University of “ROMA TRE”

Department of Economics

School of Economics and Quantitative Methods

PhD in “Environmental and Development Economics” XXVI Cycle

Transitions to sustainable socio-‐technical regimes in organic

agriculture

Candidate: LIVIA ORTOLANI

Supervisor: Prof.ssa Maria Fonte University of Neaples “Federico II”

Phd Programme Coordinator: Prof. Luca Salvatici University of Roma Tre Academic year 2014-‐2015

List of tables ... 4

List of figures ... 4

Summmary ... Errore. Il segnalibro non è definito. Introduction ... 6

Three approaches to sustainability of agro-‐food systems ... 7

Agricultural innovation paradigms and sustainability ... 9

Hypothesis and methodology ... 12

1 Transition theory and Network approach ... 15

1.1 Introduction ... 15

1.2 The multilevel transition theory and pathways to sustainability ... 16

1.3 The shift from niche to regime as a key for the agro-‐ecology vision ... 19

1.4 Power relations and networks to define paths from niches to regime ... 21

1.5 The network structure of agricultural innovation systems ... 23

1.6 The farm as a system and the farmer ego network ... 25

1.7 The farm autonomy as a sustainability goal at farm level ... 28

2 Social Network Analysis and ego networks ... 30

2.1 Introduction ... 30

2.2 Literature review ... 30

2.3 Key concepts of Social Network Analysis ... 32

2.4 Ego networks or personal networks ... 34

2.5 Ego-‐Network data and personal network research design (PNRD) ... 35

2.6 Directed graphs ... 37

2.7 Types of nodes in directed graphs ... 39

2.8 Centrality measurements in ego networks ... 39

3 Organic farmers between niche and regime ... 42

3.1 Introduction ... 42

3.2 The transition from niche to regime of organic agriculture ... 43

3.3 Different transition trajectories lead to the choice of organic farming ... 46

3.4 Innovative approaches to breeding in organic farming and the FP7 SOLIBAM project. ... 48

3.5 Farms and transition pathways by country ... 51

3.5.1 Italy ... 51

3.5.2 France ... 59

3.5.3 Portugal ... 67

4 Analysis of six organic farmers’ ego networks ... 75

4.1 Introduction ... 75

4.2 Participatory mapping exercise for data collection ... 75

4.3 Methodology for ego-‐network analysis ... 78

4.4 Analysis of actors in farmers’ ego networks ... 79

4.4.1 Territorial approach to sustainability (Scale) ... 82

4.4.2 Agricultural Innovation Systems (AIS) ... 83

4.4.3 Multilevel perspective to transition theory (MLP) ... 84

4.4.4 Actor network theory (Role) ... 86

4.5 Analysis of the farms organizational models through ego networks ... 88

4.6 Analysis of farmers’ knowledge networks ... 95

4.6.1 The type of actors in key position in the farmers’ knowledge networks ... 100

4.6.2 The observation of the farmers’ knowledge networks structure ... 103

4.7 Concluding remarks on network analysis ... 104

5 Three trajectories in the transition to sustainability of organic farmers ... 106

5.2 Similarities among case studies ... 106

5.2.1 Common features of farmers PT1 and FR2 ... 106

5.2.2 Common features of farmers FR1 and IT1 ... 109

5.2.3 The farmer PT2 and the farmer IT2 ... 112

5.3 The actors in the farmers’ ego network by trajectory ... 114

5.3.1 Value driven trajectory ... 114

5.3.2 Quality driven trajectory ... 116

5.3.3 Policy driven trajectory ... 118

Conclusions ... 120

References ... 124

Annex 1 – Semi structured questionnaire ... 133

Annex II -‐ List of actors and attributes ... 135

Annex 2 – Type of nodes in goods and money networks ... 143

List of tables

Table 1 -‐ Sustainability in three economic approaches. Table 2 – Main features of the six case studies

