1 INDEX

Abstract……….………... 1

Introduction………. 2

Emotion Darwin studies……….. 2

Emotions after Darwin contribute: Ekman & the issues not considered by Darwin………... 7

Derealization and depersonalization………. 9

Brain imaging studies of depersonalization………... 10

Affective Temperament………... 14

Depersonalization in bipolar disorder………... 17

Methods………... 19

Participants……….. 19

Measure and Instruments (SCI-DER, TEMPS-I, POFA)……… 20

Statistical analysis……… 21

Results……….……….. 22

Characteristic of the sample……….. 22

Depesonalization and depersonalization evaluation in the sample……… 22

Affective Temperament, depersonalization and affective recognition………. 22

Discussion and conclusion……… 24

Table……….. 27

2

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The aim of our study is to evaluate, in a sample of bipolar (BD) eutimic patients, the association between depersonalization symptoms, facial emotions expression recognition and affective temperament. Method: 95 bipolar eutimic patients (YMRS< 6 and HDRS< 8), are assessed with: SCID-P, TEMPS, SCI-DER e POFA (test of recognition of facial emotions expression by Ekman e Friesen). Results: Throught a regression analysis we underline that, independently to panic disorder, the ipertimic temperament is associated with: major recognition of happiness (p< 0.001; β=-4,483) and minor recognition of anger (p=0.005; β=3,202) in BD patients with high scores in autopsychic depersonalization domain; major recognition of sadness (p=0.001; β=-3,944) and minor recognition of anger (p=0.005; β=3,181) in BD patients with high scores in affective depersonalization domain. Moreover, the cyclotimic temperament is associated with: major recognition of surprise (p=0.004; β=-3,233) and happiness (p=0.044; β=-2,124) in BD patients with high scores in Derealization (DER-TOT); major recognition of surprise (p=0.001; β=-3,792) and happiness (p=0.018; β=-2,532) in BD patients with high scores in somatopsychic depersonalization domain. Conclusion: The presence of depersonalization and derealization symptoms is associated with a selective deficit in the recognition of several emotions. In bipolar patients this selective deficit is dependent of type of affective temperament. Further research is warranted to replicate our clinical observation.

3

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 Emotions: Darwin studies

The scientific study of the facial expression of emotion began with Charles Darwin’s

The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), with an extraordinary

contributions that some emotions have a universal facial expression and cited examples and published pictures suggesting that emotions are evident in other animals, and proposed principles explaining why particular expressions occur for particular emotions—principles that, he maintained, applied to the expressions of all animals. But Darwin did not consider when, how, and why emotional expressions are reliable or misleading. In the 19-page conclusion there is only one sentence that refers to this:

“They [the movements of expression] reveal the thoughts and

intentions of others more truly than do words, which may be falsified” (p 359).

Research has documented that some facial expressions can be very confusing. In brief remarks Darwin gives a more complex view, suggesting how true feelings can be shown despite the efforts to hide emotions and also how false expressions, which display emotions not felt, may be betrayed. Several research has supported and sometimes qualified his opinions. Darwin suggested that the muscles that are difficult to voluntarily activate might escape efforts to inhibit or mask expression, revealing effectively the true feelings (emotion and sentiment). “[W]hen movements, associated through habit with certain states of the mind, are partially repressed by the will, the strictly involuntary muscles, as well as those which are least under the

4

separate control of the will, are liable still to act; and their action is often highly expressive.” The same idea in somewhat different words: “A man when moderately angry, or even when enraged, may command the movements of his body, but . . . those muscles of the face which are least obedient to the will, will sometimes alone betray a slight and passing emotion” (shares extracted from the book The Expression

of Emotions in Man and Animals of Charles Darwin, 1872).

In 1871 was published Darwin’s greatest unread book, The Descent of Man, and

Selection in Relation to Sex and in a part of this book Darwin explained the origin of

what he called sympathy (today be termed empathy, altruism, or compassion), describing how humans and other animals come to the aid of others in distress. He acknowledged and he wrote that the highest moral achievement is concern for the welfare of all living beings, human and nonhuman. It should be no surprise, given Darwin’s commitment to the continuity of species, that he would claim that concern for the welfare of others is not a uniquely human characteristic. He wrote:

5 Several years ago a keeper at the Zoological Gardens showed me

some deep and scarcely healed wounds on the nape of his own neck, inflicted on him whilst kneeling on the floor, by a fierce baboon. The little American monkey who was a warm friend of this keeper,

lived in the same compartment, and was dreadfully afraid of the great baboon. Nevertheless, as soon as he saw his friend in peril, he rushed to the rescue, and by screams and bites so distracted the baboon that the man was able to escape, after . . . running great

risk of his life.(p126)

Darwin treated the emotions as separate discrete entities, or modules, such as anger, fear, disgust, etc. The German physician Wilhelm Wundt proposed an alternative view of emotion about a decade later. Wundt wrote about variations in dimensions or continuum of pleasantness and activity or intensity, then this different conceptualization enjoyed popularity in twentieth-century psychology (in particular others like Schlosberg (1941) and adopted by Russell at the end of the last century. Many different kinds of research—neuroscience, perception and cross-cultural evidence—show that Darwin’s conceptualization of emotions as separate discrete entities is correct also varies on attributes such as intensity or acceptability, which can be considered as dimensions that describe differences within each discrete emotion. We can estimate the Darwin’s consideration of discrete emotions as the first of his lasting major contributions. Darwin described variations in related emotions, described rage, anger, indignation, defiance and hatred, but he did not conceptualize each emotion as constituting a family of related experiences, varying in social

6

context, physiology and expression, but sharing characteristics that distinguish one emotion family from another.

Another contribution of Darwin was his focus primarily on the face (although he did give some attention to vocalizations, tears and posture), to date facial expression has been found to be the richest source of information about emotions. The voice has yet to be shown to be a source for as many discrete emotional states as the face, although it is harder to fabricate or regulate than facial expressions Darwin’s third major insight was that facial expressions of emotion are universal. In the last few decades the preponderance of evidence from Western and Eastern, literate and preliterate, cultures strongly supports Darwin’s claim (based on sparse evidence, but in all likelihood demonstrated to him by his experience travelling around the world on his 5-year journey on the Beagle).

The fourth consideration was that emotions are not unique to humans, but found in many other species or animals. His examples in Expression range from bees to roosters, dogs, cats, horses as well as other primates. For much of the last century that view was considered an example of bad science, of anthropomorphism. Underlying that belief was a reification of language and verbal selfreport.

A fifth contribution was Darwin’s explanation of why particular movements signal a particular emotion. For example, why one of the anger expressions consist in the upper lip raised? Darwin described in a right way this as due to it having been a ‘serviceable habit’, exposing the canine teeth threatening harm to come as well as preparing for the attack. Stripped of its Lamarckian baggage, this explanation is

7

consistent with contemporary ethological accounts of how signals evolved from intention movements, providing the foundation for current formulations of how signals become ritualized or formalized.

But how is it possible, that Darwin was right about so many aspects of emotion and expression? One answer is that it was the product of his evolutionary perspective: a perspective that would suggest much of what he proposed when it is focused on emotion. Another related answer is that Darwin turned to the biology of emotion, noting what he could about the physiology of emotion, and (where in his time much more was known) the anatomy of facial expression. He utilized the anatomical descriptions of Sir Charles Bell, from whom he took a class during his aborted medical student days. Darwin rejected Bell’s theorizing that expressions were given by God only to man. In the margin of his copy of Bell’s book Darwin wrote, ‘he never looked at a monkey’. Darwin’s other important source was the French neurologist Duchenne De Boulogne, many of whose photographs Darwin printed, with permission, in Expression. When Darwin wrote to Duchenne asking him what he should pay for the right to reproduce some of his photographs, Duchenne wrote back that between men of science there should be no financial transactions. Amazingly Darwin’s publisher omitted three of Duchenne’s photographs that Darwin discussed at length in Expression, presumably because it was too costly to print all the images Darwin analysed. Those photographs never appeared in any subsequent edition of Expression, until the recent third edition. Another of Darwin’s

8

methodological contributions was to show photographs of facial expressions to observers and note what emotions they attributed to each expression.

