ContentslistsavailableatSciVerseScienceDirect

Comptes

Rendus

Palevol

www . s c ie n c e d i r e c t . c o m

Human

palaeontology

and

prehistory

Blades,

bladelets

and

flakes:

A

case

of

variability

in

tool

design

at

the

dawn

of

the

Middle–Upper

Palaeolithic

transition

in

Italy

Lames,

lamelles

et

éclats

:

un

cas

de

variabilité

dans

la

réalisation

de

l’outillage

à

l’aube

de

la

transition

Paléolithique

moyen–supérieur

en

Italie

Marco

Peresani

∗,

Laura

Elisa

Centi

Di

Taranto

UniversitàdiFerrara,DipartimentodiStudiUmanistici,SezionediPreistoriaeAntropologia,CorsoErcoleId’Este,32,44100Ferrara,Italy

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received1stDecember2012 Acceptedafterrevision9April2013 Availableonline13June2013 PresentedbyYvesCoppens Keywords: MiddlePaleolithic Behaviour Levallois MIS3 Italy

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

NeanderthalsleftdiversesetsofculturalevidencejustbeforetheMiddle–UpperPalaeolithic transitioninEurope.Withinthisevidence,theproductionoflithicimplementsplaysa keyroleindetectingpossibleaffiliations(orlackthereof)withthetechno-complexesthat occurredduringthefewmillenniabeforethelarge-scalespreadoftheProto-Aurignacian. ThiscrucialphasehasalsobeenrecordedintheNorthofItaly,wherearound44–45kycal BP,thelastNeanderthalswerestillusingtheLevalloisknappingtechnique,incommon withthetechnologyadoptedatseveralsitesinthecentralMediterraneanregion.Asimilar pictureisseenattheGrottadiFumane,whichprovidestheevidencepresentedinthis paper.Theproductiontechnologyemployedproduceddifferentlevelsofvariabilitywith respecttotheproductionofblades,sometimespointed,andtheuseofrecurrentcentripetal flakingattheendofthereductionsequence,inadditiontobladeletandDiscoidalvolumetric structures.Thisvariabilitydoesnotoutweighthedominanttendencytowardstheuseof elongatedLevalloisblanksandotherby-productsforshapingintobasicretouchedtools suchassimpleorconvergentscrapersandpoints.Abreakfromthisapparentlywell-rooted useoftheunipolarLevalloismethodisrecordedintheUluzzianwhere,instead,flakesand coresweremadeusingthecentripetalmodality.

©2013Académiedessciences.PubliéparElsevierMassonSAS.Tousdroitsréservés.

Motsclés: Paléolithiquemoyen Comportement Levallois MIS3 Italie

r

é

s

u

m

é

LesNéanderthaliensontlaissédiversessériesdepreuvesdeculture,justeavantlatransition Paléolithiquemoyen–PaléolithiquesupérieurenEurope.Parmicespreuves,laproduction d’objetslithiquesjoueunrôleclédansladétectiond’affiliationspossibles(oud’absence d’affiliation)avecles techno-complexestrouvésdurantles quelquesmillénairesavant l’expansionàgrandeéchelleduProto-Aurignacien.Laphasecrucialeaétéenregistréeau Norddel’Italieoù,auxalentoursde44–45kacalBP,lesderniersNéanderthaliensutilisaient encorelatechniquededébitageLevallois,enmêmetempsquelatechniqueadoptéesur différentssitesdelarégionméditerranéennecentrale,enparticulieràlaGrottadiFumane, quifournitlapreuveprésentéedanscetarticle.Latechniquedeproductionutiliséeapour conséquencedifférentsniveauxdevariabilitéencequiconcernelaproductiondelames quelquefoispointuesetl’usaged’unécaillagecentripèterécurrentàlafindelaséquencede réduction,outrelesstructuresvolumétriquesDiscoïdesetlamellaires.Cettevariabiliténe l’emportepassurlatendanceàl’utilisationd’ébauchesdetailleLevalloisallongéesetautres

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:[email protected](M.Peresani).

1631-0683/$–seefrontmatter©2013Académiedessciences.PubliéparElsevierMassonSAS.Tousdroitsréservés.

sous-produitspourfabriquerdesobjetsretouchés,telsquegrattoirsetpointessimplesou convergents.Uneinterruptiondecetusage,apparemmentbienrodé,delaméthode unipo-laireLevalloisestenregistréedansl’Uluzzien,oùdeséclatsetnucléusontétéconfectionnés enutilisantlamodalitécentripète,àlaplacedelaprécédente.

©2013Académiedessciences.PubliéparElsevierMassonSAS.Tousdroitsréservés.

1. Foreword

Research on human behaviour around the Middle–UpperPalaeolithictransitionin Europeinvolves severaldifferentscientific domains,each of which pro-vides,atvariouslevels,itscontributionindetectingthe bio-culturaldistancebetweenNeanderthalsand Anatom-icallyModernHumans(Harrold,2009;Lalueza-Foxetal., 2011;VanAndeland Davies,2003).Withinthesefields, a first-order rolein the investigationofcognition, skill, handedness and economic strategies in terms of land-scape ecology is performed by the study of lithic tool design and the organization of lithic tool production (Bird and O’Connell, 2006; Kuhn, 1994; Uomini, 2011). Acrosstheintervalconsidered,theexaminationoflithic techno-complexeshaspermittedustodiscover substan-tialdifferencesbetweenthefinalMousterianperiod,the transitional complexes and the full affirmation of the Aurignacianperiod.

AsinotherEuropeanregions,theMP–UPtransitionwas amulti-facetedperiodintheItalianpeninsula,where sub-stantialchangeoccurredacrossmanyaspects ofhuman behaviour and material culture (Boscato and Crezzini, 2012;BroglioandGurioli,2004;D’Erricoetal.,2012;Kuhn andBietti,2000;Mussi,2001;Peresani,2011;Ronchitelli et al., 2009). This has encouraged dispute, even if not stronglysupportedbydata,overthepresumedtaxonomic coherenceorlackthereofofsometechno-complexes(Bietti and Negrino, 2007; Gioia, 1990; Riel-Salvatore, 2009), and over enhancingmodels of mobility and settlement dynamics (Riel-Salvatore and Barton, 2004).The recent attribution of the Uluzzian techno-complex to thefirst spread ofAMH (Benazzi etal., 2011)seemstoindicate anearlierreplacementofNeanderthalsbyAMH(Moroni etal.,inpress).This,inturn,leadstonewimplicationsin thecomparisonofcognitionandbehaviourbetweenthe twospecies.Ourattentionshouldthenbefocusedonthe lastbehaviouralexpressionsoftheautochthonous popula-tion.Thecomparisonbetweensuchexpressionsassumesa greaterimportanceincaseswherethetemporaldistance isshort.

InNorth-EastItaly,someknownsequences(Grottadi Fumane,RiparoTagliente,GrottadiSanBernardino,Riparo delBroion,GrottadelRioSecco)mightpermitthiskindof evaluation,butthelackofchronometricdataorthescarcity ofartefactscouldbeanobstacletotheireventualvalue inaddressingtheissue.Onecaseofashorttimehorizon occursatGrottadiFumane,wherethepresenceofafinely stratifiedsequencecomprisingarecently-analysedgroup oflayers,A5,A5+A6,A6(tobereferredtoasA5–A6from hereforwards),offersampleevidenceofNeanderthal tech-nicalexpressions,somuchsoastobecometheobjectof thepresentstudy.Thiscave,onthesouthernfringeofthe

VenetianPre-Alps,hasbeensystematicallyexcavatedsince 1988andowesitsimportancetothe12mthickLate Pleis-tocenestratigraphicsequence(Martinietal.,2001)which includestheMP–UPtransitionspanningthefinal Mous-terian,theUluzzianandtheAurignacianperiods(Broglio et al., 2005,2009;Higham et al.,2009; Peresani, 2008; Peresanietal.,2008,2011).

