Introduction

Over the last few decades, policy makers have developed and formalised the religious tourism sector, to attract travellers to sacred sites and turn those sites into tourism destinations. Previously, travellers visited sacred places and sites out of a de-sire to come closer to spirituality and seek forgive-ness for sins and wrongdoing. That concept has changed and religious tourism has become a com-mercialised entity that allows travel agencies and policy makers to benefit from religious travellers.

The leading authors in religious tourism ac-cept that it plays a significant role in the develop-ment of tourism destinations (Timothy and Olsen, 2006; Raj and Griffin, 2015; Trono, 2015). The notion of travel as simply being for business or re-creation has been transformed by the individual traveller, who has been a contributing factor in the dynamic growth of tourism as a business model.

It is now widely accepted that, given the complexity of players and resources involved in the delivery of the religious tourist experience, more sophisticated skills and models are needed to manage sacred sites, cities and destinations. In particular, literature in tourism management identifies a shift towards the concept of govern-ance, considered a useful approach that facilitates an integrated decision making environment and

an emerging opportunity for local development (Laws et al., 2011).

This chapter will critically evaluate and dis-cuss a conceptual framework, exploring the issues and themes related to the so-called ‘destination governance’ concept. The aim is to demonstrate the validity of applying these methodological insights to religious tourism destinations, and in doing so, building a possible system of classifica-tion related to the diverse management and gov-ernance models.

A geographical perspective is chosen as a research strategy which emphasizes the recog-nition of the relationships among spatial pat-terns, processes and players that enable a place to be interpreted as a destination.

One of the most important problems in the effective functioning of religious tourism is the proper management of its tourist destinations. The key role can be attributed to the stake-holders who should act systematically to achieve a shared goal of tourism development of a place. It is clear that dealing with the complexity of players and resources that make up a territory is not a simple matter.

The chapter will focus on the main concepts and models of destination governance. Then, it will explore the role of destination governance in the management of religious tourism destinations.

Perspective for Religious Tourism

Destinations

Elisa Piva,

1Stefania Cerutti

2and Razaq Raj*

31

University of Eastern Piedmont, Novara, Italy;

2University of Eastern Piedmont,

Novara, Italy;

3Leeds Beckett University, Leeds, UK

Destination Management and

Destination Governance: Current

Issues and Models

Tourism is one of the largest industries in the world, supplying in recent years nearly 10% of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In many countries, tourism is the main source of income and employment. Travel and tourism employ more than 260 million people worldwide.

Among the issues that affect the tourism industry and the competitiveness of tourist des-tinations is the quality of their management processes (Ejarque, 2003; Franch, 2010; Kurleto, 2013; Mazurek, 2014). Destination manage-ment is increasingly competitive worldwide and, for this reason, we have witnessed a growing interest on the issues of tourist destinations and local tourist systems among scholars since the early 2000s (Bieger, 2000; Buhalis, 2000; Della Corte, 2000; Go and Govers, 2000; Pechlaner and Weiermair 2000; Weaver, 2000; Martini, 2002). In the background, tourism has con-tinued to evolve and has presented a series of trends over the past few years (Tamma, 2012) that include the following:

•

the role of local systems has become char-acterized by specific resources (natural, cul-tural, social, economic and productive) and these are recognized as competitive units;•

increased prominence in the role of newmedia and digital applications of interaction and communication (ICT), which has led to a widening of the subjects involved in distri-bution but, more significantly, has expanded the opportunities for participation of the users. In addition to being able to select, plan and book with greater autonomy, users can also become the protagonists in the produc-tion of informaproduc-tion and content (user gen-erated content);

•

An increase in the variety of forms ofproduction and organisation, in which new specialized activities, new businesses (small, medium and large), new institutional players (public–private partnerships) appear. These entities act in an increasingly cooperative and reticulated manner, requiring more articulated and complex strategic manage-ment skills than in the past;

•

the growth of experiential products, that convey knowledge, emotions and learningin various ways by combining aesthetic, educational, escapist and entertainment experiences. In these products, the cultural content, the language, the meanings and the ability to communicate and interact with tourists represent the ‘core’ element of the offered product.

To compete effectively, destinations have to de-liver wonderful experiences and excellent value to visitors. The business of tourism is complex and fragmented and from the time visitors arrive at the destination, until the point at which they leave, the quality of their experience is affected by many services and experiences, including a range of public and private services, commu-nity interactions, environment and hospitality ( UNWTO, 2007).

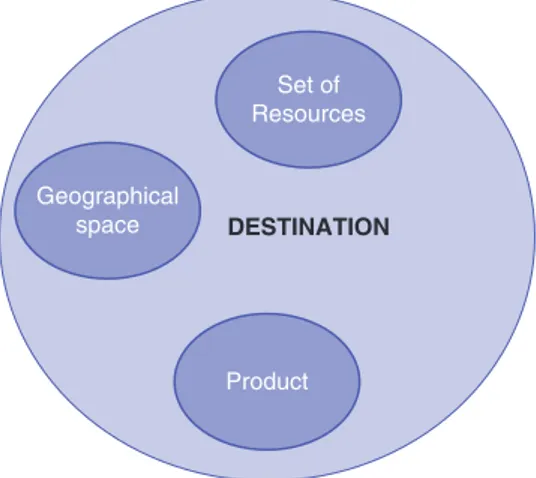

Destinations can be defined as well-delimited geographical areas (Hall, 2008) to which people travel and in which they choose to stay (Leiper, 2004). They contain all the facilities neces-sary for their success, including accommoda-tion, catering and entertainment/edutainment activities. As underlined by Tamma (2000) the concept of destination comprises three elements: the geographical space, a set of resources (facil-ities, activities and actors) and a product to be offered in a market (see Fig. 2.1). These various elements interact to create the particular nature of a place that is more than simply the sum of its components (Beeton, 2006).