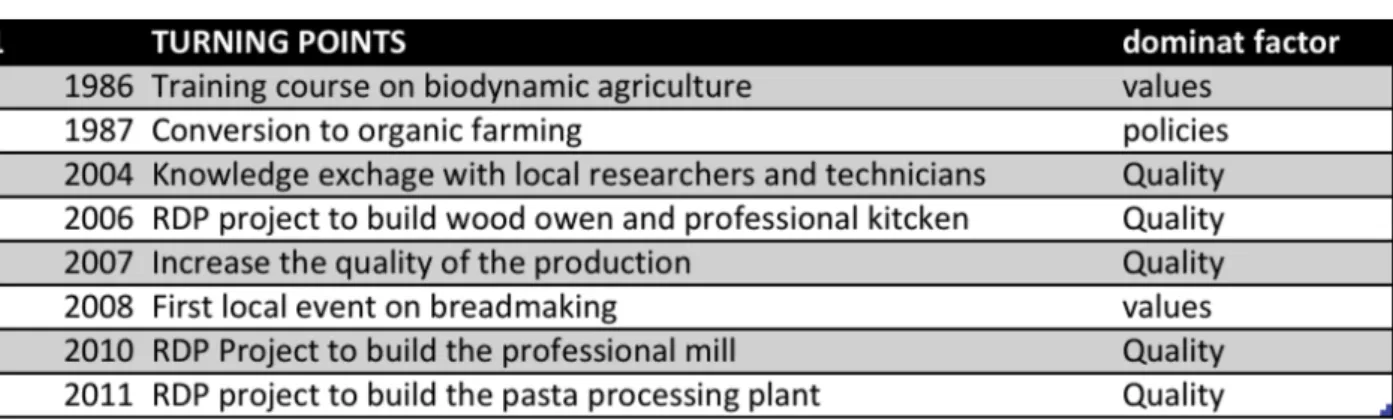

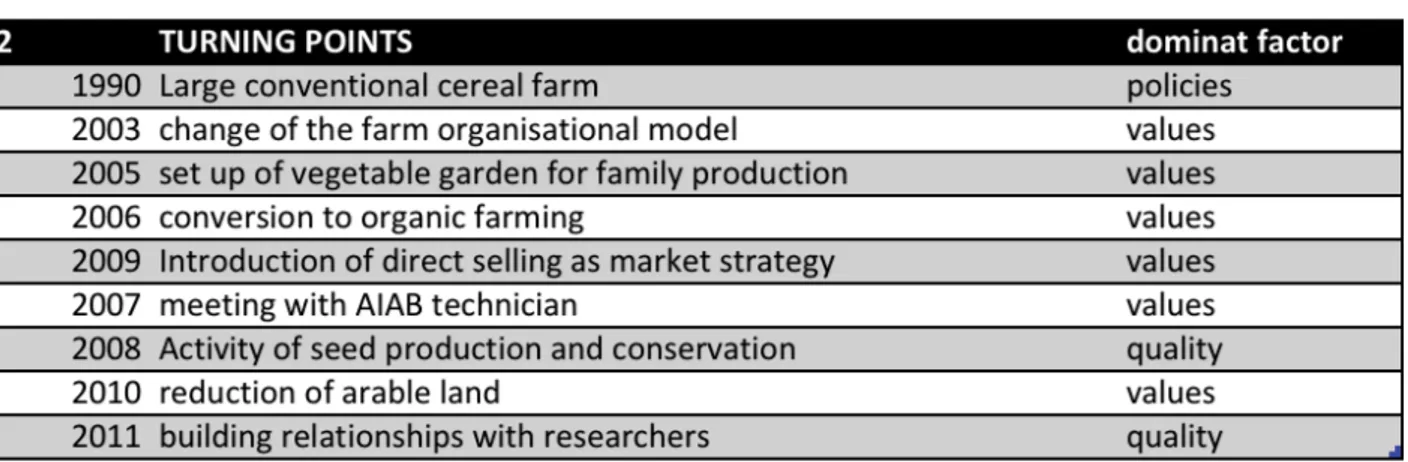

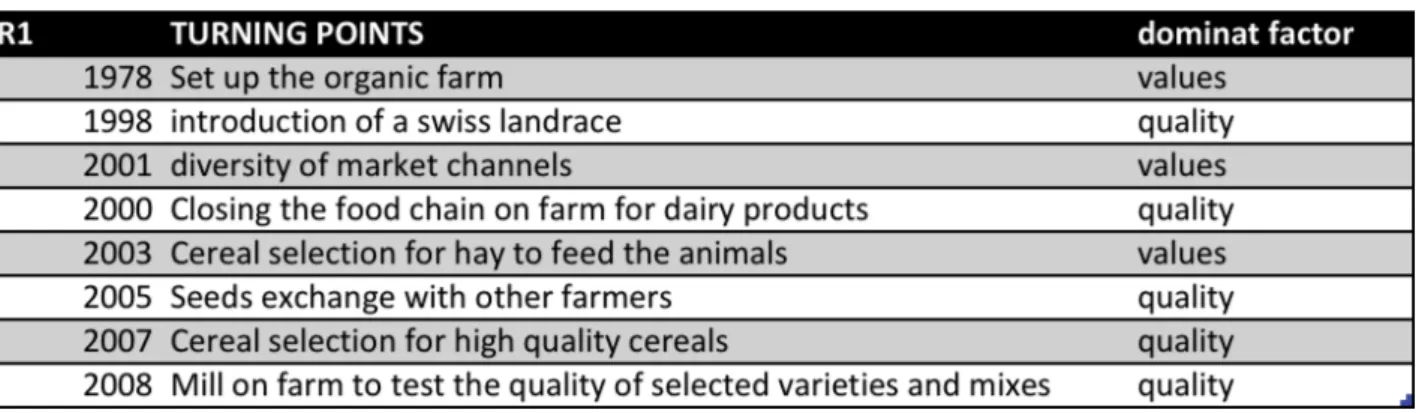

Table 3 – Main turning points in the transition of farm IT1 Table 4 – Main turning points in the transition of farm IT2 Table 5 – Main turning points in the transition of farm FR1 Table 6 – Main turning points in the transition of farm FR2 Table 7 – Main turning points in the transition of farm PT1 Table 8 – Main turning points in the transition of farm PT2

Table 9 – Distribution of attribute AIS in the six farmers ego networks.

