IMPACT MEASUREMENT FOR SOCIAL BANKING:

THE CASE OF BANCA ETICA

Ph.D. Thesis presented by:

Alberto Boem

Tutor and Supervisor:

Andrea Piccaluga

Doctoral Degree in Management of Innovation,

Healthcare and Sustainability

Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna

Academic Year 2016-2017

2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS – RINGRAZIAMENTI

Questa tesi è il frutto accademico di un progetto personale basato sulla costante integrazione tra esperienza lavorativa e ricerca universitaria, iniziato esattamente quattro anni fa con il mio ingresso in Banca Etica. In questi anni ho affiancato la stesura di questo scritto ad un progetto sul campo che ne ha applicato i contenuti e che vedrà (incrociando le dita!) anch’esso il suo compimento tra pochi mesi. Questa tesi ha quindi a sua volta beneficiato dei continui apporti e stimoli derivanti dall’attività quotidiana del mio lavoro in banca. Sono sempre stato profondamente convinto del valore della ricerca applicata sul campo: questa convinzione ha guidato il mio lavoro in questi anni, lavoro che spero rappresenti un buon esempio di questo modo di intendere la ricerca.

Il poter coniugare ricerca accademica e l’attività sul campo è stato quindi per me un privilegio e una fonte di grande motivazione personale. Non è però un percorso sempre semplice, sicuramente nel mio caso a tratti non è stato lineare. In qualche momento ho anche onestamente dubitato di riuscire a portarlo a termine. Il supporto e l’aiuto di molte persone mi hanno però consentito di arrivare alla sua conclusione. E’ quindi con loro che condivido questo traguardo e che ringrazio sinceramente di cuore.

Ringrazio il professor Andrea Piccaluga per avermi consentito di iniziare questo percorso e per l’aiuto nel portarlo a termine. Ringrazio la professoressa Silvana Signori per la sua gratuita disponibilità e i suoi preziosi consigli. Thanks to professor Katrin Kaeufer for the revision and recognition of my work, it meant a lot to me.

Ringrazio Agnese per il fondamentale aiuto nella raccolta dei dati.

Grazie a Margherita per il lavoro sulle grafiche, regalo di una profonda amicizia.

Grazie a Paolo, Roberta e Gloria per aver sempre creduto in me fin dall’inizio, per la comprensione e il supporto costante, per gli stimoli e le opportunità che non mi avete mai fatto mancare. Grazie ai miei colleghi della filiale di Brescia e dell’ufficio fidi per avermi fatto sempre sentire il vostro sostegno, anche e soprattutto quando questo ha significato un maggior carico di lavoro per voi. Banca Etica è Banca Etica perché vi sono persone come tutte e tutti voi.

3 Grazie a Francesco, fratello e amico, e a tutti i miei amici: la gioia, la serenità e il divertimento che abbiamo condiviso sono stati un carburante fondamentale di questo percorso.

Grazie a tutta la mia famiglia e (ripetendomi) non c’è bisogno di dire perché. Grazie a tutti voi, non è stato solo un percorso professionale.

4

INTRODUCTION

The aim of this work is to propose a methodology for measuring the impact of social banks. Impact measurement is an issue strongly debated in the current literature. This work contributes to the discussion by focusing on the case of social banking. Social banking is defined as using finance as a tool for social and ecological change. Impact measurement for social banks presents some specific peculiarities that are not taken into account by the current impact measurement methodologies, like the SROI and the GIIRS.

Impact measurement is fundamental for social banks for two reasons: accountability and internal control. Social banks must be able to provide evidence of impact creation to their stakeholders because their core business model is based on the assumption that they provide this impact beyond financial sustainability. Morevoer, impact measurement is a tool to make sure that their money are producing impact, according to the final mission of social banking. At this moment, a commonly accepted methodology for measuring impact for social banks does not exist. Literature about this issue is very limited and at its first stages. Practitioners’ methodologies do not consider some fundamental aspects for impact measurement, like deadweight and attribution issues.

Given these premises, I decided to use a qualitative case analysis as my research methodology. Case analysis indeed is particularly suitable for theory building. I specifically adopted the methodology proposed by Carson et al. (2001). I selected the case of Banca Etica, an Italian social bank belonging to the most important networks of social banks, like the Global Alliance on Banking on Values and the European Federation of Ethical and Alternative Banks.

The impact measurement methodology that I am suggesting with this thesis is made by three components: a set of impact areas, a corresponding set of indicators and a system of data aggregation. This thesis is based on the following methodological approach. In a first step, I conducted an analysis of the loan portfolio of Banca Etica to identify the impact areas. Through the help of some preliminary convergent interviews to the managers of Banca Etica, I built an initial proposal of a set of indicators and a system of data aggregation. In a second step, I discussed this proposal during several in-depth interviews with social

5 entrepreneurs, academics and managers. Thirdly, based on the outcome of the in-depth interviews, I built a final methodology for impact measurement for social banks. Finally, I tested this methodology by using real data from Banca Etica and by carrying a survey among its employees, members and directors.

The main contribution of this work is a comprehensive and consistent methodology for impact measurement for social banking. Specifically, I was able to identify and test a set of indicators among the ones currently proposed by the literature for several impact areas. The proposed impact measurement methodology consists of tools that can be used for both accountability and internal control aims. Moreover, the methodology takes into account the issues of deadweight and attribution, addressing a lack in the literature. Finally, this methodology is a useful tool for tackling some strategic goals for social banks like impact creation, credit access and influence on the economic system. It can also be used for mitigating credit risk and for credit planning.

This work has the following structure. Chapter 1 defines the concept of social banking, impact and, consequently, impact for social banking. Chapter 2 states the research question, discussing its relevance, and describes the research methodology. Chapter 3 is dedicated to the literature review: general literature about impact measurement and specific literature about impact measurement for social banking are explored. Chapter 4 reports and discusses the results of the loan portfolio analysis of Banca Etica and of the convergent interviews. Chapter 5 describes the in-depth interviews: it illustrates the interview protocol and reports the main findings. Chapter 6 and Chapter 7 illustrate the final proposal of the methodology. Chapter 6 in particular concerns the first two components of the methodology: the selected impact areas and indicators are listed. This chapter also includes the results of the survey. Chapter 7 illustrates the system of data aggregation using real data from Banca Etica and discusses its features and results. Chapter 8 reports the conclusions, the limitations of the research and the suggestions for further research.

6

SUMMARY

CHAPTER 1: DEFINITIONS OF SOCIAL BANKING, IMPACT AND IMPACT IN SOCIAL BANKING... 7

What is social banking? ... 7

What is impact? ... 12

Impact for social banking ... 14

CHAPTER 2: RESEARCH QUESTION AND METHODOLOGY ... 16

Research question and its relevance ... 16

Research methodology ... 19

CHAPTER 3: LITERATURE REVIEW ... 24

Impact measurement in general ... 24

Literature about impact measurement methodologies ... 25

Impact measurement methodologies for social banking ... 30

Literature review conclusions ... 34

CHAPTER 4: CONVERGENT INTERVIEWS AND LOAN PORTFOLIO ANALYSIS ... 35

Convergent interviews and loan portfolio analysis’ goals ... 35

Convergent interviews ... 36

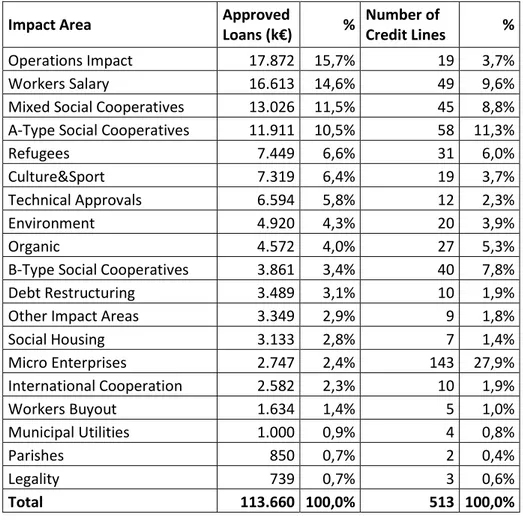

Loan portfolio analysis ... 39

CHAPTER 5: IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS ... 44

In-depth interviews setting and goals ... 44

In-depth interviews results ... 49

CHAPTER 6: IMPACT AREAS AND INDICATORS - RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ... 52