Destinations can be also considered as com-petitive units in incoming tourism. They express

Geographical space Set of Resources Product DESTINATION

Fig. 2.1. The three elements of a destination. (Adapted from Tamma (2000).)

the need to define adequate policies and strat-egies and to conduct a consequent destination planning (Dredge and Jenkins, 2007; Manente, 2008; Dwyer, Čorak and Tomljenović, 2017). The role of destination management is, in fact, to manage and support the integration of different resources, activities and stakeholders through suitable policies and actions. It implies both governmental/decisional and functional compe-tences (planning, organisation and control of business activities) that should be generally per-formed by the public sector (Manente and Ming-hetti, 2006), which acquires a strategic role of direction and coordination of the numerous players involved in the local development of a territory. The territory in the field of destination management has to be conceived in the light of natural and man-made resources that charac-terize the local territory as well as the system of socio-cultural factors, developed within a spe-cific context thanks to the activation of inter- subjective relationships among different actors (Della Corte and Sciarelli, 2012).

In recent years, literature in tourism man-agement has identified a shift towards the concept of governance, where responsibility for policy making extends to both public and private sec-tors in joint action (Dredge, 2006) and where their relational dynamics support the creation of governance structures able to pool an innova-tive process for destination development (Della Corte et al., 2014). Based on Beritelli et al. (2007, p. 96) introducing the concept of governance in tourism destination means ‘setting and develop-ing rules for a policy as well as business strat-egies involving together all the institutions (municipalities and government districts) and their products and services supplier in order to create an effective strategy at all levels (plan-ning, promotion, monitoring and control)’.

According to Nordin and Svensson (2007), governance in tourism is an expression of the mutual dependency between governments and the private tourism industry, suggesting that governments and private actors should accept that a common interest, such as the develop-ment of a competitive and innovative destin-ation, cannot be achieved individually.

Currently, the theoretical foundations for destination governance present a rather indef-inite picture. There are still many issues and questions of governance to be defined, from the

attempt to define the term ‘destination govern-ance’ to the identification of types of governance models to research based on theories relating to various forms and problems of governance ( Pechlaner et al., 2010).

Governance encompasses the values, rules, institutions and processes through which public and private stakeholders seek to achieve com-mon objectives and make decisions. In recent years, as a result of the downsizing of govern-ment and an offsetting of responsibilities, the shift from government to governance has blurred the roles of public and private sectors in policy making (Gill and Williams, 2010). The degree to which local institutions and residents are en-gaged with or exercise any control over develop-ment will vary depending on the governance model of places and destinations. These models can be situated on a continuum ranging from community-focused to corporate-directed ex-tremes (Flagestad and Hope, 2001).

Corporate destinations are centrally man-aged and usually owned by one or several compan-ies or individuals that operate with entrepreneurial market-led initiatives. It represents a model of management in which the tourist offer is de-signed, handled and promoted by a key player that controls a significant part of the factors of attraction, the tourist facilities and infrastruc-tures. Therefore, the management of corporate destinations is centralised, hierarchical and inte-grated, taking advantage of the uniqueness of command, rapid decisions and a defined line of strategy (Tamma, 2012). With regard to organ-izational structures for strategy making, deci-sions are more likely to be taken by one or two agencies (corporate and/or government) that adopt a strong leadership role.

At the other extreme are the community destinations, which consist of a system of frag-mented services delivered by many companies and actors (Stokes, 2008). All of the services and elements that shape a tourism destination are influenced by the role of companies’ attitudes and their willingness to cooperate (Fyall et al., 2000; de Araujo and Bramwell, 2002). In these destinations, the ownership and the control of tourism resources and activities are spread among a multiplicity of actors, differently specialised, interdependent but autonomous. The organiza-tional framework of the community model consists of specialised individual independent

business units operating in a decentralized way and where no unit has any dominant adminis-trative power or dominant ownership within the destination. The strategic leadership is anchored in a stakeholder-oriented management, and is often subject to local government participation or influence (Flagestad and Hope, 2001).It is, therefore, clear how the role played by the actors that manage tourism destinations is critical (Kerr et al., 2001) as tourist destinations present increasingly complex challenges for manage-ment and tourist developmanage-ment (Howie, 2003).

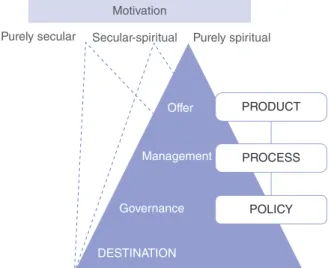

According to Tamma (2012), the develop-ment of a tourist offer stems from all the individ-ual choices and from the dynamic of relationships that are established between the various stake-holders of the territory. The combination of all these relationships gives birth to the destination governance structure (Fig. 2.2) in which the policies are defined, the process of management is set up and, subsequently, the tourism product is offered to the market.

