e del Mediterraneo. Atti del I Concìvegno di Studi. Paestum 7-9 settembre 2016. p. 399-414

Michel, V. 2012. Échanges entre Égypte et Cyrénaïque à l’époque byzantine (IVe-VIIe siècles p.C.): histoi-re et architectuhistoi-re chrétienne. In S. Guedon (ed.),

Entre Afrique et Egypte. Relations et échanges entre les espaces au Sud de la Méditerranée à l’époque

ro-maine (Université de Limoges, 23–24 September 2010). Bordeaux, 188–209.

Michel, V.. 2012. La christianisation de l’espace urbain en Cyrénaïque. In Chr. Couvenhes (ed.), L’hellénisme

d’une rive à l’autre de la Méditerranée. Hommage à André Laronde. Paris, 263–309

Micheli, M.E., and Santucci, A. (eds) 2000. Il Santuario delle Nymphai Chtoniai a Cirene. Il sito e le terrecot-te. Rome.

Mohamed F.A., Reynolds J. 1997. New funerary in-scriptions from Cyrene , Libya Antiqua n.s. 3, 31-45. Muggia, A. 2000. L’area di rispetto come

indicato-re di politiche demografiche e di gestione terri-toriale. In G. Camassa, A. De Guio and F. Veronese (eds), Paesaggi di potere. Problemi e prospettive. Atti del

Seminario. Udine 1996. Rome, 199–218.

Morris P. 2007. Apollo, Dionysus and Zeus: On the Sacred Landscapes of Ancient Naxos. In B.K. Lampinoudali, Amùmona Erga. Athens, 96-108. MUNZI M. 2004, Circolazione monetaria in contesto rurale:

la Tripolitania tardo antica alla luce delle recenti ricogni-zioni archeologiche lungo l’uadi Taraglat (antica Cinyps),

in Khanoussi M., Ruggeri P., Vismara C. (eds.) L’Africa

Romana XV. Ai confini dell’Impero: contatti, scambi, con-flitti, Roma, pp. 327-342.

Oliverio, G. 1933. Documenti antichi dell’Africa Italiana. Bergamo.

Oliverio G. 1961. Iscrizioni cirenaiche. Quaderni di

Archeologia della Libya 4, 3-54.

Openo W., Reynolds J. 1979. A monumental tomb at Cyrene . Libya Antiqua 15-16 (1978-1979), 227-229. Pacho J.R. 1827. Rélation d’un Voyage dans la Marmarique,

la Cyrénaïque et les oasis d’Audjelah et de Maradeh, Paris,

2 volumes (reproduction anastatique, Marseille, 1979).

Bibliography Paci G. 2003. Iscrizioni della necropoli occidentale

di Cirene , Studi in memoria di Lidiano Bacchielli.

Quaderni di Archeologia della Libya 18, 173-182.

Parisi Presicce, C. 1984. La funzione delle aree sacre nell’organizzazione urbanistica primitiva delle co-lonie Greche alla luce della scoperta di un nuovo santuario periferico di Selinunte. Archeologia Classica 36, 19–132.

Peĉírka, J. 1973. Homestead farms in Classical and Hellenistic Hellas. In M.I. Finley (ed.), Problèmes de la

terre en Grèce ancienne. Paris, 113–20.

Pringle D. 1981. The Defence of Byzantine Africa from

Justinian to the Arab Conquest: An Account of the Military History and Archaeology of the African Provinces in the Sixth and Seventh Centuries. Oxford.

Prontera, F. 2003. Tabula peutingeriana: le antiche vie del

mondo. Florence.

Pugliese Carratelli, G. 1989. I santuari extramurani. In Magna Grecia III. Milan, 149–58.

Purcaro Pagano, V. 1976. Le rotte antiche tra la Grecia e la Cirenaica e gli itinerari marittimi e terrestri lun-go le rotte cirenaiche della grande Sirte. In Quaderni

di Archeologia della Libya 8. Rome, 285–352.

SPAGNULO F. 1996, Documenti dell’Archivio Breccia relativi

alla Cirenaica, in Studi ellenistici VIII, Pisa-Roma, pp.

203-219.

SPAGNULO F. 1997, Ripostiglio da Cirene in un manoscritto

dell’Archivio Breccia relativi alla Cirenaica, in AIIN 44,

pp. 323-348.

Salvini, R., Callegari, I., Ventura, A., and Anselmi, M. 2006. Analisi delle potenzialità di moderne me-todologie di indagine in applicazioni archeologiche: telerilevamento ad alta risoluzione spaziale, GPS differenziale e fotogrammetria digitale terrestre nell’area di Cirene (Libia). In E. Fabbricotti and O. Menozzi (eds), Cirenaica: studi, scavi e scoperte. Parte

I: Nuovi dati da città e territorio. Atti del X Convegno di Archeologia Cirenaica, Chieti, 24–26 Novembre 2003.

