Ph. D. Program in

Management and conservation issues in changing

landscapes

Thesis

Linking community engagement and

ecosystem services assessment as a tool for the

rural landscape management

An applicative case for the

Collemeluccio-Montedimezzo Alto Molise Biosphere Reserve

Angela Tavone

International Ph. D. program

MANAGEMENT AND CONSERVATION ISSUES

IN CHANGING LANDSCAPES

XXVI Cycle

Ph. D. Thesis

Scientific-Disciplinary Sectors AGR 05 – AGR 01

Linking community engagement and

ecosystem services assessment as a tool for the

rural landscape management

An applicative case for the

Collemeluccio-Montedimezzo Alto Molise Biosphere Reserve

Tutor:

Prof. Davide Marino

Ph. D. Coordinator: Prof. Gabriella Stefania Scippa Co-tutor:

Prof. Paolo Di Martino

Candidate: Angela Tavone Reg. Number: 143792

Picture on the cover: Tavone A. – “San Domenico church in Carovilli countryside” (2014)

7

Table of contents

INDEX OF TABLES ... 11

INDEX OF FIGURES ... 13

INTRODUCTION ... 17

1. THE LANDSCAPE MANAGEMENT ... 22

1.1Definitions and regulatory tools: an overview ... 22

1.2 The rural landscape in Italy: fragilities and potentialities ... 29

1.2.1 Why the rural landscape ... 29

1.2.2 A special issue: the historical and traditional rural landscapes ... 37

1.2.3 Fragilities and potentialities of rural landscape ... 43

1.3 Finding a balance: the key steps to improve the management of rural landscape ... 52

REFERENCES ... 58

2. PEOPLE AND (IN) LANDSCAPE ... 68

2.1 Community engagement: the primary tool for the landscape management . 68 2.1.1 Participation: features of stakeholders ... 69

2.1.2 Participation: features of the process ... 71

2.1.3 Recommendations from some researches: mapping the community values and integrating participation with quantitative analysis ... 73

2.1.4 Who is the stakeholder and what participation does it need? ... 75

2.2 Experiences from Europe ... 80

8

2.2.4 Methodologies in Netherlands: the Scales for Perception and Evaluation of

Landscape and the Agenda Landschap ... 98

2.2.5 HeriQ Project: the heritage interpretation in the landscape management ... 102

2.3 Experiences from Italy ... 105

2.3.1 Regional Landscape and Territorial Plan of Puglia: an integrative participatory process ... 108

2.3.2 Landscape Observatories ... 113

2.4 A glance to overseas: the community engagement in the rural landscape of Vermont ... 122

2.4.1 Some key topics from USA and Vermont ... 123

2.4.2 The PLACE Program ... 132

2.4.3 The ECOS Project ... 139

2.4.4 Council on the Future of Vermont ... 141

2.5 A synthesis: the worthiness of the community engagement beyond the heterogeneity of the cases ... 142

REFERENCES ... 150

WEB SITES CONSULTED ... 164

3. THE ECOSYSTEM SERVICES APPROACH FOR THE LANDSCAPE

MANAGEMENT ... 168

3.1 Studying and managing the landscape with the Ecosystem Services approach: an introduction ... 168

3.2 Ecosystem Services assessment framework: from global to local ... 172

9

3.2.2 A focus on bioeconomy and natural capital concepts... 180

3.2.3 Making Good Natura: a case study from Italy ... 191

3.3 Assessing cultural Ecosystem Services in the landscape: the role of perception ... 195

3.3.1 Critiques to the usual Ecosystem Services assessment methods ... 196

3.3.2 The assessment of landscape starts from the perception ... 199

3.3.3 Linking the perception with Ecosystem Services assessment of landscape ... 203

3.4 A "twofold approach” for the landscape management: from the lessons learned to a proposal ... 208

REFERENCES ... 214

WEB SITES CONSULTED ... 229

4. AN APPLICATIVE CASE IN THE BIOSPHERE RESERVE IN MOLISE REGION

(ITALY) ... 232

4.1 An introduction to the application of the twofold approach ... 232

4.2 Assessing and mapping ecosystem services perception to support participatory planning and conservation priorities at landscape scale: the case of Collemeluccio-Montedimezzo Alto Molise Man and Biosphere Reserve in Central Italy ... 240

