ARTIFICATION PROCESSES FOR MAJOR LUXURY BRANDS: ART-BASED MANAGEMENT FOR BRANDING PURPOSES

Stefania Masè, Ipag Business School, France

Geneviève Cohen Cheminet, Sorbonne University, France Elena Cedrola, Macerata University, Italy

ABSTRACT

Artification offers luxury brands an interpretive framework to improve their image through the application of art-based management strategies. Via an in-depth literature review and secondary data analysis, a new model is designed to synthesize the operations which luxury brands may implement to channel artification processes to their benefit.

INTRODUCTION

Since the early 1980s, luxury has experienced a series of structural changes that have radically transformed it, primarily affecting volumes and characteristics of handmade. Over a thirty-year period, the luxury sector went from a network of artisans, craftspeople and family-business production to become an industrial and financial sector. As a result, luxury houses are brands which have moved further away from the pattern of handicraft companies able to master manual techniques. They now are business companies able to produce and distribute vast quantities of goods of high quality with higher price tags. These structural changes originated from the growing demand of consumers in emerging markets. They are noticeably different from mature market consumers where luxury producing companies are headquartered. The vast dimensions of these emerging markets require skills that small and medium-sized luxury craft businesses usually do not have, such as brand management skills or the implementation of economies of scale. As a result, many luxury companies made the decision to join luxury groups as a way of increasing their production volumes, financing their world retail expansion, shifting their focus from production to retail, from local to worldwide (Kapferer, 2015).

The negative consequence of this structural change in the luxury sector is the loss of rarity or exclusivity of goods in the eyes of mature market consumers. In emerging countries, however, the danger is different. If luxury brands do not expand their production, they risk losing consumers in favor of competitors more accustomed to larger production volumes. In emerging markets, luxury hierarchies are still open and luxury brands know they need to cater to the needs of consumers for whom the concept of exclusiveness might not come first, and for whom brand awareness is by far the most

significant factor that declares their higher social status. In these mainly Asian markets, only a well-known major luxury brand can fully play its discriminating role as ‘social stratifier’ (Weber, 1947). This means that in emerging markets contemporary luxury must be more consumer-oriented than in such mature markets as Europe or North America. Since luxury brands now have to increase their production and sales volumes to be active on such huge markets as China, they face the challenge of preserving the rarity and exclusivity of their products so as to keep consumers in mature markets from feeling betrayed (Kapferer and Valette Florence, 2016). Luxury companies face a loss of confidence from mature market consumers who are increasingly informed and critical of higher volumes. Since luxury craft-based enterprises are now brands, they face the challenge of preserving their historic image based on beautifully hand-made luxury. They need to reexamine their image and corporate social responsibility exactly like enterprises belonging to the oil, financial or tobacco sectors (Kottasz, Bennet, Savani and Ali Choudhry, 2008; Lindenberg and Oosterlinck, 2011). In this larger strategic context, scholars have shown luxury brands can focus on technology, geographical proximity, art and culture in order to preserve their images (Weideman and Hennings, 2013). In this research, we focus on a valuable and viable strategy based on support for the arts and culture through philanthropic or sponsorship activities, collaborations with artists, and most importantly, the creation of private collections and foundations of art which constitute national cultural infrastructures (Hetsroni and Tukachinsky, 2005).

This strategy is valuable as major luxury brands benefit from a specific understanding of the power of art and aesthetics in society at large. Artification has been approached as a cultural process that is active in contemporary societies with examples from performing

arts, gourmet cooking, tattooes and elite wine (Heinich and Shapiro, 2012). It has changed collective views on the legitimacy of the relation of art and artists to markets, business companies, commodities and profits (Carlucci and Schiuma, 2018). Understanding the stakes of artification in society means being alert to the ‘aestheticization of the world’ (Michaud, 2017) which defines today’s ‘aesthetic capitalism’ (Assouly, 2008) also called ‘artist capitalism’ (Michaud, 2017). The new cultural authority of the arts which is noticeable in the current cult of design artists is the larger context in which luxury conglomerates and such luxury brands as Louis Vuitton, Prada or Cartier position themselves on art-related strategies and wish to better perform. What determines the reception of their strategies is the contextual porosity of contemporary art borders and cultural changes in the current perception of what is or is not art. This context has allowed luxury brands to state that they belong to the art world with full legitimacy.

