Ph.D. Course in Management of Innovation, Sustainability and Healthcare

Academic Year

2016/2017The impact of innovation on SMEs

financial dynamics and performance.

Author

Jonathan Taglialatela

Supervisor

iv

v

ABSTRACT

This thesis contributes to the research on small and medium innovative firms’ characteristics. The three research questions examined are (i) Do innovative young firms have different preferences for the sources of finance than non-innovative firms? (ii) Do innovative activities affect small firms’ ratings? (iii) Do patents impact on SMEs business performance?

These questions are relevant to academic literature, managers and policy makers. Despite noteworthy theoretical developments, empirical evidences trying to answer to these questions is still contrasting or limited. Such scarcity of studies can be partly imputed to the lack of datasets including innovation and financial data. In this study, three different datasets are used, namely the Mannheim start-up Panel and two unique datasets of Italian firms. The last three chapters of this thesis correspond to each one of the three stand-alone papers that have been written during the Ph.D. course. The first paper shows that different levels of innovative activities influence the pecking order of innovative start-ups and then suggests further research towards an extension of the classic pecking order theory, with the aim to integrate other sources of informed finance. The second paper finds that small firms that undertake innovative activities suffer from a lower reduction of credit ratings even if the financial system is subjected to an external shock, such as the recent financial crisis; the benefits of innovation seem are therefore relevant also in a time of crisis. The third paper tries to shed light on the effects of innovative activities on firms’ performance and growth, applying a novel methodology that combines nearest neighbour matching and differences-in-differences. The results show that innovative efforts have a strong impact on sales growth and then that policy efforts that support innovation can be fruitful.

vii

To Gioacchino, Monica,

Valeria and Stefania.

1

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1. Summary ... 1

1.2. Motives and importance of the topic ... 3

1.3. Structure of the thesis ... 5

1.4. References ... 7

2. Literature background ... 9

2.1. Small and medium enterprises: in what do they differ from large firms? ... 9

2.1.1. SMEs capital structure ... 10

2.1.2. SMEs credit ratings ... 13

2.1.3. SMEs performance ... 14

2.2. Innovation and SMEs ... 17

2.2.1. How to measure innovation ... 17

2.2.2. Innovation and capital structure ... 19

2.2.3. Innovation and credit ratings ... 20

2.2.4. Innovation and performance. ... 22

2.3. Research gaps and contribution of this thesis ... 23

2.4. References ... 25

3. Innovation, Asymmetric information and the capital structure of new firms. ... 35

3.1. Introduction ... 36

3.2. Theory and hypotheses ... 38

3.2.1. The capital structure of firms ... 38

3.2.2. Innovation and capital structure ... 40

3.3. Data and Methodology ... 44

3.3.1. The sample ... 44

3.3.2. Estimation strategy ... 48

2

3.4. Results and discussion ... 53

3.4.1. The hierarchy of financing choices ... 59

3.5. Conclusions ... 62

3.6. References ... 64

3.7. Appendix ... 69

4. Patents and firm performance: evidence from changes in credit ratings of italian SMEs ... 73

4.1. Introduction ... 74

4.2. Credit ratings and small firms’ performance ... 76

4.3. Innovation and credit ratings ... 78

4.4. Data and sample characteristics ... 82

4.5. Dynamics of rating during the crisis ... 87

4.6. Conclusions ... 93

4.7. References ... 94

5. Do patents affect SMEs’ performance? A counterfactual analysis ... 99

5.1. Introduction ... 100

5.2. Patents and economic performance ... 101

5.3. Methodology ... 105

5.4. Data description and econometric results ... 110

5.4.1. Nearest neighbour matching ... 112

5.4.2. Difference-in-differences estimation ... 113

5.5. Discussion and conclusions... 117

1

List of Tables

Table 1-1 Structure of the thesis ... 5

Table 3-1 Variables description ... 46

Table 3-2 Industry distribution of the sample analysed. ... 47

Table 3-3 Composition of the classes used in the ordered Probit. ... 50

Table 3-4 Panel Probit estimates for the probability of obtaining any amount of a specific type of finance. . 55

Table 3-5 Panel Probit regressions of the probability of obtaining more than 50% of a specific type of finance in a given year.. ... 58

Table 3-6 Ordered Probit regression for the classes specified in Table 5, column 1. ... 60

Table 3-7 Ordered Probit regression for the classes specified in Table 5, column 2. ... 61

Table 3-8 Descriptive statistics for the variables included in the regressions. ... 69

Table 3-9 Pairwise correlations between all the variables included, with the relative significance level. ... 70

Table 4-1 The composition of the sample, by size and by industry. ... 84

Table 4-2 Variables List ... 87

Table 4-3 Relationship between changes in probability of default and several of its determinants in 2006.. . 89

Table 4-4 Relationship between default probability, initial rating andseveral risk factors in 2006.. ... 90

Table 4-5 Changes in default probability during financial crisis and innovation interaction. ... 91

Table 4-6 Changes in default probability during financial crisis and innovation interaction. ... 92

Table 4-7 Regression of rating changes on innovation intensity indicators. ... 93

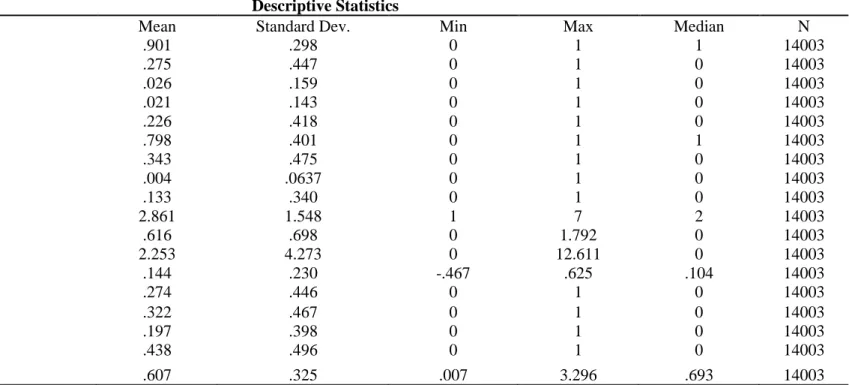

Table 5-1 Variables for DiD estimation and Matching ... 110

Table 5-2 Definition of the final sample of innovative firms ... 111

Table 5-3 Descriptive statistics of the variables ... 114

2

Table 5-5 Regression Analysis with Robust Standard Errors and DiD estimation. ... 116

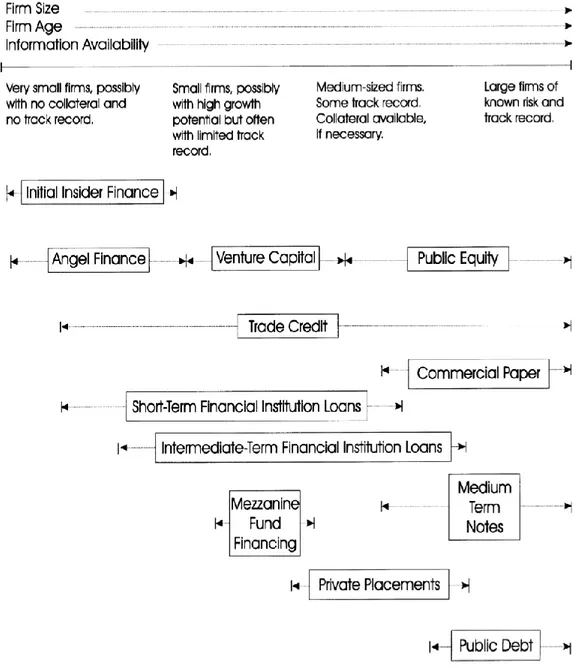

List of Figures Figure 2-1 Firm Finance continuum (Berger & Udell 1998). ... 11

Figure 4-1 Rating frequency for size classes (2006)... 85

Figure 4-2 Rating frequency distribution for innovating and control sample, by size class. ... 86

