1

Phd Course

Political Science, European Politics and International Relations

Populism and Democracy. Patterns of intra-party

participation in comparative perspective: the case of

Podemos and Five Star Movement

Academic Year

2018/2019

Authour

Alessandro Albertini

Supervisor

Sorina Soare

Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna Università degli Studi di Siena Università degli Studi di Firenze Università di Pisa2

Presentation of the work ... 5

The history of populism: from its origins toward a fourth wave of contemporary politics. ... 7

The elements of populism: delimitating the boundaries ... 11

Framing populism’s current challenge to democracy and the research approach ... 13

1. Focus of the research ... 13

2. Relevance of organization in party agencies ... 16

3. Organization and populist parties: state of the art ... 18

4. Aims and objectives of the research ... 19

Research design ... 21

1. Logic of the Research ... 21

Research Questions ... 23

2. Methodology and data collection ... 25

3. Case Selection ... 26

Summary of the research and chapter organization ... 34

Chapter 1 ... 37

The crisis of democracy and the challenge of populism ... 37

1.1 Introduction ... 37

1. 2 Crisis in Western consolidated democracies ... 37

1.3 The context of Western European democracies: liberalism, representation, the crisis of the neoliberal economic model after 2008 and the rise of populist parties. ... 41

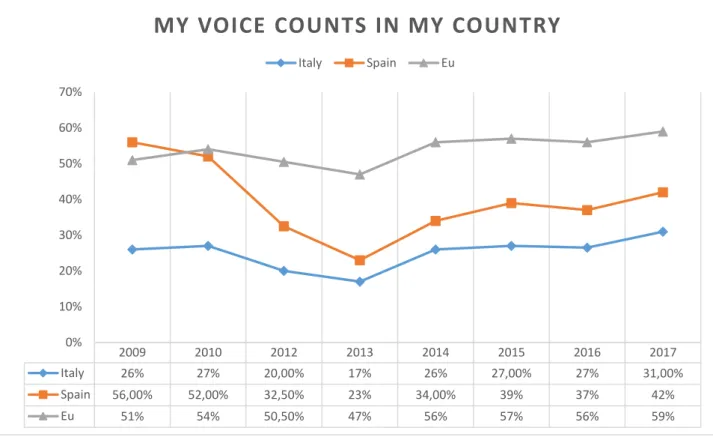

1.4 The political consequences of economic crisis in Southern Europe: the cases of Italy and Spain compared. ... 43

1.5 The populist challenge to democracy ... 47

1.6 Populism and representation ... 49

1.7 The challenge of intra-party democracy and the populist vision ... 50

1.8 Digital democracy: way of disintermediation? ... 54

1.9 Conclusions ... 59

Chapter 2 ... 60

Podemos and the Five Star Movement: history, ideas and framing of two “pro-seeking democracy” parties. ... 60

2.1 The political context in Spain and Italy before the rise of Podemos and Five Star Movement ... 60

2.2 The history of the Five Star Movement: from a comedian to grassroots politics. ... 62

2.2.1 From Palasport to the birth of Five-Star Movement ... 62

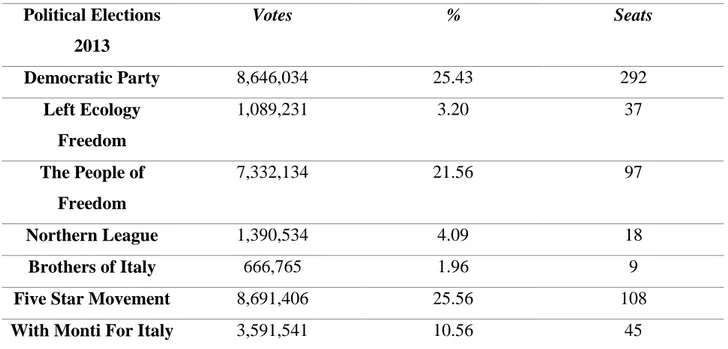

2.2.2 Second phase: from birth to the general elections of 2013: an amazing political earthquake. ... 65

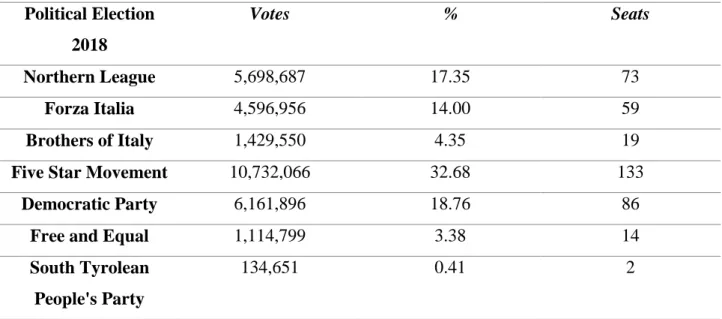

2.2.3 Toward a problematic institutionalization: the Five Star Movement from opposition to government. ... 68

3

2.3 Podemos: the rise and fortunes of a new-left populist party in the Spanish democracy ... 72

2.3.1 Spanish democracy in crisis and the Indignados movement: towards a change of paradigm ... 72

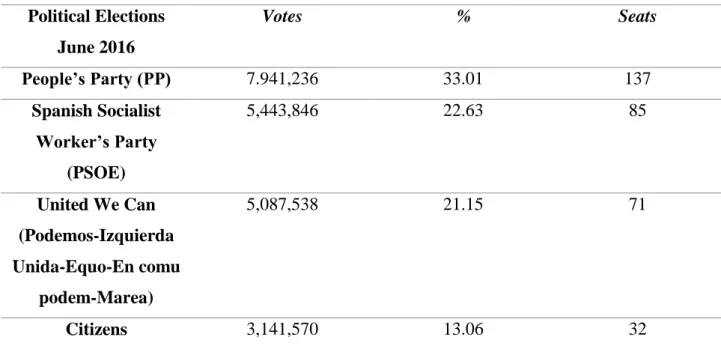

2.3.2 From Indignados to Podemos. The birth of Podemos and the success at the general elections of December 2015. ... 73

2.3.3 From bargaining with Socialists to Pedro Sanchez rise to power: the latest developments within a "pro-seeking democracy" half institutionalized party. ... 77

