PERFORMANCE-BASED BUDGETING:

Understanding practice variation

through the lens of institutional theories

Author

Sara Giovanna Mauro

Supervisor

Lino Cinquini

Tutor

Giuseppe Grossi

PhD in Management

Academic Year 2015/2016

I

School of Advanced Studies - Institute of Management

Performance- based budgeting: Understanding practice variation

through the lens of institutional theories

Thesis for Doctoral Dissertation presented by

Sara Giovanna Mauro

Supervisor Professor, Dr. Lino Cinquini

Institute of Management, Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna

Pisa, Italy

Tutor

Professor, Dr. Giuseppe Grossi

Department of Business Administration and Work Science, Kristianstad

University Sweden

II

I

PREFACE AND ACKNOLEDGMENTS

Doing my PhD has been a demanding but wonderful path, during which I have been privileged to be surrounded by an incredible group of people who have helped me along the way.

I am particularly indebted to my supervisor, Professor Lino Cinquini, and my tutor, Professor Giuseppe Grossi, for their continuous encouragement and support, and for guiding me into the world of academia. Their hard work and successful commitment to research have been sources of inspiration for me.

Without the initial encouragement of Professor Giuseppe Grossi, probably, I would not have even started my PhD. I really thank him for believing in me and constantly supporting my research work, through constructive comments and unmatched advices. I am grateful to Professor Lino Cinquini for his constant guide. He has always being willing to listen to and provide me with his precious teachings, stimulating my research. By working with him, I had the chance to meet and work with Andrea, Cristina and Emilio. Thanks to all of them for sharing knowledge and coffee breaks in a warm and stimulating environment.

During my PhD journey, I had the privilege to spend almost three months in Sweden, at the Kristianstad University. I am thankful to my tutor and to Department of Business Administration and Work Science for this great opportunity. I am particularly indebted to Daniela Argento for her precious comments and detailed feedbacks about my work, for her sincere help and for our lunch talks and inspiring discussions. Giuseppe, Daniela and Giulia made me feel at home during my stay in Sweden with their warm company and contagious vivacity.

I had also the privilege of spending three months at the School of Management, University of Tampere, in Finland. I am indebted to Professor Jarmo Vakkuri for this great opportunity, for his kind help during my stay there, for his support to my research project, and for the constructive and stimulating discussions we had. It has been a real pleasure to work there. I want to thank also Aniina

II

Autero for her friendship and help, without which my data collection would have been much more difficult, and all the other people who helped me and made my stay in Finland incredibly nice, interesting and “adventurous”, in particular Professor Lasse Oulasvirta, Tomi Rajala and Harri Laihonen. Finally, I thank Lotta-Maria Sinervo for her current help.

During my PhD, I have been very privileged to get to know many great people who helped me in learning what doing research means. In this regard, I would like to thank Professor van Helden, from whom I had the pleasure to receive useful suggestions at the beginning of my journey and along the way. His comments have always been a source of inspiration and I really appreciate his help.

I thank all the public administrations, in Italy, Finland, and Sweden, which have made this work realizable.

If I survived my PhD, it has been also thanks to my friends, to Sant’Anna PhD community, and, in particular, to my PhD colleagues and friends who have started with me this journey, Maral, Daniela, Pierluigi, Gianluca and Tommaso. We have shared good and bad times, we have laughed and argued, we have been together despite the distance. PhD has been easier with you. Thanks to all of you.

Above all, the credit for this achievement goes to my family. Thanks to my mom and dad for their unconditional love, to my brothers for being always a stable and safe point of reference in my life, and to their families, to the smiles and hugs of Eleonora, Nada and Lorenzo. Last, but definitely not least, thanks to Tommi, who helped me in handling distances and overcoming obstacles with his patient and faithful support.

My sincere thanks go to all of you!

III

PREFAZIONE E RINGRAZIAMENTI

Il percorso di dottorato si è rivelato essere una esperienza impegnativa ma affascinante. Nel corso degli anni, sono stata circondata da persone che mi sono state vicine, ciascuno in modo differente.

Il mio primo ringraziamento è per il mio supervisor, Prof. Lino Cinquini, ed il mio tutor, Prof. Giuseppe Grossi, per il loro continuo incoraggiamento e supporto, e per essere stati la mia guida nel mondo accademico. Il loro impegno e la loro passione per la ricerca sono stati motivo di ammirazione ed ispirazione per me.

Senza l’iniziale incoraggiamento del Professor Grossi, probabilmente non avrei deciso di iniziare questo percorso ed oggi non sarei qui. Lo ringrazio per aver creduto in me e per aver sempre guidato e supportato i miei lavori di ricerca, con professionalità ed affetto. Ringrazio il Professor Cinquini per essere stato una guida costante, per la sua continua disponibilità ed i sui suoi preziosi insegnamenti e consigli, stimolo per il mio lavoro di ricerca. Lavorando con lui, ho avuto il piacere di conoscere e lavorare con Andrea, Cristina ed Emilio, che ringrazio per la condivisione di consigli e pause caffè in un ambiente stimolante ed accogliente.

Durante il dottorato, ho avuto il piacere di trascorrere tre mesi presso l’Università di Krisitanstad, in Svezia. Sono grata al mio tutor ed al Dipartimento di “Business Administration and Work Science” per questa opportunità e per l’accoglienza riservatami. In particolare, sono in debito con Daniela Argento, per svariate ragioni. Per i suoi preziosi e dettagliati commenti sul mio progetto, per il suo sincero aiuto e supporto al mio lavoro di ricerca, per i pranzi in compagnia e le piacevoli chiacchierate. Giuseppe, Daniela e Giulia mi hanno fatto sentire a casa con la loro solare e contagiosa vivacità.

Ho avuto anche il privilegio di trascorrere tre mesi in Finlandia, presso l’Università di Tampere, “School of Management”. Ringrazio di cuore il Professor Vakkuri, che ha reso possibile questa esperienza. Grazie alla sua disponibilità ed al suo prezioso aiuto, agli utili suggerimenti per il mio

IV

lavoro, ed agli incontri ed alle discussioni avute, motivo di riflessione ed ispirazione. Ringrazio anche Anniina Autero, per l’amicizia e l’aiuto, senza il quale il mio processo di raccolta dati sarebbe stato più difficile. Un grazie a tutti gli altri che mi hanno aiutato ed hanno reso il mio soggiorno in Finlandia una bella esperienza di vita e di lavoro, con episodi avventurosi e divertenti. Grazie al Professore Lasse Oulasvirta, Tomi Rajala and Harri Laihonen. Un ultimo ringraziamento a Lotta-Maria Sinervo, per l’aiuto attuale.

Durante il mio dottorato, ho avuto il privilegio di conoscere molte persone che mi hanno aiutato a comprendere il significato di fare ricerca e ad appassionarmene. In particolare, sono in debito con il Professore van Helden, che ha avuto utili e preziosi commenti per il mio progetto di ricerca all’inizio del mio dottorato e durante il percorso. Gli sono molto riconoscente.

Ringrazio tutte le amministrazioni pubbliche in Italia, Finlandia, e Svezia, per la loro disponibilità e collaborazione.

Se son sopravvissuta al dottorato, lo devo anche ad i miei amici, lontani e vicini, alla numerosa comunità di dottorandi della Scuola che, con la sua compagnia, ha reso piacevole questo percorso, ma soprattutto ai miei colleghi ed amici con cui ho iniziato e vissuto questa avventura, Maral, Daniela, Pierluigi, Gianluca e Tommaso. Abbiamo condiviso momenti facili e difficili, riso e discusso, siamo stati vicini anche quando in città e paesi diversi. Grazie a tutti voi.

Infine, il più grande merito è stato della mia numerosa famiglia, capace di essere presente nonostante i chilometri di distanza. Grazie ad i miei genitori per il loro amore incondizionato e la loro pazienza, ai miei fratelli per continuare ad essere un punto di riferimento sicuro ed affidabile nella mia vita, alle loro famiglie ed ai sorrisi e gli abbracci di Eleonora, Nada e Lorenzo. E grazie a Tommi, per la sua pazienza ed il suo supporto fiducioso, che hanno reso possibile affrontare distanze e difficoltà.

Il mio grazie sincero a tutti voi! Giovanna

V

ABSTRACT

This dissertation examines the variation of a relevant and challenging practice adopted in the public sector worldwide, the so-called performance-based budgeting (PBB). This practice represents an example of the integration of accounting and management changes in the public sector. It can play a pivotal role in the public sector and for public sector organizations because it is built on the use of performance information during the budgeting process and, thus, is expected to meet current challenges of improving, for instance, efficiency and effectiveness, and/or strengthening accountability and transparency. On the other hand, PBB has proven to be challenging and problematic worldwide. The PBB practice, inspired by private sector logics, has been transferred from one context to another, consistently with the international role of the reform movement known as New Public Management (NPM). However, this process has not been neutral and has thus resulted in the practice variation we observe today. Therefore, the current research is mainly interested in investigating the interpretations and applications of the practice and the variation between and across them in different settings in order to answer the following broad research problems: How can PBB vary across contexts? What can explain PBB variation? And what can this variation teach?

