Academic Year

2018/2019

PhD Course: Management

Curriculum: Healthcare management

Managing performance in

Healthcare organisations:

Tools, strategies and policy implications

Author

Daniel Adrian Lungu

Supervisor

Table of contents

PREMISES... 9 DATA SOURCES ... 29 RESEARCH OUTPUTS ... 31 Chapter 1 ... 31 Chapter 2 ... 34 Chapter 3 ... 38CHAPTER 1. IMPLEMENTING SUCCESSFUL SYSTEMATIC PATIENT REPORTED OUTCOME AND EXPERIENCE MEASURES (PROMS AND PREMS) IN ROBOTIC ONCOLOGICAL SURGERY - THE ROLE OF PHYSICIANS* ... 43

BACKGROUND ... 45

THE TUSCAN EXPERIENCE WITH PROMS AND PREMS ... 51

METHODS ... 53

RESULTS ... 56

DISCUSSION ... 62

CONCLUSIONS ... 67

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ... 69

ADDITIONAL FILE - WORKSHOP QUESTIONNAIRE (IN ITALIAN) ... 70

REFERENCES ... 76

CHAPTER 2. DECISION MAKING TOOLS FOR MANAGING WAITING TIMES AND TREATMENT RATES IN ELECTIVE SURGERY* ... 83

BACKGROUND ... 85 METHODS ... 89 RESULTS ... 94 DISCUSSION ... 99 CONCLUSIONS ... 101 REFERENCES ... 102 ADDITIONAL FILE 1 ... 106 ADDITIONAL FILE 2 ... 116

CHAPTER 3. INSIGHTS ON THE EFFECTIVENESS OF REWARD SCHEMES FROM 10-YEAR LONGITUDINAL CASE STUDIES IN 2 ITALIAN REGIONS*... 129

INTRODUCTION ... 131

METHODS ... 136

The Tuscany case ... 137

The Lombardy case ... 139

DISCUSSION ... 141

CONCLUSIONS ... 145

REFERENCES ... 150

CONCLUSIONS ... 157

Executive Summary

This doctoral research is a compilation of three papers that jointly investigate the tools and strategies for managing performance in Italian healthcare organisations. The premises introduce the three challenges of healthcare quality that will be discussed throughout the dissertation: the need of more comprehensive and integrated outcome data, the existence and the persistence of medical practice variation, and the complexity improving healthcare quality at the regional level. Chapter One addresses the dynamics of introducing the systematic collection of Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) data and offers insights for the successful implementation of such measures. Chapter Two deals with unwarranted variation and waiting times for elective surgery and provides policy makers and managers with tools able to tackle geographical variation and waiting times without necessarily allocating additional resources. Chapter Three investigates the effectiveness of pay-for-performance programs in driving regional healthcare quality improvement and explores alternative strategies that do not rely on financial rewards. Final remarks, limitations and further research opportunities are presented in the Conclusions section.

Premises

During the Crimean War (1853 - 1856), Florence Nightingale, a British nurse, started collecting figures on wounded soldiers who were generally treated by overworked medical staff, in poor hygienic conditions and with few medicines available. She compared the mortality rate with the care they had received and discovered that effective nursing reduced the death rate from 42% to 2%, mainly by making improvements in hygiene (e.g. handwashing) (Karimi and Masoudi Alavi 2015; McDonald 2001). Her effort of creating an original mortality and morbidity graphical display (called Coxcomb graph or Nightingale rose diagram) and showing it to the British Secretary of War resulted in the immediate allocation of funds to provide modernisation of hospitals which ultimately improved the quality of healthcare they delivered (Dossey 2005). She is therefore considered the pioneer of quality assessment in healthcare and a social reformer who ably used graphical representation of statistics to move the attention towards the importance of outcomes and obtain relevant changes at a system level. Her

achievements are even more impressive if considered against the background of social restraints on women in Victorian England. Her example provides valuable insights on how the evaluation of healthcare performance relies on the importance of measuring outcomes in the first place, and measuring differences in outcomes in the second place. Since then, several stages have followed in the evolution of healthcare quality. Merry and Crago have described the evolution of quality in healthcare as a “learning science” and proposed some key stages of the trajectory, starting with Hippocrates 460 years B.C. and arriving to the 21st century (Figure 1).

After the example of Florence Nightingale, an important next step was made by Dr Ernest Amory Codman, a surgeon who in 1914 worked on the indicator “hospital mortality” in order to detect where errors occurred and prevent them from reoccurring, as he believed that the outcomes of clinical care were the most important thing in the assessment of a hospital. He distinguished mortality between unavoidable and avoidable, the latter depending on the quality of care (Mueller 2019; Brand 2009). Even though it was recognised that outcomes depend also on other factors than care provided, outcome indicators were introduced in many hospitals across Europe and the

United States in the first half of the century. The use of measurable indicators of quality increased, and the second half of the century was characterised by an increasing influence of regulation on medical practice. Indeed in the standardisation phase, the focus shifted from outcome to process indicators, as many process standards had been introduced by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organisations to uniform provision of care and outcomes. Another significant change in the focus on healthcare quality took place during the 1980s, when Avedis Donabedian introduced a new definition of quality, as an optimal triad of three different aspects of health care: structure, process and outcome. Structure refers to the attributes of the care settings and includes material resources, human resources and the organisational structure. Process denotes what is actually done in giving and receiving care, and it includes the patient’s activities in seeking care, as well as the practitioner’s activities in making a diagnosis and recommending or implementing treatment. Outcome denotes the effects of care on the health status of patients and populations (Donabedian 1988). The rapidly changing healthcare environment, the progress of information systems, and the desire to improve outcomes and control costs has stimulated greater interest in the application of outcomes principles to the practices of healthcare providers and in efforts to implement disease management strategies. These programs are based on the underlying assumption that there is a more optimal way to manage patients, which results in lowered costs and improved health outcomes (Epstein and Sherwood 1996). Another important change that was taking place while Merry and Crago published their model in 2001 was the proliferation, in the 1990s - 2000s period, of all forms of

performance indicators as part of attempts to manage health services, and health outcomes have received increased attention. One example is the star rating system that was put in place in England to assess providers’ performance star ratings based on performance indicators and targets (Bevan and Hood 2006, 2004). Hospitals got judged based on nine key targets, including waiting times, cleanliness and financial management. In order to achieve the highest evaluation (three stars), hospitals could afford to under-achieve in only one of the nine targets. In addition to these, a second range of indicators (e.g. mortality, readmissions, patient experience) were used to assess overall performance (the so-called balance scorecard). The use of performance indicators to improve healthcare quality of outcomes, although necessary, presents some pitfalls that scholars have tried to address:

• Interpretation. The root of the problem lies in the interpretation of observational data that does not come from controlled environments and can lead to misleading and biased conclusions (H. T. O. Davies and Crombie 1997; Nutley and Smith 1998). As a matter of fact, most of our environments are not controlled so in these cases some compromises are necessary in practice. The question therefore arises whether our decision models based on data interpretation are requisite, as suggested by Lawrence Philips’s theory (Phillips 1984). Indeed, a model is requisite if its form and content are sufficient to solve the problem, even though not perfect and simplified. The three main simplifications of requisite models refer to i) omitting the elements that are not expected to significantly

contribute to solving the problem; ii) complex relationships between elements are approximated; iii) distinction between form or content may be blurred. • Risk of opportunistic behaviour. When measures are in place and evaluations are

done based on a performance indicator, that leaves floor to a range of opportunistic behaviours to obtain better results. One example is given directly by Florence Nightingale “We have known incurable cases discharged from one hospital, to which the deaths ought to have been accounted and received into another hospital, to die there in a day or two after admission, thereby lowering the mortality rate of the first at the expense of the second” (McDonald 2001). • Comparability. In order to make meaningful comparisons between providers of

for comparing performance over time, some accounting of patient severity is necessary. The application of statistical techniques such as risk-adjustment (or severity adjustment) allows to take into account the differences in patient case mix that influence healthcare outcomes and to reduce the effect of confounding factors (Lane-Fall and Neuman 2013; Di Martino et al. 2014).

• The context matters. Beside the differences between groups at base line (case-mix), when differences are made across geographical areas and it is reasonable to suppose that there will be other contextual and environmental factors which may influence outcomes. There exists a large body of literature on the contextual that potentially impact outcomes, included but not limited to job, income, social class, education, area of living, culture, living alone on the patients’ side, while another range of factors on the system side play as well a key role.

• Data quality and completeness. Even after carefully choosing and rigorously risk-adjusting an indicator, if the dataset on which it draws is complete and inaccurate then its accuracy will be undermined (H. Davies 2005). Moreover, even if completeness and accuracy increase, local variations in how the data is gathered, collected and analysed may exist and they might be responsible for some extent of variation measured (Mannion, Davies, and Marshall 2005; H. T. Davies 2001). • Reliability and validity. In many areas of healthcare death rates is an inappropriate

health outcome and alternative measures have been developed. Before using such measures in practice, their reliability (the confidence that if changes have been made, the measure will produce the same result each time is used) and validity (the degree to which an instrument measures what we intend to measures) must be guaranteed (Roach 2006; H. T. O. Davies and Crombie 1997). • Chance variability. All data presents chance variability that can interfere the interpretation of data either by showing apparent differences that are not real (false alerts or statistical “type 1 error”) or by obscuring real differences (false reassurance or statistical “type 2 error”).

• Performance paradox. Over time, some indicators tend to lose their value as measurements of performance and can no longer discriminate between good and bad performers, resulting in a weak correlation between performance indicators and performance itself (Meyer and O’Shaughnessy 1993; Meyer and Gupta 1994). In the public sector the chances of performance paradox occurring is higher due to some peculiarities such as the discrepancy between the policy

objectives set by politicians and the goals of executive agents (P. Smith 1995), the lack of potential bankruptcy and the disjunction between costs and revenues (Thiel and Leeuw 2002; Le Grand 1991).

The goal of this research thesis is to move along the trajectory of Performance Management in Healthcare by directing the attention towards three of the most prominent and still actual challenges for improving healthcare system quality: the need and utility of more extensive and patient-centered data collection, the need to face medical practice variation and the complexity of driving effective changes in healthcare organisations. One of the most recent stages of healthcare quality, that the model proposed by Merry & Crago could not report in 2001, is that the latest developments in terms of healthcare outcomes must be discussed within the patient-centred care perspective, that has received new prominence with its inclusion by the Institute of Medicine as one of the six aims of quality (Davis, Schoenbaum, and Audet 2005; Baker 2001). McLaughin and Kaluzny proposed a different definition of quality of care that is “the extent to which care processes raise the chance on patient-desired outcomes and reduce the likelihood of undesirable outcomes, given the present state of medical knowledge” (McLaughlin and Kaluzny 2004). The need to incorporate clinical outcomes with the patient’s perspective of outcome emerged (Garratt et al. 2002; Stevens et al. 2001; Coulter, Fitzpatrick, and Cornwell 2009). In order to have a complete assessment of the outcome of a healthcare treatment, it is essential to provide evidence of the impact on patient in terms of health status and health related quality of life. These terms refer to experiences of illness such as pain, fatigue, and disability and also broader

aspects of the individual’s physical, emotional and social wellbeing (Fitzpatrick et al. 1998; Sanders et al. 1998). Integrating Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) with the clinical outcome assessment is the challenge that healthcare systems are facing in order to achieve patient-centeredness and overcome the asymmetrical relationship between the healthcare professionals and the patients. PROMs have initially introduced in clinical trials in order to integrate the clinical data with patient’s subjective perception of their health status and health-related quality of life (Jill Dawson et al. 2010), while in literature the evidence of systematic collection of PROMs is limited. The best known example of routine collection of PROMs data at a system level is the case of the English National Health System (NHS), which in 2009 has started the collection of data before and after surgery for four elective procedures: hip replacement, knee replacement, varicose vein and groin hernia (Varagunam et al. 2014; Rolfson et al. 2011; Peters et al. 2014). Despite since September 2017 the data collection has been ceased for varicose vein and groin hernia surgery, the experience of the English NHS led healthcare systems worldwide to express growing interest in implementing systematic collection of PROMs. The English NHS experience has proven that the routine collection of PROMs is in certain circumstances possible, even though the international literature lists several problems and barriers for the systematic collection of PROMs, ranging from the lack of time, lack of training, doubts about the tool’s validity and reliability, the complexity and the interpretation of measures, language translation, cultural adaptation, cognitive impairment of patients and difficulties of analysing data and dealing with missing values, lack of structure and staff to assist data collection, time consuming and irrelevance for

patients (Bausewein et al. 2011; Dainty et al. 2017; Peters et al. 2014; Hanbury 2017; Valier et al. 2014). Previous studies have found positive relationships between the collection of PROMs and patient satisfaction (Chen, Ou, and Hollis 2013), perceived quality of care (Berry et al. 2011; Basch et al. 2007), patient outcomes (Velikova et al. 2004), symptom management (Kallen, Yang, and Haas 2012) and acceptability (Kallen, Yang, and Haas 2012; Hilarius et al. 2008). On the physicians’ side, the collection of PROMs proved to have a positive impact on patient-clinician communication (Chen, Ou, and Hollis 2013; Luckett, Butow, and King 2009), contribute to a better detection of symptoms and improve their monitoring (Snyder et al. 2012; Erharter et al. 2010; Chapman et al. 2008) and may support clinical decision making (Basch et al. 2007; Nicklasson et al. 2013; Lynch et al. 2011). Given the relevance that PROMs have in the complete assessment of the outcome of healthcare treatments, the first research study presented in this dissertation, by relying on the experience of Tuscany region (central Italy), will provide insights on what are the determinants to achieve a routine collection of patient reported measures by overcoming some of the barriers mentioned above.