2. TheA5–A6complexanditsculturalcontent

ThestratigraphiccomplexofthelayersA5–A6covers 58m2atthecaveentranceandhasbeenexcavatedinmany different sectorssince 1988 and moreextensively from 2006to2008.ItissandwichedbetweentheUluzzianlayer A4aboveandthesterilelayerA7below.Thisfinelylayered sedimentarysuccessionmade offrost-shatteredbreccia, Aeoliansiltandsandsismarkedlydifferentinthedensity andnumberofanthropogenicsignatures(bones,withsigns ofanthropicmodification,hearths,flintflakes)asa con-sequenceofchangesinsettlementdynamics.Athin,flat charcoallayer(A5)overliesaloosestonylayerwithloamy finefraction(A5+A6).Below,adarklayer(A6)is recogniz-ableoverthewholeexcavatedzone,withconstantdense indications ofanthropogenicactivity.Combustion struc-turesareplentifulinA6andthereareasmallernumber inA5andA5+A6(Peresanietal.,2011).The chronomet-ricrefinementofferedbythe14CdataputsA5at43.6–43.2 kyBPandtheboundarywiththeUluzzianlayerA4above at43.6–43.0kyBP(Highametal.,2009).Red-deer, ungu-late andsomecarnivorebonesallbear signsofcultural modification(Peresanietal.,2011).

The lithic industries yielded groups of flint flaked artefacts, with highest frequency in A6 and lowest in A5, with a total of around 6,000 with a mod-ule (length+breadth)≥4cm. Several flint types were exploited,albeitwithvaryingfrequency.Atafirstglance at their texture, structure, colour and the morphology of the exterior surface, the flints were obtained from theLateJurassictoMiddleEocenecarbonaticformations in thewestern Lessini Mountains. Maiolica and Scaglia Rossa(Cretaceous)havethehighestfrequencies,buthigh frequenciesarealsoshownbytheTertiarycarbonatic sand-stones, Scaglia Variegata (Cretaceous) and its varieties, whiletherearelowerfrequenciesfromooliticlimestone (Jurassic)andotherformationsofTertiaryage.Theselithic assemblagesshowthevarietyofrawmaterialsexploited inthisregion,whereprovisioningmayhaveoccurredat arangeof5–10kmfromthesite.Flintisalsocontainedin loosecoarsestreamorfluvialgravels,slope-wastedeposits, andsoils:forthisreason,theybecameamajorresource to be exploited close to the cave.There was also very occasionalexploitationofoldpatinatedartefactscollected as potential cores from elsewhere. Indeed, flaking was

Table1

General count of samples, with Levallois end-products and by-product(seeTable2forexpandedlist),bladelets,Discoidflakesand Pseudo-Levalloispoints,otherflakes(Kombewa-typeflakes,pieces inde-terminable due to invasiveretouching), indeterminablefragmentary flakes,indeterminableproximalfragmentsofflake,Levallois,bladelet andothertypesofcores,indeterminablefragmentarycores.Notethat A5countincludespiecesfromlayerA5+A6(seeexplanationinthetext). Tableau1

Décomptegénéraldel’échantillon:produitsfinisetsous-produits Leval-lois(voirTableau2pourunelisteexhaustive),lamelles,éclatsdiscoïdeset pointespseudo-Levallois,autreséclats(éclatsdetypeKombewa,pièces indéterminablesenraisondelaretoucheenvahissante),éclats fragmen-tairesindéterminables,fragmentsproximauxd’éclatindéterminables, lamelles Levalloisetautrestypesde nucléus,nucléus fragmentaires indéterminables.Ànoterquelesdécomptesdel’A5incluentlespièces duniveauA5+A6(cf.explicationdansletexte).

A5 A6 n % n % Flakes Levallois end-product 101 14.0 132 14.5 Levalloisby-product 310 42.8 375 41.0 Bladelet 9 1.2 8 0.9 Discoidflake 7 1.0 10 1.1 Otherflake 33 4.6 39 4.3 Indeterminable fragmentaryflakes 194 26.8 248 27.1 Indeterminable proximalfragments offlake 53 7.3 65 7.1 Cores Levallois 6 0.8 18 2.0 Bladelet 1 0.1 2 0.2 Discoid 1 0.1 4 0.4 Other 7 1.0 8 0.9 Indeterminable fragmentarycores 2 0.3 5 0.5 Total 724 100.0 914 100.0

performedoneverytypeofrawmaterial,regardlessofits

mechanicalpropertiesorthemannerinwhichtheflintwas

introducedintotheproduction-manufacturesystem.

3. Materialsandmethods

Theartefactsanalyzedinthepresentstudyamountto

atotal of1629witha module≥4cm (Table1).Givento

thequantityoflithicsrecoveredduringrecentfieldwork, this numbercanbeconsidereda reliablerepresentative sampleofsuchpopulation(Centi,2008–2009;DiTaranto, 2009–2010).Studiesinprogressontherestofthe assem-blage confirm the technologicalvariability identified at this first step. They show fresh surfaces over all faces andretouchededges,althoughnaturalmodifications rang-ingfromthemarginaltotheinvasiveoftheunmodified andretouchededgesaffect6–8%ofthetotalassemblage. Thespatialdistributionofthesealterations,basedonthe degreeofedgemodification,becomesdenserprogressively towardstheinnercave.

To reconstruct the reduction sequences, morpho-technicalandmorpho-metricanalyseswerecarriedouton thecoresandthecompletedblanks,whicharethemost sig-nificantby-products(intermsoftheirtechnologicalrole), aswellassomerefittedpieces.AsconcernstheLevallois method,theconceptualandanalyticalapproachesofthe

Table2

TabulationofLevalloisby-products,end-productsandcores.NotethatA5 countincludespiecesfromlayerA5+A6(seeexplanationinthetext). Tableau2

Tableaudessous-produits,produitsfinisetnucléusLevallois.Ànoterque lesdécomptesenA5incluentlespiècesduniveauA5+A6(cf.explication dansletexte). Levalloisproducts A5 A6 n % n % By-products Corticalflake 116 27.8 121 23.3 Platformrenewal 36 8.6 49 9.5 Predeterminingflake 114 27.4 144 27.8 Corerepairing 17 4.1 13 2.5 Flakingaccident 27 6.5 48 9.3 End-products Unipolar 64 15.4 78 15.0 Centripetal 24 5.8 40 7.7 Indeterminable 9 2.2 9 1.7 Cores Unipolar 1 0.2 4 0.8 Centripetal 2 0.5 3 0.6 Othera 4 1.0 5 1.0

Indeterminablefragmentarycores 2 0.5 4 0.8 Total 416 100.0 518 100.0

aLevalloiscoreswithorthogonalpattern,cores-on-flake,coreswith

doubleflakedface.

presentstudyhavebeeninspiredbytheworkofE.Boëda (1994)andhavealsotakeninconsiderationbroadercriteria fordefiningLevalloispredeterminedproducts(Grimaldi, 1996;Guette,2002),previouslyusedinthecontextofthis region(Peresani,2001,2012).Technologicaldescriptions ofbothmajorandminorlithicproductionsequencesand thekeytypologicalfeaturesofretouchedblanksaregiven below.

