Duloxetine in the treatment of elderly people

with major depressive disorder

L’uso della duloxetina nel trattamento degli anziani con disturbo

depressivo maggiore

ANTONIO DEL CASALE

1, PAOLO GIRARDI

1,2, ROBERTO BRUGNOLI

1, GABRIELE SANI

1,

SIMONE DI PIETRO

1, CHIARA BRUGNOLI

1, FEDERICA CACCIA

1, GLORIA ANGELETTI

1,

DANIELE SERATA

1,2, CHIARA RAPINESI

1,2, ROBERTO TATARELLI

1, GEORGIOS D. KOTZALIDIS

1E-mail: [email protected]

1School of Medicine and Psychology, NESMOS Department (Neuroscience, Mental Health and Sensory Organs), Sant’Andrea Hospital, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy

2Department of Neuropsychiatry, Villa Rosa Hospital, Suore Ospedaliere del Sacro Cuore di Gesù, Viterbo, Italy

SUMMARY. Introduction. The elderly population is more frequently subjected to depressive mood compared to the

gener-al population and show peculiarities affecting responsiveness; furthermore, aged people need gener-also specigener-al care. Duloxetine is a relatively new antidepressant that proved to be effective in adult depression, but has received little attention in elderly pop-ulations heretofore. Aim. To review the evidence of duloxetine in late-life major depressive disorder (MDD). Method. A sys-tematic review of studies focusing on the use of duloxetine in MDD in the elderly has been carried out through the principal specialized databases, including PubMed, PsycLIT, and Embase. Results. Only a handful of papers were specifically dedicat-ed to this issue. Duloxetine was found to be effective and safe in old-age MDD, to be better than placebo on many clinical measures in all studies, and to better differentiate from placebo with respect to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Com-pared to placebo, its side-effect profile is slightly unfavorable and its drop-out rate is slightly higher. Furthermore, when pain is present in old-age MDD, duloxetine is able to reduce it. Conclusions. The efficacy and safety of duloxetine in old-age de-pression are similar to those encountered in adult MDD. There is a relative lack of comparative studies other than with place-bo. The special needs of elderly patients with MDD must be addressed with close patient contact to avoid the perils of inap-propriate dosing.

KEY WORDS: duloxetine, major depressive disorder, pain, old age, antidepressant pharmacotherapy.

RIASSUNTO. Introduzione. La popolazione anziana è maggiormente soggetta a umore depresso rispetto alla popolazione

generale, con caratteristiche particolari che influenzano la responsività al trattamento farmacologico. Tali pazienti richiedono particolari accorgimenti curativi. La duloxetina è un antidepressivo relativamente nuovo, efficace nella depressione dell’adul-to, ma che non ha finora ricevuto sufficiente attenzione per il suo uso nell’anziano. Scopo. Passare in rassegna l’evidenza ri-guardante l’uso della duloxetina nel disturbo depressivo maggiore (DDM) dell’anziano. Metodo. È stata condotta una ricer-ca sistematiricer-ca di tutti gli studi centrati sull’uso della duloxetina in pazienti anzianti con DDM, attraverso le maggiori basi di dati informatiche, quali PubMed, PsycLIT ed Embase. Risultati. Sono relativamente pochi i lavori dedicati all’argomento, in base ai quali la duloxetina risulta efficace e ben tollerata nel DDM dell’anziano; inoltre, essa si dimostra, in tutti gli studi, su-periore al placebo nel migliorare molti parametri clinici in tutti gli studi, e si differenzia maggiormente dal placebo rispetto agli inibitori selettivi della ricaptazione della serotonina. Il suo profilo di effetti collaterali è solo lievemente sfavorevole ri-spetto al placebo e il suo tasso di drop-out è leggermente superiore a quello del placebo. La duloxetina è efficace nei pazien-ti anziani anche su alcune sintomatologie dolorose organiche in comorbilità con la sintomatologia depressiva. Conclusioni. L’efficacia e la tollerabilità della duloxetina nel paziente anziano con DDM sono simili a quelle riscontrate nel paziente adul-to. Vi è una relativa scarsità di studi comparativi, eccetto che contro placebo. I peculiari bisogni e aspetti clinici dei pazienti anziani con DDM vanno affrontati con attente e costanti visite, per evitare errori nella prescrizione dei dosaggi dei farmaci.

tive effects of androgen replacement on mood. The role

of androgens in the human involves both the regulation

of sexuality and psychological aspects like aggression,

social ranking, general emotionality, and personality.

These effects are also influenced by social factors.

Be-sides this, sex hormones play a cardinal role in the

de-velopment and maintenance of acquired cognitive

abil-ities. At least in part, hormonal changes in androgen

levels in elderly men modulate cognitive changes

oc-curring with aging. Treatment with androgens in

hypog-onadal men improved neurocognition and mentation,

verbal and visual memory, visuomotor scanning and

at-tention, verbal fluency and understanding, and spatial

abilities and memory for both verbal and visual

infor-mation. The behavioral symptoms of PADAM may be

ascribed to multiple factors, including both biological

changes occurring with age and social adaptations

oc-curring during the mid-life transition (5,6).

Similar considerations may be made for

post-menopausal women, a group of persons in which

de-pressive and sexual symptoms are more severe than in

other age groups and are both associated with stressful

life events (8,9). Post-menopausal women with MDD

showed better antidepressant response to selective

serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) when this

treat-ment has been administered in combination with

hor-monal substitution therapy (10).

Another important point in elderly depression is the

increased risk of suicide. Various combinations of risk

factors for suicide must be considered in the elderly. The

concomitance of depressive symptoms and stressful life

events, such as feelings of loss, loneliness, and physical

illness in the elderly are to be considered as warning

signs for suicidal behavior (11,12). Loss of libido and

other aspects of sexuality may also constitute a

signifi-cant part of suicidal ideation in the elderly (13).

The physician should carefully assess, for elderly

pa-tients with depression, any underlying organic causes

and comorbidities, including diabetes (14,15),

hyper-tension (16), cardiovascular diseases (17), obesity

(18,19), deficiency of vitamin B12 (20,21), vitamin D

(22,23), folate (20,24,25), homocysteine (20,25,26),

anemia or iron deficiency (27,28) or iron overload

(29-32), and in general, the state of nutrients and

micronu-trients that might influence mood (33).