As stated by Beritelli et al. (2007), in an en-vironment of strong international competition and rapidly changing customer needs, tourist destinations must continuously perform prod-uct, process and market innovation. New forms of integrated, centrally managed destinations challenge the business models of traditional, historically grown destinations driven by decen-tralized ownership. In this changing perspective, the previous model clearly shows a possible path towards a collaborative and sustainable local

development from the supply-side perspective. However, this model must inevitably interface with the dynamics of the demand to which the territories address their tourist products, intended as tourist experiences. According to Buhalis (2000), the destination is seen as a perceptual concept interpreted subjectively by consumers, depending on their travel itinerary, cultural background, purpose of visit, educa-tional level and personal experience. Therefore, this basic model should be adapted according to the different types of visitors and their motives, ensuring an adequate degree of flexibility.

Destination Governance: Insights

to the Religious Tourism Domain

Religion has always been one of the main motiv-ations for people to travel around the world. Des-pite the fact that in the western world there is a noticeable decrease in the importance of reli-gion and a growing numbers of atheists and ag-nostics, the number of tourists visiting religious sites has increased continuously (Griffin, 2007). According to Egresi et al. (2012), the reasons that motivate religious tourists are multifaceted and multilayered. Religious tourism embraces different types of visitors, ranging from those considered ‘spiritual travelers’ to the so-called ‘secular travelers’ (Smith, 1992; Di Giovine, 2016). Some researchers have shown that the number of tourists travelling exclusively for religious-related motivation is relatively low (Griffin, 2007; Rich-ards and Fernandes, 2007). Raj (2008) has highlighted how in recent years religious and pilgrimage sites have been transformed from sa-cred to secular destinations. As a matter of fact, many visitors are increasingly attracted to reli-gious places for historical and cultural purposes. For these reasons, religious tourism is be-coming more and more complex and not easily defined (Wright, 2008). According to Nieminen (2012) the terms religious tourism, pilgrimage tourism, cultural tourism, cultural heritage tourism and spiritual tourism are often used interchangeably. People can visit sacred places for faith and worship, for an interest in the his-tory and culture of religious sites, or simply to enjoy natural and cultural landscapes (Digance, 2006; Wong et al., 2013). In fact, religious tour-ism does not only involve a journey to a holy

Offer PRODUCT PROCESS POLICY Management Governance DESTINATION

Fig. 2.2. Destination governance: organisational structure and dynamic behaviour. (Adapted from Tamma (2012).)

place, but it can also represent one of the various form of leisure.

Religious destinations are increasingly pro-viding additional attractions to encourage pilgrims and tourists to visit such places. For example, today more and more people are travelling to sacred sites, taking part in religious festivals and events (Black-well, 2007). Events have always characterized the religious and devotional sphere, constituting a major attraction both for tourists with a pre-dominant spiritual motivation and for those more interested in the cultural aspect that under-lies the religious event (Cerutti and Piva, 2015).

It is, therefore, essential to understand the motivations and expectations that encourage tourists to visit a particular religious site, enab-ling local actors to manage their tourist offer suitably (Blackwell, 2007; Finney et al., 2009).

Since religious destinations attract visitors driven by widely differing motivations (Jackowski, 2000; Timothy and Olsen, 2006; Raj, 2012), the previous model (Fig. 2) should be adapted ac-cording to the different types of religious visitors and their motivations. Setting up a tourism offer also requires religious destinations to use a flex-ible approach oriented to the different market segments and the specific needs they express. The definition of the policies, the process of manage-ment and the tourist offer should be able to ad-dress these needs, creating different products for different tourist segments. In other words, the destination governance structure needs to be sensitive to the great variety of experiences visit-ors are seeking. As stated by Wiltshier and

Griffiths (2016, p. 3), ‘destinations reflect the liminal heart of the experience and should aim to match the sacred and secular purpose and the motivation to continue and co-create special ex-periences. Managing sites without considering the tourist experience causes dissatisfaction and loss of competitiveness (Levi and Kocher, 2009).

In light of this, a religious destination can be seen as a complex and dynamic system that involves several groups of stakeholders. It needs to adopt new governance models that match the demand motives with the offer (Fig. 2.3).

According to Smith (1992) ‘purely spirit-ual’ and ‘purely secular’ represent the two polar-ities in the range of motivations for undertaking a religious travel or visiting a sacred site. On this continuum there is a wide variety of other mo-tives that, combining spiritual and secular ex-periences, comprehend the different forms of religious tourism. These positions reflect the mul-tiple and changing motivations of the traveller whose interests and activities may switch from tourism to pilgrimage, and vice versa, without the individual even being aware of the change (Collins-Kreiner 2009). Indeed, Timothy and Olsen (2006) define religious tourists as ‘those where the impetus to travel combines both religious (dominant) and secular (secondary) motives’. For example, according to Swatos (2006) and Egresi (2012), Rome is visited primarily by pilgrims and religious tourists for its sacred heritage sites and to perform religious rituals. Nevertheless, these travellers often decide to visit non-religious places to enjoy their free time in the city.

Offer PRODUCT

Purely secular Secular-spiritual Purely spiritual Motivation PROCESS POLICY Management Governance DESTINATION

Fig. 2.3. Destination governance: a flexible approach for religious tourist offer.