Impact areas and indicators ... 52

Survey setting and results ... 54

CHAPTER 7: SYSTEM OF DATA AGGREGATION - RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ... 58

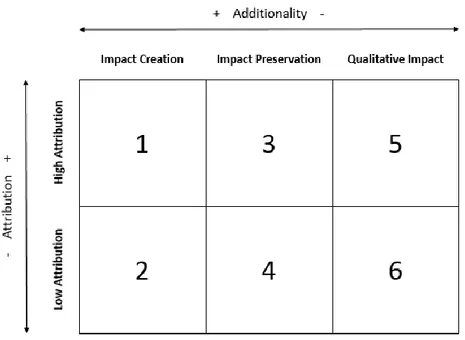

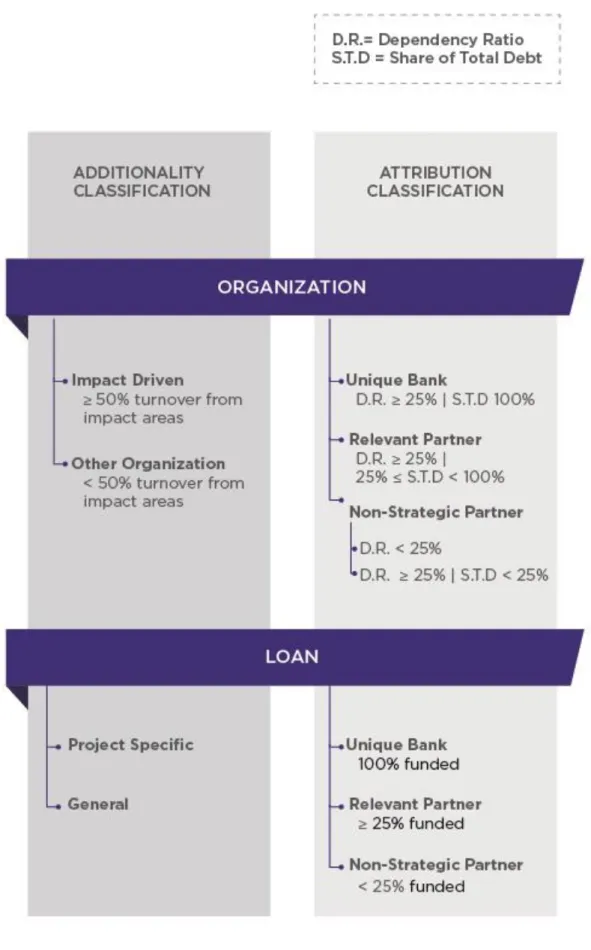

Classification of organizations and loans ... 58

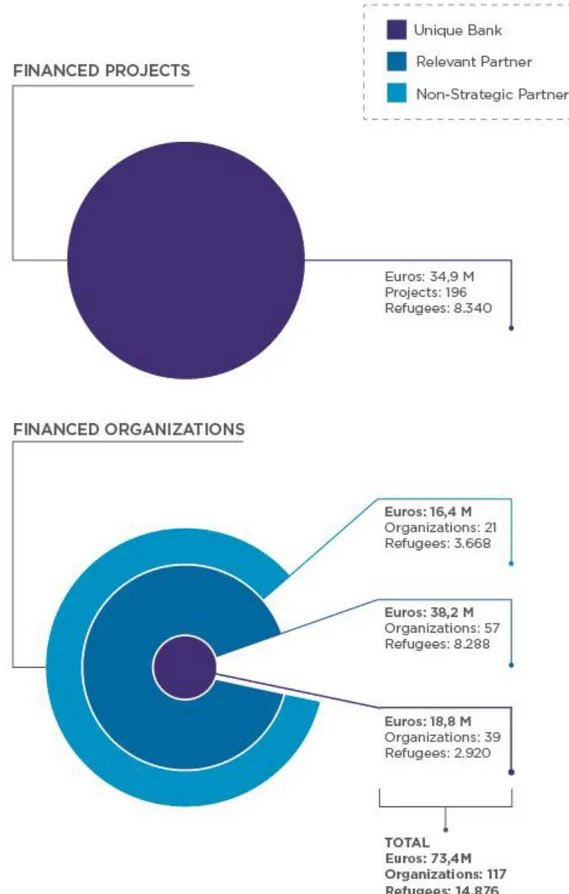

Impact targets ... 62

Impact map ... 65

CHAPTER 8: CONCLUSIONS... 72

7

CHAPTER 1: DEFINITIONS OF SOCIAL BANKING, IMPACT AND IMPACT IN SOCIAL BANKING

This first chapter defines the concepts of social banking and impact in general. It then defines the concept of impact for social banking.

What is social banking?

A brief history

The idea of banking for the need of society is as old as banking itself. This idea has assumed different connotations through history. Several authors consider social banking as its modern approach and as the final destination of a long stream of theories and conceptions; “It (social banking) stands in a historical line of continuous search for the application of ethical principles in banking” (De Clerck, 2009). According to a significant stream of the literature, the first origin of social banking is rooted in the doctrine of the Franciscan monk San Bernardino da Siena (Milano, 2011). San Bernardino inspired the foundation of the first Monte di Pietà in Ascoli Piceno in 1458, a medieval institution operating credit activities on a non-profit basis. The same focus on social issues can be found in the birth of the cooperative banks during the Nineteenth Century in their two forms. Cooperative banking developed in two ways: popular banks, founded by Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch at around 1850 and rural banks, founded in 1862 by Friedrich W. Raiffeisen.

Current social banks started to appear during the 70s and the 80s of the 20th century in the Continental

Europe, based on anthroposophy. The theoretical foundation of these banks directly refers to the ideas of Rudolph Steiner (1861-1925). In the idea of Steiner, money is a mere tool and not a good to be hoarded. It must be functional to real economy. In the following years, social banks were established all around the world: they do not necessarily refer to Steiner’s idea, even if it is possible to find a common humanistic philosophical background.

8 Social banking gained a significant attention especially after the financial crisis of 2008. The crisis aroused a strong blame about the behavior of banks and the systemic role of the banking sector in general. According to Benedikter (2011), during that period, social banks have increased their assets with a growth rate of about 20-25% per year. Notwithstanding this remarkable performance, it must be acknowledged that social banks still account for a truly small fraction of the banking system. To give an idea, the biggest European social bank, Triodos Bank, has total assets under management of €13,4 billions and 1.271 employees (Triodos Bank, 2016). ABN AMRO, one of the biggest banks in the Netherlands, accounts for €322,7 billion as client assets and roughly 21.000 employees (ABN AMRO, 2016). Nonetheless, the dynamism and principles of social banks are starting to affect the entire banking system. This is what makes social banking an interesting research subject.

Today, it is possible to identify a list of banks that can be considered as “core” social banks (Weber & Remer, 2011). They belong to three main networks: the Global Alliance on Banking on Values (GABV), the Institute for Social Banking (ISB) and the European Federation of Ethical and Alternative Banks (FEBEA – Fédération Européenne des Banques Ethiques et Alternatives). These networks have the common goals of connecting social banks, by sharing learning and experiences, and of trying to influence traditional banking sector and its regulation. The ISB and Febea operate at European level, while members from all around the world compose the GABV.

The GABV was founded in 2009 and “its collective goal is to change the banking system so that it is more transparent, supports economic, social and environmental sustainability, and is composed of a diverse range of banking institutions serving the real economy” (Global Alliance for Banking on Values, 2017). As of March 2017, the Global Alliance comprises 40 financial institutions operating across countries in Asia, Africa, Australia, Latin America, North America and Europe. They serve more than 24 million customers, hold up to $110 billion USD of combined assets under management and collectively have a cohort of more than 42.000 co-workers.