1.2 Emotions after Darwin contribute: Ekman & the issues not considered by Darwin.

There are different elements for the correct emotions recognition that Darwin didn’t consider in his research and other subsequent authors (Ekman & Friesen in particular) have mentioned to better display and recognize without misleading. First, Darwin did not consider and did not attempt to provide a method for measuring facial movement, then he did not consider how to define the boundaries of each emotion family, even if there is little doubt that there are many variations on the expression of any emotion and isn’t possible have an empirical basis for knowing how many of the possible distinctions or variations merit consideration because they provide different information. We don’t know how many variations are linked to differences in social context or subjective experience. Second, Darwin didn’t consider is the distinction (Ekman & Friesen 1969) between an indicator and a communicative signal, and in particular the Duchenne’s observations about the differences between a voluntary smile and an involuntary smile of enjoyment provide an excellent illustration of the value of this distinction between indicators and signals. Infact the action of different muscle provides to different action and utility such as: zygomatic major provides a very strong signal and the absence of orbicularis oculi ‘unmasks the false friend’. The difference was between a spontaneous enjoyment signal and a voluntarily or habitually produced facsimile, is an indicator, not a signal. It is rarely recognized by

9

conspecifics. Third, Darwin’s lack of interest in how to distinguish deceptive from genuine facial expressions of emotion, (‘Darwin, Deception and Facial Expression’, Ekman 2003b): ‘They [the movements of expression] reveal the thoughts and intentions of others more truly than do words, which may be falsified’. Exactly research has documented that some facial expressions can be very misleading and Darwin suggest how true feelings may be shown despite efforts to conceal emotions (although he gives no indication that the hidden emotions can be detected in very brief expressions that Ekman called micro expressions, or mini expressions (Ekman 1985, 2009), and also how false expressions, which display emotions not felt, may be betrayed. Fourth, Darwin suggested that muscles that are difficult to voluntarily activate might escape efforts to inhibit or mask expressions, revealing true feelings. A great deal of research, described in Ekman (2003a,b), has supported this suggestion. Darwin made one more hypothesis about deception: ‘A man moderately angry, or even when enraged, may command the movements of his body, but . . . those muscles of the face which are least obedient to the will, will sometimes alone betray a slight and passing emotion’. Fifth, Darwin failed to note the existence of gestural slips (Ekman 1985, 2009), which leak concealed feelings and intentions, and other forms of body movement that can betray a lie. The conceptualization of the role of emotion in perpetrating and betraying a lie was clearly not of much interest for Darwin, being one of the very few topics he left to others to chart.

10

1.3 Derealization and depersonalization

Depersonalization (DP) is defined as an experience in which the individual feels a sense of unreality and detachment from himself/herself. There may be a sensation of being an outside observer of one’s mental processes, one’s body, or parts of one’s body. Symptoms of DP involve an alteration in the perception or experience of the self so that the usual sense of one’s own reality is temporarily lost or changed. This is manifested by a sensation of self-estrangement or unreality, which may include the feeling that one’s extremities have changed in size, or the experience of seeming to

11

perceive oneself from a distance. Moreover, the individual may feel ”mechanical” or as in a dream, or even as in a bubble soap or under a crystal cloak. Various types of sensory anesthesia, automaton or robot-like experiences, lack of affective response, and a sensation of lacking control of one’s actions, including speech are often present. A perceived change in the size or shape of objects in the external world is common and people may be perceived as dead or mechanical. DP is often associated with derealization (DR), which is manifested by a strange alteration in the perception of one’s surroundings so that a sense of the reality of the external world is lost. All these feelings are egodystonic and the individual maintains grossly intact reality testing, meaning that the sufferer retains insight that these are subjective phenomena rather than objective reality.

1.4 Brain imaging studies of depersonalization

Imaging studies, or that make reference to DP or look DPD specifically, they even gave us new insights into this condition. DP symptoms were induced in healthy subjects by chemical means and then visualized by brain imaging. In one PET study by Matthew et al. (1999) in which THC was given to normal individuals, marijuana caused an increase in blood flow in the MPC and in the ACC and this increase correlated with intense DP symptoms. There was even a reduction in subcortical blood flow to areas as amygdala and hippocampus. This finding supports the cortico-limbic disconnection hypothesis described above, which implies hyperactive prefrontal and hypoactive limbic system in DP. Another study in question originates from literature on PTSD. Lanius et al. (2002) studied two groups of patients with

12

PTSD. Those who when presented with traumatic remainders experienced intense arousal, increased heart rate, and flashbacks, and those who when presented with traumatic reminders experienced dissociative bouts with no increase in heart rate. Interestingly, these two groups was very different from each other when their brain activity was studied using fMRI in real time as the participants were exposed to their personalized traumatic scripts. In particular, the dissociative groupdisplayed increased brain activity in the MPC and the ACC (both involved in cognitive processing and inhibition of limbic emotional responses), just as increased brain activity in cortical sensory association areas of the temporal, parietal and occipital lobes. These patterns of cerebral activity in the dissociative group are much along the lines of what might be expected on the basis of the background patterns for dissociation and correspond with the two imaging studies that have been done regarding DPD. Phillips et al. (2001) compared patients with DPD, obsessive compulsive disorder and normal volunteers by using fMRI techniques to detect changes in the brain as people were presented with different tasks. Their findings show that, contrary to normal and obsessive compulsive individuals, DPD patients showed an increased activation in their MPC, but did not activate the insula (the area for the emotion disgust) in response to aversive pictures. When the subjects rated the picture for emotional content, it was found that even though DPD participants knew intellectually that certain photographs were meant to be disgusting stimuli, their emotional experience was less aversive than that of the other two groups. All this goes hand in hand with the idea that DP individuals hypo-activate limbic regions,

13

regions that are important for processing emotions, and conversely, that they hyper-activate higher cortical areas. In conclusion, this study suggests a brain mechanism that could be the basis for the emotional inhibition, numbness and sense of unfamiliarity lived by chronically DP people. Another study by Phillips et al. (2001), found changes in brain activity in normal subjects who were administered the glutamate antagonist ketamine or a placebo. Ketamine led to an emotionally blunted response to viewing fearful faces. This ketamine induced hypo-emotionality that as been presented as a model of DP, was associated with reduced limbic responses to the emotionally charged faces and increased visual cortex activity in response to neutral faces. Another series studies in healthy volunteers attempted to look at what happens in the brain when we observe the stimuli that are perceived familiar or unfamiliar. These studies of visual familiarity found that unfamiliar faces activated only the narrow unimodal visual association areas, while familiar (or famous) faces produced more widespread activation of transmodal association areas, especially the middle temporal gyrus, area 21, and the angular gyrus, area 39. These results may indicate that in DP there is somehow a failure of sensory association cortex functioning, particularly at the major associations and connections. A PET study comparing DPD patients with a normal group did not show differences between the two groups in frontal and cingulate cortex (Simeon et al. 2000). All differences, which were found between the two groups, have been localized in the posterior part of the cortex, which is constituted by the temporal, parietal and occipital lobes. A closer inspection showed that the two samples differed in parietal areas 7B and 39, temporal areas 22

14

and 21, occipital area 19. All these areas are parts of the sensory association cortex which is controller to processing sensory stimuli within each sensory modalities. These include visual stimuli which primarily involve the occipital cortex, somatosensory stimuli (sense of our own body) which primarily involve the parietal cortex and auditory stimuli which primarily involve the temporal cortex. In patients with DPD, several sensory association areas showed different activity from what was seen in the normal group, in particular the parietal angular gyrus or area 39. This area also is linked to the frontal lobe so that higher order processing can occur. The angular gyrus is designed to be responsible for well-integrated body schema, so it is logical that it does indeed show altered activity in patients with DPD. People with strokes in this area of the brain show in clinical practice what is known in neurology as neglect syndrome. The analogy with DP here is tempting but people with DP cognitively know that their body exists, in contrast to the neurological scenario, which involves more structural damage (Sierra et al. 2002a). Another sensory cortex area that show a different activity in DPD subjects was parietal 7b which is primarily responsible for our somatosensory integration (Simeon et al. 2000). There was strong relationship between higher DP scores and higher activity in this brain area.