In brief, the destination governance process is based on the encounter between tourist offer and demand, as it is only from the interaction with the needs and motivations of the visitors that satisfying tourism products and experiences can be created. However, this work intends to point out how the theme of governance should not only be related to the management of reli-gious destinations as an expression of tourism products, but it also has to take into account both the places where the latter are consumed and the spatial relationships between the actors involved in their management. This means adopting a geographical perspective that sees the territory not only as a passive supporter but also as an active part (Dematteis and Governa, 2005), and thus as an expression of interactions led by the various stakeholders. In recent years, other attempts to study the spatial characteris-tics of religious destinations have been made (Park, 2004; Collins-Kreiner, 2009; Olsen, 2013).

Within the scientific literature, a unique reference model for the governance of religious destinations has not yet emerged, and few em-pirical studies exist as to the operational reality of governance (Beritelli et al., 2007). It is there-fore necessary to understand how governance is produced, who leads the management process of religious destinations and what are the roles of the different stakeholders in this process.

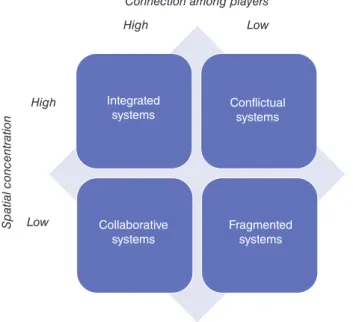

Among the various proposed classifications, this study tries to contribute to the debate identi-fying a possible taxonomy for the governance of religious tourist destinations that stems from the analysis of the relationship between two vari-ables. As an illustration, exemplar case studies are provided in order to give empirical evidence for this model.

This relationship is represented by a matrix diagram, ‘an extremely useful technique to or-ganise and structure information in scientific analyses and diagnoses’ (Santo, 2012, p. 489). Matrix diagrams are frequently used in tourism when it comes to planning and managing tour-ist destinations of various types (Pearce, 2012). As shown in Fig. 2.4, the vertical axis reflects the spatial concentration of religious destinations, while the horizontal axis represents the current level of connection among their actors.

The spatiality of religious destinations, intended as the concentration and dispersion patterns, represents a significant issue for the development of tourism policies and sustainable processes of management (Lau and Koo, 2017). Spatial concentration is used to explain whether the religion-related attractions of a destination are concentrated in a specific site or spread along itineraries or larger areas. This variable has been applied in previous studies (e.g. Wall, 1997; Olsen, 2013) based on the geographic typology of tourist

Integrated systems

Connection among players

Spatial concentr ation High High Low Low Collaborative

systems Fragmentedsystems Conflictual

systems

Fig. 2.4. Territorial systems of religious tourism destinations: a governance perspective.

destinations (points, lines, and areas). In this model, the spatial concentration is high when the religious attractions are grouped in a small area or in a particular site and the tourist flows are concentrated in a unitary and cohesive place. On the other hand, the spatial concentration is low if the religious resources are scattered in larger regions and the visitors are distributed in differ-ent places, creating a polycdiffer-entric religious des-tination (Lozato-Giotart, 1999; Lemmi, 2009).

As mentioned above, the horizontal axis rep-resents the level of stakeholders’ collaboration and cooperation, another essential determinant for the development of a tourism destination (Baggio, 2011). In fact, according to March and Wilkinson (2009, p. 455) the value of the tour-ist experience ‘is created and delivered to tourtour-ists by a complex network of interacting and inter-dependent actors. The actors include those dir-ectly interacting with tourists in planning and delivering various types of tourist experiences and those actors who directly and indirectly sup-port and facilitate such interactions. The tourist is also an active player in the co-production of the tourist experience’.

In religious destinations the actors involved in the creation of the tourist experience are nu-merous and diversified, as religious tourism em-braces many forms of travel (e.g. pilgrimages, retreats, monastery and shrines visits, cultural and heritage tours, etc.).

The main stakeholders in religious destin-ations identified within the literature are: (i) reli-gious organisations (churches, congregations, associations, etc.); (ii) the religious tourism indus-try (faith-based tour operators, guides, religious accommodation, transports, etc.); (iii) local tour-ist bodies; (iv) local communities; (v) volunteers; and (vi) tourists (Shackley, 2001; Shinde, 2012; Munsters and Niesten, 2013).

According to Beritelli (2011), a cooperative behaviour among these actors is a vital condi-tion for a sustainable destinacondi-tion governance structure. The connection among the main play-ers of a religious destination is high when there are strong collaborative relationships. When the cooperation among the stakeholders is fragile the level of connection is low.

The combination of these two axes gener-ates four territorial systems that explain the dif-ferent types of governance adopted by religious destinations (Fig. 2.4).

The first cell of this model shows the terri-torial system that stems from a low spatial con-centration of religious attractions and tourist flows, and from a low connection among players. In a governance perspective, this type of destin-ation presents the characteristics of a fragmented territorial system, as a result of a spontaneous process in which resources are poorly integrated and most of the activities are carried out indi-vidually by the various actors that operate within the destination. Hence, there is a lack of a strong and unambiguous religious tourist proposal.

Sometimes, this fragmentation occurs at a local scale, even in those complex and well-known religious destinations that appear as an integrated system at a macro level.

This is the case for the famous Via Francige-na, a medieval pilgrimage route that connects Canterbury with Rome, running through Eng-land, France, Switzerland and Italy. This historical itinerary was officially recognized by the Council of Europe as one of the European Cultural Routes in 1994. Starting from the original path, the Via Francigena is today a network consisting of sev-eral Vie Francigene (Trono et al., 2017).