Table 10 – Actors with higher betweenness centrality in the six farmers’ knowledge ego network. Table 11 – Legend for the attributes of the actors in table 10

Table 12 – The main features of farmers’ ego networks by category

List of figures

Figure 1 – Multilevel perspective of transitions Figure 2 -‐ Ego network graph

Figure 3 – Star and cycle graphs

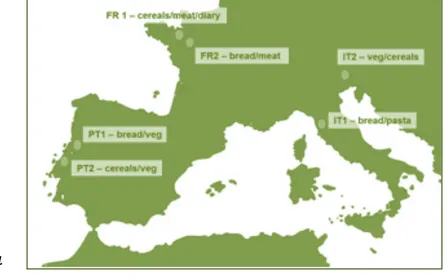

Figure 4 -‐ Location of selected case studies Figure 5 – Landscape of farm IT1

Figure 6 -‐ Pasta processing plant of farm IT1 Figure 7 – Landscape of farm IT2

Figure 8 -‐ Diversity in cereal fields of farm IT2 Figure 9 – On farm trials of farm FR1

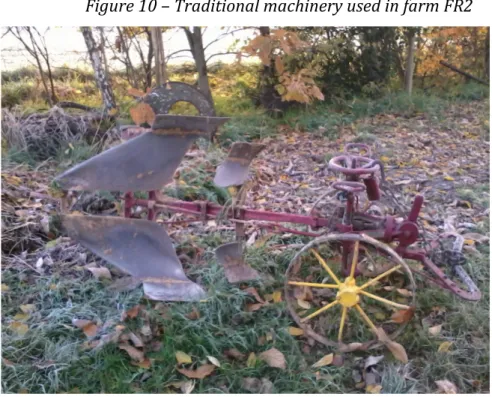

Figure 10 – Traditional machinery used in farm FR2 Figure 11 – Mill of farm FR2

Figure 12 – Bread produced on farm FR2 Figure 13 – Landscape of farm PT1

Figure 14 -‐ Distribution of the six case studies on the base of the dominant drivers of innovation Figure 15 – Data collection with participatory mapping exercise

Figure 16 -‐ Graph used as guide line to generate the list of actor Figure 17 -‐ Example of participatory map

Figure 18 -‐ Distribution of the attribute “Scale” in the six farmers’ ego networks.

Figure 19 -‐ Distribution of the attribute “Multi Level Perspective” in the six farmers’ ego Figure 20 -‐ Distribution of the attribute “Role” in the six farmers’ ego networks.

Figure 21 -‐ Goods and money networks of farmer IT1 Figure 22 -‐ Goods and money networks of farmer IT2 Figure 23 -‐ Goods and money networks of farmer FR1 Figure 24 -‐ Goods and Money network of farmer FR2 Figure 25 -‐ Goods and money networks of farmer PT1 Figure 26 -‐ Goods and money networks of farmer PT2

Figure 27 –All degree centrality and distribution of MLP attribute by similarities

Introduction

The debate on sustainable development has made apparent to all the serious adverse effects and the ecological risks of industrial development. Nonetheless, even if sustainable development is a widely accepted scientific and political concept, its definition is still ambiguous and surrounded by complex and socially contested issues (Barbier and Elzen 2012). The idea of sustainability as a normative notion that should assure justice among humans of present and future generations and among humans and nature (Baumgartner and Quaas, 2009) has several interpretations depending on the scientific approach and the political and economic parties' interests.

Sustainability is a moving target (Holling, 1993) and evolves continuously with the changing interests and institutional conditions, both locally and globally. By consequence, a successful approach to sustainability would require a continual modification, updating and improvement of human behaviour, which would actually increase the complexity of political decisions. In this perspective, an interdisciplinary and systemic approach to science, rather then a reductionist one, is the more relevant and appropriate (Holling, 1993, Kates et al. 2001, Clark and Dickson, 2003, Clark 2007).

The focus of sustainability science moved from the original definition of “maintaining the

global resource base for future generation” (OCED, 1987) to the study of the specific forms of

development in different local, ecological and cultural conditions. The main challenge of the sustainability decision-‐making process is to continuously select the best policy, considering a set of possible alternatives. The promotion of social and institutional learning for sustainable development and the understanding of the role of values in science and decision making for sustainability represent today key issues of sustainability science (Miller et al. 2014).

Network analysis represent a promising methodology in this sense as it allow to have an holistic approach to data analysis, considering also values in the research questions.

