Academic Year 2016/2017 Corso di perfezionamento/dotoratto in Politics,

Human Rights and Sustainability

LANGUAGE POLICY OF POST-SOVIET KAZAKHSTAN:

CONSTRAINS, CHALLENGES AND PERSPECTIVES

Author Ayan Zhibitayeva Supervisor Professor Barbara Henry

D265ModTPhD/EN00

Table of Contents

Introduction ...5

Statement of problem ...5

Structure of the thesis...11

Chapter I. Challenges and constraints in language policy and planning in Kazakhstan...14

1. Language loss and shift: Why do languages decline? ...14

1.1. Linguistic homogeneity vs. linguistic diversity ...18

1.2. The nation-state and (linguistic) minorities: Sovereignty, territorial integrity and self-determination ...19

2. Linguistic diversity accommodation: why care? ...24

2.1. Language and identity link ...24

a) The centrality of language to ethnicity and culture ...26

2.2. Language as an intangible cultural heritage ...30

3. Language policy and planning: Definitions ...32

3.1. Types of language policies and planning ...34

3.2. Approaches to language policy and planning ...35

3.2.1. Language rights approach ...36

3.2.1.1. Conceptualization of language rights ...36

a) Toleration rights...37

b) Promotion-oriented rights...39

i) Education ...48

ii) Media...50

3.2.2. Linguistic human rights ...52

3.2.3. Language ecology approach ...53

4. Two models of languages’ coexistence in the same country: territoriality vs. individual principle 54 5. Distinctiveness of Post-Soviet Kazakhstan’s linguistic situation ...59

5.1. Remedial language policies ...59

5.2. ‘Post-imperialist linguistic situations’ ...62

Chapter II. The historical background of linguistic situation in Kazakhstan as well the role of language in post- independence nation-building process ...67

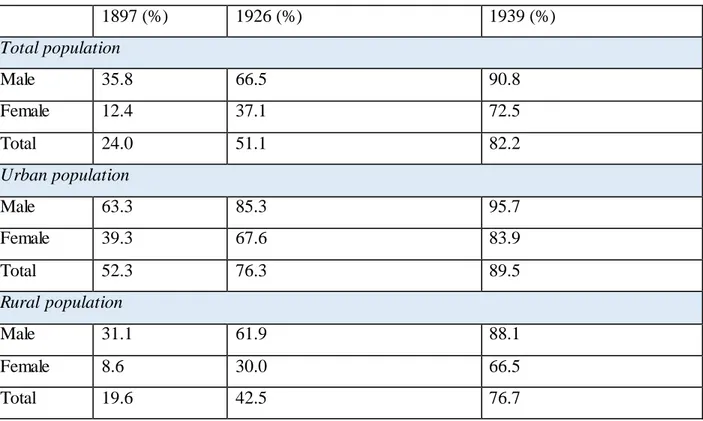

1. Historic overview of the language situation in Kazakhstan from 1731-1991 ...67

2. Linguistic situation in Kazakhstan prior to 1917 ...67

2.1. The ‘tatarization’ of the Steppe ...70

2.2. De-tatarisation and russification attempts of the Kazakh steppe ...72

2.3. Changing socio-economic and political environment and its impact on Kazakh language and culture...74

2.4. The rise of Kazakh nationalistic movements in the late colonial period ...78

3. Soviet Language and Nationality policies ...80

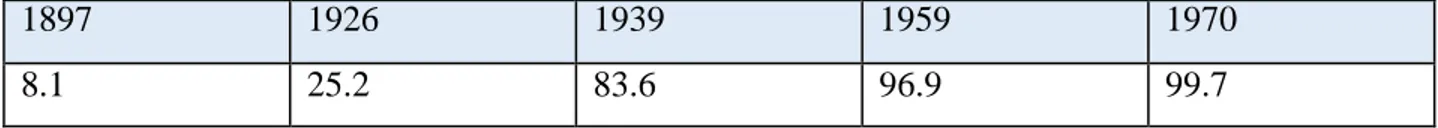

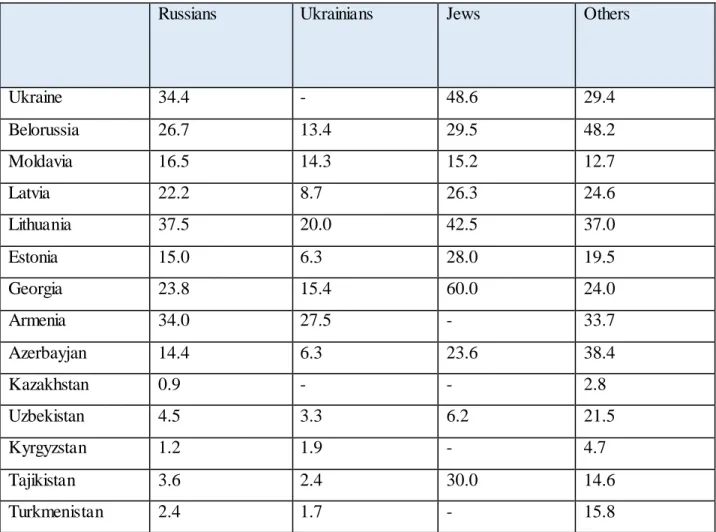

3.1. Early-Soviet years’ language policy and korenizatsya ...83

3.2. The alphabetic reforms...87

3.3. Post 1930s Russification policies ...90

3.4. The linguistic situation in the Late-Soviet years of ‘glasnost’ and perestroika’ ...92

4. Continuities and discontinuities in Tsarist and Russian regimes and applicability of post -colonialism theory to post-Soviet Kazakhstan ...94

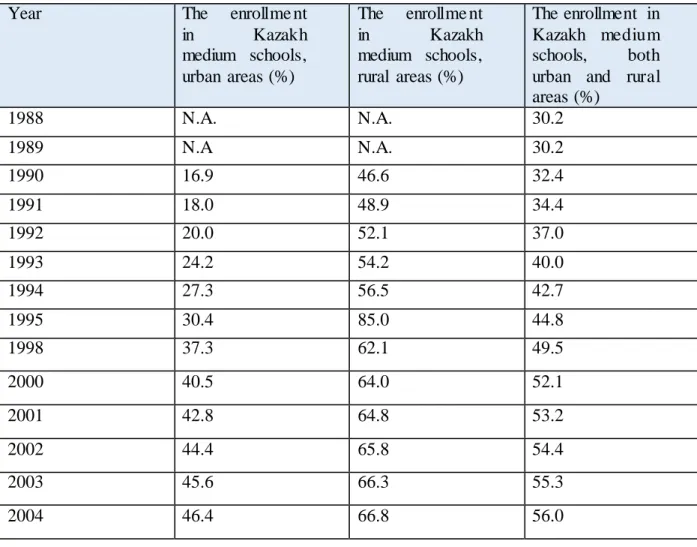

5. Post-Independence nation-building and language policies: Kazakhisation ...100

5.1. Analyzing the term ‘Kazakhisation’ and its use in academic and social discourses ...106

Chapter III. Language policy of Kazakhstan and mechanisms of its implementation ...110

