POLITECNICO DI MILANO

School of Industrial and Information Engineering

Department of Management, Economics and Industrial Engineering

Master of Science in Management Engineering

A Model for the Corporate Entrepreneurship Journey.

Framing forms and practices from explorations in the

energy sector.

Supervisor:

Prof. Josip Kotlar

Assistant Supervisor: Dott. Luca Manelli

Master Thesis

Author: Alessandro Li Vigni

Matr.

894424

Innanzitutto, grazie al Prof. Kotlar ed all’Ing. Manelli per la

fiducia e la disponibilità mostrate in questo percorso.

Grazie ai miei fratelli, Pietro e Francesco, e a mia sorella,

Maria Rita, perché ogni istante passato con loro per me è

stato, e sempre sarà, oggetto sia di crescita, sia di svago.

Grazie ad Elèna, per essere stata sempre al mio fianco,

comprendendomi, supportandomi e dandomi preziosi consigli.

Ma soprattutto, ai miei genitori, per i quali nessun

5

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SOMMARIO... 12

ABSTRACT ... 13

1. INTRODUCTION ... 15

1.1. CLARIFYING THE DOMAIN OF “CE” ... 16

1.2 CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: THE JOURNEY ... 18

1.3 AIM OF THE THESIS ... 20

2. BACKGROUND ... 23

2.1 HISTORY AND DEFINITIONS ... 23

2.2 TRIGGERS AND ANTECEDENTS TO “CE” ... 34

2.2.1 TRANSFORMATIONAL TRIGGERS ... 34

2.2.2 ORGANIZATIONAL ANTECEDENTS ... 40

2.3 CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP OBJECTIVES ... 46

2.4 FORMS OF CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP ... 49

2.5 OUTCOMES OF CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP ... 55

2.5.1 ORGANIZATIONAL ... 55

2.5.2 INDIVIDUAL ... 58

2.6 LINKING THE CONSTRUCTS: A FRAMEWORK FOR “CE” ... 61

2.7 RESEARCH QUESTIONS ... 65

3. THE ENERGY SECTOR ... 68

6

3.2 MANAGING DISRUPTION ... 71

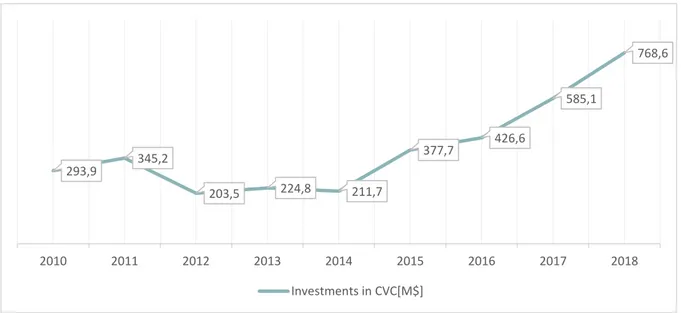

3.3 KEY NUMBERS FOR CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP ... 74

4. METHODOLOGY ... 78

4.1 RESEARCH SETTING ... 78

4.2 CASE STUDIES’ SELECTION... 80

4.3 DATA COLLECTION ... 83 4.4 DATA ANALYSIS ... 86 5. FINDINGS ... 89 5.1 ALPERIA ... 89 5.1.1 GROUP OVERVIEW ... 89 5.1.2 INDUSTRIAL PLAN 2017-2021 ... 90 5.1.3 DIGITAL STRATEGY ... 93

5.1.4 INNOVATION AT ALPERIA AND THE “ALPERIA STARTUP FACTORY” ... 94

5.1.5 ALPERIA BARTUCCI: INNOVATION AND THE INTERNAL R&D TEAM ... 98

5.1.6 CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP JOURNEYS AT ALPERIA ... 100

5.2 AVVENIA ... 111

5.2.1 COMPANY OVERVIEW ... 111

5.2.2 THE INTEGRATION WITH TERNA ... 112

5.2.3 INNOVATION AT AVVENIA: DIANA PLATFORM ... 113

5.2.4 THE “KNOWLEDGE-SHARING” APPROACH ... 114

5.2.5 CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP JOURNEYS AT AVVENIA ... 116

5.3 ENEA ... 121

7

5.3.2 THE BIRTH OF THE “SMART CITIES AND COMMUNITIES” LABORATORY ... 122

5.3.3 “SCC” LAB AND THE STARTUPS’ ECOSYSTEM ... 124

5.3.4 THE KNOWLEDGE SHARING STRATEGY ... 127

5.3.5 A FOCUS ON TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER: THE CASE OF SPIN-OFFS ... 130

5.3.6 CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP JOURNEYS AT ENEA ... 131

5.4 ENEL ... 144

5.4.1 GROUP OVERVIEW ... 144

5.4.2 A HISTORY OF STRATEGIC EVOLUTION ... 145

5.4.3 AN OPEN POWER ... 152

5.4.4 A FOCUS ON INNOVATION AT ENEL: “ENEL FOR STARTUPS” ... 156

5.4.5 DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION AT ENEL ... 159

5.4.6 CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP JOURNEYS AT ENEL ... 162

5.5. METRON ... 179

5.5.1 COMPANY OVERVIEW ... 179

5.5.2 METRON’S FUNDING ROUNDS: AN INNOVATION-ORIENTED ATTITUDE ... 180

5.5.3 OPENNESS AT METRON ... 181

5.5.4 THE ACQUISITION OF “L’ÉNERGIE” ... 182

5.5.4 CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP JOURNEYS AT METRON ... 183

5.6. CROSS-CASE ANALYSIS ... 186

5.6.1 A FINAL SAMPLE OF CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURIAL PRACTICES ... 186

5.6.2 A DIVERGENCE AMONG THE CASES: THE ENTREPRENEURIAL RATIONALE187 5.6.3 “CE” PRACTICES ACROSS THE CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURIAL JOURNEY 188 6. DISCUSSION ... 198

8

6.1 THEORETICAL EXTENSIONS AND CONTRIBUTIONS ... 198

6.1.1 PREAMBLE... 198

6.1.2 PERFORMING CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN REAL PRACTICES ... 198

6.1.3 RECONCILING WITH “CE” THEORETICAL FORMS ... 206

6.1.4 A FINAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURIAL JOURNEY ... 210

6.2 THEORETICAL AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS ... 215

6.3 LIMITATIONS ... 216

6.4 CONCLUSIONS ... 217

9

LIST OF FIGURES

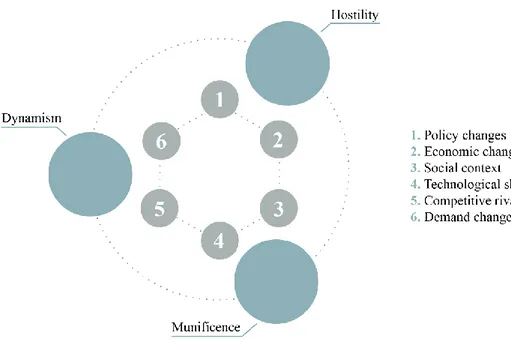

Figure 1. External triggers to Corporate Entrepreneurship. (Source: own elaboration) ... 39

Figure 2. Organizational antecedents to Corporate Entrepreneurship. (Source: own elaboration) ... 45

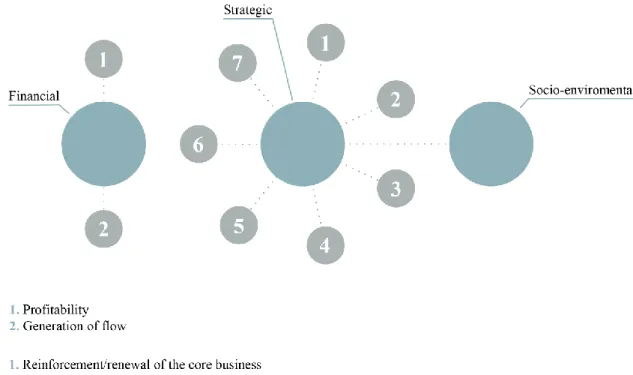

Figure 3. Objectives for Corporate Entrepreneurship. (Source: own elaboration) ... 48