Figure 4-3 Default probability for innovative and control sample. ... 88

Figure 5-1 Selection and Matching Scheme ... 112

Figure 5-2 Differences in covariates before and after matching ... 113

1

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Summary

Small and medium size enterprises (SMEs) constitute the backbone of developed economies. Academic literature and policy makers recognize their primary role in fostering growth and job creation (European Commission, 2016; Audretsch, 2002; Acs & Storey, 2004), their role as innovators (Forsman, 2011; Romero & Martínez-Román, 2012; Audretsch, Coad, et al., 2014) and as central actors of the Schumpeterian process of creative destruction' (Schumpeter, 1934). After the recent financial crisis, the focus on small firms has gained momentum with a special attention devoted to young firms and start-ups. The crisis has posed major challenges to the private sector, due to a contraction of global demand; in particular, small and young firms have suffered a greater deal due to their limited financial capacity and to their sensitivity to disequilibrium in credit markets. These issues have been highlighted also by the ECB president Mario Draghi in his speech at the 2014 presentation ceremony of Schumpeter Award in Vienna, where he stated:” If small,

innovative firms cannot access finance, it has an important impact on employment and

investment. Studies from the United States show that the bulk of net new job creation comes

from young firms. At the same time, young firms have been shown to be much more sensitive

to changes in investment opportunities than older firms, meaning that fewer start- ups would

probably lead to lower trend productivity growth.” (Bank for international settlements,

2014). Policy makers and managers are interested in having a better understanding of how to release the innovation potential of small firms and spur their contribution to the economic system; such understanding, indeed, could be the key to economic recovery of the industrial system.

2

Innovation represents a multi-faceted phenomenon whose measurement is a daunting task. The plethora of definitions employed by prior studies does not facilitate the formation of a clear-cut evidence on how innovation affects business processes, growth, performance and financial dynamics (Rosenbusch et al., 2011; Chemmanur & Fulghieri, 2014b; Gu & Wang, 2005).

A noteworthy effort to improve the quality of innovation measurement has been made in Frascati and Oslo manuals (Oecd, 2002; Oecd, 2005). The work presented in this thesis follows several suggestions proposed by these guidelines, relying on innovation inputs (R&D expenditures) as well as innovation outputs (patents, product innovation and process innovation). Indeed, the Oslo manual highlights that using a set of innovation indicators decreases the risk to ignore innovation’s complex nature. The task to dig deeper on these issues is left to the next chapter, where the range of innovation indicators is properly detailed.

This thesis looks at innovative SMEs from three different perspectives and in different moments of their life-cycle. An effort has been made to look in different directions, to provide a contribution to the literature that is more diversified. The next sections will explain what are the research objectives, highlight the importance of the topic and provide a brief overview to each of the three papers and to the thesis' structure.

Overall, this study has three main research objectives. The first is to understand if the capital structure of new firms changes when those firms start innovating. The second is to shed light on how innovative SMEs credit ratings react when the credit markets are subjected to a shock. The third aims at estimating the impact of patents on SMEs performance through a combined matching and differences-in-differences methodologies.

3

1.2. Motives and importance of the topic

Investigating how innovators differ from other SMEs is of great interest for scientific literature, for government and for SMEs managers themselves.

From the academic perspective, this thesis contributes to the literature adding further empirical evidence, based on unique samples composed by innovative firms and matched control samples. In particular, the first chapter sheds light on the capital structure dynamics of new firms - a topic still underexplored - using a panel dataset that allows us to consider the evolution of the capital structure during time. This first work goes beyond the simple analysis on the kind of financial sources are used, making a leap towards the identification of the hierarchy of financing sources that is followed by these firms. The second paper analyses the evolution of credit ratings of a sample of patenting SMEs during the years of the financial crisis; in addition, a robustness section explores the consequences of higher intensity of innovative efforts on firms’ credit worthiness, contributing to the debate on the optimal level of innovative activity. The third paper addresses the much-discussed topic of the impact of innovative activities. The scientific community has mainly directed its efforts towards researching this issue for large firms. This work, instead, tries to draw conclusions for small and medium firms and applies a novel methodology with the aim of enhancing the results’ quality.

From the government perspective, huge efforts have been made to spur SMEs potential for economic growth. It is common to see national and supranational incentive programmes for the support of innovative activities in SMEs. For instance, the European community funded the “SMEs instrument”, in the framework of “Horizon 2020”, a program that is especially directed to SMEs with valuable innovative ideas that needs support

4

towards the paths of prototyping and commercializing it on a large scale. Between 2016 and 2017 more than € 700 million1 have been directed towards these programs. Moreover, a

specific work programme in “Horizon 2020” regards “Access to Risk Finance” and considers particular support for innovative SMEs, especially when they are in the start-up phase. In addition, each single state of the European Union is directing additional funds at national and regional levels, in the form of tax credits for whose decide to invest in start-ups and innovative firms, co-financing of innovative projects or similar measures. From the efforts of the public bodies it is evident that in order to design effective policy instrument to support these firms in the innovating processes, a deeper knowledge of their characteristics is needed. This work provides some insights on which kind of capital the firms decide to seek first and how this choice is influenced by innovative activities. The second paper is halfway between the access to finance and the business performance, stressing innovation effects on SMEs’ credit scores. The results show SMEs risk under a different perspective and demonstrate that innovation decreases the riskiness and that is should be systematically considered when credit ratings are calculated. This could be a contribution worthy of consideration by credit market regulators. The last chapter of this thesis tries to explore the relationship between innovation efforts and business performance. The ultimate aim of governments that issue policies to support innovation is to spur economic growth and to create jobs. The way to achieve these two objectives is a positive performance of firms that are making innovative efforts. Once a fully understanding of the relationship between innovation and business performance is achieved, government can

5

design better policies to sustain “creative destruction”. Therefore, this third chapter contributes to this exploration analysing how innovation affects SMEs performance.

Lastly, this thesis is important for SMEs themselves. It provides insights to would-be innovators that could see how other firms reacted to innovation’s stimuli. The thesis presents data from two large economies in continental Europe and that the conclusions can find application in similar industrial systems.

1.3. Structure of the thesis

This thesis is structured in five chapters. The second chapter describes previous research and highlights conclusions and findings from the research, suggesting limitations and implications of the work that has been done. Chapters three to five are structured each one as a stand-alone paper.

Chapter Research question Methodology Sample Years Country

3 Does innovation affect

capital structure? Probit, Ordered Probit 7’394 Start-ups 2005-2012 Germany 4

Do innovative firms credit ratings react differently to shocks to the credit system?