1. Analysis of the Constitution and legal documents regulating the languages ...110

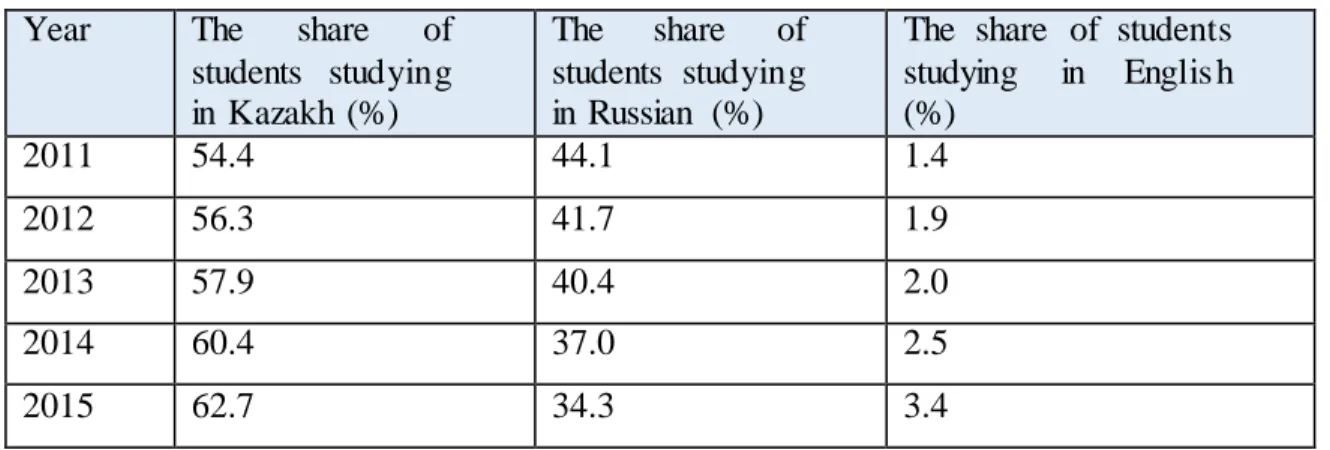

1.2. Language in Education planning ...114

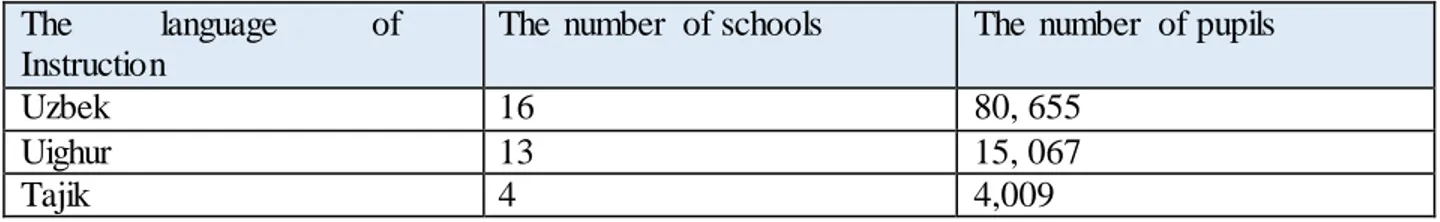

1.1.1. Education in minority languages ...116

1.1.2. Higher Education ...118

1.3. Language issues in public authority bodies ...122

2. Languages related official policy documents ...122

2.1. National Doctrine of Kazakhstan ...124

2.2. “State programs on functioning and development of languages” ...125

2.3. Address to the people of Kazakhstan-2050 ...126

3. New trends in Language policy of Kazakhstan...128

3.1. Trinity of Languages ...128

3.2. Latin alphabet discussions’ renewal ...130

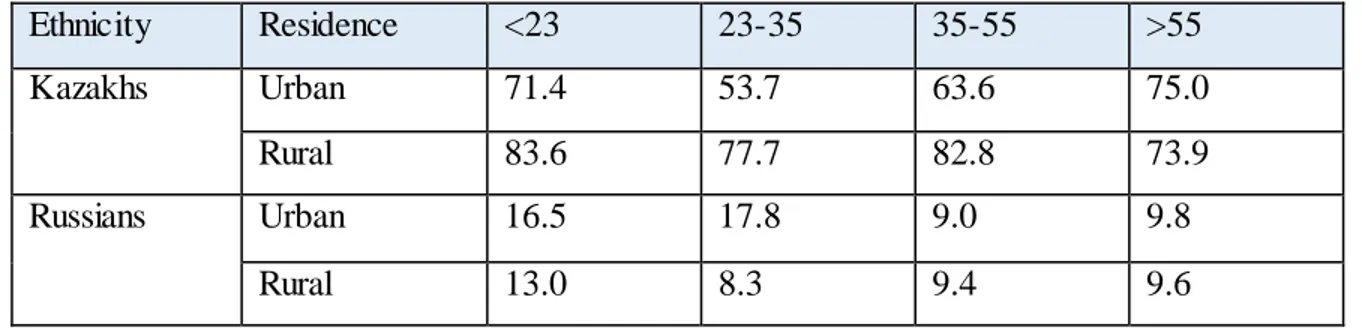

4. Language policy implementation...131

5. On language policy achievements ...134

Conclusion ...138

Bibliography...141

Introduction

Statement of problem

Languages issue in post-Soviet states is a topic of broad and current interest both in academia and in politics. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, its successor states initiated nationalizing projects with the aim of redressing the legacies of Soviet nationalities and language policies, which were most manifested in the dominance of Russian language and asymmetrical bilingualism. The promotion and prioritization of titular languages are commonly referred to as being part of the traditional ‘nationalizing strategies and practices’1, while only a minority of the relevant literature defines them as ‘remedial policies’2. The difference between the two approaches may seem of secondary importance at first, but assumes a fundamental role in determining the relevant language policies if one analyses the two concepts more in-depth. If indeed the ‘nationalizing approach’ implies – at least indirectly – the discrimination of the non-titular groups, the remedial view accommodates more easily language policies which are aimed at compensating past injustices, thus on this basis justifying to a limited extent the discrimination.

Remedial measures in language policies have been adopted by post-soviet republics to a varying degree, from more radical in Latvia and Estonia, to soberer in Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan3. Despite the substantial differences among these state-policies, they are often all deemed discriminatory.

This situation is common to many post-colonial states across the globe, which also strive for post-independence national transformation and justice4. The cases of other post-colonial states, such as African and Asian countries, nonetheless, differ from those of Soviet successors republics in many ways. Firstly, the equation of ‘post’ in soviet with the ‘post’ in post-colonial is highly contested, which implies questioning the very legitimacy of (ethnic)

1

See: Rogers Brubaker, National M inorities, Nationalizing States, and External national Homelands in the New Europe’ [1995] Daedalus, Vol.124 №2; Aneta Pavlenko, ‘Russian as a lingua franca’ [2006] Annual Review of Applied linguistics,vol.26; Bhavna Dave, ‘National revival in Kazakhstan: Language shift and Identity change’ [1996] Post-Soviet Affairs 12(1), p. 131

2 Lara Ryazanova-Clarke, The Russian Language Outside the Nation, (Edinburgh University Press, 2013); M aarja Siiner, Kadri

Koreinik, Kara D. Brown, Language Policy Beyond the State (Springer 2017), p.28; Renata M atuszkiewicz, ‘The language issue in Kazakhstan – institutionalizing new ethnic relations after independence’ [2010] Economic and Environmental Studies Vol. 10, No. 2,211-227

3 Ryazanova-Clarke (n3) 4

building enterprises of the post-soviet republics5. Secondly, the linguistic situations in the different post-colonial regions vary considerably, with most African states having to deal with the competing claims for domination of numerous indigenous languages. By contrast, in some of the soviet successor states vulnerable titular languages have to compete with stronger Russian. Whereas the grounds are fundamentally different, yet the consequences of these dynamics result in a similar pattern: languages of ex-colonial powers (English, French, and Russian) continue dominating in these polities.

