Academic Year

2016-2017

International PH.D. in Management:

Innovation, Sustainability and Healthcare Curriculum: Change and Complexity Management Disaster Management

“Consumers’ engagement as opportunity for

crisis and disaster risk management:

A tourism-oriented analysis”

Candidate: Giuseppe Aliperti

Tutor: Prof. Francesco Rizzi

Supervisor: Prof. Marco Frey

3

“Consumers’ engagement as opportunity for crisis and disaster risk

management: A tourism-oriented analysis”

A thesis presented

By

Giuseppe Aliperti

to

The Class of Social Sciences

for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

in the subject of

International PhD in Management:

Innovation, Sustainability and Healthcare

Tutor: Prof. Francesco Rizzi

Supervisor: Prof. Marco Frey

Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna

A.Y. 2016-2017

4

Table of contents

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ……….. § CHAPTER 1 – Introduction ……….. § 1.1. Background ………. § 1.2. Research design ……… § 1.2.1. Crisis and disaster: definitions ……….. § 1.2.2. Engaging consumers to better manage disaster ……….. § 1.2.3. Engaging consumers to better manage crisis ………. § 1.2.4. Snapshot of the Ph.D. papers ………. § 1.3. References ……… § CHAPTER 2 – Crisis and disaster within the tourism industry: Towards the definition of an interdisciplinary research agenda………. § 2.1. Introduction & theoretical Background……… § 2.2. Method ……….………. § 2.3. Results ……….……….. § 2.3.1. Disaster vs crisis in the disaster risk literature………... § 2.3.2. Review of tourism-oriented literature on disaster and crisis: key trends……… § 2.3.3. Crisis and disaster within the tourism literature……… § 2.4. Discussion……….………..………..…….. § 2.5. Conclusions………..… § 2.6. References ……… § CHAPTER 3 – Cause-related Marketing and disaster management: Opportunities from tourism-related initiatives ……….. § 3.1. Introduction ……… § 3.2. Theoretical Background ……… § 3.3. Method ……….. § 3.4. Results ………. § 3.4.1. Evidence from the literature on CrM ………..…… § 3.4.2. CrM and Tourism ………. § 3.4.3. CrM and Disaster Management ……… § 3.4.4. Disaster-related CrM initiatives among tourism industry ……….. § 3.5. Discussion & Conclusions ……….. § 4.7. References ……… § CHAPTER 4 – Cause-related Marketing and disaster management: A comparative analysis of prevention- and recovery-related campaigns ………. § 4.1. Introduction ……… § 4.2. Theoretical Background ………. § 4.3. Method ……….. § 4.3.1. The CrM campaigns ……….. 7 10 10 11 11 12 12 13 17 20 20 22 23 23 25 26 28 34 34 47 47 48 49 49 49 51 52 52 56 57 65 65 67 71 715

§ 4.3.2. Creation of the fictitious campaigns ………. § 4.3.3. The questionnaire ……….. § 4.3.4. The measure of the items ………. § 4.3.5. The sample ……….. § 4.4. Results ………..………..……….. § 4.4.1 Data analysis ………..………. § 4.4.2. Hypotheses tests ………..……….. § 4.5. Discussion ……….……… § 4.6. Conclusions ………..……….. § 4.7. References ……….………..………

§ CHAPTER 5 – How risk and uncertainty perceptions affect consumption? Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to analyse seafood consumption after the Fukushima accident.……… § 5.1. Introduction ……… § 5.2 Theoretical background ……… § 5.2.1. Step 1: The application of the TPB ………..……….. § 5.2.2. Step 2: Focus on the attitude ……….……….. § 5.3. Method ……….. § 5.3.1. The questionnaire ……….. § 5.3.2. The sample ……….………. § 5.3.3. The measure of the items………..……… § 5.4. Results ………. § 5.4.1. Data analysis ……….……… § 5.4.2. Hypotheses tests ………..…….. § 5.5. Discussion ……….……… § 5.6. Conclusions ……….……… § 5.7. References ……… § CHAPTER 6 – Conclusions ……… § Acknowledgements ………. 73 74 74 75 76 76 78 80 82 82 94 94 96 97 99 102 102 102 103 110 110 111 115 118 119 125 128

7

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This Doctoral Thesis combines four papers with the aim to investigate the role of consumers’ engagement in order to better manage crises and disasters. The study has been developed from a tourism-oriented perspective.

The literature suggests that the tourism industry is highly susceptible and vulnerable to crises and disasters (Pforr & Hosie, 2008) and tourists are particularly vulnerable because they are mobile, difficult to account for and not easy to reach with relevant information (Becken and Hughey, 2013; Bird, Gisladottir, & Dominey-Howes, 2010). However, crises and disasters may affect different stakeholders and may be described from different perspectives when referring to the tourism industry.

Our study provides some insight in order to shed the light on this complex system and to better understand the concepts of crisis and disasters within the tourism-oriented literature. In addition, this study explains how consumer’s engagement process may reduce the negative effects generated by crises and disasters focusing on the firm perspective and highlighting the consequent positive effects generated to hazard-exposed communities. The document offers a marketing-oriented perspective.

Chapter One introduces the background of the study through identifying the importance of engaging consumers in order to manage crises and disasters. In addition, this chapter outlines the research design and includes a “snapshot” of the papers included in the Doctoral Thesis to facilitate the reading of the document.

Chapter Two aims at explaining the concepts of crisis and disaster within the tourism-related literature. This chapter results to be useful to the reader as it helps to clarify some basic concepts that need to be addressed in order to facilitate crisis and disaster risk management. The article included in this section has been developed in collaboration with the United Nations University (Bonn, Germany).

Chapter Three and Four analyse the opportunities that consumers’ engagement may offer in order to better manage disasters. The studies focus on disasters generated by natural hazards. The investigations have been developed following a tourism firm perspective.

In particular, Chapter Three aims at introducing the opportunities offered by the Cause-related Marketing to the tourism firms in order to engage tourists, collect funds, and therefore increase the resilience of the communities.

On the other hand, Chapter Four offers a different investigation of disaster-oriented Cause-related Marketing campaigns. We propose an analysis of two campaigns, promoted by a fictitious hotel chain and referring to a real cause. Findings show that different disaster-related causes may generate different results, depending on the stage of disaster management they focus on (prevention Vs recovery). The study has been developed in order to contribute to generating more effective Cause-related Marketing campaigns able to collect higher amounts of money to be invested to increase the resilience of the hazard-exposed destinations.

8

Chapter Five analyses the opportunities that consumer engagement may offer in order to better manage a crisis. In particular, the investigation refers to the crisis of seafood consumption in Japan after the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant (FDNPP) accident triggered by the Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami (GEJET) on 11 March 2011. The study has been developed following the Japanese fisheries and the Japanese Government perspective. The article investigates two different categories of consumers: tourists and residents. The study has been developed in collaboration with the Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University (Kyoto, Japan).

10

§ CHAPTER 1 – Introduction

§ 1.1. Background

During the last decade, an extensive use of the term ‘‘engagement’’ has been realized in several and different academic disciplines as well as sociology, political science, psychology, and organizational behaviour (Brodie et al., 2011). Especially after 2005, this concept has been increasingly used in the academic marketing literature through introducing terms as well as ‘‘consumer engagement,’’ ‘‘customer engagement,’’ and/or ‘‘brand engagement’’ (Brodie et al., 2013). The word engagement tends to substitute more traditional terms as well as “involvement” or “participation” (Brodie et al., 2011; Schau et al., 2009). Marketing managers may find several benefits from customers’ engaging process. Several studies provided insights regarding the positive consequences generated by the consumers’ engagement (Brodie et al., 2013) linking them to the concepts of trust (Casalo et al., 2007; Hollebeek, 2011), satisfaction (Bowden, 2009a), commitment, emotional connection/attachment (Chan and Li, 2010), empowerment, consumer value (Gruen et al., 2006; Schau et al., 2009), and loyalty (Bowden, 2009a, b).