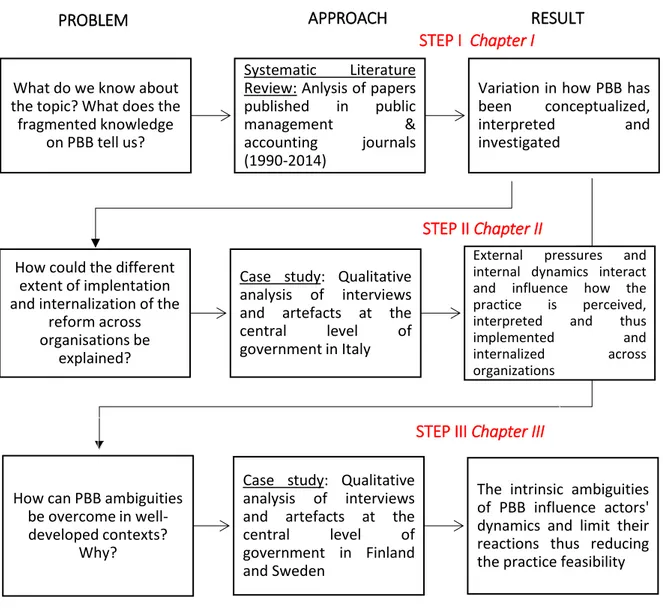

Contrary to the isomorphic expectations of homogeneity across public organizations derived from a strand of the institutional theory, the present study supports the idea that the same practice can vary across contexts, and interprets and explains the reasons for the variation. To fulfil this goal, the research has been structured into three parts, each of which represents a crucial step towards the achievement of the final goal by addressing a narrower and more detailed aspect of the broader problem.

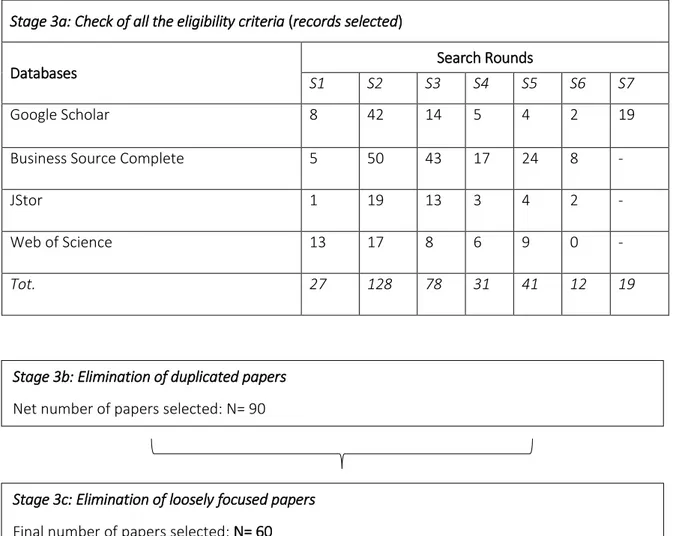

First, the research systematically reviews the existing literature on PBB and identifies gaps and avenues for future research (Chapter I). In order to contextualize and guide the empirical analysis, the starting point has been identified in the analysis of the existing body of knowledge, which has been growing over the last few decades but is still lacking systematization. Two questions have inspired the review: What has previous research on PBB investigated? What else could be

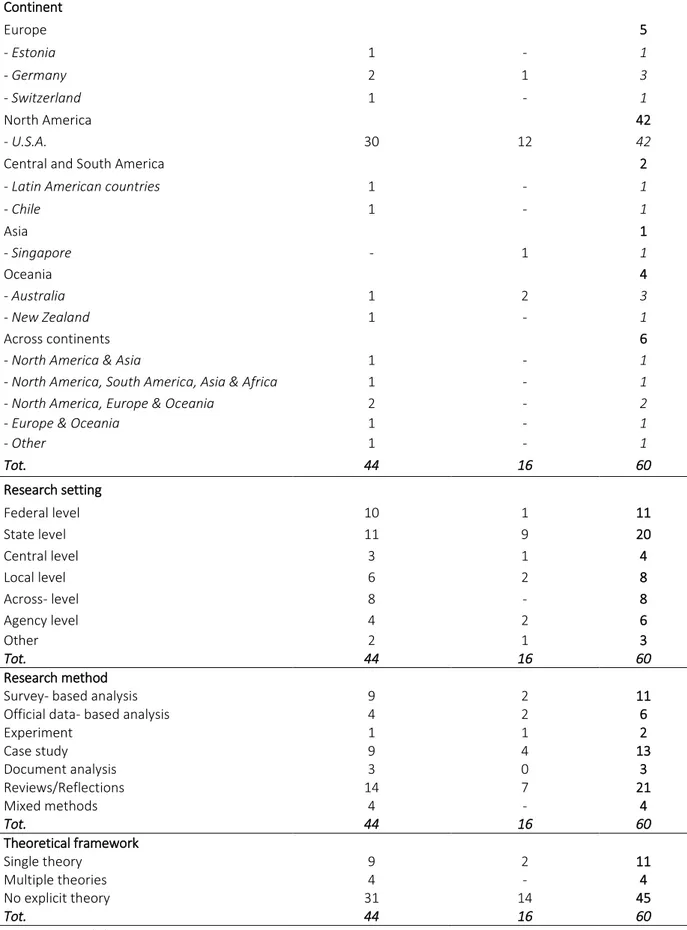

VI

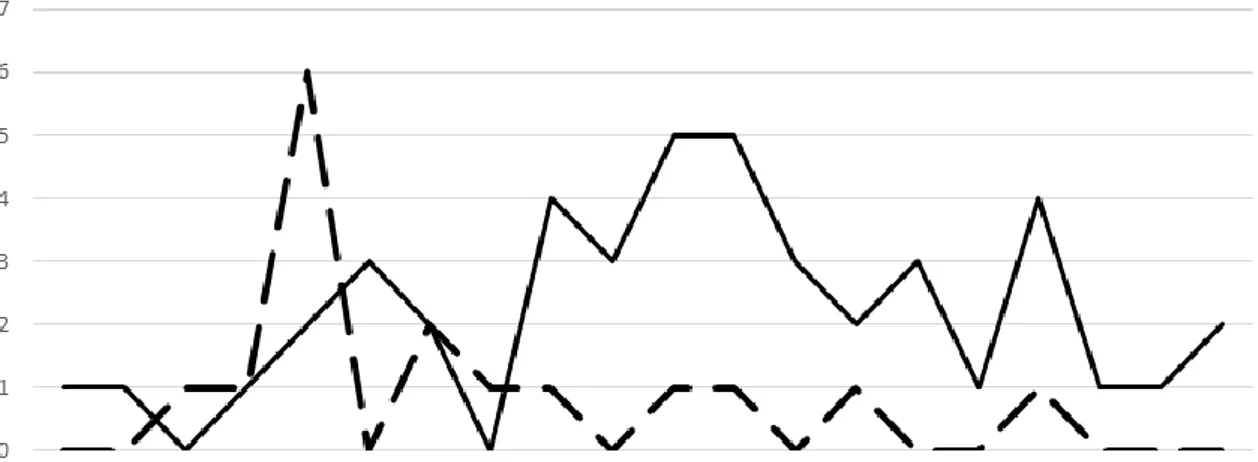

done? The review analyses academic studies published from 1990 to 2014 in the field of public management/administration and accounting and classifies the selected papers (n. 60) through descriptive and conceptual analysis. The analysis has shed light on overlooked and over-investigated areas of research, thus identifying a research agenda.

