EXPRESSIO

Linguistic perspectives on ageing issues,

ethics and ideology

Edited by Alessandra Vicentini & Kim Grego

Tutti i contributi inviati alla rivista sono sottoposti a una procedura di double blind peer

review che ne garantisce la validità scientifica.

ISSN 2532-439X

MIMESIS EDIZIONI (Milano – Udine) www.mimesisedizioni.it

[email protected] Isbn: 9788857568232

© 2019 – MIM EDIZIONI SRL Via Monfalcone, 17/19 – 20099 Sesto San Giovanni (MI) Phone: +39 02 24861657 / 244163

Autorizzazione del Tribunale di Varese n. 1 del 2016

Direttore Giulio M. Facchetti Vicedirettori

Gianmarco Gaspari, Alessandra Vicentini Comitato Editoriale

Barbara Berti, Paola Biavaschi, Kim Grego, Jean Hadas-Lebel, Mario Iodice, Roberta Melazzo, Marta Muscariello, Paolo Nitti, Erika Notti, Federico A. Pasquaré Mariotto, Giulia Rovelli, Daniel Russo, Raffaele Zago

Comitato Scientifico

Luciano Agostiniani (Università degli Studi di Perugia) Lucia Bertolini (Università degli Studi eCampus) Gabriella Cartago (Università degli Studi di Milano) Carlo Consani (Università degli Studi di Chieti-Pescara) Pierluigi Cuzzolin (Università degli Studi di Bergamo) Javier de Hoz Bravo (Universidad Complutense de Madrid) Pierangela Diadori (Università per Stranieri di Siena) Roberta Facchinetti (Università degli Studi di Verona) Fabiana Fusco (Università degli Studi di Udine) Giovanni Iamartino (Università degli Studi di Milano) Mario Negri (Università IULM di Milano) Vincenzo Orioles (Università degli Studi di Udine) Diego Poli (Università degli Studi di Macerata) Rosa Pugliese (Università Alma Mater Bologna) Giovanna Rocca (Università IULM di Milano) Francesca Savoia (University of Pittsburg) Graziano Serragiotto (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) Marco Sonzogni (Victoria University of Wellington, NZ) Giuseppe Stellardi (St Hugh's College, Oxford)

Questo volume è stato pubblicato grazie al supporto finanziario di Fondazione Cariplo, Progetto di ricerca “Age.Vol.A. – Ageing, Volunteers, Assistants. Multilingual tools for assisting the ageing / A.Ge.Vol.A. – Assistenza, GEstione, VOLontariato, Anziani. Strumenti multilingui per l’assistenza agli anziani”, finanziato per il triennio (2018-2021) nell’ambito del Bando “Ricerca sociale sull’invecchiamento: persone, luoghi e relazioni” (Rif. 2017-0950). Coord. scientifico: Prof. A. Vicentini, Università degli Studi dell’Insubria; coordin. partner: Prof. K. Grego, Università degli Studi di Milano

Alessandra Vicentini (University of Insubria) Kim Grego (University of Milan)

Ageing issues, ethics and ideology: discursive

representations in the media and in the professions 5

Giulia Rovelli (University of Insubria)

Changing terminology and discourse in the representation of older people in the UK and US lay press 21

Laura Tommaso (University of Molise)

“Enjoying life to the full”: a discourse analysis of senior travel insurance TV adverts 47

Barbara Berti (University of Milan)

Ageing in the digital era: couchsurfing for the elderly. An NLP perspective 69

Stefania M. Maci (University of Bergamo)

“We’re three old guys.” Ageist discourse in Hollywood movies – a case study 91

Marianna L. Zummo (University of Palermo)

Seniors’ social image: the representation of ageing

in electoral campaigns 115

Annalisa Zanola (University of Brescia)

Elderly patients facing Informed Consent: when

Abstract

Many in the tourism industry have begun to realize the significance of the seniors travel market and have started to rethink their marketing strategies with the aim of sharpening their focus on this complex and multifaceted segment. This study investigates how creative strategies and advertising disclosures utilized by UK travel insurance providers have changed in response to this demographic scenario and ‘active ageing’ rhetoric. In seeking to investigate the dominant constructions of mature travellers circulating in British insurance advertising communication, the paper aims to analyze the linguistic and discourse strategies adopted in the insurance firm Avanti campaigns by employing Discourse Analysis as its main approach in a longitudinal perspective. To place the multimodal advertising samples presented throughout this article in their context, an overview of financial services advertising is also provided. After building a case for the uniqueness of financial advertising, a comprehensive literature review of the studies related to the representation of older people in this specific sector will be given. The methodology adopted as well as the selection of data will also be described. The findings, then, will be discussed in the light of the relevant literature. Finally, conclusions will be presented along with guidelines for possible future research. Overall, the contribution offers a linguistic lens for understanding ageing in the context of British consumerism and may be a useful reading for students and scholars of financial services marketing, policy makers and practitioners.

Keywords: ageing studies, longitudinal discourse analysis, financial services advertising, tourism studies.

