Academic Year

2018/2019 Joint Ph.D. Course Political Science, European Politics and International RelationsCulture, Diplomacy, and Power: The French and British

Models of Cultural Diplomacy in the Early Twenty-First

Century

Author

Alessandro Giovanni Lamonica

Supervisor

To my Uncle and Mentor, Dr. Paolo Carrara, who taught me that Life is about practicing Composure, Perseverance, and Moral Consistency.

Table of contents

List of Figures and Tables 9

Abstract 11 Preface 12 Acknowledgments 13 Glossary 14 Chapter 1. Introduction 16 1.1 General objective 16

1.2 Structure of the thesis 17

1.3 Research framework 19 Research question 20 1.4 Methodology 20 Case selection 20 Data collection 26 Data analysis 30

Section One. Review and Theoretical Framework 37

Chapter 2. A review 37

2.1 Culture, Diplomacy, and Power 38

2.1.1 Culture 38

Culture in Anthropology 41

Culture in Cultural Diplomacy 46

2.1.2 Diplomacy 47

2.1.3 Power 50

The second face of power 51

The third face of power 52

Power analysis 54

The future of Power 61

Soft Power 62

2.2 What is cultural diplomacy? 66

2.2.1 The “Public diplomacy” approach 67

2.2.2 The “Cultural relations” approach 73

Chapter 3. A new theoretical framework for cultural diplomacy. Categorical and analytical implications

77

3.1 What is happening to diplomacy? 77

3.2 The state of play of cultural diplomacy. Hints from the review

78 3.3 A radial categorization and original definition of cultural diplomacy 80

3.4 An analytical model for cultural diplomacy 84

Section Two. Case studies 90

Chapter 4. History and models of cultural diplomacy 91

Introduction 91

Historical evolution of cultural diplomacy 91

Cultural nationalism: 1870-1914 91

Cultural propaganda: 1914-1945 93

Cultural diplomacy: 1945-1989 94

The democratization of the practice of cultural diplomacy: 1989 onwards 96

Centralized and decentralized approaches 97

4.1.1 History and evolution of French cultural diplomacy (1883 – 2009) 99 The Nineteenth Century: The first steps of French international cultural relations

99

Shaping the roots of French cultural diplomacy: 1914-1945 102 French cultural diplomacy at its finest: 1945 onwards 105 The Directorate-General for Cultural Relations 106 The late 1950s: decolonisation, expansion, and reconversion 107 From 1970s to the 1990s: Science, mutuality, and new Media 108 4.1.2 The current model of French cultural diplomacy (2009 - 2017) 112

Politics and Foreign Cultural Policies. Mr Sarkozy and Mr Kouchner “à la guerre”

112

The long road to a new French cultural diplomacy 113 The current model of French cultural diplomacy 118

A complex organizational structure 119

The role of Ministries 119

The role of state operators 122

4.2 United Kingdom. The Arm’s Length Approach 126

4.2.1 History and evolution of British cultural diplomacy (1934 – 2011) 127 1939-1945. Between cultural propaganda and multilateral cooperation 128 The post-war period: Advance, retreat, and developing role 130 Early 1990s. The era of new public management: The reorganization of the British Council

132

2000-2010: Arm’s Length relationship and public diplomacy 136 4.2.2 The current model of British cultural diplomacy (2011-2017) 140

Free but under surveillance 141

Public management and executive non-departmental public bodies: A story of love and hate

142

The United Kingdom’s government strategic approach to cultural diplomacy

145

A framework for action: public management and strategic governance 149

The British Council 150

4.3. The British and French models of cultural diplomacy. A few notes 159

4.3.1 France 159

4.3.2 The United Kingdom 160

Chapter 5. PiC in practice 164

5.1 The protection of cultural heritage in conflict areas 167

Introduction 167

The destruction and looting of cultural heritage: A real threat? 168

The securitization of cultural heritage 170

Traditional and unconventional securitizing practices 172 5.1.1 The United Kingdom and the protection of cultural heritage. The case

of the Cultural Protection Fund Programme

175

Traditional multilateral cooperation 176

Unconventional initiatives: The case of the Cultural Protection Fund 179 The United Kingdom’s security strategy and the role of official development assistance

180

Culture and Development 182

The Cultural Protection Fund 183

5.1.2 France and the protection of cultural heritage. The case of the Aliph Foundation

190

Traditional bilateral and multilateral cooperation 191

Mali. A dress rehearsal 192

Hollande and the institutional narrative of cultural heritage protection 195 French engagement in traditional multilateral activism 196

Unconventional initiatives 198 Safe Havens. A controversial network of shelters 199 The International Alliance for the Protection of Cultural Heritage in

Conflict Areas – Aliph

200

Is Aliph an unconventional and innovative security measure? 204

5.2 Culture and the promotion of intercultural dialogue for peaceful inter/intra-community relations

206

The “Arab Spring”: An (Un)-welcome surprise? 207

Multilateral responses to the Arab Spring 209

The United Nations 209

The European Union 209

The G8 and the Deauville Partnership with Arab Countries in Transition 210 5.2.1 The United Kingdom’s Young Arab Voices Programme 213

British Foreign Policy and the Arab Spring 213

The British Council and the support to Arab Countries in transition 216

The Young Arab Voices Programme 218

The launch of the Young Mediterranean Voices Programme 220

5.2.2 France and the SafirLab programme 224

French foreign policy and the Arab Spring 224

The SafirLab programme 230

Chapter 6. Conclusions 237

Introduction 237

6.1 A brief overview 237

6.2 Changing practices and new contexts 239

Practices of cultural diplomacy for the protection of cultural heritage 240 Practices of cultural diplomacy for intercultural dialogue and civil society

building

6.3 Assessing the power of the radial categorization and the analytical model against practice

244

6.4 Further research suggestions 253

6.5 Limitations of the study 257

Bibliography 259

Workings in appendices

Appendix 1: Case study database - interviews 286

Appendix 2: Informed Consent Form 289

List of Figures and Tables

Figures

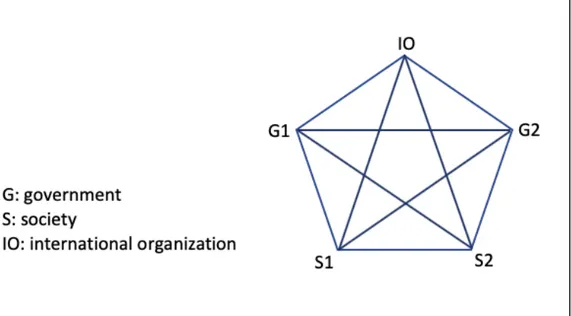

Figure 1. Schematic research framework 19

Figure 2. Multiple-cases design with embedded units. State-driven Cultural Diplomacy: The cases of France and the United Kingdom

20

Figure 3. The levels of Culture. Source: Spencer-Oatey (2012:4), adaptation of Schein (1984:4)