OLS linear regression 3’954 SMEs

2005-2010 Italy

5 Do patents affect business

performance of? Nearest Neighbour Matching combined with DiD. 3’746 SMEs 2003-2015 Italy

Table 1-1 Structure of the thesis

First paper: Innovation, Asymmetric information and the capital structure of

new firms. This paper is co-authored with Prof. Andrea Mina, and has been written during

a visiting period in 2016-2107 at the Centre for Business Research, Judge Business School, University of Cambridge. The paper has also been presented at the Druid Conference 2017, in New York. The research objective is to provide a clearer picture of the capital structure choices of new firms. In order to do that, the paper presents a combination of Probit and Ordered Probit regressions on the “Mannheim Start-Up panel”, provided by the Centre for

6

Economic Research (ZEW). Such dataset offers a unique combination of financial and innovation data, rarely found in studies based on European countries. The conclusions highlight that in an agency theory framework, innovation is positively associated with information asymmetries that in turn influence the preference for different types of finance. Only a few studies have analysed such range of financing option in a longitudinal setting. Moreover, the methodology used allows to control for the different combinations of financing sources and this enhances the robustness of the results.

Second paper: Patents and firm performance: evidence from changes in credit

ratings of Italian SMEs. This paper has been presented at the R&D Management

Conference 2015 in Pisa. The objective of the study is to understand if and how innovative activities affect the credit ratings of a sample of Italian SMEs. Credit ratings are taken as a proxy for business performance and default probability. All firms that are rated by Cerved, a major rating agency in Italy, are compared with a control sample and the dynamics of credit ratings on a five years horizon are analysed. Patents application are used as a proxy for innovative activities and the regression analysis shows that firms that applied for a patent exhibit a weaker decrease in rating quality compared to non-patenting firms. That means that innovation, which is not accounted for in Cerved ratings, has a positive effect on the long-term performance of these firms, even when the financial crisis was at its peak. In addition, a robustness section explores the consequences of high intensity of innovative activities, looking for an optimum level of innovation; results show that also the top innovators benefit from a positive effect on rating quality, discarding the idea that there is an optimal level of innovation.

The last paper “Do patents affect SMEs’ performance? A counterfactual

7

(UK). The aim of the study is to estimate the impact of innovative effort on firm performance. The work tries to add an additional piece of evidence to the contrasting literature on the effects of innovation, adopting a combined, still rarely used, methodology of nearest-neighbour matching and differences-in-differences. In order to build the sample, all firms that applied for a patent in Italy are compared with an appropriate a control group of SMEs with similar financial characteristics. During this selection process, particular care towards limiting the risk of endogeneity bias and of selection on unobservables was taken. Among the three proxies of business performance, only sales shows sensitivity to the innovative efforts. Indeed, firms that applied for a patent show a higher level of sales up to five years after patenting, demonstrating that the investment in innovation can be a springboard for an enhanced business performance.

1.4. References

Acs, Z. J. and Storey, D. (2004) ‘Introduction: Entrepreneurship and Economic Development’, Regional Studies, 38(8), pp. 871–877. doi:

10.1080/0034340042000280901.

Audretsch, D. B. (2002) ‘The dynamic role of small firms: Evidence from the U.S’, Small Business Economics, 18(1–3), pp. 13–40. doi: 10.1023/A:1015105222884.

Audretsch, D. B., Coad, A. and Segarra, A. (2014) ‘Firm growth and innovation’,

Small Business Economics, 43(4), pp. 743–749. doi: 10.1007/s11187-014-9560-x.

Bank for international settlements (2014) Mario Draghi : Bank restructuring and

the economic recovery. Vienna.

Chemmanur, T. J. and Fulghieri, P. (2014) ‘Entrepreneurial finance and

innovation: An introduction and agenda for future research’, Review of Financial Studies, 27(1), pp. 1–19. doi: 10.1093/rfs/hht063.

European Commission (2016) Europe’s next leaders: the Start-up and Scale-up

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-8 content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2016:733:FIN.

Forsman, H. (2011) ‘Innovation capacity and innovation development in small enterprises. A comparison between the manufacturing and service sectors’, Research

Policy. Elsevier B.V., 40(5), pp. 739–750. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2011.02.003.

Gu, F. and Wang, W. (2005) ‘Intangible assets, information complexity, and analysts’ earnings forecasts’, Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 32(December), pp. 1673–1702.

Oecd (2002) The Measurement of Scientific Technical Activities. Frascati Manual

2002. Proposed Standard Practice for Surveys of Research and Experimental

Development. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. doi:

10.1787/9789264199040-en.

Oecd (2005) Oslo manual: Guidelines for collecting and interpreting innovation

data. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. doi:

10.1787/9789264013100-en.

Romero, I. and Martínez-Román, J. A. (2012) ‘Self-employment and innovation. Exploring the determinants of innovative behavior in small businesses’, Research Policy, 41(1), pp. 178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2011.07.005.

Rosenbusch, N., Brinckmann, J. and Bausch, A. (2011) ‘Is innovation always beneficial? A meta-analysis of the relationship between innovation and performance in SMEs’, Journal of Business Venturing, 26(4), pp. 441–457. doi:

10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.12.002.

Schumpeter, J. (1934) The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits,

capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

9

2. LITERATURE BACKGROUND

This section is divided in 2 subsections. The first will discuss briefly why and how small firms are different from large firms, with focuses on capital structure, credit ratings and business performance. In section 2, the thesis explains what happens when innovation and its effect are considered on these three dynamics, highlighting the research gaps to which this thesis tries to contribute.

2.1. Small and medium enterprises: in what do they differ from large firms?

As previously mentioned, SMEs are fundamental actors of economic growth and job creation. Previous research highlights that SMEs are not just smaller version of large firms, but have their own characteristics, strength and weaknesses. This thesis is directed towards this body of literature, in particular towards the literature studying the effects of innovation on these firms’ dynamics.

There is no universally accepted definition of SMEs. In this work, the European definition of small firms is adopted, i.e. firms that have less than 250 employees and a balance sheet total lower than € 43 million or turnover lower than € 50 million. In the U.S., differently, SMEs are usually identified as firms with less than 500 employees, without any limit on balance sheet values.

Differently than large firms, SMEs exhibit a flexible organizational structure, and are more sensitive to environmental changes, such as in the legal framework or in IP protection (Nooteboom, 1994; Vossen, 1998).Other differences can be found in the way they approach capital markets, in the sensitivity of their credit ratings and in how innovation

10

efforts, such as patents, impact their business performance. In the next section, each of these three points will be considered individually.

2.1.1. SMEs capital structure

Literature on capital structure moved on from the proposition of irrelevance of capital structure by Modigliani and Miller (1958); the unsuccessful empirical tests for this theory opened space for the emergence of alternative views. The “pecking order theory”, by Myers (1984) and Myers and Majluf (1984), reverses the idea that the sources of finance are perfect substitutes; instead, information asymmetries determine the specific kind the firms will prefer. The concept of information asymmetries can be traced to Akerlof's (1970) intuition of the presence of a “lemon premium” when information is not equally distributed between the counterparts. This will create “agency costs” (Jensen & Meckling, 1976) that will increase the overall cost of a specific type of finance. According to the pecking order theory, three sources of finance are available: retained earnings (also called “internal finance”), debt and equity. Internal finance is always preferred because it does not entail any agency cost nor does it implies adverse selection problem. On the other hand, relying on external sources of finance is costlier because of the presence of the “lemon premium”. Debt should be preferred to equity due to a lower agency cost. Bank credit should be preferable to equity for two main reasons. Banks perform screening and monitoring functions, which contribute to the reduction of information asymmetries, minimising the agency costs (Diamond, 1984; Stiglitz & Weiss, 1981). In addition, banks perform the function of information production, contributing indirectly to decrease agency costs for other potential financiers (Stiglitz & Weiss, 1988; Diamond, 1991). Public equity issues, instead, should be negatively perceived by financial markets because imply that the firm is overvalued, causing dilution effects.