We argue here that their push from luxury into art is attributable to these wider social processes called artification. Their effects on luxury have changed collective views on the legitimacy of the relation of artists to luxury companies, commodities and profits. However, the strong resistance to the connection of art and money in most Western societies has affected both luxury brands and artists who dare challenge the myth of ‘disinterested art’. Both luxury brands and artists are impacted by this lingering resistance to money in association to art. Today, artists and luxury brands still face the conflicting yet never quite reconciled logics of art and profit (Joy and Sherry, 2003). What is interesting today about major luxury brands like Louis Vuitton, Prada or Cartier is that their position in financial conglomerates gives them the economic strength and clout to

connect their products directly to the art world, without any intermediaries as they are legitimate art institutions by themselves. We choose to analyses these new roles from the larger perspective of artification processes in which brands have taken on the roles of art institutions.

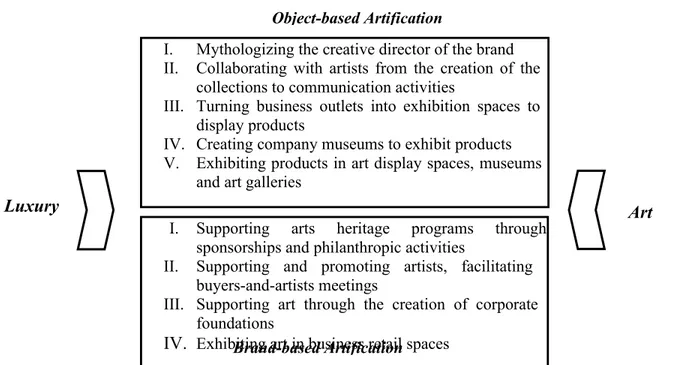

We start with the key aspects of artification processes, and then we describe the actors participating in artification processes at work in the interface of luxury and art. We then consider the new art-based management perspective, recognizing the strategical importance of art for business (Carlucci and Schiuma, 2018). A new theoretical approach to luxury is then suggested. Finally, we designed a specific model to synthesize the various operations which luxury brands may implement to channel artification processes to their benefit. Our model combines two levels of analysis, ie the level of the luxury object (hereafter object-based artification) and the level of the brand in its newly acknowledged role as art subject (hereafter brand-based artification). We end with potential research developments in brand analysis and managerial implications for brands in the luxury sector.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

American anthropologist Ellen Dissanayake took an interest in the notion of artification focused on the transformation of an ordinary object into an artwork which she attributed to man’s adaptive capacity to transform through the use of colors, design or lines (Dissanayake, 1995). Then, artification was elaborated upon by two groups of Finnish and French scholars. Finnish scholars worked in aesthetics and described situations in which an object outside the art world is turned into an artefact that can be requalified as

art, or recognized as ‘art-like’ because it bears the visible influence of artistic practices (Naukkarinen and Saito, 2012; Scrivener and Zheng, 2014). This approach is reminiscent of Art Infusion from Hagtvedt and Patrick (2008a, 2008b) who elaborated upon the influence of art on consumer perceptions of products whenever advertising or product design clearly connected them to art. French sociologist Roberta Shapiro and art sociologist Nathalie Heinich observe how art practices have been slowly legitimized as Fine Arts, and offer a typology of artification components (Heinich and Sahpiro, 2012). Then, the notion of artification was transferred into management with a different perspective centering on perceptions of art by luxury brand consumers (Kapferer, 2014). Sociologists Heinich and Shapiro have analyzed how photography, cinema, comics, graffiti, performance and living arts went from ordinary commercial practices to legitimate art status. Requalification as art is a legitimation process that originates from consensus among certain agents (artists, art dealers and collectors, art curators, scholarly institutions, legal experts, the general public, etc.) who agree on the appropriate, acceptable and desirable criteria for art. Norms for art are prescribed by bodies of legitimation called ‘instances’ or institutions of legitimation’ by Heinich and Shapiro (Heinich and Shapiro 2012).