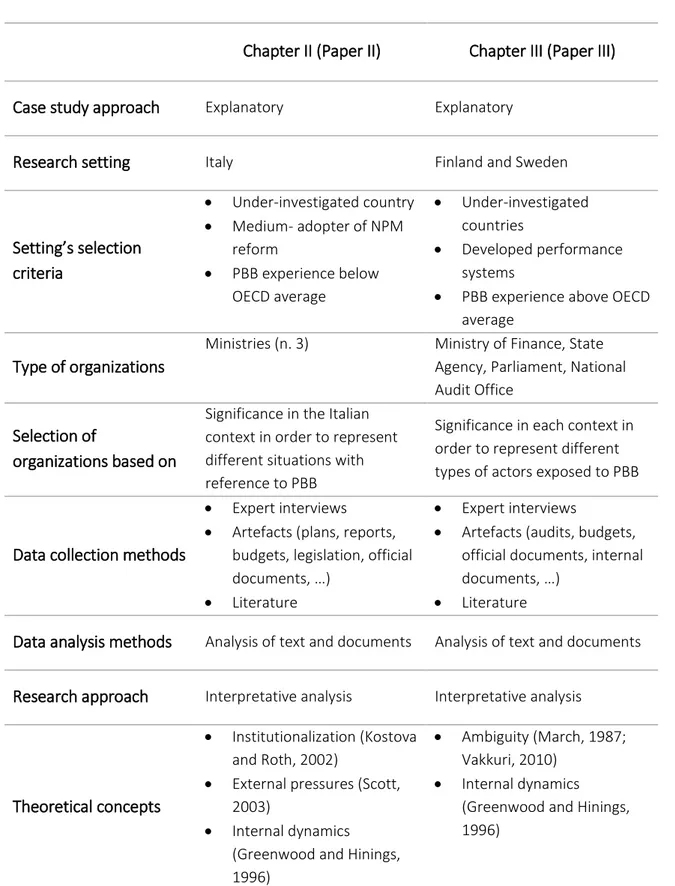

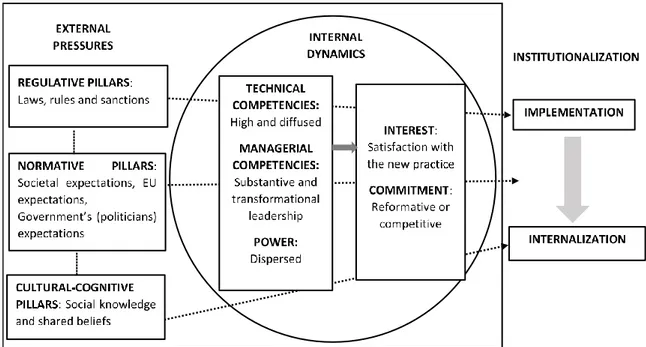

In particular, the findings of the literature review have inspired and guided the consequent empirical analysis (second and third part of the research). Indeed, analysis of the existing knowledge of PBB has pointed out that the reasons for the practice variation across organizations are not still fully explored, while similar challenges faced in adopting, implementing and using PBB have been investigated. Therefore, the second part of the research empirically investigates PBB variation across organizations within a country (Chapter II). In particular, it analyses whether and why PBB can assume different features across three ministries in Italy. The research investigates the interaction between external pressures (regulative, normative and cultural - cognitive) and internal dynamics (value commitment, interest satisfaction, power dependencies, and technical and managerial competences) in order to explain the institutionalization of PBB at the central level of government. The analysis explains the extent to which the practice has been institutionalized in a context where attempts to introduce managerial reforms have been more recent compared to other countries, such as the Nordic countries. By adopting this approach, the research has contributed to the body of knowledge on PBB by demonstrating that organizations influence how the practice of PBB can be implemented and internalized, thus determining variations even within the same national boundaries, because they react differently to similar external pressures.

Finally, the last stage of the research makes a two-fold contribution to the overall work (Chapter III). First, it focuses on the perceptions and reactions of different actors to PBB challenges, thus contributing to this overlooked issue. In order to fulfil this goal, the research investigates PBB at the central level of government in two Nordic countries, Finland and Sweden, purposefully selected because they represent well-developed performance management systems with a long and apparently successful experience with PBB. By adopting this approach, the comparative analysis of

VII

PBB contributes to the overall research by providing a different perspective on explaining practice variation. The research demonstrates that PBB is connoted by intrinsic ambiguities that are often not addressed by the actors exposed to the practice because of their internal dynamics, namely, a low level of commitment, lack of satisfaction with PPB, (on the contrary) a good level of satisfaction with the broad performance system, in addition to technical and managerial problems. PBB as a tool has been demonstrated to be often unfeasible in the public sector and for public sector organizations even in contexts where expectations are higher.

The empirical analysis in Italy, Finland and Sweden was conducted by adopting the case study method as the research strategy, where the results are based on data gathered mainly through semi-structured interviews and analysis of documents. The data have been integrated and analysed in an interpretative way. This choice stems from the topic and goal of the work, namely, analysing a contemporary practice in its own context and providing a sound explanation for its potential variation. Further, the qualitative approach has been considered the most appropriate choice based on the theoretical approach used, since it seems that it is somewhat difficult to quantitatively measure the internal dynamics of organizations.

Keywords: Performance- based budgeting; public sector; practice variation; Italy; Finland; Sweden; central government; institutional theory

VIII

SOMMARIO

La presente tesi esamina la variazione di una rilevante ma complessa pratica adottata nel settore pubblico a livello mondiale, nota con il termine “performance- based budgeting” (PBB). Tale pratica è l’emblema del tentativo di integrare innovazioni contabili e manageriali nel settore pubblico. PBB può giocare un ruolo di grande rilievo prevedendo l’utilizzo di informazioni di performance nell’allocazione delle risorse e rispondendo in tal modo alle attuali sfide del settore pubblico, quali la necessità di incrementare efficienza ed efficacia, e/o rafforzare accountability e trasparenza. La riforma trae ispirazione da logiche manageriali proprie del settore privato e si diffonde nella convinzione di dover realizzare un cambiamento utile per le pubbliche amministrazioni seguendo gli stimoli proposti dal movimento internazionale di riforma noto come New Public Management (NPM). Tale processo di diffusione delle riforme non è stato però neutrale ed è sfociato nella variazione della pratica osservabile oggigiorno. Per tale motivo, la presente ricerca ha come interesse primario lo studio delle differenti interpretazioni ed applicazioni della riforma sviluppate in molteplici contesti al fine di contribuire a rispondere ad un ampio quesito: Come può la pratica di PBB variare da un contesto all’altro e da una organizzazione all’altra? Cosa può spiegare tale variazione? E cosa può tale variazione insegnare?

Contrariamente alle aspettative di isomorfismo ed omogeneità tra amministrazioni pubbliche derivanti da un filone della teoria istituzionale, il presente studio, supportando la tesi in base alla quale la stessa pratica può variare tra amministrazioni pubbliche, interpreta e spiega le ragioni di tale variazione. Al fine di raggiungere tali obiettivi, la ricerca è stata strutturata in tre parti, ciascuna delle quali ha rappresentato un passo fondamentale verso il raggiungimento dell’obiettivo finale attraverso l’analisi di un aspetto specifico del più ampio problema di interesse.

In primis, la ricerca ha sistematicamente analizzato la letteratura esistente in tema di PBB (Capitolo I). Al fine di contestualizzare e guidare l’analisi empirica, il punto di partenza della ricerca è stato necessariamente identificato nell’analisi della letteratura sul tema, che ha conosciuto una

IX

significativa crescita nel corso degli ultimi decenni senza, però, essere accompagnata da sue analisi sistematiche. In particolare, due domande di ricerca hanno guidato lo studio: Cosa è stato studiato fino ad ora in tema di PBB? Cos’altro necessita di essere indagato? La ricerca ha analizzato studi accademici sul tema pubblicati dal 1990 al 2014 nei settori di management pubblico/amministrazione pubblica e contabilità ed ha classificato tali lavori (n. 60) attraverso un’analisi descrittiva e concettuale. Tale studio ha messo in luce gli aspetti maggiormente investigati e quelli, al contrario, che necessitano ulteriori approfondimenti, permettendo così di elaborare una agenda di ricerca.

In modo specifico, i risultati dell’analisi della letteratura hanno ispirato e guidato la conseguente analisi empirica, corrispondente alla seconda e terza fase della ricerca. Difatti, l’analisi della letteratura ha evidenziato come le ragioni per cui la pratica può variare tra organizzazioni non siano state del tutto analizzate, mentre significativa attenzione è stata prestata alle simili sfide affrontate dalle organizzazioni pubbliche nell’adozione, implementazione e nell’utilizzo della riforma. Per tal motivo, la seconda parte della ricerca ha studiato empiricamente la variazione della pratica in tre organizzazioni all’interno di un Paese (Capitolo II). In particolare, la ricerca ha analizzato se e perché la pratica di PBB può assumere caratteristiche differenti in tre ministeri in Italia. La ricerca analizza l’interazione tra fattori esterni (pressioni regolative, normative e cognitive) ed interni (dedizione, soddisfazione, potere, capacità di azione) al fine di spiegare l’istituzionalizzazione della pratica di PBB a livello centrale di governo. L’analisi ha spiegato il livello a cui la pratica è stata istituzionalizzata in un contesto dove i tentativi di introdurre riforme manageriali sono stati più recenti rispetto ad altri Paesi, come i Paesi Nordici. Adottando questo approccio, la ricerca ha contribuito allo studio della pratica di PBB dimostrando come le organizzazioni pubbliche possano influenzare la pratica stessa, determinando la sua variazione anche all’interno dei confini nazionali, a seguito delle proprie dinamiche interne.