Duloxetine inhibits the transporters of both

sero-tonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NA), thus it belongs

to the class of the Serotonin-Norepinehrine Reuptake

Inhibitors (SNaRIs). A meta-analysis conducted by

Gi-rardi et al. (34) showed that duloxetine has hood

evi-dence of efficacy in acute, adult MDD, especially at

doses of 80-120 mg/day. About six hours after oral

ad-ministration, duloxetine reaches a maximum plasma

INTRODUCTION

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is common in

aged people and is frequently associated with

cogni-tive impairment and disability. Furthermore, clinically

significant depressions, like MDD and other forms of

unipolar depression constitute part of the clinical

course of dementia in the elderly, or complicate it or

are frequently comorbid with it.

MDD affects about 1-4% of the general aged

popula-tion (1), accounting for almost 5% of dementia

syn-dromes (2). Kobayashi (3) introduced a new and more

dynamic approach to investigate the relationship

be-tween depression and dementia, coining the term of

“de-pression-dementia medius”. Within this model,

depres-sion, cognitive impairment, and degenerative dementia

are viewed as an intersecting continuum, in which

pseu-dodementia and depression in dementia are located

in-termediately between depression and dementia.

Apathy is characterized by a partial lack of

motiva-tion, but differently from avolimotiva-tion, it also concerns a

sluggish response to environmental stimuli, a sort of

emotional unresponsiveness. It is primary deficit that

should be distinguished from both cognitive decline

and depressive mood. Apathy may be a common

fea-ture of psychotic disorders, it may be part of a

depres-sive syndrome, and may be extremely common in

de-mentia. It coexists with depression in the same patient

all too frequently, but it should be routinely assessed

during neuropsychiatric evaluation independently

from depression. In distinguishing the two syndromes,

symptoms of sadness and feelings of helplessness,

hopelessness, and worthlessness are helpful in

attribut-ing the case to depression. Accurately differentiatattribut-ing

apathy from depression is basic to achieve appropriate

family education, thus allowing the institution of the

best indicated treatment strategy (4).

Another important aspect in elderly patients with

MDD is the partial androgen deficiency of aging men

(PADAM). It results in a variety of behavioral

symp-toms, like weakness and increased fatigability,

depres-sive mood, lack of motivation, low energy, reduced

per-formance at job and sports, reduced vitality, increased

anxiety and irritability, insomnia, difficulty in

concen-trating, and impaired memory. Decreased libido and

low dominance may reflect reduced testosterone

lev-els; in fact, the syndrome may be reversed through

ex-ogenous testosterone supply (5-7). Psychological and

behavioral aspects of PADAM overlap with signs and

symptoms of MDD. The evidence of the association

between low testosterone (T) levels and depressive

mood in men stems from studies assessing depression

in people with hypogonadism, and reporting the

posi-concentration (C

max) of approximately 47 ng/mL with

40 mg twice-daily dosing, to 110 ng/mL with 80 mg

twice-daily dosing. Its elimination half-life is

approxi-mately 10-12 hours, while its distribution volume is

about 1640 L. Gender, smoking, age, ethnicity,

cy-tochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 genotype, liver and renal

function were all found to influence its

pharmacokinet-ics. Of these, only impaired liver or renal function

prompted specific warnings or recommendations for

dose adjustment. Drug-drug interaction studies showed

activated charcoal and CYP1A2 inhibition to

signifi-cantly decrease and increase, respectively, plasma levels

of duloxetine. For example, fluvoxamine, an SSRI and

CYP1A2 and CYP2D6 inhibitor, increased the area

under the curve of duloxetine by 460% and its C

maxby

141%. Most of the effect is due to CYP1A2 inhibition,

with CYP2D6 contributing much less. In contrast,

smoking decreases duloxetine plasma concentrations

by 30%. The CYP2D6 poor metabolizer status or

con-comitant administration of CYP2D6 inhibitors does

not require dose adjustment. Duloxetine increases the

exposure to drugs metabolized by CYP2D6, but not by

CYP1A2. Furthermore, duloxetine may enhance the

effects of benzodiazepines, but not those of alcohol or

warfarin (35). Its concentration in human plasma can

be determined by capillary electrophoresis with

laser-induced fluorescence detection (36), or by liquid

chro-matography (37); these techniques proved to be

reli-able for determining the plasma levels of other

antide-pressants (38,39) and antipsychotic drugs (40).

The aim of this paper is to briefly review the main

evidence about the treatment with duloxetine of

elder-ly people with depression.

RESULTS

The combined search yielded 212 papers as of

Sep-tember the 7

th, 2012, of which 8 were highly specific

(keywords appearing in paper title), 11 were most

rel-evant, while 128 were of some relevance. Three of the

highly relevant papers were reviews or metaanalyses

and the other eight were clinical trials. We briefly

dis-cuss their findings.

DISCUSSION

Effectiveness

Duloxetine significantly improved the mean

base-line HAM-D-17 total score of elderly patients with

de-pression (41,42). A summary of the results of studies

using duloxetine in elderly populations is shown in

Table 1.

In previous short-term studies, the comparisons

be-tween duloxetine and placebo of HAM-D-17 subscores

showed differences favoring duloxetine, which were

significant in some items (core, retardation, Maier

sub-scores) or at the limit of the level of significance in

anx-iety (strong trend, as in the study conducted by Nelson

and colleagues) (43). By the 2

ndweek of treatment, a

short-term placebo-controlled study focusing on

elder-ly patients showed significant benefits over placebo in

Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) total score and

CGI-S, and significantly greater reduction than placebo

in psychic anxiety and in the anxiety somatization

sub-scales (44). In a recent randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled trial, duloxetine was used as a

com-parator in a fixed-dose study investigating the efficacy

and safety of Lu AA21004 in elderly patients with

MDD (45). In this sponsored trial, signed by one single

principal investigator and two sponsoring

pharmaceuti-cal company employees, both drugs showed

superiori-ty to placebo at weeks 6 and 8. However, duloxetine

ranked better than the experimental drug on all clinical

measures, but the analysis model used avoided the

di-rect comparison of the two drugs (45).

Another comparison with placebo showed that

du-loxetine has a shorter time to antidepressant response

(46). Additional analysis showed that the effect of

du-loxetine on depression and quality of life was not

sig-nificantly affected by the presence of comorbid

vascu-lar disease, diabetes, arthritis or a combination of more

than one of the above (41,47).