4. Bladesandflakes:Levalloisproduction

AlmostallstagesoftheLevalloisreductionsequenceare representedherebytheflakeswhicharemostlytheresults oftheinitialshapingofthecores,andthemaintenanceand re-preparationofLevalloiscores (predeterminingflakes, core-edgeremovalflakes,platformrenewal,core repair-ing),designed to eliminate imperfections and accidents (Table2).Corticalflakesarefairlyflatandelongated, result-ingfrom theexploitation of cobbles using theunipolar modality,followingparallelplanes.Over200Levallois end-productsreflectthetechnicalaimsthatwereenvisagedat initialreduction,andpursuedthroughoutthewhole pro-cessofexploitation,and alsoprovidegoodevidencefor recognizingoptionsandwaysofpredeterminingshapeand size.

Levallois production concerns a main reduction sequence managed through the unipolar recurrent method,butalsoinvolvesbranchingoutandotherlevels ofvariability:oneexampleisthemodificationtoexploit corticalflake-cores and a second case is the procedure tochangefromunipolar tocentripetaltowardsthefinal phase of core exploitation. In addition, technological variants and various predetermining devices have been identifiedwithinagivenmodality.

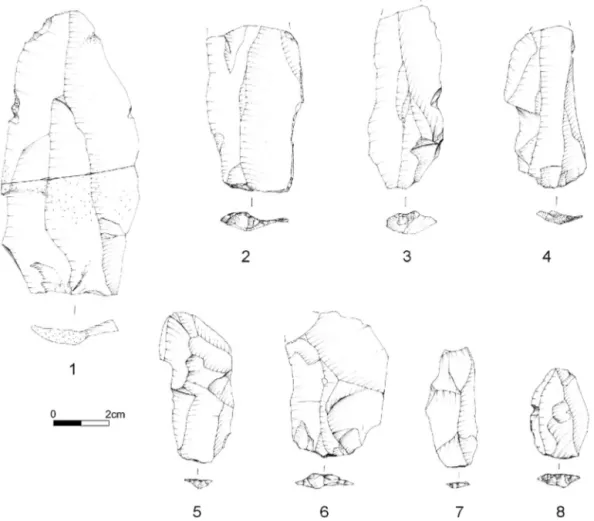

Fig.1. LevalloisbladesfromlayersA5(3,4),A5+A6(7),A6(1,2,5,6,8).Pieces5and6showtracesofserialdetachmentswithangledorientationwith respecttotheformerflakeaxis.

Fig.1. LamesLevalloisprovenantdesniveauxA5(3,4),A5+A6(7),A6(1,2,5,6,8).Lespièces5et6portentdestracesd’enlèvementsensérie,avecune orientationdifférenteparrapportàl’axeantérieurdel’éclat.

DrawingsS.Muratori.

4.1. Blademaking:unipolarflakingandvariants

Artefactsascribedtothisaimarethemostnumerous andrecordallthestepsofthereductionsequencethrough tothefinaldiscardingofthecores.

4.1.1. Initialstage

Duetothelackofunknappedorsemi-workedcobbles andofcoresdiscardedduringtheinitialstageof exploita-tion,thisoperationalstagehasbeenreconstructedfromthe examinationofnumerouscorticalflakes.Mostofthe com-pleteorpartlycompleteflakeslongerthan4cmarecovered withcortexfrom20%to100%,orhavelateralcortex.Butts aremostlyplainornaturallyflat,althoughfaceted,dihedral andpunctiformtypesincreasemoreandmoreascortex reduces.Thefeaturesoftheseblanksshowthattheir nat-uraldorsalfacesarefromregularlyconvexnodulesorflat fracturedsurfacesthatarearrangedinaregular morphol-ogy,sometimesrefinedbydetachinganaturalabruptside paralleltotheflakingaxis.Inaddition,theyaremuchlonger than wide, giving a markedly elongated blank-shape.

Moreover,thesefirstflakesareprovidedwiththin,long andregularedges.

Fromthesefeatures,itispossibletoinferwhich crite-ria led to the selection of the raw materials: nodules showing exteriorconvexitiesand plaquettes and blocks withexteriorfracturesarrangedtoshapelateralanddistal convexitiesthat suitedtherequirementsof predetermi-nation.Fromtheoutset,productionstartedfromaplain, ratherthanfacetedordihedralplatform,andwasexecuted so as to exploit the natural convexities or the delib-erately shaped form of the block after the removal of thelongestridges.Adifferentdeviceinvolveddetaching flakesobliquelyorperpendicularlytothemainaxisofthe blank.

4.1.2. Mainproductionandpredetermination

Following the preceding phase, the end-products demonstratethatthis modeofexploitation wasusedto optimizethecorevolumeuntiltheunipolarmodalitywas replaced or stopped. Once this was done, allowingthe avoidance of complex and expensive decortication and shaping oftheperipheralconvexities,thebasicrules of

Fig.2. ToolsonLevalloisbladesandonflakesfromlayersA5(2,3),A5+A6(1,5),A6(4,6–8):side-scrapers(1,7),side-scapersonbi-truncatedcortical blade(5,6),points(2–4);transversescraperonthinnedcorticalflake(8).

Fig.2. OutilssurlamesetéclatsLevallois,issusdescouchesA5(2,3),A5+A6(1,5),A6(4,6–8):racloirslatéraux(1,7),racloirslatérauxsurlamecorticale bitronquée(5,6),pointes(2,4);racloirtransversalsuréclatcorticalaminci(8)

DrawingsS.Muratori.

Levallois predetermination werefollowed, although the needforskillsincoremaintenancewerereducedtoa min-imum.

Overall,themethodinvolvedproductionofshort recur-rentseriesofelongatedandpointedblanks(Figs.1and2) struckfromasinglestrikingplatformandrarelyfroma second opposed one, which in most cases was faceted orkeptflat.Detachmentswerearrangedtotherightor left,indirector alternatesequencewiththefirststruck acrossthecentreofthecoresurface.Lateralconvexities

werereshapedbycore-edgeremovalflakes,Levallois core-edgeremovalflakesoraseriesofangledunipolarblades detachedfromanexpandedstrikingplatform.This plat-formwasadjoinedtothatusedinthefirstseries,sothat theirridgesconverged.Therefore,thesequenceof produc-tionproduced two groups of scars onthecoresurface, whichpartiallyoverlappedeachothertowardsthedistal endtoshapeone oftwolateralconvexities.In contrast, thedistalconvexitywasshapedbyacombinationofscars withdriving-ridges,butalsobydetachingoneflakeora

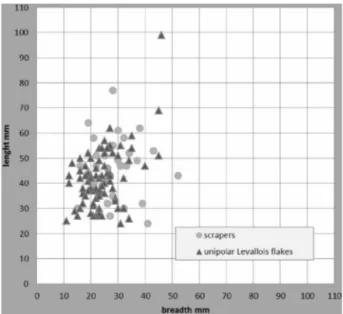

Fig.3.SizevaluesofunipolarLevalloisbladesandsimple+double scrap-ers.

