C.R.Palevol16(2017)865–877

ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Comptes

Rendus

Palevol

www . s c ie n c e d i r e c t . c o m

Human

Palaeontology

and

Prehistory

Exploring

Neanderthal

skills

and

lithic

economy.

The

implication

of

a

refitted

Discoid

reduction

sequence

reconstructed

using

3D

virtual

analysis

Exploration

des

aptitudes

et

de

l’économie

lithique

de

l’homme

de

Néandertal.

Implication

d’une

reconstitution

de

la

séquence

de

réduction

discoïde

par

utilisation

de

l’analyse

virtuelle

3D

Davide

Delpiano

,

Marco

Peresani

∗BiologiaedEvoluzione,UniversitàdegliStudidiFerrara,CorsoErcoleId’Este,32,44121Ferrara,Italy

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received12February2017

Acceptedafterrevision19June2017

Availableonline31August2017

PresentedbyMarcelOtte

Keywords: Knappedstone 3Dvisualtechnology Refitting Discoidtechnology Neanderthal MiddlePaleolithic

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Lithicrefittingstudieshaveconsistentlycontributedtoaddresstwospecificresearchaims: theintra-sitemobilityandidentificationofpreferentialareasorlatentstructures,and thein-depthanalysisoftheknappingtechnologiesandcorereductionstrategies. Multi-plerefits,inparticular,canproducehighlydetaileddataonknappedstonetechnology. Elucidatinghumanskillsandlithiceconomy,apotentialstillrarelyevaluatedfor Dis-coidtechnology:astoneknappingmethodlargelyspreadacrosstheMiddlePaleolithic ofEurope.TheopportunitytoexploreNeanderthalknappingbehaviorisprovidedfrom theremarkablediscoveryofaprimarylithicwasteconcentrationintheMousterian Dis-coidleveloftheGrottadiFumane,Italy,datedtoatleast47.6kycalBP.Withacombined approachthatincludedthe3Dvirtualinteraction,wewereabletoreproduceacomplete reductionsequencethatsupportsthetechnologicalanalysisconductedonthelithic assem-blage.Resultsleadtoabettercomprehensionoftheknapper’stechnologicalandtechnical behavior,includingthedetectionandquantificationofeconomicobjectivesand productiv-ity.

©2017Acad ´emiedessciences.PublishedbyElsevierMassonSAS.Allrightsreserved.

Motsclés: Pierretaillée Technologievisuelle3D Reconstitution Technologiediscoïde Néandertal Paléolithiquemoyen

r

é

s

u

m

é

Lesétudesdereconstitutionlithiqueontconsidérablementcontribuéàlapoursuitede deuxobjectifsderecherche:lamobilitéintrasiteetl’identificationd’airespréférentielles oudestructurescachéesetl’analyseenprofondeurdestechniquesdetailleetdes straté-giesderéductiondenucléus.Desreconstitutionsmultiples,enparticulier,peuventfournir desdonnées trèsdétaillées sur les techniques detailledespierres. L’élucidationdes aptitudeshumainesetdel’économielithiqueestunpotentieldecesméthodesencore rarementévaluédanslatechnologiediscoïde:uneméthodedefac¸onnementdelapierre

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddresses:[email protected](D.Delpiano),[email protected](M.Peresani).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.crpv.2017.06.008

866 D.Delpiano,M.Peresani/C.R.Palevol16(2017)865–877

largementrépandueaucoursduPaléolithiquemoyenenEurope.L’opportunitéd’explorer lecomportementdetailledelapierrechezl’hommedeNéandertalestfournieparla remar-quabledécouverted’uneconcentrationdedébrislithiquesprimairesdansleniveaudiscoïde moustériendelagrottedeFumante,datantaumoinsde47,6kacalBP.Uneapproche com-binéeincluantl’interactionvirtuelle3Dnousapermisdereproduireuneséquencecompète deréduction,quicorroborel’analysetechnologiqueréaliséesurl’assemblagelithique.Les résultatsobtenusconduisentàunemeilleurecompréhensionducomportementtechnique ettechnologiquedu«tailleurdepierre»,avecladétectionetlaquantificationdesobjectifs économiquesetdelaproductivité.

©2017Acad ´emiedessciences.Publi ´eparElsevierMassonSAS.Tousdroitsr ´eserv ´es.

1. Introduction.Technologicalandbehavioral contributionoflithicrefitting;perspectivesinthe MiddlePaleolithicofwesternEurasia

Lithictoolsand assemblages(themostcommonand preservablefindsalongthePaleolithic)havealwaysbeen usedtodefineculturallyhunter-gathererhumangroups and species. Within the Middle Paleolithic, in particu-lar,thecontrastbetweentheapparenttechnicalstability andthewidevarietyoftoolsetsandknappingmethods attracted contributions from several scholars, each one withdifferentanalyticalpaths.Onlyinthelast decades, thetechnologicalapproachallowedustoinvestigateand understandindetailthebehavioralstrategiesintermsof humanadaptation(BamforthandBleed,1997;Inizanetal., 1999;Nelson,1991;Odell,2001), especiallywhen stud-iesonknappedstoneshavebeenintegratedwithsourcing studies,refittings,use-weartraces,microresidueanalysis, andtaphonomy.

Refitsinparticularcanproducehighlydetaileddataon technologicalevolution,humanskills,naturalandcultural formationprocesses,lithiceconomyandhumanlanduse (Czielaetal.,1990;Delagnes&Ropars,1996;Roebroeks, 1988; Skar & Coulson, 1986; Vaquero et al., 2007). In morerecentyears,thediscoveryofmultiplerefitsinthe EuropeanMiddle Palaeolithic archaeological record has providedopportunitiesfordirectcomparisonwithanalytic theories,alsoservingas a“control test”forthe techno-logicalapproachtothestudyoflithicassemblages.Inthis case,theuseofmentalrefittinghasthusmadea funda-mentalcontributiontotheunderstandingofthetechnical gesturesaimingtoexplorefurthertheirvariability. Men-talrefittingsshouldthusbeconfirmedifpossiblethrough real refittings, when extensive and complete, although thisevidencerarelyoccursandrelatestospecificevents. Refittingsmaybeequallyusefulincomingtoan under-standingofthe moreconceptual stages offlaking, such as,forexample,thepredeterminationofflakingproducts. Thankstothesediscoveries,itisalsopossibletoascertain theramificationsofthecorereductionstrategies,whichin somecasesintertwinewiththeexploitationofflake sup-ports.

While,mostoftherefittingevidenceconcerns assem-blagescreatedusingtheLevalloismethod(Delagnesand Ropars,1996;Roebroeks,1988),arangeofknapping meth-odswereusedbyNeanderthalsinWesternEurasia;oneof themostintriguingisDiscoidtechnology,whichcoversa widerangeofculturalcontexts(seeDelagnesandRendu,

2011;Peresani,2003).Examplesofmultiplerefitsarerare within Discoid lithic assemblages(Carbonneled., 2012;

Deschamps etal., 2016;Faivre,2011;Locht &Swinnen, 1994),probablyduetothespatialandtemporal fragmen-tation that characterizes the operating chains of these industries(Turqetal.,2013),whichinturncorrelatesto theeconomicbehaviorsthatareexpectedofhumangroups withanelevatedlevelofmobility(DelagnesandRendu, 2011).ConsistentwiththatobservedfortheLevallois,and even fortheDiscoid coreitself,thetechnologyprovides aconsistentsourceoffirst-choiceproducts,whichcould bepartofthetoolkitofhuntersaimingtomaximizethe potentialutility-to-weightratio.