The second challenge, that closely relates to the lesson that the example of Florence Nightingale teaches about healthcare quality assessment, beside measuring outcomes, is the need to measure differences in care provided. In 1934 a study revealed how American children were recommended the tonsils removal based mainly on the discretionary choices and decisions of physicians (American Child Health Association, 1934). Indeed, out of 1000 children who were subject to evaluation, 60% were prescribed tonsillectomy. The remaining 400 were subject to an additional evaluation from another

team of clinicians, and 45% of them were suggested tonsils removal. The remaining 220 children went through a third evaluation, and once again 40% received the indication to receive tonsillectomy. Finally, the remaining 132 were subject to a fourth and final evaluation, and once again 51% of them were prescribed the surgical intervention. After the four evaluation rounds, only 65 of the initial 1000 children did not receive the prescription for tonsillectomy. When in 1938 similar local differences in rates of tonsillectomy were shown among British schoolchildren (Glover 1938), it became clear that not all treatments were provided according to evidence-based medicine principles or clinical guidelines. From its pioneering in the 1930s, the concept of geographical variation in healthcare delivery goes rediscovered in 1973 by the studies carries out by John Wennberg, when the population-based health data system in Vermont and Maine revealed wide variation in resource input, utilisation of services, and expenditure among neighbouring communities. Indeed, the authors identified up to 10-fold variation in use of tonsillectomy or other surgical procedures and differences were unrelated to case-fatality (J. Wennberg and Gittelsohn 1973). Since then, health service researchers have documented extensive variation in healthcare services across the world, both in terms of outcomes and care provision (Paul-Shaheen, Clark, and Williams 1987; McPherson et al. 1982; J. E. Wennberg 2011; Seghieri, Berta, and Nuti 2019). In 2010 the Wennberg International Collaborative (WIC) was created to provide a network for investigators who actively research medical practice variation within countries and in the meanwhile the group has published and reported variations from 30 different countries. A full list of the publications, including websites, articles, reports and atlases is available on the WIC

official website (www.wennbergcollaborative.org/publications). John Wennberg, who continued to investigate the phenomenon initially discovered in 1973, proposed a taxonomy for clinical practice unwarranted variation, thus that cannot be explained by type or severity of illness. The categories, that are important because the causes of variation and their remedies differ according to the category, are the following (John E Wennberg 2002): effective care, preference-sensitive care and supply-sensitive care.

• Effective care includes those services whose effectiveness has been proved and for which the benefits outweigh the risks. In this category virtually all patients who are eligible for treatment should be treated and failure to treat represents underuse. Lack of resources cannot be the cause of underuse of effective care, at least in the US. Dartmouth studies have demonstrated that having more physicians, spending more per capita and producing more hospital admission isn’t associated with providing more effective care (Baicker et al. 2004; Baicker and Chandra 2004; John E. Wennberg et al. 2008). Instead, what is associated with this variation seems to be the degree to which care is organised and coordinated; in regions where the coordination is easier and specialists, primary care doctors and other health professionals practise “team medicine”, there is less underuse. Moreover, the BMJ Clinical Evidence 2006 data on almost 3000 procedures (available at https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/evidence-information/) has highlighted that only approximately 11% of procedures have clear evidence based benefit.

• Preference-sensitive care includes conditions where choice should depend on patient preferences as two or more medically acceptable options exist, such as elective surgery services. The essential feature common to all preference-sensitive conditions is that choice should depend on patient preferences as studies have shown that patients who understand and choose their treatment options through a shared decision making process have different patterns of practice with respect to patients who experience usual care (O’Connor et al. 1999). However, in real practice, professional opinion rather than patient preference tends to dominate the treatment choice. It is important to highlight that low elective surgery rates are not necessarily a symptom of undertreatment, but that patients are being treated differently from others. If such differences were to depend exclusively on patients’ choice, variation would be “good” as it would mean it reflects the different treatment options that patients choose. However, in everyday practice they delegate decision making to physicians, and in turn the final decision depends heavily on local medical opinion. As much of the variation for elective surgery depends on the flaws in clinical decision making, strategies aiming at reducing high rates by setting budgets may turn unsuccessful. Instead, rates based on informed patient choice, may be lower than rates where physicians do not actively involve the patient in the choice of treatment (O’Connor et al. 1999). A clinical environment that supports shared-decision making and encourages the active engagement of patients in the choice

of treatment is required to treat patients according to their preferences and avoiding to give them treatments they do not want (J. E. Wennberg 2011). • Supply-sensitive services are important to study as medical theory and evidence

do not influence the relative frequency of their use among defined populations. For these services, the per capita quantity of healthcare resources allocated to a given population (or capacity of the local healthcare system) largely determines the frequency of use. Examples of supply-sensitive services variations arise from the frequency with which patients with chronic diseases use consultations, diagnostic tests, referrals to medical specialists, and hospitalisations. Analysing the reasons why some areas have bigger capacity (number of physicians and nurses, hospital beds, operative rooms, diagnostic machines, etc. per capita) requires to acquire local knowledge about the dynamics of growth, but the question that health services researchers is whether more is better: does greater care intensity lead to better health outcomes? Do low rates indicate that care has been inappropriately rationed or overused in high rates regions? The evidence from the US patients admitted to hospital for hip fractures, heart attacks and colon cancer shows that those living in regions characterised by high intensity of care in terms of number of visits, imaging examinations and admissions, do not have better survival than those living in low intensity of care regions (Fisher et al. 2003; John E. Wennberg 2010).

Beside the original three categories, the rising challenges posed by the management of chronic diseases led to the introduction of an additional category: effective care of an

integrated care pathway. It refers to services whose variation is due to a lack of integration throughout the entire care pathway (Nuti, Bini, et al. 2016). For chronic conditions, the challenge is to undertake the necessary clinical research to convert the “black box” of supply sensitive care into evidence based care that is either effective or preference sensitive (J. E. Wennberg 2011). The focus of improvement must be on care provided over time during the course of a chronic illness and integrated among all settings of care in order have systems capable of coordinating care and to overcome the “silo-vision” of care provision.

It has been found that variation is common across different healthcare systems and to have a relevant impact on the wealth of nations and the health of their populations (J. Appleby et al. 2011; John E. Wennberg 1999). Even though efforts have been made to measure, benchmark and disclose variation data through atlases in several countries, medical practice variation still persists and raises both appropriateness and equity concerns. Beveridge-model public systems should ensure the achievement of equitable and timeliness access to health care regardless of individual ability to pay or other characteristics such as income or region of residence (Nuti and Seghieri 2014). Equity can be distinguished between its vertical and horizontal forms (Barsanti and Nuti 2014; World Health Organization. 2000; Oliver and Mossialos 2004). To achieve vertical equity, the healthcare system should recognise different health needs linked to specific factors such as the socio-economical characteristics (e.g. poverty) of populations or areas and allocate different amounts of resources in order to balance the different starting points with respect to other population groups and reduce inequalities.

To achieve horizontal equity, patients with the same healthcare needs should be able to count on the same care services. Hence, in horizontally unequal systems, for the same level of patient need, there are differences in the resource allocation and/or the quality of care. When this occurs between geographical areas, the so-called “postcode lottery” healthcare arises (Jong 2008). However, there is evidence of unwarranted variations also in horizontally equitable systems with fair allocations, indicating that there are other determinants of variation and reducing horizontal inequity cannot fully tackle it. Moreover, at this point it is necessary to clarify the distinction between variation in treatment rates and outcomes and to highlight that there is no evidence in international literature that unwarranted variations in admission rates simply translate into unwarranted variations in outcomes. Evidence of horizontal inequity is given by unwarranted geographical variations in access rates (e.g. the hospital admission rates for specific treatments), which have been extensively reported in different contexts and for a wide-ranging list of different healthcare services (John E. Wennberg 1999; John E Wennberg 2002; Geographic Variations in Health Care 2014). Given that the Italian NHS is a public health system that follows a Beveridge model and provides universal coverage for comprehensive and essential health services and the implications that unwarranted geographical variation has in terms of equitable care, the second research paper presented in this dissertation investigates the case of elective surgery in Tuscany. It addresses variation both in terms of access (treatment rates) and timeliness (waiting times) for nine high-volume elective surgical procedures and provides policy makers and managers with some useful tools to guide the decision making process for managing

waiting times and treatment rates for these services. The key finding is that for all the nine procedures there is no straightforward relationship between the two, meaning that acting on the supply side by increasing capacity will not reduce waiting times in the long run. Beside failing to shorten waiting lists, additional resources could lead to an increased extent of unwarranted variation, and therefore the paper presents some alternative strategies to tackle unwarranted variation in elective surgery provision. So far two fundamental elements of healthcare quality have been discussed: the importance of focusing on outcomes, by integrating the clinical ones with those reported directly by patients, and the need to manage the differences among different areas or population groups in order to reduce unwarranted variation and disparities in access to health care. Given the limitations presented and the degree of complexity of managing healthcare quality, the third challenge is related to understanding which are the mechanisms and levers that can be used to improve outcomes and tackle unwarranted variation at a system level. To do so, the different perspectives of two of the elements that have characterised the Italian National Healthcare System over the past decades must be taken into consideration: the managerial and the institutional one. Starting from the 1990s, performance management reforms have been increasingly based on the New Public Management framework intended to achieve higher accountability, effectiveness and efficiency for public organisations (Hood 1995, 1991; Lapsley 1999). One of the tools to achieve these goals has been to import from the private sector performance measurement and evaluation systems that, although originally developed for profit-seeking companies, have been proven to be suitable also

for public organisations (Kaplan and Norton 2000, 2001, 1992; Kloot and Martin 2000). Performance evaluation systems (PESs) are crucial for accountability and serve as a feedback and guidance tool for the managerial level of organisations. They can be used to evaluate how well organisations are managed and to measure the value they produce for customers or other stakeholders. From the 1980s, PESs aimed at overcoming the exclusive adoption of solely financial perspective by including multi-dimensional performance indicators (Kaplan and Norton 2000, 2001), supported also by the developments in information technology that facilitated data availability, completeness and accessibility. Therefore, multi-dimensional PESs became fundamental for the management of public organisations. While in other economic sectors the use of PESs is mainly aimed at maximising profit and revenues, this is not the case of public healthcare. Within the healthcare sector, PESs were developed and implemented where non-financial indicators are more important, considering that in many public universal coverage healthcare systems the objective of PESs is to support providers in producing value for patients and populations with the resources made available by the society. In order to do so, PESs in healthcare have been evolving trying to meet the needs of single providers in a complex system in which they operate, by overcoming the organisational boundaries (Bititci et al. 2012). In this perspective, it is possible to rely on benchmarking measures that facilitate and trigger organisational improvement processes to enhance effectiveness based on reputation (Bevan, Evans, and Nuti 2019). PESs that aim at achieving higher efficiency can be characterised by the following elements (Nuti et al. 2015):

• Multi-dimensionality: indicators from multiple dimensions (process, quality of care, equity, etc.) are included within the system;

• Evidence-based: to support stakeholders in decision-making processes;

• Shared design: all stakeholders, and especially health professionals, should be involved in the design and the fine-tuning process of an effective PES;

• Systematic benchmarking: allows the organisations to shift the focus from monitoring to evaluating and improving performance;

• Transparent disclosure: stimulates data peer-review and makes professional reputation leverage possible;

• Timeliness: to allow policy-makers to make decisions promptly.

If such PESs are put in place to drive improvement in health care, then patterns of behaviour of the targeted stakeholders must be changed. This in turn highlights the importance of motivation (or internalised desire for action) and how this might be obtained (i.e. incentives) (H. Davies 2005). Both concepts of motivation and incentives are complex and the relationship between them and between each and the subsequent patterns of behaviour are difficult to untie (P. C. Smith and York 2004; M. Marshall and Harrison 2005). Motivation can be driven by two kind of drivers: intrinsic or extrinsic (Ryan and Deci 2000). Intrinsic drivers refer to those internalised aspects of values that motivate some specific patterns of behaviour, such as meeting the expectations of colleagues, satisfaction for doing a good job, or moral choices about doing the right thing. On the other hand, extrinsic drivers of motivation are those external factors that in fluence

behaviour such as regulations, fear of reputation damage (i.e. naming and shaming) or financial rewards. A wide range of incentives that might be employed to foster quality improvement have been identified and include both financial levers (i.e. bonuses, pay-for-performance) and non-financial ones (i.e. major autonomy) (Rosenthal et al. 2004; Rosenthal and Dudley 2007; Conrad and Christianson 2004). International literature reports clear evidence of the fact that extrinsic factors can be effective in shaping behaviour (P. C. Smith and York 2004; Bevan and Wilson 2013b), while the debate is still open over the magnitude of such effect (M. Marshall and Harrison 2005). One of the underlying concepts of incentives that has been criticised as incomplete is that they assume healthcare professionals as “rational calculating individuals”(Ferlie and Shortell 2001); indeed, policy-makers fashion policies on the assumption that those affected by the policies will behave in certain ways and they will do so because they have certain motivations, most of the times implicit ones. Therefore, by using Le Grand’s words, policies constructed on the assumption that people are motivated primarily by their own self-interest - that they are “knaves” - are quite different from those constructed on the assumption that people are predominantly public-spirited or altruistic - that they are “knights”. Similarly, if policy-makers start from the underlying assumption that people are unresponsive - neither knights or knaves, but “pawns”, policies differ from the ones designed on the assumption that they respond actively to incentives (Le Grand 1997, 2004). Instead, if the focus is shifted from the individual towards value-led behaviour, the challenge becomes to align the values and beliefs of all stakeholders in order to achieve

collective efforts for quality improvement in healthcare organisations (Braithwaite 2018; Wandersman et al. 2015; Renedo et al. 2015).

Starting from the 1990s, the Italian National and Regional Health Systems have gone through a significant reorganisation process. Indeed, for the past three decades regions have seen themselves in the middle of two different processes. On the one hand, they tended to move toward the introduction in the public administration, of performance management tools originally used in the private sector, according to the New Public Management paradigm first (Hood, 1995; Hood, 1991; Lapsley, 1999) and to the Public Governance one later (Osborne 2009).

On the other hand, in several European states, they experienced a process of decentralisation of powers, from the national state to the regions (Saltman, Bankauskaite, & Vrangbæk, 2007; Saltman, Busse, & Mossialos, 2002). Also Italian regions have been transferred administrative, fiscal and managerial autonomy, especially in the healthcare sector (Toth 2014; Fattore 1999). The central level fixes the budget that Regions have and ensure that the essential level of care are guaranteed. Conversely, Regions are responsible for the organisation and the provision of healthcare services, and each Region has fine-tuned its own governance organisation according to the local needs and context (France and Taroni 2005; Pavolini and Vicarelli 2012). As a consequence, in Italy there are 20 different Regional Healthcare Systems that adopt different governance models and management tools (Tediosi, Gabriele, and Longo 2009; Carinci et al. 2012; Ferrè, Cuccurullo, and Lega 2012). This heterogeneity offers the research opportunity to test some main theories about regional governance and policy

making by both comparing different regions or by exploring deeper the dynamics of a single region.

The third and final chapter of this dissertation explores the mechanisms that have been employed to improve quality of outcomes and reduce unwarranted variation in the Italian context. The study relies on the experience of two Italian regions (Lombardy and Tuscany) with financial rewards to drive healthcare quality improvement and sheds light over their effectiveness, as well as the importance of other governance mechanisms.

Data sources

The quantitative data used throughout the three chapters of this dissertation comes mainly from a dynamic public data system fed by regional healthcare organisations with information on manifold performance dimensions. The Inter-Regional Performance Evaluation System (IRPES) has been introduced in 2005 for Tuscan healthcare organisations and nowadays it includes more than 600 single indicators and 60 composite indicators that measures the following dimensions of performance of healthcare providers: population’s health status, ability to pursue the regional strategies, clinical performance, efficiency and financial performance, patient satisfaction and staff satisfaction (Nuti, Seghieri, and Vainieri 2013). Indicators are computed annually, for all the public healthcare organisation by using anonymised administrative or clinical databases data. Some indicators, generally the most relevant, are then evaluated in benchmarking considering international or national/local standards, or the distribution of the observations. The performance evaluation is attributed by using five coloured

evaluation bands ranging from dark green - excellent performance - to red - for very poor performance. As a result of this process, for each evaluation indicator, the level of performance of health organisations is presented on a scale from 1 to 5, from worst to best. In 2008, as other Italian regions expressed their willingness to adopt the same IRPES used by Tuscany and benchmark performance, the Network of Regions was established. The Network, that in 2019 consists of 12 components - 10 Regions and 2 Autonomous Provinces - voluntarily share their performance data through systematic and publicly disclosed benchmarking (Nuti, Vola, et al. 2016).

The other relevant data source, used mainly in the third chapter of this research, is the Tuscan PROMs and PREMs Observatory database that was set up in January 2018. The database contains the Patient Reported Outcome and Experience data from patients who were enrolled in the following care pathways: knee replacement, hip replacement, robotic prostate cancer surgery, robotic lung cancer surgery, robotic colorectal cancer surgery, Chronic Heart Failure (CHF), reconstructive breast cancer surgery and maternal care pathway. The specific data used for the research in chapter three takes into account 14 months of routine collection, from January 1st 2018 to February 28th 2019. The Tuscan PROMs and PREMs Observatory database data have also been complemented with additional data sources (in-depth interviews, in Chapter 1), according to the specific objectives of the research strategy.

Research outputs

This doctoral dissertation lies in three papers that jointly inquire the tools and strategies for managing performance in Italian healthcare organisations. This goal is pursued by exploring three challenges of healthcare quality improvement: the need of comprehensive and integrated outcome data, the existence of unwarranted variation, and the complexity of implementing quality improvement strategies at the regional level. The papers adopt multiple theoretical perspectives, based on the different research questions they aim to address, but they all share the overarching objective of contributing to the body of knowledge of healthcare performance management.

Chapter 1

Chapter 1 aims at conducting a micro level study by investigating the role of individuals in the success (or performance) of the implementation of a routine collection of Patient Reported Outcome and Experience Measures (PROMs & PREMs). The aim of the chapter is to rely on the introduction, in 2018, of PROMs & PREMs in Tuscany and examine how clinicians contributed to the success of such program, in terms of amount of patients enrolled and their response rates, as significant differences were found among the hospitals. As in the Tuscan model the clinicians are in charge with enrolling and informing the patients, the chapter investigates what are the main physician-related

determinants of performance in terms of patient adherence and response rates (RQ1), in order to identify the potentials levers and mechanisms that managers and policy-makers could use to obtain complete patient reported data and integrate them with the traditional clinical evaluations. In addition, the study explores what is the impact that the introduction of patient reported measures has both on physicians and on healthcare organisations (RQ2).

RQ1: What is the role of physicians in the adoption and successful implementation of routine collection of patient reported measures and what are the determinants of their motivation?

RQ2: What is the impact of patient reported measures on physicians and healthcare organisations?

The research draws on the diffusion of innovations theory (Rogers 1995) that examines the process through which information is communicated over time and that can lead to the use of an innovation and on the resource-based theory (Peteraf and Barney 2003) that seeks to explain how organisations maintain sustainable levels of performance according to the amount of resources available.

Our findings suggest that physicians play a key role in the project and the most relevant elements that explain their different degree of engagement, and consequently the different degree of success, are the collaboration with their colleagues and the perceived benefits and beneficiaries of the project. Indeed, the most engaged physicians are those who managed to obtain the support of their ward staff and at the

same time understood that the collection of patient reported measures does not only benefit patients, but also themselves because it serves as a feedback tool and the overall healthcare system. This finding assumes that highly engaged clinicians are knights who act out of altruism towards the quality their patients receive; in a broader sense, the difference stands in the general view physicians have about the aim of the project: the most engaged ones recognise it as a quality improvement tool, while the least motivated who shown mainly a “knavish” behaviour perceived it as a tool to evaluate their performance with no personal benefit, and therefore are not keen to actively take part to it. Moreover, we found that the introduction of patient reported measures have positively impacted engaged physicians as they declare they improved their attention towards patients, again an example of “knightish” behaviour. This result is in line with previous findings that state that the collection of patient reported measures could lead to a change in their relationship and communication with patients (Murante et al. 2014). The paper therefore provides insights on the role that physicians play in the systematic collection of patient reported measures. Results are aligned with previous findings which show that in order to overcome the perceived effort and foster the routine collection of patient reported measures, at least by using the model chosen by Tuscany, health professionals should be properly informed on the overall aim of the project and that a little effort from their side could produce deep advantages in terms of care quality, patient satisfaction and outcomes (Gonçalves Bradley et al. 2015; Luxford, Safran, and Delbanco 2011). This little effort required relies on the assumption that physicians are knights and given the undoubtable benefits that the collection of patient reported

measures brings, they would all behave altruistically and adhere to the project. However, in practice significant differences emerged in their degree of commitment, as some physicians acted as knaves and were not keen to make the little effort as they did not perceive any benefit for themselves.

Chapter 2

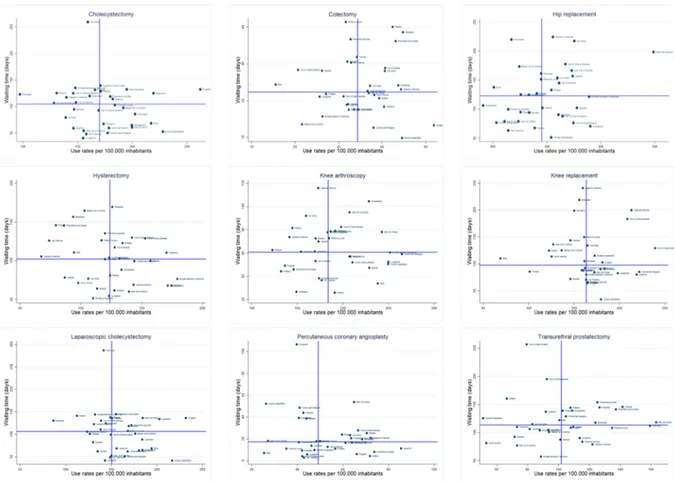

Chapter 2 shifts the focus from the individual to the operational level, aiming at carrying out a performance management and improvement study at the meso level, by investigating two widespread phenomena that often occur in the provision of healthcare services, lead to dissatisfaction among citizens and pose relevant policy challenges: the existence of geographical unwarranted variation and the presence of waiting times. The study aims to inquire the relationship between the two and to provide management tools to tackle unwarranted variations by studying the provision of nine main elective surgery services in Tuscany (knee replacement, hip replacement, percutaneous coronary angioplasty, hysterectomy, cholecystectomy, colectomy, transurethral prostatectomy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and knee arthroscopy). Findings showed that there is a 2/3-fold variation across the 34 districts, for all the procedures analysed, both in terms of waiting times and treatment rates. However, variations have revealed to be heterogeneous across the nine procedures; indeed each district registered high rates and waits for some procedures, and low rates and waits for other. A more detailed version is provided in Table 2 of chapter 2, but the example is that a district has a low

treatment rate and low waiting time for knee replacements, while facing short waits and high rates for colectomy. The same reasoning can be applied to all the districts in Tuscany. As waiting times arise from the unbalance between the demand and the supply, in other economic sectors, where the latter is elastic to the former, the strategies to shorten them often foresee supply side interventions. In healthcare instead, simply increasing rates of surgery does not reduce waiting times. As previous studies showed that the healthcare sector is different and supply often drives the demand (Berwick, Nolan, and Whittington 2008a; Grytten and Sørensen 2001; Sekimoto and Ii 2015), we decided to investigate the relationship between waiting times and treatment rates for elective surgery services in Tuscany (RQ1).

RQ1: Is there a relationship between waiting times and treatment rates for elective surgery services in Tuscany?

The results show that, for all the procedures, there is no straightforward relationship between waiting times and treatment rates, but districts are scattered on a plot without any pattern, indicating that the demand for elective surgery services is inelastic to the supply, as already demonstrated in previous studies (Martin and Smith 1999; Riganti, Siciliani, and Fiorio 2017). Moreover, the heterogeneity across procedures that we found for all health districts means that the problem is more complex and the research of solutions must be done by providers procedure by procedure, as the underlying causes

for variation and the strategies to tackle it vary. The intuitive thinking adopted from the private industrial sector would suggest that in order to shorten waiting lists an effective strategy would mean strengthening the supply by allocating additional resources (Bellan 2004; Waddell 2004; Dimakou, Dimakou, and Basso 2015; Siciliani, Moran, and Borowitz 2014); however, in healthcare, the presence of the so-called ‘supplier-induced demand’ makes so that most of the times the additional resources shorten waiting lists for a short period of time, while in the long run the increased capacity is offset by an increased demand for services (Auster and Oaxaca 1981; van Dijk et al. 2013; Richardson and Peacock 2006; Rice and Labelle 1989; Riganti, Siciliani, and Fiorio 2017; John E. Wennberg, Barnes, and Zubkoff 1982). Indeed, these solutions have failed to radically shorten waiting times at a system level in the long run (Appleby et al., 2005; Bettelli, Vainieri, & Vinci, 2016). Drawing on Wennberg’s taxonomy of geographical variation (John E. Wennberg 1999) and on previous findings on waiting times management in healthcare (Siciliani and Hurst 2005a; Siciliani, Moran, and Borowitz 2014; Riganti, Siciliani, and Fiorio 2017), the study inquires whether there are any tools that have proven effective for the management, or in this case the reduction, of both waiting times and unwarranted medical practice variation for elective surgery services (RQ2).

RQ2: What are the effective tools to tackle both long waiting times and geographical unwarranted variation for elective surgery services?

By applying the method proposed previously for the management of diagnostic services (Nuti and Vainieri 2012), the chapter provides a conceptual framework of analysis by

building a waiting time - treatment rate matrix where 4 quadrants are identified by tracking the median lines and therefore each district is located in a quadrant. The tool presented supports managers and policy-makers in making decisions over elective surgery services delivery as the causes, and consequently the strategies to be pursued, differ from quadrant to quadrant and simply increasing rates of surgery does not reduce waiting times. In fact, the study concludes that just in one of the quadrants (when there are low treatment rates and long waiting times), if inefficiencies are not in place, the policy-makers could allocate additional resources (e.g. longer operative room hours, more physicians, etc.) in order to obtain a reduction of waiting times. In the remaining 3 quadrants instead, additional capacity would not shorten waiting times and other solutions should be considered. Therefore, instead of increasing rates of surgery that might turn ineffective to reduce waiting times, policy-makers should work on the appropriateness of these procedures (understanding whether the need is correctly identified), on the efficiency and the allocation of resources. In conclusion, the argument of the study is that in order to manage a complex problem in healthcare management, such as the existence of long waiting times and unwarranted geographical variation in the delivery of elective surgery services, simply increasing rates of surgery might be both ineffective in reducing waiting times and harmful as it might increase the extent of geographical unwarranted variation. Instead, policy makers should consider the appropriateness of these procedures and as rates and waiting times proved heterogeneous across procedures, policies designed to effectively reduce unwarranted

variation and shorten waiting times at a regional level should focus on the reallocation of resources both among procedures within a district and between districts.

Chapter 3

Chapter 3 presents an analysis of performance management at the macro level through the 10-years longitudinal cases of two Italian regions (Lombardy and Tuscany) that pursued different strategies to drive performance improvement. The chapter aims to explore the effectiveness of reward schemes by investigating the effect of Pay-for-Performance (P4P) programs on regional healthcare performance (RQ1).

RQ1: Are P4P mechanisms effective tools for regional healthcare performance management systems?

The research question is an attempt to add knowledge to a body of literature that so far showed mixed results: indeed some studies proved P4P is effective in driving healthcare performance improvement (Scott et al. 2011), some other studies showed a negative effect in certain contexts (Frick, Prinz, and Winkelmann 2003; Green and Heywood 2008), while other showed no significative effect (Glasziou et al. 2012; Mannion and Davies 2008).

Our findings suggest that paying more has a positive, though limited, impact on performance improvement in public healthcare organisations. The study therefore proceeds to investigating which are the characteristics that drive the effectiveness of performance reward schemes in healthcare (RQ2).

RQ2: What are the characteristics that drive the effectiveness of performance reward schemes in healthcare?

We focused on five key characteristics: 1. Whom to reward: managers or providers?; 2. What exactly to reward?; 3. How should rewards be granted?; 4. How much to reward?; 5. How many targets should be set and assessed.

Findings suggest that what matters is the clear definition of what exactly to reward, meaning that goals should be well defined, measurable and challenging . Results are in line with the goal-setting theory, according to which the highest levels of performance are usually reached when goals are both difficult and specific (Locke 1996; Locke and Latham 2013). Moreover, the study debates that performance improvement might be obtained by combining multiple governance tools of performance evaluation systems, such as the systematic use of clinical indicators, continuous benchmarking and the transparent disclosure of results because when goals are aligned among the healthcare professionals, it is possible to act on the reputational lever to drive performance improvement (Bevan, Evans, and Nuti 2019). In conclusion, the study presents an

argument of the fact that financial rewards can drive regional healthcare performance improvement as they proved effective in driving extrinsic motivation, but their effect is limited. We found a significant difference in the performance improvement between Tuscany and Lombardy; the first experienced a consistent improvement, while the latter improved less. The drivers of such difference in the performance improvement between Lombardy and Tuscany stand in the implementation strategy of P4P and in the use of other governance mechanisms. Indeed Tuscany made an extensive use of clear, measurable and challenging indicators, while in Lombardy performance was assessed on the basis of less quantitative and challenging indicators (indeed 90% of the times targets were achieved). Moreover, the Tuscan strategy relied on benchmarking and public disclosure of results in order to obtain the obtain the engagement of health professionals by leveraging also on other motivators, such as reputation, rather than pay. Therefore the implications of the study are that P4P can drive performance improvement as they act on the external motivation of health professionals, but regions that want to get out the most of such programs should jointly put in place governance mechanisms such as using measurable indicators, setting challenging targets, systematic benchmarking and public disclosure of results to activate the virtuous circle of performance improvement.

The main characteristics of the studies included in this dissertation are summarised in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Overview of the dissertation chapters

Chapter 1 2 3

Title of the paper Implementing successful systematic Patient Reported Outcome and Experience Measures (PROMs and PREMs) in robotic oncological surgery - the role of physicians

Decision making tools for managing waiting

times and treatment rates in elective surgery Insights on the effectiveness of reward schemes from 10-year longitudinal case studies in 2 Italian regions

Authors Lungu D.A., De Rosis, S., Pennucci F. Lungu D.A., Grillo Ruggieri T., Nuti S. Vainieri M., Lungu D.A., Nuti S. Journal

BMC Health Services Research BMC Health Services Research International Journal of Health Planning and Management

Status Published Published Published

Type of research Empirical study Empirical study Empirical study

Research questions o What is the role of physicians in the adoption and successful implementation of routine collection of patient reported measures and what are the determinants of their motivation? o What is the impact of patient reported measures on physicians and healthcare organisations?

o Is there a relationship between waiting times and treatment rates for elective surgery services in Tuscany?

o What are the effective tools to tackle both long waiting times and geographical unwarranted variation for elective surgery services?

o Are P4P mechanisms effective tools for regional healthcare performance management systems?

o What are the characteristics that drive the effectiveness of performance reward schemes in healthcare?

Data/cases Data from the Tuscan PROMs and PREMs Observatory and in-depth interviews with all robotic oncological surgeons

2016 data from Tuscany administrative flows on

nine elective surgical procedures 2005 - 2015 publicly available performance data and grey literature such as regional reports

Methodological approach Mixed-method (descriptive statistics and

Chapter 1. Implementing successful systematic Patient

Reported Outcome and Experience Measures (PROMs and

PREMs) in robotic oncological surgery - the role of physicians*

Background:

Patient Reported Outcome and Experience Measures (PROMs and PREMs) play an increasingly important role in monitoring performance regarding the oncological path. Several studies have revealed the significant role that this kind of measures could have both in terms of quality of care and in terms of research, but for the moment little is known about the role of physicians in the adoption process and the impact that the introduction of systematic patient reported measures has on their performance. The aim of this study is to describe the case of five hospitals a year after the adoption of PROMs and PREMs for robotic oncological colorectal surgery in Tuscany and to investigate how the clinicians can impact the process of implementation and the efficacy of such measures.

* The chapter has been published as Lungu DA, Pennucci F, De Rosis S, Romano G, Melfi F. Implementing successful systematic Patient Reported Outcome and Experience Measures (PROMs and PREMs) in robotic

Methods:

The methodology follows a three-step mixed approach. First, we computed the number of patients enrolled and response rate to the pre-operative questionnaire for the 4 robotic centers involved in the project. Second, 8 months after the kick-off, we administered a survey to physicians who are responsible for the enrollment of patients in order to collect feedback regarding the main pros and cons of the project. Third, we conducted in-depth interviews 6 months later to assess the impact that the systematic collection of PROMs and PREMs had on their performance.

Results:

A total of 143 patients (out of 356) who underwent robotic oncological colorectal surgery were enrolled over the first year: 60 in hospitals A and B, 16 in hospital C and 7 in hospital D. Response rates to the pre-operative questionnaire was on average 52.86%, ranging from 42.9% in hospital D to 63.2% in hospital A. From the qualitative data some useful elements to shed light on the quantitative evidence emerged. Above all, physician’s personal motivation to better treat patients and the possibility to use data for research purposes proved to be the essential factors for their engagement and the successful implementation of patient reported measures.

Conclusions:

Our study shows that physicians play a key role in the adoption of systematic PROMs and PREMs. Indeed, the higher the level of physicians’ engagement, the higher the process success, both in terms of number of patients enrolled and response rates. Moreover, the collection of patient reported measures may become part of physicians’ daily practice and could lead to a change in their relationship and communication with patients (Murante et al. 2014), as long as clinicians become keen to have their job reviewed and are not afraid to be evaluated by their patients. Further research is needed to test whether physician-patient communication improves after PROMs and PREMs data had been shared and discussed among the physicians.

Background

After that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the da Vinci Surgical System in 2000, the past two decades have been characterised by the increased diffusion of such systems and the manufacturer’s data show that as of September 30, 2017, there was an installed base of 4271 units worldwide, of which more than 60% in the US, followed by Europe and Asia (Mirheydar and Parsons 2013; Schreuder and Verheijen 2009; Tsui, Klein, and Garabrant 2013). Although initially it was employed mainly for urologic procedures (namely radical prostatectomy), the evolution of both the surgical technique and the technology made possible the introduction of robotic surgical systems to a broader range of surgical specialties: cardiac, colorectal, general surgery, gynaecology, head and neck, and thoracic surgery.

At the same time there has a rise in the oncological conditions that pose a great challenge to healthcare systems due to their increasing prevalence and expenditure. Indeed, cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide behind cardiovascular diseases. In 2015, there were 17.5M cancer cases worldwide, an increase by 33% with respect to 2005, and 8.7M deaths (Wang et al. 2016; Fitzmaurice et al. 2017). However, the recent developments in personalised medicine, the continuous progress of cancer research and the advance of mini-invasive surgical techniques have raised hope for patients and considerably improved cancer survival (Hanahan 2014; Douglas R. Lowy 2010; Shulman et al. 2019; Jørgensen et al. 2019). At the same time, the increasing cost of cancer treatments lead to ongoing debate regarding both the equity and the affordability of care from individual and societal perspectives (Bell et al. 2008; Meropol et al. 2009).

The continuously growing number of oncological procedures delivered by the means of robotic surgical systems and the controversial debate regarding their cost-effectiveness with respect to traditional surgery led to the need of performance measurement systems to evaluate the effects of treatments, including surgery, able to go beyond the traditional clinical view of mortality and complications rates (Guldberg et al. 2013; Iyer et al. 2013; Kotronoulas et al. 2014; Soreide and Soreide 2013). Beside the objective outcome measurements evaluated by clinicians, there are also subjective measures such as patient satisfaction and quality of life and patient experience. The latter, and more specifically Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs), have received increased attention as a useful tool to evaluate the effects of treatments and the outcomes of patients who underwent robotic oncological surgery, as the importance of the patient’s perspective on disease impact has been increasingly recognised (S. Marshall, Haywood, and Fitzpatrick

2006). PROMs data have been initially introduced in clinical trials in order to integrate the clinical data with the people’s subjective perception of their health status and health-related quality of life (J. Dawson et al. 2010). Most studies present the results of clinical trials and focus on radical prostatectomy and use PROMs as a comparative tool between the outcomes achieved by cohort of patients operated by the open, laparoscopic or robotic technique (Novara et al. 2012; WEI et al. 2000; Antonelli et al. 2019; MacKenzie et al. 2019), while in literature the evidence of systematic collection of patient reported measures is still limited. However, the intrinsic characteristic of oncological diseases where treatment is not a one-shot event but a pathway that moves across the different care settings requires the design of performance measurement tools able to overcome the “silo-vision” and evaluate performance results of the whole care pathway (Nuti et al. 2017, 2018). In this direction, PROMs for oncological patients should cease to be limited to clinical trials and their collection should be systematic and investigate outcomes and quality of life throughout the entire pathway from diagnosis, to surgery, therapy and follow-up phase. One of the few examples of initiatives to foster systematic approach towards patient reported measures is the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) that has defined a standard set of patient reported indicators for 28 conditions, including five oncological conditions (OCs): colorectal, breast, lung, localised and advanced prostate cancer.

Beside their use in clinical trials, PROMs have been promoted as a means of enhancing patient involvement in the decision-making process, improving communication between health professionals and patients and improving both detection and monitoring of symptoms (J. Dawson et al. 2010; Greenhalgh, Long, and Flynn 2005; Snyder et al. 2012).

A different use for PROMs is the provision of evidence of the performance and quality of healthcare services (Black 2013), without a feedback system at the level of the individual patient. The best known example of routine collection of PROMs data at a system level is the case of the English National Health System (NHS), which in 2009 has started the collection of data before and after surgery for four elective procedures: hip replacement, knee replacement, varicose vein and groin hernia (Varagunam et al. 2014; Rolfson et al. 2011; Peters et al. 2014). Despite since September 2017 the data collection has been ceased for varicose vein and groin hernia surgery, the experience of the English NHS led healthcare systems worldwide to express growing interest in implementing systematic collection of PROMs.

The English NHS experience has proven that the routine collection of PROMs is in certain circumstances possible. Although the main aim has been to evaluate healthcare performance and punishments have been put in place for low performers, it is important to mention that surgeons were not involved in the collection process but were provided with individual level outcome data in order to foster comparisons and reduce variation. Still, literature reports no evidence that the availability of data had any impact on clinicians’ performance. In this context, understanding which are the main barriers or facilitators they face in the implementation and use of patient reported measures becomes extremely relevant for the success of such programmes.

International literature lists several problems and barriers for the systematic collection of PROMs, ranging from the lack of time, lack of training, doubts about the tool’s validity and reliability, the complexity and the interpretation of measures, language translation, cultural

adaptation, cognitive impairment of patients and difficulties of analysing data and dealing with missing values, lack of structure and staff to assist data collection, time consuming and irrelevance for patients (Bausewein et al. 2011; Dainty et al. 2017; Peters et al. 2014; Hanbury 2017; Valier et al. 2014).

Focusing on OCs, both health professionals (Abernethy et al. 2010) and patients (Hilarius et al. 2008; Judson et al. 2013; Erharter et al. 2010) tend to respond positively to the idea of routine collection of PROMs. Previous studies have found positive relationships between the collection of PROMs and patient satisfaction (Chen, Ou, and Hollis 2013), perceived quality of care (Berry et al. 2011; Basch et al. 2007), patient outcomes (Velikova et al. 2004), symptom management (Kallen, Yang, and Haas 2012) and acceptability (Kallen, Yang, and Haas 2012; Hilarius et al. 2008). On the physicians’ side, the collection of PROMs proved to have a positive impact on patient-clinician communication (Chen, Ou, and Hollis 2013; Luckett, Butow, and King 2009), contribute to a better detection of symptoms and improve their monitoring (Snyder et al. 2012; Erharter et al. 2010; Chapman et al. 2008), may support clinical decision making (Basch et al. 2007; Nicklasson et al. 2013; Lynch et al. 2011), while studies did not find a significant impact of PROMs implementation on the length of the clinical encounter (Berry et al. 2011; Engelen et al. 2012; Velikova et al. 2004; Basch et al. 2007).

The mentioned above positive benefits could depend, at least partly, on physicians’ engagement in the collection process. Given the trust that patients place on them, we aim to investigate what is the role they play in the success of the routine adoption of patient reported measures, as they can influence patient participation and response rates.