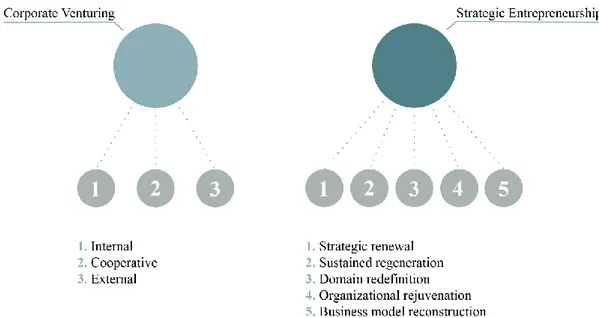

Figure 4. Forms of Corporate Entrepreneurship. Dark blue intends a different level of analysis. (Source: own elaboration) ... 53

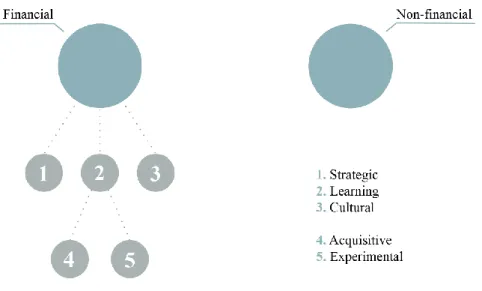

Figure 5. Organizational outcomes from Corporate Entrepreneurship. (Source: own elaboration) ... 58

Figure 6. Individual outcomes from Corporate Entrepreneurship. (Source: own elaboration) ... 60

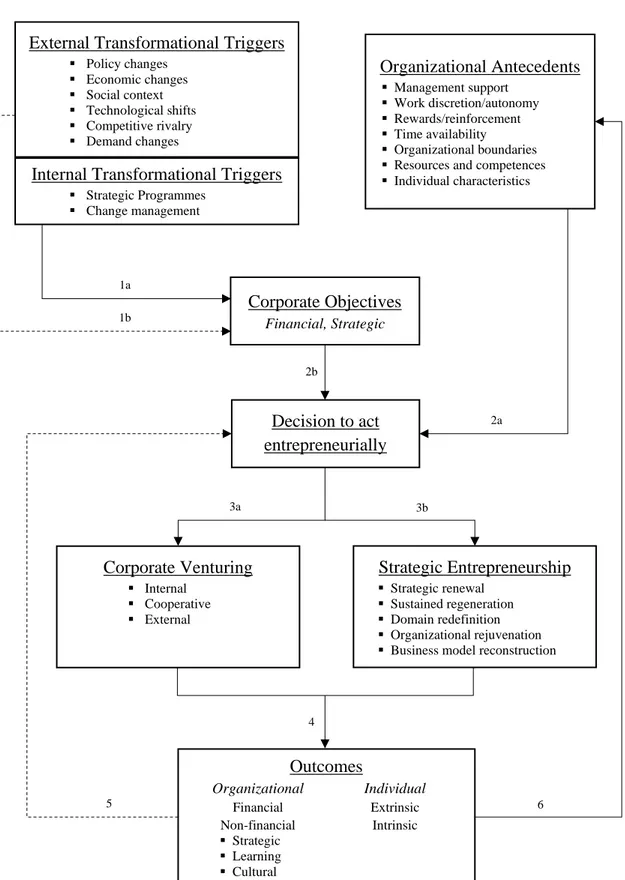

Figure 7. Theoretical framework for Corporate Entrepreneurship. (Source: own elaboration) ... 66

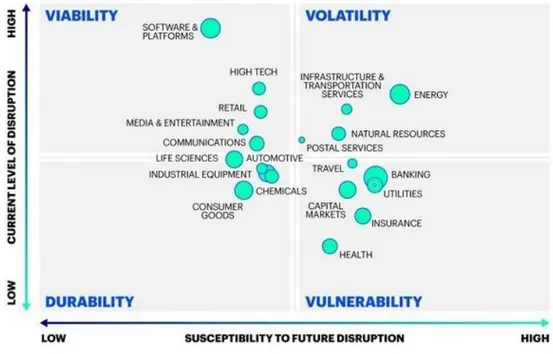

Figure 8. Industry disruption: the volatility of the energy sector. (Source: Accenture, 2018) ... 71

Figure 9. Key pillars to manage disruption. (Source: own elaboration) ... 74

Figure 10. Value of CVC investments in the energy sector. (Source: Energy & Strategy Group, 2019) ... 75

Figure 11. Alperia Group: Corporate Structure. (Source: own elaboration) ... 92

Figure 12. Enel brand identity. (Source: Enel) ... 147

Figure 13. Enel's logo since 2016. (Source: Enel) ... 152

Figure 14. Breadth and depth of emerging entrepreneurial practices. (Source: own elaboration) ... 204

Figure 15. Classification of entrepreneurial practices basing on the origin of innovation. (Source: own elaboration) ... 205

Figure 16. Theoretical CE prospects and their relationship with entrepreneurial practices. (Source: own elaboration). ... 210

10

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Definitions of Corporate Entrepreneurship: A Sum-Up. (Source: own elaboration) ... 33

Table 2. Description of companies selected. (Source: own elaboration) ... 82

Table 3. Case Studies: informants interviewed. (Source: own elaboration) ... 84

Table 4. Enel's case cardinal sources ... 85

Table 5. CE journey and activities from Alperia Case Studies: A Sum-Up. (Source: own elaboration) ... 110

Table 6. CE journey and activities from Avvenia Case Studies: A Sum-Up. (Source: own elaboration) ... 120

Table 7. CE journey and activities from ENEA Case Studies: A Sum-Up. (Source: own elaboration) ... 143

Table 8. CE journey and activities from Enel Case Studies: A Sum-Up. (Source: own elaboration) 178 Table 9. CE journey and activities from Metron Case Studies: A Sum-Up. (Source: own elaboration) ... 185

Table 10. Findings from case studies: practices of Corporate Entrepreneurship. (Source: own elaboration) ... 194

12

SOMMARIO

La presente tesi si radica nel tema della Corporate Entrepreneurship (CE), un fenomeno cruciale per managers e ricercatori, ma non esente da ambiguità e incongruenze. Ad esempio, una definizione univoca della Corporate Entrepreneurship è tuttora assente in letteratura, e spesso tale costrutto è stato inappropriatamente associato ad altre terminologie, come quella della “Intrapreneurship”. Ma, soprattutto, non è ancora chiaro le prospettive teoriche in cui Corporate Entrepreneurship possa essere classificata, né la ricerca ha finora esplorato in quali forme tale paradigma venga operativamente implementato. Ciò considerato, questo studio si fonda su cinque casi studio multipli incentrati nell’industria dell’energia, un ecosistema estremamente dinamico e attualmente in profonda trasformazione, in cui le aziende sono costrette ad un continuo rinnovamento per sostenere il loro vantaggio competitivo. Così, l’elaborazione dei dati derivanti dai casi studio ha portato a tre principali risultati. In primis, CE può essere concettualizzata sulla base di un continuo di tre prospetti teorici, ovvero “business configuration”, “organizational design” e “knowledge connection”. In secundis, le narrative hanno rivelato un insieme di iniziative di CE, dalle quali è emerso che coinvolgimenti aziendali a tuttotondo tendono a generare cambiamenti strategici e/o culturali radicali, o in ogni modo non marginali. Infine, tali iniziative hanno evidenziato come le aziende facciano sempre più ricorso a fonti esterne di innovazione ed imprenditoria, così definitivamente appurando come Corporate Entrepreneurship non possa essere confinata alla sopramenzionata “Intrapreneurship”. In ultima analisi, sul fondamento di tali risultati, la presente tesi propone un modello teorico comprendente cause scatenanti, antecedenti, obiettivi, prospetti teorici, pratiche, e conseguenze della Corporate Entrepreneurship, con la finalità di dare una visione di insieme sui costrutti e le relazioni caratterizzanti i processi imprenditoriali aziendali.