All these data, are quite coherent with the limbic-disconnection hypothesis and point to two main possibilities. First, there may be a diffuse dysfunction in the sensory areas of the cortex, resulting in a disruption of sensory processing, which may manifest with the perceptual distortions of DPD, including derealization and somatic disturbances of one’s sense of reality. Second, there may be hyperactivity of the

15

prefrontal cortex and suppression of limbic structures, manifesting in a hyper-cognitive presentation wherein people know they should feel, but because of hypo-emotionality, they are not really feeling.

1.5 Affective Temperament

The relationship between temperament, personal identity, and mental disorders, is complex and a fundamental interest to philosophy and psychopathology. More than other living creatures, human beings are constituted and characterized by the interplay of their genotype and phenotype. There appears to be an explanatory gap between the almost perfect genetic identity and the individual differences among humans. One reason for this gap is that a human being is a person besides a physiological organism (Stanghellini, 2010).

Actually the concept of affective temperaments is rooted in the German descriptive tradition. Kraepelin described four “fundamental states” (“Grundzustände”): depressive, manic, irritable and cyclothymic. He wrote that they “on the one hand frequently accompany the “free” intervals between attacks, on the other hand characterize the manic-depressive temperament in such cases also in which the full development of the malady is absent” (Kraepelin, 1921). Kretschmer extended Kraepelin's notion of premorbid behavioural models to embrace the full range of temperamental variants in the population. He theorized that psychoses “are only rare exaggerated editions of large wide-spread groups of healthy constitutions [that] have a genetic basis” (Kretschmer, 1925). Although Schneider onsidered hyperthymic and depressive “psychopathic personalities” as extremes in a statistical sense which

16

represented much more than simply the basis of mood disorders (Schneider, 2007), in recent years there has been a rejuvenation of the interest in the concept that some affective temperaments may costitute forms frustes or endophenotypic manifestations of vulnerability to bipolar spectrum disorders.

On this basis we can better define temperament as as a biological disposition, corresponding to a constitutional substrate. Temperament is expressed through a series of signs and characteristics usually manifested by some stability of mood, attitudes towards the environment, sensitivity to external stimuli and characteristic modes of reaction. Most researcher would agree that earlyage experiences account for a large variability of adult individual personality traits, so as the develop of personality traits is generally considered to be primarily through crucial environmental challenges and experiences. However, since the '80s some authors maintained some early and stable personality traits exist, which can be described as features of pre-morbid phases of major Psychiatric Illnesses (Akiskal et al.,1977; Cloninger, 1987; Bouchard et al., 1990). such traits are conceptualized in this Neo-Kraepelinian view, as genetically-based subclinical variants of correspondent diseases, or residual symptoms following major episodes of those illnesses. Akiskal (Akiskal, 1994) argues that temperamental dysthymia, cyclothymia and hyperthymia are the basic phenotypes that reflect the core genetic disposition to bipolar disorder. The temperamental model is supported by evidence that, despite a third of monozygotic twins not sharing a history of major bipolar disorder, they do display at least marked temperamental features with a detectable degree of emotional

17

oscillations. Moreover, a high rate of dysthymic, hyperthymic or cyclothymic temperament was found in children of bipolar patients assessed during puberty (Akiskal et al., 1985).

The concept of ‘affective temperament’ (AT), as operationalized in research originally conducted at the University of Tennessee (Akiskal et al., 1979; Akiskal and Mallya, 1987), derives from Greco- Roman and continental European psychiatry (Kraepelin, 1921; Kretschmer, 1936), and refers to specific constitutionally-based affective dispositions, i.e. melancholic-dysthymic, choleric-irritable, sanguinehyperthymic and labile-cyclothymic. These affective dispositions are believed to link a number of etiologic risk factors with the clinical expressions of major moods disorders (Koukopulos et al., 1983; von Zerssen and Possl, 1990; Akiskal, 1992). Kretschmer (1936) actually postulated that a cyclothymic disposition was central to all temperamental oscillations. The Tennessee research also relied heavily on the superb descriptions of Kurt Schneider (1958), even though he had a different conceptualization of the relationship of personality types and affective disorders. Temperament is an important—albeit relatively neglected—area of research, and bears a complex relationship with the later adjustment of the individual, and with its possible role in the development of psychopathological conditions from infancy to adulthood.

1.6 Depersonalization in bipolar disorder

Data on correlates of DP symptoms in mood disorders are scanty and, to the best of our knowledge, there are only one study about DP symptoms in patients with bipolar

18

disorder (Mula et al., 2008). Lifetime dissociative symptoms, as assessed with the DES, are highly present in BD, with 25.6% of BD-I and 25% of BD-II patients scoring more than 25 at the DES (the usually used cutoff score to screen for pathological dissociation). This is in keeping with a recently published study reporting similar findings (Oedegaard et al., 2008).

In a precedent studt we found that the presence of DES score higher than non-clnical population can have different explanations: the high prevalence of mood disorder comorbidity among patients with dissociative disorders (Johnson et al., 2006); the high prevalence of dissociative symptoms in a wide range of personality disorders, mainly cluster B; the possible association between cyclothymic temperament and dissociative symptoms (Oedegaard et al., 2008). Moreover we did not specifically distinguish between intra-episode and inter-episode DP symptoms, the association with an early onset of the disease may suggest the need of further investigation to clarify whether BD patients with lifetime DP configure a separate clinical phenotype characterized by other indices of disease severity (e.g. number of hospitalization, number of episodes, treatment resi stance).

Epidemiological data on phenomenology of panic attacks in the general population pointed out that derealization symptoms are referred more frequently by individuals with bipolar-panic comorbidity as compared with those with panic disorder only (Goodwin and Hoven, 2002). Along these lines, our data support the hypothesis that lifetime derealization symptoms may suggest bipolar-panic comorbidity. This information can be of great value considering that bipolar-panic comorbidity seems to

19

configure a unique entity from a clinical, neurobiological and genetic point of view (Goodwin and Hoven, 2002; MacKinnon and Zamoiski, 2006), characterized by poor response to treatment, early onset of BD, elevated rates of comorbid psychopathology, great levels of depression, more suicidal ideation and increased familial risk of affective disorders (Kessler et al., 1997; Dilsaver et al., 1997; Pini et al., 1997; Frank et al., 2005).

The aim of our study is to evaluate, in a sample of bipolar (BD) eutimic patients, the association between depersonalization symptoms, facial emotions expression recognition and affective temperament.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participants

Data were drawn from a study aimed to evaluate the development and validation of a new clinical instrument for the assessment of depersonalization symptoms: the Structured Clinical Interview for the Depersonalization-Derealization Spectrum (SCI-DER). Study participants included 300 subjects, in particular 258 consecutive patients with mood and anxiety disorders (7 were also diagnosed depersonalization disorder) and a comparison group of 42 unselected healthy controls enrolled at the same site.

Our study sample included an overall group of adult patients with a diagnosis of BD presenting for treatment at the Department of Psychiatry in Pisa, Italy, between

20

September 2006 and September 2007. To be enrolled this cohort of bipolar patients (95 bipolar I and II eutimic patients) have to fulfill the following criteria: (1) IV criteria for BD-I, BD-II confirmed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-Patient Edition (SCID-I) (Spitzer et al., 1992); (2) be in a euthymic state for least 2 months, confirmed by HAM-D (Hamilton, 1960) total score <8 and YMRS (Young et al., 1978) <6; (3) age between 18 and 60 years; (4) be willing to provide a written consent to undergo the experimental procedures; (5) absence of brain and/or severe physical illnesses. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the local ethic committee of the five Italian centers.