Despite the growing popularity of the term “engagement” and the rising number of studies that aim to analyse the consequences generated by this process, relatively few authors have defined this concept in the academic marketing literature (Brodie et al., 2013; Brodie et al., 2011).

Brodie et al. (2011; 2013) provide a list of elements that are able to describe the process of consumers’ engagement from a marketing perspective. This perspective has been developed taking into consideration previous studies focused on customer engagement (Patterson et al., 2006), online brand engagement (Mollen and Wilson, 2010), customer engagement process (Bowden, 2009a), customer engagement behaviour (Van Doorn et al., 2010), customer brand engagement (Hollebeek, 2011), engagement behaviour (Pham and Avnet, 2009), and on a broader vision of the concept of engagement (Higgins and Scholer, 2009). In particular, the process results to be composed by 5 steps.

The first step refers to the necessity to undertake an interactive experience between the firm, the consumers, and other stakeholders, able to support a focal engagement object. The second point refers to the fact that consumer engagement is part of a broader dynamic process able to co-create value and therefore is different from “participation” and “involvement”. The third point identifies the importance of consumer engagement in the process of relational exchange, where other concepts (e.g. participation, involvement) act as engagement antecedents and/or consequences. The fourth point recognizes the multidimensional – cognitive, emotional, and behavioural – value of the concept of consumer engagement. The five and last point underlines that the consumer engagement represents a highly context- and timely-dependent motivational state.

From a theoretical point of view, the concept of engagement grounds on the broader relationship marketing theory (Ashley et al., 2011). In particular, the engagement has been identified as a “transcending” view of relationships (Vargo, 2009) that recognizes that consumer behaviour is formed by customers' and/or other stakeholders' interactive experiences (Brodie et al., 2013). These

11

interactive consumer experiences co-created with other stakeholders are defined as the result of the act of “engaging” (Lusch and Vargo, 2010). These interactions take place in complex environments (Brodie et al., 2013), as well as those characterized by the presence of crisis and/or disaster. Both crisis and disaster are phenomena characterized by chaos and complexity (Scott, Laws, and Prideaux, 2008; Prideaux, Laws and Faulkner, 2003; Faulkner, 2001; Peat, 1991, Gleick, 1987) and they maintain these characteristics when affecting the tourism industry dynamics (Faulkner and Russel, 1997). At the same time, the tourism industry is itself characterized by chaos (Speakman and Sharpley, 2012) and complexity (Speakman, 2017) due to the predominance of small- and medium-sized organizations and due to its constant interaction with different socio/economic systems (Hall, 2010; de Sausmarez, 2007).

This Doctoral Thesis aims focuses on the opportunities that consumers’ engagement is able to provide to firms in order to better manage crisis and disaster. The tourism industry has been used as the setting to study this relationship. The consumers’ engagement has been mainly evaluated focusing on the behavioural dimension, which is on the three dimensions (cognitive, emotional, and/or behavioural) (Brodie et al., 2013; Brodie et al., 2011) able to characterize it.

After providing an in-depth explanation of the concepts of crisis and disaster within the tourism-related literature, we adopted the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991) to investigate consumer’s attitude, perceived behavioural control, subjective norms, and intention to perform the actions that have been analysed in the proposed studies. According to the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1991), people are likely to exhibit a particular type of behaviour (intention) if they believe it will lead to an outcome they value (attitude), if those they consider important will value and approve the behaviour (subjective norms) and if they have the necessary resources, abilities, and opportunities to perform such behaviour (perceived behavioural control) (Lam & Hsu, 2006; Quintal, Lee, and Soutar, 2010).

The following paragraph describes the layout of the thesis and the content of the papers included in the Doctoral Thesis.

§ 1.2. Research design

§ 1.2.1. Crisis and disaster: definitions

The article “Crisis and disaster within the tourism industry: Towards the definition of an interdisciplinary research agenda” aims at introducing to the reader the concepts of crisis and disaster. No clear and commonly accepted definitions of crisis or disaster are currently available. Even the UNISDR Disaster Risk Reduction terminology is not able to clearly state the difference between the two concepts. Tourism-related literature seems to be able to contribute to fill this gap through the identification of a specific research path. We adopted a systematic approach to review the crisis and disaster risk management oriented literature in the field of the tourism-industry. A total of 111 relevant publications were analysed. The study identifies a research agenda that suggests developing a constant interdisciplinary dialogue and to more in-depth focusing on the resource management issue in order to clearly define disaster and crisis. Managerial implication

12

refers to the current funds management system of the European Union Solidarity Fund (EUSF) Regulation that requires clear definitions of disaster and crisis in order to allocate funds and resources in presence of shock event occurrence.

§ 1.2.2. Engaging consumers to better manage disaster

The article “Cause-related Marketing and disaster management: opportunities from tourism-related initiatives” focuses on the link between consumers’ engagement and disaster management. An increasing number of firms (including from tourism industry) is currently promoting Cause-related Marketing (CrM) campaigns, often based on disaster-Cause-related causes. Despite the existence of this phenomenon, academic research in the field of tourism is still limited. We offer a review of the CrM studies with the aim to identify useful insights to be applied to disaster- and tourism- related campaigns. The additional analysis of already existing disaster-related CrM campaigns promoted by tourism firms contributed at identifying the necessity to develop a new and tourism-oriented research agenda.

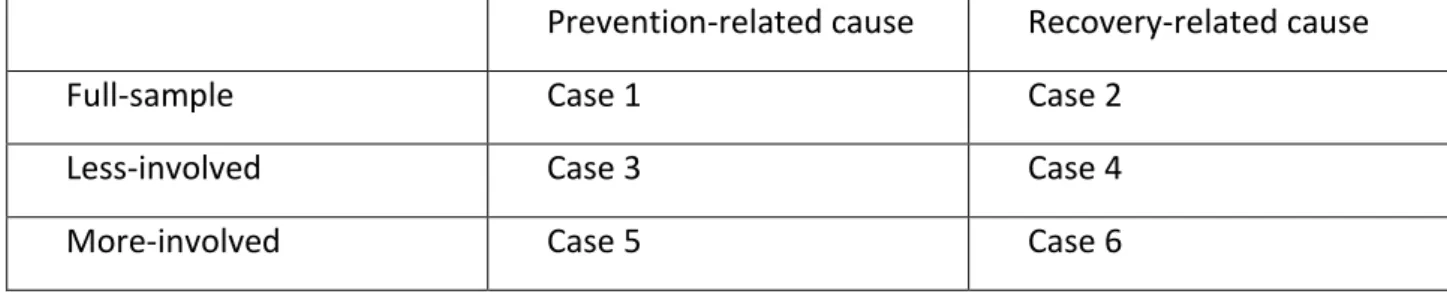

The article “Cause-related marketing and disaster management: A comparative analysis of prevention- and recovery-related campaigns” aims at investigating the opportunities provided by the adoption of CrM campaign within the tourism industry. Academic research in this field mainly focuses on two areas: the general response of consumers to CRM and the comparative effects of different types of CrM. Ours is a comparative study. We propose an analysis of two campaigns, supported by a fictitious hotel chain and referring to a real cause. The study focuses on the consumer behaviour of European tourists, who are part of Generation Y and who have a Facebook account. Participants in the survey were contacted between May and September 2016. The snowball sampling technique was used. A total of 647 questionnaires were collected. Findings show that different disaster-related causes may generate different results, depending on the stage of disaster management they focus on. Prevention-related campaigns appear to be more effective than recovery-related campaigns when focusing on the total number of respondents and are able to influence the perceived corporate social responsibility (CSR). The intention to participate by less-involved consumers increases in response to recovery-related causes. Opportunities to increase the positive effect generated by CrM campaigns on promoter firms and hazard-exposed communities are also discussed.

