SHAHAB ZARE

User Innovators Journey to Entrepreneurship in the

Digital Economy

User Innovators Journey to Entrepreneurship in the

Digital Economy

Doctoral Dissertation of: Shahab Zare

To:

The Class of Social Sciences

For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of

Ph.D. in Management: Innovation, Sustainability, and Health care

Curriculum: Innovation Management

A.Y. 2019-2020

Supervisor: Alberto Di Minin

!"ﻦ

$%

ﻦ &

زه ﺑ*

ﻮ & د

و .ﮫﺎ

ن &

زه 2

ﻮد

وا ر5

ﺪ از

7ﺪ .

ﮫﺎ

ن 8

ﯽ 7

ﺪ و ا:

ﺪازه

2ﻮد

Rumi

Acknowledgments

The Ph.D. journey I undertook at Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies was no different than other Ph.D. students’ experiences. I recall in detail and imagination the first day of our commencement when I met my colleagues who then became true friends and my supervisors. I was ready and eager to learn new concepts, new culture and to undertake new experiences. I was fortunate to have my beloved person always near myself who two years after became my wife. If not all, but most of my acknowledgments is dedicated to my wife, Reyhaneh, who supported me and accompanied me on this long journey. I know that sometimes, the days weren’t joyful to you, but you know that the true men will remember their oath, and I won’t do anything less than to make you smile.

I would like to appreciate my family for their patience, support, and energy they gave me. Even if our physical distance is far, you are always in my heart, and I will do my best to make you proud.

Picca, in the first years of my Ph.D. studies you were always beside me, you gave me your time to have a talk, suggestions, and feedback. That was precious to me. Thank you!

I should also express my gratitude to Alberto who helped me in understanding how real research can be formed. Thank you, Alberto, for your insights regarding my Ph.D. dissertation. You will always stick to my mind as a person who can carry out several activities together while his mind is focused on a speech, that’s genius and has been always inspirational to me! Clearly, I share a three years period of studying and learning with my friends. They have been part of this game. Daniel, Deepa, Fabio, Francesca, and Gaia, you were the first Italians whom I happened to know in Pisa. And Italy should be happy about having you as citizens who represent the beauty of this beautiful country. I am challenging myself to exclude Daniel as an Italian and call him Romanian, but anyway, he was the very first person I encountered at Sant’Anna when he was near the main door of the school. Buddy, you were able to “recognize” (/ˈrɛkəɡnʌɪz/) me in the square by having me seen from a photo, considering you as an “ignorante” who is suffering from vision deficiency, that’s smart. But honestly, you impressed me with your intelligence during these three years. Franci, I do remember when you and “brutto” tried convincing me that life is better in Pisa than Como whenever I was nagging! Well, you were right, although Como is more beautiful than Pisa, I didn’t have sincere friends like you in Como.

I would like to thank my other friends from our research group who were helpful, kind, and supportive. I should start with you, “Giulio”, you are a true friend who didn’t hesitate to give me intellectual supports for my research and career. Valentina, your kindness together with your “ciliegine” will remain in my mind. Claudia, thank you for the “Pasticciotti” and sorry for the extra requests I may have had from you. Chiara, I am still waiting for your response on WhatsApp, can you explain to me more about your paper’s methodology? Maral, I was fortunate to have an Iranian fellow who did her Ph.D. here, thank you for sharing your thoughts about my research several times! I need to thank Herica, and Cristina, thank you both for helping me by sharing your experiences and some papers which helped me to overcome the dizziness of my Ph.D.

I would like to thank scholars whose knowledge took me to today’s condition. Eric von Hippel‘s scripts have always brought me joy and motivated me to work in this field. It was a real pleasure having met him during the OUI Conference 2019. His encouragement for my research and his assurance to it gave me more confidence to continue in this path more passionately. Martin Kenney, whose lecture on the digital economy opened up insights and research questions that I liked to pursue. I would like to thank the reviewers of my thesis, Professor Guido Bortoluzzi and Professor Mattia Bianchi for their constructive comments which helped me to improve the quality of this thesis.

Last but not least, I would like to thank Christopher Lettl and his research group at WU for their time, efforts and insights about my research.

Table of Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... 6 LIST OF TABLES ... 10 LIST OF FIGURES ... 11 LIST OF ACRONYMS ... 12 INTRODUCTION ... 14FROM USER INNOVATION TO USER ENTREPRENEURSHIP THROUGH THE LENS OF OPPORTUNITY IDENTIFICATION AND EFFECTUATION THEORIES ... 14

ADJUSTMENT TO THE STATUS QUO AND SHIFTING TOWARD ENTREPRENEURSHIP ... 16

SCOPE OF THE DISSERTATION ... 18

STRUCTURE OF THE DISSERTATION ... 19

Chapter 1. Opportunity identification for entrepreneurs with different sources of knowledge ... 19

Chapter 2. User Entrepreneurs and Their Path Toward Opportunity Identification: Foundations and Empirical Evidence ... 21

Chapter 3. The Way Users Do Business; Decision-making Processes of User Entrepreneurs Through the Lens of Effectuation Theory ... 21

References ... 24

CHAPTER 1: OPPORTUNITY IDENTIFICATION FOR ENTREPRENEURS WITH DIFFERENT SOURCES OF KNOWLEDGE ... 29

ABSTRACT ... 29

1.1. INTRODUCTION ... 30

1.2. LITERATURE REVIEW ... 31

1.2.1. Opportunity Identification ... 31

1.2.1.1. Opportunity Creation Theory ... 31

1.2.1.2. Opportunity Discovery Theory ... 33

1.2.2. Entrepreneurship and Sources of Knowledge ... 34

1.2.2.1. Employee Entrepreneurship ... 34

1.2.2.2. Academic Entrepreneurship ... 36

1.2.2.3. User Entrepreneurship ... 38

1.3. CONCLUSION ... 42

1.4. REFERENCES ... 43

CHAPTER 2: USER ENTREPRENEURS AND THEIR PATH TOWARD OPPORTUNITY IDENTIFICATION: FOUNDATIONS AND EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE ... 47

ABSTRACT ... 47

2.1. INTRODUCTION ... 48

2.2. LITERATURE REVIEW ... 50

2.2.1. User Innovation ... 50

2.2.2. From User Innovation to User Entrepreneurship ... 52

2.2.3. Opportunity Identification ... 53

2.3. METHODOLOGY ... 54

2.3.1. Context of the Research ... 55

2.3.2. Research Design and Setting ... 59

2.3.2. Data collection and Analysis ... 60

Case 1. Drivania ... 63

Case 2. GoOpti ... 63

Case 3. King of App ... 64

Case 4. Sensefinity ... 65

2.4. DISCUSSION ... 69

Opportunity Discovery ... 70

Opportunity Creation ... 70

End User Entrepreneur ... 70

Professional User Entrepreneur ... 70

2.5. CONCLUSION ... 72

2.6. REFERENCES ... 74

ANNEXES ... 79

CHAPTER 3: THE WAY USERS DO DIGITAL BUSINESS; DECISION-MAKING PROCESSES OF USER ENTREPRENEURS THROUGH THE LENS OF EFFECTUATION THEORY ... 81 ABSTRACT ... 81 3.1. INTRODUCTION ... 83 3.2. LITERATURE REVIEW ... 86 3.2.1. User Entrepreneurship ... 86 3.2.2. Effectuation Theory ... 89

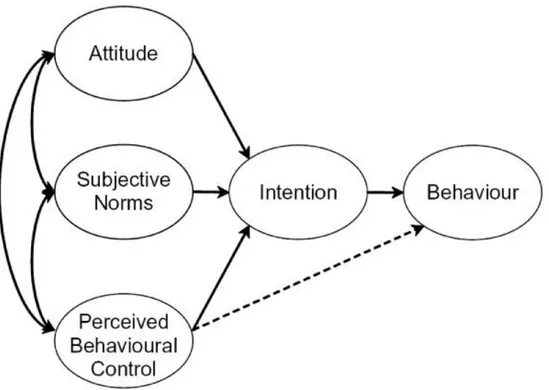

3.2.3. Theory of Planned Behaviour ... 93

3.3. METHODOLOGY ... 94

3.3.1. Research Design and Setting ... 94

3.3.2. Data Collection and Analysis ... 97

3.4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ... 99

Case 1. Atbox ... 99 Case 2. Bimebazar ... 100 Case 3. Drivania ... 100 Case 4. Eventbox ... 101 Case 5. Fullfekr ... 102 Case 6. GoOpti ... 102 Case 7. KingofApp ... 103 Case 8. Sensefinity ... 103 Case 9. Socialdiabetes ... 104