2.2 Measures and Instruments

All selected patients were assessed with the SCID-I (Spitzer et al., 1992) for current and lifetime Axis I comorbidity, the Structured Clinical Interview for the Depersonalization-Derealization Spectrum (SCI-DER) (Mula et al., 2008), the Semistructured Clinical Interview for Temperament (TEMPS-I) (Placidi et al. 1998; Akiskal et al. 1998), POFA (test of recognition of facial emotions expression) (Ekman &Friesen, 1976).

2.2.1 Structured Clinical Interview for Depersonalization-Derealization Spectrum (SCI-DER).

This instrument is based on a spectrum model that emphasizes soft-signs, sub-threshold syndromes as well as clinical and subsyndromal manifestations. Items of the interview include, in addition to DSM-IV criteria for depersonalization, a number of features derived from clinical experience and from a review of phenomenological

21

descriptions. The SCI-DER includes 49 items exploring “presence” or “absence” of lifetime spontaneous symptoms of DP organized into four domains: Derealization, Somatopsychic depersonalization, Autopsychic depersonalization and Affective depersonalization. The SCI-DER showed to be acceptable and displayed an excellent internal consistency (0.92), test-retest reliability at 15-20 days (r = 0.88), convergent validity (SCI-DER vs. DES r = 0.74). It significantly discriminated subjects with any diagnosis of mood and anxiety disorders from controls and subjects with depersonalization disorder from controls.

2.2.2 TEMPS-I (The Semistructured Affective Interview for Temperament)

Is a 20-min interview for the assessment of temperamental characteristics, made with the Akiskal and Mallya (1987) semistructured schedule for hyperthymic, depressive, cyclothymic and irritable temperaments. This instrument has a very good reliability and internal consistency.

2.2.3 The Ekman 60 Faces Test

The Ekman 60 Faces Test uses a range of photographs from the Ekman and Friesen series of Pictures of Facial Affect (Ekman&Friesen, 1976), which has been the most widely used and validated series of photographs in facial expression research. From this series, the faces of 10 actors (6 female, 4 male) were chosen, each displaying six basic emotions (happiness, sadness, disgust, fear, surprise and anger). The Ekman 60 Faces Test can be used to assess recognition of facial expressions of basic emotions.

22

The maximum test score indicating best performance is 60 for all six emotions and 10 for each basic emotion.

2.3 Statistical analysis

The frequency of categorical variables was compared using the Chi-Square test. The independent-sample t-test was used to compare continuous demographic and clinical variables. Associations were investigated using Pearson’s bivariate correlation procedures. A backward stepwise logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the association between the two groups of hyperthymic/cyclothymic bipolar patients with POFA and DER domains (the DER domains are considered dependent variable). All the statistical analysis was performed considering the different confounding variable (age, gender, panic disorder). All statistical analyses were 2-sided with an alpha error set at 0.05 and were conducted using SPSS, version 16.0.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Characteristics of the Sample

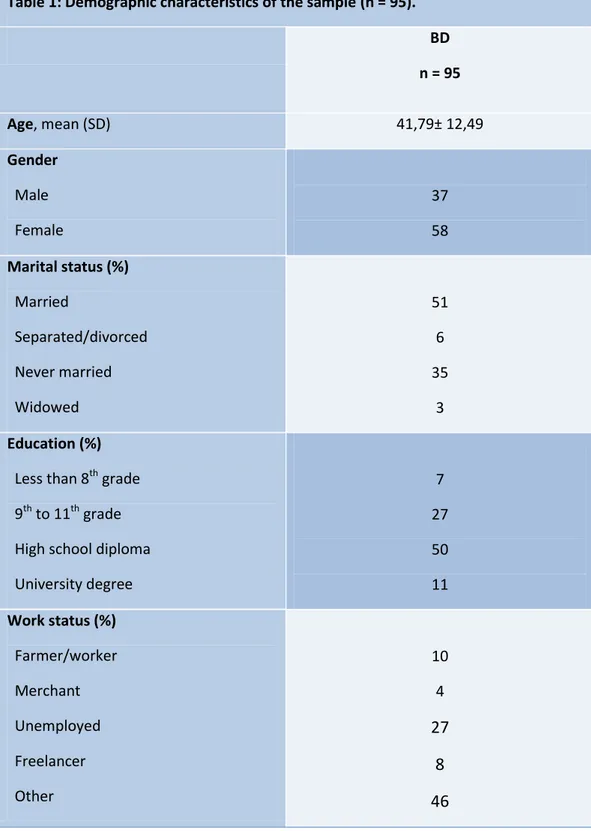

The study sample includes a total of 95 patients with an axis I diagnosis, are assessed. The characteristics are displayed in Table 1 (sociodemographic characteristics: age, gender, marital, education and work status statistics followed data displayed in literature. The different sociodemographic characteristics of hyperthymic and cyclothymic bipolar patients are explained in Table 2.

23 3.2 Depesonalization and depersonalization evaluation in the sample

In the sample in general between a stepwise regression analysis we underline that in BD patients, DER total Score is inversely associated with surprise emotion recognition (β= –2,733; p=0.008).

3.3 Affective Temperament, depersonalization and affective recognition

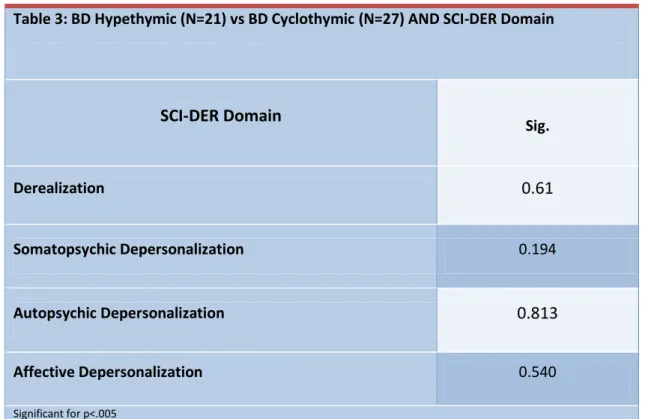

When we didn’t consider the POFA, in our sample we didn’t find any significant association between hyperthymic and cyclothymic temperament in bipolar disorder in age, gender , work, marital and school status. Moreover with a logistic regression we didn’t find any significant association with DER total score and hyperthymic/cyclothymic temperament (table 3).

Throught a regression analysis we underline that, independently to panic disorder, the hyperthymic temperament is associated with: major recognition of happiness (p< 0.001; β=-4,483) and minor recognition of anger (p=0.005; β=3,202) in BD patients with high scores in autopsychic depersonalization domain; major recognition of sadness (p=0.001; β=-3,944) and minor recognition of anger (p=0.005; β=3,181) in BD patients with high scores in affective depersonalization domain. Moreover, the cyclothymic temperament is associated with: major recognition of surprise (p=0.004; β=-3,233) and happiness (p=0.044; β=-2,124) in BD patients with high scores in Derealization (DER-TOT); major recognition of surprise (p=0.001; β=-3,792) and happiness (p=0.018; β=-2,532) in BD patients with high scores in somatopsychic depersonalization domain. (Table 4,5).

24

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The ability of an individual to be able to recognize the emotions of his species is a

key element within social relations, within the non-verbal communication between

individuals of the same species. Therefore, the inability to recognize any emotion, or

even confuse one with another emotion is a big problem for the non-verbal human

communication. The bipolar patients without symptoms of unreality seem not to be

"affected" by this serious deficit, whereas patients with bipolar derealization show

alterations that have different depending on the existing biological characteristics

(temperamental).