9 The Institute for Social Banking was founded in 2006 and started with 10 ethical banks. Today it has 15 members in 12 different countries. Its goal is to “promote a concept of finance and banking that specifically orients itself towards a perception of and responsibility for the development of both people and planet” (Institute for Social Banking, 2016). Its focus is on the research and educational side: it promotes research activities on the issue of social banking and organizes courses and workshops, in particular the Summer School on Social Banking at annual basis.

FEBEA is a non-profit organisation incorporated under belgian law, created in Brussels in 2001 by Crédit Coopératif (France), Caisse Solidaire du Nord Pas-de-Calais (France), Crédal (Belgium),Hefboom (Belgium), Banca Etica (Italy), TISE (Poland) and La Nef (France). Today is composed by 11 banks, 6 savings and loan cooperatives, 5 investment companies and 3 foundations that together account for a balance sheet of 21 billion euros and have some 528 000 clients and shareholders between them (Febea, 2016). FEBEA has developed diversified tools: the guarantee fund "Solidarity Guarantee", the investment fund "Solidarity Choice" and the financing company 'SEFEA" (Société Européenne de Finance Ethique et Alternative).

Definition of Social Banking

Modern literature has not reached a common definition of social banking, as also clearly stated in Weber & Remer (2011). Udo Reifner from Hamburg University gave the first recognized definition: “Social banks is banking that fights poverty” (Reifner & Ford, 1992). This approach clearly reflects the very first origin of social banking, but it is not sufficiently comprehensive. Indeed, the majority of social banks are focused on social innovation, environment and community development in a broader sense. This definition reflects the difference between social banks in the North of the world, the so-called ethical banks, and the ones in the South, the poverty alleviation banks. The difference in the mission is clearly due to the context in which banks operate, but it is also possible to find distinctive approach in the funding and organizational structure (Scheire & de Maertelaere, 2009).

Having considered this issue, Benedikter (2011) tries to identify the fundamental features that are useful to define social banking, narrowing down to three ones. The first one arises from the words of Frans De

10 Clerck, co-founder of Triodos Bank: “Social, ethical, alternative, sustainable, development and solidarity banking and finance are denominations that are currently used to express particular ways of working with money, based on non-financial deliberations (…) The private sector and financial institutions in particular are increasingly expected to play an important role in helping to create a truly sustainable world. Conscious consumers, ethical investors, enlightened businesses, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), cultural creators and lending international institutions are working to make a triple bottom line (People, Planet and Profit) a reality” (De Clerck, 2009). Traditional banks judge investment and lending opportunities with a single bottom line, such as profits. The first distinctive feature of social banks instead is that they take into account three different criterions, such as profit, environment and people. Social banks need to avoid losses in order to guarantee the economic sustainability of their business, but also take into account the environmental and social effects of their investment. This can translate, according to the peculiarity of each institute, into the exclusion of some investment sectors (e.g. weapons, gambling) or into a social and environmental evaluation of the loans that has the same importance of the economic one.

The second feature identified by Benedikter is transparency. Social banks usually publish on their reports or websites the list of the loans given to organizations. The underlying idea is that customers are able to know where their money go and what they are used for. They can advise the bank about its investment and credit policies and, in some cases, even challenge them. Considering retail customers, social banks try to communicate clearly conditions and costs of their products. They take into account the actual needs and specificities of their customers while selling financial products. The third and core feature of social banking is that its final aim is to pursue human development. Money is used as an instrument for producing social change and it is not considered as a goal. A common motto of social banks is “People before money!”: profits are considered as a mean for self-sustainability rather than an objective (Becchetti, Garcia, & Trovato, 2011). To summarize these concepts in the words of Benedikter (2011), “social banks consider themselves as “catalysts for social change” without the primacy of profit” and “social banking and social finance are about “bringing money back to real life in the real economy”. The author therefore proposes, among others, the following definition of social banking: “Social banking we define as where suppliers of

11 financial services take a positive interest in the social outcomes and effects of their activities” (Guene & Mayo, 2001).

Other definitions are proposed by the main networks of social banks, in particular the Global Alliance for Banking on Values (GABV) and, the Institute for Social Banking (ISB). According to the ISB, “Social banking describes the provision of banking and financial services that consequently pursue, as their main objective, a positive contribution to the potential of all human beings to develop, today and in the future” (Institute for Social Banking, 2016). Considering the fact that is not possible to provide a unique definition of social banking, it also provides several characteristics, which are common to all social banks.

The GABV proposes six fundamental features in order to qualify as social bank (Global Alliance for Banking on Values, 2016):

1) A triple bottom approach consisting in focusing simultaneously on people, environment and profitability; 2) A focus on financing the real economy, in particular the needs of communities;

3) The creation of long-term relationships with clients, also in order to assist them in becoming more sustainable;

4) The adoption of a long-term perspective in order to guarantee the maintenance of its business; 5) Transparency and inclusiveness in governance;

6) The fact that the preceding principles must be embedded in the culture of the bank, especially in human resources policies.

As it is possible to see, there is the same focus on the concepts of triple bottom line approach, real economy and transparency as for Benedikter. In line with James Niven, from the GABV, Weber and Remer (2011) define social banking “as banking that aims to have a positive impact on people, the environment and culture by means of banking, i.e. savings account, loans, investments and other banking products and services, including “gift money””. In this definition, there is a strong focus on the concept of impact and a strict connection with the one proposed by the ISB. For this reasons, this is the definition of social banking that is adopted by this work.

12

What is impact?

To define impact for social banking, it is previously necessary to introduce the concept of impact in general. In this chapter, I only touch upon this issue that is further explored in the literature review section. Academic literature proposes a vast set of definitions of social impact or similar concepts like social value (Emerson et al., 2000) and social return (Clark et al., 2004). The issue could be the subject of a dedicated research, but this is out of the scope of this work. The approach that is commonly adopted in the specific literature of impact assessment for social banking (Altis, 2015) is based on the Theory of Change framework (Weiss, 1972). This literature acknowledges that every definition includes the idea that impact relates to the change that is produced by the actions undertaken by an organization. The change can involve many fields like environment, health, people wellbeing and way of life etc. and it is connected by causal linkages to the actions. This idea is at the basis of the most popular conceptual framework that is used to measure impact, the Impact Value Chain. This is the starting point of many practical tools, such as for instance the Social Return on Investment (Nicholls et al., 2009). Therefore, among the most popular definitions, it is possible to choose the one proposed by Clark et al. (2004): “by impact we mean the portion of total outcome that happened as a result of the activity of a venture, above and beyond what would happened anyway”. This definition is coherent with the explained conceptual framework and with the definition of social banking. Social baking definition, indeed, is also based on the concept of change.