11

Figure 2-1 Firm Finance continuum (Berger & Udell 1998).

Small firms, in addition, exhibit a specific financial lifecycle, theorized by Berger & Udell (1998, 2006) . They conclude that financing decisions depend mainly from these firm’s industrial sectors and growth cycle, whereas larger firms adopt different criteria. In this finance continuum (see Figure 2-1) new firms will only have access to simple sources of finance. These firms’ dimensions together with the absence of track records and collaterals increase their informational opacity (Gompers, 1999). Their debt is not assessed by rating agencies and they can hardly access to financial markets. Therefore, they have

12

serious difficulties in finding capital and their growth is affected by financial constraints (Carpenter & Petersen, 2002). As they grow and become older, their informational asymmetries will decrease and they will have the opportunity to access more complex sources of finance, such as business angels and venture capital debt and financial markets. Empirical evidence on the application of capital structure theories did not provide clear results (Frank & Goyal 2003,2008; Fama & French 2005; Lemmon & Zender 2010). Whereas the choice of internal over external finance is straightforward, views differ regarding the context where pecking order theory can be applied (Leary & Roberts, 2010) and about the preference between equity and debt (Frank & Goyal, 2008). Among others Shyam-Sunder and Myers (1999) find that confirmation of the hypotheses in question, but their findings are in contrast with Frank and Goyal (2003); the latter point out that pecking order theory finds more support amongst large firms but conclude that the theory is not supported by data. Literature analysing small firms finds that SMEs seem to have a behaviour that is closer to the predictions of pecking order theory (Serrasqueiro et al., 2011; López-Gracia & Sogorb-Mira, 2008).

Especially when restricting the analysis to new firms, as a subset of SMEs, the number of studies decreases quickly, mainly because of lack of data. Paul et al. (2007) finds that start-ups violate the pecking order theory assumptions about external finance, preferring equity to debt. The importance of external equity for start-ups is highlighted also by Hechavarría et al. (2016). An opposite result is found Robb & Robinson (2014) that analysed the Kauffman survey data and found out that SMEs, and especially new firms, rely heavily on debt to satisfy their financial needs. However, a stream of literature (Hogan & Hutson, 2005; Hogan et al., 2016; Minola et al., 2013; Serrasqueiro et al., 2016) has recognized that

13

when technology and innovation are involved, all issues pertaining to SMEs are exacerbated, as will be outlined in section 2.2.

2.1.2. SMEs credit ratings

Credit ratings are a way to express concisely the credit worthiness of a borrower. They are widely used in the financial markets and they are assigned to sovereign debt, corporate bonds and, even if less frequently, for small firms.

These ratings, according to the present regulations, can be calculated internally by banks or can be quantified by credit rating agencies. In both cases, the rating process has to be approved by the regulatory authority. Ratings assignment is based on a set of information, that is often related to the size of the firm: especially for SMEs, ratings are frequently based only on quantitative information. However, the role of non-financial factors has been acknowledged by academic literature (Grunert et al., 2005) and therefore the rating estimation can hamper the efficient functioning of the credit system. On the contrary, ratings could provide information that is not yet incorporated in public knowledge (Kraft, 2015), performing the information production function (Stiglitz & Weiss, 1981) and decreasing the overall information asymmetry.

Credit ratings are also a reliable indicator of firm’s default probability and performance and can offer insights on its dynamics (Grunert et al., 2005). Ratings try to determine the probability that a firm will default and will be unable to honour its debt obligation. They take into account financial and business risks, including industry, management characteristics, profitability, liquidity and flexibility (Czarnitzki & Kraft, 2004). Therefore, the ratings express present and future perspective of the firms, including also its business performance.

14

In this work, a rating agency perspective is used to investigate how firms’ business performance, proxied by changes in credit ratings, evolves over time. Especially during the financial crisis, when financial constraints are harder, this perspective can provide several insights. Exploring the dynamics that are behind firms’ ratings could help to better identify how unaccounted factors influence the risk of these firms. Section 2.2.3 and chapter 4 will investigate how innovative activities can enter this discourse.

2.1.3. SMEs performance

Performance is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon. As highlighted in an extensive literature review by Combs et al. (2005), there is a lack of consensus around the definitions and measurements for organizational performance. Often researchers have used several different measures (Murphy et al., 1996) and this as contributed to a myriad of studies that are difficult to compare. According to Combs et al. (2005), the majority of studies that analyse business performance use measures around three dimensions: stock market performance, profitability and growth.

Stock market performance is rarely applicable for small firms and therefore will not be considered in this work. It is worth to mention that small firms that are listed distinguish themselves for a peculiar effect, the so-called “small firm effect”, where they exhibit a better performance on stock markets compared to firms that are largely capitalized. This effect was at first identified by Banz (1981), but a large body of research grew after Fama and French (1992) evidenced the shortcomings of the CAPM model by Sharpe (1964) and Lintner (1965). According to van Dijk (2011), the debate on the causes of this effect is still open. Several possible causes have been identified, including partial irrationality of investors and the role of transaction costs and liquidity risk in determining the size premium.

15

Growth of firms has always had a prominent role in scholar’s interests and, therefore, several theories have been developed to explain its mechanisms.2

Economics and management literature have stressed the importance of size as a fundamental concept that is strictly linked with firm growth. Since Gibrat (1931) “Law of Proportionate Effect”, a large body of empirical literature followed highlighting its relevance in investigating the growth pattern of the firm and exploring how size is a differentiating factor when analysing firms. This law states that the expected growth rate of a firm is independent of its size,3 a strong theoretical base for research of firms’ growth

determinants. Size of the firms assumes, therefore, a central role in the analysis of the firms’ growth patterns. Empirical studies tend to confirm that small firms exhibit growth rates tend to decrease with size and that Gibrat’s law holds only for firms that are over a certain threshold (Lotti et al., 2003; Becchetti & Trovato, 2002).4

On the other hand, Penrose (1959) seminal book laid the foundations for the development of theories of growth. The influential role of Penrose’s theory for the strategic management literature has been confirmed by several scholars (Lockett & Thompson, 2004; Kor & Mahoney, 2004; Coad, 2007). Her theory sees the firm as a dynamic environment where growth is spurred by increases in employees’ knowledge thanks to the additional experience gained on the job. Therefore, new talent exceeds the talent required to perform daily operation and can be spent focusing on growth opportunities. A complementary concept to Penrose growth theory is the presence of rare, valuable, inimitable and

2 The growth measurement can vary widely between sales growth, employment growth or market share

growth. In this work, sales growth is used, among other measures, as a proxy for business performance.

3 For a survey of empirical results on Gibrat’s law see Lotti, Santarelli and Vivarelli (2003)

4 Concerns about econometric issues have been raised, but their analysis goes beyond the scope of this work;

16

substitutable resources and capabilities that a firm has to acquire to continue to benefit from competitive advantage. This view has been developed in literature under the name of “Resource based view of the firm” (Penrose, 1959; Barney, 1991) Owning these resources explains how a firm can achieve a “sustained competitive advantage”. Wernerfelt (1984) listed several examples of these resources, such as skilled personnel, brands, know-how.