13

ABSTRACT

This dissertation positions in the domain of Corporate Entrepreneurship, a cardinal but ambiguous paradigm among researchers and practitioners. Corporate Entrepreneurship suffered for different terminologies in being described, as well as for inappropriate labels, such as “Intrapreneurship”. But, particularly, exploring the constructs framing the firm-level entrepreneurial processes, theorists often exhibited incongruities in categorizing the forms of Corporate Entrepreneurship, nor they explored yet what the real practices through which CE may manifest are. Grounding on these gaps this study adopted a multi-case theory-building methodology, leveraging on five narratives from the energy sector, an extremely dynamic environment which is facing an upset of its competitive landscape, mostly due to nowadays’ digital disruption. Basing on results from case studies, data analysis revealed for three major findings. First, Corporate Entrepreneurship can be intended as a paradigm encompassing a continuum of three theoretical prospects, i.e. business configuration, organizational design, and knowledge connection. Second, a comprehensive set of entrepreneurial practice presented, from which it emerged that an entrepreneurial organization-wide involvement leads either to relevant strategic turnaround or to considerable cultural shifts, but in no case to marginal transformations only. Thirdly, re-elaboration on the aforementioned entrepreneurial practices entitled to definitely characterize Corporate Entrepreneurship as a phenomenon embracing a wider umbrella than the pure intrapreneurial one. Ultimately, pivoting on these findings, this dissertation proposes for a model encompassing triggers, antecedents, objectives, forms, practices and outcomes of Corporate Entrepreneurship, thereby providing a tool for an encyclopaedical understanding of the firm-level entrepreneurial processes.

15

1. INTRODUCTION

The concept of Corporate Entrepreneurship (CE) has sharply acquired traction in the last decades as a response to innovative contexts requiring firms for growth strategies (Covin & Miles, 1999). In fact, phenomena as globalization and technological change have contributed in increasing competitiveness, thus shaping dynamic and uncertain market environments (Bettis & Hitt, 1995; Corbett, Covin, O’Connor, & Tucci, 2013). For example, more recent digital disruption has transformed a variety of industries, often favouring “unicorns” and promising startups against consolidated organizations. In these scenarios, companies’ survival remains constrained to ambidexterity. Namely, efforts are to be devoted in exploiting their current competitive advantage, while exploring future opportunities (Ireland & Webb, 2007).

Hence, corporate entrepreneurial processes result to be the consequence to managers’ recognition of this need for renewal. By leveraging on these vision-driven activities, organizations are entitled to innovate products, processes and routines, thus perpetuating their competitive superiority (Covin & Slevin, 2008; Kuratko, Hornsby, & Covin, 2014).

The proper definition of Corporate Entrepreneurship is still debated today. In fact, the broadness of CE’s umbrella and researchers’ multiple levels of analysis led to ambiguities in conceptualizing CE (Sharma & Chrisman, 1999).

In a general sense, Corporate Entrepreneurship unifies two different domains, which assume unrelated meanings if taken as stand-alone. Focusing on “entrepreneurship”, contemporary research originated with Schumpeter, who perceived the entrepreneur as one “who carries out new combinations”, leading to an improvement in the status-quo (Schumpeter, 1934). This evolved over time, as today entrepreneurship can be defined as the set of processes aiming at

16 discovering and exploiting profitable (business) opportunities (Shane & Venkataraman, 2007). Nevertheless, Schumpeter’s identification of entrepreneurship with innovation still finds support among researchers (Stevenson & Jarillo, 2007). Integrating these concepts with the term “corporate”, it results that CE aims at renewing the entrepreneurial footprint of consolidated firms, as at the very early stages of their organization life cycles (OLC).

But the mere association among the domains of corporations and entrepreneurship does not emphasize a fundamental peculiarity of Corporate Entrepreneurship. Namely, CE is not only contemplated for large firms; rather, entrepreneurial activities are fundamental even in small and medium-sized enterprises, despite researchers’ exploratory studies have often focused on corporations (Carrier, 1994, 1996).

That being said, in this dissertation Corporate Entrepreneurship is intended as a paradigm encompassing new entries, entrepreneurial recombination of existing resources or, broadly speaking, business-oriented innovations which purposefully energize the organization in an attempt to improve its competitive standing.

1.1. CLARIFYING THE DOMAIN OF “CE”

As already briefly introduced, the domain of Corporate Entrepreneurship finds ambiguity among researchers. In fact, this concept has been confusingly used to express various organizational phenomena in the field of innovation (Christensen, 2004). Particular vagueness exists at the interplay between CE and the constructs of intrapreneurship and Open Innovation.

The concepts of CE and of intrapreneurship have been widely intended as interchangeable (Hornsby, Kuratko, & Zahra, 2002), even if this is not the case. In fact, intrapreneurship refers to employee initiatives to undertake something new within an organization, despite not asked to do so (Toftoy et al., 2001). Therefore, contrarily to CE, intrapreneurship is a bottom-up

17 approach, which adopts an individual-level perspective and operates at the organizational margins (Antoncic & Hisrich, 2003).

In accordance, intrapreneurship can be considered as a relevant component of the CE construct, rather than one of its labels. To better understand, different possibilities exist for a company to pursue entrepreneurial practices. Opportunities may materialize either inside or outside the boundaries of the organisation. Intrapreneurship englobes the first category, i.e. the cases in which the firm purely leverages on its internal resources for innovation purposes.

But, as said, innovation can be generated even outside the boundaries of an organization, which can use its external networks to take part in joint ventures, external venture capital, strategic alliances, R&D partnerships, exc. (Christensen, 2004). In this case, the company opens its organizational boundaries to external actors, with which it collaborates.

In this direction, a firm can result to be engaged in Corporate Entrepreneurship by exploring the Open Innovation (OI) paradigm. This term refers to the “use of purposive inflows and outflows of knowledge to accelerate internal innovation and expand the markets for external use of innovation” (Chesbrough, 2006). Substantially, open innovation is a distributed approach to innovation which enables external actors’ participation in the company’s innovation process.

As the existing literature has not fully explored the interplay between the two disciplines yet, it can be argued whether they are in contrast or not. In reality, differences exist among the two. In fact, as said, Corporate Entrepreneurship englobes even closed innovation phenomena, pursuable by leveraging on internal assets and resources. Then, CE entails the nurturing and diffusion of the entrepreneurial culture within the organization. This is in turn fundamental to properly benefit either from close or open innovation practices. However, in the other hand, Corporate Entrepreneurship is more than innovation. Namely, CE entails an explicit

business-18 orientation: firms adopt an entrepreneurial perspective when they engage in transformational (innovation) activities with the objective of improving their competitive performances (Covin & Miles, 1999). For these reasons, business-oriented Open Innovation activities can be intended as a part of a broader model of CE (Cavallaro & Gaschi, n.d.).

1.2 CORPORATE ENTREPRENEURSHIP: THE JOURNEY

Corporate Entrepreneurship differs in depth and breadth among companies, mainly due to the potential presence of transformational triggers, i.e. elements that provoke an entrepreneurial behaviour to occur, and of organizational antecedents shaping each business scenario, i.e. elements that predispose to entrepreneurial behaviour. As regards the former, contemporary literature distinguished between external and internal triggers for a firm-level entrepreneurial strategy to be defined (Kuratko, Hornsby, & Goldsby, 2004). In fact, in one hand, dynamic, hostile and munificent environments can push managers foreseeing for radical changes, initiating entrepreneurial actions indeed (Zahra, 1993b). In the other hand, the existence of specific strategic programmes, as well as more disruptive events, like change management, can precipitate in entrepreneurial behaviour too (Schindehutte, Morris, & Kuratko, 2000). Instead, in terms of organizational antecedents, literature agrees in recognizing internal contexts characterized by high managerial promotion of entrepreneurial behaviour, failure toleration, freedom, incentive systems, time availability to pursue innovation and clear definition of expected outcomes as those which best nurture an entrepreneurial culture (Kuratko, Montagno, & Hornsby, 1990).

Having defined the triggers and antecedents to CE, it is important to clarify the objectives supporting a company’s decision to pursue this orientation. In brief, researchers realize Corporate Entrepreneurship to be established in organizations for a host of purposes beyond innovation, as for financial performances, strategic renewal, learning and knowledge

19 development, internationalization, sustainability, to foster resources efficiencies, and as a strategy per se (Kuratko, Ireland, Covin, & Hornsby, 2005).