4.2.1 Introduction ... 240

4.2.2 The study area ... 246

4.2.3 Materials and methods ... 250

4.2.4 Results ... 253

4.2.5 Discussion ... 260

4.2.6 Conclusion ... 264

10

WEB SITES CONSULTED ... 292

CONCLUSIONS ... 293

SPECIAL THANKS ... 297

11

Index of tables

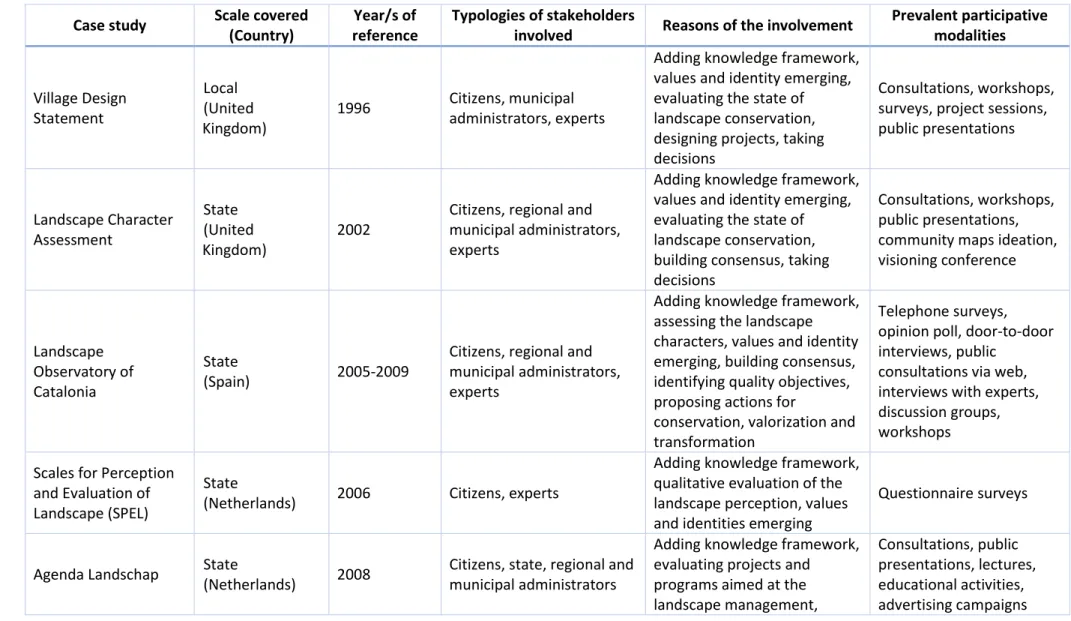

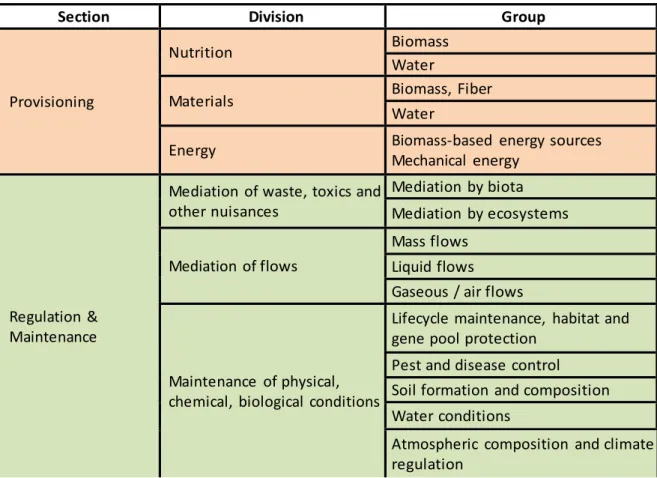

Table 1 - Fragilities and Potentialities of rural landscape: a synthetic scheme ... 45 Table 2. Typologies of participation: how people participate in development programs and projects (Pretty 1995). ... 77 Table 3 - A synthesis of case studies analyzed respect to the community engagement methodologies and the stakeholders involved. ... 146 Table 4: CICES V4.3 at the “three digit level”. ... 179 Table 5 – The main subjective and objective data investigated in the case studies here considered as good examples of landscape management. ... 208 Table 6 – Selection of ES from CICES classification (Haines-Young and Potschin 2013) made by the focus group. Per each ES class, a code has been attributed. ... 251 Table 7 – Corine Land Cover hierarchical classes and their covering on the BR landscape (%). ... 256 Table 8 – Relative abundance (%) of four ranges of ESP values per each CLC class in Section 1... 257 Table 9 – Relative abundance (%) of four ranges of ESP values per each CLC class in Section 2... 258 Table 10 – Relative abundance (%) of four ranges of ESP values per each CLC class in Section 3... 259 Table 11 - Correlations between the investigated CICES classes and the questions used during the interviews. ... 269 Table 12 – Percentage of interviewees per age classes. ... 275

13

Index of figures

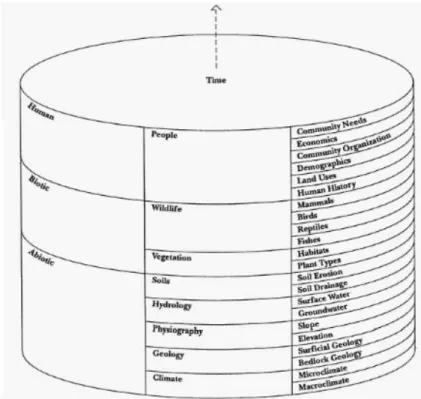

Figure 1 – A representation of the landscape concept as it seen according the LCA approach (Source: Swanwick and Land Use Consultants 2002). ... 87 Figure 2 – Ian McHarg’s “layer-cake model” (Source: McHargh, 1969). ... 125 Figure 3 - The Ecosystem Services framework according the European Union vision (Source: Mapping and Assessing Ecosystem Service – MAES 2013). ... 170 Figure 4 – Representation of the “twofold approach” of the landscape management. .. 213 Figure 5 – The zonation of BR landscape (AA. VV. 2014). ... 249 Figure 6 – Spider charts representing the average ESP values for each CICES classes (Cl) in sections 1, 2, 3. ... 254 Figure 7 – Boxplot showing the distribution of distances (m) of the reports from the centroids per each ES Class. ... 255 Figure 8 – Distribution of average ESP values in the CLC polygons that contain the stakeholders’ reports for the Section Provisioning. Three color scales represent the three CLC classes, each one with four grade of intensity of ESP value. In brackets, the corresponding CLC classes attributed to the polygons are indicated. ... 257 Figure 9 – Distribution of average ESP values in the CLC polygons that contain the stakeholders’ reports for the Section Regulating and Maintenance. Three color scales represent the three CLC classes, each one with four grade of intensity of ESP value. In brackets, the corresponding CLC classes attributed to the polygons are indicated. ... 258 Figure 10 – Distribution of average ESP values in the CLC polygons that contain the stakeholders’ reports for the Section Cultural. Three color scales represent the three CLC classes, each one with four grade of intensity of ESP value. In brackets, the corresponding CLC classes attributed to the polygons are indicated... 259 Figure 11 – The twelve pictures used for analyzing the interviewees’ visual perception of the landscape. They comprehend 6 “beautiful pictures” and 6 “ugly pictures” (with some impactful elements). ... 278 Figure 12 – The nine pictures used for analyzing the interviewees’ visual perception of their most familiar landscape. ... 279

“Landscape is not merely the world we see, it is a construction, a

composition of that world. Landscape is a way of seeing the world”.

Cosgrove D.E. From “Social formation and symbolic landscape” (1984). Tavone A. – “Cohabitation”. Molly Bog, Vermont (Fall 2013).

17

Introduction

Nowadays, the landscape issues are becoming actual always more, because we live in world that we are transforming so fast that sometimes we cannot recognize what we are surrounded by (or we do not reflect enough about its changes). And the landscape is the expression of this surrounding space: “actions and interactions of natural and human factors”, states the European Landscape Convention (ELC 2000), a continuous transformation that gives the dynamic character to the landscape. It is not possible to stop the changing landscape, but it is a civic duty to manage it, unless to destroy or degrade the matters and functions that can allow the natural and semi-natural ecosystems to work in balance. Yet, what it risks is also another component of the landscape if it is not well managed: the cultural values enclosed in the shapes, the social expressions, the traditions, the artifacts and the jobs, found in the landscape. “As perceived by people” the ELC still states by defining the landscape, because there is not landscape without a human perception of it.

The rural landscape is a special and, at the same time, challenging one to be managed in terms of both material and immaterial resources, and the possible risks are, for example: high productive pressure, cultural identity loss, pollution load made by agricultural practice, soil consumption, natural reforestation in consequence of the abandonment of marginal agriculture, fragmentation of landscape patches that compromises the high functionality of ecosystems and the conservation of biodiversity. For all and not exhaustive these threats potentially belonging to the rural landscape, important driving forces need to intervene: the social cohesion and the sense of place expressed by people who live the rural landscape, the renovation of social values by keeping alive the traditions and the aspirations of local communities, the planning of shared actions towards a sustainable use of the landscape, the inspiration of use the rural landscape as a special classroom for educating people to "cultivate plants and souls". The rural landscape is a big commingling of fragilities and potentialities that should be constantly balanced by an aware and integrated planning, where all the diverse beneficiaries are called to take care about it, for managing their own future well-being.

18

In this broad framework, the present thesis work moves around, with the main aim of analyzing how the community engagement and the ecosystem services (ES) assessment can be used for improving the management of the rural landscape.

