“Legal highs”: safe and legal “heavens”? A study on the diffusion,

knowledge and risk awareness of novel psychoactive drugs

among students in the UK

“Legal highs”: paradisi sicuri e legali? Uno studio sulla diffusione, conoscenza e

consapevolezza del rischio delle nuove droghe psicoattive tra gli studenti del Regno Unito

ORNELLA CORAZZA, PIERLUIGI SIMONATO, JOHN CORKERY, GIUSEPPINA TRINCAS, FABRIZIO SCHIFANOE-mail: [email protected]

University of Hertfordshire, School of Pharmacy, College Lane Campus, Hatfield, United Kingdom

SUMMARY. Background. The recent emergence of new recreational drugs, combined with the ability of the Internet to disseminate

infor-mation quickly, have raised a number of concerns in the fields of drug policy, substance use research, and public health. Methods. A semi-structured questionnaire was advertised on The Study Room’s website from November to December 2010 to explore the awareness, the use and the perception of risks of “legal highs” among student population in the UK. Results. One-third (31.40%) of the 446 participants re-ported use of these kinds of drugs. Respondents were more likely to have taken were: mephedrone (41.4%), Salvia divinorum (20%), “Spice drugs” (10.7%), methylone (1.4%), naphyrone (NRG) (2.1%) and benzylpiperazine (BZP) (2.1%), while 15.7% did not know what com-pounds they had ever consumed. The large majority (78.9%) considered these as legal substances, while 74.2% did not consider these safer than illicit drugs. Half (50.8%) of the respondents were aware of the presence of illegal agents in the products they had consumed.

Conclu-sions. The study contributes to an initial assessment of the use and the risks awareness of novel psychoactive compounds among students

in the UK. Further research is required, especially in terms of personality and lifestyle attitudes to better profile these new forms of abuse also in non-recreational settings.

KEY WORDS: legal highs, mephedrone, Salvia divinorum, spice drugs, novel compounds, students.

RIASSUNTO. Introduzione. La recente comparsa delle nuove sostanze ricreazionali, combinata alla possibilità offerta da Internet di

diffon-dere le informazioni velocemente, ha sollevato numerose nuove preoccupazioni nel campo legislativo, nel campo della ricerca sulle nuove so-stanze e per quanto riguarda la salute pubblica. Metodi. È stato utilizzato un questionario semistrutturato pubblicizzato sul sito di Study Ro-om da novembre a dicembre 2010 per esplorare la consapevolezza, l’uso e la percezione di rischio delle “legal highs” tra la popolazione stu-dentesca nel Regno Unito. Risultati. Un terzo (31,40%) dei 446 partecipanti ha riferito l’uso di queste sostanze. Gli intervistati hanno riferi-to soprattutriferi-to l’uso di: mefedrone (41,4%), Salvia divinorum (20%), “spice drugs” (10,7%), metilone (1,4%), nafirone (NRG) (2,1%) e ben-zilpiperazina (BZP) (2,1%), mentre il 15,7% non sapeva che tipo di composto avesse assunto. La maggioranza (78,9%) considerava queste so-stanze “legali”, mentre il 74,2% non le considerava più sicure di composti illegali. Metà del campione (50,8%) era consapevole della presenza di componenti illegali nei prodotti consumati. Conclusioni. Lo studio contribuisce al tentativo di stimare l’uso e la consapevolezza del rischio in merito alle nuove sostanze psicoattive tra gli studenti del Regno Unito. Si ritengono necessari ulteriori studi, soprattutto in termini di per-sonalità e stili di vita, al fine di inquadrare meglio queste nuove forme di abuso, anche in setting non propriamente ricreazionali.

PAROLE CHIAVE: legal highs, mephedrone, Salvia divinorum, spice drugs, nuovi composti, studenti.

INTRODUCTION

An increasing number of unregulated websites are dedi-cated to the dissemination of new psychoactive substances, which include plant-based compounds, synthetic derivatives of well-established drugs, as well as “designer medicines”1-3.