44

Figure 4. "Star model" of public diplomacy. Adaptation of J. Nye, 2011:102 65 Figure 5. A radial categorization of cultural diplomacy 82 Figure 6. Graphic representation of the analytical model of Cultural Diplomacy 88 Figure 7. Directorate-General for Global Affairs, Culture, Education and

International Development: Organizational chart. Source: French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2019

120

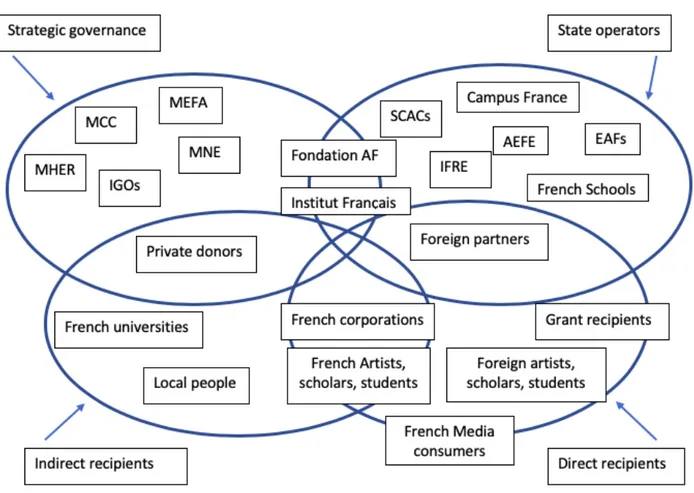

Figure 8. French cultural network abroad- Source: Cour des comptes, 2013: 157 121 Figure 9. Visual sociogram: French external cultural action. Adaptation from Cour

des comptes, 2013:156

126

Figure 10. Visual sociogram: Young Mediterranean Voices, Governance and Management

223

Figure 11. Cultural diplomacy. Radial categorization before empirical analysis 245 Figure 12. Cultural diplomacy. Radial categorization revised 245 Figure 13. Graphic representation of the analytical PoC-PiC model of Cultural

Diplomacy

249

Figure 14. Hybrid power and Smart Cultural Diplomacy 253

Tables

Table 1. Case selection 26

Table 2. Themes of definition for culture. Adaptation of Baldwin et al. 2006:30 41 Table 3. Three aspects of relational power. Source: Nye, 2011:14 54 Table 4. Three faces of power behaviour. Source: J. Nye, 2011: 91 63

Table 5. Power: Typology, Behaviours, and Resources. Adaptation of J. Nye, 2004:8

64

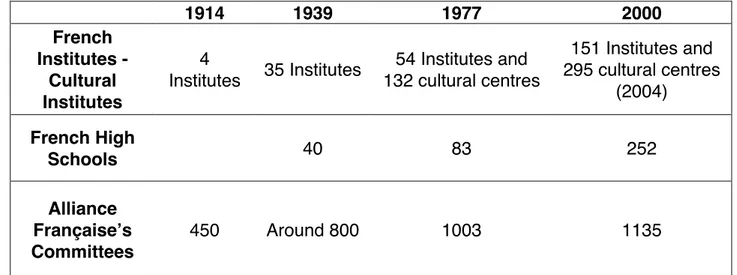

Table 6. Taxonomy of public diplomacy. Source: N. Cull, 2008:35 71 Table 7. The PoC-PiC analytical model of Cultural diplomacy 87 Table 8. French cultural network abroad. 1914-2000. Source: Chaubet & Martin,

2011:132

110

Table 9. History of French cultural diplomacy. Milestones. 111 Table 10. The British Council's priorities and initiatives. Adaptation form British

Council, Corporate Plan 2017-2020, 2017:5

155

Table 11. Spending Review 2016-2020: income projections. Source: British Council Corporate Plan 2017-2020, 2017: 39

157

Table 12. UNESCO Conventions: The ratification status of France and the United Kingdom. Source: UNESCO

174

Table 13. Cultural Protection Fund: Project activities. Source: British Council, 2016:5

186

Table 14. Arab Partnership Participation Fund: British Council's Projects. Source: Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Arab Partnership, Fiscal Years 2011-2015

218

Table 15. Culture, Diplomacy, and Power. A circular relationship 237 Table 16. Power behaviour and power bases according to the PoC-PiC analytical

model of Cultural diplomacy

248

Charts

Chart 1. Cultural Protection Fund: Eligible countries, updated at October 2018. Source: Pugh and Bishop, 2018

184

Chart 2. Cultural Protection Fund: Projects by location, updated at October 2018. Source: Pugh and Bishop, 2018

Abstract

The objective of this thesis is to offer a new conceptualization of contemporary cultural diplomacy that builds off of the emergent triadic interaction between a resource -culture-, an instrument -diplomacy-, and a relation -power. It also develops an analytical model of state-driven cultural diplomacy and it tests it on the initiatives undertaken by the United Kingdom (UK) and France in the framework of their strategy towards partner countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) in the aftermath of the so-called “Arab Spring”. Overall, the thesis has the ambition to bring a new theoretical perspective to the study of cultural diplomacy and to assess the role of cultural diplomacy in contemporary foreign policy and its place in the practice of power in international relations.

Preface

The reason for the author’s interest in cultural diplomacy traces back to his previous involvement in research in the field. Indeed, between February and November 2016, he was field researcher for the project "Cultural Diplomacy as Discipline and Practice. Concepts, Trainings, and Skills" (P. Isernia and A. G. Lamonica, 2016). The report was commissioned by the European Union Network of Institutes for Culture (EUNIC). It surveyed existing cultural diplomacy training and research activities and it tried to assess the training needs of the cultural diplomat of the future, as seen from practitioners and academics. That first piece of research showed that the current context is characterized by a complex view of cultural diplomacy, a practice based on a long-term approach that involves many independent stakeholders at different levels of engagement. There is no shared understanding of what cultural diplomacy is, how it works, who practices it.

This research builds off of these issues. First, the gap observed between current practices and scientific literature on cultural diplomacy turns into significant conceptual uncertainty and calls for further studies, for little has been done so far to offer a clear conceptualization of cultural diplomacy as a first step toward the development of an explanatory framework for its functioning. This absence of clear, robust theoretical schemes and the fact that empirical research is still at an early stage make it difficult to assess the role of cultural diplomacy in contemporary foreign policy. Second, this need is also justified by the new dynamism that is shaping the field at the national and supranational levels, in Europe first. Indeed, to a certain extent the lack of reliable findings is partially justified by the fact that this is a contemporary and evolving research problem.

Acknowledgments

In the first place, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Pierangelo Isernia for his tireless support and especially for getting me involved in his research activities from the very beginning of this journey. With his demanding nature he allowed me to take the first steps in the complex world of the academy and he helped to deepen my understanding of the field.

My sincere thanks also goes to Prof. Jo Beall and Emily Morrison, who offered me a unique opportunity to join the Education and Society team at the British Council and to conduct field research in London and in the network abroad. I am grateful to Dr. Anna-Louise Milne for having hosted me at the University of London Institute in Paris during my fieldwork in the French capital and to Dr. Serena Giusti for her insightful comments and encouragement.