Since 2001, it has been managed by the European Association of the Vie Francigene (EAVF), which interacts with European institu-tions, regions, local communities and associ-ations to promote the sustainable development of the territories along the paths.

Despite the general level of integration of the Via Francigena’s network, issues arise along the minor route sections of this path. For ex-ample, according to Lucarno (2016), some Italian sections of the Via Francigena are still underdeveloped, due to an organizational ab-sence that prevents effective forms of cooper-ation and the crecooper-ation of joint initiatives for an integrated promotion and enhancement of the religious proposal. Tron et al. (2017) show that the Via Francigena Salentina, a section heading from Apulia to the Holy Land, presents wide-spread issues related to the inadequacy of the tourism facilities for pilgrims and of the relation-ship networks with local institutions and private stakeholders. Furthermore, Cerutti and Dioli (2013) state that the Via Francigena’s itineraries in the Piacenza valleys are currently in a phase in which there is an explicit organizational intent to create a network among the local players but they are still far from a substantial development.

In summary, it seems that, at the local level, the role of each stakeholders is not particularly well defined and it is usually limited to the pro-motion of individual components of the Via Francigena tourism product. In other words, the local actors do not operate through integrated and coordinated actions as happens along the most well-known parts of the path.

The second quadrant, which combines a weak connection among the stakeholders and a strong spatial concentration, usually reveals a conflictual system. This is the case where the re-sources are concentrated in a limited area, but instead of unitary process of governance, the in-dividual interest of the different players prevails. For example Rome, also known as the ‘eter-nal city’, despite being one of the most import-ant sacred places of worship for the Catholics since ancient times, it does not rely on a unitary promotion of the many religious resources that are scattered in the city. The range of the sub-jects involved in the promotion of the city of Rome is wide and diversified (e.g. Lazio Region, province of Rome, municipality of Rome, Vati-can City and many others public and private bodies), also due to the multifunctional nature of this tourist destination. Rome is not only a re-ligious destination but it is also visited every year by millions of tourists who are attracted by its culture, history, gastronomy, landscape, lifestyle, events etc. It is therefore difficult to build a cohe-sive network for the management of the religious- based attractions and their integration with such a wide range of tourist products offered.

The third quadrant shows the case of the collaborative tourist systems. In this context, the enhancement of the religious product is the out-come of a cohesive network in a destination where the resources and the tourists are spread in a large territory.

The Italian UNESCO site ‘Sacri Monti of Piedmont and Lombardy’ represents a good ex-ample of a collaborative system. The seven Sa-cred Mounts of Piedmont (Belmonte, Crea, Domodossola, Ghiffa, Oropa, Orta and Varallo) and the two of Lombardy (Ossuccio and Varese) consist of a series of chapels that recount epi-sodes and mysteries of sacred life, merging with the magnificent environmental surroundings (Cerutti and Piva, 2016).

Since its addition to the UNESCO World Heri-tage List in 2003, a process has been implemented

in order to coordinate the various stakeholders involved in the management and promotion of the site.

A unitary management plan was signed and adopted by the relevant public administra-tions and the religious instituadministra-tions in order to coordinate strategies and initiatives for the pro-motion of the nine sacred mounts as a unique religious destination. This management plan represents the joint agreement by all the parties involved, i.e. the state superintendence for the protection of cultural heritage, the regional and municipal authorities, as well as the reli-gious authorities. On a local level, the work of religious orders (Friars Minor and Rosminian Fathers) and the Diocesan Curiae is very import-ant in terms of the religious activities and tradi-tions related to the Catholic Church that continue at the Sacri Monti.

According to the documents provided by the UNESCO World Heritage Centre1, the main purpose of the plan is to coordinate the conser-vation management of the properties in a coher-ent manner, adopting common policies and strategies regarding the promotion of cultural, social-economic and tourist activities. The plan provides the framework for the management process and the responsibilities of each party, as well as outlining the programme of the period-ical activities.

A process for coordination is in place to manage the various groups involved in the site. The management system is formed by two bodies, organized on two levels. The first, the Permanent Conference, includes the various or-ganizations with responsibilities relating to the management of the site (state, regions, munici-palities and representatives of the Church). It provides coordination of technical and scientific activities and has a role of political guidance. The second, the Permanent Operative Working Group has an executive role and is composed of a fewer number of subjects. Moreover, this group is in charge of the definition of the technical and operating guidelines and the general manage-ment programs, together with the budgeting, auditing, monitoring and reporting activities on management and preservation.

Besides these two structures there is a Per-manent Secretary in charge of the program-ming and execution of different management tasks, and of the Public Relations activities of

the Permanent Conference. The management system is completed by the standing Permanent Centre for Studies and Documentation, dealing with research and information retrieval for the property.

It emerges that the governance structure of the Sacri Monti is the result of a top-down approach where the public subjects play a key decisional role (d’Angella, De Carlo and Sainaghi, 2010), but the other actors are included in stra-tegic decision making processes in a collaborative network.

Finally, the fourth cell shows integrated systems, where the multiplicity of stakeholders works in synergy to pursue the aims of local de-velopment of the religious destination. It usually comprises specialized religious centres, i.e. mono- functional tourism destinations (Innocenti, 2007) that base their economy almost exclusively on devotional and faith tourism.