§ 1.2.3. Engaging consumers to better manage crisis

The article “How risk and uncertainty perceptions affect consumption? Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to analyse seafood consumption after the Fukushima accident” introduces to the discussion the link between consumers’ engagement and crisis management. The study offers an analysis of the crisis of seafood consumption in Japan through investigating the consumers’ (tourists and residents) perspective. Previous studies highlight a gap in the literature regarding whether people perceive risk and uncertainty consistently across situations that involve similar levels of objective risk or whether perceptions of risk and uncertainty are context-specific. Our study aims to offer a contribution in order to fill this gap. This unique study focuses on radioactive seafood contamination and the generated mid-long term effect on seafood consumption. The proposed case

13

study focuses on the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant (FDNPP) accident triggered by the Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami (GEJET) on 11 March 2011. The nuclear accident generated a seafood consumption crisis in the short-term post-event in Japan and only recently, wholesale fishery markets and fishery processing facilities in Iwate, Miyagi and Fukushima Prefectures resumed operations. According to the local Government, eating Japanese seafood is now safe. However, an internal crisis of seafood consumption still exists and new effective marketing strategies need to be identified in order to promote Japanese seafood consumption. Our study aims to investigate if and how the mid-long term effect of the Fukushima nuclear accident influences the trends of the Japanese seafood consumption. In order to do that, we analysed consumers planned behaviour regarding the intention to consume NON-Fukushima prefecture seafood (NFS) and Fukushima prefecture seafood (FS). To conduct the study, a questionnaire was developed. Participants to the survey were contacted during the winter in 2016/2017. Respondents included residents attending the Festival of the Goden Community Association (Machizukuri) in Higashinada Ward, Kobe. Tourists have been interviewed at the Fushimi-Inari Temple in Kyoto. Descriptive analysis and twelve path regressions have been used in order to analyse the data. Emerging findings highlighted that perceptions of risk and uncertainty are seafood origin-related specific and differ when considering residents or tourists. Managerial implications have been discussed in order to refine consumer-oriented marketing strategies able to promote Japanese seafood consumption. Suggestions for additional future research and limitations are also provided in the last section of the article.

§ 1.2.4. Snapshot of the Ph.D. papers

In the following table entitled “Snapshot of the Ph.D. papers”, some relevant details of the four papers are reported.

14

Snapshot of the Ph.D. papers

Crisis and disaster within the tourism industry: Towards the

definition of an interdisciplinary research

agenda

Cause-related Marketing and disaster management: opportunities from

tourism-related initiatives

Cause-related marketing and disaster management: A

comparative analysis of prevention- and

recovery-related campaigns

How risk and uncertainty perceptions affect consumption? Using the Theory

of Planned Behaviour to analyse seafood consumption

after the Fukushima accident

Authors Giuseppe Aliperti, Francesco Rizzi, Matthias Garschagen, Michael Hangelocher, Simone Sandholz, Marco Frey

Giuseppe Aliperti, Francesco Rizzi, Marco Frey

Giuseppe Aliperti, Francesco Rizzi, Marco Frey

Giuseppe Aliperti, Ana Maria Cruz, Francesco Rizzi, Marco Frey

Status Under review

Journal: Tourism Management; Previous versions:

- Accepted as oral presentation at the Elsevier 4th World Research Summit for Tourism and Hospitality: Innovation, Partnerships and Sharing (8-11 Dec 2017, Orlando);

- Poster presentation at the conference “From the management of crisis to the governance of risk: Time for a paradigm shift?”, School of Public Policy and Management of Tsinghua University, China Institute for Reform and Development and Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard Kennedy School. Hainan, China 9-11 Jan. 2017.

Accepted as Book chapter: Aliperti, G., Rizzi, F., Frey, M.,

“CRM and disaster

management: opportunities

from tourism-related

initiatives”, Book chapter in the Routledge Companion to Risk, Crisis and Security in Business, Taylor and Francis - Accepted 05/12/2016

Under review

Journal: International Journal of Research in Marketing;

Previous version:

- Conference paper, oral presentation:

Aliperti, G., Rizzi, F., Frey, M. (2017). Cause-related marketing and disaster management: A comparative analysis between prevention- and recovery-related campaigns. Working

Papers Series on Social

Responsibility, Ethics &

Sustainable Business. 6th

International Conference on Social Responsibility, Ethics and Sustainable Business. Organizer: Bournemouth University. Berlin, Germany, Vol. 6, pp. 13-14 - ISSN: 7222; ISSN-L: 2285-7222

Under review

Journal: International Journal of Research in Marketing;

Previous versions: (1) only residents

- (Published) Aliperti, G., Cruz A.M., Rizzi, F., Frey M. (2017). Risk and Uncertainty: A Side-Effect of a Natech Event on Residents in Japan,

Kyoto University DPRI Annuals, No

60 B 2017, pp. 335-342

- oral presentation at the “3rd International Symposium on Natural and Technological Risk Reduction at Large Industrial Parks (Natech-2017)”, Osaka University, Osaka (Japan) - Mar, 2017; (2) only tourists:

- oral presentation at the 8th Conference of the International Society for Integrated Disaster Risk Management (IDRiM 2017). Organized by University of Iceland, NORDRESS, the Nordic Centre of Excellence on Resilience and Societal Security. Reykjavík, Iceland 23-25 Aug. 2017.

15

Paper Aims Our study aims at:

- defining crisis and disaster within the tourism-oriented academic community;

- defining a tourism-oriented research agenda able to identify;

- contributing to the

achievement of the

recommendations provided by European Parliament regarding the EUSF.

Our study aims at:

- analysing the existing disaster-related CrM campaigns promoted by tourism firms; - Identifying useful insights to be applied to disaster- and tourism- related campaigns based on CrM-oriented studies.

Our study aims at:

- more in-depth investigating the opportunities provided by the adoption of CrM campaign within the tourism industry; - comparing the efficacy of prevention- Vs recovery-related campaigns;

- analysing the behavioural differences between less- and more-involved consumers; - identifying consumer-oriented marketing solutions.

Our study aims at:

- investigating whether people perceive risk and uncertainty consistently across situations that involve similar levels of objective risk;

- investigating whether perceptions of risk and uncertainty are context-specific; - analysing the mid-long term effect generated by a Natech accident on the crisis of seafood consumption;

- identifying consumer-oriented marketing solutions.

Research Questions/ Hypotheses

Can the tourism-related literature contribute to clearer state the difference between the crisis and disaster and therefore contribute to a more general understanding of the two concepts?

Can the current body of knowledge on Cause-related Marketing contribute to the success of this marketing strategy among tourism companies and therefore increase the availability of funds to be invested in order to increase the resilience of disaster-exposed community?

H1: Campaign attitudes and participation intentions are greater when the donation is linked to a recovery-related cause rather than to a prevention-related cause; H2: If the grade of consumer’s involvement will increase, the campaign attitudes and participation intentions will be greater when the donation is linked to a prevention-related cause rather than a recovery-related cause;

H3: The above-mentioned effects in hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2 are influenced by the perceived corporate social responsibility, which can mediate the relationship between attitude and intention.

H1 – H6: Testing TPB in our specific setting; H7: The more the PU increases, the more the ATT will increase (a). The more the PR increases, the more the ATT will decrease (b); H8: The more the TRU increases, the more the ATT will increase (a). The more the TRU increases, the more the PU (b) and PR (c) will decrease; H9: The more the TRU increase, the more the KN will increase (a). The more the more the KN increases, the more the ATT will increase (b). The more the KN increases, the more PU (c) and PR (d) will decrease.

16

Background Gap emerging from the literature.

Gap emerging from the peer-reviewed literature and the grey literature.

Gap emerging from the literature.

Gap emerging from the literature.

Data/Cases Only peer-reviewed papers. Peer-reviewed papers and grey literature.

