UNIVERSITÀPOLITECNICA DELLEMARCHE

SCUOLA DIDOTTORATO DIRICERCA INSCIENZE DELL’INGEGNERIA CURRICULUM ININGEGNERIACIVILE, EDILE EARCHITETTURA

Are the Urban Parks becoming

Cyberparks? The Developing of

Public Open Spaces: ICT tools to

support the landscape planning

process.

Ph.D. Dissertation of:

Anna Khromova

Advisor:

Prof. Eva Savina Malinverni

Coadvisor:

Prof. Antonello Alici

Curriculum Supervisor:

Prof. Stefano Lenci

UNIVERSITÀPOLITECNICA DELLEMARCHE

SCUOLA DIDOTTORATO DIRICERCA INSCIENZE DELL’INGEGNERIA CURRICULUM ININGEGNERIACIVILE, EDILE EARCHITETTURA

Are the Urban Parks becoming

Cyberparks? The Developing of

Public Open Spaces: ICT tools to

support the landscape planning

process.

Ph.D. Dissertation of:

Anna Khromova

Advisor:

Prof. Eva Savina Malinverni

Coadvisor:

Prof. Antonello Alici

Curriculum Supervisor:

Prof. Stefano Lenci

UNIVERSITÀPOLITECNICA DELLEMARCHE

SCUOLA DIDOTTORATO DIRICERCA INSCIENZE DELL’INGEGNERIA FACOLTÁ DIINGEGNERIA

We’re called to be architects of the future, not its victims.

This thesis is dedicated to my father Maksim Khromov who taught me how to use rationality as the measure of things

Acknowledgments

Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my two advisors Prof. Eva Savina Malinverni and Prof. Antonello Alici for the continuous support of my Ph.D study and related research, for their patience, motivation, and immense knowl-edge. Secondly, it must be underlined that this work couldn’t be completed without the help and the precise guidelines of my colleague and friend Roberto Pierdicca.

On the same line, my sincere thanks also go to Prof. Vera Frolova, Prof. Aleksandr Dobrokhotov, Prof. Vladimir Falco, Prof. Gabriele Filippini, Dr. Olga Moskvina and Prof. Fausto Pugnaloni for their essential indications in the first steps of my aca-demic path that played a crucial role in the choice of my research topic.

Besides my advisor, I would like to thank all the members of the CyberParks project, expecially Prof. Carlos Smaniotto Costa, Prof. Montserrat Pallares Barbera and Dr. Therese Kenna for their insightful comments and encouragement, but also for the possibility of having real cases of study, which incented my research in various ways.

My sincere thanks also go to Dr. Alfonso Bahillo, Dr. Eneko Osaba Icedo and Dr. Rafael Vicente Salar, who provided me an opportunity to join their team as intern, and who made possible to establish a fruitful collaboration. Without they precious support it would not be possible to conduct this research.

I am also grateful to my mother Irina, who have provided me through moral and emotional support in my life by inspiriting and believing in me and to my other family members who have supported me along the way.

Last but not the least, a special thanks goes tom Matteo Stocchi for his support and enormous help, to my dearest friends Daria Timofeeva, Vladimir Bojkovic and Davide Bevilacqua for their friendship, believing and positivity and to everyone not mentioned here that contributed to this work.

Ancona, November 2017

Abstract

Nowadays, given the growing complexity of the city systems, the quality of human life depends considerably on the quality of the urban environment. One of the core components of the cities are the Public Open Spaces (POS), that should be more accessible to all on equal terms, by creating a synergistic balance between grey, green and social components. Technology can play a pivotal role for this am-bitious task, since it already generates interest and attraction for many people in their everyday life. However, even if there are relevant cases where the adoption of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) made the use ofPOSmore

smart, the recognition of possible interrelation and added values is still not very

elaborated so far. There is thus the need to upgradePOSs to the quality of

Cy-berspaces, defining them as particular outdoor places where the use ofICTcreates a synergy between humans and the environment. This is the logical step forward of the progress that we can see in our every day life, since these new technologies have a twofold contribution: in one hand, they provide users with new instruments to enhance their experience of visiting and discovering a place. On the other, they represent a valuable source of information that should be used for the planning process. Hence, this innovation can bring landscape planners to take into account new forms of interactions, generating an endless process where the user become himself the planner. The reason of this relies on one fundamental thing that must be underlined: the modern technology used in the method we will propose cre-ates synergy between the two categories of users and planners, joining them in a unique entity and so allowing the users to be involved in the planning process (which is one of the Cyberpark concepts). In this light, there is the need to under-stand what can be the real contribution of theICTs in the planning process, and this will be achieved by performing a comparison between an approach that in-cludes them and an approach, that we can define as a classic one, which doesn’t. In addition,also the way users experience the space will be taken into account. The innovation is offered by the possibility to collect a great amount of data in the same period of time and in a smarter way: the citizens are involved in the urban planning project by the mean of a mobile application, in which they can give real-time feed-backs to the planners. What is relevant for the planners is to analyse the human spatial behaviour, which is essential for a good understanding of multiple aspects (political, economic, tourist, social and cultural) of a modern city.

thesis deals with the study, analysis and development of Cyberspaces by starting from a theoretical point of view for then passing to its direct implementation, also highlighting the enhancement that a Cyberpark concept can bring to the mankind. From a theoretical perspective, the work performed was to study the historical evo-lution from smart cities to senseable ones, having the aim of understanding the dynamics that made possible the upgrade from a classical to a Cyber model of city planning process. Such effort was necessary in order to understand how the given models can be applied to the real urban environment we’re called to deal, i.e. what are the (theoretical) tools we can use to correctly interpret it.

Afterwards, different cases of study have been implemented in real urban scenar-ios by adoptingICTsolutions able to provide information to the users and, at the same time, to collect user’s information to be analysed from the planners. Espe-cially, three main cases were of particular importance in our research, each one having a specific purpose but all aimed to a common one: the understanding of howICTtools can upgrade aPOSto the dimension of a Cyberspace. Going into de-tail, the first case of study was the implementation of an Augmented Reality (AR) experience to make users more aware of their surroundings. The second one was aimed at comparing classical approaches of analysing human spatial behaviours to an innovative data collection platform aimed to the same task. The third and last dealt with the implementation of a complete mobile based architecture in the context of a urban park, able to provide contextual information to the users and, at the same time, to collect their data. The outcome of this last case of study was then analysed and visualized by means of a dedicated Geographic Information Sys-tem (GIS), which proved to be the most valuable solution at the disposal of land-scape architect to enhance the design process of aPOS. The research is backed by the framework of CyberParks project - Fostering knowledge about the relationship

between Information and Communication Technologies and Public Spaces, a

multi-disciplinary European COST action that, among others, discusses variousICTtools and presents a methodology that can be adopted for the future development of cy-berspaces, useful for both planners and users. The main contribution and novelties of this research thesis can be in conclusion summarised in the following items: i) outlining a step forwards in the research domain of smart cities; ii) renovating the landscape design process by adopting the theoretical approach called the scientific rationalities; iii) the definition of a well established pipeline of work, applied in real case studies and iv) the analysis, by using innovative tools, of the human spatial behaviour according to the landscape perspective, based on real data. With the proposed approach, we make a step forward, making the planning process based on users’ needs: "Through smartphones the cities are now burgeoning and unfold-ing inside every pocket. Every citizen has a tool in which to perceive and process the city peering through his digital lens is an intensely personal experience." [1]