Three approaches to sustainability of agro-‐food systems

Since the 1970s environmental and resource economics has been established as a discipline, with a focus on natural resource scarcity and the regulation of their utilization (Hotelling, 1931). The key question in environmental economics is how to value changes that can affect environmental quality or availability of resources. The main aim is to define maximum degradation threshold and the carrying capacity of the system.

Agriculture, such as all other economic sectors, can have positive and negative externalities on the economy. However being a land base activity it is also directly affected by other sectors externalities. The presence in agriculture of a large number of farms and different models of production (industrial farm, entrepreneurship farms, peasant farms, Van der Ploeg, 2009) makes difficult to differentiate environmental damage across firms (Weersink et al, 1998). Furthermore the characterization of pollution from agriculture as a non point source's pollution make the use of environmental economic models difficult.

Contrary to the neoclassical economics, the ecological economic approach (Boulding, 1966, Daly 1973, Munda, 1997) considers economy as a system subject to transformation that cannot be corrected with incentive and policies (Smulders, 1995). The main objective is not so much to internalize negative externalities, as to improve the management of energy, matter and information, considering the long-‐term impacts. The consideration of costs should be enlarged with the concept of “performance” which includes costs and benefits in the long term. The use of money as measure unit is just a convention, which is not sufficient to reach a strong sustainability objective (Daly, 1974; Turner, Pearce, Bateman, 1994). This approach leads to the long debate on sustainability indicators that integrate various dimensions. Several multi criteria analysis models have been developed to measure sustainability of agricultural systems combining appropriate indicators (Reid, 1997, Martinez-‐Alier, 2002, Giampietro, 2010, FAO, 2012).

Table 1 -‐ Sustainability in three economic approaches.

Economic approach Objectives Modelling types

Environmental economics To measure the externalities and to define policies that allow to internalize them.

Linear optimization models

Ecological economics Mediation among values and priorities. Defining the trade off among three dimensions of sustainability.

Multicriteria analysis

Local development Local diversity as a key of competition. Looking at local learning capacity and systems of relations.

Network models

Source: own elaboration

The two economic approaches, that see sustainability as a reduction of negative externalities or an improvement of environmental performances, lead to expert-‐dominated discourses. However fixed rules and thresholds developed just on the base of scientific evidence are more likely to block, than to promote rural development, excluding rural actors and their (local, tacit) knowledge from the transition to sustainability (Fonte, 2008).

Environmental quality cannot be optimized without considering the effects of any economic intervention on local population and people's basic needs. The role of communities in defining and sustaining sustainable policy strategies is central. Sustainability becomes a question of governance: how to favor a positive change in the relationships between local actors, communities and their natural contexts (Stayeart and Jiggins, 2007) in a process that support local development, policy integration and participatory planning (Rubino, 2014).

According to Van der Ploeg (2006) the key for sustainability is to base food production in its agro-‐ecological settings. The conservation and valorization of biological and socio-‐cultural diversities is the path towards the sustainability of agro-‐food systems. The integrated policy approach used in the last decades by rural development policies at European level fostered innovative practices in rural areas such as organic farming, multifunctional agriculture and the creation of alternative food networks. The comprehensive assessment of innovative rural

practices can help to promote rural sustainable development (Berkes, Colding and Folke, 2003; Goodman, 2004, Bruckmeier and Tovey, 2009).

Environmental and sustainability issues should directly be linked to diversification and innovation policies, with a specific focus on agro-‐food systems and their effect on humans and nature. A continuous change in society is required to move towards sustainability. Innovation needs policy support. Assessment and measurements of sustainability should combine several methodologies and tools, with two main goals: improving the sustainability of innovative practices adopted by brokers; the promotion of practices able to support the transition to sustainability.

In the transition to sustainability the role of innovation is crucial, as technological changes are needed to meet sustainability challenges. However such changes need to be integrated with changes in rules, behaviors of individual stakeholders, culture, institutions and science. The contribution of innovation to the transition towards sustainability depends on several factors because system innovations are multi-‐factor, multi-‐actor and multi-‐level processes. The understanding of historical co-‐evolutionary processes that link up such elements is a key to define the contribution of a specific innovation to the specific transition towards sustainability (Barbier and Elzen 2012).

Agricultural innovation paradigms and sustainability

Different innovation paradigms originate different roadmaps to sustainable agriculture. The choice of the dominant paradigm clearly influences the direction of the transition pathway. The dominant paradigm of the EU innovation policies, the Knowledge Based Bio Economy (KBBE) strongly relies on technical innovation, with little attention on behavioral and institutional changes (Levidow et al., 2013). A reductionist approach to science is used to promote the role of life sciences with the aim of increasing efficiency in the use of renewable resources. This approach is based on a specific definition of sustainability as more efficient inputs and processing methods for using renewable resources, to develop capital-‐intensive technologies based on the life science knowledge. That allows a sequence of small incremental improvement of the dominant production process, without considering the effect on the

whole system, potential conflicts and network changes. There is a need to take into account the long-‐term effects that a specific innovation can generate (eg. plastic, GMO). The KBBE can lead to interesting innovation that could contribute to the transition to sustainability but it could also potentially turn agriculture into a factory-‐like production structure (Barbier and Elzen 2012) for the conversion of biomass or renewable raw materials (the so called “flex-‐ crops”) in food, health, fibers, energy and other industrial products.