Also, in time, researchers attempted to conceptualize some forms of CE, often adopting multiple levels of analysis. Covin and Miles (1999) distinguished four main forms of CE: sustained regeneration (the introduction of new products or the entrance in new markets), organizational rejuvenation (a major, internally focused innovation aimed at improving firm functioning or strategy implementation), strategic renewal (the pursuit of a new strategic direction), and domain redefinition (the creation and exploitation of a new, previously unoccupied product/market arena) (Covin & Miles, 1999). Christensen (2004) pointed out four perspectives of CE, i.e. corporate venturing, internal resources, internationalization and external collaborations, englobed in the two major domains of intrapreneurship and exopreneurship (Christensen, 2004). The most recent contribution is related to Morris, Kuratko and Covin (2008). Basing on the pioneering studies of Guth and Ginsberg (1990), and of Sharma and Chrisman (1999), they identified two domains of CE: corporate venturing, defined as the creation of new businesses either internal or external to the organizational boundaries, and strategic entrepreneurship, a construct which entails opportunity-seeking and advantage-seeking behaviour and which includes a broad array of entrepreneurial initiatives that involve innovation to pursuit competitive advantage. Specifically, five forms of strategic entrepreneurship have been recognized: strategic renewal, sustained regeneration, domain redefinition, organizational rejuvenation and business model reconstruction (Corbett et al., 2013; Kuratko & Audretsch, 2013).

To conclude, entrepreneurial practices intuitively result in a variety of outcomes, advantaging both the organizational members and the company per se. At the individual-level, literature distinguished outcomes into intrinsic (psychological) and extrinsic (tangible). Extrinsic outcomes englobe financial or other tangible rewards linked to the firm’s financial

20 performances. Instead, intrinsic rewards refer to elements such as the satisfaction for developing personal ideas and the increase in responsibility and control in one’s own career. Examples of individual-level outcomes can be promotions, bonuses, salary increases, enhancements of self-image, development of individual knowledge and skills, exc. Moving to the organizational-level, Corporate Entrepreneurship impacts on a broad array of factors in this domain. Among the possible outcomes, it is possible to recognize an improvement in the company’s financials (sales, productivity, market share, labour efficiency, waste), in the corporate culture (number of ideas suggested/implemented, amount of time dedicated to innovation), the development of new competences and knowledge, increases in reputation, the diversification into new product-market arenas, strategic changes in core businesses, the broadening of the corporate technology portfolio and, generally speaking, the maintenance/reestablishment of the company’s competitive advantage (Kuratko et al., 2005).

1.3 AIM OF THE THESIS

Despite the domain of Corporate Entrepreneurship has been widely explored by researchers, it is not exempt from redundancies and question marks yet. In particular, the numerous perspectives employed by authors in conducting their studies made it difficult to integrate the different conceptualizations of Corporate Entrepreneurship.

For example, both Christensen (2004) and Morris, Kuratko, Covin (2008) deal with the concept of corporate venturing. However, while Christensen’s (2004) model seems to adopt a more operative level of analysis (e.g. by coupling venturing with “external collaborations”), CE forms like strategic renewal, sustained regeneration, domain redefinition, organizational rejuvenation and business model reconstruction seem to drive towards the interplay between the nature of Corporate Entrepreneurship and its strategic objectives.

21 In addition, it is not explored yet what the real practices through which CE may manifest are, and how they integrate with the above-mentioned forms of Corporate Entrepreneurship. To the best of my knowledge, in contemporary literature is lacking a CE model which encompasses and relates the theoretical with the practical perspectives.

In light of this, the aim of this dissertation is threefold. As first, it intends to identify and classify a comprehensive set of practices which manifest for how Corporate Entrepreneurship is performed by organizations. Secondly, it points at developing new theoretical prospects which can serve as new conceptualizations of CE forms. On behalf of these, the study ultimately aims at developing a framework for Corporate Entrepreneurship which can provide a complete view on this domain, spotting the fil rouge among all the factors peculiar to the CE journey.

The analysis will be grounded on five multiple case studies in the Italian energy sector, one of the most dynamic and uncertain arenas in the nowadays business environment (Accenture, 2018; Energy&Strategy, 2019b; World Economic Forum, 2018). Coherently with the research question, case studies examine different realities within the sector, thus to guarantee the applicability of the results across organization types (Eisenhardt, 1989). In details, case studies concern an Italian small/medium enterprise (SME)1 (Avvenia), an Italian public body (ENEA),

a France-based infant company operating in a variety of countries including Italy (Metron), and two Italian large corporations (Alperia, Enel). While Enel’s case study is based on secondary sources, others rely on interviews with general managers (Avvenia, Metron), strategy and innovation manager (Alperia) and lab director (ENEA).

1 Based on the Italian legislation, which defines a SME as a company with less than 250 employees and with

23

2. BACKGROUND

2.1 HISTORY AND DEFINITIONS

Before entering the Corporate Entrepreneurship domain, it is interesting to introduce the term “entrepreneurship”, as its meaning is precursory for CE’s definition as well.

The notions of entrepreneurship and entrepreneur have strongly evolved over time (Sharma & Chrisman, 1999) but the debate for a complete agreed-upon definition on this topic remains unsolved (Gartner, 1990). The earliest conceptualization of entrepreneurship is traced to Richard Cantillon (1734), who recognized the entrepreneur as someone who engages himself in profit-making, accepting the risk for uncertainty (Hébert & Link, 1989). Thereafter, entrepreneurial theories can be summarized into three major schools:

1. The German Tradition, by Schumpeter (1934), who perceived the entrepreneur as one “who carries out new combinations”, improving the status-quo. Schumpeter linked the entrepreneur with the concept of economic development, whose essence manifests in the “creative destruction” of existing resources (Hébert & Link, 1989).

2. The Chicago Tradition, by Schultz (1980), who defined entrepreneurship as "the ability to deal with disequilibria", extending this concept both to market and non-market activities. By linking entrepreneurship to disequilibria, Schultz relegated the domain of “uncertainty” to a marginal spot in the locus of entrepreneurship (Hébert & Link, 1989). 3. The Austrian Tradition, by Kirzner (1973), who explained entrepreneurship as a discovery process of profitable opportunities. Kirzner maintained the neoclassical perception of economics, with entrepreneurial processes acting as an equilibrating force for the market (Hébert & Link, 1989).

24 Despite the differences in the perspectives adopted by the three schools, and the various historical themes associated to entrepreneurship (e.g. risk, uncertainty, perception, creativity, change, exc.), it is noticeable how the overall essence of entrepreneurship is conductible to the willingness to pursue opportunity, regardless of the resources under control. Following this line of reasoning, entrepreneurship can be intended as the set of processes aiming at discovering and exploiting profitable (business) opportunities (Shane & Venkataraman, 2007).

Intuitively, the dominating logic to discover and pursue viable business opportunities finds consistency even in the construct of Corporate Entrepreneurship which, to some extent, complement and compete with the one of independent entrepreneurship (Sathe & Drucker, 2003). In fact, CE concept dates back to 1970s, when Western companies, after having focused on centralized R&D hubs as a consequence to Industrial Revolutions, noticed that to have the best science was insufficient, thereby searching for unconventional forms to realize economic value (Wolcott & Lippitz, 2010). Thus, some companies designed separated organizations with the goal to find and exploit opportunities even in businesses marginally related to their core ones (Wolcott & Lippitz, 2010). However, these teams often operated as versions of centralized R&D labs than like alternative corporate innovation hubs (Wolcott & Lippitz, 2010). It was the competitive threat arising from Asian manufacturers which, by 1980s, definitely pushed companies pursuing ambidextrous innovation models, such as corporate venturing (1990s) and R&D partnerships (2000s) (Katz & Shepherd, 2004). Globalization, digital technologies and startups waves further encouraged companies in rethinking their businesses and exploring new opportunities, ultimately establishing the strategic role of Corporate Entrepreneurship to sustain competitive advantage (Wolcott & Lippitz, 2010).