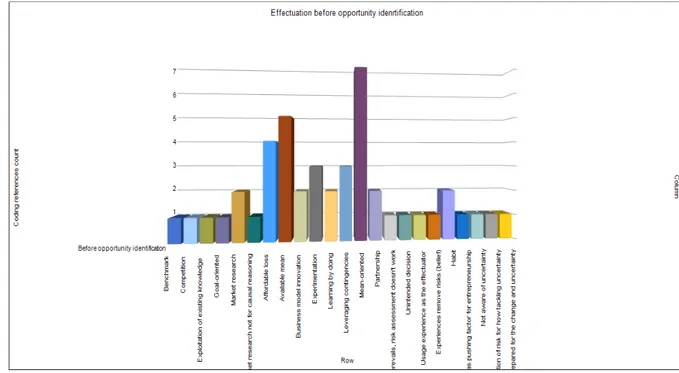

3.4.1. Before opportunity identification ... 108

3.4.2. Between opportunity identification and opportunity exploitation ... 110

3.4.3. Between opportunity exploitation and fundraising ... 112

3.4.4. After fundraising ... 114

3.4.5. Contextual Differences ... 116

3.4.5.1. Subjective Norms as The False Flags ... 120

3.4.5.2. Substantial Change in Attitude ... 121

3.4.5.3. Perceived Behavioral Control: Decreased Self-esteem; Toward External Locus of Control .. 123

3.4.6. User Entrepreneurship Classifications Difference ... 124

3.4.7. Lead users Motivations Toward Entrepreneurship ... 125

3.5. CONCLUSION ... 127

3.6. REFERENCES ... 131

ANNEXES ... 137

CONCLUSION ... 139

Dominant Determinants of Opportunity Identification for Diverse Types of Entrepreneurs ... 140

