Introduction

Fatigue is a common symptom in the community, with up to half of the general population reporting fatigue in large surveys (1, 2). It also is reported by at least 20% of patients seeking medical care (3, 4). Typically the fatigue is transient, self-limiting, and explained by prevailing circumstances. However, a minority of persons experience persistent and debilitating fatigue. When the fatigue cannot be explained by a medical condition such as anemia or hypothyroidism, it may represent chronic fatigue syndrome.

1.1

History

Feelings of physical fatigue and "mental exhaustion" are common experiences that constantly accompany even a simple colds or flu. In some cases, such symptoms may precede or extend beyond the resolution of primitive physical disorder suggesting the existence of a syndrome in which the autonomous psychic exhaustion and physical exhaustion symptoms could represent the nucleus of physical symptoms. These observations have always stimulated the interest of clinicians.

In 1750 Sir Richard Manningham described a disorder, which the author called "febricula" or "little fever", characterized by a slow but continuous change in temperature and associated with a feeling of physical fatigue, ―mental exhaustion‖, cognitive disorders and body aches. However, only in 1869 was coined the term "neurasthenia" by George Miller Beard. The author described a syndrome characterized mainly by physical fatigue and ―mental exhaustion‖, associated with difficulty in concentrating, impaired memory and reduction of interest. Beard (1880) then outlined numerous varieties of the disorder characterized by a

different set of symptoms and/or etiological factors. Cerebral neurasthenia, neurasthenia emotional or intellectual, or spinal neurasthenia mieloastenia (whose main symptom is the back pain), traumatic neurasthenia, neurasthenia or nervous dyspepsia and digestive emineurastenia with symptoms localized to a single emisoma, represented, according to the author, different expressions of the same disorder. Several other clinical criticized the ideas of Beard; Savill (1906), for example, proposed a "global" vision of this condition, denying the value of a classification according to the concerned organs. Beard had also operated a sort of "nationalization" of neurasthenia (American nervousness), which was deemed the result of the increased demand for mental energy to the rapid changes in the American society of the time. But when the interest in neurasthenia landed in Europe, it was clear that there were no significant differences in the incidence of the disorder in the two areas.

Charcot (1889), by analyzing the symptoms described by Beard, isolated the most important ones giving them a pathognomonic significance. These symptoms were represented by neuromuscular asthenia, cervical and lumbar back pain, chronic headache, dyspepsia with sleepiness, abdominal distension, constipation and, finally, by a morbid state of mind characterized by intellectual weakness with impaired memory and depressed and irritable mood.

Secondary symptoms depend on the interested side of the sensory organs and the cardiovascular, respiratory and genital tract. With Charcot, neurasthenia captured a leading nosographic position, becoming a ―major neurosis ―like hysteria. In the Salpetriere school, hysteria and neurasthenia had a central role and Ballet (1908) described four types of neurasthenia: genital, traumatic, cerebrospinal and feminine. At the initial pathogenetic hypothesis of Beard, based on the concept of "energy balance" and clearly influenced by the formulation of the thermodynamics laws, which once dominated the scientific world, were

then substituted concepts based on the psychological imprint. In this purpose, it is paradigmatic the title that was published in Italy at the beginning of the last century, a popular science text of the Swiss physician F. Ruch: Moral Treatment of neurasthenia in its main forms. Despite the syndromic division operated by Beard is substantially maintained, the author, describing the two most frequently encountered symptoms in medical practice, such as dyspepsia and constipation, it provides an essentially psychological interpretation suggesting an exclusively psychotherapeutic approach. The increased interest in mood disorders, no longer limited to severe forms such as the melancholy that required hospitalization, but extended to minor clinical features, also helped to establish that the neurasthenia was understandable on the basis of psychological explanations or to replace it with other psychiatric diagnoses. At the beginning of the century, Kraepelin (1902) pointed out that the neurasthenic subjects had a not suicidal mood disorder. Dana (1904) began to dismantle the old concept of neurasthenia and later Lane (1906) also rejected the prevailing notion of neurasthenia as a result of overwork, and he regarded as the main reason "the continued influence of depressive feelings". Bleuler (1924) wrote: "What usually produces the so-called neurasthenia are affective disorders‖ and as Tinel said (1941) ―the neurasthenia is a minor form of melancholic psychosis‖. With the extension of the concept of depression what remained of neurasthenia was finally incorporated in the depression, and the ―nervous breakdown" of Kraepelin became "low depression" (5, 6).

More recently, Lecrubier et al. (7) on the basis of different responses to drug treatments, have identified two types of attenuated or dysthymic depressive syndromes: timopathic syndromes associated with agitation, feelings of worthlessness and guilt, irritability and thoughts of death and timasthenic syndromes characterized by fatigue, slowing, anhedonia, decreased interest and anergy. The term timasthenia has then defined clinical features similar to those previously

identified as neurasthenia. Although the term "neurasthenia" is progressively released from use in the Western psychiatric literature, the persistence of this ICD-10 nosographic category seems to testify that the interest in this syndrome has never been completely extinguished. In the last 20 years the term ―neurasthenia‖ has fallen into disuse, especially when in 1994 Fukuda et al. have outlined the criteria for an identical nosographic entity: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) (8).

1.2

Definition

In the 1980s, the interest in fatiguing illnesses was rekindled by reports of outbreaks of a chronic debilitating illness that was associated with various virological and immunological abnormalities (9). Subsequently, the United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) named this illness ―chronic fatigue syndrome‖ and developed a case definition that was created primarily to standardize the patient population for research studies (10). The case definition facilitated a systematic and comprehensive approach to defining the etiology and pathophysiology of the syndrome by removing the implication of a causative agent such as Epstein-Barr virus.

A 1994 revision of the CDC case definition (8) constitutes the current criteria for CFS and the most widely used definition internationally. This definition requires at least 6 months of persistent fatigue that substantially reduces the person’s level of activity. In addition, four or more of the following symptoms must occur with fatigue in the 6-month period: impaired memory or concentration, sore throat, tender glands, aching or stiff muscles, multijoint pain, new headaches, unrefreshing sleep, and postexertional fatigue. Medical conditions that may explain the prolonged fatigue as well as a number of psychiatric diagnoses (i.e., eating disorders, psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, melancholic depression, and substance abuse within 2 years of the onset of fatigue) exclude a patient from the diagnosis of CFS. Those who do not meet the fatigue severity or symptom criteria can be given a diagnosis of idiopathic chronic fatigue. A notable feature of the CDC case definition is that many nonpsychotic psychiatric disorders are not exclusionary for the diagnosis of CFS. In addition, like psychiatric diagnoses, CFS is defined on the basis of expert consensus, and its diagnosis is made on the basis of symptom criteria.

Finally, chronic fatigue syndrome is an illness characterized by profound disabling fatigue lasting at least 6 months and accompanied by numerous rheumatological, infectious, and neuropsychiatric symptoms (8). As the name implies, it is a symptom-based or clinical diagnosis without distinguishing physical examination or routine laboratory findings. Infectious, immunological, neuroendocrine, sleep, and psychiatric mechanisms have been investigated; however, a unifying etiology for CFS has yet to emerge. It seems likely that CFS is a heterogeneous disease with different pathophysiological disturbances that manifest with similar symptoms. Regardless of the pathogenesis, persons with this syndrome, like those with other chronic diseases, have a substantially impaired functional status that results in significant personal and economic morbidity (11, 12).

1.3

Epidemiology

Estimates of the prevalence of CFS have varied depending on which definition was used, the type of population that was surveyed, and the study methods (13). These estimates range from 0.007% to 2.8% in the general adult population (14-16) and from 0.006% to 3.0% in primary care or general practice (2, 17, 18). Chronic fatigue syndrome also occurs in children and adolescents but apparently at a lower rate (19).

Early reports from tertiary clinics suggested that CFS affected primarily young, white, successful women. Indeed, most persons who receive a diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome are 30–40 years of age, and most surveys support a female preponderance (14, 15). However, community surveys have found that white individuals have a lower risk of CFS, compared with Latinos (14), African Americans (15, 18), and Native Americans (15). These disparate findings suggest that the increased prevalence of this syndrome among whites in clinic populations is most likely the result of a bias attributable to health care access and utilization.