Fig.3. ValeursdimensionnellesdeslamesunipolairesLevalloisetdes racloirslatérauxetbilatéraux.

seriesofsharp,moderatelyinvasiveflakesinanopposed or oblique directionto the Levallois flaking axis,or by usingthewarpedsurfacefromplungedcore-edgeremoval flakes.Therefore, predetermination onlyrequiredminor actions suchas detaching a few predetermining flakes, which economisedonraw materialin themaintenance of theconvexities. Otherpreparatory actions mayhave affectedthe proximalzone of theflaking surface when problematicirregularitieswereremovedortheergonomic outlineoftheplannedLevalloisblankwasimproved.These bladesmostlyrangebetween24and70mminlengthwith amaximumof99mm(av.42.1mm)andfrom11to46mm inbreadth(av.24.0mm),butmostofthebreadthvalues fallbetween15and29mm(Fig.3).Theelongationindexis 2.1,ascalculatedforatotalof45bladesgreaterthan4mm inlength.

ThescarcityofLevalloisflakes,core-edgeremovalflakes andotherartefactsperpendicularoropposedtotheflaking axis,suggeststhatthecreationofnewstrikingplatforms on core zones not adjoined to the main platform was rare. In suchcases, theproduction of a series of short, unipolar,stockyflakes–alternatingwithsomecore main-tenance–wasmadepossiblethroughthedetachmentof core-edgeremovalflakes fromtheopposed platformor thelateralsidesat90◦fromtheplatformusedforthelast predeterminedremoval.Maintenanceofconvexitieswas reducedtoaminimumandmainlyachievedthroughthe roleplayedbycore-edgeremovalflakes.

4.2. Flakemaking:centripetalflaking

Thismethodwasonlyusedtowardstheendofunipolar reductionsequences.Amongthereasonsworth consider-ingforthischangeare:

• corereduction.Theprogressivereductionthatthe unipo-larcoreunderwentledtoeitherarestrictioninthesizeof end-productsoracompromiseintheirmorpho-technical features,especiallytheiredgesandsizeratios;

• unipolarvariation.Theflakeaxisswitchingfrom unipo-lartoorthogonalmadethecoreassumeoutlinescloseto centripetal;

• flakingaccidents.Amongtheflakesstruckforremoving hingedscarsitispossibletonotethatorthogonaland multidirectional patterns clearly prevailed over other forms.Theaxisoftherepairingflakecrossedatavariable angletheaxisofthehingedscar,sometimessub-parallel tothelip,butmoreobliquelyafteranewplatformwas adoptedoranadjoinedplatformenlarged.

Thincentripetalflakesdisplayapolygonalorfan-like outlinewhenthecore-edgewaspartiallyremoved. Detach-mentoccursclockwiseorcross-crossedandcorevolumes were poorly maintained. The same holds for the con-vexities,whose maintenancewasextremely limitedand sometimesoccurred betweentwo end-productsor as a short series of flakes. Nevertheless, thecombination of core-edgeremovalswithcentripetalflakeswasseemingly uninterruptedandledtohighnumberofblankspercore, butalowdegreeofmetricandmorpho-technical standard-izationforfunctionaledges.Flakesaresmall,notexceeding 40mminlength.

From the reconstruction of the core operational schemesandexaminationoftheseflakes,ithasbeen pos-sibletoinferthatplatformswerecarefullyprepared,and extendedaroundalmostthewholeperimeter.Production stoppedasaresultofthevolumereductionasmuchasthe usualflakingaccidentssuchashingingorplunging.Noneof thecoreswerediscardedduetoincipientfractures,voids orotherelementsthatwouldrevealpoorlyselectedraw material.

4.3. Levalloisflakesfromflake-cores

Numerousflakeswereproducedfromtheexploitation ofby-products.Theprocedurerequiredtheremovalofthe bulbbymeansofasinglelateralblowortheshapingofthe peripheralregiontofacilitateuni-orbi-polarexploitation. Inthislattercase,thepredetermination,asshownbyfairly complex operationalschemes, wassystematic withone ormorescarsbeingadjacenttotheoriginalbulbandthe drivingridgebetweenthem.Thismorpho-technical lay-out,completedbythetrimmingofthecore-flakeplatform, sharessimilartechnicalcriteriawiththeLevalloisconcept (Dauvois,1981).Exploitingaplaneparalleltothatwhich dividesthedorsalandventralcore-flakefacesallowedthe extractionofthin,invasiveblanks.

5. Bladeletsfromlaminarvolumetricconcept

Theassemblagealsocontainsevidenceofbladelet pro-duction, through the exploitation of cortical ridges, as demonstratedbytworefittedpieces(Fig.4),andoffour bladeletcores-on-flake.

A core (fig. 4 n.6) was exploited onthe dorsal face of a large, possibly laminar, flake. Atleast ten bladelet

Fig.4.Bladeletproduction:refittedcorticalbladelets(1),primaryproducts(2–3),lateralbladelet(4),largebladelet(5),cores-on-flake(6–8). Fig.4. Productionlamellaire:lamellescorticalesremontées(1),produitsdepremièrequalité(2–3),lamelledeflanc(4),lamellelarge(5),nucléussur

éclat(6–8).

DrawingsS.Muratori1–5,7–8,G.Almerigogna6.

scarsoriginatefroma singlestriking platformmadeon a truncation at themiddle of the blank.Someof these areovershot,somearehingedandparallel:alltestifythe frontalreductionoftheoriginalvolume.Thedistalparts ofseveralotherlaminardetachmentsarevisiblealongthe leftsideandtestifytoanearlierexploitationoftheflake. Afewfinalelementsarerelatedtothemaintenanceofthe strikingplatform.

Asecondcore(fig.4n.7)wasexploitedontwofaces (AandB).Thefirstphasesawthepreparationofastriking platformandtheinitialexploitation(faceA)ofapartially preparedridgeformedbytheintersectionoftheventral and dorsalfacesoftheoriginalflake.Thescarsof three bladelets are visible:the first runs along the crest and theothershingeatthesameheight.Thenextphasesaw therejuvenationofthestrikingplatformbymeansoftwo detachmentsand theproductionofonefurtherbladelet

(alsohinged)fromabruteridgeadjacenttotheearlierone (faceB).Thisridgehasanobtuseangle(about120◦)and isformedbytheintersectionofthedorsalfaceand the negativescarsofacrestshapedontheback.

Athirdcore(fig.4n.8)hasoneplatform,thecreation ofwhichinvolvedtheremovalofthebuttfromtheoriginal flake.Aridgeformedbytheintersectionofthedorsaland ventralfaceswasusedtoremoveabladelet,followedbya seriesofhingeddetachments.Thesequenceendswithan attempttowidentheflakingface.Tinyflakeremovalsare relatedtothemaintenanceofthedistalconvexityofthe coreface.

Thelastcoreisonacorticalflakethathasbeenshaped intoatransversescraper.Thebuttwasremovedtocreatea strikingplatform.Asintheprecedingcasestherewasalso exploitationofanunpreparededgemadefromthe inter-sectionbetweentheventraland dorsalfaces.Here,two

bladeletswereproduced.Thecoreisofsimilarsizetothe casesdescribedabove.

Thebladelets have flat(five), punctiform(four), and faceted(two)butts,withmarkedbulbsascribabletodirect percussionwitha stone hammer.The sagittalprofileis straight or slightly convex and its section ranges from triangulartopolygonal.Edgesshowstraightandregular outlinesandremainunretouched.Theelongationindexas calculatedoneightpiecesis2.8.