Results ... 141

User Entrepreneurs and the Discovery Paradigm of Opportunities ... 142

Results ... 142

User Entrepreneur’s Decision-making Under Uncertainty ... 143

Results ... 143

Contributions ... 144

Scientific Implications ... 145

Managerial and Policy Implications ... 146

List of Tables

TABLE 1-SAMPLE INFORMATION ... 62

TABLE 2-USER ENTREPRENEUR CLASSIFICATIONS BY THE OPPORTUNITY IDENTIFICATION THEORIES ... 70

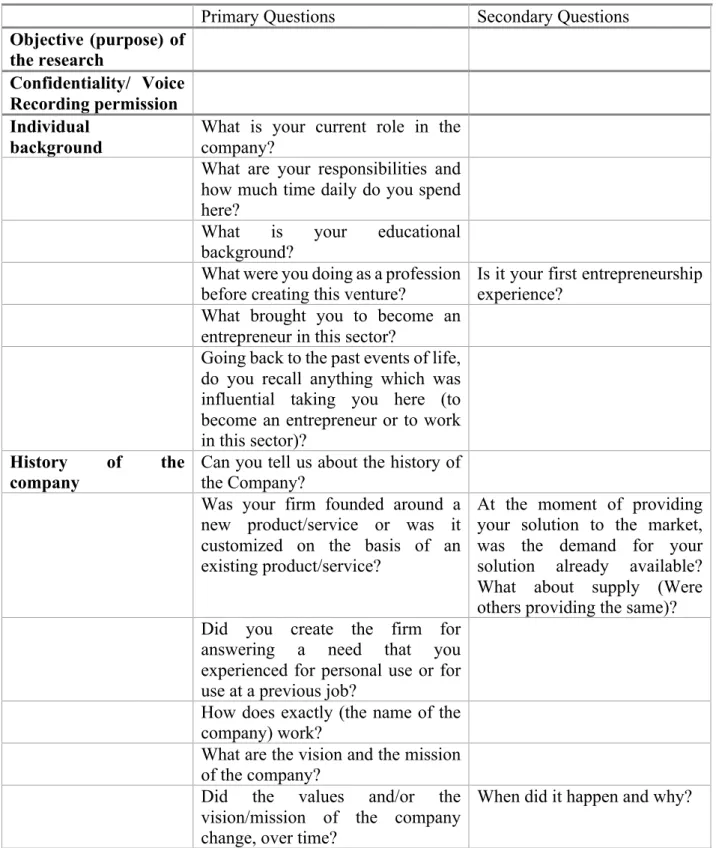

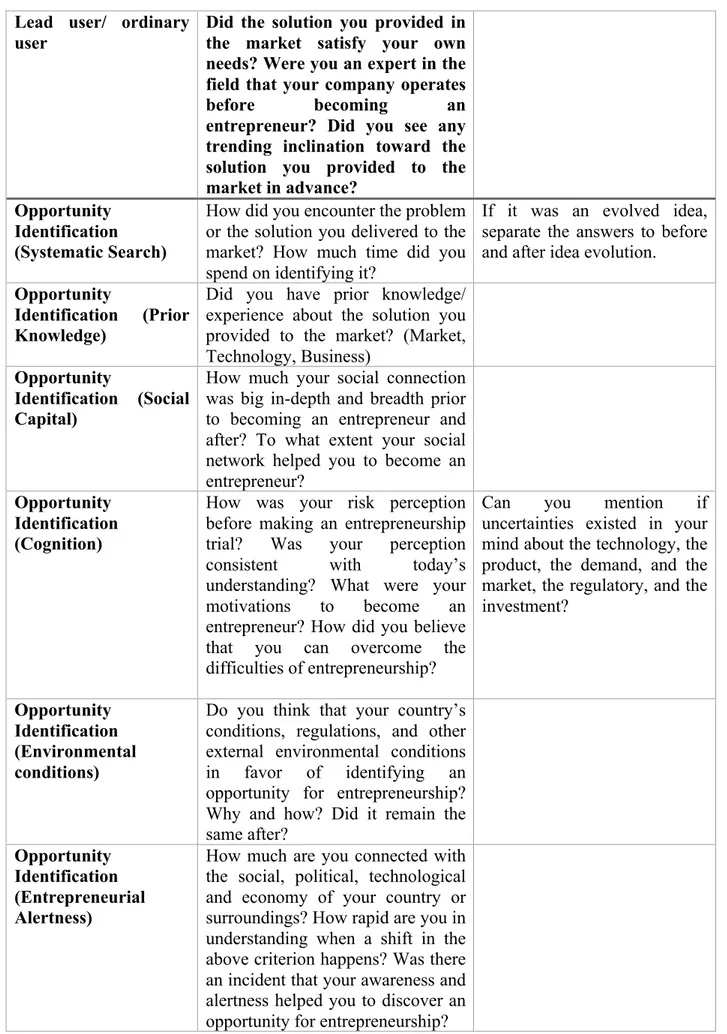

TABLE 3-INTERVIEW PROTOCOL OF THE RESEARCH ... 79

TABLE 4-INTERVIEW PROTOCOL OF THE RESEARCH (CONTINUED) ... 80

TABLE 5-BASIC DIFFERENCES BETWEEN CAUSATION &EFFECTUATION,(ADAPTED FROM PEREIRA ET AL., 2017) ... 91

TABLE 6-BASIC INFORMATION OF THE SAMPLE ... 106

TABLE 7-BASIC INFORMATION OF THE SAMPLE (CONTINUED) ... 107

TABLE 8-INTERVIEW PROTOCOL OF THE RESEARCH ... 137

List of Figures

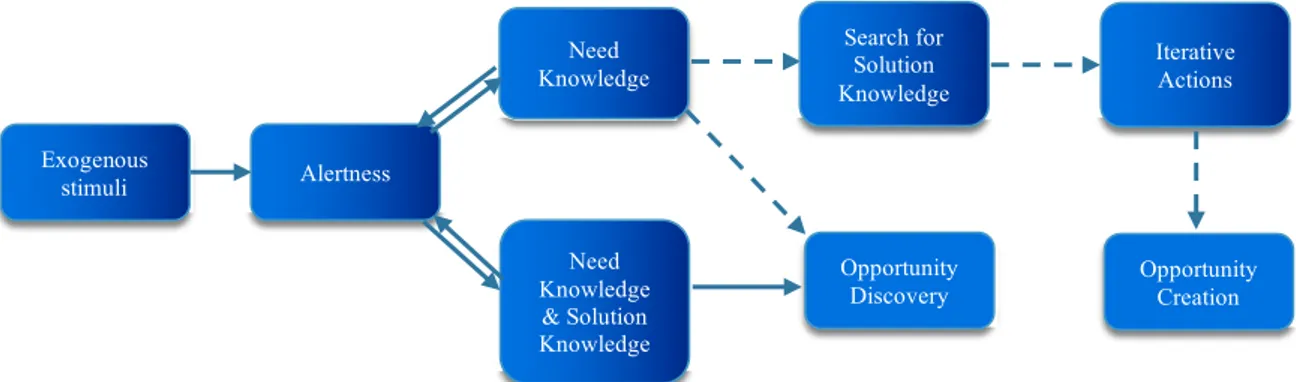

FIGURE 1.CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK ... 55

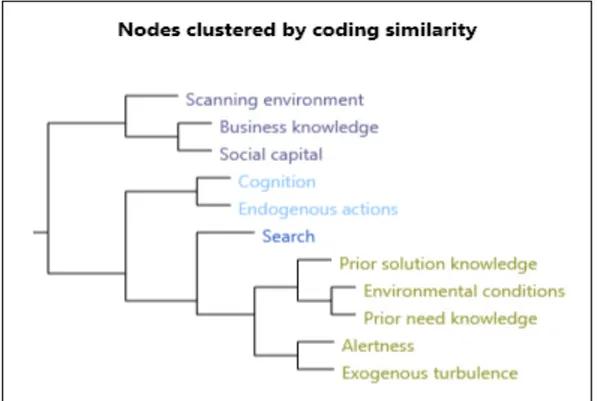

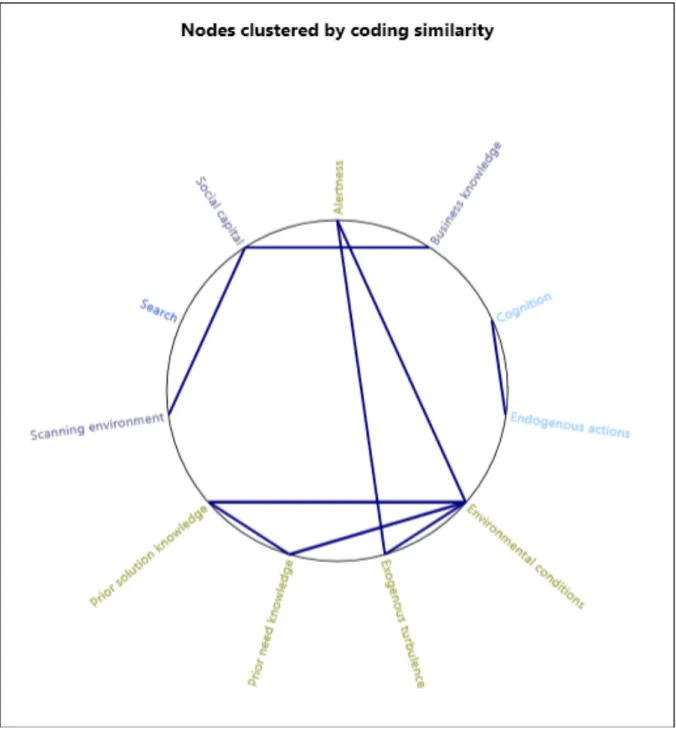

FIGURE 2-CLUSTER ANALYSIS OF CODING SIMILARITY ... 68

FIGURE 3-PROXIMITY OF NODES ... 68

FIGURE 4-NODES RELATIONSHIP ESTIMATED BY JACCARD'S COEFFICIENT ... 69

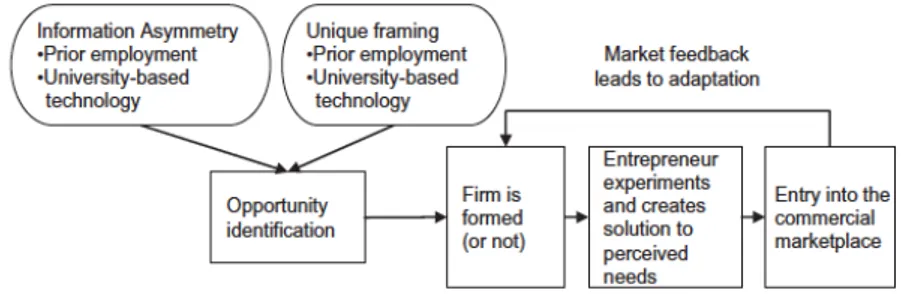

FIGURE 5-CLASSIC MODEL OF ENTREPRENEURSHIP (ADAPTED FROM SHAH &TRIPSAS,2007) ... 88

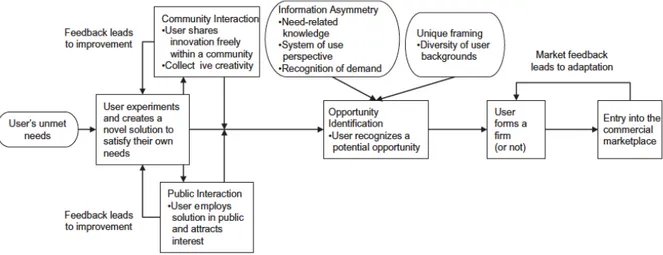

FIGURE 6-USER ENTREPRENEURSHIP MODEL (ADAPTED FROM SHAH &TRIPSAS,2007) ... 89

FIGURE 7-THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOUR, ADAPTED FROM AJZEN,1991 ... 93

FIGURE 10-DECISION-MAKING OF FOUNDERS BEFORE OPPORTUNITY IDENTIFICATION ... 109

FIGURE 11-DISTRIBUTION OF EFFECTUATION DECISIONS AND CAUSATION DECISIONS BEFORE OPPORTUNITY IDENTIFICATION ... 110

FIGURE 12-DECISION-MAKING OF FOUNDERS BETWEEN OPPORTUNITY IDENTIFICATION AND OPPORTUNITY EXPLOITATION ... 111

FIGURE 13-DISTRIBUTION OF EFFECTUATION DECISIONS AND CAUSATION DECISIONS BETWEEN OPPORTUNITY IDENTIFICATION AND OPPORTUNITY EXPLOITATION ... 111

FIGURE 14-DECISION-MAKING OF FOUNDERS BETWEEN OPPORTUNITY EXPLOITATION AND FUNDRAISING . 113 FIGURE 15-DISTRIBUTION OF EFFECTUATION DECISIONS AND CAUSATION DECISIONS BETWEEN OPPORTUNITY EXPLOITATION AND FUNDRAISING ... 113

FIGURE 16-DECISION-MAKING OF FOUNDERS AFTER FUNDRAISING ... 115

FIGURE 17-DISTRIBUTION OF EFFECTUATION DECISIONS AND CAUSATION DECISIONS AFTER FUNDRAISING 115 FIGURE 18-DISTRIBUTION OF EFFECTUATION DECISIONS AND CAUSATION DECISIONS FOR THE IRANIAN CASES ... 116

FIGURE 19-DISTRIBUTION OF EFFECTUATION DECISIONS AND CAUSATION DECISIONS FOR THE EUROPEAN CASES ... 117

FIGURE 20-DISTRIBUTION OF EFFECTUATION DECISIONS AND CAUSATION DECISIONS FOR THE IRANIAN CASE BEFORE OPPORTUNITY EXPLOITATION ... 118

FIGURE 21-DISTRIBUTION OF EFFECTUATION DECISIONS AND CAUSATION DECISIONS FOR IRANIAN CASES AFTER OPPORTUNITY EXPLOITATION ... 118

FIGURE 22-DISTRIBUTION OF EFFECTUATION DECISIONS AND CAUSATION FOR EU BEFORE OPPORTUNITY EXPLOITATION ... 119

FIGURE 23-DISTRIBUTION OF EFFECTUATION DECISIONS AND CAUSATION FOR EU AFTER OPPORTUNITY EXPLOITATION ... 119

FIGURE 24-DISTRIBUTION OF EFFECTUATION DECISIONS AND CAUSATION FOR THE END USER ENTREPRENEURS ... 124

FIGURE 25-DISTRIBUTION OF EFFECTUATION DECISIONS AND CAUSATION FOR THE PROFESSIONAL USER ENTREPRENEURS ... 125

FIGURE 26-NUMBER OF EVENTS THAT ENTREPRENEURS DECLARED THEIR NON-MONETARY MOTIVATION TO BECOME AN ENTREPRENEUR ... 126

List of Acronyms

ACRONYM ABBREVIATED EXPRESSION

3DP 3D Printing

API Application Program Interface

B2B Business-to-Business

B2C Business-to-Consumer

B.SC. Bachelor of Science

CEO Chief Executive Officer

CMS Content Management System

EIB European Investment Bank

EU European Union

GDP Gross Domestic Product

IOT Internet of Things

IP Intellectual Property

IT Information Technology

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

POTUS President of The United States

PH.D. Philosophiae Doctor

PHOSITA Person Having Ordinary Skill In The Art

Q/A Questions/Answers

R&D Research & Development

SME Small & Medium-sized Enterprise

SMEI SME Instrument

SWOT Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats

TPB Theory of Planned Behaviour

UI User Interface

USD United States Dollar

Introduction

From User Innovation to User Entrepreneurship Through the

Lens of Opportunity Identification and Effectuation Theories

The progress of human being’s life in the past was in the hands of individuals who pioneered to understand and move forward the knowledge, science, and technology. There were ordinary people and scientists who for the sake of humanity and their intrinsic needs attempted to observe the surroundings and create/discover novel solutions to tackle difficulties (Roberts, 1989). This encompassed a wide range of goods from fire to wheels to textile to shoes to paper and alcohol. Even if all of the human being’s inventions seem to be a result of the collective action of peers, they were designed and built to satisfy the primary need of individuals (Wootton, 2015).As time flew, this collective action was designed to occur by a pre-defined plan based on the request of a leader. Therefore, it was supposed more efficient to contrive an establishment for the scientists to co-work together and advance the science. Universities became the locus where collective wisdom can enhance knowledge and bring prosperity. It went further and corporations created a similar agenda to absorb the recent advancements of science and technology and to be able to exploit them more efficiently (Beer, 1959; Freeman, 1995; Hughes, 1989). Through these activities, science rapidly progressed and became more focused based on the entity's direction plan. However, for some particular events, there was no need defined by the market and the scientists pushed the growth of knowledge (Chidamber & Kon, 1993). These became the principles of science evolvement. Consequently, it created a distance to the old-fashioned style of science progress resulting in invention happenings. It seemed off-limits and disorganized if the newly introduced goods were not announced as the product of research and development either happened within universities or R&D labs even if the concept of the new product was adapted from an available amateur (detached from labs) solution (Freeman, 1995).