1.4

Etiology and physiopathology

Despite more than a decade of research, the etiology of chronic fatigue syndrome remains elusive. Many theories for the pathophysiology have been suggested, with earlier theories focusing on the prominence of symptoms that suggested an acute viral illness or a psychiatric disorder. Subsequent investigations have documented abnormalities in rather disparate domains, including brain structure and function, neuroendocrine responses, sleep architecture, immune function, virological studies, exercise capacity, and divergent psychological profiles (20). Despite the demonstration of abnormalities across these and other domains, such findings remain largely isolated observations, with the interactions and relationships among them unexplored. In addition, some more recent investigations have focused on understanding the heritability of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome. It is possible that chronic fatigue syndrome is a heterogeneous syndrome with different pathophysiological anomalies manifesting with the same or similar symptoms. Many investigators have postulated that CFS is a condition of complex and multifactorial etiology. Indeed, some elements may predispose an individual to develop the syndrome, others may precipitate the illness, and still others perpetuate the disorder (20, 21).

1.4.1 Genetic Studies

To understand the relative importance of genetic and environmental influences on the development of a disorder, investigators often attempt to demonstrate its heritability and familiarity using family, adoption, or twin studies.

To our knowledge, no adoption studies of chronic fatigue syndrome have been conducted. One family history study and one twin study on CFS, and three twin studies of prolonged fatigue have been published.

In the family history study the results, based on subjects’ reports of illness in family members, suggested that within relatives of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome there were significantly higher rates of the same syndrome than in relatives of comparison subjects (22). Two investigations involving twins aged 50 years and older, from the volunteer Australian Twin Registry, found that fatigue of at least 1 month’s duration was moderately heritable (23, 24). The intrapair correlation (i.e., the correlation within twin pairs) for monozygotic twins was more than 2.5 times greater than the intrapair correlation for dizygotic pairs. Similarly, according to parental reports of fatigue, disabling prolonged fatigue lasting at least 1 month in childhood was familial among twins from a British twin registry (25). The intrapair correlations for monozygotic and dizygotic twins were 0.75 and 0.47, respectively. The model that best explained these results included additive genetic and nonshared environmental effects. In the only twin study of CFS, data from a chronic fatigue twin registry were used to examine evidence for a familial clustering and genetic predisposition to chronic fatigue in female twins (26). Concordance rates were higher between monozygotic than between dizygotic twins across three definitions of fatigue: fatigue of at least 6 months’ duration (42%

versus 30%), chronic fatigue unexplained by other medical conditions (39% versus 21%), and chronic fatigue syndrome–like illness identified on the basis of self-reported symptoms and medical and psychiatric exclusion criteria consistent with the CDC criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome (38% versus 11%). Biometrical genetic modelling suggested that additive genetic factors and common environmental effects each accounted for more than 40% of the variance in liability for chronic fatigue syndrome–like illness. These results should be interpreted cautiously because of the potential for differential ascertainment bias by zygosity in volunteer twin subjects. Nonetheless, the findings suggest a familial predisposition for chronic fatigue of varying intensities, with both genetic and environmental contributions.

Taken together, the family and twin data suggest that prolonged fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome–like illness may be familial and that genetic effects could be important. However, these results cannot be applied to broader population because of several factors, such as the restricted age range of the twins included in the studies, the use of brief measures of fatigue, and the classification of CFS on the basis of self-report only. As for other conditions such as cardiovascular disease (27) and major depression (28), large population based twin studies and family interview studies are necessary to further clarify the heritability of chronic fatigue syndrome.

1.4.2 CNS abnormalities

Several symptoms reported by chronic fatigue syndrome patients—including fatigue, headache, impaired concentration, attention and memory —suggest that the central nervous system (CNS) may be involved in the pathophysiology of the syndrome. Indeed, researchers have investigated a central link to chronic fatigue syndrome by means of structural and functional neuroimaging, cognitive testing, neuropeptide assays and autonomic assessment.

Neuroimaging studies. Neuroimaging research in CFS has primarily entailed magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). Some MRI studies have detected significantly more abnormalities in the subcortical white matter of chronic fatigue syndrome subjects, compared to healthy or trauma comparison subjects (28), while in other MRI studies the results for subjects with this syndrome did not differ from those for healthy or depressed subjects (29). In addition, MRI abnormalities have not been associated with neurocognitive performance (30). Other studies using SPECT scans have found that CFS patients have lower levels of regional cerebral blood flow throughout the brain, compared to healthy subjects (31). CNS perfusion abnormalities, typically hypoperfusion, also have been found more often on SPECT scans in these patients than in healthy or depressed comparison subjects, although no specific anatomic pattern has emerged and the effect of comorbid major depression is difficult to ascertain (31). Conversely, a recent rigorously controlled study detected no difference in cerebral blood flow between twins with chronic fatigue syndrome and their healthy co-twins (32). Overall, MRI and SPECT studies are generally consistent in demonstrating some abnormalities in chronic fatigue syndrome

patients. However, the functional significance and clinical utility of these findings remain uncertain and await further clarification (29).

Neuropsychological studies. Cognitive problems are some of the most disruptive and

disabling symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome (33). Although as many as 85% of patients complain of impairments in attention, concentration, and memory abilities (34), formal neuropsychological studies have not yielded consistent results. As a recent review of neuropsychological studies in chronic fatigue syndrome confirmed, the weight of the evidence suggests a modest but significant deficit in information processing, impaired working memory, and poor learning of information (35). These impairments could account for the poorer performance of subjects with chronic fatigue syndrome on complex attention and information-processing tasks. Coexisting psychological distress or a psychiatric disorder also may contribute to neurocognitive deficits. In general, however, persons with CFS appear to possess normal cognitive and global intellectual abilities (36, 37).

Neuroendocrine studies. A comprehensive review of neuroendocrine studies (38) reported

that abnormalities in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and serotonin pathways have been identified in chronic fatigue syndrome patients, suggesting an altered physiological response to stress (39). About one-third of patients have been shown to exhibit hypocortisolism, which appears to originate from a CNS source rather than a primary adrenal site (40). It is interesting to note that a recent study of a family with 32 members who had chronic fatigue syndrome reportedly identified a genetic mutation that affects the ability to produce globulin, a protein essential for the transport of cortisol in the blood (41).

In addition, studies have demonstrated abnormalities of CNS serotonin physiology in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (38). More specifically, administration of serotonin agonists causes a significant increase in serum prolactin levels in chronic fatigue syndrome patients,

relative to depressed and healthy comparison subjects, suggesting a CNS up-regulation of the serotonergic system. In contrast, patients with clinical depression demonstrate an opposite pattern of hypercortisolism and have a suppressed serotonin-mediated prolactin response (42, 43).

The studies of abnormalities in HPA function, hormonal stress responses, and serotonin neurotransmission in CFS patients have generated the most reproducible and robust findings reported to date.

Autonomic activity studies. Autonomic dysfunction, demonstrated by tilt-table testing and

manifested by hypotension with bradycardia (vasovagal reaction) or hypotension with tachycardia (vasodepressor reaction) upon vertical tilting, has been inconsistently implicated in the pathophysiology of chronic fatigue syndrome (44, 45). However, the precise nature and extent of autonomic system involvement are still undetermined. While anecdotal reports suggest that patients with symptoms indicative of neurally mediated hypotension often improve with fluid, salt, or fludrocortisone therapy (46), these improvements have not been demonstrated in large, well-controlled trials (47).

1.4.3 Immune System Abnormalities

Despite many studies of the immune system, only a few abnormalities have been consistently reported in CFS patients. These include increased expression of activation markers on the cell surface of T lymphocytes (48, 49), especially increased numbers of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells that bear certain antigenic markers (50), and deficiencies in natural killer cell function (51). Other findings include higher frequencies of various autoantibodies (52). Although collectively these results point to chronic low-level immune system activation, whether these abnormalities could have any relationship to the symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome remains unclear.