From the evolutionary point of view, some studies have shown that the

temperamental characteristics have adequate stability and are stable, but sometimes in

patients with mood disorders can be influenced from the last episode of illness that

was occurred, but it isn’t taken into consideration the presence of depersonalization

and derealization and the influence that these symptoms may have in the period after

an affective phase. Precisely this constant is determined by intrinsic genetic factors

appear to be modified by the presence of symptoms of depersonalization and

depersonalization with a different pattern depending on the type of temperament.

The characteristic of alienating depersonalisation seems to guarantee the persistence

of anomalies in the specific recognition of emotions and features of the pairs between

cyclothymic and hyperthymic temperament and, respectively, deficits in different

25

Also other authors have found in particular that under the stimulation of facial

expressions of happiness and sadness is possible to discriminate a number of brain

regions in patients with depersonalization disorder vs healthy controls (Lemche E et

al., 2011). But compared to other studies conducted as that of Murphy et al. (1999),

we cannot document whether there is an attentional bias and faster response for

manic patients to happiness target than sadness, as our study of a sample of bipolar

eutimic patients. At most, our data confirm the existence of cognitive deficits and

recognition of emotions during free interval periods of disease.

Our discovery also could play a key role in the therapeutic relationship and treatment

of the patient (in clinical setting and psychotherapeutic courses). If we think that in

cognitive therapy, according to the model of Beck and Ellis, the relationship between

cognition and emotion is a fundamental part in the discovery of the patient and the

construction of the mind and dysfunctional processes of the patient, we realize how it

can be affected by dissociative symptoms. The dissociative symptoms also may play

a negative role in the recognition of emotions and of the fundamental goals of the

individual, misleading the therapist to other behavioral and cognitive elements.

Limit of our study are: 1) We haven’t used a group of healthy controls in our study in

order to better highlight this characteristic association between symptoms of

depersonalization and derealization and affective temperaments in our group of

bipolar patients; 2) We haven’t investigated the personality disorders in our sample,

26

temperament and various axis I comorbidities; 3) we haven’t investigated the best

possible cognitive deficits with a neuropsychological battery of rating scales because

our sample was a subsample of a study for the validation of the instrument spectrum

SCI-DER; 4) We haven’t considered the possible effect of pharmacological therapies

in place even if the patients enrolled in the study had never performed ECT and

antipsychotic therapies such as clozapine; 5) SCI-DER is a clinical lifetime spectrum

instrument and so we couldn’t better characterize some clinical correlates and in

particular the onset and development of depersonalization and derealization

phenomena in relation to the various stages of disease; 7) The characteristic

differences that emerge in patients with bipolar disorder require further attention and

evaluation, to better highlight the differences between these two groups of patients.

Future purposes: in addition to seeking to overcome the limitations of this study we

propose to go through to evaluate with diagnostic tools such as MRI or EEG possible

alterations in the CNS in order to be able to better distinguish these groups of bipolar

patients by seeking brain correlated or particular bipolar endophenothypes behind this

27

TABLE:

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the sample (n = 95). BD n = 95 Age, mean (SD) 41,79± 12,49 Gender Male Female 37 58 Marital status (%) Married Separated/divorced Never married Widowed 51 6 35 3 Education (%)

Less than 8th grade 9th to 11th grade High school diploma University degree 7 27 50 11 Work status (%) Farmer/worker Merchant Unemployed Freelancer Other 10 4 27 8 46

28

Table 2: Demographic characteristics of the sample: BD Hyperthymic vs BD Cyclothymic (n = 48). Hyperthymic N=21 Cyclothymic N=27 Sig. Age, mean (SD) 41,00± 10,89 36,27±11,49 0.149 Gender Male Female 8 13 7 20 0.547 Marital status (%) Married Separated/divorced Never married Widowed 12 2 6 1 9 1 17 0 0.155 Education (%)

Less than 8th grade 9th to 11th grade High school diploma University degree 1 6 11 3 1 8 17 1 0.533 Work status (%) Farmer/worker Merchant Unemployed Freelancer Other 8 3 2 8 0 13 1 1 8 4 0.175

29

Table 3: BD Hypethymic (N=21) vs BD Cyclothymic (N=27) AND SCI-DER Domain

SCI-DER Domain Sig. Derealization 0.61 Somatopsychic Depersonalization 0.194 Autopsychic Depersonalization 0.813 Affective Depersonalization 0.540 Significant for p<.005

Table 4: BD Hypethymic (N=21), SCI-DER Domain and P.O.F.A.

Bipolar Patients Hyperthymic POFA Happyness POFA Sadness POFA Fear POFA Anger POFA Disgust POFA Surprise Derealization / / / / / / Somatopsychic Depersonalization / / / / / / Autopsychic Depersonalization P=.001 β=-4.483 / / P=.005 β = 3.202 / / Affective Depersonalization / P=.001 β=-3.944 / P=.005 β= 3.181 / / DER-TOT / / / / / / Significant for p<.005

30

Table 5: BD Cyclothymic (N=27), SCI-DER Domain and P.O.F.A.

Bipolar Patients Cyclothymic POFA Happyness POFA Sadness POFA Fear POFA Anger POFA Disgust POFA Surprise Derealization / / / / / / Somatopsychic Depersonalization p=.018 β =-2.532 / / / / P=.001 β=-3.792 Autopsychic Depersonalization / / / / / / Affective Depersonalization / / / / / / DER-TOT P=.044 β=-2.124 / / / / p=.004 β= -3.233 Significant for p<.005

31

References

Ackner B, 1954. Depersonalization. I. Aetiology and phenomenology; II. Clinical

syndromes. Journal of Mental Science 100(I,II): 838-872

Aderibigbe YA, Bloch RM, Walker WR, 2001. Prevalence of depersonalization and

derealization experiences in a rural population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 36:63-9

Adolphs R, Tranel D, Damasio H, Damasio A, 1994. Impaired recognition of emotion infacial expressions following bilateral damage to the human amygdala. Nature 372:669-672

Akiskal HS, Djenderedjian AM, Rosenthal RH, Khani MK, 1977. Cyclothymic disorder: validating criteria for inclusion in the bipolar affective group. Am J Psychiatry. 134:1227-33.

Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Zeller PJ, Endicott J, Coryell W, Keller M, Warshaw M, Clayton P, Goodwin F, 1995. Switching from 'unipolar' to bipolar II. An 11-year prospective study of clinical and temperamental predictors in 559 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 52:114-23.

Akiskal HS, Placidi GF, Maremmani I, Signoretta S, Liguori A, Gervasi R, Mallya G, Puzantian VR, 1998. TEMPS-I: delineating the most discriminant traits of the cyclothymic, depressive, hyperthymic and irritable temperaments in a nonpatient population. J Affect Disord. 51:7-19.

Akiskal HS, 1983. Dysthymic disorder: psychopathology of proposed chronic depressive subtypes. Am J Psychiatry. 140:11-20.

Akiskal HS, 1986. Mood Disturbances. In: Winokur G, Clayton P (Eds). The Medical Basis of Psychiatry. Philadelphia, Saunders Co.

Akiskal HS, Mallya G, 1987. Criteria for the “soft” bipolar spectrum: temperament implications. Psychopharmacol Bull. 23(1):68-73.

32

Akiskal HS, Rosenthal RH, Rosenthal TL, Kashgarian M, Khani MK, Puzantian VR, 1979. Differentiation of primary affective illness from situational, symptomatic and secondary depressions. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 36(6):635-643.

Akiskal HS, 1992. The depressive patient before depression. Encephale 18(4):485-489.

American Psychiatric Association, 2000. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th Ed – Text Revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association

American Psychiatric Association, 1980. DSM-III: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 3rd edn. Washington, DC: APA

Anand A, Charney DS, Oren DA, Berman RM, Hu XS, Cappiello A, Krystal JH, 2000. Attenuation of the neuropsychiatric effects of ketamine with lamotrigine: support for hyperglutamatergic effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 57:270-6.