Eric von Hippel in his primary research in the late seventies found that the push pattern for science and technology is not the dominant method of science development (von Hippel, 1976; 1978). He has noted that in many industries, the innovations sprung into existence from

ordinary users who for the sake of their own needs created an artifact that can satisfy themselves. Then that superficial and (often) unprofessional solution became the prototype for the corporations to build a more complete version of what customers want. Thus, the users were introducing important latent needs that have not been discovered by the incumbent corporations (von Hippel, 1988). These implications emerged by the users in the shape of a new product or a new service is referred to as “User Innovation” (von Hippel, 2005). The introduction of their products ignited R&D labs to hear more from what the users exactly need (von Hippel. 1986). However, as in research, we call, “the stickiness of information” is the inhibitor that hinders the ability of corporations to be able to extract what users need. In another explanation, user innovation scholars believe that the users have the “need knowledge” which lacks the “solution knowledge” that manufacturers carry out (von Hippel, 1994).

Though, in academia, there have been attempts trying to tackle this difficulty and to study how this distance can be reduced or smoothened (Tyre & von Hippel, 1997; von Hippel, 1998). Accordingly, corporations adopted some strategies to be collaborating with their users more than before. These include crowdsourcing initiatives, toolkits for user innovation, assembling workshops with the lead users, mass-customization, and having virtual communities (Boudreau & Lakhani, 2013; Howe, 2006; Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2002; Sawhney & Prandelli, 2000; von Hippel et al., 1999; von Hippel, 2001). The aforementioned subjects are the elements of open innovation designed to reduce the gap between the corporations and their users for the matter of new product/service development. In other words, with such facilities, the new knowledge can be (co) created and the new solutions comprise both technology push and market pull information.

Today’s economy is greatly influenced by the service industries and huge shares of each country’s GDPs are related to the service sector (U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2019; Oliveira & von Hippel, 2011). The same pattern of knowledge creation which demonstrated above exists in this context too. Studying the history of banking does not lead us to when universities and R&D labs existed. It was not thanks to the collective enactments of a group of people gathered together making plans for what to do for the well-being of society. Rather, it was wealthy people who created this type of micro-institutions to lend money and to ask for interests or some commodity in return in ancient Babylon and ancient Rome (Dandamaev & Lukonin, 2004).

style. However, again, there became a distance between what users want and what banks were attempting to deliver as of their services. This resulted in users taking actions and to provide some solutions to satisfy their own needs (Oliveira & von Hippel, 2011).

Adjustment to The Status Quo and Shifting Toward

Entrepreneurship

Recent technological developments in the digital sector have made it sweat heaven for the users to rule and to push corporations to move toward providing what they desire (Altman & Tushman; 2017). This disruption took corporations one step further and facilitated the process of having a deeper dialogue with their users. While users became more powerful in finding more frequent innovations by the corporations as they wished, they started to notice the low cost of self-providing a solution for their need via digital tools. In other words, the unanswered needs may be easier entered into the real world thanks to the availability of digital tools (Hull et al., 2007). This could have done by the user itself only if she is capable of programming or can be outsourced to a programmer. This innovation which was aimed to satisfy a user’s need may be the value proposition for an entrepreneurship case. It is not anymore a prototype that is limited to time, space, and quantity. Perhaps, it is not professionally designed but it is accessible all across the World Wide Web. The economy in which the operand and the operant resources are connected through digital tools is called “Digital Economy” (Tapscott, 1996).

“User Entrepreneurship” is defined as the commercialization of the innovations that users have carried out for the sake of their usage in its first place (Shah & Tripsas, 2007). Users traditionally (or intrinsically) shared their prototype (solution) with their peers to receive feedback and to increase the joy and satisfaction of using the product (Sawhney & Prandelli, 2000; von Hippel, 2001). They may get informed of a commercialization opportunity when the surrounding community shares their positive reactions concerning the prototype (Shah & Tripsas, 2007). The underlying logic behind this public exposure is to reduce the costs and the associated risks for (mass) producing the product. Therefore, there seems to be a higher propensity for users in the digital sector to base their innovations as a path toward commercialization than mere relief to their needs.

A considerable stream of research is trying to understand and to explain better how the individuals identify and spot such opportunities (Ardichivili et al., 2003; Foss & Klein, 2018;

Gaglio, 2018; Kirzner, 1979; Schumpeter, 1934; Shane, 2000; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). While some emphasize the exogenous shocks and turbulence in the market/industry/technology as the pushing factor of identifying opportunities, some scholars believe that the emphasis should be on the actions, reactions, and enactments of individuals (Alvarez & Barney, 2007). This resulted in two different explanations that economists divide upon it. While some economists contemplate that these theories are incommensurable, others support the possibility of their co-existence (Suddaby et al., 2015). It is indeed important for the scholarship to understand whether different sources of knowledge for entrepreneurship can influence how individuals identify opportunities according to these theories.

The clear case of user entrepreneurship in the service-based digital economy is Yahoo! whose founders were urged to remind the directory of the scarce number of websites on the World Wide Web (Clark, 2008). The opportunity for entrepreneurship born when they wanted to answer their own need. Iranian giant e-commerce platform “Digikala” was born when their founders had a great difficulty trusting the market resellers’ suggestions for buying a professional digital camera in 2005. Their unpleasant experience made them providing a platform in which ordinary users together with the (firm’s) experts could have reviewed every digital product (Guttman, 2015). These two examples are a few out of numerous user entrepreneur cases in the service-based digital economy as we theoretically believe that the users are prone to founding a firm in such a setting.

The interesting point regarding these two examples is that none of them were planning to do what they are performing today as routine activities. Both of them relied on what they knew and started their business upon it. Both were relying on their assets until when it attracted VC attention to invest in their solutions. In other words, as Sarasvathy explains in her theory of effectuation, they were mean-oriented than focusing on an explicit goal. And that is why they leveraged on the contingencies and their business model is drastically different than what they announced in the very early days. Sarasvathy bases the theory of effectuation on the Knightian theory of uncertainty and she explains that as in the business world we face uncertain situations more often than a predictable risky situation, hence, a substantial number of entrepreneurs make effectual decisions than causal decisions (Sarasvathy, 2001; 2009).

Scope of the Dissertation

The academic debate on user entrepreneurship is still in an early stage phase and the researchers have conducted similar approaches to study this scholarship as for the user innovation phenomenon (Agarwal & Shah, 2014; Shah & Tripsas, 2007; 2016). Most of the studies have undergone an investigation for the product-related matters and new technologies have barely been under the spotlight for the user innovation/ user entrepreneurship topic (Adams et al., 2013; Baldwin et al, 2006; Shah, 2005; Shah & Mody, 2014; Shah & Torrance, 2013; Shah & Tripsas, 2007; Tripsas, 2008; Smith & Shah, 2013).

Besides, most of the studies have been exploring the phenomenon without having a clear contribution to a theory of entrepreneurship. This is partly because the entrepreneurship field is still growing and there are lots of undiscovered facets that need to be studied (Suddaby et al., 2015). There are lack of knowledge for how ideas in the digital economy are becoming a value proposition of some firms? Does the role of science-push and market-pull innovations affect the commercialization phenomenon in this sector similarly? Do the user’s contributions play a significant role here? If yes, to what extent? And finally, how do the users employ their knowledge and commercialize their solutions in this sector? There are indeed a handful of papers in the User Entrepreneurship field undertaking a great effort for engaging theories with the phenomenon clamping them together (Haefliger et al, 2010; Shah & Tripsas, 2016). In addition, most of the policies concerning the digital economy are in favor of a centralized command to foster innovations (Etzkowitz & Zhou, 2018). Evidence for this claim is the distribution of science and technology parks near to the universities. While geographical proximity of science and technology parks to the R&D labs and universities seem to be in favor of promoting new knowledge, there is doubt, in our viewpoint, the effectiveness of such policies to foster innovations that are the result of a market pull idea (which we believe is a result of user innovation). The science and technology parks help the promotion of knowledge after the firm formation but are they efficient in absorbing those contributors who encounter latent needs (user entrepreneurs)?

