UNIVERSITY OF CATANIA

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS

The Effect of Emotions and Imagery

Appeals on Visual Consumption

Experiences

By Alessandra Distefano 2/12/2013 A dissertation presented tothe University of Catania in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

1 ©2013 Alessandra Distefano

2 To my family

3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have come to realize that this dissertation would not have been possible without

the enduring support of my family and friends. To my family, thank you for your

endless love and encouragement you have given me. To my mother, thank you for

teaching me to find my inner strength and determination. To my father, thank you

for teaching me to always do one-step better than my best. Lastly, to my big brother,

thank you for giving me the confidence to persevere, as you do in your life.

Special thanks go to my committee for constructive critique and steady guidance. My

deepest gratitude goes to Dr. Marco Galvagno for his willingness to see me through

to the end. Many thanks go to Dr. Vincenzo Pisano for his constructive observations

and life lessons. Thanks to Prof. Joe Alba, to Prof. Chris Janiszewski and to all the

Department of Marketing of the Warrington College of Business Administration, at

the University of Florida for hosting me.

Thank you Syed Rahman for helping me out with technical issues I encountered in

the elaboration of the data. I really appreciated your help.

In the last two years of my Ph.D. program I had the chance to meet willing people,

who helped me improving my skills, who gave me motivation and who taught me to

pursue my goals.

4 LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Mitroff and Kilmann's scientific styles. Source: Belk, 1986. ... 13

Figure 2: Conceptual Framework………...……….31

Figure 3: Hierarchy of Affect Model (Lavidge & Steiner, 1961)………..54

Figure 4: Ray's (1973) Model of Attitude Formation ………..…………...54

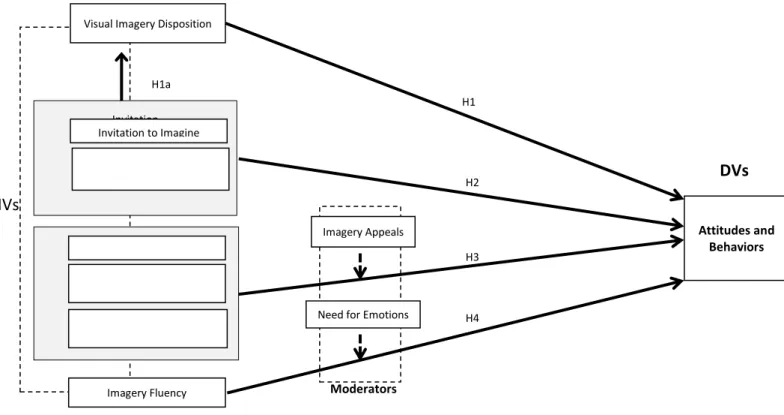

Figure 5: Research Framework and Hypotheses ………..………72

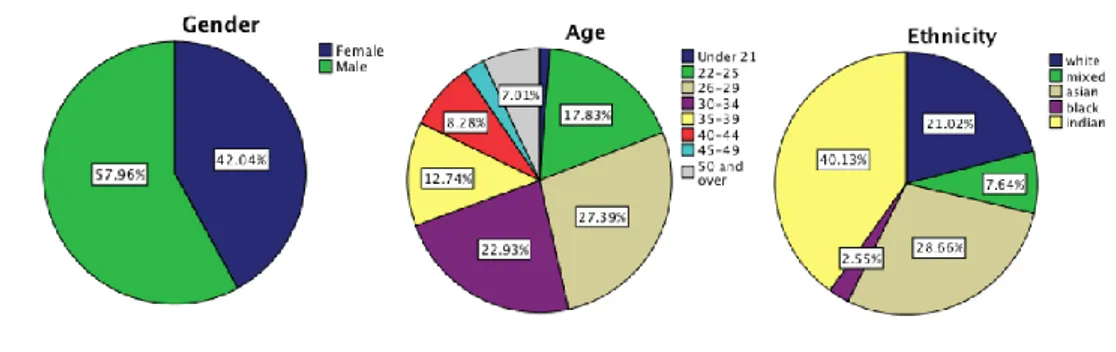

Figure 6: Study 1 - Demographic data ………...76

Figure 7: Plot – Study 1: Interaction between the Invitation to Imagine and the levels (high/low) of DIV, on behav1 and behav3………...82

Figure 8: Plot – Study 1: Interaction between Invitation to Imagine and DIV on Overall FEELINGS……….…….………...85

Figure 9: Study 2 - Demographic data ………....…….………...88

Figure 10: Plot – Study 2: Interaction between Invitation to Imagine and accessibility of the consumption imagery on Purchase Intentions……….………92

Figure 11: Demographic data from Study 3 .………..95

Figure 12: The effect of the Conditions on Behavior toward the ad………..97

Figure 13: The effect of the Conditions on Purchase Intentions………97

Figure 14: Plot – Study 3: Interaction between levels of NFE and description of the ad……….………100

5 LIST OF TABLES

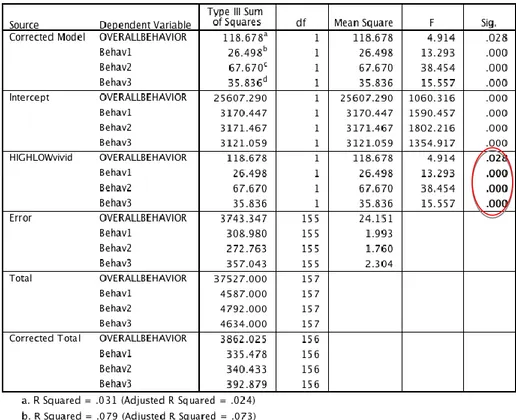

Table 1: The Need for Emotion Scale. ... 27 Table 2: Experimental Design. ... 73 Table 3: MANOVA - Study 1: Relationship between Overall BEHAVIOR, behav1,

behav2, behav3, and DIV levels (HIGHLOWVivid) ... 78 Table 4: MANOVA - Study 1: Relationship between DIV and Overall FEELINGS,

Excitement, Appeals, Interest, and Pleasure. ... 79 Table 5: ANOVA - Study 1: Positive relationship between Purchase Intentions and

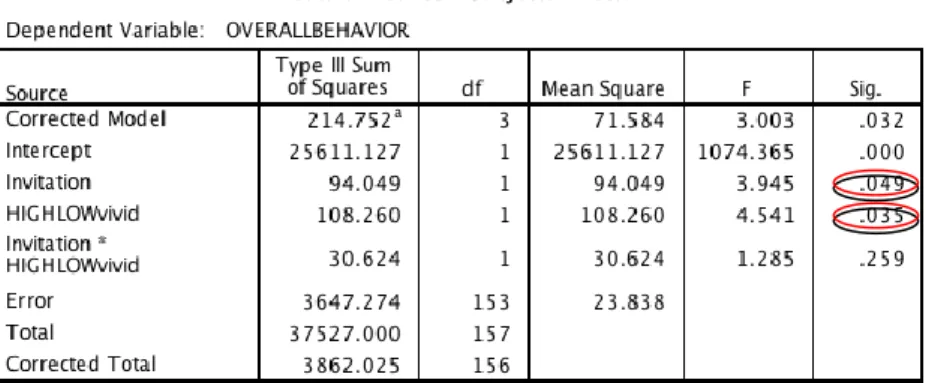

DIV. ... 80 Table 6: ANOVA - Study 1: Interaction between Invitation to Imagine and DIV. ... 81 Table 7: ANOVA – Study 1: Interaction between Invitation to Imagine and DIV on

behav1.. ... 81 Table 8: ANOVA – Study 1: Interaction between Invitation to Imagine and DIV on

behav2 ... 82 Table 9: ANOVA – Study 1: Interaction between Invitation to Imagine and DIV on

behav3.. ... 82 Table 10: ANOVA – Study 1: Interaction between Invitation to Imagine and DIV on