What contemporary visual artists have challenged is of interest to luxury brands: they have challenged the distinction between art and ordinary life. The brand promotes artists and world-class exhibitions. The brand is both a part of contemporary artification processes which have requalified ordinary objects as art, and is an active contributor to cultural evolutions. Louis Vuitton via its Foundation recently opened is a body or an ‘instance of legitimation’ of contemporary art. However, this double role reactivates the

age-old conflict over the relations of art and money and gives additional force to the fierce cultural nexus of conflicting views at the core of contemporary art. Luxury brands are very much aware of these transgressions of accepted art norms. They define our common cultures.

CONTEMPORARY INTERFACE BETWEEN LUXURY AND ART

Luxury artefacts are not art per se. But they are part of contemporary processes of artification because luxury brands knowledgeably implement art-based strategies that fit the processes of artification as luxury brand managers are well-versed in the changes brought about by the contemporary art scene.

The turning point in understanding the management stakes is the moment when luxury Maisons turned into major conglomerates in the1980s. They had been part of ongoing processes of artification like other creative industries but they became active players in the art market. Belonging to giant holdings has given them the financial strength to pursue new ambitious strategies. An example is Fondation Cartier that was created in 1984 by Cartier SA firm as a center for contemporary art. Fondation d’entreprise Hermès runs cutting-edge exhibitions at La Verrière (50 boulevard de Waterloo, 1000 - Brussells, Belgium). Fondazione Prada has run major exhibitions since 1993 with works from the 1950s to the present showcased in an 18th-century palazzo on the Grand Canal in Venice. Since 2015, they have had new space in Milan designed by architect Rem Koolhaas and his firm OMA. Louis Vuitton foundation for contemporary art started in 1990 as Fondation d’entreprise Louis Vuitton and became Fondation Louis-Vuitton pour la création in 2006 before opening in 2014. They are all major museums, and art curators

are well aware that the contemporary art scene would be radically different without these foundations/brands’ major support (Pappalardo, 2014). Foundations/brands have closely analyzed their role as active artification agents and once again, sociologists Heinich and Shapiro help us understand why these institutions/brands are part of the four circles of artistic recognition (Bowness, 1990) These four circles of legitimation describe who the actors of artification are. First come the producers of art who claim the status of artists. Second, merchants, gallerists, publishers, mediators in art and culture contribute to their recognition by exhibiting their works. Third, critics, curators, exhibition commissioners, art experts provide scholarly expertise. Fourth, the general public witnesses the evolution of the art world based on the previous three circles of expertise and legitimation.

For major luxury brands, these circles of expertise and legitimation prove that being active in the first three circles will work in their favor. They have acquired the status of legitimate art authorities from artists (circle 1); from merchants (circle 2); from museums and scholars (circle 3). It is only a matter of time for the general public to acknowledge their role as art institutions /brands which also produce luxury goods.

Researching these actors has already been done from different angles. Luxury products are usually analyzed through consumer perceptions (Dubois, Czellar and Laurent, 2005; Dubois and Laurent, 1994; Vigneron and Johnson, 2004). Perceptions of art and luxury widely differ: artists and art experts no longer place art forms along a hypothetical continuum ranging from low-brow to high-brow art forms. However, management scholars still commonly separate élite from popular arts in consumer perceptions (Colbert, d’Astous and Parmentier, 2005; Hagtvedt and Patrick, 2008a, 2008b). They account how in the luxury sector consumers perceive luxury gradations that can be

calculated through the various measurement scales that have been proposed over the years (De Barnier, Falcy and Valette-Florence, 2012).

What complicates perceptions is that luxury-defining criteria have changed over time and in space depending on local cultures (Aiello, Donvito and Vescovi, 2013). We wonder if the correct question would then be when is art/ luxury, instead of what is art/ luxury (Goodman, 1977).

