POLITECNICO DI MILANO

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENGINEERING AND

MANAGEMENT

BUSINESS PROCESS MANAGEMENT

AND ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE RE-‐DESIGN:

“VILLA AURORA” CASE STUDY

SUPERVISIOR: GRADUATED:

PROF.SSA LUISA GARAVAGLIA FRANCESCO GALLIGARI

A.Y. 2014/2015

Index:

1. Introduction

……….……….4

2. Business Processes

………...………...…..5

2.1 Introduction to BPR: an Historical Perspective……….….5

2.2 Process Architecture and Organizational Alignment…17

2.3 Process Management………31

2.4 Measurement of Process Management………..49

2.5 Shaping Processes………..68

3. Organizational Structure Re-‐Design

……….…………...…82

3.1 Organizations and Organizational Effectiveness….……82

3.2 Challenges of Organizational Design………...102

3.3 Authority and Control………...…120

3.4 Specialization and Coordination……….133

4. Villa Aurora Case Study

………..……….…154

4.1 Company Presentation……….154

4.1.1 Historical Review………....154

4.1.2 Description and Organization………...….156

4.1.3 External Scenario………...160

4.1.4 Market Analysis………...163

4.2 Analysis of the Processes (As is)……….165

4.2.1 Porter Value Chain……….165

4.2.2 Map of the Main Processes………...166

4.3 Key Performance Indicators………...………..171

4.3.1 Identification of KPIs………171

4.3.2 Example……….173

4.3.3 Resilience Evaluation………...…176

4.4 Critical Points……….178

4.5 Solutions (To be)………..180

4.5.1 New Organization Chart………...…180

4.5.2 New Processes………...…181

4.5.3 Re-‐Design with ICT……….182

4.5.4 Management Reaction………....184

5. Conclusions

………...186

6. Bibliography

………...……….190

1. Introduction

The structure of the thesis is divided in three parts:

1. a theoretical analysis of the Business Process Management and Re-design, which constitutes the core of the theoretical section of the present study;

2. a summary of the state of the art knowledge on the organizational structure and design;

2. Business Processes

2.1 Introduction to BPR: an historical perspective

This study will be dealing with a main research question: how to use BPM to transform an enterprise in a process orientation.

The corporate business process change initiatives are a natural approach for a manager aiming to produce more in quality and quantity with less in time and resources.

Process improvement has been a concern for people since the beginning of human mankind history on earth. According to archaeologists, even dealing with ancient times manufacturing, it is possible to get a classification of techniques and processes adopted in pottery making. Potters improved their ability in order to create better products while saving time and resources. In more recent times, the industrial revolution of the late 18th century was an occasion to pay great attention to the improvement of production processes in order to obtain better products but making them faster and cheaper.

A special mention has to be given to the founder of the Ford Motor Company and sponsor of the assembly line technique of mass production. Henry Ford was born in 1863 and he created a new manufacturing process, revolutionizing not only the automobiles market in the United States but also the way millions of American people lived.

The famous “Model T” was introduced on October, 1908: the car was simple to drive and easy and cheap to repair.

In 1911, another American, Frederick Winslow Taylor, published a seminal book: “Principles of Scientific Management”. Taylor was a mechanical engineer and one of the first managements consultants. In his famous book, he started by quoting the President of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt, stating that: “The conservation of our national resources is only preliminary

to the larger question of efficiency”. The main issue of is thesis was that to produce efficiency, one should focus on creating a good training system. Good systems could then develop first-class men. He argued for simplification and for systematic experimentation to identify the best ways of performing a task and to control, evaluate and reward the output.

The remedy to inefficiency is the systematic management rather than the search of some extraordinary or particularly gifted man.

Taylor pointed out that his principles could be applied to the managing of any social enterprise, including churches, institutions, foundations and government but he also warned about implementation of single parts of scientific management without granting the whole philosophy.

Due to his contributions, Taylor is universally regarded as the father of the operations research.

The Business Process Modelling (BPM hereafter) dates back to 1967 and was created after a famous paper written by S. Williams in his “Business Process Modelling Improves Administrative Control”.

More than a decade later, the acronym: BPM began to be too loosely used by economy experts, giving it multiple meanings and with the subsequent lack of a widely accepted definition.

Among recent developments in management theory, it can be noteworthy to cite both the organizations as systems and the idea of a value chain.

Organizations as Systems and value chain

The growing focus on systems in recent years derived from many different areas: from computer science to control systems, from biology to social sciences. This approach emphasizes the connections among business and everything else, so the representation throw diagrams or flows and feedback loops can be very useful. The idea that a business can be treated as a system is so natural that it could somehow look as a commonplace, yet it remains also a

bit abstract if we don't give some practical applications.

Figure 1: Porter's value chain

A big effort in making comprehensive business processes so popular has been done by Michael Porter in his 1985 best-seller, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance.

In this book, Porter defines the concept of value chain, representing a set of all the activities that are performed to design, produce, market, deliver and support a product line (figure 1).

We can imagine that on the lower left of the above diagram, a customer orders a product, while on the right side, the product is finally delivered to the costumer. The value chain describes what happens in between.

Every function involved in the production process, as well as all the support services needed to make the process work, have to be included in the value chain. Only in doing so, the firm is able to understand how much does the product cost and what is the margin when the final outcome is delivered and sold to the market.

When the value chain concept is applied to a business process, a different type of diagram is produced, which represents the organizational chart needed to satisfy the costumer.

These type of diagrams have been realized by Geary Rummler in 1984: the making of the process flow, as illustrated in figure 2, is the result of thinking the organization you are analysing as a black box and identify the outputs (tangible products and services).

• Identify the customers for those products and services.

• Identify the inputs (resources, information and upstream products and services) that the organization processes into valued outputs.

• Identify who provides those inputs (internal organizations and external suppliers).

• Identify the internal units, department and groups and the internal workflow.

Rummler was a very well known managements systems theorist, with a background in business management and behavioural psychology. Hand his colleagues developed a new discipline, Human Performance Technology (HPT).