6. Flakesfromothervolumetricconcepts

Evidenceofdiscoidproductionisprovidedbycoresand flakesrelatingtovariousstagesofthereductionsequence: cortexremoval/initialshaping(four),centripetal(seven) ortangentialflakeremoval(core-edgeremovalflakesand pseudo-Levalloispoints(six)),changeincoreorientation (oneaxialcrestflake).Somerefittingprovidesevidenceof insitureduction.Theseflakingproductsare,forthemost part,wholewithfreshedges,considerablethickness (aver-age1.3cm),quadrangularformandslightelongation.The buttsarealmostalwaysflatandtilted.Thepercussion tech-niquewasdirect witha hard hammer.Two flakes,one corticalandonecentripetal,wererespectivelytransformed intoadenticulateandadoublescraper.Thecoresare cen-tripetaland heavilyreduced:fouroutof fivearebelow 3.5cminlength.

Theassemblagealsocontains coreswhichhave been modified to provide a series of edges, used for recur-rentproductionofsmallmultidirectionalandbidirectional flakes,alternatingbetweentwofacesorwithashortseries fromasingleface.Ahardhammerwasusedforpercussion. Theidentificationoftheproductsfromthisprocedurewas difficultduetotheirrarityandthesmallsizeoftheflakes. 7. Retouchedtooldesign

Retouchedtools are mostly scrapers,while the oth-ersarepoints(four),notches(one),denticulates(seven) andafewretouchedflakes.Simplescrapers(49)prevail overdouble (six), convergent(six) andtransversetypes (five).Generally,toolshavebeenmainlyshapedon Leval-loisblanksandofthese,moreonunipolarthancentripetal flakes (Table 3). Other blanks are cortical and, inci-dentally,various by-products arisingfrom the Levallois coreexploitation:predetermining,corerepairing,platform renewalorflakesfromaccidents.Finally,theblanktypeof averyfewscrapersanddenticulateshasnotbeen deter-minedduetotheinvasivenessoftheretouching.

Scrapershavebeenmadefromdifferenttypesofflakes: simplescrapersusingcorticalflakes,mainlyfromthe ini-tialdecortication,and fromunipolar recurrent flakes;a smallnumberarerecordedonnaturallybacked predeter-miningflakesand,occasionally,onvariousblanksdetached incoremaintenance,Kombewa-typeflakes,butalsoflakes fromaccidents.Similartosimplescrapers,corticaland Lev-alloisflakes weremainlyusedas blanksfor convergent andtransverse tools.Theretouch is simple, moderately invasive,withlessmarginalorstronglyinvasive interven-tions.Fourscraperswerethinnedonthedorsalorventral face.Concerningtheothertools,ithasbeenshownthat

Levallois semi-cortical blades and flakes were used for making pointed items; notches and denticulates were made on quite thick, even cortical flakes, but also on recycled broken flakes, discoidal flakes and various by-products;twopiecesarethinnedontheventralface;the thinningofunretouchedblanksinvolvedcortical,Levallois, Kombewa-typeandplatformtrimmingflakes.

Contrarytothesetrends,thefewtoolswithmarginal, partialordiscontinuousretouchinghavebeenshapedon secondchoiceblankssuchaspredeterminingflakes, occa-sionallycorticalflakesandtworecycledpieces.

8. Discussion

ThelithicindustryfoundintheA5–A6complexprovides alargedatasettoallowinferencestobemadeaboutthe finalLevalloisassemblageandothertypesofproducts.The aimof extracting elongatedLevalloisconvergent blanks withsymmetrical and highlyfunctional lateraledges is also highlighted by the incidence of retouching, which is higher among these flakes–and even on those from theinitialdecortication/production phase–thanfor oth-ers.Theuseoftheunipolarmethodtowardstheendofthe reductionsequenceshowsthatthesetechnicalaimswere constantlypursued,inaccordancewithaprocedurethat hadbeenwell-integratedintothesystemofproduction. Thismightexplainwhyinthecourseofsomesequences there wastechnicalvariation, which involved reduction throughaseriesofblowsinobliqueand,attimes, perpen-diculardirectionsrelativetotheformerseries.Theaimof thismethodwasclearlytoreducetheimpactcausedby expensivere-preparationsofcoreconvexities.Theturning tothecentripetalmethodwhen thereduction sequence ended, butbeforecorediscard,implies minorreshaping ofthesurfacestocontrolthevolumeoftherawmaterial atthesametimeasextractingmorepredeterminedblanks, despitebeinglessmorphologicallynormalizedthan unipo-larblanks.Thisproductiondecisionwasinfluencedbytwo factors:thefirstbeingachangeinthecriterionofthemain aimof yielding blades,notshorter than a givenlength. The second relates to optimizing resources by possibly changingproductiontechniquebecauseofthequalitative deficienciesofsomeflinttypes,therebyreducingtherisk ofaccidentsandfacilitatingre-preparations.

Making a comparison of the Levallois technology between A5–A6 and the chronologically closest layers at Fumane,thereis agreater similaritywithA11,A10V and A10I: unipolar reduction focuses on blades with moreconstrainedmorpho-metriccalibres,although differ-enceshavebeenobserved.ThemodalityinA11combines bidirectional and orthogonal patterns until core deacti-vation, whereas in A5–A6, there is lateralexpansion of thetrimmedstrikingplatformsforthestrikingof conver-gentbladeseries.Again,inthefinalstepofthereduction sequencethis“widened”unipolarpatternisreplacedbythe centripetalprocedure, uptofinaldeactivation(Peresani, 2012).

ThisLateMousteriansequenceatFumanebroadlyfits otherevidencein theNorth AdriaticregionwhereFinal Mousterian practiceis based onthe Levalloisrecurrent unipolarmodality(Peresani,1996).Atthefinalstepsofthe

Table3

Tabulationwithnumberofretouchedtoolsmadeoncorticalflake,Levalloisend-productsandby-products. Tableau3

Tableaureportantlenombred’outilsretouchésobtenussuréclatscorticaux,produitsfinisetsous-produitsLevallois.

A5 A6

Scr. Marg.r. Other Total Scr. Marg.r. Other Total

Corticalflake>50% 3 2 5(11.4) 2 2(4.0) Corticalflake<50% 5 1 6(13.6) 5 1 6(12.0) Platformrenewal 1 1(2.0) Predeterminingflake 3 3(6.8) 6 1 3 10(20.0) Corerepairing 1 1 2(4.0) Flakingaccident 2 2(4.0) Lev.unipolar 5 2 2 9(20.5) 8 1 9(18.0) Lev.centripetal 1 1(2.3) Lev.indeterminable 2 2(4.5) 3 3(6.0) Fragment 6 1 3 10(22.7) 6 2 1 9(18.0) Other 7 1 8(18.2) 3 1 2 6(12.0) Total 32 3 9 44 37 7 6 50 % 72.7 6.8 20.5 100.0 74.5 13.7 11.8 100.0

Lev.:Levallois;Scr.:scrapers;Marg.r.:flakeswithmarginalretouch;“Other”includespoints,denticulates,andcompositedenticulate-scrapertools;“Other” intherowoftheflakingproductsincludesflakesdifferentfromaboveandindeterminableblanksduetoinvasiveretouching.NotethatA5countincludes piecesfromlayerA5+A6(seeexplanationinthetext).

reductionsequence,theunipolarmodalitymayhavebeen

replacedbythecentripetaltoextractthelast,smallflakes.