A NEW MODEL FOR LUXURY BRANDS ARTIFICATION

To maintain perceptions of rarity and higher value, luxury brands need to prove their claims to exceptional singularity in a time when accusations of ‘packaging up cultural life into a saleable commodity’ in ‘a throw-away culture of unrelenting consumerism’ (Anderson, 2009, 131) are common. When luxury brands co-produce objects with artists (hereafter called artified products), brands and artists disruptively claim the result of their collaboration is art. In order for this claim to be perceived as legitimate, brands need to be known as legitimate artistic institutions and art agents who are knowledgeable about the art of their time. This research hypothesizes that luxury brands must be part of the three circles of art mentioned earlier and implement strategic decisions based on a strong familiarity with the processes of artification which we view as part of a disruptive cultural ecosystem that challenges mainstream views of what is or is not a legitimate art object. From a diachronic perspective, the early relationships between art and business used to be based on philanthropy, sponsorship or art collecting activities that evolved over time into more complex structures (Thompson, 2005). Artification is the most far-reaching mode of connection between art and business, because its processes incorporate

the various potential forms of connections between the two sectors, including sponsorship, philanthropy and corporate collections (Dion and Arnould, 2011; Joy, et Al., 2014; Riot, Chamaret and Rigaud, 2013). The ultimate goal is to have artified luxury products that originated from artists’ collaborations recognized as legitimate works of art. The indispensable prerequisite for recognition is the related recognition of the luxury brand itself as a new art institution in a process that involves luxury brands, arts and cultural institutions (Heinich and Shapiro, 2012; Shapiro and Heinich, 2012).

We therefore suggest to conceptualise artification as social and cultural processes which combine two levels of analysis, ie the level of the object (object-based artification) and the level of the brand in its newly acknowledged role of art agent or subject (brand-based artification). Each level of artification is mutually influencing and includes a series of factors that can be applied by the brand. Figure 1 shows the artification model for luxury brands, with its two levels of analysis and the different factors.

Insert Fig. 1 – Model of artification for luxury brands

In object-based artification, artified products that originated from artists’ collaborations need to be perceived as legitimate works of art.

In brand-based artification, it is the whole brand that needs to be perceived as a legitimate, active and decisive keyplayer in the art world. Based on the analysis of the literature and research both in marketing and in Visual Studies, we suggest a series of factors contributing to the processes of artification which luxury brands may channel to their benefit to regain perceptions of exclusivity and rarity.

Object-Based Artification

The first factor is the recognition of artified products as art works. It is not an easy-to-control process. However, mythologizing the creator of the brand contributes to the transformation of the brand’s creative director from artisan to artist (Dion and Arnould, 2011). By implicit imputation, the products created by the artist might be considered artistic. Creators are professionally called ‘designers’ (stylistes) or ‘technical designers’ (modélistes) and are often elevated to the level of artists with the resulting re-categorization of their production (e.g. Coco Chanel, Alexander McQueen, Marc Jacobs or Karl Lagerfeld). Whenever they are exhibited, their claim to artistic status is strengthened (Crane, 2012), as was the case with Christian Dior at the Grand Palais (2013), or Dries Van Noten at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris (2014) or the Manus x Machina 2016 exhibition held by The Costume Institute, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In view of this museum trend, sociologist Diana Crane (2012) observed that certain haute couture and ready-to-wear lines in textile apparel and accessories have only reached a partial level of artification because of their recent transformation into brands. This has negatively resulted in a form of de-artification that has damaged their slow-going recognition as art agents. This explains why couture and avant-garde lines have a lower value and recognition than artworks.

A second factor in object-based artification is the fact that artists collaborate with creative directors for collection design and communication activities. Whenever the artist is well recognizable by final consumers, his/her collaboration may be considered co-branding as

the Louis Vuitton collections partnered with artists Yayoi Kusama or Takashi Murakami (Schroeder, 2005; Riot et Al., 2013).