The meaning of the word “discoid” has had a long metamorphosisfromthetooltothecoretotheknapping method.Thedefinitionhasbeenimpactedby methodologi-calandcriticaltrendsinlithicstudies,fromthetypological to thetechnologicalapproach, and finallyexperimental comparisons.Inthismanner,followingthedetermination ofsomemorpho-technicalfeaturesofthecores,an elabo-rationofaseriesoftechnicalcriteriaadheringtoaflaking methodhasbeendetermined(Boëda,1993;Gouëdo,1990). Thenewapproachhasmadeuseoftheanalysesofnoted archaeologicalcollections,turningtotheso-calledmental refittinginordertoreconstructthevolumetricdesignand architectureofcorereduction.Newlightwasshedonthe methodoverthecoursethe‘90sand2000.The variabil-ityofthetechnicalcriteriawasbetterdefined,leadingto a morecompleteunderstandingof thecomplex dynam-ics thatledtotheformationofthearchaeological lithic sets(Peresani(Ed.),2003).Anopportunitytoexplorethis particularknappingtechnologyisprovidedherefromthe remarkablediscoveryofaprimarylithicwaste concentra-tionintheMousterianDiscoidassemblageoftheGrottadi Fumane.

2. Materialsandmethods

2.1. Thearcheologicalcontextandthefindingofthelithic concentration

FumanecaveisasouthAlpinesitewellknownforits MiddleandEarlyUpperPalaeolithicsequencewith Mous-terian(unitsA11toA5),Uluzzian(A4,A3)andAurignacian levels(A2toD1c)(Broglioet al.,2006;Obradovi ´cetal., 2015;Peresani,2012;Peresanietal.,2008,2016).Within thelateMousteriansequence,theunitA9,explored exten-sivelyinthelastyears,isanensembleofthinlevelsand

D.Delpiano,M.Peresani/C.R.Palevol16(2017)865–877 867

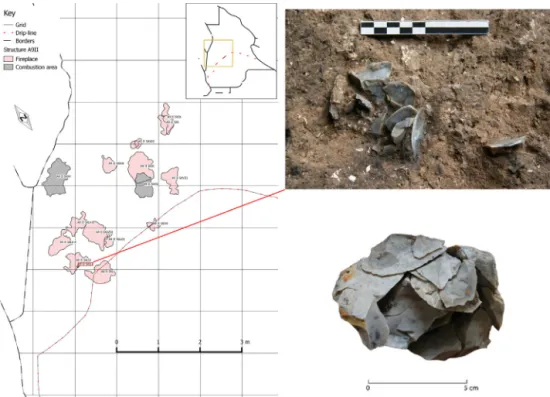

Fig.1. ThecontextofStructureA9IISXLII.Left,mapofthecavewithpositionofthehearthsandcombustionareasdiscoveredinlayerA9II(drawing:

E.Cocca);thepositionofstructureA9IISXLIIisindicated.Topright,viewofstructureA9IISXLIIafteritsdiscoveryandthepartialremovalofthefirst

unearthedartifacts;bottomright,refittedflakesandcorefromthestructure.

Fig.1. ContextedelastructureA9IISXLII.Àgauche,cartedelagrotteaveclapositiondesfoyersetdesairesdecombustiondécouvertesdansleniveau

A9II(dessin:E.Cocca).LapositiondelastructureA9IISXLIIestindiquée.Enhautàdroite,vuedelastructureA9IISXLIIaprèssadécouverteetletransfert

partieldespremiersartefactsdéterrés;enbasàdroite,écaillesetnucleusreconstituésàpartirdelastructure.

lenses composed of frost-shattered brecciaand Aeolian silt, diffused with sands and dark sediments because of intense anthropogenic accumulation. Thousands of knapped stones, micromammal, mammal, bird, bones (Fiore et al., 2016; López-García et al., 2015; Peresani etal.,2011;Romandinietal.,2014,2016)humanremains (Benazzietal.,2014)anddwellingstructureswithhearths andtoss-zoneshavebeenbroughttolight;currently,A9 hasproducedover50structures,mostlyhearths,scattered atthecaveentrance,withmoreinthewesternthaninthe eastern zone, inproximity tothepresent-day drip-line. The chronometric position of A9 is provided by only one reliable date among a few other measurements of 47.6−45.0kycalBP(Highametal.,2009;Peresanietal., 2008).

A9 records theappearance of anexclusively Discoid industrysandwichedbetweentwoLevalloisculturalunits: A10 below and A6 above, with the sterile layer A7 in between (Peresani, 2012). The production system was structuredin two reductionsequences, amain one and a secondary one,withthesame sharedgoalof produc-ingshort,strong,andsometimespointedimplements,as evidencedbypseudo-Levalloispoints,backedflakes,and subcircular, quadrangular or triangular flakes (Peresani, 1998).Theformer systemexploitedblocksand nodules, whereasthelatter,whichwassimplerandlessproductive, usedflake-coreseitheroriginatingfromby-products (cor-ticalflakes)orintroduceddirectlyontothesite.Thecores begantoyieldusableblanks rightfromtheinitialsteps,

withtheoutlinegraduallychangingfromunidirectionalto Discoid.

The2012archaeologicalcampaignexploredthe west-ernsectionoftheatrialzone,whichwaslimitedtothewest bythecurrentlyvisiblesectionattheentrancetogallery A.In proximitytothis section,UnitA9II,a thin anthro-pogeniclevelcontaininglithicartifacts,bone,charcoal,and severalcombustionstructuresandoverlyingtheA10 strati-graphiccomplexwasremoved.Thedensityofthelithic artifactsinthatareaistwotothreetimeshigherthanin theadjacentareas.Noparticularconcentrationsor pref-erentialdistributions ofspecific artifactcategories were identifiedduringexcavation,withtheexceptionof struc-tureA9IISXLII,a concentrationof a dozenflakes in sq. 68g(Fig.1).Withintheassemblage,whichcoveredafew cm2,theperipheralflakesslopedtowardsthecenterofthe structure;some,especiallythosetothesouth,werenearly vertical,whilethosetowardtheeastslopedtothewest. Thisarrangement seemstobe due topost-depositional deformationattributabletofreezing-thawingmechanisms, butrequires confirmation fromsoil-micromorphological analyses.Thesizeoftheartifacts,comparablewitheach other,thegrayMaiolicaflintandtheirstateof conserva-tionseemtoindicatethattheflakesoriginatedfromthe samecore,whichwasalsorecoveredduringthestructure’s excavation.Therefore,itwassimpletorefittheentire con-centrationtoformasinglereductionsequence.Amongthe flakes,smallfragmentsandchunksmadeofthesamegrey flint,werefound.

868 D.Delpiano,M.Peresani/C.R.Palevol16(2017)865–877

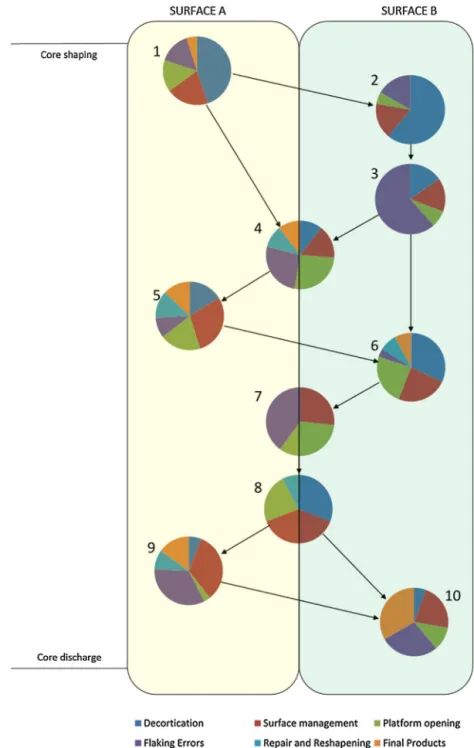

Fig.2. Thetenstagesofthereductionsequenceshowingtheexploitedsurfaceandthetechnicaleffectsontheknappingeconomy.