Particular thanks to Andrew Murray and Lina Kirjazovaite at EUNIC Global. Our joint initiatives in the field of EU’s cultural diplomacy have provided me a precious opportunity to meet a number of distinguished practitioners and academics, whose feedback and ideas have greatly refined my understanding of the role of culture in diplomacy.

I would like to thank the interviewees who participated in this research and the library staff at the European University Institute in Florence and at the University of London Institute in Paris for their efficient and helpful service.

On a personal note, I especially owe thanks to my mother Giuseppina and my brother Andrea. They have always assured me of their support and love for years. This research would not have been possible without their encouragement to embark on this adventure. I would also like to thank my aunt Marialuisa and my uncle Paolo, who have been my spiritual mentors.

Glossary

This glossary includes individuals, organisations and government departments referred to in the thesis.

Anna Lindh Foundation The Anna Lindh Euro-Mediterranean Foundation for the Dialogue between Cultures has been established in 2005 in the framework of the Barcelona Process. The Foundation promotes intercultural dialogue through intellectual, cultural and civil society exchanges

Assemblée nationale The National Assembly (Assemblée nationale) is the lower House of the French Parliament. The upper House is the Senate (Sénat)

Cabinet Office The Cabinet Office is a British ministerial department that supports the Prime Minister. It is entrusted with the responsibility to ensure the running of Government

Cameron, David Conservative politician and former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, 2010-2016

Commission National Consultative des Droits de l’Homme (CNCDH)

The National Consultative Commission on Human Rights is a French governmental organization operating under the purview of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It supervises the respect of human rights in France

Cour des comptes The Court of Auditors is an administrative court that is entrusted with the financial supervision of French public institutions

De Gaulle, Charles French war hero and statesman, former President, 1959-1969

Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS)

The DCMS is a British ministerial department in charge of supporting culture, media and sport Federal Council The Federal Council is the highest Swiss executive

authority. It consists of seven members, each leading a government department

Fillon, François Conservative politician, former Prime Minister of France, 2007-2012

Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO)

The FCO is a British ministerial department in charge of promoting the country’s interests abroad

Her Majesty the Government (HMT)

Formal term referring to the government of the United Kingdom

Her Majesty Treasury Also known as the Exchequer, the HMT is a British ministerial department entitled with the responsibility to execute the country’s public finance and economic policies

Hollande, François Leftist politician, former President of France, 2012-2017

House of Commons The HoC is the lower House of the British Parliament

House of Lords The HoL is the upper House of the British Parliament

International Criminal Court (ICC, CPI)

The ICC is an intergovernmental organization that acts as court of last resort to try individuals charged with genocide, crimes against humanity, aggression, and war crimes.

Kouchner, Bernard Leftist French politician, former Minister of Health (1992-1993) and Minister of Foreign and European Affairs (2007-2010)

Martinez, Jean Luc French archaeologist, President of the Louvre Museum since 2013

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, OECD

The OECD is an intergovernmental organization established in 1961, whose mission is to promote economic and social development

Public Administration Select Committee (PASC)

The PASC is a Committee entrusted with the task of supervising the quality of administration within the British Civil Service

Sarkozy, Nicolas Conservative politician and former President of France, 2007-2012

Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) The UfM is an intergovernmental organization established in 2010 in the framework of the Barcelona process. It includes all member states of the European Union and fifteen countries of the Eastern and Southern Mediterranean. The mission of the UfM is to promote regional cooperation and dialogue around three key areas: stability, integration, and human development

Chapter 1. Introduction

The present chapter provides the outline of the research, including an explanation of the research framework and the research aim and objectives. The chapter also addresses methodology, as it presents the research design and the choice and implementation of data collection and data analysis methods.

1.1 General objective

The objective of this study is to contribute to the conceptualization of cultural diplomacy (1) and to develop a taxonomy to analyze different models of cultural diplomacy (2). Along the way the focus on the intension and the extension of the concept of cultural diplomacy has gradually led the author to articulate these objectives around the interaction between three key conceptualizations: a resource culture; an instrument diplomacy; and a relation -power. In other words, what started from a simple question – “How can we define cultural diplomacy?”- therefore a work on the blurred conceptual borders of a practice, turned out to be also a theoretical reflection on the changing nature of power in international relations and an attempt to understand how this may have impacted on the practice of cultural diplomacy. While the general objective of this research has been maintained, secondary propositions has slightly evolved over time, for the data pushed the author into areas that he had not anticipated. This is due to the hybrid deductive/inductive nature of this thesis. All in all, cultural diplomacy is an international corporate practice whose attributes are substantially shaped by power relations between international actors and within practitioners’ communities. At the same time, the practice of cultural diplomacy is by itself a source of emergent power. In other words, it is possible to argue that a circular relationship between culture, diplomacy, and power is in place. To gain a better understanding of this process, the author has developed an analytical model of state-driven cultural diplomacy and has tested it on the initiatives undertaken by the United Kingdom (UK) and France in the framework of their strategy towards partner countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region in the aftermath of the so-called Arab Spring.

In general terms, the objective of this study has been achieved. First, the author has developed a summative, integrative and original definition of cultural diplomacy on the base of detailed analytical work and on a radial categorization of cultural diplomacy: Cultural diplomacy takes place when a state actor (SA) relies on cultural power bases to pursue

specific foreign policy objectives in line with preferred hard and soft outcomes. Second, the author has established an original taxonomy to analyze different models of cultural diplomacy (PoC-PiC Taxonomy) and has tested it on selected case studies. Finally, the empirical evidence coming from the analysis of practices at contingency/short term level with an eye on long-term global power dynamics suggests that the practice of diplomacy is changing because the way global power is distributed and managed is changing and that change takes the shape of new forms of “polylateral” diplomacy. Both dynamics fit the PiC approach to cultural diplomacy.

1.2 Structure of the thesis

This thesis is structured as follows. Chapter 2 offers an extensive review of relevant literature as well as an analysis of models and theoretical frameworks that have been offered by previous scholarship. First, it dissects the concept of cultural diplomacy into two distinct driving components: culture and diplomacy. Then, attention is given to power. This part helps clarifying the relationship between the management of power, the related practice of public diplomacy and that of cultural diplomacy, an operation which is paramount to assess the evolution of cultural diplomacy and its place in the practice of power in international relations. Second, a detailed review of existing literature on cultural diplomacy is undertaken to assess the state of play in the exploration of the concept. This leads to the adoption of a formal typology based on the identification of two ways to understand cultural diplomacy: the “public diplomacy” approach, according to which “…the government has a monopoly on the practice and goals of cultural diplomacy…” (Isernia and Lamonica, 2016:2), which is used to mobilized soft power; and the “cultural relations” approach, which looks at cultural diplomacy as a practice based on mutuality and cooperation, detached from a soft power framework. In an effort to bridge the gap between academics and practitioners, this review of literature is also corroborated by hints coming from practitioners’ knowledge and experience.

