TECHNOLOGIES

DRUG DISCOVERY

TODAY

Evaluation

of

symptomatic

drug

effects

in

Alzheimer’s

disease:

strategies

for

prediction

of

efficacy

in

humans

J.

Deguil

1

,

L.

Ravasi

1

,

A.

Auffret

2

,

a

,

C.

Babiloni

3

,

4

,

D.

Bartres

Faz

5

,

V.

Bragulat

6

,

C.

Casse´-Perrot

2

,

V.

Colavito

7

,

M.T.

Herrero

Ezquerro

8

,

Y.

Lamberty

9

,

L.

Lanteaume

2

,

D.

Pemberton

10

,

F.

Pifferi

11

,

J.C.

Richardson

6

,

E.

Schenker

12

,

O.

Blin

13

,

E.

tarragon

8

,

R.

Bordet

1

,

*

1

UniversityLilleNorddeFrance,DepartmentofPharmacology,Lille,France

2

CIC-UPCET,CHULaTimone,APHM,UMRCNRSINT6193,UnivAix-Marseille,Marseille,France

3UniversityofFoggia,DepartmentofClinicalandExperimentalMedicine,Foggia,Italy 4I.R.C.C.S.S.RaffaelePisana,Rome,Italy

5DeptdePsiquiatriaiPsicobiologiaClinica,FacultatdeMedicina,UniversitatdeBarcelona&Institutd’InvestigacionsBiomediquesAugustPiSunyer(IDIBAPS)

Barcelona,Catalonia,Spain

6GlaxoSmithKline,R&DU.K.ChinaGroup,GunnelsWoodRoad,StevenageSG12NY,UK 7DepartmentofNeurologicalSciences(DSNNMM),UniversityofVerona,Italy

8Clinical&ExperimentalNeuroscience(NiCE)andCentrodeInvestigacio´nBiome´dicaenRedsobreEnfermedadesNeurodegenerativas(CIBERNED),

SchoolofMedicine,UniversityofMurcia,CampusdeEspinardo,Murcia30100,Spain

9

UCBPharmas.a.,NeuroscienceTherapeuticArea,Brainel’Alleud,Belgium

10

DepartmentofNeuroscience,JanssenResearchandDevelopment,DivisionofJanssenPharmaceuticaNV,Beerse,Belgium

11

UMR7179CentreNationaldelaRechercheScientifique,Muse´umNationald’HistoireNaturelle,Brunoy,France

12

InstitutdeRechercheServier,Paris,France

13

DiscoveryMedicine,R&DChinaGlaxoSmithKline

Inchronicdiseases such asAlzheimer’s disease(AD),

the arsenalof biomarkers available todetermine the

effectivenessofsymptomatictreatmentisverylimited.

Interpretation of the results provided in literature is

cumbersomeand it becomesdifficulttopredict their

standardizationtoalargerpatientpopulation.Indeed,

cognitive assessment alone does not appear to have

sufficient predictive value of drug efficacy in early

clinicaldevelopmentofADtreatment.Inrecentyears,

research has contributed to the emergence of new

tools to assess brain activity relying on innovative

technologies of imaging and electrophysiology.

How-ever,therelevanceoftheuseofthesenewermarkers

intreatmentresponseassessmentiswaitingfor

valida-tion. Thisreview shows how the earlyclinical

assess-ment of symptomatic drugs could benefit from the

inclusion ofsuitable pharmacodynamicmarkers.This

reviewalsoemphasizestheimportanceof

re-evaluat-ingastep-by-stepstrategyindrugdevelopment.

SectionEditor:

OscarDellaPasqua– Leiden/AmsterdamCenterforDrug Research,Leiden,TheNetherlands

Editors-in-Chief

KelvinLam–SimplexPharmaAdvisors,Inc.,Arlington,MA,USA

HenkTimmerman–VrijeUniversiteit,TheNetherlands

Animal

Pharmacology

*Correspondingauthor.:R.Bordet([email protected]) a

Currentaddress:BrainandSpineInstitute,ICM,HoˆpitaldelaSalpeˆtrie`re,Paris, France.

Introduction

Process optimization in drugdiscovery isa laborious chal-lengethatdependsprimarilyontheacceptancethata para-digm shift is needed. Despite scientific progress in the developmentprogramofdrugsforAD,somepersisting meth-odologicalissueshighlightthenecessitytodevelop innova-tivestrategiesthatassessthetherapeuticpotentialofa drug-candidatebeforeinitiatingphaseII/IIIstudies.Akeyproblem inAlzheimer’sandotherneurodegenerativediseasesisthat cognitivetests(Alzheimer’sDiseaseAssessment Scale-Cogni-tivesubscale(ADASCog)andMiniMentalStateExamination (MMSE)scores)currentlyusedtoassesstheclinicalbenefitof symptomaticdrugsmightsufferfromsubjectivity andlittle sensitivitytosubtlechangeswithextendedevaluationtime (oversixmonths).Furthermore,thereisnoequivalent task for animals in particular because a verbal component is predominantlyusedinthesetests.Thisfactemphasizesthe need todevelop new markerssensitiveto pharmacological interventionofutilitybothinpatientsandinhealthy volun-teers(HVT)toestablishthepharmacologicallyactiverange (for efficacy) before testing on larger groups of patients. Validation ofthesepredictive markers couldreduce delays anddecreasethesamplesizerequiredtodemonstratebenefit fromnewtherapeuticagents.

Inthiscontext,addingphysiologicalandfunctional ima-gingmarkers to thecurrentbattery of neurocognitive and neurophysiological measures in thedrugdiscovery process would seempertinent.Indeed,theassessmentofcognitive

function based on task categories may be associated with brainactivitywhichcanbemoredirectly linkedto biomar-kers (electrophysiology and functional imaging) currently appliedtotheclinicaldiagnosisofAD.

Nevertheless,toreliablydeterminethepredictivevalueof thesenewtools,anextensivestudyshouldbeundertakenin bothADandHVTpopulationstoassesstheirsensitivityto currentsymptomaticdrugs,specifictothecholinergic path-way ornot. The complementaryinformation providedby theintrinsic specificities ofthese techniques, thatis high spatialresolutionforfunctionalimaging versushigh tem-poral resolution forEEG, suggeststhe needfor combined biomarkersratherthanasingleone.Inaddition,these non-invasive markers reflect basic mechanisms of brain func-tioningratherthanspecies-dependentcognitivetasks.This promotes their use across species and may contribute to enhance the predictive value of pre-clinical studies and facilitatethetranslationofresearchevidencefromanimal to human. It is worth noting that great strides are being madetoimplementthesetechniquesinthepreclinicalfield to expand their use asmodern translational tool in drug discovery. These new tools may compensate for the lack of translatability of the neuropsychological assessment appliedtopatients.

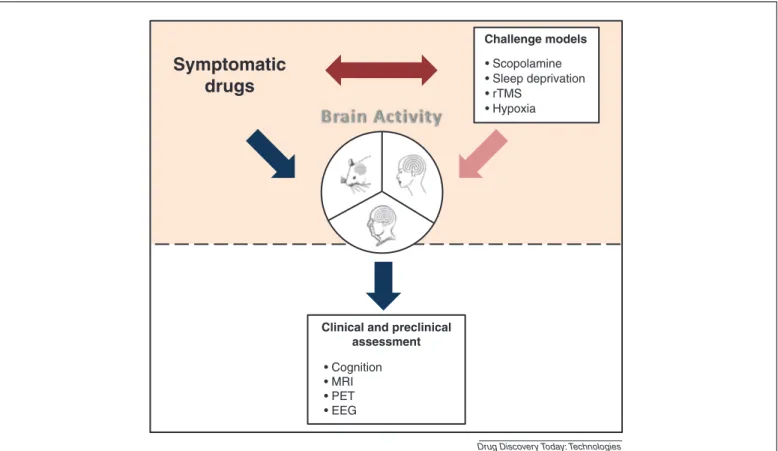

Incorporationofreliablebiomarkercombinationearlyin the process of development might improve the decision-making power at the early stages particularly in terms of clinicalefficacyofdrugcandidates(Fig.1).

Symptomatic drugs Cognitive assessment • Memory • Executive functions • Attention • Motivation New pharmacodynamic markers • MRI • PET • EEG Improvement of decision making

Drug Discovery Today: Technologies Figure1. Integrationofnewpharmacodynamicmarkersinthesymptomaticdrugsevaluationdesign.

Itisworthkeepinginmindthatthesebiomarkersmaynot be sensitive enough to detect changes in HVT, so their sensitivityinresponsetoachallengetestmaybeuseful.This, however,leadstoafurtherbarrierregardingtheemergenceof novelADdrugs.Infact,asoftoday,themostcommonlyused pharmacologicalchallengeiswithscopolamine,a non-selec-tivemuscarinicreceptorantagonist.Novelcognitive enhan-cingtherapieshavebeenassessedwithscopolamineboth pre-clinicallyandclinicallywithvaryingdegreesofsuccess.The weaknessofthis‘pharmacological’modelmightberelatedto: (a) its targetedaction ona singleneurotransmitter system whereasADisamultifocaldiseaseinwhichcognitive impair-mentresultsfromalterationofmultiplesystems, compromis-ingitsusetotestdrugsthatarenotexclusivelytargetingthe cholinergicsystem;(b)thepotentialpharmacological inter-action withtherapeuticdrugs couldcompromisethe inter-pretationofthedata.

To provide a ‘non pharmacological’ alternative to the commonlyusedscopolaminemodel,wesuggest investigat-ingthree potentialmodelswithdifferentapproaches:sleep deprivation; hypoxia; repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Sti-mulation(rTMS)toinducetransientcognitiveimpairmentin HVTsandrodents.Thebasicrequirementofthesechallenge models is to (i) be able to induce cognitive impairment and modify electrophysiological and imaging parameters and(ii)besensitivetocurrenttherapyforADwithdifferent

mechanisms ofaction toprovide abasisfor newpotential drugsassessment(Fig.2).

In this review, we seek to identify the most accurate markerstoassess drugeffect(ofcommercially availableAD symptomaticdrugs)amongneuropsycological, neurophysio-logicalandimagingtools(PET/MRI),basedonliteraturedata. Our investigationincludes clinicalandpre-clinical popula-tions:(i)healthyversusADsubjectsinhumansandrodents and (ii) translational physiological challenge models in humansandrodents.

Evaluationofsymptomaticdrugeffectonbiomarker battery

Currently,thefieldofADdrugdiscoveryresearchislacking in pharmacodynamic biomarkers capable of (i) rapidly detecting central activity (cognitive changes) in response to treatment, in healthy groups of animals and humans and(ii) predicting early therapeuticefficacy inAD clinical andpre-clinicalpopulations.

Thefollowingparagraphsummarizesthecurrentsituation. Insightsonbiomarkersintheclinicalfield

ADAS-Cog isthemost usedcognitivescaleto evaluate dis-turbancesofmemory,language,praxis,attentionandother cognitive abilities often referred to as the core symptoms of AD. Several systematic reviews reported significant

Symptomatic

drugs

Clinical and preclinical assessment • Cognition • MRI • PET • EEG Challenge models • Scopolamine • Sleep deprivation • rTMS • Hypoxia

Drug Discovery Today: Technologies

Figure2. Useofabiomarkerbatteryatearlystageofclinicaldevelopmenttoassesseffectofsymptomaticdrugsaloneorincombinationwithachallenge test.

improvementinADAS-Cog scoreinmildcognitive impair-ment(MCI)orADsubjectstreatedwithdonepezil,reflecting beneficial effects on cognitive status. In HVT, donepezil induces a slight improvement inthe retentionof training oncomplexaviation tasks [1],verbal memoryfor semanti-callyprocessedwords[2]andmightimprovelongtermvisual memory [3]. Nevertheless, some studies reported transient negativeeffectsonepisodicmemory[4,5]andno improve-mentintheCambridgeNeuropsychologicalTestAutomated Battery (CANTAB), a computer-based cognitive assessment systemconsistingofabatteryofneuropsychologicaltests.In arecentstudyconductedinhealthyolderindividuals, done-pezilhasbeenshowntoimpaircognitivefunctionassociated withalterationinadditionalneuralmarkersincludingEEG andfMRImarkers[6].Moreoveranticholinesterasetreatment alsoimprovedattentioninMCIandADpatients[7–13].

Evaluationoftheeffectofsymptomaticdrugsthroughthe measurementofelectroencephalogramvariablesconsidered asindices ofcognitiveprocessinghas beenextensively stu-diedinADpatients.Dataavailableintheliteratureonresting stateEEGindicatedthatlong-andshort-termtreatmentwith donepezil reduced significantly the deterioration of EEG spectralactivityandcorrelatedwithcognitiveimprovement rateontheADAS-cog.Thisimprovementismainly charac-terized byareduction oftheslow-wave activity(theta and deltapower)infrontalandtemporo-parietalareas[14–17].In asmallstudy,Sneddonandhiscolleaguesdemonstratedthe abilityofaqEEGvariancecombinedwithadelayed recogni-tionmemorytasktomeasureaccuratelytreatmenteffectson patients withAD [18]. In healthyelderlysubjects, a single doseofmemantinehasbeenshowntocompensatediurnal vigilance fluctuation measured by EEG recording [19]. AnotherEEG component,theP300isofspecial interestas itisrelatedtobrainfunctionssuchascognitionand atten-tion,whichareseverelyimpairedinpatientswithdementia [20].InADpatientsperformingauditoryandvisualoddball tasks, significant changes expressed by a reduction of the P300latencywereobserved already duringthefirstmonth of donepezil administration [21,22] and were significantly correlated with various neuropsychological score changes [22–24].

With regardsto theMR technique, various studies have undertaken anatomical analysis of hippocampal volume. They indicated a decrease in hippocampal volume loss/in therateof hippocampalatrophy followingtreatment with donepezilormemantinethatcloselyrelatesto neuropatho-logicandclinicaldata[25–27]. FunctionalMRI isuniquely suited for evaluation of cognitive-enhancing agents. In 2 cognitive paradigmsofvisualmemory,donepezil hasbeen reportedtoproduceactivationintheventrolateralprefrontal cortex(PFC)andinthefusiformgyrusinpatientswithMCIor

AD [28,29]. Another study demonstrated that donepezil

reversed the deficit of activation in fronto parietal region

duringaworkingmemorytaskinMCIpatients[30].Finally,a reducedactivationinthePFCandanteriorcingulatecortex was observed after memantine administration during an auditoryattentioncontroltask[31]. Using[18 F]fluorodeox-yglucose (FDG-PET) imaging, a study under resting condi-tions demonstrated that treatment with donepezil in AD patients may slow thedecline in functional brain activity intherightparietallobe,lefttemporallobeandrightandleft frontallobes[32].Inaddition,Teipeletal.showedthatthe metabolic changes inducedby donepezil, duringa passive audio-visualstimulation,werelimitedtotheright hippocam-pus and the left PFC and independent of the effects on cognitiveperformance[33].Finally,inpatientstreatedwith memantine for 52 weeks, glucose metabolism in all brain areaswaspreserved[27].

Theseinsightssupportthepotentialsuitabilityof electro-physiological and imaging measurements to monitor the effectsof symptomaticAD drugs ina contextofdisturbed (inADpatients)ornon-disturbed(inHVT)subjects. Insightsonbiomarkersinthepre-clinicalfield

Tobridgethegapbetweenpre-clinicalandclinicalresearch studies,greatprogresshasbeenmadeinthedevelopmentofa widerangeofpathologicalmodelsofADandimprovementof functional analysis techniques very similar to those per-formedintheclinicalsetting(microPET,wirelessmicrochip technologiesforEEG).

The disease models attempt to reproduce most of the neuropathology including neurophysiological and beha-vioralhallmarksofADpathology[34,35]. Sincethe promi-nentfeatureofADisthelossofneuronsandsynapsesinthe hippocampalformation andrelated areas,neurobehavioral phenotyping ofmouse models ofADhave focusedon the evaluationofhippocampal-relatedcognitiveareasincluding spatial-, contextual-, working-and recognition memory. These cognitive functions have been extensively explored through a classical battery ofexperimental tasks that con-tributedtothecharacterizationofcognitiveprofileassociated witheachtransgenicline[35].Despitetheirlimitations,the comprehensivestudyofthesetransgenicmousemodels pro-videdagoodopportunitytoevaluatetheirtranslationaland predictive value of drug efficacy. The next section sum-marizesthedataonthesensitivityofcognitivetestsandof new technological biomarkers that aim to measure the responsetoADdrugsingeneticallymodifiedandwildtype mice.

Inasubstantialwork,VanDamandcolleaguesattempted tovalidatetheAPP23model[36]bystudyingthereversibility ofspatiallearningandmemoryimpairmentinresponseto therapeutically relevant dosesof three acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors and memantine. They reported that the lowest dose ofDonepezil, rivastigmine and to a lesser extentgalantamine,elicitedbeneficialeffectsonlearningand

memory performancemeasured in theMorris Water Maze (MWM) task [37]. As for memantine, modest effects have beennotedwithonlypartialimprovementofspatiallearning abilities[37].However, inasubsequentreport,theauthors demonstrated thatlonger administrationof memantine(8 weeks)improvedtheeffect[38].IntheTg2576mousemodel of[39]AD,Dongandcolleaguesalsodemonstratedbeneficial effectsofdonepezilonspatiallearning/memorywithregards toimprovementofacquisitioninthewater T-mazeandin contextualmemoryinaconditionedfeartest[40]. Further-more,administrationofmemantinethroughdrinkingwater for3weekstoAPP/PS1transgenicmice[41]improved acqui-sitionbutnoretentionabilitiesinthewatermazetask[42]. Romberg and colleagues demonstrated that Donepezil res-cuestheattentiondeficitbyimprovingresponseaccuracyon the5-CSRTTadversely affectedinthe3xTgADmice model [43,44].

Withrespecttoinvestigationsofelectrophysiologicaland imagingmarkersinexperimentalADmodels,thereislimited data.Aninterestingpaperreviewedthefindingsobtainedto date fromstudies using PETimaging andEEG to monitor pathologicalchangesinrodentADmodels.Theycompared FDG-PETphenotypesin3cohortsoftransgenicstrainsand indicatedthatmetabolicactivitywasreliablycompromised inPSAPPandPLB1tripletransgenicmice [45,46]butnotin APP/PS1mice[41]whichcarryadifferentmutationinthePS1 transgene [47]. In addition, with FDG-based autoradiogra-phy,metabolicchangeshavealsobeenreportedinthe3xTg mouse[48].HowevertheAD-relevantbrainregionspecificity isdiscussed.Furthermore,acomprehensiveanalysisofsleep patterns,vigilancestagingandqEEGconductedin APP/PS1-overexpressingmicehighlightedadecreasedinlowandan increasedinhighfrequency spectral EEGpower[49]. Simi-larly,AD-likeshiftsinspectralpowerrecordedintheparietal cortexarea,havebeenreportedinthetripletransgenicmice (PLB1triple),inagreementwithFDGhypometabolismmaps [50]. Moreover the authors suggested that these changes might precede the cognitive decline onset [44]. Although themethodtoevokeaP300inrodentisnowwellestablished, dataaremissinginthefieldoftransgenicanimalsofAD.

Thus,manyofthesetechnologicaltoolsaresorecentthat theirsensitivitytotherapeuticinterventionhasnotyetbeen fullyinvestigated.OnlyScholtzovaandcolleaguesfollowed upthetherapeuticresponsetomemantineinAPP/PS1 trans-genicmiceregardingamyloiddepositionbymicromagnetoc MRI. Despitemodest changesbetweencontroland treated groups this tool was able to detect reduction in amyloid burden,whichcorrelateswithcognitiveimprovement[51].

Fortunately,thegoodcorrelationbetweenthepreclinical preliminary results on transgenic strains and human out-comes encourages theanalysis ofthemodulation of these markersinatherapeuticcontext.Nevertheless,itis interest-ingtounderlinethatnochangeinacquisitionorretention

performancewas observed in wild type (WT) mice among treatedgroups[37],contrastingwithsomeresultsobtainedin HVT.However, Spowart-Manningand co-workersreported that the T-maze continuous alternation task assessing the spatialexploratoryperformancesdevelopedbyGerlai[52,53] wassensitiveenoughtorespondtodonepeziladministration by improving the spontaneous alternation rate in control mice [54]. Overall, studies on healthy animals cannot be discussed since the differences of performance between strainsaretooheterogeneousandthemajorityoftasks are sensitivetogeneticdifferences.Thesensitivityofaparticular experimentdependsatleastpartially,uponthevalueofthe controlgroup.

Thisliteratureoverviewhighlightstheheterogeneityofthe cognitive assessment performed in the preclinical studies withvariousdifferentstimuliandsomemethodologicalissue (confoundingfactors).Thesedatacannotyetconcludewhich biomarkerarrayismostpertinent.

Evaluationoftheeffectofacognitivechallengeonthe biomarkerbattery-combined effectwith

symptomaticdrugs

Due to the inherent difficulty of detecting significant improvementsincognitiveperformanceinnormalhealthy subjects,pre-clinicalandclinicalscientistshavedevelopeda number of experimental paradigms to artificially induce cognitive impairments akin to those observed in AD. The identificationandvalidationofHVTchallenge models sui-table for use in early clinical development might support ‘hintofefficacy’studiesthatcanbebacktranslatedto pre-clinicalstudies.ThecomplexityofADpreventsrecapitulating both the pathophysiology and symptoms in one animal model.Currently,eachanimalmodelonlypartiallyreflects theunderlyingpathology,forexample,theamyloid aggre-gates. Conversely, pharmacodynamic models are more straightforward than disease models and should exhibit one or more transient cognitive impairments (also typical ofAD)thataresensitivetothepharmacologicalactiverange of the compound in question. Validation of such models will rely on (a) the characterization of the cognitive and neurofunctionaldeficitsinduced,(b)theirsensitivityto cur-rentsymptomatictreatmentand(c)theirbidirectional trans-latability. The nature of these challenge models is very important.Weproposetostudythreedistinct non-pharma-cologicalmodelsthatdevelopatransientcognitive impair-mentinHVTorrodentsfollowingsleepdeprivation,hypoxia andrTMSchallenges.Thus,inthenextsection,wewillreview studiesthathaveexaminedtheeffectsofprovocation chal-lenges and how thesedynamically alter cognitive, electro-physiological and neuroimaging markers and how these markers respond to symptomatic treatment. To highlight the translational properties of each challenge model, clinicalandpreclinicalfindingswillbediscussedinparallel.

Beyondidentifyingthemostappropriatemodel,thesecond objective,inthiscontextofchallengemodels,istoselectthe most relevant biomarkers for the assessment of treatment efficacy.

Sleepdeprivationchallenge

Sleepdeprivation(SD)hasbeenlargelyinvestigatedin clin-icaltrialsduetoitsassociation withdeficitsinthememory process.ManybehavioraladverseeffectsofSDincludingthe degradationofawiderangeofcognitivefunctionshavebeen fullydescribed(forreview[55]).Onthebasisofstudiesthat have focussed on total sleep deprivation (TSD) protocols, there is extensive literature reporting the deterioration of executive functioning including decision making, flexible thoughts,semanticprocessingandinhibitionaswellas work-ingmemory[56–59].Episodicmemorywasalsoimpairedin verbalandvisualdomainsandsimpleandcomplexattention processeshavebeenshowntobedisrupted[60–62]. Interest-ingly,thedurationofTSDisnotcorrelatedwiththe magni-tudeofcognitiveimpairmentsinthatunderprolongedTSD performanceremains stable[63–65]. Inaddition, cognitive deficitsareinverselycorrelatedwithcerebralactivityas mea-suredbyfunctionalimaginginvestigations. InaPETstudy, Thomas andcolleagues notedadecreased glucose metabo-lisminfronto-parietalandthalamicareas[66].Otherauthors demonstratedahypometabolisminthefrontalregionsthat correlated with disturbances in working memory perfor-mances[67–69].Furthermore,metabolicdecreasesin poster-ior parietal cortices have been associated with deficits of verbalworkingmemory[70].Morerecently,themodulation ofblood-oxygen-level-dependent(BOLD)fMRIsignal inten-sityhasbeenassessedinsleep-deprivedsubjectsperforminga divided attention task and the vulnerability of pre-frontal cortex to sleep deprivation previously observed has been confirmed [71,72]. However some inconsistent findings may be noticed between clinical trials. These differences maybepartlyexplainedbytheinter-individual heterogene-ityin thesubjects’sensitivity toSD. StudiesofSDonEEG power spectra have revealed an increase in low-frequency EEGpower(deltaandthetafrequencies) afterTSD [73–75]. Similarly,significantreductionofalphapowerinrapid eye movement (REM) sleep has been detected after total and partial SD [73,76]. Topographical analysis combining EEG to PET has been suggested to access the spatio-temporal changesofEEGsignalinpharmacologicalstudies[75]. Simi-larly,thereisevidenceofanegativeimpactofsleep depriva-tion onthe auditoryevent related potential(ERP). SD has beenshowntoinduceadelayofP300latencyandareduction ofitsamplitude[77–79].OtherERPcomponentsseem sensi-tivetoSDtoalesserextent[77,79].

On the basis of this core feature of sleep deprivation someauthorshaveinvestigatedwhethersuchread-outsare reversedinresponsetotreatmentwithsymptomaticdrugs.In

twoconsecutivestudies,Chuahandcolleagueshaveexplored the effects of donepezil on cognitive and neuroimaging deficits that developed in a cohort of total sleep-deprived subjects.Thefirststudyconductedon28HVTshowedthat donepezil administered for 17 days enhanced both visual short-term memory and visual attention in sleep-deprived HVT.Thisbehavioralbenefit,observedinindividuals vulner-abletotheeffectsofsleepdeprivation,primarilycorrelates withanincreaseinneuralactivationintheparieto-occipital regionsthatmediateattentionandvisualsensoryprocessing [80]. The second study performed on the same subjects showed that donepezil could improve performance in an episodicmemorytask.Theyalsodemonstratedasignificant correlation between left inferior prefrontal activation at encoding, and performances in recognition memory that mayrelatespecificallytoepisodicmemory[81].This relation-ship between fMRI pattern and behavioral drug effects emphasize thevalue ofcombining thesetwomeasures for futuredrugcandidateassessment.Furthermore,inthe con-textof sleep deprivation-induced episodic memorydeficit, donepezilenhanced activationofcerebral regionsinvolved in attention and memory encoding processing during a semantic judgementtask[81]. A recentwork failedtofind any donepezil-induced improvement of memory or non-memorycognitivetasksimpairedbysleepdeprivation[82]. Manyanalogies have beenproven inpre-clinical studies challengingTSD(REMsleepdeprivationhasnotbeentaken into account).Interms ofcognition,long-term and short-term SD has been shown to alter hippocampal-dependent spatial learning and memory in the MWM task [83,84]. RepetitionofbriefepochsofSD overalongperiodoftime [85] or protocols of sleep fragmentation [86–88] lead to similar effects. Nevertheless, in light of these studies, the consolidationprocessofspatialinformationseemstobemost vulnerabletosleepdeprivation.Furthermore,inan alterna-tionparadigmmeasuringworkingmemoryability,whereSD was given after training, disturbed the alternation rate [89,90].Thefearconditioningparadigmhasalsobeenused toassessdeclarative-likememoryinsleep-deprivedanimals. FindingsrevealedthatSD negativelyaffectstheacquisition and consolidation phase of contextual fear conditioning related to the hippocampus [91–94] whereas performance ofcuedfearconditioningrelatedtotheamygdalaisspared [91]. UsingtheNovelObject Recognition(NOR)task, con-sideredtomeasureepisodicmemoryasthatinhuman[95], researchersindicatedthatSDadministeredafterthe acquisi-tion phase severely impairs object recognition during the retentiontest[96,97].Finally,attentionprocesseshavealso beenexploredintheSDcontextinrodents.SDwasshownto impairanimals’speedandaccuracyinthefivechoicereaction timetaskhowevernodeficitintheexecutivecontrolofthe taskwasobserved[98].Thesefindingsareinagreementwith another study using a sleep fragmentation protocol [99].

Intermsofelectrophysiology,studiesinratsandmicehave shownanoverallincreaseinslowwaveactivityafterSD[100– 102]. ERP parameters have not been explored in the SD preclinicalchallenge.EffectofSDonmodulationofneural activitymeasuredbyfunctionalimaginginrodentshasyetto be reported. Similarly, the reversal effect of symptomatic drugsonmodificationofmarkersinducedbysleep depriva-tionhasnotbeenprobed.

rTMSchallenge

Transcranialmagneticstimulationisapainlessmethodbased ontheinductionofasmallelectricalcurrentinthebrainbya magnetic field applied to a small area of the skull. This technique has been described as a non-invasive transient waytointerferewithcognitivefunctionsbythestimulation ofspecificareasofinterest[103,104].Despitethe incontest-ableinterestofthismethodasa‘virtuallesiontechnique’to studycognitivefunctions,itsapplicationremainslimiteddue to itslimited depthof penetration[105]. At present, deep areasofthebrainlocatedmanycentimetersbelowthescalp suchashippocampus,amygdalaormammillarybodies can-notbedirectlyreached.However,combinationofTMSwith fMRIseemstodemonstratethattheactivityoftheseareascan beactually modulated by TMS, presumablydue to transy-napticeffects.Thus,researchismainlyfocusedon stimula-tionoffrontoparietalnetworksinvolvedinworkingmemory as well as the encoding and retrieval of novel items. In particular several studies targeted the role of the PFC in episodicmemory.Theseworks,usingdifferentexperimental tasks requiring wording, demonstrated that recall perfor-mances were impaired followingrTMS over theleft dorso-lateralPFCduringtheencodingprocess[106–111].Asimilar effectwasobserved,forsomeoftheseworks,followingrTMS over the right dorsolateralPFC during retrieval suggesting thatthereisaleftencoding,rightrecognitionPFCasymetry for memory processes [108–111]. These findings were in agreement with a recent study demonstrating that paired-pulse TMS applied over the left or right dorsolateral PFC interferedwithepisodicencodingandretrieval,irrespective ofthetypeofmaterialused(verbalversusnon-verbal)[112]. In addition, TMS over the left antero-ventral inferior PFC regionhasbeenshowntodisruptepisodicencodingof non-verbal material [113]. Regarding working memory, many investigationshighlighted thenegative impact ofrTMS in various brain areas on this cognitive function (for review [114]).Mottaghyandcolleaguesreporteddisruptionin work-ingmemoryforfaces(facerecognitiondelayedresponsetask) whenrTMSwasappliedtoventralPFCanddorsolateralPFC whilespatialworkingmemorywasaffectedfollowingrTMS overthedorsolateralPFCanddorsomedialPFC[115]. Impair-ment ofvisual workingmemoryafter leftdorsolateral PFC stimulation has also been described [116–118]. Moreover WagnerandcolleaguesprovidedevidencefordelayedrTMS

effectsondivided attentiontaskperformances sincevisual reactiontimeisslowedover30minafterrTMSsessionatthe dorsolateral PFC [119]. Other studies report that applying rTMStothesuperiorparietallobuleproducesadisruptionof cognitive behavior [120–122]. Kessel and colleagues also indicatedthatthereactiontimesmeasuredinaspatial work-ingmemorytaskwereslowerduringright-parietalrTMSthan duringleft-parietalrTMS[123].Howeverdiscrepantfindings wereobservedfortheeffectofrTMSonattentionalprocesses [124]. Finally, cerebellar TMS isable to influence memory abilitiesincluding workingmemory[125,126]. Multimodal approaches have also been conducted by combining TMS withneuroimagingorelectrophysiologicalmethodstoassess spatial distribution of TMS-evoked activity and brain con-nectivity[127].Theseinvestigationssuggestedanactivation of brain structures distant from the TMS-stimulated area [128–135]. Other studies assessed the brain–behavior rela-tionship,thatisthemodulationofbrainfunctionduringa cognitive task, by combination of TMS with PET during cognitive performances. Mottaghy and co-workers empha-sized the concomitant alteration of working memory task performance with a change in the activation pattern as revealedby PET,inthecondition withrTMSoftheleftor rightdorsolateralPFC[136].Thesameteamdemonstrateda positivecorrelationbetweentheregionalcerebralbloodflow changesinthesuperiorfrontalgyrusfunctionallyconnected to the stimulation site and performances in the working memorytask[137]reviewedin[114].

The emergence of a new method to avoid the artefact problem caused by the magnetic pulse proposed by Thut and colleagues have provided a means for studying the impactofTMSonthefunctionalelectrophysiologicalsignals associated with(cognitive) taskperformance, such as ERPs [138].An equivalentprocedurehas also beendevelopedin animals [139]. Effect ofrTMSon auditoryoddball taskhas been investigated after stimulation over dorsolateral PFC. Using an auditory oddball task,the authors demonstrated awidespreadsignificantlyreducedalphedesynchronisation post-TMSwhiletheP300component(amplitudes or laten-cies)wasnotaffected[140].Incontrast,stimulationofthe supramarginalgyrusbyTMSappliedat200msafterthe odd-ballsoundspresentationdelayedthepeakresponseofP300 [141].Moreover,EEGpowerspectrum hasalso been exam-ined immediately followingrTMS. Studies reported a tem-poralincreaseinfrequencyandamplitudeofEEGwithinthe first2minafterhighfrequencyrTMSoverleftfrontalcortex [142]. Schutter and colleagues also indicated that medial cerebellar rTMS affected thehigh frequency band(gamma band)ofEEGspectrum[143].

The effectof acetylcholinesteraseinhibitorsor meman-tine on neurophysiological parameters, fMRI or cerebral glucosemetabolismhasnotbeenyetstudiedinthecontext ofrTMS.

Comparedtothelargenumberofstudiesinhumans,there afewstudiesdescribingtheeffectsofrTMSonmemoryand learninginanimalmodelshavebeenlittlestudied.Thiscould berelatedtothedifficultyofpreciselystimulatingaspecific brainareawiththistechniqueinanimals.Moreover,many stimulation parameters such as frequency, intensity, dura-tion and number of pulse can modulate the behavioral response. An interesting study hasinvestigated theimpact ofthemodulationofstimulationfrequency(chronicversus acute) onmemory performanceinrats[144]. Thefindings indicated that chronic low frequency stimulation could impair the retrieval of both short- and long-term spatial referencememorysparingtheacquisitionprocess;whileafter acute rTMS only the long-term reference memory was impaired. In another study Ahmed and Wieraszko high-lighted the importance of the magnetic field properties applied. They demonstrated a temporary deterioration of performancesintheNORtest performedimmediatelyafter stimulationatlowerfrequencies (1and8Hz)while perfor-mancewasimproved after stimulationathigherfrequency (15Hz).However,whenthetestisperformed1hor3days afterhighfrequencyrTMS,performancesinNORtestarealso impaired [145]. Other researchers concluded that 50 brief pulsetranscranialmagneticstimulationsmaycausea disrup-tion ofretrograde memoryfor conditionedtaste aversions [146].Regardingcorticalelectricalactivity,ratssubjectedto lowfrequencyrTMSdisplayareductioninamplitudeofthe powerspectrainthehighfrequencybands(betaandgamma) [147]consistentwithclinicalfindings[142,143].

Hypoxiachallenge

Theinterest inhypoxia asa potentialinducerofcognitive disorder results from studies conducted in the context of aviation and mountain ascent. Nevertheless the role of hypoxia on cognitive domains remains relatively unex-plored.Overall, studiesintheliterature indicatedthat cog-nitive impairmentcaused by hypoxia ismodulated by the severity of hypoxic level and the population considered (experiencedversusnonexperiencedparticipants).To accu-ratelycompareclinicalandpreclinicaldata,wefocusedour interest on behavioral and neurophysiological effects of hypoxia on non-experiencedsubjects (naı¨vefrom hypoxic environment).Cognitivefunctionsincludingexecutive func-tioning,workingmemoryandattentionhavebeenreported tobeaffectedbyhypoxia.Unfortunately,resultsseem some-whatcontradictoryduetoalackofmethodological consis-tencyamongstudies.Neverthelessacoreoffindingsseemsto demonstratealterationofperformanceinserialrecognition of words, the binary choice task and auditory and visual reactiontime[148].Noble andco-workersalso reportedan overall slowing on task measuring executive functioning [149] that was not confirmed by others [148,150]. Studies have provided evidence of an impairment in executive

processesindicatedbyadeclineintheGrammaticalLogical Reasoningtask[151,152]associatedtoaninabilitytolearna noveltask[152].Workingmemoryisalsoaffectedfollowing short-termexposuretohypoxiashownbyalterationof per-formances in a go/no-go discrimination task [153]. These disturbanceswerenotobservedintherapidvisualcategorical task[154].Inaddition, manystudiesshoweddisruption of some aspect ofattentional processes through various tests

[56,155–159]. Episodic memory has not been studied.

Although neuropsychological results are highly controver-sial,moreconsistentresultscomefromelectrophysiological investigations.MoststudieshaveshownEEGchanges char-acterizedbyincreasesindeltaandthetapowerandadecrease inalphaactivityunderhypoxia[158,160–162].Moreoveran identicaltrend,withregardstoERPP300assessment,emerges fromtheliterature.Indeed,long-andshort-termexposuresto hypoxia have induced an increase of P300 latency with minimaleffects onP300amplitude [163–165]. Other para-meterssuchasN100,P200andN200seemlesssensitiveto hypoxia[164].

Using neuroimaging techniques various clinical studies have investigated the cerebrovascular response to hypoxia analyzing regional cerebral blood flow distribution [166– 168].Datademonstrateddifferentialphysiologicalsensitivity of various brain regions. Functional neuroimaging data demonstratedspecificsensitivityoffrontallobes[169] sup-ported by themetabolic reduction observed in thisregion [170]. Thus, hypoxia seems to affect the cerebral network involvedintheattentionprocess, whichisconsistentwith neuropsychological deterioration. As for the challenge of rTMS, the effect of symptomatic treatment has not been testedunderhypoxiachallenge.

Studiesofhypoxiainrodentshaveexperiencedidentical discrepancies regarding cognitive deficits since intensity, frequency andduration ofhypoxiaexposure modulatethe magnitudeofcognitivealterationinrodents[171,172]. Find-ings demonstrated detrimentaleffects of hypoxia on both acquisition and consolidation processes in different para-digmsofcognitive tests.Chronicexposure tohypoxia can alterworkingandreferencespatialmemoryassessedinMWM task[173–180].Thesespatialmemorydysfunctionshavealso beennotedafteracuteexposureofhypoxiabeyonda thresh-oldlevel[172,181].Usingplace-discriminationtaskinaradial arm maze,Titus confirmedthese spatialimpairments that occurfollowingseveraldaysofhypoxia [182]. Inaddition, Zhang reported dysfunction in acquisition and retention processes in a shuttle box paradigm which models non-declarative memory [183]. In the passive avoidance task, Udayabanuandco-workersrevealedthathypoxiacouldonly disruptretrogradememorysuggestinganeffectofhypoxiaon consolidation[184].Finallybriefexposuretohypoxialedto milder and more transient cognitive alteration in spatial working memory assessed in the Y maze task and in the

NOR task[185–187]. Inaddition acute exposure interfered withconsolidationofmemoryinthestep-throughavoidance task[188].Thesensitivityofothermarkerstohypoxiahasnot beenstudiedinrodents.Theeffectofsymptomaticdrugson cognitiveimpairmentinducedbyhypoxiahasbeenexplored. For example, Physostigmine and Galantamine has been tested to improve spatial learning and working memory inducedbychronichypoxia[180].Inaddition, administra-tionofphysostigminepriortohypoxicexposurewasshown topreserverecognitionmemorysensitivetohypoxia[185]. Strengthsandweaknessesofcurrentstrategiesandidentificationof translationalrequirements

Currently,themajorityofsymptomatictreatmentsfaildueto a lack of efficacy in patients detected during phase II/III clinical studies. This suggests that current preclinical and clinical methodsto test drug efficacy are not effective.To improve thecurrentprocess ofdrugdevelopment,we pro-posed to introduce new pharmacodynamic biomarkers at eachstageofpreclinicalandclinicaldevelopment,in addi-tiontocurrentclinicalandneuropsychologicalassessments. Thesemarkersarebasedonneurophysiologicaland neuroi-magingmeasurementsalreadycommonlyusedintheclinical field (fordiagnosis andbetterunderstandingofthe patho-physiology).Theyareadirectreflectionofcerebral activity patternsandmayovercomethefrequenlycriticized neurop-sychologicalevaluation,which lacksobjectivity.Moreover, unlikecognitiveenhancementthatmustbeevaluatedovera periodofsixmonths,drugeffectsonphysiological biomar-kers mightbe detectableover a shorter time.Our detailed reviewoftheliterature indicatesthatthesealternative bio-markersdisplayagoodsensitivitytosymptomatictreatment inADorMCIpatientssinceinmostcasesimprovementinthe pharmacodynamicmarkerscorrelateswithcognitivegain.In HVT,studiesarescarceanddonotallowanassessmentofthe contribution ofthese biomarkersas predictive tools. How-ever, furtherstudies toassess iftheir use is pertinentmay clarifythisissue.

Fromapreclinicalpointofview,thedevelopmentofthese biomarkersreflectingbrainactivityinaphysiologicalresting statemightreducethegapbetweenpreclinicalandclinical phases. Indeed, some evidence suggests that the limited translatability of animal cognitive testsmight explain dis-appointing results in the development of successful treat-mentsforAD.TheuseofEEG,PETandMRIinthepreclinical assessment protocol of new pharmacological compounds should facilitate the extrapolation of preclinical outcomes totheclinicalfield.Resultsobtainedfromstudieson geneti-callyengineeredanimalmodelsindicateagreatsensitivityof these markers to AD pathogenesis supporting their use as translational tools. However their sensitivity to clinically approved symptomatic treatments has not yet been explored.Nevertheless,wecannotoverlooktheimportance

ofcognitiveendpointsinthepredictivevalidityofpreclinical models. As evidenced by the review, cognitive tests used today are disparate and poorly comparable to those per-formed inhumans.Theselimitationsarereinforcedby the factthattheneuropsychologicalbatteryusedasareference standard to assess clinical drug efficacy, the ADAS-Cog, is almostimpossibletomodelinrodentsasthisspecificscale mainly explores unavailable functions in rodents, that is verbalmemory,languageandpraxis. Overthepastdecade, anewtechnologicalinstrumentspecificallydesignedto facil-itatecross-specieshasemerged.Thetouchscreentechnology reliesonasetofstraightforwardcognitivetasksprocedurally similartoclinicalneuropsychologicaltestsbelongingtothe CANTABbattery(computer-basedcognitivetestprocedures becoming moreprevalent in the clinical cognitive testing domain).Theyexplorethroughcomputer-automated cogni-tivetestsarangeofcognitivedomains(memory,attention, executivefunctions)thoughttobeaffected inAD.In addi-tion, this standardizedcognitive exploration tool uses the sametypesofvisualstimuliusedintheCANTABtasks.The predictivevalidityremainstobedemonstratedbyextensive studies. Validation of translational cognitive tasks may potentiallyexpandtheroleofEEGandPETinthepreclinical modelswherebythesemarkerscanbemeasuredunder spe-cific tasks [189,190]. MRI performed in rodents under anesthesia,cannotbenefitfromsuchstudies.

Inlightofthese preliminaryresults and observations,it appears that these alternative markers – combined with appropriate cognitive assessment- would contribute to improvethepredictiveandtranslationalvalueofdrug devel-opment stagespreceding PhaseII/IIIstudies. However, the drugdiscoveryprocessmaystillsufferfromalackof predict-abilityinearlystageexperimentalmedicinestudiesduetothe difficulties in identifying benefits of cognition enhancer compoundsinHVTwithoutcognitiveimpairment.Itmight be easier to reverse existing deficits than improve normal functioning.Inthisview,ourstrategytoimprovepredictive capacityis to include,in preclinicaland clinical(phase 1) trials translational pharmacodynamic models that exhibit cognitive impairment reminiscent of that observed in patients withAD.Thechoice ofnon-pharmacological pro-vocationchallenge–sleepdeprivation,rTMSandhypoxia– withabroaderactionintheCNSmightprovideanalternative modeltothescopolamineone,limitedbyits pharmacologi-calnature.

Overall,thisreviewconfirmsthefeasibilityofinducinga transient cognitive disorderin human and rodentmodels. The cognitive deficits relate to multiple functions such as executivefunctions,workingmemoryandattention. Inves-tigationsonneurophysiologicalandimagingbiomarkersare lessextensivebutseemtoshowmodulationsofthese para-metersinresponsetothechallenges.However, methodolo-gicalissuesandlackofharmonizationofclinicalassessment

toolsmakeitdifficulttocomparethesechallenges.Itwould beinterestingtoevaluatetheintrinsiclimitsofeachmodelby performing parallel studies with standardized assessment protocolsbasedonabiomarkerbatteryincludingcognitive, neurophysiologicalandimagingendpoints.Thereversibility ofchangesin response tosymptomatic drug exposurewill definetheirpredictabilityandconsequentlytheirownability tosupport‘hintofefficacystudies’inearlyclinicalstagesas wellasinpreclinicalstudies.

Theidentificationofthemostsensitive combinationof pharmacodynamic markers (as clinical efficacy indices) andpharmacodynamicmodels(forearlypredictionof effi-cacy)will increasethe effectivenessof thedrug discovery processinADthroughamultidimensionalmatrixapproach (Fig.3).

Conclusion

Afairlyabundantliteratureisnowavailableon:(i)theeffect ofADsymptomaticdrugsondifferentbiomarkersassessing brainactivity;(ii)theeffectofchallengetestsoncognitive function andthese similarbiomarkers ofbrain activity.In contrast,thedataonthecombinationofsymptomaticdrug andchallengetestremainpoorandwithcontroversialresults. Wefeelthatthiscombinationcoupledwithbiomarker assess-ment could bea new and stringentparadigm to test new symptomaticdrugsinthecontextofAD,inparticularatthe early stage of disease(Fig. 3).A systematicevaluation and validationofsuchanapproachremainsnecessaryandit is oneofthegoalsoftheIMI Pharmacog consortium,which aimstofurtherexplorethepreclinicalansclinicalstudiesin thecontextofgoldstandardsymptomatictreatmentsforAD.

Conflictofinterest

Theauthorshavenoconflictofinteresttodeclare. Acknowledgements

Thisresearchwasdevelopedundertheethicalrequirements compliedwiththeEuropeanCommunityCouncilDirective (2010/63/UE).Theresearchleadingtotheseresultswas con-ductedaspartofthePharmaCogconsortiumfundedbythe EuropeanCommunity’sSeventhFrameworkProgrammefor theInnovativeMedicine Initiative underGrantAgreement no. 115009.For further information please refer to http:// www.pharmacog.org/

References

1 Yesavage,J.A.etal.(2002)Donepezilandflightsimulatorperformance: effectsonretentionofcomplexskills.Neurology59,123–125

2 FitzGerald,D.B.etal.(2008)Effectsofdonepezilonverbalmemory aftersemanticprocessinginhealthyolderadults.Cogn.Behav.Neurol.21, 57–64

3 Gron,G.etal.(2005)Cholinergicenhancementofepisodicmemoryin healthyyoungadults.Psychopharmacology(Berl.)182,170–179 4 Beglinger,L.J.etal.(2004)Neuropsychologicaltestperformancein

healthyvolunteersbeforeandafterdonepeziladministration.J. Psychopharmacol.18,102–108

5 Beglinger,L.J.etal.(2005)Neuropsychologicaltestperformancein healthyelderlyvolunteersbeforeandafterdonepeziladministration:a randomized,controlledstudy.J.Clin.Psychopharmacol.25,159–165 6 Balsters,J.H.etal.(2011)Donepezilimpairsmemoryinhealthyolder

subjects:behavioural,EEGandsimultaneousEEG/fMRIbiomarkers.PLoS ONE6,e24126

7 Bentley,P.etal.(2008)Cholinesteraseinhibitionmodulatesvisualand attentionalbrainresponsesinAlzheimer’sdiseaseandhealth.Brain131 (Pt2),409–424

8 Blin,J.etal.(1998)Physostigmineresultsinanincreaseddecrementin brainglucoseconsumptioninAlzheimer’sdisease.Psychopharmacology (Berl.)136,256–263

Cognition EEG

MRI PET

WT mice Animal challenge modelAD model HVT Human challengeAD patients mo

del

POSITIVE EFFECT

NEGATIVE EFFECT Phase I/II

GO / NO GO

Phase III

Drug Discovery Today: Technologies Figure3. SimulationofanADdrugdevelopmentusingamatrixbattery.

9 Foldi,N.S.etal.(2005)Detectingeffectsofdonepezilonvisualselective attentionusingsignaldetectionparametersinAlzheimer’sdisease.Int.J. Geriatr.Psychiatry20,485–488

10 Lawrence,A.D.andSahakian,B.J.(1995)Alzheimerdisease,attention, andthecholinergicsystem.AlzheimerDis.Assoc.Disord.9(Suppl2), 43–49

11 Rockwood,K.(2004)Sizeofthetreatmenteffectoncognitionof cholinesteraseinhibitioninAlzheimer’sdisease.J.Neurol.Neurosurg. Psychiatry75,677–685

12 Sahakian,B.J.andCoull,J.T.(1993)Tetrahydroaminoacridine(THA)in Alzheimer’sdisease:anassessmentofattentionalandmnemonic functionusingCANTAB.ActaNeurol.Scand.Suppl.149,29–35 13 Sahakian,B.J.etal.(1993)Furtheranalysisofthecognitiveeffectsof

tetrahydroaminoacridine(THA)inAlzheimer’sdisease:assessmentof attentionalandmnemonicfunctionusingCANTAB.Psychopharmacology (Berl.)110,395–401

14 Balkan,S.etal.(2003)EffectofdonepezilonEEGspectralanalysisin Alzheimer’sdisease.ActaNeurol.Belg.103,164–169

15 Brassen,S.andAdler,G.(2003)Short-termeffectsofacetylcholinesterase inhibitortreatmentonEEGandmemoryperformanceinAlzheimer patients:anopen,controlledtrial.Pharmacopsychiatry36,304–308 16 Reeves,R.R.etal.(2002)TheeffectsofdonepezilonquantitativeEEGin

patientswithAlzheimer’sdisease.Clin.Electroencephalogr.33,93–96 17 Rodriguez,G.etal.(2002)QuantitativeEEGchangesinAlzheimer

patientsduringlong-termdonepeziltherapy.Neuropsychobiology46,49– 56

18 Sneddon,R.etal.(2006)QEEGmonitoringofAlzheimer’sdisease treatment:apreliminaryreportofthreecasestudies.Clin.EEGNeurosci. 37,54–59

19 Schulz,H.etal.(1996)TheuseofdiurnalvigilancechangesintheEEGto verifyvigilance-enhancingeffectsofmemantineinaclinical

pharmacologicalstudy.Neuropsychobiology33,32–40

20 Juckel,G.etal.(2008)Diagnosticusefulnessofcognitiveauditory event-relatedp300subcomponentsinpatientswithAlzheimersdisease?J.Clin. Neurophysiol.25,147–152

21 Reeves,R.R.etal.(1999)TheeffectsofdonepezilontheP300auditory andvisualcognitiveevokedpotentialsofpatientswithAlzheimer’s disease.Am.J.Geriatr.Psychiatry7,349–352

22 Thomas,A.etal.(2001)Donepezil,rivastigmine,andvitaminEin Alzheimerdisease:acombinedP300event-relatedpotentials/ neuropsychologicevaluationover6months.Clin.Neuropharmacol.24, 31–42

23 Katada,E.etal.(2003)Long-termeffectsofdonepezilonP300auditory event-relatedpotentialsinpatientswithAlzheimer’sdisease.J.Geriatr. PsychiatryNeurol.16,39–43

24 Werber,E.A.etal.(2003)TheclinicaluseofP300eventrelatedpotentials fortheevaluationofcholinesteraseinhibitorstreatmentindemented patients.J.NeuralTransm.110,659–669

25 Hashimoto,M.etal.(2005)Doesdonepeziltreatmentslowthe progressionofhippocampalatrophyinpatientswithAlzheimer’s disease?Am.J.Psychiatry162,676–682

26 Krishnan,K.R.etal.(2003)Randomized,placebo-controlledtrialofthe effectsofdonepezilonneuronalmarkersandhippocampalvolumesin Alzheimer’sdisease.Am.J.Psychiatry160,2003–2011

27 Schmidt,R.etal.(2008)Longitudinalmultimodalimaginginmildto moderateAlzheimerdisease:apilotstudywithmemantine.J.Neurol. Neurosurg.Psychiatry79,1312–1317

28 Kircher,T.T.etal.(2005)Corticalactivationduring cholinesterase-inhibitortreatmentinAlzheimerdisease:preliminaryfindingsfroma pharmaco-fMRIstudy.Am.J.Geriatr.Psychiatry13,1006–1013 29 Petrella,J.R.etal.(2009)Effectsofdonepeziloncorticalactivationin

mildcognitiveimpairment:apilotdouble-blindplacebo-controlledtrial usingfunctionalMRimaging.Am.J.Neuroradiol.30,411–416 30 Saykin,A.J.etal.(2004)Cholinergicenhancementoffrontallobeactivity

inmildcognitiveimpairment.Brain127(Pt7),1574–1583 31 vanWageningen,H.etal.(2009)Evidenceforglutamatergic

neurotransmissionincognitivecontrolinanauditoryattentiontask. Neurosci.Lett.454,171–175

32 Tune,L.etal.(2003)DonepezilHCl(E2020)maintainsfunctional brainactivityinpatientswithAlzheimerdisease:resultsofa24-week, double-blind,placebo-controlledstudy.Am.J.Geriatr.Psychiatry11, 169–177

33 Teipel,S.J.etal.(2006)Effectsofdonepeziloncorticalmetabolicresponse toactivationduring(18)FDG-PETinAlzheimer’sdisease:adouble-blind cross-overtrial.Psychopharmacology(Berl.)187,86–94

34 Higgins,G.A.andJacobsen,H.(2003)Transgenicmousemodelsof Alzheimer’sdisease:phenotypeandapplication.Behav.Pharmacol.14, 419–438

35 Bryan,K.J.etal.(2009)TransgenicMouseModelsofAlzheimer’sDisease: BehavioralTestingandConsiderations.

36 Sturchler-Pierrat,C.etal.(1997)Twoamyloidprecursorprotein transgenicmousemodelswithAlzheimerdisease-likepathology.Proc NatlAcadSciUSA94,13287–13292

37 VanDam,D.etal.(2005)Symptomaticeffectofdonepezil,rivastigmine, galantamineandmemantineoncognitivedeficitsintheAPP23model. Psychopharmacology(Berl.)180,177–190

38 VanDam,D.andDeDeyn,P.P.(2006)Cognitiveevaluationof disease-modifyingefficacyofgalantamineandmemantineintheAPP23model. Eur.Neuropsychopharmacol.16,59–69

39 Hsiao,K.etal.(1996)Correlativememorydeficits.Abetaelevation,and amyloidplaquesintransgenicmice.Science274,99–102

40 Dong,H.etal.(2005)Acetylcholinesteraseinhibitorsameliorate behavioraldeficitsintheTg2576mousemodelofAlzheimer’sdisease. Psychopharmacology(Berl.)181,145–152

41 Borchelt,D.R.etal.(1997)Acceleratedamyloiddepositioninthebrains oftransgenicmicecoexpressingmutantpresenilin1andamyloid precursorproteins.Neuron19,939–945

42 Minkeviciene,R.etal.(2004)Memantineimprovesspatiallearningina transgenicmousemodelofAlzheimer’sdisease.J.Pharmacol.Exp.Ther. 311,677–682

43 Oddo,S.etal.(2003)Triple-transgenicmodelofAlzheimer’sdiseasewith plaquesandtangles:intracellularAbetaandsynapticdysfunction.Neuron 39,409–421

44 Romberg,C.etal.(2011)Impairedattentioninthe3xTgADmousemodel ofAlzheimer’sdisease:rescuebydonepezil(Aricept).J.Neurosci.31, 3500–3507

45 Holcomb,L.etal.(1998)AcceleratedAlzheimer-typephenotypein transgenicmicecarryingbothmutantamyloidprecursorproteinand presenilin1transgenes.NatMed4,97–100

46 Platt,B.etal.(2011)Abnormalcognition,sleep,EEGandbrain metabolisminanovelknock-inAlzheimermouse,PLB1.PLoSOne6, e27068

47 Platt,B.etal.(2011)FDG-PETimaging,EEGandsleepphenotypesas translationalbiomarkersforresearchinAlzheimer’sdisease.Biochem.Soc. Trans.39,874–880

48 Nicholson,R.M.etal.(2010)Regionalcerebralglucoseuptakeinthe 3xTGmodelofAlzheimer’sdiseasehighlightscommonregional vulnerabilityacrossADmousemodels.BrainRes.1347,179–185 49 Jyoti,A.etal.(2010)EEG,activity,andsleeparchitectureinatransgenic

AbetaPPswe/PSEN1A246EAlzheimer’sdiseasemouse.J.AlzheimersDis. 22,873–887

50 Platt,B.etal.(2011)Abnormalcognition,sleep,EEGandbrain metabolisminanovelknock-inAlzheimermouse,PLB1.PLoSONE6, e27068

51 Scholtzova,H.etal.(2008)Memantineleadstobehavioralimprovement andamyloidreductioninAlzheimer’s-disease-modeltransgenicmice shownasbymicromagneticresonanceimaging.J.Neurosci.Res.86,2784– 2791

52 Gerlai,R.(1998)AnewcontinuousalternationtaskinT-mazedetects hippocampaldysfunctioninmice.Astraincomparisonandlesionstudy. Behav.BrainRes.95,91–101

53 Gerlai,R.etal.(1994)T-mazespontaneousalternationrateisdecreasedin S100betatransgenicmice.Behav.Neurosci.108,100–106

54 Spowart-Manning,L.andvanderStaay,F.J.(2004)TheT-maze continuousalternationtaskforassessingtheeffectsofputativecognition enhancersinthemouse.Behav.BrainRes.151,37–46

55 McCoy,J.G.andStrecker,R.E.(2011)Thecognitivecostofsleeplost. Neurobiol.Learn.Mem.96,564–582

56 Blogg,S.L.andGennser,M.(2006)Cerebralbloodflowvelocityand psychomotorperformanceduringacutehypoxia.Aviat.SpaceEnviron. Med.77,107–113

57 Chee,M.W.andChoo,W.C.(2004)Functionalimagingofworking memoryafter24hroftotalsleepdeprivation.J.Neurosci.24,4560–4567 58 Gottselig,J.M.etal.(2006)Randomnumbergenerationduringsleep

deprivation:effectsofcaffeineonresponsemaintenanceandstereotypy. J.SleepRes.15,31–40

59 Killgore,W.D.etal.(2009)Executivefunctionsandtheabilitytosustain vigilanceduringsleeploss.Aviat.SpaceEnviron.Med.80,81–87 60 Chee,M.W.etal.(2010)Sleepdeprivationanditseffectson

object-selectiveattention.Neuroimage49,1903–1910

61 Tucker,M.A.andFishbein,W.(2009)Theimpactofsleepdurationand subjectintelligenceondeclarativeandmotormemoryperformance:how muchisenough?J.SleepRes.18,304–312

62 Yoo,S.S.etal.(2007)Adeficitintheabilitytoformnewhumanmemories withoutsleep.Nat.Neurosci.10,385–392

63 Chee,M.W.etal.(2006)Functionalimagingofworkingmemory followingnormalsleepandafter24and35hofsleepdeprivation: correlationsoffronto-parietalactivationwithperformance.Neuroimage 31,419–428

64 Sagaspe,P.etal.(2006)EffectsofsleepdeprivationonColor-Word, Emotional,andSpecificStroopinterferenceandonself-reportedanxiety. BrainCogn.60,76–87

65 VanDongen,H.P.etal.(2003)Thecumulativecostofadditional wakefulness:dose–responseeffectsonneurobehavioralfunctionsand sleepphysiologyfromchronicsleeprestrictionandtotalsleep deprivation.Sleep26,117–126

66 Thomas,M.etal.(2000)Neuralbasisofalertnessandcognitive performanceimpairmentsduringsleepiness.I.Effectsof24hofsleep deprivationonwakinghumanregionalbrainactivity.J.SleepRes.9,335– 352

67 Chee,M.W.andChuah,Y.M.(2007)Functionalneuroimagingand behavioralcorrelatesofcapacitydeclineinvisualshort-termmemory aftersleepdeprivation.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A.104,9487–9492 68 Choo,W.C.etal.(2005)Dissociationofcorticalregionsmodulatedby

bothworkingmemoryloadandsleepdeprivationandbysleep deprivationalone.Neuroimage25,579–587

69 Mu,Q.etal.(2005)Decreasedbrainactivationduringaworkingmemory taskatrestedbaselineisassociatedwithvulnerabilitytosleep deprivation.Sleep28,433–446

70 Mu,Q.etal.(2005)Decreasedcorticalresponsetoverbalworking memoryfollowingsleepdeprivation.Sleep28,55–67

71 Drummond,S.P.etal.(2001)Increasedcerebralresponseduringadivided attentiontaskfollowingsleepdeprivation.J.SleepRes.10,85–92 72 Jackson,M.L.etal.(2011)TheeffectofsleepdeprivationonBOLD

activityelicitedbyadividedattentiontask.BrainImagingBehav.5,97– 108

73 Borbely,A.A.etal.(1981)Sleepdeprivation:effectonsleepstagesand EEGpowerdensityinman.Electroencephalogr.Clin.Neurophysiol.51,483– 495

74 Dijk,D.J.etal.(1993)Dynamicsofelectroencephalographicsleep spindlesandslowwaveactivityinmen:effectofsleepdeprivation.Brain Res.626,190–199

75 Landolt,H.P.etal.(2000)Zolpidemandsleepdeprivation:differenteffect onEEGpowerspectra.J.SleepRes.9,175–183

76 Brunner,D.P.etal.(1993)Repeatedpartialsleepdeprivation

progressivelychangesinEEGduringsleepandwakefulness.Sleep16,100– 113

77 Lee,H.J.etal.(2004)Auditoryevent-relatedpotentialsandpsychological changesduringsleepdeprivation.Neuropsychobiology50,1–5

78 Morris,A.M.etal.(1992)TheP300event-relatedpotential.Theeffectsof sleepdeprivation.J.Occup.Med.34,1143–1152

79 Ray,K.etal.(2012)ModafinilimproveseventrelatedpotentialsP300and contingentnegativevariationafter24hsleepdeprivation.LifeSci.91, 94–99

80 Chuah,L.Y.andChee,M.W.(2008)Cholinergicaugmentation modulatesvisualtaskperformanceinsleep-deprivedyoungadults. J.Neurosci.28,11369–11377

81 Chuah,L.Y.etal.(2009)Donepezilimprovesepisodicmemoryinyoung individualsvulnerabletotheeffectsofsleepdeprivation.Sleep32, 999–1010

82 Dodds,C.M.etal.(2011)Effectsofdonepeziloncognitiveperformance aftersleepdeprivation.Hum.Psychopharmacol.26,578–587

83 Chang,H.M.etal.(2009)Melatoninpreserveslongevityprotein(sirtuin 1)expressioninthehippocampusoftotalsleep-deprivedrats.J.Pineal Res.47,211–220

84 Guan,Z.etal.(2004)Sleepdeprivationimpairsspatialmemoryand decreasesextracellularsignal-regulatedkinasephosphorylationinthe hippocampus.BrainRes.1018,38–47

85 Xu,Z.Q.etal.(2010)Themechanismandcharacterizationoflearning andmemoryimpairmentinsleep-deprivedmice.CellBiochem.Biophys. 58,137–140

86 Hairston,I.S.etal.(2005)Sleeprestrictionsuppressesneurogenesis inducedbyhippocampus-dependentlearning.J.Neurophysiol.94, 4224–4233

87 Tartar,J.L.etal.(2006)Hippocampalsynapticplasticityandspatial learningareimpairedinaratmodelofsleepfragmentation.Eur.J. Neurosci.23,2739–2748

88 Ward,C.P.etal.(2009)Experimentalsleepfragmentationimpairsspatial referencebutnotworkingmemoryinFischer/BrownNorwayrats.J.Sleep Res.18,238–244

89 Hagewoud,R.etal.(2010)Sleepdeprivationimpairsspatialworking memoryandreduceshippocampalAMPAreceptorphosphorylation.J. SleepRes.19,280–288

90 Pierard,C.etal.(2007)Modafinilrestoresmemoryperformanceand neuralactivityimpairedbysleepdeprivationinmice.Pharmacol. Biochem.Behav.88,55–63

91 Anagnostaras,S.G.etal.(2001)Hippocampusandcontextualfear conditioning:recentcontroversiesandadvances.Hippocampus11, 8–17

92 Graves,L.A.etal.(2003)Sleepdeprivationselectivelyimpairs memoryconsolidationforcontextualfearconditioning.Learn.Mem.10, 168–176

93 Hagewoud,R.etal.(2010)Sleepdeprivationimpairscontextualfear conditioningandattenuatessubsequentbehavioural,endocrineand neuronalresponses.J.SleepRes.20,259–266

94 Ruskin,D.N.andLahoste,G.J.(2008)Aspectsoflearnedfearrelatedto thehippocampusaresleep-dependent.Behav.BrainRes.191,67–71 95 Dere,E.etal.(2004)Higherordermemoriesforobjectsencounteredin

differentspatio-temporalcontextsinmice:evidenceforepisodic memory.Rev.Neurosci.15,231–240

96 Halassa,M.M.etal.(2009)Astrocyticmodulationofsleephomeostasis andcognitiveconsequencesofsleeploss.Neuron61,213–219 97 Palchykova,S.etal.(2009)Sleepdeprivationinthedarkperioddoesnot

impairmemoryinOF1mice.Chronobiol.Int.26,682–696

98 Cordova,C.A.etal.(2006)Sleepdeprivationinratsproducesattentional impairmentsona5-choiceserialreactiontimetask.Sleep29,69–76 99 McCoy,J.G.etal.(2007)Experimentalsleepfragmentationimpairs

attentionalset-shiftinginrats.Sleep30,52–60

100 Friedman,L.etal.(1979)Effectsofsleepdeprivationonsleepiness,sleep intensity,andsubsequentsleepintherat.Sleep1,369–391

101 Huber,R.etal.(2000)TopographyofEEGdynamicsaftersleep deprivationinmice.J.Neurophysiol.84,1888–1893

102 Tobler,I.andBorbely,A.A.(1990)Theeffectof3-hand6-hsleep deprivationonsleepandEEGspectraoftherat.Behav.BrainRes.36, 73–78

103 Guse,B.etal.(2010)Cognitiveeffectsofhigh-frequencyrepetitive transcranialmagneticstimulation:asystematicreview.J.NeuralTransm. 117,105–122

104 Sparing,R.andMottaghy,F.M.(2008)Noninvasivebrainstimulation withtranscranialmagneticordirectcurrentstimulation(TMS/tDCS)– frominsightsintohumanmemorytotherapyofitsdysfunction.Methods 44,329–337

105 Rudiak,D.andMarg,E.(1994)Findingthedepthofmagneticbrain stimulation:are-evaluation.Electroencephalogr.Clin.Neurophysiol.93, 358–371

106 Grafman,J.etal.(1994)Inductionofarecalldeficitbyrapid-rate transcranialmagneticstimulation.Neuroreport5,1157–1160 107 Rami,L.etal.(2003)Effectsofrepetitivetranscranialmagnetic

stimulationonmemorysubtypes:acontrolledstudy.Neuropsychologia 41,1877–1883

108 Rossi,S.etal.(2001)Prefrontalcortexinlong-termmemory:an ‘interference’approachusingmagneticstimulation.Nat.Neurosci.4, 948–952

109 Rossi,S.etal.(2006)rTMSforPTSD:inducedmercifuloblivionor eliminationofabnormalhypermnesia?Behav.Neurol.17,195–199 110 Rossi,S.etal.(2004)Age-relatedfunctionalchangesofprefrontalcortex

inlong-termmemory:arepetitivetranscranialmagneticstimulation study.J.Neurosci.24,7939–7944

111 Sandrini,M.etal.(2003)Theroleofprefrontalcortexinverbalepisodic memory:rTMSevidence.J.Cogn.Neurosci.15,855–861

112 Gagnon,G.etal.(2010)Paired-pulsetranscranialmagneticstimulation overthedorsolateralprefrontalcortexinterfereswithepisodicencoding andretrievalforbothverbalandnon-verbalmaterials.BrainRes.1344, 148–158

113 Floel,A.etal.(2004)Prefrontalcortexasymmetryformemoryencoding ofwordsandabstractshapes.Cereb.Cortex14,404–409

114 Mottaghy,F.M.(2006)Interferingwithworkingmemoryinhumans. Neuroscience139,85–90

115 Mottaghy,F.M.etal.(2002)Segregationofareasrelatedtovisualworking memoryintheprefrontalcortexrevealedbyrTMS.Cereb.Cortex12,369– 375

116 Oliveri,M.etal.(2001)Parieto-frontalinteractionsinvisual-objectand visual-spatialworkingmemory:evidencefromtranscranialmagnetic stimulation.Cereb.Cortex11,606–618

117 Sligte,I.G.etal.(2011)Magneticstimulationofthedorsolateral prefrontalcortexdissociatesfragilevisualshort-termmemoryfrom visualworkingmemory.Neuropsychologia49,1578–1588

118 Turatto,M.etal.(2004)Theroleoftherightdorsolateralprefrontal cortexinvisualchangeawareness.Neuroreport15,2549–2552 119 Wagner,M.etal.(2006)Repetitivetranscranialmagneticstimulationof

thedorsolateralprefrontalcortexaffectsdividedattentionimmediately aftercessationofstimulation.J.Psychiatr.Res.40,315–321

120 Feredoes,E.A.andSachdev,P.S.(2006)Differentialeffectsoftranscranial magneticstimulationofleftandrightposteriorparietalcortexonmental rotationtasks.Cortex42,750–754

121 Postle,B.R.etal.(2006)Repetitivetranscranialmagneticstimulation dissociatesworkingmemorymanipulationfromretentionfunctionsin theprefrontal,butnotposteriorparietal,cortex.J.Cogn.Neurosci.18, 1712–1722

122 Terao,Y.andUgawa,Y.(2006)Studyinghighercerebralfunctionsby transcranialmagneticstimulation.Suppl.Clin.Neurophysiol.59,9–17 123 Kessels,R.P.etal.(2000)Spatialworkingmemoryperformanceafter

high-frequencyrepetitivetranscranialmagneticstimulationoftheleft andrightposteriorparietalcortexinhumans.Neurosci.Lett.287,68–70 124 Szczepanski,S.M.andKastner,S.(2009)Transcranialmagnetic

stimulationstudiesofvisuospatialattentionalcontrol.F1000Biol.Rep.1, 81

125 Desmond,J.E.etal.(2005)Cerebellartranscranialmagneticstimulation impairsverbalworkingmemory.Ann.Neurol.58,553–560

126 Minks,E.etal.(2010)Transcranialmagneticstimulationofthe cerebellum.Biomed.Pap.Med.Fac.Univ.PalackyOlomoucCzechRepub. 154,133–139

127 Ilmoniemi,R.J.etal.(1999)Transcranialmagneticstimulation–anew toolforfunctionalimagingofthebrain.Crit.Rev.Biomed.Eng.27,241– 284

128 Bohning,D.E.etal.(2000)BOLD-fMRIresponsetosingle-pulse transcranialmagneticstimulation(TMS).J.Magn.Reson.Imaging11, 569–574

129 Fox,P.etal.(1997)Imaginghumanintra-cerebralconnectivitybyPET duringTMS.Neuroreport8,2787–2791

130 Ilmoniemi,R.J.etal.(1997)Neuronalresponsestomagneticstimulation revealcorticalreactivityandconnectivity.Neuroreport8,3537–3540 131 Komssi,S.etal.(2002)Ipsi-andcontralateralEEGreactionsto

transcranialmagneticstimulation.Clin.Neurophysiol.113,175–184 132 Paus,T.etal.(2001)Cortico-corticalconnectivityofthehuman

mid-dorsolateralfrontalcortexanditsmodulationbyrepetitivetranscranial magneticstimulation.Eur.J.Neurosci.14,1405–1411

133 Paus,T.etal.(1997)Transcranialmagneticstimulationduringpositron emissiontomography:anewmethodforstudyingconnectivityofthe humancerebralcortex.J.Neurosci.17,3178–3184

134 Siebner,H.R.etal.(2000)Lastingcorticalactivationafterrepetitive TMSofthemotorcortex:aglucosemetabolicstudy.Neurology54, 956–963

135 Strafella,A.P.andPaus,T.(2001)Cerebralblood-flowchangesinduced bypaired-pulsetranscranialmagneticstimulationoftheprimarymotor cortex.J.Neurophysiol.85,2624–2629

136 Mottaghy,F.M.etal.(2000)Modulationoftheneuronalcircuitry subservingworkingmemoryinhealthyhumansubjectsbyrepetitive transcranialmagneticstimulation.Neurosci.Lett.280,167–170 137 Mottaghy,F.M.etal.(2003)Modulationofabrain-behaviorrelationship

inverbalworkingmemorybyrTMS.BrainRes.Cogn.BrainRes.15, 241–249

138 Thut,G.etal.(2005)AnewdeviceandprotocolforcombiningTMSand onlinerecordingsofEEGandevokedpotentials.J.Neurosci.Methods141, 207–217

139 Ives,J.R.etal.(2006)Electroencephalographicrecordingduring transcranialmagneticstimulationinhumansandanimals.Clin. Neurophysiol.117,1870–1875

140 Cooper,N.R.etal.(2008)EffectsofrTMSonanauditoryoddballtask:a pilotstudyofcorticalplasticityandtheEEG.Clin.EEGNeurosci.39,139– 143

141 Iwahashi,M.etal.(2009)Effectoftranscranialmagneticstimulationon P300ofevent-relatedpotential.Conf.Proc.IEEEEng.Med.Biol.Soc.2009, 1359–1362

142 Okamura,H.etal.(2001)EEGmodificationinducedbyrepetitive transcranialmagneticstimulation.J.Clin.Neurophysiol.18,318–325 143 Schutter,D.J.etal.(2003)Highfrequencyrepetitivetranscranial

magneticoverthemedialcerebelluminducesashiftintheprefrontal electroencephalographygammaspectrum:apilotstudyinhumans. Neurosci.Lett.336,73–76

144 Li,W.etal.(2007)Effectofchronicandacutelow-frequencyrepetitive transcranialmagneticstimulationonspatialmemoryinrats.BrainRes. Bull.71,493–500

145 Ahmed,Z.andWieraszko,A.(2006)Modulationoflearningand hippocampal,neuronalplasticitybyrepetitivetranscranialmagnetic stimulation(rTMS).Bioelectromagnetics27,288–294

146 Kling,J.W.etal.(1990)Memoryforconditionedtasteaversionsis diminishedbytranscranialmagneticstimulation.Physiol.Behav.48, 713–717

147 Li,L.etal.(2007)Theinfluenceoflow-frequencyrTMSonEEGofrats. Neurosci.Lett.412,143–147

148 vanderPost,J.etal.(2002)Evaluationoftestsofcentralnervoussystem performanceafterhypoxemiaforamodelforcognitiveimpairment.J. Psychopharmacol.16,337–343

149 Noble,J.etal.(1993)Cognitivefunctionduringmoderatehypoxaemia. Anaesth.IntensiveCare21,180–184

150 Berry,D.T.etal.(1989)Isocapnichypoxemiaandneuropsychological functioning.J.Clin.Exp.Neuropsychol.11,241–251

151 Green,R.G.andMorgan,D.R.(1985)Theeffectsofmildhypoxiaona logicalreasoningtask.Aviat.SpaceEnviron.Med.56,1004–1008 152 Paul,M.A.andFraser,W.D.(1994)Performanceduringmildacute

hypoxia.Aviat.SpaceEnviron.Med.65(Pt1),891–899

153 Kida,M.andImai,A.(1993)Cognitiveperformanceandevent-related brainpotentialsundersimulatedhighaltitudes.J.Appl.Physiol.74, 1735–1741

154 Tsarouchas,N.etal.(2008)Effectsofmoderatehypobarichypoxiaon evokedcategoricalvisuocognitiveresponses.Clin.Neurophysiol.119, 1475–1485

155 Elmenhorst,D.etal.(2009)Performanceimpairmentduringfourdays partialsleepdeprivationcomparedwiththeacuteeffectsofalcoholand hypoxia.SleepMed.10,189–197

156 Fowler,B.etal.(1987)Theeffectsofhypoxiaonreactiontimeand movementtimecomponentsofaperceptual-motortask.Ergonomics30, 1475–1485

157 Fowler,B.etal.(1982)Theeffectsofhypoxiaonserialresponsetime. Ergonomics25,189–201

158 Saletu,B.etal.(1996)Effectsofthenovelneuroprotectiveagent,riluzole, onhumanbrainfunctionandbehavior:II.Double-blind, placebo-controlledEEGmappingandpsychometricstudiesunderhypoxia. MethodsFind.Exp.Clin.Pharmacol.18,67–81

159 VanDorp,E.etal.(2007)Inspiredcarbondioxideduringhypoxia:effects ontaskperformanceandcerebraloxygensaturation.Aviat.SpaceEnviron. Med.78,666–672

160 Kraaier,V.etal.(1988)QuantitativeEEGchangesduetohypobaric hypoxiainnormalsubjects.Electroencephalogr.Clin.Neurophysiol.69, 303–312

161 Saletu,B.etal.(1990)Brainprotectionofnicergolineagainsthypoxia: EEGbrainmappingandpsychometry.J.NeuralTransm.Park.Dis. Dement.Sect.2,305–325

162 VanderWorp,H.B.etal.(1991)QuantitativeEEGduringprogressive hypocarbiaandhypoxia.Hyperventilation-inducedEEGchanges reconsidered.Electroencephalogr.Clin.Neurophysiol.79,335–341 163 Fowler,B.andPrlic,H.(1995)Acomparisonofvisualandauditory

reactiontimeandP300latencythresholdstoacutehypoxia.Aviat.Space Environ.Med.66,645–650

164 Thakur,L.etal.(2011)Eventrelatedpotential(ERP)P300after6months residenceat4115meter.IndianJ.Med.Res.134,113–117

165 Wesensten,N.J.etal.(1993)Effectsofsimulatedhighaltitudeexposure onlong-latencyevent-relatedbrainpotentialsandperformance.Aviat. SpaceEnviron.Med.64,30–36

166 Binks,A.P.etal.(2008)Graymatterbloodflowchangeisunevenly distributedduringmoderateisocapnichypoxiainhumans.J.Appl. Physiol.104,212–217

167 Buck,A.etal.(1998)Changesofcerebralbloodflowduringshort-term exposuretonormobarichypoxia.J.Cereb.BloodFlowMetab.18,906–910 168 Pagani,M.etal.(2000)Effectsofacutehypobarichypoxiaonregional cerebralbloodflowdistribution:asinglephotonemissioncomputed tomographystudyinhumans.ActaPhysiol.Scand.168,377–383 169 Pagani,M.etal.(2011)Impactofacutehypobarichypoxiaonbloodflow

distributioninbrain.ActaPhysiol.(Oxf.)202,203–209

170 Hochachka,P.W.etal.(1991)Metabolicandworkefficienciesduring exerciseinAndeannatives.J.Appl.Physiol.70,1720–1730

171 Shukitt-Hale,B.etal.(1996)Morphologicalalterationsinthe hippocampusfollowinghypobarichypoxia.Hum.Exp.Toxicol.15, 312–319

172 Shukitt-Hale,B.etal.(1994)Hypobarichypoxiaimpairsspatialmemory inanelevation-dependentfashion.Behav.NeuralBiol.62,244–252 173 Barhwal,K.etal.(2009)Acetyl-l-carnitine(ALCAR)preventshypobaric

hypoxia-inducedspatialmemoryimpairmentthroughextracellular

relatedkinase-mediatednuclearfactorerythroid2-relatedfactor2 phosphorylation.Neuroscience161,501–514

174 Barhwal,K.etal.(2007)Acetyl-L-carnitineameliorateshypobaric hypoxicimpairmentandspatialmemorydeficitsinrats.Eur.J. Pharmacol.570,97–107

175 Hota,S.K.etal.(2009)Bacopamonnieraleafextractameliorates hypobarichypoxiainducedspatialmemoryimpairment.Neurobiol.Dis. 34,23–39

176 Hota,S.K.etal.(2008)Ceftriaxonerescueshippocampalneuronsfrom excitotoxicityandenhancesmemoryretrievalinchronichypobaric hypoxia.Neurobiol.Learn.Mem.89,522–532

177 Hota,S.K.etal.(2007)Differentialtemporalresponseofhippocampus, cortexandcerebellumtohypobarichypoxia:abiochemicalapproach. Neurochem.Int.51,384–390

178 Jayalakshmi,K.etal.(2007)N-acetylcysteinesupplementationprevents impairmentofspatialworkingmemoryfunctionsinratsfollowing exposuretohypobarichypoxia.Physiol.Behav.92,643–650

179 Maiti,P.etal.(2008)Hypobarichypoxiainducesdendriticplasticityin corticalandhippocampalpyramidalneuronsinratbrain.Behav.Brain Res.189,233–243

180 Muthuraju,S.etal.(2009)Acetylcholinesteraseinhibitorsenhance cognitivefunctionsinratsfollowinghypobarichypoxia.Behav.BrainRes. 203,1–14

181 Shukitt-Hale,B.etal.(1996)Tyrosineadministrationprevents hypoxia-induceddecrementsinlearningandmemory.Physiol.Behav.59,867–871 182 Titus,A.D.etal.(2007)Hypobarichypoxia-induceddendriticatrophyof hippocampalneuronsisassociatedwithcognitiveimpairmentinadult rats.Neuroscience145,265–278

183 Zhang,J.X.etal.(2006)Intermittenthypoxiaimpairsperformanceof adultmiceinthetwo-wayshuttleboxbutnotintheMorriswatermaze.J. Neurosci.Res.84,228–235

184 Udayabanu,M.etal.(2008)NitricoxideassociatedwithiNOSexpression inhibitsacetylcholinesteraseactivityandinducesmemoryimpairment duringacutehypobarichypoxia.BrainRes.1230,138–149

185 Bekker,A.etal.(2007)Physostigminereversescognitivedysfunction causedbymoderatehypoxiainadultmice.Anesth.Analg.105, 739–743

186 Bekker,A.etal.(2006)Isofluranepreservesspatialworkingmemoryin adultmiceaftermoderatehypoxia.Anesth.Analg.102,1134–1138 187 Haile,M.etal.(2009)Nimodipinepreventstransientcognitive

dysfunctionaftermoderatehypoxiainadultmice.J.Neurosurg. Anesthesiol.21,140–144

188 Viu,E.etal.(2000)Glycine(B)receptorantagonistsandpartialagonists preventmemorydeficitsininhibitoryavoidancelearning.Neurobiol. Learn.Mem.74,146–160

189 Platt,B.etal.(2010)EpiduralEEGrecordingsusingmicrochipsin behaviouralcontext.ProceedingsofMeasuringBehavior

190 Ravasi,L.etal.(2011)Useof[18F]fluorodeoxyglucoseandtheATLAS smallanimalPETscannertoexaminecerebralfunctionalactivation bywhiskerstimulationinunanesthetizedrats.Nucl.Med.Commun.32, 336–342