Some findings suggest that the degree of cellular immune activation could be associated with the severity of the physical symptoms, cognitive complaints, and perceived impairment (53). However, others have shown that clinical improvement was not associated with changes in lymphocyte subsets or activation (54). At this time, there are no immunological tests that are diagnostic for chronic fatigue syndrome.

1.4.4 Infectious agents

Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, group B coxsackie virus, human T-cell lymphotrophic virus II, hepatitis C, enteroviruses, and retroviruses, among others, have been proposed as etiological agents in chronic fatigue syndrome. Research is focusing on a potential marker for viral infection (55). Even so, there has been no consistent evidence to date that chronic fatigue syndrome results from a specific infection. In fact, some patients have no clinical or laboratory evidence of viral infection, and antiviral agents such as acyclovir or interferon α have not been beneficial (56). Therefore, it is improbable that a single infectious agent causes chronic fatigue syndrome. Rather, a heterogeneous group of infections may trigger or perpetuate the symptoms.

1.4.5 Sleep Disruption

CFS patients report more difficulty falling asleep, more interrupted sleep, and more daytime napping than healthy or chronically ill comparison subjects (57); however, polysomnography has yielded variable results. Some studies have revealed a characteristic ―alpha intrusion‖ during non-REM sleep and decrease in stage 4 sleep (58), while other studies have not (59). Thus, the results of polysomnography in chronic fatigue syndrome have not shown a consistent or diagnostic sleep disturbance. It is interesting to note that sleep disruption does not appear to correlate with fatigue severity (57) or degree of functional status impairment (58). Finally, some individuals with the symptoms of CFS who are assessed with polysomnography are discovered to have a sleep disorder such as sleep apnoeas (60). Such conditions are readily treatable and, if they are severe, exclude a diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome. Some investigators believe sleep disorders are the most commonly overlooked medical diagnoses among these patients (59), underscoring the importance of distinguishing fatigue from sleepiness.

1.4.6 Exercise study

Patients with chronic fatigue syndrome often complain of exercise intolerance. Many patients report that even minor efforts at physical activity lead to significant worsening of fatigue and other symptoms. In addition, some evidence suggests that many patients cope with their illness by resting or avoiding physical activity (61). A study that used objective actigraphic monitoring of physical activity patterns found that these subjects were overall less active than neighbourhood comparison subjects and took longer rest periods after activity peaks but that only about one-fourth were pervasively inactive (62). Thus, subjectively and possibly objectively, chronic fatigue syndrome patients have reduced physical activity, which could exacerbate or perpetuate fatigue.

Consequently, several studies have focused on CFS patients’ strength, level of conditioning, and physiological response to exercise, with mixed results.

A number of studies have provided evidence for a model in which physical deconditioning helps to maintain physical disability (63). These studies have demonstrated an increase in lactic acid in response to exercise (64) and reductions in capacity for oxygen transport (65), number of muscle mitochondria (66), and physical fitness and exercise capacity (67, 68). Other studies, however, have found normal or near-normal aerobic capacity (69) and muscle function (71) and postexertional lactate concentrations comparable to those in sedentary comparison subjects (70).

Given the same level of laboratory-documented physical activity, many chronic fatigue syndrome patients do not achieve their age-predicted maximal heart rate (72). They perceive the requisite effort and resulting fatigue as significantly higher (71), yet the degree of

measurable effort is significantly lower than in sedentary comparison subjects. These observations are more consistent with submaximal exertion than with physical deconditioning, possibly as a result of perceptual shifts in assessing bodily sensations. While these findings do not clarify the role of exercise capacity in CFS, they do suggest that the perception of increased effort, decreased activity, and the ensuing physical deconditioning can perpetuate the symptoms.

1.5

Clinical presentation

As the name indicates, fatigue is the hallmark of chronic fatigue syndrome. Patients often report excellent pre-illness physical fitness and energy (73) and an abrupt onset of fatigue, typically with a flu-like illness (74). After illness onset, however, patients indicate that physical exertion tends to exacerbate the fatigue. Many patients with CFS also often experience anorexia, nausea, drenching night sweats, dizziness, and intolerance to alcohol and other pharmaceuticals that affect the central nervous system (75). Finally, those with chronic fatigue syndrome have significant functional impairment. Nearly all patients note a decrease in social relationships in addition to other unwanted consequences of illness; about one-third are unable to work, and another one-third can only work part-time (11). Recent findings from community-based studies suggest that women, members of minority groups, and nonworking individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome may experience greater functional disability and symptom severity than men, whites, and working individuals (75). Fortunately, the diagnosis of CFS is not associated with increased mortality.

1.6

Overlapping Conditions

The symptoms of chronic fatigue, as well as chronic fatigue syndrome itself, often co-occur with other so-called functional illnesses such as fibromyalgia, multiple chemical sensitivities, irritable bowel syndrome, and temporomandibular joint disorder (76, 77).

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a chronic, non-articular rheumatic condition characterized by diffuse aching, pain or stiffness in the muscles or joints, and the presence of tenderness on examination at specific, predictable anatomic sites known as tender points (TPs) (78).

According to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), FM is defined by the following criteria: a) widespread pain of at least 3 months’ duration; b) tenderness of at least 11 of the 18 specific TPs on examination (79). FM has been related to a more severe disability in daily activities than other rheumatic conditions, besides having a negative impact on almost all aspects of the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (80, 81)

Chronic fatigue syndrome has been best studied in relation to fibromyalgia, a syndrome of characteristic tender points and chronic diffuse body pain (79). Despite the contrasting definitions of the two disorders, 20%–70% of patients with fibromyalgia also meet the criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome, and conversely, 35%–70% of those with chronic fatigue syndrome– like illnesses have concurrent fibromyalgia (82).

The overlap in case definition, reported symptoms, patient characteristics, and treatments for these functional somatic syndromes has led some researchers to suggest that these conditions are arbitrarily classified and should be considered as different manifestations of the same biomedical and psychosocial processes (83). Indeed, variable expressions of a common pathophysiology may explain the extensive overlap among these conditions (84). In addition,

research on the etiology of one of these conditions could help further understanding of other conditions. In the clinical setting, an appreciation of the coexistence of these disorders will help physicians and patients to consider additional treatment options and achieve more satisfactory overall care.

1.7

Psychiatric Comorbidity

Since a consistent physiological marker or physical finding for chronic fatigue syndrome has not been identified, some researchers have postulated that chronic fatigue syndrome is primarily a psychiatric disorder (85, 86). Several researchers believe that CFS and related disorders are manifestations of a psychiatric condition such as somatisation disorder (87), hypochondriasis (88), major depression, or atypical depression (89). Indeed, persons with chronic fatigue syndrome have an increased prevalence of current and lifetime mood disorders, primarily major depression, compared to other chronically ill subjects or healthy comparison subjects; 25% and 50%–75% of patients have a current or a lifetime history of major depression, respectively (90, 91). Generalized anxiety disorder and somatoform disorder also occur at a higher rate in these subjects than in the general population (90, 92-94). In most (91), but not all cases (95), the mood or anxiety disorder precedes the onset of chronic fatigue syndrome.

Of special note is the issue of how psychiatric prevalence in CFS is determined. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule (96), a highly structured interview designed to be administered by lay interviewers, is the instrument most commonly used to ascertain psychopathology in chronic fatigue syndrome. Thus, by rigidly attributing unexplained symptoms such as fatigue to psychiatric causes; it may overestimate the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in these patients. Several studies that have used the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (97), a semistructured interview that is administered by a trained clinician, have found that its use results in lower rates of psychiatric disorders in chronic fatigue syndrome (95, 98).