Human performance technology (HPT), also known as human performance improvement (HPI), is a field of study related to process improvement methodologies such as lean management, Six Sigma, lean Six Sigma, organization development, motivation, instructional technology, human factors, learning, performance support systems, knowledge management, and training. It is focused on improving performance at the societal, organizational, process, and individual performer levels.

In the book: “Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space on the Organization Chart”, Rummler and Brache described the organizations as systems and provided a detailed methodology on how to analyse processes in order to redesign and improve them, how to design jobs, how to solve inefficiency problems. They found that one of the major problems between departments was when one department gave some task to another department to complete.

The only way to overcome this drawback was, according to the managements systems theorists, to conceptualize and manage processes as wholes.

The Rummler – Brache methodology became the most widely used, systematic business process methodology of the mid nineties, thanks to the creation of a diagram showing how everything in a process is related to everything else. They defined three levels of performance: an organization level, a process level, a job or performer level.

Figure 3: Rummler and Brache performance matrix

As shown in fig. 3, Rummler and Brache obtained a matrix by crossing their three levels with three different perspectives, namely goals and measures, design and implementation and management. It identifies nine different concerns that anybody interested in changing processes in an organization should consider. It describes all of the fields that a mature organization should master.

Before the work on systems done by Rummler and Brache, managers were focused on dividing processes into specific activities that were assigned to specific departments. Each department developed its own procedures to address the tasks that were given to it. In such a way, often departments were so targeted in accomplishing their own assignment that they lost the vision of the whole project and had no regard for the overall process.

The emphasis on the value chain in the 1980s and the emphasis on business process engineering and improving of the 1990s was a revolt against excessive departmentalism and a statement of the necessity for activities to work together in order to achieve organizational goals.

Business Process Change was the interaction between the Rummler and Brache approach and the quality control movement.

In this framework, we should cite the so-called “six sigma” movement, whose name is related to the incredible aim of providing an extremely high quality in goods delivered by the production process: the manufacturing operations were statistically expected to be free of defects at a six sigma level!

Six Sigma began to spread from Motorola and General Electric (GE) and then to other manufacturing companies. Those organizations not only were using six sigma tools but embraced a culture devoted to the training of employees to support process change.

Using the same words as the GE company to describe what this movement is, Six Sigma is a highly disciplined process that helps us focus on developing and delivering near-perfect products and services.

To sum up all the different but, for some reasons, convergent, approaches described so far, we can say that Business Process re-engineering theorists urged companies to define all of their major processes and then focus on the processes that offered the most return on improvements efforts. By focusing on everything involved in a process, they were also more likely to identify ways to significantly improve their overall process.

There were also some drawbacks sometimes, as pointed out by Michael Martin Hammer: in most cases, the departmental function were not redesigned but simply automated, like “paving over cow paths”. The implementations realized in a department could even cause problems of many kinds, including delays and malfunctions, in another department. For instance, a sales campaign could result in a huge number of orders, that the production department was not able to provide in time, or a re-design of the production process affected the products in such a way that the sales department had difficulties in selling them.

So, in addition to total process re-engineering, processes should be integrated in new ways, even with the use of new technology, and re-designed ground up. Even if the action could be painful, the reward was, according to Martin Hammer, a huge improvement.

The best re-design strategy, according to Hammer, Davenport and Champy, was twofold. On one hand, processes needed to be conceptualized as complete, comprehensive entities, starting from the initial order and ending with the delivery of the product. Second, Information Technology (IT) had to be used to integrate these comprehensive processes and automating them whenever possible.

The realization of the Business Process Re-engineering should, in a first phase, exclude IT professionals and include managers and workers who would have to implement the redesigned process. Only after the redesign team had decided how to change the entire process, according to Hammer, IT people should be involved to advise the team on the systems aspect of the proposed changes.

Some of the BPR projects undertaken in the early 1990s were successful, some other failed, producing disillusionment towards this technique: among the reasons of the latter, BPR often consists in deep and extensive changes, which in some cases could not be successfully implemented in several companies, with the technologies and manpower available.

During the early 1990s, BPR has been sometimes misused, and it came out in a downsizing of the staff in response of the slowdown in the business cycle, not because of the re-engineering process itself: so, it ended up to become very unpopular among workers. For this reason, the business process project were renamed “BP redesign” or “BP improvement”.

There were many alternatives, offered by IT companies, which used work flow systems to address the issue of process change, usually called Enterprise

Resource Planning (ERP) systems (SAP, People Soft, Oracle, J. D. Edwards). Instead of moving documents from one employer workstation to another, the ERP systems allowed managers to designed processes that moved information and control from one software module to another.

ERP systems allowed companies to replace older software applications with new ones and organizing these ones in the framework of a business process. The strategy was perfect for processes that were well understood and common within companies. Thus, accounting, inventory and human resource processes were all popular targets for ERP systems.

The ERP approach was very different from BPR: all these systems were narrowly focused and relied heavily on IT people to be put in place. They provided small scale improvements rather then radical redesign.

Anyway, some processes could be easily automated with the existing technology, some others had to rely on people rather then on software but between these two classes, there were also business process changes so complex and important that they required to create tailored software to capture unique company competencies. Thus, the effective communication language shared by the business process teams and the IT teams became a crucial issue.

In the 1990s, a young fellow working in Geneva for CERN, solved the problem of integrating employees, suppliers and customers in a powerful, unprecedented, yet easy way: creating the Internet web facility.

The potentiality of this invention is well known to everybody: it gave the opportunity to even the tiniest company to access a powerful device of communication and process managing to a very low fee (the cost of a PC and a common phone line).

Of course, there have been also problems: few for all, we should mention the dot com bubble and the subsequent failure of many companies that were born in the internet euphoria era, or the resources diverted to solve the Y2K bug.