Regarding anxiety, another study conducted by

Davidson and colleagues (48), who pooled

acute-phase data from a subset of patients (≥65 years) with

METHOD

From the 3rdto the 7thof September, current year, we

searched the Medline, Embase, and PsycLIT databases us-ing as terms “duloxetine”, “elderly”, “depression”, “agus-ing” or “ageing”, “aged”, “major depression”, “major depres-sive disorder”, and “major depresdepres-sive episode”. Papers were included if they satisfied standards for adequate methodology and population included and had focused on the subject. Exclusion criteria comprised inadequate methodology (method unspecified and/or inadequately described), not reporting data of treatment efficacy or side effects, and unspecified inclusion of subjects.

Papers published in peer-reviewed journals dealing with duloxetine treatment in elderly people were selected. Almost all of these were published in the last 10 years. Fur-ther papers that did not appear in the above databases were searched from reference lists of retrieved papers.

Table 1. Summary of studies of duloxetine in elderly populations with major depressive disorder

Study Patients Study design Primary

efficacy measures Secondary efficacy measures Main results Wohlreich et al. (51) Patients with MDD (DSM-IV) Age ≥65 years N=101 Multinational, open-label study 52 weeks Duloxetine Dosage 80-120 mg HAMD17 total score CGI-S HAMD17 subscales BDI-II PGI-I SDS

Mean changes in HAMD17 total score at Weeks 6, 28, and 52 were -13.0, -17.4 and -17.5 (all p-values <.001). Significant improvement (p<.001) in CGI-S and PGI-I at Week 1 and sustained throughout the study. Response rates at Weeks 6, 28, and 52: 62.9%, 84.9%, and 89.4%, respectively; Rates of remission were 41.4%, 69.8%, and 72.3%, respectively. Adverse events led to discontinuation in 27 (26.7%) patients. Treatment-emergent adverse events reported by >10% of patients included dizziness, nausea, constipation, somnolence, insomnia, dry mouth, and diarrhea. Most events occurred early in the study. Mean changes at endpoint in blood pressure and body weight were less than 2.0 mm Hg, and -0.1 kg, respectively. Nelson et al. (43) Patients with MDD (DSM-IV) Age ≥55 N=90

Two identical, multicenter, double-blind studies in which patients with MDD were randomized to receive placebo (N=43) or duloxetine (60 mg/day; N=47) for 9 weeks

HAMD17 total score

VAS Duloxetine resulted significantly superior to placebo for mean change in HAMD17 total score. Estimated remission for duloxetine-treated patients (44.1%) was significantly higher than that for placebo (16.1%). Reductions in overall pain, back pain, and pain while awake were also significantly greater for duloxetine than placebo. The rate of discontinuation due to adverse events was significantly higher for duloxetine-treated patients (21.0%) than placebo (6.7%). Abnormal elevations in vital signs at endpoint were not significantly different from placebo. Raskin et al. (44) Patients with MDD (DSM-IV) Age: 65-89 N=311 Multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study: 1-week screening phase; 1-week, double-blind, placebo 8-weeks duloxetine 60 mg/day (n=207) or placebo (n=104)

1-week, double-blind, discontinuation phase in which the dosage of duloxetine was tapered to 30 mg/day for 4 days.

VLRT SDST 2DCT LNST GDS HAMD17 CGI-S VAS SF-36

As compared to placebo, Duloxetine improved the composite cognitive score, GDS and HAMD17 total scores, CGI-Severity, HAMD17 response and remission rates.

Duloxetine significantly improved Visual Analogue Scale scores for back pain and time in pain while awake versus placebo.

Significantly fewer patients withdrew from the study because of lack of efficacy (2.9% versus 9.6%); the incidences of discontinuation due to adverse events were similar for duloxetine

and placebo (9.7% versus 8.7%)

Russell et al. (49) Patients with MDD (DSM-IV) Age: ≥65 N=311 Post-hoc analyses of a multicenter, parallel, double-blind, placebo-controlled study by Raskin et al., 2007 Psychic Anxiety item, Somatic Anxiety item, and Anxiety-Somatization subscale from HAMD17

Psychic Anxiety item, So-matic Anx-iety item, and Anxi- ety-Somati-zation sub-scale from HAMD17 GDS VAS VLRT SDST 2DCT LNST

Duloxetine vs. Placebo significantly reduced Psychic Anxiety (least-squares mean change: -0.62 vs. -0.18, p<0.001) and Anxiety/Somatization subscale (-1.88 vs. -0.99, p=0.002). Significant improvement occurred in the <75 and ≥75 age groups for Psychic Anxiety, but only in the <75 group for the

Anxiety/Somatization subscale.

Duloxetine-treated patients with high anxiety showed significant improvement compared with placebo-treated patients on Psychic Anxiety, Anxiety/Somatization subscale, the HAMD17 total score, and several other measures.

Duloxetine and placebo had similar discontinuation due to adverse events.

Wise et al. (64) Patients with MDD (DSM-IV) Age: ≥65 N=311 Post-hoc analyses of a multicenter, parallel, double-blind, placebo-controlled study by Raskin et al., 2007 VLRT SDST 2DCT LNST GDS HAMD17 CGI-S VAS SF-36

Duloxetine vs. Placebo proved significantly greater efficacy for the composite cognitive score, GDS and HAMD17 total scores, CGI-S, HAMD17 response and remission rates, and some of the SF-36 and VAS measures.

Few treatment-by-comorbidity subgroup interactions for efficacy variables or for adverse events reported as the reason for discontinuation and common treatment emergent adverse events. The efficacy of duloxetine on cognition and depression in elderly patients, and its tolerability, were not largely affected by the comorbidity status.

Continue Table 1.