For reaching this objective, the research starts from framing the main Italian and European address and regulatory systems of reference for the landscape management, specifically about the rural landscape, which is analyzed in its fragilities and potentialities in biophysical, economic and sociocultural terms. Linking the expert and local knowledge is a key step explored for building up an integrative approach for the rural landscape management (Chapter 1).

The community engagement is a priority to consider in the landscape management, because people who live and enjoy the landscape have the duty to understand how it is transforming and, in consequence of their needs and future perspectives, they have the possibility to decide in what direction orient the management actions. It should say that the “power of changing” needs to be led by a “civic awareness”. Hence, more attention needs to be given to the participation practices in the decision-making processes. There are many examples around the world that include the community engagement as a fundamental tool to reach, first, a common vision, and then to plan the actions for improving the conservation and/or the transformation of the landscape according to a shared intervention line. Case studies are shown from Europe, Italy and Vermont by focusing on the participative modalities and the reasons at the basis of the involvement: the community engagement, indeed, has not to be considered a finality, rather a mean (Chapter 2).

The involvement of stakeholders in the landscape management is important but it is not enough. Indeed, people’s actions for performing the landscape management have relevant responsibility for driving changes (and adding values at landscape) in terms of ecosystems functions, and, consequently, related services. Thus, a basic step for improving the landscape management is to increase and deepen the knowledge by assessing the ES. A broad overview of the ES approach is given, from global to local scale, by focusing the attention mostly on the important role played by the social perception of the landscape ES by stakeholders and how this knowledge can be integrated into

19 decision-making processes for improving the landscape management. For this purpose, a methodological “twofold approach” to include a framework of objective and subjective data aimed at an integrated and multidisciplinary landscape management is presented (Chapter 3).

Finally, an application of this proposed approach is shown in the area of “Collemeluccio-Montedimezzo Alto Molise” Biosphere Reserve, in Central-Southern Italy, recently enlarged by UNESCO. The research is mostly oriented to investigate the subjective data correlated to this landscape, in particular by analyzing the ES perception of different stakeholders, while the objective data are considered already available thanks to several studies and researches that have been carried on during the years. This application represents a first attempt that wants to put in practice a general and theoretical approach, which derives from the analysis of inputs and good examples reported in this thesis work (Chapter 4).

The “twofold approach” here proposed is thought to be flexible and applicable to any typology of decision-making process, at large or small scale, that aims the landscape management.

CHAPTER ONE

The landscape management

22

1. THE LANDSCAPE MANAGEMENT

1.1 Definitions and regulatory tools: an overview

Contents:

Visions and definitions of landscape

Origin and evolution of the landscape concept in the Italian and European regulatory system

The landscape plan: objectives and functions for managing the landscape in a trans/multidisciplinary perspective

The first time someone wrote about the landscape in literature was the poet Francesco Petrarca, when in 1336 climbed the peak of Monte Ventoso, or Mont Ventoux, on the South-Western Alps in France (Küster 2010). All along the hiking, Petrarca was attracted by the natural phenomena, the mountains, the valleys, the river and the sea, whom shapes and beauty he interpreted according to his personal experience. Once on the peak, all these elements were too far away that he was not able to recognize the water flows, the sea waves, the single trees, nor the sparkly minerals on the rock walls. At that point, he realized that only when all the images rejoin in an overall view, then it is possible to recognize a landscape.

According to Petrarca’s vision, the landscape is what a man perceives in his own environment, with which he is in relation; the visible things as well as the invisible ones, which the thought can build up, make the landscape. In the same way, the naturalist Alexander von Humboldt assumed that when a landscape is examined, it brings together all that is animate and inanimate (von Humboldt, 1998). The recognizing process of the landscape relationships might last long, even a whole life, and the impulse to start this process can be transmitted throughout generations, like the traditions. Continuously, new landscape relationships appear, but sometimes not the right importance is given to that, because the details analysis is often favored to the synthesis results, which presumes, moreover, to be found in different disciplines, even they are distant each other.

23 During the centuries, the landscape concept has being continued to keep a strong connection with the aesthetic and perceptive dimension, also since the beginning of XX century and over. Indeed, in the Italian tradition, the landscape notion has been tied with the conservation of cultural heritage (Settis 2010), and the law promoted by Benedetto Croce in the twenties (National Law 778/1922 about the preservation of natural beauties and remarkable historical buildings) defined the landscape as the material and visible representation of the homeland (Ferrara et al. 2007). The consideration of shapes perception and the beauty (Romani 1994) is the meaning found inside a subsequent regulation, the N.L. 1497/1939 about the protection of natural beauties, where there is not the word landscape, but its notion is assimilable to “beauties as a whole”. Moreover, both the laws spoke about regulatory plans or territorial plans to be design to avoid that a detrimental use of certain areas compromises those beauties. Even the Italian Constitution in 1946 exalted the landscape notion in the Art. 9, associating it to the historical and artistic heritage and subjected it to a protection regime. This means that the landscape protection is an Italian fundamental principle and that the Country territory, with its environmental and cultural elements, is a constitutional value itself (Sandroni 2012). The landscape restriction is the main tool contained in the “Galasso Law” (N.L. 431/1985 about the protection of areas of particular environmental interest), extended its action to many broad landscape categories (such as cost areas, mountains, rivers and streams, volcanos, etc.). Even if, from one side, the N.L. 431/1985 included the necessity to protect a wide portion of the Country territory through restrictions and plannings, from the other side it presented some problems and uncertainties about the attribution of multiple competencies amongst institutions regarding the landscape management (Agnoletti 2010).

The growing interest and necessity for managing the landscape raised across the decades since the important milestone at European level, with the European Landscape Convention (ELC) signed on October 20, 2000 in Florence by 45 EU Member States. The ELC arrived in a moment of high consciousness matured by the Governments to understand the direction through which advising institutions and populations for managing their territories in evolution, giving some tools and recommendations for leading people to enjoy a landscape of quality and encouraging them to have an active

24

role in the landscape transformation (Priore 2005). Indeed, since its preamble, the ELC states that “the landscape is a key element of individual and social well-being and that its protection, management and planning entail rights and responsibilities for everyone” (Council of Europe 2000). The well-known definition of landscape by ELC points out that the landscape is not simply a background where the man is only a spectator, but it represents the entire scene within which the man acts as a protagonist (Agnoletti 2010). Indeed, by definition “landscape means an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors” (Council of Europe 2000, art. 1). Therefore, the different landscapes whom give shape to the European territory are the contexts where populations experiment the representation of their own identities and evolutions. Definitely, the ELC pushes State authorities to make the local entities responsible about the landscape values and, simultaneously, to develop activities to raise awareness in people regarding these themes. In this way, a social request of (a quality) landscape is possible to build up, of which the local and regional authorities must take charge so to trigger virtuous circle aimed to the outbreak of a real widespread consciousness of the landscape (Priore 2005). The ELC compels the Member States of Council of Europe whom ratify the Convention (until today they are 381) to develop political programs specifically regarding the landscape, with activities of outreach, training and education aimed at making actors, both private and public, responsible for their own actions concerning the landscape. In this sense, this is a process of democratization of the landscape.