In opposition to the dominant 'life science' paradigm, agro-‐ecology proposes the design of agricultural systems that minimize the need for external inputs and rely on ecological interactions (Levidow et al. 2013). Levidow characterizes the first as based on the 'decomposability of qualities' and agroecology as the integral product identity quality (Levidow et al, 2013, Allaire and Woolf, 2004), with consumers having an important role in defining the quality of the product.

With respect to innovation management the Knowledge Based Bio Economy innovation is research driven and based on scientific knowledge and intellectual property rights, defining specific policies for dissemination of science and transfer of innovation (Pfau et al. 2014), while the agro-‐ecology vision supports the development of Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems (AKIS) that considers innovation as a process of networking and iterative learning among an heterogeneous set of actors (Leewis, 2004, Hall et al. 2006).

The agro-‐ecological vision is more appropriate than the one of life science to deal with the ambiguity and the difference of sustainability goals depending on local conditions. The rely on ecological interactions, the consideration of integral product identity and the involvement of a variety of stakeholders in the development of innovation and research allow to identify the best solution at local level during the process of innovation itself. The two opposite visions (life science and agro-‐ecology) see the transition towards sustainability respectively as a system optimization or as a system innovation (Barbier and Elzen 2012).

The life science vision of the KBBE paradigm heavily relies on technological changes and an anthropocentric vision of sustainability that attempts to remedy specific problems within existing systems using add-‐on solutions. The agro-‐ecological vision, by contrast, looks at the possibility to redesign the existing system developing organizational and institutional changes to improve the sustainability of the system as a whole. The non-‐technical changes (I.e. Social) can be much more radical than the technical ones: new markets, new practices,

new regulations, new infrastructures and new values and cultural meanings have a strong effect on sustainability and their potential to improve sustainability performance is much greater (Weterings et al. 1997). However system optimization is easier to achieve and to be demonstrated and fewer changes are needed to have results in the short term. Policies should put more emphasis on the marginal vision described by Levidow et al. (2013) and on the agro-‐ecology paradigm of innovation in agriculture to assure sustainability of agriculture in the long term.

Looking at sustainability as a frontier that is continuously moving leads to two types of sustainability policies. Static policies that give a premium to individual or collective actors for incremental improvements; dynamics polices encouraging institutional learning processes and investments in institutional and organizational changes. Static policies look at innovation consequent from a KBBE paradigm while dynamic ones consider the agro-‐ecological vision and the agricultural innovation systems as models.

The opposite visions are reflected not only in European agriculture policies, but also in different models of agricultural practices. Different farm strategies depend on the dominant paradigm of the innovation system in which the farmer is embedded. The KBBE paradigm supports an industrial structure of agricultural enterprise with the global market as reference and technical innovations as corrective practices of environmental impact, required to access public subsidies. The agro-‐ecology vision looks at the best combination of resources available on farm to define models of production and pursuing farm autonomy as a goal that allow reducing the dependence on external inputs and technologies.

Transitions to sustainability at micro (i.e. farm) level follow different innovation models. Relations among different actors should be rebuilt in order to develop micro-‐policies of endogenous sustainable development at local level (Magnaghi, 2000). The capacity of each context to produce and access innovation largely depends on interactions between local actors, which have an intrinsic unique and dynamic nature (Morgan, 2004). Local innovation systems should have strong internal interconnections but also be opened to external linkages that can be used to generate new knowledge. The study of the relationships with actors that the farmer perceive as relevant for innovation development can provide interesting information on the direction of his transition pathways.

Hypothesis and methodology

The main hypothesis of this research is that the innovation paradigm, which drive transitions at micro level, directly influence the approach to sustainability followed by individual enterprises and their sustainability goals. The transition theory approach is integrated with actor network theory and social network analysis to conduct and in-‐depth analysis of six case studies of entrepreneurs in three EU countries. The focus is on the social environment surrounding individuals. Personal contacts and social circles in which individual entrepreneurs are embedded can give important information on the trajectories of transition to sustainability at micro level. Actors and practices are influenced by the context and the shared meanings of their knowledge network determine their approaches to sustainability; however, they can also contribute to determine the trajectory of the local transition to sustainability, towards their capacity to develop innovation. From a methodological point of view, this work will explore the potential of network analysis and of ego networks in particular, to understand the trajectories of transition at farm level. The visualization of an actor through the networks of his relationships can contribute in describing the actor position in the power relations that determine the local context. The analysis of transition at micro level, through the identification of turning points (Wilson, 2008) give important information on the dynamics of individual trajectories. The integration of such analysis with the network analysis should give some insights on how different drivers of innovations influence the structure of the knowledge ego network of individual entrepreneurs. At the same time, the analysis of the actors in the network could provide indications to transition studies on which is the context that support innovation development, or more precisely, which context support which type of innovation. Working on six original case studies, this research will give a contribution to the literature already working on the vision of the farm as a network and on the integration of transition theory with network theories. A literature review on the integration of transition and network theories in agriculture will be available in chapter 1; while chapter 2 will present the tools of social network analysis and ego networks that will be used in this research. In the next paragraph I will present the methodology used in this research.