Chapter 3 introduces the core theoretical contributions of this thesis. First, the changes diplomacy is undergoing and how this frames the evolution of cultural diplomacy and the academic confusion surrounding its concept are briefly discussed. Second, the author summarizes the state of the art of conceptual work on cultural diplomacy as it emerged from the review in Chapter 2. Third, based on the analysis conducted so far, an original categorization and the resulting definition of cultural diplomacy are proposed. Finally, an

analytical model for cultural diplomacy is introduced, to provide a theoretical framework to conduct the empirical part of this research.

Chapter 4 provides a historical frame of reference for the evolution of state-driven cultural diplomacy, with a focus on the cases of France and the United Kingdom. First, it offers a structural analysis of the historical evolution of state-driven cultural diplomacy as it took place during the Twentieth century in “Western” countries, with a focus on the process that goes from initial one-way cultural diffusion to contemporary multilateral cultural cooperation. Second, the chapter addresses the development of France’s and the United Kingdom’s peculiar models of cultural diplomacy. On the one hand, it examines the complexity of the historical roots of French cultural diplomacy, from the Nineteenth century to the building through the Twentieth century of the first and most sophisticated model of state-driven centralized cultural diplomacy. Furthermore, it offers an overview on the current model of French cultural diplomacy, including the current administrative structure in charge of French cultural diplomacy and a focus on the ministries and state operators involved as well as on the principles and priorities framing their activity. On the other hand, the chapter examines the evolution of the historical model of the United Kingdom’s cultural diplomacy through the story of its main actor, the British Council (BC). First, the initial steps undertaken in the realm of external cultural relations by the BC since its creation in 1934 are analyzed, with a focus on the early and problematic definition of the British Council’s institutional perimeter and of the gradual structuring of the United Kingdom’s global, efficient, and sophisticated decentralized cultural network. Second, an overview is offered of the state of UK’s cultural diplomacy to date, with special attention devoted to the organizational structure of the British Council and a focus on its roles and responsibilities, the nature and scope of its core activities, as well as its financial resources.

Chapter 5 provides an in-depth analysis of the data collected and the implications for the research objectives. In particular, it traces the processes that brought to the introduction of new practices of cultural diplomacy by France and the UK between 2011 and 2018 in the MENA region. To do so, it discusses the case studies under scrutiny -the Cultural Protection Fund (CPF) and the Young Arab Voices Programme (YAV) for the United Kingdom, the Aliph Foundation and the SafirLAB Programme for France- and presents the results of the empirical analysis through the lenses of the analytical model which is supposed to frame them. The analysis builds off of the main assumption that the evolution of France and the

UK’s practices of cultural diplomacy, with reference to their action in the MENA region following the Arab Spring, is due to the mobilization of a new form of “hybrid power”, which relies on both the co-optive side of the hard dimension and the command side of the soft dimension. Furthermore, France and the UK substantiate this new form of power in innovative polylateral frameworks, a type of collective mobilization. Such evolution is addressed in chapter 5 by dissecting the phenomenon and analyzing its constituent elements, namely the global power politics dimension -which frames the long-term strategic approach- and the foreign policy-contingency dimension -which informs the short-term tactical approach. Finally, based on the frame provided in chapter 4 and the empirical results of chapter 5, chapter 6 concludes the study and summarizes the achievements of the research. It also suggests scope for further research and comprises acknowledgement of limitations of the study.

1.3 Research framework

In general terms, the research framework proposed in this thesis adopts a neoliberalist perspective while leaning toward a constructivist ontology and epistemology, with the resulting normative and methodological implications. Figure 1 shows a schematic and visual representation of such framework. It is based on the conceptual model for deductive case study projects proposed by Verschuren and Doorewaard (2010). Three phases can be distinguished: the construction of the theoretical framework (a), based on extensive literature review and preliminary empirical research; the gathering of the empirical data (b), which consists of three empirical data sets created after operationalization; and the data analysis (c). The broken line indicates the theoretical part of the study, which results in the analytical model. The vertical arrows stand for confrontation symbols, while the horizontal ones represent inferences.

Research question

The research question is straightforward: How can we define cultural diplomacy and categorize different models of cultural diplomacy in the light of its cross-boundary, hybrid nature?

1.4 Methodology

The method adopted is the Case study method (Yin, 2002). The type of design is a multiple-cases design with embedded units (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Multiple-cases design with embedded units. State-driven Cultural Diplomacy: The cases of France and the United Kingdom

United Kingdom France

CPF

YAV ALIPH

SAFIRLAB

Case selection

Concerning the selection of cases, purposeful selective sampling was adopted to identify the country units, France and the United Kingdom. Conversely, country sub-units were chosen to develop the case studies without resorting to sampling methods.

France and The United Kingdom

The selection of units -country cases- was guided by a maximum variation sampling. Looking for information-rich cases for in-depth knowledge of current European actors’ practices of cultural diplomacy, France and the United Kingdom were “natural” candidates. From a historical point of view, the two are considered pioneers in the implementation of international cultural policies within the framework of their foreign relations. All differences considered, France and the United Kingdom were the first among Western countries to consider culture a soft-power resource and have long established models that date back at least to the first half of the Twentieth century. To date, they still have some of the most extensive international cultural networks.

Moreover, France and the United Kingdom perfectly represent the two main models that have traditionally shaped the practice of cultural diplomacy, namely the centralized model and the de-centralized one. Indeed, a structural analysis of how state actors have organized their cultural diplomacy from the Second World War onward shows that, besides the coexistence of a plurality of approaches that variously differ on the actors in charge, the purposes, the size of funding, and the implementation, it is possible to distinguish these two main approaches to state-driven cultural diplomacy. On the one hand, the centralized approach entails that all the phases included in the practice of cultural diplomacy, from the shaping of the overarching strategy to the implementation and monitoring, are directly overseen by a country’s government, generally under the governance of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. On the other hand, the de-centralized approach follows the Arm’s Length Principle, according to which a country’s government transfer the management of its external cultural relations to semi-independent agencies, which enjoy operational independence while being at the same time under the government’s aegis. As reported in the Preparatory Action. Culture in EU’s external relations (Isar et al., 2014: 30-32), two-third of the EU member States have a decentralized model (Arm’s length approach), while one-third employ a centralized model. Indeed, France has traditionally adopted and refined the

latter, while the United Kingdom was a precursor of the Arm’s Length relationship between an agency in charge of cultural diplomacy and its government.