Contemporarily, even the emergence of academicians’ studies in the topic of Corporate Entrepreneurship contributed in increasing knowledge and interest in this domain.

25 The earliest researches, in the 1970s, mainly focused on venture teams and how they could be integrated within the organizational boundaries. Collins and Moore (1970) differentiated between “independent” and “administrative” entrepreneurs, with the former creating completely new organizations, while the latter developing new business entities within or adjunct to already established companies (Collins & Moore, 1970). Peterson and Berger (1971) adopted a Schumpeterian denotation of entrepreneurship, associated to innovation and defined as “an important component of leadership styles for organizational contexts facing with turbulent environments” (Peterson & Berger, 1971). Hill and Hlavacek’s (1972) contribution recognized product innovation as a necessary condition for a firm to satisfy increasingly dynamic marketplaces, emphasizing the role of venture teams as a valid alternative to bureaucratic corporate marketing (Hill & Hlavacek, 1972).

From 1980s, CE began to be identified as a process of organizational renewal, and a variety of conceptualizations started emerging (Table 1) (Kuratko, 2007; Kuratko & Audretsch, 2013). Burgelman (1983) defined CE as “the process whereby the firms engage in diversification through internal development. Such diversification requires new resource combinations to extend the firm's activities in areas unrelated, or marginally related, to its current domain of competence and corresponding opportunity set”. Also, Burgelman (1983) differentiated autonomous (i.e. outside the firm’s current structural context) and induced behaviour (i.e. fitting the firm’s strategic planning), suggesting the former as an important part of CE (Burgelman, 1983).

Miller’s (1983) defined CE as a company’s commitment to product-market innovation in existing businesses, describing an entrepreneurial firm as one which undertakes risky ventures and is first mover in “proactive” innovations (D. Miller, 1983). In time, Miller’s conceptualization evolved into an evaluation instrument for firm-level entrepreneurship, basing on the three related dimensions of product innovativeness, proactiveness and riskiness (Zahra,

26 Jennings, & Kuratko, 1999). For example, Morris and Sexton (1996) elaborated on Miller’s (1983) study to introduce the notion of entrepreneurial intensity. In details, they differentiated between the concepts of frequency and degree of entrepreneurial activities, with the former intending the quantity of initiative a company is engaged in, and the latter relying on the three dimensions of innovation, risk taking and proactiveness to define high-degree activities as those characterized by breakthrough developments (Kuratko, 2007; Sexton & Morris, 1996).

Consistently with Schumpeter’s notion of entrepreneurship and Miller’s definition of Corporate Entrepreneurship, Jennings and Lumpkin (1989) outlined CE as “the extent to which new products and/or new markets are developed”. More specifically, in their study of CE within the savings and loan industry, Jennings and Lumpkin (1989) defined any firm to be entrepreneurial in case it developed an above-average number of new products and/or new markets (Jennings & Lumpkin, 1989).

However, it was during 1990s that researches on Corporate Entrepreneurship definitely exploited, revealing the growing maturity of this domain among practitioners (Zahra, Jennings, et al., 1999). In this period, CE was mainly identified as a re-energizing phenomenon able to enhance firms’ capability to develop skills through which innovate. In addition, in 1990s, more comprehensive definitions of CE emerged too (Kuratko & Audretsch, 2013).

Guth and Ginsberg’s (1990) contribution in conceptualizing Corporate Entrepreneurship is agreed to be one of the most relevant in time. In fact, their definition of CE has been widely accepted during early 1990s, and it laid the foundations for the study of the forms CE may take. According to Guth and Ginsberg (1990), Corporate Entrepreneurship encompasses two major phenomena: the birth of new businesses within existing organizations (i.e. “corporate venturing”) and their transformation (or rebirth) through a renewal of their key ideas (i.e. “strategic renewal”) (Guth & Ginsberg, 1990). Guth and Ginsberg’s (1990) conceptualization

27 results to be similar to Burgelman’s (1983) one as both adopted a Schumpeterian perspective of innovation, i.e. based on new resource combinations. However, Guth and Ginsberg (1990) contributed in enlarging the domain of Corporate Entrepreneurship, as they introduced the interaction between new businesses and new combinations, which can both be functional but not confined to diversification (Sharma & Chrisman, 1999).

Covin and Slevin (1991) quoted Burgelman (1983) in their definition of CE, which “involves extending the firm's domain of competence and corresponding opportunity set through internally generated new resource combinations”. They adopted a firm behaviour perspective to define entrepreneurial firms as those characterized by an entrepreneurial posture, represented by Miller’s (1983) three dimensions of product innovativeness, risk-taking propensity and tendency to act in “competitively aggressive, proactive manners” (Covin & Slevin, 1991).

Zahra (1991) elaborated on Burgelman’s (1983) distinction between induced and autonomous activities to further deepen Guth and Ginsberg’s (1990) definition of CE. Specifically, Zahra’s (1991) CE encompasses both formal activities (i.e. developed in pursuit of the firm's established mission and goals) and informal ones (i.e. those initiated by individuals and groups in pursuit of particular areas of interest), which can take place at the corporate, division, functional or project levels, with the final aim of improving a company’s competitive position and financial performance. This can be done either by mean of innovation-driven new business creation within an existing organization, or through its renewal (Zahra, 1991).

Covin and Miles (1999) envisioned innovation as the commonality among all entrepreneurial firms but proposing Corporate Entrepreneurship as multidimensional set of phenomena having “something more” than innovation. Specifically, they defined CE as “the presence of innovation plus the presence of the objective of rejuvenating or purposefully redefining organizations, markets, or industries in order to create or sustain competitive superiority”. In

28 fact, they related CE to efforts of renewal, regeneration, redefinition and rejuvenation of organizations themselves, their markets or industries (Covin & Miles, 1999).

After an in-depth study of Corporate Entrepreneurship’s conceptualizations, Sharma and Chrisman (1999) followed and further explored the school of thoughts initiated by Guth and Ginsberg (1990) and prosecuted by Zahra (1991), intending Corporate Entrepreneurship as “the process whereby an individual or a group of individuals, in association with an existing organization, create a new organization or instigate renewal or innovation within that organization”. In details, they associated CE to three distinct forms: strategic renewal, Schumpeterian innovation (i.e. an original invention or idea introduced to the marketplace which has the potential to transform the competitive environment and the organization itself), and corporate venturing, both internal (in case of organizational entities that reside within the existing organizational domain) and external (in case of semi-autonomous or autonomous organizational entities that reside outside the existing organizational domain) (Corbett et al., 2013; Sharma & Chrisman, 1999).

Basing on all these different definitions of CE, the 21st century ultimately related this arena to firms’ efforts to maintain competitive advantage (Kuratko, 2007; Kuratko et al., 2005). Despite the maturity of CE definitions, some further fundamental contributions can be still recognized.

Ireland, Kuratko and Morris (2006) conceived employees engaging in entrepreneurial behaviour as the foundation for organizational innovation, thus defining CE as the “process through which individuals in an established firm pursue entrepreneurial opportunities to innovate without regard to the level and nature of currently available resources. Entrepreneurial opportunities are situations in which new products (goods or services) can be sold at a price exceeding their cost of development, distribution and support”. Thus, effective CE can lead companies both to improved financial performances (e.g. by pursuing entrepreneurial

29 opportunities) and to non-financial achievements (e.g. increase in organizational knowledge to encourage entrepreneurial behaviour) (Ireland, Kuratko, & Morris, 2006). In a subsequent study, Ireland, Covin and Kuratko (2009) further strengthened the position of CE as a source of competitive advantage, analysing it as a strategy, and defining it as “a vision-directed, organization-wide reliance on entrepreneurial behaviour that purposefully and continuously rejuvenates the organization and shapes the scope of its operations through the recognition and exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunity” (Ireland, Covin, & Kuratko, 2009).

Thinking of innovation as a necessary condition for companies’ survival in the nowadays global markets, Kuratko, Hornsby and Covin (2014) defined CE as “a significant form of corporate innovation, envisioned to be a process that can facilitate firms’ efforts to innovate constantly and cope effectively with the competitive realities companies encounter when competing in world markets”. Authors related CE to firms’ internal environment, observing that Corporate Entrepreneurship tends to flourish “when individuals are free to pursue actions and initiatives, regardless of their role” (Kuratko et al., 2014).