For instance, during 2010, 41 new psychoactive substances were officially notified for the first time in the European Union4. These are not controlled by the United Nations

Sin-gle Convention on Narcotic Drugs (1961) or the United Na-tions Convention on Psychotropic Substances (1971), but which may pose a health threat comparable to that posed by substances listed in the above conventions5. More

specifical-ly, these are: a) not approved for human consumption and might well have unknown effects and adverse reactions on users6-9; b) often sold as something else, like “mystical

in-censes”6, “plant chemicals”10and “bath salts”11; c) unknown

scientific literature; e) advertised as “legal’ and ‘safe’ prod-ucts and thus increasingly accepted as part of a lifestyle rather than being considered substances of misuse especially among adolescents13. In this respect, we aimed here to assess

the use of these new psychoactive compounds among a sam-ple of students in the UK.

RESULTS

Demographic information

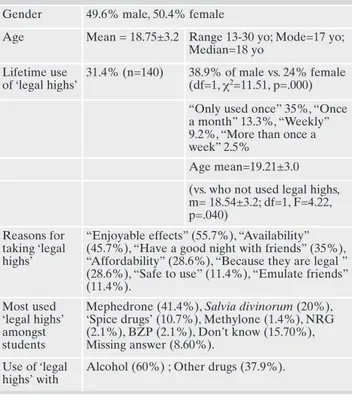

Half (49.6%) were male and 50.4% were female. The mean age of the sample was 18.75±3.2 years, with a range of 13 to 30, and a mode of 17 years (Table 1). No data about eth-nicity and disability were collected. All the respondents were based in schools and universities across the UK.

Use of “legal highs”: consumption, frequency, motivations, substances and combinations Consumption

About one-third (31.4% of our sample) (Table 1) con-firmed having used “legal highs” at least once in their life.

Male respondents were significantly more likely to have tak-en these than female (38.9% compared to 24%). The mean age of those who consumed these substances was 19.21±3 years with a statistical significance (F=4.22 p=.040) towards those who did not used them (m=18.5±3.2), as shown in Table 1.

Frequency

One third (35%) of those who consumed these substances admitted to have “only used them once”, 13.3% “once a month”, 9.2% “weekly” and 2.5% “more than once a week” (Table 1).

Motivations

Those who tried ‘legal highs’ were most likely to do so be-cause of their: “enjoyable effects” (55.7%), “easy availabili-ty” (45.7%), “enhanced sociabiliavailabili-ty” (35%),“affordabiliavailabili-ty” (28.6%), “legality” (28.6%), “safety” (11.4%) and finally in order to “emulate friends” (11.4%), as shown in Table 1. Use of specific drugs

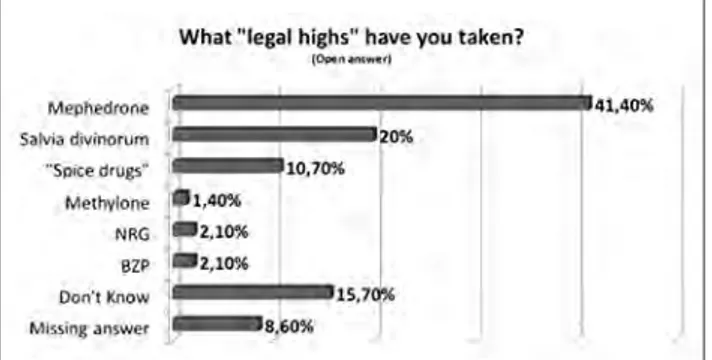

Among those who have tried “legal highs”, the drugs which respondents were more likely to have taken were: mephedrone (41.4%), Salvia divinorum (20%), “spice drugs” (10.7%), methylone (1.4%), naphyrone (NRG) (2.1%) and benzylpiperazine (BZP) (2.1%), while 15.7% did not know what compound they had ingested (Table 1).

METHODS

Between 9thNovember to 6thDecember 2010, 446 students in the UK aged between 13 and 30 completed an online survey, which explored their experience and perception of risks associat-ed with novel psychoactive compounds. This was advertisassociat-ed on The Student Room’s website14, the major advertising platform for higher education in the UK. Responses were kept anonymous.

The survey questions were designed by The Student Room’s staff, which has expertise in providing consultation and advice on subjects ranging from education to health related issues to young people aged 13-26 years. The Student Room is the world’s largest student web community, with 30 million page views and 4.5 mil-lion unique users each month. This was considered a credible ve-hicle to use for opportunistic research that provided inexpensive, rapid and targeted access to a relatively large student sample in a short period of time.