It is remarkable that the post-independence language policies, pursued by soviet successor states are anything but homogeneous. Pavlenko distinguishes five categories of post-Soviet states in terms of language issue management:

“(i) dual-language policy with Russian functioning de-facto as the main langua ge (Belarus); (ii) dual-language policy with titular language as the state language and Russian as an official language or the language of interethnic communicat io n (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan); (iii) single language policy with de-facto bilingualism in the titular language and Russian (Ukraine), (iv) single language policy with Russian functioning de-facto in some public contexts (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan); and (v) single language policy with the titular language as the main language both de jure and de-facto (Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania)”6

These differing approaches to managing the language issue can be attributed to factors such as the conditions of each state’s incorporation into the expanding Russia in the past as well as the character of their relationships nowadays. Furthermore, the share of Russian speakers and the degree of Russification of the titular group members also influences the language policy of a state7. The language policies of those states, where the degree of Russification among titular population, as well as the share of Russian speakers (Russians) were higher, the decision to grant an exclusive “state” status to the titular languages aimed, inter alia, at supporting and

5 Laura Adams ‘Can We Apply Postcolonial Theory to Central Eurasia?’[2008]Central Eurasian Studies Review, 7(1); Anatoliy

Remnev, ‘Kolonialnost’, kolonialnost’ i ‘ostpricheskaya politika’ v sovremennom Kazakhstane, (Colonialism, post-colonialism and ‘politics of history’ in contemporary Kazakhstan ) [2011] Ab Imperio, 1; Karlis Recevkis, ‘Towards a postcolonial perspective on the Baltic states’ [2002] Journal of Baltic studies, 33/1

6 Aneta Pavlenko, ‘Russian as a lingua franca’, (2006) Annual Review of Applied linguistics,vol.26 7

reinforcing the indigenous languages weakened and declined over the history of Russian (language) domination in the area8.

The language policies of Latvia and Estonia where the share of Russian-speaking communit y constitutes 42.5 and 35% respectively, undergone perhaps the strictest de-russification policy9. The titular languages were assigned the exclusive official status and dominated the public realm of the states. One of the most contested component of the policy is the titular language proficiency test set as a requirement for naturalization, excluding the great part of Russians from the effective citizenship10.

The linguistic situation in Ukraine prior to the conflict in 2014 had a lot in common with other post-soviet states: sizeable Russian community, highly Russified titular population as well as the weaker communicative power of Ukrainian as compared to Russian that dominated media, government as well as everyday interactions. In the aftermath of conflict, the issues of language and more generally inter-ethnic as well intrastate relations with Russia, deteriorated dramatically and still today continue posing a threat to the political stability of the country. Language issue alone hardly was a key or even major factor for the emergence of conflict, such aspects as the geopolitical interests, territorial claims in the general context of a divided society have to be taken into account in assessing the nature of conflict’s inception. Nevertheless, language had certainly been used as an instrument of conflict exacerbation11.

Despite having an official status, the use and development of the Russian language in Ukraine was, however, guaranteed by the language law adopted in 1989. In fact, with regional variatio ns and differing level of intensity, Russian was widely spread in the key public domains such as government, media, and education. The much contested language law of 2012 has proposed the ‘officialization’ of Russian language status in the regions, where the share of minority group

8

With the exception of Belarus, where both languages were granted an official status. Nelly Bekus, “Hybrid” Linguistic Identity of Post-Soviet Belarus, Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe, Vol 13, No 4, 2014

9Pavlenko(n6) P.89

10For more information about the Latvia and Estonian language policies see: Aija Priedīte (2005) Surveying Language Attitudes

and Practices in Latvia, Journal of M ultilingual and M ulticultural Development, 26:5, p.412; Aadne Aasland (1994) The Russian population in Latvia: An integrated minority?, Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics, 10:2,p.235; Olga Pisarenko (2006) The acculturation modes of Russian speaking adolescents in Latvia: Perceived discrimination and knowledge of the Latvian language, Europe-Asia Studies,58:5, p.756; Delaney M ichael Skerrett (2011) Languages and lives througha critical eye: the case of Estonia, Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 8:3,p.240

11Christian M arxsen ,The Crimea Crisis:An International Law Perspective, Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und

exceeds 10% of the total population12. Additionally, the law enabled the official use of other minority languages such as Hungarian, Bulgarian, etc.

Opponents of the ‘officialization’ of minority languages in the regions expressed their concern for further worsening of Ukrainian language’s situation. Similar concern was articulated in the report prepared by the Venice commission of CoE, which was asked to evaluate the draft of the law and gave an overall positive assessment13.

The disapproval of Russian language’s de-jure officialization by many politicians, intellect ua ls as well as ordinary Ukrainians is very illustrative of the importance that ethnic Ukrainians attach to the symbolic superiority of Ukrainian language over Russian. Thus, reminding that the need for a balance in language policy in post-soviet states is dictated not only by the possible resistance on the side of sizeable Russian-speaking community, but also by growing demands of nationalist- minded members of the titular groups.

The curtailed accession to the EU and subsequent protests of Maidan have sharpened the societal cleavage, where the linguistic divisions coincided with the conflicting views on state’s future development: the rapprochement with west as opposed to retaining close ties with Russia (the west being pro-Ukrainian and pro-West, and the east being pro-Russian and pro-Russia)14. Eventually, the vulnerable language issue has been brought to the forefront of political struggles, as the post-maidan self-appointed government in Ukraine intended to cancel the language law of 2012, resulting in mass unrest among country’s Russian-speaking population.

This conflict opened a forum for debates in the academia around the issue of the (il) legality of Crimean secession and Russian intervention, and the possible response from the internatio na l community. The opinions over the classification of actions split clearly into two categories. The western academia and media characterize Russia’s actions as a de-facto annexation of Ukrainia n lands. On the other hand, Russian commentators consider the events under the umbrella of the

12http://zakon3.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/5029-17

13Opinion on the Draft Law on Principles of the state language policy of Ukraine №651/2011 , adopted by the Venice

Commission at its 89th Plenary Session, December 2011

14 Roy Allison, Russia’s ‘deniable’ intervention in Ukraine: How and why Russia broke the rules, International affairs 90: 6

principle of ‘self-determination of peoples’, thus justifying the intervention upon invitation and the responsibility to protect 15.

Furthermore, Crimeas secession and subsequent separatist activities in eastern Ukraine gave rise to the discussions of a potential for the same scenario’s repetition in northern and northeast Kazakhstan. Soon after Crimea seceded, a politician, famous for his controversial and provocative speeches, Vladimir Zhirinovskiy and more recently the deputy of State Duma Pavel Shperov made related statements about the need to return ‘historic Russian lands in Kazakhstan’16. Whereas somewhat fierce verbal battles that broke out on social networks and the internet in general, can be disregarded as irrelevant to the official politics and rhetoric of states, on the contrary, the statements put forward in the circle of the Russian politica l establishment legitimately raises concern17.

Kazakhstan is also one of the most Russified country of the post-soviet camp and was the only state where the titular ethnic group was a minority at the time of the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Despite the fact that Russian language enjoys de-jure and de-facto official status and continues to be used as a language of wider communication (predominantly in urban areas) the language policy of Kazakhstan often tends to be characterized as discriminatory in the eyes of country’s Russian speakers, who aspire to the ‘co-state’ status of their language. In academia, state language policy tends to be portrayed dissonantly, from discriminatory and ethnocentr ic18 to the most liberal in the post-soviet space19.