Toolsarescrapersandpointslargelymadefromthe

Leval-loisblades.SimilarsituationscanbeseenacrosstheItalian

peninsula,wherebladesandelongatedflakes,flatandwith

thinconvergingmargins,havebeennotedatvarioussites,

suchasCastelvicitainCampania(Gambassini,1997)and

Riparol’Oscurusciutolayer1(43.8–42.2kyBP),wherethe laminarLevalloisproductionseemstobeemployedinthe makingofscrapers(Boscatoetal.,2011).

Bladeandbladeletvolumetricproductionislittle rep-resentedinrespecttotheLevalloisatOscurusciuto,but atGrottadelCavallo,alamellarindustryisnotedinthe sectorsFIII–II,developedthroughtheproductionoflocal flintplaquettes (Carmignani,2010).Other lamellar pro-ductionevidencehasbeen,attimes,identifiedtodateat RiparoTagliente,whereaspecificflinttype wasusedin blade production from level37 upwards(Arzarello and Peretto,2005);atSanFrancescoontheLiguriancoast(Bietti andNegrino,2007);atGrottaBreuilontheLatiumCoast; and atGrottaReali,againin theSouth ofItaly (Peretto, 2012).There is nochronometricevidence for the lithic assemblagefoundinasinglelayeratSanFrancesco,which containsmanyUpperPalaeolithictoolsliketruncatedand retouchedbladesmadeonbladesproducedbythe exploita-tionofthreedifferenttypesofcores:prismatic,recurrent Levalloisandprismaticwithlateralcrest(Tavoso,1988). Althoughtheassemblagefromthemostrecentlayersat GrottaBreuilsharesagroupoffeatureswithotherlocal Mousterianassemblages,it shows that, there,the lami-narflakingmethodusedunipolarcoresmadefromsmall pebbleswithnorelationtotheappearanceofUpper Palae-olithictools(RossettiandZanzi,1990).AtGrottaReali,the Mousteriansequenceyieldsevidenceofbladeproduction inlayer5,basedontherecurrentLevalloismethod(mostly unipolar)andonthedetachmentofblades/bladeletsfrom prismatic unipolar cores. In the light of this variability, thefeaturesandthevarietyoftheretouchedtoolsdonot differfromatypicalMousterianprofilecomprisedof scrap-ersanddenticulates.Thisassemblagedatesbetween44.5

and39.4kyBP(Peretto,2012),fallinginawide tempo-ralintervalwhichseestheFinalMousterianreplacedby theUluzzian andthe Proto-Aurignacianin theSouthof thePeninsula(Moronietal.,inpress).Moredataarealso requiredtosetthechronologicalpositionoftheassemblage foundin the second stratigraphiccomplex (layers 2abc and2/2␥),wherebladeproductioncomparabletolayer 5isalsorecorded(Peretto,2012).Thehypothesisclaiming culturalpersistenceatGrottaRealineedsfurther chrono-metricconfirmationfortworeasons:theradiocarbonage oflayer2␥(40.3–37.2kyBP),whichbracketsatimerange containingthestartoftheAurignacianintheSouthofthe Peninsula(atleastfrom40.4kyBP)andthelackof Campa-nianIgnimbriteacrossthesedimentarysuccession(Giaccio etal.,2008).

ReturningtoFumane,abreakwiththisapparently deep-rooteduseoftheunipolarLevalloismethodisrecordedin theoldestUluzzianlayerA4where,rather,flakesandcores weremadeusingthecentripetalinsteadof theunipolar recurrentmodality.Levalloisbladesandlaminarflakesare thereforesporadicandpolygonalorfan-shapedflakesof variablesizesfeatureinthelithicassemblage,inaddition tootherflakesissuingfromotherpoorly curated meth-ods,the incidenceof which increases at thetop of the Uluzziansequence.Aswellasside-scrapersandpoints,the retouchedtoolsincludebackedknives,splinteredpieces andoneend-scraper.Thereareveryfewdenticulatesand marginallyretouchedpointsonLevalloisflake.Thebacked knivesareonthinflakes,whichcanalsobecortical,with thebackeitherstraightorconvex.Thefrequencyof splin-teredpiecesinA3isdoublethatinA4.Theshapesvary,as dothethicknesses(Peresani,2012).

9. Conclusion

During the Final Mousterian, in the North of Italy, the Levallois method continues to enjoy a role of pri-maryimportance,althoughbasedonthestandardization oflaminarproductionwithcarefulcontrolofthe techni-calparameters.Bladesspreadasageneralphenomenonin

theLevalloistechno-complexesintheOldWorldandin manycasesareassociatedwithUpperPaleolithicformal tools.Infact, theeffortdevotedtoproducing elongated flakes/blades appears asa featurethat is shared across manyEuropeanregions intheinterval between50 and 40kyBP.InsouthernCaucasus,inGeorgia,unipolar Leval-loisreductionsmarklevels10to5datedbetween50and 39kyBPatthesiteofOrtvadleKlde(Adleretal.,2006) andproducesuitableblanksformakingsimpleor conver-gentscrapers.IntheCrimeatheMicoquianwasreplaced bythewesternCrimeanMousterian,whoseindustriesare concentratedonlaminarproductsandelongatedpoints, obtainedthroughLevalloisandvolumetric methodsand transformed into simple scrapers or into unifacial foli-atedpoints(Chabai,2000).IntheMiddleDanubearea,a similardiscontinuitymarksthereplacementofMicoquian withthetechno-complexeswithbladesandpointslikethe Bohunician(ˇSkrdla,2003)andtheBachokirian(Kozłowski, 1979;Teyssandier,2006),foundedontheuseofuni-and bipolarLevallois and blade volumetric methods. In the South-EastofFrance,theproduction ofelongatedflakes andnormedpointsusingthesamesystemwasnotedin theNeronian,wherescholarshaveidentifiedapatternof blade/pointand anotherof bladelet/micropoint (Slimak, 2007)thatdonotfindapointofcomparisoninthecontext oftheclassicalMiddlePaleolithicindustries.

Nevertheless,thelackatFumaneoftheco-presenceof LevalloistechnologyandUpperPaleolithictools(asseenin thisEurope-widespectrumofindustries),clearlymarksout thecomplexA5–A6andhighlightsthereplacementwith Uluzziantechnology.Thisreplacementmightbe consid-eredabrupt,similartothatattheotheraforementioned Italiansites,butthecomplementaryuseofother meth-odslikethebladeletmakingseenat Fumaneas wellas atGrottadelCavalloandGrottaReali,seemstorecorda deviationfromthehomogeneitytypicallyexpressedinthe MousterianLevalloisindustriesofthisperiod.

Acknowledgments

Research atFumane is carriedout by theUniversity of Ferrara as part of a long-term project supportedby theSuperintendentforArchaeologicalHeritageofVeneto, theComunità Montana of Lessinia, theFumane Munic-ipality, theVenetian Region, theCariverona Foundation andmanyotherinstitutionalandprivatesupporters.The authorsaregratefultoCraigAlexanderandNicholas Ash-tonforimprovementsmadetotheEnglishversionofthe manuscriptandtotwoanonymousreviewersfor construc-tivesuggestions.