Angst J, Cassano G, 2005. The mood spectrum: improving the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 7(Suppl 4):4-12 Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Methodik un Dokumentation in der Psychiatrie, 1979. Das AMDP-System 3° Ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag

Arlow JA, 1966. Depersonalization and derealization. In: Arlow JA Ed. Psychoanalysis: A general psychology. New York: International University Press

Baker D, Hunter E, Lawrence E, Medford N, Patel M, Senior C, Sierra M, Lambert MV, Phillips ML, David AS, 2003. Depersonalisation disorder: clinical features of 204 cases. Br J Psychiatry. 182:428-33.

Ball S, Robinson A, Shekhar A, Walsh K, 1997. Dissociative symptoms in panic disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 185:755-760 92

Bebbington PE, Hurry J, Tennant C, Sturt E, Wing JK, 1981. Epidemiology of mental disorders in Camberwell. Psychol Med 11:561-579

33

Bebbington PE, Marsden L, Brewin CR, 1997. The need for psychiatric treatment in the general population: the Camberwell Needs for Care Survey. Psychol Med. 27:821-834

Bernstein EM, Putnam FW, 1986. Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. J Nerv Ment Dis. 174:727-735.

Berrios GE, Luque R, 1995. Cotard’s delusion or syndrome ? a conceptual history. Comprehensive Psychiatry 36:218-223

Bouvet M, 1967. OEuvres psychanalytiques. I: La Relation d'objet: névrose obsessionnelle, dépersonnalisation. Paris: Payot.

Bremner JD, 2004. Brain imaging in anxiety disorders. Expert Rev Neurotherapeutics 4:275-284

Bremner JD, Steinberg M, Southwick SM, Johnson DR, Charney DS, 1993. Use of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Dissociative Disorders for systematic assessment of dissociative symptoms in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 150:1011-1014.

Briere J, Weathers FW, Runtz M, 2005. Is dissociation a multidimensional construct? Data from the Multiscale Dissociation Inventory. J Trauma Stress. 18:221-231

Cahill L, Haier RJ, Fallon J, Alkire MT, Tang C, Keator D, Wu J, McGaugh JL, 1996. Amygdala activity at encoding correlated with long-term, free recall of emotional information. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:8016-8021

Carlson EB, Putnam FW, 1993. An update on the dissociative experiences scale. Dissociation 6:16-27

Cassano GB, Frank E, Miniati M, Rucci P, Fagiolini A, Pini S, Shear MK, Maser JD, 2002. Conceptual underpinnings and empirical support for the mood spectrum. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 25:699-712

34

Cassano GB, Petracca A, Perugi G, Toni C, Tundo A, Roth M, 1989. Derealization and panic attacks: a clinical evaluation on 150 patients with panic disorder/agoraphobia. Compr Psychiatry. 30:5-12

Cassano GB, Rotondo A, Maser JD, Shear MK, Frank E, Mauri M, Dell'Osso L, 1998. The panic-agoraphobic spectrum: Rationale, assessment, and clinical usefulness. CNS Spectr 3:23-34

Cattel JP, Cattel JS, 1974. Depersonalization: psychological and social perspectives. In American handobook of psychiatriy. New York: Basic Books 1974:766-799

Chambless DL, Caputo GC, Bright P, Gallagher R, 1984. Assessment of fear of fear in agoraphobics: the body sensations questionnaire and the agoraphobic cognitions questionnaire. J Consult Clin Psychol. 52:1090-7

Cotard J, 1882. Du délire des negation. Archives de Neurologie 4:150-170, 282-295

Critchley HD, Mathias CJ, Josephs O, O'Doherty J, Zanini S, Dewar BK, Cipolotti L, Shallice T, Dolan RJ, 2003. Human cingulate cortex and autonomic control: converging neuroimaging and clinical evidence. Brain. 126:2139-2152

Darwin C, (1872). The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals

Davidson RJ, Sutton SK, 1995. Affective neuroscience: the emergence of a discipline. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 5:217-24

Di Florio A, Hamshere M, Forty L, Green EK, Grozeva D, Jones I, Caesar S, 2010. Affective temperaments across the bipolar–unipolar spectrum: Examination of the TEMPS-A in 927 patients and controls, J of Affect Disord 123: 42–51

Dilsaver SC, Chen YW, Swann AC, Shoaib AM, Tsai-Dilsaver Y, Krajewski KJ, 1997. Suicidality, panic disorder and psychosis in bipolar depression, depressive-mania and puredepressive-mania. Psychiatry Res. 73:47-56.

Dixon JC, 1963. Depersonalization phenomena in a sample population of college students. Br J Psychiatry. 109:371-375

35

Downer JL, 1961. Changes in visual gnostic functions and emotional behaviour following unilateral temporal pole damage in the 'split-brain' monkey. Nature. 191:50-51

Dugas L, 1898. Un cas de dépersonalization. Revue philosophique 55:500-7 Eiley KC, 1988. Measurement of dissociation. J Nerv Ment Dis. 176:449-450 Ekman P, Friesen WV, O'Sullivan M, Chan A, Diacoyanni-Tarlatzis I, Heider K, Krause R, LeCompte WA, Pitcairn T, Ricci-Bitti PE, et al., 1987. Universals and cultural differences in the judgments of facial expressions of emotion. J Pers Soc Psychol. Oct;53(4):712-7.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. (1976). Pictures of facial affect. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Fagiolini A, Dell’Osso L, Pini S, Armani A., Bouanani S, Rucci P, Cassano GB, Endicott J, Maser J, Shear MK, Grochocinski VJ, Frank E, 1999. Validity and reliability of a new instrument for assessing mood symptomatology: The Structured Clinical Interview for Mood Spectrum (SCI-MOODS). Int. J. Methods. Psychiatr. Res. 8, 71-81.

Fenichel O, 1945. The Psychoanalytic Theory of Neurosis. 3 vol. New York: Norton

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW, 2001. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P). New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute

Fleck MP, Poirier-Littre MF, Guelfi JD, Bourdel MC, Loo H, 1995. Factorial structure of the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 92:168-72.

Frank E, Cyranowski JM, Rucci P, Shear MK, Fagiolini A, Thase ME, Cassano GB, Grochocinski VJ, Kostelnik B, Kupfer DJ, 2002. Clinical significance of lifetime panic spectrum symptoms in the treatment of patients with bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59:905-11.

36

Frank E., Cassano GB, Shear MK, Rotondo A, Dell’Osso L, Mauri M, Maser J, Grochocinski V, 1998. The spectrum model: A more coherent approach to the complexity of psychiatric symptomatology. CNS Spectr. 3:23-34.

Freeman MP, Freeman SA, McElroy SL, 2002. The comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: prevalence, psychobiology, and treatment issues. J Affect Disord. 68:1-23

Freud S, Breuer J, 1892-95. Studien über Hysterie. In: Gesammelte Werke (18 vol.). (1940-1950). Francoforte: Fischer Geschwind N, 1965a. Disconnexion syndromes in animals and man. I. Brain. 88:237-294

Geschwind N, 1965b. Disconnexion syndromes in animals and man. II. Brain. 88:585-644

Gibbons RD, Clark DC, Kupfer DJ, 1993. Exactly what does the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale measure? J Psychiatr Res. 27:259-73.