France has a centralized model, wherein the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) has direct coordination and strategy role in cultural diplomacy, through a dedicated Directorate-General. Policy implementation is handled by a number of State operators, among which the key ones are: the Institut Français, MFA’s key operator for cultural diplomacy, whose objective is to “strengthen France’s influence worldwide and to encourage international cultural exchange”; the Agency for French Education Abroad (AEFE), to serve and promote a school network abroad (488 schools based in 130 countries); Campus France, whose mission is to “improve academic and scientific attractiveness and mobility”; and France Médias Monde, which “manages and coordinates the activities of public radio and television stations owned by the French State with an international broadcast” (France 24, the trilingual news channel; RFI, world radio; Monte Carlo Doualiya, the universalist radio in Arabic). (French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2019c)

Conversely, the United Kingdom has developed a more decentralized model, based on a complex network of semi-independent arm’s length governance bodies appointed for the sake of promoting and implementing international cultural policies. While the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) is the department entrusted with the responsibility for foreign affairs, it has limited direct responsibility for the managing of international cultural relations (ICR), which are primarily supervised by The British Council. The British Council is an “executive non-departmental public body, a public corporation (in accounting terms), and a charity”. It is “operationally independent from the UK government” and “does not carry out functions on behalf of the Crown”. At the same time, it receives grant-in-aid funding from the FCO, the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs answers to parliament for its policies, operations and performance, and it is strategically aligned to the long-term foreign policy priorities of the FCO. (British Council, 2018a)

The MENA region

This study focuses on the initiatives of cultural diplomacy that are being undertaken by France and the United Kingdom in a specific region, namely the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), and in a specific time period, corresponding to the years between the beginning of the so-called Arab Spring (2011) and the present time (2018). The MENA region is clearly strategic for both France and UK, and the two countries’ international

relations with this geopolitical area have deep implications. Some of the most substantial security, economic and political issues pass through the strengthening of the relations with North African and Middle Eastern countries, which have been recently shaken by political instability, social unrest and an increasing lack of security. Therefore, in the last years the UK and France have devoted increasing attention to the development and implementation of effective relations with Middle Eastern and North African neighbors, particularly after the waves of revolutions and unrest that have been taking place since 2011. Culture has been an essential component of their policies in the region, mostly in the framework of functional bilateral and multilateral cooperation, wherein security, stability, and economic development are increasingly seen as reachable outcomes. The empirical component of this study builds off of the assumption that, all differences considered, French and British responses to the so-called Arab Spring have been framed by the perception of a security threat generated by the lack of stability in the area (foreign policy framework) and provided a springboard for both countries’ desire to maintain and strengthen their influence in the area (global power dynamics).

Country sub-units

As anticipated, the analytical model of contemporary cultural diplomacy that is proposed in this thesis consists of two dimensions, the PoC and the PiC. The PoC embodies a traditional view of cultural diplomacy as a pillar of public diplomacy, therefore an instrument of soft power, that has been widely studied over the years (see chapter 2). Conversely, little or no research has been conducted in relations to the PiC component and the innovative practices of cultural diplomacy that fall in it, due to their recent introduction (see Chapter 3). This led the author of this thesis to devote special attention to those practices.

Therefore, concerning the selection of sub-units, three wide outcomes of cultural diplomacy have been privileged: development, stability, and security. The three have been “operationalized” through the adoption of two main work streams: culture for inter/intra-community relations; and the protection of cultural heritage1. The choice to focus on these

1 On June 2016, the Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council Towards an EU strategy

for international cultural relations was issued by the European Commission and the High Representative of

the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. The Communication proposes three work streams to advance cultural cooperation with partner countries: supporting culture as an engine for sustainable social and economic development; promoting culture and intercultural dialogue for peaceful inter-community relations; reinforcing cooperation on cultural heritage (JOIN/2016/029, 2016:7). The works streams of this research have been shaped after the two latter.

specific outcomes and to operationalize them through the aforementioned work streams builds off of the analysis of current institutional narrative. The use of culture to foster peaceful inter/intra-community relationships and the protection of cultural heritage are widely regarded as pillar of the new cultural relations approach to cultural diplomacy. However, data analysis shows that, while the PoC approach is meant to improve influence and attraction, the most recurring outcomes pursued with the PiC approach are mostly related to middle- and long-term foreign policy objectives such as development, security, and stability. Based on these considerations and in order to develop both country cases, two projects (sub-units) for each country unit have been selected (see Table 1).

Work stream 1: Cultural heritage protection

Sub-unit A: The Cultural Protection Fund Programme (CPF) [United Kingdom: 2016, ongoing]. The Cultural Protection Fund (CPF) has been launched in June 2016 by the UK government with a £30m support over the period 2016-2020. It builds on a partnership with the Department for Culture, Media, and Sport (DCMS) and the British Council, which is in charge of the implementation and management of the CPF under the Culture and Development Programme. The CPF objective is “to protect and rebuild opportunities for economic development through building capacity to foster, safeguard and promote cultural heritage” (British Council, Evaluation Plan, 2016:7) affected by conflict in the wider MENA region (Afghanistan, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Iraq, Occupied Palestinian Territories, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey and Yemen) (Pugh and Bishop, 2018). All the CPF-financed actions fulfil the UK Official Development Assistance’s (ODA) strategic objectives: strengthening global peace, security and governance; strengthening resilience and response to crises; promoting global prosperity; and tackling extreme poverty (HMT, DFID, 2015).

Sub-unit C: The International Alliance for the Protection of Cultural Heritage in Conflict Areas (Aliph) [France: 2017, ongoing]. France has recently put in place innovative initiatives in the field of cultural heritage protection, in particular following the International Conference on Safeguarding Endangered Cultural Heritage (Abu Dhabi, December 2016), co-organised by France and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) under the auspices of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The conference had two main objectives: “the creation of an international fund for the protection of endangered cultural heritage in armed conflict [and] …the creation of an international network of safe havens”.

(UNESCO, Participation in Aliph, 2017:2). Following the Abu Dhabi Conference, Aliph was established by France in partnership with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) as an international fund in the form of a non-profit foundation under the laws of Switzerland. The purpose of the Foundation is “to attract…[and] manage…resources for the implementation of preventive and emergency protection programmes for cultural property in danger of destruction, damage or looting on account of armed conflict, and to contribute to [its] rehabilitation” (UNESCO, Participation in Aliph, 2017:Annex,1).

Work stream 2: Culture for inter/intra-community relations

Sub-unit B: The Young Arab Voices Programme (YAV) [United Kingdom: 2011, ongoing]. Launched in Alexandria, Egypt in October 2011, the Young Arab Voices (YAV) was a “regional project jointly managed by the British Council and the Anna Lindh Foundation and co-financed by both the European Union and the UK government’s Arab Partnership Initiative” (Anna Lindh Foundation, 2017). It was established in the aftermath of the Arab Spring to “…face common challenges related to building democratic and pluralistic communities and promoting public voice” (British Council, 2018b). The project had both a regional and domestic profile and was implemented in eight Arab countries in transition (Tunisia, Palestine, Morocco, Lebanon, Jordan, Libya, Egypt, and Algeria), involving more than 100,000 young Arabs (18-25 years old) in direct or indirect activities between 2011 and 2016 (Anonymous, 2017). For example, since 2011 in Jordan the project realized 107 debates and 142 training sessions involving 3,740 young people and reaching approximately 43,000 people (Karanàsou, 2017:10). In 2018 the second-stage of the programme, re-named “Young Mediterranean Voices”, has been expanded at larger scale with the outspoken purpose to make it the “…central flagship regional youth network connecting civil society, education institutions and policy-makers across Europe and the Neighbourhood South” (European Commission, ENI/2016/039-475, 2016:12).