2.4 The organization of Podemos and Five Star Movement. ... 81

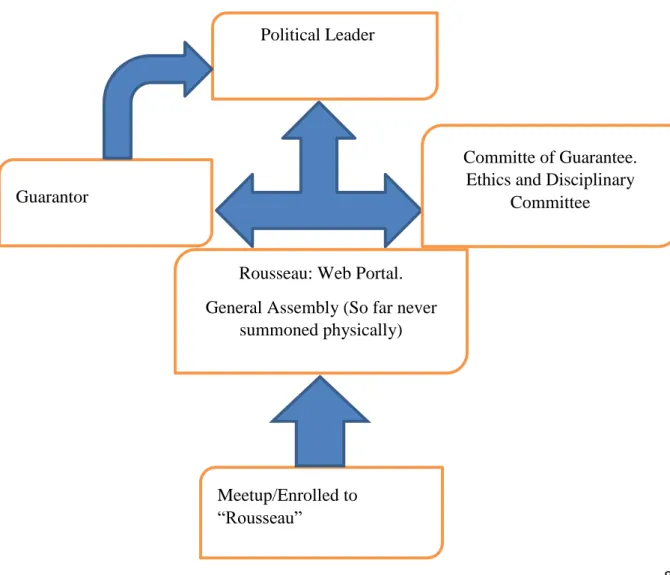

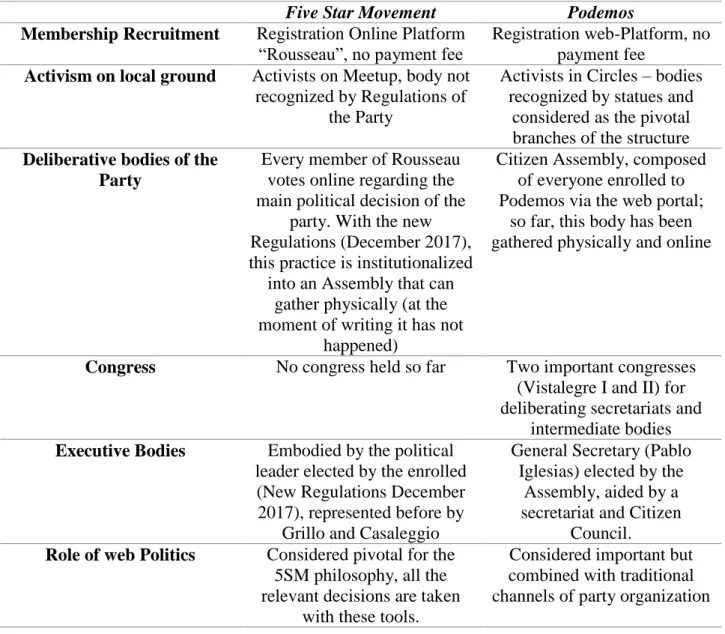

2.4.1 The organization of Five Star Movement ... 82

2.4.2 Podemos model: a hybrid organization from a movement ... 90

2.5 Five Star Movement and Podemos organization compared ... 96

2.6 The Five Star Movement’s ideology: the utopia of direct democracy. ... 99

2.7 Podemos: "Asaltar los cielo with 99% of the ciudadania". Podemos’ hypothesis regarding democracy ... 104

2.8. Conclusion: are Podemos and Five Star Movement more similar or more different? ... 106

2.8.1 Difference in Context ... 106

2.8.2 Leadership ... 108

2.8.3 The relationship between people vs casta duality and representation ... 111

Chapter 3 ... 114

From theory to practice: have Podemos and Five Star Movement renewed party politics?... 114

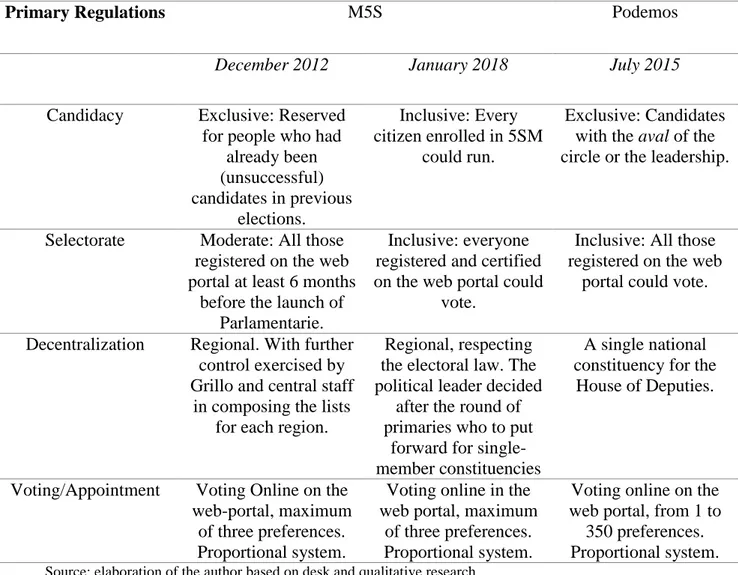

3.1 Candidate selection, rationales, rules and outcomes ... 117

3.1.1 Rationales in the Five Star Movement... 119

3.1.2 Podemos’s rationale ... 122

3.1.3 Practical rules and results: Five Star Movement and Podemos compared ... 125

3.2 The comparison of roles of the elected in Five Star Movement and Podemos: spokesperson not representatives? ... 134

3.2.1 The role of the elected in Five Star Movement ... 134

3.2.2 The role of the elected in case of Podemos ... 140

3.2.3 Comparison of the framing of representation between Five Star Movement and Podemos... 144

3.3 Local ground in Five Star Movement and Podemos: Meetup vs Circulo ... 147

3.3.1 Meetups in Five Star Movement ... 147

3.3.2 Podemos Circle ... 150

3.3.3 Podemos and Five Star Movement at a local level: a comparison ... 153

3.4 Decide Madrid and Bilancio Partecipativo: Rome and Madrid’s experiments in direct democracy ... 156

3.5 Conclusions ... 158

Chapter 4 ... 160

Has populism improved intra-party democracy and representation? ... 160

4.1 Summing up the thread of the thesis ... 160

4 4.3 Five Star Movement and Podemos’ conceptualization of the role of political parties in democracy and

intermediation ... 165

4.4 Strategies of “redeeming” democracy by inclusive populist parties ... 170

4.5 Populism and primaries: how the thin ideology shapes the party reform ... 172

4.6 Spokespeople or representatives: a hard goal to achieve ... 177

4.7 Conclusions and avenues for further research ... 182

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 185

5

Introduction

Presentation of the work

Considered to be one of the most relevant political phenomena of our time, populism has become a significant subject in the literature on party politics and democracy. The amount of studies dealing with populism is huge and gathers multidisciplinary perspectives, ranging from sociology (Hermet 2013), history (Zanatta 2017), and/or philosophy (Laclau 2005) to psychology (Blanuša 2011) and political science (Tarchi 2015, Mudde 2004, Hawkins 2010). Unsurprisingly, the definition of populism is one of the thorniest issues. While some scholars consider it to be a thin-centered ideology (Mudde 2004, Stanley 2008, Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017), others depict it as a political logic (Laclau 2005), a discursive style (Jagers & Walgrave 2007, Moffit & Tormey 2013) a discursive frame (Hawkins 2010), a frame (Aslanidis 2016) or, in particular in relation to the Latin-American area, a strategy (Weyland 2001). This last conception is one of the most criticized because it identifies as a core element of populism only the direct relationship between a political leader and the people, but, as Hawkins (2010 p. 168) has noted, this feature belongs to all parts of the political spectrum therefore, it becomes complicated to identify who is populist and who is not. In any case, the vast majority of the scholars agree on two important core elements defining populism:

1. A Manichean vision of politics with a contrast between the people, considered as a homogenous entity, and a corrupted elite or dangerous others

2. An endeavour to restore the general will of the people, which is jeopardized by the complicated mechanisms of representative democracy.

While both of these dimensions will be deepened in the next paragraphs, it is important to stress from the very beginning the implications of the theoretical debate regarding the different definitions. This theoretical focus is particularly interesting considering the starting condition of any analysis: a clear identification of who is populist and who is not. On this point, as has been stressed elsewhere it is important to remember that the literature is divided into two main groups: in the field of communication research, populism is a discursive style that can be employed by any political actor (Hawkins 2010, Jagers &Walgrave 2007), an approach allowing to identify degrees of populism; on the other hand party politics scholars in particular view populism as a thin-centered ideology: a perspective that makes it possible to establish an explicit distinction between the actors for which it represents a core ideological approach and other actors (Freeden 1996) (Zulianello et al. 2018 p. 2), More specifically, for a part of the literature populist parties are considered as such in line with their specific Weltanschauung, based on the two core elements mentioned above. For the other part of the

6 literature, the basic assumption is that parties may use certain elements of populist communications or pursue a particular strategy in relation to the context of reference. This difference is fundamental because it allows us to narrow the field of research and better distinguish between who is populist from an ideological perspective (actor-centered) and who is considered as such from a communication-centered analytical perspective (Stanyer et al. 2017) thus making it possible to determine political parties of different kinds.

Considering the above, this study focusses on two cases: Podemos (We Can) and Movimento Cinque Stelle (Five Star Movement, M5S), both associated with populism, although with differences in nuance. While Podemos relies on a specific legacy from the left political culture and neo-Gramscian culture (Errejon and Mouffe 2016, Iglesias 2015), M5S is a considered a form of “pure” populism (Tarchi 2015). Differences can be identified in terms of their origins too. While Podemos has arisen from a mix between a social movement legacy (15-M) and an intellectual top-down process, which has involved the major political scientists of University of Complutense in Madrid, Movimento was born at the beginning through only a top-down path, led by the comedian Beppe Grillo with the further aim of establishing genuinely direct democracy via the web.