Somatisation disorder. Compared to a prevalence of 0.03% for somatisation disorder in the

community, the prevalence in CFS is high, with rates up to 28% (87, 91, 93, 94, 95, 99, 100). The evaluation of somatisation disorder, however, is strongly affected by the attributions made regarding the patient’s symptoms. Although the distinctions between physical and psychiatric illnesses often are not useful or accurate, their differentiation is in part the basis for a diagnosis of somatisation. Thus, whether the multiorgan and poorly understood typical symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome are considered to be medically or psychiatrically based influences the frequency of somatisation disorder (99). Indeed, when the symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome are considered to result from physical and not psychiatric causes, the rate of somatisation disorder is dramatically reduced (99). Thus, the diagnosis of somatisation disorder is, to a considerable degree, dependent on the examiner’s attributions of chronic fatigue syndrome symptoms (101) and is of limited use in understanding the syndrome itself.

Anxiety disorders. Anxiety disorders are common in the general population, with lifetime

rates of 3.5% and 5.1% for panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, respectively (102). Panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder are also common comorbid conditions among those with chronic fatigue syndrome, although the syndrome is differently characterized across studies. Lifetime prevalence rates for panic disorder in chronic fatigue syndrome are estimated to range from 17% to 25%, and rates for generalized anxiety disorder from 2% to 30% (92, 93, 103). This literature points to an overlap between CFS and anxiety. This overlap, along with some neurobiological similarities between chronic fatigue syndrome and generalized anxiety disorder— including decreased cerebral blood flow, sympathetic overactivity, and sleep abnormalities (104)—argues for further investigation of the relationship between the two disorders. The simple comorbidity of chronic fatigue syndrome and anxiety disorders,

however, does not suggest that chronic fatigue syndrome is a physical manifestation of an anxiety disorder.

Major depression. Persons with chronic fatigue syndrome have high rates of current and

lifetime major depression, which has been taken as evidence that chronic fatigue syndrome is an atypical manifestation of major depression. On the other hand, the high rates of depression in this syndrome could be a result of overlapping symptoms, an emotional response to disabling fatigue, viral or immune changes, or alterations in brain physiology (101). In fact, several lines of research have suggested that CFS and major depression are possibly distinct entities. First, while some symptoms of CFS are also symptoms of major depression, many others—such as sore throat, adenopathy, arthralgias, and postexertional fatigue—are not typical of psychiatric disorders.

Second, the pattern of symptoms differs significantly, with chronic fatigue syndrome patients generally not endorsing the classic depressive symptoms of anhedonia, guilt, and lack of motivation (90, 105) but more closely resembling patients with multiple sclerosis (105).

Third, severe major depression may be associated with a central up-regulation of the HPA axis, resulting in mild hypercortisolism (42, 43); conversely, in CFS, a central down-regulation is observed.

Fourth, the typical sleep abnormalities of major depression—reduced REM latency and increased REM density (63)—are not usually present in chronic fatigue syndrome.

Fifth, therapeutic doses of antidepressants have not been overwhelmingly effective in treating the symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome (106).

Sixth, many patients with chronic fatigue syndrome have no evidence of major depression at any point in their lives.

Finally, simple comorbidity of CFS and depression does not address their temporal relationship; depressive symptoms could precede or occur in response to the illness. In this regard, anxiety and depression are the most common emotional responses to a medical illness (107).

1.7.1 Cognitive Functioning

The cognitive complaints frequently reported by these patients are: poor concentration, decreased memory for recent events and poor word-finding ability (12). Studies have reported that 50±85% of CFS patients complains of cognitive problems and that these considerably contribute to their social and occupational dysfunction (9). Neuropsychological studies have attempted to describe cognitive functioning in CFS patients and to clarify the relation between cognitive complaints and cognitive performance. Given the nature of the cognitive complaints reported by these patients, neuropsychological studies have focused most frequently on attention and memory function.

In their 2001 review, Michiels and Cluydts (35) concluded there was ―no overwhelming evidence that fatigue is related to cognitive performance‖ in spite of the strong feeling of CFS patients that they perform poorly when fatigued. This conclusion was based on correlational analyses relating self-reported fatigue to cognitive function in CFS patients. Some studies show a negative relationship, whereas others show no relationship (108). A direct comparison of CFS patients with high self-reported mental fatigue to patients with lower mental fatigue demonstrated that patients with high mental fatigue performed worse on working memory and sustained attention tasks (109) Furthermore, high mental fatigue patients showed a pattern of decreased performance at the end of the sustained attention test, indicating cognitive fatigue. A possible reason for these strong results compared to past studies is the use of a mental fatigue measure rather than general fatigue, because these may represent very different physiologic systems. For example, studies of exercise and cognitive function in CFS show that

neither light exercise nor maximal exercise reduces cognitive performance in CFS patients (110, 111).

1.8

Differential diagnosis

1.8.1 Mood Disorders

Since the onset of neurasthenia symptoms may be involved in depressive syndrome is not possible, as pointed out by the criteria of ICD-10 diagnosis of neurasthenia when there is a specific mood disorder, this also applies to the definition of CFS. It can also be difficult to determine which disorder the patient is suffering for, especially in cases where the symptoms of depression are attenuated. Generally, in the depression outweigh depressed mood and loss of self-esteem, instead in chronic fatigue syndrome, in addition to weakness and various other somatic symptoms, are more easily observable dysphoria, restlessness and emotional instability. CFS seems to be close to atypical forms of depression, the attenuated depression and dysthymia, and it with these forms that differential diagnosis is most problematic (112).

1.8.2 Anxiety disorders

Da Costa (1871) described a syndrome, observed in the soldiers of the civil war, defining it "irritable heart‖. Although chest pain and palpitations were the most important symptoms of this syndrome, even fatigue was significant and became the most important aspect that Lewis (1917) introduced with the term of "stress syndrome". This syndrome was later incorporated into the concept of "neurocirculatory asthenia‖ along with cardiac neurasthenia. In panic disorder, fatigue is an important part of the clinical presentation (Wilkinson et al., 1989), especially when the post-critical phase lasts long after the panic attack, occupying the period between two crises. In addition, the wide range of physical symptoms in this disorder, often amplified by the constant state of alert in which these patients live, help to complicate the differential diagnosis. Other anxiety disorders may, in their course, occur with symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome and type mainly to problems of differential diagnosis of this morbid condition.

A persistent feeling of physical tiredness and exhaustion can prevail on the obsessive ideation and rituals component during certain phases of an obsessive-compulsive disorder where the nervous tension and inability to relax, caused by doubt or phobic issues, are not clearly expressed by the patient. We should not also forget that patients with anxiety disorders are often treated with tranquilizer drugs, frequently taken in high doses, which could contribute to the manifestation of the chronic fatigue syndrome.

1.8.3 Physical complaints

Hardly a physical disorder occurs without weakness of functional capacity and muscle tone, loss of energy and a tendency to tire more easily. Chronic fatigue syndrome can be considered as a form of psychophysical reaction against somatic diseases, which correspond to the ―acute exogenous reaction" described by Bonhoeffer (1912) and Bleuler et al. (5). If there is an acute physical disorder, the syndrome cannot be diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome as a distinct entity, but rather as a part of the primary physical disorder. The situation is different if CFS precedes the physical disorder as a sort of primordial or when it represents the sequela of long-term physical illness. The state of chronic fatigue syndrome that precedes the physical disorder is of major importance and is a landmark for early diagnosis. Some examples where CFS can be for a long time the only manifestation of somatic diseases are, for example, cancer, anemia, endocrine disorders, liver disease, deficiency syndromes, etc. An example of chronic fatigue syndrome related to endocrine changes is known as premenstrual syndrome and post-menopausal syndrome could be considered equally. Much clearer is the definition of CFS of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, in which the presence of an "active" physical disorder, or whose resolution is not is clearly documented, is an exclusion criterion. In the treatment of these syndromes, chronic fatigue syndrome should be directed to the primary disorder. The specific treatment of chronic fatigue component would be indicated when the condition lasts for a long time and especially in those cases in which remains long after the resolution of the primary disorder.