Acronyms

AR Augmented Reality BCI Brain Computer Interface BLE Bluethoot Low Energy

ICT Information and Communication Technologies GIS Geographic Information System

GNSS Global Navigation Satellite System GPS Global Positioning System

LBS Location-Based Services MAC Media Access Control MAR Mobile Augmented Reality NUI Natural User Interface POS Public Open Spaces POI Point of Interest

PUI Perceptual User Interface TUI Tangible User Interface UAV Unmanned Aerial Vehicle UGD User Generated Data VUI Voice User Interface QGIS Quantum GIS

Contents

1 Introduction 1

1.1 The concept of Cyberspace: the landscape planners’ perspective . . . 2

1.2 Thesis outline and main contributions . . . 3

2 State of art 11 2.1 The evolution of city planning process . . . 11

2.2 Building the concept of the Cyberspace . . . 15

2.3 Cyber as a new property of the Public Open Spaces . . . 21

2.4 Beyond interaction: user interface design. . . 23

3 Planning Cyberspaces: a theoretical perspective 27 3.1 CyberPark COST action: operational framework . . . 27

3.2 Theoretical interpretation of a Cyberpark. . . 28

3.3 Instruments for planning a Cyberpark. . . 33

3.4 The main drivers in Public Open Space Planning: Users and Planners 36 4 Study cases and applications 43 4.1 Integration of an augmented reality module within the Way-Cyberparks App in La Valletta, Malta . . . 44

4.1.1 Scenario . . . 46

4.1.2 Implementation. . . 47

4.1.3 Results . . . 49

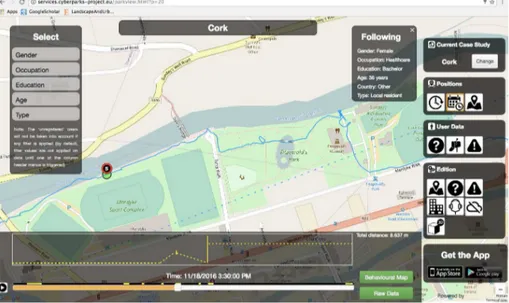

4.2 The comparison between Cognitive Mapping approach and Way-Cyberparks App in Cork, Ireland . . . 52

4.2.1 Scenario . . . 54

4.2.2 Implementation. . . 56

4.2.3 Results . . . 62

4.3 The planning and development of CyberCardeto app for improving the user’s experience in urban park in Ancona, Italy. . . 64

4.3.1 Scenario . . . 65

4.3.2 Implementation. . . 69

4.3.3 Results . . . 73

5 Discussion and Conclusion 87 5.0.1 Theoretical Novelties. . . 87

Contents

List of Figures

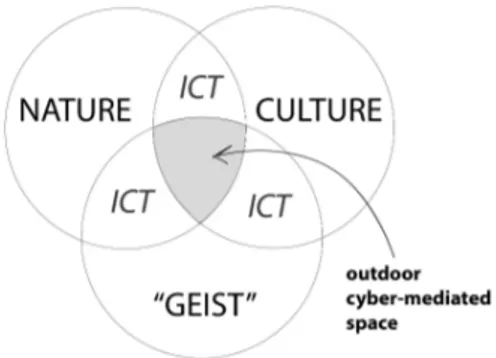

3.1 The complex system and ICT as a way of interaction among

compo-nents . . . 28

3.2 The main components of the system and their relationships with a smart environment . . . 34

3.3 The main components of the system and their relation with a smart environment. . . 39

4.1 The web services . . . 49

4.2 The insertion of Point of Interest (POI) into the web service . . . 50

4.3 Upper Barrakka and Senglea Point, POI of the application . . . 50

4.4 The mobile application running in outdoor scenario to test its func-tionalities. . . 51

4.5 The botanic garden of Argotti Villa and its POI . . . 51

4.6 The mobile tested by the users in the real environment. . . 52

4.7 Mardyke Master plan of the Fitzgerald park. . . 53

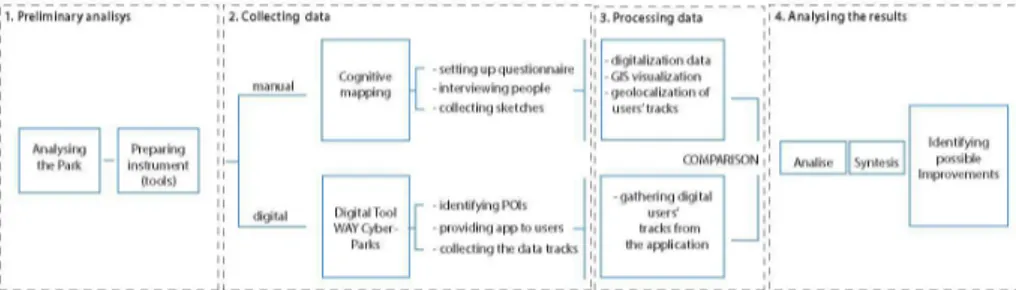

4.8 Schematic view of the process used in the mission . . . 54

4.9 The questionnaire used for interviewing the visitors of the park. . . . 55

4.10 Examples of maps sketched by the visitors of the park . . . 56

4.11 The study of the park performed by means of the EthnoAlly digital tool 57 4.12 Implementation of the POI and of some questions to be submit to the visitors of the park . . . 58

4.13 The information paper . . . 59

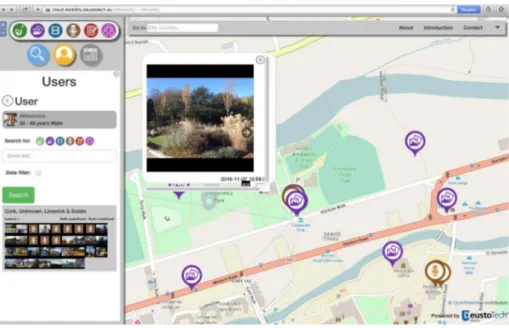

4.14 The map from the platform of Digital Tool Way CyberParks . . . 60

4.15 Overlap of all the user’s tracks and their visualization having as a back-ground the orthoimage of the park. . . 61

4.16 The table containing all the user’s answers . . . 61

4.17 Tracks in the GIS environment . . . 62

4.18 Example of one of the tracks highlighted with the related attributes on the raw of the table . . . 63

4.19 General overview of Cardeto Parl; upper image depicts the satellite view, lower image represents the typical skyline of the park. . . 66

4.20 The schematic view of the park with sections: History, Culture, Nature 67 4.21 The preliminary concept of the application. . . 68