Destinations like Lourdes (France), Fatima (Portugal), Medjugorje (Bosnia-Herzegovina) and San Giovanni Rotondo (Italy) are an example of religious-based development where the cultural, social and economic activities gravitate around the holy figures and their mystic experiences.

The plethora of subjects of these destin-ations, ranging from the religious organisations (monasteries, shrines, religious associations etc.) to the other tourist players (accommodations, travel agencies, tour operators, souvenir shops, transports etc.), are all working in synergy to deliver the religious tourist experience.

According to Rinschede (1992) and Shackley (2001), such destinations have grown from vil-lages to cities as a result of pilgrimage and reli-gious tourist dynamics, showing a growing ability to manage the governance process in an inte-grated and effective way.

This study makes three important contribu-tions to the current literature on religious tourism and destination management. Firstly, it explores the issues of destination governance with the de-velopment of a conceptual framework for the analysis of tourist destinations. Secondly, this

study demonstrates the effective applicability of governance models and approaches to religious destinations. Lastly, it proposes a new model that offers a possible taxonomy for the governance of religious destinations based on two key elements: the spatial concentration of religious destin-ations and the level of connection among the stakeholders.

Conclusion

This chapter has looked at managing sacred religious tourism destinations as a continuous process in which the relationship among the multiplicity of actors plays a fundamental role. The chapter has examined the relationship be-tween a religious destination and sacred sites, and its effectiveness in the management of reli-gious destinations. The research has shown how the destinations can present themselves with very different organisational forms of govern-ance, starting from the relational dynamics between the subjects and the peculiarities of the local contexts in which they occur.

The primary purpose of this chapter was to look at the religious tourism destination governance but it has also demonstrated some approaches to developing a theory of the concept of destination governance ap-plied to religious tourism destinations. Fur-thermore, the interpretation of destination management within a geographical perspec-tive adds value via an increased awareness by religious destinations of their potential for enhancement, which relies on the territory and on the subjects who undertake the ac-tions of local development. Finally, the chap-ter has raised issues of the complexity of managing religious sites; indeed the core of any management model must have an effect-ive development strategy, which combines the needs of tourists and local religious worship within the area.

Note

1 http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1068/documents (accessed 25 July 2018). http://whc.unesco.org/uploads/

References

Baggio, R. (2011) Collaboration and cooperation in a tourism destination: a network science approach. Current Issues in Tourism 14, 183–189.

Beeton, S. (2006) Community Development through Tourism. Landlinks Press, Melbourne, Australia. Beritelli, P. (2011) Cooperation among prominent actors in a tourist destination. Annals of Tourism Research

38, 607–629.

Beritelli, P., Bieger, T. and Laesser, C. (2007) Destination governance: using corporate governance theor-ies as a foundation for effective destination management. Journal of Travel Research 46, 96–107. Bieger, T. (2000) Destination management e finanziamenti. In: Pechlaner, H. and Weiermair, K. (eds)

Destination Management. Fondamenti di marketing e gestione delle destinazioni turistiche. T.U.P. Touring University Press, Milano, Italy.

Blackwell, R. (2007) Motivations for religious tourism, pilgrimage, festivals and events. In: Raj, R. and Morpeth, N.D. (eds) Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Festivals management: An International Perspective. CABI International, Wallingford, UK, pp. 35–47.

Buhalis, D. (2000) Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tourism Management 21, 97–116. Cerutti, S. and Dioli, I. (2013) Via Francigena mountain itineraries: the case of Piacenza valleys.

Inter-national Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 1, 82–92.

Cerutti, S. and Piva, E. (2015) Religious tourism and event management: An opportunity for local tourism development. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 3, 54–65.

Cerutti, S. and Piva, E. (2016) The role of tourists’ feedback in the enhancement of religious tourism des-tinations. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 4, 5–16.

Collins-Kreiner, N. (2009) The geography of pilgrimage and tourism: Transformations and implications for applied geography. Applied Geography 2, 1–12.

D’Angella, F., De Carlo, M. and Sainaghi, R. (2010) Archetypes of destination governance: A comparison of international destinations. Tourism Review 65, 61–73.

De Araujo, L.M. and Bramwell, B. (2002) Partnership and regional tourism in Brazil. Annals of Tourism Research 29, 1138–1164.

Della Corte, V. (2000) La gestione dei sistemi locali di offerta turistica. CEDAM, Padova, Italy.

Della Corte, V. and Sciarelli, M. (2012) Destination management e logica sistemica. Un confronto interna-zionale. Giappichelli Editore, Torino, Italy.

Della Corte, V., Del Gaudio, G. and Iavazzi, A. (2014) Leadership in destination management: its implica-tions in a systemic approach. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management 4, 194–203. Di Giovine, M.A. (2016) A higher purpose: sacred journeys as spaces for peace in christianity. In: Pazos,

A.M. (ed.) Pilgrims and Pilgrimages as Peacemakers in Christianity, Judaism and Islam. Routledge, London and New York, pp. 9–38.

Diez Santo, D. (2012) The use of matrix diagnoses in strategic planning for inland tourism areas: a meth-odological proposal applied to the interior of the Alicante province. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 60, 489–492.