A third factor is the transformation of the store into an art gallery which displays the brand, the products, the works of artists, and showcases the products as artworks. The point of sale is increasingly meant to look like a museum (Dion and Arnould, 2011; Riot, et Al., 2013). A fourth factor we suggest is the creation of a museum dedicated to the brand (e.g. the Gucci museum or the new Yves Saint Laurent museum in Paris).

Interestingly, luxury products exhibited in a museum context take on additional art legitimacy by being implicitly deemed worthy of being displayed in the vicinity of true art. The discourse on the brand may contribute to the dissemination of its value through such museum sales, one noted example being the Louis Vuitton Takashi Murakami Monogram Cherry Blossom line sold on Eastern Parkway in the Brooklyn Museum, New York (April 5-July 13, 2008). This is the fifth factor of object-based artification.

We claim these 5 key factors will contribute to the processes of artification which luxury brands may channel to their benefit to regain perceptions of exclusivity in final consumers.

Brand-Based Artification

In brand-based artification, it is the whole brand that needs to be perceived as a legitimate, active and decisive keyplayer in the art world.

A first factor is brand sponsorship of arts heritage programs and philanthropy, as the recent Fendi restoration of Fontana di Trevi proved, or the new Fendi headquarters now located in the historical Palazzo della Civiltà, both in Rome (Fendi, 2017).

A second factor is the support for the arts in order to facilitate closer exchanges between luxury targets and the art world. A valuable example is the Rolex Mentor & Protégé initiative which connects confirmed artists and younger ones while the brand acts as art collector (Rolex, 2017).

A third factor is the creation of arts foundations such as Fondation Louis Vuitton Pour l’Art Contemporain or Mont Blanc Cultural Foundation. It involves management operations, institutional and organizational strategies which all contribute to artification, since the Fondation is a major art museum operated by a private firm. Unlike Pompidou Center or Musée du Quai Branly which are state-run, a privately-run museum of equal quality and scope alters perceptions of the disconnect between art and business and legitimizes the role of brands in the art world.

Fondazione Prada, Fondazione Trussardi or Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain (Masè and Cedrola, 2017) have contributed to the same process of recognition of the role of luxury business in art.

The fourth factor is exhibitions in retail spaces e.g. artists like Vanessa Beecroft or Olafur Eliasson showcased their artworks in the windows of luxury flagship stores (Masé and Silchenko, 2017).

These four factors contribute to the processes of artification which luxury brands may channel to be perceived as art institutions. Luxury brands can manage any of the factors that contribute to artification processes which we describe here. This theoretical model

will help guide object-based or brand-based strategies or strategies that combine the two. Application will depend on brands’ strategic needs and financial means.

CONCLUSION

The dynamic growth of the luxury market has transformed the conspicuous consumption model that underlies luxury brands. They need to select consumers via prices and, at the same time, they must be known by growing segments of consumers, especially in Asian countries and in the Middle East where the consumption of luxury brands is increasing. Competition moves luxury from logics centered on offer and originality in creation to logics based on consumer demand, competition and market needs. The main danger stemming from differences between markets is that consumers who buy luxury brands tend to frequently travel for business or pleasure. They are better informed of the differing perceptions of a brand in world markets.

Some luxury brands have already set into motion the various mechanisms involved in processes of artification to implement a double brand-based or object-based artification strategy. We hypothesize that luxury businesses strategically enter the art world to be recognized as legitimate art players, therefore channeling artification processes to their benefit to elevate themselves from the level of producers of luxury goods to the perception of legitimate creators of artworks. Artification helps them get recognition as they move from creative to cultural industries.

Companies that have achieved the highest commitment to the art world, in terms of brand-based or object-based artification, are primarily luxury brands like Cartier, Louis Vuitton, Hermès, Prada, Trussardi and Fendi. The recognition of their legitimate roles in

art can nurture their needs for brand image and ensure a cultural connection with all of their markets. Future research can be focused on in-depth case study analysis on major luxury brands connected to the art field, to highlight their object-based and brand-based artification strategies.