References

Adler,D.,Belfer-Cohen,A.,Bar-Yosef,O.,2006.Betweenarockandahard place:Neanderthal–ModernHumaninteractioninthesouthern Cau-casus.In:Conard,N.(Ed.),WhenNeanderthalsandModemHumans met,InternationalWorkshop.TübingenPublicationsinPrehistory, Verlag,Tübingen,pp.165–187.

Arzarello,M.,Peretto,C.,2005.Nouvellesdonnéessurlescaractéristiques etrévolutiontechno-économiquede l’industriemoustériennede RiparoTagliente(Verona,Italie).In:Molines,N.,Moncel,M.-H., Mon-nier,J.-L.(Eds.),Donnéesrécentessurlesmodalitésdepeuplementet

surlecadrechronostratigraphique,géologiqueetpaléogéographique desindustriesduPaléolithiqueinférieuretmoyenenEurope.BAR InterntionalSeries1364,Archaeopress,Oxford,pp.281–289.

Benazzi,S.,Douka,K.,Fornai,C.,Bauer,C.C.,Kullmer,O.,Svoboda,J.,Pap, I.,Mallegni,F.,Bayle,P.,Coquerelle,M.,Condemi,S.,Ronchitelli,A., Harvati,K.,Weber,K.W.,2011. Earlydispersalofmodemhumans inEuropeandimplicationsforNeanderthalbehaviour.Nature479, 525–528.

Bietti,A.,Negrino,F.,2007. “Transitional”industriesfromNeandertals toAnatomicallyModemHumansincontinentalItaly:presentstate ofknowledge.In:Riel-Salvatore,J.,Clark,G.A.(Eds.),“Transitional” UpperPaleolithicIndustries:newquestions,newmethods.BAR Inter-nationalSeries1620,Archaeopress,Oxford,pp.41–60.

Bird,D.W.,O’Connell,J.F.,2006. Behavioralecologyandarchaeology.J. Archaeol.Res.14,143–188.

Boëda,E.,1994. LeConceptLevallois:variabilitédesméthodes. Mono-graphiesCentreRercherchesArchéologiques9.CNRS,280p.

Boscato,P.,Crezzini,J.,2012. Middle-UpperPalaeolithictransitionin southernItaly:Uluzzian macromammalsfromGrotta delCavallo (Apulia).Quat.Int.252,90–98.

Boscato,P.,Gambassini,P.,Ranaldo,F.,Ronchitelli,A.,2011.Management ofPalaeoenvironmentalResourcesandRawmaterialsExploitationat theMiddlePalaeolithicSiteofOscurusciuto(Ginosa,TA,southern Italy):Units1and4.In:Conard,N.J.,Richter,J.(Eds.),Neanderthal Lifeways,SubsistenceandTechnology:OneHundredFiftyYearsof NeanderthalStudy,VertebratePaleobiologyandPaleoanthropology. Springer,Berlin/Heidelberg,pp.87–98.

Broglio,A.,Gurioli,F.,2004.Lecomportementsymboliquedespremiers Hommesmodernes:lesdonnéesdelaGrottedeFumane(Pré-Alpes vénitiennes).ActesdeColloqueinternationaldeLiège.LaSpiritualité, U.I.S.P.P.,VIIICommission–Paléolithiquesupérieur,ERAUL106,pp. 97–102.

Broglio,A.,Bertola,S.,DeStefani,M.,Marini,D.,Lemorini,C.,Rossetti, P.,2005. Laproductionlamellaireetlesarmatureslamellairesde l’AurignacienanciendelaGrottedeFumane(MontsLessini,Vénétie). In:LeBrun-Ricalens,F.(Ed.),Productionslamellairesattribuéesà l’Aurignacien,Luxembourg.MuséeNationald’Histoireetd’Art,pp. 415–436.

Broglio,A.,DeStefani,M.,Gurioli,F.,Pallecchi,P.,Giachi,G.,Higham,Th., Brock,F.,2009. L’artaurignaciendansladécorationdelaGrottede Fumane.Anthropologie113,753–761.

Carmignani,L.,2010.L’industrialiticadellivelloFIIIediGrottadelCavallo (Nardò,Lecce).Osservazionisuunaproduzionelamino–lamellarein uncontestodelMusterianofinale.OriginiXXXII,NuovaSerie4,7–26.

Centi,L.,2008–2009.L’ultimoLevallois:tecno-economiadellaproduzione liticaeorganizzazionespazialenelcomplessoA5-A6(50.000anniBP) diGrottadiFumane(Verona).Studiodiduevarietàselcifere,Thesis ofbachelor,UniversitàdiFerrara,Ferrara,153p.

Chabai,V.P.,2000. TheevolutionofthewesternCrimeanMousterian industry.In:Orschiedt,J.,Weniger,G.C.(Eds.),Neanderthalsand Mod-ernHumans–Discussingthetransition:CentralandEastemEurope from50,000-30,000B.P.,WissenschaftlicheSchriftendesNeanderthal Museums2.NeanderthalMuseum,Mettmann,pp.196–211.

Dauvois,M.,1981. DelasimultanéitédesconceptsKombewaet Leval-loisdansl’AcheuléenduMaghrebetduSaharanord-occidental.In: Roubet,C.,Hugot,H.,Souville,G.(Eds.),PréhistoireAfricaine.Éditions A.D.P.F,Paris,pp.313–321.

D’Errico,F.,Borgia,V.,Ronchitelli,A.,2012.Uluzzianbonetechnologyand itsimplicationsfortheoriginofbehaviouralmodernity.Quat.Int.259, 59–71.

DiTaranto,E.,2009–2010.L’ultimoLevallois.Tecno-economiae orga-nizzazione spazialedella produzione liticanel complesso A5-A6 (45-44KaBP)dellaGrottadiFumane(Verona).StudiodellaScaglia Rossa,FacoltàdiScienzeMM.FF.NN.,Master’sdegreeinPrehistoric Science.

Gambassini,P.,1997. IlPaleoliticodiCastelcivita.Cultureeambiente. Electa,Napoli,159p.

Giaccio,B.,Isaia,R.,Fedele,F.G.,DiCanzio,E.,Hoffecker,J.,Ronchitelli, A.,Sinitsyn,A.A.,Anikovich,M.,Lisitsyn,S.N.,Popov,V.V.,2008.

TheCampanianIgnimbriteandCodolatephralayers:two tempo-ral/stratigraphicmarkersfortheEarlyUpperPalaeolithicinsouthern ItalyandeasternEurope.J.Volcanol.GeothermalRes.177,208–226.

Gioia,P.,1990. AnaspectofthetransitionbetweenMiddleandUpper PalaeolithicinItaly:theUluzzian.In:Farizy,C.(Ed.),Paléolithique moyenrécentetPaléolithiquesupérieurancienenEurope.Mémoires MuséePréhistoireÎle-de-France3,MuséedePréhistoire,Nemours,pp. 241–245.

Grimaldi,S.,1996. Mousterianreduction sequencesincentralItaly. In: Bietti, A., Grimaldi, S. (Eds.), Reduction Processes (chaînes

opératoires)intheEuropeanMousterian,4.QuaternariaNova,pp. 279–310.

Guette,C.,2002. RévisioncritiqueduconceptdedébitageLevalloisà traversl’étudedugisementmoustériendeSaint-Vaast-la-Hougue/le Fort(chantiersI-IIIetII,niveauxinférieurs)(Manche,Franche).Bull. Soc.Prehist.Fr.99(2),237–248.