The study focuses on the consumer behaviour of European tourists, who are part of Generation Y and who have a Facebook account. Participants in the survey were contacted between May and September 2016. The snowball sampling technique was used. A total of 647 questionnaires were collected.

The study focuses on tourists’ and residents’ behaviour. Participants to the survey were contacted during winter 2016/2017. A total of 309 respondents, fairly divided in residents and tourists, participated to the survey and filled the whole questionnaire (238 Gen Y respondents have been considered)

Methodology Systematic literature review (only peer-reviewed papers; 111 articles).

Systematic literature reviews (158 and 6 articles) enriched by grey literature. Survey. Seemingly Unrelated Regression. Survey. Path regressions.

Contributions The study identifies a research agenda that suggests developing a constant interdisciplinary dialogue and to more in-depth focusing on the resource management issue in order to clearly define disaster and crisis.

The study identifies the necessity to increase the number of studies focused on CrM within the tourism industry. Specific suggestions for further research has been provided.

Findings show that different disaster-related causes may generate different results. Prevention-related campaigns appear to be more effective than recovery-related campaigns when focusing on the total number of respondents, and are able to influence the perceived corporate social responsibility (CSR). The intention to participate by less-involved consumers increases in response to recovery-related causes. Opportunities to increase the positive effect generated by CrM campaigns on promoter firms and hazard-exposed communities are also discussed.

Emerging findings highlighted that perceptions of risk and uncertainty are seafood origin-related specific and differ when considering residents or tourists.

Managerial implications have been discussed in order to refine consumer-oriented marketing strategies able to promote Japanese seafood consumption among residents and tourists.

17

§ 1.3. References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision

processes, 50(2), 179-211.

Ashley, C., Noble, S. M., Donthu, N., & Lemon, K. N. (2011). Why customers won't relate: Obstacles to relationship marketing engagement. Journal of Business Research, 64(7), 749-756.

Bowden, J. (2009a). The process of customer engagement: A conceptual framework. Journal of

Marketing Theory and Practice, 17(1), 63-74.

Bowden, J. (2009b). Customer engagement: A framework for assessing customer-brand relationships: The case of the restaurant industry. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18(6), 574-596.

Brodie, R. J., Hollebeek, L. D., Jurić, B., & Ilić, A. (2011). Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 252-271.

Brodie, R. J., Ilic, A., Juric, B., & Hollebeek, L. (2013). Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 105-114.

Casaló, L., Flavián, C., & Guinalíu, M. (2007). The impact of participation in virtual brand communities on consumer trust and loyalty: The case of free software. Online information review, 31(6), 775-792.

Chan, K. W., & Li, S. Y. (2010). Understanding consumer-to-consumer interactions in virtual communities: The salience of reciprocity. Journal of Business Research, 63(9), 1033-1040.

de Sausmarez, N. (2007). Crisis management, tourism and sustainability: the role of indicators.

Journal of sustainable tourism, 15(6), pp.700-714.

Faulkner, B., & Russell, R. (1997). Chaos and complexity in tourism: In search of a new perspective.

Pacific Tourism Review, 1(2), pp. 91-106.

Faulkner, B. (2001). Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tourism

Management, 22(2), pp.135–147.

Gruen, T. W., Osmonbekov, T., & Czaplewski, A. J. (2006). eWOM: The impact of customer-to-customer online know-how exchange on customer-to-customer value and loyalty. Journal of Business research, 59(4), 449-456.

Hall, C.M. (2010). Crisis events in tourism: subjects of crisis in tourism. Current issues in Tourism, 13(5), pp.401-417.

Higgins, E. Tory and Abigail A. Scholer (2009), ‘‘Engaging the Consumer: The Science and Art of the Value Creation Process,’’ Journal of Consumer Psychology, 19 (2), 100-114.

Hollebeek, L. D. (2011). Demystifying customer brand engagement: Exploring the loyalty nexus.

18

Gleick, J. (1987). Chaos: Making a new science. London: Heinemann.

Lam, T., & Hsu, C. H. (2006). Predicting behavioral intention of choosing a travel destination.

Tourism management, 27(4), 589-599.

Lusch, R. F., & Vargo, S. L. (2010). SD logic: accommodating, integrating, transdisciplinary. Grand

Service Challenge, University of Cambridge, September 23.

Mollen, A., & Wilson, H. (2010). Engagement, telepresence and interactivity in online consumer experience: Reconciling scholastic and managerial perspectives. Journal of business research, 63(9), 919-925.

Peat, F. D. (1991). The philosopher's stone: Chaos, synchronicity and the hidden order of the world. New York: Bantam.

Pham, M. T., & Avnet, T. (2009). Rethinking regulatory engagement theory. Journal of Consumer

Psychology, 19 (2), 115–23.

Patterson, P., Yu, T., & De Ruyter, K. (2006). Understanding customer engagement in services. In Advancing theory, maintaining relevance, proceedings of ANZMAC 2006 conference, Brisbane (pp. 4-6).

Prideaux, B., Laws, E. & Faulkner, B. (2003). Events in Indonesia: Exploring the limits to formal tourism trends forecasting methods in complex crisis situations. Tourism Management, 24, pp.475– 487.

Quintal, V. A., Lee, J. A., & Soutar, G. N. (2010). Risk, uncertainty and the theory of planned behavior: A tourism example. Tourism management, 31(6), 797-805.

Scott, N., Laws, E. and Prideaux, B. (2008). Tourism crises and marketing recovery strategies.

Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 23(2-4), pp.1-13.

Schau, Hope Jensen, Albert M. Muniz and Eric J. Arnould (2009), ‘‘How Brand Communities Create Value,’’ Journal of Marketing, 73 (September), 30-51.

Speakman, M. & Sharpley, R. (2012). Journal of Destination Marketing & Management A chaos theory perspective on destination crisis management: Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Destination

Marketing & Management, 1(1–2), pp.67–77.

Speakman, M. (2017). A paradigm for the twenty-first century or metaphorical nonsense? the enigma of complexity theory and tourism research. Tourism Planning & Development, 14(2), pp.282-296.

Van Doorn, J., Lemon, K.E., Mittal, V., Naβ, S., Pick, D., Pirner, P. and Verhoef, P.C. (2010), “Customer engagement behavior: theoretical foundations and research directions”, Journal of

Service Research, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 253-266.

Vargo, S. L. (2009). Toward a transcending conceptualization of relationship: a service-dominant logic perspective. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 24(5/6), 373-379.

20

§ CHAPTER 2 – “Crisis and disaster within the tourism industry: Towards the definition of an interdisciplinary research agenda” 1

Abstract

The tourism industry worldwide is often highly exposed and vulnerable to a range of hazards and over the last years disasters and crises strongly impacted it. Tourism involves the interactions of organizations, people, and events in a variety of subsystems. The complexity of this interconnected system and the relatively early-stage of tourism-related crisis and disaster studies suggests that a dialogue between the tourism and the disaster risk research communities could be beneficial in order to share knowledge and define gaps regarding crisis and disaster risk management affecting the tourism industry. Our study aims at filling this gap by reviewing key contributions on crisis and disaster risk management and adopting a systematic approach to review the tourism-oriented literature on the topic. A total of 113 relevant publications were analyzed. The findings reveal bi-directional benefits and point towards a research agenda for the future.

Keywords: Crisis; Disaster; Tourism industry; Research agenda; Resource management; Preparedness

§ 2.1. Introduction & theoretical background

Over the last decades crises and disasters have caused significant loss and damage, also imposing a major burden on the tourism industry worldwide as it is often highly exposed and vulnerable to a range of natural and man-made hazards (Pforr and Hosie, 2008). In turn, direct and indirect losses to the tourism sector resulting from crises or disasters not only have an impact on the tourism industry itself, but on entire economies in affected countries, particularly in countries where large proportions of the GDP are directly or indirectly generated through tourism. It is therefore not surprising that the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 calls for the promotion and integration of disaster risk management (DRM) approaches throughout the sector (UNISDR, 2015). In consequence, the number of studies and associated body of knowledge focusing on the mutual linkages between tourism and crisis and DRM are on the rise (Mair et al., 2014).