Sub-unit D: SafirLab [France: 2012, ongoing]. Safirlab is a regional project born in the aftermath of the so-called “Arab Spring” and the subsequent France’s engagement in the Deauville Partnership for Arab countries in transition, with the aim to support them in their political transformation by engaging and empowering young Arabs. To do so, the programme set two goals : to « …enable young people involved in initiatives in the area of the media and civil society to develop their projects and share their experiences ; and to create a dialogue between young people with the same civic values and help build a mutual

partnership between France and countries south of the Mediterranean… » (CFI Media, 2018). Therefore, SafirLab’s objectives are aligned with the French government’s Arab policy and its necessity to identify new interlocutors in the region. The SafirLab programme has been commissioned and funded by the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and is jointly managed by the Institut Français (IF) and Canal France International (CFI) following a partnership established on July 2012. (CFI Media, Press release, 2012).

OUTCOMES Development SECURITY Stability

WORK

STREAMS Cultural heritage protection

Culture for inter/intra community relations

UNITED KINGDOM

[A] Cultural Protection Fund (CPF)

[B] Young Arab Voices Programme (YAV)

FRANCE

[C] Aliph Foundation [D] Safirlab Programme Table 1. Case selection

Data collection

To “construct” a substantial “corpus” of data (Flick, 2009: 258), a researcher should refer to a variety of written, audio, and visual artifacts that exist within natural, non-laboratory contexts (H. Raptis, 2010: 320-22). Therefore, this research has tried to use multiple sources of evidence. In the UK country-case, written documentation, interviews, direct and participant observations were collected and triangulated. The French case has seen the collection of data through documentation and interviews. In more detail:

Written documentation. In general terms, documents were chosen to develop the case studies and did not undergo rigorous qualitative analysis. This included: For the UK, British Council’s reports, minutes, policies and other procedural documents; Foreign and Commonwealth Office’s reports, minutes, and policies; UK Government’s reports, minutes, policies and acts of Parliament; letters, memos, notes. For France, Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ reports, minutes, policies and other procedural documents; French government’s reports, minutes, policies and other procedural documents. In both cases, sources included open and restricted documentation. In some cases, the author was asked to sign confidentiality agreements to access confidential data. Following H. Raptis’ suggestions

(2010:320-22), each source was checked for authenticity and credibility of on a regular basis, and sources were selected based on their representativeness and meaningfulness. Interviews. The author of this thesis is aware of the limits of documentary research in debunking practices, thus interviews play a special role in data collection. Combined with field notes and observational data, interviews allow for depth and breadth and they are crucial to obtain 'thick' (Geertz, 1973:26) and rich descriptions to show “…different and complex facets of particular phenomena…”, generating a “…richness of perception…” (Holliday, 2002:78). This is paramount in this research, which focuses on contemporary events. Concerning the modalities, some interviews were conducted face to face, others by telephone or online (skype). Most of them were audio-taped using a digital sound recorder. Recordings were transcribed, and transcripts coded as documents in the analysis. Field notes documenting interview process were also used as data source. The author opted for in-depth, semi-structured interviews. Interviews addressed a number of predetermined topic areas, although not all topics were prepared in advance, and many conversations evolved during the interviews. Whenever possible, the author tried to collect data through informal interviews as well, by recording as field notes all casual conversations occurring prior to/after the interviews or during direct observation. Interviewees were experts, policy makers, practitioners (diplomats, high-level officers, projects managers), and the recipients of the initiatives under scrutiny. Their personal views, experiences, knowledge and interpretations proved to be a precious source. Appendix 1 contains all relevant information concerning the interviewees, while Appendix 2 reproduces the standardized consent form. It is acknowledged here that, due to resource and time constraints and may be a certain degree of organizational disfunction, the number of in-depth and semi-structured interviews that the author succeeded in conducting may not be considered satisfactory.

The methodological challenges relating to the anonymity, confidentiality, and consent of informants have also been addressed. The author is aware that participant consent is problematic from a methodological point of view, especially because of “behavioral changes due to awareness of scrutiny”, the so-called Hawthorne effect (C. deRoche & J. E. deRoche, 2010: 216-18). To find a balance between ethical consideration and the integrity and value of the study (P. Wallace 2010), a written consent form was adopted as standard procedure (see Appendix 2). The consent form includes a quotation agreement and the consent to recording; it also informs participants about research purposes, procedures, and data

treatment. The methodological framework included the analysis of 18 in-depth interviews. Interviews were divided into three distinct interview data sets (see Appendix 1):

- data set 1: preliminary empirical research to develop the categorization of cultural diplomacy and the resulting analytical model;

- data set 2: United Kingdom, sub-units A and B. Data collection to develop the British case study;

- data set 3: France, sub-units C and D. Data collection to develop the French case study. Direct observation. This is a crucial source of evidence that “…provides insight into the taken-for-granted aspects of everyday activities that may go unreported by participants, gives the researcher direct experience of the phenomena being studied, and creates an opportunity to see and hear what is happening in a social setting rather than focusing solely on narrative descriptions of participants.” (B. M. Pauly, 2010: 301). As a consequence, the author tried to practice direct observation in the social settings relating to the cases. This successfully took place during the fieldwork in the UK (October 2017-February 2018), where the author had the chance to observe directly what was happening and interact with participants. In the specific case of the British Council, observation was completely unstructured at the beginning and became more selective over time. The author tried to engage in “systematic seeing” to make accurate, reliable, and relevant observations (B. M. Pauly, 2010:302). To avoid covert data collection, verbal consent was asked as a standard procedure. Unfortunately, direct observation was very limited during the French fieldwork (March – June 2018).

Participant Observation. According to M. Di Domenico and N. Phillips, participant observation involves “…observing and interacting with the subject of interest while actively participating in the setting as well as getting very close to research participants and gaining an intimate knowledge of their practices through intensive immersion in the field of study” (2010:654). During the fieldwork in the UK, the author’s role as an observer changed as he was directly involved in the activities of the British Council. In particular, the author was asked to join the research team to carry out primary research on the BC’s model of cultural relations. Direct observation turned into participant observation. Moreover, the extended period of the fieldwork at the British Council allowed the author for in-depth immersion and overt participant observation. This included: observation, informal interviews, conversations, personal accounts and stories of participants, and the author’s diaries. Unfortunately, during the French fieldwork the author’s position as an external researcher -hosted by the

University of London Institute in Paris- partially jeopardized his effort to practice participant observation at bureaucratic and governmental level.