Oxford, 35–44.

Raab, H.A. 2001. Rural Settlement in Hellenistic and Roman Crete. The Akrotiri Peninsula. Oxford. Reynolds, J. 1965–67. The Inscriptions of Apollonia.

Libya Antiqua Suppl. 6: 293–334.

Reynolds J. 2000. Bizantine buildings, Justinian and Procopius in Libya Inferior and Libya Superior.

Antiquité Tardive 8, 169–76.

Reynolds, J. and Bacchielli, L. 1987. Catalogo del-le stedel-le funerarie antropomorfe. Cirene e i Libyi.

Quaderni di Archeologia della Libia 12, 489–521.

Roques D. 1987. Synésios de Cyrène et la Cyrénaïque du

bas-empire. Paris.

Roques D. 1988. L’Economie de la Cyrénaïque au Bas- Empire. In G. Barker, J. Lloyd, J. Reynolds (eds),

Cyrenaica in Antiquity. Oxford, 387–94.

Roques D. 1994. Procope de Césarée et la Cyrénaique du 6e.s. ap. J.C. Libyan Studies 25, 259–64.

Ridgway, B. S. 2001. Hellenistic Sculpture, I, The Styles of

ca. 331-200 B.C., Madison, 90-91.

Robinson D.M. 1913. Inscriptions from the Cyrenaica.

AJA 17, 2, 157-200.

Romanelli P. 1939. Il limes romano in Africa. Quaderni

dell’Impero. Il limes romano X. Roma.

Romanelli 1939. Strade della Libia romana. Africa

Italiana,. 25-28.

Romano, D.G. 1998. Urban and rural planning in Roman Corinth. In D.N. Schowalter and S. J. Friesen (eds),

Urban Religion in Roman Corinth. Harvard Theological Studies, Harvard Divinity School, Harvard, 25–59.

Romano, D.G. 2003. City planning, centuriation, and land division in Roman Corinth. In C. K. Williams and N. Bookidis (eds), Corinth. Results of Excavations

Conducted by the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Vol. XX. Corinth, the Centenary. 1986–1996.

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Athens, 279–301.

Roques, D. 1985. L’Economie de la Cyrénaïque au Bas-Empire. In G. Barker, J. Lloyd and J. Reynolds (eds),

Cyrenaica in Antiquity. Oxford: 387–94.

Rosenbaum E. 1969. A Catalogue of Cyrenaican Portrait

Sculture. London.

Sabbione, C., and Schenal, R. 1996. Il santuario di Grotta Caruso. In E. Lattanzi (ed.), Santuari della

Magna Grecia in Calabria. Napoli, 77–80.

Sailer, R. 2000. Status and patronage. CAH XI. Cambridge Saletti C. 1957. Ritratti severiani. Roma.

Salvini, R., Callegari, I., Ventura, A., and Anselmi, M. 2006. Analisi delle potenzialità di moderne me-todologie di indagine in applicazioni archeologiche: telerilevamento ad alta risoluzione spaziale, GPS differenziale e fotogrammetria digitale terrestre nell’area di Cirene (Libia). In E. Fabbricotti and O. Menozzi (eds), Cirenaica: studi, scavi e scoperte. Parte

I: Nuovi dati da città e territorio. Atti del X Convegno di Archeologia Cirenaica, Chieti, 24–26 Novembre 2003.

Oxford, 35–44.

Santucci, A. 2000. Il Santuario delle Ninfe Ctonie. In N. Bonacasa and M.S. Ensoli (eds), Cirene. Milan, 55–56. Siciliano Fr. 2006. Divinità Funerarie Cirenaiche . In

E. Fabbricotti, O. Menozzi (ed.), Cirenaica : studi, scavi

e scoperte I (BAR International Series 1488). Oxford,

Sjöström, I. 1993. Tripolitania in Transition: Late Roman to

Early Islamic Settlement. Aldershot.

Somma, M.C., Fossataro, D. and Menozzi, O. 2010. Lamluda, un insediamento rurale nella chora di Cirene: primi dati di scavo (luglio 2008) (Progetto Lamluda, Libia: survey, GIS e scavi). Temporis Signa.

Rivista di archeologia della tarda antichità e del medioevo

5, 55–74.

Struffolino, S. 2012. L’oasi di Ammone. Ruolo politico

eco-nomico e cultuale di Siwa nell’antichità. Una ricostruzio-ne critica. Rome.