A questo proposito, l’ultima fase della ricerca (Capitolo III) ha contribuito in un duplice modo alla tesi. In primis, la ricerca si è focalizzata sulle percezioni e reazioni di attori differenti alle sfide di

X

PBB al livello centrale di governo, contribuendo ad indagare questo aspetto sino ad ora meno investigato. Al fine di raggiungere tale obiettivo, la ricerca ha investigato la pratica di PBB a livello centrale di governo in due Paesi Nordici, Finlandia e Svezia, selezionati poiché rappresentativi di sistemi di gestione della performance sviluppati e con una lunga esperienza sul tema. Attraverso questo approccio, l’analisi ha contribuito alla ricerca fornendo dati empirici da aggiungere al caso italiano nella spiegazione della variazione della pratica. La ricerca dimostra che PBB è caratterizzato da intrinseche ambiguità che sono identificate dagli attori coinvolti ma spesso non affrontate a causa di specifiche dinamiche interne, ed in particolare a causa di un basso livello di dedizione, di mancanza di soddisfazione con la nuova pratica e, al contrario, un buon livello di soddisfazione con il più ampio sistema di misurazione della performance, oltre che per problemi tecnici e manageriali. La pratica di PBB si rivela essere spesso uno strumento non completamente concretizzabile nel settore pubblico e per le amministrazioni pubbliche, anche in contesti dove le aspettative sono più alte.

L’analisi empirica in Italia, Finlandia e Svezia è stata condotta adottando il case study come strategia di ricerca. I risultati sono basati su dati raccolti tramite interviste semi-strutturate ed analisi documentale, poi integrati ed analizzati in modo interpretativo. Questa scelta trova giustificazione nell’argomento e nello scopo del lavoro, ossia studiare una pratica attuale nel suo contesto di applicazione al fine di spiegare in modo convincente la sua potenziale variazione, e nella necessità di studiare le dinamiche interne delle organizzazioni, variabili altrimenti difficilmente misurabili attraverso approcci quantitativi.

Parole chiave: Performance- based budgeting; settore pubblico; variazione della riforma; Italia; Finlandia; Svezia; livello centrale di governo; teoria istituzionale

XI

Table of contents

INTRODUCTION

1

1. Background and motivation for the study 2

2. Research questions and aims 11

3. Theoretical framework 15

4. Research methodology and method 20

5. Research process and structure of the thesis 24

6. References 29

7. List of figures/tables 36

CHAPTER I

A SYSTEMATIC LITERATURE REVIEW ON PERFORMANCE-BASED BUDGETING

37

1. Introduction 38

2. Review design 39

3. Descriptive analysis 44

4. Thematic analysis: “What has been done?” 50

5. Discussion: “What could be done?” 57

6. Conclusions 64

7. References 67

XII

CHAPTER II

THE VARIATION OF PERFORMANCE- BASED BUDGETING WITHIN A COUNTRY:

THE ITALIAN CASE

77

1. Introduction 78

2. The institutionalization of PBB 79

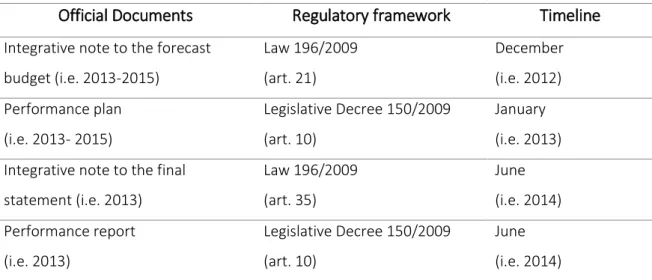

3. PBB in the Italian context 86

4. A multiple case study across Italian ministries 91

5. Implementation and internalization of PBB 93

6. Conclusions: Variation within a country 101

7. References 104

8. Appendix and List of figures/tables 109

CHAPTER III

PERFORMANCE- BASED BUDGETING ACROSS TWO NORDIC COUNTRIES:

FINLAND AND SWEDEN

111

1. Introduction 112

2. PBB ambiguities and actors’ dynamics 114

3. Research method and setting 120

4. Research background 124

5. Case analysis 129

6. Discussion and conclusions: Big expectations for poor results 144

7. References 147

8. Appendix and List of figures/tables 153

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

155

1. An overview of performance- based budgeting variation(s) 156

2. What can this practice variation teach? Suggestions for future research 166

3. References 169

1

INTRODUCTION

This introductory chapter is firstly designed to provide the background and

motivation for the research by contextualizing a specific performance-oriented practice, the

so-called performance- based budgeting (PBB), which is the object of the study, within the

broader context of reforms undertaken by the public sector over the last few decades.

In particular, the first paragraph sets the ground of the research by describing the

main overarching paradigm according to which PBB has spread worldwide and by illustrating

its main components, performance and budget. These considerations enlighten the broad

motivation for the study.

Then, the chapter explains the research questions and aims, and illustrates

theoretical approach, research methodology and methods adopted to fulfil the overall goal.

Finally, the chapter provides a description and graphical representation of the

research process and the structure of the thesis.

2

1. BACKGROUND AND MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY

The New Public Management paradigm

Public management, defined as the “study and practice of design and operation of arrangements for the provision of public services and executive government” (Hood, 2005, p. 8), could and should be recognized as a relevant field for “creative developments” in management theory and practice (Metcalfe, 1993, p. 292). Indeed, several challenges have shaken the public sector over the last decades, calling for reforms and innovations. In this regard, although paradigms and reform trajectories can provide only an approximate and simplified representation of the different scenarios across countries, it is useful to identify them in order to explain the evolution of the public sector and contextualize its main changes.

The old model of public administration, labelled traditional bureaucracy (Hughes, 1998) or ancient regime (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2011), is the result of the classical public administration (Wilson, 1887) and Weberian bureaucratic principles, the most recurrent features of which are the separation of politics and administration, hierarchical command, centralized bureaucracy, central planning and compliance with rules. This model has been critiqued (e.g. Osborne & Gaebler, 1992) for being unsuitable to address the current challenges, and this has paved the way for new reform trajectories. Since the end of the 1980s, the movement called “New Public Management” (NPM) (Hood, 1991) has been developed to introduce a managerial approach for governing the public sector.

NPM is a “loose term” that encompasses multiple concepts and tools (Hood, 1991, p. 3). Indeed, it is a complex and innovative mix of old and new reforms inspired by several theoretical perspectives, from the public choice theory to management theory, and from the classical and neo-classical pubic administration theory to the principal agent theory (Gruening, 2001). Although it is characterized by many concepts and cross-country differences, it has a “claim for universality” that can be identified in its major components (Hood, 1991), which are built around the redefinition of the boundaries of government (e.g. privatization), the reshaping of the structure of the public sector

3

(e.g. decentralization) and the adoption of a managerial approach by focusing on results. This shift from a focus on input to a focus on results has led to an “increase in the amount of information and change in the type of information generated and used for budgeting and management purposes” (Kristensen, Groszyk, & Buhler, 2002, p. 10). This result orientation represents an undisputed and relevant component of NPM. Indeed, a set of managerial and institutional reforms has gradually been introduced to make the public sector more business-like (Jansen, 2008). Consequently, several criticisms have been raised, in particular by who states that the gap between public and private sectors increases the likelihood of having symbolic managerial practices in the public field (Lapsley, 1999). Therefore, NPM has been criticized for its poor implementation (Arnaboldi, Lapsley, & Steccolini, 2015) and it has lost ground over the years (Lynn, 1998). Pollitt and Bouckaert (2004) interpreted the inevitable reactions to this concept as a consequence of the end of neo-liberalism and the need for new paradigms.

New reforms are thus elaborated as reactions to NPM negative effects and, at the same time, answers to new needs. The context within which public sector organizations exist is continuously evolving, and economic, political, and societal pressures are continuously redefining public needs and expectations. Therefore, new approaches to reform have been developed. A more recent paradigm has been built on the concept of public value, as elaborated by Moore in 1995 through his book “Creating Public Value”, which emphasizes on the final aim of the managerial work of public sector organizations. However, the Public Value paradigm is not without problems, as previous reforms. Over the last few years, it has attracted significant attention from scholars, who have tried to cope with the challenging definition and measurement of public value and the consequent gap between its theory and practice (Guthrie & Russo, 2014). Another recent reform movement considered the “shadow of the future” (Osborne, 2010, p. 6) is the so-called New Public Governance, which focuses on contemporary issues and emphasises an inter-organizational perspective through collaboration between public, private and mixed public-private organizations.