Purchase Intentions. ... 83 Table 11: ANOVA – Study 1: Interaction between Invitation to Imagine and DIV on

Overall FEELINGS. ... 84 Table 12: ANOVA – Study 2: The effect of the interaction between image vividness

and Invitation to imagine the ad, on Overall FEELINGS ... 90 Table 13: ANOVA - Study 2: the effect of the interaction between vividness and

imaging were significant in regard to Purchase Intentions. ... 90 Table 14: ANOVA - Study 2: the effect of the interaction between vividness and

imaging were significant in regard to Overall BEHAVIOR ... 91 Table 15: ANOVA - Study 2: Interaction between invitation to imagine and

accessibility of the consumption imagery on Purchase Intentions. ... 91 Table 16: ANOVA - Study 2: Interaction between invitation to imagine and

accessibility of the consumption imagery on Overall BEHAVIOR. ... 92 Table 17: The effect of Conditions on Attitudes and Behaviors ... 96 Table 18: MANOVA - Study 3: the effect of the interaction between description levels

and NFE levels. ... 99 Table 19: ANOVA - Study 3: The effect of the interaction between vividness and NFE

6 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... 3 LIST OF FIGURES ... 4 LIST OF TABLES……….……….5 ABSTRACT ... 8 CHAPTER 1... 10 1. OVERVIEW ... 10

1.1. Interpretive approach in consumer research ... 10

1.2. Consumers’ Emotions and Marketing ... 14

1.3. Consumers’ consumption visions and Marketing... 17

1.4. Consumers’ Desires and Company’s goals ... 19

1.5. Dissertation framework ... 21

1.6. Research questions and their importance ... 23

CHAPTER 2... 29

2. LITERATURE REVIEW ... 29

2.1. The role of Imagination and Consumption Vision in Consumer Behavior ... 29

2.1.1. Imagery appeals ... 34

2.1.2. Imagery fluency ... 36

2.1.3. Imagery vividness ... 39

2.1.4. Individual differences... 43

2.1.5. Conclusions ... 44

2.2. The role of Emotion in Consumer Behavior ... 45

2.2.1. Emotions and Cognition ... 49

2.2.2. Emotions and Consumption ... 55

2.2.3. Emotions and Imagination ... 57

2.2.4. Seeking emotional situations: individual differences ... 58

2.2.5. Conclusions ... 60

CHAPTER 3... 62

3. METHOD ... 62

3.1. Experimental Design ... 62

3.2. Research Model and Hypotheses ... 65

3.3. Research Design ... 70

3.3.1. Study 1 ... 70

Method ... 72

7

3.3.2. Study 2 ... 81

Method ... 82

Results and Discussion ... 83

3.3.3. Study 3 ... 88

Method ... 88

Results and Discussion ... 90

CHAPTER 4... 97

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION ... 97

4.1. General Discussion ... 97

4.2. Conclusion ... 98

4.3. Theoretical Implications ... 100

4.4. Managerial Implications ... 101

4.5. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research ... 102

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 106 APPENDIX A ... 117 APPENDIX B ... 117 APPENDIX C ... 120 APPENDIX D ... 121 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH ... 124

8 ABSTRACT

There is currently a mismatch between our traditional models of consumer

decision-making and the way consumers actually make decisions, at least for certain

product categories. Multi-attribute models have been successful in modeling how

consumers make decisions about frequently purchased products or services, where

decision-making progresses rationally. But these models cannot account for decisions in

which less experience is available, where the problem is not well structured, and where

emotional reactions are important. Whereas traditional models assume verbal and

semantic processes, the consumption vision perspective focuses on visual and imaginal

processing. The consumption vision approach explicitly acknowledges creative sense,

making processes consumers use to anticipate the future.

A consumption vision can be defined as a visual image of certain product-related

behaviors and their consequences on decision-making processes. Consumption visions

consist of concrete and vivid mental images that enable consumers to experience

self-relevant consequences of product use. Based on the findings of several studies on

consumption visions and on the role of anticipated emotions in consumption

experiences, the goal of this study is to understand what triggers consumption visions,

and consequently, in what direction consumption visions influence consumers’ decision

making processes. I suggest that forming a consumption vision is one possible heuristic

approach by which a consumer can decide among alternative courses of action. I

discuss the possible effects of consumption visions on consumers’ cognitive and

affective reactions to products, intentions, and behaviors.

Three studies examine the mediating role of imagery accessibility during

9 can reverse the generally observed positive effects on imagery appeals and

consumption decisions. The same results indeed, can be achieved considering

consumers’ predisposition to emotional experiences. When participants are low in

imagery abilities (as well as when they show low need for emotion attitudes), whether

there is or not an explicit invitation to imagine a consumption experience, or whether

the product is present in a vivid manner or not, imagery appeals are not only ineffective,

but even have a negative effect on product preferences. Moreover, this work aims to

demonstrate that imagery fluency effect, given its subjective nature, is more likely for

individuals with richer personal past experiences or with higher predisposition to use

imagination (higher in need for emotions levels). Finally, I discuss how consumer

researchers can integrate consumption visions into decision-making research.

KEYWORDS: Mental Imagery, Imagery Appeals, Image Vividness, Imagery Fluency, Emotions, Visual Consumption.

10

CHAPTER 1

“The fact that man is unfinished…does not mean that a description is impossible, but that such a description must be directed to possibilities rather than properties. The fact that each individual is unique does not mean that we are confronted with formless and indescribable multiplicity, for there are limits or horizons within all these unique existents fall, and there are structures that can be discerned in all of them”.

MacQuairre, 1972, p.78.

1. OVERVIEW

1.1. Interpretive approach in consumer research

Despite the extensive body of interpretive consumer research during the past 20

years (Hirschman, 1992; Levy, 1981; Belk et al. 1988; Wallendorf & Arnould, 1991; Hill,

1991; Szmigin & Foxall, 2000), this approach to studying consumers has received many

criticisms (Calder & Tybout, 1987, 1989; Hunt, 1989) and has been equally defended

(Holbrook, 1987; Holbrook & O’Shaughnessy, 1988) over the years. Much of the

controversy over interpretive consumer research has been at the epistemological level

(Spiggle, 1994). Specifically, of special consideration has been the issue of how

knowledge emanating from such research can be evaluated (Hirschman, 1985;

Thompson et al., 1989). Additionally, there has been a scientific debate which

questioned which type of research can be classified as “scientific”, and implies different

levels of research, from the everyday to the scientific one, and together with this, an

implied value judgment of the relative contribution of each (Calder & Tybout, 1987,

1989; Holbrook, 1987; Hirschman, 1985).