Struffolino, S. 2014. Proprietà Imperiali in Cirenaica alcune considerazioni. Studi Classici e Orietali 60, 349–80.

Struffolino S. 2016-2017. Gruppi etnici, divisioni so-ciali e organizzazione del territorio in Cirenaica tra Batto II e i Tolemei. Dike 19-20, 127-163.

Strželetskij, S.F. 1961. Les kleroi de Chersonesos Taurique.

Tavria. Simferopol.

Stucchi, S. 1967. Cirene 1957–1966. Un decennio di at-tività della Missione Archeologica Italiana a Cirene. Tripoli.

Stucchi, S. 1975. Architettura Cirenaica. Rome.

Todisco, L. 1993. Sculture greche del IV secolo. Maestri e

scuole di statuaria tra classicità ed ellenismo, Milano.

Thorn, J.C. 2005. The Necropolis of Cyrene. Two hundred

years of exploration. Monografie di Archeologia della

Libya XXVI. Roma.

Thorn, J.C., Thorn, D. 2009. A Gazetteer of the Cyrene

Necropolis from the original notebooks of John Cassels, Richard Tomlinson and James and Dorothy Thorn. Studia

Archaeologica 161. Roma.

Thorn J. C., Thorn D. M., Cherstich L. 2008. The ‘Tomb of Grenna’, Cyrene. In Society for Libyan Studies

Annual Report 39, 95-116.

Tsetskhladze, G.R. 1994. Greek penetration of the Black Sea. In G.R. Tsetskhladze and F. De Angelis (eds), The Archaeology of Greek Colonization. Oxford, 111–35.

Tsetskhladze, G.R., and Snodgrass, A.M. 2002. Greek Settlements in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea, BAR International Series 1062. British Archaeological Reports, Oxford.

Valdés Guía, M.2013. Redefining Dionysos in Athens from the Written Sources: The Lenaia, Iacchos and Attic Women. in A. Bernabé, M. Herrero de Jáuregui, A. I. Jiménez San Cristóbal, R. Martín Hernández(eds). Redefining Dionysos, Berlin, 100-118. Vattioni F. 1987. I semiti nell’epigrafia cirenaica. SCO

37, 527-543.

Ward-Perkins, J.B. and Goodchild, R.G. 2003. Christian

Monuments of Cyrenaica. Edited by J. Reynolds.

London.

Wasowicz, A. 1972. Traces de loitissements anciens en Crimée. MEFRA 84, 199–230.

Wasowicz, A. 1999. Le città del Mar Nero. In E. Greco (ed.), La città Greca Antica. Donizelli, Rome, 205–21. Wegner, M. 1971. Das Roemische Herscherbild III, Macrinus

bis Balbinus. Berlin.

Welsby, D.A. 1992. ULVS XXV: the gsur and associated settlements in the Wadi Umm el Kharab: an archi-tectural survey. Libyan Studies 23, 73–105.

White, D. 1984. The Extramural Sanctuary of Demetra and

Persephone at Cyrene, Libya. Final Reports. Philadelphia.

Wiggers, H.B. 1971. Das Roemische Herrscherbild,

Caracalle, Geta, Plautilla. Berlin.

Wilson, A.I. 2004. Cyrenaica and the late antique economy.

Ancient West and East 3.1, 143–54.

Wolff, C. 2000. La legio III Cyrenaica au Ier siècle. In Y. Le Bohec (ed.), Les légions de Rome sous le Haut-Empire. Lyon, 339–340.

ABBREVIATIONS

CIG : J. Franz, Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum III, Berlin 1853.

IGCyr : C. Dobias-Lalou, Inscriptions of Greek Cyrenaica, in collaboration with A. Bencivenni, H. Berthelot, with help from S. Antolini, S.M. Marengo, E. Rosamilia, Bologna (CRR-MM, Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna), 2017, https://igcyr.unibo. it/.

LGPN : P.M. Fraser, E. Matthews et al., A Lexicon of Greek

Personal Names, I (1987) – V B (2014), dont la base de

données est consultable sur le site du LGPN Online, http://www.lgpn.ox.ac.uk/index.html

SECir : †G. Oliverio, G. Pugliese Carratelli, D. Morelli, « Supplemento Epigrafico Cirenaico », ASAA 39-40 (1961-1963), p. 219-375.

SEG : Supplementum epigraphicum graecum 1-25 (1923-1971), Leiden ; 26- (Alphen aan den Rijn, puis Amsterdam).

CJZC : Lüderitz, G. with Reynolds, J. M. (1983) Corpus