4

In this context, NPM has been considered a transitory state from the traditional model to more recent ones (Osborne, 2010).

However, the process of change does not follow a linear path in the public sector, and multiple paradigms can coexist (Hyndman et al., 2014). Although more recent paradigms are becoming widespread, a recent review of the literature on NPM (de Vries & Nemec, 2013) has demonstrated that the ideas of NPM might be still alive and reflected in different tools. Despite it is still an unresolved concern whether NPM can work or cannot, an optimist and recent review shows the positive impact NPM can have on public organizations’ performance (Dan & Pollitt, 2014). In particular, performance management is one of the NPM components that has attracted the greatest attention, and has thus become a part of modern governance arrangements (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2004) and represents a priority in the agenda of many public sector organizations. In this context, it is of utmost importance that public management, administration and accounting scholars examine performance management, since it has been dominating public sector organization agendas for a long time (van Helden, Johnsen, & Vakkuri, 2008).

Performance, performance measurement and performance management

The first key concept of managerial innovations introduced in the public sector, including performance-based budgeting (PBB), is performance. Although specific themes and devices have characterized each wave of reform, performance has remained a permanent feature (Talbot, 2005).

Performance is not a new term. It has preceded the development of NPM and will continue to thrive even after it (Kettl & Kelman, 2007), since it has paved the way to the development of a real movement and a proper agenda (van Dooren, Bouckaert, & Halligan, 2010). Despite its long existence, or maybe because of it, performance is a multi-dimensional and multifaceted concept, employed with different meanings and for different purposes. Performance is considered as a “buzz-word”, according to Pollitt (1986, p. 315), or even “the great unknown”, according to van Dooren,

5

Bouckaert, and Halligan (2010, p. 16). According to these latter scholars, performance can be defined from two main points of view. Firstly, performance can be considered the result of a production process whereby inputs are allocated to produce outputs and generate outcomes. The linkages between these different elements are measured in terms of Economy, Efficiency and Effectiveness, the well-known 3 E’s model. The second approach interprets performance as the realization of public values. In this regard, two sub-sets of interpretations have been developed. The first approach sees performance as a public value, while the second approach considers performance and values as distinct concepts, where public values are the reference framework against which performance is measured. Therefore, performance can be defined from a broad perspective, including not only the three E’s, but also extensiveness, acceptability, equity, fairness, and many others (Pollitt, 1986).

A direct consequence of the broad set of interpretations of performance is the difficulty involved in measuring it. Indeed, the different approaches to the definition of performance influence its operationalization through the elaboration of performance measures, indicators, and targets. In addition, the operationalization of performance is influenced by the different levels (Bouckaert & Halligan, 2008) or foci (Talbot, 2005) at which it can be discussed—at the macro level (government-wide performance), the meso level (policy sector, a network or a chain of events), and the micro-level (individual organizations). The set of activities designed to quantify performance is known under the label of performance measurement, one of the most resilient aspects of the NPM reforms (Modell, 2004). The measurement of performance is not new but has become highly important under NPM and has attracted considerable attention (Cavalluzzo & Ittner, 2004; Modell, 2004; van Dooren, 2005; van Helden, Johnsen, & Vakkuri, 2008). Under NPM, quantitative information has been introduced on a government-wide scale, on an international scale and in all management functions (van Dooren, 2008). Therefore, an industry of performance measurement has been created (Johnsen, 2005) in light of the myth of quantification (Modell, 2004).

However, this measurement orientation is not enough to guarantee the effectiveness of performance systems. Indeed, performance measures should be elaborated and discussed in order

6

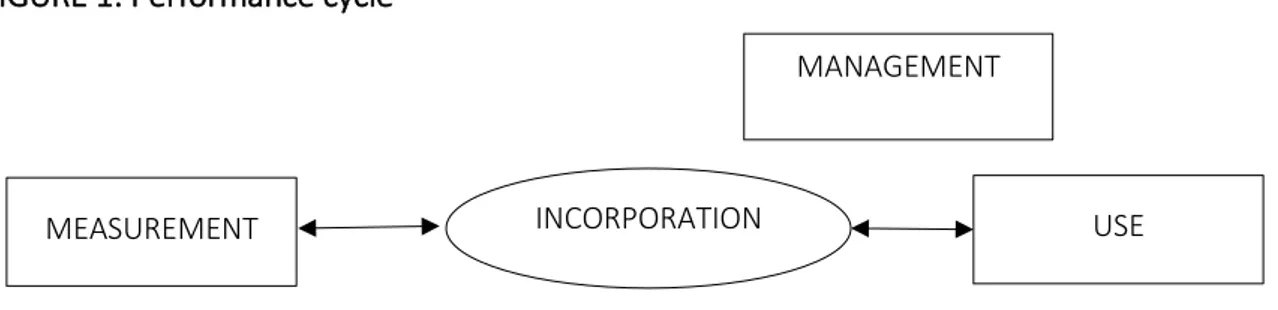

to produce information that could be integrated and used by the organizations. These latter operations correspond to what is labelled as “performance management”, broadly defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as the set of “corporate management, performance information, evaluation, performance monitoring, assessment and performance reporting” (OECD, 2005, p. 95). Therefore, a performance cycle could be built on the logical sequence of these different activities, as depicted in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1: Performance cycle

Source: Adapted from Van Dooren, Bouckaert and Halligan 2010, p. 6

The crucial step of this cycle is represented by the “use” dimension. Indeed, to assess the success or failure of a performance initiative, it is essential to study the use of performance information (van Dooren, 2008), without which real performance management cannot occur (Vakkuri, 2010). For this reason, PBB is the focus of the present study, because it is built on the use of performance information, from which both its potential contributions and its current challenges are derived.

The use of performance information is less formalized compared to performance reporting and, thus, more difficult to investigate. A great amount of research has focused on the issue of measuring performance and, broadly, managing it. More recently, scholars have investigated the production and misuse of performance information and have paid attention to its use (de Lancer Julnes & Holzer, 2001; Grossi, Reichard, & Ruggiero, 2016; Jansen 2008; Liguori, Sicilia, & Steccolini, 2012; Moynihan & Pandey, 2010; Saliterer & Korac, 2013; Taylor, 2009).

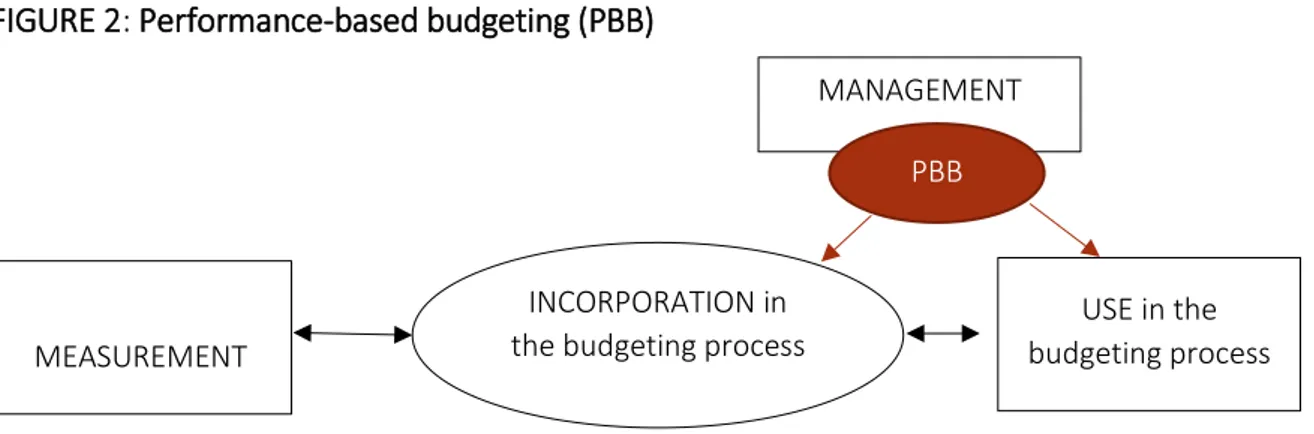

MEASUREMENT INCORPORATION USE

7

There are different types of uses of performance information and different purposes for using performance information (Behn, 2003; Talbot, 2005). Moreover, the intensity of use depends on its type and on the users, as a recent literature review on performance management demonstrates (van Helden & Reichard, 2016). According to Behn (2003), performance measures can be used to evaluate, control, budget, motivate, promote, celebrate, learn and improve. Among these managerial purposes, the improvement of performance is considered as the overall final goal. Therefore, PBB occurs in the performance cycle as a specific realization of performance management (Figure 2). This practice consists of the following three steps: measurement of performance, its integration, and its use during the budgeting process. Therefore, budgetary use can be considered instrumental to achieving broader goals, such as the improvement of efficiency and effectiveness and/or the strengthening of accountability. Determining the final purpose of PBB and its specific features can change from context to context. As underlined by the previous considerations, performance poses several questions that are open to a wide set of potential answers. Consequently, practices such as PBB, built around this key concept, should handle different challenges connected to each step of the process.