The ELC has imprinted an important turning point to the landscape policies under different points of view: first of all, the complex meaning attributed to the landscape as an expression of the common cultural heritage and the foundation of local identities; the recognition, even juridical, of landscape values to the whole territory (indeed, the ELC indicates three broad different kinds of landscape - the outstanding landscapes, the everyday ones, as well as the degraded landscapes – providing three different approaches

1 http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/Commun/ChercheSig.asp?NT=176&CM=8&DF=&CL=ENG [Last

25 for their management, but each of them is worthy of being considered always a landscape); the populations’ leading role to determine the choices for protection and valorization of their landscape through their expectations and perceptions. An innovative management of the landscape, with its natural and cultural heritage, needs some specific measures of protection, but also an articulated set of policies, as ELC recommends, assessing and dealing with different problems regarding tangible and intangible values, risks and threats of the landscape (Gambino 2013).

The strong resonance of ELC in Italy was conveyed in the Agreement between State and Regions regarding the landscape in 2001. The Agreement aim was to define the activities of both the Minister of Cultural Heritage and the Regions, consistently with the ELC, about the landscape planning and, more in general, the collaboration processes amongst the different public administrations about these topics. That Agreement was also the result of such an awareness that the landscape is also a national economic resource and its protection can lead the Country towards the sustainable development objectives.

After this step, the national law went towards the most recent regulatory piece regarding the landscape, with the Code of Cultural Heritage and Landscape – hereafter, the Code - (Legislative Decree 42/2004 and its subsequent L.D. 156/2006 and 157/2006, which modified and integrated the Code in the part regarding the cultural heritage and the landscape, in consequence of the Italian ratification of the ELC, occurred in that year). The landscape definition given by the Code accepts the ELC one. Indeed, in the article 131 of the Code, landscape means “portions of territory which distinctive characters derive from nature, human history and their own mutual interrelations” (art. 131, paragraph 1, as modified by L.D. 157/2006). “The protection and valorization of the landscape safeguard its values as manifestations of perceptible identities” (art. 131, paragraph 2, as modified by L.D. 157/2006). Even considering the coherence between the Code and the ELC in terms of landscape definitions, the ELC specifies the necessity to include the landscape inside the urban and territorial policies, implying important repercussions on the territory governance; this is not completely covered by the Code, because it seems attributing the aim of implementing values, objectives and rules of the territory only to

26

the landscape planning, even though in connection with other plans (such as: the regional plan for the forest sector or the rural development, the territorial plan for the coordination of the provinces, the municipal or intermunicipal plan, etc.) (Balletti and Soppa 2005). Just about the measures of coordination with other territorial planning tools found in the Code, the national and regional programs regarding the landscape management need to be designed for achieving the economic development. This means that the protection and valorization of the heritage go towards a programmatic meaning, not only towards a binding one, focusing the attention, in this way, also on the investment of resources for incentivizing the implementation of projects and best practices in this field (Agnoletti 2010). Furthermore, as the Code recalls, the public administrations need to work for cooperating in the planning sector and to implement training and educative activities, as the ELC recommends.

The Code has introduced the obligation for the regional authorities to draw up the landscape plans together with the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, recognizing in this way the inescapable necessity not only to protect but also to manage and valorize the areas characterized by strong landscape values, and the important requirement of healing the too much long conflict between State and Regions about the landscape matter. Therefore, the landscape plan is considered the fundamental and reference tool for the landscape policies in Italy. Each regional authority designs the landscape plan, which contains a set of actions for recovering and valorizing the territory, then to be proposed to the local institutional levels (sector policies). Usually this conveys into: interventions on soil protection, recovery of environmental systems and historical and cultural heritage, the establishment of parks and protected areas aimed at the development of equipment and routes for the environment and landscape fruition. More rarely the plans set in motion direct actions of conservation, enhancement and requalification, generally subject to the adoption of subsequent projects or programs, which constitute tools for different legal nature of implementation. The approval procedures of the landscape plans imply the institutional consultation, the participation of stakeholders and actors involved in the protection of “widespread interests” of the landscape.

27 Moreover, the landscape plan, starting from the recognition of the landscape assets and, therefore, the existing restrictions, has the power to strengthen them, expand them and to set up new ones, while it cannot reduce or, worse, eliminate them in any way. The Code prescribes that the landscape plan makes the recognition of all the landscape assets, which means essentially the analysis that allows verifying the real state of the intrinsic values of a certain landscape, with respect to the assessment made at the time the decision to protect it. Hence, it derives the provision of protection measures, the processing conditions of use, but also the evaluation of possible expansion of the restriction (Sandroni 2012).

According to Gambino (2013), because a landscape plan can contribute to implement effective management policies of the territory, it must follow two prerequisites:

a) That the plan expresses an authentic "landscape project", the result of a continuing process of drafting, participation and social sharing, based on the comparison explicit and transparent the interests involved; to this purpose, it is crucial that local communities and other stakeholders are considered not mere spectators, but actors and protagonists of the project, sharing the responsibility. b) That the landscape project articulates at all levels of the fundamental territorial

government, from the regional, provincial and municipal ones, until to the operational projects, triggering virtuous processes of trans-scalar interaction. This means that the landscape plan needs to be a tool able to connect the planning and regulatory aspects to the management ones (which should be as much flexible as possible), becoming a sort of “container of projects”, which have to be consistent with the plan itself (Balletti and Soppa 2005).

The set of territorial policies can influence or determine the unceasing transformation of the environment and the landscape at different levels and in different sectors (such as soil conservation, water management, agriculture, forestry management, urban planning, engineering of the territory, culture, training, social communication, etc.) (Gambino 2013). This means that it is a priority to considering the landscape always under

28

its multidisciplinary light. Indeed, landscape is the visible expression of both the environmental and the cultural systems, and because they are so integrated each other, it needs to study and interpret the landscape phenomena with an interdisciplinary regime. Moreover, the transdisciplinarity extends the interdisciplinarity concept, because the former include the participation of and amongst actors from different competencies. Indeed, in the process of sharing, aimed at the landscape management, generally not only the bearers of expert knowledge are called to participate, but also the actors of the territory, from policy makers to the inhabitants (Gissi 2011). Often this goal is hard to achieve, mostly due to the different languages and interpretive paradigms holding by all the disciplines involved in the landscape management, like engineering, urbanistic architecture, economy and social science, and the landscape ecology. Just the latter is remarkable to be mentioned regarding its important role in the research and reflection about the landscape. The aim of landscape ecology is to understand the existing ties amongst structures and functions of landscape and, in particular, to deepen the multi-spatial and multi-temporal research to be able to give answers to the processes, both planned and under way, and to build up an indicative and proactive methodology, through analyzing the changes, able to anticipate future approximate scenarios. The landscape ecology can be considered, with its integrated and transdisciplinary vision of dynamisms of natural and human matrix, the conceptual and technical foundation for a reformulation of the spatial and urban planning, in the sense of those environmental and landscape needs which require, for their importance, a growing consideration (Balletti and Soppa 2005).