Gloor P, 1990. Experiential phenomena of temporal lobe epilepsy. Facts and hypotheses. Brain. 113:1673-1694

Goodwin FK, Jamison KR, 1990. Manic depressive illness. New York: Oxford University Press

Goodwin RD, Hoven CW, 2002. Bipolar-panic comorbidity in the general population: prevalence and associated morbidity. J Affect Disord. 70:27-33

Gruhle HW, 1932. Der Wahn. In Handbuch der GeistesKrankheiten. Bumke O. Ed. Berlin: Springer

Hamann SB, Stefanacci L, Squire LR, Adolphs R, Tranel D, Damasio H, Damasio A, 1996. Recognizing facial emotion. Nature. 379:497

Heinz A, Schmidt LG, Reischies FM, 1994. Anhedonia in schizophrenic, depressed, or alcohol-dependent patients--neurobiological correlates. Pharmacopsychiatry. 27 (Suppl 1):7-10

Hollander E, Fairbanks J, Decaria C, Liebowitz MR, 1989. Pharmacological dissection of panic and depersonalization. Am J Psychiatry 143:402

37

Holmes EA, Brown RJ, Mansell W, Fearon RP, Hunter EC, Frasquilho F, Oakley DA, 2005. Are there two qualitatively distinct forms of dissociation? A review and some clinical implications. Clin Psychol Rev. 25:1-23.

Hunter EC, Sierra M, David AS, 2004. The epidemiology of depersonalisation and derealisation. A systematic review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 39:9-18

Jacobs JR, Bovasso GB, 1992. Toward the clarification of the construct of depersonalization and its association with affective and cognitive dysfunctions. J Pers Assess 59:352-365

Jacobson E, 1959. Depersonalization. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 7:581-610. Janet P, 1903. Les obsessions et la psychasthenie. Paris: Alcan

Janet P, 1889. L’automatisme psychologique : essai de psychologie experimentale sur les formes inferieures de l'activite humaine. Paris : Alcan

Jaspers K, 1913. Allgemeine Psychopathologie. Berlin: Springer Verlag

Jimenez-Genchi AM, 2004. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation improves depersonalization: a case report. CNS Spectr. 9:375-376

Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS, 2006. Dissociative disorders among adults in the community, impaired functioning, and axis I and II comorbidity. J Psychiatr Res. 40:131-40

Kessler RC, Rubinow DR, Holmes C, Abelson JM, Zhao S, 1997. The epidemiology of DSM-III-R bipolar I disorder in a general population survey. Psychol Med. 27:1079-89.

Klein DF, 1974. Endogenomorphic depression. A conceptual and terminological revision. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 31:447-54.

Klein M, 1946. Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. Int J Psychoanal. 27: 99-110.

Kluft RP, Steinberg M, Spitzer RL, 1988. DSM-III-R revisions in the dissociative disorders: an exploration of their derivation and rationale. Dissociation. 1: 39-46

38

Krishaber M, 1873. De la neuropatie cerebro-cardiaque. Paris: Masson

Kruger C, Mace CJ, 2002. Psychometric validation of the State Scale of Dissociation (SSD). Psychol Psychother. 75:33-51

Lambert MV, Senior C, Fewtrell WD, Phillips ML, David AS, 2001. Primary and secondary depersonalisation disorder: a psychometric study. J Affect Disord. 63:249-256

LeDoux JE, Iwata J, Cicchetti P, Reis DJ, 1988. Different projections of the central amygdaloid nucleus mediate autonomic and behavioral correlates of conditioned fear. J Neurosci. 8:2517-2529

Lewis A, 1931. The experience of time in mental disorder. Proc R Soc Med 25:611-620

Lish JD, Dime-Meenan S, Whybrow PC, Price RA, Hirschfeld RMA, 1994. The national depressive and manic-depressive association (DMDA) survey of bipolar members. J. Affect. Disord. 31:281–294.

MacKinnon DF, Zamoiski R, 2006. Panic comorbidity with bipolar disorder: what is the manic-panic connection? Bipolar Disorders. 8:648-664.

Marquez M, Segui J, Garcia L, Canet J, Ortiz M, 2001. Is panic disorder with psychosensorial symptoms (depersonalization-derealization) a more severe clinical subtype? J Nerv Ment Dis. 189:332-335

Mayer-Gross W, 1935. On depersonalization. Br J Med Psychol 15: 103-126. Medford N, Baker D, Hunter E, Sierra M, Lawrence E, Phillips ML, David AS, 2003. Chronic depersonalization following illicit drug use: a controlled analysis of 40 cases. Addiction. 98:1731-6.

Michal M, Kaufhold J, Grabhorn R, Krakow K, Overbeck G, Heidenreich T, 2005. Depersonalization and social anxiety. J Nerv Ment Dis 193:629-32

Milak MS, Parsey RV, Keilp J, Oquendo MA, Malone KM, Mann JJ, 2005. Neuroanatomic correlates of psychopathologic components of major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 62:397-408.

39

Maremmani I, Pacini M, Popovic D, Romano A, Maremmani AGI, Perugi G, Deltito J, Akiskal KS, Akiskal HS, 2009. Affective temperaments in heroin addiction, J of Affect Disord 117:186–192

Morgan CA 3rd, Rasmusson AM, Wang S, Hoyt G, Hauger RL, Hazlett G, 2002. Neuropeptide-Y, cortisol, and subjective distress in humans exposed to acute stress: replication and extension of previous report. Biol Psychiatry. 52:136-42.

Morris JS, Friston KJ, Dolan RJ, 1997. Neural responses to salient visual stimuli. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 264:769-775

Mula M, Pini S, Cassano GB, 2007a. The neurobiology and clinical significance of depersonalization in mood and anxiety disorders: a critical reappraisal. J Affect Disord. 99:91-9.

Mula M, Pini S, Cassano GB, 2007b. [Rating scales for the assessment of depersonalization symptoms: a review] Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 16:265-70.

Mula M, Pini S, Calugi S, Preve M, Masini M, Giovannini I, Conversano C, Rucci P, Cassano GB, Validity and reliability of the Structured Clinical Interview for Depersonalization-Derealization Spectrum (SCI-DER), Neurops Dis Treat, 2008:4(5):977-986.

Noyes R Jr, Kletti R, 1977. Depersonalization in response to life-threatening danger. Compr Psychiatry. 18:375-384

Nuller YL, 1982. Depersonalisation--symptoms, meaning, therapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 66:451-458.

Oedegaard KJ, Neckelmann D, Benazzi F, Syrstad VE, Akiskal HS, Fasmer OB, 2007. Dissociative experiences differentiate bipolar-II from unipolar depressed patients: The mediating role of cyclothymia and the Type A behaviour speed and impatience subscale. J Affect Disord. 2007 Dec 10; [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 18077000 98

Perugi G, Toni C, Akiskal HS, 1999. Anxious-bipolar comorbidity. Diagnostic and treatment challenges. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 22:565-83, viii

40

Phillips DW, 1994. Initial development and validation of the Phillips Dissociative Scale (PDS) of the MMPI. Dissociation. 7:92-100

Phillips ML, Drevets WC, Rauch SL, Lane R, 2003. Neurobiology of emotion perception II: Implications for major psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 54:515-28.

Phillips ML, Medford N, Senior C, Bullmore ET, Suckling J, Brammer MJ, Andrew C, Sierra M, Williams SC, David AS, 2001. Depersonalization disorder: thinking without feeling. Psychiatry Res. 108:145-60

Pini S, Cassano GB, Simonini E, Savino M, Russo A, Montgomery SA, 1997. Prevalence of anxiety disorders comorbidity in bipolar depression, unipolar depression and dysthymia. J Affect Disord. 42:145-53.

Placidi GF, Signoretta S, Liguori A, Gervasi R, Maremmani I, Akiskal HS, 1998. The semi-structured affective temperament interview (TEMPS-I). Reliability and psychometric properties in 1010 14-26-year old students. J Affect Disord. 47:1-10.

Ribot T, 1895. Les maladies de la personalite 6th ed. Paris: Alcan

Rosenfeld H, 1947. Analysis of a schizophrenic state with depersonalization. Int J Psychoanal. 28:130-139.