Fig.2. Lesdixétapesdelaséquencederéduction,montrantlasurfaceexploitéeetleseffetstechniquessurl’économiedelataille.

2.2. Analyticalmethods:traditionalandvirtual approaches

Refittingwasperformedprimarilywiththetraditional method, reconstructing the sequence according to the direct consequential position determined by scars and negatives.However,problemssoonaroseduetothe com-plexityofthetaskandtheneedforapunctualanalysis. Forthesereasons,wetriedadifferentapproachobtaining

three-dimensionaltemplatesof theartifacts,inorderto beableofanalyzethemmoreeasilyonavirtualsystem. As previously established in papers on lithic technol-ogyandotherdisciplineswithinprehistoricarchaeology (Bretzke &Conard,2012; Clarkson&Hiscock,2011; Lin etal.,2010;Richardsonetal.,2013),theanalysisof three-dimensionalmodelscanbeusedtoobtainmorphometric datathatwouldbeotherwiseinaccessiblewiththe tradi-tionalmethod.Forlithicrefitting,theanalysisisfocused

D.Delpiano,M.Peresani/C.R.Palevol16(2017)865–877 869

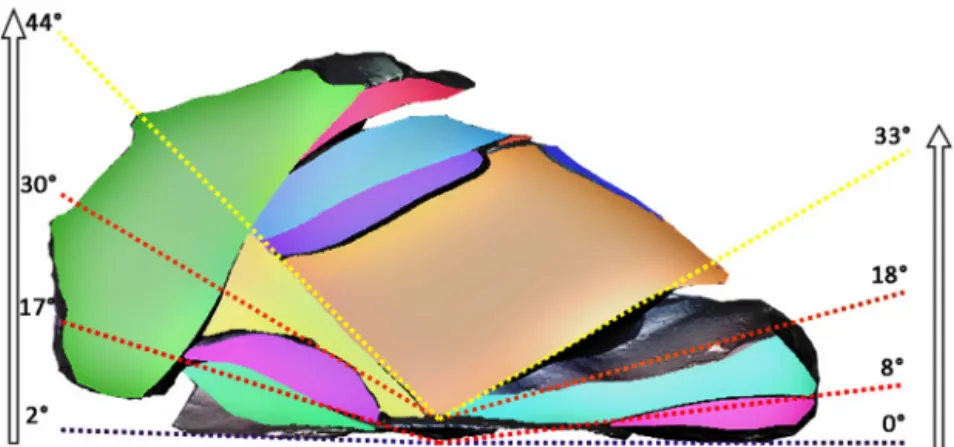

Fig.3. Cross-sectionsoftherefittedcore:theupperoneshowstheprogressionofthecorereductionviewedfromtheuppersurface(surfaceA),with

thedetachedflakessuccessionshowingaturningexploitationpatterninaclockwisesense,strictlyfollowingtheperipheraledgeaccordingtoadiscoid

concept.TheloweroneshowsthedivisionbetweensurfacesAandB,markedbytheperipheraledgealongwhichtheproductionisorganized.

Fig.3. Coupesdunucleusreconstitué:lapremièremontrelaprogressiondelaréductiondunucleusàpartirdelasurface(surfaceA),aveclasuccession

d’éclatsdétachésmontrantunpatrond’exploitationtournantdanslesensdesaiguillesd’unemontre.Lasecondecoupemontreladivisionentrelessurfaces

AetB,marquéeparletranchantpériphériquelelongduquellaproductionestorganisée.

onanalyzingnotonlythepiecesfoundbutalsoto inves-tigate the three-dimensional gaps produced by absent pieces. This method alsoallows theanalysts to bypass preservationandhandlingissuesthroughaneaseof inter-actionthat,inaspacewithoutgravity,removesreal-world limitations(Gartski,2016).Toobtainthescans,weused a structured light scanner, Breuckmann SmartScan 3D, developedbyAICON3Dsystems,alreadyperformedwith excellent results for prehistoric cave sites and artifacts (Breuckmann et al., 2009; Pastoors & Cantalejo, 2014; Pastoors & Weniger,2011; Tusa et al., 2013), including lithic samples(Slizewski&Semal,2009).Detailsonthe instrumentsandtheprocedureusedforachievingand elab-orating the 3D imagesare presented in Delpiano et al. (2017),whohavedeterminedthatthe3Dapproachisvery usefultointegratethewholestudy(inthesecases),butnot toreplaceitentirely.

3. Results

3.1. Reconstructionofthereductionsequence

Thankstothisapproach,ithasbeenpossibletoanalyze thechaîneopératoireinitsentiretyrecognizingatleast64 detachmentsthathavebeenset-upintimeandspaceina matrix.Thereassembledflakesconstructalmostthe origi-nalshapeoftherawmaterialpebble.Fewmissingartifacts indicatethatthegrayMaiolicaflintcobblehasbeencarried intothesiteintactoronlypartiallytestedafterpossible collectinginthestreambedlocatedafewhundredmeters fromthesite.

Thecobblewasoriginallysquaredshapewithsmoothed edgesandapronouncedconvexityononesurface,which wasconsideredappropriatefortheapplicationofthe Dis-coidtechnology.Thereductionsequencetookplacetotally atthesite asdemonstratedfromtheartifactsproduced duringthefirstdecorticationstagesuptothelastphase ofexploitationandthediscardofthecore.Alltherefitted piecescomefromstructureA9IISXLIIandwedidnotfind anyrefittedelementfromotherexcavatedareas.

Themorphometricfeaturesofeachdetachment (mea-surements,edges,presenceofcortexorhinged termina-tions)andthetechnologicalpositionalongthereduction sequenceframealistoftechnicaleffectsdesignedforeach flakeobtained.Theseincludedecortication,maintenance ofknappingfacesconvexities,creationofthestriking plat-form,mistakereparationsandtheachievementofthefirst choiceartifacts.Thereduction sequence hasbeen parti-tionedintotenmajorstageseachonefeaturedfromspecific objectivesandconsequencesandrelatedtothecoreface exploited(Fig.2).

Theoveralldevelopmentinthecorereductioncanbe seen fromthedissection ofthe availablerefittedflakes (Fig.3).Theknapperworkedouthistaskwitha reduc-tionina clockwisesense(with aviewfromthesurface A)alternatingtheproductiononthetwoknappingfaces, reachinganalmostcomplete 360◦ turnaroundthecore andalongtheperipheraledgeremovingmuchofcortical surface.However,not everydetachmentstrictly follows thepreviousone inthis sensebut many shifts or rota-tions are present; nevertheless, a global trend can be noticed.

870 D.Delpiano,M.Peresani/C.R.Palevol16(2017)865–877

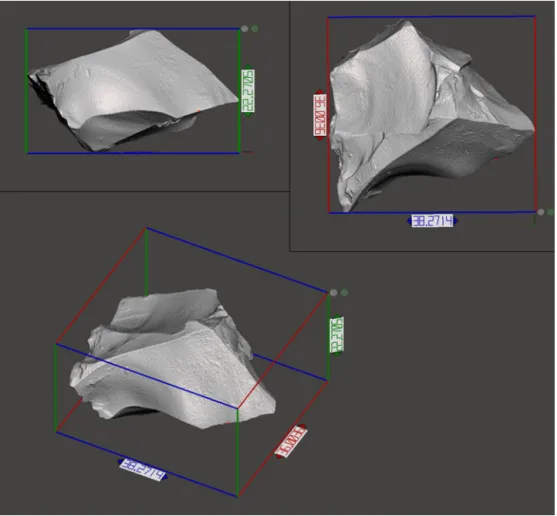

Fig.4. Differentviewsoftheresidualcorewithmeasurements(length,blue;width,red;thickness,green).