Study Patients Study design Primary efficacy measures Secondary efficacy measures Main results Karp et al. (52) Patients with MDD (DSM-IV) Age: ≥65 N=274 HAM-D-17 score ≥15, MMSE score ≥18 Data analysis of 40 patients switched from escitalopram to duloxetine Data up to 16.5 weeks HAMD17 total score HRSA MMSE UKU CIRS-G MOS

50% patients met criteria for full response, 17.6% were partial responders and 32.5% did not respond. The median time to response was 12 weeks. 17, 85% responders were females, whereas responders and non-responders did not differ in terms of age, marital status, education, recurrent depression, age on onset of the first depressive episode

Raskin et al. (61) Patients with MDD (DSM-IV) Age: ≥65 N=311 Post-hoc analyses of a multicenter, parallel, double-blind, placebo-controlled study by Raskin et al., 2007 GDS HAMD17 CGI-S VAS The time to response and remission for duloxetine compared with placebo was evaluated using Cox proportional hazards (PH) modeling, Kaplan-Meier estimation, and categorical repeated measures analysis

Discontinuation rates due to adverse events were similar for duloxetine and placebo (9.7% vs 8.7%). Treatment-emergent dry mouth, nausea, and diarrhea occurred significantly (p≤0.05) more frequently with duloxetine. Changes in supine and standing blood pressure, in sustained elevation in BP and treatment-emergent orthostatic hypotension, in pulse and in corrected QT (QTc) interval were not significantly different between duloxetine and placebo, except for change in orthostatic systolic BP (-2.45 vs 0.93 mmHg; p=.017). The duloxetine group showed significant weight loss compared with the placebo group (-0.73 kg vs -0.13 kg; p=0.009). Of 5 hepatic analytes, the only significant difference was an increase in alkaline phosphatase in duloxetine compared with placebo (p=0.017); this difference was not considered clinically relevant. The incidence of 1 or more discontinuation-emergent adverse events was not significantly different between the duloxetine and placebo groups (17.3% vs 11.3%).

Katona et al. (45) Patients with MDD (DSM-IV-TR) Age: ≥65 N=452 MMSE ≥24 Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) ≥26 Multicenter, 8-week, 1:1:1 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial vs. Lu AA21004 Duloxetine 60 mg/day vs. Lu AA21004 5 mg/day or placebo HAMD24 total score at week 8 with analysis of covariance with last observation carried forward and with mixed model for repeated measures Response and remission; HAMD24 at all points; Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale scores; CGI-S scores; Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; Digit Symbol Substitution Test

Duloxetine and Lu AA21004 showed significantly greater improvement vs placebo at weeks 6 and 8. Covariance and mixed-model effects converged. Lu AA21004, but not duloxetine, positively affected cognition.

According to the HAMD, 8-week response was found in 35.2% of patients receiving placebo, 53.2% of patients receiving Lu AA21004, and in 63.3% of patients receiving duloxetine, while remitters were respectively 19.3%, 29.2%, and 34.7%.

Lu AA21004 differed for one adverse event from placebo, while duloxetine differed for six.

Robinson et al. (50) Patients with MDD (DSM-IV) Age: ≥65 N=279 MMSE ≥20 Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale ≥20 Multicenter, 24-week (12-24-week short-term and 12-week continuation), randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial Duloxetine 60 or 120 mg/day or placebo; placebo rescue possible HAMD17 total score GDS BPI NRS CGI-S PGI-I cognitive measures

Duloxetine vs placebo showed significantly greater improvement at weeks 4, 8, 16, and 20. Similar patterns for Geriatric Depression Scale and Clinical Global Impression-Severity scale emerged, with significance also seen at week 24.

There was a significant treatment effect for all BPI items and 4 of 6 NRS pain measures in the acute phase, most BPI items and half of the NRS measures in the continuation phase.

More duloxetine-treated patients completed the study (63% versus 55%). A significantly higher percentage of duloxetine-treated patients versus placebo discontinued due to adverse event (15.3% versus 5.8%)

Legend: 2DCT: 2 Digit Cancellation Test; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; BPI: Brief Pain Inventory; CGI-S: Clinical Global

Impres-sion of Severity scale; DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition; GDS: Geriatric DepresImpres-sion Scale; CIRS-G: Cumulative Illness Rating Scale for Geriatrics; HAMD17: 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; HRSA: Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; LNST: Letter-Number Sequencing Test; MDD: Major Depressive Disorder; MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination; MOS: Medical Outcomes Study; NRS: Numeric Rating Scales for pain; PGI-I: Patient Global Impression of Improvement scale; SDS: Sheehan Dis-ability Scale; SDST: Symbol Digit Substitution Test; SF-36: 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; UKU: Udvalg for Kliniske Undersogelser-Committee of Clinical Investigations Side Effect Rating Scale; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale for pain; VLRT: Verbal Learning and Recall Test.

generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) from four

ran-domized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of

du-loxetine (three using flexible dosing and one using

fixed doses), showed duloxetine 60-120 mg once daily

for 9-10 weeks to be efficacious and tolerable in

elder-ly patients with generalized anxiety disorder, as

com-pared to placebo. It should be remarked that GAD is

a disorder with much symptomatological overlap with

depressive mood disorders which responds in a similar

manner to antidepressant drugs.

Briefly, short-term studies indicate that duloxetine

treatment in aged people with depression improves

depressive symptoms, as assessed through the total

score on the 17-item HAM-D. Furthermore, it reduces

generalized, psychic, and somatization anxiety (43,48,

49). Duloxetine is faster than placebo to show

antide-pressant response and is also effective when there are

comorbid vascular diseases, diabetes, arthritis or more

than one of these.

In a recent multicenter, multinational, 24-week

(12-week short-term and 12-(12-week continuation),

random-ized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial carried-out

by Robinson et al. (50), patients who received

duloxe-tine showed significantly greater improvement on the

Hamilton’s Maier subscale at weeks 4, 8, 16, and 20.

Furthermore, duloxetine-receiving patients had

signif-icantly lower pain ratings during both the acute and

the continuation phases, but dropped-out three times

as much as their placebo-receiving counterparts.

Long-term data showed that duloxetine maintains

its efficacy over time; HAM-D-17 total score and all

subscales significantly improved up to the 52

ndweek

(51). CGI-S improvement in elderly patients paralleled

that of the remaining included population of

non-eld-erly adults.

Another long-term study showed that 50% of

pa-tients who switched from escitalopram to duloxetine

met criteria for full response, 17.6% of them were

par-tial responders and 32.5% did not respond (52). The

median time to response was 12 weeks. Female gender

was associated with a higher probability of response,

whereas other measures, like history of depression and

baseline MMSE scores did not affect the rate of

re-sponse. Psychological and somatic anxiety improved

over time following treatment with duloxetine (52).

The improvement of depressive symptoms with

dulox-etine was dissimilar to improvements obtained with

placebo, while escitalopram induced changes that

looked like those of placebo-treated patients (53).

Duloxetine proved to be effective also in pain relief

and urinary incontinence (54). In a short-term,

place-bo-controlled study, patients experienced rapid pain

relief, and the comparison versus placebo showed

sta-tistically significant differences in scores on the visual

analogue scale (VAS) pain ratings, in back pain, and in

the amount of pain experienced while awake (55).