4.22 The preliminary concept of the application.) . . . 69

4.23 Distribution of the POIs and Beacons over the park.. . . 70

4.24 Set of three Estimote long-range location beacons. . . 71

List of Figures

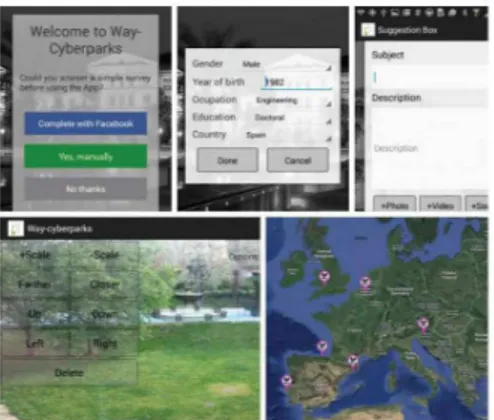

4.26 Screenshots of the app running. From left to right: the home page of the app, the menu that the user can choose among different cate-gories, the textual information about a sample POI, the POIs alerted once the user get within the beacon range and the map visualization. 81 4.27 Format of the XLSX file form what concerns the data received from

the Global Positioning System (GPS) service . . . 81 4.28 Format of the XLSX file form what concerns the data received from

the Beacons . . . 81 4.29 Geolocalization of the data coming from the GPS data files . . . 82 4.30 Examples of incorrect geolocalized position (a) and imprecision in the

connection of the various dots composing the polyline (b). . . 82 4.31 The buffer analysis shows the average time spent by the visitors near

each Beacon . . . 82 4.32 The creating of the grid (10x10 m) over the evaluation area . . . 83 4.33 The graduated scale composed by 15 colours . . . 83 4.34 The overlapping of the Beacons and of the POI locations on the

or-thopoto map of the Cardeto park. . . 84 4.35 Schematic representation of the developed visualization process. . . 85

List of Tables

Chapter 1

Introduction

Today, according to the latests surveys, more than half of world’s population lives in urban areas. The quality of human life thus depends considerably on the quality of the urban environment, includingPOSaccessible to all on equal terms. For their spatial quality the right balance between grey, green, social and other components is needed. To achieve this really very complex task technology is already one of key-tools for support, as well as a strong interest and attraction for many people in their everyday life; given the above-mentioned considerations, is a Cyberpark really something completely new? The term Cyberpark refers to outdoor public places, where the use ofICTcreates a synergy between the humans and the environment. It’s a logical continuum of the progress that we can see every day.ICThelps us in business, at home and almost in every aspect of our life. Public Open Spaces may include high streets, street markets, community gardens, parks, playgrounds: each one plays a pivotal role in the social, cultural and economic life of communities. Even if there are relevant cases where the adoption ofICTmade the use of Public Open Spaces more smart [2], the recognition of possible interrelation and added values is still not very elaborated. It is important to understand the whole range of possibilities offered by analysing the public involvement processes of planning and design. In a city there are less and less untouched spaces, so we need to focus on the improvement of existingPOSto be more usable and attractive to more people. ICTcan upgrade public open spaces to the quality of Cyberpark spaces, since their contribution is twofold: on the one hand, they provide users with new instruments to enhance their experience of visiting and discovering a place. On the other, they represent a valuable source of information that should be used for the planning process. It is important to understand that,ICTare not just an add-on to place, but also represent a boost for planners during the design process. It is very useful to includeICTfrom the beginning when analysing the urban territory, in order to help keeping and collecting data. UsingICTprovides new possibilities for planners and landscape architects. Monitoring and tracking the so-called User Generated Data (UGD) represent the future pathway for observing, recording, and analysing the dynamics of our environments (i.e. cities,POS, rural areas, etc.) and, more in general, the behaviour of people who live these spaces. For that, a big challenge

Chapter 1 Introduction

is a using of mobile devices, which are already significantly changing the way that people interact with their surroundings; they are able to sense the environment and the user’s location and constantly improving such capabilities. This combination is playing a pivotal role in the mainstream of data collection. In the following, these relations are discussed, by highlighting the enhancement that a Cyberpark model can bring to the entire community.

1.1 The concept of Cyberspace: the landscape

planners’ perspective

The topic under investigation is the upgrade of thePOSfrom their classic structure to an innovative Cyber one (in agreement to the concept of Smart city [3,4,5,6].

One of the crucial questions in the field of Landscape Architecture is how to develop and unlock the hidden potentials of the green places under analysis. Its answer can represent a milestone in order to fully understand the role ofICTin the planning process.

ThePOS, being a fundamental part of the urban structure, have multiple func-tions. The one that is interesting from the planner’s point of view is the social one, i.e. the one that treats the sharing and the exchanging of information between the users of the place. In a Cyber space, the means through which such information travels are theICT, that can be defined as a driving force operating as a mediator between users, digital information and real spaces. Additionally, as it will be made clearer later in the following chapters, in the Cyber model the information is also allowed to flow in both the directions, i.e. from the planners to the users and, re-versely, from the users to the planners. This means that, in the upgradedPOS, the interaction between all the components of the system is more flexible, with a strong synergetic characteristic. This recirculation of information is basically the reason whyICTcan serve useful guidelines to the planners. For the sake of clearness, it is useful to discern the involved subjects in two categories: the planners and the users of thePOS, as explained in what follows.

According to the nature of the research topic here treated, the academic relevance is more well explained in terms of the planner’s prospective. The reason of this relies on one fundamental thing that must be underlined: the modern technology used in the proposed method creates a synergy between the two categories, joining them in a unique entity and so allowing the users to be involved in the planning process (which is one of the Cyberpark concepts).

The innovation of the method we propose can be highlighted by the mean of a simple comparison to the classical one, both considering the planning process and the way users experience the space. For example, according to the classical method, the analysis of the human behaviour in thePOSpasses from making questions to

1.2 Thesis outline and main contributions

the citizens, which of course is limited in terms of time and number of considered people. In the other hand, the innovation in the use ofICTis that it offers the possi-bility to collect much more data in the same amount of time and in a smarter way: the citizens are involved in the urban planning project by the mean of a mobile ap-plication, in which they can give real-time feedbacks to the planners. In conclusion, what is relevant for the planners is to analyse the human spatial behaviour, which is essential for a good understanding of multiple aspects (political, economic, tourist, social and cultural) of a modern city. This analysis is truly important in order to im-prove the quality of the human life in the city [7].

Passing to the user’s point of view, there’s the need to underline what’s relevant in their opinion, i.e. what the Cyber space can give to them. First, an upgraded POSgives a new experience to the visitors: the process of discovering of all the attractions is made more interactive, and this helps unlocking the hidden potential of the space. APOSserved byICTalso improves activities not directly related to the exploring process such as playing (whose one example is given by the Playable city project [8]) and studying. In addition, such system also makes possible for the users to give feedbacks about the space they have visited, that will be useful for both other visitors, that may be interested in experiencing the same, and for planners, as we said above. More generally, the transformation of aPOSto a Cyber space helps, by providing facilities and functionalities, to improve the quality of life of the ones that will take advantage of it.

1.2 Thesis outline and main contributions

In what follows, a complete overview of the various sections of the present work will be given.