However, the differences between the rhetoric of Grillo and the practice of his organization, analysed by recent publications, have highlighted this connection as wishful thinking: utopian rather than a real application of direct democracy (Albertini & Andretta 2018, della Porta et al. 2017). Beyond these differences, in their public discourses both parties have politicized the opposition citizen vs establishment (described as a closed caste) and, consequently, have laid emphasis on the need to renew the entire political class by both getting rid of corrupted elites and called for major involvement of the common people in political decision-making (Montesanti & Tarditi 2017, p. 263).

Indeed both parties have been associated with the variant of “inclusive” Populism (Mudde & Kaltwasser 2012) given their accent to the will of re-connecting ordinary people to the politics and the almost substantial lack of exclusive rhetoric against immigrants or minorities (Montesanti &Tarditi 2017,Vittori 2017, Mosca 2015a, b, Augustin & Briziarelli 2018)1.

Further elements in the case selection shall be detailed below, with elements referred to both pragmatic and methodological argumentations.

The following section resumes the analysis of why the study of populism has always been present in the scholarship of political science, before turning to delimiting the boundaries of populism as a concept.

1 In Five Star Movement, the issue of immigration has still susceptible to interpretations. Grillo in several posts has attacked immigrants but he the base has voted agains his proposals of making a crime to pursue seriously the “illegal immigration”.

7

The history of populism: from its origins toward a fourth wave of contemporary politics.

Beyond the challenge of its conceptual delimitation, the extensive literature on populism has dealt with the phenomenon from various perspectives, ranging from its role in political communication (Mazzoleni et al. 2003, Aalberg et al.2017) to the broader issue of its relationship with democracy (Meny & Surel 2002, Albertazzi & Macdonnell 2008, Canovan 1999, Mudde & Kaltwasser 2013, Abts & Rummens 2007). In the last year, two handbooks dealing with Populism have been published, the first one by Oxford University Press and edited by Rovira Kaltwasser, Taggart, Ochoa Espejo and Ostiguy (2017), the second one by Nomos and edited by Heinish, Hotz-Bacha and Mazzoleni (2017). However, this topic of research is far from being new: interest in populism can be traced back in the 19th century. To this point, Guy Hermet (2013) traced a chronological history, identifying three important ancestors:

1) the “Narodnik movement” in Russia, originated in the Tsarist Empire between 1840 and 880;

2) French “Boulangism”, with its patriotic and slightly authoritarian features, during the 3rd Republic;

3) The “People’s Party” in U.S.A, originated from a revolt of American farmers in 1890. The “Narodnik” movement was composed mainly of intellectuals who exalted the virtues of the people and preached a sort of “Rural Socialism” (Mastropaolo 2005 p. 50). It was a movement rooted in tradition, preaching an opposition to progress. Boulangism was born in France, an industrial country which had experienced the shock of revolution and the rise of Napoleon in the late 18th century. The movement agitated for a plebiscitary democracy in order to build a strong state, legitimized by a universal suffrage. Last but not least, the American “People’s Party” represented the farmers of Southern and Mid-west America mobilized against the political and economic elite of Washington.

In all three ancestors of populism, it is possible to determine the importance of the appeal to the “people” framed antagonistically against groups of élites in an attempt to exercise legitimate rule. These pioneering experiences provided some of the coordinates of the complex phenomenon of populism in the 20th century. In that period, populism found a fertile breeding ground in Latin America with Getulio Vargas in Brazil and Juan Domingo Peron in Argentina. In both cases, as Zanatta (2014) rightly stresses, these movements can be considered “populist” despite their authoritarian features. Adored by the masses, Peron and Vargas refused to collocate themselves within the traditional ideological left-right spectrum and promoted paternalistic policies of

8 redistribution. They decried the dominant oligarchies (i.e. the aristocratic landowners) and identified themselves as the unique bearers of the interest of the people. Essentialy, they relied on a mix between authoritarianism and democracy, with a constant appeal to the people against corrupted elites: a claim for the restoration of the volonté genérale without a clear ideological background.

Beyond the present historical delimitation, populism has continued to be one of the trickiest phenomena of the last century, susceptible to various interpretations. On this point, worth mentionining is the so-called ‘Cinderella complex’, a line of analysis used by different scholars to underline the theoretical complexity of phenomenon and its empirical challenges.2 For instance, there

has been – and is still – a certain fuzziness when dealing with populism, used by some authors as synonym of radical right tout court. The thesis strongly aligns with Mudde’s analysis (2004), which has convincingly demonstrated the difference between radicalism and extremism, as well as the minimal definition of populism. In a more recent analysis, Mudde and Kaltwasser (2012) have identified the two main faces of populism in relation to the focus on the dyad inclusion vs. exclusion. The thesis shall return to these elements in the following pages. For now, for better framing of the debate, it is useful to quote Von Beyme (1988) whos has singled out three important waves of populisms with focus on radical right.

The German scholar associates the first wave of populism with the post-fascism period in Italy and Germany and, among the most relevant parties, includes “Uomo Qualunque”, a party set up by Guglielmo Giannini, an Italian comedian. The party received more than 5% of the votes at the elections of the constitutional assembly of 1946 with a self-telling slogan: “Down with everybody”, on open claim for wiping out the entire political class. The second phase was epitomized by the so-called Poujadist model, by an increasing number of parties across Scandinavia that wanted to revolt against high taxation, and by critical stances to the welfare state. In von Beyme’s reading, this wave was more economically oriented. Among the main representatives, there are the Poujadiste party (l'Union de défense des commerçants et artisans UDCA) in France and the Progress Parties in Denmark and Norway (von Beyme 1988 p. 10). These parties implicitly shared part of their main stances with the American “People’s Party”: a clear wariness against the national state, seen as guilty of demanding too taxes and not pursuing the people’s interests. From the 1980s, the third wave of populism was (von Beyme 1988 p.11) caused by unemployment and xenophobia at the end of a long prosperous period.An important example was the National Front in France, which tried to combine elements of welfare chauvinism with a nativist attitude against migrants and supranational elites.

2 Isaiah Berlin claimed in 1967 that “although somewhere there exists a shoe representing populism, there is no foot to be found which fits the shoe”5. In Berlin’s metaphor, the prince (in our case the analysts and scholars), search populism with the shoe in hand, but the search for this platonic concept is futile. He will never find what he searches for6.

9 In parallel, in the 1990s populist parties found a fertile breeding ground among liberal, central and/or ethno-regionalist parties. The Italian case, for instance, witnessed the success of Forza Italia and the Northern League (Tarchi 2015) two populist parties with consolidated governmental experience. In other countries, such as France, Norway, and Denmark, right wing populism remained relatively constant, although not with the same impact in terms of Sartorian relevance (1976). In France, the National Front obtained relevant electoral results only in the Presidential elections of recent decades (i.e. in the 2002 and 2017 presidential elections, with Jean Marie Le Pen and, then, his daughter, Marine Le Pen). Worth noting that in Parliament FN got some seats with the proportional reforms of 1986 (35 seats); afterwards, with the return to a majoritarian system, its presence was almost insignificant (1 in 1988 and 1997, 0 in 1993, 2002, and 2007 , 2 in 2012 and 8 in 2017). Over recent decades, Northern European populist parties have strengthened their position in the system, as illustrated by their constant presence in parliament. In this context, it is worth mentioning the “genetic” mutation of the Swiss UDC (Democratic Union of the Centre); under the leadership of C. Blocher the party shifted from a traditional agrarianism to populism. In various other countries where populism used to be absent, populist forces have started to multiply and gained increased electoral visibility. This is the case in the Netherlands with the PVV, led by Geert Wilders, which since 2016 has attracted on average around 10% of the vote, and in Greece with new actors like Laos3.

Before the austerity crisis, European populism was mostly rooted on the right of the political spectrum, with relatively few exceptions (i.e. the Dutch Socialist Party Left, the (East) German Party of Democratic Socialism), as Mudde notes These left-wing populist parties combine a democratic socialist ideology with a strong populist discourse. They present themselves no longer as the vanguard of the proletariat, but as the vox populi (voice of the people) (Mudde 2004 p. 549-550).