Ross CA, Joshi S, Currie R, 1991. Dissociative experiences in the general population: a factor analysis. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 42:297-301

Roth M, 1960. The phobic anxiety-depersonalization syndrome and some general aetiological problems in psychiatry. J Neuropsychiatr. 1:293-306

Roth M, Argyle N, 1988. Anxiety, panic and phobic disorders: an overview. J Psychiatr Res. 22(Suppl 1):33-54

Roth M, 1960. The phobic anxiety-depersonalization syndrome and some general aetiological problems in psychiatry. J Neuropsychiatr 1:293-306

Rottenberg J, Johnson SL, 2007. Emotion and Psychopathology: Bridging Affective and Clinical Science. Washington: APA

41

Rush AJ, Weissenburger JE, 1994. Melancholic symptom features and DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry. 151:489-98.

Sar V, Kundakci T, Kiziltan E, Bakim B, Bozkurt O, 2000. Differentiating dissociative disorders from other diagnostic groups through somatoform dissociation in Turkey. J Trauma Dissociation. 1:67-80.

Sarlin CN, 1962. Depersonalization and derealization. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 10:784- 804

Saxe GN, van der Kolk BA, Berkowitz R, Chinman G, Hall K, Lieberg G, Schwartz J, 1993. Dissociative disorders in psychiatric inpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 150:1037-1042

Schilder P, 1935, Immagine di sé e schema corporeo, Franco Angeli, Milano 1973

Schilder P, 1938. The social neurosis. Psychoanal Rev. 25:1–19.

Schilder P, 1953. Medical psychology. New York: International Universities Press

Sedman G, Kenna JC, 1963. Depersonalization and mood changes in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 109:669-673

Segui J, Marquez M, Garcia L, Canet J, Salvador-Carulla L, Ortiz M, 2000. Depersonalization in panic disorder: a clinical study. Compr Psychiatry. 41:172-178

Shorvon HJ, 1946. The depersonalization syndrome. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 39:779-92

Sierra M, Baker D, Medford N, David AS, 2005. Unpacking the depersonalization syndrome: an exploratory factor analysis on the Cambridge Depersonalization Scale. Psychol Med. 35:1523-32.

Sierra M, Baker D, Medford N, Lawrence E, Patel M, Phillips ML, David AS, 2006. Lamotrigine as an add-on treatment for depersonalization disorder: a retrospective study of 32 cases. Clin Neuropharmacol. 29:253-8.

Sierra M, Berrios GE, 2001. The phenomenological stability of depersonalization: comparing the old with the new. J Nerv Ment Dis. 189:629-636

42

Sierra M, Berrios GE, 1998. Depersonalization: neurobiological perspectives. Biol Psychiatry. 44:898-908

Sierra M, Berrios GE, 2000. The Cambridge Depersonalization Scale: a new instrument for the measurement of depersonalization. Psychiatry Res 93:153-164

Sierra M, Berrios GE, 2001. The phenomenological stability of depersonalization: comparing the old with the new. J Nerv Ment Dis 189:629-636

Sierra M, Lopera F, Lambert MV, Phillips ML, David AS, 2002a. Separating depersonalisation and derealisation: the relevance of the "lesion method". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 72:530-2

Sierra M, Phillips ML, Ivin G, Krystal J, David AS, 2003. A placebo-controlled, cross-over trial of lamotrigine in depersonalization disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 17:103-105.

Sierra M, Senior C, Dalton J, McDonough M, Bond A, Phillips ML, O'Dwyer AM, David AS, 2002. Autonomic response in depersonalization disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 59:833-838

Simeon D, 2004. Depersonalisation disorder: a contemporary overview. CNS Drugs. 18:343-354

Simeon D, Abugel J, 2006. Feeling unreal: depersonalisation disorder and the loss of the self. New York: Oxford University Press

Simeon D, Guralnik O, Gross S, Stein DJ, Schmeidler J, Hollander E, 1998. The detection and measurement of depersonalization disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 186:536-42.

Simeon D, Guralnik O, Hazlett EA, Spiegel-Cohen J, Hollander E, Buchsbaum MS, 2000. Feeling unreal: a PET study of depersonalization disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 157:1782-8.

Simeon D, Guralnik O, Knutelska M, Hollander E, Schmeidler J, 2001. Hypothalamicpituitary- adrenal axis dysregulation in depersonalization disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 25:793-795

43

Simeon D, Guralnik O, Knutelska M, Yehuda R, Schmeidler J, 2003. Basal norepinephrine in depersonalization disorder. Psychiatry Res. 121:93-97

Simeon D, Guralnik O, Schmeidler J, Knutelska M, 2004. Fluoxetine therapy in depersonalisation disorder: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 185:31-6

Simeon D, Guralnik O, Schmeidler J, 2001. Development of a Depersonalization Severity Scale. J Trauma Stress 14:341-349

Simeon D, Knutelska M, 2005. An open trial of naltrexone in the treatment of depersonalization disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 25:267-270

Simeon D, Knutelska M, Nelson D, Guralnik O, 2003a. Feeling unreal: A depersonalization disorder update of 117 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 64:990 –997.

Simeon D, Knutelska M, Nelson D, Guralnik O, Schmeidler J, 2003. Examination of the pathological dissociation taxon in depersonalization disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 191:738- 44.

Simeon D, Kozin DS, Segal K, Lerch B, Dujour R, Giesbrecht T, 2008. De-constructing depersonalization: Further evidence for symptom clusters. Psychiatry Res. 157:303-6

Simeon D, Kozin DS, Segal K, Lerch B, Dujour R, Giesbrecht T, 2008. De-constructing depersonalization: Further evidence for symptom clusters. Psychiatry Res. 157:303-6

Simeon D, Stein DJ, Hollander E, 1998. Treatment of depersonalization disorder with clomipramine. Biol Psychiatry. 44:302-303.

Simeon D, 2004. Depersonalisation disorder: a contemporary overview. CNS Drugs 18:343-354

Sokolski KN, Denson TF, 2003. Exacerbation of mania secondary to right temporal lobe astrocytoma in a bipolar patient previously stabilized on valproate. Cogn Behav Neurol 16:234-238

Stanghellini G, Rosfort R, 2010. Affective temperament and personal identity. J Affct Disord 126(1-2): 317-320.

44

Stanton BR, David AS, Cleare AJ, Sierra M, Lambert MV, Phillips ML, Porter RJ, Gallagher P, Young AH, 2001. Basal activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in patients with depersonalization disorder. Psychiatry Res. 104:85-9.

Stein MB, Goldin PR, Sarren J, Zorilla LTE, Brown GG, 2002. Increased amygdale activation to angry and contemptuous faces in generalized social phobia. Arch Gen Psych 59:1027-1034

Steinberg M, Rounsaville B, Cicchetti D, 1991. Detection of dissociative disorders in psychiatric patients by a screening instrument and a structured diagnostic interview. Am J Psychiatry 148:1050-1054.

Steinberg M, Schnall M, 2000. The stranger in the mirror - Dissociation: The Hidden Epidemic. New York: HarperCollins

Stewart WA, 1964, “Panel on depersonlization”, J Am Psychiatry Ass, 12:171-186.

Thomas P, 2004. The many forms of bipolar disorder: a modern look at an old illness. J. Affect. Disord. 79(Suppl 1):S3-8.

Torch EM, 1978. Review of the relation between obsession/depersonalization. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 58:191-8

Van der Hart O, Nijenhuis E, Steele K, Brown D, 2004. Trauma-related dissociation: conceptual clarity lost and found. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 38:906-14.

Von Zerssen D, De Possl J, 1990. The premorbid personality of patients with different subtypes of an affective illness. Statistical analysis of blind assignment of case history data to clinical diagnoses. J Affect Disord 18(1):39-50.

Waller NG, Ross CA, 1997. The prevalence and biometric structure of pathological dissociation in the general population: taxometric and behavior genetic findings. J Abnorm Psychol. 106:499-510.

Waller NG, Putnam FW, Carlson EB, 1996. Types of dissociation and dissociative types: A taxometric analysis of dissociative experiences. Psychol Methods. 1:300-321.