FIGURE 2: Performance-based budgeting (PBB)

Source: Adapted from Van Dooren, Bouckaert and Halligan 2010, p. 6 MEASUREMENT

USE in the budgeting process INCORPORATION in

the budgeting process

MANAGEMENT PBB

8

Performance- based budgeting: Key integration between performance and the public

budget

Scholars and practitioners have paid attention to the budgetary use of performance information for a long time, in order to improve the functioning of the public budget.

The budget is the main economic policy document of the government, describing how public resources will be used to meet policy goals (OECD, 2016). Indeed, since it is a plan of action for a specific period, it is an important device for managers. At the same time, politicians authorize the use of public money through the budget, which makes it an important political document. For the budget to become a plan of action and an authorization document, it is necessary to follow a process that consists of several activities, which can be grouped into four main stages: formulation, approval, execution, and audit. These different steps can be linked to the different functions of a public budget, such as planning, management, and control (Schick, 1966). Each function is associated with its own challenges and can be the object of specific changes and interventions according to the perceived needs. Usually, two external pressures have guided budgeting reforms: the call for restraining the growth of expenditure for macro-economic reasons and/or the call for increasing efficiency and effectiveness (Bouckaert & Pollitt, 2004). A theoretical and ideal solution to these two problems lies in the integration of financial management with the management process (Pollitt, 2001). Indeed, as Pollitt clarifies, budgeting and management activities of the government take place within the resource management system, which is designed to (a) maintain fiscal discipline by avoiding over-spending, (b) guarantee allocative efficiency by aligning resources with priorities, and (c) encourage technical efficiency through a strong focus on the use of resources (Pollitt, 2001). Consequently, the budget has become linked with other processes, such as planning and performance management, especially over the last decades, which have seen the introduction of managerial and institutional practices in the spirit of NPM. Furthermore, the current period of crisis has emphasized the need for interventions (Peters, 2011), which require governments to rethink the content, role and structure of their budget. In this regard, PBB has re-attracted the attention of scholars and practitioners as a

9

practice suitable for linking financial management and management processes, and, thus, as a component of the set of “managing for results” reforms (Diamond, 2005; Robinson, 2007). Therefore, PBB could be expected to influence the different functions of the budget and the different steps of the budgeting cycle in an attempt to provide a solution to current problems and overcome the limits of traditional systems.

The traditional public budget, which is cash-based, has a line-item structure, and contains financial information (MacNab & Mitchell, 2014; Jansen, 2008), has proved unsuitable in the face of the challenges of the public sector. The incremental budget, according to which the previous year’s budget is the starting point for the coming year (Wildavsky, 1964), could have worked in times of growth, but it has a number of limitations, especially during retrenchment times. The old but still relevant question remains unanswered: “On what basis shall it be decided to allocate x dollars to activity A instead of activity B?” (Key, 1940, p. 1138). Therefore, dissatisfaction with the traditional systems and the input-based structure has led to a move towards an output- or outcome-oriented system, which is reflected in the definition of PBB.

The concept of performance budgeting was adopted in the USA by the Hoover Commission and paved the way for several reforms, such as Planning Programming Budgeting Systems, Management by Objectives and Zero- based budgeting. These concepts were transferred to other countries in the Anglo-Saxon world and outside, but they were not always successful. In the 1980s, the fiscal crisis placed renewed emphasis on the need for reforming the budget, and under the influence of NPM, performance budgeting re-emerged. Therefore, PBB is not a new concept, but still represents an actual topic. Performance budgeting, PBB, and results-oriented budgeting are some of the names commonly given to the use of performance measures for informing budgetary decisions (Behn, 2003; Jordan & Hackbart, 1999; Kong, 2005). PBB is designed to obtain information about results and use it in the budgeting process and in the allocation of resources (Budding, Grossi, & Tagesson, 2015). According to a broad definition provided by Robinson (2007), PBB refers to

10

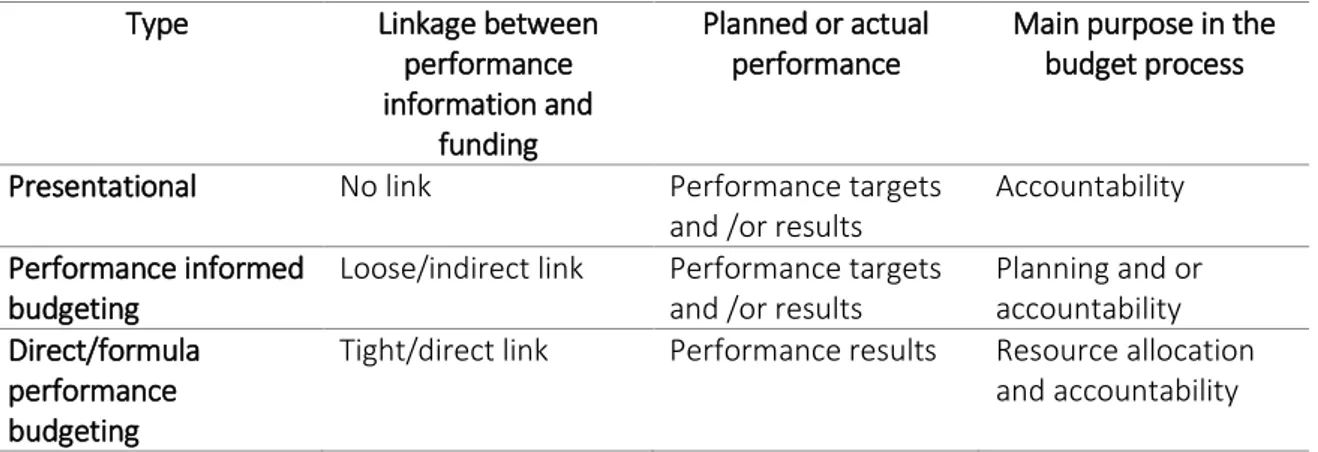

“public sector funding mechanisms and processes designed to strengthen the linkage between funding and results (outputs and outcomes), through the systematic use of formal performance information, with the objective of improving the allocative and technical efficiency of public expenditure” (p. 1). This definition paves the way for several interpretations about the kind of performance information that should be produced and used, the meaning of systematic use, and the type of linkage that should be built between funding and results. In this regard, the OECD (2007) has classified PBB into different categories according to the degree of complexity, as summarized in the following table (Table 1). In the first type of PBB, performance information is present in the budgeting document; in the second type, the results only have a loose influence; and in the last type, PBB is built on a direct and rigorous linkage between funding and results. The differences in the type of linkage are related to different types of performance and the purpose of use.

TABLE 1: Performance- based budgeting: A taxonomy

Type Linkage between

performance information and

funding

Planned or actual performance

Main purpose in the budget process

Presentational No link Performance targets

and /or results

Accountability Performance informed

budgeting

Loose/indirect link Performance targets and /or results

Planning and or accountability Direct/formula

performance budgeting

Tight/direct link Performance results Resource allocation and accountability

Source: OECD, 2007, p. 21

As a reform, PBB has the potential to improve the performance of public organizations, but at the same time, it involves significant challenges. It is difficult to standardize its definition (Joyce, 2011; Smith, 1999), but its implementation is even more difficult, as it may involve issues caused by organizational, economic and political factors. Different countries and organizations, through a variety of approaches, models and results, have adopted the practice of PBB. Moreover, top-down

11

versus bottom-up approaches, output-oriented versus outcome-based, comprehensive versus specific approaches have also been developed (Talbot, 2005). The challenges connected with PBB are exacerbated according to each step of the performance cycle and the needs and features of the public budget. The principle of “let the managers manage” that inspires many NPM reforms, including PBB, calls for the need to contextualize NPM with reference to the public budget, thus generating several trade-offs and challenges.

The long and controversial history of PBB is the topic of huge debates. Moreover, PBB has been alternated with similar budgeting reforms, which have created doubts about the novelty of this practice (Lu, 1998; Martin, 1997). Moreover, during the years, there have been many up and down periods that have undermined its credibility (Hou et al., 2011; Pitsvada & LoStracco, 2002). Currently, there is still debate about whether the current trend of PBB is well designed (Lu, Willoughby, & Arnett, 2011) and whether it can perform well.