This scenario was susceptible to further change after the economic crisis of 2008 where traditional parties increasingly faced a crisis of legitimization. What can be called a fourth wave of populism rose across the continent. Targeting political elites for their incompetence in handling the crisis, populist parties have become much more relevant and have taken office in countries like Greece, Hungary (Batory 2015), and Switzerland. Germany, a country almost immune from this challenge, has experienced “Alternative for Germany”, a party set up by a liberal professor of economics, which has become right-wing populist and is currently the opposition to the Merkel government. It is also worth noting the rise of UKIP in Great Britain and its relevance in setting the agenda for leaving the European Union as well its pivotal role in campaigning for the “leave” in the

3 Anyway, in this country, populism had already had breeding ground with the rise of the Pasok led by Papandreou (1976) (see Pappas 2014)- (Pappas 2014)

10 Brexit vote. In Spain, before the huge economic crisis no populist radical right had emerged (Alonso & Kaltwasser 2014) but as a consequence of austerity policies populism grew up as well, in this specific case the left-wing variant (Podemos). In Greece, Syriza, a left-wing populist party took office, while in Italy the Five Star Movement, considered a pure form of populist party (Tarchi 2015) achieved amazing success, culminating in its entrance into government in June 2018, accompanied by the Norther League, another populist right-wing party.

In order to explain the spread of populism in the 21st century across Europe, different demand and supply-based determinants have been identified. Golder (2016) has provided an extremely useful literature review on this topic. In brief, he has connected the widespread distrust towards mainstream parties (i.e. in particular with regard to their capacity for solving the economic crisis) with increased demands for change. When the supply side is closed, high demand does not produce success (Golder 2016, p. 490). In fact, when a high percentage of citizens’ discontents are not met with an adequate supply side of parties and movements that channel these demands into political representation, this kind of discontent does not trigger any change. Vice versa, when the supply side, with new parties like the populist ones, is open, citizens have opportunity to express their discontent. Thus, the rise of the populist actors in Italy and Spain, but also in Countries like Germany (Alternative for Germany) and Greece (Syriza-Anel), can be explained by the interaction between supply and demand.

All in all, according to the literature, the most recent successes of populist parties across Europe can be connected to both demand and supply side explanations. Western Europe polities are facing a democratic malaise caused mostly by the economic crisis, as witnessed by the increased unemployment rate and job market insecurity (Della Porta et al. 2017). This economic context has facilitated the crisis of parties as intermediaries (Morlino & Raniolo 2017); in fact, the volatility in voting behavior has increased massively (Chiaramonte & Emanuele 2015).

All these phenomena have created new demand from citizens and challenged the traditional channels of representation – the political parties. Thus, populists are successful because they express a critique of the current frame of democracy; in particular, they are at odds with the intermediary structures by preaching the direct involvement of the citizens.

Investigating to what extent Podemos and the Five Star Movement try to pursue this critique of democracy and renew the system with new anti-intermediation tools in practice will be the focus of the thesis. The next paragraph focusses in detail on what the main characteristics of populism are by explicating the conceptual boundaries of this “thin” ideology. In this way, the research can be based on a solid understanding of such a phenomenon.

11

The elements of populism: delimitating the boundaries

As stressed above, populism has been conceptualized in several ways by scholars. The present research follows the “thin-centred ideology” approach, according to which the definition of populism is the following (Mudde 2004, p. 543) a thin-centred ideology in which society is divided in two homogeneous and antagonistic group, the pure people and the corrupt elite and politics must be the expression of the general will. This conceptualization relies on the “ideational approach”, which considers populism to be essentially a set of ideas. Nevertheless, scholars who agree on the fundamental elements of the ideational approach (a Manichean vision of politics as people vs. elite and stressing the importance of the general will) are divided on the genus of the phenomenon (Mudde & Kaltwasser 2018, p. 3). In the most recent studies, the terms utilized are “discourse” (Stavrakakis & Katsembekis 2015), “Frame” (Aslanidis 2016), “moralistic imagination” (Mueller 2016), “style” (Moffit 2016), and “worldview” (Hawkins 2010) (see Mudde & Kaltwasser 2018, p. 3).

According to Mudde & Kaltwasser (2018, p. 3), all these definitions have minor differences that are irrelevant to many research questions. The only two conceptualizations far away from the ideological perspectives are the political-strategic approach (Weyland, 2017), which, as seen in the first pages of this thesis, is the most criticized in the literature, and the socio-cultural approach (Ostiguy 2017). For the latter, populism is a folkloristic style (Ostiguy 2017, quoted in Mudde & Kaltwasser 2018, p. 6) used by leaders who behave improperly and break taboos with the aim of building a connection with (certain segments of the electorate. The problem with this conceptualization is that empirically populism has also experienced leaders who did not behave improperly (see Fortuyn in Holland and Iglesias in Spain: Mudde & Kaltwasser 2018, p. 6). By the same token, focusing exclusively on the behavior of the leader is a tendency disconfirmed by the empirical cases. In fact, not all populist leaders have been charismatic (see Tea Party in Mudde & Kaltwasser 2018) and, as illustrated convincingly by Hawkins (2010) in his monography on Chavismo, the presence of charismatic leadership is more a facilitator than a property of populism.

It is worth mentioning briefly what a ‘thin-centred ideology’ means. Essentially, populist actors have a thin core (anti-elitism, people-centrism and claiming to embody the general will) that is usually accompanied by other ideological stances. According to Zulianello (2017b), the difference between a complete ideology, such as liberalism or socialism, and populism is that the former provide answers to all the main issues in a society, while populism does not. Zulianello (2017b) specifies that “people” and “elites” are empty signifiers that can assume different forms accordingly to the context and to the other ideologies. For example, in right-wing exclusive populist parties, “the pure people” is associated with an exclusive vision of the polity (nativist ideology), while in left-wing variants,

12 inclusive populist leaders make reference to socialism, and the “pure people” represents all the socioeconomic underdogs (Mudde & Kaltwasser 2018, p. 4). As recent scholarship testifies (Mudde 2004, Mudde & Kaltwasser 2012, 2013, Zulianello 2017b), the skill of populist actors is to combine their “mindset” with a diverse range of “host ideologies” including agrarianism, nationalism, neoliberalism, and socialism (Mudde & Rovira Kaltwasser 2018, p. 4). As empty signifiers, even the “elites” can refer to different “enemies” like “political class”, “Economic powers”, the “intellectuals”, “and international organizations”. These subjects are considered as “evil” who plot against the “people”, an entity always considered homogeneous, pure, honest and morally superior (Zulianello 2017b).

All in all, the research considers all the parties that use this Manichean frame towards politics and society to be populists. Accordingly, a populist party preaches a political discourse of strong antagonism and identifies clear enemies – the political and/or economic elites. At the same time, populists make an appeal to the people, considered as homogenous, pure and uncorrupted. Another crucial variable, which will be deepened in the next paragraph, is the self-praising of the populist parties as the unique bearer of the general will that has been jeopardized by evil elites. Thus, populism has an ambivalent relationship with democracy: on the one side, it radically defends the principle of the “general will” and “power of the people”, but on the other it is at odds with liberal democracy and its systems of checks and balances, which populism sees as ways of limiting the “will” of the people. All these aspects are the topic of the paragraphs following, which aim to clarify the approach of the research and the specific environment in which the present thesis aims to contribute. For the time being, a final mention should be devoted to the role of the leadership in populist actors.

According to the “ideational approach”, a charismatic leadership is not an essential characteristic for being populist. However, regarding the case studies under analysis (Podemos and Five Star Movement), the extent to which their leaders are presented as “underdogs”, especially in the media, is a variable that can facilitate the rise of a populist party (Hawkins 2010). For this reason, and given their newness in the respective political landscapes, in the second chapter,, there will be a focus on the role of the leaders.

Finally, the concept of populism should consider the differences between its “exclusive” and “inclusive” variants (Mudde & Kaltwasser 2013, Filc 2015). Inclusive populists preach the integration of the excluded of the polities enlarging the boundaries of democracy (Filc 2015 p. 266). These parties become themselves the tools for the excluded to go back in the politics. They are their spokepersons and, in this way, they can restore the will of the people (Filc 2015, Mudde & Kaltwasser 2013). On the contrary, exclusive populism stresses the ethnic homogeinity of a certain people, in the words of Filc (2015 p. 266) promotes the belief that states should be inhabited exclusively by members

13 of the nation widely held to be the native group, and that non-native persons and ideas represent a threat. Both variants are populists in the terms of which they want to promote the interests of the common people, but in the exclusive variant this “people” is circumscribed to a particular ethnicity while in the inclusive variants there are not such differences. The case studies of the thesis (Podemos and Five Star Movement) have stressed several times the importance of the inclusion of all the citizens without discrimination in the politics and for this reason their populist “thin ideology” can be analysed under this perspective.