However, several insights emerge in the analysis of how large firms differ from small firms in terms of performance. Looking at small firms through the lenses of the resource based view highlights that the acquisition of these unique resources is not straightforward as it may seem. The ownership of strategic resources by small firms is made difficult by a chronic lack of resources and the absence of economies of scale.

Porter (1980), complementing Penrose’s view, sheds light on which companies are more profitable between large and small firms, and he points out that in absence of economies of scale “smaller firms following specialist strategies may be able to achieve

higher product differentiation or greater technological progressiveness or superior service

in their particular product niches than larger firm”(Porter, 1980, p.146). Then, small firms

can achieve a competitive advantage with the ability of their employees to create differentiated products for niche markets where large firms do not enter; this is opposed to large firms that rely on economies of scale and cost efficiency. These new products can contribute in growing existing markets, leading to a better business performance. Operating in profitable niches with innovative products is advantageous for SMEs due to their flexible structure and to the absence of hierarchies (Nooteboom, 1994). Also, their informal structure contributes to make them fast actors in market dynamics. All these advantages help SMEs in competing with large firms that can rely on a higher amount of resources. The Schumpeterian vision of innovation as a way to obtain temporary monopoly benefits is

17

therefore viable by these fast and flexible firms that can move faster than their large competitors and can enter underexploited segments of the market. Therefore, as section 2.2.4 will detail, SMEs can be good innovators and can be able to shift the benefits of innovations to the performance.

2.2. Innovation and SMEs

The concept of innovation is strictly linked with the concept of “creative destruction”, as conceived by Schumpeter (1934). This “destruction”, which comes along with innovative processes, is expected to introduce changes in a firm internal dynamics, organizational structure and financial characteristics. Academic literature has developed several streams of research about the effects of innovative activities on firms’ features. But before including innovation in this discourse, a clarification is needed on how innovation is proxied.

2.2.1. How to measure innovation

Academic research has often modelled innovation as a process (Crépon et al., 1998). Usually, a distinction arises between factors that participate as inputs to innovation processes (funds directed towards R&D expenditures or people that work in research departments) and factors that constitute an output of the innovation process (such as patents, new products or new processes) (Acs & Audretch, 1988). Therefore, measuring innovation inputs could be done by quantifying the R&D investments, the number of people working in R&D departments, or just using a dummy variable to indicate if a firm is investing in R&D or not. Often, these measures are scaled by dividing them for the total sales or total assets of the firm. On the other hand, innovation output measures can be the number of

18

actual innovations that a firm introduces, either products or processes, or a dummy variable to indicate if the firm has introduced one in the time frame of analysis.

Despite the unique information embedded in these innovation indicators, some issues arise. R&D expenses data, outside the UK and US accounting systems, are available almost exclusively for listed firm. In addition, most of these measures are self-reported or collected through surveys and their objectivity can be questioned.

Patents are also one of the most common measures of innovation output. Their value as proxies of innovation has been largely discussed in literature; they are appreciated for their objectivity (since they are scrutinised from an external actor) and for the set of information they provide (Griliches, 1990). However, several critics have been moved towards, such as the fact that large firms tend to patent more (Acs & Audretsch, 1991) and that the number of patent varies greatly across industries.

Whereas the use of strategic patents has been acknowledged by the literature (Blind et al., 2009; Cesaroni & Baglieri, 2012), when focusing on the context of small firms, several conditions change. Previous research indicate that patent propensity is lower in SMEs than in large firms (Mansfield, 1986; Arundel & Kabla, 1998; Brouwer & Kleinknecht, 1999), but these firms are more likely to make a productive use of their patents, also as a signal of their growth potential to external investors (Jensen & Webster, 2006; Hughes & Mina, 2010). Therefore, patents in the context of small firms could actually indicate firm’s innovative efforts and can allow to capture part of the effect of innovation on these firm’s dynamics.

19

2.2.2. Innovation and capital structure

The level of informational asymmetry in SMEs is already, as stated previously, high due to their specific characteristics. Innovation represents an additional element that contributes to create a disparity of information between firms and investors. Innovative projects have uncertain results and imply technological and market risks. Financiers therefore face many difficulties in evaluating firms’ intangible assets and the high probability of failure offers no offset to debt holder. In addition, young firms, as a subset of SMEs, will be more likely cash-poor and without the necessary financial resources to service the debt. Several studies clarified that the more innovative firms have higher informational opacity then their counterparts (Aghion et al., 2004; Hogan et al., 2016; Hall, 2010).

In this thesis, the objective is to examine how innovative small firms’ capital structure is affected by innovative activities, in a pecking order theory setting. Whereas abundant empirical evidence is available on the preference for internal to external finance (Cosh et al., 2009; Mina et al., 2013), less clarity exists regarding the choice between equity and debt. Theoretical arguments have been provided that firms with a high level of information asymmetry would prefer equity to debt (Thakor & Lo, 2017; Inderst & Vladimirov, 2016; Fulghieri et al., 2013). This behaviour would represent a violation of the pecking order theory outcomes. Consequently, private equity5 has been identified as the missing link in these relationships. Indeed, such private equity, specifically under the form of venture capital, has superior screening abilities and uses sector specific instruments; it is,

5Previous research (Bertoni et al., 2013) has evidenced the specific role of venture capital in decreasing

information asymmetries, highlighting the distinction from private equity funding. In this work, term “private equity” is used when referring to venture capital, business angels and generally the so-called informed finance, adopting the broader definition of the European Venture Capital Association, which includes venture capital funding.

20

therefore, particularly suited to cope with high levels of information asymmetries(Gompers & Lerner, 2001; Sahlman, 1990; Kaplan & Strömberg, 2003; Bertoni et al., 2011). Theoretically, this would lead to a hierarchy of financing sources with increasing agency costs, where private equity would immediately follow internal finance. Only in a subsequent moment of their life firms will access debt and financial markets.

The empirical evidence is generally mixed and in the case of new firms is scarce (among them(Giudici & Paleari, 2000; Robb & Robinson, 2014; Cassar, 2004; Paul et al., 2007; Vanacker & Manigart, 2010). Brown et al. (2012) find that high tech firms are less likely to use bank loans and find more difficulties in raising bank finance. Conversely, Fryges et al. (2015) that find a positive relationship between R&D intensity and use of bank debt. The divergence of results is not easily explained in the pecking order theory setting.

According to Lahr & Mina (2015), these deviations from the pecking order can be explained by innovation, measured with a set of output and input indicators. The analysis performed in chapter 3 assumes that, according to the finance continuum by Berger & Udell (1998), when a new firm starts innovative activities its informational opacity is at the maximum level. Therefore, this firm will only be able to access simple sources of finance, such as internal finance. When the information asymmetries of these firms will decrease, so will the corresponding agency costs, opening up the opportunity to access more complex sources of finance, such as business angels, venture capital and bank debts.

2.2.3. Innovation and credit ratings

As already pointed out, credit ratings should be, by definition, very sensitive to activities that can have serious consequences on a firm’s solvency, business performance and growth. Not all factors that can have these effects are included in the rating calculation.

21

Here the focus is on innovative efforts. These activities come along with a variety of effects that can affects the level of informational opacity and economic returns (Hall, 2010). The high complexity of intangible assets that come along with innovative efforts increases informational asymmetries and then difficulties for analysts in forecasting the future evolution of the firm’s dynamics. Growth options embedded in R&D projects contribute to uncertainty, affecting in turn the evaluation process (Lev, 2002). Such options can also create an incentive for managers to invest in projects that are too risky, creating an overinvestment problem (Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Myers, 1977).