Organic farming is used as an example of radical innovation in agriculture that had a long term and diversified shift from niche innovation to regime practice. Smith (2007) considers organic farming an interesting example of deviation from the original innovative trajectories in the process of scaling up that is worth understanding more in details. Organic farmers are everyday facing the trade off between the dimensions of sustainability in the process of defining farm strategies. An analysis of the literature on recent development of the organic sector will allow to understand the possibility of having different drivers of innovation in organic farms. In particular, the analysis will focus on innovative approaches to breeding in organic farming. Six organic farmers involved in the FP7 SOLIBAM project 1are the case

studies of this research. They represent farmers with original systems of practice that are of interest in the search for innovative systems. They are all organic farmers that are involved in Participatory Plant Breeding programmes in three different EU countries (Italy, France and Portugal). Their direct involvement in on farm innovation development, their interest and availability to be involved in research projects and their contact with researchers make them interesting case studies to test the relation between innovation models and sustainability approaches. The six case studies represent diversity in food systems following organic standards and different stages and transition pathways to sustainability.

After a long-‐term observation of the farms thanks to the SOLIBAM EU project started in 2010, primary data collection took place in the six farms during the year 2013/2014. An open ended interview aims to collect data about farm transitions through the farmer open description of his farm and food chain organisation. Last ten years investments have been taken into consideration to see the path of innovation at farm level. Additional quantitative data on structural characteristics of the six farms have been derived from researchers that made quantitative assessment of the same farms in the framework of the SOLIBAM FP7 project. The farm-‐level sustainability pathways of the six case studies have been conceptualised focusing on the decision making process at farm level. Chapter 3 will present the analysis of the organic sector transition from niche to regime (Smith, 2007) and the recent transitions of individual farms. The focus is on person based processes that influence transition pathways of individual agricultural stakeholders (Wilson, 2008).

Primary data on ego networks have been collected following a personal network research design (PNRD). The use of personal network research design allows the comparison of data collected from unrelated entrepreneurs in different countries. Ego networks describe and index the variation across individuals in the way they are embedded in local social structures allowing to understand variation in their behaviour. Farmers have been asked to describe their relational networks using an innovative approach to data collection. The use of participatory mapping exercise is tested as innovative methodology for network data collection in rural context. The data collected with the participatory mapping exercise resulted in paper maps done with markers and post-‐it (Fig. …). Each network map have been transferred into a matrix with the list of actors in row and columns. A number, 1 or 0, have been used to determine the presence or absence of relationship between two actors. A total of 18 matrices have been created and imported in the Pajek2 software. The actors listed by each

farmer have been described using 8 different attributes. Chapter 4 will presents the analysis of the farmers’ ego networks.

The combination of transition analysis and network analysis allow to have a dynamic vision of the process that lead to a specific knowledge network. For each farm the main drivers of innovation development will be identified on the base of the actors in the farmer knowledge network and the turning point of his transition. The presence of niche and regime actors in key position of the farmers’ knowledge ego network will give an indication of the trajectory towards sustainability of each farm. The interaction between niche-‐knowledge and regime-‐ knowledge can determine a hybridization of networks that lead to the development of knowledge between tradition and modernity (Sautereau, 2010). Finally three possible trajectories of transition towards sustainability of organic farmers will be described on the base of the structure of their knowledge network and the type of actors involved. This discussion of the two analysis of the six case studies will be done in chapter 5.

2 Pajek: (Slovene word for spider) is a program for analysis and visualisation of large networks. Is is freely available,

for noncommercial use. Pajek is developed by Vladimir Batagelj and Andrej Mrvar. A detailed introduction to Pajek is given in the book De Nooy et al. 2011.