Framing populism’s current challenge to democracy and the research approach

1. Focus of the research

Having introduced the context of reference, a question emerges: why does populism regularly return in politics? The current research shares a basic assumption expressed in the literature: populism is a by-effect of situations of crisis. One caveat must be mentioned. Since Ancient Greece, traditional political theory has stressed that democracy is “inconceivable” without crisis (Merkel 2014b p. 11); this means that crisis is intrinsic to politics, given that it is a complex system based on compromise4 Putting together “crisis” and populism might be misleading if one takes into account how conceptually slippery the concept of “crisis” and its recurrence in democratic systems can be. Moreover, as Tormey (2015p. 15) brilliantly states, at some level there is always a crisis of representation or a crisis of democracy. It is in the DNA of democracies that there is a continual shortfall between what politicians promise and what they deliver, between what theorists of democracy think democracy should be and how it turns out-leading to disappointment.

By focusing especially on what the literature has claimed about the relation between the crisis of representation and the birth and proliferation of populism, this phenomenon has been described as a consequence of a multilevel crisis (political, economic, cultural, social and/or systemic) (Taggart 2002, Meny and Surel 2002, Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017). Similar conclusions are found in Canovan (1999); she also pinpoints how populism exploits the tension between the two faces of democracy: the pragmatic one (where institutions mediate conflicts through acting as intermediators for the demands from the people) and the redemptive one (so called “government of the people, by the people, for the people”) (Canovan 1999, p.10). Within this context, populists advocate being the “true democrats” and decry institutions as intermediaries that are guilty of not pursuing the interests of the

14 real/genuine people. According to Canovan (1999), populism can function as corrective to democracy if populist approach to politics as a redemptive mission. The corrective function of populism to democracy is mostly linked to the inclusive type of populism (Mudde, Kaltwasser, 2012). The cases under consideration: Podemos and Five Star Movement have several times promoted the inclusive (Filc 2015) and redemptive (Canovan 1999) vision of democracy, as it will be underlined in the following paragraphs.

During periods of crisis, political parties are considered to carry key responsibility. The traditional offer of parties is not credible anymore, while emerging populist parties can present themselves as solid alternatives, especially if they are new political actors and do not have experience in government. They exhibit a double “newness”: they are the only parties that listen to the demands and the complaining of the citizens and they present themselves as the only ones that can and know how to implement these inputs into policies. In this perspective, the economic crisis of 2008 and the correlated crisis of political representation, which has rapidly taken on political and social dimensions, especially as far as the European context is concerned, has triggered a new wave of populism in the old continent.

Exclusive populist actors have taken advantage of the immigration crisis that occurred in Europe in 2015 by accusing the European Union and the incumbent government of endangering the security of “ordinary people”. On the other side, inclusive populists like Podemos in Spain, Syriza in Greece and 5SM in Italy in its early phase, have accused the national political elites of no longer representing the will of the citizen and of being responsible for the economic disaster. Essentially, populism finds a breeding ground when situations of crisis becomes systematic: the political parties do not manage to cope with the demands of citizens, the security of the polity is perceived as endangered, the overall system of delegation typical of liberal and representative democracy is considered as corrupted.

It is important to mention that in the following pages this thesis refers to political parties as the agents through which populist ideas and leaders find organized support to achieve power. Beyond this assumption, based on the classic definition of parties provided by Schattschneider, it is important to emphasise that these organised attempts to get to power have become increasingly relevant, in particular regarding the traditional Sartorian understanding of relevance in a party system (1976). Not only are populists able to shape the agenda from their position in parliament toward other parties but they have also had access to governmental offices in countries such as Italy, Hungary, Greece, Switzerland and Austria (see Albertazzi & MacDonnell 2014, and Kaltwasser & Taggart 2016, Zulianello 2019a).

15 In the present research, as already anticipated, the focus will be on intra-party organization, a dimension relatively understudied by the literature on populist parties (Heinish & Mazzoleni 2016, Zaslove 2008, Hawkins 2010). As we will see in detail in this dissertation, this might look like a strange choice. In fact, populist parties blame intermediary structures, such as traditional parties, and they advocate a non-intermediated translation of the general will into policy. Traditional political parties filter and adjust the inputs from citizens, delegate representatives to institutions and progressively detach from their communities of origin. Or at least this is the common representation of traditional politics. On this ground, this dissertation aims to assess how populist parties conciliate their ideological background (anti-partism) with the practice of representative democracy. In other words, how can the democracy of populism be defined and what are the differences between traditional representative democracy and the way populist parties organize themselves?

Populist parties can be defined as radical promoters of a radical change of democracy within the limits of democratic rules. But what is radicalism? What is the connection of populism with extremism? Following Mudde (2010, p. 1172), extremism is the antithesis of democracy, since it rejects the one person one vote system and fully denies the validity of representative democracy. On the contrary, radicalism accepts and promotes the working of democracy, including the system of universal suffrage, and endorses the “government of the people” (Mudde 2010 p. 1172). Nevertheless, radicalism denies pluralism and preaches a monistic vision of the people: The core of radicalism is monism, i.e. the tendency to treat cleavages and ambivalence as illegitimate (Mudde 2010 p. 1169) Populists are radical because they stress the importance of the general will and the centrality of the people as the unique source of legitimization. Indeed, they do so by mobilizing the excluded within society to guarantee their integration into the political system and by giving voice to people who are not represented by the current elites (Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017 p. 83).

Populism also challenges the mechanism of liberal democracy, based on independent unelected bodies. The populist phenomenon can use the idea and praxis of majority rule to circumvent minority rights. (Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017 p. 83). Thus, populism could have a positive and/or a negative impact on democracy.

In conclusion, populist parties do not blame democracy in itself, but the distortions they say stem from the way (representative) democracy is captured by élites. Or, in Canovan’s (1999) words, they criticize the pragmatic face of liberal democracy. More specifically, populist parties raise their voice against the way in which the people has been set aside from the functioning of democracy, or more specifically from democracy that is increasingly transformed into oligarchy. In their view, traditional political parties no longer manage to gather citizens’ demands and transform them into public policy. This distortion, according to populists, is due to the oligarchic behavior of the élites in

16 power and to growing economic interdependence and the increased relevance of powerful supranational institutions (i.e. European Union, the IMF, the WB, etc.). Therefore, their aim can be conducted to the restoration of the “redemptive vision” of democracy (Canovan 1999)

After noting the criticisms of democracy that populists advance, it is worth mentioning what the present research aims to analyse. The thesis inserts itself into the new area of study focusing on the question of to what extent populism can have a positive or negative impact on the functioning of democracy (Mudde & Kaltwasser 2012, Kaltwasser 2012). This thesis will deal with innovative aspects in terms of participation: to what extent do populist parties “reconnect” the ordinary people – betrayed by the political elites – with politics. Within this broad area, the novelty of the thesis lies more specifically in identifying the potential relation between the way populist parties refer to democracy and the practice of democracy in relation to the way they organize themselves. In order to perform such an analysis, the following lines will define the field of the research: party organization and its relevance for understanding the functioning of democracy.

2. Relevance of organization in party agencies

At a general level, party organizations can be seen as the dependent variable, influenced by different elements of the political system within which they act. The literature has developed various lines of analysis by focusing on the impact of electoral law (Morgendsten 2001), the form of government (Langston 2006) or the different forms of party regulation on the way parties organise (Whiteley 2011).