Interpretivists emphasize the totality of the human being, which emerges through

the course of their lives (Hirschman & Holbrook, 1986). Interpretive researchers see the

limitations of quantitative measures primarily in their statistic status, rather viewing

11 Hirshman and Holbrook (1986) did not rejected quantitative approaches, but

viewed them as measures based only on one aspect of consumers at one point in time,

which they translate as being like a “snapshot of someone no longer there” (Szmigin &

Foxall, 2000, p. 188). Similarly they did not rejected the concept of a “real world” out

there, but presented the reality which mattered the most during consumption as that

which is subjectively experienced in the consumer’s mind. Is this experience, they

believe, which is real to consumers, and so, researchers should shift from the traditional

scientific posture of personal distance and a-priori theoretical structure, to one of trying

to understand consumers’ experiences in their own terms. This approach has been

supported by Thompson et al. (1989) in their description of the method of

existential-phenomenology, where they presented consumer’s experience as “being-in-the-world”

and describing this experience as it emerges, or is “lived” (e.g. to express such aspect,

consumers might often say, “I just can’t explain it to you; you had to be there to

understand it”). In such instances of consumptions, being there is what matter most.

Researchers, thus, become the measuring instruments and their understanding

will derive from personal experience rather than manipulation of variables.

A potentially controversial aspect of this research approach is its shift in focus

away from managerial relevance. Consumer research becomes grounded with a central

focus on consumption while, at the same time, remaining independent of a need to

show relevance to marketing interests (Holbrook, 1987). In this sense, it becomes a field

of inquiry in its own right and may be closer to the humanities than to science.

Traditionally it has been considered that there is a little overlap between art and

science: art has been considered to be concerned with seeking beauty while science has

12 not feel the need for their research to have managerial implications, the corollary of

this position is not that such research cannot have implications for management.

Indeed, as qualitative research in general, the interpretive approach can bring

managers closer to their consumers, and by exploring issues that may have previously

only been captured by statistics, provide usable insights into how their customers

actually consume (Fournier & Yao, 1997).

Hirshman and Holbrook (1986) contend that, ultimately, any model of

consumption cannot expect to realistically identify causal effect reliability. To

investigate and comprehend the consumption experience the researchers need to be

involved with the phenomenon. In this way the researcher cultivates an openness,

which will be receptive to the structure and meanings, which come directly from the

consumers. Consumers’ experience, then, needs to be understood in their terms rather

than forcing them into some pre-existing structure of the researcher’s making.

Hirshman (1985) has suggested that science should be viewed as an inherently

normative, person-centered enterprise rather than a phenomenon-based process of

truth discovery. Science is still created by people and as such is the subject to the

influence of their attitudes, personalities, etc. Both Hirshman (1985) and Belk (1986)

refer to Mitroff and Kilmann’s (1978) classification into four types of scientists to

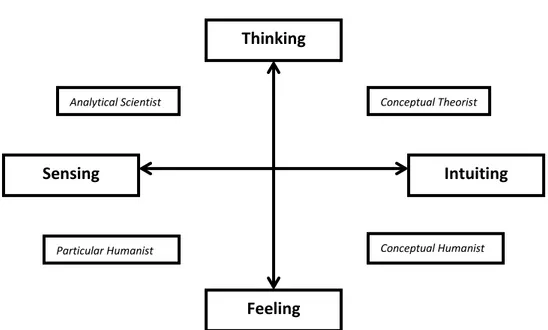

support their view of plurality within the scientific approach (Figure 1).

Using this descriptive framework, the Analytical Scientist is closest to the

traditional logical positivist view1 of science. The other types move more toward the

1

In the past two decades of consumer research the dominant paradigm has been the logical positivism (or a more current version known as modern empiricism), and the implications of this philosophy for research methodology have been widely discussed (Hirshman, 1986; Holbrook & Hirshman, 1982; Hunt, 1983, Peter & Olsen, 1983). Logical positivism has an epistemological focus, and seeks to determine the “truth value” of statements (Pepper, 1942). Some have noted, however, that a broader set of assumptions underlies the use of positivist methods (Giorgi, 1971; 1983; Pollio, 1982). These meta-assumptions have been placed under the more global philosophical rubrics of “Cartesianism” or “rationalism”. Some of the more tenets of Cartesianism are the

13 feeling and intuiting from sensing and thinking and, in so doing, they shift to some

degree from a traditional scientist’s position toward a traditional artist’s position, with

the conceptual humanist pursuing knowledge through subjective and speculative

insight.

Figure 1: Mitroff and Kilmann's scientific styles. Source: Belk, 1986.

In conclusion, while intuitively the complexity of human behavior would be likely

to result in many differing patterns and realities, this may not always be the case. While

there may not be only one “reality”, for some investigations there may be some that

are either more convincing or prevalent than the rest.

Whereas in natural science there are some facts that are viewed as unambiguous,

the nature of interpretive research means that there can be a number of alternative

interpretations from which to choose to represent the phenomenon under study.

Similarly, when researching on consumer’s consumption experiences, researchers need

to ask themselves if this interpretive approach undermines the trustworthiness of the

distinction between mind and body and the assumption that “reality” must be deducted and then rendered in mathematical terms. Thinking Feeling Intuiting Sensing Conceptual Theorist Conceptual Humanist Particular Humanist Analytical Scientist

14 research, or makes it a better exemplar of the real world.

An immediate application of existential-phenomenology to consumer-behavior

phenomena appears to lie in the areas of esthetic, hedonic, and emotional responses

(Hirshman & Holbrook, 1982, 1986; Holbrook & Hirshman, 1982).

Perhaps more than any other form of consumption experiences, such

aesthetic-hedonic-emotional reactions involve the whole of consciousness: senses, thoughts,

feelings, and values. It follows that consumers may find it difficult to reduce such

consumption experiences to verbal labels. Marketing researchers lately, have being

challenged to change their focus from the observation of the consumption as an

external independent phenomenon to the study of consumption experiences under the

individuals’ point of view, in order to meet their needs, and make marketing strategies

more effective and consumer-oriented.

1.2. Consumers’ Emotions and Marketing

In several fields like product development and brand loyalty, more companies are

faced with the need to tailor the creation of their products or services to an increasingly

fragmented customer base and a larger range of consumer behaviors. Marketing has a

large and growing body of academics that feel the need to move away from the view of

highly rational consumer that glut the marketing literature and to formally admit that

the “calculating-machine model” of the consumer is a myth.