There are two different levels of problem concerning the integrated management of the environmental and landscape resources: the first one regards how to modulate the integration amongst the disciplines connected to the territory and, then, amongst expert knowledge and widespread one; a second issue concerns how to introduce and integrate this new knowledge with the governance of the territory (Gissi 2011). Therefore, the communication difficulties amongst the sectors involved in the landscape planning are crucial and need to be overcome for building up a shared framework of knowledge.

29

1.2 The rural landscape in Italy: fragilities and potentialities

Contents:

Why addressing the rural landscape in this research: ecological, socio-cultural and economic factors that shape this type of landscape

The Italian and European policies for managing the rural landscape through the planning systems

Suggestions from two research projects aimed at improving the rural landscape management

The rural landscape is always affected by transformations: an overview on its main fragilities and opportunities factors

1.2.1 Why the rural landscape

The Italian surface is covered by two main landscape structures that are the agricultural matrix (55% of the total surface) and the forests and semi-natural matrix (40%); the rest is made by a mix of composite landscape with a transition structure between the agricultural and natural matrix, by wetlands, suburban and urban landscapes (5%) (Agnoletti, 2010). This means that, at national scale, the agricultural landscape is a physically continuous expanse, while the forests and the semi-natural environments constitute the mountainous “connective bone structure” of the peninsula. Indeed, historically speaking, the Italian landscape evolved mostly due to the agricultural techniques and practices coming in succession along the centuries and millennia, through a long process of transformation and adaptation to a hard natural environment, mostly mountainous and hilly.

Here, it is going to take into consideration the rural landscape not only because it is the main kind of landscape in Italy, but also for many other reasons: it is a highly rate changing landscape and often the transformations are not accompanied with a well-structured planning (Agnoletti 2010). It is the most productive landscape in terms of goods and services for humans (such as food, recreation, energy, water supply, etc.) and, therefore, it is the most used kind of landscape, often with no care about the exploitation consequences of its resources (Roura-Pascual et al. 2005; Schneeberger et al. 2007; Zomeni et al. 2008). It is the caretaker of many cultural values, because along the rural

30

landscapes, the strongest socio-economic systems evolved across the history, and these values are at risk due of fragility factors, which affect the rural landscape (Dezio and Marino 2014). Despite that, it is also characterized by many potentialities regarding the implementation of the sustainable development, the biodiversity conservation and the quality of life (Barbera et al. 2014).

First, it needs a distinction between the agricultural and rural landscape definitions. Emilio Sereni (1961) used to define the agricultural landscape as “that shape the man, in the course and for the purpose of its agricultural production, consciously and systematically gives to the rural landscape2”. Indeed, it refers to the spaces of production, rather the rural landscape definition – often used as a synonymous of agricultural landscape – has a broader meaning and it comprehends the settlements, infrastructures, the woods and the watersheds (Barbera et al. 2014).

The rural landscape is shaped by different kind of processes, which are social and economic, ecologic and environmental, political and cultural; each of them is driven by different factors.

The socio-economic factors are: the socio-demographic dynamics connected to the population’s aging, the changes in the social structure al local level, the abandonment of rural towns and the migration processes; mostly the latter two factors determine the marginalization of the rural landscape. Moreover, the big urban areas exert an attractor effect towards the orientation of the productive and social processes. The restructuring of land, the productive specialization and intensification are other important driven factors for shaping the rural landscape in the direction of trivialization.

The ecological and environmental factors are: the steady increase in the share of naturalization and the extending woodland; the pollution of surface water, groundwater and air, as well as the waste accumulation; the soil erosion; the climate change effects at midterm.

2 Translated from the original sentence: “quella forma che l’uomo, nel corso e ai fini delle sue attività

31 The political and cultural effects able to shape the rural landscape are: the role of the supporting tools to the incoming and of the farms for guiding production processes and the cultivating choices; the pressure of urbanization, in some cases linked to a chaotic infrastructural development; the inadequacy of the tools that fit the landscape in the policies of regional planning, in the environmental management and in the protection of public property, even with respect to investment in research and training. Another one is the cultural attitude, sometimes contradictory, that manifests itself on the one hand, in increasing demands to preserve the landscape, and on the other party, in harmful behaviors towards it.

All these factors act in guiding the process of transformation of the rural landscape. It has been demonstrated that the numerosity of natural and seminatural habitats in the rural landscape is correlated to the richness of the species and, therefore, the reduction of their number or their disappearance is an indicator of biodiversity loss (Billeter et al 2008). The high ecosystemic biodiversity characterizing the rural landscape (Barbera et al. 2014) is expressed through a composite mosaic of cultivation tiles (according to the land use), connected by ecological corridors (such as, water courses, tree lines, hedgerows, dry stone walls, etc.) which link them each other and, by allowing the interactions amongst species, energy and material, and they ensure the productive and ecological efficiency. Moreover, a high level of animal and plant biodiversity is not only an asset in itself, but also a prerequisite for the functionality of ecosystems. In fact, biodiversity also carries ecological services such as the maintenance of the nutrient cycle, the regulation of microclimate and the local hydrological assets, the suppression of harmful organisms, the detoxification of contaminants (Altieri 1999). Biodiversity also allows the maintenance of ecosystem connectivity of the landscape, which is a further ecological function (Forman 1995).

Another important asset characterizes the rural landscape: the multifunctionality. It derives from the concept that the rural land is able to produce not only agricultural goods, but also environmental functions, such as the biodiversity, the hydric resources, the soil fertility, and cultural values, like people’s identity, aesthetic and spiritual values. In this sense, the agrarian policies recognize all these aspects attributed to the rural

32

landscape as a public good and, as consequence, drive their measures to increase the farms incoming (an example is the agriturismo). Still, in terms of policies in favor of rural landscape, also the biodiversity finds an important position for its protection, especially through the action of farmers, seen as “biodiversity’s caretakers” of the agri-forest ecosystems. In this perspective, a Life Project called “DINAMO3” was co-financed by EU in the rural landscape of Lower Molise, in Central-South of Italy. The project, coordinated by the University of Molise, aimed at the protection of biodiversity through direct actions mainly made by the farmers voluntarily, for instance the installation of nests in their farmlands to allow the Red kite (Milvus Milvus) and the European roller (Coracia garrulus) to go back for nesting in the area, or the restoration of natural vegetation to create extended habitats in agricultural environment to encourage the presence of birds and reptiles species (also fostering the connection amongst the farmlands and the Natura 2000 sites). In addition, also some public areas managed by the municipalities involved in the project were reserved to these kind of actions for increasing the biodiversity. That project was a good model for demonstrating that the multifunctional and productive activities of the rural landscape reconcilable with the protection of biodiversity and the direct involvement of private and public entities are possible and successful.