Digance, J. (2006) Religious and secular pilgrimage: Journeys redolent with meaning. In: Timothy, D.J. and Olsen, D.H. (eds) Tourism, Religion and Spiritual Journeys, Routledge, Abingdon, UK, pp. 36–48. Dredge, D. (2006) Policy networks and the local organisation of tourism. Tourism Management 27, 269–280. Dredge, D. and Jenkins, J. (2007) Tourism Planning and Policy. Wiley, Melbourne, Australia.

Dwyer, L., Čorak, S. and Tomljenović, R. (2017) Introduction. In: Dwyer, L., Čorak, S. and Tomljenović, R. (eds) Evolution of Destination Planning and Strategy. The Rise of Tourism in Croatia. Springer Inter-national Publishing, Switzerland, pp. 1–14.

Egresi, I. and Kara, F. (2012) Tourism at religious sites: A case from Mardin, Turkey. Geographica Timisiensis 21, 5–15.

Ejarque, J. (2003) La destinazione turistica di successo. Marketing e management. Hoepli, Milano, Italy. Finney, R.Z., Orwig, R.A. and Spake, D.F. (2009) Lotuseaters, pilgrims, seekers, and accidental tourists: how

different travelers consume the sacred and the profane. Services Marketing Quarterly 39, 148–173. Flagestad, A. and Hope, C. (2001) Strategic success in winter sports destinations: A sustainable value

creation perspective. Tourism Management 22, 445–461.

Franch, M. (2010) (ed.) Marketing delle Destinazioni Turistiche. McGraw-Hill, Milan, Italy.

Fyall, A., Oakley, B. and Weiss, A. (2000) Theoretical perspectives applied to inter-organisational collab-oration on Britain’s Inland waterways. In: Crotts, C., Buhalis, D. and March, R. (eds) Global Alliances in Tourism and Hospitality Management. Haworth Press Inc, New York, pp. 89–112.

Gill, A.M. and Peter, W. (2010) Re-thinking Resort Growth and Governance: An Evolutionary Network Approach, Available at: http://ertr.tamu.edu/files/2012/09/3109_Gill-Williams.pdf (accessed 14 July 2018). Go, M. and Govers, R. (2000) Integrated quality management for tourist destinations: A European

perspec-tive on achieving competiperspec-tiveness. Tourism Management 21 79–88.

Griffin, K.A. (2007), The globalization of pilgrimage tourism? Some thoughts from Ireland. In: Raj, R. and Morpeth, N. (eds) Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Festivals Management: An International Per-spective. CABI International, Wallingford, UK, pp. 15–34.

Hall, C.M. (2008) Tourism Planning: Policies, Processes and Relationships. Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey.

Howie, F. (2003) Managing the Tourist Destination. Continuum, London, UK. Innocenti, P. (2007). Geografia del Tturismo, 3rd edn. Carocci Editore, Bologna, Italy.

Jackowski, A. (2000) Religious tourism – problems with terminology. In: Jackowski, A. (ed) Peregrinus Cra-coviensis. Publishing Unit, Institute of Geography, Jagiellonian University, Cracow, Poland, pp. 63–74. Kerr, B., Barron, G. and Wood, R.C. (2001) Politics, policy and regional tourism administration: A case

examination of Scottish area tourist board funding. Tourism Management 22, 649–657.

Kurleto, M. (2013) Determinants of the effectiveness of tourist destination management. Advanced Research in Scientific Areas 2, 398–401.

Leiper, N. (2004) Tourism Management. Pearson Education, London, UK.

Lemmi, E. (ed.) (2009) Dallo spazio consumato ai luoghi ritrovati. Verso una geografia del turismo sosteni-bile. Franco Angeli, Milano, Italy.

Levi, D. and Kocher, S. (2009) Understanding tourism at heritage religious sites. Focus 6, 17–21.

Lozato-Giotart, J.P. (1999) Geografia del turismo. Dallo spazio visitato allo spazio consumato. Franco Angeli, Milano, Italy.

Lucarno, G. (2016) The Camino de Santiago de Compostela (Spain) and the via Francigena (Italy): A com-parison between two important historic pilgrimage routes in Europe. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 4(7), 47–58.

Manente, M. (2008) Destination management and economic background: defining and monitoring local tour-ist destinations. In: Proceedings of UNWTO Conference of Tourism: Knowledge as value advantage of tourism destinations, October 29–31 2008, Malaga, Spain, . UNWTO, Malaga, Spain, pp. 363–384. Manente, M. and Minghetti V. (2006) Destination management organisations and actors. In: Buhalis, D. and

Costa, C. (eds) Tourism Business Frontiers. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, pp. 228–238. March, R. and Wilkinson, I. (2009). Conceptual tools for evaluating tourism partnerships. Tourism

Manage-ment 30, 455–462.

Martini, U. (2002) Da luoghi a destinazioni turistiche. Ipotesi di destination management nel turismo alpino. In: Franch, M. (ed.) Destination Management. Governare il turismo tra locale e globale. Giappicchelli Editore, Torino, Italy.

Martini, U. (2005) Management dei sistemi territoriali. Gestione e marketing delle destinazioni turistiche. Giappichelli Editore, Torino, Italy.

Mazurek, T. (2014) Competitiveness in tourism-models of tourism competitiveness and their applicability: case study Austria and Switzerland. European Journal of Tourism, Hospitality and Recreation 5, 73–94. Munsters, W. and Niesten, M. (2013) The cultural tourism sustainability mix applied to the development of

contemplative tourism in Limburg, the Netherlands. In: Raj, R., Griffin, K. and Morpeth, N.D. (eds) Cultural tourism. CABI International, Wallingford, UK, pp. 140–150.