Field notes. According to L. Gambold, “…Taking down field notes is the act of recording one’s research data as well as the beginning of communicating one’s research findings with others. The creation of a permanent record of events, interviews, interpretations, and ideas allows researchers to be clear about what they think they know…” (2010:396). Gambold quotes the words of Clifford Geertz, who once wrote that with field notes “…case study researchers inscribe social discourse, turning it from a passing event, existing only in its own moment of occurrence, into an account, which exists in its inscriptions and can be reviewed at a later time...” (2010:396). Accordingly, the author tried to keep field notes updated and deep from the very beginning of the inquiry. Some notes are descriptive, some others are just words. The author noted questions rising during data collection at all levels, reflections on the literature review, impressions and details. As a standard procedure, he regularly went back to his notes, which have been organized in a database on the base of appropriate categories, to review, expand, articulate them, in line with the iterative and hybrid data analysis he conducted. All field notes, together with a sort of “reflexive journal” (Begoray and Bannister, 2010:788), were part of the author’s research diary.

Validity and Reliability. As data collection entails a number of methodological issues, some tactics to ensure construct validity and reliability were adopted (R. K. Yin, 2002:34-39): • Construct validity. During data collection, correct operational measures were ensured by

using multiple and convergent sources of evidence and establishing a chain of evidence (Yin, 2002:34-39). Data triangulation was used to strengthen conclusions, for it increases the probability of an '…accurate and reliable theory…' (Huberman and Miles, 2002: 19) and a '…stronger substantiation of constructs and hypotheses…' (Huberman and Miles, 2002:14). To further mitigate concerns related to construct validity, key informants were asked review drafts;

• Internal validity. As this inquiry was mainly exploratory (what/how), it was not concerned with making strong causal claims. Therefore, internal validity was not strictly required per se. However, the author proposed an analytical model and set a number of related assumptions. Therefore, some analytic tactics were adopted (see data analysis) to improve credibility in loose terms;

• Reliability. To increase confirmability (Lincoln and Guba 1985), a case study protocol was established to document the research process, and a case study database was developed. The case study protocol is based on standardised procedures (see Appendix 3), while the database was revised and updated on a regular basis, along with a research diary.

Data analysis

Data analysis requires a well-designed general strategy. R. K. Yin, one of the most renowned experts in case study research, suggests three main strategies to examine, code, and test data: relying on theoretical propositions, which “…[shape] your data collection plan and therefore [give analytical] priorities…”; defining and testing rival explanations; developing a case description “…to identify the appropriate causal links to be analyzed.” (Yin, 2002:109). The general objective of this research was based on a conceptual proposition, which in turn gave birth to an analytical taxonomy. During data collection, the author tried to rely on this taxonomy as much as possible. This helped to prioritize some data and organize the case study. To further improve the organization of case study analysis, a descriptive framework was also developed. However, to deal with the aforementioned issues relating to internal validity, specific techniques were included at general analytical level.

In more detail, this thesis relied on explanation building, a technique derived from pattern matching. According to T. Hak and J. Dul, pattern matching is “…the comparison of two patterns to determine whether they match… or do not match… Pattern matching is the core procedure of theory-testing with cases. Testing consists of matching an observed pattern (a pattern of measured values) with an expected pattern (a hypothesis) and deciding whether these patterns match (resulting in a confirmation of the hypothesis) or do not match (resulting in a disconfirmation). Essential to pattern matching… is that the expected pattern is precisely specified before the matching takes place" (2010:663). While pattern matching is a quite desirable technique for case study analysis, its rigor does not fit the research framework of this thesis, which has limited explanatory purpose. Conversely, while explanation-building shares with pattern-matching the idea of explaining a phenomenon by resorting to a set of assumptions, it is more flexible and iterative as the theoretical premise does not need to be fully stipulated at the beginning of the research and the process is gradual (Yin, 2003:122). Therefore, it allows for the adoption of a hybrid deductive/inductive

process. In operational terms, as suggested by Yin, the author conducted data analysis by following a series of iterations:

- “Making an initial theoretical proposition;

- Comparing the findings of one unit of study against such a statement; - Revising the proposition;

- Comparing other details of the unit of study against the revision; - Comparing the revision to the data of the second unit of study; - Repeating this process as many times as is needed”. (2003:122)

Finally, the author tried to strengthen this practice-based methodology by resorting to Practice Theory. In the author’s opinion, a turn to a more rigorous approach to the study of practice can corroborate the analysis of the case studies. The main underlying consideration is that cultural diplomacy is an international corporate practice. It is a practice because is a performance, is patterned, is competent in socially meaningful ways, it rests on reflexive and background knowledge, and waves together the social and the material world. Second, it is international and corporate because is performed by collectives, is political and it sustains patterns of power relations (Adler and Pouliot, 2011). Moreover, it relies on culture, which is a “…dynamic and mutually conditioned play between discourse and practice…” (Neumann, 2002). Therefore, if change in power dynamics also emerges from practice itself, linguistic analysis may no longer be a reliable analytical tool alone and deep analysis of practice should be benchmarked against it. A review of main contributions to the practice turn in international relations will help to dissipate doubts.

As noted by Cornut (2015), constructivists (e.g. Alexander Wendt, Fredriech Kratochwil, Nick Onuf), post-positivists (Roxanne Lynn Doty, Lene Hansen), and critical theorists (Richard Ashley) have addressed the role of practice over time. However, they looked at practice as an ancillary concept, thus devoting little time to its theoretical implications. In the last years, a number of theoretical approaches that build on practice as main category of analysis have been introduced to the study of international relations. Many of them share “…an emphasis on process, sensitivity for different forms of knowledge and learning, and an understanding of the world as performative and anchored in materiality…” (Wille, 2018). While practice-theoretical approaches are characterized by diversity and basically meta-theoretical, they all share a view of practice as a leading concept. Such approaches draw

from conceptual frameworks transposed from philosophy (Ludwig Wittgenstein, Martin Heidegger), anthropology, and sociology (Pierre Bourdieu, Michel Foucault). The main tenets of such practice turn in international relations will be addressed by discussing its main contributions. First, the seminal “manifesto” proposed by Neumann (2002), who highlighted first the benefits of the interaction between discourse and practice analysis, will be discussed. Then, attention will be turned to Adler and Pouliot (2011) and J. Cornut (2015) in order to provide an exhaustive description of the components, the basic logic, and the methods relating to practice theory. Finally, it will be suggested that the study of practice can substantially corroborate the understanding of global power dynamics by introducing the study of Alder-Nissen and Pouliot (2014).

In the early 2000s, Neumann was the first to argue that the linguistic turn in social sciences also entailed a turn to practice, thus implying that “…the analysis of discourse understood as the study of the preconditions for social action must include the analysis of practice understood as the study of social action itself…” (2002:627). His suggestion relied on the analysis offered by Schatzki, Knorr-Cetina & von Savigny in The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory (2001), the first book to exhaustively tackle the flaws of the over-reliance on linguistic analysis in social sciences, and on Barnes’ definition of practices as “…socially recognized forms of activity, done on the basis of what members learn from others, and capable of being done well or badly, correctly or incorrectly…” (Barnes, in Schatzki et al., 2001:17). Therefore, Practices, Neumann argues, are integrative, improvisational, reflective, and performative. In other words, practice is characterized by dynamism, and dynamism implies change. To address change in the practice of diplomacy, he proposes a new methodological approach based on the analysis of the interplay between discourse and practice: “…The re-framing of the study of diplomacy and other aspects of discursive mediation—social and political—that has taken place in the wake of the linguistic turn in social inquiry may be followed up by a practice turn, in which empirical work will take centre place.” (Neumann, 2002: 651).