With these contextual elements defined, it is important to say that the literature generally assesses parties as active agents, capable of navigating environmental constraints and influencing their performance through their internal structures (Panebianco 1982). Thus, parties can adopt different types of organization. The theoretical debate on the evolution from mass party legacy (Duverger 1951) to contemporary models of electoral parties (see Kirckhemeir 1966, Panebianco 1982, Katz & Mair 1995; Raniolo 2013) has stressed a shift from a well-grounded, organised parties in the territory of reference to parties based on flexible organization, increasingly dependent on their leadership and public funding. Consequently, contemporary parties place less relevance on their organization on the ground and focus instead on the public and/or central offices (Katz & Mair 1995). If this can be considered true for traditional/mainstream parties5, so-called new parties have started

5 According to Akerman, de Lange and Rooduijn (2016), mainstream are those parties like liberal, Christian democrats and social-democrats that position themselves at the centre on the classic left-right scale. In this sense, the term ‘mainstream parties’ is often used in contrast to ‘radical parties’ and ‘niche parties’ (including radical right-wing populist parties, green parties, left libertarian parties and regionalist parties that exploit programmatic niches).

17 to challenge this conventional wisdom and promote a model in which members have increased power. This is the case of the Greens (see Poguntke 1993), the Pirates (Bolleyer at al. 2015) and, in more recent times, the pro-democracy seeking parties (Morlino & Raniolo 2017) such as the case studies under consideration: Podemos and the Five Star Movement. In these examples, intra-party organization also reflects these parties’ claims for democracy and can be a way of introducing certain democratic innovations.

In the specific case of the Greens and the Pirates, the novelty of the party echoed an emphasis on its claim to bring citizens back into politics. However, organization structures were sometimes problematic for maintaining a clear consensus in the long term. All in all, it looks like new and old parties remain attached – to different extents, with different intensities and models of reference – to formalized party organizations because the empirical evidence shows that organization still matters. On this point, scholars like Tavits (2013) have demonstrated the fundamental importance of having a well-strong and institutionalized organization Political Parties that invest in strong party organizations (including cultivating large membership, developing an extensive network of visible branch offices, and building professional, specialized and permanent central office staff) are more likely to succeed electorally, survive as significant players in the electoral arena and behave cohesively in the parliament(Tavits 2013 p. 2). Party organization has also been connected with an impact in terms of electoral volatility (Gherghina 2015). The most recent literature in party politics has gathered increased evidence demonstrating that party organization is still fundamental for a party’s survival and institutionalization over time (Borz and Janda 2018). Very few parties contradict this development, though it is the case for so-called memberless parties with highly fluid organizational infrastructures6 . Similarly, the literature has identified a low level of interest in party organization in the early 1990s in post-communist states (van Biezen 2003), although partially overcome (Tavits 2013, Gherghina 2014).

Given that party organization matters for a party’s survival and for the party’s chances of gaining power, new parties like the Greens and the Pirates have unsurprisingly adapted to existing institutions, adopting more or less structured forms of organization. Nevertheless, their organizations have been depicted as fundamentally different from those of traditional parties. New parties have challenged the traditional party menu by trying to give more power to their members and by fostering internal democracy (e.g. the Greens and the Pirates; Poguntke 1987, Bolleyer et al. 2005). However, both new and old parties aim to guarantee their survival over time. These considerations make the

Mainstream are also those ones loyal to the political system and to its values, and show commitment to the principles of liberal democracy.

6 see Mazzoleni & Voerman 2016 for the examples of the Freedom Party in the Netherlands or the Lega dei Ticinesi in Switzerland

18 importance of institutionalization clear and suggest that even parties without the clear aim of becoming strongly organized at their breakthrough need to arrange and change in order to remain on the political scene.

Returning to populist parties, their critique of representative democracy is illustrated by their reticence in adopting the traditional appellation of ‘party’. Instead they prefer alternative labels which either echo the community without divisions in the case of ‘front’, or their dynamicity, such as ‘movement’, or simply verbs like ‘we can’. Still, as Meny and Surel (2002) rightly observe, these parties organize and behave like parties. What is already known about party organization when it comes to populism?

3. Organization and populist parties: state of the art

The answer is relatively simple and straightforward: not very much. The topic of party organization in the field of populism studies is new. Heinish and Mazzoleni (2016) are among the few scholars to have conducted coherent research on the organizational features of populist parties. The conclusion of their edited volume is that populist parties are generally characterized by “charismatic leadership” and by a high of centralization in decision making, in terms of handling finances and candidate selection. Indeed, according to the various studies gathered in the 2016 volume, these parties – despite their anti-political ideological stances – are progressively moving towards an organizational normality (Heinish and Mazzoleni 2016 p. 238).

By looking more closely at the way these organizations function, Mazzoleni and Heinish observe that, except for the Northern League, radical right exclusive populist parties do not engage in new forms of connection between their members and the party élite (McDonnell & Vampa 2016). The most exciting finding of this research concerns the importance of the mass-party legacy in the organization. These parties deploy grassroots organizations, locally rooted within complex and durable organizations, featuring an institutionalized routine and a strongly centralized decision-making process. Finally, while mainstream parties face an ongoing haemorrhage of members, these parties illustrate a certain dynamism in attracting new activists. It looks like the legacy of mass parties still remains.

With regard to the left-wing inclusive cases of populism, della Porta et al. (2017) on Podemos, Five Star and Syriza and Hawkins (2010) monograph on Chavismo identify the movement structure as one of the possible key variables for the organization, linking them to the frame of “movement parties”. A mix between strong leadership at the top of the parties and a movement-based organization

19 in local circles has been revealed as a feature of left-wing inclusive populist parties which have arisen after the mobilization of social movements.

In relation to the core of the literature on party politics, Heinish and Mazzoleni’s volume, as well as the work of della Porta and Hawkins, partly clash with Mair’s thesis (2002) according to which the future of democracy is a democracy without parties (“partyless democracy”). More specifically, Mair (2002) has claimed that the role of parties has been overtaken by populist leaders who strive for a plebiscitarian idea of democracy, leaving the organizations with a minor/insignificant role. The outcome is a sort of leader-based democracy. This idea has been challenged before Heinish and Mazzoleni by other scholars, including Kriesi in his article “The Populist Challenge” (2014). In his piece, Kriesi(2014 p. 369) widens the perspective, arguing that the new populist challengers may be the driving forces of processes of restructuration and realignment of the party system (Kitschelt 2000; Kitschelt & Rehm 2012). One of the results of such processes of restructuration is that the new populist challengers within the party system may enter into government or support governments from the outside, as has happened repeatedly in Western Europe. So populist parties not only exist and are organized beyond their leaders, but they also play a role in the re-alignment of party systems (Zulianello 2019b). Moreover, they pose a challenge to the system outside the national political community by imposing the new cleavages of the “losers and winners” of globalization” (Kriesi et al. 2006, 2008, 2012).

Directly connected with the topic of party organization is the issue of party leadership. This is one of the aspects that has received more attention in the literature on populism, although, as rightly stressed by Mudde (Mudde & Kaltwasser 2017), in most cases the literature builds upon received wisdom. If populist leaders (and their charisma) are recognized as a main feature of populist parties (Mudde 2004, Hawkins 2010) it is important to note that the increased personalization of politics entails the entire political spectrum and not only populist parties (Pappas 2016, McDonnell 2015). As already stressed in the paragraphs above, the dimension of charismatic leadership has been a “facilitator” in the case of Chavez, while various populist parties have had periods with strong charismatic leaders and periods without. In order to shed light on this difficult relationship, this thesis will present a literature review which explains to what extent the leadership of Podemos and Five Star Movement have contributed to the success of these parties.

4. Aims and objectives of the research

Considering all the insights above and the challenge that populist parties represent to democracy, the present research aims to investigate what is the idea of democracy which populist

20 promote, and how is this idea put forward in strategies and practices of these parties, including the organization of populist parties, an aspect only partly analyzed by the literature. As a matter of fact, there has still been no in-depth investigation of how populists could offer a “disintermediation” of the democratic system. A good way to frame an analysis is by starting with an investigation of how populists organize beyond the leader, how they set up candidate selection and the consequent role of those elected inside and outside the party.