Chi-square analysis was used to compare who had a lifetime use of these drugs with others by gender, awareness of controlled compounds, while means and ANOVA tests were also used to evaluate age in the sample. Data was processed with SPSS for Windows™ version 14.

The study was carried out in accordance with The Student Room’s regulations and ethical code of practice. The study was carried out in accordance with The Student Room’s regulations and ethical code of practice and reviewed by the ReDNet Ethics Advisory Board at University of Hertfordshire in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH)/WHO Good Clinical Practice standards and with the recommendation guiding physicians in biomedical research of the Declaration of Helsinki on human subjects testing and the Convention of the Council of Europe on Human Rights and Biomedicine, Oviedo (1997).

Table 1. Basic, demographic data and use of ‘legal highs’ among the 446 participants (n=446)

Gender 49.6% male, 50.4% female

Age Mean = 18.75±3.2 Range 13-30 yo; Mode=17 yo; Median=18 yo

Lifetime use of ‘legal highs’

31.4% (n=140) 38.9% of male vs. 24% female (df=1, χ2=11.51, p=.000) “Only used once” 35%, “Once a month” 13.3%, “Weekly” 9.2%, “More than once a week” 2.5%

Age mean=19.21±3.0 (vs. who not used legal highs, m= 18.54±3.2; df=1, F=4.22, p=.040)

Reasons for taking ‘legal highs’

“Enjoyable effects” (55.7%), “Availability” (45.7%), “Have a good night with friends” (35%), “Affordability” (28.6%), “Because they are legal ” (28.6%), “Safe to use” (11.4%), “Emulate friends” (11.4%).

Most used ‘legal highs’ amongst students

Mephedrone (41.4%), Salvia divinorum (20%), ‘Spice drugs’ (10.7%), Methylone (1.4%), NRG (2.1%), BZP (2.1%), Don’t know (15.70%), Missing answer (8.60%).

Use of ‘legal highs’ with

Combination with other drugs

“Legal highs” were often mixed with alcohol (60%) and “other drugs” (37.9%), as shown in Table 1.

“Legal highs”: knowledge, risk awareness and general attitudes

Knowledge

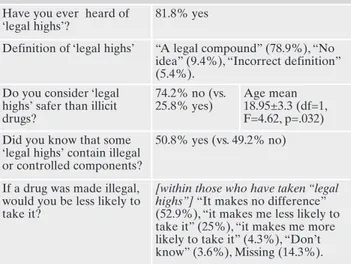

Four-fifths (81.8%) of the student sample had heard of a substance “referred to as a ‘legal high’” (Table 2), while 352 students (78.9%) defined them as a “legal compound”, un-derlining their legal status. One-tenth (9.4%) had no idea of what a ‘legal high’ was and 5.4% gave a completely incorrect definition of these types of substance (“cigarettes”, “cigars”, “weed”, “medically prescribed marijuana”, etc.).

Risk awareness

A high percentage (74.2%) did not consider ‘legal highs’ safer than illicit drugs; this group in our sample seemed to be significantly older (mean=18.95±3.3, F=4.69 p=.032) than those who answered the opposite to this item (mean=18.20±2.8). Half of the sample (50.8%) knew that some legal highs contain illegal or other components (Table 2).

General attitudes towards drugs use and regulation

Respondents were split in terms of their attitudes towards drugs (Table 2). While just more than half of those who had taken recreational drugs (52.9%) claimed that their legal sta-tus “made no difference” to their attitudes towards them, a smaller portion (25%) of respondents agreed that they are less likely to consume a substance when it is illegal, with 4.3% who, on the contrary, are more likely to take it. Only a few (3.6%) did not have an opinion (“Don’t know”).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this study constitutes one of the first attempts aimed to assess the use and the awareness of new psychoactive compounds, conducted among students in the UK. The mean age of the group was 18.75 years with the most represented age being 17 years old. From a psy-chopathological point of view, this age is generally consid-ered a high risk group for the onsets of several psychiatric disorders, which could be triggered by substances of abuse in predisposed subjects10,15-19.

Because of the method of recruitment our sample had a good level of education and the gender split was very even (male 49.6%; female 50.4%).