1 Transition theory and Network approach

1.1 Introduction

This chapter introduce the theoretical framework of this research based on the integration of transition and network theories in agriculture. The first section will present a literature review on transition theory with a focus on the multilevel perspective and in particular on the shift from niche to regime. The next section introduces the actor network theory to explain how the relationships in which an actor is embedded influence his decision-‐making process; while at the same time the actor choices determine the context. The two theories are then applied to the agricultural context. The literature on agricultural innovation systems underline the importance to look at farmers knowledge networks with the aim of exploring the learning process that generate shared meanings among actors of the same network. The hypothesis that the existence of powerful and effective knowledge network could support the shift from niche to regime of innovative practices developed by individual actors justify the integration of the two theories. However, the farmer is not embedded only in knowledge networks, but other actors are also influencing his everyday decision-‐making process. Each farmer can be seen as a network itself where several actors interact among each other determining the farm structure. The concept of farm autonomy, proposed by Van der Ploeg (2008) is, finally, presented as shared meaning on sustainability based on relationships management at farm level.

This theoretical framework will support the analysis presented in the next chapters of this thesis. The transition theory will be at the base of the analysis of farm transition presented in chapter 3. The actor network theory and the literature on agricultural knowledge systems will support the ego-‐network analysis of farmers’ knowledge networks, while the vision of the farm as a system and the farm autonomy model will give indication to discuss the organizational model of the six case studies presented in chapter 4. Focusing on six original case studies of innovative organic farms, this research want to give a contribution to the literature that see the farm as a system.

1.2 The multilevel transition theory and pathways to sustainability

Even if most governments agree on the necessity to make sustainability a guiding principle of their policies, it is not clear how to achieve it (Barbier and Elzen 2012). The ‘multilevel transition’ theory can help in defining the governance of the process that should lead to sustainability.

The conceptual sources of transition theory derive from several disciplines, such as innovation studies, evolutionary economics, sociology of technology and governance studies. Its main objective is to use an interdisciplinary approach and narrative explanations to illustrate the process of scaling up of a specific innovation and to learn from historical examples of transitions such as energy and transport systems (Verbong and Geels 2007; Geels, 2012). Environmental sustainability offers an interesting application field of the theory (Kemp, 1994, Geels, 1999, Geels and Kemp, 2000). Several authors utilise case studies to shows how transitions often depends on the interaction among different levels of analysis, that can change in time and nature (Rotmans et al. 2001; Geels, 2002; Van der Ploeg, 2003; Elzen et al. 2004, Geels, 2005).

Geels and Schott (2007), distinguish three levels at which correspond three analytical concepts: niche innovations, socio-‐technical regimes, socio-‐technical landscapes. The socio-‐ technical regime is defined as the shared cognitive routines among scientists, policy makers, users and special interest groups that contribute to define the pattern of technological development in a given sector (e.g. the agro-‐food system). Each socio-‐technical regime is embedded in society and linked with a wide variety of social actors and rules, which justify the term ‘socio-‐technical’. Existing trajectories of innovation stabilise with the diffusion of a specific socio-‐technical regime. An innovation reach the status of ‘regime’ when citizens adapt their life style to technical systems and enterprises make sunk investments in machines, infrastructure and competencies required by the specific innovation. Policy and science can influence this process through the definition of standards and regulation and the diffusion of cognitive routines that are used as a base for the research agenda.

Technological niches are the micro-‐level where radical novelties emerge and radical innovations are developed. Niches are protected spaces that offer the opportunity to experiment technology, user preferences, practices and regulations while minimizing risks.

Niche innovations are carried on and developed by small networks of dedicated actors, often outsiders and fringe actors that use a protected environment to progress price/performance improvements, to ask for support from powerful groups and to develop learning processes.

The socio-‐technical landscape represents the exogenous environment that cannot easily be influenced by the niche and regime actors. Macroeconomics, deep cultural patterns and macro-‐political development influence not only the regime of the sector under analysis but also many other regimes. Changes in landscape take place slowly and needs decades to have effect on a specific regime; however, they should be taken into consideration as they can change the direction of a specific transition pathway both directly and indirectly.

The three concepts are related to each other through a nested hierarchy: regimes are embedded within landscapes, niches within different regimes (Geels, 2002). Changes in the landscape create pressures in the regime that can lead to a destabilisation and opening of windows of opportunities for niche innovations. The multiple possible interactions between the three levels are shown in the popular figure of Geels and Schot (2007).

Figure 1 – Multilevel perspective of transitions

The hypothesis that we take into consideration in this work is that transition to sustainability requires changes in the dominant regime. Regime changes are due to two main types of processes: 1) pressures -‐ at landscape level, internal to the socio-‐technical regime or at niche level – bring into evidence and emphasize conflicts or the regime’s incapacity to answer to new society demands and challenges; 2) the capacity of the regime to coordinate available resources inside and outside the regime to face new challenges. The pressure on the regime can be related to broad political, social and economic landscape development such as demographic shifts, rise of a new consumer culture, neoliberal model of globalisation, or economic pressures such as competition, taxes, charges, regulations etc. However, it can also emerges from below, from innovative niches that are ready for stabilization. Berkhout et al. (2004) assume that some pressures are always present. The capacity of adapt to such pressures depends on the regime availability of resources (factor endowments, capabilities, knowledge) and the degree of coordination of resource deployment.