According to the Systems Theory (Von Bertalanffy, 1950; Carlson, 1999; Scott and Laws, 2005), tourism activities involve the interactions of organizations, people and events in a variety of subsystems (Scott and Laws, 2005). Therefore, crisis and disaster in tourism have been analyzed from several perspectives and by different academic communities over the past years.

1 Authors: G. Aliperti(1), F. Rizzi (1), M. Garschagen(2), M. Hangelocher(2), S. Sandholz(2), M. Frey (1)

(1) Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna, Pisa, Italy

21

Due to interconnected system and the relatively early-stage of the tourism-related crisis and disaster studies, a dialogue between different disciplines could be beneficial in order to share knowledge, identify knowledge and research gaps and propose ways forward regarding crisis and DRM. Therefore, our study focuses on the mutual opportunities and benefits that can be generated from a dialogue between the tourism-focused investigations and the more general crisis and DRM-oriented studies.

The first necessary step to facilitate such a dialogue between two different actors, however, is the development of a common language. While there has been significant progress in terms of harmonizing the disaster risk reduction (DRR) and DRM dictionary within and across the DRR and climate change adaptation communities over the past years, just focusing on the tourism-related studies, the use of crisis and disaster seems to be blurred and interchangeably as there is no clear and commonly accepted definition of both terms within the academic community (Cró and Martins, 2017; Ghaderi, Mat Som, and Wang, 2014; Prideaux, 2013; Walters and Mair, 2012; Li, Blake, and Cooper, 2010; Racherla and Hu, 2009; Carlsen and Liburd, 2008; Pforr and Hosie, 2008; Cheung and Law, 2006; Henderson, 2003; Shaluf, Ahmadun, and Mat Said, 2003).

This aspect could appear as a simple terminological issue; however, it has managerial implications. In order to strategically plan for effective crisis and disaster management, it is necessary to know what crisis and disaster are (McCool and McCool, 2010). Understanding crisis and disaster, including overlaps and differences between the two, is necessary to develop strategies to be taken by the tourism industry in order to deal with such events (Bronner and De Hoog, 2012), and to reduce the severity of their impacts on business and society (Ritchie, 2004). A concrete example of how clearer definitions of crisis and disaster may for instance influence disaster-related funds management is the European Union Solidarity Fund (EUSF) Regulation (Cró and Martins, 2017; European Parliament, 2013). The EUSF provides financial support to a Member State in the event of a major natural-hazard triggered disaster. The regulation identifies few recommendations included in the ‘European Parliament resolution of 15 January 2013 on the European Union Solidarity Fund, implementation and application (2012/2075(INI)) (European Parliament, 2013). These recommendations refer to (i) budgetary discipline, (ii) reduction of the time taken to provide aid, and (iii) a greater clarity as regards scope and definitions (Cró and Martins, 2017). A crucial point is emerging from the resolution: The European Parliament considers that the time currently taken to mobilize the fund is unacceptably long, introducing the possibility of paying advances as soon as the affected state has applied for assistance (Cró and Martins, 2017). The aid would have to be returned to the Union budget in case the application was not accepted as disaster. It is therefore necessary to define clearly and simply what a disaster and what a crisis is (see Cró and Martins, 2017).

Cró and Martins (2017) identified a gap in the tourism industry linked to the correct allocation of negative shocks in international tourism arrival demand to crisis or disaster phenomena. To solve this gap, they developed a reliable tool to ex-post detecting the impacts of crises or disasters to provide useful information to governments, destination managers and hotel managers (Cró and Martins, 2017). However, their study is not explaining why and how every specific event that has been taken in consideration in the analysis has been classified as a crisis or as a disaster. Although some elements can be easily identified as crisis due to their definition (e.g. financial crisis; economic

22

crisis) the distinction between crisis and disaster seems to be more blurred when they include events as SARS, Avian Flu, Arab Spring, etc. in the analysis. Here, a clearer distinction could contribute to a more meaningful model and interpretation of the results.

Our study aims at contributing to filling this gap with the purpose to define a tourism-oriented research agenda to systematically classify crisis and disaster. The managerial implications generated by this kind of study will among others contribute to clearer describe disaster and crisis within the tourism-related literature and policy, and thus to achieving the recommendations of the European Parliament regarding the EUSF.

In addition, the study will contribute to fill the gap identified by Carlsen and Liburd (2008) regarding the necessity to define a focused and tourism-oriented research agenda on crisis and disaster management. Mair et al. (2014) partially filled this gap by identifying new research opportunities after reviewing recovery-related and destination-focused contributions. Our study offers a different perspective able to further enrich the discussion by extending the focus of the analysis beyond the recovery phase.

§ 2.2. Method

The method that has been adopted in order to conduct the study includes two steps.

First, considering the huge amount of studies focused on crisis and DRM, we assessed the most relevant contributions (according to the authors’ judgement) from the disaster risk research community in order to clarify concepts and definitions and to enrich the further analysis concentrated on the tourism-related literature.

In a second step, we then adopted a systematic approach to review peer-reviewed literature focused on crisis and disaster in the tourism-industry. In order to do that, we followed the methodology of Mair et al. (2014) in consideration of its respect of the criteria for trustworthiness previously identified by Decrop (2004): credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability (see Mair et al., 2014). Search terms included ‘tourism AND disaster AND crisis’. We included the EBSCO host research database (Business Source Complete - BSC) as the main source to identify relevant articles, following Mair et al. (2014). In addition, we also considered contributions published in Scopus and Web of Knowledge. Only double-blind peer reviewed academic articles published in English language were included in the review. Industry reports, conference papers and book chapters were not included in the review.

The systematic review comprises papers published between January 2001 and May 2017. These dates were chosen in order to set finite boundaries for the review. We mainly focus on publication from the new millennium (Mair et al., 2014). A total of 88 relevant contributions emerged from Scopus, 52 from EBSCO-Business Source Complete, 19 from Web of Knowledge. After excluding overlaps, 113 relevant publications were identified and analyzed, including journal and year of publication. In a next step, an open coding scheme has been applied to the articles with the aim to

23

breaking down the data into different parts and look for similarities and differences between the concepts of crisis and disaster. Data exploration and the preliminary synthesis was undertaken using Microsoft Excel.

§ 2.3. Results

2.3.1. Disaster vs crisis in the disaster risk literature

Disasters may be classified into different macro-areas depending on the typology of hazards that generate them.

(a) Disasters related to (natural) hazards. The expression “natural disaster” has long been

considered a misnomer (O’Keefe et al., 1976; Schipper and Pelling, 2006) as main causes of disasters are related to human actions (Schipper and Pelling, 2006). Natural disasters do not exist, they result from the interaction of hazards, such as droughts, earthquakes, epidemics, extreme temperatures, floods, insect infestations, mudslides, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, and wild fires (Oh and Oetzel, 2011; Hood and Jackson, 1992) and the vulnerability of exposed elements, such as people, infrastructure, ecosystems, etc. (Pachauri et al., 2014).

(b) Disasters purely linked to human activity. Man-made hazards (Hood and Jackson, 1992) are linked to human activities and can be divided in technological and social hazards. An exemplificative list of technological hazards is provided by UNISDR (2009) and includes hazards such as industrial pollution, nuclear radiation, toxic wastes, dam failures, transport accidents, factory explosions, fires and chemical spills. Social hazards may refer to the use of violence or the threat of violence to attain political or ideological goals (i.e. terrorist attacks, (Wernick, 2006)).