15

Burke-White, William W., "Crimea and the International Legal Order" (2014). Faculty Scholarship. Paper 1360; Simone F. van den Driest, Crimea’s Separation from Ukraine: An Analysis of the Right to Self-Determination and (Remedial) Secession in International Law, Neth Int Law Rev (2015) 62:329–363; Anatoly Kapustin,Crimea’s Self-Determination in the Light of Contemporary International Law, Zeitschrift für ausländisches öffentliches Recht und Völkerrecht (ZaöRV), 75 (2015), 101-118

16 Emil Khazin, ‘Russian State Duma claims the territory of Kazakhstan’ (Exclusive.kz, 2017)

http://exclusive.kz/deputat_gosdumy_pretenduet_na_territoriyu_kazakhstana, see also Ilya Azar, ‘Ust-Kamenogorsk People's

Republic: Are Kazakhstani Russians waiting for "polite people", Ilya Azar's reportage (M eduza 2014)

https://meduza.io/news/2014/10/20/ust-kamenogorskaya-narodnaya-respublika

17

The issue of (il) legality of any claims of Russian community northern and north eastern Kazakhstan as indigenous peoples, and therefore their (or Russia’s) territorial claims over those regions, despite being fundamental to the understanding of Russian community’s dissatisfaction with their status within the hierarchy established by the new regime, are nevertheless beyond the purposes of this thesis. See: Viatcheslav M orozov, Kazakhstan and the “Russian World”: Is a new intervention on the horizon?, PONARS Eurasia Policy M emo No. 364 June 2015

18 Erlan Karin, Andrei Chebotarev, ‘The Policy of Kazakhisation in State and Government Institutions in Kazakhstan’, in

Nurbulat M asanov, Erlan Karin, Andrei Chebotarev and Natsuko Oka, The Nationalities Question in Post -Soviet Kazakhstan (Jetro,2002)

19 Pal Kolstoe, Russians in the Former Soviet Republics (London, Hurst 1995); William Fierman ‘V Kazakhstane umerennaya

yazykovaya politika (The Language policy in Kazakhstan is moderate)’, from his interview to online news portal < https://goo.gl/2L6Drh>

Since gaining the independence, the language issue in Kazakhstan has become highly politicized, primarily because of the 'status reversal' of languages, which implied the shift in symbolic power of one language over another and more broadly, of one ethnic group over another20. Kazakhstan, as other post-soviet states, had to face numerous challenges the most acute of which was the nation building. On the one hand, the newly independent state sought for ways to establish itself as a nation-state, reasserting its culture and language (Kazakh culture and language), that had experienced a considerable decline over the period of Russian domination. To this end, measures including the elevation of the status of Kazakh language to a ‘sole state language’, a gradual transformation of linguistic landscape favor of Kazakh and state sponsored influx of repatriates from Mongolia, China, Russia, etc. were undertaken by the Kazakh government. These and other similar practices are commonly referred to as ‘kazakhisation’ in academia and social commentary21.

On the other hand, Kazakhstan inherited very diverse multiethnic and multilingual population and the requisite for maintaining the loyalty ethnic groups and good relations with Russia. These factors have pushed the government to pursue a civic nation-building, granting wide range of positive rights and liberties to all ethnic groups22. The language policy also has a dualist ic nature, as state is conducting the policy of the Kazakh language monolingualism (exclusive status of state language and de-facto kazakhistaion) and a policy of pluralism of langua ges (official recognition of Russian and languages of other ethnic groups) simultaneous ly. Therefore, to some extent the polarity of the opinions about the nature of Kazakhstani language policy and planning can be explained by the dualistic nature of nation-building practices and language policy design.

Considering that the main justification for Russia’s intervention in Crimea mentioned on the official levels (in public statements, academic papers) was the (alleged) linguistic discriminat io n

20 Juldyz Smagulova , ‘Language Policies of Kazakhization and Their Influence on Language Attitudes and Use’ [2008]

International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 11:3-4, 440-475

21Donnacha O’ Beachain and Rob Kevlihan, ‘State-building, Identity and Nationalism in Kazakhstan: Some Preliminary

Thoughts’ [2011] Working Papers in International Studies, №1

22Juldyz Smagulova, ‘Kazakhstan’ [2006] Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 19:3-4, 303-320; see

also Natsuko Oka, ‘Nationalising Policies in Post-Soviet Kazakhstan’, in Nurbulat M asanov, Erlan Karin, et al, The Nationalities Question in Post-Soviet Kazakhstan (Jetro,2002)

of Russian community, there appears to be a strong case for greater consideration language related controversies in Kazakhstan.

The question is how these conflicting views as to what constitutes fairness /discrimination, in the management of language issue can be reconciled. If a language (or linguistic group) had experienced an explicit or implicit colonial oppression or otherwise a cultural and linguis t ic dominance of another language (group), does this fact legitimizes or necessitates ‘restorative/reparative’ language policies, with the ultimate aim of strengthening the previously oppressed languages and making them dominant again?

Structure of the thesis

Chapter I provides a theoretical foundation of remedial language policies, drawing on the literature on the situation of Baltic States, and to a certain extent by referring to the case of Catalan and other endangered languages.

Before turning to the remedial language policies, the chapter will extensively discuss the theoretical considerations of the main debates around the issue of linguistic diversity, such as whether it should be preserved or not; should the response be positive, then how linguis t ic diversity should be protected?; should the rights-based approach apply?; then who should be accorded the rights, individual, groups or languages themselves?; should all the langua ges (linguistic groups) receive protection or only some of them?; if only some of them, then how these (languages) groups should be differentiated?; and finally, what is the relation between colonialism, power and language? How the post-colonial state’s linguistic situations are different from those of other countries? Can the injustices and oppression experienced by linguistic group (or generally language) justify deliberately altering the inequalities and inadequacies with regard to languages?

At the core of the remedial language policy and linguistic decolonization theories is the concept of indigenous languages decline and loss resulting from continuous imposed contact with dominant languages. Therefore a detailed account of the theories of language decline and loss (language shift), as well as the impact of language policies (or their absence) on facilitation of these processes will be provided in the first chapter. Furthermore, the role of language planning in reversing the actual settings as well as different types of ideologies and approaches

underpinning the planning and policy choices will be discussed. As will be seen from the findings of the chapter, linguistic diversity management is a highly complex issue riddled with contradictions, which makes a uniform global solution to all language issue implausible. The solutions to the language complexities of each state have to be planned and tailored based on their specific case, combining both historical-structural approaches and rationality principles.

Building on the language shift framework elaborated in the first chapter, Chapter II will

provide a detailed account of the history of language shift in Kazakhstan. The different historica l periods are closely examined with the aim of tracing the changes and shift in the socio-economic and political environment as well as the impact it had on the Kazakh language. Through the theoretical lens of Mühlhäuser’s concept of language’s habitat, it will be argued that the first irreversible damage to the Kazakh language vitality had been made during the tsarist regime, by superseding and subsequently supplanting the traditional judicial system of Kazakh people (‘biys’ institute) with the imperial one. Furthermore, in connection with the theories of remedial language policies and linguistic decolonization, the controversial issue of applicability of post-colonialism theories in Kazakhstan’s case will be discussed. The underlying aim of the chapter is to provide a moderate assessment of complex, ambiguous and cyclical nature of imperial and soviet past of Kazakhstan that acknowledges some of the objective factors in the dynamics and developments of colonizer/ colonized nexus, thus helping to reduce the post-colonial antagonism. An overview of nation-building practices will be given in the last subchapter, revealing the rootedness of dualistic nature of language policy in similarly configured wider process of national identity construction.