Whereas numerous studies have explored the relationship between innovation and business performance (see next section), this bidirectional effect of innovation on firm credit worthiness (and indirectly on its business performance) did not receive much attention from scholars. Al-Najjar & Elgammal (2013) focused on listed firms, confirming that rating quality is improved by innovative activities. Rostamkalaei and Freel (2016) find that small innovative firms, instead, tend to pay a higher price for loans, i.e. reflect their higher level of risk. Czarnitzki & Kraft (2004) find, instead, that innovation has a positive impact on ratings, but that after a certain innovation threshold the relationship can turn negative. Pederzoli et al. (2013) study the role of patent portfolio in the credit risk modelling on a sample of SMEs estimating the effect on default probability; they find that patents always reduce the default probability. Chapter 4 enters this discourse using actual credit rating issued by Cerved, a major rating agency in Italy, analysing data on Italian SMEs during the years of the recent financial crisis. The study tries to explore the link between innovation and default probability through the lenses of credit rating agencies, discussing the effects of innovative activities on firm’s credit worthiness.

22

2.2.4. Innovation and performance.

A substantial piece of literature stresses the benefits of innovative activities. Schumpeter (1934) sees innovation efforts as the chance for entrepreneurs of gaining temporary monopolist benefits. A firm that is continually involved in this process of “creative destruction” can constantly benefit from an entrepreneurial advantage and the can perform better than its competitors. It was already mentioned that business performance of SMEs is different from that one of large firms. When these firms offer innovative products to their niches, they are able to avoid price competition, to stimulate demand and therefore to enhance their performance. Always according to Porter (1980), a firm that is able to set high barriers to competitors, can even enjoy long term above-average returns. Additionally, innovative efforts are supposed to provide other effects. The learning process that is established during the innovation process generates absorptive capacity defined as a firm's ability to recognize the value of new information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Zahra & George, 2002). This capacity developed by SMEs implies, then, a competitive advantage.

These theoretical arguments support a positive relationship between SMEs performance and innovation. However, the multifaceted nature of innovation suggests that not all effects are positive. Several scholars evidence how innovation can be risky and resource consuming (Nooteboom, 1994; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). Therefore, the effects of innovative activities on performance can be assumed as the result of positive and negative effects. The overall impact is excepted to be positive and similarly a positive link between innovation and business performance is expected.

23

Academic literature provides mixed results on this relationship; when restricting the focus on the use patents as a proxy for innovation (already discussed in section 2.2.1), no clear relationship between patents and performance emerges (Greenhalgh & Rogers, 2007). Several studies find a positive relationship (Geroski, 1993; Geroski & Machin, 1992; Cefis & Ciccarelli, 2005; Cockburn & Griliches, 1988; Hall et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2012) while others find no association (Griliches et al., 1991) or even negative correlation (K.W. Artz et al., 2010) between the measures of performance and the use of patents.

When focusing on SMEs, as extensively documented by Rosenbusch et al. (2011), the number of studies decreases sharply. Contrasting insignificant (Demirel & Mazzucato, 2012; Freel, 2000; Agostini et al., 2015; Del Monte & Papagni, 2003) and positive (Kannebley et al., 2010; Lööf & Heshmati, 2006) results are evidence the partial understanding of this phenomena.

This thesis contributes to this literature, using patents ad a proxy for innovative activities, trying to combine nearest neighbour matching and differences-in-differences to cope better with the most common issues that arise when dealing with innovation data.6

2.3. Research gaps and contribution of this thesis

In line with the literature background presented, several gaps were identified. The contrasting results of studies on capital structure choices of new firms has motivated part of this thesis. Using one of the few datasets incorporating financial and innovation information, this work sheds light on the major effects that innovation efforts have on the determination of capital structure of new firms in an agency theory framework. Results show that

6 See chapter 5 for a detailed explanation.

24

innovative activities increase the level of information asymmetries. In turn, firms with higher information asymmetries are more likely to access finance with lower agency costs. Specifically, empirical evidence of a hierarchy of financing sources that is based on increasing agency costs is found, and the results are robust also when controlling for different combinations of financing sources and simultaneous use of several types of capital. In addition, the panel dimension of the data helps to account for simultaneity bias.

The relationship between innovation and firms’ credit ratings needs further exploration. Analysing the dynamics of rating evolution on a five years timespan, confirmation is found that, even when there is an external shock to credit markets, firms that innovate are still able to achieve an above average performance and a better credit worthiness. Furthermore, results suggest that, including elements related to innovative activities in credit decisions could improve, ex-ante, the efficiency of credit market and relief the financial constraint for innovative firms.

This work also contributes to the literature evaluating the impact of innovation. Specifically, after acknowledging that the empirical evidence on the impact of patents on SME’s business performance is still lacking or contrasting, this thesis tries to add a contribution combining two different methodologies, with the aim of mitigating the risks of sample selection bias and reverse causality.

Results show that firms that apply for a patent benefit of an above-average performance in terms of sales for up to five years after filing. On the other hand, the profit indicators are not showing better performance; therefore, the firms in the sample are not able to get the most out of their innovation efforts and additional research is needed.

25

2.4. References

Acs, Z. J. and Audretch, D. B. (1988) ‘Innovation in Large and Small Firms : An Empirical Analysis’, The American Economic Review, 78(4), pp. 678–690.

Acs, Z. J. and Audretsch, D. B. (1991) ‘R&D, firm size and innovative activity.’, in Innovation and technological change: An international comparison. New York: Harverster Wheatsheaf.

Aghion, P., Bond, S., Klemm, A. and Marinescu, I. (2004) ‘Technology and financial structure: are innovative firms different?’, Journal of the European Economic

Association, 2(2–3), pp. 277–288. doi: 10.1162/154247604323067989.

Agostini, L., Caviggioli, F., Filippini, R. and Nosella, A. (2015) ‘Does patenting influence SME sales performance? A quantity and quality analysis’, European Journal of

Innovation Management, 30, pp. 645–658. doi:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02683940010305270.

Akerlof, G. a (1970) ‘The Market for “Lemons”: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), pp. 488–500. doi: 10.2307/1879431.

Al-Najjar, B. and Elgammal, M. M. (2013) ‘Innovation and credit ratings, does it matter? UK evidence’, Applied Economics Letters, 20, pp. 428–431. doi:

10.1080/13504851.2012.709589.

Artz, K. W., Norman, P. M., Hatfield, D. E. and Cardinal, L. B. (2010) ‘A Longitudinal Study of the Impact of R&D, Patents, and Product Innovation on Firm Performance’, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 27, pp. 725–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5885.2010.00747.x.

Arundel, A. and Kabla, I. (1998) ‘What percentage of innovations are patented? empirical estimates for European firms’, Research Policy, 27(2), pp. 127–141. doi: 10.1016/S0048-7333(98)00033-X.

Banz, R. W. (1981) ‘The relationship between return and market value of common stocks’, Journal of Financial Economics, 9(1), pp. 3–18. doi:

26

Barney, J. (1991) ‘Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage’, Journal

of Management, 17(1), pp. 99–120. doi: 10.1177/014920639101700108.

Becchetti, L. and Trovato, G. (2002) ‘The determinants of growth for small and meduim sized firms. The role of External Finance’, Small Business Economics, 19(4), pp. 291–306. doi: 10.1023/A:1019678429111.