In the practice of marketing, if we look at this as opposed to the academic view,

there seems to be a roughly equal separation between those who perceive consumers

as mainly emotional human beings and those whose perspective of consumers is based

on something approximating the “rational choice model” of the economist.

15 impacting the effectiveness of the distribution models. Marketers are being forced to

replace models that were once considered as stable as fully appropriate for a given set

of products or services with new models that have uncertainties and implications on

the value chain (Ansari et al., 2008; Metha et al., 2006; Tsay & Agrawal, 2004).

Relying on familiar research techniques, consequently, misreads consumers’

actions and thoughts. In general, our resistance to changes increases when the

challenge forces us to reconsider not just “what” we think (that is, the content of an

idea) but also “how” we think (i.e., the process) (Zaltman, 2003).

The most troubling consequence of the existing paradigm has been the artificial

disconnection of mind, body, brain, and society. Only by reconnecting the spread pieces

of their thinking about consumers, can companies truly grasp and meet consumers’

needs more effectively.

We should start reconsidering consumers’ perspectives in purchasing or

consuming decision-making processes, being aware that marketers usually make many

errors in considering consumers as subjects perfectly understandable.

In fact, many of them believe that consumers make decisions deliberately, that is,

they consciously contemplate the individual and relative values of an object’s attribute

and the probability that it actualizes the assigned values, and then process this

information in some logical way to arrive to a judgment. Consumer decision-making

sometimes does involve this so-called rational thinking. However, it does not

adequately depict how consumers make choices. In reality, people’s emotions are

closely interwoven with reasoning processes.

More important, emotions are essential for decision-making. Emotion is always a

16 No experience is completely empty of emotion and emotion is never a semidetached

adjunct to consumer process.

For example, a perfume’s fragrance may evoke a particular memory and an

associated emotion in a potential buyer. If the memory triggers a sad emotion, then the

individual probably won’t buy the perfume, even if the fragrance, price, packaging, and

other qualities meet her criteria. If so, marketers will likely judge this behavior as

irrational, since they don’t understand why she rejected the perfume (Zaltman, 2003).

Another aspect to consider is that marketers assume that consumers can easily

describe their own emotions.

Emotions are by definition unconscious (O’Shaughnessy & O’Shaughnessy, 2003).

Most of our thinking doesn’t take place in our conscious mind, but in our unconscious

one instead. The consumer whose purchase for a specific perfume is strongly influenced

by a memory or a record, and the associated emotion is unlikely to articulate this

reason when a researcher explores the decision with conventional research tools.

Rather, the mind, body, brain, and external world constantly influence and are

influenced by the others. The most well known examples involve blind taste tests in

which the sample lack of brand information alters participants’ taste experience.

Marketing specialists also tend to think of consumers’ brains as a “camera” that

takes pictures in the form of memories. They assume that those memories, like

photographs, accurately capture what a person clearly saw. They also believe that what

a consumer says she/he remembers remains constant over time, and that a shopping

experience a consumer recalls today is the exact same experience she/he recalled a

week ago or will recall some months from now. But our memories are far more creative

17 Another common assumption is that consumers think in words. Of course, words

do play an important role in conveying our thoughts, but they don’t provide the whole

picture. This belief makes marketers assume that they can inject whatever messages

they desire into consumers’ mind about a company brand or product positioning.

Because of that, marketers view consumers as white canvas on which they can write

anything they want. Instead, when consumers are exposed to product concepts, stories

or brand information, they don’t passively absorb those messages. Rather, they create

their own meaning by mixing information from the company with their own memories,

other stimuli present at the moment, and the images that come to mind as they think

about the firm’s message.

In conclusion it is possible to affirm that consumers’ decision-making and buying

behaviors are driven more by unconscious thoughts and feelings than by conscious ones,

although the latter are also important. They operate from conscious to unconscious

forces that mutually influence one another.

1.3. Consumers’ consumption visions and Marketing

Consumers, who construct consumption visions (both conscious or unconscious)

may become more committed to achieving actual consumption and may thus

demonstrate predictable increases in traditional marketing-related variables such as

attitudes and intentions toward a brand, a product or a service.

The concept of consumption vision is derived from that of mental imagery

(Phillips, Olson, & Baumgartner, 1995) and entails sensory representations of ideas,

feelings, and objects of experiences with objects. From a consumer behavior

perspective, specifically in relation to intangible or experiential purchases, a consumers’

18 them in forming a judgment (Shwartz, 1986). Furthermore, Horowitz (1972) claims that

visual image formation is especially useful in the representation of the self and object

relationships as found in the external world trough perception, or as fantasized in the

trial perception or trial action of thought.

In other words, if the target is not present in the direct physical environment,

people may still perform their evaluations by examining their mental representation of

the target, or the images that come to mind when they imagine their consumption

experience. Phillips, Olson & Baumgartner (1995) identify this experience as being a

consumption vision, which Walker & Olson (1994) define as “ visual images of certain

product related-behaviors and their consequences (...). They consist of concrete and

vivid mental images that enable consumers to vicariously experience the self-relevant

consequences of product use” (p.27).

However, due to the intangible nature of some consumption experiences such as

tourism products or outdoor activities experiences, if the consumer has never visited or

has never had any previous experience involving the outdoor activity, the consumption

vision may be the only initial source of information and serve as the only influence at

early stages of the decision process (Schwarz, 1986).

The effective usage of external stimuli featured in most services advertising and

promotional material plays a vital role in the evocation of elaborate consumption

visions (Mittal, 1988; Reilly, 1990). It is the external inputs that represent not only the

advertised product, but also communicate the product’s attributes, characteristics,

concepts, and ideas (Mackay, & Fesenmaier, 1997). For this reason, an understanding of

the most effective usage of these various types of external stimuli is of a great importance to marketers.

19 Previous research in marketing communications and mental imagery has

investigated a number of individual forms of external stimuli with regard to their

effectiveness in evoking mental imagery. For example, Miller and Stocia (2003) found

that photographic images of beach scenes were more effective in evoking mental

imagery that artistic version of the same image. Babin and Burns (1997) revealed that

concrete imagery eliciting words evoke high instances of product recall, and study by

Miller and Marks (1998) found a strong relationship between instructions to imagine

and the quantity of imagery.

However, to date, research in this area has failed to investigate the combined

usage of these various forms of external stimuli and their combination’s effectiveness in

evoking elaborate consumption visions.

The purpose of this work is to identify the most effective combination of external

stimuli in evoking elaborate consumption visions among outdoor activities consumers –

focusing on printing advertisements with different level of image vividness and different

descriptive levels of information.

1.4. Consumers’ Desires and Company’s goals

The intensity and frequency of the interactions among consumers and

organizations have increased in recent years, facilitated by the technological advantage

(Kraut et al. 2006). This change has had an impact on the effectiveness of marketing

since direct information exchanges between the customers influence the way they

make purchase decisions (Burt 1998; White 1981). Understanding the consumer

behavior in context-specific consuming experiences can be very important and can

define the difference between success and failure of companies in the marketplace.