Hence, in this dissertation, by adopting theories of opportunity discovery/opportunity creation (Alvarez & Barney, 2007) and effectuation theory (Sarasvathy 2001), it is intended to describe the transforming process of user innovation to user entrepreneurship phenomenon. Moreover, the focus of this dissertation is on the intersection of the digital economy with the service industry (Kenney & Zysman, 2016). Consequently, this thesis aims to answer to the general

question: How do the user innovators become user entrepreneurs in the service-based digital

economy? What are the implications of this phenomenon to the established centralized policies?

Structure of the Dissertation

To explain the big picture of user entrepreneurship in the service-based digital economy and to answer the aforementioned question, we need to provide the basic explanations of the phenomena and the theories. Therefore, in the first chapter, we intend to understand how (business) opportunities could be identified by entrepreneurs. As the focus of this dissertation is on the user entrepreneurship and while one of the main differences of this entrepreneurship classification with others is based on the source of their knowledge, we attempt to theoretically study opportunity identification among entrepreneurs with different source of knowledge (Agarwal & Shah, 2014; Alvarez & Barney, 2007).

Further, in the second chapter, the focus is on the user entrepreneurs and we aim to empirically investigate how they have identified opportunities according to the opportunity discovery and opportunity creation theories. Besides, the dynamics of this phenomenon in the digital economy will be explained (Shah & Tripsas, 2007; Alvarez & Barney, 2007).

In the last chapter, user entrepreneurship would be studied by adopting the theory of effectuation (Sarasvathy, 2001; 2009). Like the second chapter, a qualitative research method has been employed to investigate how the user entrepreneur’s decision-making based on the effectuation theory would help them to enter and to sustain.

This thesis is mostly contributing to user innovation/user entrepreneurship, effectuation, and opportunity identification scholarships. Nevertheless, as the selected cases of the second and the third chapters are some service-based digital economy companies, it also contributes to the literature on the digital economy. Further, the managerial implications are discussed, however, the implications are more toward policy-makers and individuals who wish to become entrepreneurs.

The following paragraphs present the framework of the dissertation, giving a summary of each document by tackling the research questions and their respective methodologies.

Chapter 1. Opportunity identification for entrepreneurs with different sources of knowledge

This article is a review of the literature to understand how three different types of entrepreneurship that prior literature speaks frequently about, identify business opportunities. These types are defined based on prior sources of knowledge. According to the previous studies, each of these entrepreneurship types has its distinguished effects on the economy (Agarwal & Shah, 2014). What scholars have not spoken about, is the pre-startup phase (i.e. opportunity identification) for these entrepreneurship types. Studying this phenomenon will enable policy-makers to provide suitable conditions to flourish entrepreneurship.

Different schools of thought in economics resulted in two different explanations of how opportunities are identified. While Schumpeter emphasized the ability of individuals creating destruction to the status quo of the market, Kirzner refers to the alertness of individuals making them capable of discovering market inequilibrium via some exogenous shocks (Kirzner, 1979; Schumpeter, 1934). The research questions that this paper aims to answer are:

• How do different types of entrepreneurship identify opportunities?

• Is each category distinct for the factors influencing them to either create or discover

opportunities?

This paper comprehends that the identification of opportunities for each type of entrepreneurship is not merely a product of their respective knowledge source. As explained by the scholars, prior knowledge is only one aspect that affects the opportunity identification process (Acs et al., 2009; Audretsch & Keilbach, 2007; Chiasson & Saunders; 2005). There are other factors such as personality traits and cognition of the entrepreneurs, social capital, entrepreneurial alertness, environmental conditions, and systematic search that play a role and some of these factors intertwine each other (George et al., 2014). Further, this study appreciates that the pure format of “user entrepreneurship”, “academic entrepreneurship”, and “employee entrepreneurship” rarely exists in reality and there seems to be a combination of knowledge sources that pushes an individual toward becoming an entrepreneur. However, this paper differentiates them from their prior and pure knowledge sources.

It is also noteworthy to mention that, these classifications are based on the opportunity and are not attributes to the entrepreneur’s belongings (e.g. an entrepreneur is an academic entrepreneur only when the offer and value proposition of her venture is based on an institutional research activity).

Chapter 2. User Entrepreneurs and Their Path Toward Opportunity Identification: Foundations and Empirical Evidence

Continuing the previous chapter’s theoretical understandings of how user entrepreneurs seem to identify opportunities, this paper pursues to empirically investigate this topic. Leveraging on the previous theories of when user entrepreneurs tend to enter an industry more, the service-based digital economy has been chosen to be the context of this chapter (Agarwal & Shah, 2014; Shah & Tripsas, 2016). While previous studies have shown that user entrepreneurs are a distinct type of entrepreneurship (Adams et al., 2013; Shah & Tripsas, 2007, Haefliger et al., 2010), there is a lack of understanding for how their usage experiences may result in opportunity identification. There is particularly scarce knowledge related to this phenomenon in the digital economy. As the dynamics of entrepreneurship in the digital economy are different to the old-fashioned settings, this paper investigates the primary factors leading to venture creation for this particular entrepreneurship in this context (De Marco et al., 2019; Giones & Brem, 2017; Nambisan, 2017; Nambisan & Baron, 2019). Therefore, this paper explores the concept of opportunity identification for user entrepreneurs in the digital era. Hence, the research question of this paper is the following.

• How do the user entrepreneurs identify opportunities?

A qualitative methodology using the case study method has been adopted to expand the primary knowledge about user entrepreneurship scholarship in the digital economy (Suddaby et al., 2015). A sample of five European SMEs has been finalized to be included in this paper complying with the context of our study. A semi-structured interview protocol was designed to address the pre-startup phase of venture creation by the entrepreneurs in this sector. It has been observed that the user entrepreneurs seemed to be affected more by the exogenous shocks and turbulence in the market, industry, and technology than some endogenous actions. This means that they are more prone to discover opportunities rather than creating them. This paper contributes more to the scholarship regarding the theories of opportunity identification, user entrepreneurship, and the digital economy. However, its findings also can facilitate policy-makers to provide the conditions for the user entrepreneurs to boost entrepreneurship in the digital economy.

Chapter 3. The Way Users Do Business; Decision-making Processes of User Entrepreneurs Through the Lens of Effectuation Theory

The progress toward the understanding of how user entrepreneurs identify opportunities raised another relevant issue of how they make decisions comprehending the risk and uncertainty in the business world. The novel theory of effectuation which has been constructed around two decades ago is developing and this paper aims to extend knowledge about this scholarship by examining how user entrepreneurs perceive uncertainties for venture creation. Prior studies have attempted to address the relationship of personality traits to the effectual decision-making style (Djuricic & Bootz, 2019; Jiang & Tornikoski, 2019; Mckelvie et al., 2011; Reymen et al., 2015). Users hold distinct characteristics and cognition for innovating and creating ventures (Agarwal & Shah, 2014; Shah & Tripsas, 2007; von Hippel; 2005). As shown in the previous chapter, they seem to discover opportunities more than creating them. Therefore it seems that they might follow a contrasting avenue for making decisions as entrepreneurs. Consequently, this paper would follow empirical groundings to answer the question of how would the users’

decision-making processes lead them to exploit an identified opportunity.

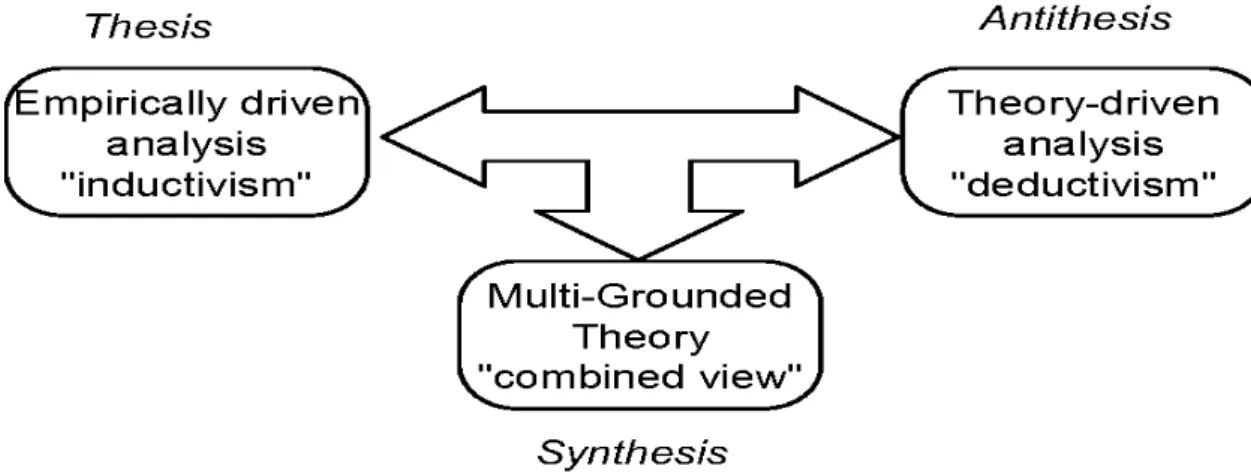

For answering the above question, it was required to collect primary information by making interviews with the founders of some firms. For the same reason as the previous chapter, this article pursued to study these attributes for the digital economy, as it was perceived to be a compelling sector for the user entrepreneurs to emerge. This article extends the knowledge regarding these phenomena beyond the developed countries and attempts to discover understudied developing countries too. Hence, five European SMEs together with four Iranian startups have been finalized to cover this chapter. Just like the previous chapter, this chapter collects data qualitatively through interviews and triangulation of external information (notes, interviews, website news, etc.), because this scholarship is at its infancy level and the aim is to create micro-theories regarding the phenomena (Suddaby et al., 2015). We used the multi-grounded theory research methodology to address the issue and provide new theoretical foundations to this research stream.