Berger, A. N. and Udell, G. F. (1998) ‘The economics of small business finance: The roles of private equity and debt markets in the financial growth cycle’, Journal of

Banking & Finance, 22, pp. 613–673. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4266(98)00038-7.

Berger, A. N. and Udell, G. F. (2006) ‘A more complete conceptual framework for SME finance’, Journal of Banking & Finance, 30(11), pp. 2945–2966. doi:

10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.05.008.

Bertoni, F., Colombo, M. G. and Grilli, L. (2011) ‘Venture capital financing and the growth of high-tech start-ups: Disentangling treatment from selection effects’,

Research Policy. Elsevier B.V., 40(7), pp. 1028–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2011.03.008.

Bertoni, F., Ferrer, M. A. and Martí, J. (2013) ‘The different roles played by venture capital and private equity investors on the investment activity of their portfolio firms’, Small Business Economics, 40(3), pp. 607–633. doi: 10.1007/s11187-011-9384-x.

Blind, K., Cremers, K. and Mueller, E. (2009) ‘The influence of strategic patenting on companies’ patent portfolios’, Research Policy. North-Holland, 38(2), pp. 428–436. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2008.12.003.

Brouwer, E. and Kleinknecht, A. (1999) ‘Innovative output, and a firm’s propensity to patent. An exploration of CIS micro data’, Research Policy, 28, pp. 615– 624. doi: 10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00003-7.

Brown, M., Degryse, H., Höwer, D. and Penas, M. F. (2012) ‘How do banks screen innovative firms? Evidence from start-up panel data’, ZEW Discussion Papers, No. 12-032(12), pp. 1–37.

Carpenter, R. E. and Petersen, B. C. (2002) ‘Is the Growth of Small Firms Constrained by Internal Finance?’, Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(2), pp. 298– 309. doi: 10.1162/003465302317411541.

27

Cassar, G. (2004) ‘The financing of business start-ups’, Journal of Business

Venturing, 19(2), pp. 261–283. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00029-6.

Cefis, E. and Ciccarelli, M. (2005) ‘Profit differentials and innovation’, Economics

of Innovation and New Technology, 14(1–2), pp. 43–61. doi:

10.1080/1043859042000232160.

Cesaroni, F. and Baglieri, D. (2012) ‘Technology Intelligence: New Challenges from Patent Information’, in De Marco M., Te’eni D., Albano V., Za: Information

Systems: Crossroads for Organization, Management, Accounting and Engineering.

Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag HD, pp. 267–274. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7908-2789-7_30. Chang, K.-C., Chen, D.-Z. and Huang, M.-H. (2012) ‘The relationships between the patent performance and corporation performance’, Journal of Informetrics, 6(1), pp. 131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2011.09.001.

Coad, A. (2007) ‘Firm Growth: A Survey’, Papers on Economics & Evolution, 10(May), pp. 1–73.

Coad, A. (2009) The Growth of Firms: a survey of theories and empirical

evidence. Edward Elgar Publishing. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

Cockburn, I. and Griliches, Z. (1988) ‘Industry Effects and Appropriability Measures in the Stock Market ’ s Valuation of R & D and Patents’, American Economic

Review, 78(2), pp. 419–423.

Cohen, W. M. and Levinthal, D. A. (1990) ‘Absorptive Capacity: A New

Perspective on Learning and Innovation’, Administrative Science Quarterly. Edited by W. H. Starbuck and P. S. Whalen. Cornell University, Johnson Graduate School (Technology, organizations, and innovation), 35(1), pp. 128–152.

Combs, J. G., Crook, T. R. and Shook, C. L. (2005) ‘The Dimensionality of Organizational Performance and its Implications for Strategic Management Research’, in Ketchen, D. and Bergh, D. (eds) Research Methodology in Strategy and Management. San Diego, CA: Elsevier, pp. 259–286. doi: 10.1016/S1479-8387(05)02011-4.

Cosh, A., Cumming, D. and Hughes, A. (2009) ‘Outside Entrepreneurial Capital’,

28

Crépon, B., Duguet, E. and Mairessec, J. (1998) ‘Research, Innovation And

Productivity: An Econometric Analysis At The Firm Level’, Economics of Innovation and

New Technology, pp. 115–158. doi: 10.1080/10438599800000031.

Czarnitzki, D. and Kraft, K. (2004) ‘Innovation indicators and corporate credit ratings: Evidence from German firms’, Economics Letters, 82, pp. 377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2003.09.016.

Demirel, P. and Mazzucato, M. (2012) ‘Innovation and Firm Growth: Is R&D Worth It?’, Industry & Innovation, 19(1), pp. 45–62.

Diamond, D. W. (1984) ‘Financial intermediation as delegated monitoring’,

Review of Economic Studies, 51(3), pp. 393–414. doi: 10.2307/2297430.

Diamond, D. W. (1991) ‘Monitoring and Reputation: The Choice between Bank Loans and Directly Placed Debt’, Journal of Political Economy, 99(4), pp. 689–721. doi: 10.1086/261775.

van Dijk, M. A. (2011) ‘Is size dead? A review of the size effect in equity returns’,

Journal of Banking and Finance. North-Holland, pp. 3263–3274. doi:

10.1016/j.jbankfin.2011.05.009.

Eisenhardt, K. M. and Martin, J. A. (2000) ‘Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They?’, Strategic Management Journal, 21(10/11), pp. 1105–1121. doi: 10.2307/3094429.

Fama, E. F. and French, K. R. (1992) ‘American Finance Association The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns’, The Journal of Finance, 47(2), pp. 427–465.

Fama, E. F. and French, K. R. (2005) ‘Financing decisions: Who issues stock?’,

Journal of Financial Economics, 76(3), pp. 549–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.10.003.

Frank, M. Z. and Goyal, V. K. (2003) ‘Testing the pecking order theory of capital structure’, Journal of Financial Economics, 67(2), pp. 217–248. doi: 10.1016/S0304-405X(02)00252-0.

Frank, M. Z. and Goyal, V. K. (2008) ‘Trade-Off and Pecking Order Theories of Debt’, in Handbook of Empirical Corporate Finance SET, pp. 135–202. doi:

10.1016/B978-0-444-53265-7.50004-4.

29

Small Business Economics, 14, pp. 195–210. doi: 10.1023/A:1008100206266.

Fryges, H., Kohn, K. and Ullrich, K. (2015) ‘The Interdependence of R&D Activity and Debt Financing of Young Firms’, Journal of Small Business Management, 53(6217), pp. 251–277. doi: 10.1111/jsbm.12187.

Fulghieri, P., Garc, D. and Hackbarth, D. (2013) ‘Asymmetric Information and the Pecking (dis)order’, UNC Kenan-Flagler Research Paper No. 2012-6.

Geroski, P. (1993) ‘The profitability of Innovating firms’, The RAND Journal of

Economics, 24(2), pp. 198–211.

Geroski, P. and Machin, S. (1992) ‘Think again: Do innovating firms outperform non-innovators?’, Business Strategy Review, pp. 82–86. doi:

10.1111/j.1467-8616.2013.00959.x.

Gibrat, R. (1931) Les inégalité économiques. Paris: Librairie du Receuil Sire. Giudici, G. and Paleari, S. (2000) ‘The Provision of Finance to Innovation : A Survey Conducted Italian among Small Firms’, Small Business Economics, 14(1), pp. 37– 53.

Gompers, P. A. (1999) ‘Resource Allocation, Incentives and Control: The

Importance of Venture Capital in Financing Entrepreneurial Firms’, in Entrepreneurship,

Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises and the Macroeconomy, pp. 206–235.