1.8.4 Chronic intoxication

The possibility of chronic intoxication should be considered as the excessive use of drugs or substances on luxuries such as tobacco, alcohol, caffeine and action of environmental toxins can lead to the appearance of symptoms similar to chronic fatigue syndrome. Almost all classes of drugs can cause symptoms of chronic fatigue and is of vital importance to investigate the treatment taken by the patient does not underestimate the possibility of any self-therapy. A further differential diagnosis must be placed between chronic fatigue syndrome and poisoning luxuries substances. For example, alcohol abuse (60 g / day) can cause functional changes of the central nervous system (CNS) and somatic disorders such as upset stomach, increased blood pressure, alertness and memory disorders, electroencephalographic changes, decreased concentration. Again the criteria for the definition of CFS are unclear under these conditions as a criterion for exclusion. Even the possibility of chronic poisoning from environmental toxins (heavy metals, solvents) should be considered in the diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome. As previously mentioned, the chronic fatigue syndrome appears to be, in fact, a type of nonspecific response of the CNS against various irritative stimuli (114).

1.8.5 Minimal brain damage

Another possible cause of chronic fatigue syndrome may be the so-called minimal brain damage. According to the most conservative estimates, one can say that about 10% of the population has suffered such damage. According to some authors it would be very high percentage of brain damage in the age child (115). Such damage would result in a reduced ability to concentrate, emotional instability, memory problems, loss of initiative and dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system. This type of psychopathological changes in minimum increase in typical fashion under stress. The diagnosis of CFS with minimal brain damage can be supported by an accurate survey of obstetric history and development of the subject considered together with evidence of the presence of symptoms appeared in early childhood. As mentioned in the discussion on the etiopathogenesis, the presence of neuro-anatomical abnormalities of the CNS in CFS has been shown in some studies with the use of MRI and SPECT. There is, however, agreement among different researchers and the significance of these observations remains unclear (116).

1.8.6 Life events

The chronic fatigue syndrome is associated with a reduced ability to tolerate stressful situations and stress factors should be considered every time you search for its cause. It is also true that the primary emotional stress, such concern a sense of fear or loss, generally does not result in chronic fatigue syndrome. In this type of stress reactions features seem to be anxiety, depression or psychosomatic disorders (117, 118). Chronic fatigue syndrome is instead described in relation to psychological stress as a work that causes abnormal nictemerale rhythm, or works that cause restrictions. The presence of a physical and / or psychological stress seems to be of great importance as a causative factor in the pathogenesis of CFS cases (119)

1.9

Clinical evaluation

To date, no single test has been sufficiently sensitive or specific enough to constitute a diagnostic test for chronic fatigue syndrome. The clinical evaluation of chronically fatigued patients is aimed at detecting underlying medical or psychiatric causes of fatigue, many of which are specified in the CDC case definition (8). To accomplish this, the National Institutes of Health has recommended that patients with chronic fatigue be evaluated with a battery of standard laboratory tests and a complete physical examination. Nonetheless, laboratory tests and physical examination are generally unremarkable in chronic fatigue syndrome (171 120). The most common abnormality is the presence of musculoskeletal tenderness at various sites that is consistent with fibromyalgia, which occurs in as many as 70% of chronic fatigue syndrome patients (82).

While most nonpsychotic psychiatric disorders are not exclusionary for the diagnosis of CFS, the assessment of comorbid psychiatric disorders is imperative in the adequate management of patients. Indeed, major depression is the most significant factor in the differential diagnosis. Other personality and psychosocial factors should also be considered. Although many chronic fatigue syndrome patients do not have current psychiatric disorders, maladaptive coping styles, or other psychopathology, assessing the presence of these issues as part of the routine clinical evaluation can be the first step in treating both CFS and other symptoms.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

A consecutive sample of 51 patients with a diagnosis of CFS was consecutively recruited at the Rheumatology outpatient Unit of the University of Pisa between June 2010 and January 2011. Eligible subjects included new and continuing patients, of at least 18 years of age, according to the classification criteria of Fukuda of 1994. We also recruited a consecutive sample of 27 patients with a diagnosis of FM in the same Unit, who met the 1990 American College of Rheumatology criteria for diagnosis of FM (79). Inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in table 1 and 2.

The Ethics Committee of the Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria Pisana approved all recruitment and assessment procedures. All patients interested in take part in the study underwent a psychiatric assessment after a routinely appointment. Eligible subjects provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study and having an opportunity to ask questions.

The diagnosis of CFS and FM was made according to the ACR criteria by a rheumatologist. The TP count was determined by the number of TPs that had a threshold of 4 kg/cm². Each positive TP had a pain score between 0 and 10. Psychiatric diagnoses were made through the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis I disorders (SCID-I/P) (129), administered by psychiatrists trained and certified in its use at the Dipartimento di Psichiatria, Neurobiologia, Farmacologia e Biotecnologie of the University of Pisa, Italy. The following questionnaires were also administered: the MOODS-SR lifetime version (130), the PAS-SR

lifetime version (131), the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) (132) and the Software CNS Vital Signs, tests for the assessment of neurocognitive tasks (133).

Socio-demographic data were collected using interviewer-administered questionnaires. A structured interview format was used to record sex, age, educational level, marital status, employment and duration of illness.

2.2 Statistical analysis

Pearson’s correlations were used to investigate correlations between clinical features of CFS (n=51) and FM (n=27) patients. T-test has been used to investigate the differences between MOODS-SR/PAS-SR factors scores in the two groups. All data are presented as mean ± SD. Data has been analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago 2006), version 14.0.

3. Results

Patients with CFS (n=51) are mainly females (28 vs 23; 54.9%) with a mean age of 37.8 ± 11.5 years; also patients with FM (n=27) are mainly females (24 vs 3; 88.8%), with a mean age of 43.0 ± 10.3 years.

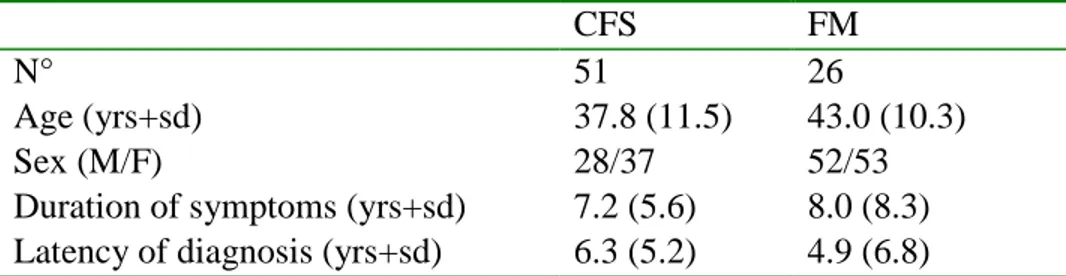

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample are reported in Table 3.

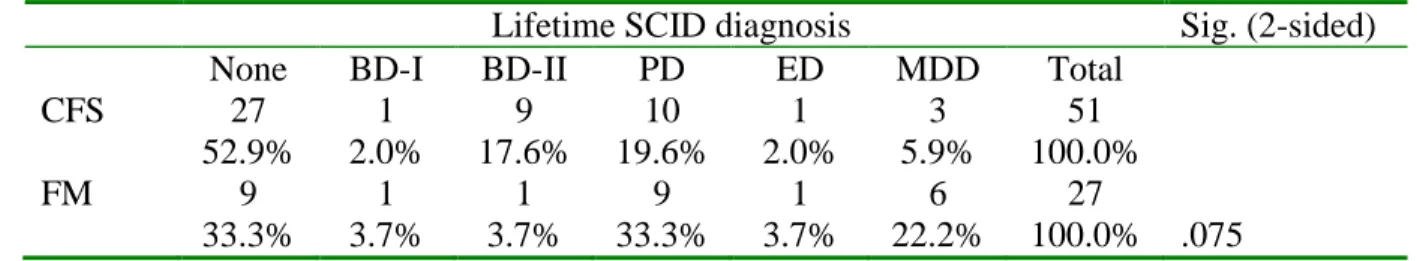

According to the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) criteria, current Axis I mental disorders were diagnosed in 5 (9.8%) CFS patients: 3 (5.9%) with Panic Disorder, 1 (2.0 %) with Major Depressive Disorder and 1 (2.0%) with Hypomania; moreover, in CFS group a lifetime Axis I mental disorder was diagnosed in 24 subjects: 1 with Bipolar Disorder type I (2.0 %), 9 with Bipolar Disorder type II (17.6 %), 10 (19.6%) with Panic Disorder, 3 (2.0 %) with Major Depressive Disorder and 1 (2.0%) with Eating Disorder. Even in the FM sample, a current Axis I mental disorder was diagnosed in 5 patients (18.5%): 3 (11.%) with Panic Disorder and 2 (7.4 %) with Major Depressive Disorder; moreover, in FM group a lifetime Axis I mental disorder was diagnosed in 18 subjects (66.7%): 1 with Bipolar Disorder type I (3.7 %), 1 with Bipolar Disorder type II (3.7 %), 9 (33.3%) with Panic Disorder, 6 (22.3 %) with Major Depressive Disorder and 1 (3.7%) with Eating Disorder. (Table 4 and 5)