(c) Disasters related to hybrid hazards. Hybrid hazards are generated by the interaction of

different hazards. For instance, social hazards and technological hazards may merge generating socio-technical disasters (Richardson, 1994). Natural hazards may result in conditions able to interact to technological hazards by generating joint events, which in combination generate a “Natech” accident (Krausmann and Cruz, 2013). UNISDR (2009) defines the mix between social and natural hazards as socio-natural hazards. This form of hybrid hazard is linked to the natural (including biological) hazards created by the process of environmental degradation generated by the human activity (UNISDR, 2009).

Depending on the size of the affected system and on the type of the required assistance, disasters may be divided in small-scale and large-scale disaster (UNISDR, 2009). Disaster may be also classified depending on their onset (UNISDR, 2009). Disaster characterized by sudden onset caused by natural hazards (i.e. earthquakes, hurricanes, tornadoes) or human behaviors (i.e. terrorist attacks, coups d’état, industrial accidents). Or disaster characterized by slow onset caused by natural hazards (e.g. famines, droughts, poverty) or human behavior (e.g. political crises) (Van Wassenhove, 2006).

Disaster’s impact is the total effect, including negative effects and positive effects (UNISDR, 2009). In fact, disaster may generate loss and damage in terms of human lives, the physical environment,

24

economic and social impacts (Shaluf, Ahmadun, and Mat Said, 2003) and other negative effects on human physical, mental and social well-being (UNISDR, 2009). However, disasters may also create windows of opportunity for change and lead to new foreign investment because new investors are attracted by the possibility to take advantage from large government recovery project and because, during the recovery stage, consumers are likely to demand new products and services in order to return to their normal lives (Vigdor, 2008).

Finally, according to the Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) terminology provided by UNISDR (2009), disaster management is linked to resource management as it is a “serious disruption of a community

or a society … that may test or exceed its capacity to cope using its own resources” (UNISDR, 2009;

pag.09).

Referring to crisis, the scientific literature offers an even broader understanding, focusing on the financial system (Crotty, 2009), economy (Stiglitz, 2000), energy (Li, 2007), environment (Wilshusen et al., 2002; Saurin, 2001; Harris, 1991), food (Loewenberg, 2008), health (Chen et al., 2004), population and demographics (Sinding, 2000; Peterson, 1999), water (Duda & El-Ashry, 2000) and the interdependence of these elements in political terms (Gills, 2008) (Hall, 2010). For this reason, the concept of crisis involves multiple disciplines and requires to be analyzed and managed using a systems approach (Pearson and Clair, 1998; Pauchant & Mitroff, 1992).

Crisis management is largely based on an event-centered approach that considers the shock event as the triggering event that makes the crisis visible (Shrivastava, 1992). This revealing power

of the event has led many authors and managers to mistake the event for the crisis itself

(Roux-Dufort, 2007b). This so-called event-centered approach to crisis management has been partially criticized (Roux-Dufort, 2007b) as the crisis occurrence seems to be more linked to a process of incubation that starts long before the triggering event (Roux-Dufort, 2007b; Groeneweg, 1992). This vision refers to an evolutionary approach and conceptualizes the crisis both as an exceptional situation and part of a process (Roux-Dufort, 2007b). The evolutionary process includes different phases: warning signals, acute stage, amplification and resolution (Gatot and Jacques, 1999; Mitroff and Pearson 1993; Turner 1976; Fink 1986). The acute phase is just the peak of the accumulation of organizational dysfunctions that have existed for a long time but that have been under-estimated (Roux-Dufort, 2007b). Crisis creates uncertainty and poses a direct perceived threat to the goals and norms of an organization or society (Coyne, 2011). It is a transitional phase characterized by surprise, unpleasantness and urgency (Congleton, 2004), during which the normal ways of operating no longer work (Boin,‘t Hart, and Sundelius, 2005).

Substantially, the event-centered approach considers the triggering event as the starting point of the crisis. The processual approach considers the shock event as the point of arrival of a destabilizing process which has been previously ignored (Roux-Dufort, 2007b).

Crises can be divided into natural crisis triggered by disasters from natural hazards; industrial crisis generated by socio-technical disasters; non-industrial crises composed by the conflict type (political crisis) and non-conflict type crisis (economic and social) (Quarantelli, 1988).

25

The crisis of an organization/system is a phenomenon for which psychological, social-political, and technological-structural issues interact and act as important forces in their creation and management (Pearson and Clair, 1998). It describes a situation caused by inept management structures and practices or due to a failure to adapt to change (Faulkner, 2001).

Exactly as disasters, crises can also generate positive effects. Ulmer and Sellnow (2002) emphasize renewal and growth over issues of blame, responsibility, and liability after a crisis. Birkmann et al. (2013) report how disasters and crises can also catalyze reorganization and learning in communities or societies, often accelerating underlying policy and social trajectories. For instance, according to Pelling and Dill (2010), after the Marmara earthquake (1999) and a small earthquake that hit Athens soon after, the relations between Greece and Turkey improved due to bilateral post-disaster aids.

Finally, despite the fact that the term crisis is constantly used within the DRR-related literature, no definition of crisis is included in the current UNISDR DRR Terminology (UNISDR, 2009). This approach is in line with organization theorists’ attitude that showed little interest in theorizing the concept of crisis as this concept fosters paradoxical attitudes (Roux-Dufort, 2007a). In fact, from one side, suddenness and dramatic dimension of crises fascinate researchers (Roux-Dufort, 2007b). On the other side, its abnormal absurd and sometimes destructive nature can repel a number of them (Roux-Dufort, 2007b). Definition of crisis and attempts to categorize types or forms of crises have been sparse (Santana, 2004) and this is the reason why some authors remain fairly vague and provide more generalized statements on the nature of crises (Pforr and Hosie, 2008).

Finally, what is the difference between crisis and disaster in the DRR literature?

Both disaster and crisis may be classified depending on the hazards able to trigger their occurrence. The hazards can be natural, human, or hybrid. Both disaster and crisis may threaten an organization’s survival and are able to generate negative and positive effects. All those similar elements contribute to blur the concrete difference between the two concepts.

However, an interesting input to better differentiate between crisis and disaster is emerging from the PAR and Access model (Wisner et al., 2004). This model describes the progression of vulnerability that may lead to disaster. It is formed by root causes, dynamic pressures and unsafe conditions. The Access Model refers to the concept of “normal life” that explains how people earn a livelihood with differential access to material, social and political resources. This aspect influences the transition to disaster and this perspective offers food for thoughts regarding the concepts of crisis and disaster if linked to the results emerging from the following tourism-oriented systematic literature.

26

2.3.2. Review of tourism-oriented literature on disaster and crisis: key trends

The systematic literature review has been conducted in order to investigate the tourism-oriented studies focused on crisis and DRM. It mainly includes articles that have been published in tourism-oriented journals; however, it also includes journals that usually not consider tourism as main topic of investigation to cover the maximum of relevant publications (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Journal publishing articles in this review

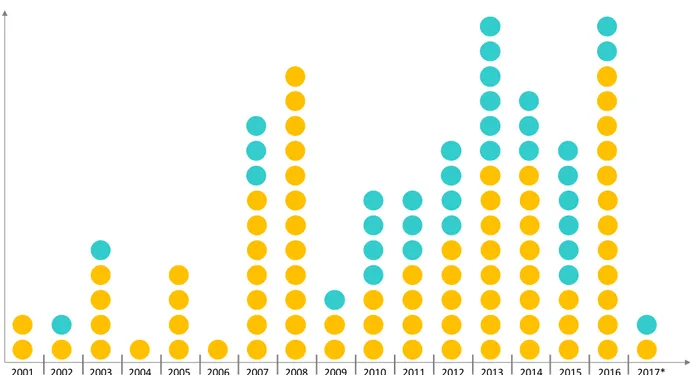

Considering the 113 analyzed publications, 3 journals emerge as main contributors: Tourism Management (15 articles); Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing (14 articles); and Current Issues in Tourism (10 articles). This information illustrates that many of the articles dealing with the concepts of crisis and disaster are published in highly respected journals. The peak in 2008 (see Figure 2) can be explained by the publication of a special issue promoted by the Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing (Mair et al., 2014). However, it is interesting to note that starting from 2013 an increasing number of studies were linking crisis and disaster within the same study.