• In the first paragraphs of the State of Art chapter, a digression about what the history of city development has been, i.e. how cities come to be what they are today, will be given. Although our focus is on thePOS, the latter clearly belong to the reality of the city, so in order to understand how to make its upgrading from a classical to a Cyber model possible, it is necessary to analyse how the same concepts have been applied to the cities. Three differ-ent historical periods will be taken in exam: the pre-industrial, the industrial and the post-industrial ones. By doing this, we can understand how the de-veloping of any technology can strongly influence the shape of the city and so the city design planning. This is clear especially in the industrial revolu-tion, where big changes in the transportations and the productions of goods had led to equally big changes in the way a city must be designed. Then, to talk about management of growth, we must discuss the concept of how the cities turned out, and how they have formed up to this time and what are

Chapter 1 Introduction

the ideas that have shaped them, i.e. the different styles of the city’s plan-ning process. Switching to the various concepts of city design, especially two of them will be taken into consideration according to their relevancy in re-spect to the Cyber one: the smart and the self-organizing city concepts. Such concepts about how a futuristic city can be, complete our vision of the de-veloping of the city itself during the time, i.e. from the classical one to the Cyber one. Focusing on the latter, its main aspects and implications will be analysed, resumed and inserted in the context of our case of interest. Consid-ering the above-described whole set of classical models of the city system, we can easily identify a constant in their schemas, something that never changed among all the considered historical periods: for building social connections, the citizens had to meet each other in a specific physical place. Nowadays, the situation has drastically changed since virtual interactions have become the predominant reality [9], and people, more and more often, chose such a way to connect one another [10]. So, since the need of using a physical place for meeting is disappearing, the number of visitors of a generalPOShas con-siderably decreased, leading to a loss of one of the essential components of this context: the human factor. From the planner’s point of view this is ob-viously a problem, which leads to the question: how to attract back people to thePOS? How to transform, modify or enhance the potential of the public urban areas so that they can properly fit in our modern society? The answer, which will be unfolded in what follows, is part of the problem itself: the idea is to integrate the ICT, mainly in terms of mobile applications, to the POS, making so them what we call a Cyberspace.

The best way to see the benefits and the differences between the classical and the just introduced Cyber concepts is to make a comparison on a given example taken from our daily life. Considering such an articulated system as the public transportation one, we focus on the simple situation in which a bus is arriving at its stop according to its timetable. Infinite unexpected events may happen: the bus crushes, the interested path is way too busy, ex-treme weather conditions affect the ride or, simply, there’s a change in the bus usual track. Obviously, all the just reported eventualities are unpleas-ant from the user point of view. The Cyber model approach can drastically improve the functionality of the situation, giving to the user all the needed information at real time and so to use it consciously to take decisions. For example, he can take another path to reach the desired destination, or even comes to change his plans [11]. As it can be clearly notice, the classical model focuses completely on the structure of the system: the timetable, the tracks, the roads and all the variety of static components, ending up with having any flexibility. Passing indeed to the Cyber model, the attention is translated to the user needs. The system now has a dynamical component which provides

1.2 Thesis outline and main contributions

suitable scenarios and real-time information to face all the unplanned events by creating multiple possibilities for the user.

Another example is represented by the project Treepedia [12], which aims to increase the numbers of the tree in the city to increase the quality of the life. By augmenting a city’s tree canopy, this project contributes to lower the urban temperatures by blocking short-wave radiation and increasing water evaporation. Creating more comfortable micro-climates, trees also mitigate air pollution caused by everyday urban activities. Treepedia basically mea-sures the canopy cover in cities. Rather than count the individual number of trees, the project implements a scalable and universally applicable method for analysing the amount of green perceived while walking down the street. On the same line of the just given examples, the section Senseablility as a new

property of thePOSprovides multiple scenarios in which the latest technolog-ical founds have already been integrated in thePOS.

Lastly, though the final predicted scenario of our research provides a vision of a futuristic city in which the needs of having interfaces to connect the real from the digital world is lost, we’re still making the first steps toward such reality, so an overview of the basic concepts of interactions and of the various kinds of interfaces will be given.

All of this constitutes the background in which the CyberParks project is de-fined, which aims to "Fostering knowledge about the relationship between ICTand Public Spaces supported by strategies to improve their use and at-tractiveness" [13].

• The core of the third chapter relies on the investigation of the fundamental question: how to develop and unlock the hidden potential ofPOS? Urban environment is a hyper-complex system with different components such as buildings, memorial monuments, trees, roads, infrastructure networks and, above all, people. This system, according to Dobrohoto [14], can be devised into three main components: Nature, Culture and Geist. Dobrohoto under-stands them, respectively, as the environment without or with low human interferences, all fruits of human activity and, essentially, the human creative source.

Planners have an impulse for creating and this impulse has a rational char-acter. The Russian philosopher Stepin [15] studied the problems of method-ology of science and philosophy of culture. He developed the idea of types of scientific rationality: classic, non-classic and post-non-classic [15]. Stepin’s classification is not directly linked with urban/landscape planners, but we will see how its vision may be beneficial in such field. The classic type of rationality is very direct and based on understanding systems as simply

me-Chapter 1 Introduction

chanical ones (designed like formal gardens in the 19th century). Secondly, the post classical type perceives the object more like an organism. The plan-ner is still isolated from the system but the dialog and interaction is to be used in the planning process (system approach in design, sustainable planning, etc.). The third type is the human dimension point of view - where consider-ing the possibility of the planner to be involved in to the system and creatconsider-ing a synergetic perception (cyberspaces, Futurecraft method, etc.) is the core point. The planner is a part of the system itself and he modifies and upgrades himself whilst the system became to be more compound. More as a new self-developing system. These types are characterized by a special classification of ideals and standards for researching the systems. Particularly, the level of reflection on the interaction expands the development of all the new types of system objects. Following Stepin’s ideas of rationality, planners, as a possibil-ity to use their new skills, should consider passing through all three types of the classification. The historical order of these types of rationality have grown over time from simple systems (classic) to more complicated ones, such a complex self-organizing system (post non- classic).

POSwithICT, as stated before, is an example of complex self-organizing sys-tem. The planners have taken in account interaction among components of our system (planners, decision makers, users, spaces, cultural identity, etc.). Conversely, adopting the synergetic approach [16], planners aim to promote synergy between them, giving only the direction of a possible way of de-velopment of the system and so considering themselves as one of its com-ponents. This classification perfectly fits with landscape architect’s objects, which might look like three different scenarios of relation between planner and the system (POS). The nowadays methods of design, more commonly, follow the so-called non-classical approach. Planners aim to create a har-mony with the nature, considering the needs of all components of the system. The way of interaction in non-classical model between planner and users is based on dialog (feedback). During the last years, the opportunities of using public open spaces are increasing and the third way of rationality is becom-ing more popular in the research and planner’s communities. In a cyberpark, the interaction between planners and users is in the core of the attention. If the first model can run withoutICT, the second one is faster and easier with ICT, but is the post-non-classic model whereICTtakes a major role in the whole process of space design. This topic will be properly addressed in the section Analysing human spatial behaviour: methods and instruments, where not only the latest technological founds such as the digital footprints and the GISsoftware will be introduced, but also the classical method of the cognitive mapping will be explained and adapted to the case of interest.

mul-1.2 Thesis outline and main contributions

tiple meanings, making an immense contribution to the construction of im-ages and urban imaginary [17]. They are places to express cultural diversity, to relax or move, see and be seen or even be anonymous in a crowd [18]. This brings about the symbolic character public spaces can embody as rep-resentative of the collective and of sociability (rather than individuality and privacy). Considering the just described environment, in the sections that follows we will focus on two roles of our interest: the users and the planners, each one with different interests and experiences on POS and with a different way of enjoying it [19]. The key point we want to underline is the fact that users and planners are, when it comes to the Cyberspaces, the same actor but playing in different roles. Such as the planner define and so design the chosen area, with the support of the aforementioned new possibilities, also the users begin to play a role in such a creative process. On the other hand, a designer also becomes integral part of the Cyber system, making the latter, as said before, dynamical. Lastly, the connection ring between the theoretical compartment and the practical reality will be introduced in the final section of the present chapter: basing upon the various cases of study conducted in the experiences that will be described in the later chapters of this contri-bution, hints about how the theoretical approaches (widely discussed in the previously mentioned sections) have been applied will be given.