20 experiences and it means that companies’ advertisements play a strong role and have a

strong impact on people’s decisions to take or not take certain actions. Therefore, in

order to maximize their success, companies should consider the type and strength of

emotions induced through advertising.

In the marketing literature, emotions and imaginations have existed for decades

but there has been too little adaptation of the theory to the evolving of today’s market

specifics (Goldie, 2000). The ways people purchase and consume goods and services are

constantly evolving and drive a continuous adaptation of the marketing concepts and

approaches (Achrol & Kotler, 1999).

Arousing feelings for new purchases has never been easy and the growing

number of social stimuli can impact individuals’ choices, needs, preferences and ways of

spending their money (Kraut et al., 2006).

The actual behavioral achievement of these acts then becomes the goals the

consumer wishes to achieve as a result of their experience purchase. For example, a

consumer may ask himself or herself: What do I want from this experience? Do I want

to have fun and escape from the routine? Do I want to experience something unique

and new? Driven by the answer to these questions, consumers then create images and

fantasies in their mind and use these images to direct their information search and

purchase. Therefore, a further understanding of how outdoor activities market

providers can successfully capture the consumer’s imagination will assist services

marketers in acquiring a competitive advantage in the mind of their targeted audience.

Given these premises, the goal of this work is to highlight some of these aspects,

with regard to consumers’ emotional and visual imagery dispositions toward an unusual

21 climbing experience, as an outdoor activity will be considered, since it is becoming well

known but is not a common practice yet among the majority of consumers. More often

consumers choose it because it is something they have always wanted to do, but search

is minimal and expectations are vague. Often consumers articulate the desire for

something “beyond their imagination”. The experience is extraordinary because it

offers absorption and a newness of perception and process (Arnould & Price, 1993).

The following section will show the design of this dissertation.

1.5. Dissertation framework

Before discussing specific types of consumers’ processes of thinking and feeling,

related to consumers’ consumption behavior, it seems useful to place this dissertation

in a larger framework.

This work researches on the importance of imagination in consumer behavior

literature and the role played by imagery fluency, affects and emotions during

consumption visions. The results of this study demonstrate that marketers can use

certain advertising tools to help consumers construct consumption visions. These

consumption visions, in turn, result in more positive attitudes and intentions, which

may energize consumers toward actual consumption.

Therefore, this research is focuses on how imagery appeals, imagination and

emotions work within a cultural system of meanings influenced by marketing

strategies to give a boost to consumers’ attitudes and intentions toward new

products or services unlikely experienced before. The notion of what concerns the

consumer can thus tell us what will receive his or her attention.

More contemporary investigations reveal new processes that may be taken in

22 persuasiveness of narrative reveals, narratives are effective in changing attitudes and

beliefs because they transport individuals into a different reality, reducing

consideration of the positive or negative aspects of the message (Green & Brock, 2000).

Another general area of research on the effect of imagery focuses on consumers’

subjective experience of fluency. That is, when forming attitudes, opinion and

judgments, individuals are likely to take into account not only the content of the

information with which they are presented, but also the ease with which this

information comes to mind (Schwarz, 1998, 2004). However, the ease with which

consumers can image themselves with the product can also be influenced by factors

irrelevant to their intentions.

Engaging consumers in product imagery through the use of commercial images,

for instance, can create readily accessible metal representation of having the product

and can increase the ease with which such representation will spring to mind during the

decision-making process. By increasing the accessibility of such representations,

imagery appeals can increase the likelihood of purchasing the product.

Given these premises, the dissertation will develop as follow:

Chapter 1 introduces the study, research questions, grounding theories and

research model. Chapter 2 provides a detailed literature review intersecting several

theoretical fields and focusing on the role of emotions and imagination in stimulating

consumption experiences, imagery appeals, image vividness, and imagery fluency.

Chapter 3 details the proposed research model, lays out the research hypotheses

and discusses the selected research design, including survey instruments, approaches to

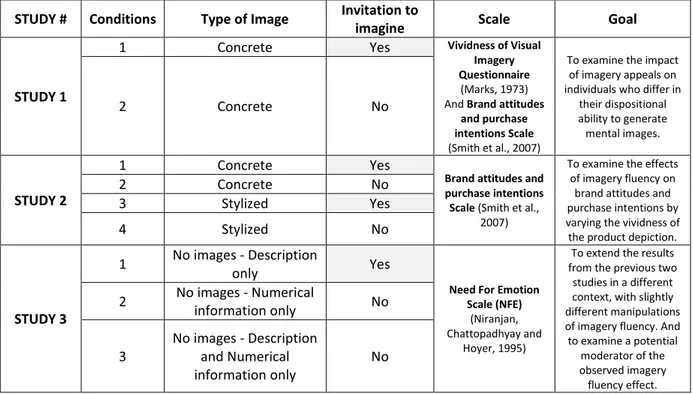

data collection and data analysis of 3 related studies. Specifically, Study 1 examines the

23 generate mental images. As shown in previous studies on the effect of imagery with

product having an experiential component, this study examines the effect of imagery

fluency in the context of a rock climbing advertisement. Study 2 examines the effect of

imagery fluency by varying the vividness of the product depiction. Two conditions (high

versus low vividness conditions) were created using the same ads of the first study for

the high vividness condition, and adding two more muted and stylized versions of the

ads for the low vividness conditions. Consistent with the definition of vividness (Nisbett

& Ross, 1980) I show that participants report more positive emotions in response to the

ad high in vividness than the ad low in vividness. Study 3 replicates and extends the

results from the previous two studies in another context, with different manipulations

of imagery fluency.

Furthermore in this third study I examine a potential moderator of the observed

imagery fluency effect, specifically I used the Need for Emotions scale (Raman,

Chattopadhyay & Hoyer, 1995) to test the tendency or propensity for individuals to

seek out emotional situations, enjoy emotional stimuli, and exhibit a preference to use

emotion in interacting with the world. Lately this chapter describes the steps included

in the performed statistical analysis and provides a detailed report of the yielded results

and findings.

Chapter 4 offers an analytical discussion of the results and concludes with the

limitations of this work and proposed directions for future research.

1.6. Research questions and their importance

Given the complexity of this topic area the present dissertation focuses on the

factors that can increase or decrease the emotional potential of a trade-off by

24 consumption, when based on imaging or visual imaging become complex and cryptic.

Images, whether paintings, drawings, photographs, or just mental do not necessarily

speak themselves, rather, they make visible a realm of possibilities and potential

meanings, many of which are difficult to articulate (Schroeder, 2000). Moreover,

looking at the cultural roots, the multicultural identity, the gender, the sexuality and the

past experience that mark one’s life makes the study of imagined consumption of

experiences even harder.

Therefore, the objective of the present study is to use sociological and

psychological variables to explain the possible motivating factors behind the decision

making process subsequent to an imagery appeal of a consumption experience. Four

questions arise from this study:

1) Do imagery appeals have a positive effect on brand attitudes and purchase intentions?

2) What is the effect of image vividness in enhancing consumption preferences? 3) Are there information that, if added to a vivid depiction, will undermine the

effect of the imaging instructions on product choice?