Fig.4. Diversesvuesdunucleusrésiduel,avecsesmesures(longueur,bleue;largeur,rouge,épaisseur,verte).

Therefittedsequenceistheexpressionoftheknapper’s decisiontoarrangetheexploitationontwoopposite, adja-centandsecantfacesfromtheearlieststage:thefirstblows (Stage1)weredesignedtoremovethecortexfromfaceA, outlineaperipheraledgefollowingthenaturalblock con-vexitiesandopenastrikingplatformfunctionaltotheface B,exploitedinthefollowingstage(2).Therefore,thetwo facesmaintaininterchangeable roles.However,in these earlystagesfaceAappearsmuchmoreconvexthanthe almostflatfaceB.

Framedinthisconceptofnon-hierarchicalsurfaces,the exploitationofteninsistedonthesamestrikingplatforms, wideand basicallyflat,that have beenobtainedby the detachmentoflargeflakesmostlycorticalandsecant.The reducedpreparation ofthestrikingplatform(adefining featureofDiscoidknappingwhencomparedwith Leval-lois)isexpressedbyflatorconvexbuttsandtheplatform left“brute”,avoidinganyfurtherpreparation.Theimpact pointsaresystematicallylocatedontheproximalconvex sidesofeachscar.

Thoughafterthefirstphasesofcoredesign,the reduc-tion proceeds within a fully Discoid concept, with the peripheraledgethatisgraduallyexploitedalongitstotal extensionby an apparentlyopportunistic production of

secant flakes obtained through chordal or centripetal blows. However, almost all artifacts played the role of predeterminantproductsandoftechnicalsolutionsaimed tomaintainthecentralandperipheralconvexities.Face Brevealsapreferentialexploitation:thissideofthecore islessconvexthanfaceAandwasknappedforobtaining almost exclusively core-edge removal products, also with cortical back. This face was in fact intentionally workedalongitsperipheraledgeforincreasingthecentral convexity.

Thekeyconceptsremainunvariedacrossthesequence: blows arealwayspracticedstarting fromtheperipheral edge andnever attesttheintentiontodeviatefromthe exploitationoftheseknappingfaces.Coresizereducesbut is unchangedinitsfeatures,beinghomotheticin accor-dance with the Boëda’s design (2013). In other words, noevidenceofapolyhedraltendencyhasbeendetected. When discarded, the core measured 38×36×22 mm (Fig.4).

Several knapping accidents repeatedly affected and compromised the progress of the reduction sequence, especially in stages 3, 4, 7 and 9. These occurrences have been observed with more frequency onthe same face,expressedinhingedfractures,overshootsorfrequent

D.Delpiano,M.Peresani/C.R.Palevol16(2017)865–877 871

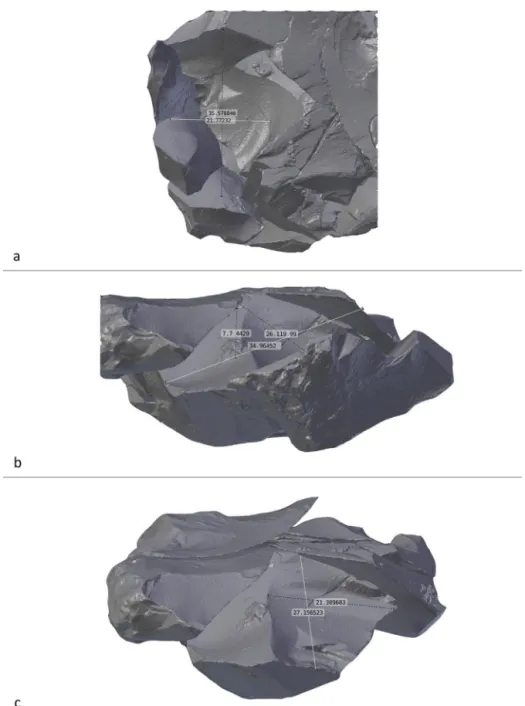

Fig.5.3Dviewandsizeofaflake,detachedbyacentripetalcorticalblowfromfaceAduringstage1(a);3Dviewandsizeofacentripetalflake,detached

fromfaceBduringstage5.Itisprobablyoneofthefirstfullyusableproducts(b).

Fig.5. Vue3Dettailled’unl’éclat,détachéparuncoupcorticalcentripèteàpartirdelafaceApendantl’étape1(a);vue3Dettailled’unéclatcentripète

no11,détachéedelafaceBpendantl’étape5.C’estprobablementl’undespremiersproduitsquisoitcomplètementutilisable.

fragmentations due to reiterated blows on improperly preparedzones.Thispattern denotesan oddand unex-plainableinsistenceinworkingtheseareasandcouldbe related to approximate preparation, poor accuracy and misapplication of the technical skills, if available. As a consequence, the knapper rearranged the core through reparatoryflakes,whichablatedandremovedtheerrors followingthesamepatternanddirectionoftheprevious detachments.

Finally,ithastobenotedthatthefirstchoiceproducts werepoorlyrepresentedintherefittedassemblage.This biasisaconsequenceoftheusingtheseproductsinthe caveorinanothersite,withthesetoolssubsequentlylost. Inthiscase,thethree-dimensionalapproachprovidesclues fordepictingandquantifyingthesemissingartifacts.

Summarizing, flakescar patterns combinedwiththe reductiondevelopmentseeninthevirtualmodelsuggest thatknappingwasorganizedviaunidirectional exploita-tionuntilstage3.Later,untilstage5,thepatternshifted tobidirectionalknapping:normallypatternedbymeansof chordalandcentripetaldetachments,almost perpendicu-lartoeachother,whichcorrespondstothebeginningof thecorerotationalongitsperipheraledge.Finally,asthe reduction advances,themultidirectionalcentripetal and convergentpatternreachesitsfullexpressiononboththe

corefacesandknappingbecomesmorestructured, com-pletingthefirstturnofreductionaroundthecore.Atlast, thefinalstagesshowanotherroundofreduction,which producesthesmallestamountofflakesmakingithardto trackapattern.Thisexploitationarrangementcreatesthe finalclassicDiscoidcoreshapewithbifacialexploitation. 3.2. Missingpieces

Themissingflakesarenon-uniformlydistributedacross thereductionsequence:selectionincreasedgraduallyupto theendinrelationtothefullachievementofthetechnical objectives.

Themajormissingartifactsareestimatedtonumber14, derivedespeciallyfromstages1,5,6,9and10. Decorti-cationby-products(stage1)ofthecorefaceAismissing, apartfromthefirstonedetached.Thesemissingartifacts, obtainedundoubtedlyinsitu,arefourcorticalflakeswith naturalorflatbutt;onlyoneofwhichwaslarge(atleast 40×30mm)(Fig.5a).Theseflakesmayhavebeenexploited asacore-on-flakeorasatoolequippedwithasharpedge (18mmlongontheleftside).

Duringstage4,whendecorticationtemporarilystops and thefinishing of some peripheralconvexities starts, someprofitableartifactsweredetachedandselected.We

872 D.Delpiano,M.Peresani/C.R.Palevol16(2017)865–877

Fig.6.3Dviewandsizeofaflake,exposedfromtherightside(a),theimpactpoint(b)andthetop(c).Thisfinecore-edgeremovalflakewithrightbacked

sideoppositetoleftthincuttingedgeislikelytobeconsideredoneofthebestproductsobtainedfromfaceAduringstage9.