• After a first theoretical part, in which several aspects of the topic of interest have been investigated and interpreted according to a variety of visions [14, 15,16] and methods (Cognitive Mapping,GIS, Digital Footprint, etc.), in what follows such theoretical compartment will be applied to real cases of study, each one having different work plans and giving, obviously, different results that will be presented and commented.

Latest improvements on mobile devices capabilities are changing the way people interact with their surroundings. Nowadays, devices can sense the environment and user’s location, enabling the user to experience improved digital services. This is a key aspect of public spaces enhancement, which plays a pivotal role for the improvement of public spaces; a key to make pub-lic locations more accessible, interactive and enjoyable. One of the most powerful technologies enabling this innovative set of services is known as AR. More in depth, ARallows users to visualize in real time virtual infor-mation about the physical objects of the real world, directly on the display of their own devices, providing innovative way-finding widgets and context-awareness services. Along with the aims of the COST Action CyberParks, the target set is to improve the App delivered during the first stages of the project (Way-CyberParks) with AR functionalities, by developing a location-basedAR module tailored to be integrated within Way-CyberParks. The AR section will

Chapter 1 Introduction

link virtual geo-tagged annotations as an interface to (geo) spatial and at-tribute data, allowing users to quick access digital sensory inputs. The over-arching idea is to populate the App with virtual sign-age fostering the fruition of public spaces by allowing users to experience new ways of moving within specific places. Thanks to that, on one hand, the App works as an interac-tive path-finder tool, heading visitors towards the most interesting locations or landmarks within a specific area (Points of Interest orPOI). On the other, users are enabled to create their own contents and upload them into the net-work of availablePOI, enabling a true participative community. The city of Valletta (Malta) has been chosen as first case study; here theARmodule will be tested to identify historical locations and heritage buildings, acting as con-textual objects for the Way- CyberParks App.

The second section of the present chapter aims to analyse Fitzgerald Park in Cork as a potential Smart Public Open Space. For the data collection process, we propose to use a traditional method (i.e. interviewing people directly) and a digital one (using the available Digital Tool WAY CyberParks). The purpose of using two methods for collecting information from the visitors, is having the possibility to compare the results and to answer the questions: "What do people think they are doing in Public Open Spaces and what they are really doing there?" In particular, the idea is to understand how good the digital approach is for catching the individual emotion and if it is representing the insights of the people who experience a public space. This short scientific mission, which is included in the framework of the CyberParks project, took place in the Department of Geography of the University College of Cork, Ire-land. As afore-stated, this mission is a practical testing of the methodology that has been presented back in the third chapter of this contribution. This has been achieved using theICT, for data collection purposes, as a bridge that connects the previously discussed three components of the park-system: na-ture, culture and Geist. According to this approach, the data analysis repre-sents the starting point for planning Cyberspaces and to study how the plan-ner can develop and unlock the hidden potential of the spaces using bothICT (digital) and traditional (classical) methods.

ICTand mobile devices are deeply influencing all facets of life, directly affect-ing the way people experience space and time. ICT also represent tools for supporting urban development, and they are adopted also as equipment for furnishing public spaces. In this sense,ICTcreate a new paradigm of hybrid space that can be defined as Senseable Spaces. Anyway, even if there are rele-vant cases where the adoption ofICThas made the use of public open spaces more smart, the interrelation and the recognition of an added value are still not very elaborated. This fact is one of the motivations of the research pre-sented in the to insert the name of the Cardeto chapter chapter. In this way,

1.2 Thesis outline and main contributions

the main goal of the conducted work is the deployment of a complete system composed by three different connected elements (realworld infrastructure -data gathering system - -data processing and analysis platform) for the analy-sis of the human behavior in the open space of Cardeto Park, in Ancona, Italy. For this purpose, and because of the complexity of this task, several actions have been carried out: the deployment of a complete real-world infrastruc-ture in the Cardeto Park, the implementation of an ad-hoc smart-phone ap-plication for the gathering of the participant’s data, and the development of a data pre-processing and analysis system for the dealing of all the gathered data. The deep description of these three aspects and the way in which they are connected creating a unique complete system is the focus of this paper. The last section of the chapter focuses on the work that has been done during the intern-ship that took place in the Department of Geography of the Uni-versitat Autonoma de Barcelona (UAB), Spain, under the leadership of pro-fessor Montserrat Pallares-Barbera. Such a location has been selected due to its numerous studies in the field of human spatial behaviour from the geo-graphical point of view. The aim of this mission was to use theGISsoftware as an instrument for analysing, elaborating and visualizing the geolocation data collected and gathered in the ambit of the previously done project Cy-berCardeto, that took place in Ancona, Italy. This is a fundamental step to give a useful instrument to visualize the gathered data from the planner’s point of view and so to answer the declared objective of this contribution, i.e. how the planner can unlock the hidden potential of the spaces. Going into details, what there’s the need to understand is: how to attract more vis-itors to the investigated public space, how to show the actual dynamics of the visitor’s experience in the selected period, how to understand in what are the users more interested in and what is not considered by them, how good the CyberCardeto tool is for gathering this kind of data and how good theGIS works as an instrument for the visualization of the considered data.

Recapitulating, the structure of the research plan which includes and defines all the just presented missions (or chapters) can be briefly summarized as follows:

– Testing the potential of the given application Way-Cyberparks in the two

urban scenarios of botanic garden and of the city centre of Valletta (The

Way-CyberParks App integrated in the city of Valletta: a first step towards a Cyberspace),

– Widening such testing to our case of analysis, i.e. an urban park, and

comparing the efficiency of the classical and cyber methods for collect-ing data for what concern people’s experiences in the selected domain (Apply a methodology of collecting and organizing data using classical

Chapter 1 Introduction

and digital approaches),

– Designing and developing our own mobile application for then testing

it in the real case of the Cardeto park, Ancona (Designing a scenario for

the user’s spatial experience by the mean of the CyberCardeto App),

– Visualizing and evaluating the results obtained in the previous mission

Chapter 2

State of art

2.1 The evolution of city planning process

Before to answer the question What is a Cyber City we must step back and look at the fundamental question What is a city from the point of view of the planning city process. In the urban planning history, we know that the concept of city appeared to satisfy the basics human needs, as an extension of the instinct of protection. Mul-tiple secondary aspects have then been derived from the city system, such as the economical one, the political one, the cultural one and the social one. In addition, also the shape of the city has been affected by these conditions and necessities. To analyse the evolution of the city design process, we can differentiate between three historical periods: the pre-industrial [20], the industrial [21], and the post-industrial era [22].