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Tourism-related journals (Main contributors: Tourism Management (15 articles), Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing (14 articles), Current Issues in Tourism (10 articles).

Other journals

27

Figure 2 – Publications linking crisis and disaster: the trend

Our article confirms the increasing interest of tourism-related studies to crisis and disaster management (Mair et al., 2014). However, it also reveals that the two terms are sometimes used synonymously (Ghaderi, Mat Som, and Wang, 2014; Prideaux, 2013; Walters and Mair, 2012; Li, Blake, and Cooper, 2010; Racherla and Hu, 2009; Cheung and Law, 2006) and sometimes as different concepts (Ritchie, 2004; Faulkner, 2001). Only 30 of the 113 articles explain how the concepts of crisis and disaster have been defined within the study (Table 1). Tourism Management mainly contributed to this issue during the years 2001-2008. Additional 12 journals enriched the discussion during the remaining years.

Table 1 – Papers defining crisis and/or disaster (per year; per Journal)

Other two additional and interesting findings emerge from the review. The first one is that 23 out of 30 papers (76.7%) refer to the definitions of crisis and disaster offered by Faulkner (2001), highlighting the central role played by this contribution within tourism-related literature. According to Faulkner (2001, pag.36), ‘crisis is defined as a situation where the root cause of an event is, to

some extent, self-inflicted through such problems as inept management structures and practices or a failure to adapt to change. On the other side, disaster is a situation where an enterprise (or

0 5 10 15 20 01 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 0920 1020 2011 2012 1320 2014 2015 2016 2017 *

28

collection of enterprises in the case of a tourist destination) is confronted with sudden unpredictable catastrophic changes over which it has little control’

The second finding refers to the fact that 85 out of 113 papers (75.2%) are erroneously including the highly debatable expression ‘natural disaster’ (see par. 3.1), highlighting the necessity for a constant dialogue and exchange across disciplines. However, in order to facilitate such a dialogue, it seems to be necessary being aware of existing definitions in other disciplines and later defining a common language within the tourism industry itself. The difficulty to reach this common-language target seems to increase due to the several perspectives that have been used in the tourism-oriented literature in order to describe the concepts of crisis and disaster.

2.3.3. Crisis and disaster within the tourism literature

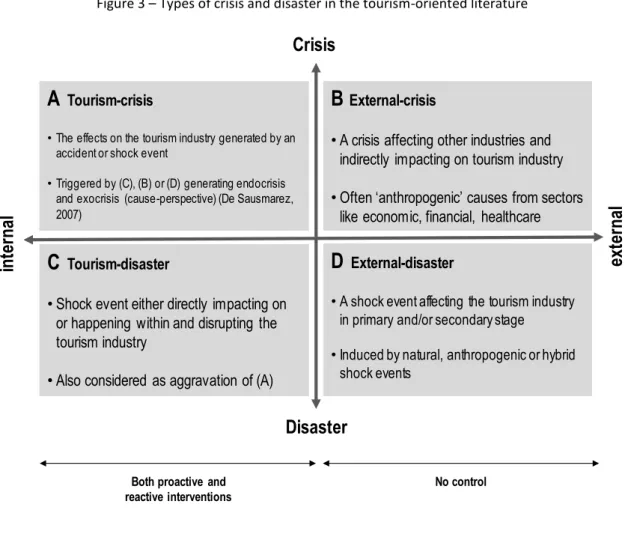

Four main types of crisis and disaster have been identified in the literature review: (A) Tourism-crisis: crisis within the tourism industry; (B) External-Tourism-crisis: crisis external to the tourism industry; (C) Tourism-disaster: disaster within the tourism industry; (D) External-disaster: disaster external to the tourism industry (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Types of crisis and disaster in the tourism-oriented literature

A

Tourism-crisis• The effects on the tourism industry generated by an accident or shock event

• Triggered by (C), (B) or (D) generating endocrisis and exocrisis (cause-perspective) (De Sausmarez, 2007)

B

External-crisis• A crisis affecting other industries and indirectly impacting on tourism industry • Often ‘anthropogenic’ causes from sectors

like economic, financial, healthcare

D

External-disaster• A shock event affecting the tourism industry in primary and/or secondary stage

• Induced by natural, anthropogenic or hybrid shock events Crisis Disaster int er nal ex te rnal

C

Tourism-disaster• Shock event either directly impacting on or happening within and disrupting the tourism industry

• Also considered as aggravation of (A)

Both proactive and

29

(A) Tourism-crisis. The term crisis refers to the effects on the tourism industry generated by an

accident or shock event (Gurtner. 2016; Waikar, Hedge Desai and Borde, 2016; Ergun, Heier, and Keskinocak, 2010; Bonn and Rundle-Thiele, 2007; Cheung and Law, 2006; Beeton, 2001). The effects of the crisis can be measured by tourists’ reservation trend (Sun and Wong, 2010; de Sausmarez, 2007; Coshall, 2003), hotel’s occupancy trends (Hamzah et al., 2012; Henderson, 2005; Henderson, 2003), economic losses of the tourism industry (Huang and Min, 2002), consumer confidence (de Sausmarez, 2007) or by the necessity for the companies to actualize organizational changes (Martín-Consuegra, Esteban, and Molina, 2008) or to evaluate the lack of knowledge about the crisis and its management (Paraskevas et al., 2013). Typically, the level of control that tourism-organizations have on these accidents or shock events allow for both proactive and reactive strategies as the crisis dynamics are internal to the tourism industry.

Following a cause-perspective and depending on the nature of the shock event, the crisis within the tourism industry has been defined “endocrisis” or “exocrisis”:

(A1) Endocrisis. The shock event may occur during the supply of the tourist service due to internal causes as well as inadequate or poorly maintained equipment or lack of staff training (Henderson, 2003; Beeton, 2001). When the trigger comes from within the tourism industry, the crisis might be called ‘endocrisis’ (de Sausmarez, 2007).

(A2) Exocrisis. The shock event may also be external to the tourism industry. In this case, literature suggests calling the generated crisis of the tourism industry as ‘exocrisis’ (de Sausmarez, 2007). This typology of event is characterized by the fact that it is unlikely to be anticipated by the tourism industry (de Sausmarez, 2007).

Within tourism-related literature, these external shock events are sometimes defined as crisis (see point B), sometimes defined as disaster (see point D). The external shock event is totally external to tourism management but still influencing the tourism industry’s trends.

(B) External-crisis. It is a crisis that is affecting other industries (i.e. economic; financial;

healthcare; etc.) (Amore and Hall, 2016; Bhati et al., 2016; Lashley and Warner, 2015; Buultjens, Ratnayake and Gnanapala, 2015; Cohen and Neal, 2010; Li, Blake, and Cooper, 2010; Min, 2008; Hall, 2010; Wang, 2009; Chen, 2007; Cioccio and Michael, 2007; Paraskevas and Arendell, 2007; Williams and Thwaites, 2007; Cooper, 2005; Prideaux, Laws and Faulkner, 2003; Henderson, 2003) that may indirectly affect tourism industry generating the exocrisis (following the cause-perspective proposed by De Sausmarez, 2007) (see point A2) or new opportunities, as for instance the generation of post-crisis industrial-sites of remembrance (Li and Soyez, 2016). Typically, tourism-organizations have no control at all on these external-crises, thus only reactive strategies are possible.