Chapter III will examine the language related legislation and official policy documents. The

main principles that shaped the language policy and some of the constraints hampering its effective implementation will be investigated.

To sum up, this thesis will argue that the distinctiveness of Kazakhstan’s (and more broadly post-soviet) linguistic situation does necessitate a special, tailored planning and policy, that would take into account the power relations of Kazakh and Russian and therefore provide preferential conditions to the Kazakh language, at least temporarily. At the same time, in light of the recent unfortunate events happened in Ukraine, that vividly illustrated the consequences of disregarding and underestimating the potential explosiveness of the linguistic issue, this paper

will argue that in the interest of inter-ethnic stability and social cohesion in Kazakhstani society as well as the ‘genuine promotion’ of Kazakh language it is desirable to frame the policy within cultural heritage model as opposed to the nationalizing framework, and pursue the promotion of Kazakh with the ultimate aim of establishing the regime of (substantive) equality.

Chapter I. Challenges and constraints in language policy and planning in Kazakhstan

1. Language loss and shift: Why do languages decline?

According to different estimations, there are approximately 5,000–6,000 languages and their varieties in the world. Around 100 languages are spoken by 95% of the world’s total population, while the rest thousands of languages are used by remaining 5%. Many scholars predict the eradication of at least half of the languages of the world in the course of the 21st century23. One of the major reasons for language’s disappearance lies in the decision of its speakers to stop using it. They choose to do so in the adaptation to the new circumstances where the use of their mother tongue is no longer advantageous to them. While this issue about language death is simple and therefore undisputable, the issue about the causes that lead to the decrease of language’s efficacy in a community is far more intricate and ambiguous.24

The demise of languages is the product of a compound mechanism. History provides various examples where languages vanish due to the physical elimination of the entire population of its speakers (as in Uruguay with Charrua language), as well as part of it (as happened in Brazil, Chile and Argentina). Such practices are often referred to as “linguistic genocide” in the language related literature25. Day defines ‘linguistic genocide’ as a type of language death, which typically follows a continuous cultural contact of societies, unequal in terms of economic and military power.26 He argues that the policies and practices on a governmental level, as well as in the area of education, religion, and trade are the primary causes of languages’ shift.

23 Krauss M ichael, ‘The world’s languages in crisis’ [1992] Language, vol. 68/1, p.5-6; see also: D. Nettle and S. Romaine,

Vanishing Voices: The Extinction of the World's Languages (OUP 2000)

24

Lionel Wee, Language without Rights (OUP,2011)

25Ibid 26

Richard Day, ‘The Ultimate Inequality: Linguistic Genocide’ in Wolfson, Nessa/M anes, Joan, (eds), Language of Inequality (De Gruyter 1985) It is noteworthy, that the notion of ‘cultural genocide’ (which also implies a ‘linguistic genocide’) was discussed as a serious crime against humanity along with physical genocide of peoples at the preparatory phases of convention and was included into the draft convention’s Article 3: “Any deliberate act committed with intent to destroy the language, religion or culture of a national, racial or religious group on grounds of national or racial origin or religious belief, such as (1) Prohibiting the use of the language of the group in daily intercourse or in schools, or the printing and circulation of publications in the language of the group; and (2) Destroying or preventing the use of libraries, museums, schools, historical monuments, places of worship or other cultural institutions and objects of the group”, however, the final version of convention did not cover linguistic and cultural genocide because sixteen member states voted against it, preferring the Convent ion to be limited only to the physical elimination of human groups., http://www.encyclopedia.com/international/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/linguistic-genocide , accessed on 02/05/2017

If earlier the prohibition on the use of one’s mother would be direct, through such means as physical punishment of indigenous peoples for using their language (practicing culture and religion), later such measures yielded to a more subtle and indirect ones, such as encourageme nt and rewarding in different ways of those who choose to shift27. Thus, even without open measures against indigenous languages and their speakers, the language shift can be generated by the creating conditions for it, through positive support of dominant language as well as systematic limitation of local languages’ functional domains28.

The linguistic and cultural contacts were normally occurring in the context of boundaries’ shift resulting from, inter alia invasions, imperialistic expansions, and so on. Classical expansionist and the internal colonialism have produced a language hierarchy in the colonized speech communities, where the language of colonial power was assigned prestigious status and dominant position in administrative and economic structures. The fact that proficiency in the dominant language fosters the upward social and economic mobility demonstrates that the significance of languages goes beyond of mere cultural and symbolic value. In this regard, Bourdieu links the notions of language and power, underlying the importance of the former as a non-economic capital and power that a dominant group exerts over others. The knowledge of dominant languages provides the access to education, political systems and better opportunities29.

The upper social strata of colonized population tend to be first to abandon their mother tongue, which begins to be associated with backwardness, domestic and more generally, rural life. With the spread of literacy, people increasingly chose to educate their kids in the dominant language, which results in slowing down if not haltering of the functional development of local langua ges. Initially painful decision of parents to educate their kids in the majority language provide them with better opportunities, best exemplifies how economic and social factors alone, without clear assimilationist policies, can greatly facilitate a gradual language shift.

27 Tove Skutnabb-Kangas and Robert Phillipson (eds) (2017). Language Rights. London/NewYork. Series Critical Concepts

in Language Studies. 4 volumes. In Volume 1; Richard R. Day, The Ultimate Inequality: Linguistic Genocide, in Nessa Wolfson, Joan M anes (eds), Language of inequality (De Gruyter, 1985)

28 Wee (n24)

29 Pierre Bourdieu, Language and Symbolic Power (Cambridge, Harvard UP, 1977), 502-3., in Piage Brewer, ‘The mankurt

Not necessarily, the language shift results in speaker’s loss of native language, in some cases they become bilingual, i.e. maintaining the knowledge of two languages at the same time. The languages tend to play dissimilar roles in bilingual speaker’s life, mirroring the power structure he associates with each language. One language is spoken within family and friends, while the other one is used at school and work30.

The condition when two languages co-exist on the same territorial unit, occupying differe nt functional domains is termed in sociolinguistics as diglossia.31 The term was first coined by Ferguson to describe a specific type of societal bilingualism where high and low varieties of the same language coexist within the same unit. Later Fishman has expanded the application of the term to the cases where two different languages function in the same society32.