Normally, when running think the landscape in general, it is rarely associated with the economic aspects. This is because, commonly, the man connects the idea of landscape (also the rural one) mostly to its aesthetic and spiritual values rather of its monetary features (Tempesta 2011). What it lacks is a broader concept of the potential benefits that the rural landscape can represent for the society.

Economically speaking, the landscape can be considered a pure public good, for which, in the absence of the principles of excludability and rivalry in consumption, it is not possible a market formation. Obviously, this does not mean the landscape cannot have a value, but it may not be in any case the subject of production for mercantile purposes from a private, and it will not have a price (Tempesta 1997). Moreover, the landscape is also an externality (positive or negative) of the anthropic activities and, specifically for the

3 DINAMO means “Increasing endangered bioDIversity iN Agricultural and semi-natural areas: innovative

33 rural landscape, of the agri-forestry-pastoral activities. The consequence is that the quality of the rural landscape does not depend on an intentional intervention of a farmer who works only for getting an economic profit, but it is properly an external effect, not programmed by his own activity. For example, the conservation of a historical rural landscape represents a positive externality, because the farmer does not receive a remuneration for the landscape advantages he contributed to produce for the collectivity, but only for the goods he is able to deliver to the market. The opposite situation is the case of the negative externality: in the same example, the farmer makes to burden on the collectivity the cost (which means the loss of quality landscape) that he is not supposed to reimburse to the citizens.

Thus, there is a discrepancy between the mercantile and social values regarding the rural landscape, and, sometimes also between perceived and real values, that can cause the disappearance of historical landscapes or their decline. Bringing back the previous subject as an example, the farmer, as an entrepreneur, would gain the maximum profit from his own work and rural land. If a reduction of the profitability from the cultivation occurs and if the productive factors become less remunerative than other possible jobs to run, he will have few choices: he can stop cultivating or he can implement productive techniques that allow him to get appropriate profit margins. In the first hypothesis, the abandonment of production will happen: in the second hypothesis, the introduction of new productive techniques and the implementation of new changes in land will occur. In both cases, the result will be the transformation of the landscape as inherited from the past.

To avoid the incapacity of the market to guarantee an adequate level of quality landscape there are two main ways to take, even not exclusive: the imposition of landscape restrictions and the providing of grants (Tempesta 2011). The landscape restrictions imply costs for individuals in terms of lost income and they determine an insufficient use of the productive factors, therefore the necessity to find new and more profitable jobs. The restrictions are conceived as an acceptable tool socially only if their incidence on the farmer’s income is not so much high. In the opposite case, they can

34

encourage phenomena of land abandonment, increasing, in this way, the decline of quality landscape, rather than stopping it.

Grants are provided by public entities, mostly from European Union and, sometimes, from national level, but often they are insufficient or hard to obtain. To avoid these problems, there is the possibility to carry out volunteer instruments aimed at the rural landscape conservation without a public intervention (Reho 2006; Marangon 2006). One of the most effective example in this direction is the rural tourism, because if it is linked in some way to the quality of landscape, the entrepreneurs, aware of the tourists’ preferences, would work voluntary for preserving that rural landscape. In another case, while the landscape is perceived as a quality indicator from the consumers of a typical agricultural product, its conservation would guarantee higher prices and higher profitability for farmers’ advantage. However, these opportunities often find obstacles at operational level. Indeed, in the rural tourism the costs of landscape conservation burden on all farmers of an area indistinctly, while the advantages are a prerogative of only few farms involved in selling services to tourists.

In synthesis and in the economic perspective, these elements belong to the rural landscape: the primary production of the resources; the ecological complexity starting from the ecosystemic complexity in the mixed farming; the valorization of the environmental resources at local scale, that is essential for the self-reproduction of the domesticated and wild species; the hydrogeological safeguard through the management of the woods, terracing and streams; the environmental cycle closure at local scale regarding the food supply (such as short chains between the producer and consumer), the waste (such as the synergic association between the breeding and the cultivation) and the water (low energy-consumption cultivar, and the choice of traditional cultivar better related with the local climate features); typical products produced in typical landscape, strongly linked with the food quality; the cultural identity of places in terms of mutual aid and non-monetary and supportive actions, which are typical of community relationships in the civic customs. According to an overall view, the rural landscape is a system that requires quality (e.g. in the sustainable use of resources and in the productive systems)

35 and, at the same time, demonstrates quality (e.g. in the aesthetic values and in the ecological complexity).

There is another remarkable aspect regarding the rural landscape, which is worth to underline: there are some compositional elements, which recall an innate perception of the man, dating back to the human kind evolution. Indeed, the visual perception has had a fundamental function from an ecological point of view: in the environment where the human being spent the majority of its evolutionary phase, the African savanna, only a precious perception of the external environment could give to individuals a chance to survive. Therefore, the ways of visual perceiving the environment, and so the landscape, are an essential component of the genetic heritage as it has been selected in millions of years (Tempesta 2011). Some decades ago, Appleton (1975) indicated that a pleasant landscape is made by those elements that make an environment favorable to survival. These elements, typical of African Savanna, are scattered trees, woods alternated to open spaces, small streams and curvilinear profiles of the ground. These characteristics are assimilable to the ones that it can be found in the rural landscape; that is why this kind of landscape is mostly perceived aesthetically beautiful and relaxing from people. This instinctive component of the landscape perception is connected with a sense of safety that a well-known environment (since millions of years) conveys to people.

There is also a social component of the landscape perception, which is related to direct capacity of man to modify the environment for his own living and for his community’s too. The environment transformation is one of the processes through which a social group affirms its own identity and, as consequence, all the signs and symbols belonging to that landscape will allow the cultural and social stability of the collectivity or the group that has built up that landscape (Costonis 1982). In this perspective, considering the historical, social and economic processes characterizing the rural landscape, intrinsically it has strong cultural and identity values, which should be valorized and protected.

A right understanding of whom are the values of the rural landscape is a basic element of a good definition of effective and locally shared territorial policies.

36

Just in terms of regulation, the Code, which has been discussed above, and its planning instruments can have important potentialities towards the rural lands, because they refer to the whole territory: in this way, the agricultural areas turned from not interesting place to be planned (before the entry into force of the Code), excepted for some “excellent goods” already indicated to be protected, into strategic components and “connective tissue” for a new landscape planning. However, the Code does not consider the rural landscape as a real category, and this implies, under a binding point of view, that a wood is always a wood, even though someone decides to substitute a centennial chestnuts wood with a coniferous one, because the latter is more productive for industrial purposes. This is the evident limit of a legislation that covers the environmental heritage, but not specifically the rural landscape (Agnoletti 2010).