These aspects are the trickiest for the organization because they are linked to the main transformations of parties in recent years. According to Scarrow (2015), the way in which the system of elites is built inside a party can be a consequence of two different internal tendencies: the first is the presence of “leaderization and personalization” of the party, the second, by contrast, is the wish to set internal direct democracy. Usually, candidate selection is the best evidence for evaluating how much a party is moving towards internal democratization, or, on the contrary, to total personalization (Hazan & Rahat 2010). Regarding populism, these indicators can give also more insight in terms of the study of the phenomenon. In fact, we know that populist parties state their difference from the others. Considering this widely-agreed starting point: what is the role of the representatives in collecting demands from citizens and to what extent do they represent the people without intermediation in their organization? In direct connection to this question, how do they pursue the typical functions of a party, like the selection of elites?

The starting point of the research is the fact that populists’ stated mission is reconnecting the excluded of society to the political arena. Given that candidate selection is the common way of building elites in traditional parties, a focus on the mechanisms and format of this process facilitates an implicit comparison with a highly studied aspect in the traditional party-focused literature, but also allows us to bridge two literatures that have relatively few interconnections: party politics and populism. This is a point stressed by one of the most recent texts on the topic (Mazzoleni and Heinish 2016).

Are populist parties different from traditional parties when it comes to candidate selection? If yes, where does the difference lay, how can it be explained and what are the consequences? Similarly, if no difference can be found, why is this the case, and what are the consequences? Moreover, the building of party elites and their role vis-a-vis the base, both combines the critique of democracy as critique of the construction of traditional elite and can be as a proxy for the democratic change proposed by these parties. In this vein, the analysis here investigates not only the content of the rules of these processes but also how these rules are perceived by both members and party elites. Indeed, the process of input (who proposes the rules, how these rules are built and put into practice), the

21 process of selection (who can participate in the candidate selection, supply and demand) and who is recruited, who arrives to the institutions and what is his role in representing their base.

Finally, until now the state of the art about populism and organization has not used populism as independent variable in the shaping of the structure and especially in terms of expectations about the role of those people elected, and their selection; in general, little attention has been paid to the populist idea of representation and how this idea could be translated into the way these parties manage their processes of elite recruitment. The next paragraph of the thesis will clarify the research design.

Research design

1. Logic of the Research

This research will analyze two inclusive populist parties, Podemos and the Five Star Movement, using the comparative method. The logic of the research follows the case-oriented research. Case study in political science is used from the micro-level (e.g. studying individual political leaders or activists) to organization level and to the macro level (e.g. studying political systems). (Eckstein, 2000). Case study (Stake,:443-444) concentrates on experiential knowledge of the case and close attention to the influence of its social, political, and other contexts. Major responsibilities for the qualitative case study researcher are a) bounding the case, or conceptualizing the object of study; b) selecting phenomena, themes or issues c) seeking patterns of data to develop the issues d) triangulating key observations… e) selecting alternative interpretations to pursue and d) developing assertions or generalizations about the case (Stake: 449-450).

There are two main types of case studies: the within-case and between-case (or cross-case) studies. The aim of the within-case study is to describe in depth the single case under analysis. Between-case analysis is on the other hand, a method that facilitates the comparison of commonalities and differences in the events, activities, and processes; the units of analyses in case studies (Cruzes et al., 2015: p. 1638). The within-case study always precedes the cross-case study.

This choice of the case study makes it possible to go beyond descriptive statistical measures, towards an in-depth understanding of historical understanding and individual motivations (della Porta 2008 p. 202). Indeed, as a further justification of the case study-oriented as a logic of the research, Yin argues The case studies are preferred in examining contemporary events, but when the relevant behavior cannot be manipulated and that its major strength is its ability to deal with a full variety of evidence-documents, artifacts, interviews, and observations (Yin 1984 p.7-8). Case-oriented research can have positive and negative aspects. The advantages consist in going into depth

22 with the cases with a full explanation of the research questions connected to this; on the other hand, the negative aspects concern the limitation of the generalization given the small-n unit of analysis (della Porta 2008, p. 206). Incidentally, the relevance of these cases (Podemos and Five Star Movement) in the political context of Southern Europe as well as in the study of populism as general phenomenon makes clear that the insight from their analysis is a starting point for further research that could contribute explanations to other cases too (Della Porta 2008, p. 206). This point is particularly important for guaranteeing the external validity.

Regarding the internal validity, the analysis treats the two cases in the frame of the most similar system design (for the reasons behind this, see the following short paragraphs) in order to assess how similar conditions may generate different outcomes. As clearly stated by Della Porta (2008), the most similar system design makes it possible to get as much information as possible about the variation of the independent variables while they give less relevance to the control variables and to the factors in common that are not explanatory.

In comparative political science research, most similar systems design and most different systems design are commonly used as a research strategy. In this analysis, most similar systems design (MSSD) is chosen as a suitable strategy. In an ideal scenario, the MSSD would require that the compared cases are equal or similar on all variables except the one(s) referring to the phenomenon which the researcher is trying to explain (Anckar 2008 p. 389). However, this goal is difficult to achieve as (Anckar 2008 p. 390) there are a limited number of countries and it will never be possible to keep constant all potential explanatory factors. For this reason, there are two main ways to conduct MSSD: a stricter one, in which a researcher tries to match all the control variables except the independent one; and a looser one, in which a researcher tries to capture as many similar control variables as possible for the researched phenomenon, however not perfectly for all the variables (Anckar 2008 p. 390). In fact, most of the regional studies take the second, loose path in the MSSD (Anckar 2008 p. 390).

In this analysis, I have chosen Five Star Movement and Podemos as two cases that are chosen for the most similar systems design. The most similar system design can be both used on the systemic level (comparing countries as cases) and sub-systemic level (comparing actors, such as parties) (Anckar, 2008). These two levels do not necessarily exclude one another as sub-systemic levels are dependent on the systemic levels. For example, the way political parties organize or perform (sub-systemic level) also depends on the nature of the political system ((sub-systemic level). Countries that are geographically and culturally similar are often taken as cases in MSSD to make as many external variables as much as similar as possible (Anckar 2008 p- 393). The most similar systems design is used here primarily as a heuristic or a key in case selection. However, the methodological approach

23 is a qualitative one, not in a positivistic nature and not aiming to generalize inferences between variables.

Research Questions

The main goal of analysis in the thesis is exploratory and descriptive, and may offer understanding of analyzed processes, but will not offer causal explanations. Therefore, the thesis will not depart from hypotheses, but from research questions. Research questions in social research come in three main forms: what questions if the research goal is exploratory and descriptive, why questions if the goal is explanatory, and how questions if the goal of the research is in practical nature or demands some sort of intervention (Blaikie 2010). At this point, the general research question at the core of the thesis can be stated:

1) In what way do inclusive populist parties (Five Star Movement and Podemos) construct the idea of democracy?

1.a How is the populist dyad “people vs elite” reflected in the idea of democracy they “voice” in public debates and electoral campaigns?’

1.b How is the call for the restoration of a general will included in the idea of democracy of inclusive populist parties?

1.c How do inclusive populists conceptualize popular sovereignity in democracy? 1.d How do inclusive populists conceptualize collective decision making in democracy? 1.e What is the idea of democratic representation?

The first research question refers to great extent to the way populist frame the redemptive face of democracy (Canovan, 1999). Given populists’ support for the ‘general will’ and a wariness towards mainstream parties, which they consider to be corrupted and evil, these questions investigates to what extent the core ideological components of populism can be seen as reflecting in the organization of a populist party. This focus (ideology influences organization) has already been used by Poguntke (1987b) in his analysis of Green Parties and his attempt to assess how the participatory norms and aspirations of new politics groups will be reflected in the organisational structure (Poguntke 1987b p. 80). However, to our knowledge, this has not been applied in the case of populist parties. Considering the above, we assume not only that organization matters in terms of party politics but also that ideology is an important determinant of the way parties organize. This is definitively not

24 new in the literature and its origins can be traced back to Duverger’s seminal volume (1951). It is, however, relatively unclear how the populist (thin-centred) ideology can impact upon the organization of a party, in particular in relation to the core defining element of the vox populi.