Harrold,F.B.,2009. HistoricalPerspectivesontheEuropeanTransition fromMiddletoUpperPaleolithic.In:Camps,M.,Chauhan,P.R.(Eds.), SourcebookofPaleolithictransitions:methods,theoriesand interpre-tations.Springer,NewYork,pp.283–299.

Higham,T.,Brock,F.,Peresani,M.,Broglio,A.,Wood,R.,Douka,K.,2009.

ProblemswithradiocarbondatingtheMiddletoUpperPalaeolthic transitioninItaly.Quat.Sci.Rev.28,1257–1267.

Kozłowski, J.K.,1979. Le Bachokiri: la plus ancienne industrie du PaléolithiquesupérieurenEurope.Quelquesremarquesàproposde lapositionstratigraphiqueettaxonomiquedesoutillagesdelacouche 11delagrotteBachoKiro.PraceArcheologiczne28,77–99.

Lalueza-Fox,C.,Thomas,M.,Gilbert,P.,2011. Paleogenomicsofarchaic hominins.Curr.Biol.21,1002–1009.

Kuhn,S.L.,1994.Aformalapproachtothedesignandassemblyofmobile toolkits.Am.Antiquity59(3),426–442.

Kuhn,S.L.,Bietti,A.,2000. ThelateMiddleandearlyUpperPaleolithicin Italy.In:Bar-Yosef,O.,Pilbeam,D.(Eds.),TheGeographyof Neander-talsandModernHumansinEuropeandtheGreaterMediterranean, PeabodyMuseumBullettin8.PeabodyMuseumPress,CambridgeMA, pp.49–72.

Martini,M.,Sibilia,M.,Croci,S.,Cremaschi,M.,2001. Thermolumines-cence(TL)datingofburntflints:problems,perspectivesandsome examplesofapplication.J.Cult.Herit.2,179–190.

Moroni, A., Boscato, P., Ronchitelli, A., in press. What roots for the Uluzzian? Modern behaviour in central-southern Italy and hypotheses on AMH dispersal routes, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. quaint.2012.10.051.Quat.Int.

Mussi,M.,2001. EarliestItaly.AnoverviewoftheItalianPaleolithicand Mesolithic.Kluwer,NewYork,399p.

Peresani,M.,1996. TheLevalloisreductionstrategyattheCaveofSan Bernardino(NorthernItaly).In:Bietti,A.,Grimaldi,S.(Eds.), Reduc-tionProcesses(chaînesopératoires)intheEuropeanMousterian,5. QuaternariaNova,pp.205–236.

Peresani,M.,2001.Méthodes,objectifsetflexibilitéd’unsystèmede pro-ductionLevalloisdansleNorddel’Italie.Anthropologie105,351–368.

Peresani,M.,2008. AnewculturalfrontierforthelastNeanderthals:the UluzzianinnorthernItaly.Curr.Anthropol.49(4),725–731.

Peresani,M.,2011. TheendoftheMiddlePalaeolithicintheItalian Alps.Anoverview onNeandertalland-use,subsistenceand tech-nology. In:Conard, N.J., Richter, J. (Eds.), Neanderthal Lifeways, SubsistenceandTechnology:OneHundredFiftyYearsofNeanderthal Study, Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology. Springer, Berlin/Heidelberg,pp.249–259.

Peresani,M.,2012.Fiftythousandyearsofflintknappingandtoolshaping acrosstheMousterianandUluzziansequenceofFumaneCave.Quat. Int.247,125–150.

Peresani,M.,Cremaschi,M.,Ferraro,F.,Falguères,C.,Bahain,J.,Gruppioni, G.,Sibilia,E.,Quarta,G.,Calcagnile,L.,Dolo,J.-M.,2008. Ageofthe finalMiddlePaleolithicandUluzzianlevelsatFumaneCave,northern Italyusing14C,ESR,230Th/238U,andthermoluminescencemethods.J.

Arch.Sci.35,2986–2996.

Peresani,M.,Chravzez,J.,Danti,A.,DeMarch,M.,Duches,R.,Gurioli, F.,Muratori,S.,Romandini,M.,Tagliacozzo,A.,Trombino,L.,2011.

Fire-places,frequentationsandtheenvironmentalsettingofthefinal MousterianatFumaneCave:areportfromthe2006–2008research. Quartär58,131–151.

Peretto,C. (Ed.),2012. L’insediamento musteriano diGrotta Reali. RocchettaaVolturno,Molise,Italia,MuseologiaScientificae Natu-ralistica,.AnnaliUniversitàFerrara8/2,164p.

Riel-Salvatore,J.,2009. WhatisaTransitionalindustry?TheUluzzian ofsouthernItalyasacasestudy.In:Camps,M.,Chauhan,P.R.(Eds.), SourcebookofPaleolithictransitions:methods,theoriesand interpre-tations.Springer,NewYork,pp.377–396.

Riel-Salvatore,J.,Barton,C.M.,2004. LatePleistocenetechnology, eco-nomic behavior and land-use dynamics in southern Italy. Am. Antiquity69,257–274.

Ronchitelli,A.,Boscato,P.,Gambassini,P.,2009. Gliultimi neandertal-ianiinItalia:aspetticulturali.In:Facchini,F.,Belcastro,G.M.(Eds.), LalungastoriadiNeandertal.Biologiaecomportamento.JacaBook, Milano,pp.227–257.

Rossetti, P., Zanzi, G., 1990. Technological approach to reduction sequencesofthelithicindustryfromGrottaBreuil.In:Bietti,A.,Manzi, G.(Eds.),ThefossilmanofMonteCirceo.Fiftyyearsofstudiesonthe NeandertalsinLatium,1.QuaternariaNova,pp.351–365.

ˇSkrdla,P.,2003.Bohuniciantechnology:arefittingapproach.In:Svoboda, J.,BarYosef,O.(Eds.),StrànskàSkàla:OriginsoftheUpperPaleolithic intheBrnoBasin,AmericanSchoolofPrehistoricResearchBulletin47, DolniVéstoniceStudies10.PeabodyMuseumPress,CambridgeMA, pp.19–151.

Slimak,L.,2007. LeNéronienetlastructurehistoriquedubasculement duPaléolithiquemoyenauPaléolithiquesupérieurenFrance méditer-ranéenne.C.R.Palevol6,301–309.

Uomini, N.T., 2011. Handedness in Neanderthals. In: Conard, N.J., Richter,J.(Eds.),Neanderthallifeways,subsistenceandtechnology. OnehundredfiftyyearsofNeanderthalStudy,Vertebrate Paleobiol-ogyandPaleoanthropologySeries.Springer,Berlin,Heidelberg,pp. 139–156.

Tavoso,A.,1988. L’outillagedugisementdeSanFrancescoaSanRemo (Ligurie,Italie):nouvelexamen.In:Kozłowski,J.K.(Ed.),L’Hommede Néandertal8.LaMutation.ERAUL36,Liège,pp.193–210.

Teyssandier,N.,2006. QuestioningtheFirst Aurignacian:mono-or multi-culturalphenomenonduringtheformationoftheUpper Pale-olithicin centralEurope andthe Balkans.Anthropologie44(1), 9–29.

VanAndel,T.H.,Davies,W.,2003.Neanderthalsandmodemhumansinthe Europeanlandscapeduringthelastglaciation:archaeologicalresults oftheStage3Project.McDonaldInstituteforArchaeologicalResearch monographs,Cambridge,265p.