Fur-thermore, patients showed faster improvement in

self-reported pain compared to placebo (56). Moreover,

duloxetine produced significant reduction in overall

pain severity, back pain, time in pain while awake, and

interference with daily activities in patients with

de-pression and comorbid arthritis (57). Briefly, the

bene-ficial effects of duloxetine on pain were statistically

significant and clinically meaningful, extending from

the acute to the continuation phase, thus prompting to

hypothesize that they are not subjected to tolerance

with time (50).

In an eight-week, placebo-controlled study (44),

treatment with duloxetine ensued in significant

im-provement, compared to placebo, on the composite

measure of cognitive functions; duloxetine proved to

be the most important determinant of the

improve-ment driven by verbal learning and memory; on the

other hand, measures of focused attention and

execu-tive functioning showed no significant differences

be-tween duloxetine and placebo.

Duloxetine was found to be effective in patients

with urinary stress incontinence (54); however, it may

be associated with a decline in urinary flow in elderly

men (55). At any rate, duloxetine is a safe and effective

treatment for elderly women with symptoms of stress

urinary incontinence or stress-predominant mixed

nary incontinence (56), with elderly women with

uri-nary incontinence showing a safety profile for

duloxe-tine which was comparable to that of their younger

counterparts (57). Duloxetine is also effective in other

pathological conditions of the aged, including

fi-bromyalgia (58), osteoarthritis (47,59), and diabetic

sensory polyneuropathy (60).

Effects on physiological functions

The changes from baseline of heart rate and

stand-ing and supine blood pressure, sustained

hyperten-sion and the number of patients with abnormal

changes did not differ significantly between the

du-loxetine- and placebo-treated patients (44,61). The

rate of treatment-emergent orthostatic hypotension,

defined as standing diastolic blood pressure (BP) at

least 10 mmHg less than supine diastolic BP and

standing systolic BP at least 20 mmHg than supine

systolic BP, was numerically higher in the placebo

group compared to the duloxetine group, though this

did not reach statistical significance. Using an

ortho-static change of 10 mmHg for both systolic and

dias-tolic BP, the rates of treatment-emergent orthostatic

hypotension were similar and not significantly

differ-ent between duloxetine- and placebo-treated

pa-tients, for both diastolic and systolic BP. No

signifi-cant differences in mean changes of QTc interval has

been detected between duloxetine- and

placebo-treated patients, independently from whether the

Bazett or the Fridericia formulas were used (61). In

the analysis at the one-year follow-up,

duloxetine-treated patients exhibited small and nonsignificant

decreases in blood pressure and increases in heart

rate from baseline to end point (51). Patients with

higher baseline BP values had comparatively greater

BP lowering effects, as compared with normotensive

individual. Duloxetine did not appear to prolong the

QTc interval in the elderly, and this is consistent with

what has already been published for nonelderly

pa-tients and healthy volunteers (62,63).

Treatment with duloxetine was associated with a

small (<1 kg) decrease in weight in the short-term.

However, mean body weight slightly increased after

one year, whereas the rate of patients with significant

weight gain was not less than that of patients with

sig-nificant weight decrease (41). Considered cumulatively,

these data do not clarify whether duloxetine increases

or decreases body weight; the drug apparently affects

body weight, albeit in an unpredictable direction.

In the short-term comparative analysis, no

signifi-cant differences between duloxetine and placebo

emerged concerning the incidence of abnormal

labora-tory values (hematology and blood chemistry).

Long-term data did not show clinically significant

abnormal-ities (41).

Duloxetine did not affect sexual function

different-ly from placebo in elderdifferent-ly people, as assessed with the

Arizona Sexual Experience Scale (43). This is

impor-tant, as the presence of sexual alterations are not to be

considered a minor point in such populations, given

their possible repercussions on self-esteem and the

consequent influence on suicidal behavior (13).

Adverse events

Although the rate of discontinuation due to adverse

events in the short-term pooled data (61) was higher in

patients receiving duloxetine than in those on placebo,

direct head-to-head comparisons did not show any

dif-ference in the entire patient sample (9.7% vs 8.7%;

NS), even when the sample was dichotomized in a

<75-year-old and a ≥75-<75-year-old subgroup (44,61). Rates of

dry mouth, nausea and diarrhea were significantly

high-er in patients receiving duloxetine, as compared to

pa-tients receiving placebo. Nausea and fatigue showed

significant heterogeneity when data were analyzed

ac-cording to an age-related stratification (<75 years-old

and ≥75 years-old). In the <75 subgroup, nausea was

significantly more frequent in duloxetine-treated

pa-tients, whereas in the ≥75 subgroup, nausea was more

frequent in the placebo subgroup. Fatigue was

signifi-cantly more frequent for duloxetine-treated patients in

the ≥75 subgroup (61). There was a statistically

signifi-cant greater mean decrease in weight for patients

treat-ed with duloxetine versus patients treattreat-ed with placebo

(-0.73 vs -0.13 kg; p=0.009) (39). Post hoc analyses of

this study also showed duloxetine to be very well

toler-ated in patients with medical comorbidities (64). Dry

mouth and gastrointestinal complaints were the

ad-verse events that were significantly more common with

duloxetine than with placebo in the short-term direct

comparison (44), irrespective of the occurrence of

co-morbidities (64). Other types of adverse events (e.g.,

in-somnia, fatigue, diminished appetite, and reduced

li-bido) in the pooled short-term data (43) were seen

sig-nificantly more often in patients receiving duloxetine,

as compared with those receiving placebo.

Long-term observation showed that most adverse

events occurred early in the study and were of mild or

moderate intensity (51). The rates of events in patients

aged ≥65 years were not significantly higher than in the

18-64 year age range in the same study. In the

compar-ison between age ranges, patients aged ≥65 years

re-ported a significantly lower incidence of insomnia and

headache than younger patients, while no significant

differences between age cohorts were found in the

analysis of all other side effects.

Five (12.5%) patients who switched from

escitalo-pram to duloxetine (52) discontinued the study due

to adverse events. In the analysis of total and

sub-scale scores of the Udvalg Kliniske Undersøgelser

(UKU) scale (65), there were small but statistically

significant decreases (i.e., improvements) in somatic

complaints (as reflected by the total UKU scores),

on the psychological subscale and other systems

sub-scale scores.

Considering the lack of evidence concerning

suici-dal risk in elderly patients with depression receiving

duloxetine, a careful assessment of suicide risk is

es-sential in this category of patients.