1. Introduction

In an irreverent campaign promoted by the Argentina Tour-ism Office, the country’s beautiful landscapes have an explo-sive effect on mature tourists. The 2017 commercial “5 Places You Should Visit if You Wanna Shout,” follows an old couple as they fish, windsurf, dirt bike, and more, all while screaming at their excitement with various expletives that are bleeped out: “F..k, it’s good to be alive!”1. This is just one example from

a string of recent ads from all over the world in which older adults have taken a prominent role. Their representations frame issues and group identity differently from the traditional para-digm of old age, with its focus on ill health, functional decline and poverty, towards a more positive view of old age as a natu-ral component of the life span. This trend is apparent in finan-cial service advertising too. A look at current advertising efforts by much of the insurance industry shows that old age is being portrayed as a period of life when one is freed from a number of structured social roles, for example, employment and the care of dependent children, and can explore areas and activities which can provide personal fulfilment. While many questions arise as to the exact interpretation of this scenario which is rather too conveniently presented as an utopia of health, wealth and vitality for all (Blackburn 2002), it seems certain that the British insurance industry, comforted by statistics about UK’s growing and ‘gracefully’ ageing population, has recognized the market potential of older people and has tended to focus on developing competitive business and marketing strategies to target the senior segment. This marketing orientation may actually signal an emerging trend distinctly at odds with the conventional, financial sector policy thinking. Insurance firms

1 “Argentina Tourism 5 PLACES”. Retrieved March 03, 2018, from https://

had generally refused, covered or penalised holiday makers by doubling premiums when they reach 75 – more if they had a pre-existing medical condition (Henderson 2007; Hyde 2015: 338)2. The higher coverage rates for older individual were

sure-ly an issue for the travel industry because of its attempt to dis-seminate the ‘positive ageing’ ideology while at the same time neglecting the physiological changes that may accompany old age (Ylänne-McEwen 2000).

Building on these preliminary considerations, the purpose of this article is to analyse how ‘silver travel’ and ageing are represented in two texts pertaining to the genre of British travel insurance TV commercials. To better understand the evolv-ing representation of later life in British financial discourse, a longitudinal analysis has been conducted drawing on two TV commercials by Avanti – one of the leading firms in the Brit-ish financial sector – broadcasted in the years 2010-2015 and 2016-2018 respectively. In addition, this study aims to inves-tigate what verbal and non-verbal resources are adopted to en-code and persuade the target consumer in the chosen instances. Although older people’s actual thoughts, behaviours, and purchasing patterns are on many occasions far removed from their discursive representations, the predominant mainstream constructions of the new elderly (van Dyk & Lessenich 2009) are worthy of careful examination and critique in order to sect their underlying ideologies. Fairclough’s work on dis-course practices (1992, 1995, 1998) emphasizes the ways in which changes in language use are linked to wider social and cultural processes. In this respect, travel insurance advertising texts can be conceptualised as ‘sites of struggle’ where the ac-tual audience may be ‘hailed’ into a certain subject position which they can accept, reject, or otherwise respond to. In par-ticular, drawing on previous studies (Ylänne-McEwen 2000; Coupland & Gwyn 2003; Chen & Ylänne 2012; Chen 2016; Nartey & Huang 2018), the present article ultimately aims at

2 See also Laura Howard, “Why there’s a long way to go before elderly get

fairer travel insurance”, The Guardian, May 17, 2009. Retrieved from https:// www.theguardian.com/money/2009/may/17/ageing-britain-travel-insurance.

monitoring the direction of changes taking place in the insur-ance advertising field by employing Discourse Analysis as its main approach (Fairclough 1992, 2001, 2003). The employ-ment of this framework could also be used as a tool for un-veiling the embedded social and cultural attitudes, taken for granted but not explicitly expressed in the advertisements con-structing or representing later life. To place the instances cho-sen in the current study in their context so as to explain how they align with or depart from what is taken to be normative for the genre, an overview of financial services advertising dis-course is provided with specific attention to its macro structure and contextual aspects. After building a case for the uniqueness of financial advertising, the theoretical and methodological framework adopted as well as the data employed will be de-scribed. The findings, then, will be discussed in the light of the relevant literature. Finally, the conclusions will be presented along with some guidelines for possible future research. 2. Insurance advertisements: from serious to light-hearted

messages?

Financial services are important to people in a variety of ways, ranging from simple saving, payments and transfer fa-cilities to credit and insurance opportunities. Despite this fact, the challenges that financial services firms face when trying to engage clients are particularly acute. To the average current and potential customer, financial services are complex, dull, unwanted and expensive purchases (Robson & Pitt 2014). Consumer involvement with the benefits of an insurance poli-cy, the rates of return on an investment product, or the checking account services provided at a commercial bank rarely cause a great deal of excitement and enthusiasm. As a result, financial services are usually not associated with high levels of consumer involvement, excitement, symbolism, or emotions and may not always be communicated to consumers in ways similar to how consumer goods are advertised. This, in large part, is due to the nature of service industries themselves or as a result of the spe-cific traits of the product (Cowell 1984; Kirk 1994). In order

to better understand the characteristics of financial service ad-vertising, a general point about the conceptual distinctiveness of services (more generally) from manufactured goods has to be made. The literature describes that the four defining fea-tures of services are intangibility (they cannot be seen, touched or smelled); inseparability (most services are produced, sold and consumed at the same time); heterogeneity (they are never exactly the same from one encounter to the next); and

perish-ability (they cannot be stored) (Cowell 1984).

Marketing of any service is harder than marketing a tangi-ble product, but addressing and overcoming these marketing barriers become even more daunting if the commodity to be promoted is an insurance cover. The challenge is not only how to present abstract products visually through the use of physi-cal cues and tangible evidence. Like all advertisers, financial services companies must comply with general advertising guidelines prohibiting advertising that is untruthful, decep-tive, or unfair. In this regard, the practice of insurance service advertising is further complicated by the massive number of regulations that restrict the content of advertisements, and the number of regulatory agencies that closely monitor and influ-ence ad content. Consequently, elaborate and complex sets of criteria need to be met in order to attain regulatory compliance. This restricts the advertiser’s creative process, and makes in-surances particularly difficult to explain and understand (Doyle

et al. 2009). To exacerbate matters, these products constantly

remind customers of mortality risks and that misfortunes could happen unpredictably to anyone, anywhere. Similarly to other taboo-related goods, such as death-care services or feminine care products, insurance services have been generally consid-ered serious and ill-suited for humour usage (Gulas & Wein-berger 2006: 73).

Due to the fact that insurance is seen as a confusing, face-less, unattractive business and as dealing with remote, un-welcome and dire circumstances that consumers prefer not to think about, “the traditional industry answer is that it should be ‘pushed’ to buyers, rather than being ‘pulled’ by them. Thus, sales channels and techniques tend to be seen as more impor-tant and are better developed in insurance than elsewhere”

(Doyle et al. 2009). As a result, advertising is particularly important to insurance services firms and requires the formu-lation of hybrid informational/promotional messages (Solly 2007) to stimulate demand and to excite the viewer about the useful aspects of the product. Insurance advertising messages commonly rely on emotional (positive emotions associated with the use of the product or the negative side of not using the product) and moral appeals (sense or right and wrong) rather than rational appeals (product benefits). Rational appeals, in-stead, are favoured at the point of sale either through detailed product information or through sales presentations (Wright & Watkins 2010: 119). With the intent of creating an emo-tional response and also a cognitive awareness of a problem, it is not surprising that traditionally the emotion most often appealed to in insurance advertising is fear: the worries and insecurities of individuals and their families being exposed to the uncertainties of life and of the life course (O’Shaughnessy & O’Shaughnessy 2002). Insurance advertising has also fore-grounded consumers’ sense of personal responsibility and ap-peals to their feeling of guilt – “You wouldn’t want to leave your loved ones with added financial worry at a difficult and emotional time.” In this perspective, persuasive appeals can be made on the basis of the inconsistency between professed feelings and beliefs leading consumers to embrace their sense of obligation to others that is respected in the broader soci-ety. Thus, advertising for insurance may remind its audiences that “they feel deeply about their loved ones yet have not pro-vided for them in the event of their death” (O’Shaughnessy & O’Shaughnessy 2002: 150).

From this introductory investigation of insurance adver-tising consistent discourse context, it becomes apparent that commercials in this field have traditionally followed widely accepted and customary brand building formulas. Insurance, the vast majority of the ads seemed to say, was a solemn, seri-ous business. There were ads featuring happy families, with a voice-over offering reassurance that all would remain well for those who chose the right coverage. There were ads with images of fires, floods, tornadoes, burglaries and car crashes, stark reminders of how unexpectedly and fatally things could

end up. There were cautionary tales of parents who died un-insured, leaving their children in the lurch or pensioners with one foot in the grave looking for ‘peace of mind’. Then there were the testimonials from satisfied customers or well-known celebrities, and monologues from insurance agents about their devotion to duty. Due to these factors, the financial industry has been perceived as conservative, old-fashioned, and somewhat tedious. These days, however, many financial advertisements are increasingly using alternative communicative devices pre-sumably to attract attention, increase comprehension, effect source credibility, and enhance liking (Fugate 1998; Fatt & Poon 2002). What appears to be an internationally widespread trend in insurance advertising is the employment of humour and irreverence (Doyle et al. 2009).

3. Theoretical and methodological framework

A TV commercial is self-evidently a composite artefact in which multiple semiotic resources or modes such as language, images, colours, action, music and sound (O’Halloran 2011:1) interact to construct meaning. Based on this view of TV commercials as unitary multimodal discursive products, both verbal and non-verbal elements of two Avanti TV commercials were analysed, drawing theoretical and methodological insights from discourse analysis (Fairclough 1992, 2001, 2003), multimodal discourse analysis (Kress & Van Leeuwen 1996) and genre analysis (Cook 2001). Particular attention has been devoted to how the viewers have been addressed and positioned and to the linguistic devices, stylistic means, presentation and organization of the commercials. The study has been conducted from a longitudinal perspective and with an eye to interpreting the chosen texts in the frameworks of shifting advertising styles. Due to the relatively small case sample, the present contribution certainly cannot claim to constitute a comprehensive investigation of the senior travel insurance TV advertising. However, Avanti as an award winning company, specialising in travel insurance for the over 50’s, would prove to be a valuable case study within the chosen context.

4. Data

In the UK a growing number of insurance firms such as

Avanti, SunLife, OK Travel Insurance, Jet2Insurance, Free Spirit, Explorer Travel Insurance, Able2Travel, Irish Life, Stay-sure, Swinton, Insure for All, GoodToGoInsurance, Cigna and AllClear Insurance, is now prepared to provide travel cover for

older adults – including those with pre-existing medical con-ditions. These specialist insurance providers (claim to) have products that meet older consumers’ needs, and have common-ly used incentives or celebrities in their adverts.

The data for the present study consist of two Avanti com-mercials, which were broadcast on UK television from 2010 to 2018. The reason for choosing Avanti’s commercials as a case study is that they represent a good example of the ‘semiotically-charged’ nature of contemporary advertising whereby the indus-try strives to re-adapt, change and transform rhetorical styles and manners to comply with the complexity of contemporary media and consumer environments, as well as fast-changing older con-sumer awareness and sensibilities. Established in 2010, Avanti

Travel Insurance is a UK travel insurance provider specialized

in travel covers for seniors. As it will become clearer in the fol-lowing analysis of both commercials, in the years 2010-2015 the company relied on a more traditional informative format to as-sist prospective customers with their decision-making process. Conversely, on January 2nd 2016 the company launched a new,

more technically advanced and entertaining TV campaign fea-turing popular nightclub owner Peter Stringfellow. Stringfellow, who passed away on 7 June 2018 at the age of 77, was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2008 which as he revealed in an interview, combined with his age, led to a ramping up in the cost of his travel insurance3. The inspection of contextual information

re-vealed that the Avanti campaign featuring the popular

entrepre-3 Toby Walne, 16 January 2016, “I may be 75... but I still want to travel: Why

nightclub boss Peter Stringfellow is helping older people to find holiday insur-ance”, The Mail on Sunday, retrieved November 8, 2019 from https://www. thisismoney.co.uk/money/experts/article-3402633/I-75-want-travel-nightclub-boss-Peter-Stringfellow-helping-older-people-holiday-insurance.html.

neur was specifically designed to stress a different approach to the brand and was intended to represent a new notion of ageing and later life. As Glen Smith, former Avanti CEO, claimed “[...] We want to make Avanti the first choice travel insurance for our target audience. We don’t just provide insurance for the over 50’s and people with pre-existing medical conditions, we make holi-days happen […] we’re ‘The Holiday Makers’ rather than just another insurance company. We don’t see age as an obstacle, we see it as an opportunity!”4. According to the company’s website,

Stringfellow was chosen as testimonial because “He is a posi-tive and down-to-earth individual who has the spirit and attitude with which Avanti want to be associated as a company. He is an older gentleman (looking good at 76!) who keeps active, is constantly travelling and very much young at heart”5. Since

Au-gust 2019 Avanti has launched its new rebrand, which includes a revamped website and brand identity. The change encapsulates the brand’s commitment to personalized travel insurance and features the new tagline “That’s Travel Reassurance”. To stand out from competitors, Avanti’s new branding features a new logo and brand characters, Martha and Arthur. The characters target the company’s key demographic – younger boomers looking to enjoy their retirement years by travelling. The animated grey-haired couple is well dressed and is pictured enjoying typical va-cation activities including lounging by the pool, walking along the beach, and riding an electrical scooter.

Although limited in its scope, the current study intends to provide useful data to read the longitudinal evolution of insur-ance discourse and culture. By exploring how the internal tex-tual dynamics within the two publications constructs notions of ageing, the current analysis aims at uncovering the role that language plays in shaping social identities and relationships (Fairclough 1992: 64). The two commercials will be discussed below. To avoid repetition, I will refer to them interchangeably as ‘advert(s)/ad(s)’ or ‘commercial(s)’.

4 Retrieved February 10, 2018 from https://www.avantitravelinsurance.

co.uk/stringfellow-advertising-campaign.

5. Analysis

5.1 Advert 1 – Broadcast 2010-2015, 30 seconds

In terms of its visual content, the Avanti’s television com-mercial under analysis6 introduces new participants (or objects)

and/or contexts into the image sequence, in which, it is the duty of the audience to relate the social relations appearing in the images with situations they may feel identify with. In particu-lar, it shows a series of radiant, relaxed, affectionate, heterosex-ual couples in a series of scenes including (1) walking hand in hand in a terminal airport; (2) enjoying a mountain view after a Nordic Walking session; (3) sharing an umbrella cocktail at a beach bar; (4) building sand castles with grandchildren; (5) travelling on a sporty, convertible car in the green countryside; (6) dancing on the shore; (7) sunbathing while hugging and looking at the horizon line. The body language and eye contact show intimacy, happiness and trust between the partners. These visual text elements establish an underlying message which is quite clear. They provide an eloquent description of the ben-efits the “stress-free” insurance cover has brought while the characters are “enjoying life to the full”.

Figure 1. Sample frame from Avanti TV ad.

6 “Avanti Travel Insurance” retrieved November 8, 2019 from https://www.

In coherence with the images and the overall account, a relax-ing background tune is heard throughout the ad. The music hard-ly distracts the viewer from the main content and best interacts with the voice-over (Graakjaer 2014) and the numerous captions which are superimposed on screen as the account enfolds7:

00:02 (www.avanti.co.uk) (Call now! Freephone 0800 888 6699) Are you over fifties and traveling abroad? (City breaks, Adventure, Beach)

00:05 (www.avanti.co.uk) (Call now! Freephone 0800 888 6699) Do you have a medical condition. (Cruise) and worry about insur-ance?

00:07 (www.avanti.co.uk) (Call now! Freephone 0800 888 6699) then call Avanti Travel Insurance now on 0800 888 6699

00:10 (www.avanti.co.uk) (Call now! Freephone 0800 888 6699) we’re providers of over fifties (over 50’s travel insurance)

00:12 (www.avanti.co.uk) (Call now! Freephone 0800 888 6699) travel insurance designed for people like you.

00:14 (www.avanti.co.uk) (All pre-existing medical conditions must be declared. Age limits, exclusions & conditions apply) enjoying life to the full. (Diabetes, Stroke)

00:17 (www.avanti.co.uk) (All pre-existing medical conditions must be declared. Age limits, exclusions & conditions apply) we cover a wide range of medical conditions (Pressure, Parkinson’s, Heart At-tack, Multiple Sclerosis) (All pre-existing medical conditions must be declared. Age limits, exclusions & conditions apply).

00:19 (www.avanti.co.uk) (All pre-existing medical conditions must be declared. Age limits, exclusions & conditions apply) so, when it comes to your holiday why

00:21 (www.avanti.co.uk) (All pre-existing medical conditions must be declared. Age limits, exclusions & conditions apply) let anything stop you (Heart Attack, Multiple Sclerosis) get stress-free 00:26 (www.avanti.co.uk) travel insurance now (Authorised and

regu-lated by the Financial Services Authority) call Avanti on 0800 888 6699 (0800 888 6699) (Avanti for life’s adventures!)

00:27 (www.avanti.co.uk) (0800 888 6699) (Avanti for life’s adventures!) (Authorised and regulated by the Financial Services Authority) 00:30 (www.avanti.co.uk) why wait for life’s adventures (Authorised

and regulated by the Financial Services Authority) (0800 888 6699) (Avanti for life’s adventurers)

Table 1. Transcript of superimposed voice-over and captions.

The verbal text is characterized by a semi-formal style with little distance between the audience and the writer. The viewer is appealed to directly through the use of questions. The target consumers are identified by the social category of age “Are you over fifties” and in terms of their needs “traveling abroad” and physical properties “Do you have a medical condition […]?”. The company is actually involved, as first person subjective personal pronoun, in the following sentences: “we’re provid-ers of over fifties travel insurance designed for people like you enjoying life to the full”; “we cover a wide range of medical conditions”. Both the use of the pronoun and the contracted verb form “we’re” realize an atmosphere of proximity and reci-procity enabling the text to draw on the genre of conversation defined by Cook (2001) as “the prototype of interactive recip-rocal communication in which formalities and differences of rank are often diminished or partially suspended” (ibid: 173).

However, the analysis of nominalization is not sufficient to explain how responsibility or agency are assigned or evaded in this textual sample. The text instils in the target consumer the motivation, the sense of urgency and the feeling of personal re-sponsibility for making the most of their life by means of both verbal and non-verbal resources. For instance, the causative verb “let” included in the line “when it comes to your holiday why let anything stop you” seems to carry out the social practice of holding members of the audience responsible for their actions. Despite being generic, the ‘call for action’ is clear and empha-sized by frequent use of superimposed captions to provoke an immediate response by the audience. This persuasion strategy is also used at the lexical level. Nouns related to the conceptual

domain of travel and leisure, such as “City breaks, Adventure, Beach, Cruise, Holiday” are progressively replaced by nouns belonging to the semantic fields of illness or disease, such as “Diabetes, Stroke, Pressure, Parkinson’s, Heart Attack, Multiple Sclerosis, Heart Attack, Multiple Sclerosis”. What links both groups of nouns is that they all relate to the need to purchase an insurance cover in order to experience “stress-free life’s adven-tures”. However, by insistently utilizing action-based messages, “call Avanti”, “call now!”, “why wait” and a plethora of health-related nouns a sense of urgency and risk is created.

Moreover, the advertisement’s catch phrase “Avanti for life’s adventurers” and the video frames showing people having a good time on holiday, are likely to suggest an image of mature travellers, who share common tastes and recreational activities, fulfil their obligation to offspring while keeping romanticism alive and accessing new experiences and possibilities. Howev-er, a tension can be detected in this multimodal text between the old-fashioned, recessive codes of later life and the dominant, stereotypical codes that structure the notion of “positive age-ing” today. The visual component of the advert, which mainly conveys the positively ageing lifestyles of leisure and sociabil-ity, stands in direct opposition to the construction of later life as connoted by both audio and textual elements. In other words, although the characters are represented while enjoying some quality time together, making lasting memories and taking on retirement as an “adventure”, to persuade the consumer to avoid risks and uncertainties, the reference to complex health issues which, as previously mentioned, accompanies most of the visu-als is insistently used making the notion of mature travel and retirement more austere and recessively connoted by declining health and compromised bodies. The advertisers do not refer to other usual benefits covering unexpected events such as street crime, scams, trip cancellations, luggage loss, theft or damage. However, if the images and both superimposed voice-over and captions seem to contradict each other, the persuasion strategy is clear and tries to induce a sense of vulnerability in the target audience for economic gain. While acknowledging that com-mercial operators may supply valuable services to vulnerable consumers and that ageing brings with it greater susceptibility

to chronic diseases: “[t]his kind of advertising that highlights vulnerability has several subtexts. It is designed to make peo-ple feel they need help even if they are perfectly fine. It tells people that even when we think we are self-sufficient, strong, and successful, we are vulnerable to severe harms and losses, and we need to line up help while we still can […]” (Stone 2010: 56).

5.2 Advert 2 – Broadcast 2016-2018, 30 seconds

The latest Avanti campaign8 “Are you a little bit avanti?”,

developed to work across various mediums, from TV to so-cial media, and designed to inject a bit of humour into the travel insurance sector, challenges the viewer’s expectations by using a different range of linguistic and discursive resourc-es. In terms of its visual content, the ad shows the 75-year-old Peter Stringfellow standing in front of a lush red curtain, reminiscent of his working environment (he was credited to pioneer striptease in the international nightclubbing scene), while stripping his clothes off and getting ready for sunbath-ing and chillsunbath-ing out on the beach.

Figure 2. Sample frame from Avanti TV ad.

8 “Are You A Little Bit Avanti – Black Tie”, retrieved February 10, 2018 from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZCdFrnrnUZQ.https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=sIQwG2CKQY0.

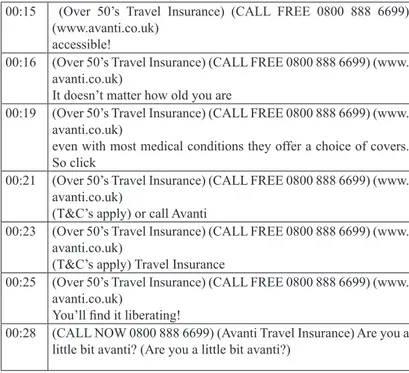

In this more recent commercial, the identification of the target segment “Over 50’s Travel Insurance” is repeatedly acknowl-edged in the captions. As testimonial of the company, Stringfel-low informs, demonstrates and documents his stress-free leisure time while addressing the viewer through direct eye contact in a simulated form of interaction – a typical setup for celebrity endorsements. Therefore, the standard customer, who might be concerned about travel risks and insurance costs and services is not represented. The mute and anonymous heterosexual couple has been replaced by Mr. Stringfellow who, as celebrity testimo-nial, has the knowledge and experience to form a valid opinion about enjoying travelling at a later age: “I don’t think age should get in the way of having a good time, especially on holiday” and is entitled to suggest the right insurance company: “Avanti is your expert of making travel accessible!”.

00:03 (Over 50’s Travel Insurance) (CALL FREE 0800 888 6699) (www. avanti.co.uk)

Avanti…What a great word! It means…

00:04 (Over 50’s Travel Insurance) (CALL FREE 0800 888 6699) (www. avanti.co.uk) forward

00:06 (Over 50’s Travel Insurance) (CALL FREE 0800 888 6699) (www. avanti.co.uk)

I am a little bit avanti myself

00:08 (Over 50’s Travel Insurance) (CALL FREE 0800 888 6699) (www. avanti.co.uk)

I don’t think age should get in the way of having a good

00:09 (Over 50’s Travel Insurance) (CALL FREE 0800 888 6699) (www. avanti.co.uk)

Time

00:10 (Over 50’s Travel Insurance) (CALL FREE 0800 888 6699) (www. avanti.co.uk)

Especially

00:13 (Over 50’s Travel Insurance) (CALL FREE 0800 888 6699) (www. avanti.co.uk)

on holiday! Avanti is your expert

00:14 (Over 50’s Travel Insurance) (CALL FREE 0800 888 6699) (www. avanti.co.uk)

00:15 (Over 50’s Travel Insurance) (CALL FREE 0800 888 6699) (www.avanti.co.uk)

accessible!

00:16 (Over 50’s Travel Insurance) (CALL FREE 0800 888 6699) (www. avanti.co.uk)

It doesn’t matter how old you are

00:19 (Over 50’s Travel Insurance) (CALL FREE 0800 888 6699) (www. avanti.co.uk)

even with most medical conditions they offer a choice of covers. So click

00:21 (Over 50’s Travel Insurance) (CALL FREE 0800 888 6699) (www. avanti.co.uk)

(T&C’s apply) or call Avanti

00:23 (Over 50’s Travel Insurance) (CALL FREE 0800 888 6699) (www. avanti.co.uk)

(T&C’s apply) Travel Insurance

00:25 (Over 50’s Travel Insurance) (CALL FREE 0800 888 6699) (www. avanti.co.uk)

You’ll find it liberating!

00:28 (CALL NOW 0800 888 6699) (Avanti Travel Insurance) Are you a little bit avanti? (Are you a little bit avanti?)

Table 2. Transcript of spoken text and captions.

While Stringfellow explains the literal and figurative mean-ings of ‘avanti’ – an Italian word meaning ‘forward’, but it is also the equivalent expression of “come on” or “let’s go” and is commonly used to imply someone who is “ahead of oth-ers” but also “older”-, the audience gaze is directed to the man who (1) undresses himself; (2) walks towards the beach in his leopard-print swimsuit; (3) waves at incredulous sunbathers; and (4) happily runs on the beach front. Similar to the previous commercial, then, this second ad focuses on offering lifestyle model rather than just travel insurance. The relaxed atmosphere and joyfulness conveyed by the testimonial are conducive to audience identification and involvement. Furthermore, this commercial is also about ‘escaping’ age-related conventions in general, as the only question directed to the audience seems to imply: “Are you a little bit avanti?”. The setting of the advert

obviously points at an exotic destination in the attempt of tak-ing the audience far away from home and everyday pressure.

In order to directly engage the audience, the viewers are ad-dressed using “you” and “your” in various forms of simulated interaction. As a more aestheticized and visually-engaging advert, a decrease in informational and factual content can be noticed, together with a stronger emphasis on the viewer, who must infer what is occurring by activating expectations and schemata for situations, characters, setting, and cause-and-effect rules. The viewer is thus encouraged “to participate in the little story being played to on the screen” (Rutherford 1994: 69). Contrary to the first advert, this second one shows a higher incidence of colloquial language. Interestingly, the usage of insurance jargon is limited to the minimum (“covers”, “medi-cal conditions”), while the direct reference to the semantic fields of impairment or disability has been replaced by a more vague terminology which adheres to the patterns of ordinary discourse: “it doesn’t matter how old you are. Even with most medical conditions, they offer a choice of covers”. To further shorten the distance between the customer and the company and build trust in the mind of the prospective consumers, the more legitimating and/or reassuring and factual word “expert” is preferred to the more generic “provider” and used to bet-ter clarify the company’s mission statement: “Avanti is your expert of making travel accessible!”. However, the term “ac-cessible” recalls obliquely the specific needs of seniors who together with people with disabilities constitute the accessible tourism market. More traditional ‘call for action’ strategies are employed in this commercial too, such as the capital-lettered message “CALL FREE” followed by the contact information and the web site URL.

6. Discussion

Although these advertisements are not representative of the entire marketing landscape within the country under scrutiny, the financial advertising discourse originated from this data set seems to gradually conform to the dominant paradigms of

suc-cessful and active ageing. Significant differences can be seen between the two adverts, particularly in terms of stylistic and cultural representation and structure. It is clear from this study that the company’s advertising policy seems to have shifted from a more informative and lesson-type format to an entertainment format relying on humour and unexpected situations. The more recent advert reformulates the concepts of later life and mature travel in order to make sense of the most significant changes in the notion of ageing which, through the lens of medicine, has been viewed predominantly in terms of decline and deteriora-tion in other advertising contexts (Coupland 2003; Coupland 2007). Here, the characteristics traditionally associated with youth, such as strength, vitality, energy, progress and optimism, together with the linguistic practices that represent them, have been recontextualized for consumerist purposes. This study pro-vides evidence of a shifting discourse related to later life which is represented and perceived to offer the acquisition of leisure rather than the loss of social worth (of beauty, sexual desira-bility, health and the capacity to fully participate in society). In particular, ageing and retirement are no longer merely the onset of social and cognitive finitude, but they can represent a liberation phase, when people experience a desire to travel, to experiment and skirt around social conventions. Specifically, the advert featuring Mr Stringfellow encourages potential cus-tomers to believe that these products will allow them to be free from the obligation and responsibility of maturity. Optimistic discourses in this study producing the ageing identity as one of “living life at its fullest” are consistent with previous studies in that they offer representatives of older people as productive, ac-tive and successful in line with a present-day society dominated by consumer culture (Chen 2016; Ylänne 2012) and youth val-ues. The dilemma of mortality is “solved” by the concept of the third age, a prolonged period of wellbeing and leisure-oriented lifestyle, which precedes the fourth age, a short, painful descent into decay and death (Laslett 1991). What is promoted is a cul-tural idea of individualistic and agelessness ageing or perma-nent youthfulness, encouraging a “busy body” ethic, portraying older adults as globe-trotting consumers of lifestyles as they glamorously engage in many activities or embark on different

emotional and cultural experiences. In this respect, the texts un-der analysis seem to reinforce existing discourses of ageing as something that needs to be resisted and replaced by a vision of later life which encourages individuals to take responsibility for their own health, financial viability, and motivation for active and youthful lifestyle. On this view of later life, one may argue that it does not take into account any other option of growing older and produces ‘the othering of those who are unwilling or unable to age successfully’ (Sandberg 2013: 20) or being con-formed to this discursive formulation.

7. Conclusion

The demographic composition of society has changed con-siderably in the last decades. And this composition is going to continue to change decades in the future. With the steady growth in the number and proportion of older adults, the world is becoming greyer. Undoubtedly, many advertisers are pay-ing growpay-ing attention to the older segments of the population and in doing so they also create and transmit cultural meaning which necessarily reflects a limited representation of seniors and of their values and needs. Specifically, this preliminary longitudinal study has made an attempt at tracking changing socio-cultural values in the field of insurance advertising to the end of offering valuable insights into the ways ageing and longevity are constructed in today’s society more generally. Significant changes in insurance advertising discourse seem to take place under the influence of social and cultural forces re-lated to reformure-lated conceptions of later life, retirement and mortality. As it has been shown in the previous sections, dif-ferent linguistic devices have been used to shift the audience’s attention away from death- and ageing- related topics and con-cerns to instead place emphasis on the celebration of juvenile vigour and fullness of physical life.

In this respect, the findings tend to confirm the predominant orientations that characterize much of the media’s re-shaping of the experience of ageing via the “positive or active ageing” paradigm which ‘is an integral part not only of advertising

im-agery […] but also elsewhere’ (Ylänne 2012: 13). Represented as bon vivants and wealthy habitués of exotic beaches, older travellers are positioned as customers who need travel insur-ance not because they are at higher risk of incurring in unex-pected health disorders or accidents but because they can live youthful and adventurous lives through complicity, if not ad-herence, to an hegemonic ideal of active or positive ageing. On one hand, this representation of older adults as healthy, active, and socially involved can have positive effects on viewers of all ages by shifting the societal focus from the negative aspects associated with growing older and the awareness of relative proximity to death. On the other hand, this predominantly posi-tive portrayal might also create overly optimistic expectations about ageing which could not be realized. Thus, with the idea that the mediated representation of ageing can have a profound impact on viewers’ perceptions of later life, it seems neces-sary to offer a more diversified and realistic depiction of older adults’ lifestyles, behaviours and traits. This study can be con-sidered as an initial exploration of the emerging tendencies in insurance advertising oriented to older adults from a linguistic perspective; therefore, the considerations made in this work cannot be regarded as definite, but can be seen as promising for developing a more systematic analysis of the contempo-rary insurance discourse which has been neglected in linguistic research to date, in spite of its vital role in shaping social and cultural contexts as well as the identities of all those addressed.

References

Blackburn R. 2002, Banking on Death or Investing in Life: The History and Future of Pensions, Verso, London.

Chen C.H. 2016, “Marketing Discourses of Aging: Critical Di-scourse Analysis of TV Advertising for Over-50s Life Insuran-ce in Taiwan”, Language, 4:1, pp. 7-30.

Chen C.H. & V. Ylänne 2012, “Consumerism v. Constructing Older Age: A Case Study of Over-fifties Life Insurance TV Ad-vertising”, in Ylänne V. (ed.) Representing Ageing. Images and Identities, Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp. 36-52.

Cook G. 2001, The Discourse of Advertising, Routledge, London. Coupland J. & R. Gwyn (eds) 2003, Discourse, the Body and

Identity, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Cowell D.W. 1984, Communication Advertising. The Marketing of Services, Heinemann, London.

Doyle A., J. Brinkmann & E. Breiten 2009, “Insurance Adver-tising: Scary, Funny, Trust-building, or Ethical?”, Journal of Macromarketing 29:4, pp. 427-428.

Fairclough N. 1992, Discourse and Social Change, Polity Press, Cambridge.

Fairclough N. 2001, Language and Power, Pearson, London. Fairclough N. 2003, Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for

Social Research, Routledge, London.

Fatt J. & T. Poon 2002, “When Business Can Be Funny”, Mana-gement Research News 25:1, pp. 39-48.

Fugate D. 1998, “The Advertising of Services: What Is an Appro-priate Role for Humor?”, Journal of Services Marketing 12:6, pp. 453-472.

Graakjær N. 2014, Analyzing Music in Advertising: Television Commercials and Consumer Choice, Routledge, New York. Gulas C.S. & M.G. Weinberger 2006, Humor in Advertising: A

Comprehensive Analysis, Sharpe, Armonk.

Henderson J.C. 2007, “Population Ageing, Tourism and Travel In-surance”, Tourism Recreation Research 32:3, pp. 79-82. Hyde M. 2015, “Travel and Tourism in Later Life”, in Twigg J. &

W. Martin (eds) Routledge Handbook of Cultural Gerontology, Routledge, London, pp. 337-344.

Kirk Y. 1994, “Promotion and Advertising”, in McGoldrick P. J. & S.J. Greenland (eds) Retailing of Financial Services, McGraw-Hill, London, pp. 240-265.

Kress G. & T. van Leeuwen 1996, Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design, Routledge, London.

Laslett P. 1991, A Fresh Map of Life. The Emergence of the Third Age, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Nartey M. & H. Huang 2018, “Situated Identities in the Discourse of Insurance: A Comparative Critical Discourse Analysis of Chinese and British Insurance Contracts”, Language, Di-scourse & Society 6:2(12), pp. 119-132.

O’Halloran K.L. 2011, “Multimodal Discourse Analysis”, in Hyland K. & B. Partridge (eds.) Companion to Discourse Analysis, Continuum, London/New York, pp. 120-137.

O’Shaughnessy J. & N.J. O’Shaughnessy 2002, The Marketing Power of Emotion, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Robson K. & L. Pitt 2014, “The Neglected Art (and Science) of Financial Services Advertising”, in Harrison T. & H. Estelami (eds) The Routledge Companion to Financial Services Marke-ting, Routledge, London, pp. 321-334.

Rutherford P. 1994, The New Icons? The Art of Television Adver-tising, University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Sandberg L. 2013, “Affirmative Old Age: The Ageing Body and Feminist Theories on Difference”, International Journal of Ageing and Later Life 8, pp. 11-40.

Solly M. 2007, “‘Don’t Get Caught Out’: Pragmatic and Discourse Features of Informational and Promotional Texts in Internatio-nal Healthcare Insurance”, Communication and Medicine, 4:1, pp. 27-35.

Stone D. 2010, “Beyond Moral Hazard: Insurance as Moral Op-portunity”, in Baker T. & J. Simon (eds) Embracing Risk: The Changing Culture of Insurance and Responsibility, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 52-79.

van Dyk S. & S. Lessenich (eds) 2009, Die jungen Alten. Analysen einer neuen Sozialfigur, Campus, Frankfurt and New York. Wright M. & T. Watkins 2010, Marketing Financial Services,

Routledge, London.

Ylänne V. (ed.) 2012, Representing Ageing. Images and Identities, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Ylänne-McEwen, V. 2000, “Golden Times for Golden Agers: Selling Holidays as Lifestyle for the Over 50s”, Journal of Communication 50:3, pp. 83-99.