4) And finally, do different need-for-emotion levels enhance the positive effect of imagery fluency on consumers’ attitudes and behavior intentions?

In order to answer these questions I will employ the principles of the theory of reasoned action-TRA (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajezen, 1975), which posits that behavioral intentions are a function of salient information or beliefs about the likelihood that performing a particular behavior will lead to a specific outcome, and on the extension of this theory, conceptualized by Ajezen, (1985), called the theory of planned behavior-TPB. This theory includes the role of beliefs regarding the

25

possession of requisite resources and opportunities for performing a given behavior. The more resources and opportunities individuals think they possess, the greater should be their perceived behavioral control over the behavior.

In addition, I will introduce the positive role played by the imagery appeals in enhancing consumers’ attitudes toward a product or a service. Specifically, it has been demonstrated that the imagery can have a powerful effect on product preferences (Petrova and Cialdini, 2005). However, there are circumstances under which asking consumers to imagine their future experiences with a product may be not only ineffective, but may actually decrease the likelihood of the consequent behavior (e.g., purchasing the product).

This research follows recent findings showing that judgments are influenced not only by the content of the product information, but also by the ease with which one generates or processes the information (Schwarz, 2004).

Using the imagery as the main object of product preferences formation, this research will test the possibility that consumers may decide about purchasing or consuming, grounding their intentions on the ease with which they can imagine their future experience with the product.

To measure individual’s predisposition to imagine new emotional experiences, in the third study I will employ the Need for Emotion Scale (NFE), developed by Niranjan, Chattopadhyay and Hoyer (1995). This scale is based on the assumption that, similar to “thinkers” who enjoy thinking (Murphy, 1947; Cacioppo, Petty, and Kao, 1984), it is possible to conceive for “experiencers” who enjoy experiencing emotions, instead.

26

important insights regarding how individual seek out situations of varying emotional intensity, process information (through imagination processes) from communications and engage in decision making (Niranjan, Chattopadhyay and Hoyer, 1995).

The Need For Emotions Scale Scale Items

1) I try to anticipate and avoid situations where there is a likely chance of me getting emotionally involved.

2) Experiencing strong emotions is not something I enjoy very much. 3) I would rather be in a situation in which I experience little

emotion than one in which is sure to get me emotionally involved. 4) I don’t look forward to being in situations that others have found

to be emotional.

5) I look forward to situations that I know are less emotionally involving.

6) I like to be unemotional in emotional situations. 7) I find little satisfaction in experiencing strong emotions. 8) I prefer to keep my feelings under check.

9) I feel relief rather than fulfilled after experiencing a situation that was very emotional.

10) I prefer to ignore the emotional aspects of situations rather than getting involved in them.

11) More often than not, making decisions based on emotions just leads to more errors.

12) I don’t like to have the responsibility of handling a situation that is emotional in nature.

Table 1: The Need for Emotion Scale (Raman, Chattopadhyay & Hoyer, 1995).

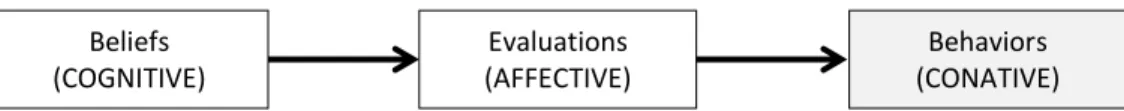

Although extensive studies have demonstrated the importance of effects of affect and moods on consumers' memories, evaluations, judgment and behavior (e.g. Edell and Burke 1987; Gardner 1985), most research in consumer behavior has focused on affective components of ads (Aaker and Bruzzone 1985; Mitchell 1986) or affective responses to ads (Holbrook and Batra 1987; Stout and Leckenby 1986).

27

Alternatively, many studies in this area have induced a specific emotion in subjects artificially, and then examined the effects of this affect for all subjects in that condition taken together (Booth-Butterfield and Booth-Butterfield 1990). Differences across individuals regarding a need for seeking out and experiencing emotion have, for the most part, been ignored (with the exception of Allen & Hamsher 1974). This omission is surprising, given the potential for such a construct (Niranjan, Chattopadhyay & Hoyer, 1995).

This stream of research centers on the operating hypothesis that individuals

vary in the degree that emotion is sought, and furthermore, that this individuality is relevant to the buyer behavior context. The rationale for this stems from two points.

First, it has been established that individuals may differ in expressiveness, orientation, and intensity of experience of emotion (e.g. Allen and Hamsher 1974; Booth-Butterfield and Booth-Butterfield 1990). Based on these differences, researchers have speculated that individuals may also differ in their need to seek out emotional stimuli (Harris and Moore 1990). Second, many situations in buyer behavior such as information processing, decision-making, and impulse-buying, may be better understood by taking into account individual differences in dealing with emotions and emotional situations.

Given these assumptions, I predict that whenever there will be difficulties in imagine (e.g. low need for emotions levels, absence of imagery vividness stimuli, and obstacles to the imagery fluency) even a positive product experience would lower the likelihood of choosing the product.

28 Visual Imagery Disposition Invitation to Imagine Image Vividness Imagery Appeals

Need for Emotions Imagery Fluency

Attitudes and Behaviors

29

CHAPTER 2

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. The role of Imagination and Consumption Vision in Consumer Behavior

“Science doesn’t know its debt to imagination”

Ralph Waldo Emerson, Poetry and Imagination (1872) “Imagination is something different both from perception and from thoughts,

and is never found by itself apart from perception, any more than is belief apart from

imagination. Clearly thinking is not the same thing as believing. For the former it is in

our own power, whenever we please: for we can represent an object before our eyes,

as do those who range things under mnemonic headings and picture them to

themselves. But opining is not our power, for the opinion that we hold must be either

false or true. Moreover, when we are of opinion that something is terrible or alarming,

we at once feel the corresponding emotion, and so, too, with what is reassuring. But

when we are under the influence of imagination we are no more affected than if we

saw in a picture the objects which inspire terror or confidence” (Aristotle, On The Soul,

Book III, pg.84).

After centuries of researches and discovery on human psychology, anthropology,

and sociology, the modern definition of imagination is the “faculty or action of

producing ideas, mental images of what is not present or has not been experienced. It is

a mental creative activity that allows human beings to deal resourcefully with

unexpected or unusual problems, circumstances, experiences, etc.” (Collins English

Dictionary, 1991).

Imagination and fantasy are the most important qualities of what has been

30 in his conceptual paper, spectacle can be defined as a particular type of market

performance that involves consumer participation, exaggerating displays, social values

and emphasizing the knowledge of its mechanics of production as part of the

experience. In other words, spectacle is a rich, complex group of images and

environments, which conveyed cultural meanings that were integrated into consumers’

understanding of reality (Penaloza, 1998).