Neumann’s was a seminal but quite early call for a reflection about the role of practice. Since then, several scholars followed up and refined the argument. Among them, Adler and Pouliot gave a substantial contribution to the development of these ideas in their edited book “International practices” (2011). They propose an inter-paradigmatic research program centered on the analysis of practices to understand world politics. Their work is a reply to

Neumann’s call for a practice turn, which, according to them, builds on the influence of Michel Foucault, Pierre Bourdieu, and early constructivists’ interest on practices. In the next paragraphs, their notion of practice and its components, the theoretical implication it has for the study of international relations, and its contribution in terms of research streams and methodologies will be addressed.

Adler and Pouliot view practices as “…socially meaningful patterns of action which, in being performed more or less competently, simultaneously embody, act out, and possibly reify background knowledge and discourse in and on the material world…” (2011:6). International practices are types of action socially developed in the organized context of world politics; most international practices are corporate, in the sense that they are performed by communities. Unpacking their definition, the two authors detect five main features: first, practices are performances, “…a process of doing something…”; Second, practices are patterned, as they “…generally exhibits certain regularities over time and space…” and “…are part of a socially organized context, which not only gives them meaning, but also structures interaction”; third, practices are “competent in a socially meaningful and recognizable way”, therefore their dimension also depends on social recognition; fourth, practices builds “background knowledge”, which means that knowledge is reflexive and intersubjective but embedded in practice; Finally, while practice is enacted by discourse, it is also mediated by material artifacts: in Alder and Pouliot’s words, “…language [is] the conduit of meaning, which turns practices into the location and engine of social action… [however] practice… is [also] enacted in and on the world, and thus can change the physical environment as well as the ideas that individually and collectively people hold about the world…” (2011:7).

Adler and Pouliot claim that practice provides a conceptual structure to foster inter-paradigmatic conversation in international relations. Instead of promoting a homogenization of paradigm, practice’s broad ontology breaks “…Cartesian dualism between materials and ideas…” (2011:12) by overcoming dichotomies in social theory. Practice theory comes as a last step in the conceptualization of culture. Building on the mentalist approach to culture relying on social and cognitive psychology, on poststructuralism, and constructivism, practice theory is “an invitation … to conceive of the social as bundles of ideas and matter that are linguistically, materially, and intersubjectively mediated in the form of practices.

Culture, in other words, is not only in people’s minds, discourse, and interactions; it is also in the very performance of practices.” (2011:13)

According to Adler and Pouliot, inter-paradigmatic conversation is made possible by the fact that practices disrupt a number of theoretical dichotomies, namely those between matter and meaning, agency and structure, reflexive and background knowledge, stability and change. First, “…practices are both material and meaningful…”, as they are patterned action enacted in the world and speech acts at the same time. Second, practices are both individual and structural; they allow for agency by translating “…structural background intersubjective knowledge into intentional acts and endow[ing] them with social meaning…”, while at the same time they are embedded in a socially recognized political order. Third, practices builds on reflexivity but also on intersubjective knowledge. Finally, as patterns of action, practices embodies stability; at the same time, dynamic intersubjective mediation makes them a generator of social change (2011:13-17). Adler and Pouliot further builds on the ability of practice to generate change. They argue that this is possible in the domains of subjective preferences, in structures and discourse, and in the practice itself. From this point of view, practice is both explanans and explanandum. It is the duty of the scholar to clarify which approach s/he takes. In this regard, Adler and Pouliot suggest two distinct frameworks. If one treats practice as an explanandum, he could adopt the “lifecycle of practice” framework, which analyzes that generation, the diffusion, the institutionalization, and the fading of a practice. If, on the contrary, one conceives practice as explanans, s/he can focus on how practices are performed – “agency and contestation”- or on how practices interact – “interplay of practices”. In both frameworks, practice is political, because “…it sustains, or undermines, existing patterns of power relations” (2011: 18-21).

Finally, Adler and Pouliot propose an agenda to foster inter-paradigmatic research on practice. They identify eight practice-oriented streams, two of which are of particular interest to this thesis: power and practice, and the balance of practices. First, the notion of practice substantiate the view of power as relational. Second, they argue that “…States may differ not only in their political, social demographic and economic make-up, material capabilities, and historical cultural contexts… but also in the institutionalized practices of their communities of practice” (2011:30). Therefore, “differences in the ways states deploy practices in the world scene have structural effects, and … these effects may be as if not more important than material power, interest, and knowledge” (2011:31).

So far, the notion of practice and its components, the theoretical implication it has for the study of international relations, and its contribution in terms of research streams have been discussed. It is worth to examine the epistemological, normative, and methodological challenges this entails for this thesis.

Epistemology

According to Cornut (2015), practice-based approaches refute neopositivism and the claim that the world can be explained (Navari 2011; McCourt 2012). Practices are observable traces through which scholars can infer habits; however, their analysis is affected by the subjectivity of the researcher. As a consequence, practice-based approaches mainly rely on an interpretivist epistemology; in this regard, “…the praxiographic research process is one of turning implicit knowledge into explicit…” and “…this implies a high degree of interpretation.” (Bueger 2014:389, in Cornut 2015:17). The reliance on interpretivism to study practices also entails that such process should be reflexive, meaning that the researcher must take her own belonging to a community (Adler and Pouliot 2011) or a field of practice (Adler-Nissen and Pouliot 2014) into proper account. In Cornut’s words, “…if each field has particular doxa, hierarchies, and rules of the game, the scientific field is defined by its own (scientific) doxa, hierarchy, and rules of the game. Thus, the tools used to analyze social realities could and should also be used to analyze the field of research itself” (Cornut, 2015:18).

Normativity

Contrary to the wide consensus on an interpretive, pragmatic, and reflexive epistemology, Cornut argues that the normativity of practice-based approaches is contested, and he distinguishes three main views: solving, critical, and mainstream. The problem-solving approach entails that practice scholars should engage with practitioners and get involved at normative level, thus producing policy-relevant research. Along this line, other scholars take a more critical and direct stance. According to Cornut, they “…envision their work as siding with the dominated. Instead of producing policy-relevant works that reinforce the status quo and support the dominating class, they consider that PT analytical tools unravel the multiple ways through which the domination is produced and reproduced in practice…” (2015:19). Conversely, mainstream practice researchers reject both policy-oriented and critical normative approaches, for they are not interested in bridging the divide between theorists and practitioners. The study of practice offers tools that do not allow for