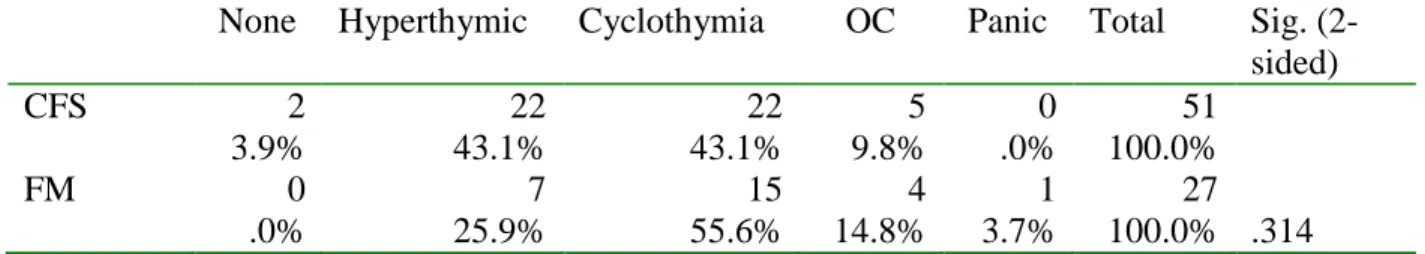

During the psychiatric evaluation psychiatric family history and personality traits were investigated. A psychiatric family history was recorded in 24 patients of CFS group (47.1%) and in 18 patients of FM group (66.7 %). (Table 6) In both samples emerged Hyperthimic/Cyclothimic temperamental traits; more specifically in CFS group there were 22 patients with Hyperthimic traits (43.1 %) and 22 with Cyclothimic traits (43.1 %), furthermore 5 (9.8%) patients had OCD traits. In FM group there were 7 patients with Hyperthimic traits

(25.9 %) and 15 with Cyclothimic traits (55.6 %), furthermore 4 (14.8%) patients had OCD traits and 1 (3.7 %) with PD traits. (Table 7)

The computerized test, known as CNS Vital Signs (CNSVS), returns a score for a composite neurocognitive score named CNSVS index. In the CFS group there were 3 subjects with an ―above‖ index (5.9 %), 26 with ―average‖ (51.0 %), 7 (13.7%) with ―low‖, 4 (7.8 %) with ―low average‖ and 9 (17.6%) with ―very low‖. FM sample was characterized by this distribution: 1 subject with an ―above‖ index (3.7%), 6 with ―average‖ (22.2 %), 1 (3.7%) with ―low‖, 7 (25.9 %) with ―low average‖ and 11 (40.7%) with ―very low‖. In both groups 3 persons (2 CFS, 1 FM) weren’t able to terminate the test). (Table 8)

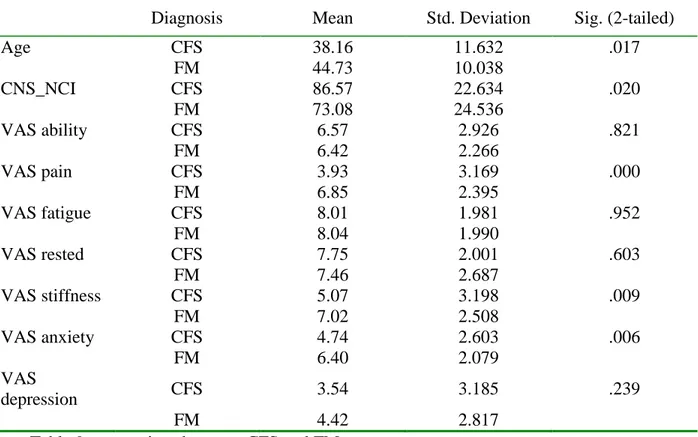

From the comparison of these data there was only one difference between the two groups with significant difference: CNSVS index is higher in CFS subjects (p= .020). Nearly statistically significant was a major presence of a lifetime psychiatric diagnosis in FM patients (p=.075). In table 9 are summarized the value of certain continuous variables like age, CNSVS index and VAS items. Medium age was higher in FM group (44.73 vs 38.16 yrs, p=.017), the medium CNSVS index was 86.57 in CFS patients vs 73.08 in FM patients (p=.020). Among VAS items there were three values with a significant difference between the two groups: medium VAS pain value was higher in FM group (6.85 vs 3.93, p=.000), medium VAS stiffness value was higher in FM group (7.02 vs 5.07, p=.009) and also medium VAS anxiety was higher in FM patients (6.40 vs 4.74, p=.006).

We also evaluated the presence of mood and panic-agoraphobic symptoms with MOOD-SR and PAS-SR.

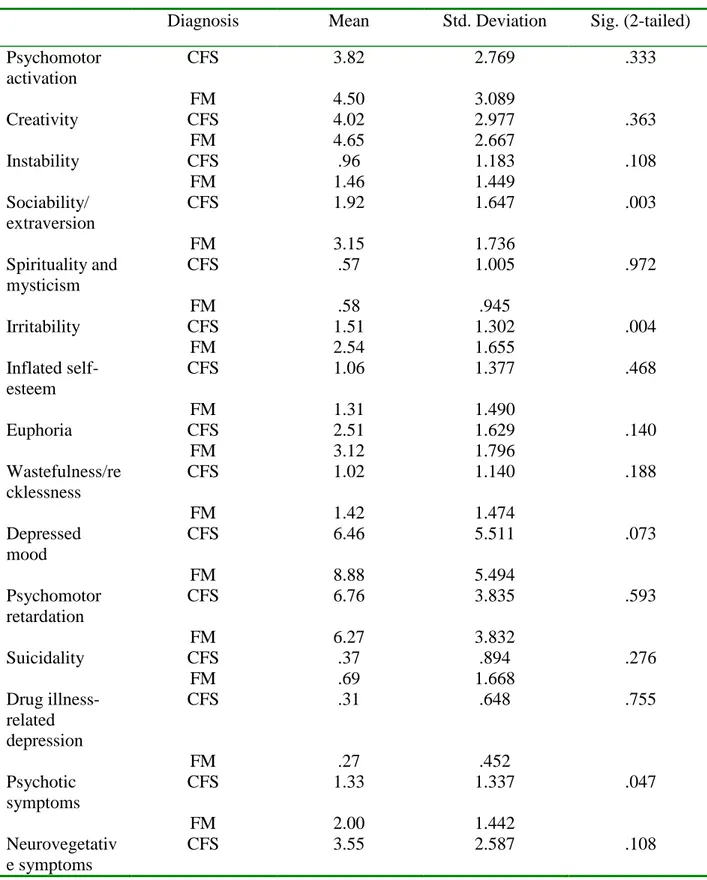

From the comparison between the two groups we have found a statistically significant difference in these factors of mood spectrum: Sociability/ extraversion factor was more present in FM group (3.15 vs 1.92, p=.003), Irritability factor was higher in FM patients (2,54

vs 1.51, p=.004), also the presence of psychotic symptoms was higher in FM subjects (2.00 vs 1.33, p=.047). Nearly statistically significant was a major presence of Depressed mood factor in FM patients (8.88 vs 6.46, p=.075). Table 10