To conclude, the theoretical and empirical knowledge around the CE domain strongly evolved over time, as a sign of the recognition of its significance for firms’ competitive advantage. However, literature admits a fundamental ambiguity in the CE construct, mainly due to the proliferation of inorganic definitions, to the adoption of different terminologies to express similar concepts, and, relatedly, to lack of clarity in respect of other constructs (Corbett et al., 2013; Covin & Miles, 1999; Holt, Rutherford, & Clohessy, 2007; Kuratko, 2007; Sharma & Chrisman, 1999).

First, CE has been interchangeably associated to a variety of labels, such as internal corporate entrepreneurship (Schollhammer, 1982; Vesper, 1984), intrapreneurship (Birkinshaw, 1997; Carrier, 1994, 1996; Hornsby, Naffziger, Kuratko, & Montagno, 1993; Kuratko et al., 1990;

30 Parker, 2011), or corporate venturing (Biggadike, 1979; Birkinshaw, 1997; Kuratko et al., 2004; Parker, 2011), although the various terminologies have not the same meaning. Also, in some cases, definitions and labels adopted seemed to be unrelated. For instance, Vesper (1984) intended internal CE as “employee initiatives from below in the organization to undertake something new. An innovation which is created by subordinates without being asked, expected, or perhaps even given permission by higher management to do so” (Vesper, 1984). However, this definition strongly overlaps with already stated Toftoy’s (2001) conceptualization of intrapreneurship, intended as “employee initiatives to undertake something new within an organization, despite not asked to do so” (Toftoy et al., 2001). Another controversial example regards Biggadike’s (1979) definition of corporate venturing and Burgelman’s (1983) CE. In fact, Biggadike (1979) observed corporate venturing as "marketing a product or service that the parent company has not previously marketed and that requires the parent company to obtain new equipment or new people or new knowledge" (Biggadike, 1979), thus not limiting the firm’s scope to areas unrelated to its current business domain, oppositely to Burgelman’s definition of CE. Therefore, Biggadike’s (1979) conceptualization seems to contain Burgelman’s (1983) one, despite corporate venturing is widely agreed to be included in the domain of CE (Sharma & Chrisman, 1999).

Second, Corporate Entrepreneurship has been widely perceived as a phenomenon implying the presence of innovation. However, there is more on Corporate Entrepreneurship than innovation (Covin & Miles, 1999). For example, the mere adoption of new technologies not necessarily evoke firm-level entrepreneurial efforts. In time, some theorists provided for definitions of Corporate Entrepreneurship which strongly overlapped with corporate innovation. For example, Burgelman’s (1983) association of CE with diversification processes or Jennings and Lumpkin (1989)’s correlation to the introduction of new products and/or markets exhibit for vagueness in the logical disconnection between the two constructs. In other cases, theorists

31 attempted to differentiate Corporate Entrepreneurship from pure innovation, often recalling for attributes such as proactiveness and riskiness. Although idiosyncratic of entrepreneurial behaviour, I believe that the prior element which differentiates entrepreneurial from innovative initiatives is the presence of a business-orientation. For example, patenting does not entail for entrepreneurial behaviour per se, as it may happen for patents to remain unexploited in organizations. In this case, innovation has occurred by definition. But firm-level entrepreneurship would have requested for a step more, i.e. the business exploitation of the patent, indeed.

Hence, grounding on past foundations, considering Corporate Entrepreneurship’s strategic relevance in nowadays market environments (Barringer & Bluedorn, 1999; Covin & Miles, 1999; Dess, Lumpkin, & Mcgee, 1999; Ireland et al., 2009), innovation as its major affiliate (Ireland et al., 2006; Kuratko & Audretsch, 2013; Kuratko et al., 2014; D. Miller, 1983; Sharma & Chrisman, 1999), and prompting at clarifying the relationships among the two constructs, I propose the following definition of Corporate Entrepreneurship:

Corporate Entrepreneurship is a paradigm encompassing new entries, entrepreneurial recombination of existing resources or, broadly speaking, business-oriented innovations which purposefully energize the organization in an attempt to improve its competitive standing.

32

Definitions of Corporate Entrepreneurship

Year Author(s) Definition

1983 Burgelman

“Corporate Entrepreneurship is the process whereby the firms engage in diversification through internal development. Such diversification requires new resource combinations to extend the firm's activities in areas unrelated, or marginally related, to its current domain of competence and corresponding opportunity set”.

1983 Miller

“An entrepreneurial firm is one that engages in product-market

innovation, undertakes somewhat risky ventures, and is first to come

up with "proactive" innovations, beating competitors to the punch”.

1984 Vesper

“(Internal) Corporate Entrepreneurship involves employee

initiative from below in the organization to undertake something

new. An innovation which is created by subordinates without being asked, expected, or perhaps even given permission by higher management to do so.”

1989 Jennings, Lumpkin

“Corporate entrepreneurship is defined as the extent to which new

products and/or new markets are developed. An organization is

entrepreneurial if it develops a higher than average number of new products and/or new markets”.

1990 Guth,

Ginsberg

“Corporate entrepreneurship encompasses two types of phenomena and the processes surrounding them: (1) the birth of new businesses within existing organizations, i.e. internal innovation or venturing; and (2) the transformation of organizations through renewal of the key ideas on which they are built, i.e. strategic renewal”.

1991 Covin,

Slevin

“Corporate Entrepreneurship involves extending the firm's domain of competence and corresponding opportunity set through internally generated new resource combinations”.

33

1991 Zahra

“Corporate Entrepreneurship refers to formal and informal activities aimed at creating new business in established companies through product and process innovations and market developments. These activities may take place at the corporate, division (business), functional, or project levels, with the unifying objective of improving a company’s competitive position and financial performance. Corporate entrepreneurship also entails the strategic renewal of an existing business".

1999 Covin,

Miles

“Corporate entrepreneurship is the presence of innovation plus the presence of the objective of rejuvenating or purposefully redefining organizations, markets, or industries in order to create or sustain competitive superiority”.

1999 Sharma,

Chrisman

“Corporate entrepreneurship is the process whereby an individual or a group of individuals, in association with an existing organization, create a new organization or instigate renewal or

innovation within that organization”.

2006

Ireland, Kuratko,

Morris

“Corporate entrepreneurship is a process through which individuals in an established firm pursue entrepreneurial opportunities to innovate without regard to the level and nature of currently available resources. Entrepreneurial opportunities are situations in which new products (goods or services) can be sold at a price exceeding their cost of development, distribution and support”.

2009

Ireland, Covin, Kuratko

“Corporate Entrepreneurship strategy is defined as a

vision-directed, organization-wide reliance on entrepreneurial behaviour

that purposefully and continuously rejuvenates the organization and shapes the scope of its operations through the recognition and

exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunity”.

2014

Kuratko, Hornsby, Covin

“Corporate entrepreneurship – a significant form of corporate innovation – is envisioned to be a process that can facilitate firms’ efforts to innovate constantly and cope effectively with the competitive realities companies encounter when competing in world markets”.

34

2.2 TRIGGERS AND ANTECEDENTS TO “CE”

Literature has widely recognized that proper conditions can best push companies to innovate. For example, Peterson and Berger’s (1971) noticed how entrepreneurial practices within the popular music industry were subject to the degree of market turbulence, i.e. of unpredictable changes (Peterson & Berger, 1971). Similarly, even endogenous factors to a firm’s context, as its culture, have been found to play a major role in anticipating entrepreneurial activities. Broadly speaking, early researchers have distinguished among transformational triggers and organizational antecedents. Although both the factors impact on the occurrence of entrepreneurial acts, thus often simultaneously treated, a slight difference exists between them. Namely, while transformational triggers provoke an entrepreneurial behaviour to occur, organizational antecedents mainly predispose the internal environment to entrepreneurial behaviour.

2.2.1 TRANSFORMATIONAL TRIGGERS

Broadly speaking, contemporary literature differentiates transformational triggers into external and internal compared to organizational context.