The literature reports the following common side

ef-fects associated with duloxetine overdose: nausea,

headache, dry mouth, fatigue, insomnia, dizziness,

som-nolence, constipation, considerable increases in

recum-bent systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and a small

decrease in heart rate (66,67). A review of the annual

reports of the American Association of Poison Control

Centers (AAPCC) shows that there has been an

in-crease in fatal cases in which duloxetine has been

iden-tified: 5 cases in 2005 (68), 11 cases in 2006 (69), 14

cas-es in 2007 (70), 18 cascas-es in 2008 (71), 23 cascas-es in 2009

(72), and 12 in 2010 (73). “Cocktail” drugs caused most

of the poisonings; only a few cases of poisoning were

due to duloxetine alone, which somehow has been

linked to pulmonary embolism (74). However, this

ap-parent increase in duloxetine mortality in the US

should be viewed against the background of the

in-creased use of the drug across the year, hence the

above figures were to be expected and are by no means

excessive with respect to other similar drugs. The recent

decrease in duloxetine-associated mortality is to be

in-terpreted as the result of preventive policies and

cam-paigns carried-out by the US health administration.

The ingestion of high quantities of duloxetine may

have serious outcomes such as complicating

throm-boembolism (75). Elderly patients who are taking

du-loxetine should be advised to avoid overdosage, which

in most cases may be attributed to careless ingestion

by cognitively impaired individuals with depression.

Patients should be prompted to rely on family

mem-bers for the control of their medication intake and

en-couraged to promptly contact their physician in cases

of inadvertent drug ingestion, so to institute timely

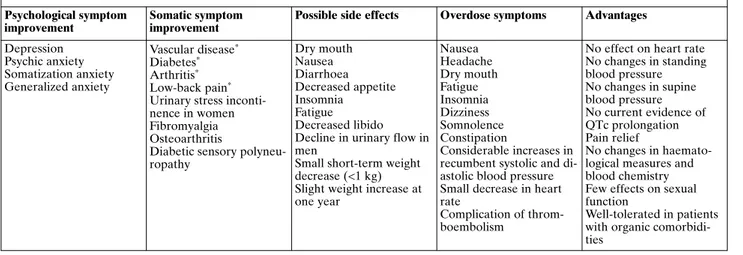

detoxifying strategies and interventions. A summary of

the strength and weaknesses of duloxetine use in the

aged is shown in

Table 2.

CONCLUSIONS

Duloxetine is effective, safe and well-tolerated in

elderly populations with depressive disorders in a

sim-ilar manner to adults. Its’ efficacy is simsim-ilar to that of

other antidepressants, like the SSRIs or other SNRIs,

like venlafaxine and milnacipran, although regretfully,

comparisons in elderly populations are lacking. It

might have some advantage with respect to SSRIs, in

terms of dissimilarity with respect to placebo.

Howev-er, there is a relative lack of studies of duloxetine in

aged patients with depressive disorders. Elderly

pa-tients with dementia or pseudodementia must be

closely followed to avoid inappropriate dosing, as this

may expose patients to life-threatening effects.

Acknowledgements. We are grateful to Ms. Mimma Ariano, the late Tiziana Mattei, and Ms. Felicia Proietti, Librarians of the Sant’Andrea Hospital, School of Medicine and Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome, for allowing us to access precious bibliographical material. We also thank Ms. Lucilla Martinelli for skillful assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Financial & Competing Interests Disclosure. In the past two years, Paolo Girardi has received research support from Lilly, Janssen, and Springer Healthcare, and has participated in Advisory Boards for Lilly, Otsuka, Pfizer, Schering, and Springer Healthcare and received honoraria from Lilly and Springer Healthcare. All other authors of this paper have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organ-ization or entity with a financial interest in, or financial con-flict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, hono-raria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

This work has not been supported by any funding.

REFERENCES

1. Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2003; 58: 249-65.

Table 2. Summary of the effects (and the lack of them) of the use of duloxetine in elderly patients Psychological symptom

improvement

Somatic symptom improvement

Possible side effects Overdose symptoms Advantages Depression Psychic anxiety Somatization anxiety Generalized anxiety Vascular disease* Diabetes* Arthritis* Low-back pain* Urinary stress inconti-nence in women Fibromyalgia Osteoarthritis

Diabetic sensory polyneu-ropathy Dry mouth Nausea Diarrhoea Decreased appetite Insomnia Fatigue Decreased libido Decline in urinary flow in men

Small short-term weight decrease (<1 kg) Slight weight increase at one year Nausea Headache Dry mouth Fatigue Insomnia Dizziness Somnolence Constipation Considerable increases in recumbent systolic and di-astolic blood pressure Small decrease in heart rate

Complication of throm-boembolism

No effect on heart rate No changes in standing blood pressure No changes in supine blood pressure No current evidence of QTc prolongation Pain relief No changes in haemato-logical measures and blood chemistry Few effects on sexual function

Well-tolerated in patients with organic comorbidi-ties

2. Clarfield AM. The reversible dementias: do they reverse? Ann Intern Med 1988; 109: 476-86.

3. Kobayashi T, Kato S. Depression-dementia medius: between de-pression and the manifestation of dementia symptoms. Psy-chogeriatrics 2011; 11: 177-82.

4. Tagariello P, Girardi P, Amore M. Depression and apathy in de-mentia: same syndrome or different constructs? A critical re-view. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2009; 49: 246-9.

5. Amore M. Partial androgen deficiency and neuropsychiatric symptoms in aging men. J Endocrinol Invest 2005; 28 (11 suppl proceedings): 49-54.

6. Amore M, Scarlatti F, Quarta AL, Tagariello P. Partial androgen deficiency, depression and testosterone treatment in aging men. Aging Clin Exp Res 2009; 21: 1-8.

7. Amore M, Innamorati M, Costi S, Sher L, Girardi P, Pompili M. Partial androgen deficiency, depression, and testosterone sup-plementation in aging men. Int J Endocrinol 2012; 2012: 280724. 8. Amore M, Di Donato P, Berti A, et al. Sexual and psychological symptoms in the climacteric years. Maturitas 2007; 56: 303-11. 9. Dennerstein L, Soares CN. The unique challenges of managing

depression in mid-life women. World Psychiatry 2008; 7: 137-42. 10. Zanardi R, Rossini D, Magri L, Malaguti A, Colombo C, Smeral-di E. Response to SSRIs and role of the hormonal therapy in post-menopausal depression. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2007; 17: 400-5.