Fig.6. Vue3Dettailled’unéclat,exposéàpartirducôtédroit(a),dupointd’impact(b)etdusommet(c).Lefinéclatd’arrachementàlaborduredu

nucleus,aveclecôtéarrièreopposéaubordgauchedelacoupeminceestprobablementàconsidérercommel’undesmeilleursproduitsobtenuàpartir

delafaceApendantl’étape9.

identifiedasemi-corticalcore-edge-removalflakeissued fromfaceB,shortandthickintheproximalzone,although providedwithacuttingedgeonitsrightside.Italsoopened astrikingplatformthatwasintensivelyexploitedshortly after,accordingtotheconcatenationofthetwocorefaces. Instage 5,thefirst fineDiscoid productsaremostly obtained from face A, which after the (unsuccessful) detachmentofapseudo-Levalloispoint,wasdeactivated. KnappingshiftedtofaceB,alreadydecorticated,and pro-ducedafineflakethroughcentripetalpercussion(Fig.5.b). Ithasanasymmetricaltriangularsectionandanovaland elongatedshapepredeterminedfromthedetachmentof lateralflakes.

Stage6 entails a few blows toface A following the detachmentofasomewhatirregularcentripetalflakefrom faceB.Inthisandespeciallythefollowingstages,fine arti-factsweredetachedandselected,makingthevolumetric reconstructiontricky.Thefinestandmosteasilytraceable isacore-edgeremovalflakewithnon-corticalleftbackand rightcuttingedge(Fig.7a).

Stage9 wastargetedtoachievefirstchoiceproducts fromfaceAbymeansofcentripetaldetachments,butalso producedalargenumberoferrors,thenrepaired.However,

anovalflakewastakenforitssuitableshape.Thelast arti-factofthisstageisacore-edge-removalflakeachievedby chordalpercussiononfaceAandthenpickedup.Thisflake isregularand5mmthick,28×17mmlargeandequipped withaconvexleftcutting(30−40◦)edgeatleast25mm long (Fig.6).It certainly representsthemostsuccessful productuptothisstageofthesequence.

Finally,stage10 entailsthelast twodetachmentson faceBbeforethecoreisdepletedbythelastrefitted ele-ment,which wasdiscarded. Thefirstartifact(Fig.7b)is a 35×26mm largecore-edge removal flakewithsharp (45◦)andstraightleftedge.Therightbackisconvexdueto previousdetachments.Thesecondflake(Fig.7c)is cross-orientedtothefirstandoverpassesthecore-edge.Ithasa rightknappedback,andaleftthinandlong(28mm)edge. Forthishighlyfunctionaltrenchant,itwasselected. 3.3. Productivity

Theproductivityrateofthecompletesequenceremains low.Basedessentiallyonthe3Dmorphology,itseemsthat only six orseven gestures mighthave produced usable blanks:four arefinely shapedcore-edgeremoval flakes

D.Delpiano,M.Peresani/C.R.Palevol16(2017)865–877 873

Fig.7.3Dviewand2Dsizeofacore-edgeremovalblowwithleftknappedbackandrightcuttingedgedetachedfromfaceAduringstage6.Itrepresents

oneofthebestproductsachievedandpresumablyused(a);3Dviewandsizeofacore-edgeremovalblowwithsharpleftmarginobtainedfromfaceB

duringstage10(b);3Dviewand2Dsizeofacore-edgeremovalblowwithrightbackopposedtoleftsharpedge,obtainedfromfaceBduringstage10(c).

Fig.7. Vue3Dettaille2Dd’uncoupd’arrachementauborddunucleus,avecunarrièregauchefac¸onnéetunborddecoupedroitdétachédelafaceA

pendantl’étape6.Cecireprésentel’undesmeilleursproduitsachevéetsansdouteutilisé(a);vue3Dettailled’uncoupd’arrachementenborduredu

nucleus,avecunemargegauchetranchante,obtenueàpartirdelafaceBpendantl’étape10(b);vue3Dettaille2Dd’uncoupd’arrachementenbordure

dunucleus,avecunarrièredroitopposéaubordgauchetranchantobtenuàpartirdelafaceBpendantl’étape10(c).

withknappedbacksopposedtosharpandconvexcutting edgesandtwoarecentripetalovalorquadrangularshaped flakeswithsingleordoublethinedge.Finally,athick corti-calcentripetalflakeseemstobetheonlyblanksuitableasa core-on-flakeforthesecondaryreductionsequence. Exper-imentalcomparisonsonDiscoidtechnologytestifiedtoan averageof sevenpseudo-Levallois pointsobtainedfrom each bifacially knappedcore (Bourguignon et al., 2011; Brenetetal.,2009);however,thesetoolsdidnotappearto

havebeenthemainobjectiveofA9IISXLIIsequence:only onepointwasobtainedanddiscardedinsitu.

Comparing the productivity of the entire A9 lithic industry made on Maiolica flint to the refitting exper-iment (Table 1) found that at least 30 products (4cm length+width)wereissuedfromthereductionsequence ofA9SXLII,whilethetechno-economicstructureoftheA9 Maiolicaindustryrecordsan averageof 35 artifactsper coreonblock (thereforeexcluding thecores-on-flakes).

874 D.Delpiano,M.Peresani/C.R.Palevol16(2017)865–877

Table1

Flake-per-coreproductivityrecordedforthewholeA9lithicassemblage

onMaiolicaflintcomparedtothereconstructedreductionsequenceof

A9ISXLII.

Tableau1

Productivitéenéclatparnucleus,pourl’ensembledel’assemblagelithique

A9surleflintMaiolica,comparéeàlachaîneopératoirereconstituéede

A9ISXLII. A9Maiolica assemblage Reconstructed chaîneopératoire Cores(n) 102 1

Totalflakesmod>4cm(n) 3528 30

Flakespercore 35 30

Flakeswithcortex 1704(48%) 21(70%)

Fig.8. DistributionofMaiolicaDiscoidcoressizescomparedtothecore ofstructureA9SXLII(redtriangle).

Fig.8. Distributiondestaillesdenucleusdiscoïdes,comparésaunucleus delastructureA9SXLII(trianglerouge).

Thisdataremainsanalogueevenifweconsiderthe frag-mented,reused,orrecycledflakes(Peresanietal.,2015). TheA9SXLIIreductionsequence,however,displaysahigh rate of corticated products: 70% as compared to about 50%ofthewholelithicassemblage.Thisdataisrelatedto thebifacialvariantofexploitationandtodecisionsbased onknappingdesign that ledthecoretomaintain corti-calportionsuntilitsdiscard.Overall,thefrequencyofthe techno-typologicalcategoriesofA9SXLIIsuggeststhatthis productionis fullycomparable totheA9 lithicindustry (Table2).Inaddition,theA9SXLIIcorehasbeendiscarded atadegreeofreductiononlinewiththecoresfromA9 (Fig.8).

Theonlydiscrepanciesconcernthecentripetalflakes, whicharequiterareinA9SXLII,probablyaconsequence ofmisshapencoreconvexitiesorflakingmistakescreated when theknapper wantedtomaketheseblanks:errors (andreparations)areinfacthigherthantheaverageinA9. Thesameholdsforthecorticalbackedflakes:weconsider that thisdatacouldbeaffectedbythestrongincidence oftheseproductsontheearlystagesofdecorticationof faceB.Asalreadymentioned,thissurfaceinitiallyappears muchflatter,requiringintenseknappingontheperipheral edgeforshapingthecentralconvexity.Asshownbythe evolutionofthecoreshape(Fig.9),theconvexityofface Bdevelopsthroughout thereductionsequence fromthe onsettodeactivation.Inaccordancewiththeconcatenated exploitationofthesurfaces,theneedtoraisetheperipheral edgecanbeascribedtotheopportunitytoexploit non-hierarchicalcorefacesinacoherentlyDiscoidwaybyalso takingadvantageofthevariabilityofthemethod.The pref-erentialexploitationoffaceBmayhavebeendesignedto exploittheblockinamoreflexibleandlessconstrictedway bybifaciallyknappingit.Thistypeofproductionappears thereforedirectlyrelatedtotheapplicabilityandefficiency ofDiscoidmethod.