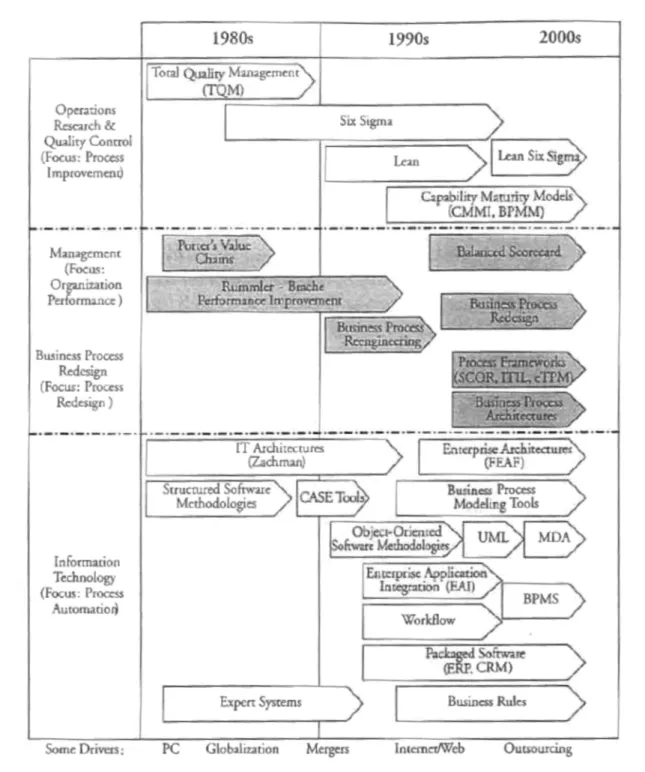

Figure 4: the business process management movement (Harmon).

technologies that were described so far, in a diachronic evolution through decades. Those technologies have been tentatively grouped in three traditions, which are not completely independent but look like fully interlaced. For instance, even if IT is highly focused on process automation, it has to do with organization performance and management and with process improvement too, and so on and so forth.

At the beginning of the new millennium, nothing or very little of the events people were so scared about happened: the Y2K bug was by far less serious and problematic than expected and the dot com bubble did not burst in such a catastrophic way as forecast. So, by the year 2002, the sense of relentless change had resurfaced.

Many new instruments had been provided by IT during the nineties, that could be used to successfully manage a company. By combining work-flow systems, software applications integrations systems and internet technologies, a new software came to light, the Business Process Management System (BPMS). In the year 2003, many vendors rushed to create a BPMS, with all the features made available by the new achievements in technology.

Aim of this new method was making managers able to control processes in some way which was very close to real-time.

The great excitement about BPMS went on until at least the year 2010 and was not only related to software development but to the advancement of all the single aspects of business process.

This renewed interest in business processes architecture, improvements and redesign produced more than 100 books on the subject in few years.

The drivers of business process change are, in some sense, perennial: when

processes to become more efficient. When the situation is good and there is a lot of money around, companies seek better processes to compete with other firms, both inside the country and abroad. Also mergers created the need to reassemble business processes inside the new company, as a result of the combination of the two sets of precedent processes.

The spread of PC use among people and the large diffusion of internet among customers was a real challenge for firms, that had to redesign their structures and compete with industries which were even far away. Everybody can now buy products directly from other countries and compare them to the locally produced ones.

Another practice intended to reduce costs and enhance productivity was the practice of outsourcing the manufacturing process by traditional industries, which focused their activities in sticking close to the costumer, in designing new products, in innovating and selling while the delivering process was in the hands of worldwide specialized companies.

Nowadays, the competition has become relentless: large companies are

organizing themselves to do business on a worldwide scale. It is easy to argue that some of them will win the competition, some other will loose. The

difference is done by constant innovation and constant increase in

productivity, both of which require an intense focus on how the work is done, id est, on business processes.

2.2 Process Architecture and Organizational Alignment

"Everything should begin with a corporate strategy," according to Harmon. Since Michael Porter’s work on value chains, "strategy depends on processes, how processes interact with each other, how process performance is measured, and a deep understanding of how processes interface with customers. Thus, organizations are engaged in defining enterprise level tools that will provide the structure and the data needed to make important day-to-day decisions and to support key initiatives like the entry into new markets, mergers, acquisitions, or outsourcing. As we have already suggested, a business process enterprise methodology simply provides a systematic way to achieve that goal."

Both the BP Trends methodology and the IBM Actionable Architecture stress the importance of a holistic, process perspective as opposed to a more traditional, functional silo perspective. Harmon advocates that managers "need to think in terms of organizational systems and value chains rather than thinking primarily in terms of divisions, departments, or their own functional unit." This systems perspective lies at the heart of enterprise architectures and "emphasizes process and connections, and ultimately adaptation." He further states that "Process thinking is just a subset of systems thinking. Systems thinking puts the emphasis on understanding the organization as a whole. Process thinking stresses thinking about a portion of the system that produces a specific set of results."

Lastly, Harmon reminds us that "Departments don't produce profits; value chains and processes produce profits." Through the deployment of a business process architecture methodology such as BPTrends or IBM's

Actionable Business Architecture, managers can effectively embrace a holistic, systems perspective toward integrating processes, strategy and information technology leading to greater customer satisfaction and greater stakeholder value.

Figure 5: BP Trends enterprise methodology.