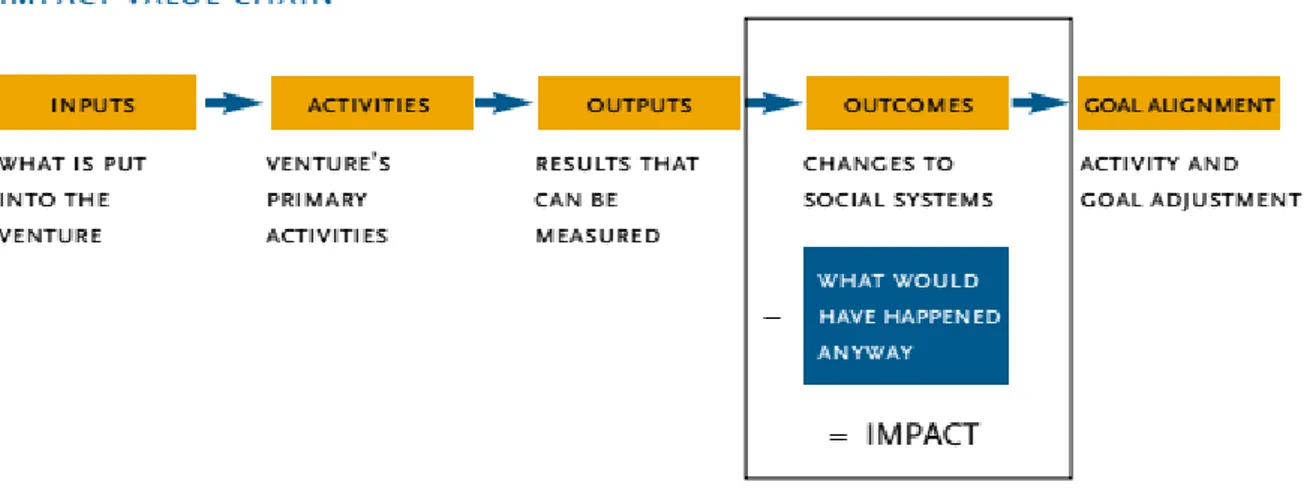

After having defined impact, it is possible to analyze the impact value chain with more details. The most popular description is the one of Nicholls et al. (2009) in their guide of the SROI. Inputs and activities are the starting points of the chain. Inputs are what stakeholders are contributing in order to make the activity possible. Inputs can be time, goods, money and are used to carry the activities of an organization. Outputs are the quantitative summary of an activity. Nicholls et al. (2009) propose as an example of output, the case of a training organization whom output is the number of people that have followed classes. The fundamental feature of an output is that it has to be measurable in quantitative terms. Outcomes instead are seen as results of the activities of the organization. It is not straightforward to distinguish between outputs and outcomes. Getting back to the previous example, if a training program aims to get people into

13 jobs then completion of the training itself is an output. Getting the job, instead, is an outcome. In other words, outcomes are the changes that the organization aims to achieve and usually correspond to its mission. There are many kinds of outcomes and lots of them can also correspond to very generic concept like for instance social inclusion, health improvement or personal satisfaction. A big part of the work of impact measurement is then to identify suitable indicators to quantify them. This issue is further discussed in the literature review chapter.

Figure 1: Impact value chain (from Nicholls et al., 2009)

Even if outcomes correspond to the last part of the chain, there is a further step to take to get to impact. It is necessary to make sure that outcomes are the actual results of the activities of an organization. According to Nicholls et al. (2009) impact is “the proportion of the outcome that can be isolated as being added by your activities”. In other words, it must be that the measured outcomes would not have happened anyway. In order to do so, the abovementioned authors identify three components that must be taken into account: deadweight, attribution and displacement. Deadweight accounts for outcome that would have happened without the activity in question being performed or not. Attribution accounts for how much of the actual outcome that was caused by the activity, in relation to what other organizations and activities might have contributed with. Displacement is to control for whether the outcome crowd out

14 or disturb other outcomes. These issues significantly affects impact measurement for social banking; they are further explored in the prosecution of the work.

Impact for social banking

Having introduced the general concept of impact, it is possible to define it for social banks. First of all, it is necessary to clarify the relation between impact and corporate social responsibility. A bank can create impact that is connected to its internal processes and its policies regarding, for instance, environment, human resources or suppliers. To give an example, it is possible to measure energy savings from the use of solar panels or the wellbeing of the people working for the bank. This kind of measurement is performed also by traditional banks and is connected with their corporate social responsibility policies. Social banks generate this kind of impact too, but it accounts only for a small fraction of the total impact.

Another concept that is close to impact in social banking is the one of externality. Indeed, social banks can affect the behavior of society and the banking system through the messages that convey. Social banks try to promote financial education of their customers, with a special focus on the aspects of sustainability. Moreover, they spread certain values to the customers that in turn can affect their behavior when dealing with the traditional banking system. People, for instance, can start to ask for sustainable banking products, like ethical funds. One of the goal of social banking, indeed, is to contaminate the whole banking system. Social banking tries to change the discussion in the field of banking, producing therefore positive externalities. How to measure such externalities is an interesting and fascinating research question that requires a specific research focus. Although, it is out of the scope of the current work.

According to the literature about impact measurement in social banking, indeed, the vast majority of the impact of social banks must be found in their core activities, especially in the lending one (Altis, 2015; Bosheim, 2012). Banks have a fundamental role in the society as credit providers. Their choices are able to determine which sectors and organizations will grow and develop and the ones that will not, due to lack of capital resources. Therefore, it is necessary to focus on the impact of the lending activity of social banks.

15 That means taking into account the systemic role of banks in general and the essence of social banks, that is to create a positive impact on society and environment. In this view, the impact of social banks is an indirect one and it is strictly connected with the impact produced by the financed organizations. Social banks are basically seen as “enabler” of impact. This approach is also chosen by practitioners (Triodos Bank, 2016) that tend to overlap their impact with the one of their loan portfolio. This work adopt this interpretation and therefore focuses on the measurement of the impact of the social banks’ lending activity to the real economy. Therefore, in the prosecution of this work, when I say “impact of social banks”, I specifically mean “impact of the lending activity of social banks”.

16

CHAPTER 2: RESEARCH QUESTION AND METHODOLOGY

This chapter states the research question and discuss its relevance and originality. In doing so, it identifies the features that make impact measurement for social banking a specific field of research. It then explains the research methodology, starting from its theoretical foundation. It later discusses the reasons for choosing case analysis as research methodology and Banca Etica as specific case. It concludes by describing the research methodology in details.

Research question and its relevance

In the previous chapter, I defined the concept of impact for social banking. It is now therefore possible to state my research question, which is:

“How to measure the impact of social banks?”

The goal of my research is therefore to provide a methodology to measure the impact of social banks. As explained in the previous chapter, the focus is on the impact of the loan activity of social banks. That clearly translates into the need of measuring their loan portfolio impact. It would be not sufficient to propose a measurement methodology that merely results into the sum of the impact of each single loan of a social bank. The concept of impact of social banks explained in the previous section has a broader scope. It takes into account also the extent of the bank role in the creation of the impact, the role of the bank as enabler. This issue must be therefore considered in some way in every proposed measurement methodology. Why is it relevant to measure impact for social banks? There are basically two reasons that refer to different actors (Emerson & Bonini, 2005): accountability to external stakeholders and internal control. Accountability and internal control are tasks for any organization, be it full-profit or non-profit.: it is the need to provide evidence of the created impact. Bank stakeholders must be sure to deal with an impact-creation organization. This is particularly relevant for social banks because they have a strong commitment to transparency in their mission. Moreover, their core business model is based on the assumption that they

17 are creating a positive impact in comparison to other players in the financial sector. Accountability is due to depositors and to owners of the bank because they need to know where their money go and how effectively are used. Professional investors require this kind of information in order to justify the investments in the bank to their customers. General statements or storytelling are not sufficient to accomplish this goal. The final goal of a social bank is to create impact. From a managerial perspective, it is fundamental to measure it in order to understand if the bank is reaching its goal. A very famous statement goes as “you cannot manage what you cannot measure”: this is exactly the case for impact in social banking. Measuring impact is the first step in order to be able to maximize it. Failing to do so exposes social banks to a strategic risk: not only impact creation is a goal for a social bank, but also the justification of its existence. Depositors must perceive the difference of giving money to a social bank rather than to a traditional one. They choose social banks because they want their money to create impact. A social bank manager must therefore make sure that the bank is actually achieving this goal. The starting point for controlling this goal is to have a methodology to measure it. Measurement, moreover, is the starting point for any decision making.