(C) Tourism-disaster. Typically, the level of control that organizations have on

30

tourism industry. Disasters emerging within the tourism industry can be classified in two sub-categories:

(C1) A shock event that happened during the supply of the tourist service (supply-concomitant event) and was able to generate tragic consequences on the community, including killing people. Tourism is not immune to disasters, as well as any human activity (Biran et al., 2014). Some examples are provided by the cultural heritage collapse (Weaver and Lawton, 2007), the collapse of the viewing platform at Cave Creek, New Zealand in 1994, killing 14 tourists or by the case of the 1999 canyoning disaster in Swiss Alps killing 21 tourists and emotionally devastating the local community (Beeton, 2001) and by the Singapore Airlines accident in 1997 (Henderson, 2003). This typology of event is able to generate endocrisis (A1) and it is facilitated by inept management structures and practices (just as the concept of crisis described by Faulkner, 2001 – see par. 3.2);

(C2) However, the term disaster is also used to describe extremely severe effect on the tourism industry able to destroy its existence (Burgin and Hardiman, 2012; Cooper, 2005). A crisis becomes disaster when it has the potential to totally disrupt the tourism industry (Cró and Martins, 2017). When a crisis escalates, it could end up with a disaster (Hanna Salman Sawalha, Eid Jraisat, and Al-Qudah, 2013; Wilks and Moore, 2003).

(D) External-disaster. Several authors define external disaster as the shock event that is not

happening within the tourism industry, but that is able, in a second stage, to affect it. The term disaster is often used in order to describe the event occurrence (see Morakabati, Page, and Fletcher, 2016; Tsao and Ni, 2015) as for instance earthquakes (Asokan and Vanitha, 2017; Orchiston and Higham, 2016; Dahles and Susilowati, 2013; Chongsuvivatwong et al., 2011; Huang, Tseng, and Petrick, 2008; Huang and Min, 2002), tsunamis (Pennington-Gray, Schroeder, and Gale, 2014; Carlsen and Hughes, 2008; Williams and Thwaites, 2007), volcanic eruptions (Jones, 2016; Chongsuvivatwong et al., 2011), tropical cyclones (Saverimittu and Varua, 2016; Prideaux, Coghlan, and Falco-Mammone, 2008), hurricanes (Gray, 2012; Baade and Matheson, 2007; Gotham, 2007; Williams and Thwaites, 2007; Lewis, 2005), floods (Jusoh et al., 2012; Williams and Thwaites, 2007), storms (Machado, 2012), diseases (Speakman, 2012; Min, Lim, and Kung, 2011; Miller and Ritchie, 2003; Frisby, 2002), and bushfires (Hystad and Keller, 2008; Cioccio and Michael, 2007).

Typically, tourism-organizations have no control at all on these external-disasters, thus only reactive strategies are possible.

The primary effect is measured focusing on the society and includes loss of life and property (Gursky et al., 2014; Coshall, 2005; Coshall, 2003; Lane, Tobin and Whiteford, 2003, Huang and Min, 2002; Roy et al., 2002), reduces the social capital of the community (Gibson, 2010; Niininen and Gatsou, 2008; Dolfman, Wasser, and Bergman, 2007) and influences the safety perception of the people as for instance in the case of the Fukushima accident (Kim and Park, 2016; Wu and Walters, 2016) or due to the presence of conflicts (Desivilya, Teitler-Regev, and Shahrabani, 2015), previous natural-hazard occurrence (Rittichainuwat, 2013; Ryu, Bordelon, and Pearlman, 2013), previous terroristic attacks (Coshall, 2003), or multiple risks (Schroeder and Pennington-Gray, 2014; Pennington-Gray, Kaplanidou, and Schroeder, 2013; Wang and Ritchie, 2013, 2012; Valencia and

31

Crouch, 2008;). The secondary effect is on the tourism industry (see point A2, exocrisis). For example, tourists will be seriously impeded if the transportation system is destroyed (Huang and Min, 2002 based on Tzeng and Chen, 1998) and they will probably look for alternative destinations (Huang and Min, 2002). However, the effect of the external disaster could be also positive in economic terms, when generating, for instance, the so-called disaster-tourism (dark tourism) increasing the number of tourists visiting the affected areas (Garland, 2015; Kaussen, 2015).

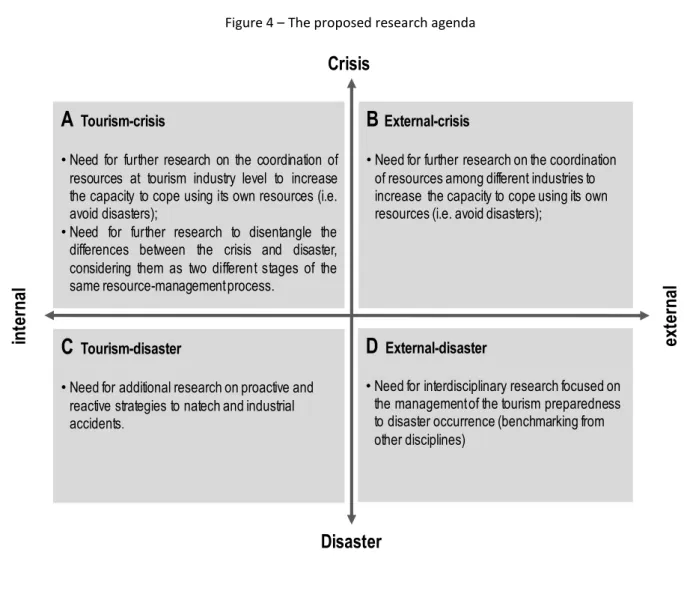

§ 2.4. Discussion: Identified gaps and research needs

Our classification of crisis and disaster within the tourism-related literature (par. 3.3) enriches the discussion on the management issue proposed by Faulkner (2001) by considering the four identified perspectives (tourism-crisis, tourism-disaster, external-crisis, external-disaster,).

Mair at al. (2014) and Ritchie (2008) previously highlighted that the majority of the tourism-related studies on crisis and disaster risk management are concerned on the recovery stage. Our study highlights that the majority of papers talks about crisis within the tourism industry but disasters external to it, which in turn then potentially trigger the tourism industry crisis (tourism-crisis generated by external disaster) – basically matching the definition of Faulkner (2001). In particular, effects generated by natural hazards are more investigated respect to those generated by natech accidents (e.g. Handler, 2016; Kim and Park, 2016; Wu and Walters, 2016) or industrial accidents (e.g. Ritchie et al., 2014). Further investigations may fill this gap in the literature.

It is interesting to note that only few authors investigate the management of the tourism industry preparedness to disaster occurrence (tourism-disaster) (Lew, 2013; Rittichainuwat, 2013; Biggs, Hall and Stoeckl, 2012; Pennington-Gray et al., 2011; Ritchie et al., 2011; de Sausmarez, 2007). This could have been influenced by the frequent adoption of Faulkner’s (2001) definition of disaster as a phenomenon over which the managers have little control and therefore potentially less tempting to investigate.

On the contrary, our review highlights that these disasters caused by inept management of the tourism suppliers are investigated from a preparedness perspective by tourism-related articles published by journals mainly oriented to other disciplines. In particular, Mäntyniemi (Disasters, 2011) focuses on the importance to evaluate the seismic risk during holidays in resorts and to the necessity to inform the tourists. Mohammad and OO (Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 2014) examine stakeholders’ proactive and/or reactive approaches in the built environment against disasters. Brown et al. (International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 2017), Hanna Salman Sawalha, Eid Jraisat, and Al-Qudah (Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 2013), and Peter, Pulston, and Losekoot, (Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 2014) investigate how hotels may manage their exposure to risk of crisis and disaster. The same perspective with an orientation to the tourism destination is provided by Marrero et al. (Natural Hazards, 2013) and Kim and Marcouiller (The Annals of Regional Science, 2015). An additional perspective, still related to the preparedness issue is provided by the International