When languages function and coexist side by side on the same territory, they come into contact and sometimes conflict with each other. Some of the consequences of languages’ contact include the change of languages, through the borrowing (often mutual) of words and language structures, the extreme language mixture (creoles, bilingual mixed languages) and language shift33. The contact situations can be stable and unstable. The former one occurs where the widespread societal bilingualism is complemented with a stable diglossia, which implies the separated use of languages in different domains. Fishman provides an example of Paraguay, where population is bilingual in Spanish and Guarani, serving separate designated functions34. On the contrary, many scholars characterize the contact situation where bilingualism occurs without diglossia as transitory or unstable35. Individuals are free to decide on which of the two languages to use in what domains and settings. As Fishman maintains, without the division of the functions of languages, the one associated with social and economic benefits tends to

30 Piage Brewer, ‘The mankurt remembers : the politics of language in Kazakhstan’ [2015] College of Arts & Sciences Senior

Honors Theses. Paper 41, p.5

31

Charles Ferguson, ‘Diglossia’, in Pier Paolo Giglioli (eds) Language and Social Context, (Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books, 1972) 232-251; Fishman, Joshua “Bilingualism with and without Diglossia; Diglossia with and without Bilingualism”[1967] Journal of Social Issues, 32

32

Joshua Fishman, The sociology of language: An interdisciplinary social science approach to language in society (Rowley, M A: Newbury House, 1972)

33Sarah G. Thomason, Language contact (Edinburgh University Press,2001), p.10

34Joshua Fishman, ‘Bilingualism with and without diglossia; Diglossia With and Without Bilingualism’ [1967] Journal of

Social Issues, p.31

35 Joshua Fishman, The sociology of language: An interdisciplinary social science approach to language in society (Rowley,

supplant the other one36. The example of Brussels is very illustrative of language shift resulting from unregulated bilingualism. What was initially predominantly Dutch populated city, turned to be a chiefly francophone one over a century of close contact of two languages in the same city37. Some of the reasons of Brussel’s ‘Frenchification’ included the prolonged exclusive official status of French across the country in the past and high international prestige of French as opposed to a lower one of local variety of Dutch spoken by inhabitants of the city38. Another way in which the language shift can be triggered is through the destruction of language’s habitat. Mühlhäuser argues that “each language needs for its sustained well-being a complex ecological support system which includes factors, such as other languages from which they can borrow, internal dialect variation, territory, language-centered cultural practices, natural boundaries, the optimum size of a population of speakers, and many more”39.

The language’s demise is a gradual process, which is typically divided into three stages. The first step is characterized by a growing pressure on the minority group to give up their language in favor of a majority one, mostly in official public domains. This, in turn, necessitates the study of a majority language at school, or even its use as a medium of instruction at the educational institutions. Overall, this tendency results in a decrease of minority language’s functio na l domains. Bilingualism, normally an asymmetrical one, occurs during the second stage of the shift. While both languages continue to operate concurrently, the number of speakers of a weaker language, above all among younger generations, decreases. The final third stage ensues over time, with the change of several generations, and can be characterized by almost complete replacement of a minority language with the majority one. The older population can still use the language; however, it is no longer a medium of wider communication40.

To sum up, the consideration of the theory of language decline and loss appears to be important for any language policy and minority language rights debates in number of ways. First, it reveals

36Toleffson (n35), p.6

37Helder De Schutter, Testing for linguistic injustice: territoriality and pluralism, Nationalities Papers, 42:6, 2014, p.1038 38For more information on language shift in Brussels, see: Jeanine Treffers-Daller, ‘Language Use and Language contact in

Brussels’[2010] Journal of multilingual and Mulricultural Development, p. 50

39

Peter M ühlhäuser, ‘Linguistic ecology: Language change and linguistic imperialism in the Pacific region’, Routledge, 2002, p.276

40 Ferguson, Charles “Diglossia”, in Language and Social Context, ed. Pier Paolo Giglioli, 232-251. Harmondsworth,

England: Penguin Books, 1972; Fishman, Joshua “Bilingualism with and without Diglossia; Diglossia with and without Bilingualism”, Journal of Social Issues, 32 (1967)

that languages ‘death’ does not always occur ‘naturally’, but is rather preconditioned by several factors such as discrimination, unequal competition, subordination. The so-called ‘market forces’, i.e. political, economic and social factors seem to hold primary responsibility for the linguistic assimilation of minorities within the state41. Secondly, this knowledge demonstrates that languages, unequal in terms of power, prestige and development, cannot ‘equally’ coexist with stronger dominant language. Special measures on behalf of the states are needed to ensure the maintenance of languages. The models of linguistic coexistence, as well as the main debates around this issue will be discussed in details in the following sub-chapters.

1.1. Linguistic homogeneity vs. linguistic diversity

The present political organization of the world centered on the ‘nation-state model’ is contributing to the process of languages decline and loss across the globe on an unprecedented scale. Nation-state model is seen as the final point of modernity and progress, the triumph of universalism over particularism. The ‘triumph of universalism’ with regard to languages meant the replacement of different vernaculars with a standardized national one. This replacement process consists of the legitimation, i.e. the official recognition granted to the language, normally by means of constitutional and legislative acts; and the institutionalization, which presupposes the widespread incorporation of a selected language into all public and private social, cultural and linguistic domains42.

In advocating the cultural and linguistic homogenization, the proponents of nation-state model draw on the ideals of equality of opportunities and common citizenship. Standardized public education through the medium of one national language secures equal opportunity in higher education, employment and in interaction with official bodies for the whole population regardless of class, religious, racial affiliation, and so on43.

One of the common justifications advanced in favor of linguistic unification is the cohesion of society in the interest of common good44. A shared language foster the generation of common

41 M ichael Hornsby, Language endangerment, in in Wójtowicz, R., Linda, K., Nau, N., Wicherkiewicz, T., Hornsby, M .,

Duray, Z., Trilsbeek, P., Jung, D. 2012. INNET Awareness report. Retrieved from http://innet-project.eu/sites/default/files/D4.1_Awareness.pdf

42 Stephen M ay, Language and Minority Rights. Ethnicity, Nationalism and Politics of Language (Routledge 2012) p.5 43 Idil Boran, The ethics and politics of linguistic coexistence, p.2

44

sense of belonging and loyalty among the population. The major concern with the linguis t ic diversity is that it causes the division of people into distinct collectivities and impedes them from sharing the effective bond of common citizenship.45

The second argument supporting state’s monolingualism is the one of efficiency. Many scholars concur that according all the existing languages within the state with equal status (which presupposes equal representation and support within the public realm, education, media, government administration and documentation) is cost-inefficient and complicated, thus is simply non-practical46.

Another argument in favor of linguistic homogeneity of societies centers on the capability of a common language to foster the deliberative democracy. “Democratic decision-making is not just a formal process of voting on the basis of antecedently given preferences. It also presupposes an ongoing activity of deliberation and discussion, mainly taking place in civil society, in which free and equal citizens exchange reasons and are sometimes moved by them to change their opinions and preferences”47.

1.2.The nation-state and (linguistic) minorities: Sovereignty, territorial integrity and self-determination

The problem with these settings is that except for a few, the majority of states in the world are not ‘nations’, but multinational states, consisting of several national and ethnic groups. Thus the widespread use of the terms nation and state in an interchangeable manner, in fact, proves to be controversial and non-realistic. Most scholars agree that only few (if any) states, such as Iceland and Japan can claim to encompass one nation or people within its borders.48 Typically, there is

45

Will Kymlicka and Alan Patten, Language Rights and Political Theory (OUP, 2003)

46

Valentin Avrorin, Problem izuchenia funkcionalnoi storony yazika (The study of the functional aspect of language) (Leningrad: Nauka 1975) p.205; see also Desheriev Yunus, ‘Socialnaya lingvistika. K osnovam obshei teorii (Sociolinguistics ) (M .: Nauka 1977), p.259, cited in Pool (n81) p.496; see: Francois Grin, ‘Linguistic Human Rights as a source of policy guidelines: A critical assessment’ [2005], Journal of sociolinguistics 9(3), p.450

47 Patten, Kymlicka (n45)

48 However, this is also subject for debate as there is Ainu minority inhabiting the Hokkaido island, as well as the north of

Honshu, Japan's main island and Sakhalin island, in Russia, indigenous group, the total population of which comprise approximately 30,000 and 50,000. Only a very small number remain fluent in their traditional language; see Alpatov As regards Iceland, as Hobsbawm argued, the linguistic uniformity was made possible through a ruthless policy of

Icelandization, including forcing every immigrant to take an ancient Icelandic name; see: Eric Hobsbawm, ‘Language, culture and national identity’ [1996] Social research, vol.63,p.1068

several peoples coexisting side by side, and the membership of some of them within the state population is often involuntary.