Inconclusion,productivityfortheDiscoidmethodisnot inherentlylowbutitrequireshightechnological invest-mentaimedtomaximizeflakeproductiononbothfaces. Thecoreismodifiedtoyieldarecurrentseriesoffirstchoice artifacts.Therealityofthismethodhowever,isthatitcan leadtomoremistakesandbadtechnicalchoices, which bringdowntheproductivity.

4. Discussionandconclusion

Therefittingtechniqueismadeheremoreaccurateby theuseofthe3Danalyticalmethodand virtualsupport (Delpianoetal.,2017).Thismethodologicalapproach,used hereforthefirsttimefortacklingquestionsof preserva-tionandhandlingofacomplexmultiplerefitting,turned outtobeasignificantanalyticaltool,tobequeriedand exploited,addingtothetraditionalanalyses.Thismethod addsa highlevels ofconfidence thankstoitsreality of representationandpermitsresearcherstoenterabsolute andprecisemorphometricfeaturesthatwouldbe other-wise inaccessible(cross-sections, volumes)makingitan innovativetoolwithhighpotentialwhenassociatedwith natural-scaleobservations,especiallyincircumstanceslike these,wheremultipleartifactsareinvolved.

Table2

Incidenceofthemorpho-technicalcategoriesoftheA9lithicassemblagecomputedonMaiolicaflintandcomparedtothereconstructedsequence.

Tableau2

Incidencedescatégoriesmorpho-techniquesdel’assemblagelithiqueA9informatiséessurleflintMaiolicaetcomparéesàlachaîneopératoirereconstituée.

A9Maiolicaassemblage Reconstructedchaîneopératoire S.A S.B

Corticalflakes 1437(40.3%) 11(36.7%) 7 4

Corticalbacked 267(7.5%) 6(20.0%) 2 4

Backed(nocortex) 505(14.1%) 4(13.3%) 2 2

Centripetal 464(13.0%) 2(6.7%) 1 1

Errors/repair 357(10.0%) 4(13.3%) 3 1

D.Delpiano,M.Peresani/C.R.Palevol16(2017)865–877 875

Fig.9.Progressiveevolutionofthecoreshape.AgradualincreaseofthecentralconvexityisclearlyevidentforfaceB.

Fig.9. Évolutionprogressivedelaformedunucleus.UneaugmentationgraduelledelaconvexitécentraleesttoutàfaitévidentesurlafaceB.

Therefore, this analysis allowedus tobetter explore theinformativepotentialofmultiplerefittingtechniques, tolearnaboutNeanderthalbehavioraleconomy,knapping skillsandtheoreticalandpracticalconcepts.

Allofthestepsofthereductionsequencefrom initial-izationuntildiscardtookplaceinminutesonsite,possibly inthezonewherestructureA9SXLIIhasbeenunearthed. Thistypeofeconomicbehaviorfitswithdatacollectedfrom thetechno-economicanalysisofthelocalknappablerocks exploited, especially the Cretaceous flintfrom Maiolica limestones,whichwasnotsubjectedtoanyfragmentation ofthereductionsequence(Delpiano,2014).

It should alsobe emphasized that therefittingdoes notentailartifactscollectedinthesurroundingof struc-tureA9IISXLII;furthermore,thestructurecontainsequally large products and debris. Given this spatially limited scatter,itcannotbeexcludedthatthecobblewasknapped onaskinthencleanedandfreedofun-usefulflakesinplace. Furthermore,theelevateddensityofartifactsinthiszone ofthecavecouldbeconnectedtoapossiblegarbagezone, inproximityofthefireplacesandofotherknappingzones undertherockshelter(Fig.1).

Further,wehavedeterminedthattheknapper’s techni-calcriteriaandthereductionconceptsarefullycompatible withDiscoid technology: thearrangement ofthe knap-ping operationsbased ontwoopposed, convexand not hierarchiccorefacesis setupalreadyaftertheir decor-tications. These surfaces, moreover, are separated by a peripheraledgethatshowsaconvexityalongwhichthe coreisexploited,throughaturningandcompletemodality, withsecantandsteepeddetachments.

Thesetechnical issuesreflect themainDiscoid oper-ational chainrecognized in theA9 lithic assemblage in a previous,pioneerstudy(Peresani,1998).TheA9SXLII reductionsequenceis,indeed,aconfirmationtothissense andpointsoutthereliabilityofthetechnological analy-sisbasedonmentalrefitting,ausefultoolforincreasing awarenessofthemethod’srules,herefollowedinarigid, “manual”way.However,givenitsuniqueness,theA9SXLII sequencedoesnotrevealtheamplevariabilityenvisaged onseverallevelsacrossthistechnologicalprocedure.The ramificationoftheproductionintwojuxtaposed opera-tionalchains,forexample,isnotdocumentedherebutis

certainlypresentinA9unit;onthecontrary,thenotable refitsfromtheFrenchsiteofLesFieuxrecordtheflexibility oftheDiscoidmethodinwhichtheobjectives,represented bycore-edge-removalflakesandpseudo-Levalloispoints, remainalmostthesame(Faivre,2011;Turqetal.,2013).In ourcase,however,thepossibilitythatsomecorticalflakes (weassumedone)wereexploitedforthesecondary reduc-tionsequence cannotbeexcluded.Flexibility inDiscoid knappingmayalsoleadthecoretomaintaintheoriginal shapeofthecobble,whereasymmetricconvexitiesmake thecorecomparabletoaLevalloisvolumeexploitedbya preferentialorcentripetalpattern.ThisisthecaseatAbric Romaní,layerJ(Carbonnel(Ed.),2012),butithasnotbeen observedatFumane.

Knapping at structure A9SXLIIwas also affected by careless technical gestures that are at odds with clear technicalknow-how. Thevirtualreconstructionallowed ustounravelanevident behavior:theknapperwanted to adapt the cobble morphology for technological pur-posesaimedat diversifyingtheproduction, probablyin order tomaximizeknappingand make it more flexible andversatile.Theseactionsarereflectedinthespecialized exploitation(mostlychordal)ofthefaceBthatresultsin anincreasedcentralconvexity,shapingthediscoidalcore. Littleattentionispaidtothegestures thatseemtypical oflessexperienced individuals,but insteadtheknapper seemsfullyawareoftheDiscoidconceptdesignand plan-ningdepth,soindicativeoftheworkofa“master.”Thence, thewholesequencemaybeanexampleofcultural trans-mission.Know-howistransmittedthroughapedagogical behaviorin asociety thatusesquitecomplex technolo-giestodesigntool.Discoidtechnology,initsbasiccriteria, remainedunchangedoverlongperiodsandgreatdistances. Itisunlikelythattheknow-howwastransmittedonlyby emulation,imitationorusingso-calledprocedural mem-ory,wherealackofcomprehensionofthegesturesquickly gave rise to spatiotemporal changes, but it is farmore likelythatarealteachingandlearningsystemcouldexist (TehraniandRiede,2008).However,inthewholeMiddle Palaeolithicthereisanabsenceofspatialknapping clus-tersinthearchaeologicalrecordthatmightsuggestthat teacherswereinvolved.Inthiscase,thisargumentis sup-portedonlybythecontrastbetweentheoreticalknowledge

876 D.Delpiano,M.Peresani/C.R.Palevol16(2017)865–877

andknowledgeputintopractice.Actually,weknowthat theeconomicobjectiveswereatleastpartiallyachieved, thankstotheproductionandprobableutilizationoffour core-edge-removalflakesandtwocentripetalflakes. Com-paringtotheresultsofanexperimentalstudydesignedto quantifytheDiscoidproductivityonthebaseofthe knap-per’sexpertise(Brenetetal.,2013),weobservedthatour exampleishalfwaybetweenskilledandlowexperienced individuals.Inaddition,inthisparticularcase,the educa-tionalpurposeofaknappingproductmade,finished,and discardedin situ(also withexcellentknappablestones) appearsmuchhigherthanthesupposedeconomicpurpose, weaklydocumented(Pigeot,1990);anotherpointinfavor oftheteacher/learnerhypothesis.