Watching the processes in which artified objects and practices are slowly categorized as legitimate art will help managers understand how these slow artification processes operate. They will better understand what forces and actors are mobilized in the new luxury and art meta-market.

REFERENCES

Anderson, J. (2009). Understanding Cultural Geography: Places and Traces. Abingdon: Routledge.

Aiello, G, Donvito, R. and Vescovi, T. (2013). Creativity and Passion Between Global Branding and Country of Origin Roots. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science 23(4):357–360.

Assouly, O. (2008). Le capitalisme esthétique. Essai sur l'industrialisation du goût. Paris: Cerf. Bowness, A. (1990). The Conditions of Success. How the Modern Artist Rises to Fame.

Walter Neurath Memorial Lectures. Thames & Hudson: London.

Carlucci, D. and Schiuma, G. (2018). The Power of the Arts in Business. Journal of Business Research. 85: 342 – 347.

Colbert, F., D’astous, A. and Parmentier, M.A. (2005). Consumer Perceptions of Sponsorship in the Arts”. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 11(2), 215–228.

Crane, Diana. 2012. “La Mode”. In Nathalie Heinich and Roberta Shapiro (Eds.) De l’artification - Enquêtes sur le passage à l’art (241–251). Paris : Editions de l’Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales.

De Barnier, V., Falcy, S. and Valette-Florence, P. (2012). Do Consumers Perceive Three Levels of Luxury? A Comparison of Accessible, Intermediate and Inaccessible Luxury Brands. Journal of Brand Management 19(7): 623–636.

Dion, D., and Arnould, E. (2011). Retail Luxury Strategy: Assembling Charisma through Art and Magic. Journal of Retailing 87(4): 502–520.

Dissanayake, E. (1995). Homo Aestheticus: Where Art Comes from and Why. Washington: University of Washington Press.

Dubois, B., Czellar, S. and Laurent, G. (2005). Consumer Segments Based on Attitudes Toward Luxury: Empirical Evidence from Twenty Countries. Marketing Letters 16(2): 115–128.

Dubois B. and Laurent, G. (1994). Attitudes Towards the Concept of Luxury: An Exploratory Analysis. Asia Pacific Advances in Consumer Research 1: 273–278. Fendi. (2017). Il restauro della fontana simbolo di Roma. Accessed 17 December

2017.https://www.fendi.com/it/fendi-roma/fendi-is-rome/il-restauro-della-fontana-di-trevi

Goodman, N. (1977). When Is Art?. The Arts and Cognition (26): 11–19.

Hagtvedt, H. and MPatrick, V.M. (2008a). Art and The Brand: The Role of Visual Art in Enhancing Brand Extendibility. Journal of Consumer Psychology 18(3): 212–222.

Hagtvedt, H. and MPatrick, V.M. (2008b). Art Infusion: The Influence of Visual Art on the Perception and Evaluation of Consumer Products. Journal of Marketing Research 45(3): 379–389.

Heinich, N. and Shapiro, R. (2012). De l’artification - Enquêtes sur le passage à l’art. [Artification – Investigating the transition to art]. Paris : Cas de figure EHESS. Hetsroni, A. and Tukachinsky, R.H. (2005). The Use of Fine Art in Advertising: A

Survey of Creatives and Content Analysis of Advertisements. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising 27 (1): 93-107.

Joy, A., Wang, J.J., Chan, T.S., Sherry Jr, J.F., and Cui, G. (2014). M(Art)Worlds: Consumer Perceptions of How Luxury Brand Stores Become Art Institutions. Journal of Retailing 90 (3): 347-364.

Joy, A., Sherry Jr, J.F., (2003). Disentangling the paradoxical alliances between art market and art world. Consumption, markets and culture 6(3): 155-181.

Kapferer, J.N. (2014). The artification of luxury: From artisans to artists. Business Horizons 57(3): 371–380.

Kapferer, J.N. (2015). Kapferer on Luxury How Luxury Brands Can Grow Yet Remain Rare. London: Kogan Page.