The recent history of humankind has witnessed the attempts of groups across the world to invoke the ‘right to self-determination’ in pursuit of wider autonomy within the states they belong to or, alternatively, a complete separation from it. Carley points out that the proliferation of such movements is closely related to the strengthening and universal application of western ideas, such as democracy, equality, and human rights.

The right of peoples to self-determination is enunciated in such international instruments as International Covenants49, UN Charter50 as well as the Helsinki final act51. Article 1, para.1 of ICCPR stipulates that:

‘All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultura l development’52

The UN Charter provisions emphasize that the development of friendly relations among nations has to be based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples53. This principle is reiterated in the part VIII on Equal rights and self-determination of peoples of the Helsinki Final Act, which provides that:

‘The participating States reaffirm the universal significance of respect for and effective exercise of equal rights and self-determination of peoples for the development of friendly relations among themselves as among all States’54

There are competing interpretations of the right to self-determination in the academia. As Currie argues, the difference is rather in the emphasis, than in the proper content of the right. According to her two types of interpretations of the right can be distinguished: the external and internal

49 The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights was adopted by General Assembly resolution 2200 A(XXI) of 16

December 1966, and entered into force 23 M arch, 1876

50

The UN Charter was signed at San Francisco on 26 June 1945, it is the constituent treaty of the United nations.

51

The Final act of the Conference on Security and co-operation in Europe, adopted in Helsinki, 1975

52 ICCPR (n49)Aticle 1, para.1 53 UN Charter (n50) Art.1, para.2 54

self-determination. The former one refers to the instances where peoples, with some degree of national consciousness, claim self-governing and the formation of their own state, typically through decolonization and more controversially, through secession. The second understanding of the right refers to an internal dimension and regards the rearrangement of the relations hip between people in question and the state where they live55.

However, in the absence of a precise definition of the right, as well as the indications about what precisely the right entails (wider autonomy or separate statehood) its application proves to be troubling in practice.

Another perplexity related to the notion is connected with the beneficiaries of the right, for it is nowhere clearly stipulated to whom the right is conferred. Whether it is reserved exclusive ly for indigenous peoples, or it can also be claimed by the longstanding ethnic groups as well as by any distinct ethno-cultural group, including immigrants56.

The claims of minorities for an accommodation of their language rights, which may imply a wider autonomy are fiercely resisted by the nation-state system, because of the possibility of its transformation into a claim for independent statehood. That is why the international communit y of states, who are the subjects of international law as well as its architects, does not support or approve the attempts of boundaries’ change from the inside (as well as outside).

As was mentioned previously, most of the political conflicts and challenges across the globe were/are centered on the issue of linguistic diversity. As Patten and Kymlicka suggest, the main complexity here is that the debates over the languages are hardly only about the langua ges themselves. For all the parts of the world, both west and east the linguistic groups usually constitute a ‘national group’, as they see themselves not only as speakers of a distinct language but also as a distinct ‘nation’ within a larger state. In this view, language rights constitute a ‘part of a larger program of sub-state nationalism’57.

55

Iaine Currie, ‘M inority Rights: Education, Culture and Language’ in M atthew Chaskalson et al. (eds), Constituional law of South Africa (Kenwyn: Juta1996)

56 Avishai M argalit and Joseph Raz, ‘National self-determination’ [1990] The journal of Philosophy, pp. 439-461 57

The reluctance of the UN member states to support such boundary shifts can be explained by their fear of the consequences, such kind of practice may cause for themselves since literally, every country in the world is a bearer of a certain type of diversity.58

Whether the minority group succeeds or not in its aspirations, it sends a powerful message to the other groups elsewhere, thus creating a precedent. This encourages minority groups in other parts of the world to claim their right to self-determination. The term “demonstration effect” was coined by Connor to describe kind of phenomenon59.

Because the right of peoples to self-determination is so threatening to the integrity of states, the international provisions on the right are vaguely drafted, and the rights, though recognized under the UN charter, has many difficulties in being exercised in practice.60

In this regards, a question arises as to what should be the (or should there be at all) limits to the self-determination of peoples? Where the borderline between the appeal for self-determinat io n and the one for separate statehood lies?

There is a consensus, among scholars about the need of distinguishing and separating the right to self-determination with the one of secession, as the latter one is not recognized by international law61.

According to the United Nations General Assembly resolution, the state where the entire population is governed in conformity with the principles of equality, non-discrimination and self-determination is entitled to maintain its territorial integrity under international law and to have this right respected by the international community of states:

“the right of self-determination ‘shall not be construed as authorizing or encouraging any action that would dismember or impair, totally or in part, the territorial integrity or political unity of sovereign and independent states conducting themselves in compliance with the principles of equal rights and self-determinat io n

58

Ronald Wardlaugh, Languages in competition (Basil Blackwell 1987) p.22

59

Ibid p. 22

60 Ibid p.29

61 Patricia Carley, ‘Self-determination: Sovereignty, territorial Integrity, and the Right to Secession’, [1996] Report from a

of peoples and thus possessed of a Government representing the whole people belonging to the territory without a distinction of any kind”62

Green argues that appeal to secession or independence has to be supported by a powerful argument. According to her the failure of the present regime, existing arrangements or so-called ‘a scheme of cooperation’ to guarantee fair (just) treatment, may serve as the basis for minority groups’ appeals for wider autonomy, or eventually secession and independence.

Green further adds that the minority’s case for independence will be considerably weakened if, for instance, the language rights regime of the state complies with the demands of justice63. Here it is important to note that, while language rights are the major part of minorities’ claims, however dimensions like political participation, religion, etc., also have to be considered in those settings.

According to Carey, instead, the secession or the appeal for independence can be regarded as a legitimate purpose of some self-determination movements only, in particular where it is invoked in response to gross and systematic violations of group’s members’’ human rights.64 In conclusion, it can be said that in the clash of conflicting and competing principles of states’ sovereignty as well as peoples’ right to self-determination, the former one triumphs unequivocally. Despite the multi- national, ethnic and lingual character of most of the states as discussed above, the notions of nation and that of state continue to be equated, and the model to be desired by most of the states.

In the course of nation building process, state authorities aim at providing their peoples with the common sense of belonging to legitimize their authority over them. According to Skutnabb Kangass, language plays a crucial role in any nation-building project as a major ‘homogenizing’ tool. This ‘homogenization’ is typically achieved using nationwide education through majority language medium, resulting in gradual eradication, and eventually, in loss of minority langua ges present in the state65.

62

UNGA Declaration on the occasion of the 50th Anniversary of the UNGA Res. 50/6 (1995)

63

Lesley Green ‘Are language rights are fundamental?’ [1987] Osgoode Hall Law School of York University

64 Carley (n61)

65 Tove Skutnab-Kangass ‘Language and self-determination’ in Clark Donald and Williamson Robert (eds)

Simultaneously, language serves as the tool in ‘counter-hegemony’ struggles, and in the self-determination claims on a psychological, educational and political level.66 Skutnabb-Kangass emphasizes that language is connected with the notion of self-determination in many differe nt ways. As the main tool for exerting power and control, language plays a crucial role both in ‘colonizing the consciousness of peoples to maintain oppressive societal structures and in decolonizing the mind to counteract these oppressive structures’67.