Drawing on the findings of this paper, it proposes some guidelines for the policy-makers regarding the notion of entrepreneurship in the digital economy. Further, this study contributes to the theory of effectuation by expanding its facet with regards to a prominent type of entrepreneurship. It has also contributions to the digital economy settings which push individuals to bring ideas into realities and becoming an entrepreneur. More importantly, digital economy settings being combined with the concept of user entrepreneurship have

brought us an important definition of user entrepreneurship in the digital era which seems to differ with the old-fashioned definition of user entrepreneurship that we are familiar with.

Each of the three chapters in this dissertation aims to address the underlying issue of how user entrepreneurs identify opportunities and how they exploit them based on their idiosyncratic essence. While in the first chapter, a theoretical emphasis was given to the effect of knowledge sources on opportunity identification, the next chapters continued to complement the basic theoretical understanding of opportunity identification and opportunity exploitation by compiling empirical evidence for the user entrepreneurs in the service-based digital economy. In the final section of the dissertation where it meets the conclusion, the limitations of the study will be reflected. Next, the potential research gaps will be mentioned and it will highlight the contributions to the academic and to the practice.

References

Acs, Z. J., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2009). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small business economics, 32(1), 15-30.

Adams, P., Fontana, R., & Malerba, F. (2013). The magnitude of innovation by demand in a sectoral system: The role of industrial users in semiconductors. Research Policy, 42(1), 1-14. Agarwal, R., & Shah, S. K. (2014). Knowledge sources of entrepreneurship: Firm formation by academic, user and employee innovators. Research policy, 43(7), 1109-1133.

Altman, E. J., & Tushman, M. L. (2017). Platforms, open/user innovation, and ecosystems: A strategic leadership perspective. In Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Platforms(pp. 177-207). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Alvarez, S. A., & Barney, J. B. (2007). Discovery and creation: Alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Strategic entrepreneurship journal, 1(1‐2), 11-26.

Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., & Ray, S. (2003). A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. Journal of Business venturing, 18(1), 105-123.

Audretsch, D. B., & Keilbach, M. (2007). The theory of knowledge spillover entrepreneurship. Journal of Management Studies, 44(7), 1242-1254.

Baldwin, C., Hienerth, C., & Von Hippel, E. (2006). How user innovations become commercial products: A theoretical investigation and case study. Research policy, 35(9), 1291-1313. Beer, J. J. (1959). The emergence of the German dye industry.

Boudreau, K. J., & Lakhani, K. R. (2013). Using the crowd as an innovation partner. Harvard

business review, 91(4), 60-9.

Chiasson, M., & Saunders, C. (2005). Reconciling diverse approaches to opportunity research using the structuration theory. Journal of business venturing, 20(6), 747-767.

Chidamber, S. R., & Kon, H. B. (1993). A research retrospective of innovation inception and success: the technology-push demand-pull question.

Clark, A. (2008, February 1). How Jerry's guide to the world wide web became Yahoo. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/business/2008/feb/01/microsoft.technology Dandamaev, M. A., & Lukonin, V. G. (2004). The culture and social institutions of ancient

Iran. Cambridge University Press.

De Marco, C. E., Di Minin, A., Marullo, C., & Nepelski, D. (2019). Digital platform innovation

in European SMEs. An analysis of SME Instrument Business Proposals and Case Studies (No.

Djuricic, K., & Bootz, J. P. (2019). Effectuation and foresight–An exploratory study of the implicit links between the two concepts. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 140, 115-128.

Etzkowitz, H., & Zhou, C. (2018). Innovation incommensurability and the science park. R&D

Management, 48(1), 73-87.

Foss, N., & Klein, P. (2018). Entrepreneurial Opportunities: Who Needs Them?. Academy of

Management Perspectives, (ja).

Freeman, C. (1995). The ‘National System of Innovation’in historical perspective. Cambridge

Journal of economics, 19(1), 5-24.

Gaglio, C. M. (2018). Opportunity identification: review, critique, and suggested research directions. In Reflections and Extensions on Key Papers of the First Twenty-Five Years of

Advances (pp. 1-47). Emerald Publishing Limited.

George, N. M., Parida, V., Lahti, T., & Wincent, J. (2016). A systematic literature review of entrepreneurial opportunity recognition: insights on influencing factors. International

Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(2), 309-350.

Giones, F., & Brem, A. (2017). Digital technology entrepreneurship: A definition and research agenda. Technology Innovation Management Review, 7(5).

Guttman, A. (2015, January 26). Meet The Twin Brothers Transforming How Iranians Shop. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/amyguttman/2015/01/26/twin-brothers-transforming-how-iranians-shop/#a3045b257aac

Haefliger, S., Jäger, P., & Von Krogh, G. (2010). Under the radar: Industry entry by user entrepreneurs. Research policy, 39(9), 1198-1213.

Howe, J. (2006). The rise of crowdsourcing. Wired magazine, 14(6), 1-4.

Hughes Thomas, P. (1989). American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm.

Hull, C. E., Caisy Hung, Y. T., Hair, N., Perotti, V., & DeMartino, R. (2007). Taking advantage of digital opportunities: a typology of digital entrepreneurship. International Journal of

Networking and Virtual Organisations, 4(3), 290-303.

Jiang, Y., & Tornikoski, E. T. (2019). Perceived uncertainty and behavioral logic: Temporality and unanticipated consequences in the new venture creation process. Journal of Business

Venturing, 34(1), 23-40.

Kenney, M., & Zysman, J. (2016). The rise of the platform economy. Issues in science and

Kirzner, I. M. (1979). Perception, opportunity, and profit: Studies in the theory of

entrepreneurship (pp. 142-143). Chicago: University of chicago press.

McKelvie, A., Haynie, J. M., & Gustavsson, V. (2011). Unpacking the uncertainty construct: Implications for entrepreneurial action. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(3), 273-292. Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 1029-1055.

Nambisan, S., & Baron, R. A. (2019). On the Costs of Digital Entrepreneurship: Role Conflict, Stress, and Venture Performance in Digital Platform-based Ecosystems.

Oliveira, P., & von Hippel, E. (2011). Users as service innovators: The case of banking services. Research policy, 40(6), 806-818.

Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2002). The co-creation connection. Strategy and business, 50-61.

Reymen, I. M., Andries, P., Berends, H., Mauer, R., Stephan, U., & Van Burg, E. (2015). Understanding dynamics of strategic decision making in venture creation: a process study of effectuation and causation. Strategic entrepreneurship journal, 9(4), 351-379.

Roberts, R. M. (1989). Serendipity: Accidental discoveries in science. Serendipity: Accidental

Discoveries in Science, by Royston M. Roberts, pp. 288. ISBN 0-471-60203-5. Wiley-VCH, June 1989., 288.

Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of management Review, 26(2), 243-263. Sarasvathy, S. D. (2009). Effectuation: Elements of entrepreneurial expertise. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Sawhney, M., & Prandelli, E. (2000). Communities of creation: managing distributed innovation in turbulent markets. California management review, 42(4), 24-54.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1950). Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. New York. Harpers and

Brothers Publishers, 344.

Shah, S. K. (2005). Open beyond software. Open sources, 2, 339-360.

Shah, S. K., & Mody, C. C. (2014). 9 Creating a Context for Entrepreneurship: Examining How Users’ Technological and Organizational Innovations Set. Governing knowledge

commons, 313.

Shah, S., & Torrance, A. (2013). Reconceptualizing the PHOSITA: Reexamining

Nonobviousness in light of recent developments in innovation research. Working paper,

Shah, S. K., & Tripsas, M. (2007). The accidental entrepreneur: The emergent and collective process of user entrepreneurship. Strategic entrepreneurship journal, 1(1‐2), 123-140.