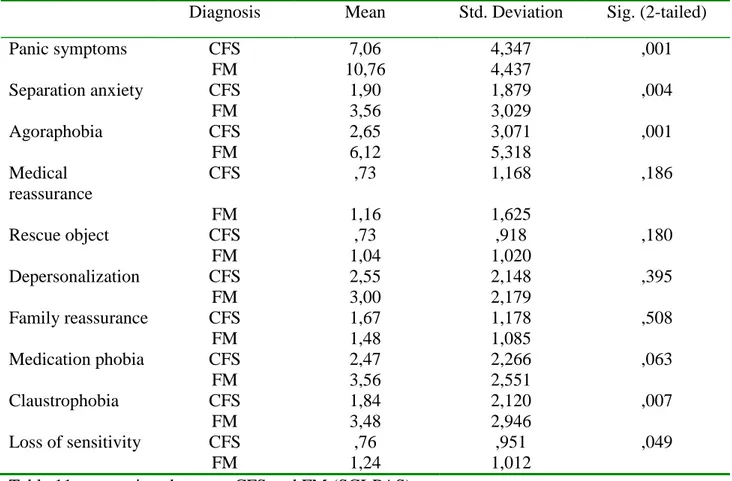

Moreover, from the comparison between the two groups we have found a statistically significant difference in these domains of panic-agoraphobic spectrum: Panic symptoms domain was more present in FM group (10.76 vs 7.06, p=.001), Separation anxiety domain was higher in FM patients (3.56 vs 1.90, p=.004), agoraphobia domain was higher in FM sample (6.12 vs 2.65, p=.001), also the presence of Claustrophobia domain was higher in FM subjects (3.48 vs 1.84, p=.007). Nearly statistically significant was a major presence of Medication phobia domain in FM patients (3.56 vs 2.47, p=.063). Table 11

4. Discussion

In our sample clinical and demographic characteristics are consistent with the literature, such as the prevalence of female gender and mean age (14, 15).

Several researchers have found a high psychiatric comorbidity in CFS such as somatisation disorder (87), hypochondriasis (88), major depression or atypical depression (89). Indeed, persons with chronic fatigue syndrome have an increased prevalence of current and lifetime mood disorders, primarily major depression, compared to other chronically ill subjects or healthy comparison subjects; 25% and 50%–75% of patients have a current or a lifetime history of major depression, respectively (90, 91). Generalized anxiety disorder and somatoform disorder also occur at a higher rate in chronic fatigue syndrome subjects than in the general population (90, 92-94). Panic disorder is also a common comorbid condition among those with chronic fatigue syndrome, although chronic fatigue syndrome is characterized differently across studies. Lifetime prevalence rates for panic disorder in chronic fatigue syndrome are estimated to range from 17% to 25% (103). Our findings are partially according to these data with a presence of a current psychiatric diagnosis (with SCID) by approximately 10% in CFS patients (3 with Panic Disorder and 2 with Mood Disorder). Instead, lifetime psychiatric diagnosis (with SCID) is closer to literature with a prevalence of 47.1%. Particularly, in our sample there are more bipolar patients than unipolar patients (10 vs 3), 10 patients (19.6%) with Panic Disorder and no patients with somatisation disorder or hypochondriasis.

Although the data thus far suggest that chronic fatigue syndrome and psychiatric disorders are distinct, the relationship between chronic fatigue syndrome and psychiatric diagnoses remains an area of controversy. Historically, this issue may have been resolved by distinguishing

between ―medical or physical‖ and ―psychiatric‖ conditions. (121). Nowadays, the success of pharmacological agents in the treatment of psychiatric disorders has blurred this distinction, perhaps suggesting that there is no distinction to be made (122). Moreover, a multiaxial model of diagnosis has been proposed that would take into account the biological, psychological, and social factors involved in any particular diagnosis and the associated impairment (123). Clinically, however, since many patients with chronic fatigue syndrome suffer from major depression and anxiety disorders, efforts should be made to assess and treat these conditions as well as the symptoms of the syndrome.

There are few studies that considers family history for psychiatric disorders in CFS patients; (art family) in a paper of Endicott (124) is reported a pattern of psychiatric disease similar to our sample with a high presence of Mood Disorder in family history. This topic gives more strength to the importance of psychiatric burden in CFS.

There is a growing interest in the temperamental and premorbid characteristics as seen in a recent paper of Fukuda et al. (125). Indeed, clinical psychologists, consulting physicians, and scientific researchers generally characterize patients with CFS as perfectionist, conscientious, hardworking, somewhat neurotic, introverted individuals with high personal standards, a great desire to be socially accepted, and a history of continuously pushing themselves pass their limits (126). Objective assessments of CFS patients have shown high levels of personality disorders (127), and it is known that personality plays a role in the development, perpetuation, and initiation of CFS (126, 128). In our study the premorbid characteristics weren’t evaluated with a specific questionnaire, but we recorded them during the psychiatric evaluation. Even in our sample the presence of premorbid characteristics was elevated; indeed, hyperthimic or cyclothimic traits were found in more than 86% of the patients, and near 10% of subjects

shown OCD traits. These findings are similar to those reported in the literature, with a higher prevalence of temperamental traits.

We also evaluated the cognitive performance with a computerized test (CNS Vital Signs) to measure objectively the complaints of the patients: poor concentration, decreased memory for recent events and poor word-finding ability up to 50-85% of CFS patients (12). Our data partially confirm these findings, because approximately 60% of patients had an ―average‖ or ―above‖ report in the test. This data suggest that there is a difference between the subjective feeling of the patient and the result of the computerized test, probably linked to mood or anxiety symptoms.

Finally, as seen in the results, findings emerged from the comparison between CFS and FM groups using the MOOD-SR and PAS-SR shown a higher burden of psychopathology in the second one. More specifically, FM patients seem to have mood factors that indicate higher instability, such as Sociability/Extroversion and Irritability. Results of analysis of PAS-SR show us a higher presence of panic-agoraphobic spectrum in FM sample (up to 6/10 positive domains). These findings are not simply comparable to the literature, because MOOD-SR and PAS-SR are not used in concerning CFS trials. Nevertheless we used those questionnaires, often administered in psychiatric studies, because they represent a useful support to identify subthreshold symptoms of mood and panic-agoraphobic spectrum.

5. Tables

Diagnosis of CFS according to the classification criteria of Fukuda of 1994 (3); Diagnosis of FM according to the classification criteria of ACR of 1990; Aged between 18 and 65;

Patients of both sexes;

Acceptance of the protocol and signed informed consent. Table 1: Inclusion Criteria

Patients aged> 65 and <18;

Status of alleged or established pregnancy and lactation; Lack of consent by the patient;

Presence of active rheumatic diseases, infectious and / or unstable medical condition; Withdrawal of informed consent by the patient.

CFS FM

N° 51 26

Age (yrs+sd) 37.8 (11.5) 43.0 (10.3)

Sex (M/F) 28/37 52/53

Duration of symptoms (yrs+sd) 7.2 (5.6) 8.0 (8.3) Latency of diagnosis (yrs+sd) 6.3 (5.2) 4.9 (6.8) Table 3: demographic and clinical characteristics

Current SCID diagnoses Sig. (2-sided)

None PD MDD Hypomania Total

CFS 46 3 1 1 51

90.2% 5.9% 2.0% 2.0% 100.0%

FM 22 3 2 0 27

81.5% 11.1% 7.4% .0% 100.0% .445

Lifetime SCID diagnosis Sig. (2-sided)

None BD-I BD-II PD ED MDD Total

CFS 27 1 9 10 1 3 51

52.9% 2.0% 17.6% 19.6% 2.0% 5.9% 100.0%

FM 9 1 1 9 1 6 27

33.3% 3.7% 3.7% 33.3% 3.7% 22.2% 100.0% .075 Table 5: comparison between CFS and FM (lifetime psychiatric diagnosis)

None Mood Anxiety Substances Total Sig. (2-sided)