Refittings like that one achieved from this specific context confirm once again their utility in providing dataconcernedwithdifferentfield ofinvestigation, cul-tural,behavioral,taphonomicandmethodological.Widely knowntobetime-consuming,thispracticeshouldbemore implemented byusing 3D imaging technologyin order to facilitate the search of virtual refits and large-scale connectionsalsoofmaterialsdifferentthanstoneinthe archaeologicalrecords.

Acknowledgments

Research at Fumane is coordinated by the Fer-rara University in the framework of a project sup-portedbytheMinistryofCulture−VenetoArchaeological Superintendency, public institutions(Lessinia Mountain Community−RegionalNaturalPark,FumaneMunicipality) and private associations and companies. The Breuck-mann SmartScan 3D used for this work is based at theNeanderthal Museum in Mettmann (Germany).The authorsthankKristenHeasleyforthetranslationandJamie HodgkinsfortherevisionoftheEnglishtextandtwo anony-mousreviewersforprovidingcontributiontoconsiderably amelioratingthemanuscript.

References

Bamforth, D.B., Bleed,P., 1997. Technology flaked stone technology

andrisk.In:Barton,C.M.,Clark,G.A.(Eds.),RediscoveringDarwin: evolutionarytheoryandarchaeologicalexplanation.Archaeological Papers.AmericanArchaeologicalAssociation,WashingtonD.C.,USA, pp.109–139.

Benazzi,S.,Bailey,S.E.,Peresani,M.,Mannino,M.,Romandini,M.,Richards,

M.P., Hublin, J.J., 2014. Middle Paleolithic and Uluzzian human

remainsfromFumaneCave,Italy.J.Hum.Evol.70,61–68.

Boëda,E.,1993.LedébitagediscoïdeetledébitageLevalloisrécurrent

centripète.Bull.Soc.Prehist.Fr.90,392–404.

Boëda,E.,2013.Techno-logique&Technologie.Unepaléo-histoiredes

objetslithiquestranchants.@rchéo-éditions.com,Paris.

Bourguignon,L.,Brenet,M.,Folgado,M.,Ortega,I.,2011.Aproximación

tecno-económicadeldebitagediscoidedepuntaspseudo-Levallois: elaportedelaexperimentación.In:2ndCongresoInternacionalde arqueologiaexperimental,pp.53–59.

Brenet,M.,Bourguignon,L.,Folgado,M.,Ortega,I.,2009.Élaboration

d’unprotocoled’expérimentationlithiquepourlacompréhensiondes comportementstechniquesettechno-économiquesauPaléolithique moyen.Nouv.Archeol.118,60–64.

Brenet,M.,Folgado,M.,Bourguignon,L.,2013.Approche

expérimen-taledelavariabilitédesindustriesduPaléolithiquemoyen.L’intérêt d’évaluerles niveauxde compétences desexpérimentateurs. In: Palomo,A.,Piqué,R.,Terradas,X.(Eds.),In:Experimentaciónen arque-ologi,SèriemonogràphicadelMAC.Estudioydifusióndelpasado Girona,pp.177–182.

Bretzke,K.,Conard,N.J.,2012.Theevaluationofmorphologicalvariability

inlithicassemblagesusing3Dmodelsofstoneartifacts.J.Archaeol. Sci.39,3741–3749.

Breuckmann,B.,AriasCabal,P.,Mélard,N.,Onta ˜nónPeredo,R.,Pastoors,

A.,TeiraMayolini,L.C.,FernandezVega,P.A.,Weniger,G.C.,2009.

Surfacescanning−NewPerspectivesforArchaeologicalData Manage-mentandMethodology?In:Frischer,B.,WebbCrawford,J.,Koller,D. (Eds.),MakingHistoryInteractive.ComputerApplicationsand Quan-titativeMethodsinArchaeology(CAA).Archaeopress,Oxford,UK,pp. 42–47.

Broglio,A.,Tagliacozzo,A.,DeStefani,M.,Gurioli,F.,Facciolo,A.,2006.

Aurignaciandwellingstructureshuntingstrategiesandseasonality intheFumaneCave(LessiniMountains).In:Kostenki&TheEarly UpperPalaeolithicofEurasia:generaltrends,localdevelopments. StateArchaeologicalMuseum-reserve“Kostenki”,pp.263–268.

Carbonnel,E.,2012.HighresolutionarchaeologyandNeanderthal

behav-ior.In:TimeandspaceinLevelJofAbricRomaní(Capellades,Spain). VertebratePaleobiologyandPaleoanthropology.SpringerEd(407 pp.).

Clarkson,C.,Hiscock,P.,2011.Estimatingoriginalflakemassfrom3D

scansofplatformarea.J.Archaeol.Sci.38,1062–1068.

Cziela,E.,Eickhoff,S.,Arts,N.,Winter,D.(Eds.),1990.Thebigpuzzle.

Inter-nationalsymposiumonrefittingstoneartefacts.Studiesinmodern Archaeology,1,Bonn,Holos.,pp.9–44.

Delagnes,A.,Ropars,A.(Eds.),1996.PaleolithiquemoyenenPaysdeCaux

(Haute-Normandie):lePucheuil,Etoutteville,deuxgisementsde pleinairenmilieulœssique.Maisondessciencesdel’homme(D.A.F. 56).

Delagnes,A.,Rendu,W.,2011.ShiftsinNeandertals’mobility:

Mouste-riantechnologicalandsubsistencestrategiesinWesternFrance.J. Archaeol.Sci.38,1771–1783.

Delpiano,D.,2014.Cateneoperativeefrazionamenti.Risultatidauno

studiotecno-economicodell’industriaDiscoidediGrottadiFumane. MasterDissertationinQuaternary,PrehistoryandArchaeology.

Delpiano,D.,Peresani,M.,Pastoors,A.,2017.Thecontributionof3Dvisual

technologytothestudyofPalaeolithicknappedstonesbasedon refit-ting.Digit.Appl.ArchaeolyCultur.Herit.4,28–38.

Deschamps,M.,Clark,A.-E.,Claud,É.,Colonge,D.,Hernandez,M.,

Nor-mand,C.,2016.Approchetechnoéconomiqueetfonctionnelledes

occupations de plein-air du Paléolithique moyen récent autour deBayonne(Pyrénées-Atlantiques).Bull.Soc.Prehist.Fr.113 (4), 659–689.

Faivre,J.-P.,2011.Organisationtechno-économiquedessystèmesde

pro-ductiondanslePaléolithiquemoyenrécentduNord-Estaquitain.BAR InternationalSeries2280,Oxford,UK.

Fiore,I.,Gala,M.,Romandini,M.,Cocca,E.,Tagliacozzo,A.,Peresani,M.,

2016.Fromfeatherstofood:reconstructingthecompleteexploitation

ofavifaunalresourcesbyNeanderthalsattheGrottadiFumane,unit A9.Quatern.Int.421,134–153.

Gartski, K., 2016. Virtual representation: the productionof 3D

dig-ital artifacts. J. Archaeol. Method Theory, http://dx.doi.org/10.

1007/s10816-016-9285-z.