Indeed, when people imagine themselves playing the major role in a potential

future consumption situation, they are creating consumption visions. These visions

consist of series of vivid mental images of product/experience-related behaviors and

their consequences, which allow consumers to more accurately anticipate actual

consequences of imagined scenarios. The concept of consumption vision is derived

from that of mental imagery (Phillips, Olson, & Baumgartner, 1995) and entails sensory

representations of ideas, feelings, and objects or experiences with objects. From a

consumer behavior perspective, specifically in relation to intangible or experiential

purchases, a consumer’s mental image of a product is a primary source of information

available to help them in making decisions.

Constructing consumption visions may have thus certain decision-making and

behavioral implications. By envisioning oneself performing a particular behavior and

picturing the various steps involved in the consumption experience by “touching”,

“tasting”, “feeling” it, the consumer may better predict the consequences of actual

consumption of the experience and making the imagined scenario more “tangible” can

help him/her to make better and more formed decisions.

Consumption visions may even make easier for consumer who engages in

31 when people imagine a future scenario, they are more likely to predict that the scenario

will actually occur (Theory of Reasoned Action – TRA; Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975).

Strictly connected with visual consumption is the issue regarding what kind of

experience consumers imagine, or what kind of product they can imagine to buy or

consume in the future.

The consumption vision approach to mental images acknowledges the creative

sense-making process that consumers may use to anticipate the future by providing

clear, specific images of the self interacting with a product or experiencing the

consequences of its use (Pillips, Olson, & Baumgartner, 1995). From a narrative

perspective, consumption visions are stories derived from mental simulation that are

created by the decision maker and involve a character (the self), a plot (the series of

events the consumer imagines taking part in), and a setting (the environment or context

in which the event takes place). Other researchers, although the terminology of this

concept remains unique in its creation and application to consumer behavior, offer

different terminologies to define consumption visions.

Green and Brock (2000), for instance, refer to this form of mental imagery, as

“narrative transportation”, which involves the creation of stories via the mental

simulation of future events, focusing on goals, behaviors, and desired outcomes. Escalas

(2004) refers to this process as “mental simulation”, which entails the cognitive

construction of hypothetical scenarios, including rehearsals of likely desired future

events about less likely desired future events. Other authors, such as Jenkins (1999),

Lubbe (1998), and Gartner (1993) simply refer to the concept of “mental imagery”.

32 representations of the self-experiencing the future consumptive situations.

Thus, a question arises so far: is it better to verbally describe a situation in which

consumers can be involved during the imagined situation or is it better to associate verbal descriptions with visual representations of the experience, since not all of the individuals have previously experienced specific moments? Some experiences in fact, are so “unique” or “extreme” that most of the people probably have never faced them

before.

One method, via which a consumer may refer to his/her consumption vision as a

valued information source, is the so-called “narrative self-referencing”. This

phenomenon has been defined as a cognitive process that individuals use to

understand incoming information by comparing it to self-relevant information stored in

their memory (Debevec & Romeo, 1992). This method of imagery processing has been

shown to affect the persuasion power of the advertisement’s message and is often

accompanied by strong affective responses (Green & Brock, 2000). Escalas (2005)

suggests that the success of an advertisement in persuading the consumer is due to the

positive affect that occurs as a result of the mental simulation that distracts consumers

from weak arguments.

If, however, we are interested in knowing what a specific experience means for an

individual, we should ask to him/her to show some images that capture their thoughts

about our particular request. It means that, using the consumer’s point of view we are

able to catch inner feelings and meanings of some new situations not experienced yet.

A clarifying example could be the one mentioned by Zaltman in his book titled

“Marketing Metaphoria” (2008), in which he apply the Metaphor Elicitation Process in

33 In this example Zaltman explains that to prepare the young girl to the meeting,

she was required to collect eight images that represented how she felt about this phase

of her life. For about one hour and a half of this new mother’s visit, the interviewers

asked her to discuss each picture. The interviewers also asked her to imagine and

describe a one-act play or a short movie involving particular characters relevant to the

new motherhood. The interview captured verbalizations, sighs, pauses and other

indications of the emotions the new mother experienced as she described this recent,

life-changing event, all very important to the sponsor of the research, a global leader in

product designed for children. During the second part of the interview, was introduced

to the young mother, a graphic designer who scanned a participant’s images into a

computer just before the interview.

After the interview was ended, the designer asked her which of the chosen

images was the most important for her. He was in essence, serving as the girl’s hand

while implementing her thoughts. When they finished the collage of all the images the

interviewers asked the girl to explain the image created. The explanation that came

from her unconscious viewing lens revealed that many new mothers, as consumers,

experience the same feelings of transformation, connection, and container.

In other words, what is important to notice at this point, is that imagination as

far as being just an exterior reflections of our thoughts and past experience, is a very

powerful instrument to understand the innermost feelings, regardless some

situations we have never thought about, like for instance, becoming mother for the

first time (Zaltman, 2008).

Given the evidence for the effects of imagery on consumers’ judgments and

34 occur. In the next paragraphs I will present three aspects of the role played by

imagery on consumer behavior. Specifically, I will introduce the concepts of imagery

appeals, imagery fluency and imagery vividness and how consumer behavior

researchers have developed these concepts.

2.1.1. Imagery appeals

There are two different approaches on affect, experience recall, and

persuasion. Considering the first “traditional approach”, some studies suggest that

since imagery evokes affective responses, it can enhance product evaluation as well

(Bolls, 2002; Mani & MacInnis, 2001; Olliver, Thomas &Mitchell, 1993). Another

stream of research also reveals that information processed using imagery is stored in

two different codes: a sensory code and a semantic code, which means that imagery

has multiple linkages in memory (Childers & Houston, 1984; Kieras, 1978).

Information accessibility plays an important role in imagery appeals, indeed, has

been suggested that vivid information on invitations to imagine the product or

experience, are likely to influence preferences, by increasing the accessibility of favorable outcome-related information. This approach is called the “availability-valence hypothesis” and suggests that “because imagery can increase cognitive elaboration, it can increase or decrease product preferences according to the

valence of the product information made accessible” (Petrova & Cialdini, 2008, pp.

506). In other words, imagery can increase the accessibility of favorable, but also

unfavorable product information. In such cases, asking consumers to imagine the

product experience will increase their product preferences.

More recent research suggests that there are other additional processes that

35 Imagery appeals may engage processes that are different from those evoked

by simply presenting individuals with a pictorial product depiction. Petrova and

Cialdini (2005) found that, consistently with the availability-valence hypothesis,

increasing the vividness of the product (service) depiction results in a greater

number of product-relevant thoughts, and greater recall of the product information.

Recent investigations reveal new processes that may take place when

consumers engage in imaging the product experience. One of these “new

approaches” stems from the findings on narrative transportation studies. As

research on persuasiveness of narrative reveals, narratives have been found to be

effective in changing attitudes and beliefs, since they can easily transport consumers

into a different reality, reducing, at the same time, considerations of positive and

negative aspects of the message (Green & Brock, 2000). Transportation is a process

that implies the consumer to “get lost” in the story that has been told, and allows

him/her to access personal opinions, thoughts, previous experiences and knowledge.