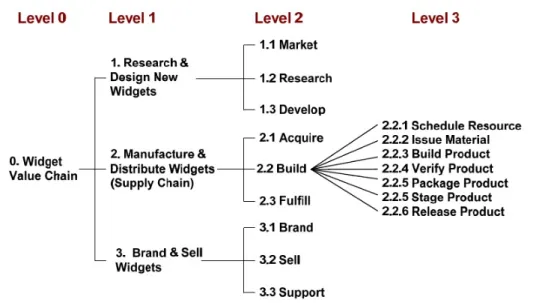

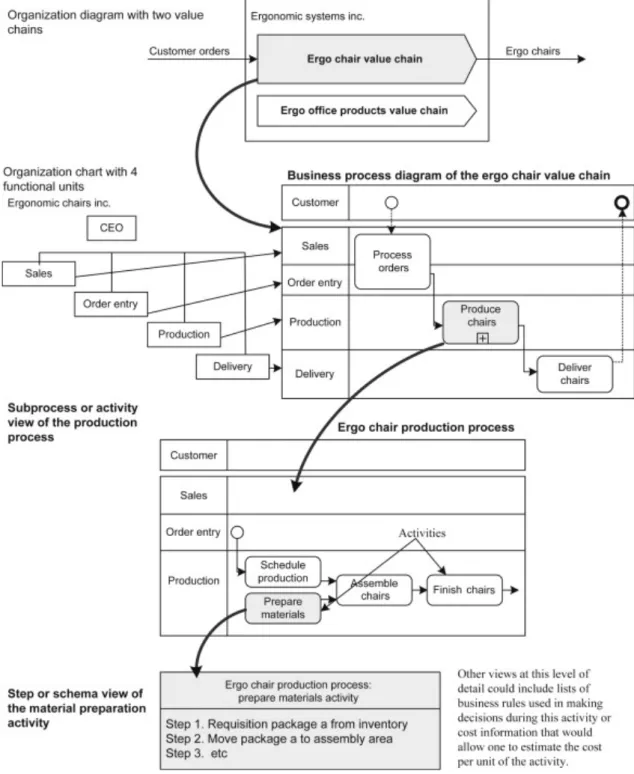

BPTrends enterprise methodology focuses on creating a business process architecture for the organization, which means creating a separate enterprise architecture for each value chain, which is the largest process we normally talk about and begins when the company decides to create a new product or service or when the customer orders a product, and ends when the task or product is successfully delivered.

That business process architecture we are talking about, comprises a value chain and in organized by a hierarchical decomposition of the processes in which the value chain is usually termed the zero level process. The major operational processes are usually Design New Products, Sell Products to Customers, Supply Chain: any of the Level 1 processes processes can be divided into several Level 2 processes, as shown in figure 6. It is evident how

each process can be considered both making part of a super-process and divided in many other sub-processes.

It is of crucial importance, when you are going to analyze a project, whether you are going to consider a large process, like a supply chain, or a medium sized process, like applying for a loan, or a small process, like obtaining a credit card approval.

Figure 6: a hierarchical decomposition of a value chain.

The business process architecture can be created on paper, but any company can implement it in different ways: if it is large enough, it may be willing to use software systems to create and maintain an adequate architecture.

• Identify a specific value chain;

• Describe the specific strategic goal the value chain has to achieve;

• Determine your evaluation criteria of the achievements of the value chain;

• Use a hierarchical approach to divide the value chain in processes and related sub-processes;

• Use some software, a worksheet or something else, for each level 1, 2,... of the hierarchical decomposition, determining how the process will be measured and who is going to be responsible for that process.

There are many ways of realizing a comprehensive decomposition of a value chain, one of them requires to start with a room full of senior executives and ask them: how do we get this product delivered? Generally, a lot of work is required before the implementation of the value chain be effective, without redundancy or confusion in processes, but that work is going to highly remunerate, because the focusing on the entire value chain allows to be competitive and to better organize the enterprise.

Figure 7: Harmon’s organization diagram.

Sometimes, it is often more practical to use a horizontal decomposition of processes, particularly in case of a large number of sub-processes, like in figure 8.

Figure 8: process decomposition diagram for VRM.

When Michael Porter defined the value chain, he distinguished between core and support processes. Core processes are

direct generators of products and services, while support processes do not produce value but are necessary to assure the functionality of the core processes. In a manufacturing firm, accounting is a support process that enables managers and stakeholders to control the value chain of

the company. Also IT is a support process, generating and maintaining the software needed for manufacturing.

Today it is popular to make the distinction between support and management processes: the latter are intended to plan, organize, communicate,

monitor and control the activities of the enterprise organization.

In figure 9 we have a clear distinction among the three types of processes: the core set creates the product and delivers it to the customer, while separately the support process resupplies a core assembly process and the management process determines which supplier is more affordable.

Figure 9: Core, Management and Support processes.

The question arrives naturally: how to include these enabling processes in our business process architecture in a way which is both formally adequate and efficient?

If we consider, to make an example, the IT service, we realize that it is related to all processes and takes part to almost each step of the value chain: thus, it looks like and independent department rather than a single process.

An increasingly popular approach is to treat IT as an independent organization, a cost centre, an independent value chain. IT thus becomes a sort of separate company.

recruitment or accounting: as a consequence, all enabling processes will be taken away from the business process architecture worksheets, leaving only the core value chains while all major support processes will have an independent architecture.

As concerns the managing processes, we must distinguish between two kinds of activities: the first is a day-to-day managing function, the second is a general managing function.

Regarding the first one, it consists of an hour-by-hour monitoring of the core processes: the manager signs contracts to supply the assembly chain, controls the work done by employees and evaluates it, whether it is outstanding or unacceptable, taking the necessary measures. This process happens to be so closely associated with core processes that they don't need an independent representation.

Regarding the second one, performing enterprise planning, organizing, communication and monitoring functions, independently of specific operational processes, we can consider it as a “management value chain”, documented with its own worksheets.

Figure 10: Level 1 architecture analysis worksheet.

As processes are identified, the group has to determine who is responsible for managing the process. Some companies are functionally oriented and do not clearly define any manager for the Level 1 processes.

measurement and evaluation criteria.

As shown in figure 10, the last column of the worksheet asks the architecture team to list resources that are required to support each Level 1 process.

This final step is not often decided during the creation of the process architecture but becomes clear in a second time: as processes are redesigned, information about ERP support is added to the architecture database.

Enterprise resource planning (ERP) is business management software— typically a suite of integrated applications—that a company can use to collect, store, manage and interpret data from many business activities, including:

• Product planning, cost;

• Manufacturing or service delivery; • Marketing and sales;

• Inventory management; • Shipping and payment.

ERP provides an integrated view of core business processes, often in real-time, using common databases maintained by a database management system. ERP systems track business resources—cash, raw materials, production capacity—and the status of business commitments: orders, purchase orders, and payroll. The applications that make up the system share data across the various processes (manufacturing, purchasing, sales, accounting, etc.) that provide the data.

Defining a business process architecture

The business process architecture is the result of the decomposition of a value chain into processes and sub-processes. The process analysis is supported by the use of process frameworks, which will now be studied in more detail. Business process framework represents the individual guidelines, policies, and procedures a company implements to enhance and improve its overall business operations.

The supply-chain operations reference-model (SCOR) is a process reference model for supply chain management. This reference model enables users to address, improve, and communicate supply chain management practices within and between all interested parties in the extended enterprise.