In light of these considerations, it is possible to conclude that PBB may solve the problems faced by public sector organizations when new practices are introduced, but at the same time, it poses new and specific challenges that require further reflection about reforms in the public sector. In this context, performance information appears to be essential, as the use and usefulness of performance information are controversial issue.

2. RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND AIMS

The present research is built on the integration of two actual and relevant concepts, performance and budget. Performance is a major preoccupation of public sector organizations, and among its applications, the budgetary purpose still represents one of the most challenging issues. Budgeting is central for public organizations, but it has been investigated and under-theorized, as a recent review of the literature on the topic has pointed out (Anessi-Pessina, Barbera,

12

Rota, Sicilia, & Steccolini, 2016). Therefore, there is a general need to investigate the public budget and, in particular, integrate it with the relevant current reforms built on performance, in order to understand the state of these recent reforms and identify future developments. The integration of these two aspects represents the practice of PBB and is the focus of this thesis.

The PBB practice could be extremely relevant because it is based on the use of performance information during the budget process and not simply on the production and reporting of performance information. A significant part of previous works on the topic has stressed on the challenges and criticalities linked to the practice. Consequently, there is some criticism and scepticism about this topic. More than a decade ago, Pitsvada and LoStracco published a work entitled “Performance budgeting—the next budgetary answer. But what is the question?” (2002). Another question posed was “Is PBB useful for public sector organizations to cope with the current problems or is it only old wine in a new battle?” (Martin, 1997). Is it destined to fail again as in the past and as occurred with other budget reforms, while traditional budget lasts (Wildavsky, 1978)? With respect to these considerations, the current research has used a different approach.

The current analysis does not attempt to understand what makes this practice different or similar to previous reforms or question its usefulness on this basis. Neither does this analysis underline its failures in the past or criticize its resilience. Instead, the current analysis assumes PBB to be a starting point rather than a defined and final answer to existing problems. PBB is part of the taken-for-granted performance management system in the public sector, and despite its intrinsic challenges, it has been adopted worldwide. In this context, the possibility of making PBB a useful and feasible tool depends on the context in which it is introduced and used. Similar reforms have taken place in many countries, but context-related changes call for comparative studies. Therefore, through the case study approach, the current research investigates PBB in several settings in order to answer the following broad research questions:

13

RQs: How can PBB vary across contexts? What can explain the variation in PBB? What can this variation teach us?

According to the definition of the Oxford English Dictionary, “variation” is the “fact of varying in condition, character, degree, or another quality; the fact of undergoing modification or alteration, specifically within certain limits”. According to this comprehensive definition, the research investigates several aspects with respect to which PBB can vary, including labels and definitions and the extent of implementation and use. The variation between organizations and between official requirements and the practice adopted by each organization is investigated here.

Different ways of defining and thus implementing the practice do not necessarily represent a failure, but they could be considered as the solution adopted by organizations to the problems posed by the practice itself and to the pressures beyond its adoption. The worldwide experiences provide evidence that multiple answers exist in multiple contexts, but they can exist also within the same context. However, among these answers, there is not one best solution or ‘no one size fits all’ approach. In this context, the principal objective of the research is to investigate PBB practice in order to improve its understanding by interpreting its variation across and within countries. In particular, the research is focused on studying the variation in the extent of implementation and use of PBB and on finding out the reason for the variation at the organizational level.

Given the lack of theorized research in the field, this research investigates the extent of implementation and the use of the practice in multiple countries through a combination of theoretical concepts drawn from the institutional theory. To explain why and how the practice can become a successful tool in the public sector and for public sector organizations, the research focuses on organizational reactions to external pressures and to PBB intrinsic challenges by seeking sound explanations for the behaviours of organizations. In this regard, by analysing PBB variation, this study seeks to interpret whether the variation is relevant and what can be learnt from it.

14

The work sheds new light on PBB through a systematic review of the previous research on the topic (Chapter I) and through case studies (Chapter II and III) designed to collect and analyse relevant data at the central level of government in different contexts, in order to examine the reactions to the pressures and challenges related to PBB.

In particular, Chapter I aims at building the foundation for the research by addressing two research questions:

RQ1a: What has been done? RQ1b: What could be done?

The review is thus designed to systematize the studies on PBB in order to underline what areas have been investigated up to now and how (RQ1a), and what areas have been overlooked and thus call for further investigation (RQ1b).

Chapter II analyses the potential variation of PBB across organizations in the same country. It investigates the process of institutionalization of PBB at the central level of government in Italy by studying the interaction between external and internal pressures in three ministries, and addresses the following research questions:

RQ2a: How do external pressures influence PBB institutionalization when they are not fully aligned? RQ2b: How do internal dynamics influence the interpretation of external pressures, and thus, the process of PBB institutionalization?

By answering these questions, the research aims at explaining PBB variation across organizations that is a consequence of the ministries’ different internal dynamics in response to similar external pressures.

Finally, Chapter III focuses on the ambiguities of PBB and investigates how and why actors exposed to the practice react to challenges by overcoming, or not overcoming, them and thus making, or not making, PBB a feasible and useful tool. The analysis collects multiple lines of evidence

15

at the central level of government in two countries, Finland and Sweden. The research questions are as follows:

RQ3a: What are the main types of ambiguities perceived by various groups of actors? RQ3b: How and why do actors react to PBB challenges?

Through this approach, the research can investigate whether and why variation exists in addressing PBB ambiguities in multiple contexts thus influencing the extent of implementation and the use of the practice.

3. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Many models of performance have been developed in the public sector, but few of them have a clear theoretical explanation or have been empirically validated. On the contrary, several existing theories can contribute to understanding and explaining performance, as public choice, institutional economics, and the new institutionalism (Talbot, 2005). In particular, the institutional theory is dominant within organization theory (Greenwood et al., 2011), and is one of the major approaches in public sector management accounting (van Helden, 2005). The current research adopts a combination of concepts that are mainly drawn from the institutional theory in order to interpret and explain why PBB can vary across contexts and whether this variation is meaningful. Indeed, this theory represents a useful approach to study organizational practice, as discussed in this section.

The institutional theory is not one unique theory, but a complex theory that has undergone changes over time, thus resulting in the creation of a broad and wide set of concepts and ideas. As stated by Lawrence et al. (2011), although it is a dominant approach, it “is creaking under the weight of its own theoretical apparatus” (p. 52). The institutional theory dominated research in social science from the 1880s to the 1920s, and after a period of eclipse, interest in it was renewed in the 1970s (Scott, 2014). In particular, in 1977, two seminal papers (one written by Meyer and Rowan and one written by Zucker) introduced the so-called New Institutionalism Sociology (NIS). NIS rejects

16

the rational actor model of an organization, and instead focuses on the behaviour of organizations when they are motivated to act in order to seek legitimacy. In the initial development of this theoretical thinking, Meyer and Rowan focused on its macro dimensions (the institutional sources of formal structures), while Zucker focused on the micro dimensions by stressing on the relevance of cognitive beliefs. Over subsequent years, several other authors, such as Scott and Powell, strongly contributed to the development of new institutionalism in the organizational analysis, which flourished over the years and is still the object of development and enrichment. This approach provides an interesting lens through which it is possible to interpret and explain public sector reforms and, in particular, performance-oriented practices such as PBB, as explained below.

Performance management, broadly interpreted, has become a myth in the public sector worldwide over the last few decades. The notion of myth is popular among institutionalist theorists. Indeed, according to Meyer and Rowan (1991), institutionalized techniques and programs work as powerful myths, as they are taken-for-granted techniques or programs suitable for achieving legitimacy since there are shared meanings and understanding associated with them. The public sector is highly institutionalized and, indeed, the proliferation of these rationalized myths is among the causes of its bureaucratization (Meyer & Rowan, 1991). In order to gain legitimacy, organizations tend to conform to rationalized myths in society about what is appropriate (Boxenbaum & Jonsson, 2008). Therefore, the adoption of institutionalized techniques is often ceremonial and contradicts the purposes of efficiency and effectiveness, which results in loose coupling of the techniques with organizations (Meyer & Rowan, 1991).