Pre-industrial - Going back in the history, the necessity of planning a city appeared

when the latter was nothing more than a settlement, and everything was taken in an instinctive and intuitive way. Approximately 3000 years ago, the primitive con-cept of gathering all together around the main fire of the camp became building houses around a central point. As the civilization grew, the people started to collect more resources, and consequently the life became more stable. As a consequence, more rational and conscious ideas began to appear in the planning city process. Such ideas were based on the following five main vital needs:

• The wall. To ensure the survival of the citizen, the defence against any men-ace was essential, and for a long period of time (over 2000 years) the city de-sign has been strongly characterized by the fortifications. Such an instinct of protection conditioned the process of designing a city so much that, also when the necessity of protection came down, the idea of imposing limits to the extension of the urban morphology has not been washed away.

• The grid, probably the most logical way to organize a urban structure making the navigation in it easy and intuitive. Such a method was first used by the Greeks with their gridiron cities, and subsequently the grid system was also

Chapter 2 State of art

the favourite form for the new founded cities when the Europeans colonized America back in the 15t hcentury.

• The entrances and the exits. The location of the gates in the city can make some parts of it more important than the others. An example of the applica-tion of the just introduced concept is Rome in the renaissance period, where different districts of the city were created according to the classical urban morphology.

• The city square, i.e. the primitive version of thePOS. In European cities, pub-lic squares were created by thinking about them as the living room of the city. Initially used for commercial purpose (market center), the city square quickly became the main place for important social events, where all the city was called to participate. Another kind of pre-POSwere the green spaces (later become city parks), i.e. places with the aim of offering relief from the dense crowd of the city. Multiple routes were taken starting from this kind ofPOS: city gardens, sustainable and green city, etc.

• The cloister. Spaces where were created monasteries, temples and other kinds of shrines were often given central and important locations in the city. The main temples of the city were often the crucial landmark and so defined the all character of that city.

All five of these elements can be found in cities with long historical past, taking their roots from antiquity time, and of course they represented the armature, the basic structure for future design ideas. According to this fact, it’s obviously of great importance to fully understand all the previously listed milestones of the city de-sign history.

Industrial - Historical call the transformation with appearing a new technology as

Industrial Revolution and date it from the mid-1700’s. In the 17t h and 18t h

cen-tury, populations began to grow rapidly in Northern Europe, and industrialization is what supported such growing. By the turn of the 19t hcentury, such growing

in-terested almost all the aspects of the urban reality, and this is directly connected to an increase of the general wealth generated by the trading. But, as history shows, there’s still a connection to the surrounding rural areas, which were only a short walk away so that the farmer could bring his cows and sheep right into the center of this reality. The first industrial buildings were the ones used for making clothes: they were driven by water power, and so situated near waterfalls or similar places in which one can easily extract the needed energy from any moving mass of water. According to this fact, most of the cities were not taken into consideration as suit-able places for such buildings, mainly built around ports. There was then the ne-cessity to connect the newborn industrial area to the city, so in the early industrial days, networks of canals were built, which served as long-distance transportation

2.1 The evolution of city planning process

between the sources of industrial products (like the new factories upstream from the major cities) and the cities themselves. The second reason of changing for the shape of the cities was the introductions of a whole new set of rising technologies: the elevator, the mass production of steel, the ability to make large sheets of glass and so on. The just listed entries lead to the creation of tall buildings, probably the most characterizing of the new features brought by the industrial revolution to the city planning process. Also, the increase of the population influenced the city de-sign: cities had to adapt themselves in order to become more accessible, and the introduction of trains, street-cars and other kinds of transit drastically changed the urban morphology previously designed for people and horses. A secondary aspect developed from what has just been said is the establishment of close-in residential suburbs, located away from the industrial pollution of the city.

Post-industrial - During the industrial era, as aforesaid, trains and street-cars were

the most common way to move from one place to another. This strongly influ-enced the shape of the cities: the urban area used not to elongate much further in respect to the railway station, dropping off sharply starting from the latter. The new and most important feature the post-industrial era brought is the auto-mobile. Cars can basically go anywhere, and the roads are much easier to build than rail-ways. According to this, in nowadays cities the cars still play an important role in the planning process. Talking generally, most of the cities are now divided into two parts: the old city, also called down-town, and the new one. Two are the scenarios that we can find. In the first one, the original down-town is now at the periphery of the much more affluent new city, and many of the old central neighbourhoods had emptied out since people have chosen to migrate from the suburban to new city. In the other scenario, mostly founded in the developed countries, the old centres remain dominant. What we have been seeing in the last few decades is a big down-town revival and also a rise in real estate values for walkable neighbourhoods and suburbs. In the meantime, the new city did not stop growing. It keeps spreading out and becoming more and more dysfunctional and unsustainable. Another phe-nomenon of the current century is the creation of metropolis. By considering the usual scenario in which the big city is surrounded by small ones, i.e. the final results of the afore-described suburban areas, the new city areas of such adjacent cities be-gan to grow together, forming mega regions. In the United States, it is possible to identify eleven such regions such as in Europe, where the view reveals analogous patterns of city regions. Examples are given by the megalopolis of London, Paris, the whole countries of the Netherlands and Luxembourg which have effectively be-come one continuous city region and the far-east cities such as Tianjin and Tokyo. Such city-extension has no clue to stop since the planet is expected to add another three billion people by 2050. In a time when, for the first time in hundreds of mil-lions of years, the sea levels are expected to start rising rapidly. So, how we manage changes in climate and population, and at the same time correct the mistakes the

Chapter 2 State of art

world has made have become topics of crucial importance. We can see that new methods of city planning and analysing human behaviour are becoming more im-portant year by year.

For a more comprehensive understanding of the city’s planning process, the vision shared by George Kubler in his book the Shape of Time will be take into consider-ation. According to him, rather than being a progression in which you move from one style to the next, the kinds of city design can be interpreted as a series of ideas in the history of human thinking, each one prominent in different periods. Basically, the city styles can be divided into four groups [23]

• Modern city design - Having the Swiss-French architect Charles-Eduard Jeanneret-Gris (known as Le Corbuiser) as its creator, the Modern city design is based on the concept of having groups of tall, elevated buildings, each one surrounded by open space. Largely spread all over the world, the modern city design is nowadays particularly appreciated by most of the architects since the mod-ern technologies allow them to better model the reality, according to their visions.

• Traditional city design. The traditional city building that the modernists set themselves up to oppose, is still alive in some areas, despite modernism’s worldwide acceptance. Such design is characterized by long straight streets, wide and open squares and vistas. Many examples can be found in most of the European capitals such as Rome (Piazza del Popolo), Paris (Versailles), and so on. It is worth to underline that the traditional city design concepts can provide an organization for the city, while the modernist city design can-not.

• Green city design The green city design appeared as the solution to the prob-lem that the industrial cities were losing every connection to the natural envi-ronment. Such way of designing city integrate the natural landscape into the design for cities by the mean of green areas (parks and gardens). Another as-pect of the green city design is related to the climate change: the city itself has to adapt to it, and since most of the big urban areas are located in senseable places, such as coastline, there’s so the urgent need to find solutions to this problem.