Kapferer, J.N., and Valette-Florence, P. (2016). Beyond rarity: the paths of luxury desire. How luxury brands grow yet remain desirable. Journal of Product & Brand Management 25(2):120–133.

Kottasz, R., Bennett, R., Savani, S., Mousley, W. and Ali-Choudhury, R. (2008). The role of corporate art in the management of corporate identity. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 13 (3): 235-254.

Lindenberg, M. and Oosterlinck, K. (2011). Art Collections as a Strategy Tool: A Typology Based on the Belgian Financial Sector. International Journal Of Arts Management 13 (3): 4-19.

Masè, S. and Cedrola, E. (2017). Louis Vuitton’s Art-based Strategy to Communicate Exclusivity and Prestige. In B. Jin and E. Cedrola (Eds.), Fashion Branding and Communication Core Strategies of European Luxury Brands (1st ed., p. 188). Palgrave MacMillan US.

Masè, S. and Silchenko, K. (2017). The Prada Trend: Brand Building at the Intersection of Design, Art, Technology, and Retail Experience. In B. Jin and E. Cedrola (Eds.), Fashion Branding and Communication. Core Strategies of European Luxury Brands, pp. 155–184. Palgrave MacMillan US.

Michaud, Y. (2017). La beauté partout, l’esthétisation du monde. [Beauty everywhere, aestheticization of the world]. Beaux Arts, Dossier n° 400, octobre 2017.

Naukkarinen, O. and Yuriko S. (2015). Introduction. Contemporary Aesthetics, (4), pp 1–

5. Accessed 09/01/2018.

http://www.contempaesthetics.org/newvolume/pages/article.php?articleID=635 Pappalardo, D. (2014). Gioni: Ecco la mia nuova Biennale. Repubblica.it. Accessed

02/08/2015

www.repubblica.it/cultura/2014/11/30/news/gioni_ecco_la_mia_nuova_biennale-101811389).

Riot, E., Chamaret, C. and Rigaud, E. (2013). Murakami On the Bag: Louis Vuitton's Decommoditization Strategy. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 41(11/12) : 919–939.

Rolex. 2017. “Rolex Mentor and Protegé”. Accessed 10/12/2017. http://www.rolexmentorprotege.com/

Schroeder, J. E. (2005). The artist and the brand. European Journal of Marketing 39 (11/12): 1291-1305.

Scrivener, S.A.R. and Zheng, S. (2014). Projective Artistic Design Making and Thinking: the Artification of Design. Contemporary Aesthetics, Special Volume, no.4 : 1– 13.

Shapiro, R. and Heinich, N. (2012). When is Artification? Contemporary Aesthetics,

Special Volume, no.4. Accessed 09/01/2018.

http://www.contempaesthetics.org/newvolume/pages/article.php?articleID=639 Thompson, B. J. (2005). Sponsorship as a Form of Fundraising in the Arts: A Bilateral

Perspective Involving Relationship Marketing 3(1): 1–16.

Vigneron, F. and Johnson, L.W. (2004). Measuring perceptions of brand luxury. Journal of Brand Management 11: 484–506.

Weber, M. (1947). The Theory of Social and Economic Organization. New York: Free Press

Weidemann, K.-P. and Henningss, N. (2013). Luxury Marketing a Challenge for Theory and Practice. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

Fig. 1 – Model of artification for luxury brands

Source: elaborated upon by authors

Object-based Artification

I. Mythologizing the creative director of the brand II. Collaborating with artists from the creation of the

collections to communication activities

III. Turning business outlets into exhibition spaces to display products

IV. Creating company museums to exhibit products V. Exhibiting products in art display spaces, museums

and art galleries

Luxury Art

s I. Supporting arts heritage programs through

sponsorships and philanthropic activities

II. Supporting and promoting artists, facilitating buyers-and-artists meetings

III. Supporting art through the creation of corporate foundations

IV. Exhibiting art in business retail spacesBrand-based Artification Brand-based Artification