11. Pompili M, Innamorati M, Masotti V, et al. Suicide in the elder-ly: a psychological autopsy study in a North Italy area (1994-2004). Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008: 727-35.

12. Innamorati M, Tamburello A, Lester D, et al. Inequalities in sui-cide rates in the European Union’s elderly: trends and impact of macro-socioeconomic factors between 1980 and 2006. Can J Psy-chiatry 2010; 55: 229-38.

13. Klug A, Lindner R, Fiedler G, Altenhöfer A. Sexualität suizidaler Älterer. Z Gerontol Geriatr 2008; 41: 22-8.

14. Albers B, Kruse J, Giani G, Icks A. Diabetes and incident de-pression: Is the association mediated or modified by sociodemo-graphic factors or co-morbidities? A systematic review. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2011; 119: 591-8.

15. Dziemidok P, Makara-Studzi_ska M, Jarosz MJ. Diabetes and depression: a combination of civilization and life-style diseases is more than simple problem adding. Literature review. Ann Agric Environ Med 2011; 18: 318-22.

16. García-Fabela L, Melano-Carranza E, Aguilar-Navarro S, Gar-cía-Lara JM, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, Avila-Funes JA. Hyper-tension as a risk factor for developing depressive symptoms among community-dwelling elders. Rev Invest Clin 2009; 61: 274-80.

17. Saran RK, Puri A, Agarwal M. Depression and the heart. Indian Heart J 2012; 64: 397-401.

18. Apostolopoulou M, Savopoulos C, Michalakis K, Coppack S, Dardavessis T, Hatzitolios A. Age, weight and obesity. Maturitas 2012; 71: 115-9.

19. Han TS, Tajar A, Lean ME. Obesity and weight management in the elderly. Br Med Bull 2011; 97: 169-96.

20. Stanger O, Fowler B, Piertzik K, et al. Homocysteine, folate and vitamin B12 in neuropsychiatric diseases: review and treatment recommendations. Expert Rev Neurother 2009; 9: 1393-412. 21. Wolters M, Ströhle A, Hahn A. Cobalamin: a critical vitamin in

the elderly. Prev Med 2004; 39: 1256-66.

22. Annweiler C, Souberbielle JC, Schott AM, de Decker L, Berrut G, Beauchet O. Vitamine D chez la personne agée: les 5 points à retenir. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil 2011; 9: 259-67. 23. Parker G, Brotchie H. “D” for depression: any role for vitamin

D? “Food for Thought” II. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011; 124: 243-9.

24. Fava M, Mischoulon D. Folate in depression: efficacy, safety, dif-ferences in formulations, and clinical issues. J Clin Psychiatry 2009; 70 (suppl 5): 12-7.

25. Bottiglieri T. Homocysteine and folate metabolism in depres-sion. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2005; 29: 1103-12.

26. Kuo HK, Sorond FA, Chen JH, Hashmi A, Milberg WP, Lipsitz LA. The role of homocysteine in multisystem age-related prob-lems: a systematic review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005; 60: 1190-201.

27. Fischbach R, Gastager H, Harrer G. Hyposideremia and en-dogenous depression. Pharmakopsychiatr Neuropsychophar-makol 1973; 6: 252-7.

28. Stewart R, Hirani V. Relationship between depressive symp-toms, anemia, and iron status in older residents from a national survey population. Psychosom Med 2012; 74: 208-13.

29. Cutler P. Iron overload in psychiatric illness. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148: 147-8.

30. Cutler P. Iron overload and psychiatric illness. Can J Psychiatry 1994; 39: 8-11.

31. Feifel D, Young CW. Iron overload among a psychiatric outpa-tient population. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58: 74-8.

32. Serata D, Del Casale A, Rapinesi C, et al. Hemochromatosis-in-duced bipolar disorder: a case report. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2012; 34: 101.e1-3.

33. Kaplan BJ, Crawford SG, Field CJ, Simpson JS. Vitamins, miner-als, and mood. Psychol Bull 2007; 133: 747-60.

34. Girardi P, Pompili M, Innamorati M, et al. Duloxetine in acute major depression: review of comparisons to placebo and stan-dard antidepressants using dissimilar methods. Hum Psy-chopharmacol 2009; 24: 177-90.

35. Knadler MP, Lobo E, Chappell J, Bergstrom R. Duloxetine: clin-ical pharmacokinetics and drug interactions. Clin Pharma-cokinet 2011; 50: 281-94.

36. Musenga A, Amore M, Mandrioli R, Kenndler E, de Martino L, Raggi MA. Determination of duloxetine in human plasma by capillary electrophoresis with laser-induced fluorescence detec-tion. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2009; 877: 1126-32.

37. Mercolini L, Mandrioli R, Cazzolla R, Amore M, Raggi MA. HPLC analysis of the novel antidepressant duloxetine in human plasma after an original solid-phase extraction procedure. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2007; 856: 81-7. 38. Mandrioli R, Mercolini L, Cesta R, Fanali S, Amore M, Raggi

MA. Analysis of the second generation antidepressant venlafax-ine and its main active metabolite O-desmethylvenlafaxvenlafax-ine in human plasma by HPLC with spectrofluorimetric detection. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 2007; 856: 88-94. 39. Musenga A, Kenndler E, Mercolini L, Amore M, Fanali S, Rag-gi MA. Determination of sertraline and N-desmethylsertraline in human plasma by CE with LIF detection. Electrophoresis 2007; 28: 1823-31.

40. Saracino MA, Amore M, Baioni E, Petio C, Raggi MA. Deter-mination of selected phenotiazines in human plasma by solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography with coulometric detection. Analytica Chimica Acta 2008; 624: 308-16.

41. Mancini M, Gianni W, Rossi A, Amore M. Duloxetine in the management of elderly patients with major depressive disorder: an analysis of published data. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2009; 10: 847-60.

42. Tarolla E, Brugnoli R, Pancheri P. Duloxetina: efficacia clinica, sicurezza e tollerabilità nel trattamento del disturbo depressivo maggiore. Giorn Ital Psicopatol 2007; 13: 258-78.

JG, Kennedy JS. Duloxetine for the treatment of major depres-sive disorder in older patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005; 13: 227-35.

44. Raskin J, Wiltse CG, Siegal A, et al. Efficacy of duloxetine on cognition, depression, and pain in elderly patients with major depressive disorder: an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-con-trolled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 900-9.227-35.

45. Katona C, Hansen T, Olsen CK. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced, fixed-dose study comparing the efficacy and safety of Lu AA21004 in elderly pa-tients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2012; 27: 215-23.