• Systems city design Today’s information technology has enabled systems think-ing about cities to go in new directions. City designers are trythink-ing to under-stand the systemic basis, that causes people to live and work together in cities and the forms of accommodation that emerge from the collective effect of many individual actions. Briefly, cities are made up of systems: of taxes, of property development, of utilities and these systems can be simulated and

2.2 Building the concept of the Cyberspace

their interactions manipulated, so that they can produce either good or not so good results. One line of investigation has been to look at mathematical equations, cellular, automaton. That produce patterns, and then see if these patterns are predicted of any process can be observed in real situations. It is important to remark that the just listed ideas are not opposed to each other, i.e. they’re not mutually exclusive, rather they interplay with each other, being each one periodically more or less important (according to the period in analysis).

2.2 Building the concept of the Cyberspace

Smart city concept - In the digital era, the information can move across the space

without wires, having the media networks and the social media as two of the main examples. People have another invisible dimension for interacting one another, for searching information and playing by simply using their smart-phones (and other devices) in a wireless environment. The wireless potential is widely used in the topic that will be treated in what follows, i.e. the Smart Cities. The Smart Cities concept goes by several names including Intelligent Cities, Techno-Cities and Dig-ital Cities. While there are subtle differences between them, they all mean roughly the same. The intelligence of the cities is based on the two milestones of the techno-logical systems and of the human intelligence. There are two types of intelligence, the top-down and the bottom-up ones. In the first, the systems are created to cen-trally control cities or to respond to collective needs. Energy management systems, traffic control systems and incident management systems, for example, fall into this category. All these systems have operation centres. Such operation centres are usually integrated in the urban management infrastructure and they usually have four components: Sensors installed in the environment; Collected data; Pre-dictive models, aimed to predict what’s about to occur and so allowing the city to respond accordingly; Interfaces. Human intelligence, obviously, is also a part of the just described system that is of critical importance. The sensors are served for con-tinuously monitoring what is happening around the city, like patterns of human behaviour, traffic flows, temperatures, air quality, energy usage and dozens of other things. Obviously, at this point, making sense of the data becomes the essential task. Also human devices can work as sensors and be another valued part of the sensing system. A lot of ways of using the intelligence systems has been for mun-dane activities, like adjusting signal timing on rail roadways and to reflect real-time levels of traffic. Coupled with new road way systems, traffic flows can be diverted and real-time conditions such as heavy pedestrian flows can be figured in to the equation. Other sensors can inform the sanitation department when the garbage needs to be picked up, which optimizes the use of their vehicles. It can also be offered on-line education support, integrated systems for health and welfare. It is

Chapter 2 State of art

important to remark that for city planners can be sufficient in some cases to inte-grate intelligent systems, that make the city perform better, instead of fundamen-tally rethinking the urban design of the city. The bottom-up intelligence, reversely, is the one that begins with a crowd seeking about what kind of environment they wish and so pressing the latter to change accordingly. For example, Prodigy Net-works has initiated a crowd source planning project for Central Bogota’ called My

Ideal City [24]. This project has several components, and one of them is an interac-tive website where residents can submit their visions and ideas for then reacting on the feedbacks given by the experts of the field. Additionally, the integration of such kind of intelligence in the city and its surfaces could change the character, poten-tials and quality of life. For example, the Bjork Ingals Group (BIG) proposed to make to BMW to organize a competition with the topic city of the futures [25]. This project should explore the possibilities that driver-less cars coupled with intelligent digital pavements could open up in the next ten years. The intelligence resides both in the vehicle and in the environment through sensors and illumination. Whereupon, the smart streets allow the public spaces in the city to be safer and used during the day and the night as needs demand. Having no more fixed curves, the city becomes elastic. The automatically piloted car messages its movements ahead and these are forecast in the pavement. Around, the pedestrian creates an area of influence, i.e. a safe zone in which no car can enter. The vehicle’s route is adjusted to account for the people, and the people adjust themselves to avoid those places where the movements of the vehicles have been predicted. People can use without being in danger a space that was previously dedicated to cars, and cars can also share the space with no danger to the pedestrians. This is a true bottom-up intelligence ap-plied to the city. This new world of electronic networks is something that could not even be imagined just two decades ago. And we can only see a sketchy outline of what the future holds. The technological can leap at least in two stages. First, the new technologies can be applied to actions and needs of our everyday life without reinventing the exiting things. The world is just made more efficient. The second stage of the revolution uses the potential of the new technologies to reinvent the tasks that we’re doing. As Henry Ford used to say, "If I’d asked my costumers what they wanted, they’d have said a faster horse", that means that there are two ways for evolving, in the considered case, a vehicle: upgrading the existing one or creat-ing a new concept accordcreat-ing the users needs. Right now, we’re still in the first stage of this revolution that’s being brought by electronic networks, that in exchange of-fer the potential to design cities based on totally new concepts. So, in conclusion, to integrate intelligent systems is still not enough according to the just introduced vision, there’s also the need to rethink the planning city process by creating new concepts and methods.

2.2 Building the concept of the Cyberspace

it around wherever you wanted to? What if a computer would automatically reshuf-fle it for you, based on your personal preferences? Would that not be more desir-able and efficient than a city planned by a single designer? In the self-organizing city architects look for techniques which don’t impose a preconceived plan: in fact, is the user who makes the project with a potential designer’s participation. The city is seen as an organism. Many parts of the world do not follow any master plan. Informal settlements, for instance, follow a different logic, often character-ized by self-help dwelling construction. In recent history, designers have tried to harvest some of the self-organizing processes in the city. We can trace the con-cepts of the self-organizing city back to The Metabolists, a Japanese group of ar-chitects that fused ideas about architectural mega-structures with those of organic biological growth. They saw urbanism not as a static, but as a living process. Like a growing organism, they argued that incorporating biological processes into cities would make them more efficient, and able to structure growth. One of such exam-ples is Kisho Kurokowa’s Helix City Project [26], inspired by the recent discovery of DNA. He designed every tower as a double helix: based on demands, units would be plugged in on the top, over time, and the structure would gradually grow up-ward. Since each new unit is slightly twisted, the roof of each unit can be used as a garden, maximizing the green space within each helix. Helix City is not really a building. It is a three-dimensional artificial and growing landscape. As more hous-ing would be needed, helices could be added, growhous-ing from the water. In the face of housing shortage in post-war Japan, Helix City offered a flexible yet structured way to deal with growth. Kiyonori Kikutake envisioned a Marine City in 1958. It consisted of cylindrical cores with housing units growing from it. As the units grow older, they are to be replaced by new ones, like regenerating cells. Meanwhile, in Europe, Hungarian Yona Friedman designed what he called a spatial infrastructure [27]. That allowed for a mobile architecture, where people were free to use this im-mense space frame structural system any way they wished. They could make their own homes by filling in their own walls and floors within. It’s clear that the user plays a crucial role in the design of the spatial city. The main concept of such a kind of design process is that the user makes the project with a potential designer’s par-ticipation. The walking city project (also called the Plug In City [28]), ideated by the British group Archigram, imagine as well a type of self-organizing city. The British architect Cedric Price, rather than put restrains on the occupants of his structures, wanted to enable them with freedom. He designed Pottery Thinkbelt, a flexible and mobile university consisting of rail-mounted classrooms with fold-out desks. Com-puter modules, laboratories and inflatable lecture halls move from place to place along the recovered roadway lines. Price designed large transfer stations where enormous gantry cranes move around and assemble the modules, so they can be reconfigured as desired. He designed 19 housing complexes, using four types of prefabricated modular housing units (32,000 in total). All the units move