In the last twenty years, the general interest for the landscape issues grew, because the need of changing the economy models only focused on the production and the industrialization started to evolve. Indeed, the conservation and valorization of the landscape, especially the traditional and multifunctional one, have entered in the regulatory systems, both European and national one (the already cited ELC, and the UNESCO policy regarding the “Cultural landscapes4”, put into effect few decades before the ELC). Even the Community Agrarian Policy (CAP) has pointed out, along its history, the importance of taking care about the environment and its functions. Then the landscape with its valorization became progressively significant, especially in the presence of a multifunctional agriculture (Barbera et al. 2014). The Good Agronomic Environmental Conditions foreseen in the CAP concern the protection of the agri-forest landscapes, encouraging the keeping of diversification elements of the rural landscape, such as hedgerows, ponds, ditches, trees in rows, field edges, etc. Going downscaling in the agrarian policies, the most recent National Plans for Development include specific agri-environmental measures aimed at diversifying the cropping systems and, as consequence, also the landscape mosaic. Consistently, the Rural Plans for Development applied at

4 “Cultural landscapes are cultural properties and represent the "combined works of nature and of man"

designated in Article 1 of the Convention. They are illustrative of the evolution of human society and settlement over time, under the influence of the physical constraints and/or opportunities presented by their natural environment and of successive social, economic and cultural forces, both external and internal” (UNESCO WHC 2013).

37 regional scale contain several measures regarding the strong connection amongst the agriculture and forest sectors with the landscape protection.

All actions and interventions delineated by the agricultural and environmental policies in the European Union, which relate directly or indirectly to the rural world, cannot disregard the use of appropriate tools for multisectorial and multiscale planning, involving specifically socio-economic, historical, cultural and environmental issues. In this context, the concept of landscape, especially the rural landscape, can be a key link and summary for a true integrated planning.

1.2.2 A special issue: the historical and traditional rural landscapes

Beyond the European and national agrarian policies, it does not exist a unanimously recognized method to identify, inventory and characterize the rural landscapes (and the landscapes in general) in descriptive, multidisciplinary and multiscale terms (Barbera et al. 2014).

In front of this gap, an Italian research project, still in course, finds a niche by implementing a method to read, understand and interpret the traditional agrarian landscapes (PAT5) in the contemporaneity, identifying the compositional elements. It is a PRIN6 project called “The traditional agrarian landscapes of Italian agriculture: definition of an interpretive, multidisciplinary and multiscale model aimed at the planning and management of land”. The PAT can be defined as those landscapes present in a certain territory since long time and are stabilized or are evolving slowly in time (Marino and Cavallo 2010). This means that the PAT are the expression of specific socio-economic systems, which occurred to create them and keep them as they are. The method elaborated along the research project has an innovative component, because it comprehends historical and socio-economic analysis to understand the landscape evolution (from around sixty years ago till today), the anthropic choices, the meaning

5 PAT is the Italian acronym for “Paesaggi Agrari Tradizionali”, which means traditional agrarian landscapes. 6 PRIN means “Progetto di Ricerca di Interesse Nazionale” (Research Project of National Interest) and it is

38

progressively attributed to the landscape and which role all these information can play in the territorial policies.

These landscapes are characterized by the “traditional” condition: it can be found not only in the shape of an agrarian landscape, but also in the conservation of its (traditional) functions. Therefore, the land use and the historical persistency must be considered together with the presence (and, again, the persistency) of such environmental, social and economic functions to be defined traditional landscape. This is because the PAT have got a strong coevolutionary dynamic between the social project of the farmer and the natural system constraints where he deals with; it is a context where the maximum integration amongst human activities and natural factors occurs, and this determines relations of equilibrium and exchange in ecological, socioeconomic and cultural terms. According to Farina et al. (2003), the PAT are one of the most complex integration models amongst anthropic activities and nature, because the use of resources through the agri-forestry-pastoral practices is happened with technologies aimed at the biocenotic conservation.

The PAT model allows to read and understand the transformation processes of the agrarian landscape through three dimensions: complexity, connection and resiliency; each of them is declinable in the environmental, social, economic and settlement systems (Cavallo and Marino7, in Barbera et al. 2014).

Indeed, the traditional agricultural landscapes play a crucial role in the maintenance of biological complexity that is grounded in their own constituent characters or in the management techniques, which are the base of PAT preservation. The extraordinary complexity of shapes and structures that characterize the PAT is the prerequisite for the conservation of a rich biocenotic diversity expressed in species richness, either spontaneous or cultivated, in the genetic variability of cultivated lands. These features are visible in the complexity of land uses that often coexist in confined spaces of mixed cultivation in the strict sense or in the mixed farming spaces (cultivated and natural areas)

7 Marino D., Cavallo A. – Lo studio delle trasformazioni del paesaggio agrario: un modello interpretative:

39 and in the complexity of the environmental mosaic. Furthermore, the management of PAT, characterized by a low input technology, allows the conservation of animal biodiversity, instead strongly disturbed in the intensive agricultural systems.

In the PAT model, the connection is taken in reference of its ecological, economic and social values. The opposite of connection is fragmentation and in the landscape ecology it means a process mainly connected to the man’s action and defined as a mechanism through which an homogeneous land cover is divided into separated and/or removed parts (Farina 2001). In the research project, the connection dimension is useful to analyze the transformation processes occurred in the last fifty years and the deep modifications determined by the land use changes, which generated alterations in the traditional landscape matrix, reducing it in spots increasingly scarce and unconnected with the surrounding tissue. In this sense, the connection concept is extended from the environmental framework to the structural alterations of the landscape, investigating the landscape fragmentation as a complex modification, responsible of negative effects not only on habitats and animal and plant populations, but also on environmental functions, which are important for the human ecology, the historical permanencies and the morphological articulation of the landscape (Olivieri 2004).

The other fundamental dimension analyzed in the PRIN project about PAT is the resilience that is the capacity of an ecosystem to restore the equilibrium condition after an external disturb or intervention (Evans 2011; Walker et al. 2004). In the PRIN project, the resilience concept is useful to examine the relations amongst the agrarian landscape considered, the internal and external pressures on it and the variations of the physical and economic space borders of that landscape, identifying at the same time the changing factors. The PAT transformation processes are determined by profound changes in the land use and by its settlement structure occurred in the second half of the twentieth century. These transformations are largely made towards a progressive impoverishment of the forms and structures complexity of the landscape, the reduction of ecological and social functions, as well as a simplification of the production processes (Marino and Cavallo, in Barbera et al. 2014). Where this process has not happened, the persistence of traditional characters of the agrarian landscape can be identified, and, to be such, they

40

have to be complex and resilient. Therefore, the resilience becomes a proxy of the sustainability of natural and social systems. More generally, it expresses what the Anglo-Saxons call “capacity”, which means the intensity evaluation of the change that a landscape can suffer with no negative effects (Swanwick and Land Use Consultants 2002).