The research topic of impact measurement in social banking is recent and rather unexplored by the literature. There is of course a vast literature about impact measurement in general that provides some useful insights. However, impact measurement in social banking presents several characteristics that makes it a specific area of research:

1) Social banks finance a multiplicity of typologies of organizations working in different impact areas. A significant amount of literature about impact measurement focuses instead on entities that work in a single sector. This literature does not take into account the need and complexity of aggregating data from different sectors;

2) Each social bank finances on average hundreds or thousands of organizations. It is not possible therefore to refer completely to the literature about impact measurement at project level. It is not possible to carry this kind of analysis for a such significant amount of entities;

18 3) Given the fact that social banks are, by definition, banks, they provide completely different typologies of credit with different purposes. A fundamental distinction must be made between long-term capital and working capital: the former is usually dedicated to a specific goal or investment, while the latter covers the generic liquidity needs of an organization. This distinction must be taken into account while dealing with impact measurement: a measurement framework for social banks must consider both kind of capital. Traditionally, impact measurement literature does not consider working capital and its relation with long-term capital in an impact measurement methodology;

4) There are many kinds of organizations that measure their impact. Each kind refers to a specific stream of literature about the issue, but they all differ from social banks for at least one fundamental reason. A social bank, from an impact measurement point of view, is not a traditional bank. In addition to financial performance, it also has social and environmental aspects to be considered. It is not therefore possible to apply the traditional frameworks of performance measurement of the banking sector. Social banks cannot be compared to social enterprises. They both operate with the intent of generating impact, but they do it in a completely different manner, indirectly the formers and directly the latters. Social banks differs from microcredit institutions because the latter usually finance only natural people or very small enterprises. Social banks also finance medium and large enterprises. Impact funds traditionally use impact measurement in order to select the projects to finance among many proponents. Social banks do not have this need: they are actually struggling to find enough impact projects to lend money to (Weber & Remer, 2011). Moreover, impact funds and microcredit institutions are often the only lenders of an organization, while social banks operate in a competitive arena. Finally, social banks differ from sustainable, responsible or ESG (Environmental, Social & Governance) funds because these funds, even applying some exclusion criteria, invest in traditional listed companies, while social banks lend to impact enterprises.

In the previous paragraphs, I have tried to explain why impact measurement for social banking is a specific field of research and why my research question is relevant. I now briefly discuss its originality. Social banks have only recently started to measure their impact. A stream of literature has therefore begun to develop on the subject (Altis, 2015; Bosheim, 2012; Ballesteros & Herden, 2013). I analyze this literature in the next

19 chapter. For the purpose of this discussion, I can anticipate that the literature so far has not developed a rigorous and widely accepted framework for measuring impact in social banking. What has been done is basically a review of the existing methods used by the practitioners, the identification of impact areas and a collection of possible indicators for each area. What is still to be done is to identify the most relevant indicators and, most of all, integrate them into a clear measurement framework that takes into account also the role of social banks as enablers of impact. This work has the goal to cover this lack in the current literature by asking to the aforementioned research question. In doing so, it aims to contribute to the whole debate about impact measurement, providing useful insights that can be applicable also to other kind of institutions.

Research methodology

Foundations of the methodology

The aim of this work is to build a methodology for measuring impact. Building a new theory or a new methodology implies to adopt an inductive approach to research. Indeed, the current state of the literature on the subject does not allow for theory testing yet. What is rather needed is an in-depth understanding of the issue, that is usually the aim of qualitative studies. In-depth understanding is based on researcher immersion in the issue, collecting data from various sources and interacting with people in order to provide depth and details (Patton, 1980). Qualitative research, and case study in particular, is the preferred method when the research question is a “how” question. For these reasons, I decided to use a qualitative case study as methodology in order to answer to my research question. Moreover, case study is a typical explanatory, theory-building research and is especially appropriate when the focus of the study is a contemporary phenomenon and when multiple sources of evidence are used (Carson et al., 2001; Yin, 2008).

Case analysis is a kind of research methodology that usually tends to address research problems within an ontological interpretivist paradigm. Ontology is defined as reality, epistemology as the relationship

20 between that reality and the researcher and methodology is the technique used by researcher to discover that reality (Perry et al., 1999). Literature traditionally identifies two opposite ontologies: positivism and interpretivism. My work clearly adopts the latter paradigm: it is out of its the scope to investigate the long-standing debate between these two philosophies of research, so I will just touch upon the issue in order to contextualize my research methodology.

Positivist ontology considers the world as external and objective, therefore the researcher must maintain a distance from the objective of research and try to explain causal relationship by means of objective facts. Researchers of this school usually use statistics and mathematical techniques for processing quantitative data in order to prove theories. On the other side, according to Carson et al. (2001), “the interpretivist approach allows the focus of research to be on understanding what is happening in a given context. It includes consideration of multiple realities, different actors’ perspectives, researcher involvement (…). Instead of trying to explain causal relationships by means of objective facts and statistical analysis, interpretivism uses a more personal process in order to understand reality”.

According to the authors, the choice of a positivist or an interpretivist approach have different methodological implications on several aspects:

1) Role of prior theory: positivist researchers use prior theory in order to arrive at hypotheses or research questions at the early stage of the research, while interpretivist ones use it in various stages;

2) Theory building vs testing: theory testing is typical of positivist research, while interpretivist research focuses on generating theories, the so called “theory building”;

3) Deduction vs induction: deduction entails the development of a conceptual and theoretical structure prior to its testing through empirical research methods, while induction is allowing the data to guide the research and theory building. The first type of studies are usually positivist, while the latters are interpretivist;

21 4) Structured vs unstructured research: positivist research usually are structured one, where research is a logical, sequential, step-by-step process following a clear plan and protocol, while interpretivist research can also be rather unstructured, allowing changes while developing;

5) Role of the researcher: positivist researchers believe that researcher should remain distanced from the material being researched, while at the opposite interpretivists believe that the researcher has a fundamental role in the research progress and progression, as “the human instrument” of the research (Hammersley & Atkinson, 1983).

My research aim clearly fits into the interpretivist paradigm. The case I selected is the one of Banca Etica. Banca Etica is the first institution of ethical finance in Italy, created by a group of Italian associations, NGOs, social cooperatives, trade unions, religious entities and by thousands of individuals in 1999. It has a share capital of roughly €63,7M with 41.000 shareholders (of which 6.500 enterprises), €1.314M of savings collection and €1.026M loans approved (figures as of 30/06/17). It is therefore one of the biggest and oldest social banks in Europe and also an active member and founder of all the existing social banking networks, Febea, the GABV and the Institute for Social Banking. I decided to focus on this bank because of my personal relation with it. Indeed, I have been working at Banca Etica during all the research period. Thanks to my role in the organization, I have been able to access to a valuable amount of information otherwise impossible to collect. This is exactly the case when, according to Yin (2008), it is valuable to focus the research investigation only on one specific case. In fact, in the words of the author “having only one case is justified if it meets at least one of these three criteria: (…) the case provides unusual access for academic research, and unless the case is investigated, an opportunity to examine a significant social science problem may be lost”. During the research period, I have been a credit analyst at the headquarter loan office. I have also been involved in a working group with the goal of proposing an impact measurement framework. The combination of these roles has given me the possibility to have an in depth and evolving understanding of the subject plus direct access to data, to managers and to the bank staff and members. In addition, I have also had the possibility to participate to meetings with representatives of the other European social banks, being able to share and ask for advice in an international context.

22

Methodology description

One of the most popular criticism of using case studies in research is that they can result in massive, unreadable documents (Feagin et al., 1991). It is thus fundamental to follow a rigorous methodological path (Yin, 2008). I decided to follow an interpretive approach proposed by Carson et al. (2001). This approach is one of the most popular in the literature about case analysis. The following lines describe it and explain why I decided to adopt it.

Case analysis can be used for both theory building (induction) and theory testing (deduction). These two elements can also be combined in the same case. This issue has been debated by the literature for a long time. Carson et al. (2001) propose a general model with both induction and some very limited deduction. After an initial part of theory building, they propose a confirmatory/disconfirmatory stage which is distinguished from a clearly theory testing stage which is left to later researchers. The research starts with some convergent interviews with practitioners, while the prior theory from the literature is being reviewed (Nair & Riege, 1995). Secondly, one or two pilot studies are carried in order to fine-tune the interview protocol, before the main data collection. In other words, prior theory is developed from the literature review and from the pilot studies and/or convergent interviews. It is then used to develop the questions for an interview protocol which is used for the main data collection.