Shah, S. K., & Tripsas, M. (2012). When Do User Innovators Start Firms? A Theory of User Entrepreneurship, Revolutionizing Innovation: Users, Communities and Open Innovation. Shane, S. (2000). Prior knowledge and the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities. Organization science, 11(4), 448-469.

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Academy of management review, 25(1), 217-226.

S Smith, S. W., & Shah, S. K. (2013). Do innovative users generate more useful insights? An analysis of corporate venture capital investments in the medical device industry. Strategic

Entrepreneurship Journal, 7(2), 151-167.

Suddaby, R., Bruton, G. D., & Si, S. X. (2015). Entrepreneurship through a qualitative lens: Insights on the construction and/or discovery of entrepreneurial opportunity. Journal of

Business venturing, 30(1), 1-10.

Tapscott, D. (1996). The digital economy: Promise and peril in the age of networked

intelligence (Vol. 1). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Tripsas, M. (2008). Customer preference discontinuities: A trigger for radical technological change. Managerial and decision economics, 29(2‐3), 79-97.

Tyre, M. J., & Von Hippel, E. (1997). The situated nature of adaptive learning in organizations. Organization science, 8(1), 71-83.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Gross Domestic Product by Industry: First Quarter 2019”, News Release (July 19, 2019), https://www.bea.gov/news/2019/gross-domestic-product-industry-first-quarter-2019

Von Hippel, E. (1976). The dominant role of users in the scientific instrument innovation process. Research policy, 5(3), 212-239.

Von Hippel, E. (1978). Successful Industrial Products from Customer Ideas: Presentation of a new customer-active paradigm with evidence and implications. Journal of marketing, 42(1), 39-49.

Von Hippel, E. (1986). Lead users: a source of novel product concepts. Management

science, 32(7), 791-805.

Von Hippel, E. (1994). “Sticky information” and the locus of problem solving: implications for innovation. Management science, 40(4), 429-439.

Von Hippel, E. (2001). Learning from open-source software. MIT Sloan management

review, 42(4), 82-86.

Von Hippel, E. (2005). Democratizing innovation: The evolving phenomenon of user innovation. Journal für Betriebswirtschaft, 55(1), 63-78.

Von Hippel, E., Thomke, S., & Sonnack, M. (1999). Creating breakthroughs at 3M. Harvard

business review, 77, 47-57.

Wootton, D. (2015). The invention of science: a new history of the scientific revolution. Penguin UK.

Chapter 1: Opportunity identification for entrepreneurs

with different sources of knowledge

Abstract

The entrepreneurship literature has vastly focused on the antecedents and drivers toward recognizing opportunities for the individuals. There are also ongoing studies regarding the sources of knowledge for venture creation, and scholars put these sources into three categories of entrepreneurship namely "user entrepreneurship", "academic entrepreneurship", and "employee entrepreneurship". However, there is no study aiming to answer how these entrepreneurship types identify opportunities based on their distinct characters. Theories of opportunity identification are codified into two schools of thought resulting in two different principles and frameworks. The opportunity creation theory refers to the subjective nature of opportunities while the opportunity discovery theory focuses on the objectivity of the opportunities. Our theoretical study collects literature on these separate phenomena. It encompasses the theories with the different types of entrepreneurship based on their knowledge sources and provides propositions regarding this scholarship.

Keywords: Opportunity Identification, Opportunity Creation, Opportunity Discovery, User Entrepreneurship, Academic Entrepreneurship, Employee Entrepreneurship, Sources of Knowledge

Note: This paper has been presented at DRUID Ph.D. Academy Conference which held in

Aalborg in January 2019. I would like to thank the panel committee reviewers for their feedback.

It has also been presented as a poster at IRAMOT Conference held in Tehran in December 2019.

1.1. Introduction

Innovation used to be known as the principle and the driver of wealth creation and economic growth for individuals, companies, and countries. Schumpeter (1942) believed that the disruptive transformation of technologies/markets leads to a process of creative destruction that put the economy into a recession and will recover it by itself. This disruption happens due to information asymmetries, technology improvement and different needs existed in the market. In other words, agents with different knowledge and information can provide something valuable to themselves or the public by integrating their knowledge into practice and create something novel (Aghion & Howitt, 1990). However, the process of creation from scratch requires creativity and innovativeness of the individuals in addition to their knowledge and their willingness (Goldsmith & Hofacker, 1991).

On the one side, innovation can take place when an individual is seeking to satisfy needs or make pecuniary benefits from the invention by creating a business model and consequently by creating a firm (Shah & Tripsas, 2007; von Hippel, 2005). On the other hand, incumbent companies need to keep up the pace of knowledge and technological dissemination with the market, otherwise, they might not survive. This is the basic reason for the companies that are looking for new solutions (Teece, 2010). They try to innovate by finding solutions either internally (e.g. doing R&D activities) or externally (e.g. acquiring knowledge from universities and research institutes, crowdsourcing). Two approaches appear for the innovation strategies of the firms: centralized research and development activities (i.e. closed innovation paradigm), and open innovation (including both user and crowd innovation, and collaboration with other entities such as universities and other firms).

Extant literature has focused on diverse sources of knowledge as potential holders of solutions for latent needs. Entrepreneurs exploit knowledge from different sources and may deliberately or spontaneously combine them to offer new solutions to the market. Academia, employment, and usage knowledge are the most common sources of knowledge that have been employed by the entrepreneurs and have been mentioned by previous scholars. Each entrepreneur within the mentioned types differ from each other and has idiosyncratic characteristics. They have acquired new knowledge from different sources and carry a different path toward entrepreneurship (Agarwal & Shah, 2014). The literature on entrepreneurship has explained the steps entrepreneurs pass to deliver the value to the market, but to our knowledge, no study

has shed light on the opportunity identification process between these types (Ardichvili et al., 2003; Bessant & Tidd, 2007). Here in this paper, we aim to address the very basic phenomenon of opportunity identification and clarify the differences between these diverse entrepreneurial origins.

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Opportunity Identification

As yet, there is still a big debate if entrepreneurs are proactive for seeking and searching an opportunity to identify or they recognize and face the opportunity without actively making endeavors for it. Different schools of thought believe that different paths to creating an opportunity exist. While Alvarez and Barney believe that the discovery theory and creation theory are incommensurable and can’t co-exist at the same time, Garud and Giuliani together with Sarasvathy have affirmed that these two concepts are contingencies and one of these two theories can prevail and dominate against the other at the same time and they are not irreconcilable (Alvarez & Barney, 2005, 2007; Garud & Giuliani, 2013; Sarasvathy, 2001; Suddaby et al., 2014). On the other hand, the ambiguity of the opportunity itself as an abstract concept which some believe it doesn’t exist ex-ante and decomposable merely ex-post, resulted in the nascent ideologies to shift the attention from the opportunity identification to the opportunity exploitation.

The very recent efforts were the piece written by Foss and Klein who proposed the BAR framework that intends to concentrate on the Beliefs, Actions, and Results of the entrepreneurship process through the judgment-based view (Foss & Klein, 2018; Kitching & Rouse, 2017). Nevertheless, for the sake of our research and due to the underlying concept of our research question we need to investigate how the business ideas appear in the individuals’ minds. In this paper, we deliberately do not aim to find how the ideas evolve and get exploited but to capture the locus that the ideas belong to by using different entrepreneurship types.

1.2.1.1. Opportunity Creation Theory

In his article, Shane (2000) showed that entrepreneurs in separate fields built their companies thanks to the advancement of technology, in particular, MIT’s 3DP invention, without

searching for an opportunity. All founders of those eight companies explained that they were not seeking a solution but instead they recognized that by employing the 3DP technology in their business, they can provide something more valuable to the market. This finding is consistent with the Austrian economics framework, discussing that the opportunities cannot be searched as in their essence, opportunities are non-existent abstracts until they get founded (Kaish & Gilad, 1991).

Here, opportunities are considered as subjective concepts that will be explored thanks to a comprehensive plan of action by entrepreneurs (Sarasvathy, 2001). Therefore, opportunities are considered to be non-existent until when they are found and created by entrepreneurs. In other words, individuals first identify a particular problem and then they aim and plan for how to solve it. Then opportunity could be identified. This implies that the opportunity’s existence is dependent on the individuals to create them. The scholars who believe in this model of opportunity identification, use creation theory (of opportunity) for describing the phenomenon. In the creation theory, people look for solutions and they search through all available channels until when they prevail. Despite the consensus about the importance of search in this model of opportunity identification, Alvarez and Barney believed that due to the non-existence essence of opportunity, the term ‘search’ has no meaning here (Alvarez & Barney, 2007). However, the negligence of their statement is because they haven’t separated the search process from searching for an enabler to reach the solution or searching for the solution itself. In other words, different tools and mechanisms can help individuals to answer a problem. The enablers might exist but they are needed to be taken into account and be observed. In fact, the ‘search’ term is not a distinction between creation and discovery theory when looking for an enabler since entrepreneurs, in general, tend to scan and search their surroundings.