CFS 26 20 2 2 51

52.0% 40.0% 4.0% 4.0% 100.0%

FM 9 12 3 3 27

33.3% 44.4% 11.1% 11.1% 100.0% .245

None Hyperthymic Cyclothymia OC Panic Total Sig. (2-sided) CFS 2 22 22 5 0 51 3.9% 43.1% 43.1% 9.8% .0% 100.0% FM 0 7 15 4 1 27 .0% 25.9% 55.6% 14.8% 3.7% 100.0% .314

Table 7: comparison between CFS and FM (personality traits)

N/A Above Average Low Low average Very low total Sig. (2-sided) CFS 2 3 26 7 4 9 51 3.9% 5.9% 51.0% 13.7% 7.8% 17.6% 100.0% FM 1 1 6 1 7 11 27 3.7% 3.7% 22.2% 3.7% 25.9% 40.7% 100.0% .020 Table 8: comparison between CFS and FM (CNS vital signs index)

Diagnosis Mean Std. Deviation Sig. (2-tailed) Age CFS 38.16 11.632 .017 FM 44.73 10.038 CNS_NCI CFS 86.57 22.634 .020 FM 73.08 24.536 VAS ability CFS 6.57 2.926 .821 FM 6.42 2.266 VAS pain CFS 3.93 3.169 .000 FM 6.85 2.395 VAS fatigue CFS 8.01 1.981 .952 FM 8.04 1.990 VAS rested CFS 7.75 2.001 .603 FM 7.46 2.687 VAS stiffness CFS 5.07 3.198 .009 FM 7.02 2.508 VAS anxiety CFS 4.74 2.603 .006 FM 6.40 2.079 VAS depression CFS 3.54 3.185 .239 FM 4.42 2.817

Diagnosis Mean Std. Deviation Sig. (2-tailed) Psychomotor activation CFS 3.82 2.769 .333 FM 4.50 3.089 Creativity CFS 4.02 2.977 .363 FM 4.65 2.667 Instability CFS .96 1.183 .108 FM 1.46 1.449 Sociability/ extraversion CFS 1.92 1.647 .003 FM 3.15 1.736 Spirituality and mysticism CFS .57 1.005 .972 FM .58 .945 Irritability CFS 1.51 1.302 .004 FM 2.54 1.655 Inflated self-esteem CFS 1.06 1.377 .468 FM 1.31 1.490 Euphoria CFS 2.51 1.629 .140 FM 3.12 1.796 Wastefulness/re cklessness CFS 1.02 1.140 .188 FM 1.42 1.474 Depressed mood CFS 6.46 5.511 .073 FM 8.88 5.494 Psychomotor retardation CFS 6.76 3.835 .593 FM 6.27 3.832 Suicidality CFS .37 .894 .276 FM .69 1.668 Drug illness-related depression CFS .31 .648 .755 FM .27 .452 Psychotic symptoms CFS 1.33 1.337 .047 FM 2.00 1.442 Neurovegetativ e symptoms CFS 3.55 2.587 .108

Diagnosis Mean Std. Deviation Sig. (2-tailed) Panic symptoms CFS 7,06 4,347 ,001 FM 10,76 4,437 Separation anxiety CFS 1,90 1,879 ,004 FM 3,56 3,029 Agoraphobia CFS 2,65 3,071 ,001 FM 6,12 5,318 Medical reassurance CFS ,73 1,168 ,186 FM 1,16 1,625 Rescue object CFS ,73 ,918 ,180 FM 1,04 1,020 Depersonalization CFS 2,55 2,148 ,395 FM 3,00 2,179 Family reassurance CFS 1,67 1,178 ,508 FM 1,48 1,085 Medication phobia CFS 2,47 2,266 ,063 FM 3,56 2,551 Claustrophobia CFS 1,84 2,120 ,007 FM 3,48 2,946 Loss of sensitivity CFS ,76 ,951 ,049 FM 1,24 1,012

References

1. Pawlikowska T, Chalder T, Hirsch SR et al.: Population based study of fatigue and psychological distress. Br Med J 1994; 308:763–766

2. Bates D, Schmitt W, Buchwald D et al.: Prevalence of fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome in a primary care practice. Arch Intern Med 1993; 153:2759–2765

3. Cathebras PJ, Robbins JM, Kirmayer LJ et al.: Fatigue in primary care: prevalence, psychiatric comorbidity, illness behavior, and outcome. J Gen Intern Med 1992; 7:276–286

4. McDonald E, David AS, Pelosi AJ et al.: Chronic fatigue in primary care attenders. Psychol Med 1993; 23:987–998

5. Bleuler M, Willi J, Buhler HR: Akute Psychische Begleiterscheinungen Korperlicher

Krankheiten. Thieme, Stuttgart, 1966.

6. Kielholz P: Klinik Differentialdiagnostik und Therapie der Depressiven Zustandsbilder. Acta Psychosom. (Docum Geigy) 2, 1959.

7. Lecrubier Y, Puech AJ, Boyer P: The Contribution of Neuropharmachology to the

Understanding of Ill-Defined Psychological Disorders. In: Sartorius N., Goldberg D. et al.

(Eds.): Psychological Disorder in General Medical Settings. Hogrefe & Huber Publishers, Toronto- Lewiston, NY- Bern-Gottingen-Stuttgart, 1990.

8. Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I et al.: The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Ann Intern Med 1994; 121:953–959

9. Briggs NC, Levine PH: A comparative review of systemic and neurological symptomatology in 12 outbreaks collectively described as chronic fatigue syndrome, epidemic neuromyasthenia, and myalgic encephalomyelitis. Clin Infect Dis 1994; 18(suppl 1):S32–S42

10. Goshorn RK: Chronic fatigue syndrome: a review for clinicians. Semin Neurol 1998; 18:237–242

11. Bombardier CH, Buchwald D: Chronic fatigue, chronic fatigue syndrome, and fibromyalgia: disability and health-care use. Med Care 1996; 34:924–930

12. Buchwald D, Pearlman T, Umali J et al.: Functional status in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, other fatiguing illnesses, and healthy individuals. Am J Med 1996 101:364–370

13. Richman JA, Flaherty JA, Rospenda KM: Chronic fatigue syndrome: have flawed assumptions been derived from treatment-based studies? Am J Public Health 1994; 84:282– 284

14. Jason LA, Richman JA, Rademaker AW et al.: A community based study of chronic fatigue syndrome. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:2129–2137

15. Steele L, Dobbins JG, Fukuda K et al.: The epidemiology of chronic fatigue in San Francisco. Am J Med 1998; 105:83S–90S

16. Fukuda K, Dobbins JG, Wilson LJ et al.: An epidemiologic study of fatigue with relevance for the chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychiatr Res 1997; 31:19–29

17. Reyes M, Gary HE Jr, Dobbins JG et al.: Surveillance for chronic fatigue syndrome—four US cities, September 1989 through August 1993. MMWR Surveill Summ 1997; 46:1–13

18. Buchwald D, Umali P, Umali J et al.: Chronic fatigue and the chronic fatigue syndrome in a Pacific Northwest health care system. Ann Intern Med 1995; 123:81–88

19. Jordan KM, Landis DA, Downey MC et al.: Chronic fatigue syndrome in children and adolescents: a review. J Adolesc Health 1998; 22:4–18

20. Komaroff AL, Buchwald DS: Chronic fatigue syndrome: an update. Annu Rev Med 1998; 49:1–13

21. White PD: The relationship between infection and fatigue. J Psychosom Res 1997; 43:345–350

22. Walsh CM, Zainal NZ, Middleton SJ et al.: A family history study of chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychiatr Genet 2001; 11: 123–128

23. Hickie I, Bennett B, Lloyd A et al.: Complex genetic and environmental relationships between psychological distress, fatigue and immune functioning: a twin study. Psychol Med 1999; 29:269–277

24. Hickie I, Kirk K, Martin N: Unique genetic and environmental determinants of prolonged fatigue: a twin study. Psychol Med 1999; 29:259–268

25. Farmer A, Scourfield J, Martin N et al.: Is disabling fatigue in childhood influenced by genes? Psychol Med 1999; 29:279–282

26. Buchwald D, Herrell R, Ashton S et al.: A twin study of chronic fatigue. Psychosom Med 2001; 63:936–943