In general, the literature has chronicled the ways in which mainstream parties have tried to open the mechanisms of leadership and candidate selection procedures (Hazan and rahat 2010, Cross & Katz 2013, Scarrow 2015, Gauja 2016, Scarrow, Webb & Poguntke 2017). The results of this process are ambiguous, and the findings are sometimes contradictory, since for some scholars this process has less to do with intra-party democracy, strictly understood, and more to do with the strengthening of the role of the elites (Cross & Katz 2013). At this point, the challenge of populist parties in their function as participatory tools can give new insights about what kind of representation they want, and to what extent primaries have different roles compared with their mainstream party counterparts in the respective countries. In any case, in order to be different from mainstream parties, and given their strong criticism of the political party structure, it is necessary to introduce a complementary research question:

2) What strategies do inclusive populist actors employ to include the populist idea of democracy in the system of representation?

2.a In what way is the populist idea of democracy expressed in candidate selection processes? 2.b In what way is the populist idea of democracy expressed in the behavior of elected populist representatives?

2.c In what way is the populist idea of democracy expressed in other aspects of party organization?

Let us now consider the propositions derived from each research question. The analysis will focus on the process of candidate selection and the role of mid-level elites by highlighting how this process originated and developed. This question is strictly connected with an important function of parties: the function of representation (Mair 2002). Given that populists aim to provide an immediate/full representation of the will of the people and they contest traditional arenas of intermediations such as parties and even parliaments, it is very important to assess how populist parties reconcile their understanding of representation without intermediation with the practice of party organization. In other words, we aim to investigate the existence of potentially new forms of relationship between delegates and the populist grassroots. Considering the above, this analysis has the aim of bridging the gap between the literature on party politics, the literature on populism and

25 populist parties and, more generally, discussions on the challenges of representation in current democracies.

2. Methodology and data collection

As far as the measures to be used to investigate the propositions are concerned, the inquiry shall be based on qualitative research, combining desk research (literature review, internal documents, and secondary literature) with semi-structured interviews with activists and elites. Relying on Yin (1984 p.89), the interviews are essential sources of case study information. The interviews will explore activists’ perceptions of democracy, the functioning of the circles and to what extent inclusive tools are conceived and put in practice. The two principal parameters to be investigated, as already stressed, are the primaries for candidate selection and the role of those elected. Another focus of the investigation deals with what kind of representation these parties set up. Interviews will also explore the changes in these dynamics. In this way, we can update the literature that has already dealt with the internal organization of Podemos and Five Star Movement. To conclude, the topics of the semi-structured interviews are threefold: perceptions about primaries (why such a tool was adopted and how it has been translated into reality), what precisely the roles of those elected in these parties are, and the perceptions of internal democracy inside and outside the party in the respective countries. During the interviews, conducted in Italian for 5SM and Spanish for Podemos, the research has applied the same macro-topics listed above in order to guarantee the comparability of data collected. The target respondents for 5SM were six members of the Italian Parliament (three from the House of Deputies and three Senators) and four activists, for a total of ten interviews. Among these data, three were collected through Skype calls held in April 2018, four in the fieldwork research in the Italian Parliament at the end of April 2018, and three by email between the months of May and June 2018. For Podemos, the interviewees were four members of the Congreso de los Diputados, four representatives of the central office and six activists from Barcelona and Madrid. In this case also, the collection of the data has followed a pragmatic logic: the fieldwork in May 2018 in the Spanish capital and in Barcelona made it possible to interview 11 people, while one interview was carried out via Skype in April 2018 and four were carried out by email. The research can also rely on a broad interview with an expert on Spanish politics dealing with the electoral contests and the politics of Spain and on a short interview with the secretary of Podemos. Finally, the data include a public speech held by the person currently responsible for Podemos’ communication.

26 Concerning the investigation of the dynamic at the local level, the research has also involved conducting two participant observations in 5SM and Podemos local circles, in one meeting of Meetup of Roma (end of April 2018) and in the Circle of Lavapiés (end of May 2018) respectively.

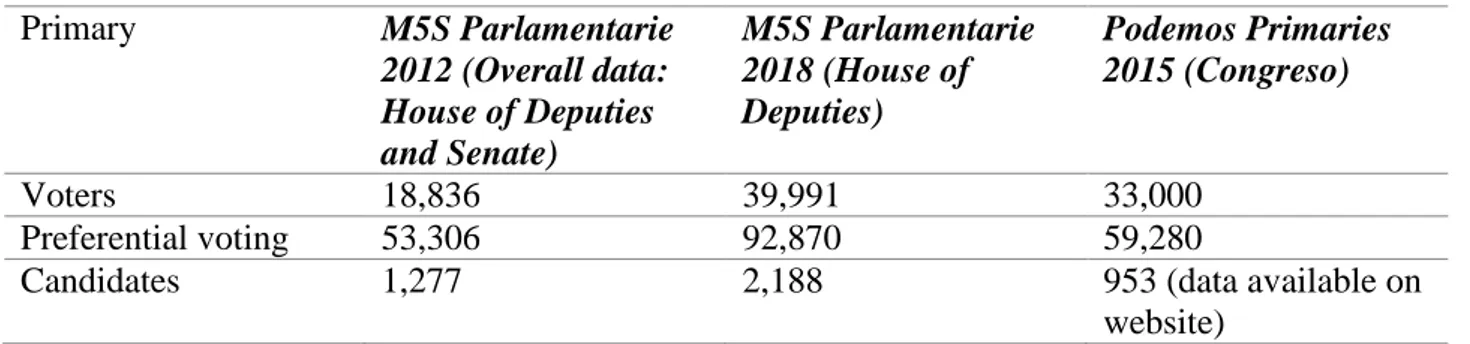

Regarding, finally, the period covered by the research, the analysis will focus on the Primaries set up by 5SM in 2012 and 2018, and by Podemos in 2015. The research fieldwork was carried out in the first months of 2018. In this way, the interviews not only cover the Primaries but also all the organizational and ideological developments of these parties from their beginning until June 2018.

It is important to stress limitations of these modes of data collection for the reliability of data. Although interviews are useful as comprehensive and wide source of data, which can inform the researcher about wider processes and other sources of data, their reliability can suffer because of informant’s bias, unreliable memory or misunderstanding (Yin, 2018). Additionally, in total seven interviews in this research were conducted via e-mail. This adds an additional challenge to reliability of the results. In interviews conducted via e-mail, researcher cannot establish rapport with the interviewee, cannot probe the answers, ask sub-questions and understand different meanings on what is being said with the help of verbal and visual cues. For this reason, interviews conducted via internet should be interpreted with caution (Yin, 2018). Participant observation has similar limitations as interviews, and it can offer biased view to the situation. Researcher can influence the situations which are being observed, and people can change their behavior because of the researcher’s presence (Yin, 2018). The solution for ensuring greater reliability of qualitative data is triangulation or using several sources of data to confirm certain findings in the study. This research uses several sources of data, interviews, participant observation and document analysis, but all these data can be biased to the narratives of two parties. However, the main goal of the research is to explore perceptions, ideology, strategies and narratives of these organizations and does not attempt to analyse “objective” data on the performance of these parties.

Having set out the logic of the research and the methodologies adopted, in the next short paragraph, the thesis will specify more in detail why are Podemos and the Five Star Movement selected in the frame of most similar system design.

3. Case Selection

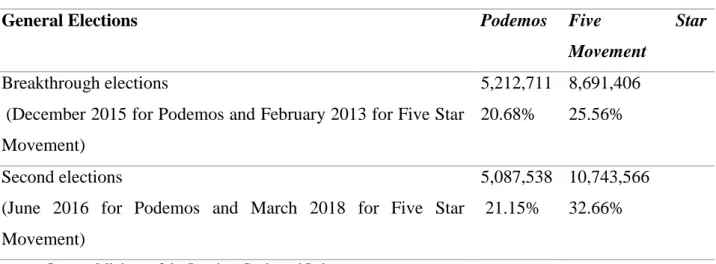

As for the cases taken in the analysis, Five Star Movement and Podemos can be put in the most similar design logic. As already stressed, populism has taken two main forms in Europe- right wing populists mostly in Western Europe and left or ambiguous in the European South (like Podemos, Syriza and M5S) (Ivaldi, Lanzone & Woods, 2017; Mazzolini & Borriello, 2018). Although Podemos