Imagery likewise may influence product evaluations trough a similar process, by

transporting consumers into a distant reality and reducing their attention to the

favorability of the product information (Escalas, 2004; 2007).

When transported in imagined world, consumers may not be motivated to

change their initial assumptions and expectations at least for two orders of reason:

1) because they do not believe that the imagery had an effect on them, and 2)

because interrupting the imagery in order to elaborate the information, can make

the experience less enjoyable (Petrova & Cialdini, 2005). Recent research suggests

36 to evaluate the specific product attributes and counter-argue the message

arguments (Escalas, 2004; 2007).

When presented with the narrative description of the product, consumers

processed the information in a holistic manner, and were less likely to draw

inferences based on the specific attributes presented in the ad. These findings are

consistent with the research examining the effects of imagery on comparative

advertising: ads comparing the product with its competitors are effective under

analytical processing, but not under imagery processing (Thompson & Hamilton,

2006).

2.1.2. Imagery fluency

Another stream of research that introduced new investigations on the process

underlying the effects of imagery is the one that focuses on consumers’ experience

of fluency. Evidences demonstrate that when forming attitudes, opinion and

judgments, individuals are likely to take into account the content of the information

with which they are presented and with the ease with which these information come

to mind (Schwartz, 1998, 2004; Lee & Labroo, 2004). In other words, this approach

focuses on metacognitive experiences involved in processing product information

using imagery, rather than examining the impact of imagery on consumers’

elaboration of the message. For instance, when deciding on purchasing a house,

consumers might consider how easily they can picture themselves living there.

Typically consumers can easily image having products that are suitable for them,

that they intend to buy, or that they desire; therefore, the process of imaging a

product experience could be an efficient decision making strategy. On the other

37 their intentions or product appealing features. For example, deciding on a vacation

destination, an image of vacation in the Caribbean might come to mind easily if the

individual has previously been provided with imagery-evoking information in

magazines or advertisements.

Using commercial images to engage consumers in product imagery thoughts

of the consumption experience can create accessible mental representations of

having the product and can increase the ease with which such representations will

come to mind during the decision-making process.

Another research suggests that individuals tend to use the ease with which

they create a mental representation of an event to estimate the likelihood of an

event (Sherman et al., 1985), as well as the product evaluation (Dahl &Hoeffler,

2004) and purchase intentions (Petrova & Cialdini, 2005). Research on the effect of

hypothetical question on consumer behavior has demonstrated that simply asking

individuals about the likelihood that they will engage in a certain behavior, might

make them actually perform the behavior (Fitzsimons & Morowitz, 1996; Morowitz,

Johnson & Schmittlein, 1993). This effect however, has been found, can be moderate

by the ease with which consumers can generate a mental representation of the

behavior (Levav & Fitzsimons, 2006).

Following the model stated by the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Ajzen &

Fishbein, 1980), and its extension, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajezen,

1985) consumers’ intentions, which are the immediate antecedents to behavior, are

functions of a salient information or belief about the likelihood that performing a

38 Moreover, including beliefs regarding the possession of requisite resources

and opportunities for performing a given behavior consumers will perceive a

stronger behavioral control over the behavior they will perform (Madden et al.,

1992). In addition, according to the heuristic principle of the availability heuristic

(Tversky & Kahneman, 1973), one basis for the judgment of the likelihood of an

uncertain outcome is cognitive availability, that is, the ease with which this outcome

can be pictured or constructed.

The more available an outcome is, the more likely it is perceived to be. The

availability of any outcome should increase if one has recently predicted, imagined,

or explained it. Gregory et al. (1982) suggest two possible explanations by which

imagination procedures might lead to heightened availability of an event and thus to

an increase in its perceived likelihood. First, a subject who has imagined an event,

has constructed a mental image of the event. Because such image has been formed

already and is readily available in memory, any subsequent consideration will lead

this same image to be reconstructed more easily. Second, an initial construction or

representation of an event through an imagination or explanation procedure may

create a cognitive set that impairs the ability to picture the event in alternative ways.

Once a situation has been pictured in a certain way, it is more difficult to see

anything else as possible. Thus, imaging hypothetical future events may increase the

subjective likelihood of the events because of their increased availability.

A direct implication of this mechanism is the presumption that the

imagination of the event can be achieved easily and with little effort and, thus, that

the outcome of such imagination will be to render the event highly available

39 These findings then suggest that when considering buying a product,

individuals may spontaneously attempt to create a mental representation of the

product experience. By increasing the accessibility of such representations, thus,

imagery appeals can increase the likelihood of purchasing the product.

2.1.3. Imagery vividness

For this research, consumption vision is defined as the visual images that

consumers create in their minds when considering the purchase or use of a product

(Phillips, Olson, &

Baumgartner, 1995; Walker & Olson, 1994). Previous research in this specific area (see,

e.g., Bone & Ellen, 1992; Branthwaite, 2002; Keller & McGill, 1994) has confirmed a

positive relationship between ad-evoked consumption vision and the consumer’s

emotional response to various print advertising stimuli.

Three variables are expected to influence the construction of a consumption

vision (Lutz & Lutz 1978), specifically, an explicit invitation to construct the consumption

vision, the degree of verbal detail, and the degree of visual detail.

One way to get consumers to form consumption visions is to simply ask them to

do so. An invitation could be viewed as an explicit instruction to imagine the self-doing

something. One invitation could be, “imagine yourself behind the wheel of a Ferrari.”

Such an invitation to imagine the self-engaging in a specific consumption situation

should greatly facilitate consumption vision construction.

This is supported by one study which found a positive impact on product

judgments for only those subjects who were given instructions to use “the power of

your imagination to envision” the product (McGill and Anand, 1989). Indeed, compared

40 these instructions imagined more complex “consumption visions” and more detailed

product attributes (McGill and Anand, 1989). This suggests that when advertising copy

explicitly invites consumers to imagine themselves performing a variety of

product-related behaviors within a consumption vision, consumers may be more likely to

construct consumption visions.

Therefore, the direct approach to facilitating consumption vision construction

may be an invitation. Nonetheless, there may also be indirect ways to facilitate

consumption vision construction: verbal detail and visual detail in the advertisement

itself.

One indirect way to encourage consumers to form consumption visions would be

to include detailed verbal descriptions of what to expect during actual consumption of

the product. Indeed, detailed verbal descriptions facilitate the extent to which

individuals construct future scenarios (Carroll 1978).

In two past studies on consumption vision, two groups of individuals were

subjected to different treatments. One study had subjects to read a two-page,

single-spaced account of a future scenario (Gregory, et al. 1982) while another encouraged

subjects to close their eyes and imagine for 2-3 minutes the different steps involved in

successfully completing the imagined task within the scenario (Sherman and Anderson

1987).

One underlying mechanism by which concrete and detailed messages exert their

influence is to be the greater imagination of detailed messages. That is, descriptions

that use concrete language and specific details are easier to imagine and elaborate

(Taylor and Thompson, 1982; McGill and Anand, 1989). Another explanation is that