Specifically, to achieve legitimacy, organizations tend to adopt similar procedures through a process known as isomorphism, which is “a constraining process that forces one unit in a population to resemble other units that face the same set of environmental conditions” (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983, p. 149). In particular, DiMaggio and Powell (1983) identified three types of isomorphism, according to the origin of the process: coercive, mimetic and normative. Coercive isomorphism

17

implies that organizations act in response to pressures from the coercive authority. Uncertainty or poor understanding can be the cause of mimetic isomorphism, according to which organizations model themselves on others. Finally, normative isomorphism stems from professionalization and from the criteria of proper behaviour. Therefore, NIS focuses on explaining how organizations try to achieve legitimacy in social terms. These three mechanisms are linked to the three pillars identified by Scott (2003): the regulative, normative and cultural- cognitive pillars. The regulative pillar refers to the role played by regulatory processes in the form of rule setting, monitoring, and sanctioning activities. Therefore, the regulative pillar is manifested through coercive mechanisms. The normative pillar encompasses both values and norms, which describe desirable actions and how they should be done, respectively. This pillar acts via normative mechanisms. Finally, the cultural-cognitive pillar represents the shared conceptions that create the “frame through which meaning is made” (Scott, 2014, p. 67). Therefore, this pillar plays a crucial role and characterizes the new institutionalism in organizational studies because of the relevance assigned to the cognitive dimension. These three pillars should be not considered separately. On the contrary, “when the pillars are aligned, the strength of their combined forces can be formidable” (Scott, 2014, p. 71). In this context, the study of the work of the three pillars and the related pressures is pivotal in understanding and explaining the present and future of practices in the public sector. This approach is adopted in the second chapter of the current thesis in order to explain which pressures are faced by public organizations in the same field in order to adopt PBB and the impact of their interaction and alignment (or lack of) on institutionalization of the practice.

Institutionalization is the label attached to the process through which the institutionalized status is achieved (Meyer & Rowan, 1991). Specifically, institutionalization is a dynamic and ongoing process (DiMaggio, 1988) whereby a social order or pattern chronically reproduced becomes institutionalized (Jepperson, 1991). The early institutionalists Berger and Luckmann (1967) stated that the main concern of this approach should be the production of knowledge. According to these scholars, reality is a social construction, and they therefore investigated the conceptualization of the

18

construction of common meaning systems by identifying three moments: externalization, objectification and internalization. During the phase of externalization, symbolic structures are produced, which are experienced as a reality during the objectification and, then, this objectified world is internalized. These three steps represent the process of institutionalization. Building on this model, Tolbert and Zucker (1996) propose the categorization of institutionalization into habitualization (pre-institutionalization), during which new arrangements are formulated in response to problems; objectification (semi-institutionalization), during which the arrangements acquire some consensus; and finally sedimentation (full institutionalization), characterized by the spread and perpetuation of such arrangements. Kostova and Roth (2002) build on these previous classifications in identifying the two main steps of the institutionalization process: implementation and internalization. This model, described in more detail in Chapter 2, has been used to conduct the empirical analysis because it is useful to investigate the ‘depth’ of PBB within organizations by focusing on the shift from the formal adoption of the practice to its full institutionalization. This approach has been enriched with additional concepts needed to deepen the micro-processes that occur at the organizational level and explain how the reactions to the external pressures determine the extent to which the process of PBB institutionalization can take place.

In this regard, it is necessary to create a premise. According to NIS, changes in accounting systems are derived from changes in context, new societal preferences or institutions. Therefore, the focus of NIS seems to be more on explaining the forces that lead to isomorphism and create similarities across organizations, rather than changes (Greenwood & Hinings, 1996). This attention to stability rather than to changes and the somehow under-estimated role of actors in challenging and changing institutions have been the two issues that have been debated and criticized. However, the existence of variation and heterogeneity has been recognized since the 1990s. As stated by Powell (1991), “there is a wide range of institutional influences, and internal responses to these pressures are more varied than is suggested by our initial argument” (p. 194). Therefore, several approaches have been developed in response to the criticisms previously listed. Oliver (1991)

19

discusses the various strategies an organization can adopt to respond to institutional pressures, thus creating the ground for studying change. According to Oliver, the institutional theory can explain variation and heterogeneity, and in particular, the concept of agency points out that an organization can have different resources and abilities to conform to other organizations and align themselves with the institutional context, thus generating variation and heterogeneity. While Oliver’s approach investigates the potential strategies adopted by organizations and the institutional factors that influence them, Greenwood and Hinings (1996) have theorized the stimuli that can explain organizations’ reactions to institutional pressures by focusing on organizations’ internal dynamics and on their interactions with external pressures. Indeed, they have paid attention to the impact of the interplay between organizational context and action on the type and path of change. Therefore, Greenwood and Hinings have developed a framework to study organizational change, starting from the perspective of the neo-institutionalist theory. The reasoning developed by these scholars is particularly interesting and relevant for the purpose of the research because it allows for focus on the organizational level by investigating internal dynamics and the interplay between them and the similar external pressures perceived by the organizations themselves, as explained in more detail in Chapter II.

These considerations point out that although the institutional theory is not mainly a theory developed to explain heterogeneity and variation, it can be a valid tool in that direction. Indeed, a growing body of research has adopted an institutional approach to explain practice variations that go beyond the isomorphic equilibrium (e.g. Dacin, Goodstein, & Scott, 2002; Dillard, Rigsby, & Goodmann, 2004; Seo & Creed, 2002). Further, several scholars have combined the institutional theory with other theories, as described by de la luz Fernandez-Alles and Valle-Cabrera (2006). For instance, previous studies on heterogeneity and practice variations have analysed the variation between what is imposed and what is done by investigating the tension between institutional and technical pressures (Cruz, Major, & Scapens, 2009) through a combination of multiple concepts and ideas. Oliver combined the resource-based view with neoinstitutionalism (1991) in order to solve the

20

tensions between conformity and differentiation and between isomorphism and heterogeneity. In this context, it is fruitful to integrate several concepts in order to explain the observed variations in PBB.

Greenwood and Hinings’ theorization has been implemented further in Chapter III. In this case, the analysis of internal dynamics is designed to investigate the reactions of the organizations to PBB practice. Indeed, contrary to the rational model of homo economicus, neoinstitutionalist scholars have used the model of bounded rationality to shed light on the limitations of the global rationality of the economic man (Simon, 1955). In particular, the concept of ambiguity (March, 1987) has been considered suitable to identify the main challenges of PBB, which the organizations are expected to cope with. The integration of these concepts allows the study of the impact that the internal dynamics of organizations, in response to PBB ambiguities, have on the PBB practice.

4. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY AND METHOD

The contemporary nature of PBB and the research interest in achieving an in-depth understanding of this phenomenon in the context where it is adopted and used make case studies the most appropriate research strategy. Indeed, as defined by Yin (1994, p. 13), a case study is “an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident”. Case studies offer the possibility of understanding and describing how a phenomenon appears in different settings and interpreting and explaining the reasons for its variation. Therefore, the case study method has been chosen not only to describe PBB in several contexts (descriptive purpose) but also, and especially, to investigate and explain the reasons why it can vary within and across countries and achieve, or not achieve, successful results (explanatory purpose). The aim of the work is not to identify the “best practice” but to explain the observed differences in practice. Therefore, an

21

explanatory case study method has been used for the purpose of the current research (Ryan, Scapens, & Theobald, 2002; Scapens, 2004).

The explanatory nature of the case study calls for the use of a specific theoretical approach in order to build sound and convincing explanations about PBB as observed and investigated in specific contexts (Scapens, 2004). The goal is “to develop theoretically informed understandings that provide explanations of the observed phenomena” (Ryan et al., 2002, p. 149). In this context, the work aims at being positioned as an explanatory qualitative research that leads to an in-depth understanding about PBB and context-related explanations in the context of three countries: Italy, Finland and Sweden (Flyvbjerg, 2006; Stake, 2013). Indeed, the research does not aim at producing scientific generalizations, but rather analytical generalizations and theoretical enrichments about PBB through context-related explanations. As Flyvbjerg explained (2006), “formal generalization” is only one way through which knowledge can be gained and is not necessarily the most valuable way. Indeed, context-dependent knowledge can be gained by using cases as examples and can produce interesting results and enrichments with reference to the research purpose.

In this context, theory plays a pivotal role in guiding and providing an understanding of PBB. Moreover, the specific focus on internal dynamics reinforces the need for conducting a case study since it would be somewhat difficult to quantitatively measure those dynamics (Greenwood & Hinings, 1996). In particular, the theoretical frameworks developed to conduct the empirical analysis have been considered as an input of the research because they have provided the lens through which the collected evidence has been interpreted. At the same time, by using the frameworks in context, the research has contributed to the theory itself by extending and enriching it.

The empirical analysis was conducted in three settings: Italy, Finland and Sweden. The first case study (Chapter II) focuses on the investigation of PBB at the central level of government in Italy, while the second case study (Chapter III) analyses PBB at the central level of government in Finland and Sweden. The tier of government does not change across the contexts, so the evidence collected