There is general consensus among practitioners in attributing to the external environment the greatest pressure for entrepreneurial behaviour (Covin & Slevin, 1991; Ireland et al., 2009, 2006; Zahra, 1991). Environmental factors impacting on Corporate Entrepreneurship have been object of a variety of studies. In fact, if in one hand research has widely attempted to develop exhaustive list of external triggers to CE (Schindehutte et al., 2000; Zahra, 1993b), in the other hand such parameters have been included even in studies developing frameworks or normative models for Corporate Entrepreneurship (Antoncic & Hisrich, 2004; Barringer & Bluedorn, 1999; Covin & Slevin, 1991; Zahra, 1991, 1996).

35 Relatedly, two main perspectives in dealing with the analysis of external triggers to CE can be outlined. First, theorists have attempted in outlining some macro-constructs that could well synthetize environmental conditions shaping either businesses’ opportunities or threats (Zahra, 1991, 1993b). Second, a broad array of research has developed more punctual analyses of the triggers to CE, thus developing lists of these factors, or testing in-depth one or some’s influence on a firm’s entrepreneurial openness (Barringer & Bluedorn, 1999; Zahra, 1991, 1996).

In terms of external macro-constructs, Zahra (1991) observed that environmental dynamism, hostility and heterogeneity are all conducive factors for firms’ entrepreneurial efforts (Zahra, 1991). In details, environmental dynamism refers to market instabilities due to changes of various nature, as social, political, technological and economic; these shifts can create turmoil in business scenarios, shaping new opportunities and threats and prompting companies to act creatively and innovatively (Antoncic & Hisrich, 2004; Covin & Slevin, 1991; D. Miller & Friesen, 1982; Zahra, 1991, 1993a, 1993b; Zahra, Filatotchev, & Wright, 2009). Further, a

hostile environment is intended as adverse to a firm’s mission. Environmental hostility is a

phenomenon which can be caused by several sub-elements, such as increasing rivalry, depressing demand, exc. Anyway, in such conditions, an organization is forced to innovate products, processes and routines (at least) to maintain its competitive position (Covin & Slevin, 1991; Kuratko et al., 2014; D. Miller & Friesen, 1982; Zahra, 1991, 1993b; Zahra & Covin, 1995). In the end, environmental heterogeneity refers to the existence of multiple segments, with varied characteristics and needs, that can be potentially served by a firm. Thereby, it is a construct which implies business opportunities, which can be properly leveraged by firms able to innovate and satisfy the expectations of diverse market segments (D. Miller & Friesen, 1982; Sexton & Morris, 1996; Zahra, 1991). However, this latter construct appears to be redundant with environmental hostility. In fact, consider a case in which clients are homogeneous and concentrated (low heterogeneity); this would cause by definition an increase in environmental

36 hostility. But, oppositely, it cannot be stated that hostile environments are certainly attributable to market homogeneity.

In a posterior study, Zahra (1993) englobed the above-mentioned environmental dynamism into a new construct, namely environmental munificence. This parameter reflects the abundancy of opportunities in the market, thus embodying not only dynamism, but also technological opportunities (i.e. the perception of demand for new technologies in the market), industry growth (i.e. the perception of the demand for industry products), and the importance of new products for creating and retaining a competitive position (Zahra, 1993b, 1993a). However, dynamism is a construct which does not always reflect the abundancy of opportunities in the market; rather, there are some cases in which environmental shifts can create uncertainty and threats for firms’ businesses, despite dynamism pushing them to innovate. For example, market deregulation and liberalization strongly challenged monopolistic firms to reshape their businesses, often complying with the constraints imposed by normative requirements too. In light of this, dynamism and munificence results to be two constructs that should be processed independently each other.

Elaborating on this arguments, it emerges that three macro-constructs for environmental triggers to Corporate Entrepreneurship can coexist: dynamism, hostility and munificence. These variables properly shape the nature of an industry, thus allowing to outline its relationship with entrepreneurial activity. The adoption of these three macro-construct as triggers to CE is not new in literature; rather, it results to be coherent with Zahra’s (1993) critique and extension to Covin and Slevin’s (1991) conceptual framework of “entrepreneurship as firm behaviour” (Zahra, 1993a).

Despite the above-mentioned macro-constructs optimally serve to outline certain conditions of the external environment, it is absolutely crucial to unbundle their causing factors in order to

37 have a comprehensive view on the external triggers to CE (Figure 1). Surely, the list of events exogeneous to a firm’s context that can originate environmental dynamism, hostility and munificence is almost limitless. Considering the complexity of the problem, the focus is turned mainly on the factors of highest relevance from theorists’ perspective.

A first intuitive precursor to Corporate Entrepreneurship is policy change (Guth & Ginsberg, 1990; Holmes, Zahra, Hoskisson, Deghetto, & Sutton, 2016; Schindehutte et al., 2000; Zahra, 1991, 1993b), which can cause both environmental dynamism, hostility and munificence. For example, depending on their nature, regulatory developments can either cause an increase of business hostility (e.g. higher taxation), or munificence (e.g. incentives). Anyway, market changes happen in both the cases, increasing environmental dynamism, and pushing companies to innovate in order to survive or to exploit new opportunities respectively. There is a wide array of policies which can impact on firms’ CE strategy indeed, as governments and institutions are responsible for the definition of the market structure, research funds, intellectual property right regimes, access to education, exc. In fact, public policies result to set the stage for innovation, thus influencing firm-level entrepreneurship.

Similarly and roughly relatedly, economic changes influence entrepreneurial activities as well (Guth & Ginsberg, 1990; Schindehutte et al., 2000; Zahra, 1991, 1993b). For example, rising costs can threaten firms’ profitability, thus making the environment more hostile, and pushing them to innovate in order to survive. However, the relationship between CE activities and economic changes such as increased costs can be not linear: in scenarios of resource shortage, companies may link survival to expenses reduction, e.g. by divesting from some ventures, rather than to the adoption of a long-term innovation-centred perspective. In these cases, entrepreneurial efforts result to be discouraged rather than favoured.

38 Further, even social context impacts on organizations’ entrepreneurial efforts (Guth & Ginsberg, 1990; Schindehutte et al., 2000). For example, by mean of an exploratory study tackling 20 large companies, Schindehutte, Morris and Kuratko (2000) observed that change in people’s lifestyles is one of the principal external triggers to Corporate Entrepreneurship (Schindehutte et al., 2000). Being people’s lifestyles directly related to their needs, changes in this dimension can differently shape business environment, creating opportunities or adversities depending on a firm’s mission. Also, external stakeholders’ attention for environmental issues may push companies in adopting Corporate Entrepreneurship to pursue sustainable innovation models.

Technological shifts (Antoncic & Hisrich, 2004; Covin & Slevin, 1991; Ireland et al., 2009;

Schindehutte et al., 2000; Zahra, 1991, 1993b, 1996) are a source both of opportunities and threats within business environments, and impacts both in environmental dynamism, hostility and munificence. In fact, the availability of new technologies can cause demand for new products, either in a firm’s current market or in adjacent ones, but it can even lead to existent technologies’ obsolescence, which result to be eroded. In both the cases, companies are required to be agile and to innovate ahead of their competitors, in a way to achieve competitive superiority. Therefore, fast technological environments are associated positively with increased corporate entrepreneurship.

Another widely-recognized trigger to CE is competitive rivalry, which can cause both environmental dynamism, hostility and munificence (Barringer & Bluedorn, 1999; Ireland et al., 2009; Schindehutte et al., 2000; Zahra, 1991, 1993b). For example, a new entry within the market can cause unbalances in its equilibrium (dynamism), threats to firms’ missions due to higher number of competitors (hostility), and an erosion of existent market opportunities (munificence). Overall, high-competitiveness scenarios are related to short-living competitive advantages. Thus, companies must innovate products and processes, explore new markets and

39 rejuvenate themselves in a way to safeguard their market share. For these reasons, markets characterized by high rivalry are intuitively conducive to entrepreneurial efforts within organizations.