depend-Chapter 2 State of art

ing on the academical needs, leading to a city formed by learning rather than vice versa, so to a more optimal university configuration. In the meantime, an impor-tant new science gains prominence in the 1950s: the cybernetics, i.e. the science of communication and control. Based on the notion that a specie’s intelligence lies in its capacity to learn from feedbacks, cybernetics help machines reacting to a real-time stimulus. Such progress has led, for example, to the development of com-puters and guided nuclear missiles. If we apply cybernetics to the planning process an interesting question arises: could cities and buildings learn from how we use them? Can they auto-correct themselves into an optimal configuration or even an-ticipate future uses? Price was the first architect who applied cybernetics in his de-sign for Fun Palace [29], a laboratory of fun with facilities for dancing, music, drama and fireworks. Its form and structure resembles a large shipyard in which enclo-sures such as theatres, cinemas, restaurants, workshops and rally areas can be as-sembled, moved, re-arranged and scrapped continuously. Travelling cranes would move around walls, modules, platforms and stairs. But unlike his priors’ variable structures, Price endowed his project with intelligence: sensors relayed feedback about the use of occupants to computers, which in response would move around the modules according to the projected needs. The structure not only responded to the visitor’s needs, it would learn to predict their desires. Although Price planned Fun Palace for construction, it was never actually built. Also the computer game industry has opened up a new avenue for city design. As Jonathan Burnett showed, video games like SimCity [30] are well able to simulate the processes by which cities develop. This makes some useful hints for city design as they can be used to simu-late different possible scenarios for future development. Using computer software, we could test out the collective effect of our individual actions and see the effects of changes in policies, regulations, or habitation preferences. On this line, the Dutch design studio MVRDV has explored the use of computer generated scenario build-ing. They developed a Function Mixer [31], a computer program that empowers people in city design. This program allows people who are not designers, including municipalities and community groups, to quickly visualize different urban design scenarios. This would help facilitate discussions about possible changes in plan-ning and regulations, and so eventually come to an optimal configuration of their city before to implement it. The Function Mixer gives a very different role to the city designer. Instead of giving to the people a single design solution, the designer scripts a software tool that makes people conscience of the spatial consequences of their plans and desires.

2.2.0.0.1 The Cyber-society and the Senseable city concept - The term

2.2 Building the concept of the Cyberspace

and technology are perfectly interlaced between each other in order to pursuit the same aim. To "permit man’s existence in environments which differ radically from those provided by nature as we know it" [32] was the topic of what can be consid-ered the first cyborg project, in which the human body has totally been reconsid-ered and these new hybrid entities (i.e. the cyborgs) analysed. According to [1], "A cyborg is a hybrid capable of more than either the biological or the mechanical sys-tem alone can do, with a correspondingly expanded range of possible habitation", which actually classify the humanity itself as a cyborg species: weapons, tools and all the creations the humans have been realizing since the very beginning of their rising as a species allowed the latter to adapt to extreme environments they oth-erwise could never adapt to. In simple words, the mankind keeps on surrounding itself with technologies that support its physical survive, and this fact alone define all of us cyborgs. An exhaustive compendium on the developing and evolution of such technologies, from the very first stone utensils to the latest technological finds, have been presented by the French anthropologist Andre Leroi-Gourhan [33]. It is anyway of fundamental importance for the purposes of the present work to under-line that the nature of the developed tools and technologies have been drastically changed across the history: as Antoine Picon wrote in his contribution, "Human progress was marked by the gradual externalization of functions, from stone knives and axes that extended the capacity of the hand to the externalization of mental functions with the computer." [34]. If in the past the fruits of the human creativ-ity were conceived as an enhancing of the physical self, i.e. as tools for upgrading the capabilities of primitive characteristics as strength and speed, today they are mainly used as extensions of mind’s possibilities. Memory, identity and social func-tions are generally known as the main topics of today’s researches for what concern the evolution of the life-assisting technology. The strong difference between the nature of today’s and yesterday’s tools is remarked also by Carlo Ratti: "The cru-cial feature of the modern cyborg: digital technologies have become a dynamic extension of our bodies and minds, demanding a constant and two-way cybernetic exchange in a way that our traditional (one-way) extensions, such as clothing or axes, have never done" [1]. If to analyse carefully these last words, an additional, intriguing aspect emerges: The deep entanglement between humans and the tech-nological system. "We of the modern age are provided with two types of bodies ... the real body which is linked with the real world by means of fluids running inside, and the virtual body linked with the world by the flow of electrons" [35]. Among all, the modern device capable of forging the strongest connection between the two bodies is, undoubtedly, the smart-phone. Perfectly in-line with the afore-given def-inition of today’s tools nature, the smart-phone extends our mnemonic and logical capacities in such a deep way that the person is not considered a human any more but rather a post-human, i.e. "a new entity that is born with technology rather than acquiring it as a prosthetic ... The post-human is a creature born into this binary

Chapter 2 State of art

condition, into a world of converged digital and material, where each individual’s mental and social existence is enable, sustained and improved by technologies. Be-yond individual personal interactions, the global adoption of smart-phones -mass mobile communications - among to a collective social shift. Personal devises serve as a portal to externalized and multiply the self to conceivably infinity degree. The prosthetic smart-phone has deeply permeated society along the backbone of wire-less telecommunication, giving rise to a new networked humanism." [1]. Never-theless, the rise of the modern technologies didn’t affect just the individual: the physical space has undergone a substantial change as well, i.e. especially cities are adapting to this new cyber-reality. After all, "The figure of the cyborg is at root a spatial metaphor," notes the geographer and urbanist Matthew Gandy. Going back to the most representing digital tool of our era, "Through smartphone, the city is now burgeoning and constantly unfolding inside every pocket. Every citizen has a tool with which to perceive and process the city" [1]. Multiple implications derive from what has just been said, and probably the most important one resides on the fact that the rising digital networks should radically be integrated into the archi-tecture and the planning process of the city system, allowing them to refocus the existing technology in building a more suitable environment for the post-humans. The implementation of the cybernetic program in the context of dynamic interac-tions would transform the architecture from a static and pre-conceived structure to something that can be seen like an extension of the body, where digital tools enable the environment to respond. This way of conceiving the architecture make the lat-ter to breathe, i.e. a living entity that can also be seen as a large-scale instrument that its inhabitants, what we previously defined as cyborgs, create, plug into and in-teract whit. Buildings and spaces born from this new planning system are at once an environmental life support, a social catalyst, and a dynamic set of experience, where the same devices that interlace with the human biology here act as means in which real-time information flows. According to the vision of Mark Weiser, a Xe-rox PARC engineer who first introduced the term ubiquitous computing, in such a context screens and interfaces would find no places as the technology would be so deeply and strongly ingrained into the city, totally merging digital and physical spaces. As he says, "In this new way of thinking about computers in the world, one that takes into account the natural human environment and allows the computers themselves to vanish into the background." [36]. Ultimately, "Technology recedes into the background, and interaction is brought to the fore. Buildings and public open spaces can be simple-rather than voluptuous and shocking - but even more integrally vibrant and living" [1].