The supply-chain operations reference-model is developed in 1996 by the management consulting firm PRTM, now part of PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (PwC) and AMR Research, now part of Gartner, and endorsed by the Supply-Chain Council (SCC), now part of APICS, as the cross-industry de facto standard strategy, performance management, and process improvement diagnostic tool for supply chain management.

The Supply Chain Council (SCC) speaks of SCOR as articulated in three levels: Level 1 is the supply chain (the value chain remains Level 0), Level 2 consists of the high level processes that make up a supply chain: Source, Make, Deliver and Return. The decomposition of these levels results in a set of Level 3 sub-processes, as shown in figure 11. Level 4 activities are not specified in this frame and left to individual companies.

Figure 11: the three levels of a SCOR architecture.

Using SCOR, a company can easily characterize its supply chain architecture. The SCC provides members with a reference manual defining every supply chain process and sub-process. The same manual describes performance measures which are appropriate to each process at each level.

In figure 12 an instance of SCORcard is illustrated: it shows the performance attributes, a set of historical data and the benchmark data. In the right-hand column there are guessed estimates about what kind of value can be achieved, if the supply chain process is moved closer to the average for that type of industry. This card is then useful to determine if re-design or improvement in the actual supply chain is worth the investment.

Figure 12: a SCORcard with actual and benchmark data and some guesses about the level that might be achieved by supply chain re-design.

Once a company has a complete overview of all its processes, comprehensive of Levels 1, 2 and eventually 3, together with solid performance data, it is able to realize how each of the processes is performing, make an adequate comparison with the correct benchmarks and decide which possible intervention would produce the most effective results. Thus, it becomes clear how architecture can become a tool of management.

In September 2001 a great merger in the IT world was announced between HP and Compaq. Both were very active in selling PC and laptops, while HP had a wider experience in other products, like printers, and was a leader in integration services and outsourcing. The two firms didn't have the right dimension to compete with giants like IBM for the largest service and outsourcing contracts, while the merger could grant access to those contracts. Moreover, since there was considerable overlap in the PC area, the two companies hoped to squeeze out some 2.5 billion dollars in annual savings and at the same time create a leaner, more aggressive and effective organization.

The proposed merger was controversial from the beginning, many observers saw more risks than opportunity in such a decision, including several HP stakeholders.

Notwithstanding all the doubt, the merger went smoother than forecast and resulted in greater savings than those who planned it had hoped for.

The reason for this success has to be looked for, according to the players, in the great planning work that was previously done. The merger organization included about 1000 employees taken from both HP and Compaq, put in a sort of clear room, far away from their every day activity, provided with adequate information on HP and Compaq and asked to discuss and project a successful merger process.

The merger organization was headed by an executive committee that took all high level strategic decisions and approved all the report made by specialized teams. SCOR was of fundamental importance in providing a standard approach that could be used to rapidly characterize and measure the supply chain processes at both HP and Compaq. In particular, the SCOR use was crucial to identify the different features of HP and Compaq IT supply chain and determine what each process actually accomplished.

In 2003, partly because of the work he had done during the HP-Compaq merger, Joe Francis was elected chair of the SCC's board of directors.

In parallel with these development of the SCOR approach, the SCC conducted other approaches to address the same issues, like creating a new group, the Value Chain Council (VCC), who created its own model, the Value Reference Model (VRM), similar to SCOR but more integrated.

Value Chain Council is an open source provider of process reference content. VCC coordinates efforts directly with hundreds of contributing practitioners (companies and consultants) to aggregate, consolidate and disseminate best practices, tools and methods for managing business process transformations.

The TeleManagement Forum's eTOM framework

Another approach to a complete value chain framework is provided by the TeleManagement Forum, a consortium of telecom companies.

TM Forum provides information and support to help its members with creating and delivering profitable services. These include industry research and benchmarks, technology roadmaps, best-practice guidebooks, software standards and interfaces, as well as certified training, conferences and publications. The Forum also provides its member community with marketing and networking opportunities.

To develop an architecture, a team can use one process framework like SCOR, VRM, eTOM, to speed the process. The frameworks don't provide a management strategy or suggest specific alignments but provide a systematic decomposition of high level processes and suggest performance measures at each level of the architecture.

2.3 Process Management

Process Management is a disciplined approach to identify, execute, measure, monitor, and control both automated and non-automated business process to achieve consistent, targeted results aligned with an organization’s strategic goals.

So, we shall now focus on how companies organize their managers to assure that the organization's processes are accomplished.

In the last chapter, we discussed a business process architecture intended to organize the firm's information in order to, among other goals, identify the managers and the measures associated with business processes.

In this chapter, we are going to discuss management issues in a broader context, in the next one we will deal with measurement issues and so, at the end of next chapter, we'll be able to return to the worksheet compilation with management and measurement information to be recorded.

As in most companies, the architecture discussion and the management and measurement issues are considered in a separate way. It is often easier to agree on a hierarchical structure of processes and on resource alignment and then, in a second time, go on defining management and measurement responsibilities, like in the case of BPTrends Enterprise Methodology (Figure 13).

Figure 13: overview of BPTrends Enterprise methodology. We are going to start with the general issue:

What is management?

Many books and papers have been written about management but this thesis is principally focused on improving business process, so we will begin talking about roles and not about jobs or people. A person, infact, can perform different managerial roles and a single job can thus be made up of multiple roles.

Generally speaking, we can distinguish two kinds of managerial roles: operational management and project management.

Operations management refers to the administration of business practices to create the highest level of efficiency possible within an organization. Operations management is concerned with converting materials and labor into goods and services as efficiently as possible to maximize the profit of an organization.

On the other hand, a project manager is the person responsible for leading a project from its inception to execution. This includes planning, execution and managing the people, resources and scope of the project. Project managers must have the discipline to create clear and attainable objectives and to see them through to successful completion. The project manager has full responsibility and authority to complete the assigned project.

A project manager's position may end with the completion of the assigned project, or it may be a semi-permanent position for a limited time or until a predetermined point in the project’s schedule or stage of completion.

In the rest of this chapter, we will focus on operational management: a project manager role will be considered when dealing with a business process chance project.

Operational management can be subdivided in many ways, one of them is to distinguish those managers who are responsible for functional units and the managers directing a process, because they are responsible, for instance, of the production of a specific object or service.