Nieminen, K. (2012) Religious Tourism – A Finnish Perspective. Master’s Thesis, Hagaa-Helia University of Applied Sciences, Helsinki, Finland. Available at https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/51755 (accessed 24 July 2018).

Nordin, S. and Svensson, S. (2007) Innovative destination governance: The Swedish ski resort of Are. Entrepreneurship and Innovation 8, 53–66.

Olsen, D.H. (2013) A scalar comparison of motivations and expectations of experience within the religious tourism market, International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 1, 40–61.

Park, C. (2004) Religion and geography. In: Hinnells, J. (ed.) Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion. Routledge, London, UK.

Pearce, D.G. (2012) Frameworks for Tourism Research. CABI International, Wallingford, UK.

Pechlaner, H. and Weiermair, K. (2000) Destination Management. Fondamenti di marketing e gestione delle destinazioni turistiche, T.U.P. Touring University Press, Milano, Italy.

Pechlaner, H., Raich, F. and Beritelli, P. (2010) Introduction to the Special Issue: Destination governance. Tourism Review 65, 4–85.

Lau, P.L. and Tay Koo, T.R. (2017) A multilevel Gini decomposition approach to measuring the geographic concentration of tourism, Current Issues in Tourism 20, 883–893.

Laws, E., Richins, H., Agrusa, J. and Scott, N. (2011) Tourist destination governance: Practice, theory and issues. CABI International, Wallingford, UK.

Manente, M. (2008) Destination management and economic background: defining and monitoring local tourist destinations. In: Proceedings of UNWTO Conference of Tourism: Knowledge as Value Advan-tage of Tourism Destinations, October 29–31, 2008. UNWTO, Malaga, Spain, pp. 363–384.

Raj, R. (2008) The application of destination management model for religious festivals. Tourism Today 8, 118–128.

Raj, R. (2012) Religious tourist’s motivation for visiting religious sites. International Journal Tourism Policy 4, 95–105.

Raj, R. and Griffin, K.A. (2015) Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Management: An International Perspective, 2nd edition. CABI, Wallingford, UK.

Richards, G. and Fernandes, C. (2007) Religious tourism in Northern Portugal. In: Richards, G. (ed.) Cultural Tourism: Global and Local Perspectives. The Haworth Press, Binghampton, New York, pp. 215–238. Rinschede, G. (1992) Forms of religious tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 19, 51–67.

Shackley, M. (2001) Managing Sacred Sites: Service Provision and Visitor Experience. Continuum, London, UK.

Shackley, M. (2001) Managing sacred sites: Service provision and visitor experience. Material Religion 1, 428–429.

Shinde, K. (2012) Policy, planning, and management for religious tourism in Indian pilgrimage sites. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 4, 277–301.

Smith, V. (1992) The Quest in Guest. Annals of Tourism Research 19, 1–17.

Stoker, G. (1998) Governance as theory: five propositions. International Social Science Journal 50, 17–28. Stokes, R. (2008) Tourism strategy making: Insights to the events tourism domain. Tourism Management

29, 252–262.

Swatos, W.J. Jr. (2006) One for Charles and one for England: Pilgrimage without Tourism. In: Swatos, W.H. Jr. (ed.) On the Road to Being There: Studies in Pilgrimages and Tourism in Late Modernity. Broll, Leiden, Boston, Massachusetts.

Tamma, M. (2000) Aspetti strategici del destination management. In: Pechlaner, H. and Weiermair, K. (eds) Destination Management. Fondamenti di marketing e gestione delle destinazioni turistiche, T.U.P Touring Editore, Milano, Italy.

Tamma, M. (2012) Aspetti strategici del destination governance. In: Pechlaner, H., Paniccia, P., Valeri, M. and Raich, F. (eds) Destination Governance. Teoria ed esperienze, Giappichelli Editore, Torino, Italy. Timothy, D.J. and Olsen, D.H. (2006) Tourism, Religion and Spiritual Journeys. Routledge, London and

New York.

Trono, A. (2015) Politics, policy and the practice of religious tourism. In: Raj, R. and Griffin, K.A. (eds) Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage Management: An International Perspective, 2nd edition. CABI, Wallingford, UK, pp. 16–36.

Trono, A., Ruppi, F., Mitrotti, F. and Cortese, S. (2017) The via Francigena Salentina as an opportunity for experiential tourism and a territorial enhancement tool. Almatourism-Journal of Tourism, Culture and Territorial Development 8, 20–41.

UNWTO (2007) A Practical Guide to Tourism Destination Management. World Tourism Organization, Madrid, Spain.

Wall, G. (1997) Tourism attractions: Points, lines and areas. Annals of Tourism Research 24, 240–243. Weaver, D. (2000) Tourism Management. Wiley, Sydney, Australia.

Wiltshier, P. and Griffiths, M. (2016) Management practices for the development of religious tourism sacred sites: managing expectations through sacred and secular aims in site development; report, store and access. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage 4, 1–8.

Wong, C.U.I., Ryan, C. and McIntosh, A. (2013) The Monasteries of Putuoshan, China: Sites of secular or religious tourism? Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 30, 577–594.

Wright, K. (2008) The Christian Travel Planner. Thomas Nelson, Nashville, Tennessee.

[AU 1]

Author Query: