DOI: 10.4018/IJABE.2019010102

A Model of Spontaneous

Remission From Addiction

Chiara Mocenni, Department of Information Engineering and Mathematics, University of Siena, Siena, Italy Giuseppe Montefrancesco, Prevention of Pathological Addictions, ASL Sudest, Siena, Italy

Silvia Tiezzi, Department of Economics and Statistics, University of Siena, Siena, Italy

ABSTRACT

This article develops a formal model of spontaneous recovery from pathological addiction.Itregardsaddictionasaprogressivesusceptibilitytostochasticenvironmental cues and introduce a cognitive appraisal process in individual decision making dependingonpastaddictionexperiencesandontheirfutureexpectedconsequences. Thisprocessaffectsconsumptionchoicesintwoways.Therewardfromusedecreases withage.Atthesametime,cognitiveincentivesemergethatreducetheprobability ofmakingmistakes.Inadditiontomodelingtheroleofcue-triggeredmistakesin individualdecisionmaking,theanalysishighlightstheroleofotherfactorssuchas subjectiveself-evaluationandcognitivecontrol.Theimplicationsforsocialpolicy andforthetreatmentofdrugandalcoholdependencearediscussed. KEywoRdS

1. INTRodUCTIoN

Addictionisdefinedastheconsequenceofrepeateduseofpsychoactivedrugs.It ischaracterizedbyalossofcontroloverdrugseekingwithharmfuleffectsonthe individualandahighprobabilityofrelapseevenmonthsoryearsaftercessationof drugtaking(Volkow&Fowler2000;Fertigetal.2004;Koobetal.2004).Themain problemistounderstandhowtheindividual,substanceandenvironment-relatedfactors involvedcantriggerthestart,sustainrecurrenceorgeneraterelapse. Economistshavedevelopedtheoriestomodeladdiction,theirintereststemming from the social costs and externalities generated by the consumption of addictive substances. These theories can be loosely classified as generalizations of the rational addiction model (Becker & Murphy 1988). Generalizations allow for the presenceofrandomcuesthatincreasethemarginalutilityofconsumption(Laibson 2001);“projectionbias”(Loewensteinetal2003);present-biasedpreferencesand sophisticatedornaiveexpectations(GruberandKoszegi2001);“temptation”(Gul& Pesendorfer2001)wherepreferencesaredefinedbothoverchosenactionsandover actionsnotchosen.BernheimandRangel(2004)inanattempttoharmonizeeconomic theorywithevidencefrompsychology,theneuroscienceandclinicalpractice,regard addictionasaprogressivesusceptibilitytostochasticenvironmentalcuesthatcan triggermistakenusage1,thusexplainingtherelationshipbetweenbehaviorandthe characteristicsoftheuser,ofthesubstanceandoftheenvironment.Neuroscienceand clinicalpracticehaveshownthataddictivesubstancessystematicallyinterferewiththe properoperationofaprocessusedbythebraintoforecastneartermhedonicrewards and lead to strong impulses to consume that may interfere with higher cognitive control.Thereforeconsumptionchoicesaresometimesdrivenbyarationaldecision makingprocess,sometimesbystrongimpulsesleadingtomistakes,i.e.divergences betweenpreferencesandchoices.These theories explain several patterns of addictive behavior, but one aspect leftunexplainedisspontaneousremissionalsoknownasnaturalrecovery.Although addictionisdefinedasachronicandpersistentdiseasebythescientificcommunity (seee.g.theAmericanPsychologicalAssociation’sDiagnosticandStatisticalManual ofMentalDisorders,knownastheDSM-V),recentstudieshavecalledintoquestion whetherthisisanaccuraterepresentation(Slutzke2006;Breidenbach&Tse2016). Clinicalpracticeshowsthatnaturalrecoverycharacterizesasubstantialfractionof individualswithahistoryofpathologicaladdictionandthatthisisnotaninfrequent patternofbehaviorinlongtermaddicts.Howeverthereasonsforitarestilltobe understood. Thispaperofferstwocontributions.First,ittriestosolvetheinterestingpuzzleof naturalrecoverybyidentifyingsomeofitsdeterminantsanditsdynamics.Second,it highlightstheroleofcognitiveprocessestoexplainnaturalrecoveryeveninindividuals withanimportantaddictionhistory. BuildingontheworkofMocennietal.(2011),weextendBernheimandRangel (2004)addictiontheorybyintroducinga“cognitiveappraisal”functiondependingon

futureexpectedlossesaswellasonthepastaddictionhistory.Suchprocessleadstoa reductionoftherewardfromuseasthedecisionmakergrowsolder,anditincreases cognitiveincentivescompetingwiththeHedonicForecastingMechanismthusreducing the probability of making mistakes. A similar mechanism, based on the struggle betweentheimpulsiveandreflectivesystems,isproposedbyBechara(2005)inhis neurocognitivetheoryofdecisionmaking.Wealsoexploretheroleofotherfactors, suchaslearningandindividualheterogeneity.Ourmodeliswellsuitedtoexplain thefollowingdynamicsofquittingbehavior:(i)naturalrecoveryoccurringascold turkeyquittingwithoutanexogenousshock;(ii)gradualquittingafteraperiodof decreasingconsumption;and(iii)quittingoccurringafteraseriesoffailedattempts. Performanceanalysisofthisextendedmodeliscarriedout. Ourresultposesahighvalueonpolicymeasuresincreasingcognitivecontrol suchaseducation,creationofcountercuesandpoliciesthathelptheaccumulationof socialcapital,butitdoesnotruleouttheeffectivenessofmoreconventionalpolicy measures,suchasregulationortaxationoflegaladdictivesubstances. Theremainderofthepaperisstructuredasfollows.Sections2and3providea narrativeofaddictionandofnaturalrecovery.Section4containstheformalanalysis. Section 5 concludes. Appendix A reports the results of the stability analysis of equilibria.AppendixBdevelopstheoptimizationmethodandalgorithm.

2. THE NEURoSCIENCE oF AddICTIVE BEHAVIoR

Drugs stimulate the nigrostriatal and corticolimbic dopaminergic systems (Wise 2004)thusincreasingdopamineconcentrationattarget-cells’receptorlevels.These cerebralsystemshaveevolvednottoentertainaddictivesubstances,buttoensurethe survivaloftheindividualbycontrollingbasicfunctionssuchasmatingorsearching forfoodandwater.Whenthesesystemsareengagedbyaddictivesubstances(Fertig etal.2004;Nestler2003)thedopaminereleasethatoccursinthenucleusaccumbens causesspecificemotionalstates(e.g.euphoria)thatarepowerfuldriversofbehavior. Addictivesubstancesproducehigherdopamineconcentrationsthannaturalrewards. Thus,thereisanincentivetorepeatexperienceswiththosesubstances(Kelley& Berridge2002;Bechara2005;Kalivas&Volkow2002).Moreover,whileinthecase ofnaturalrewardsthedevelopmentofhabitsovertimereducesthequalityandquantity ofpleasure,thisdoesnothappenwithaddictivesubstancesastheyactivateeachtime thesamehedonicresponse(Berridge&Robinson2003). Chronicsubstanceabuseinducesprofoundalterationsofthecerebralmechanisms justmentionedforcingtheusertomakecompulsorychoices.Bypowerfullyactivating dopamine transmission, drugs reinforce the associated learning process ending upbyconstrainingtheindividual’sbehavioralchoices(Berke&Hyman2009).In otherwords,drugsseemtoaffectthebasicHedonicForecastingMechanism2(HFM

henceforth), a simple and fast system for learning correlations between current conditions,decisionsandshorttermrewards.Thereisagrowingconsensusinthe neuroscienceaccordingtowhichaddictionresultsfromtheimpactaddictivesubstances

haveontheHFM.Withrepeateduseofasubstance,thecuesassociatedwithpast consumptioncausetheHFMtoforecastexaggeratedpleasureresponses,creatinga disproportionateimpulsetouse.Thepleasurefollowinguse,theexcessiveandrapid hedonicexpectationinducedbytheHFM,theprogressivefailingofthefrontalcortex tocounterbalancewithrationalchoicesthemorealluringofferofdrugs,allportraya processthatinvariablyregeneratesitselfandseemstohavenoend(Kelley&Berridge 2002;Berridge2004). Althoughdrugaddictionseemstoleadtojustonepossibleresult,forstillunclear reasonsoftenthepatientstopsparticipatingintheineluctabledynamicsofhercaseand ceasestohavethiscompulsionforthedrug.Onecouldsaythatthemultifactoriality sustainingdrugaddictionsometimesceasestoofferthoseprofitsandconveniences considereduptillthenasindispensable.Whenthishappenswithoutprofessionalhelp naturalrecoveryoccurs.

3. NATURAL RECoVERy

Natural recovery is more common than suggested by conventional wisdom and characterizesthewholespectrumofdrugssuchasalcohol(Cunninghamet al.2005; Bischofet al.2003;Weisneret al.2003;Matzgeret al.2005;GrellaandStein2013; Breidenbach&Tse2016),marijuana(Copersinoet al.2006),heroin(Waldorfand Biernacki1979),bingeeating,smoking,sexandgambling(Nathan2003).Longitudinal studieshaveshownevidenceofnaturalrecoveryeveninpathologicalgambling(Slutske 2006)questioningthedefinitionofaddictionasgivenbytheDSM-V. Awell-establishedstrandofliteraturehasfocusedonnaturalrecoveryandseveral reviewsofstudiesexist(Carballoetal2007;Klingemannetal2009;Smart2007; Sobelletal2000;Watson&Sher1998;Klingemannetal.2009),butfindingsin thesereviewshaveyettobesystematizedintoawellformulatedconceptualization explainingwhydecisionstochangeoccur(Klingemannetal.2009). Clinicalandexperimentalresearchhasstudiednaturalrecoveryfromsubstance abuse since the mid-1970s (Vaillant 1982) focusing on triggering mechanisms, maintenancefactorsandontryingtoidentifycommonreasonsforchangeinsubstance use (Prochaska et al. 1992). According to Matzger et al. (2005) factors leading a persontomovefromproblematictonon-problematicalcoholuse,forexample,can beheterogeneous.Inthisstudytwogroupsofproblemdrinkingadults,whoreported drinkinglessattheoneyearfollowup,wereidentifiedinNorthernCalifornia.The firstgroupcamefromaprobabilitysampleinthegeneralpopulation;thesecondwas originatedthroughasurveyofconsecutiveadmissionstopublicandprivatealcohol anddrugproblems.Alogitmodelwasusedtoassessthedeterminantsofsustained remission from problem drinking. The two most frequently endorsed reasons for drinkinglesswerethesameinthetwogroups:acost-benefitanalysisofdrinking,and majorlifechanges.Drinkingcausinghealthproblemswasalsoanimportantreason forquitting.Medicalpersonnelandfamilyinterventionswerefoundtobeunrelatedto improvementsintreateddrinkers.Carballoetal.(2007)recognizecognitiveappraisal

andself-evaluationasacentralaspectofself-changeinotheraddictivebehaviors.In Cunninghametal.(2005)cognitiveappraisalandlifechangesarethemainreasonsfor quitting.Cognitiveappraisalisdescribedasaprocessofself-appraisalofthecostsand benefitsofquitting.Inthelifechangesmotivationthepatients’lifestylesarelinkedto successfulattemptstoquit.Respondentsexperiencingthegreatestreductionintheir negativelifeeventspretopostquitattemptswerehypothesizedtobemostlikelyto havesuccessfullyreducedorquittheiraddiction.Nathan(2003)inhisstudyofnatural recoveryfrompathologicalgambling,alsoarguesthatself-changershavelesssevere drinkinghistoriesandfewersymptomsofdependence.Finally,Breidenbach&Tse (2016)alsoreportednaturalrecoveryfromalcoholanddrugaddictionamongEnglish speakingHongKongresidentsasanevolutionaryprocessoccurringoveralongperiod oftimewithintervalsofcognitiveappraisalandquitattempts. Despitethisempiricalevidence,thereareveryfewmodelsofdecisionmaking describing pathways to natural recovery. The Becker and Murphy (1988) model generatescoldturkeyquittingthroughexogenousshocksorstressfulevents.Suranovic etal.(1999)extendBeckerandMurphytogeneratecold-turkeyquittingofcigarettes’ smokingwithoutrelyingonexogenousshocks.Themotivationtoquitisbasedinstead onchangesintheaddict’sperspectiveasshegrowsolder.Inaddition,thismodel showsthatsomeindividualsmayquitaddictionbygraduallyreducingconsumption overtime.Theseresultsareobtainedbyexplicitlytakingintoaccountthewithdrawal effects(quittingcosts)experiencedwhenuserstrytoquitandbyexplicitrecognition thatthenegativehealtheffectsofaddictiongenerallyappearlateinanindividual’slife. Bothmodelspresupposestandardinter-temporaldecisionmakingimplyingacomplete alignmentofchoicesandtimeconsistentpreferences,therebydenyingthepossibility ofmistakes.Insightsfrompsychologyandtheneurosciencehaveledtonewtheories ofaddictiontryingtobridgethegapbetweenneuroscienceanddecisionmakingand depictingaddictionasaprogressivesusceptibilitytostochasticenvironmentalcues triggeringmistakenusage(Loewenstein1999;Bernheim&Rangel2004).Thesenew theories,however,donotexplicitlymodelpathwaystonaturalrecovery3. Klingemannetal.(2009)highlightedthefollowingaspotentialdriversofnatural recovery: • Someindividualsconfrontedwithaddictioncanmakeinformeddecisionsand developresolutionstrategies;

• An individual’s capacity to terminate chronic substance misuse is very much afunctionoftheresourcesshehasdevelopedandmaintainedoverthecourse of her life. These resources consist of personal attributes, physical and socio-environmentalstructures,culturaldispositionsandrelatedlifecircumstances; • Consequent-drivenreasons(e.g.particularlifeevents)forrecoverycomparedto drifting-outreasons(e.g.rolechanges,growingolder)occursignificantlymore frequentlyamongthosewithmoresevereaddictionproblems; • Muchself-changeresearchhashighlightedtheimportanceofcognitivedecision processes(e.g.balancing)asacentralcharacteristicofindividualchange;

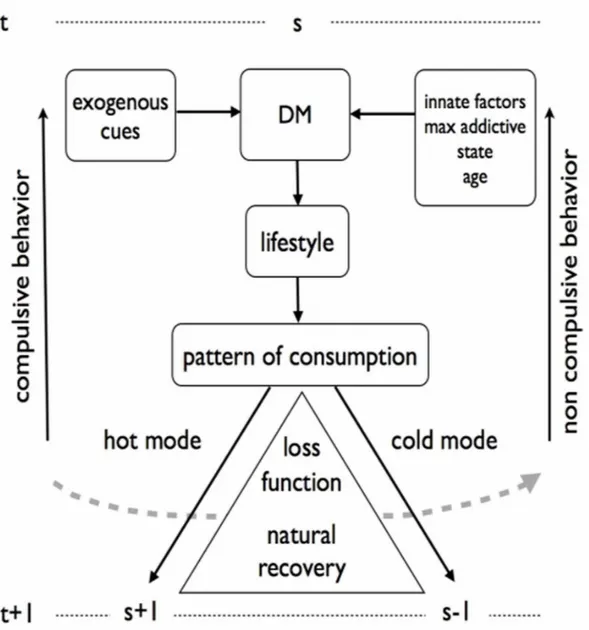

• Acoreconceptofself-changeresearchistoregardchangeasaprocessthat,in mostcases,occursovertime. Inordertoincludethesefactorsinanaddictiontheory,weextendBernheimand Rangel(2004)modelbyexplicitlyconsideringlearning,self-appraisalandcognitive control.AsshowninthenextSection,naturalrecoveryisonepossibleoutcomeof theextendedmodel. Figure1outlinesaschematicrepresentationofourmodel.Consumptionchoices resultfromthecombinationofexogenouscues,innatepropensity,age,lifestyleand sensitizationtoaddictivegoods.ThereinforcingmechanismleadingtheDMtobecome anaddictcanbeaffectedbycognitivefactorsandbytheevaluationofthepastand futurelossesduetocompulsiveconsumptionofaddictivegoods.

4. A ModEL oF NATURAL RECoVERy

BernheimandRangel’s(2004)theoryisbasedontheassumptionthatsubstances’ consumptionisoftenacue-triggeredmistake.Howeveraddictscandevelopagrowing awarenessleadingtoattemptstocontroltheprocess. Drawingfromthistheory,weconsideradecisionmaker(DMhenceforth)whocan operateineithercoldorhotdecision-makingmode(Loewenstein1996and1999).In hotmode,shealwaysconsumesthesubstanceirrespectiveofhertruepreferences.In coldmodeallalternativesandconsequencesareconsidered,includingthelikelihood

Figure 1. Scheme of the mathematical model. External and innate factors influencing the DM. Sequence of decisions taken by the DM (central path). Hot and cold modes of decision leading to compulsive and non compulsive behaviors (left and right cycles). Natural recovery (triangle) may be activated by increasing costs (loss function) and cognitive factors producing switches in the DM’s behavior (dotted line).

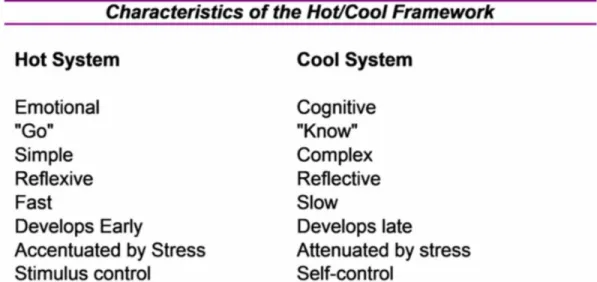

ofenteringthehotmodeinthefuture.Metcalfe&Mischel(1999)adoptedsuchhot/ coldframeworktoexplainthedynamicsofwillpower.Theyalsoreviewedprevious studiesandfieldsofinvestigationinpsychologyinwhichahot/coolframeworkhad beenadopted(Figure2).

Timeisdiscrete,indexedbythenonnegativeintegers,t∈

{

0 1 2, , ,…}

.Ineachtime periodttheDMfirstselectsalifestyleafromtheset{

E A R, ,}

.(e.g.goingtoabar orstayingathomewatchingTV).IflifestyleE,“exposure”,ischosenthereisahighprobability that the DM will encounter a large number of substance-related cues. ActivityA,“avoidance”,entailsfewersubstance-relatedcuesandmayalsoreduce

sensitivitytothem.ActivityR,“rehabilitation”,impliesacommitmenttoclinical

treatmentthecostofwhichisrs,anditmayfurtherreduceexposureandsensitivity

tosubstance-relatedcues.TheDMallocatesresourcesbetweenapotentiallyaddictive goodx ∈

{ }

0 1, thepriceofwhichisq,andastandardgood(

es ≥0)

.Byassumption theDMcannotborroworsave.Eachperiodbeginsincoldmodeandthechoiceof lifestyle,togetherwiththestartingaddictivestatesgivestheprobabilitypsaofcuestriggeringthehotmode.WithsometransitionprobabilitypT,consumptionofthe

addictivesubstanceinstatesattimetmovestheindividualtoahigheraddictive

states+ 1attimet+ 1,andabstentionmoveshimtoaloweraddictivestates−1at timet+ 1.ThereareS+ 1addictivestateslabeleds=0 1, , ,…S.Thesystemdynamics

isdescribedbytheevolutionofstatestaccordingtothefollowingequation: s min p s p s S if x a E A Max p s t T t T t t t T t + + + − ∈ 1 = { ( 1) (1 ) , } = 1, { , } {1, ( −− + − ∈ 1) (1 p sT) }t if xt = 0,at { , , }E A R (1)

Equation(1)impliesthatconsumptioninstatesleadstostatemin S s

{

, t+1}

inthe nextperiodwithprobabilitypT.NouseleadstostateMax{

1,st−1}

withprobability pTfromstates> 1andtostates= 0fromstates = 0 .Thevolumeofsubstance-relatedenvironmentalcuesc a,ω( )

dependsonthelifestyleandonanexogenousstateofnatureωdrawnrandomlyfromastatespaceΩaccordingtosomeprobability measureµ.Weassumethefunctionc a,ω

( )

tobedrivenbyanormallydistributedrandomprocesswithvarianceandmeandependingonthelifestylea.Impulsesc a,

( )

ω place the DM in hot mode when their intensityM a s a

(

, , ,ω)

, denoting the DM’ssensitivitytothecues,exceedssomeexogenouslygiventhresholdMT.Sincepeople

becomesensitizedtocuesthroughrepeateduseM a s a

(

, ', ,ω)

<M a s a(

, ", ,ω)

fors">s', andM a(

, , ,0a ω)

<MT. Moreover,M a s R(

, , ,ω)

≤M a s A(

, , ,ω)

≤M a s E(

, , ,ω)

, i.e. thelifestyleaffectstheDMsensitizationtoenvironmentalcues.WhenM a

(

, , ,0a ω)

>MT theDMentersthehotmode.WeassumethepowerfunctionM tobelogistic,strictly increasingandtwicecontinuouslydifferentiableins: M c a s a c a M e M e a a a s s ,ω , , ,ω ,ω λ λ(

)

(

)

=(

)

+ +(

−)

0 0 1 1 (2)wherea∈

{

R E A, ,}

andM0 =M s(

=0)

andλisthegrowthrateoftheHFMgeneratedimpulses.

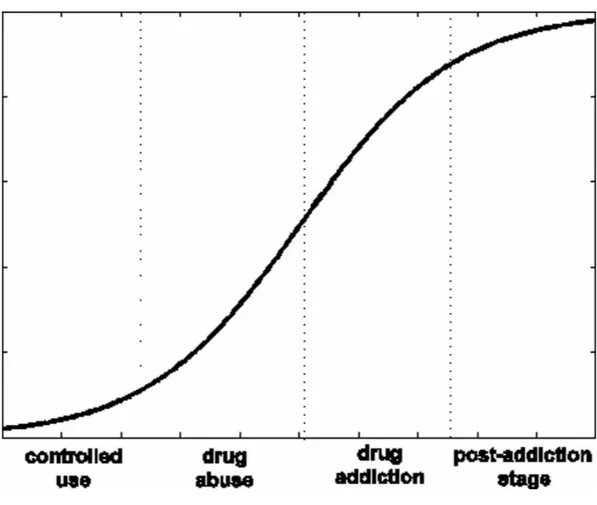

AnexampleofthepowerfunctionM isinFigure3depictingfourdifferentphases

drugaddiction,post-addictionstage.InFigure3M ismeasuredontheverticalaxis andsismeasuredonthehorizontalaxis.Inthefirststage,theDMstartsconsuming adrugdrivenbycuriosity,peerpressure,socialfactors(lifestylesaandenvironmental cuesc.) SensitizationtriggersfurtherexperimentationandincreasestheHFM(M weakly increasingins).Inthefirststagesubjectsreacttothedrugstimuliinacontrolled way.Repeateddrugconsumptionleadstothedrugabusestageinwhichsensitization isverypowerfulandcravingisgeneratedbydrugstimuli(M stronglyincreasingin s).Thedrugaddictionstageischaracterizedbytoleranceandphysicaldependence.

Finally, post-addiction is characterized by decreasing sensitization and periods of abstinenceeventhoughtheHFM-generatedimpulsesarestillactive.

WeconsiderT s a

( )

, ={

ω∈Ω:M a s a(

, , ,ω)

>MT}

.TheDMentersthehotmodeifandonlyifω ∈T s a

( )

, .Lettingpsa =µ(

T s a( )

,)

denotetheprobabilityofenteringthehotmodeattimetinaddictivestatesandlifestylea,anincreaseintheaddictive

statesraisestheprobabilityofenteringthehotmodeatanymoment,becausethe

sensitivity to random environmental cues has increased. Sopsa p s a +1 ≥ ,p a 0 =0 and psE p p s A s R ≥ ≥ ineachtimeperiod. InstatestheDMreceivesanimmediatehedonicpayoffw e x as

(

s, ,)

=u e( )

s +v x as( )

, whereutilityderivedfromnonaddictivegoodsu e( )

s isassumedtobeseparablefrom utilityderivedfromaddictiveconsumptionvs.wsisincreasing,unbounded,strictly concaveandtwicedifferentiablewithboundedsecondderivativeinthevariablees. Moreoverv x as usa b s a ,( )

≡ + ,whereusarepresentsthebaselinepayoffassociatedwithsuccessful abstention in states and activity a , andbsa represents the marginal

instantaneousbenefitfromusetheindividualreceivesinstatesaftertakingactivity a.Bythesameassumption,atanyinstantusE u u s A s R ≥ ≥ andusE u u u s E s A s A + > + .Future hedonicpayoffsarediscountedusinganexponentialdiscountfactorδ.Choicesin coldmodecorrespondtothesolutionofadynamicstochasticprogrammingproblem withavaluefunctionVs

( )

θ andBellmanequationequalto: Vh u b V V a x C h a h a x h a h a x h h a x h θ σ δ σ θ σ θ( )

= + +(

−)

( )

+(

( )max, ∈ − + , 1 , , 1 1))

(3) s t.. 0≤ ≤h S h− =1 Max{

1,s−1}

h+ =1 min S s{

, +1}

C is the set of decision states

{

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

E, ,1 E, , , , ,0 A0 R 0}

;σsa x, represents theprobabilityofconsumingthesubstanceinstatexwithcontingentplan

( )

a x, andθisavectorspecifyingthemodelparameters.ThestationarityofEquation(3)follows fromtheassumptionthattheDMtakesherdecisionatthebeginningofeachperiod4.

Weareinterestedinthechoiceset

( )

E, 0 .Inthiscaseimpulsestousearenotforcedlycontrolledthroughrehabilitation,butabstinenceoccursforhighenoughMT,

thethresholdleveloftheimpulses’intensityrequiredtodefeatcognitivecontrol.

4.1. Expected Losses and Past Addiction Histories

DrawingfromSuranovicetal.(1999)weassumetheDMtobeY yearsoldandT Y

( )

isanonaddict’slifeexpectancyatageY .T Y

( )

islinearinY withT Y'( )

< 0.An addict’slifeexpectancyatageY canberepresentedasT Y( )

− βH withβbeingaparameterweightingthereductioninlifeexpectancycausedbythemaximumaddictive stateH . The present value of an addict’s expected future utility streamV from

VY H s e b dt t Y T Y Y H s r t Y s ,

( )

= = ( )+ + + −(− )∫

β 2 (4)wherer isthediscountrate;e−r t Y(− ) = δisthediscountfactorattimetandbsisthe

individual’sexpectedutilityofconsumingtheaddictivegoodattimet.βH +s 2 is theaveragelostlifecausedbythemaximumaddictivestatereachedinthepastand bythecurrentaddictivestates.ForaDMagedY andmaximumaddictivestateH

thepresentvalueoftheexpectedfuturelossesattimetisgivenby5: LY H s VY H s VY H s T Y Y H s T Y ,

( )

= ,( )

− ,(

+)

= ( )+ + + + ( )+ 1 1 2 β Y Y H s r t Y s e b dt + + −(− )∫

β 2 (5) DifferentiationofEquation(5)withrespecttosleadsto: LY H s e r T Y b H s s T Y Y ' , ,( )

= − − ( )− + ( )+ − β β 2 2 ββ β β H s r T Y H s e + − ( )− + + 2 2 2 bbs T Y, ( )+ −Y H s+ + β 1 2 (6) whereL’isthetimederivativeofL.(6)isweaklypositivebecause: e r T Y H s er T Y H s − ( )− + < − ( )− + + β β 2 1 2 and: b b s T Y, ( )+ −Y H s+ s T Y, Y H s ( )+ − ++ ≤ β β 2 2 1 Asaconsequenceof(5)and(6),futurelossesincreasewiththeaddictivestateas higheraddictivestatescutofftheexpectedbenefitsofthefinalmomentsoflife.As theDMgetsolderthelossfunctionLY H,( )

s rises: ∂ ∂ =(

( )

+)

−(

( )

+)

( )+ − − ( )− ( )+ − L Y T Y b e T Y b Y s T Y Y s rT Y s s T Y Y ' ' , , 1 1 β β β ss rT Y s T Y Y s r t Y s e re b dt + ( ) − ( )−( )+ ( )+ + −(− ) +∫

≥ 1 1 β β 00 (7)Inaddition,futurelossesalsoincreasewithage,asthediscountfactorincreases asonegestsclosertotheendoflife.Ontheotherhand,end-of-lifeutilitieswillbe weightedlessatyoungeragesbecausetheyarefartoodistant. Futureexpectedlossesaffectconsumptionbehaviorinthefollowingways:(i)by increasingMTandbydecreasingtheprobabilityofenteringthehotmode;(ii)by affectingtheBellmanEquation(3)throughthedecreasedprobabilityofuseσ;(iii) byerodingthemarginalbenefitinVSasbsa L Y H − , .Theeffectofpastexperiencesis accountedforintroducingthevariableH =Max s

{ }

i ,i=0 1, , ,… −t 1indicatingthe DM’smaximumaddictivestatereacheduptothecurrentperiodt.4.2. Increasing Cognitive Appraisal

WeconsideravariationoftheM functionandaninitialconditiondenotingthea

priorilevelofcognitivecontrol.ThepopulationofDMsissplitbetweennon addicts

I0 ≥M0andpotential addictsI0 <M0(OrphanidesandZervos1995).Non addicts

mayneverbecomeaddictediftheircompetingcognitiveincentivesarehighenough

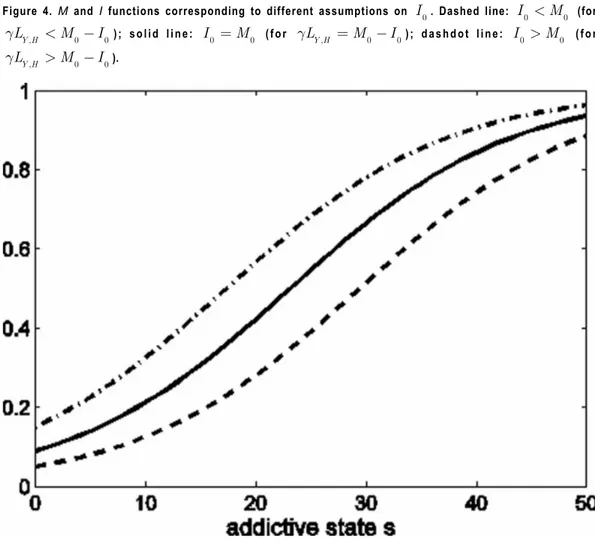

Figure 4. M and I functions corresponding to different assumptions on I0. Dashed line: I0 <M0 (for

γLY H, <M0−I0); solid line: I0 =M0 (for γLY H, =M0−I0); dashdot line: I0 >M0 (for

toavoidthehotmode.WhenI0 <M0theDMisnotyetacquaintedwiththesubstance

anditspotentialconsequences.InthiscasetheI functionforpotential addictsis

relatedtothelossfunctionLY H,

( )

s inthefollowingway: I s Y I e I e s s ,( )

= +(

−)

0 0 1 1 λ λ (8) whereλisthesameasinEquation(2).Theinitialconditionisdefinedas: I =I +γg L( )

(9)whereI0andgaccountforDMsheterogeneity,andtheincreasinginLY H, functiong

isdefinedastheadditionalcognitivecontrolarisingfromthepresentvalueoffuture expectedlossesLY H, .Isatisfiesthefollowingproperties:I s Y

(

',)

<I s Y(

",)

fors'<s";I s Y

(

, ')

<I s Y(

, ")

forY'<Y".Moreover,itisstrictlyincreasinginLY H,( )

s andtwicecontinuouslydifferentiableins.γindicatesthepresenceoflearningprocessesrelated

tothepasthistoryofconsumption,ageandawarenessoffutureexpectedlosses.We assume0≤ ≤γ 1withγ=1implyingperfectlearningandγ = 0implyingabsence

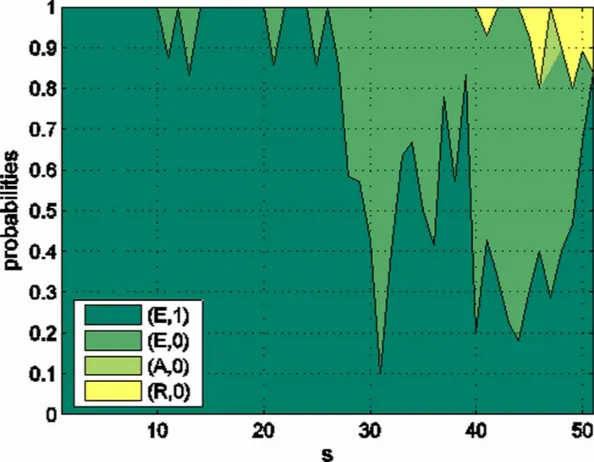

Figure 5. Frequency of decisions for each addictive state s

of learning. GivenI0, the presence of learning may drive cognitive incentives to

overridetheHFMimpulsestouseforsufficientlyhighY andH.InFigure4weplot

theIfunctionagainsttheaddictivestatescorrespondingtodifferentvaluesofthe

initialconditionI0.

Astimetandaddictivestatesincrease,theI functionmovesupforanyγso

that different values ofI are associated with the sames. When theI function

overridestheHFM,theprobabilityofenteringthehotmodeisdriventozero.Similar

Table 3. Summary statistics on initial level of cognitive control l0

dynamicsoccurwhenI0increases.Naturalrecoverycanthusbethelong-termoutcome

ofacompetitionbetweenHFM-generatedimpulsesandcognitiveincentivesI. AppendixAdetailstheconditionsunderwhichI s Y

( )

, >M s a(

, ,ωa)

andshowsthatthe equilibrium solutionseq = 1 is globally asymptotically stable for the dynamic

systemdescribedin(1).Inparticular,weprovethefollowingpropositionsinAppendix A.

Proposition 1:

(1)HighervaluesofI0decreasetheprobabilitypsa andthustheprobabilitiesσ s E,0

andσsA,0;

(2)Highervaluesofγdecreasetheprobabilitypsaandthustheprobabilitiesσ s E,0

andσsA,0.

Proposition 2:

Theequilibriumsolutions=seqisgloballyasymptoticallystable.

4.3. Simulations and discussion

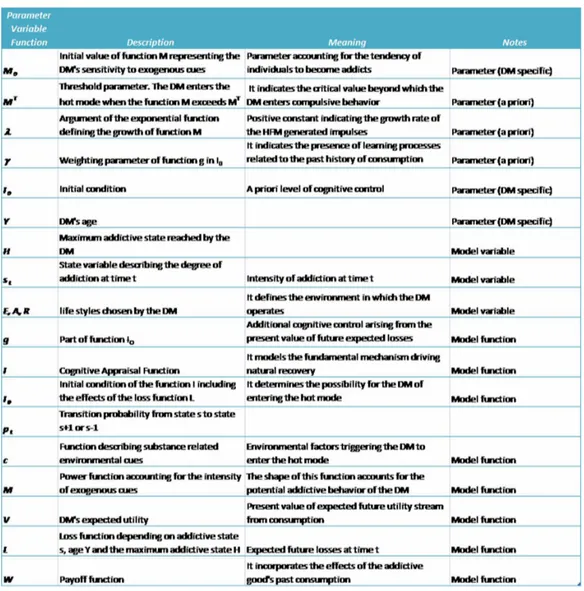

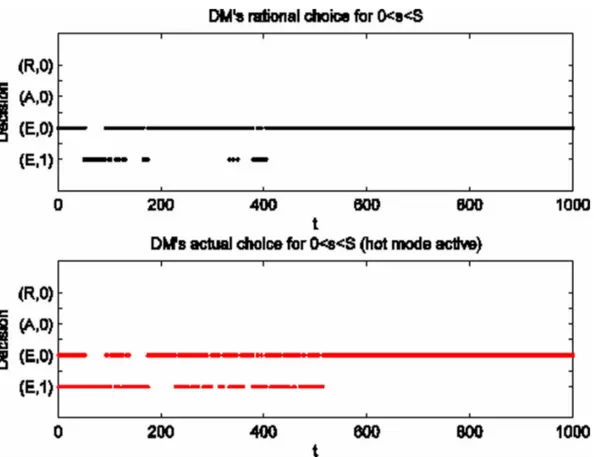

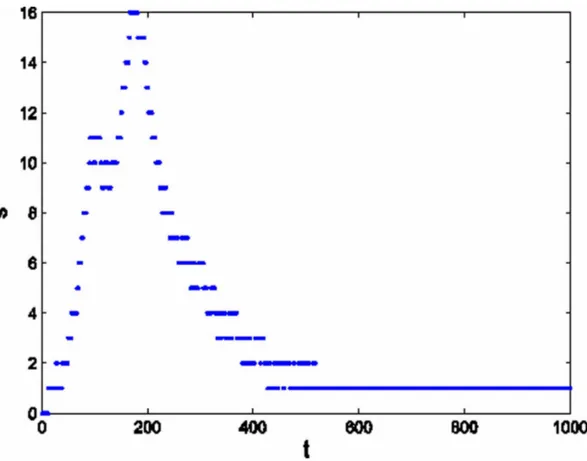

Thissectionshowsnumericalsimulationsoftheextendedmodelanddiscussesthe theoreticalresults.Thenumericalsolutionsareobtainedsolvingthestochasticdynamic programmingproblemimpliedbythemodelanddescribedinAppendixB.Table1 containsadescriptionofthemainvariablesandthemodel’sparameters. Thenumericalassumptionsonthecharacteristicsofthesubstanceandtheuser aretakenfromBernheimandRangel(2005).WeconsiderS = 50;ys=800$;t=1 week;simulationlength=1000periods(20years);costofaddictivesubstance= 200$;costofrehabilitation=250$;decisionsset( ) ( ) ( )

E, ,1 E, , ,0 A0 ,( )

R, 0 .Figure5 showstheprobabilityofeachchoiceasafunctionoftheaddictivestates. Tables2and3showsomesummarystatisticsofthesimulationsperformedby varyingincomeyandinitialcognitivecontrolI0withrespecttotheirbaselinevalue y I*, * 0(

)

. Means (1st column), Standard Deviations (STD, 2nd column), Absolute Maxima(3rdcolumn)andtimeperiodsatwhichnaturalrecoveryoccurs(5thcolumn) areshown.STDofMax(4thcolumn)isthestandarddeviationoftheabsolutemaximum correspondingtoeachrun.Allstatisticsareevaluatedon10runsoftheevolutionof theaddictivestates.ChoicesovertimeareshowninFigure6.Figure7showsthe evolutionoftheaddictivestatesleadingtonaturalrecovery. Additionalresultsconcerntherelationshipbetweenthemodelsolutionsandthe parameters.Inparticular,weprovethefollowingpropositionsinAppendixA. Proposition 3: AssumefixedalltheparametersinϕexceptforI0: (1)OnaverageanincreaseinI0lengthensthetimeintervalbetweentheinitial useandthemaximumaddictivestateHandshortenstheintervalbetweenH andnaturalrecovery. (2)OnaverageanincreaseinI0lowersthemaximumaddictivestateH . Proposition 4:Assumefixedalltheparametersinϕexceptforγ.Anincreaseinγshorthensthe

intervalbetweentheinitialuseandthemaximumaddictivestateHandanticipates

naturalrecovery.

Both the numerical simulations and the theoretical results show that natural recoveryisapossibleoutcomeofanextendedmodelaccountingforlearning,cognitive controlandself-appraisal.Identifyingfactorsleadingtonaturalrecoveryanditslong-rundynamicsmayhelpdesigningpolicymeasuresaimedatreducingconsumption ofaddictivegoods.Ifconsumersaresometimesrationalandsometimesdrivenby cue-triggeredmistakes,measuressuchastaxationoflegaladdictivesubstancesor strictregulationmayonlyraisethecostofconsumption.However,ifspontaneous remissionoccursthroughincreasedawarenessoffutureexpectedcostsandlearning frompastexperiences,standardpublicpolicyapproachescanstillplayarole.The

implication of our model is that more attention should be paid to education and information policy measures relative to health and pharmacological ones. Policy strategiesdifferentiatedbytheageprofileofthepatientscouldbeuseful.Inyoung consumers cognitive therapies, education and information campaigns can have a positiveimpactnotonlytodiscourageinitialexperimentation,butalsoonI0andγ, andcanhelpindividualsactivatecognitivecontrolmechanisms.Trosclairetal.(2002) stressthatmoreeducatedindividualsarefarmorelikelytosuccessfullyquitsmoking, forexample,aseducationhelpsthemactivatingthecompetingcognitiveincentives necessarytooverridetheHFM.Oldestconsumers,ontheotherhand,maybemore responsivetoregulationbecausetheircognitivesystemismoredevelopedandmore likelytoprevailoverimpulsestouse.

5. CoNCLUSIoN

Weproposeadecisionmakingmodelexplaininghowevenlongtermaddictsmay findtheirwayoutofsubstanceabusewithouttheutilizationofprofessionalhelp. Eventhoughnaturalrecoverycharacterizesasubstantialfractionofindividualswith ahistoryofpathologicaladdiction,researchisstillscarce.Spontaneousremission becomes a possibility when additional decision making factors, neglected by the previousliterature,aretakenintoaccount.Drawingfromclinicalandexperimental research,weintroduceacognitiveappraisalfunctiondependingonpastaddiction historiesaswellasonfutureexpectedconsequencesofaddictiveconsumption.This affectsthedecisionmakerintwoways:iterodesthepayofffromuseasthedecision makergrowsolderanditincreasesthecognitivecontrolcompetingwiththehedonic impulsestousethusreducingtheprobabilityofenteringthehotmode. Futureresearchcouldfocusonempiricaltestsandcalibrationofthemodel,if appropriate longitudinal data are available. The estimated parameters incorporate informationonindividualtraitsthatmaybecrucialfornaturalrecovery.Moreover, parameters estimation would allow classification of population groups based on theiraddictivebehavior.Thisinformationcouldthenbeusedtodesignappropriate addictioncontrolmeasures.REFERENCES

Bechara, A. (2005). Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resistdrugs:Aneurocognitiveperspective.Nature Neuroscience,8(11),1458–1463. doi:10.1038/nn1584PMID:16251988

Becker,G.,&Murphy,K.(1988).ATheoryofRationalAddiction.Journal of Political

Economy,96(4),675–700.doi:10.1086/261558

Berke,D.,&Hyman,E.(2000).Addiction,DopamineandtheMolecularMechanisms of Memory. Neuron, 25(3), 515–532. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81056-9 PMID:10774721

Bernheim,D.,&Rangel,A.(2004).AddictionandCue-TriggeredDecisionProcesses.

The American Economic Review,94(5),1558–1590.doi:10.1257/0002828043052222

PMID:29068191

Bernheim,D.,&Rangel,A.(2005).FromNeurosciencetoPublicPolicy:ANew EconomicViewofAddiction.Swedish Economic Policy Review,12,99–144.

Berridge,K.(2004).Motivationconceptsinbehavioralneuroscience.Physiology &

Behavior,81(2),179–209.doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.004PMID:15159167

Berridge,K.,&Robinson,T.(2003).ParsingReward.Trends in Neurosciences,28(9), 507–513.doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00233-9PMID:12948663

Bischof,G.,Rumpf,J.,Hapke,I.,Meyer,C.,&Ulrich,J.(2003).TypesofNatural Recovery from Alcohol Dependence: A Cluster Analytic Approach. Addiction

(Abingdon, England), 98(12), 1737–1746. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00571.x

PMID:14651506

Breidenbach,S.,&Tse,S.(2016).ExploratoryStudy:Awakeningwithnaturalrecovery fromalcoholanddrugaddictioninHongKong.Journal of Humanistic Psychology,

6(5),483–502.doi:10.1177/0022167815583214

Carballo,J.L.,Fernandez-Hermida,J.R.,Secades-Villa,R.,Sobell,L.C.,Dum,A., &Garcia-Rodriguez,O.(2007).NaturalRecoveryfromAlcoholandDrugProblems:a MethodologicalReviewoftheLiteraturefrom1999through2005.InH.Klingemann &L.C.Sobell(Eds.),Promoting Self change from Addictive Behaviors: Practical

Implications for Policy, Prevention and Treatment(pp.87–101).NewYork:Springer.

doi:10.1007/978-0-387-71287-1_5

Copersino,M.,Boyd,S.,Tashkin,D.,Huestis,M.,Heishman,S.,Dermand,J.,& Gorelick,D.et al.(2006).QuittingAmongNon-Treatment-SeekingMarijuanUsers: ReasonsandChangesinOtherSubstanceUse.The American Journal on Addictions,

15(4),297–302.doi:10.1080/10550490600754341PMID:16867925

Cunningham,J.,Cameron,T.,&Koski-Jannes,A.(2005).Motivationandlife-events:A perspectivenaturalhistorypilotstudyofproblemdrinkersinthecommunity.Addictive

DiChiara,G.(2002).Nucleusaccumbensshellandcoredopamine:Differentialrolein behaviorandaddiction.Behavioural Brain Research,137(1-2),75–114.doi:10.1016/ S0166-4328(02)00286-3PMID:12445717

Fertig, A., Glomm, G., & Tchernis, R. (2004). Memory and addiction: Shared neuralcircuitryandmolecularmechanisms.Neuron,44(1),161–179.doi:10.1016/j. neuron.2004.09.016PMID:15450168

Grella, C. E., & Stein, J. A. (2013). Remission from substance dependence: Differencesbetweenindividualsinageneralpopulationlongitudinalsurveywhodo anddonotseekhelp.Drug and Alcohol Dependence,133(1),146–153.doi:10.1016/j. drugalcdep.2013.05.019PMID:23791039

Gruber,J.,&Köszegi,B.(2001).IsAddictionRational?TheoryandEvidence.The

Quarterly Journal of Economics,116(4),1261–1303.doi:10.1162/003355301753265570

Gul,F.,&Pesendorfer,W.(2001).TemptationandSelf-Control.Econometrica,69(6), 1403–1435.doi:10.1111/1468-0262.00252

Kalivas,P.,&Volkow,N.(2005).TheNeuronalbasisofAddiction:Apathologyof motivation and choice. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(8), 1403–1413. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1403PMID:16055761

Kelley,A.,&Berridge,K.(2002).TheNeuroscienceofnaturalrewards:Relevance to addictive drugs. The Journal of Neuroscience, 22(9), 3306–3311. doi:10.1523/ JNEUROSCI.22-09-03306.2002PMID:11978804

Klingemann,H.,Sobell,M.B.,&Sobell,L.C.(2009).Continuitiesandchangesin self-changeresearch.Addiction (Abingdon, England),105(9),1510–1518.doi:10.1111/ j.1360-0443.2009.02770.xPMID:19919592

Koob,G.F.,Ahmed,S.H.,Boutrel,B.,Chen,S.A.,Kenny,P.J.,Markou,A.,& Sanna,P.P.et al.(2004).Neurobiologicalmechanismsinthetransitionfromdrug usetodrugdependence.Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews,27(8),739–749. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.007PMID:15019424

LaSalle,J.P.(1997).“StabilityTheoryforDifferenceEquations”,Studies in Ordinary

Differential Equations.InJ.Hale(Ed.),MAA Studies in Mathematics(Vol.14,pp.

1–31).TaylorandFrancisPublishers.

Laibson, D. (2001). A Cue Theory of Consumption. The Quarterly Journal of

Economics,116(1),81–119.doi:10.1162/003355301556356

Loewenstein, G. (1996). Out of Control: Visceral Influences on Behavior.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,65(3),272–292.doi:10.1006/

obhd.1996.0028

Loewenstein,G.(1999).AVisceralAccountofAddiction.InJ.Elster&O.J.Skog (Eds.), Getting Hooked: Rationality and Addiction. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139173223.010

Loewenstein, G., O’Donoghue, T., & Rabin, M. (2003). Projection Bias in PredictingFutureUtility.The Quarterly Journal of Economics,118(4),1209–1248. doi:10.1162/003355303322552784

Matzger, H., Kaskutas, L., & Weisner, C. (2005). Reasons for drinking less and their relationship to sustained remission from problem drinking. Addiction

(Abingdon, England),100(11),1637–1646.doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01203.x

PMID:16277625

Metcalfe, J., & Mischel, W. (1999). A Hot/Cool-System Analysis of Delay of Gratification: Dynamics of Willpower. Psychological Review, 106(1), 3–19. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.106.1.3PMID:10197361

Mocenni,C.,Montefrancesco,G.,&Tiezzi,S.(2011).CognitiveFactorsandChanges inIndividualDecisionMaking:FromDrugAddictiontoNaturalRecovery.Chaos

and Complexity Letters,4(3),61–73.

Nathan, P. (2003). The Role of Natural Recovery in Alcoholism and Pathological Gambling.Journal of Gambling Studies,19(3),279–286.doi:10.1023/A:1024255420820 PMID:12815270

Nestler, E. (2005). Is there a common molecular pathway for addiction? Nature

Neuroscience,8(11),1445–1449.doi:10.1038/nn1578PMID:16251986

Orphanides,A.,&Zervos,D.(1995).RationalAddictionwithLearningandRegret.

Journal of Political Economy,103(4),739–758.doi:10.1086/262001

Prochaska,J.O.,DiClemente,C.C.,&Norcross,J.C.(1992).InSearchofhow PeopleChange.The American Psychologist,47(9),1102–1114.doi:10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102PMID:1329589

Slutske, W. (2006). Natural Recovery and Treatment-Seeking in Pathological Gambling:ResultsofTwoU.S.NationalSurveys.The American Journal of Psychiatry,

163(2),297–302.doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.297PMID:16449485

Smart,R.(2007).NaturalRecoveryorRecoverywithoutTreatmentfromAlcoholand DrugProblemsasSeenfromSurveyData.InH.Klingemann&L.C.Sobell(Eds.),

Promoting Self change from Addictive Behaviors: Practical Implications for Policy, Prevention and

Treatment(pp.59–71).NewYork:Springer.doi:10.1007/978-0-387-71287-1_3

Sobell,L.C.,Ellingstad,T.,&Sobell,M.B.(2000).AndSobell,M.”NaturalRecovery from Alcohol and Drug Problems: Methodological Review of the Research with SuggestionsforFutureDirections.Addiction (Abingdon, England),95(5),749–764. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95574911.xPMID:10885050

Suranovic, S., Goldfarb, R., & Leonard, T. (1999). An Economic Theory of CigaretteAddiction.Journal of Health Economics,19(1),1–29.doi:10.1016/S0167-6296(98)00037-XPMID:10338816

Vaillant,G.(1982).NaturalHistoryofMaleAlcoholismIV:PathstoRecovery.Archives

of General Psychiatry,39(2),127–133.doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290020001001

PMID:7065826

Volkow, N., & Fowler, J. (2000). Addiction: a desease of compulsion and drive: involvementoftheorbitofrontalcortex.Cerebral Cortex,10(3),318–325.doi:10.1093/ cercor/10.3.318PMID:10731226

Waldorf,D.,&Biernacki,P.(1979).Thenaturalrecoveryfromopiateaddiction:Some preliminaryfindings.Journal of Drug Issues,9,61–76.

Watson, A. L., & Sher, K. J. (1998). Resolution of Alcohol Problems without Treatment:MethodologicalIssuesandFutureDirectionsofNaturalRecoveryResearch.

Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice,5(1),1–18.doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.

tb00131.x

Wise,R.(2004).Dopamine,learningandmotivation.Nature Reviews. Neuroscience,

5(6),483–494.doi:10.1038/nrn1406PMID:15152198

ENdNoTES

1 BernheimandRangel(2004)analysisisrelatedtopreviousworkbyLoewenstein (1996and1999)onthe“cold-to-hotempathygap”. 2 FromBernheimandRangel2004. 3 Bernheim&Rangel(2004)actuallymentionthepossibilityoftheirmodelto generatenaturalrecovery.4 Bernheim and Rangel (2004) show that this model generates a number of

addiction patterns. Unsuccessful attempts to quit occur when there is an unanticipated or anticipated and sufficiently slow shift in parameters

θs =

(

p u bs, ,s s)

fromθ '

toθ "

.Cue-triggered recidivismisassociatedwithhigh exposuretorelativelyintensecues,e.g.highrealizationsofc(a,ω).Self-describedmistakesinwhichtheDMchooses(E, 0)or(A, 0)incoldmode,butthenhe

entersthehotmode.Self-control through pre-commitmentgivenbythechoice (R,0)implyingacostlypre-commitment.Self-control through behavioral and

cognitive therapythroughchoice(A,0)implyingcostlycueavoidance.

5 Inwritingequation(5)wedonotaccountfortransitionprobabilitiesaffecting

the evolution of addictive state

s

, because the DM evaluates future losses independentlyofthespeedoftransitionbetweenaddictivestates.6 Stateddifferently,thereexistsasubsetoftherelevantparameterssatisfyingthe

conditionsleadingtonaturalrecovery.