Functional or unit managers

The great majority of companies are organized in functional units but the tiniest ones tend to be structured into departments, while the largest ones divide their functional units in divisions and then subdivide divisions into departments.

Even the definition of a division varies from case to case: sometimes it refers to a specific product line or service line, while in other cases it is simply related to a geographical area and may represent part of a greater process or even of multiple processes which can be as large as the entire company.

In figure 14 a typical organization chart for a mid-size company is shown. The managers reporting to the CEO are not only divisional managers (SVP: Senior Vice President, Widget division) but also departmental managers – CFO (Chief Financial Officer) and CIO (Chief Information Officer).

The organization chart shown in figure 14 has the aim to illustrate which managers are responsible for what function and to indicate relationships. It is clear, for instance, that the Widget Manager of Production has to report to the VP of Widget Manufacturing.

Figure 14: typical organization chart for a mid-size company.

A probable consequence of this is that the VP of Widget Manufacturing sets the Manager of Production salary, in conjunction with the Human Resources, evaluates the manager's performance and is the ultimate authority of policies and decisions on Widget production.

In most companies, mid-level managers have two different roles and work both as functional managers and process managers.

Figure 15: functional managers who are also process managers.

In figure 15, a value chain is made up of Sales, Manufacturing and Delivery processes. Each process is managed by a person working within a functional unit and reporting to the head of the unit.

It then happens that the same manager, the delivery supervisor for instance, is both the functional and the process manager of the Widget Delivery process.

This very common situation can produce problems when the head of different units refuse to collaborate with each other, defending their own territory. If a problem arises, let's say, with a delay in the manufacturing process, it is more common that the supervisor of the delivery process reports to the VP than that he tries to cooperate with the supervisor of the manufacturing process. The ideal situation would then be that the VP of the three processes meet frequently to solve common problems but it is more frequent something else:

that the VP of delivery is also VP of delivery in many other value chains and is much more concerned with delivery issues than he is with Widget process issues.

The worst case scenario which this organization could develop is that every inefficiency produces a “political” fight among VP with very little consideration for the practical problems.

Of course, this does not mean that the functional approach is invalid: it has indeed lots of valuable aspects to consider. When a manager is hired to fulfil a junior position in a department – say Sales – he then spends some twenty years in the same department, developing a wide proficiency and becoming particularly valuable for that position. He masters the details and best practice of sales by the time he is appointed VP. This type of specialization is then a very precious feature of the functional approach.

Process managers

In figure 15 we can see what a process manager task is: to supervise the Sales, for instance, one has to be responsible of the day-to-day functioning of the process. While at lower level, the process and functional roles are often indistinguishable, at higher level it becomes impossible for the same person to wear two different hats.

The project manager is responsible for what happens when the process is executed. He has also the task to maintain relations with suppliers, customers and support processes to assure the managed process has everything it needs to produce the product or the service it is intended to produce.

When focusing on organization charts or managerial responsibilities, you are considering the role you are trying to define and you try to figure out who is going to report to who, without taking into consideration the specific individual who is going to perform that role. On the other hand, when you focus on the competencies that a process manager should have to accomplish

his tasks, you are focusing on the managerial processes that successful people are requested to master.

In figure 17, the process management box of figure 16 is expanded and the typical managerial processes are inserted. We divided the process in four different sub - processes: Planning, Organizing, Communicating and Controling.

Figure 17: overview of the generic process management.

The arrows are used to describe some of the main relations between the main processes and the elements of the process that is being managed.

Generally, a process manager is usually asked to manage an already existing process, so he or she does not need to build all the process from scratch but has inherited, with the organized process, a quality and output measurement system. The smart new manager will have to re-examine every aspect to assure that every part is functioning smoothly and generates the expected outcomes and after that, should evaluate if there is room for improvement. Once the process is set, the manager will have to dedicate his or her activity to monitor and control, performing all those tasks which are due on a day-by-day, weekly or monthly basis. Beyond this, there are even more duties that need to be accomplished if necessary, like hiring a new employee or firing an

incompetent one.

Process manager at the enterprise level have to work in order to assure that each value chain is functioning well and gives the desired outputs. While a functional manager has the task of making all the processes in his or her department work as efficiently as possible, a process manager is more focused on having all processes of the value chain working well together, in a constructive and coordinated way, even if he or she has to tolerate that a single process in a functional area has to function in a suboptimal way to assure the best result of the value chain.

To make an example, let's consider the following case: to keep the inventory costs low, it is important to minimize the inventory, and that's what an inventory manager should do. But with such a choice, it is more probable that customers be disappointed when looking for specific items they won't find. Thus, the process manager has to accept a kind of trade-off between inventory efficiency and customer satisfaction and in most cases, this compromise will involve sub-optimizing some departmental process to make others perform as desired.

There is then a natural conflict between a process manager and a functional manager which is going to make life very hard to the individual who tries to perform both roles.

Figure 18: the different concerns of functional and process managers.

In figure 18 a simple organization is shown: there are only two value chains, one dealing with Widgets, the other dealing with a different type of products, the Smidgets.

The head of the sales department is totally concerned with the optimization of sales, and hires and trains salespeople according to sales criteria. He or she does not make any difference between selling Widgets or Smidgets, the only wanted result is making the selling process as efficient as possible.

On the other hand, the VP of the Widget processes wants to coordinate every par of the Widget value chain in the smartest way, being primarily concerned with the Widget sale and service processes in order to provide value to the Widget customer.

He or she would be happy to re-design the sales process function in order to provide better service to the Widget customer.

To combine the strength of the two approaches described so far, especially at the top of the organization, we need a:

Matrix Management

The top position in a process hierarchy is a manager responsible for the entire value chain. The value chain manager can have other process managers reporting to him or her, depending on the complexity of the organization. The approach results in a matrix organization like the one pictured in figure 19.

Figure 19: a matrix organization with independent senior functional and process managers.

The company pictured in figure 19 has the same three functional units as the firm pictured in other figures of this chapter. The main difference is that another senior manager has been added and he or she is responsible for the success of the Widget value chain.

to the VP of sales, who is responsible for paying, evaluating and promoting him or her, but is also a member of the Widget value chain management team. This is not the only possible choice: there are companies giving to the Widget value chain manager a responsibility greater than a simple advisory capacity. In that case, using the same example as before, the Sales Supervisor might report to both the Widget manager and the VP of sales, with each of them contributing to the sale's supervisor evaluation and bonuses.