Lastly, even demand changes strongly affiliate to CE (Antoncic & Hisrich, 2004; Ireland et al., 2009; Schindehutte et al., 2000; Zahra, 1991, 1993b) and can cause both environmental dynamism, hostility and munificence. In fact, in one hand, demand changes can be related to a specific industry growth, hence to the perceived demand for such industry products; in cases in which this demand decreases, companies are required for a change in the competitive posture, thereby embracing entrepreneurial activities to rejuvenate. In the other hand, demand changes can be even anticipatory of new customers’ requests, thus creating opportunities for successful new products introduction, achievable by mean of products, processes and routines innovation. In light of this, demand changes are definitely assumed to influence companies’ entrepreneurial efforts.

40 Each of the above-mentioned factors differently shapes environmental dynamism, hostility and munificence, thus influencing Corporate Entrepreneurship activities. However, apart from triggers per se, it is the perception of the business environment that differently frames the sense of urgency for a company to pursue entrepreneurial actions (Carrier, 1996; Ireland et al., 2009; Kuratko et al., 2004; Schindehutte et al., 2000; Zahra, 1993b). Thus, peculiar external environment conditions result anticipatory of CE mainly in cases in which they are actually perceived by the company, and as a function of this perception rather than of their objective characteristics. In this respect, briefly anticipating firm-level antecedents’ contribution, the roles of organizational members result to be absolutely crucial, as pro-entrepreneurial cognitions can further enhance the positive association between external triggers and CE (Ireland et al., 2009; Zahra, 1993b).

When it comes to internal triggers, early research recognizes for two main factors anticipating Corporate Entrepreneurship: corporate strategy and change management. As first, CE is strongly supported by growth strategies, while “conservative” strategic directions can preclude entrepreneurial actions by definition, thereby threatening the formation of a proper entrepreneurial-oriented internal ecosystem (Zahra, 1991). In this direction, the presence of specific growth-oriented strategic programmes within the organization can actually manifest as a precipitating event for entrepreneurial behaviour to occur (Schindehutte et al., 2000). Secondly and lastly, change management often links to strategic re-orientations. On behalf of this, relatedly to what seen before for growth strategies, and dependently on the peculiarities of the new management, new visions indeed can prioritize for the implementation of entrepreneurial actions (Kuratko et al., 2004).

2.2.2 ORGANIZATIONAL ANTECEDENTS

The internal environment to an organization has been widely agreed to be either a facilitatory or a discouraging factor to firm entrepreneurial behaviour. Early research defined the concept

41 of entrepreneurial orientation (EO) to differentiate between companies that engage in successful Corporate Entrepreneurship from those which do not. Entrepreneurial orientation is intended as the set of “methods, practices and decision-making styles managers use to act entrepreneurially”, and involves five key firm-level dimensions: autonomy, innovativeness, risk taking, proactiveness and competitive aggressiveness. Whether an entrepreneurial firm should exhibit all these five factors still remains unclear; however, the presence of at least some of them well serve to characterize entrepreneurial-oriented environments (Covin & Miles, 1999; Dess & Lumpkin, 2005; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996).

As for the external triggers to CE, research in the field of organizational antecedents is vast and expanding. In time, particular attention has been given to topics as firm’s incentive and control systems (Jones & Butler, 1992), culture (Brazeal, 1993; Burgelman, 1983; Chung & Gibbonds, 1997), organizational structure (Dess et al., 1999), the role of management at multiple levels (Kuratko et al., 2005; Phan, Wright, Ucbasaran, & Tan, 2009; Stevenson & Jarillo, 2007), governance (Abor & Adjasi, 2007; Zahra, 1996; Zahra, Neubaum, & Huse, 2000), organizational values (Simsek & Heavey, 2011; Zahra et al., 2009), and operations (Goodale, Kuratko, Hornsby, & Covin, 2011). Indeed, these factors have been found to affect the nature of the firm’s internal environment, thereby influencing the breadth and depth of its entrepreneurial behaviour.

Despite the array of organizational factors influencing Corporate Entrepreneurship is extremely wide, the literature roughly converges to Hornsby, Kuratko, Zahra’s (2002) five internal antecedents to entrepreneurial behaviour: management support, work discretion/autonomy, rewards/reinforcement, time availability, and organizational boundaries (Hornsby et al., 2002).

Entering into the details of the above-mentioned antecedents to CE, management support refers to the extent to which managers encourage organizational members in pursuing

42 innovation. In turn, this means to intend innovation as part of the role set for all employees (Hornsby et al., 1993), to devote the necessary resources (Hornsby et al., 2002, 1993; Kuratko, 2007; Kuratko et al., 2005), and to champion innovative ideas (Hornsby et al., 1993; Kuratko, 2007; Kuratko et al., 2005). Management support has been found to have a direct positive relationship to the breadth and depth of Corporate Entrepreneurship. However, to properly promote entrepreneurial behaviour, contribution of management at multiple levels is needed. Specifically, executes play the crucial role to set strategic decisions, often based on the perceived external environment, thus influencing the emergence of an entrepreneurial strategic vision. But then, middle managers are in charge to effectively convey these expectations to the operational level, by actually implementing entrepreneurial activities; in fact, middle managers’ task is to handle entrepreneurial opportunities and to organize resources to pursue those opportunities. Overall, executives and middle managers set the ground for CE, determining objectives, resources and competences to be employed, shaping cultural norms, and affecting firm’s performance (Ireland et al., 2009; Kuratko et al., 2005).

Work discretion/autonomy means to guarantee employees’ discretionality in working in the

way they consider most effective, avoiding critiques in case mistakes emerge in the pathway to innovation. Thereby, an organizational ecosystem distinctive for work discretion and autonomy is typically characterized by top managers’ failure toleration, “risk-taking” as a positive attribute, mistakes as learning experiences, decision-making flexibility and freedom from excessive oversight, and lower-level managers and workers’ authority and accountability in innovation processes (Goodale et al., 2011; Hornsby et al., 2002; Kuratko, 2007; Kuratko et al., 2014, 2005, 1990). A wide array of studies demonstrate that work discretion and autonomy positively contribute in recognizing and pursuing entrepreneurial opportunities, thus being supportive to CE (Beal, 2000; Holt et al., 2007; Hornsby et al., 1993; Kuratko, 2001; Lang, Calantone, & Gudmundso, 1997).

43

Rewards/reinforcement systems have been object of extensive research. In fact, they are

considered as the most critical determinant of CE (Kuratko et al., 1990), as they contribute in encouraging entrepreneurial behaviour (Rutherford & Holt, 2007), retaining innovative employees who may have propensity to prosecute on their own (Hornsby et al., 2002), and in shaping an appropriate entrepreneurial culture (Zahra, Nielsen, & Bogner, 1999). Therefore, it naturally emerges how organizations should provide rewards based on entrepreneurial activity and success, highlight significant achievement, and stimulate the pursuit of challenging work (Goodale et al., 2011; Kuratko, 2007; Kuratko et al., 2005). However, any reward system is not effective a priori. Rather, it should consider goals, feedback, emphasis on individual responsibility, and rewards based on results (Hornsby et al., 1993). In this way, an organizational reward system is actually positively related to the probability that individuals will better recognize and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities, thereby being conducive to Corporate Entrepreneurship (Holt et al., 2007; Ireland et al., 2009).7

Time availability refers to the management of workloads in a way to ensure that individuals

and groups can devote time to innovation, thus empowering them to pursue both short-term and long-term organizational goals (Goodale et al., 2011; Kuratko, 2007; Kuratko et al., 2005). Several theorists suggest that this dimension is conducive to Corporate Entrepreneurship, as unstructured time can enable innovative employees to consider entrepreneurial opportunities that may be hindered by their required work schedules (Shepherd, Mcmullen, & Jennings, 2007). Nevertheless, in some cases, time availability appeared to be unrelated to CE (Holt et al., 2007; Hornsby, Kuratko, & Montagno, 1999). Therefore, it is arguable that this dimension is a necessary but not sufficient condition for entrepreneurial behaviour to expand within an organization. Namely, time constraints can actually impede CE, but free time may not be precursory of entrepreneurial actions per se, if not supported by a proper corporate entrepreneurial culture.