The authors propose also a more inductive variation of their general model which, according to their opinion, is more suitable for single case study. The most significant modification occurs at the end of the first stage: the research does not enter into the confirmatory/disconfirmatory stage, but keep on developing theory. Instead of confirming/disconfirming a number of similar issues with different companies, the interviews focus on a more in-depth evaluation of the findings emerged from the first stage; this evaluation can also be carried for instance with follow-up interviews after a certain period of time. This approach is particularly valuable for more in-depth focus to theory building, so I decided to adopt it.

23 I therefore structured my research in the following way. I started with an extensive literature review on the issue of impact measurement in social banking. I combined it with some preliminary convergent interviews to managers of Banca Etica and with an analysis on the loan portfolio of the bank. During this step, I participated to an international summer school organized by the Institute for Social Banking where I had the chance to carry other convergent interviews with managers from other European social banks. The combination of literature review, loan analysis and convergent interviews was fundamental for orientating the research. I was able to identify the three main components of an impact measurement system for social banking: a set of impact areas, a corresponding set of indicators and a system of data aggregation. Through the loan analysis, I could identify the main impact areas of the Banca Etica credit portfolio and compare them to the ones identified by the literature. Convergent interviews helped me to understand the main issues to explore during my research and the fundamental features to include in the measurement methodology.

Thanks to the findings of the initial steps, I built an initial measurement methodology that I included in an interview protocol. I carried nineteen structured interviews, some of them follow-up ones, to managers and staff members of Banca Etica, social entrepreneurs customers of the bank and academics. Their answers allowed me to solve the issues identified in the initial steps and to refine my methodology. I was then able to propose a final methodology with an identified set of impact areas and corresponding indicators and a system of data aggregation with all the features identified during the research.

After the theory building phase, I decided to carry also some initial theory testing activities. In particular, I applied my methodology to the loan portfolio of Banca Etica, in order to test the consistency of the system of data aggregation to a real case. Conversely, the set impact areas and the corresponding indicators were tested through a survey. The people who participated to the survey were members and employers of Banca Etica involved in the lending process, plus the members of the Board of Directors of Banca Etica. The whole research process lasted two years and a half, starting in January 2015 and ending in July 2017. Each step of the research is described in the next chapters, with additional details about goals and results.

24

CHAPTER 3: LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter is dedicated to the literature review. It initially presents a brief overview of the general literature about impact measurement. Secondly, it focuses on the literature regarding impact measurement methodologies. It then concentrates on the review of the existing literature and methodologies of impact measurement for social banking. It finally states my conclusions regarding the whole literature review.

Impact measurement in general

As discussed in the previous section, literature review is also a part of the research process in itself for case analysis. In light of this consideration, I analyzed the literature constantly referring to the findings I was making during my exploration of the case, following an iterative process. I initially focused on the specific literature about impact measurement in social banking, a literature that turned out to be rather limited and at an initial stage. I therefore broadened the scope of the review to the general debate about impact measurement, trying to identify the elements that could be useful for the specific case of social banking. I start my review from this point.

Literature about impact measurement is vast and extremely various. This is basically due to the fact that the concept of impact can be measured in a variety of ways, from a variety of perspectives and to be accountable to several different stakeholders (Grieco et al., 2014). Basing on these drivers, I identified the different streams of the literature on the subject in order to concentrate to the ones more relevant for my research. A significant stream concentrates on defining the concept (Emerson et al., 2000; Latanè, 1981; Maas & Liket, 2011; Nicholls J. , 2007) and, as anticipated in the introduction, it is not still possible to identify a unique definition of impact. It is otherwise possible to state that a common agreement has been achieved on the Impact Value Chain framework (Clark et al., 2004) that has been adopted also by the EU Standard for Social Impact (GECES Sub-Group on Impact Measurement, 2014), the European Venture Philanthropy Association’s (EVPA, 2013) and the G8 Social Impact Investment Taskforce (G8 Social Impact Investment Taskforce, 2014).

25 Another significant part of the literature focuses on why organizations should measure their impact and the advantages deriving from doing it (Austin et al., 2006; Boyd et al., 2009). In the previous section I specified why this is an important issue also for social banks. There are also several works in the field of the evaluation of organizational performance that are interested in integrating impact indicators into their framework (Alexander et al., 2010; Mitchell, 2013). A vast part of the literature about impact measurement is dedicated to analyze and design the process of impact measurement, focusing on its different possible phases. According to Zamagni et al. (2015), there are two fundamental models that are used by social enterprises to measure impact and can summarize this stream of literature: the one proposed by the G8 Social Impact Investment Task Force derived from Inspiring Impact (2013) and the one utilized by GECES derived from the EVPA (2013). The first process is divided into 4 phases: 1) Planning of the wanted impact and the way to achieve it; 2) Realization of the impact; 3) Evaluation of the obtained impact, 4) Review of the results and identification of the improvement areas. The second process is instead structured in 5 parts: 1) Definition of the goals; 2) Analysis of the stakeholders; 3) Measurement of the results; 4) Evaluation of the impact; 5) Monitoring and improvement. The last, and most interesting stream of the literature for the purpose of this work, focuses on impact measurement methodologies.

Literature about impact measurement methodologies

Literature about the measurement process discusses how to design, structure and implement the different phases of measurement. In other words, it analyzes the way to put impact measurement into practice. This literature though does not provide methods or indicators to measure impact, which is instead the goal of the current work. This issue is at the heart of the most extended part of the literature about impact measurement. I will review this literature by highlighting its usefulness to the case of social banking. Given the vast multiplicity of available impact measurement methodologies, recent literature has focused on reviewing and clustering these approaches. Zamagni et al. (2015) provide a collection of the principal reviews on the subject. Nicholls (2015) divides the existing approaches in 3 categories:

26 1. Approaches based on outputs: They do not focus on the outcomes of the activity, but on the

context in which they take place;

2. Approaches based on intended and positive outcomes: They do not consider the unintended outcomes and if the positive outcomes would have occurred in any case;

3. Holistic approaches: They are able to establish the causality link between activities and outcomes and they consider the involvement of stakeholders in the measurement process. These are of course the most complete approaches.

Another classification is provided by Grieco et al. (2014). They conducted an investigation on 76 impact measurement methods at international level, identifying four typologies of methods:

1. Simple Social Quantitative: They provide quantitative indicators of the social impact and of the impact on employees in a retrospective fashion, applicable to different sectors;

2. Holistic Complex: These models combine qualitative and quantitative indicators with the purpose of verifying the achievement of goals and to report to stakeholders;

3. Qualitative Screening: Mainly adopted by organizations operating in education and employment sectors, these methods are simple and collect qualitative data;

4. Management: They use both qualitative and quantitative variables, trying to measure different types of impact and are used for management or certification goals. They are generic and have the aim to help organizations to reduce their negative impact and to increase the positive one.

It is not possible to place a possible method for social banks in one of these categories because it must comprehends both stakeholder accounting and management purposes. Another significant review is that of Bengo et al. (2015) that identify three categories of measurement methods:

1. Methods that, starting from different kind of impact, provide an unique synthetic indicator;

2. Models that focus on the process of the activities of an organization, following the impact value chain;

27 3. Methods that have as final outputs dashboards and performance indicators with the aim of

providing information on the different fields of organization performance.