Using the MLP model, Barbier and Elzen (2012) illustrate two different pathways of innovation influencing the transition to sustainability. One is based on a strategy of optimization: according to the KBBE (Knowledge-‐Based Bio Economy) innovation paradigm, in presence of landscape pressure, the regime gradually leads to the development of innovative activities. Technical and societal or behavioural changes of incremental nature take place in the regime improving its performance. The role of niches is not relevant or is minor in the system optimization process and they remain marginal experiences (incremental optimization of the regime).

The second is more radical in nature and leads to the reconfiguration of the dominant regime. In this case, the regime actors resist to pressures exerted, considering the required changes as “unrealistics”. At the same time outside actors see the landscape pressure as an opportunity for niche innovations. Solutions that are more radical are developed in a variety of niches and outside actors learn how they can support the scaling up process, through technical aspects but also consumers’ requirements, markets, regulations etc. If this process is successful, the niche innovation can link up with existing regimes through symbiotic or competitive relationships and gradually change or replace it.

The multilevel perspective has been used to describe, reconstruct and analyse a variety of historical cases of system innovation such as the transition from sailing ship to stream ships (Geels, 2002), the field of transport studies (Geels, 2012) and the transition of energy systems

(Verbong and Geels, 2007). The transition to low carbon economy (Geels, 2014) has been studied more recently with this perspective with a focus on care farming (Hassink et al, 2013), organic farming and eco housing (Smith, 2007), carbon trust (Kern, 2012).

1.3 The shift from niche to regime as a key for the agro-‐ecology vision

The interrelations between niches and regimes are key to understand changes required by the sustainable development agenda. The processes by which niches and regimes interact and are interdependent are called ‘socio-‐technical translations’. Niches may be sources of innovative ideas, functional to solve regime tensions and bottlenecks. They may lead to transformations or reconfigurations of the dominant regime.

In particular green niches have been increasingly studied by innovation literature as they represent significant sites of learning and network building for sustainable technologies. Strategic niche management (SNM) becomes a specific field of study looking at dynamics of niche development. Niches represent essential sources of systemic changes if processes at other levels of the system are supportive (Loorbach and Rotmans, 2006). If the regime is under pressure to become more sustainable, as in the present context, green niches are more likely to displace incumbent “socio-‐technical” regimes and diffuse into the mainstream. The study of strategic niche management makes an important contribution in the analysis of radical shifts in technological regimes required by the ecological restructuring of production and consumption patterns (Hoogma, 2000). Changes in consumption patterns, user preferences, regulations and artifacts can be experimented at niche level before scaling up.

A variety of mutually reinforcing social, economic and institutional and technological processes sustain existing trajectories of development. The “socio-‐technical” regime defines these complex structures and the web of interdependencies between artifacts, institutions and agents. The concept of socio-‐technical regime underlines the social nature of all technological entities and the difficulty to make a distinction between social and technical elements, institutions, actors and sphere of activity (Smith, 2007). User practices may shift between niche and regime starting from very different socio-‐technical situations. However, as historical experience suggest, radical changes begin within networks of pioneering organizations, technologies and users on the margins of the regime. These actors create

exemplars in the protected space that, if successful, become sufficiently robust to develop markets and attract wider interests from the mainstream (Schot et al. 1994). The new innovation makes pressure for a widespread change that allows the development of more sustainable technologies.

The study of strategic niche management focus on two main aspects: the quality of learning

and the quality of institutional embedding (Kemp et al.1998). Learning should consider

different features: from the narrowly technical performance of the innovation to the needs of specific infrastructures. The user context, the meanings users give to a niche practice and the economic performance need also to be explored, as well as institutional and policy changes needed to stimulate further niche growth.

Institutional embedding relates to the support that the niche have at technical, market, social and institutional level. This includes the need for complementary technologies and necessary infrastructures and the development of widely shared expectations about future niche development. Finally there is a need for a broad network of supportive actors of the niche socio-‐technical practices and of the future regimes it prefigures (Smith 2007). The network of users and outsiders embedded in a specific niche and their contribution to the learning process determines the robustness of a specific niche and shows its growth potential (Hoogma et al. 2002). The actors’ preferences and meanings are influenced by experiences on one side and norms from the regime on the other side and have a direct impact on actors’ individual engagement with the niche and its institutional embedding.

Niches alone are unlikely to transform the regime. According to Smith (2007) their compatibility with the regime is the variable that most influences their success. Radical niches, that imply major structural changes, such as developing sustainable innovations, will require an adaptation to the dominant regime in order to scale up. In fact regulations, infrastructure, user practices and maintenance networks are aligned with the existing technologies in the regime and radically new technologies do not easy break through (Geels, 2002). For this reason Smith (2007) stress the need of strategic niche management. Understanding of the regime tensions that provide opportunities for niches are crucial in the up-‐scaling process of niche innovations and may provide important policy suggestions in order to push development along a new trajectory. Transformation dynamics depends on