Besides, in this model of opportunity identification, the entrepreneurs know what they want to achieve and plan based on their expected outcome (Sarasvathy, 2001). This conveys that they anticipate the consequences of the potential solution. Then depending on each person's perception of opportunity cost, she might initiate to deliver the solution or to discard it. In case she decides to deliver the value to the market, it might appear as a new product or a new service or a new technique of production or a new organization model. As a result, all the activities that an entrepreneur does is planned to solve a problem which ultimately might help her to commercialize and subsequently create a firm. The actions and reactions that an entrepreneur takes are formed endogenously and are not anymore primarily shaped due to the alertness of entrepreneurs to the market's turbulence (Sarasvathy, 2001). This type of opportunity

identification bespeaks of the fact that the opportunities here are more prone to be market breakthrough as they are outcomes of an endogenous, unobserved and latent phenomenon.

1.2.1.2. Opportunity Discovery Theory

In this framework, opportunities are objective concepts that could be found due to the turbulence of technology and/or the market. Therefore, getting exposed or being associated with an industry or market or entertainment will smooth the process of opportunity discovery. Thus, the obvious feature of these entrepreneurs is having great alertness to the surroundings. Kirznerian followers believe that entrepreneurs are significantly different from non-entrepreneurs in terms of capturing opportunities (Alvarez & Barney, 2007; De Jong & Marsili, 2011; Kirzner, 1973; Shane 2003). This identification process of opportunity is entitled as discovery theory (of opportunity).

The discovery theory believes that opportunities exist independently of individuals. This connotes the objective essence of opportunity. In other words, the opportunities will be found sooner or later no matter who will find it. They exist and become available thanks to the exogenous turbulence and will be recognized by entrepreneurs who differ with non-entrepreneurs in some important aspects (Alvarez & Barney, 2007; Shane, 2003).

In their piece, Alvarez and Barney used Mount Everest as the symbol and metaphor for opportunity explaining their assumptions that opportunities don’t get created but they exist as it is (Alvarez & Barney, 2007). However, the real value is not Mount Everest itself, but the way how to find where the mountain is located and how to get there. Without knowing how to make value from oil, this substance is useless until someone introduces a usage from it. It is like knowing the fact of gold existence but not finding the potential places to dig. In another explanation, Mount Everest as an opportunity doesn't connote how its existence brings pecuniary benefits to its territory. To put it differently, believing that opportunities are existent objects which bring economic benefits per se without the intervention of individuals doesn't relate to the whole process of commercialization of an entrepreneurial opportunity.

1.2.2. Entrepreneurship and Sources of Knowledge

Referring to the definition of entrepreneurship, different individuals may find opportunities to be exploited based on their prior knowledge. These people take the required knowledge from their employment, academic research and/or usage activities (Stevenson, 1983).

Each step of entrepreneurship journey from its core idea management to decision making to human resource practices to the strategy and finance requires sophisticated knowledge that facilitates the business to sustain. The knowledge settings that will emerge in each step could be solely coming from one source or could be accumulated from different sources after the entrepreneur(s) building the management team. However, the first idea which in turn becomes the value proposition of the opportunity conventionally receives more attention than the subsequent steps.

Depending on the cognitive attributes of the individuals and their perception of risk preferences, some ideas ultimately become opportunities to be exploited. The entrepreneurs who exploit an opportunity do not necessarily decide upon their current resources. The capabilities and competencies which are used by the entrepreneurs can come from their previous/current education, employment, and leisure/recreational activities which finally leads to the usage of that particular product/service. Here we describe the path toward entrepreneurship based on these three distinctive knowledge origins. The entrepreneurship literature has labeled them as user entrepreneurship, employee entrepreneurship, and academic entrepreneurship (Agarwal & Shah, 2014).

1.2.2.1. Employee Entrepreneurship

The knowledge-based view of the firm explains that the tacit knowledge is acquired from different individuals, and varied knowledge settings would be suitable for the firms producing competitive goods and services (Felin & Hesterly, 2007; Grant, 1996). The disseminated knowledge in the working environment varies a wide range of subjects. Both explicit and tacit knowledge appear in technological, operational, marketing, and organizational dimensions (Agarwal & Shah, 2014).

Individuals with different knowledge basis serving a firm might encounter an opportunity due to their dissatisfaction with performing a task. They may even find another interesting alternative for how to serve the market (Hellmann, 2007). Their alternative could be helpful

for the firm to increase its efficiency or to provide an innovation that is of more value than the current product/service. As Hellmann (2007) mentioned, four possibilities emerge here (focused equilibrium, stubborn equilibrium, intrapreneurial equilibrium, and entrepreneurial equilibrium) as a result of a dialogue between employee and employer.

Parhankangas and Arenius (2003) defined this phenomenon as “new venture creation based on knowledge which is associated with the parent firm activities”.

Previous literature has made a clear distinction for the spinoffs appearing from a commercial context by introducing typologies for this phenomenon (Fryges & Wright, 2014). Although corporate spinoffs are born thanks to the parent firm’s IP rights, employee spinoffs are created with indirect use of parent firm’s intellectual assets such as tacit knowledge of a group of employee(s). Nonetheless, the common point for the diverse typologies of this phenomenon is that they all are formed on a know-how transfer from a parent firm to a new one (Fryges & Wright, 2014). Horizontal spinoff refers to the firms that are in the same industry to the parent firm and vertical spinoff are founded in different settings than the parent firm. While the latter contributes to the market-breakthroughs and the creation of new industries, the former contributes to the progress and development of the existing industry (Muendler et al., 2012). This type of spinoff (employee spinoff) emerges when the newborn knowledge (or the new recognized opportunity) doesn’t comply with the core activity of the parent firm, hence the spillovers will be used outside the parent-firm boundaries (Fryges & Wright, 2014). It is perceived that the current capabilities and complementary assets of the parent firm are not sufficient for tackling the first steps of new knowledge development.

As visualized, the push from an incumbent to create a new division or a new subsidiary based on an internal innovation follows a different path compared to the employee's ideas for promoting innovation and creating a firm. Therefore, we hypothesize that the dynamics of opportunity identification and entry, seem to differ among each newly created venture and spinoff typologies.

In this article, we don't constrain ourselves selecting from horizontal or vertical spinoffs or other classifications of (employee) spinoffs. To avoid the misinterpretation for the term "spinoff" as a sold division of a parent firm, and for the aim of this paper for making a distinction between the sources of knowledge for entrepreneurship, we use the term of “employee entrepreneurship” for this category (Agarwal & Shah, 2014).

Apart from the cognitive features of entrepreneurs, employee entrepreneurs seem to have better access to complementary assets (Agarwal & Shah, 2014). Studies have shown that this type of

knowledge, social networks, and venture capitals (Agarwal & Shah, 2014; Stuart & Sorenson, 2003). As this type of entrepreneurs has more knowledge about the organizational and technical aspects, they mostly seem to be creating ventures when they encounter an opportunity from a tacit knowledge they gained before. On the other hand, they have shown eagerly to form a firm when they possess an intellectual property right in the form of a patent (Agarwal & Shah, 2014; Klepper & Sleeper, 2005). Thus, the barriers to entry seem to be less complicated for employee entrepreneurs.

Again, these individuals are exposed to the industry and hold higher chances to know the behavior of consumers/suppliers and the market in general. Ex-ante, they seem to have systematic confidence which is shaped and constructed thanks to their previous employment and helps them to look around for opportunities. These result in higher sensitivity to recognize the shocks and turbulence of the surroundings. Therefore we propose that:

Proposition 1. Employee entrepreneurs tend to discover opportunities more than creating

them

1.2.2.2. Academic Entrepreneurship

Academic entrepreneurship refers to the creation of ventures by a student, faculty or a staff of a university or a public-funded (no profit organizations) research institute based on a breakthrough emerged from an academic research activity (Di Gregorio & Shane, 2003; Shane, 2004).

The knowledge (coming from non-profit research) and the founders of the newly created firm (who are affiliated with the research institute) are considered as the criteria for academic entrepreneurship. Some scholars have had a different approach and definition of this phenomenon. Some believe that the surrogate entrepreneurs who do not have any affiliation with the public-funded research institute but exploit knowledge which was developed there, are included in the university spinoff definition (Nicolaou & Birley, 2003). However, others believe that the existence of both “developed knowledge/technology” and “founders from a research institute” is the necessary condition for university spinoffs (McQueen & Wallmark, 1982; Smilor et al., 1990).

These two terms result in the classifications of university spinoffs into orthodox (existence of knowledge and academic founders), hybrid (existence of knowledge and academic founders