Figure 20: Organizational Structure Influence on Project Management Execution. In figure 20 a diagram developed by the Project Management Institute (PMI) is shown. The pictured continuum is intended to contrast organizations that rely exclusively on functional structures and those that emphasize projects.

The type of matrix that an organization adopts depends on the authority and the resources that the senior management allocates to specific managers. The matrix is weak if functional managers actually “own” the employees, having full control over budgets and incentives. In this situation, the project manager becomes a team leader that can try to solve problems by means of persuasion only.

It can also happen that the project manager “owns” the employees.

have a budget and can evaluate the employees, assigning raises and bonuses. If the enterprise is structured in a more complex way, for instance by outsourcing, there might be the need of a more robust process management. Value chain and process standardization

For a company, the identification of standard processes can be a valuable goal. If a firm is doing the same activity in many different locations, it is useful to consider doing it the same way.

For instance, take the case of credit card reader software. If a packaged software (ERP) is used, then a standardization process gives the opportunity to have all employees trained in the same way and interchangeable, simplifying reporting requirements. It is even easier to update the software, when needed. On the other side, a tailored software for the credit card reader, different for each location, results in greater expenses, less agility (employees need to be trained again each time they are moved from one place to another), more complex reporting requirements.

Thus, many large companies have launched programs intended to standardize processes throughout their organization. This standardization process consists in formulation, publication, and implementation of guidelines, rules, and specifications for common and repeated use, aimed at achieving optimum degree of order or uniformity in a given context, discipline, or field.

Companies structure the effort of standardization by establishing a process management organizational structure.

They create a matrix organization and assign each manager the task of looking across the departments to find out which activities could be standardized. Companies with a matrix organization can standardize operating routines and procedures to make sure different departments work in a coordinated fashion. When a department interacts with several others on different levels, the work and information it receives must be in a standard format. Similarly, when it

passes on material on which it has worked, it must be sure the recipients can continue the work. Standardization allows the various departments to work as an integrated whole.

Everybody, including managers, has to focus his activity on precise goals. Manager preferably pursue those ends which are rewarded. The rewards can take many forms: from being told that you have done a good job to a significant bonus, to the promise to get promoted. The firm is well organized if the goals are stated clear and if a manager isn't given multiple, conflicting tasks. When the functioning of an enterprise is sub-optimal, it is often found that activities which are detrimental for the success of the processes are rewarded.

It is always important, when there are efficiency problems, to check for such absurd behaviour.

One should ask if the manager is doing whatever it takes to reach the stated goal or if things stay a little different. An example could be clarifying: in a call centre, the manager asked the operators to try to cross-sell hotel stays to the people who called about air flight about. The outcome was that very few hotel stays were sold.

An analysis of this failure showed that the call centre supervisor was very focused in maintaining the number of phone operators to the minimum because he was rewarded in doing so. He then asked his employees to keep the duration of the phone call as short as possible by rewarding those who made more phone calls in an hour. Thus, the operators selling hotel stays were criticized because they took more time.

As a matter of fact, if we want a process to succeed, we must check that the manager goals and rewards are in line with that process.

Management Processes

Companies find increasingly efficient to analyse each manager work by relying on more generic models that help analysts identify specific management processes. Some of those models are listed and described in the following pages.

• The PMI Project Management Maturity Model. PMI distinguishes between operations management and project management (limited in time). About the latter, the organizations can use PMBOK and OPM3 to evaluate their current situation in managing projects and use a methodology to introduce more advanced project management skills. The Organizational Project Management Maturity Model or OPM3® is a globally recognized best-practice standard for assessing and developing capabilities in Portfolio Management, Program Management, and Project Management. It is published by the Project Management Institute (PMI). OPM3 provides a method for organizations to understand their Organizational Project Management processes and measure their capabilities in preparation for improvement. OPM3 then helps organizations develop the roadmap that the company will follow to improve performance. The Second Edition (2008) was recognized by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) as an American National Standard (ANSI/PMI 08-004-2008). The Third Edition was published in 2013. On the other hand, the PMBOK Guide identifies that subset of the project management body of knowledge that is generally recognized as a good practice. "Generally recognized" means the knowledge and practices described are applicable to most projects most of the time and there is a consensus about their value and usefulness. "Good practice" means there is a general agreement that the application of the knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques can enhance the chance

of success over many projects.

• The SEI's CMMI Model. The “motto” of the CMMI Institute is: Adapt. Evolve. Accelerate. Standing still is not an option. Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMI) is a process improvement training and appraisal program and service administered and marketed by Carnegie Mellon University and required by many Department of Defense and U.S. Government contracts, especially in software development. Carnegie Mellon University claims CMMI can be used to guide process improvement across a project, division, or an entire organization. CMMI defines the following maturity levels for processes: Initial, Managed, Defined, Quantitatively Managed, Optimizing.

• The SCC's SCOR Framework. This framework focuses on five areas of the supply chain: Plan (demand and supply planning and management are included in this first step. Elements include balancing resources with requirements and determining communication along the entire chain. The plan also includes determining business rules to improve and measure supply chain efficiency. These business rules span inventory, transportation, assets, and regulatory compliance, among others. The plan also aligns the supply chain plan with the financial plan of the company). Source (This step describes sourcing infrastructure and material acquisition. It describes how to manage inventory, the supplier network, supplier agreements, and supplier performance. It discusses how to handle supplier payments and when to receive, verify, and transfer product). Make (Manufacturing and production are the emphasis of this step. Is the manufacturing process make-to-order, make-to-stock, or engineer-to-order? The make step includes, production activities, packaging, staging product, and releasing. It also includes managing the production network, equipment and facilities, and transportation). Deliver (Delivery includes

order management, warehousing, and transportation. It also includes receiving orders from customers and invoicing them once product has been received. This step involves management of finished inventories, assets, transportation, product life cycles, and importing and exporting requirements). Return. (Companies must be prepared to handle the return of containers, packaging, or defective product. The return involves the management of business rules, return inventory, assets, transportation, and regulatory requirements).