46. Raskin J, Xu JY, Kajdasz DK. Time to response for duloxetine 60 mg once daily versus placebo in elderly patients with major de-pressive disorder. Int Psychogeriatr 2008; 20: 309-27.

47. Wohlreich MM, Sullivan MD, Mallinckrodt CH, et al. Duloxe-tine for the treatment of recurrent major depressive disorder in elderly patients: treatment outcomes in patients with comorbid arthritis. Psychosomatics 2009; 50: 402-12.

48. Davidson J, Allgulander C, Pollack MH, et al. Efficacy and toler-ability of duloxetine in elderly patients with generalized anxiety disorder: a pooled analysis of four randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Hum Psychopharmacol 2008; 23: 519-26.

49. Russell J, Raskin J, Wiltse C, Walker D, Brawman-Mintzer O. Ef-ficacy and tolerability of duloxetine treatment in elderly patients with major depressive disorder and concurrent anxiety symp-toms. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007; 4: 33-45.

50. Robinson M, Oakes TM, Raskin J, Liu P, Shoemaker S, Nelson JC. Acute and long-term treatment of late-life major depressive disorder: duloxetine versus placebo. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2012 Jul 21. Epub ahead of print, doi: 10.1097/JGP. 0b013e 31825d08f1.

51. Wohlreich MM, Mallinckrodt CH, Watkin JG, Hay DP. Duloxe-tine for the long-term treatment of major depressive disorder in patients aged 65 and older: an open-label study. BMC Geriatr 2004; 4: 11.

52. Karp JF, Whyte EM, Lenze EJ, et al. Rescue pharmacotherapy with duloxetine for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor non-responders in late-life depression: outcome and tolerability. J Clin Psychiatry 2008; 69: 457-63.

53. Dolder C, Nelson M, Stump A. Pharmacological and clinical profile of newer antidepressants: implications for the treatment of elderly patients. Drugs Aging 2010; 27: 625-40.

54. Patel-Gadhia R, Bhal K, Patil P. Retrospective audit on tolera-bility and efficacy of duloxetine for stress urinary incontinence. J Obstet Gynaecol 2011; 31: 258-9.

55. Wade AG, Crawford GM. Urinary flow and urinary symptoms in elderly males exposed to either escitalopram or duloxetine. Curr Med Res Opin 2010; 26: 1031-5.

56. Schagen van Leeuwen JH, Lange RR, Jonasson AF, Chen WJ, Viktrup L. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine in elderly women with stress urinary incontinence or stress-predominant mixed urinary incontinence. Maturitas 2008; 60: 138-47.

57. Skinner MH, Kuan HY, Skerjanec A, et al. Effect of age on the pharmacokinetics of duloxetine in women. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2004; 57: 54-61.

58. Cui Z, Zhao Y, Novick D, Faries D. Predictors of duloxetine ad-herence and persistence in patients with fibromyalgia. J Pain Res 2012; 5: 193-201.

59. Abou-Raya S, Abou-Raya A, Helmii M. Duloxetine for the management of pain in older adults with knee osteoarthritis:

randomised placebo-controlled trial. Age Ageing 2012; 41: 646-52.

60. Zilliox L, Russell JW. Treatment of diabetic sensory polyneu-ropathy. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2011; 13: 143-59.

61. Raskin J, Wiltse CG, Dinkel JJ, Walker DJ, Desaiah D, Katona C. Safety and tolerability of duloxetine at 60 mg once daily in eld-erly patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychophar-macol 2008; 28: 32-8.

62. Wernicke J, Lledó A, Raskin J, Kajdasz DK, Wang F. An evalua-tion of the cardiovascular safety profile of duloxetine: findings from 42 placebo-controlled studies. Drug Saf 2007; 30: 437-55. 63. Thase ME, Tran PV, Wiltse C, Pangallo BA, Mallinckrodt C,

De-tke MJ. Cardiovascular profile of duloxetine, a dual reuptake in-hibitor of serotonin and norepinephrine. J Clin Psychopharma-col 2005; 25: 132-40.

64. Wise TN, Wiltse CG, Iosifescu DV, Sheridan M, Xu JY, Raskin J. The safety and tolerability of duloxetine in depressed elderly pa-tients with and without medical comorbidity. Int J Clin Pract 2007; 61: 1283-93.

65. Lingjærde O, Ahlfors UG, Bech P, et al. The UKU Side Effect Rating Scale: a new comprehensive rating scale for psychotrop-ic drugs, and a cross-sectional study of side effects in neurolep-tic-treated patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1987; Suppl 76: 1-100. 66. Baselt RC. Disposition of toxic drugs and chemicals in man, 8th

ed. Foster City (CA) USA: Biomedical Publications, 2008. 67. Sharma A, Goldberg MJ, Cerimele BJ. Pharmacokinetics and

safety of duloxetine, a dual-serotonin and norepinephrine reup-take inhibitor. J Clin Pharmacol 2000; 40: 161-7.

68. Lai MW, Klein-Schwartz W, Rodgers GC, et al. 2005 Annual Re-port of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ na-tional poisoning and exposure database. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2006; 44: 803-932.

69. Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, Green J, Rumack BH, Heard SE. 2006 Annual Report of the American Associa-tion of Poison Control Centers’ NaAssocia-tional Poison Data System (NPDS). Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2007; 45: 815-917.

70. Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, Green JL, Rumack BH, Heard SE; American Association of Poison Control Cen-ters. 2007 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 25th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2008; 46: 927-1057. 71. Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, Green JL, Rumack

BH, Giffin SL. 2008 Annual Report of the American Associa-tion of Poison Control Centers’ NaAssocia-tional Poison Data System (NPDS): 26th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2009; 47: 911-1084.

72. Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, Green JL, Rumack BH, Giffin SL. 2009 Annual Report of the American Associa-tion of Poison Control Centers’ NaAssocia-tional Poison Data System (NPDS): 27th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2010; 48: 979-1178.

73. Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, Green JL, Rumack BH, Dart RC. 2010 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 28th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2011; 49: 910-41.

74. Anderson D, Reed S, Lintemoot J, et al. A first look at duloxe-tine (Cymbalta) in a postmortem laboratory. J Anal Toxicol 2006; 30: 576-80.

75. Mari F, Gualco B, Rensi R, Bertol E. Acute massive pulmonary thromboembolism due to acute intoxication by duloxetine: a case report. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2012; 12: 258-62.