According to the PRIN project vision, the agrarian landscape is a matter of territory project (Marino and Cavallo 2011). Looking at the agrarian landscape means to conceive the space as a physical entity with specific socio-economic, geomorphological, agri-forest, environmental and ecological characteristics, to be investigated as resources for the city and the man, but it is also seen as a lived and perceived space endowed by shapes and meanings that can go beyond its own physical concreteness, which is also an inspirational motif of the ELC.

Under the light of the PRIN project, the attention to PAT in their shapes and meanings assume today a strategic role in the future management of agricultural systems, because one of the most important contemporary challenges is the identification of productive models in which the agronomic techniques can coexist with technological innovation, the environmental protection and its resources, and the respect for the natural and cultural values, by making them an integral part of the development of the various production chains (Biasi8, in Barbera et al. 2014). Greater attention to the enhancement of traditional agricultural landscapes can lead to the achievement of this goal, but also to improving the quality of the rural environment and thus the quality of life of those who live it or, for example, who are living it with the experience of tourism.

Another remarkable research project in Italy moved its steps from the necessity to compensate the lack of criteria for evaluating the influence of anthropogenic and temporal dynamics on the transformation of the rural landscape, mainly to understand the integrity level of the historical landscape. The methodology called VASA9 was developed during the research project for the enhancement of the monitoring system of

8 Biasi R. – Il PAT: caratteri generali ed evoluzione del concetto: 25-28.

9 VASA is the Italian acronym of “Valutazione Storico Ambientale”, which means historical and

41 the Tuscan landscape (Foster et al. 1998; Agnoletti and Paci 1999; Agnoletti 2002), and it is applicable to all the territories for which aerial photographs series or other historical documents are available, making it possible to reconstruct the evolution of land uses. Indeed, the land use is the base unit for the analysis, because the landscape is a specific area that can be considered as a mosaic composed of contiguous tiles, each one characterized by a different land use. In this perspective, the land use becomes, therefore, the basic element of the landscape, which is then described and assessed according to the characteristics of the overall structure and the internal structure of that mosaic.

The Italian Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forest Policies financed the project, in which many universities and research institutes were involved, because there was the need to analyze and better understand the role and the meaning of the historical and cultural factors, in relation with the biodiversity rate, of the semi-natural systems, where the man is too often put only under a negative light as a degradative or disturbance factor. Thus, the VASA assessment approach is particularly suitable to a vision of sustainability in which ecological factors are a functional support to the interpretation of the territories in which the man is the main actor, through a dynamic multi-temporal model based on comparative assessments and specific analysis tools.

The evolution of this research project went in the direction of drawing up a Catalog of the historical rural landscapes in Italy (Agnoletti 2011), aimed at laying the foundations for recognizing, conserving and managing in a dynamic way the historical landscapes and the traditional practices in the face of the economic globalization, the climate changes and the inappropriate policies passed across the last decades. Indeed, in Italy still there is a big heritage of rural landscapes formed during millennia that, even they are continuing their evolution process, conserve evident proofs of their historical origin, still keeping an active role in the society and economy. Those landscapes are indissolubly connected to the traditional10 practices maintained and transmitted throughout generations of

10 According to the author (Agnoletti), the word "traditional" refers to those landscape already existed

before the industrialization of the agricultural sector, formed by the shapes of properties and the cultivation techniques of agricultural and forest activities.

42

producers: farmers, shepherds and woodcutters. These are complex systems based on ingenious and varied techniques that provided an important contribution to the construction and maintenance of the Italian historical, cultural and natural heritage, representing the continuous adaptation to harsh environmental conditions, providing multiple products and services, contributing to the quality of life and producing landscapes of great beauty. The landscape heritage, the stratification of knowledge and experience related to traditional practices are key assets that must be protected.

However, multiple pressures force manufacturers to innovate agricultural techniques, often leading to unsustainable practices, the depletion of natural resources, the decline in productivity and the excessive specialization. This poses serious risks for the conservation of this economic, cultural and environmental resources, which constitute the traditional landscape, not only by interrupting the knowledge transmission necessary for its maintenance, but also leading to the socio-economic destabilization of the rural areas and the loss of competitiveness of the Italian agriculture. In this sense, the Catalog wants to testify not only the importance of the landscape as one of the historically most representative expressions of cultural identity of the Country, given the prevalence of rural civilization in the history of Italy, but also the universal value of the Italian landscape in the context of the human cultural heritage, which today seems largely to have been lost memory.

According to the VASA method (Agnoletti 2010), three are the fundamental principles on which criteria and indicators aimed at the rural landscape management are set up: significance, integrity and vulnerability (Fowler 2003; Romani 1994).

The significance refers to all the values expressed by the landscape; these values change from place to place and are not investigable in a preventive way, rather it needs to search them with specific investigations, neither they have to be confused with the conservation of the ecological aspects.

The integrity is a measure of the completeness and the degree of the maintenance of the landscape structure. A landscape that keeps intact its relations amongst the structure of its components, like in the mosaic of rural landscape, is able to satisfy the integrity relations.

43 The vulnerability represents the landscape fragility in respect of all the processes that might compromise its significance and integrity. The vulnerability does measure also the resistance to changing of a certain landscape. For example, the agri-forest composite structures are areas at high landscape dynamism, because they can transform themselves rapidly after a cultivation abandonment; instead, in the suburban landscapes it is easy to foresee an expansion of the artificial surfaces.

The Catalog has identified 123 traditional rural landscapes distributed in all the Italian regions, collected in descriptive sheets, which take into account their historical value, typical products and critical issues that threat their integrity, providing also addresses for their valorization11.

An interesting consequential result in terms of regulations that this research project brought is the approval of a decree (n. 17070, 19 November 2012) made by the Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forest Policies regarding the institution of the “National Observatory of the Rural Landscape, the agricultural practices and the traditional knowledge”. The National Observatory of Rural Landscape has the task to conduct a census of the landscapes, the agricultural practices and the traditional knowledge considered particularly worthy, and to promote research activities to deepen the values connected with the rural landscape, its protection, management and planning, even with the aim of preserving the bio-cultural diversity. Furthermore, the Observatory has to develop the general principles and the guidelines for the conservation and valorization of the rural landscape, with a special reference to the actions planned in the CAP.

1.2.3 Fragilities and potentialities of rural landscape

In the previous paragraphs, the ecological, social and economic features of the rural landscape have been described, even considering the two Italian research projects as important experiences and taking into account the regulation framework of reference.

11 For more information about the Catalog: http://landscapeunifi.it/it/info?start=5 [Last consultation:

44

The rural landscape is a dynamic system and for this reason, it is always affected by transformations over time. These changes can be seen as fragilities and potentialities regarding the rural landscape, of which main ones are listed here in a synthetic scheme (see below), looking at their driving forces and consequences, which are “readable“ on many Italian rural landscapes today.

Furthermore, in this paragraph some fragilities and opportunities aspects are deepened in their interrelations, because they are relevant for other topics dealt with the rest of the thesis.