The SCOR process can go into many levels of process detail to help a company analyse its supply chain. It gives companies an idea of how advanced its supply chain is. The process helps companies understand how the 5 steps repeat over and over again between suppliers, the company, and customers. Each step is a link in the supply chain that is critical in getting a product successfully along each level. The SCOR model has proven to benefit companies that use it to identify supply chain problems. The model enables full leverage of capital investment, creation of a supply chain road map, alignment of business functions, and an average of two to six times return on investment, according to Scott Hudson, SCRC.

It is not always necessary to document management process in the formal business process architecture.

The Level 1 Architecture Analysis worksheet provides a space at the top for the name of the manager of the value chain (sort of Level 0 process). Then, you have to identify the managers for each Level 1 process and do the same thing for each of the Level 2 processes that make up each Level 1 process, and so on and so forth. Statistically, there is no problem in compiling the worksheet up to Level 3: the problem arises when trying to identify the managers responsible for the value chain and the Level 1 processes. While functional or unit managers are usually easy to identify, it is the process

manager whose tasks go beyond the traditional boundaries that is harder to identify. They are the managers who are really concerned with the value chain 's external managers and on customer's satisfaction. Most companies are only beginning to realize the need of having process managers at the higher level of their organization, but it is at this level that these individuals can grant a huge competitive advantage to the whole enterprise.

2.4 Measurement of process management

In this chapter we will deal with measuring process performance. Process performance measurement tools and techniques applied to enterprise environments are essential for enterprise continuous improvement. It is the reason why the next generation of process management leads to Process Performance Management or Corporate Performance Management. The phrase Corporate Performance Management (CPM) was coined by Gartner Group to describe the combination of process, methodologies, metrics and technologies to measure, monitor and manage the performance of the business. The often citied phrase: “If I can not measure it, I cannot manage it” can be motivation of this chapter.

Figure 21: Process Performance Metrics.

It is widely accepted that companies that can monitor and evaluate performances of their markets and their processes are able to perform better than others.

This is one of the main reasons why firms are usually going to spend large amounts of money to monitor performances.

Yet, there is not a peaceful agreement on what the term “performance” means when applied to an enterprise: infact, there is an historical divide. Executive managers are usually concerned in financial reports and in trends of company stocks in the exchange market. Functional managers, on the other hand, even in they agree in principle on the usefulness of the above described indicators, are not often in agreement on the practical solutions to make things work better, being mainly concerned with the optimal functioning of the department they are responsible for.

The figure of the functional manager is particularly valuable inside an enterprise but, as we found in previous chapters, when we look at the entire value chain processes as an integrated whole, we usually are in a better position to figure out which are the changes in the work that could result in an increase or decrease in costs and sales.

The performance measurement system of an organisation is a mechanism to manage and control the organisation. Maintaining the effectiveness of the organisation and the measurement systems requires a systematic review process. The process of reviewing performance is a complex task that spans the whole organisation. A good review process seeks the correct balance between organisational benefits and the effort required. Thus, it is particularly suitable to make use of KPIs.

KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) evaluate the success of an organization or of a particular activity in which it engages. Often success is simply the repeated, periodic achievement of some levels of operational goal (e.g. zero defects, 10/10 customer satisfaction, etc.), and sometimes success is defined in terms of making progress toward strategic goals. Accordingly, choosing the right KPIs relies upon a good understanding of what is important to the organization.[3] “What is important” often depends on the department measuring the performance – id est, the KPIs useful to finance will really differ from the KPIs assigned to sales. Since there is a need to understand

well what is important, various techniques to assess the present state of the business, and its key activities, are associated with the selection of performance indicators. These assessments often lead to the identification of potential improvements, so performance indicators are routinely associated with “performance improvement” initiatives. A very common way to choose KPIs is to apply a management framework such as the balanced scorecard, which will be analysed in the following of this chapter.

Measures and KPIs

Companies often define their general strategies and then they compile a more detailed document explaining those strategies. Afterwards, they have to decline each specific strategy into some specific, measurable goals, which describe practical things the firm has to do in order to realize its strategy. To make an example, we can consider a strategy of searching for a market growth of the firm. One of the specific goals can be to increase the Widget sales of a 15% in a specific time.

To achieve the stated goal, many steps have to be made: the manufacture has to increase at the same rate as the sales are planned to increase, the supply chain has to be procured parts to assemble the Widget in a convenient way. It may also happen that the inventory should temporarily be enhanced. Thus, even this simple strategic goal, like increasing the Widget sales, can be not so easy to translate into functional goals. If it happens that somebody fixes the goal of reducing prices and to do so, the inventory is cut to save many, or if a manager decides to realize a 10% reduction in manufacturing costs and so the production department is no more able to procure the right, enhanced number of Widget for the sales, then the sales goal cannot be caught.

Most organizations define strategic goals and then produce functional goals accordingly, using the experience that different departments have acquired in years of performance. They can usually rely on a proven set of measures to

make functional units do their job.

The experience allows companies to discriminate, among all measures, the Key Performance Indicators (KPI).

It is critical to be aware that the company will get what has been decided to measure: the executive managers fix several measures, with the associated specific functional goals, usually numbers. Every manager and employee knows those numbers and tries to focus on them in order to get a good evaluation. If the measures have been chosen with unintended side effects, the outcome for the enterprise would be a poor performance.

Thus, it is necessary to dedicate all the time required to get good measures and aligned corporate goals.

Figure 22: a continuum is pictured that emphasizes that these terms range from the very specific to statements that are vague and generic.

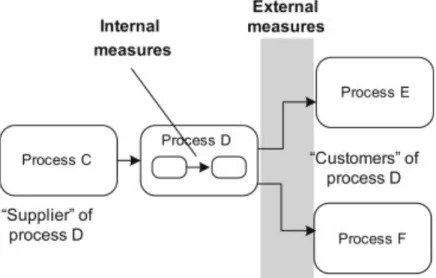

A first distinction has to be made between internal measures and external ones. The latter refer to the output of a process or a value chain, while the first ones are related to sub-processes or processes lying inside he value chain.