Interestingly, 140 subjects (31.4% of the total sample, Fig-ure 1) had tried a wide range of new psychoactive com-pounds with a higher prevalence amongst male students (38.9% vs. 24%) (Table 1). Such findings have also been sup-ported by a previous survey carried out among young people in UK, where male respondents were significantly more like-ly than female users to have taken recreational drugs (72% compared with 56%).

Those who tried these products were also significantly older than students who did not use them, with a mean age of 19.21 years. The majority of respondents used these drugs only once (35%), while 13.3% used them once a month and 9.2% reported more regular (weekly) consumptions.

The study also evaluated the different reasons behind the use of these drugs (Figure 2). The respondent sample em-phasised first of all the “enjoyable effects” (55.7%) and the “easy availability” (45.70%) of these substances, especially over the Internet (1,20). Intriguingly, few subjects chose “le-gal highs” because of their presumed safety (11.4%), and they considered the “low price” (28.6%) and their “legality” (28.6%) more appealing.

The drug which respondents were most likely to use was mephedrone (41.4%), as shown in Figure 3. These data con-firmed the popularity of mephedrone8,10,21and other

stimu-lants drugs in the UK, which has doubled over the period 2005-84.

Other drugs of preference were Salvia divinorum (20%), a well-known compound22,23, which can induce derealisa-Table 2. Awareness, knowledge and general attitudes towards

“legal highs” (n=446)

Have you ever heard of ‘legal highs’?

81.8% yes

Definition of ‘legal highs’ “A legal compound” (78.9%), “No idea” (9.4%), “Incorrect definition” (5.4%).

Do you consider ‘legal highs’ safer than illicit drugs? 74.2% no (vs. 25.8% yes) Age mean 18.95±3.3 (df=1, F=4.62, p=.032) Did you know that some

‘legal highs’ contain illegal or controlled components?

50.8% yes (vs. 49.2% no)

If a drug was made illegal, would you be less likely to take it?

[within those who have taken “legal highs”] “It makes no difference”

(52.9%), “it makes me less likely to take it” (25%), “it makes me more likely to take it” (4.3%), “Don’t know” (3.6%), Missing (14.3%).

tion24and lead to a number of medical and

psychopatholog-ical risks19; ‘Spice drugs’ (10.7%), a brand name for a ‘herbal

smoking blend’, which was found to contain synthetic cannabinoids9,25,26; and other novel compounds such

methy-lone, NRG, BZP, which have been briefly described in the scientific literature27,28.

It is interesting to observe that 15.7% of respondents did not know what drug they had taken. It could be speculated that these products: a) were unknown to users because are of-ten sold as “bath salts”, “incenses”, “fertilisers”, or with nick-names (e.g. “meow meow”, “spice”, etc.) and this might gener-ate confusion about their ‘real’ content3,11,20; b) were

consid-ered to be of a different/non recreational nature such as cog-nitive enhancers, sleeping pills, drugs to reduce body weight and/or enhance sexual performances, etc. which are also wide-ly sold on the internet by illegal on-line pharmacies10 and

might be a fertile topic of study for future investigation. The consumption of these novel compounds in the major-ity of the cases (60%) was combined with alcohol (60%) and “other drugs” (37.9%). In these cases, higher health risks might also be expected10,29,30.

“Legal highs2 a misleading term?

Although a high number of the young respondents were aware of the existence of ‘legal highs’ (81.8%), the large

majority (78.9%) (Figure 4) defined them in an open an-swer as “legal compounds” (e.g. “legal drugs”, “not illegal drugs”, “legal substances”, “legal recreational drugs”) al-though these might not always be case. This clearly shows how the “legal highs” term, largely used by the media, can be easily misconceived and understood as something com-pletely legal, especially by young people31. In addition, the

term is hard to translate into different languages such as German, Polish and Italian12, mainly because of its

‘posi-tive’ connotation. Terms such as “designer drugs”, initially coined by Gary Henderson at the University of California in the mid 1980s32, “designer medicines”33for what are

sim-ply new psychoactive compounds might be more appropri-ate for educational use.

In addition (Figure 5), half of respondents (52.9%) re-ported that “it made no difference” to their choice whether the product was legal or not. They would have taken it any-way.

Risk awareness

According to the large and older (mean=18.95±3.3 years;) majority of the sample (74.2%), legal highs’ were not consid-ered safer than other common illicit drugs. This could indi-cate a good level of awareness of the risks associated with their consumption. It is worth mentioning here that in the Figure 2. Reasons for taking ‘legal highs’.