Gouëdo,J.M.,1990.LestechnologieslithiquesduChâtelperroniende

lacouche Xdela grottedurenned’Arcy-sur-Cure.In:Farizy,C. (Ed.),PaléolithiquemoyenrécentetPaléolithiquesupérieurancien enEurope.Mémoiresdumuséedepréhistoired’Île-de-France3.,pp. 305–308.

Higham,T.F.G.,Brock,F.,Peresani,M.,Broglio,A.,Wood,R.,Douka,K.,2009.

ProblemswithradiocarbondatingtheMiddleandUpperPalaeolithic transitioninItaly.Quat.Sci.Rev.28,1257–1267.

Inizan,M.-L.,Reduron-Ballinger,M.,Roche,H.,Tixier,J.,1999.

Technol-ogyandterminologyofknappedstone,Préhistoriedelapierretaillée, tome5.Crep,Nanterre.

Lin,S.C.,Douglass,M.J.,Holdaway,S.J.,Floyd,B.,2010.Theapplication

of3Dlaserscanningtechnologytotheassessmentofordinaland mechanicalcortexquantificationinlithicanalysis.J.Archaeol.Sci.37 (4),694–702.

Locht,J.-L.,Swinnen,C.,1994.Ledébitagediscoïdedugisementde

Beau-vais(Oise):aspectsdelachaîneopératoireautraversdequelques remontages.Paleo6,89–104.

López-García, J.M.,Dalla Valle,C.,Cremaschi,M.,Peresani, M.,2015.

ReconstructionoftheNeanderthalandModernHumanlandscapeand climatefromtheFumanecavesequence(Verona,Italy)using small-mammalassemblages.Quat.Sci.Rev.128,1–13.

Nelson,M.C.,1991.Thestudyoftechnologicalorganization.Archaeol.

MethodTheory3,57–100.

Obradovi ´c,M.,AbuZeid,N.,Bignardi,S.,Bolognesi,M.,Russo,P.,Peresani,

M.,Santarato,G.,2015.Highresolutiongeophysicalandtopographical

D.Delpiano,M.Peresani/C.R.Palevol16(2017)865–877 877

NearSurfaceGeoscience.In:21stEuropeanMeetingofEnvironmental andEngineeringGeophysics,pp.59–63.

Odell,G.H.,2001.StonetoolresearchattheendoftheMillennium:

clas-sification,functionandbehaviour.J.Archaeol.Res.9(1),45–100.

Pastoors,A.,Cantalejo,P.,2014.Aplicacionesconescáneralosgrabados

prehistóricos.In:Ramos,J.,etal.(Eds.),CuevadeArdales. Interven-cionesarqueológicas2011−2014.EdicionesPinsapar,Benaoján,pp. 115–118.

Pastoors,A.,Weniger,G.-C.,2011.Closerangesensingforgenerating3D

objectsinprehistoricarchaeology.In:Lenz-Wiedemann,V.,Bareth, G.(Eds.),ProceedingsoftheISPRSWGVII/5Workshop,Cologne.,pp. 103–106.

Peresani,M.,1998.Lavariabilitédudébitagediscoïdedanslagrottede

Fumane(ItalieduNord).Paleo10,123–146.

Peresani,M.(Ed.),2003.DiscoidLithicTechnology.Advancesand

Impli-cations.BritishArchaeologicalReports,InternationalSeries,1120.

Peresani,M.,2012.Fiftythousandyearsofflintknappingandtool

shap-ingacrosstheMousterianandUluzziansequenceofFumanecave. Quatern.Int.247,125–150.

Peresani,M.,Boldrin,M.,Pasetti,P.,2015.Assessingtheexploitationof

doublepatinatedartifactsduringtheLateMousterian.Implications forlithiceconomyandhumanmobilityintheNorthofItaly.Quatern. Int.361,238–250.

Peresani,M.,Cristiani,E.,Romandini,M.,2016.TheUluzziantechnology

oftheGrottadiFumaneanditsimplicationforreconstructing cul-turaldynamicsintheMiddle–UpperPalaeolithictransitionofWestern Eurasia.J.Hum.Evol.91,36–56.

Peresani,M.,Cremaschi,M.,Ferraro,F.,Falguères,C.H.,Bahain,J.J.,

Gruppi-oni,G.,Sibilia,E.,Quarta,G.,Calcagnile,L.,Dolo,J.M.,2008.Ageofthe

finalMiddlePalaeolithicandUluzzianlevelsatFumaneCave,northern Italy,using14C,ESR,234U/230Thandthermoluminescencemethods.

J.Archaeol.Sci.35,2986–2996.

Peresani,M.,Fiore,I.,Gala,M.,Romandini,M.,Tagliacozzo,A.,2011.Late

Neandertalsandtheintentionalremovaloffeathersasevidencedfrom birdbonetaphonomyatFumanecave44kyBP,Italy.Proc.Natl.Acade. Sci108,3888–3893.

Pigeot,N.,1990.Technicalandsocialactors:flintknappingspecialists

andapprenticesatMagdalenianEtiolles.ArchaeologicalReviewfrom Cambridge9.

Richardson,E.,Grosman,L.,Smilansky,U.,Werman,M.,2013.

Extract-ingScarandRidgeFeaturesfrom3D-scannedLithicArtifacts.In: Earl,G.,Sly,T.,Chrysanthi,A.,Murrieta-Flores,P.,Papadopoulos,C., Romanowska,I.,Wheatley,D.(Eds.),ArchaeologyintheDigitalEra. Papersfromthe40thAnnualConferenceofComputerApplications andQuantitativeMethodsinArchaeology(CAA).Amsterdam Univer-sityPress,pp.83–92.

Roebroeks,W.,1988.FromfindscatterstoearlyHominidbehaviour.

AstudyofMiddlePalaeolithicriversidesettlementsat Maastricht-Belvédère(TheNetherlands).LeidenUniversityPress,Leiden,The Netherlands.

Romandini,M.,Fiore,I.,Gala,M.,Cestari,M.,Tagliacozzo,A.,Guida,G.,

Peresani,M.,2016.Neanderthalscrapingandmanualhandlingof

vul-turewingbones:evidencefromFumanecave.Experimentalactivities andcomparison.Quatern.Int.421,154–172.

Romandini,M.,Nannini,N.,Tagliacozzo,A.,Peresani,M.,2014.The

ungu-lateassemblagefromlayerA9 attheGrottadiFumane,Italy:a zooarchaeologicalcontributiontothereconstructionofNeanderthal ecology.Quatern.Int.337,11–27.

Skar,B.,Coulson,S.,1986.Evidenceofbehaviourfromrefitting–acase

study.Norweg.Archaeol.Rev.19(2),90–102.

Slizewski,A.,Semal,P.,2009.ExperienceswithlowandhighCost3D

SurfaceScanners.Quartar56,131–138.

Tehrani,J.J.,Riede,F.,2008.Towardsanarchaeologyofpedagogy:learning,

teachingandthegenerationofmaterialculturetraditions.In:World Archaeology40.

Turq,A.,Roebroeks,W.,Bourgouignon,L.,Faivre,J.-P.,2013.The

frag-mentedcharacterofMiddlePaleolithicstonetooltechnology.J.Hum. Evol.65(5),641–655.

Tusa,S.,DiMaida,G.,Pastoors,A.,Piezonka,H.,Weniger,G.-C.,Terberger,

T.,2013.ThetheGrottadiCaladeiGenovesi–NewstudiesontheIce

AgecaveartonSicily.Praehist.Z.88(1−2),1–22.

Vaquero,M.,Chacón,G.,Rando,J.M.,2007.Theinterpretivepotentialof

lithicrefitsinamiddlepaleolithicsite:theabricRomaní(Capellades, Spain).In:Schurmans,U.,DeBie,M.(Eds.),FittingRocks.Lithic Refit-tingExamined,BritishArchaeologicalReportNo.1596.Oxford,UK.