7 Tosimplifythenotationweomit,henceforth,thetimeindexfromvariablesand

APPENdIX A: STABILITy oF THE EQUILIBRIUM SoLUTIoN

Proposition 1:

(1)HighervaluesofI0decreasetheprobabilitypsa andthustheprobabilitiesσ s E,0

andσsA,0;

(2)Highervaluesofγdecreasetheprobabilitypsaandthustheprobabilitiesσ s E,0 andσsA,0. Proof: (1)LetI0'andI 0 "betwodistinctinitialconditionsoftheI function,suchthat

I0' <I0" . From Equation (A8) I s Y I( , , ) < ( , , )I s Y I

0 0

' " ∀s= 0,1, ,…S and

T s a I( , , )0" ⊂T s a I( , , )0' .Itfollowsthatµ( ( , , ')) > ( ( , ,µ ))

0 0

T s a I T s a I " .

(2)Analogously,I s Y( , , ') < ( , ,γ I s Y γ ")forγ' < "γ andµ( ( , , ')) > ( ( , ,T s a γ µT s a γ")). Wenextshowthattheequilibriumsolutionseq = 1isgloballyasymptoticallystable forthedynamicsystemdescribedby(1).(1)isahybriddynamicsystemsasitevolves accordingtodifferentdynamicsdependingonthespecificpointinthestate-input spaceunderconsideration.Ingeneral,PiecewiseAffineSystemsallowtoconsider fundamentalhybridfeaturessuchaslinear-thresholdeventsandmodeswitching.In ourcasetheregimeshiftsdependontheDM’schoicesateachtimeperiodandthe resultingdynamicsystemsis: s s if x s if x s if x s S x s t t t t t t t t t t + + − ∧ ∨ ∧ 1 = 1, = 1, 1, = 0, , ( = 1 = ) ( = 0 = 1) Inthefirsttworegimes,noequilibriumsolutionsexistandthedynamicsisalways increasingordecreasing;inthethirddynamicstherearetwoequilibria:seq1 = 1and seq2 =S.Asymptoticstabilityofoneofthemcorrespondstoeitheraddictivebehavior

leadingtochronicaddiction

(

s =S)

ortonaturalrecovery(

s = 1)

.Anyoscillatingdynamics is due to shifts or to transient behavior. In order to study the stability propertiesofthedynamicsystemwefocusonlyonthethirdregimeandonthetwo single-pointsetsM = {seq1}andN = {seq2}.

Proposition 2:

Theequilibriumsolutions=seq1 isgloballyasymptoticallystable. Proof:

LetL s( ) =t Vmax−V st( )t beafunctiondefinedintheopensetG= {0,1,2, ,… S−1}of thevaluesreachedbythestatevariables.LisacontinuousonGLiapunov

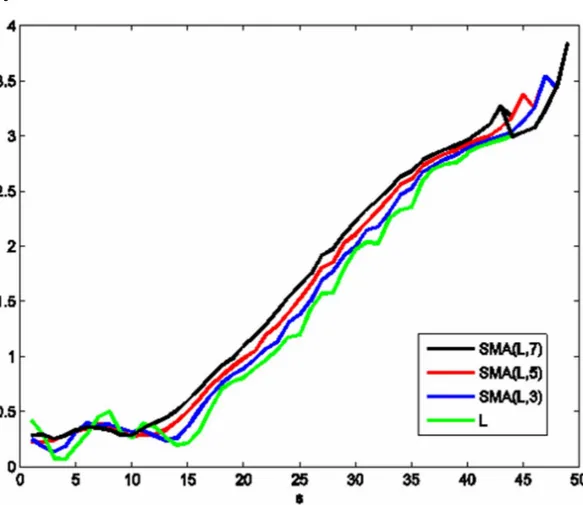

LonthesetGofthestatevariables.Differentcolorscorrespondtosimple

moving averages(SMA) ofL:L (green);SMA L( , 3) (blue);SMA L( , 5) (red);

SMA L( , 7)(black).

M isthelargestinvariantsetinGandGisaboundedopenpositivelyinvariantset.

Then,thetheoremonasymptoticstabilityofthesetM (LaSalle,1997)showsthat

theequilibriums=seq1 isasymptoticallystableonG.Thiscompletestheproof.

Since the loss function decreases the instantaneous marginal benefit from use we expecttheDMtochoose(E,0)whenincoldmodeandforanumberoftimeperiods sufficienttogeneratenaturalrecovery6.

Nowletϕbetheparameters’vector,ϕ= ( , , , , ,δr q y I Ms 0 0, )γ suchthatnaturalrecovery

mayoccur.

Proposition 3:

AssumefixedalltheparametersinϕexceptforI0:

(1)OnaverageanincreaseinI0lengthensthetimeintervalbetweentheinitial

useandthemaximumaddictivestateHandshortenstheintervalbetweenH

andnaturalrecovery.

(2)OnaverageanincreaseinI0lowersthemaximumaddictivestateH .

Proof:

(1)GivenI0 =I0+ γLY H, ,anincreaseinI0isdeterminedbyachangeinthea

priori level of cognitive controlI0. For a given stochastic processω and

lifestylea, this causes psa to decrease (see Proposition 1) at eacht thus

reducing consumption in hot mode and reducing the velocity at whichs

increases. (2)LetI0'andI

0

"betwodistinctinitialconditionsoftheI function,suchthat

I0' <I0". The maximum levels ofsH I'( )'

0 andH I" "

( )0 are reached at two differenttimeinstantst 'andt ".From(i)itfollowsthatt'≤t".Sinceby definitionL H Y( , )isincreasingintime,H I"( )" H I"( )'

0 ≤ 0 .

Proposition 4:

Assumefixedalltheparametersinϕexceptforγ.Anincreaseinγshorthensthe

intervalbetweentheinitialuseandthemaximumaddictivestateHandanticipates

naturalrecovery.

Proof:

AdecreaseinγshiftstheI functiondownwards.FromProposition1thisimplies

anincreaseinpsa whichcausesadelayintheeffectsofthelossfunction.

Propositions3and4implythattheprocessleadingtoadvancedaddictionstagescan besloweddownbyincreasingI0orγ.

APPENdIX B: THE SToCHASTIC dyNAMIC

PRoGRAMMING PRoBLEM

Numericalsimulationsareobtainedbyassigningvaluestothemodelparametersand bymaximizingthevalueFunction(3).

TheparametersoftheM andI functionsare:λ = 0.1,M0 = 0.09,I0 = 0.07and

γ = 1.c a( , )ω isspecifiedbyc a( ,ωa) =k1+k2ωa,whereωaisanormallydistributed

random process with varianceσ2 = 1 and mean depending on lifestylea. The

parametersk1andk2dependonlifestylea.

Takingaquadraticapproximationinalltheargumentsexceptestheinstantaneous payofffunctionwsis7: w e x as s bsa w s u e b u s s a s a , ,

(

)

= +( )

+( )

= + (B1) with:bsa x x xs x a xx a xs a =α +α +α 2 2 2 w s sas sss xs a xs a

( )

=α +α +α 2 2 2 u e( )

s =αelog( )

es +αeelog( )

es +αxexe+αsese usa w s u e s =( )

+( )

w x( )andu e( )s areincreasingandconcaveinx(potentiallyaddictivegood)and e(nonaddictivegood);w s( )isdecreasinginsandtheinteractiontermsαxeandαse

arezerobytheseparabilityassumption.Monotonicityandconcavityofw x( )andu e( )s followfromstandardarguments,whereasthepropertiesofw s( )incorporatetheeffect ofpastuseoncurrentwellbeing,i.e.tolerance,deteriorationofhealth,illness(Figure 9). Thepayofffunctionws t, isspecifiedbyEquation(B1),whereαx = 10,αxx = 0.5− , αs = 1.0− ,αxs = 0.9,αss = 0.1− ,αe = 30,αee = 1− ,es =ys.