Figure 4. What do you think a ‘legal high’ is?

Figure 5. If a drug was made illegal would you be less likely to take it? Figure 3. What ‘legal highs’ have you taken?

UK extensive media attention is given to various fatalities in the country34-36. However, even if these data seem to be

en-couraging, only half of the sample knew about the presence of contaminants in these substances (50.8%).

LIMITATIONS

Results described in this study were elicited from a self-selected, non randomized, limited online sample and find-ings identified may not allow their generalizability. Howev-er, present approach may have increased a better under-standing of the abuse of novel psychoactive compounds among students population the UK. All subjects recruited for this survey were visitors The Student Room’s website. This was considered a credible vehicle for the study, which allowed a rapid, targeted and inexpensive collection of da-ta. Further biases may have arisen in relation to the lack of detailed, closed-ended questions on the nature of the abuse, which might have caused inappropriate answers and un-wanted errors. On the other hand, open-ended questions encourage the respondents to come up with their own an-swers and thus could be considered better suited for this novel field of investigation. Finally, more research work should be carried out in larger sample of students, and re-sults could be systematically compared with those emerging from similar studies on novel psychoactive compounds in recreational settings (“club scene”).

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, this study highlights the need to provide more reliable information on novel psychoactive compounds to students and young people in general. The modalities are also equally important12,37,38. For instance, the involvement of

young people in the design of the prevention messages as well as the use of interactive technologies such as social net-working for their dissemination might be considered with success32. The popular myth of ‘legal highs’ as enjoyable, safe

and legal ‘heavens’, needs to demythised very urgently with scientifically-based information and synergetic/synchronised international action.

REFERENCES

Schifano F, Deluca P, Baldacchino A, et al. Drugs on the web; the 1.

Psychonaut 2002 EU Project. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2006; 30: 640-6.

Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Prescription drugs pur-2.

chased through the internet: who are the end users? Drug Alco-hol Depend 2010; 110: 21-9.

Walsh C. Drugs, the Internet and Change. J Psychoact Drugs 3.

2011; 43: 55-63.

EMCDDA report 2010: The state of the drugs problem in Eu-4.

rope, European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addic-tion, 2010.

Sedefov R, Gallegos A. Risks assessments. Report on the risk as-5.

sessment of mephedrone in the framework of the Council Deci-sion on new psychoactive substances. EMCDDA, 2011. Schifano F, Corazza O, Deluca P, et al. Psychoactive drug or mys-6.

tical incense? Overview of the online available information on Spice products. Int J Cult Ment Health 2009; 2: 137-44. Brandt SD, Sumnall HR, Measham F, Cole J. Second generation 7.

mephedrone. The confusing case of NRG-1. BMJ 2010; 341: c3564.

Maskell PD, De Paoli G, Seneviratne C, Pounder DJ. 8.

Mephedrone (4-Methylmethcathinone)-Related Deaths. J Anal Toxicol 2011; 35: 188-91.

Maxwell JC. Psychoactive substances. Some new, some old: a 9.

scan of the situation in the US. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014; 134: 71-7.

Schifano F, Albanese A, and the ReDNet Research Group. 10.

Mephedrone (4-methylmethcathinone; ‘meow meow’): chemical, pharmacological and clinical issues. Psychopharmacology 2011; 214: 593-602.

Winstock AR, Mitcheson LR, Deluca P, Davey Z, Corazza O, 11.

Schifano F. Mephedrone, new kid for the chop? Addiction 2011; 106: 154-61.

ReDNet (2011). Recreational Drugs European Network (ReD-12.

Net). Pre-survey results on the health professionals knowledge on legal highs. Unpublished work.

Corazza O, Assi S, Trincas G, et al. Novel drugs, novel solutions: 13.

exploring the potentials of web-assistance and multimedia ap-proaches for the prevention of drug abuse. Italian Journal on Ad-diction 2011; 1: 25-30.

www.thestudentroom.co.uk 14.

Crews F, He J, Hodge C. Adolescent cortical development: a crit-15.

ical period of vulnerability for addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2007; 86: 189-99.

Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, McGorry P. Mental health of young 16.

people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet 2007; 369: 1302-13.