Gompers, P. and Lerner, J. (2001) ‘The Venture Capital Revolution’, Journal of

Economic Perspectives, 15(2), pp. 145–168. doi: 10.1257/jep.15.2.145.

Greenhalgh, C. and Rogers, M. (2007) ‘The value of intellectual property rights to firms and society’, Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 23(4), pp. 541–567. doi:

10.1093/oxrep/grm035.

Griliches, Z. (1990) ‘Patent Statistics as Economic Indicators: A Survey.’, Journal

of Economic Literature, 28(4), pp. 1661–1707. doi: 10.1016/S0169-7218(10)02009-5.

Griliches, Z., Hall, B. H. and Pakes, A. (1991) ‘R&D, Patents, and Market Value Revisited: Is There A Second (Technological Opportunity) Factor?’, Economics of

Innovation and New Technology, 1(3), pp. 183–201. doi: 10.1080/10438599100000001.

30

internal credit ratings’, Journal of Banking and Finance, 29, pp. 509–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jbankfin.2004.05.017.

Hall, B. H. (2010) ‘The Financing of Innovative Firms’, Review of Economics and

Institutions, 1(1), pp. 1–30. doi: 10.5202/rei.v1i1.4.

Hall, B. H., Jaffe, A. and Trajtenberg, M. (2005) ‘Market Value and Patent Citations’, The RAND Journal of Economics, 1, pp. 16–38.

Hall, R. (1992) ‘The Strategic Analysis of Intangible Issues’, Strategic

Management Journal, 13(2), pp. 135–144. doi: 10.1002/smj.4250130205.

Hechavarría, D. M., Matthews, C. H. and Reynolds, P. D. (2016) ‘Does start-up financing influence start-up speed? Evidence from the panel study of entrepreneurial dynamics’, Small Business Economics, 46(1), pp. 137–167. doi: 10.1007/s11187-015-9680-y.

Hogan, T. and Hutson, E. (2005) ‘Capital structure in new technology-based firms: Evidence from the Irish software sector’, Global Finance Journal, 15(3), pp. 369–387.

Hogan, T., Hutson, E. and Drnevich, P. (2016) ‘Drivers of External Equity Funding in Small High-Tech Ventures’, Journal of Small Business Management, 55(2), pp. 236–253. doi: 10.1111/jsbm.12270.

Hughes, A. and Mina, A. (2010) The Impact of the patent system on SMEs. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge, Centre for Business Research.

Inderst, R. and Vladimirov, V. (2016) ‘Financing Choices When Investors Can Become Dominant’, in Cambridge Endowment for Research in Finance: Corporate

Finance Theory Symposium. Cambridge, UK.

Jensen, M. C. and Meckling, W. H. (1976) ‘Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure’, Journal of Financial Economics, 3, pp. 305–360. doi: 10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X.

Jensen, P. H. and Webster, E. (2006) ‘Firm size and the use of intellectual property rights’, Economic Record, 82(256), pp. 44–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4932.2006.00292.x.

Kannebley, S., Sekkel, J. V. and Araújo, B. C. (2010) ‘Economic performance of Brazilian manufacturing firms: A counterfactual analysis of innovation impacts’, Small

31

Business Economics, 34(3), pp. 339–353. doi: 10.1007/s11187-008-9118-x.

Kaplan, S. N. and Strömberg, P. (2003) ‘Financial contracting theory meets the real world: An empirical analysis of venture capital contracts’, Review of Economic

Studies, 70(2), pp. 281–315. doi: 10.1111/1467-937X.00245.

Kor, Y. Y. and Mahoney, J. T. (2004) ‘Edith Penrose’s (1959) Contributions to the Resource-based View of Strategic Management’, Journal of Management Studies, pp. 183–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2004.00427.x.

Kraft, P. (2015) ‘Rating Agency Adjustments to GAAP Financial Statements and Their E ↵ ect on Ratings and Bond Yields’, The Accounting Review, 90(2), pp. 641–674. doi: 10.2308/accr-50858.

Lahr, H. and Mina, A. (2015) ‘The pecking order of innovation finance’, in

Academy of Management Proceedings.

Leary, M. T. and Roberts, M. R. (2010) ‘The pecking order, debt capacity, and information asymmetry’, Journal of Financial Economics, 95(3), pp. 332–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jfineco.2009.10.009.

Lemmon, M. L. and Zender, J. F. (2010) ‘Debt Capacity and Tests of Capital Structure Theories’, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 45(5), pp. 1161– 1187. doi: 10.1017/S0022109010000499.

Lev, B. (2002) ‘Where have all of Enron ’ s intangibles gone ?’, Journal of

Accounting and Public Policy, 21, pp. 131–135.

Lintner, J. (1965) ‘The Valuation of Risk Assets and the Selection of Risky Investments in Stock Portfolios and Capital Budgets’, The Review of Economics and

Statistics, 47(1), p. 13. doi: 10.2307/1924119.

Lockett, A. and Thompson, S. (2004) ‘Edith Penrose’s Contributions to the Resource-based View: An Alternative Perspective’, Journal of Management Studies, pp. 193–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6486.2004.00428.x.

Lööf, H. and Heshmati, A. (2006) ‘On the relationship between innovation and performance: a sensitivity analysis’, Economics of innovation and new technology, 15(4– 5), pp. 317–344.

32

López-Gracia, J. and Sogorb-Mira, F. (2008) ‘Testing trade-off and pecking order theories financing SMEs’, Small Business Economics, 31(2), pp. 117–136. doi:

10.1007/s11187-007-9088-4.

Lotti, F., Santarelli, E. and Vivarelli, M. (2003) ‘Does Gibrat’s law hold among young, small firms?’, Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 13(3), pp. 213–235. doi: 10.1007/s00191-003-0153-0.

Mansfield, E. (1986) ‘Patents and Innovation: An Empirical Study’, Management

Science, 32(2), pp. 173–181. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.32.2.173.

Mina, A., Lahr, H. and Hughes, A. (2013) ‘The demand and supply of external finance for innovative firms’, Industrial and Corporate Change, 22(4), pp. 869–901. doi: 10.1093/icc/dtt020.

Minola, T., Cassia, L. and Criaco, G. (2013) ‘Financing patterns in new

technology-based firms: An extension of the pecking order theory’, International Journal

of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 19(2), pp. 212–233. doi:

10.1504/IJESB.2013.054964.

Modigliani, F. and Miller, M. H. (1958) ‘The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and the Theory of Investment’, The American Economic Review, 48(3), pp. 261–297.

Del Monte, A. and Papagni, E. (2003) ‘R&D and the growth of firms: empirical analysis of a panel of Italian rms’, Research Policy, 32, pp. 1003–1014.

Murphy, G., Trailer, J. and Hill, R. (1996) ‘Measuring Research Performance in Entrepreneurship’, Journal of Business Research, 36(1), pp. 15–23. doi: 10.1016/0148-2963(95)00159-X.

Myers, S. C. (1977) ‘Determinants of corporate borrowing’, Journal of Financial

Economics, 5(2), pp. 147–175. doi: 10.1016/0304-405X(77)90015-0.

Myers, S. C. (1984) ‘The Capital Structure Puzzle’, The Journal of Finance, 39(3), pp. 575–592. doi: 10.1093/rfs/8.4.1185.

Myers, S. C. and Majluf, N. S. (1984) ‘Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have’, Journal of Financial