The final output of a method for social banks can be a sort of dashboard. However, it is still necessary to take into account the theory of change of these institutions. It is not therefore possible to allocate a methodology for social banking in a unique category among the ones proposed. Another taxonomy of impact measurement methods is proposed by Perrini & Vurro (2013) and it is composed by 6 categories:

1. Experimental Methods: This is the typical approach used by international organizations for evaluating on field development projects (Banerjee et al., 2007). The typical methodology is randomized controlled trial. There are several advantages of this methodology (e.g. replicability, isolation of significant variables), but it is extremely costly and time consuming and also not applicable to measure impact of an entire organization. It is not therefore suitable for social banking;

2. Logic Methods: These methods try to evaluate the impact of a project by following the logic chain from the mission and the goals, through activities arriving to the final outputs of the project. It is a sort of storytelling in which qualitative and quantitative indicators are integrated. Again, the focus on projects does not allow the use of such methods for social banks;

3. Strategic Approaches: These are usually classified among measurement models even if they are more methods for the management of operative processes. The typical examples are the strategic maps and the balance scorecard (Kaplan & Norton, 1996). Even though these methods can successfully involve the different stakeholders of an organization, they are not useful for representing and reporting impact;

4. Participatory Methods: Based on the involvement of stakeholders, the methodology of evaluation is built according to the relevance of the different typologies of impact for them. It is also useful to design the activities itself, but its aim is not to reporting;

28 5. Integrative Methods: These methods use complex methodologies, like the system thinking, in order to control all the factors concurring to determine the efficacy of development programs (Ramalingan et al., 2008);

6. Expected Return based Methods: These methods aim to quantify the social benefits connected to the attainment of certain goals in one context or to certain beneficiaries. They compare benefitts to the monetary cost beard to carry the activities. This is the most diffused typology of methods: some examples are the Best Available Charitable Option (BACO), the Social Return of Investment (SROI), the Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) and the Cost Efficacy Analysis (CEA). Unfortunately, neither these methods are useful for social banks because they all refer to single project evaluation and monetize the impact (Scholten et al., 2006).

In order to complete this review of methodologies, it is necessary to cite a couple of reporting standards. They are not proper impact measurement methodologies, but have some common features. The first reporting standard is the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). This methodology provides the guidelines for the reporting system of sustainable organizations. It concentrates on four areas: financial, environment, social and impact. Even if it does not provide a unique measurement of impact, it is a fundamental standard at international level for sustainability reporting. Another important reporting standard is the IRIS (Impact Reporting and Investment Standards), developed by the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN). It consists in a list of indicators useful for the measurement of social, environmental and economic impact. The aim of this system is to develop a reporting structure that can make possible to compare different organizations. Using IRIS data, the Global Impact Investing Rating (GIIRS) explores different kind of impact according to different sectors. Its aim is to provide a final evaluation of an organization expressed as a rating. These reports and methodologies provide interesting insights for social banks, especially in providing possible indicators, but they are not able to address the needs of a complete measurement system for them.

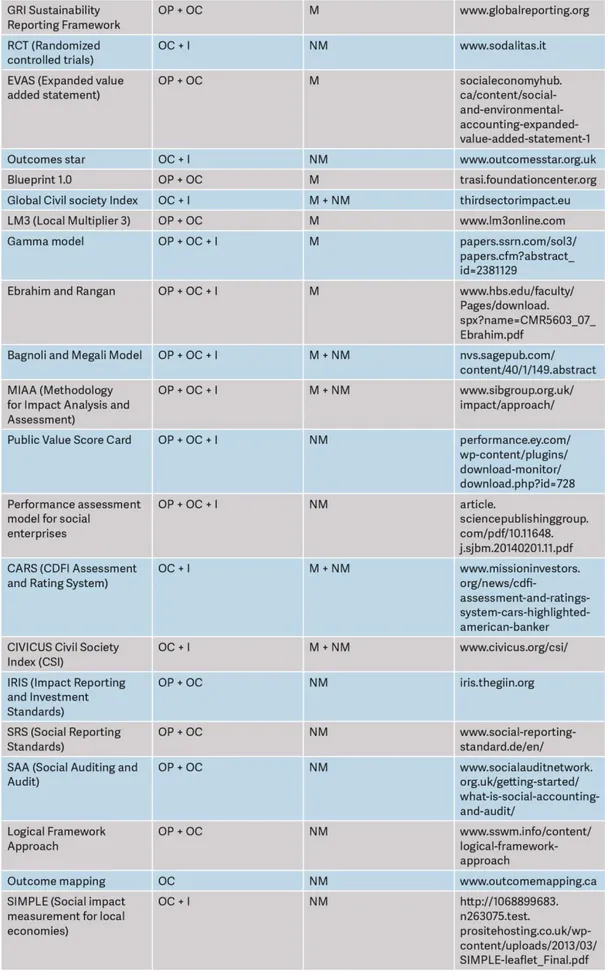

In the picture in the next page, it is possible to find a list of the most important impact measurement methods from Zamagni et al. (2015). They are classified according to the point of the impact chain they

30

31 measure and if the output is a monetary one or not. This provides a comprehensive picture of the existing methodologies and concludes this review.

Impact measurement methodologies for social banking

To the best of my knowledge, specific literature about impact measurement for social banking is truly limited. The same can be said about impact measurement methodologies: some social banks measure their impact, but there is not a common standard available. In the next lines, I review the existing literature and methodologies with the purpose of identifying the corresponding limitations.