Parolaro D, Vigano D, Realini N, Rubino T. Role of endo-17.

cannabinoids in regulating drug dependence. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2007; 3: 711-21.

Odgers CL, Caspi A, Nagin DS, et al. Is it important to prevent 18.

early exposure to drugs and alcohol among adolescents? Psychol Sci 2008; 19: 1037-44.

Breton JJ, Huynh C, Raymond S,et al. Prolonged hallucinations 19.

and dissociative self mutilation following use of Salvia divinorum in a bipolar adolescent girl. J Subst Use 2010; 15: 113-7. Schepis TS, Marlowe DB, Forman RF. The availability and por-20.

trayal of stimulants over the internet. J Adolesc Health 2008; 42: 458-65.

Carhart-Harris RL, King LA, Nutt DJ. A web-based survey on 21.

mephedrone. Drug Alcohol Depend 2011; 118: 19-22.

Appel J, Kim-Appel D. The rise of a new psychoactive agent: 22.

Salvia divinorum. Int J Ment Health 2007; 5: 248-53.

Singh S. Adolescent salvia substance abuse. Addiction 2007; 102: 23.

823-4.

González D, Riba J, Bouso JC, Gómez-Jarabo G, Barbanoj MJ. 24.

Pattern of use and subjective effects of Salvia divinorum among recreational users. Drug Alcohol Depend 2006; 85: 157-62. Atwood BK, Huffman J, Straiker A, Mackie K. JWH018, a com-25.

mon constituent of ‘Spice’ herbal blends, is a potent and effica-cious cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonist. Br J Pharmac 2010; 160: 585-93.

Schneir AB, Cullen J, Ly BT. “Spice” Girls: synthetic cannabinoid 26.

intoxication. J Emerg Med 2011; 40: 296-9.

Butler R, Sheridan J. Highs and lows: patterns of use, positive 27.

(BZP-party pills) amongst young people in New Zealand. Harm Red J 2007; 4: 18.

Brandt SD, Sumnall HR, Measham F, Cole J. Analyses of second-28.

generation ‘legal highs’ in the UK: Initial findings. Drug Test Anal 2010; 2: 377-82.

Dickson AJ, Vorce SP, Levine B, Past MR. Multiple-drug toxicity 29.

caused by the coadministration of 4-methylmethcathinone (mephedrone) and heroin. J Anal Toxicol 2010; 34: 162-8. McGaw C, Kankam O. The co-ingestion of alcohol and 30.

mephedrone: an emerging cause of acute medical admissions in young adults and a potential cause of tachyarrhythmias. West London Med J 2010; 2: 9-13.

Ramsey J, Dargan PI, Smyllie M, et al. Buying ‘legal’ recreation-31.

al drugs does not mean that you are not breaking the law. QJM 2010; 103: 777-83.

Corazza O, Schifano F, Farre M, et al. Designer drugs on the in-32.

ternet: a phenomenon out-of-control? The emergence of hallu-cinogenic drug bromo-dragonfly. Curr Clin Pharmacol 2011; 6: 125-9.

Sedefov R. Presentation at the first international multidiscipli-33.

nary forum on new drugs. First international multidisciplinary fo-rum on new drugs. Lisbon, 2011.

Portal G. ‘Legal high’ clubbing drugs banned in UK. BBC News. 34.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/8427439.stm (accessed on 10/05/2011).

BBCNews. Party drug mephedrone ‘contributed’ to death. BBC 35.

news.http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/10479406 (accessed on 10/05/2011).

BBCNews. ‘Evil’ mephedrone warning after Rhondda teenager 36.

death. BBC News. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-12229268 (accessed on 10/05/2011).

Demetrovics Z, Mervó B, Corazza O, et al. Az elektronikus pre-37.

venció lehet ségei az új (szintetikus) drogok használatának megel zésében: a Rekreációs Drogok Európai Hálózatának (Recreational Drugs European Network) bemutatása. Addic-tologia Hungarica 2010; 9: 289-97.

Schifano F, Ricciardi A, Corazza O, Deluca P, Davey Z, Rafanel-38.

li C; Gruppo di Ricerca “Psychonaut Web mapping”. New drugs of abuse on the web: the role of the Psychonaut Web Mapping Project. Riv Psichiatr 2010; 45: 88-93.