2. Linguistic diversity accommodation: why care?

In view of the advantages, that linguistic homogeneity can bring about the need for the protection of declining linguistic diversity is highly contested. It is a matter of discussions whether the threatened languages should be supported and maintained at all. Why not just letting them to exist and compete, accepting the possibility of language extinction? There are differe nt perceptions about the role of languages in human’s life. Language can be seen as constitue nt part of our identity, an integral element of cultural heritage and as an instrument of communication. The two former understandings of language necessitate certain linguis t ic policies for its preservation, whereas the latter view of language sustains that the governme nts should refrain from intervening, allowing market forces to decide which languages will survive and not.68

2.1.Language and identity link

One fundamental argument advanced as the justification for the protection of languages is related to their connection with individuals’ identity. It holds that language plays a major role in individual’s identity formation, therefore the provision of safe and supportive linguistic and cultural environment is necessary for the personal development of individuals. Normally, in the majority of states, such conditions are set only for the members of cultural or linguis t ic majorities69. Mancini and De Witte point out that, the “the use of a particular language not only

66

Ibid.

67 Ibid, p.124

68Josep Costa, ‘Catalan linguistic policy: liberal or illiberal?’ [2003] Nations and Nationalism 9 (3), 413–432, p.421 69

serves as a means of functional communication but also expresses that person’s cultural identity as well as the cultural heritage developed by all previous speakers of the language.”70

For Fishman language and ethno-cultural identity are related in three ways, namely: indexica lly, in a part-whole way and symbolically. The indexical link between the language of a group and its culture refers to its suitability in naming the artifacts and articulating the values as well as the world views of a particular cultural group. However, it is noteworthy that in the long term other languages can substitute the mother tongue in doing so.

The part-whole link has to do with the fact that cultures are articulated, conceptualized, and lived through language, and are expressed via songs, history, proverbs, myths, laws and customs, prayers, etc. In addition to that, language is an inalienable part of interpersona l relations and socialization.

Finally, the language symbolically represents its speakers, in the perception of both the group itself and the outsiders. In this way, language’s future is dependent on the fate of its speakers. As Fishman argues, the spread or decline of languages is not determined by their superiority or inferiority; rather there seems to be a correlation between the symbolic and communica t ive status of language and the social and political fortunes of the group who speak it.71

Notwithstanding the fact, that the notions of language, culture, and ethnicity are often conflated and even equated72, however, as O’Reilly argues that many collectivities despite sharing a common language may be culturally distinct. Latin American countries and the Spanish language, as well as Anglo-Saxon countries and the English language, can serve as an example73.

70Susanna M ancini and Bruno de Witte, ‘Language Rights as Cultural Rights: A European Perspective’ in Francesco Francioni

and M artin Scheinin (eds) Cultural Human Rights (Leiden and Boston: M artinus Nijhoff Publishers 2008) p.247

71 Joshua Fishman Reversing Language Shift: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of Assistance to Threatened Languages

(M ultilingual M atters 1991)

72

As Extra and Gorter put it: ‘No text on cultural policy leaves out the fundamental principle of respect for cultural diversity. Diversity of cultures by implication means diversity of languages. Whoever rejects a language, denies a culture and vice versa’, Extra G. and Gorter D, 2001, ‘Comparative perspectives on regional and Immigrant M inority languages in M ulticultural Europe’, in The Other Languages of Europe: Demographic, Sociolinguistic and Educational Perspectives, (eds) G.Extra and D.Gorter. Clevedon, England: M ultilingual matters

73 Camille C. O’Reilly, ‘When a Language is ‘Just symbolic’: Reconsidering the significance of Language to the Politics of

Identity’ in Gabrille Hogan Brun and Stefan Wolff (eds) Minority Languages in Europe: Frameworks, Status, Prospects (Palgrave M acmillan 2003), p.20

a) The centrality of language to ethnicity and culture

After the end of World War II, which gave rise to the waves of decolonization and nation-building processes, the attention of scholars was directed at the notions of ethnolinguis t ic identity. History has witnessed many instances of people across the globe, consolidating around the factors they believe united them. Mostly, such factors include language, religion, ethnic it y, race, class, gender, occupation, age and so on, can potentially be generated as a consolidat ing power in group’s mobilizations. Language often plays a central role in such aspirations of groups74.

The language we speak is not merely our essential instrument of communicating feelings and thoughts but is also the major marker of our individual and collective identity. In this view, language is seen as a vehicle that carries the culture, traditions, and history of a group. 75 It is believed that languages express the distinctiveness of people and bind them together, and therefore is central to the notions of ethnicity and ethnic identity. According to Fishman, the concept of ethnicity:

“… requires a central experimental concept or chord around which all others can be clustered. This central experience is here termed paternity, and deals with the recognition of putative biological origins, and therefore, hereditary or descent related ‘blood’, ‘bones’, ‘essence’, ‘mentality’, ‘genius’, ‘sensitivity’, ‘proclivity’, derived from the original putative ancestors of a collectivity and passed on from generation to generation in a bio-kinship sense. He admits that ‘bio-kinship’ may be real, mythical, or fictive but whatever it is. It is the key feature”. 76

In addition to that, De Vos emphasizes the importance of group’s perception of itself as a group. The group’s history is frequently mythologized and serves to prove (establish) generatio na l continuity. Shermerhorn defines the ethnic group in a similar way. According to him, an ethnic group is a category of a group of people who share real or perceived ancestry and common history as well as an emphasis on one or more symbolic elements that distinguish the group

74

See: Carley (n61), M argalit (56)

75 William Safran, ‘Political Science and Politics’ in Joshua Fishman and Ofelia Garcia (eds), Handbook of Language and

Ethnic Identity. Disciplinary and regional perspectives (OUP 2010), p.49

76

from all the others. Such elements comprise religion, language or dialect forms, tribalism, and so on. Defining ethnicity in this way presupposes its involuntary characteristic, which individuals cannot choose or change. The ethnonational aspirations of groups are usually backed-up by a “glorious past” of a group. Some scholars argue that such past is a creation of ideology, which probably has never existed.77

The alternative way of defining ethnicity is by the tendency of ethnic groups to keep the boundaries. The group’s characteristics or the memory they share about their ancestry in this case yield to the importance of group’s ability to distinguish itself from other groups through the creation of boundaries. Some authors maintain that those boundaries are mental rather than territorial, and are supported by the attribution to certain characteristics designating membership from inside and outside78.

Thus, the conception of ethnicity is composed of both objective and subjective elements. The former one includes language, religion, traditions, social organization and institutio na l arrangements, whereas the latter one comprises the feelings, self-perception of a group and its identity. 79

As Wardhaugh maintains, in the course of history groups may lose their ethnic identity or acquire it. Some ethnic groups were products of colonial policies, as Malays in Malaysia, Ibo in Nigeria, Kikuyu in Kenia, where a system of local administration was established with the purpose of categorizing and controlling people, eventually constructing a supralocal identity. 80 Generally, the long established and geographically concentrated ethnic groups receive more attention, than migrants do, for instance, as the latter lack any basis for raising territorial claims. Ethnic affiliation is only one of the available types of group affiliations; however, due to their special attachment to the land they inhabit, it is considered the most powerful one in conflic t ua l situations. 81

77

Ibid p.45

78

Eric Hobsbawm, ‘Language, Culture and national identity’ [1996] Social research 4 (63)

79 Safran (n75)

80 Wardhaugh (n58) p.47 81