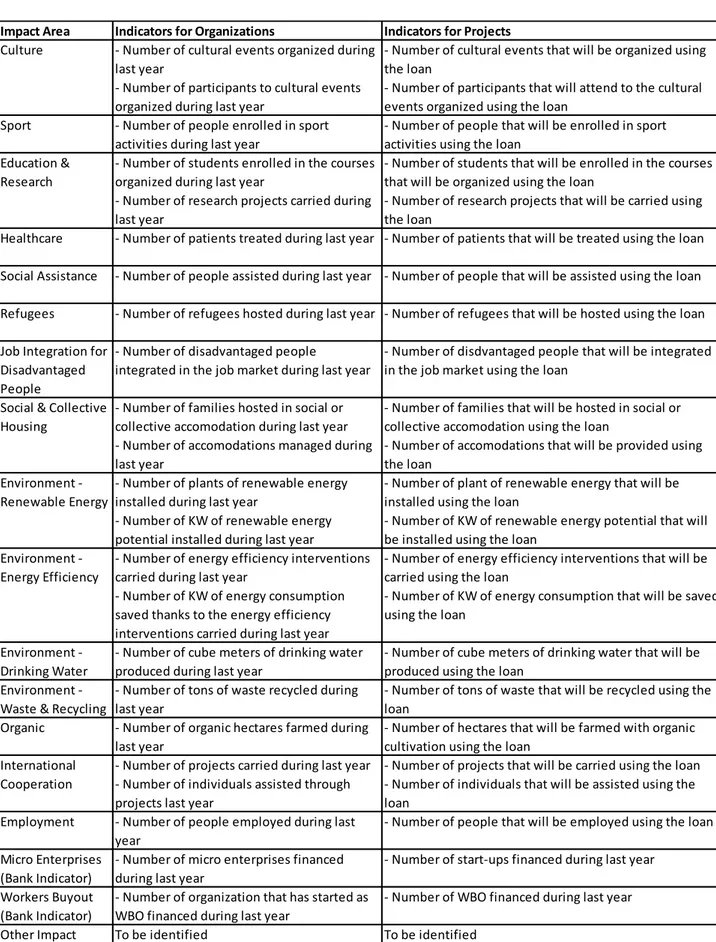

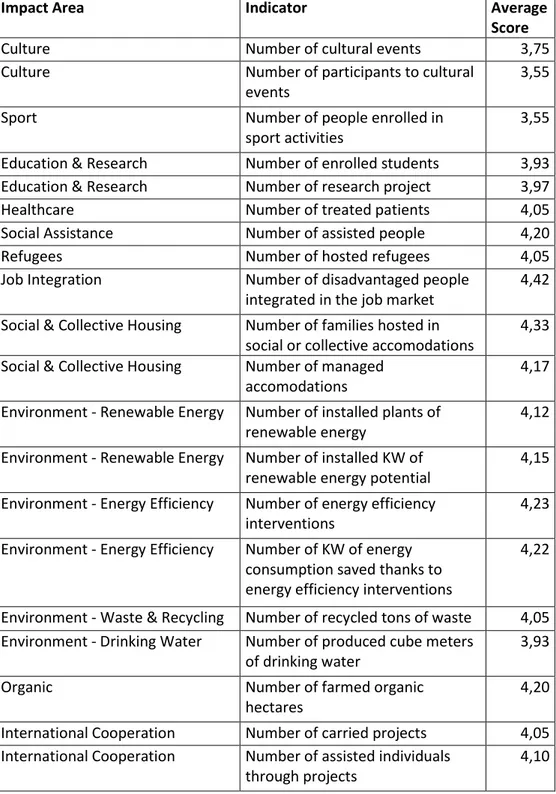

The most recent and significant work on the issue of impact measurement for social banking is the one written by Altis (2015) in partnership with Febea and the Institute for Social Banking. It is a review of the existing impact assessment methodologies for social banks based on a literature review of more than 3.000 articles. The authors review the most commonly used impact measurement methods (SROI, IRIS and GIIRS) explaining why they are not suitable for social banking. They identify storytelling as a method widely used by social banks: this method, even if connects emotionally depositors to the financed projects, does not provide a comprehensive picture of the impact of a social bank. They also list some attempts of measuring impact made by practitioners, but they conclude that “so far, no rigorous method for measuring the social impact of an ethical bank’s total activities has been developed”. The work main contribution is a list of impact areas of the lending activity of social banks (Arts and Culture, Environment, Training and Job Creation, Social and Health Care, Microcredit and Social Housing, Sustainable Agriculture) and of corresponding possible indicators. The shortcoming recognized by the authors is that it does not indicate which are the most significant indicators. More importantly, it does not propose an organized methodological framework: it does not tackle the issue of distinguishing between outcome and impact, not taking into account deadweight and attribution concerns.

Another significant work, carried in partnership with the Institute for Social Banking, is the one of Bosheim (2012). The author analyzes two case studies of impact measuring in social banks: Charity Bank in the UK

32 and Triodos Bank in the Netherland (the latter is the biggest social bank in Europe in terms of total assets). Charity Bank evaluates each single loan project on 4 basis: Mission Focus (if the project has a clear mission), Organization Resources, Financial Resources and Wider Impact (on community, staff and environment). The blue area in the figure is the project impact.

Figure 3: Example of impact measurement of Charity Bank (from Bosheim, 2012)

The main shortcoming of this method is that it is only at a project level. It is not therefore possible to report data at an aggregate level for stakeholders. Moreover, it is not clear how the four dimensions have been selected and how the value of the indicators are estimated. Triodos Bank is able to provide the total amount of the money lent to eight sectors (Renewable Energy, Organic Farming, Sustainable Property, Arts and Culture, Education, Social Housing, Healthcare and Microfinance) in a specific year and a corresponding indicator of impact. This is a rather structured approach, but indicators mainly refer to the impact generated by the financed organization as a whole. It is not able to isolate the impact referring to the loans provided by the bank: again, deadweight and attribution issues are not taken into account. Moreover, the impact refer to loans approved in a specific year, the bank does not provide data about the whole loan portfolio.

33

Figure 4: Example of impact measurement of Triodos Bank (from Triodos Bank annual report 2016)

Another contribution worth mentioning is the one of Ballesteros & Herden (2013). It is a case study about a Spanish social bank, Fiare, which is nowadays merged with Banca Etica. The two authors apply two methods to this case: the SROI and the RAI (Radical Affinity Index), an index developed by San-Jose et al. (2011). The RAI is essentially a method to classify banks according to their position on ethical commitment. It considers four features: the placement of assets, guarantees, transparency and participation. Therefore, the aim of the RAI is to distinguish among traditional and social banks; it cannot be strictly classified as an impact measurement method. A similar tool is the Scorecard proposed by the GABV (2017). The last contribution on the issue is a research on the first 15 years of activity of Banca Etica conducted by Altis (2014). This work provides some quantitative indicators on a sample of loans of Banca Etica and some qualitative indicators measuring customer satisfaction.

Finally, it is necessary to mention the tool developed by the Global Alliance for banking on values (GABV): the GABV scorecard. It is not exactly an impact measurement tool in the sense of the current work, but it is close to that and it is popular among social banks all over the world. It is designed as the world’s first banking solution for qualitatively and quantitatively measuring the economic, social and environmental

34 impact of banks, with a focus on those that operate according to the Principles of Sustainable Banking. By applying the scorecard, it is basically possible to determine if a bank is a sustainable one, according of course to the GABV principles. It is not used, therefore, to measure the impact of the lending activity of a social bank.

Literature review conclusions

The main conclusion of the literature review is that, at this time, a universally recognized method for measuring impact for social banks does not exist. The most rigorous and widely used existing methods for measuring impact are not suitable for the social banking case. The literature on the issue has so far proposed a list of impact areas and a list of corresponding possible indicators. Practitioners’ methods have some significant limitations: they do not clearly link the impact to a loan provided by a bank, do not take into account the issues of deadweight and attribution and do not provide a comprehensive impact picture of a bank loan portfolio.

35

CHAPTER 4: CONVERGENT INTERVIEWS AND LOAN PORTFOLIO ANALYSIS

This chapter describes the first steps of my case analysis: convergent interviews and the loan portfolio analysis of Banca Etica. It starts by explaining the reasons why I decided to carry these activities. It later illustrates their results that constitute the basis for the following in-depth interviews. These activities took place from January 2015 and August 2015 with the literature review.

Convergent interviews and loan portfolio analysis’ goals

While I was reviewing the literature, I also carried an analysis of the loan portfolio of Banca Etica and a series of convergent interviews to its managers and to managers of other European social banks. This was in line with the research methodology previously explained. The main aim of the loan portfolio analysis was to have a general understanding of the impact areas of investment of the bank. Impact areas correspond to social and environmental needs that the financed organizations of a social bank try to address. In order to be able to report impact for the whole loan portfolio of a social bank, it is then necessary to identify the categories of impact to which the loans refer. These areas of impact must be sufficiently significant in terms of volume compared to the total loan portfolio of the bank. A loan portfolio of a social bank can include hundreds of different impact areas: trying to report indicators for each single area would result in an unreadable and not significant amount of information. This is why it is necessary to identify the most significant impact areas in terms of volume. As explained in the correspondent section, literature has identified some of these impact areas. Another goal of my analysis was to verify their correspondence to the Banca Etica loan portfolio.

According to Dick (1990), convergent interviewing is a cyclic series of in-depth interviews with expert that allow the researcher to refine the questions after each interview. The goal is to converge on the issues in a topic area: it is a series of “successive approximations”. Convergent interviews are almost completely unstructured and are particularly useful in qualitative research about a topic area which has no established theoretical base. This is the case of impact measurement for social banking. In my case, convergent

36 interviews had a multiplicity of goals. The most important one was to identify the fundamental features that an impact measurement system for a social bank must have in order to be significant and reliable, according to experts in the sector. Secondly, interviews were useful for identifying the main problems and issues that needed to be overcome in order to build the methodology. The final goal was to guide the loan portfolio investigation, through insights of experts, and to start thinking about possible corresponding indicators.

Convergent interviews

Dick (1990) suggests interviewing a small and heterogeneous group of people for convergent interviews. The goal is not to gather representative information, but relevant one. For this reason I decided to interview seven people, five from Banca Etica and two from other European social banks. The five people from Banca Etica were: the General Manager, the Credit Manager, the CSR Manager, the Strategy Manager and a branch manager. The two people from European social banks were former General Managers of a German and British bank. The interviewees significantly differed in terms of age, role, origin and degree of involvement with the final customer. Their heterogeneity gave useful insights from very different perspectives, resulting in a significant framework of opinions. General and strategy managers tended to focus on managerial implications of the impact measurement system. They considered it a strategic tool in order to constantly verify the adherence to the bank mission. They also underlined the importance of having a credible and easily understandable representation of impact for accountability reasons. The CSR manager focused on identifying specific impact areas and on providing corresponding indicators. The credit manager considered impact measurement as a valuable tool for loan portfolio planning, underlying its implications with credit risk control. Finally, the branch manager were particularly valuable in identifying impact areas and possible indicators, given its proximity to the final customers.

I now report the main common findings of the convergent interviews. Interviewees suggest the following features that an impact measurement system should have or take into account.